Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

The process of assessing the implications … of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programs, in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making women’s as well as men’s [and other vulnerable groups] concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programs in all political, economic and societal spheres so that [they] benefit equally and inequality is not perpetuated.

1.1. Literature Review

- How are gender policies related to the European Community, national, or regional regulations? Are these regulations included in the mission of the university itself and in its educational project?

- How does the institution ensure that the content of its GE plan is incorporated into its governing documents?

- Are the principles of GE and social justice included in degrees? How to ensure that the degree competencies are achieved and that the acquired skills are transferred to practice?

- Do teacher educators incorporate a gender perspective into teaching content and activities? Does this incorporation vary by discipline, area of knowledge or occupational field?

1.2. Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection and Procedure

2.3.1. Interviews

2.3.2. Document Analysis

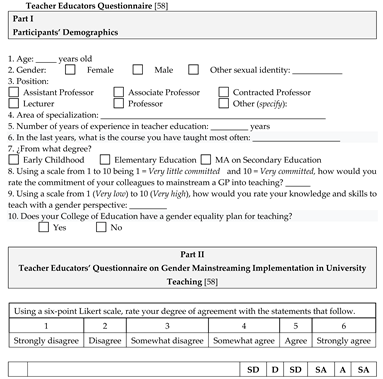

2.3.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Impact of the Gender Mainstreaming Policy on Education Degrees

Degrees in the College of Education do not include a specific commitment to developing gender equity competence, hence, study plans have not been designed with this purpose in mind. It can be said that they are gender blind. (SE1)

There is a specific regulation that makes explicit the incorporation of gender equality in the initial training of future teachers, but at the classroom level, very few changes have been made. (EL3)

I have not seen significant changes. The impact has been occasional and not systemic. (EC6)

There have been hardly any changes in study plans ... [Gender] has not been treated transversally in the different subjects. (SE8)

As far as I know, a course that addresses this issue has been incorporated in the curricula, but it is optional, when I understand that it should be mandatory. (SE9)

I think not. The UA Equality Plan does not offer specific guidelines nor require colleges to plan instruction incorporating a gender perspective in teaching, hence, with a few exceptions, courses do not include gender as a part of its contents. (SE1)

I believe that the College of Education has taken significant steps in this regard and it is observed, for example, in the number of Ph.D. candidates that are specializing in gender equity issues or in the number of master’s thesis that address the topic of gender. (EL2)

I think some efforts are being made, but isolated. There are groups of educators who work on these issues, but a unified, comprehensive teaching plan is needed for the entire College. (EC3)

3.2. Factors Influencing Educators’ Involvement in Mainstreaming Gender in Teaching

3.3. Self-Identified Challenges and Needs to Effectively Improve Teaching with a Gender Perspective

It is urgent to design an action plan in collaboration with the teaching staff that includes clear and concrete guidelines to: (1) put emphasis on the gender perspective in study plans and (2) commit that at least all core subjects include a gender component ... (EC3)

A board with representatives from different departments should be created for curriculum adaptation that should include competencies to be developed and block-contents clearly referring to gender and gender equity issues. (EL2)

In addition to transferring guidelines from the College, departments should sensitize and encourage their faculty to incorporate a GP in their classes. This can be done, for example, through the creation of a ‘GE commission’ that guides teaching staff, analyzes and evaluates the incorporation of the GP into the teaching guides and offers strategies to put them into practice. (EL4)

Teacher educators at the College must be aware that future teachers must be prepared to face situations of inequality in their classrooms, so having worked on these aspects in their initial training will help them in their professional practice. (SE7)

Increasing awareness on the issue of GE is necessary as well as having a good understanding of its importance and the need to carry out actions that promote gender equity. (SE9)

Preparing a dossier of examples by area of knowledge and model lessons in which various methods and strategies to mainstream a gender perspective into subjects could be helpful in a practical way. (EC6)

I believe that in the end, it is the teacher themselves who is responsible for including [a GP] in their assignments, so the most important thing is that there is an attitude of commitment to transformation and change. (SE9)

I spent my first year laying the groundwork, learning, and studying. In the second year, I began to apply a GE perspective in my classes, and in this third year, I feel more confident and with more capacity to teach wich a gender sensitive lens in my courses ... At a personal level, it has been a journey with challenges to overcome. Today the subject, the students, and myself have evolved. We have been transformed forever. (LE2)

Depending on the nature of the subjects I teach, I mainstream gender equality in a specific way, but it is a difficult task to carry out without the necessary training. (EC3)

I include dynamics to explore the social inequalities in power relations attached to gender but not in a regular basis. (EC6)

4. Discussion

- 1)

- Reflection processes of the meaning of the GM and its contextualization from a social justice framework. Without due reflection, contextualization, internalization and application of the principles and values of gender equity, educators/students will not be able to experience the necessary transformation [3,54-55].

- 2)

- Gender training. Teacher educators are not currently prepared to incorporate a GP into their teaching assignments. This preparation should be a prerequisite to become involved in GM implementation, as the follow-up of workshops and seminars on gender is not enough to transform the uncritical attitude to initiate a curricular transformation [56-58].

- 3)

- 4)

- Making equality plans more operational with regard to teaching. In guiding this process, the recommendations of the Swedish Secretariat for Gender Research [59] are essential.

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- 1)

- Do you consider that gender equity is an important issue in teacher training?

- 2)

- >2) What impact do you think gender equality policy has had on university teaching in the field of teacher preparation? Do you think that the design of study plans and the development of course syllabi have changed in any way since the publication of PL 3/2007? In which one/ones?

- 3)

- Do you think that the College of Education is doing what is necessary to make possible the inclusion of gender issues in university teaching?

- 4)

- What factors do you think affect the teaching staff's decision to incorporate a gender perspective in the courses they teach?

- 5)

- Considering that the inclusion of a gender perspective in university teaching is a legal requirement endorsed in international agreements and national/community regulations, how do you think its incorporation into teaching could be made effective?

- 6)

- If you are a teacher educator already initiated in mainstreaming a gender perspective in teaching, indicate how you do it? (e.g. What strategies do you use?

Appendix B

References

- United Nations. Beijing Platform for Action. 1995. http://www.5wwc.org/conference_background/Beijing_Platform.html.

- United Nations Economic and Social Council. (1997). United Nations Economic and Social Council Resolution 1997/2: Agreed conclusions, 18 July 1997. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/pdf/ECOSOCAC1997.2.pdf.

- Eveline, J.; Bacchi, C. What are we mainstreaming when we mainstream gender? International Feminist Journal of Politics 2005, 7, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzura, T. An overview of issues and concepts in gender mainstreaming. Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences 2017, 8, 1-21. http://dl.icdst.org/pdfs/files3/9162d2c0b71e1d60bb0bea620a26008f.pdf.

- Moser, A. (2007). Gender and indicators: Overview report. Sussex: Bridge Development-Gender, Institute of Development Studies.

- Walby, S. Gender mainstreaming: Productive tensions in theory and practice. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 2005, 12, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, Z. Decoding gender mainstreaming: Gender policy frameworks in an era of global governance. Yale Journal of International Affairs 2017, 12, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, B. (2022). Tackling gender inequality: Definitions, trends, and policy designs. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/12/02/Tackling-Gender-Inequality-Definitions-Trends-and-Policy-Designs-525751.

- UN General Assembly (2020). Quadrennial comprehensive policy review of operational activities for development of the United Nations system. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3896788?ln=en#record-files-collapse-header.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

- Bourn, D., Hunt, F., & Bamber, P. (2017). A review of education for sustainable development and global citizenship education in teacher education. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10030831/1/bournhuntbamber.pdf.

- UN Women. (2022). Handbook on gender mainstreaming for gender equality results. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2022/02/handbook-on-gender-mainstreaming-for-gender-equality-results.

- UNESCO. (2016). Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656.

- Cardona-Moltó, M. C., & Miralles-Cardona, C. (2022). Education for gender equality in teacher preparation: Gender mainstreaming policy and practice in Spanish higher education. In J. Bolvin and H. Pacheco-Guffrey (Eds.) Education as the Driving Force of Equality for the Marginalized (pp. 65-89). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Gough, A. (2016). Teacher education for sustainable development: Past, present, and future. In Leal Filho, W. & Pace, P. (Eds.), Teaching Education for Sustainable Development at University Level (pp. 109-122). Springer.

- Fischer, D.; King, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Barth, M.; Büssing, A.; Hemmer, I.; Lindau-Bank, D. Teacher education for sustainable development: A review of an emerging research field. Journal of Teacher Education 2022, 73, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ramos, F.J.; Zurian-Hernández, F.A.; Núñez-Gómez, P. Los estudios de género en los grados de comunicación. Comunicar: Revista Científica Iberoamericana de Comunicación y Educación 2020, 63, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrondo, A.; Rivero, D. A case study on the incorporation of gender-awareness into the university journalism curriculum in Spain. Gender & Education 2019, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merma-Molina, G.; Gavilán-Martín, D.; Hernández-Amorós, M.J. La integración del Objetivo de Desarrollo Sostenible 5 en la docencia de las universidades españolas: revisión sistemática. Santiago 2021, 154, 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Miralles-Cardona, C.; Cardona-Moltó, M.C.; Chiner, E. La perspectiva de género en la formación inicial docente: estudio descriptivo de las percepciones del alumnado. Educación XX1 2020, 23, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverter-Bañón, S. (Ed.). (2022). Experiencias docentes de la introducción de la perspectiva de género. Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I. https://repositori.uji.es/ xmlui/bitstream/handle/10234/197357/9788418951398.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Valdivieso, S. (Coord.), Ayuste, A., Rodríguez-Menéndez, M.C., & Vila-Merino, E. (2016). Educación y género en la formación docente en un enfoque de equidad y democracia. In I. Carrillo i Flores (Coord.), Democracia y educación en la formación docente (pp. 117-140). Universidad de Vic-Universidad Central de Cataluña.

- Rodríguez-Jaume, M.J., & Gil-González, D. (2021). La perspectiva de gènere en docència a les universitats de la Xarxa Vives: Situació actual i reptes futurs. Xarxa Vives d’Universitats. https://www.vives.org/book/la-perspectiva-de-genere-endocencia-a-les-universitats-de-la-xarxa-vives-situacio-actual-i-reptes-de-futur/.

- Atchison, A. The practical process of gender mainstreaming in the political science curriculum. Politics & Gender 2013, 9, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Sánchez, D.; Pagès-Blanch, J. Género y formación del profesorado: un análisis de las guías docentes del área de didácticas de las ciencias sociales. Contextos Educativos 2018, 21, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendes-Espinosa, M.P.; García-Tudela, P.A.; Solano-Fernández, I.M. Igualdad de género y TIC en contextos educativos formales: Una revisión sistemática. Comunicar 2020, 28, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollo-Catalán, A., & Buzón-García, O. (2021). La perspectiva de género en los planes de estudios universitarios en educación. In A. Rebollo-Catalán y A. Arias (Eds.), Hacia una docencia sensible al género en la educación superior (pp. 51-78). Dykinson.

- Serra, P.; Soler, S.; Prat, M.; Vizcarra, M.T.; Garay, B.; Flintoff, A. The (in)visibility of gender knowledge in the Physical Activity and Sport Science degree in Spain. Sport. Sport. Education and Society 2018, 23, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothwell, E. (2022). Gender equality: How global universities are performing. Part I. UNESCO & Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/digital-editions/gender-equality-how-global-universities-are-performingpart-1.

- Brunilla, K.; Kallioniemi, A. Equality work in teacher education in Finland. Policy Futures in Education, 2018; 16, 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Grünberg, L. (2011). From gender studies to gender in studies: Case studies on gender-inclusive curriculum in higher education. UNESCO-CEPES.

- Gudbjornsdottir, G.S., Thordardottir, T., & Larusdottir, S.H. (2017, October). Gender equality issues in teacher education and in schools: A plea for a change in practice. Paper presented at the conference on Gender Training in Education, Lisbon, Portugal.

- Kitta, I.; Cardona-Moltó, M.C. Students’ perceptions of gender mainstreaming implementation in university teaching in Greece. The Journal of Gender Studies 2022, 31, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitz-Sandberg, S.; Lahelma, E. Global demands-local practices: Working towards including gender equality in teacher education in Finland and Sweden. Nordic Journal of Comparative & International Education 2021, 5, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, G. A critical review of gender and teacher education in Europe. Pedagogy, Culture, and Society 2000, 8, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zippel, K.; Ferree, M.M.; Zimmermann, K. Gender equality in German universities: Vernacularising the battle for the best brains. Gender and Education 2016, 28, 867–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpazidou Schmidt, E.; Cacace, M. Setting up a dynamic framework to activate gender equality structural transformation in research organizations. Science and Public Policy 2019, 46, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, T. Políticas educativas igualitarias en España: la igualdad de género en los estudios de magisterio. Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas 2017, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcarra, M.T.; Nuño, T.; Lasarte, G.; Aristizabal, P.; Álvarez, A. La perspectiva de género en los títulos de grado en la Escuela Universitaria de Magisterio de Victoria-Gasteiz. Revista de Docencia Universitaria 2015, 13, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Alicante. (2022). IV Plan de Igualdad de Oportunidades entre Mujeres y Hombres de la UA (2022-2025). https://web.ua.es/es/unidad-igualdad/3-planes-de-igualdad/ivpiua-cas.pdf.

- University of Alicante. (2020). III Plan de Igualdad de Oportunidades entre Mujeres y Hombres de la UA (2018-2020). https://web.ua.es/es/unidad-igualdad/0-documentos/planes-de-igualdad/plan-igualdad-ua-3.pdf.

- Edwards, D.B., Jr.; Sustarsic, M.; Chiba, M.; McCormick, M.; Goo, M.; Perriton, S. Achieving and monitoring education for sustainable development and global citizenship: A systematic review of the literature. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, D.A., & Martin, M.D. (1984). Gender expectations and student achievement: A teacher training program addressing gender disparity in the classroom. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association: New Orleans, LA, USA.

- Acard-Erdol, T.; Gözütok, F.D. Development of gender equality curriculum and its reflective assessment. Turkish Journal of Education 2018, 7, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (2010). Model house to gender mainstreaming implementation. http://webbutik.skl.se/sv/artiklar/program-for-hallbar-jamstalldhet-resultatrapport-2008-2010.html.

- Sandler, J. (1997). UNIFEM’s experiences in mainstreaming for gender equality. United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM).

- World University Rankings. (2023). Impact rankings 2020: Gender equality. Elsevier-Vertigo Ventura. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/rankings/impact/2023/gender-equality#!/length/25/name/University%20of%20Alicante/sort_by/name/sort_order/desc.

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

- Cousin, G. Case study research. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 2005, 29, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S. Ten standard objections to qualitative research interviews. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 1994, 25, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Daly, M. Gender mainstreaming in theory and practice. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society 2005, 12, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. Mainstreaming gender perspectives into all policies and programs in the United Nations system. Spotlight 2004, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Ródenas, C. Género y formación crítica del profesorado: una tarea urgente y pendiente. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado.

- Brandt, J.; Bürgener, L.; Barth, M.; Redman, A. Becoming a competent teacher in education for sustainable development: Learning outcomes and processes in teacher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2019, 20, 630–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Cardona, C. (2020). Student teachers’ perceptions, competencies, and attitudes towards gender equality: An exploratory study. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain.

- Swedish Secretariat for Gender Research. (2016). Guidelines for gender mainstreaming academia. Author. https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/sscr_guidelines-for-gender-mainstreaming-academia.pdf.

- Cardona-Moltó, M.C.; Miralles-Cardona, C.; Chiner, E. Sustainable gender equality practice in education (Special issue). Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar]

| Participants | Age | Gender | Degree | Subject | Position | Prior GM experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | F | SE | RM | PR | No |

| 2 | 51 | M | EL | ET | AP | Yes |

| 3 | 48 | F | EC | ET | LE | Yes |

| 4 | 42 | M | EL | DI | LE | No |

| 5 | 36 | M | SE | DI | AP | No |

| 6 | 57 | M | EC | DI | AP | No |

| 7 | 42 | F | SE | RM | LE | No |

| 8 | 61 | F | SE | RM | AP | No |

| 9 | 34 | F | SE | DI | LE | Yes |

| Code | Degree | Competencies | Course descrip | Objetives |

Course content | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12192* | 3 |

O | O | O | O | O |

| 11998* |

3 | GC7: Design and develop learning spaces, with special attention to equity, equal rights and opportunities between men and women, civic education and respect for human rights that facilitate living in society, decision-making and building a sustainable future. | O | Recognize situations of inequality in relation to gender and promote educational actions that promote equality between men and women within the school organization. | Family changes and new gender roles. The democratization of family relationships. GE and coeducation. Prevention of gender-based violence. |

Gender and curriculum: contributions of gender to the study and practice of the currículum. |

| 17310* | 1 | GC1: Ethical commitment. Show attitudes consistent with ethical and deontological concepts, while respecting and promoting democratic values, gender equality, non-discrimination of people with disabilities, equity and respect for human rights. | O | O | O | O |

| 17313* |

1 |

GC1: Ethical commitment. Show attitudes consistent with ethical and deontological conceptions, while respecting and promoting democratic values, gender equality, non-discrimination, equity and respect human rights. EC3: Design and regulate learning environments that address GE, and respect for human rights. |

O | O | O | O |

| 12023* | 3 | GC7: Design and develop learning spaces, with special attention to equity, equal rights and opportunities between men and women, civic education and respect for human rights that facilitate living in society, decision-making and building a sustainable future. | O | O | O | O |

| 17511** |

2 |

Promote actions to develop equal opportunities and compensate for inequalities of origin that affect students when entering the center. | O | O | O | O |

| Code | Degree | Competencies | Course descrip | Objetives | Course content | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17516** | 2 |

O | O | O | O | O |

| 12031* | 3 |

O | O | O | O | O |

| 12078* | 3 |

O | O | O | O | O |

| Factors | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Institutional | I believe that the College does not have a plan that includes specific guidelines and requirements to help design gender-sensitive teaching guides. If there was, educators will follow it and implement it. (SE1) Faculty must lead this project in order to create a climate conducive to GM implementation. (EC6) There should be be a greater commitment from the teaching staff. There is a lack of general guidelines that allow educators to incorporate the gender perspective in their classes. (EC3) For me, it’s necessary to design lesson plans and proposals that support teacher educators in the task of incorporating a GP into their daily practice. Having a person who is in charge of coordinating all actions is essential. (SE7) Providing specific resources ... and disseminating successful initiatives would help getting educators involved. (SE9) |

| Departmental | My department is even less sensitized than the College. Gender and gender equity issues are not given the importance they really have. The neutrality to the subject is evident. (SE1) There should be a gender equality specialist in each department. (EL2) Departments should control educators’ involvement in teaching with a gender perspective. (EC3) In most cases, departments do not do what is necessary. They limit themselves to transferring information they receive from the university or the College. They do not provide indications on how gender issues should be mainstreamed. Clearly, there is a lack of involvement. (SE7) Recognition of faculty work on this issue is necessary. (SE5) |

| Professional | Faculty are not sufficiently incentivized. (SE1) Professional motivation is always a key element. There is a lack of motivation on this topic. (EL2) Inadequate preparation for the topic is a real barrier to developing the project at university level. (EC6) Lack of awareness ... Studies at the College are highly feminized, which can lead educators to think that a gender perspective is not necessary. The low presence of men in classes makes the debate difficult. (SE7) In my case, working with other colleagues in this field (educator circles) has made me notice aspects that I did not notice before, which has increased my commitment to working on this topic. (SE9) |

| Personal | Gender is not perceived as an important issue in teacher preparation. (SE1) From my view, there is a positive will to implement GM, but it would need clear guidelines, support and collaborative work to implement the plan. (SE8) The belief that a gender perspective can be incorporated into any subject should be enforced. It is necessary to develop gender competence to carry out this commitment. (SE7) I believe that everyone’s personal experience is key to change their attitude and disposition towards this topic. (SE9) |

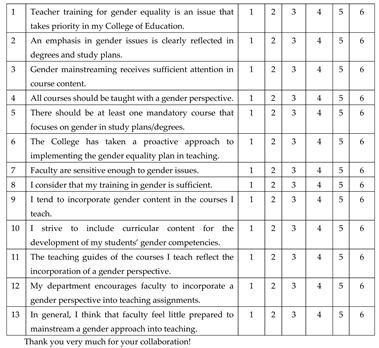

| Agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min-Max | M | SD |

f |

% | |

| Perceptions about Personal Commitment | |||||

| 1. Training for gender equality is a priority issue in my College. | 2-6 | 4.67 | 1.41 | 4 | 44 |

| 4. All courses should be taught with a gender perspective. | 4-6 | 5.44 | 0.88 | 7 | 78 |

| 5. There should be at least one required course on gender issues in the curricula. | 3-6 | 5.00 | 1.50 | 6 | 67 |

| 8. I consider that my training in gender is sufficient. | 1-5 | 3.22 | 1.56 | 3 | 33 |

| 9. I tend to incorporate gender content in the courses I teach. | 1-6 | 3.89 | 1.69 | 3 | 33 |

| 10. I strive to include curricular objectives and content for the development of my students’ gender competencies. | 1-6 | 4.22 | 1.56 | 4 | 44 |

| 11. The teaching guides of the courses I teach reflect the incorporation of a gender perspective. | 1-6 | 3.67 | 1.58 | 3 | 33 |

| Total factor | 2.86-5.86 | 4.30 | 1.15 | ||

| Perceptions about Institutional Commitment | |||||

| 2. An emphasis on gender issues is clearly reflected in degrees/study plans. | 2-6 | 3.22 | 0.97 | 0 | 0 |

| 3. GM receives sufficient attention in the subjects that make up the study plans. | 2-6 | 2.89 | 1.05 | 1 | 11 |

| 6. The College has taken a proactive approach to incorporating the GE plan in teaching. | 2-6 | 4.00 | 1.22 | 3 | 33 |

| 7. Faculty are sensitive enough to gender issues. | 2-6 | 3.33 | 1.22 | 2 | 22 |

| 12. My department encourages faculty to incorporate a GP into teaching assignments. | 2-6 | 3.67 | 1.32 | 2 | 22 |

| 13. In general, faculty feel little prepared to mainstream a gender approach into teaching. | 2-6 | 5.11 | 1.05 | 7 | 78 |

| Total factor | 2.67-4.50 | 3.70 | 0.65 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).