Preprint

Article

The nonspecific effects of COVID-19 vaccination upon non-COVID-19 all-cause mortality (NCACM) in the population of England: Effects of age, sex, COVID-19 variant, vaccination history, and time in a real-world study from Jan-21 to May-23

This version is not peer-reviewed.

Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

All vaccines exhibit specific and nonspecific effects. Specific effects are shown by the efficacy against the target pathogen, while nonspecific effects can be detected by the change in all-cause mortality. The real-world non-COVID-19 all-cause mortality (NCACM) data for the population of England between January 2021 and May 2023 was assessed. All vaccines administered were based on the original Wuhan antigen. Each gender and age group, along with COVID-19 variant shows its own unique NCACM vaccination benefit/disbenefit time profile. The efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination against COVID-19 disease/death per se is undisputed, however, the nonspecific outcomes of COVID–19 vaccination is far more nuanced than have been widely appreciated. This confirms an earlier study on the unanticipated nonspecific effects of influenza vaccination against all-cause winter mortality. Interestingly, a high proportion of NCACM beneficial effects occurred during the first 21 days following COVID-19 vaccination, while the worst example of increased NCACM occurred during the fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccination in 19–40-year-olds for the interval >21 days post vaccination which led to NCACM 3- to 10-times higher than in the unvaccinated. By the time of the Omicron variant, NCACM outcomes in those aged 90+ are mostly adverse. The beneficial nonspecific effects of COVID-19 vaccination increase with age and reach their maximum effect during the second week post vaccination for age groups below 50 years, rising to during the third week for those aged 70+. Finally, we discuss the mechanisms by which COVID-19 vaccination could induce wider nonspecific effects. Most of these mechanisms seem to depend on gene regulation by noncoding RNAs which also interact with mRNAs. We suggest that further international studies are required to discern the nonspecific NCACM effects of the different COVID-19 variants other than the three variants prevalent in the UK, and different types/manufacturer of COVID-19 vaccines which have been employed around the world. We can only speculate regarding the nonspecific effects of the COVID-19 vaccines administered to persons with an asymptomatic infection, and during vaccine waning. Vaccines not only need to be effective against the target pathogen, as primarily determined by antibody production, but need to minimize any unanticipated adverse nonspecific effects against all-cause mortality.

Keywords:

COVID–19

; vaccination

; all-cause mortality

; age

; gender

; complex system

; pathogen interference

; seasonality

; miRNAs

; negative vaccine effectiveness

; nonspecific vaccine effects

supplementary.docx (43.17KB )

Preprints on COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2

1. Introduction

The high mortality from the COVID-19 pandemic led to a desperate search for effective vaccines and of necessity several were given temporary or emergency authorization. However, there is increasing awareness that vaccines exhibit specific and nonspecific effects in both humans and animals [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Thankfully most (but not all) of the nonspecific effects detected in humans and animals have led to wider beneficial effects against all-cause mortality [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Benn et al [6] have argued that the existence of nonspecific effects has profound implications for the testing, approving, and regulation of vaccines. The specific effects are measured by the efficacy of the vaccine against the targeted pathogen, while the nonspecific effects can be discerned by evaluating the change in all-cause mortality. A fully efficacious vaccine will reduce deaths arising from the targeted pathogen but should have minimal adverse nonspecific effects.

There are two examples of the nonspecific effects of vaccines during COVID-19. During the early stages of the pandemic both influenza and BCG vaccination gave nonspecific protective effects against COVID-19 morbidity and mortality [7,8,9,10].

The nonspecific effects arise from the ability of pathogen antigens to cause polyclonal immune activation [11,12], immunostimulation [13], antitumor effects [14], and the ability of pathogen antigens to initiate the mechanisms of pathogen interference, which are mediated by the production of small noncoding RNAs (miRNAs) which comprise the small non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs): miRNA, siRNA, etc. [4]. The small ncRNAs then regulate gene expression which either enhances or diminishes infection by other pathogens. Vaccines (as a class of antigens) also stimulate the production of miRNAs [4], and hence create sometimes unexpected, nonspecific outcomes like pathogen interference. Vaccination may also induce antibody-dependent enhancement with negative health consequences [15,16,17,18].

While it is true that all vaccines in commercial use are effective against the target pathogen, we have recently demonstrated that influenza vaccination has powerful nonspecific effects against all-cause winter mortality [19]. Indeed, using a data set of nearly 100 countries over a 40-year period no long-term net effect against all-cause winter mortality could be demonstrated [19,20]. This was because in some years influenza vaccination was associated with benefit against all-cause mortality, while in others with net disbenefit [19,20]. The degree of benefit/disbenefit varied each winter (as does the composition of the vaccine) and between countries. Increasing obesity may be associated with net disbenefit [20]. Climatic and other variables appear to explain the different levels of international pathogen circulation and diversity over the winter or rainy season near to the equator [19,20].

Influenza and SARS-CoV-2 are among the class of RNA pathogens showing high mutation rates [21,22,23,24]. Each new clade of antigen mutations leads to a unique age profile for each variant which is also associated with the generation of specific miRNAs, further nuances of pathogen interference and epigenetic modifications [25]. In the UK, the COVID–19 pandemic commenced somewhere in early 2020 with the first laboratory-confirmed death occurring on 2 March 2020 [26]. However, COVID–19 testing capacity was very low at that time and earlier deaths are possible. Research in the USA suggests that COVID–19 deaths may have started in early January 2020 [27]. Hence, we have the pre-COVID era which ends in December 2019 through to the ongoing surges as new variants come to the fore [24,28,29,30].

As for the strains of COVID–19 the original Wuhan strain is predominant during 2020. The Alpha strain (formerly the Kent variant) appears around December 2020 and predominates from January to June 2021, the Delta strain (formerly the Indian variant) commences around May 2021 and predominates from July to December 2021. While Omicron (BA.1) first emerges in November 2021 but begins to spread in December 2021 and dominates from 2022 onward (BA.2 followed by BA.4/5, etc.) [24,28,29,30]. The Alpha variant caused slightly higher mortality than the original strain and will therefore affect mortality in the winter of 2020/21 [24,28,29,30]. The Delta variant which mainly affected the winter of 2021/22 had higher transmission and a slightly lower or equal mortality risk [24,28,29,30].

Under the normal course of events vaccination against something like influenza commences before the influenza season. However, the vaccination schedule for COVID-19 vaccines depended on the dates for approval and the need for widespread vaccination among adults. As a result, individuals were being vaccinated at different times of the year, at points associated with the arrival of new variants, and at occasions of high through to low incidence of COVID-19 infections. If nonspecific effects were to exist, then the unusual circumstances associated with the COVID-19 vaccination campaign offer the greatest opportunity for such effects to be identified and quantified.

In the UK, COVID-19 vaccines were approved in the following order: Pfizer/BioNTech (2 December 2020 - deployed 8 December 2020), AstraZeneca (30 December 2020 - deployed 4 January 2021), Moderna (8 January 2021 - deployed 7 April 2021) [31,32,33]. The proportions of persons vaccinated by age and time from different manufacturers (Pfizer/AstraZeneca/Moderna) does not appear to be publicly available. Table 1 provides a summary of the timeline for vaccination in England.

COVID–19 vaccination began on 8 Dec 2020 for care home residents, persons aged 80+, and some health care workers, by 18 January 2021 this included age 70+ and persons with very high clinical risk, by 15 February age 65+ and persons with high risk, and by 22 May age 32+ and age 18+ by 18 June 2021 [31,32,33]. Following reports of a rare type of blood clot in late March 2021 for the AstraZeneca vaccine, persons under 30 years were all given the mRNA vaccine from 7 April 2021 onward, and those aged under 40 from 7 May 2021 onward [34].

Astra Zeneca was phased out from September 2021. An alternative non-mRNA vaccine Novavax (recombinant protein) was made available from spring 2022 onwards. Some younger children with high clinical risk were vaccinated from January 2021 onward [33,34,35,36]. Vaccination of persons aged 16 ̶ 17 years was from July 2021 onward, 12 ̶ 15 years from September 2021 onward and 5 ̶ 11 years from February 2022 onwards for those with high risk and for any child aged 5 ̶ 11 from April 2022 onward. The majority aged 12+ were vaccinated during late 2021. All with mRNA as per the age under-40 rule as above. Booster doses began to be delivered from 16 September 2021 and these were all mRNA. Further booster doses were given in February/March 2022, and September 2022 for the winter of 2022/23 respectively. From around spring 2022 onward persons were vaccinated (including booster) with a mix of the mRNA vaccine and the Novavax (a non-MRNA recombinant protein) vaccine.

Healthcare workers in the NHS (who will mostly be under the age of 65) began to be vaccinated from 8 December 2020 (initially with Pfizer/BioNTech) and by March 2021 over 80% of clinical staff had received their first dose and over 39% had received their second dose [35]. To vaccinate the most people, the timing of the second dose was delayed to approximately 12 weeks [33]. In practice, vaccination schedules showed local and regional variation. In order not to waste vaccines, toward the end of the day many centers would send social media messages for adults of any age to be vaccinated.

A somewhat neglected 2010 study suggested that optimum vaccination outcomes can only be achieved when the timing of vaccination is adjusted relative to the target and competing pathogens [36]. The implication is that sub-optimum outcomes are possible. Table 1 summarizes which vaccines were prevalent in each age band for vaccination during the three variants.

The timing for the approval of COVID-19 vaccines (listed above) meant that the English population (mainly oldest first) only began to be vaccinated during an outbreak of the Alpha variant [25], and with first dose still being delivered to some people into 2022 and 2023 during the outbreak of the Omicron variant [37]. Ample opportunities for suboptimum time-based outcomes are therefore present.

While COVID–19 vaccination is clearly effective against COVID–19 mortality per se [37,38,39] there is a paucity of studies using the ‘gold standard’ of a reduction in NCACM. This was achieved using a record-linked whole population study of COVID–19 vaccination in England by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in 2021 through to May 2023. This study uses age bands, month of death, and vaccination status (first, second, third dose at both up to 12 weeks and greater than 12 weeks post vaccination) [40].

The all-cause mortality data set used in this study is very large and covers all residents of England who are registered with a GP and were residents in England at the 2011 census [40]. This allows detailed analysis of 944 000 deaths over a 29-month period by gender, over 7 age bands, and by various stages of vaccination split by less than 21 days, and greater than 21 days post vaccination, and at monthly intervals – which can be grouped by SARS-CoV-2 variant [25].

The unique feature of the ONS data is that mortality is available at monthly intervals – a feature which is very rare in vaccine studies. Such profiles compare the mortality rates by age and gender within a vaccination stage or over time. The shape of the time profile gives an internal consistency check. We thereby avoid arguments regarding the exact value of each data point, since the principal aim of the study is to demonstrate that nonspecific effects do exist and have important consequences.

Our results are illustrative rather than prescriptive for three reasons.

- The study uses only seven broad age bands. We have demonstrated that each COVID-19 variant has a unique single-year-of-age profile for mortality [25] and would argue that age should be a continuous variable. The use of age bands is probably concealing more nuanced behavior.

- The study was conducted at a time when vaccines in the UK were based on the original Wuhan stalk antigen. In addition, by early 2023 the Alpha and Delta variants are no longer present, and by the end of the study only Omicron sub-variants were circulating. The results cannot therefore be directly extrapolated into the future should variants other than Omicron arise.

- Time since vaccination is split into two groups, namely, up to 21 days and greater than 21 days. The up to 21-day group encompasses the time when immunity is being optimized, however, the greater than 21-day group contains a mix of individuals with differing degrees of vaccine waning.

Hence, we seek to establish the basic principles rather than argue if a certain set of conditions caused a large or very large increase in non-COVID-19 mortality in the vaccinated. Confidence intervals are not shown simply because they only add unnecessary complexity to an already data rich study. They are however available in the ONS data [40].

The above needs to be understood in terms of system complexity which leads to unexpected outcomes. We have recently proposed that influenza pandemics and epidemics show very high system complexity leading to unexpected all-cause mortality outcomes associated with influenza vaccination in approximately 50% of years [4,19,25]. Such system complexity may well lie behind the reported nonspecific effects of vaccines [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Indeed, it is possible that the age-based schedule of COVID-19 vaccination (as above), along with the specific (and unexplained) single-year-of-age profiles for mortality associated with COVID-19 variants [25], has inadvertently increased system complexity in unexpected ways. It is hoped that this study will shed light on such issues.

Finally, we will provide an extended discussion of the mechanisms by which such nonspecific effects can occur focusing on the somewhat neglected effects of both the environment, drugs, and vaccines upon the expression of noncoding RNAs which are profoundly powerful regulators of gene expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. All-cause mortality by vaccination status in England

Month of death, vaccination status and age band come from a whole population record-linked study by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) [40]. Vaccinations are not recorded on the death certificate when the death is registered, therefore the ONS publication ‘Deaths involving COVID-19 by vaccination status’ [40] uses mortality data with data linkage to the National Immunization Management System.

The data for the age-standardized mortality rates (ASMRs) are created using the Public Health Data Asset (PHDA), a linked dataset combining the 2011 Census, the General Practice Extraction Service (GPES) data for coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic planning and research, and the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES). The ONS then linked vaccination data from the National Immunization Management Service (NIMS) to the PHDA based on the individuals NHS number.

This data source has two files. The first file contains data for the period January 2021 to May 2022. The second file contains updated data for the period April 2021 to May 2023. The data is continuously updated implying that the file to May 2023 has more deaths than the file to May 2022. Numerical data in both files is stored as text which was converted back to numbers using the Microsoft Excel Data tool, ‘Text to Columns’. In this study data for the months January to March 2021 was taken from the first file while that from April 2021 to May 2023 was from the second file.

Both files give the age standardized mortality rate (deaths per 100 000 person years) for several age bands. Confidence intervals are given in the ONS data file [40] and show the expected variation with number of deaths, hence, ± 20% of the mortality rate value based on 100 deaths (for example females aged 18-39, first dose > 21 days ago, for death in April 2021), and ± 3.9% at 2500 deaths, etc. Age standardized mortality is not given for instances where there are less than 3 deaths within the age band - zero deaths are reported as zero.

values ‘less than 3’ was substituted by 1 death and the resulting unadjusted mortality rate was calculated. The mortality rate is standardized within each age band. The raw versus standardized mortality rates by age band were compared and showed high correlation (R-squared = 0.998). The raw mortality rate tended to be lower than the standardized rate and the interquartile range for the difference was -3.6% to +1.1%. The high correlation between the two arises from the fact that the age bands are mostly only 10-years wide, except for ages 18 ̶ 39 and 90+. Age standardization within such relatively narrow age bands is unable to have a large impact on the difference between raw and age standardized mortality rates. The raw mortality rate is only used when an age standardized value is not available on 29% of occasions.

The ONS only provides data for all-cause mortality and COVID-19 mortality [40], and hence non-COVID-19 mortality (NCACM) is via subtraction of the latter from the former. In the case of <3 deaths, this creates gaps in the non-COVID-19 mortality after subtraction.

2.2. Effect of time of vaccination, vaccine history, gender and age upon all-cause mortality

To maintain simplicity, the data is presented as the mortality rate for both the vaccinated and the unvaccinated. This is given monthly or over the duration of the various COVID-19 variants, and vaccine doses.

Given that the study uses the population of England, the unvaccinated groups are generally large and provide a reliable time profile against which to compare the outcomes in the vaccinated.

At small numbers a Poisson distribution becomes highly skewed. In a Poisson distribution the two equally most common values are the average, and the average minus one. Hence, for 3 expected deaths, 2 and 3 should appear equally, etc. The outcome is that at small numbers a Poisson distribution tends to underestimate, hence, very high values of disbenefit are most likely underestimates rather than statistical overestimates. We note that the data contains far fewer examples of 0 deaths than would be expected.

3. Results

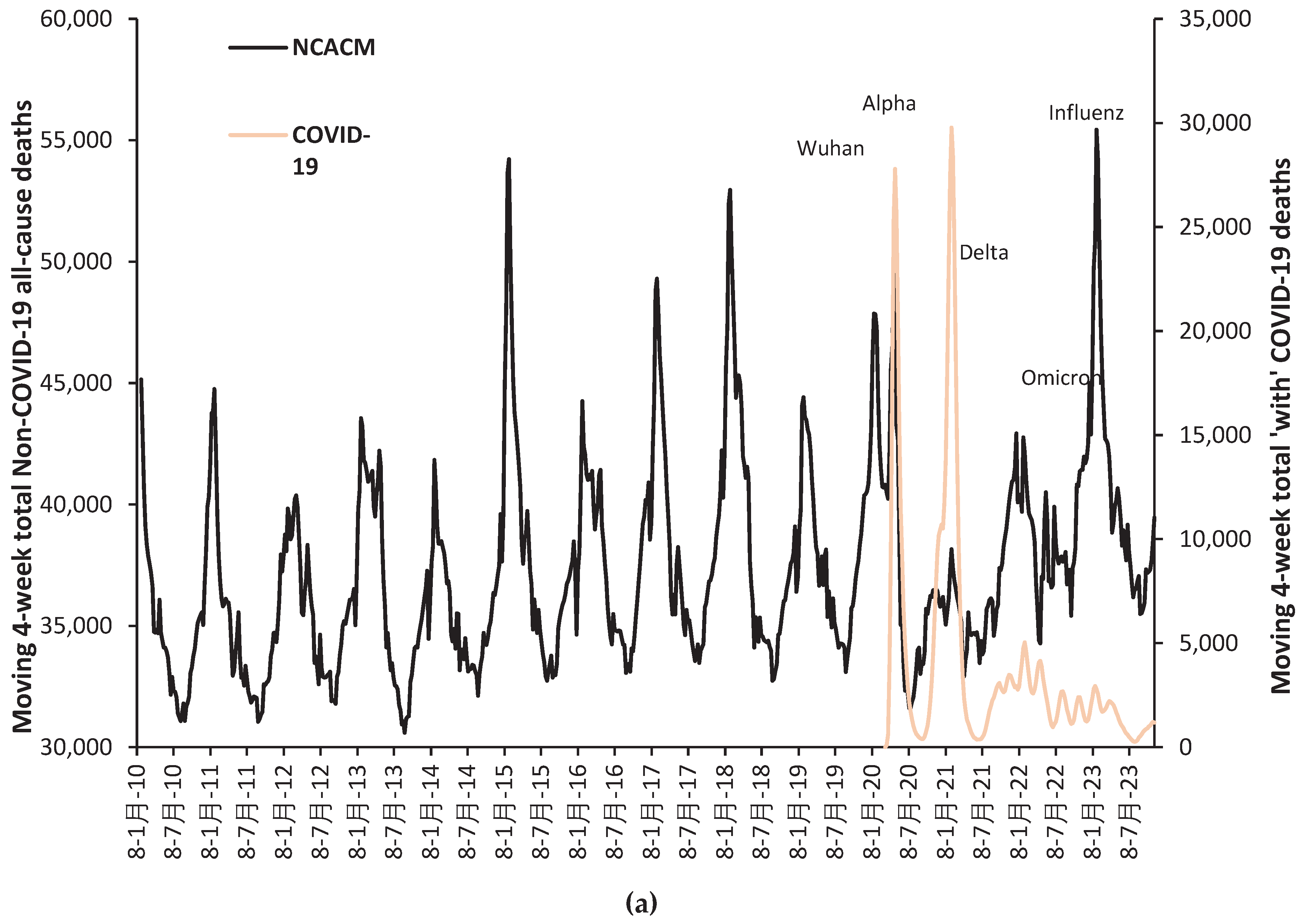

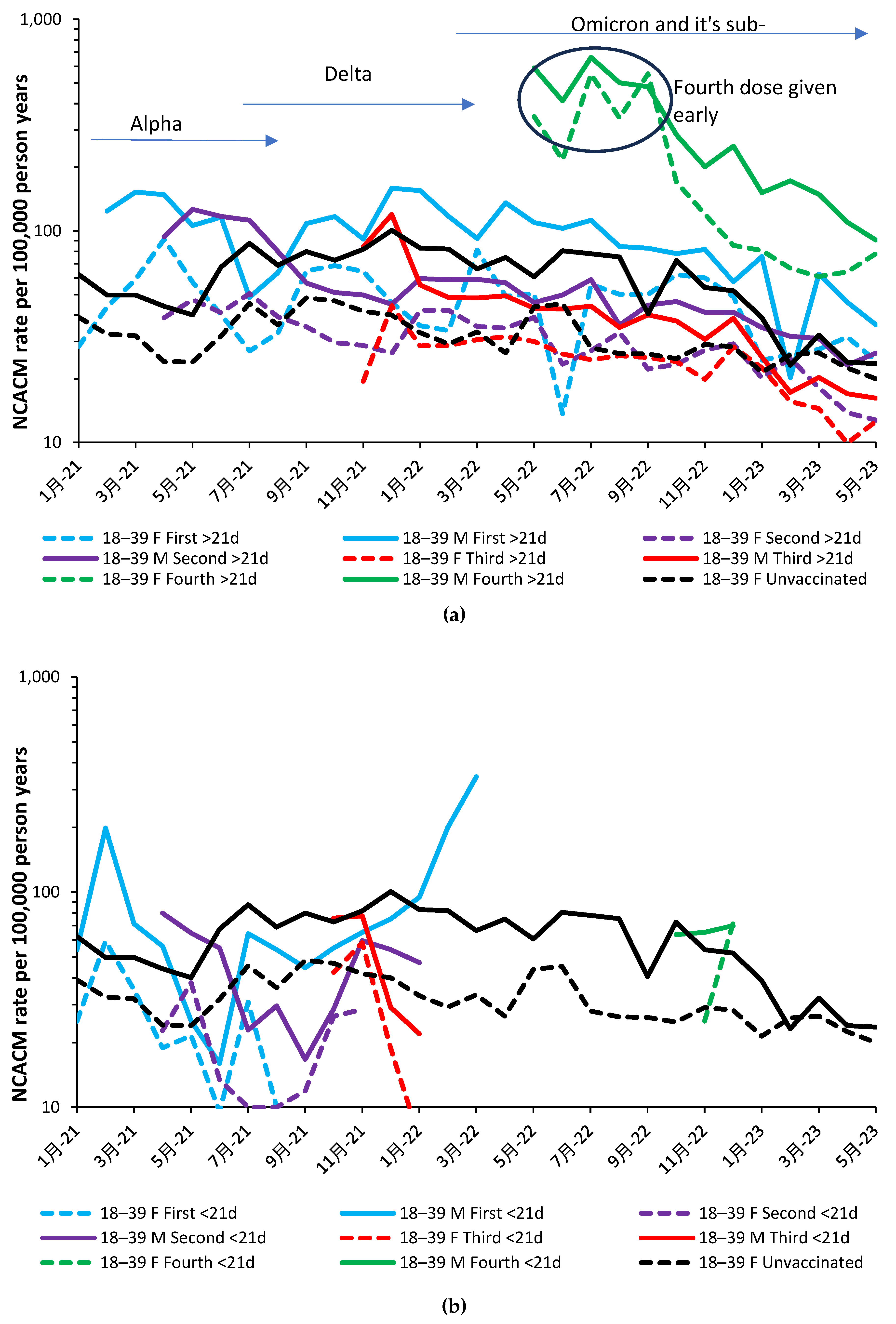

3.1. Overview of the net effect of vaccination with time

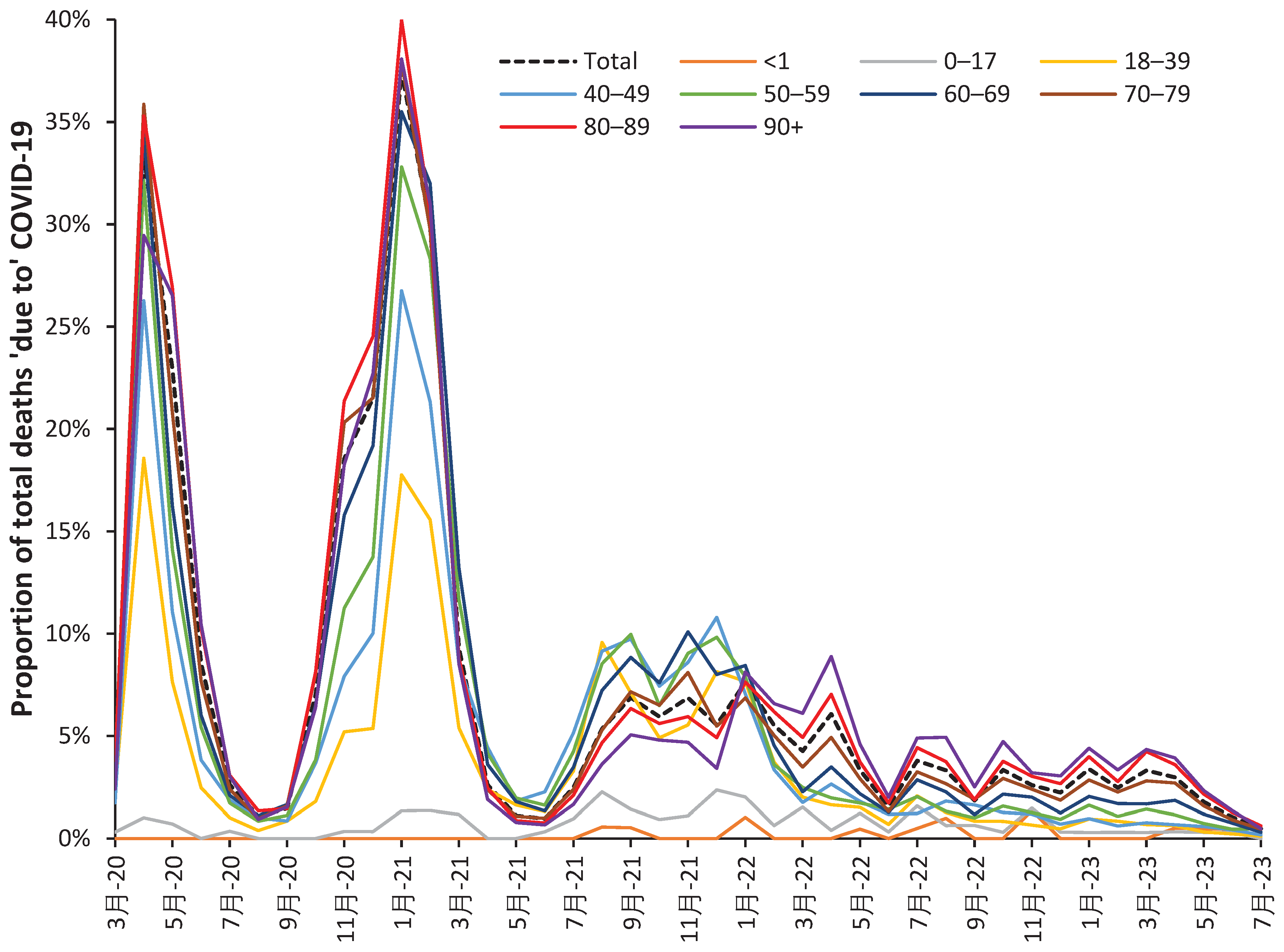

As a reference point Figure A1.1 and Figure A1.2 in the Appendix shows the trend in proportion of total deaths ‘with’ COVID-19. The two major outbreaks peaking at weeks ending 17-Apr (Wuhan) and 8-Jan (Alpha) are evident. Figure A1 is for all ages but clearly shows the peaks and troughs in COVID-19 deaths. Weekly data has been used for greater definition [42]. From Figure A1.2 note three ‘summer’ minima in the proportion of total deaths with COVID-19 in June to Aug-21, Jun-22, and Jul-23. Also note peaks in January 2021, and a series of undulating maxima in Sep-21, Nov-21, Jan-22, Apr-22, Jul-22, Oct-22, Jan-23, and Mar-23. These most likely outbreaks of the various COVID-19 variants and sub-variants. At the other extreme is a trough occurring in April/May of 2021 for age bands below 50 years. The trough represents the non-outbreak tail end of the Alpha variant [25], followed by the arrival of Delta which specifically targets the younger ages [25].

Further undulations reflect the relative impact of outbreaks of the three different SARS-CoV-2 variants upon different age groups [25]. Likewise, Omicron had a disproportionate effect on the groups aged over 80 years [25]. Hence the overall shapes of the trends are consistent with the independently characterized effects of the variants upon the year-of-age age profiles for mortality [25].

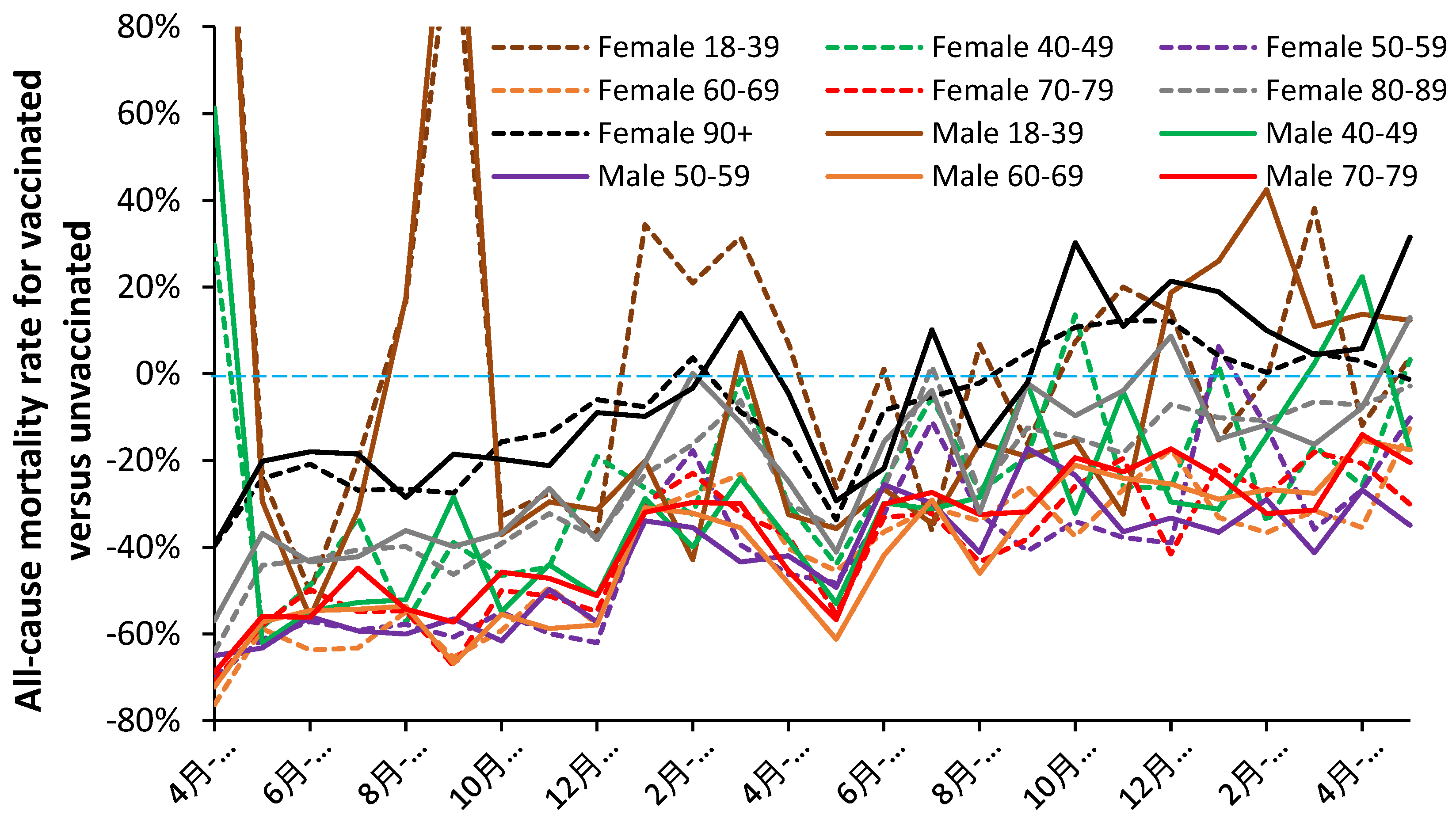

Figure 1 shows the net effect of COVID-19 vaccination against all-cause mortality (including COVID-19 deaths) for persons aged 18+ receiving one or more doses of the vaccine. Below the blue dashed line is increasing protection, i.e., all-cause mortality is reduced relative to the unvaccinated, while above lies increasing all-cause disbenefit.

As can be seen the COVID-19 vaccines employed in England generally had a net beneficial effect against all-cause mortality (except perhaps in the two youngest age bands, under specific conditions) which diminished with time, seemingly, due to the transition between SARS-CoV-2 variants and sub-variants. This decline in performance reflects the known specific effect of antigenic distance between a vaccine and the prevailing variants and sub-variants [4]. It will also include any unanticipated nonspecific beneficial/disbenefit effects from vaccination, which are expected to exist [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Differences between males and females are evident with males seemingly benefiting more from vaccination than females. June and July of 2021 represent a point of minimum COVID-19 mortality as a proportion of all-cause mortality [42]. COVID-19 mortality does not drop to this low level again until June of 2022 just after the peak of infections due to the arrival of the first Omicron variant, and then again in July 2023 [25].

Based on the mean/median values for the last six months (Dec-22 to May-23) the best vaccine protection occurs in the interval 50–79 years and deteriorates either side. Disbenefit against all-cause mortality occurs in the youngest and oldest age groups.

Hence, the overall conclusion is that COVID-19 vaccination was generally but not specifically successful at reducing population-wide all-cause mortality (including COVID-19 mortality) but that the effectiveness of the vaccine reduced as new SARAS-CoV-2 variants and sub-variants showed increasing antigenic distance from the vaccines based on the original Wuhan strain. However, age appears to be a key factor as has been previously demonstrated for COVID-19 variants [25].

Within the above context of general vaccination success (with curious exceptions), the aim of this paper is to avoid investigating the specific effects of vaccination which may include antigenic distance and other factors, hence, to focus primarily on all-cause mortality which excluded COVID-19 deaths (NCACM), to investigate some of the more curious outcomes seen in Figure 1.

3.2. Unexpected complexity

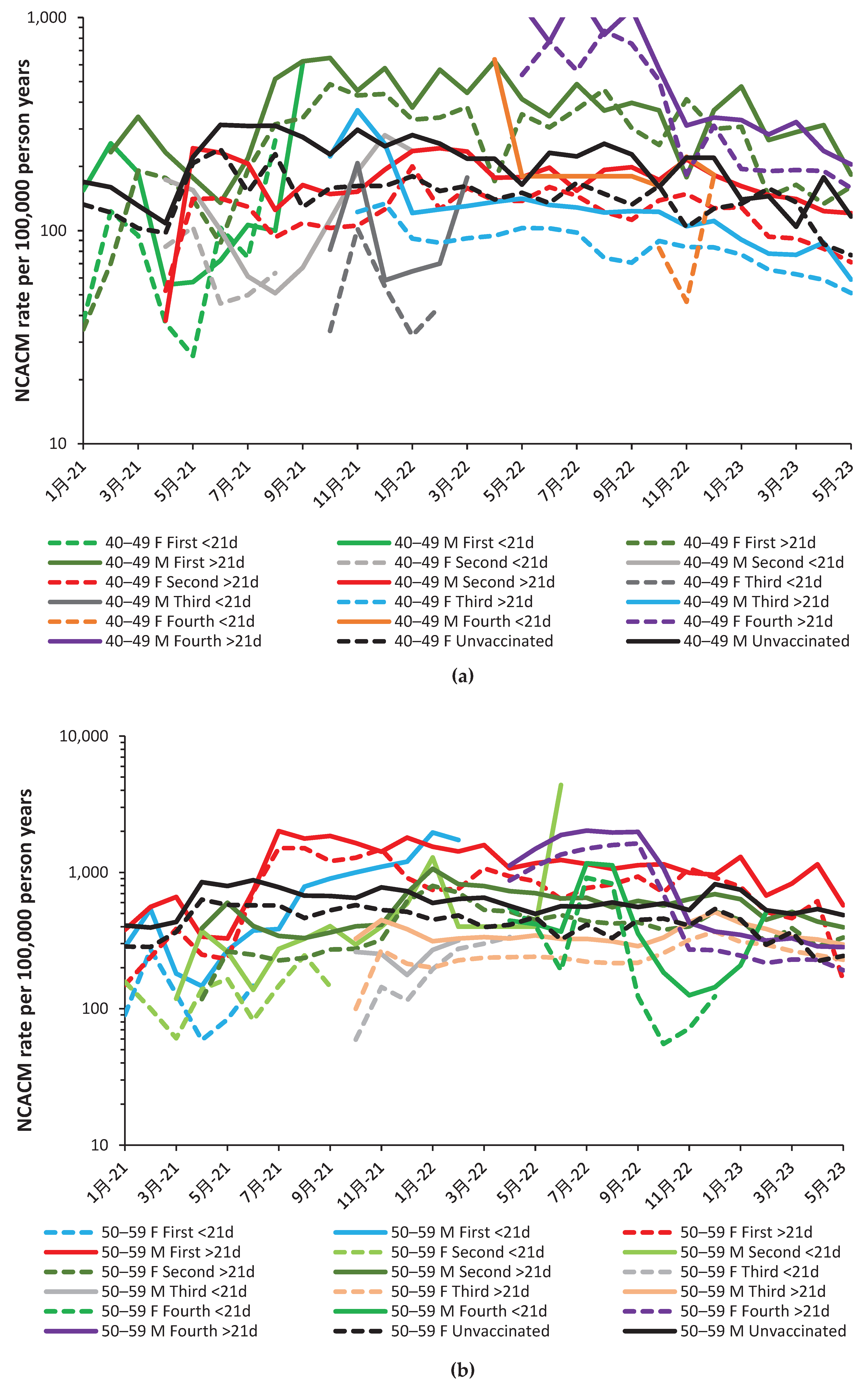

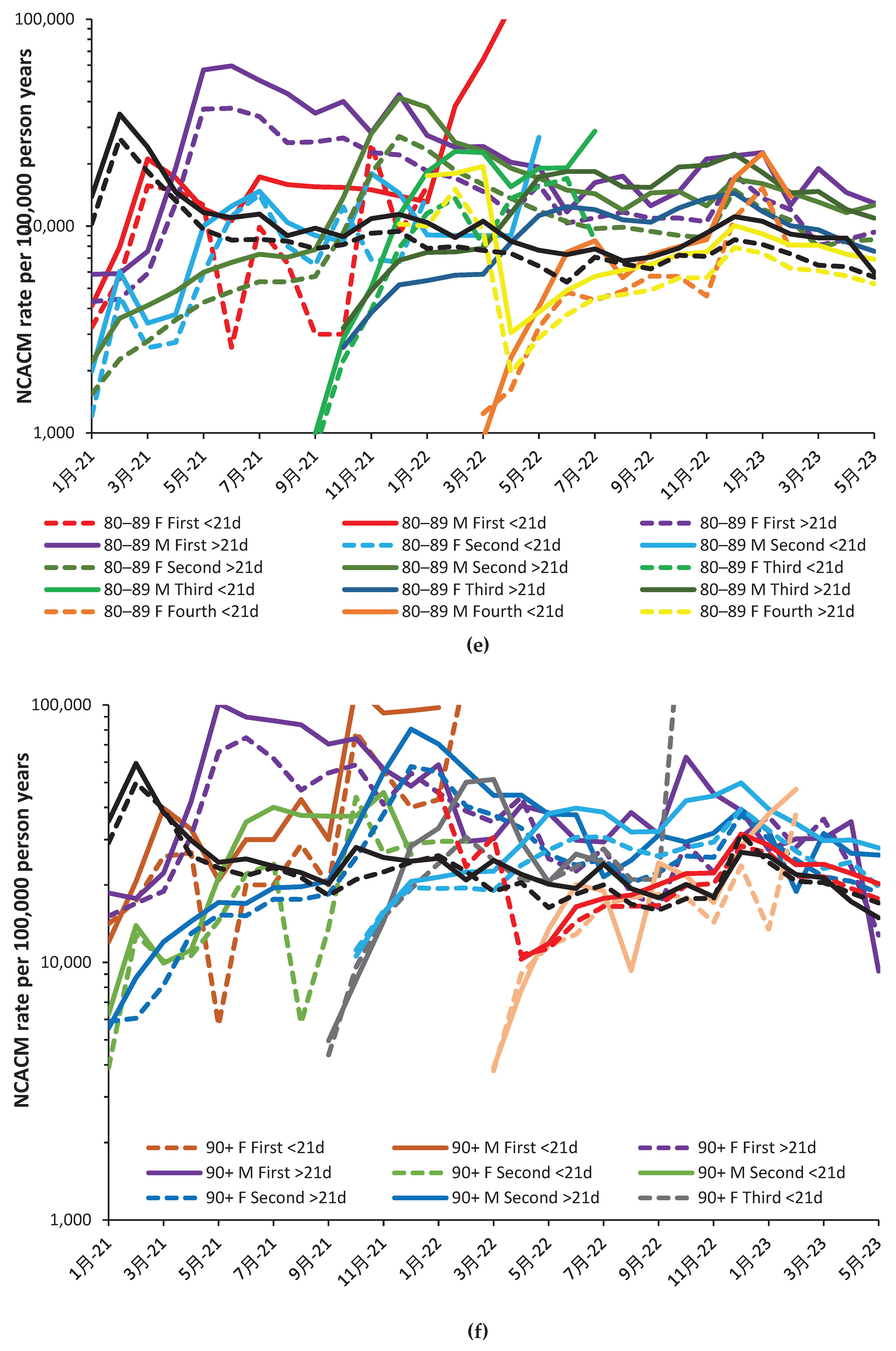

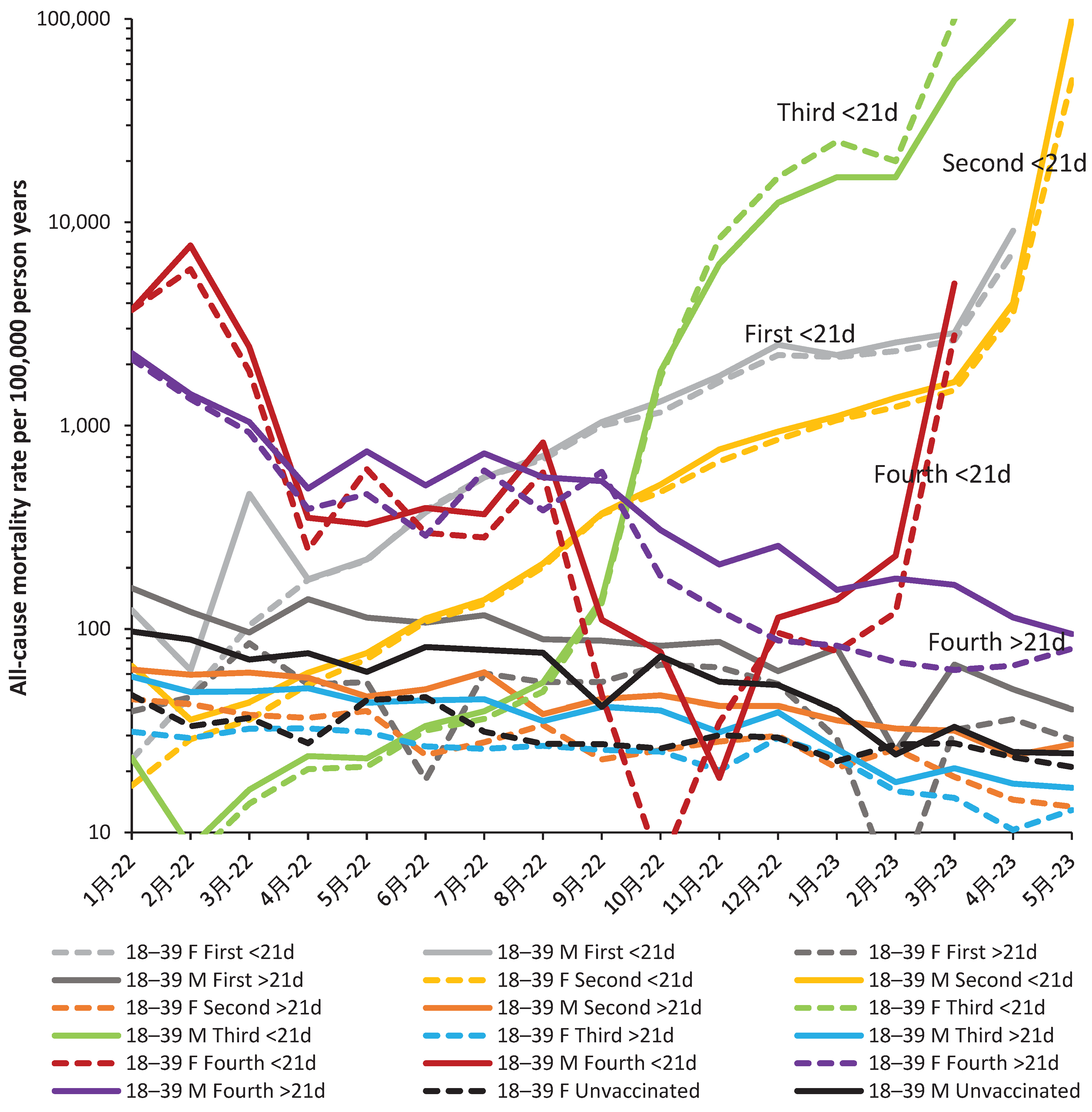

Figure 2.a and Figure 2.b show the NCACM rate for the vaccinated during the 21 days and >21 days post vaccination and corresponding unvaccinated NCACM rate. This is shown for the youngest age group, namely, 19–39 years. Note that in both Figure 2.a and Figure 2.b the month is the month of death rather than the month of vaccination. For the <21-day post vaccination group, the month of death and vaccination will be mostly identical. As a generalization the male rate is higher than that for females. The only exception is for the group who received their fourth dose earlier than the general population.

The <21-day post vaccination group has fewer data points because it only spans a 21-day period whereas the >21-day group can be for an extended duration, especially for persons who halted their vaccine journey after the first, second or third vaccine dose.

We understand that every data point is subject to statistical uncertainty and the reader is invited to use their knowledge of statistics to interpret the trends. While a 95% confidence interval exists in theory, visual inspection can quickly reveal questionable values. For example, unvaccinated male mortality in Sep-22 and Feb-23 looks to be low. On both occasions the data can be adjusted upwards to somewhere close to the two months on either side. Such an adjustment has a negligible effect on the overall conclusions. The same could be said for female first shot >21-day mortality in Jun-22, and for male first shot > 21-day mortality in Feb-23. Adjustment up to the average of the surrounding points likewise makes a minor effect on interpreting the overall chart, namely, nonspecific effects are highly prevalent.

Should you choose to question the validity of the unvaccinated as an ‘unbiased’ group you can simply shift the lines up or down, with inconsequential effects on interpreting the chart. All high values in the chart remain unquestioned because they are part of a continuous trend. Recall that all values is the real-world actual outcome. As can be seen in Figure 2.a the vaccination of males with their first dose continued through to March 2022. After this point so few are given their first dose that small numbers preclude meaningful analysis.

Few people aged 19–39 was given a fourth dose delivered mainly in October and November (Figure 2.b). Note that the corresponding charts for all other age groups are given in the Appendix Figure A3.1 to 3.6.

The main point is that in the absence of nonspecific effects the lines for the vaccinated and unvaccinated should be one and the same. This is clearly not the case. It would be interesting to review the reasons for early vaccination with the fourth dose from May to September 2023, and their associated risk factors. Whatever the case, they experienced very high mortality. It would be apposite if every NCAM death following the fourth dose in this age band was subject to a retrospective clinical review.

Note from Figure 2.a that outcomes for the second and third dose <21 days after vaccination are mostly beneficial. That for the first dose reaches maximum protection against NCACM in Jun-21, which is around the point of minimum levels of COVID-19 mortality (Figure 1.b.), implying that very low COVID-19 infection (even as asymptomatic), facilitates this type of nonspecific effect.

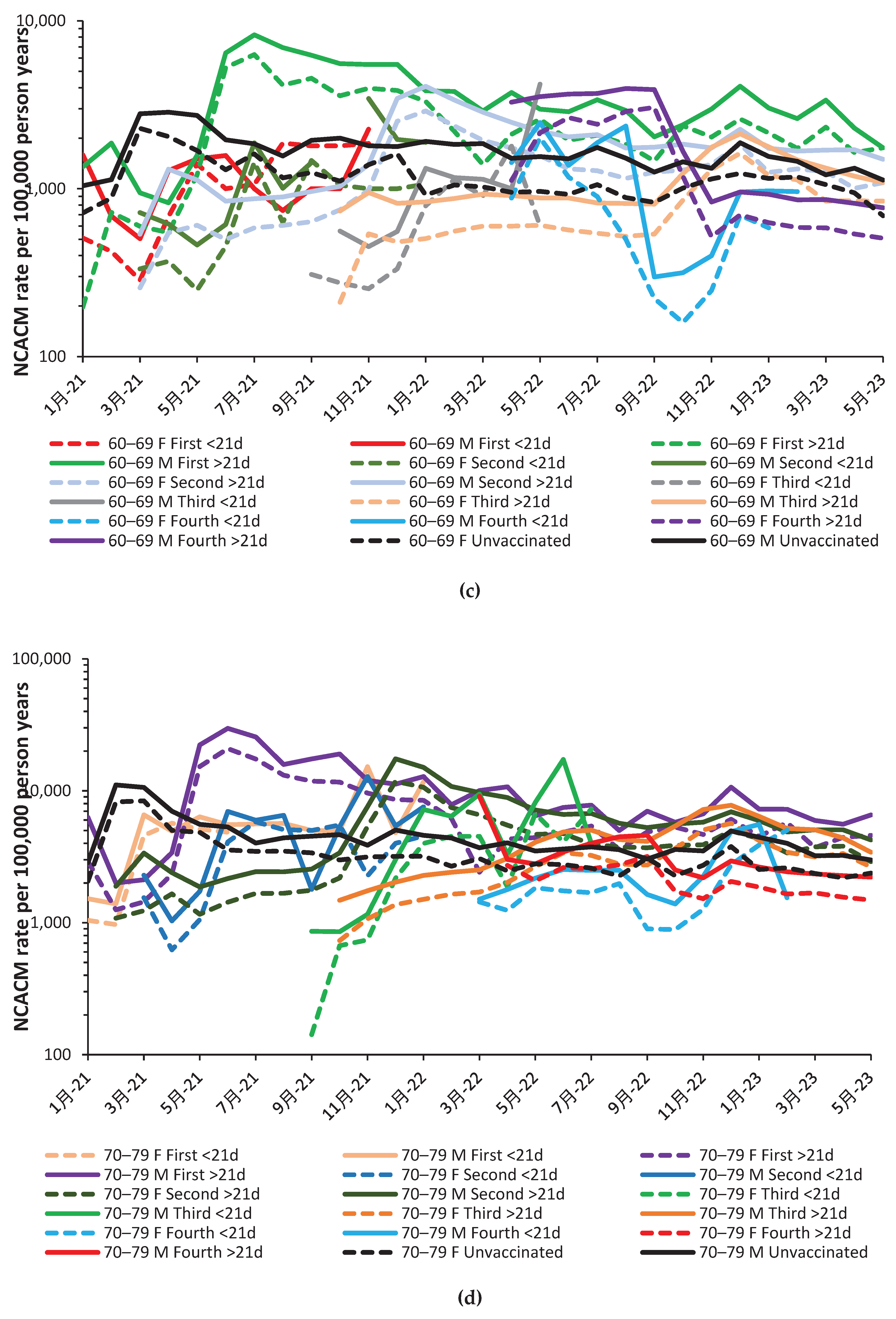

Graphs for the other age bands are given in the Appendix as Figure A2.a to Figure A2.f. Examples of nonspecific benefit/disbenefit are likewise observed which are age/gender specific. Recall that time represents transitions between COVID-19 variants, transitions between seasons, and fluctuation between high/low COVID-19 deaths (as in Figure 1.a. and Figure A1.b.)The significance of such transitions will be covered in the Discussion.

Based on Figure 2.a and Figure 2.b plus A2.a to A2.f, nonspecific effects do exist and that under different combinations of age/sex/COVID-19 variant/season/time since vaccination that these can be beneficial or give disbenefit. Figure 1 is therefore a composite derived from a complex set of highly dynamic interactions.

3.3. The timing of the nonspecific benefit of vaccination during the first 21 days

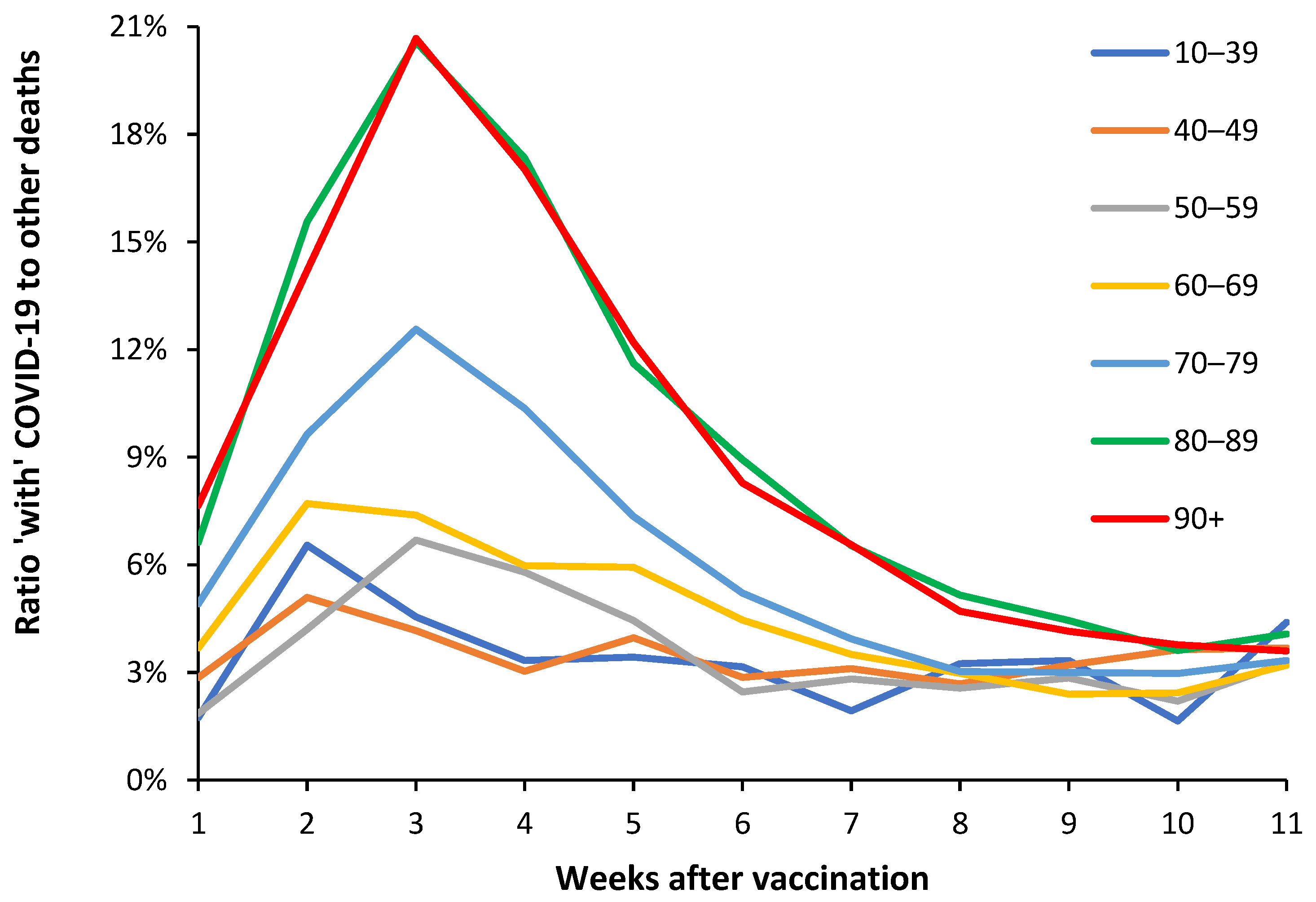

‘Table 9’ in the ONS data set covering the period January 2021 to May 2022 [40] provides a useful breakdown of both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 deaths during the first 11 weeks following vaccination. This material is summarized in Figure 3 as the ratio of ‘with’ COVID-19 deaths to other non-COVID-19 deaths. This is a composite picture from the first, second and third doses, and is not split by gender. During the first 11 weeks the data encompasses some 2068 deaths for the age 10–39 group, through to 78 925 in the age 80–89 group, and 53 723 in the age 90+ group.

This data is presented as a ratio of ‘with’ COVID-19 deaths to all other deaths. The ratio needs to be interpreted in the light of Figure 2.b which shows benefit against NCACM for the first 21 days (3 weeks) postvaccination, i.e., the denominator has been reduced.

Also, from Figure A1.b it should be noted that the ratio of COVID-19 to non-COVID-19 deaths is constantly changing over time and for the prevailing COVID-19 variant [25]. Depending on the sampling strategy employed by the ONS and the proportion of persons who received each of the three doses up to May-22, the magnitude but not the timing of the peaks seen in Figure 3 will be affected. However, when compared to Figure A1.b the 21% ratio of COVID-19 deaths in Figure 3 is far beyond anything possible from simple COVID-19 infection.

Somewhat surprisingly Figure 3 appears to reveal nonspecific disbenefit following vaccination relating to ‘with’ COVID-19 deaths. This disbenefit commences in the first week, while the maximum disbenefit occurs during the second week for ages <50 years, and during the third week for ages 80+ and some point between 2 to 3 weeks for ages 50–79. This disbenefit then diminishes and reaches a minimum after around 6 weeks in the younger groups, and up to 10 to 11 weeks in the two oldest age bands. Clearly the extent and timing of the disbenefit is age dependent.

Since this is a composite of different vaccine types, male/female and up to three different vaccine shots, more cannot be discerned, however, it confirms the fact of unanticipated nonspecific effects following COVID-19 vaccination and its age dependence. More detailed analysis using days rather than weeks, males/females, vaccine dose number, and vaccine type/manufacturer is highly recommended.

Antigen production can be excluded since this only occurs around 3 weeks after vaccination. Given the timescale for the increase in COVID-19 mortality we suspect enhancement of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection as the most plausible cause. COVID-19 is a multiorgan disease [43] and presumably asymptomatic or sub-clinical infections can be triggered to assume greater clinical severity. Further detail will be given in the Discussion.

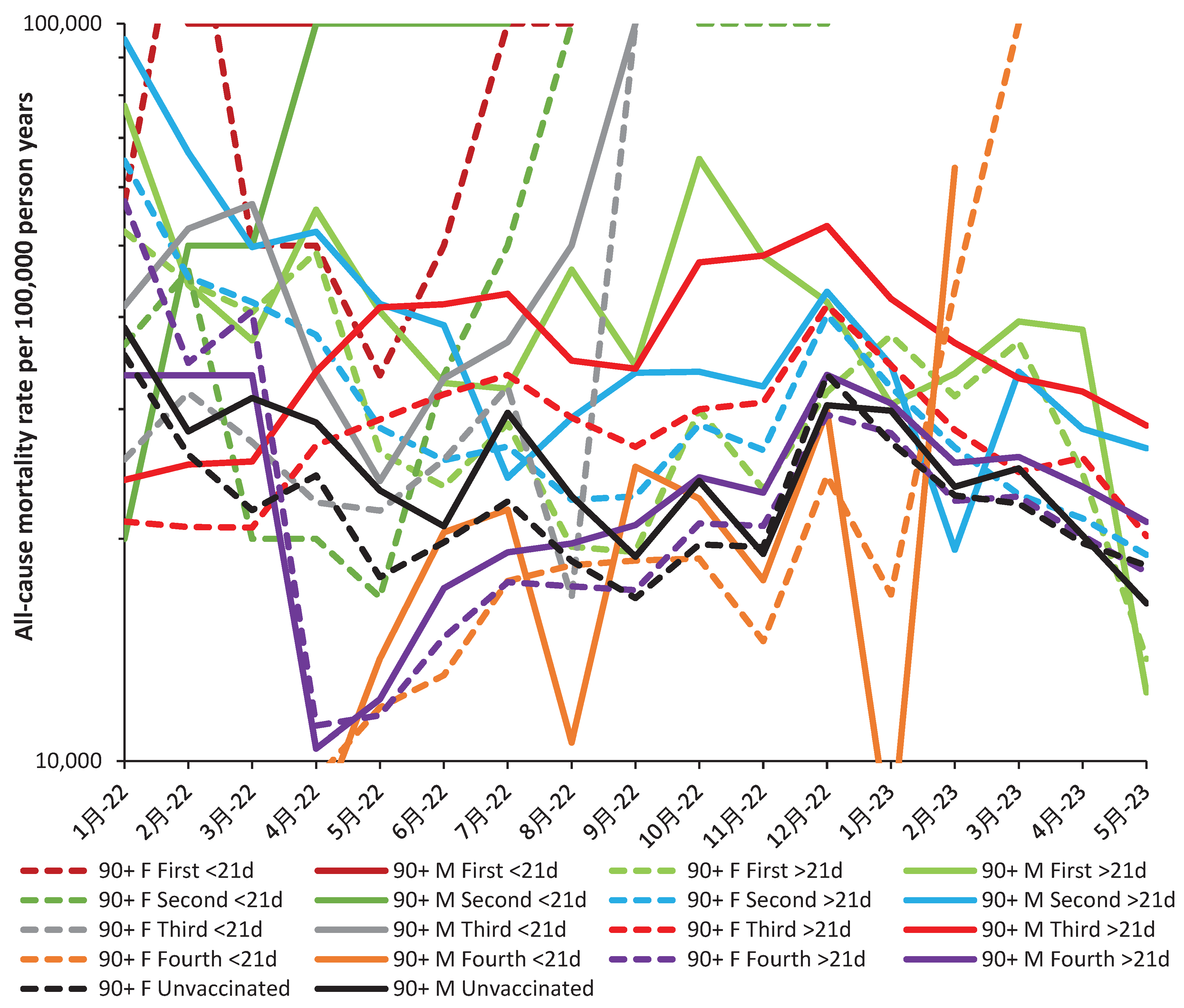

3.4. All-cause (including COVID-19) mortality during Omicron

Given the results in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure A2, and Figure 3 it is illustrative to look at the trend in all-cause (including COVID-19) mortality during Omicron. As shown in Figure A1.a. and Figure A1.b. the mortality rate during Omicron is very low, and especially below the age of 70. Depending on your point of view, the rationale for vaccinating ‘healthy’ persons below the age of 65 is a grey area. The Discussion presents the evidence suggesting that use of the experimental vaccines should have been tempered by the possibility of unanticipated disbenefit.

Hence, it is useful to look at the real-world outcomes. Reverting to all-cause mortality removes the issues surrounding subtracting COVID-19 from all-cause mortality to get NCACM. Plus, the number of deaths is slightly larger leading to lower statistical uncertainty. In addition, the net outworking of specific and nonspecific vaccine effects can be observed. The outcome is shown in Figure 4 which shows the results for age 18–39. Note that deaths from Omicron commence around March 2022 and the transition from the end of Delta is shown for context. A similar chart for age 90+ is shown in the Appendix as Figure A3.

Regarding statistical uncertainty, male unvaccinated mortality in Sep-22 looks to be a statistical outlier and is probably closer to August and October of 2022, as is observed for females. However, making such an adjustment negligible difference to interpreting the chart. Likewise, female mortality for the fourth dose <21 days in October 2022 looks to be an outlier, but adjustment to somewhere near to the values for September and November 2022 also makes a negligible effect on interpreting the chart.

Hence, all people receiving their first, second or third dose <21 days ago show increasing adverse outcomes beyond Mar-22, May-22, and Aug-22 respectively. The fourth dose <21 days only shows benefit around October/November 2022, but is otherwise not beneficial compared to their unvaccinated colleagues. The fourth dose >21 days is universally not beneficial, etc.

A similar story emerges for those aged 90+ in Figure A3. Somewhat curiously the disbenefit attached to the fourth dose >21 days appears to diminish with time. This could suggest that vaccine waning is behind this nonspecific effect.

As above, outliers can be quickly spotted, such as low values in August 2022 and January 2023 for males receiving their fourth dose <21 days ago. Adjustment upward turns benefit into borderline disbenefit. The overall observation is that over half of outcomes show disbenefit except for the fourth dose >21 day between April and August 2022 for both males and females. The fourth dose <21 days is generally beneficial up to February 2023, but then leads to disbenefit. The second dose <21 days shows a small benefit between March and May 2022, but otherwise shows disbenefit, etc.

As with NCAM a dynamic interaction between competing biological forces is evident which unfortunately is only revealed retrospectively. As noted in Figure 1 it is only the age groups 50–79 years which experience a greater proportion of benefit during the period beyond December 2022.

In conclusion, evidence for highly dynamic nonspecific effects from COVID-19 vaccination can be demonstrated. As expected from other vaccination studies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] there is a mix of benefit and disbenefit which appears to be highly dependent on the context. The exact balance of the forces can be demonstrated by comparing NCAM and all-cause mortality outcomes.

4. Discussion

The discussion includes a survey of explanatory literature and will attempt to present a whole system framework in which to interpret both the conclusions of this paper and other studies. It also seeks to emphasize roles for system complexity [4,19,20], and how this may contribute to nonspecific vaccine outcomes under specific conditions.

4.1. Factors driving complexity in COVID–19 mortality and the vaccine response

4.1.1. Declining vaccine effectiveness

Regarding Figure 1 the existence of negative vaccine effectiveness is not widely communicated to the public, but its occurrence is based on the antigenic distance between the vaccine and the current circulating variant or clade in the case of influenza [4].

Hence for influenza, a group meets under the auspices of the WHO to determine the antigen mix for the forthcoming influenza season in the southern and northern hemispheres and large numbers of vaccines are duly manufactured.

Sometimes a new clade emerges before the vaccine is administered which has too great an antigenic distance and the immune training via the vaccine diverts the resulting immune response to the production of futile antibodies which can lead to higher mortality in the vaccinated compared to the unvaccinated [4].

The reality of antigenic distance is poorly quantifiable and while it may be realized that the latest clade is antigenically distant, vaccination is still initiated under the hope that some similarity may exist. At present, we can only speculate regarding the basis for the nonspecific effects which may accompany antigenic distance, but simply observe that they do seem to exist. Whatever the mechanisms, they are highly dependent on combinations of sex, age, vaccine history and COVID-19 variant. A case of vaccination in the face of scientific uncertainty. A potential role for noncoding RNAs is discussed later.

Such expression is probably made more complex by the unique single-year-of-age profiles for COVID-19 mortality [25]. Evidence exists that influenza vaccines may likewise show single-year-of-age profiles [4]. Such profiles are totally obscured using broad age bands such as the 65+ age band universally used in influenza VE studies [4], and the confusing jumble of age bands employed in COVID-19 vaccine studies [25]. As a result, the newly emergent COVID-19 variants behave as if they were ‘different’ pathogens [44]. The presence of antigenic distance is reflected in declining vaccine effectiveness documented in studies conducted during the Delta and Omicron variants [45,46,47].

Thankfully at the third/booster dose the presence of negative vaccine effectiveness (in Figure 1) was not widespread for the bulk of the population who followed the standard fully vaccinated profile. At the fourth dose things appeared to be somewhat more complex.

4.1.2. COVID-19 variants show year of age specificity for mortality

It has been highlighted that COVID-19 variants show year of age specificity for death which is also dependent on sex. Such age specificity is primarily due to the variant and not the medical interventions because the age specificity abruptly changes with the arrival of each new variant [25], however, the shape of the primary age profile is modified to a degree by vaccination. Hence the Wuhan strain shows maximum mortality as a proportion of all-cause deaths at ages 83-89, the Alpha variant at ages 81-86, the Delta variant at ages 33-48, and the Omicron variant for ages above 67 years reaching a maximum at age around 100 [25].

The key point is that the molecular mechanisms for such age specificity are completely unknown. It has been proposed that small noncoding RNAs (miRNAs) may be involved, which are produced in response to nuances in the binding of the mutated spike protein to the ACE-2 receptor and ensuing entry into the cell [25]. Wider roles for miRNAs in both infection and vaccination are discussed later.

Given the unknown mechanisms behind the age specificity that vaccination (based upon the original Wuhan spike protein) may have been better (in hindsight) restricted to those ages showing the greatest number of COVID-19 deaths, and hence the greatest possible benefit [25]. The possibility existed that vaccination could behave in unexpected ways depending on age and variant, as has been demonstrated in this study.

4.1.3. Gene expression varies with season and latitude

Many health conditions, from psychiatric disorders to cardiovascular disease, show seasonal variation in severity and onset [48]. In one study 74 transcripts associated with a 12-month seasonal cycle were enriched for processes involved in DNA repair and binding. Another 94 showed significant seasonal variability that was associated with blood cell count levels. These transcripts were enriched for immune function, protein production, and specific cellular markers for lymphocytes. Cell counts for erythrocytes, platelets, neutrophils, monocytes, and CD19 cells demonstrated a significant 12-month seasonal cycle. Notable changes in leukocyte counts and genes involved in immune function indicate that immune cell physiology varies in a seasonal manner [48].

Another study showed that nearly a quarter of genes differ with season [49]. In Europe the immune system has a pro-inflammatory transcriptomic profile during winter, with increased levels of soluble IL-6 receptor and C-reactive protein which are risk biomarkers for cardiovascular, psychiatric, and autoimmune diseases that have peak incidences in winter [49]. This seasonality affects immune cells, the composition of blood and adipose tissue. The pattern of seasonal activity was not as strong in Iceland, while in Gambia peak expression occurred in the rainy season. The ARNTL gene which is most active in summer suppresses inflammation. In winter, those at greatest risk will reach the ‘threshold’ at which the disease becomes a problem more rapidly. A set of genes associated with the response to vaccination were more active in winter [49]. This may affect the response to COVID-19 vaccination depending on latitude and is highly relevant to the month-of-year patterns potentially involved in this study. Note from Figure A1.a. and Figure A1.2 that COVID-19 mortality shows a reasonably strong seasonal pattern.

As to be expected, small noncoding RNAs (miRNAs) are involved in the expression of seasonal diseases [50] – discussed next.

It is highly likely that seasonal patterns lie within the trends in this study, however, the timing for the arrival of new variants and the timescale of vaccination imposed by the need to vaccinate the whole nation has probably disrupted these patterns and additionally contributed to a portion of the observed variation.

Once again, the latitude dependance of gene expression implies that the results from England will show subtle differences to those derived from other countries.

4.1.4. The central role of small non-coding RNAs in gene expression

Some 80 % of the human genome is transcribed to RNA but only 2% of these are translated into proteins [51]. The other transcripts are defined as noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), including long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) and small noncoding RNAs (smRNAs). Small non-coding RNAs (microRNA, small nuclear RNA, small nucleolar RNA, tRNA derived small RNA and Piwi-interacting RNA) can be considered a relatively new class of molecule that are differentially regulated in many diseases [51]. The terms ‘micro’ and ‘small’ are seemingly used interchangeably in the literature.

It is estimated that there are around 2300 unique human miRNAs [652]. Each miRNA affects one or more genes, and a gene can be modulated by more than one miRNA [53,54], and miRNAs are estimated to regulate over 30% of mammalian genes [55].

ncRNAs are expressed in different tissues and cell types that can interact with target mRNAs, through base-pairing, to modulate gene translation [56,57]. miRNAs are powerful regulators of cellular activities including cell growth, development, proliferation and death, apoptosis, fat metabolism, mitochondrial function, neuronal patterning, hematopoietic differentiation, immune function, and epigenetic modification [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

All human diseases, including those associated with higher risk of COVID-19 disease, have an associated dysregulated miRNA profile [50,51,52,53,54,62,63,64,65,66], and all human pathogens have their own miRNA profiles coded into their genetic material [67,68,69,70,71]. Part of these pathogen encoded miRNAs are directed at interferon production and regulation, and hence pathogen interference [25,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. Hence profound changes in the proportions of pathogens and the frequency of mixed infections since the arrival of COVID-19 [81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89].

The outcomes of COVID-19 disease are associated with certain miRNA profiles [90]. Most importantly, all vaccines so far studied, lead to altered miRNA profiles, see 4.1.4, which has also been documented following COVID-19 vaccination [91]; covered in 4.1.6.

While the ability of vaccines to stimulate a large antibody response is a key part of the specific effects of vaccines, their ability to stimulate the production of ncRNAs, is a poorly investigated area and is probably central to understanding the diversity of vaccine outcomes observed in this study.

4.1.5. COVID–19 infection alters the miRNA landscape and ensuing gene expression.

In the absence of vaccines, infection by pathogens modify infection by other pathogens via pathogen interference, which has its basis in miRNA production and subsequent modification of gene expression including interferon production [4]. This is especially important in the clinical outcome of all respiratory infections [67,69,98].

There are now numerous studies regarding the effects of COVID-19 infection upon miRNA production, both by cells in response to the infection, and by SARS-CoV-2 to promote its own successful infection [99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110]. These studies include the effects on gene expression, altered biochemical pathways, interferon signaling, interaction with host mRNAs, and have demonstrated that various miRNAs appear associated with clinical severity including inflammatory and cytokine storm mechanisms [93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110]. One study has identified both chemokine (CC) CCL20, inflammatory cytokines IL6 and IL10, and miR-451a as key correlates of fatal COVID-19 [110], i.e., miRNAs are part of a wider whole system response.

Zhang et al [75] propose that that COVID-19 cleverly exploits the interplay between the miRNAs and other biomolecules to avoid being effectively recognized and attacked from host immune protection as well to deactivate functional genes that are crucial for immune function.

Dare we suggest that COVID-19 vaccination has unduly focused on antibody production which has ignored a vast regulatory machinery of potentially equal or greater importance. The role of miRNAs in the ‘real world’ success of vaccination has been largely ignored and is discussed later.

4.1.6. Interplay between interferons and miRNAs

It is of interest to note that severe COVID-19 disease patients mount a dysregulated interferon response compared to those with mild disease [80] and that the Omicron variant is less effective than Delta in antagonizing the interferon response in human cells [76]. Treatment with interferon-α, interferon-β, and interferon-γ revealed that the weaker interferon antagonism by Omicron translates into an increased Omicron sensitivity to interferon treatment [87]. These factors seemingly explain the reemergence of influenza due to altered pathogen interference upon the arrival of Omicron [111].

4.1.7. Nonspecific effects of vaccines

Given the implications of this study to the nonspecific effects of vaccines via ncRNAs and other heterologous mechanisms it is of interest to note the reported beneficial effects of prior BCG vaccination against COVID–19 infection [2,7,8,112,113]. Both influenzas, diphtheria, and tetanus vaccines have likewise been suggested to reduce serious COVID-19 outcomes [114]. Our unpublished research suggests that the nonspecific beneficial effects of influenza vaccine disappeared with the arrival of the Omicron variant. It is probably fair to say that many vaccinologists are unaware that vaccines alter the miRNA landscape with resulting nonspecific consequences.

In their recent review Diener et al [115] note regarding miRNAs that “their cellular effects are so numerous that off-target effects can hardly be avoided”.

Zhang et al [116] likewise point out that “One miRNA generally targets tens and even hundreds of genes. We named it “too many targets for miRNA effect” (TMTME). Further, two adverse events from the discontinuation of two miRNA therapeutics were exactly answered by TMTME. In summary, TMTME is inevitable because of the special complementary approach between miRNA and its target. It means that miRNA therapeutics would trigger a series of unknown and unpreventable consequences, which makes it a considerable alternative for application.”

While the ability of vaccines to stimulate a large antibody response is a key part of the specific effects of vaccines, their ability to stimulate the production of miRNAs, is also recognized but not widely appreciated.

Sufficient studies on the miRNA profiles generated in response to human vaccines have been published to support the notion that the profiles are specific to the vaccine type and its efficacy in individuals [117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125]. Circulating extracellular vesicles (EVs) deliver miRNAs to myeloid and lymphoid cells [122]. miR-21 levels in serum EVs also increase with aging and regulates the expression of IL-12 required for Th1 responses; therefore, EV miR-21 is expected to regulate vaccine efficacy [122]. miR-451a, another important miRNA [125], is abundant in serum EVs and controls the expression of cytokines, such as type I interferon and IL-6 [124].

In COVID-19 vaccination EV miR-92a-2-5p levels in sera were negatively correlated with degrees of adverse reactions, and EV miR-148a levels were associated with specific antibody titers [124].

A study of influenza vaccination in children up to 12 years of age revealed that 19 miRNAs were expressed at 21 days after receiving a pandemic (H1N1) vaccine. However, several miRNAs were expressed which were not present in existing RNA sequencing data [121]. As an example of nonspecific effects, in children and adolescents vaccinated with Pandemrix vaccine (a H1N1 influenza pandemic vaccine) the number of narcolepsy cases increased [118].

Our conclusion is that the COVID-19 vaccines based on the original Wuhan strain was reinforcing both immune and regulatory miRNA responses which were becoming increasingly unhelpful as COVID-19 variants emerged.

A recurring emphasis in the above studies are that the vaccine response is specific to the individual. Such an individual basis for COVID-19 risk will now be discussed.

4.1.8. A genetic basis for COVID–19 risk

Genomic distribution analysis reveals the highest density of miRNA sequences on the X chromosome [126]. This links directly to the lower risk of female death from COVID–19 infection [127] and to any miRNAs associated with chromosome 3 identified as a genetic risk factor. Likewise certain ACE2 gene polymorphs are associated with serious COVID-19 outcomes in men [128] and forms part of wider ACE2 genetic risk factors [129,130,131].

There is evidence that the risk of COVID–19 morbidity and mortality has a strong genetic basis centered around chromosome 3 mutations inherited from Neanderthals, hence, higher risk among various people groups, and certain blood groups [132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139]. Nakanishi et al [133] showed that chromosome 3 rs10490770 risk allele carriers had a 40% increased risk of all-cause mortality, 110% increased risk of severe respiratory failure, +70% venous thromboembolism, and +50% hepatic injury. Risk allele carriers aged under 60 years had higher odds of death or severe respiratory failure +170%, compared with +50% in those aged 60+. Among individuals younger than 60 years who died or experienced severe respiratory failure, 32% were risk-variant carriers [133]. The risk-associated DNA segment modulates the expression of several chemokine receptors, among them CCR5, a coreceptor for HIV which is down-regulated in carriers of the risk haplotype who also have a 27% lower risk of HIV infection [134,135]. Age dependence is relevant to this study. Lastly, it is important to emphasize that miRNAs are themselves subject to mutations with impact on inherited diseases [140].

The genetic factors imply that repeating the English vaccination study in another country may yield different outcomes depending on the constituent people groups. Given the exclusion of persons arriving in England after 2011 in the ONS data [40] this would imply immigration from the European Union (EU) countries, especially the Eastern European new EU members, is excluded. This affects mainly the younger age groups, although the magnitude of the people group effect is unknown.

4.1.9. Different responses between males and females

This study has established that males and females show different all-cause mortality outcomes both in the unvaccinated and the vaccinated, and that these responses are different between SARS-CoV-2 variants. This observation is unsurprising since sex is a biological variable that affects the functions of the innate and adaptive immune system. In their comprehensive review Klein & Flanagan [141] have demonstrated how the differing immune system responses change with age and are influenced by the reproductive status of the individual. Both sex chromosome genes and sex hormones differentially regulate immune responses. Environmental factors, including nutrition status and the composition of the microbiome, also alter the development and functioning of the immune system differently in males and females. Sex differences in immune responses result in differential susceptibility of males and females to infectious diseases, as well as affecting the outcome of vaccination [44,142].

A study regarding COVID-19 infection showed that male patients had higher levels of innate immune cytokines such as IL-8 and IL-18 along with a stronger induction of non-classical monocytes. Female patients had stronger T cell activation. A poor T cell response negatively correlated with patients' age and was associated with worse disease outcome in male patients. In females, higher levels of innate immune cytokines were associated with worse disease progression [143].

Another study showed that showed that the concentration of IgG antibody in mild, and recovering patients showed no difference between males and females. However, in severe status, there were more female patients having a relatively high concentration of serum SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody. The generation of IgG antibody in female patients was stronger than male patients in the early disease phase [144].

A Hungarian study showed that the ratio of male to female deaths changed between the Alpha and Delta waves. They observed statistically higher excess female deaths aged 55-64 during the Delta outbreak [145]. Inspection of their data indicates that the ratio of male to female deaths probably changed by age band in both the Alpha and Delta outbreaks which is consistent with our findings. Vaccination rates in Hungary during Delta were lower than in England indicating that the effect is probably dominated by the year of age profile of the variant [25] with possible additional vaccine interactions. Lastly, gender is associated with different miRNA profiles [146,147].

Our previous study on the year of age profiles for COVID-19 variants likewise highlighted the role of gender in the specific outcomes at different ages and for different birth cohorts [25].

4.1.10. Age and COVID–19 vaccination outcomes

Our previous studies regarding influenza vaccination highlighted issues surrounding the age at which ‘healthy’ individuals should be vaccinated [4,19,20]. This issue is linked to the single-year-of-age profile risk of death for different SARS-CoV-2 variants [25], and the observed single-year-of-age efficacy of influenza vaccines [4]. This whole area is poorly studied since most vaccine trials or vaccine effectiveness (VE) estimates do not have enough participants to detect the full nuances of age [4,19,25].

This study employs a collection of chronologic age-banded data. It is well recognized that chronologic and biological age are very different realities [148]. Hence it could be expected that the vaccination topography for each (chronological) age band may show blurring as in Figure 1, etc.

Another study found that while the average heritability of gene expression is consistent across tissues, the average contribution of age varies substantially. Furthermore, while the genetic regulation of gene expression is similar across tissues, age-associated changes in gene expression are highly tissue-specific in their action [149].

Changes in the mean and variance of gene expression with age have consequences for healthy aging and disease development. Up to 60% of age effects on transcription levels are shared across tissues, and 47% of those on splicing. Using gene expression variance and discordance between genetically identical MZ twin pairs, 137 genes with age-related changes in variance and 42 genes with age-related discordance between co-twins were identified [150], implying the latter are driven by environmental effects. These results show a complicated mix of environmental and genetically driven changes in expression with age. Additive genetic effects explain considerably more of the variance in gene expression than aging, but less that other environmental factors, potentially explaining why reliable expression-derived biomarkers for healthy-aging have proved elusive compared with those derived from methylation [150]. Coupled with the effects of genetic polymorphisms, early-life environmental exposures can give rise to substantial variation among individuals in their immune responses [151]. Gene expression implies the involvement of miRNAs.

The processes of aging are evident in human miRNA production. For example, miRNA-92a declines with age in CD3+CD8+CD62L+ cells and CD8+ T-lymphocytes. This suggests that the age-related attrition of human naïve T cells could be connected to a reduced miRNA-92a in T-lymphocytes and downregulation of the miRNA-92a level might indicate exhaustion of naïve T-cells due to alteration of the immunologic condition with aging, and hence in vaccine response [152].

Bera [153] reports that in Italy for children and adolescents receiving mRNA vaccine the risk of myocarditis and severe adverse events is much higher than the risk of COVID-induced admission to critical care. See Supplementary material S1.

The study of Nakanishi et al [133] noted that in those aged below 60 years the prediction of death or severe respiratory failure improved when including the rs10490770 risk allele (AUC 0·82 vs 0·84, p=0·016) and that the prediction ability of risk allele was similar or better than, most established clinical risk factors.

As noted in the Introduction, healthy children aged 5 ̶ 11 only begin to be vaccinated from February 2022 onward, i.e., during Omicron. Children with high clinical risk are vaccinated across the entire time range. Unfortunately, the detailed ONS data does not go below age 18 ̶ 39. However, Table 6 in the ONS data up to May 2022 [40] gives entire period data using 5-year age bands (male plus female) which can be aggregated at the level of any vaccine dose (first or more) to give enough deaths in the younger age bands. This appears to show adverse all-cause mortality vaccine outcomes for children aged 10-14 and 15-19 – all having received mRNA vaccine. This approach has limitations and wider international studies are recommended to fully disentangle age and vaccine type effects in the younger ages. Supplementary material S1 also contains an analysis of the all-cause mortality trends in children and young adults in England and Wales. Once again, those aged 15-19 appeared to undergo a large shift in all-cause mortality at the time when the mRNA vaccine was administered. A Hungarian study likewise indicated age/sex interactions in all-cause mortality following COVID-19 vaccination [145].

Dinetz [154] notes that as more of the younger population (under 40) are getting vaccinated, based on vaccine safety approvals, the real-world safety reporting data on adverse events have yet had time to catch up. He details three distinct neurological events that occurred after the Pfizer mRNA vaccine, without identifiable alternate etiologies, in patients with an average age of 36 years, all within eight weeks of one another. The cases occurred within hours of the second dose and, in one case, after the third booster dose of the vaccine.

These cases illustrate rising concerns of risks in widely recognized very low-risk age categories as shown in Supplementary material S1. These concerns are especially relevant given studies indicating that some types of COVID-19 vaccines may increase rather than decrease all-cause mortality [155]. In such cases the real-world safety reporting process will be missing a range of highly nuanced causes of death which are indirectly linked to vaccination.

Our study implies that the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination declined with younger ages. Supplementary material S1 presents preliminary analysis which suggests that ages 10-14 and 15-19 may have experienced a higher balance of all-cause mortality disbenefit compared to benefit. In a moving 52-week total chart (as in S1) a fundamental change in the rate of death is indicated by a change in slope, and the magnitude of the effect is revealed some 52 weeks after the fundamental change in slope, i.e., the change in slope represents the point of a sudden increase in population health state. Figure S1 covers both the vaccinated and unvaccinated, however, it is implied that age 15–19 as a group experienced a 30% to 40% increase in all-cause mortality, while age 10–14 experienced around a 40% increase in all-cause mortality. Further study is required to differentiate between the vaccinated and unvaccinated. Supplementary material S1 indicates that wider international studies should be instigated regarding the nonspecific all-cause mortality effects of COVID-19 vaccination in young adults and children. We are not suggesting that COVID-19 vaccination did not prevent COVID-19 mortality per se — although at such young ages COVID-19 mortality was extremely low. We are merely pointing out that all-cause mortality seems to tell a conflicting story with potential roots in nonspecific effects.

4.1.11. Simultaneous benefit/disbenefit

Figure 1showed a continuous gradient against all-cause mortality ranging from benefit through to disbenefit. This suggests that the effects of vaccination in general may be the net effect of benefit and disbenefit.

A recent study suggests that the same may occur for the nonspecific effects of influenza vaccination [4]. Hence at a theoretical 100% vaccination rate in persons aged 65+, influenza vaccination was associated with outcomes ranging from a 6% reduction in all-cause winter mortality in 2003/04, no effect in 2009/10, and to an increase of 7.5% in 2014/15 [4]. There was no apparent correlation between the specific measure of Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) and the nonspecific effect against all-cause mortality.

One of the nonspecific effects of influenza vaccination emerges in children and the elderly by which influenza infection is diminished by influenza vaccination, however, influenza is simply replaced by alternative pathogens [4]. The resulting all-cause mortality effect then depends on which other pathogens are most prevalent in that winter and location [4]. A similar effect may occur after COVID-19 vaccination but has not yet been investigated.

These suggest that the outcomes are a balance between the proportion of individuals who experience benefit against those who experience disbenefit – perhaps due to genetic and other factors. In this respect all the results shown in this, and other studies, are ‘average’ outcomes from population-wide studies – although our study uses far greater subdivision including time to reveal the hidden nonspecific complexity.

4.1.12. COVID-19 prophylactic therapy and mortality

Throughout the pandemic there has been an ongoing process of improvements in COVID-19 management and therapy [156], which has reduced the mortality rate. This has been an ongoing process and applies to both the vaccinated and unvaccinated who require hospital treatment, i.e., it affects both the numerator and denominator, and as such should not greatly affect the study outcomes.

However, miRNAs are recognized to respond to both illegal and medicinal drugs [157,158], are involved in nonspecific therapeutic success [159], and adverse drug reactions [165]. The changing therapeutic approach to COVID-19 management therefore adds another layer into the complexities of miRNA profiles and their outworking especially regarding interactions with SARS-CoV-2 variants.

4.1.13. The 21-day break point to characterize vaccine time-related effects

All vaccines have time related effects including the build-up of antibodies and subsequent vaccine waning. For example, the vaccine effectiveness (VE) for the 2021/22 flu vaccine declined to zero in the interval 120-149 days after vaccination [160]. Antibody levels are said to reach their maximum at around 21 days after vaccination and COVID-19 spike antibody levels start waning after around 6 weeks [161].

The ONS 21-day break point is therefore a pragmatic choice. However, the effects against all-cause mortality up to 21 days are more complex and were shown in greater detail in Figure 3.

The situation regarding higher apparent COVID-10 mortality during the first 21 days has been recognized by others [161,162,163,164], and the US CDC does not count a person as ‘vaccinated’ until 14 days after vaccination [163]. It is claimed that higher infection is due to persons wrongly behaving as if vaccination was fully effective from day one [163,164]. We dispute this simplistic explanation since in Figure 3 the effect increases with age. The propensity to lower adherence to social distancing , etc., increases with lower age, which is the reverse of Figure 3. We propose that nonspecific activation of otherwise asymptomatic COVID-19 infection may be the real cause.

It is unlikely that such effects are due to the absence of antibodies during the first 21 days. In this respect, it is important to understand the totality of changes occurring in the days after vaccination.

A study (Houston, USA) in the response to influenza vaccination (Sanofi 2008/09 trivalent vaccine) among healthy Caucasian males aged 18-40 years showed the following notable patterns [165]

- Maximum gene expression (up/down-regulation) occurred 1 to 3 days after vaccination. This implies rapid production of miRNAs prior to gene regulation.

- Three groups of genes were regulated, namely early and late upregulation, and downregulation.

- Different patterns of genes are expressed in high/medium/low antibody responders. High vaccine responder status correlates with increased early expression of interferon signaling and antigen processing and presentation genes.

- The expression of early activation genes strongly correlated with antibodies at 14 and 28 days after vaccination.

This study was focused entirely on antibody production and somewhat glossed over the fact that the expression patterns of numerous genes were changed which could be a partial explanation of the higher COVID-19 mortality in the first 21 days – under a particular set of conditions.

A study of COVID-19 vaccination using an mRNA vaccine showed peak IgG production at 40 days for doses 1-3, and at 30 days for the fourth dose. Peak response for IgA production was more complex with an early peak at 15-20 days followed by a minimum at 25 days and then another peak around 40 days (slightly earlier for the fourth dose). Rapid waning in production then occurred through to 80 days after vaccination [166].

Another study conducted in the UK using mRNA and a virus vector vaccines showed a peak in IgG levels irrespective of age around 21 days after natural infection, first dose or second dose, followed by antibody waning depending on natural or vaccine acquired immunity [167]

All the above studies focused on antibody production with a possibility of lower protection as antibody levels increase over the first 21 days, but no explanation as to why non-COVID-19 all-cause mortality could be simultaneously reduced. Causes for the increased COVID-19 mortality outside of antibody levels are therefore implicated.

A Norwegian study regarding vaccination during the Alpha variant for persons aged 70+ claimed increasing protection from day 1 onwards [168]. This seemingly contradicts the known biology of antibody production discussed above but concurs with our study where a degree of nonspecific protection does occur for the first 21 days (as a block of time), especially during Alpha and less so during Delta.

A Dutch study (mRNA vaccine) showed no short-term mortality effects for the third dose given to ages 19+ during the first Omicron wave, however, during the fourth dose delivered to age 60+ in the absence of an Omicron wave there was a significant short-term rise in all-cause mortality [169], especially shortly after vaccination. This implicates roles for miRNAs and inflammatory responses to mRNA vaccines (discussed later) under conditions where Omicron infections are low. This Dutch study concurs with our results during Omicron.

It is unknown how the three different vaccines available for the data in Figure 3 affected the ratio. It is also unknown exactly how the numerator and denominator change during the first 21 days. Section 4.2.4. is also highly relevant to the complex issues involved in the first 21 days. We appear to be dealing with a mix of specific and nonspecific vaccine effects.

For all-cause mortality, we suggest that whatever is happening in the first 21 days is not primarily related to human behavior, because it is worse in the older age groups who are more conservative in their behavior and is generally most common with Omicron. This whole issue requires greater investigation since it is clearly multidimensional regarding causes. Given the large amount of monthly data available for this study the question arises as to whether similar behavior occurs after influenza vaccination but has remained hidden. Such behavior may depend on the year of vaccination [4].

We conclude that the timeline from day zero of vaccination requires more detailed study regarding sex/age/vaccine stage/variant issues.

4.1.14. miRNA expression is highly dynamic

Given the highly dynamic nature of all the Figures in this study, any proposed regulatory mechanism must show rapid responses to nuanced changes. miRNAs do meet this criterion. For example, in a mouse model the miRNA transcriptome undergoes state-transition during acute myeloid leukemia initiation and progression, with potential to predict disease trajectory [170]. Generation of expanded and activated NK cells involved changes in the expression of 64 miRNAs with highly significant changes in 7 all involved in both up/down gene regulation [171]. In patients undergoing rectal cancer treatment those who respond to therapy show a progression in miRNA profile to an eventual non-cancer baseline, while those resistant to treatment do not [172].

Hence, we propose that miRNA expression is likely to lie behind the highly dynamic responses to vaccination observed in this study.

4.2. Differences between mRNA and other vaccines

Given the transition away from the AstraZeneca (virus vector) vaccine in the UK, especially among young adults (moved to mRNA), it is of interest to see if this may have influenced the results of this study. Several studies are available which address the issue of COVID–19 vaccine type upon all-cause mortality.

4.2.1. General studies

Benn et al [155] appraised the randomized control trials (RCTs) of mRNA and adenovirus-vector vaccines reporting overall mortality, including COVID–19 deaths, accident deaths, cardiovascular deaths and other non-COVID–19 deaths. For overall mortality, with 74,193 participants and 61 deaths (mRNA:31; placebo:30), the relative risk (RR) for the two mRNA vaccines compared with placebo was 1.03 (95% CI=0.63-1.71). In the adenovirus-vector vaccines there were 122,164 participants and 46 deaths (vaccine:16; controls:30). The RR for adenovirus-vector vaccines versus placebo/control vaccine was 0.37 (0.19-0.70). The adenovirus-vector vaccines were associated with protection against COVID–19 deaths (RR=0.11 (0.02-0.87)) and non-accident, non-COVID–19 deaths (RR=0.38 (0.17-0.88)). They argue for performing RCTs of mRNA and adeno-vectored vaccines head-to-head comparing long-term effects on overall mortality. The study of Ben et al [155] confirms the results of a much larger Hungarian all-cause mortality studies which contained over 6 million participants after exclusion of partly vaccinated individuals [45,173].

Several other studies have implicated COVID-19 vaccination in increased all-cause mortality. These studies have used different methods, countries, age groups, and time periods covering different COVID-19 variants, different vaccine histories, and time following vaccination [174,175,176,177,178,179]. A common theme was the involvement of mRNA vaccines, and poor outcomes in children and young adults. While some of these studies may be flawed, the point is that they cannot all be wrong, and that they broadly confirm that such a possibility exists. Once again, no one is questioning the ability of COVID-19 vaccines to protect against COVID-19 per se. It is the issue of all-cause mortality that is problematic.

In view of the possibility that mRNA vaccines may be associated with adverse all-cause mortality two reviews of potential adverse effects from mRNA vaccination raised a number of issues which could impact long-, medium- and short-term all-cause mortality [180,181]. Other studies have raised concerns around neurological side-effects, reverse transcription, and toxicity of the naked spike protein [182,183,184,185,186,187,188].

Given the emphasis on the regulatory role of miRNAs in this study the possibility has been raised that the mRNA from the vaccine will bind to cellular miRNAs thereby interfering in unexpected ways with cell regulation [189,190]. A comprehensive review of the potential immunological and biochemical effects of mRNA vaccines against innate and other immunity, and miRNA regulation, identified potential disturbances in regulatory control of protein synthesis and cancer surveillance with a possible causal link to neurodegenerative disease, myocarditis, immune thrombocytopenia, Bell's palsy, liver disease, impaired adaptive immunity, impaired DNA damage response and tumorigenesis [181]. While some of these concerns may be proved to be unwarranted, they nevertheless may provide further explanations for some of the adverse nonspecific effects seen in this study.

The next section explores all-cause mortality differences between different types of COVID-19 vaccines.

4.2.2. All-cause mortality differences between vaccines

A Hungarian study with comprehensive risk adjustment showed that the magnitude and post vaccination trajectory of all-cause survival after COVID–19 vaccination during the Alpha wave varied markedly between COVID vaccine manufacturers [45].

Taking survival at 21 days during the epidemic period (April to June 2021), which is the break point in the ONS vaccination data for England [40], all vaccines deliver protection, however all-cause survival is highest for Janssen (viral vector) followed equally by Sputnik and AstraZeneca (both viral vector). Next is Sinopharm (inactivated whole virus) and then lowest protection equally by Moderna and Pfizer (both mRNA) [45]

However, 80-day survival during the epidemic period) was highest for Janssen (viral vector), Sputnik (viral vector) and AstraZeneca (viral vector). Moderna (mRNA) had a worse all-cause mortality outcome than the unvaccinated, while Pfizer (mRNA) was equal to the unvaccinated, while Sinopharm (inactivated whole virus) was slightly better than the unvaccinated [45]. Survival for the Moderna vaccine had dropped below the unvaccinated around day 65, while that for Pfizer had fallen to that for the unvaccinated at day 80. During the non-epidemic period (55-day survival), Moderna was once again worse than the unvaccinated, while Pfizer was very close to the unvaccinated. Sputnik had by far the highest survival, then followed by AstraZeneca and Janssen. Sinopharm was once again intermediate [45].

Hence all viral vector vaccines gave highest long-term all-cause survival while mRNA vaccines gave no better protection or worse than the unvaccinated after waning. Inactivated whole virus was intermediate.

4.2.3. Specific and nonspecific effects of vaccine waning

Waning is a part of the real-world effects of both influenza [174,] and COVID-19 vaccination [161,173,191,192,193,194,195]. The waning of efficacy after COVID–19 vaccination will mostly affect the >21 days after vaccination group in the various Figures in this study, with higher reduction in the all-cause rate relative to the unvaccinated generally, but not always, occurring in this group.

A large population study in Israel demonstrated that rates of reinfection were highest following mRNA (Pfizer) in the two-dose cohort at 6 to 7 months after vaccination (88 infections per 100 000 person days), but only 15 infections per 100 000) for the unvaccinated or one dose/recovered hybrid group after 6 to 7 months, 10 for the recovered/one dose hybrid group [192,193]. At >12 months after infection the recovered/unvaccinated cohort were still only showing 30 infections per 100 000 person days. At up to 1 month the three-dose cohort had higher than 2-times the infection rate of the recovered/one dose cohort [192,193]. Seemingly far better protection is afforded in the hybrid group and vaccine waning is steep for the vaccine-only group which confirms the results reported in Hungary [173].

Another UK population-based study investigating COVID-19 related hospitalization or death (not all-cause mortality ) found that following doses 1 and 2 of the AstraZeneca vector and dose 1 of the Pfizer mRNA the outcomes reached zero protection by approximately days 60–80 and then went negative. By Day 70, VE/rVE was –25% and 10% for doses 1 and 2 of AstraZeneca, respectively, and 42% and 53% for Doses 1 and 2 of Pfizer respectively. rVE for dose 2 of Pfizer remained above zero throughout and reached 46% after 98 days of follow-up [194]. This study broadly confirms potential negative vaccine effectiveness; however, it only covers COVID-19 confirmed hospitalization or death, i.e., not all-cause mortality.

A study in Hungary during the Delta outbreak (Sep-21 to Dec-21) showed that vaccine waning occurred after the primary vaccine dose (delivered before Delta) such that Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) for COVID-19 death at >240 days had fallen to between 80% (Sputnik, Moderna) and 50% (Sinopharm, Astra Zeneca) [145]. Hence the specific effects of COVID-19 vaccines show no evidence of a transition to negative VE.

On the other hand, during the earlier Alpha outbreak in Hungary the profiles regarding all-cause mortality were vastly different. During the Alpha epidemic period (Apr-21 to Jun-21) both Pfizer and Moderna (mRNA vaccines) led to increased all-cause mortality (negative VE) beyond 65 days (Moderna) and 80 days (Pfizer). Vaccination during the non-epidemic period (Jun-21 to Aug-21) showed far greater waning with Moderna offering no protection up to 27 days and increased all-cause mortality beyond 27 days. Pfizer was slightly better up to 60 days post vaccination after which negative VE was likely [173]. None of the other vaccines (Sputnik, Astra Zeneca, Sinopharm, Janssen) showed any evidence for long-term decay into negative VE. Our study appears to confirm these results.