Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pathogenesis

3. Extrarenal Cystic Manifestations

3.1. Liver

|

|

3.2. Pancreas and Spleen

3.3. Other Involvements

4. Extra-Renal Non Cystic Manifestations

4.1. Vascular

4.2. Brain

4.3. Heart

4.4. Bone

5. Conclusions

- ADPKD is a systemic disease that can involve several districts with cystic and non cystic involvement

- Despite kidney remains the main clinical feature, liver, vascular, heart and bone involvement could impact on patient’s quality of life

- Liver volume is a prognostic marker and it impacts both on symptom burden and quality of life

- IA rupture is the most serious complication that can occour in ADPKD patients. Early detection and appropriate treatment is highly desirable

- Although valvular abnormalities are common in ADPKD patients, rarely leads to clinical problems therefore screening echocardiography is not compulsory

- Bone defect in individuals with ADPKD aligns with adynamic bone disorder and it appears since earliest stages of CKD.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interests

References

- Cornec-Le Gall, E.; Alam, A.; Perrone, R.D. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet 2019, 393, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornec-Le Gall, E.; Torres, V.E.; Harris, P.C. Genetic Complexity of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney and Liver Diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018, 29, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besse, W.; et al. Mutation Carriers Develop Kidney and Liver Cysts. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019, 30, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopp, K.; et al. Functional polycystin-1 dosage governs autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease severity. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 4257–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantinga-van Leeuwen, I.S.; et al. Lowering of Pkd1 expression is sufficient to cause polycystic kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet 2004, 13, 3069–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossetti, S.; et al. The position of the polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD1) gene mutation correlates with the severity of renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002, 13, 1230–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, S.; Harris, P.C. Genotype-phenotype correlations in autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007, 18, 1374–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, C.; et al. Polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrier, R.W. Renal volume, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, hypertension, and left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009, 20, 1888–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, D.; Chapman, A.B. Cystic and inherited kidney diseases. Am J Kidney Dis 2003, 42, 1305–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantham, J.J. Clinical practice. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2008, 359, 1477–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.Y.; Park, J.H. Genetic Mechanisms of ADPKD. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016, 933, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horani, A.; Ferkol, T.W. Understanding Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia and Other Ciliopathies. J Pediatr 2021, 230, 15–22.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.R. The evolution of eukaryotic cilia and flagella as motile and sensory organelles. Adv Exp Med Biol 2007, 607, 130–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nauli, S.M.; Jin, X.; Hierck, B.P. Jin, and B.P. Hierck, The mechanosensory role of primary cilia in vascular hypertension. Int J Vasc Med 2011, 2011, 376281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdul-Majeed, S. and S.M. Nauli, Calcium-mediated mechanisms of cystic expansion. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1812, 1281–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauli, S.M. and J. Zhou, Polycystins and mechanosensation in renal and nodal cilia. Bioessays 2004, 26, 844–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspary, T., C. E. Larkins, and K.V. Anderson, The graded response to Sonic Hedgehog depends on cilia architecture. Dev Cell 2007, 12, 767–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.T.; et al. The primary cilium coordinates signaling pathways in cell cycle control and migration during development and tissue repair. Curr Top Dev Biol 2008, 85, 261–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes, J.M., E. E. Davis, and N. Katsanis, The vertebrate primary cilium in development, homeostasis, and disease. Cell 2009, 137, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satir, P., L. B. Pedersen, and S.T. Christensen, The primary cilium at a glance. J Cell Sci 2010, 123, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praetorius, H.A. and K.R. Spring, Removal of the MDCK cell primary cilium abolishes flow sensing. J Membr Biol 2003, 191, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauli, S.M.; et al. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat Genet 2003, 33, 129–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauvet, V.; et al. Expression of PKD1 and PKD2 transcripts and proteins in human embryo and during normal kidney development. Am J Pathol 2002, 160, 973–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya, O.; et al. Polycystin: in vitro synthesis, in vivo tissue expression, and subcellular localization identifies a large membrane-associated protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 6397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huan, Y. and J. van Adelsberg, Polycystin-1, the PKD1 gene product, is in a complex containing E-cadherin and the catenins. J Clin Invest 1999, 104, 1459–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, T.; et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science 1996, 272, 1339–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Perrett, S.; et al. Polycystin-2, the protein mutated in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), is a Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 1182–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoder, B.K., X. Hou, and L.M. Guay-Woodford, The polycystic kidney disease proteins, polycystin-1, polycystin-2, polaris, and cystin, are co-localized in renal cilia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002, 13, 2508–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; et al. Structural and molecular basis of the assembly of the TRPP2/PKD1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 11558–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, P.M.; et al. Polycystin-2 is a novel cation channel implicated in defective intracellular Ca(2+) homeostasis in polycystic kidney disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001, 282, 341–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nims, N., D. Vassmer, and R.L. Maser, Transmembrane domain analysis of polycystin-1, the product of the polycystic kidney disease-1 (PKD1) gene: evidence for 11 membrane-spanning domains. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 13035–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiokas, L.; et al. Homo- and heterodimeric interactions between the gene products of PKD1 and PKD2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 6965–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, F.; et al. PKD1 interacts with PKD2 through a probable coiled-coil domain. Nat Genet 1997, 16, 179–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, A.R., G. G. Germino, and S. Somlo, Molecular advances in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2010, 17, 118–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulen, P.; et al. Polycystin-2 is an intracellular calcium release channel. Nat Cell Biol 2002, 4, 191–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyatonwu, G.I. and B.E. Ehrlich, Organic cation permeation through the channel formed by polycystin-2. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 29488–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyuk, A.I.; et al. Cholangiocyte cilia detect changes in luminal fluid flow and transmit them into intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 911–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masyuk, T.V.; et al. Octreotide inhibits hepatic cystogenesis in a rodent model of polycystic liver disease by reducing cholangiocyte adenosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1104–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kip, S.N.; et al. [Ca2+]i reduction increases cellular proliferation and apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells: relevance to the ADPKD phenotype. Circ Res 2005, 96, 873–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banizs, B.; et al. Altered pH(i) regulation and Na(+)/HCO3(-) transporter activity in choroid plexus of cilia-defective Tg737(orpk) mutant mouse. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007, 292, C1409–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shillingford, J.M.; et al. The mTOR pathway is regulated by polycystin-1, and its inhibition reverses renal cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 5466–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, A.K.; et al. PKD1 induces p21(waf1) and regulation of the cell cycle via direct activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in a process requiring PKD2. Cell 2002, 109, 157–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; et al. Polycystin-2 down-regulates cell proliferation via promoting PERK-dependent phosphorylation of eIF2alpha. Hum Mol Genet 2008, 17, 3254–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, E.; et al. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet 2006, 38, 21–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossetti, S.; et al. Comprehensive molecular diagnostics in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007, 18, 2143–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hateboer, N.; et al. Comparison of phenotypes of polycystic kidney disease types 1 and 2. European PKD1-PKD2 Study Group. Lancet 1999, 353, 103–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, S. and P.C. Harris, The genetics of vascular complications in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). Curr Hypertens Rev 2013, 9, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Y.; et al. A missense mutation in PKD1 attenuates the severity of renal disease. Kidney Int 2012, 81, 412–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornec-Le Gall, E.; et al. Type of PKD1 mutation influences renal outcome in ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013, 24, 1006–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, H.C. and M.J. Caplan, The cell biology of polycystic kidney disease. J Cell Biol 2010, 191, 701–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, F.; et al. The molecular basis of focal cyst formation in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease type I. Cell 1996, 87, 979–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watnick, T.J.; et al. Somatic mutation in individual liver cysts supports a two-hit model of cystogenesis in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Mol Cell 1998, 2, 247–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Y.; et al. Somatic PKD2 mutations in individual kidney and liver cysts support a "two-hit" model of cystogenesis in type 2 autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999, 10, 1524–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevers, T.J. and J.P. Drenth, Diagnosis and management of polycystic liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013, 10, 101–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roskams, T. and V. Desmet, Embryology of extra- and intrahepatic bile ducts, the ductal plate. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2008, 291, 628–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynaud, P.; et al. Biliary differentiation and bile duct morphogenesis in development and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2011, 43, 245–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strazzabosco, M. and L. Fabris, Development of the bile ducts: essentials for the clinical hepatologist. J Hepatol 2012, 56, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drenth, J.P., M. Chrispijn, and C. Bergmann, Congenital fibrocystic liver diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010, 24, 573–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, V.J. , Ludwig symposium on biliary disorders--part I. Pathogenesis of ductal plate abnormalities. Mayo Clin Proc 1998, 73, 80–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roediger, R.; et al. Polycystic Kidney/Liver Disease. Clin Liver Dis 2022, 26, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, M.C.; et al. Liver involvement in early autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015, 13, 155–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, K.T.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of hepatic cysts in early autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: the Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006, 1, 64–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabow, P.A.; et al. Risk factors for the development of hepatic cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Hepatology 1990, 11, 1033–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Aerts, R.M.M.; et al. Severity in polycystic liver disease is associated with aetiology and female gender: Results of the International PLD Registry. Liver Int 2019, 39, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstha, R.; et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy selectively stimulates hepatic enlargement in women with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Hepatology 1997, 26, 1282–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chebib, F.T.; et al. Effect of genotype on the severity and volume progression of polycystic liver disease in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016, 31, 952–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aapkes, S.E.; et al. Estrogens in polycystic liver disease: A target for future therapies? Liver Int 2021, 41, 2009–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aerts, R.M.M.; et al. Estrogen-Containing Oral Contraceptives Are Associated With Polycystic Liver Disease Severity in Premenopausal Patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2019, 106, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, D.; et al. The intrahepatic biliary epithelium is a target of the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor 1 axis. J Hepatol 2005, 43, 875–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, D.; et al. Estrogens stimulate proliferation of intrahepatic biliary epithelium in rats. Gastroenterology 2000, 119, 1681–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koduri, S., A. S. Goldhar, and B.K. Vonderhaar, Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by the ER-alpha variant, ERDelta3. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006, 95, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauveau, D., F. Fakhouri, and J.P. Grünfeld, Liver involvement in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: therapeutic dilemma. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000, 11, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patch, C.; et al. Use of antihypertensive medications and mortality of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a population-based study. Am J Kidney Dis 2011, 57, 856–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orskov, B.; et al. Improved prognosis in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in Denmark. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010, 5, 2034–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orskov, B.; et al. Changes in causes of death and risk of cancer in Danish patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012, 27, 1607–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecder, T.; et al. Reversal of left ventricular hypertrophy with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in hypertensive patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999, 14, 1113–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

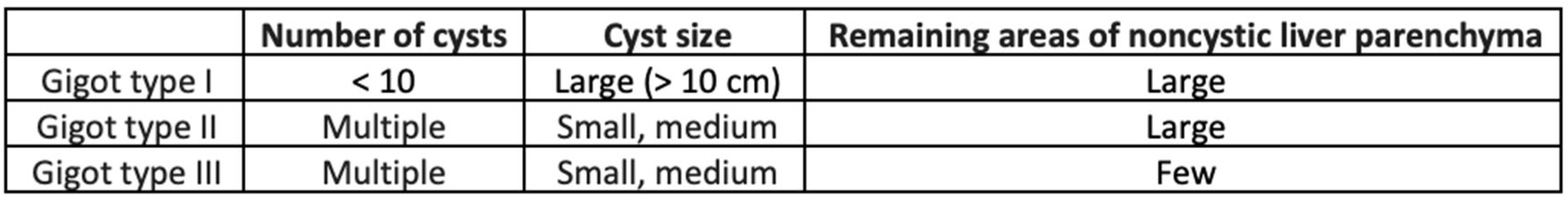

- Gigot, J.F.; et al. Adult polycystic liver disease: is fenestration the most adequate operation for long-term management? Ann Surg 1997, 225, 286–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnelldorfer, T.; et al. Polycystic liver disease: a critical appraisal of hepatic resection, cyst fenestration, and liver transplantation. Ann Surg 2009, 250, 112–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

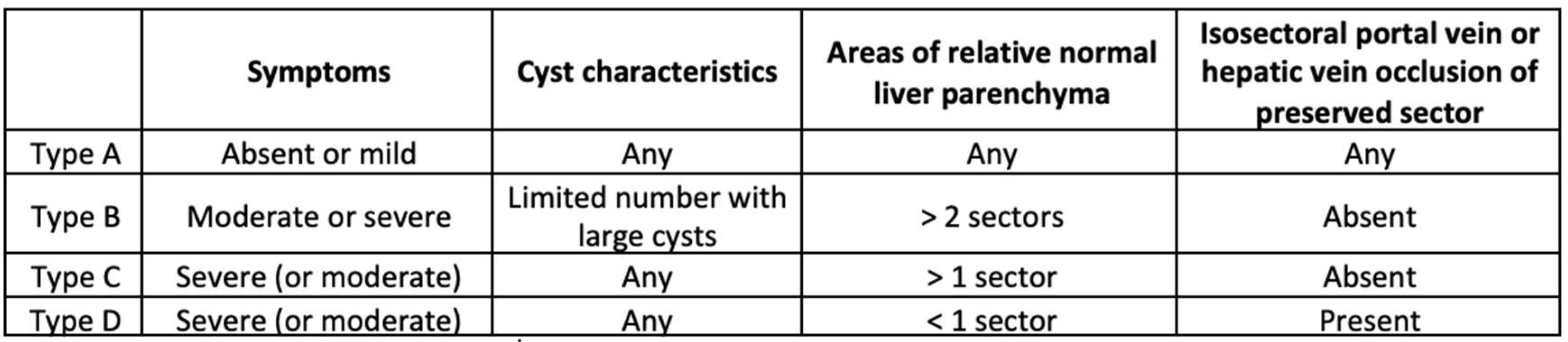

- Temmerman, F.; et al. Development and validation of a polycystic liver disease complaint-specific assessment (POLCA). J Hepatol 2014, 61, 1143–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neijenhuis, M.K.; et al. Development and Validation of a Disease-Specific Questionnaire to Assess Patient-Reported Symptoms in Polycystic Liver Disease. Hepatology 2016, 64, 151–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Aerts, R.M.M.; et al. Clinical management of polycystic liver disease. J Hepatol 2018, 68, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; et al. Clinical Correlates of Mass Effect in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0144526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Keimpema, L.; et al. Lanreotide reduces the volume of polycystic liver: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1661–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrispijn, M.; et al. The long-term outcome of patients with polycystic liver disease treated with lanreotide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012, 35, 266–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, H.; et al. Potential effect of tolvaptan on polycystic liver disease for patients with ADPKD meeting the Japanese criteria of tolvaptan use. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0264065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijnands, T.F.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Aspiration Sclerotherapy of Simple Hepatic Cysts: A Systematic Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017, 208, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; et al. Perinatal lethality with kidney and pancreas defects in mice with a targetted Pkd1 mutation. Nat Genet 1997, 17, 179–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; et al. Conditional mutation of Pkd2 causes cystogenesis and upregulates beta-catenin. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009, 20, 2556–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; et al. Pancreatic Cysts in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: Prevalence and Association with PKD2 Gene Mutations. Radiology 2016, 280, 762–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- diIorio, P.; et al. Role of cilia in normal pancreas function and in diseased states. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 2014, 102, 126–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; et al. Spleen phenotype in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin Radiol 2019, 74, 975–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijdicks, E.F., V. E. Torres, and W.I. Schievink, Chronic subdural hematoma in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2000, 35, 40–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schievink, W.I. and V.E. Torres, Spinal meningeal diverticula in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet 1997, 349, 1223–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; et al. Relationship of Seminal Megavesicles, Prostate Median Cysts, and Genotype in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019, 49, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; et al. PKD1 deficiency induces Bronchiectasis in a porcine ADPKD model. Respir Res 2022, 23, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fick, G.M. and P.A. Gabow, Hereditary and acquired cystic disease of the kidney. Kidney Int 1994, 46, 951–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheff, R.T.; et al. Diverticular disease in patients with chronic renal failure due to polycystic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 1980, 92, 202–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, C.K.; et al. Evaluation of colonic diverticular disease in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease without end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1999, 34, 863–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris-Stiff, G.; et al. Abdominal wall hernia in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Br J Surg 1997, 84, 615–7. [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen, P.K.; et al. Ovarian manifestations in women with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2002, 40, 504–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; et al. Polycystin 1 is required for the structural integrity of blood vessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 1731–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, R.D., A. M. Malek, and T. Watnick, Vascular complications in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2015, 11, 589–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulter, C.; et al. Cardiovascular, skeletal, and renal defects in mice with a targeted disruption of the Pkd1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 12174–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Q.; et al. Analysis of the polycystins in aortic vascular smooth muscle cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003, 14, 2280–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, V.E.; et al. Vascular expression of polycystin-2. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gonzalez, M.A.; et al. Pkd1 and Pkd2 are required for normal placental development. PLoS One 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauli, S.M.; et al. Endothelial cilia are fluid shear sensors that regulate calcium signaling and nitric oxide production through polycystin-1. Circulation 2008, 117, 1161–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouAlaiwi, W.A.; et al. Ciliary polycystin-2 is a mechanosensitive calcium channel involved in nitric oxide signaling cascades. Circ Res 2009, 104, 860–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif-Naeini, R.; et al. Polycystin-1 and -2 dosage regulates pressure sensing. Cell 2009, 139, 587–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelli, I.; et al. MR Brain Screening in ADPKD Patients : To Screen or not to Screen? Clin Neuroradiol 2022, 32, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchis, I.M.; et al. Presymptomatic Screening for Intracranial Aneurysms in Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019, 14, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; et al. Is Regular Screening for Intracranial Aneurysm Necessary in Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis 2017, 44, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.W.; et al. Screening for intracranial aneurysm in 355 patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Stroke 2011, 42, 204–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemczyk, M.; et al. Intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013, 34, 1556–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; et al. Intracranial Arterial Fenestration and Risk of Aneurysm: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg 2018, 115, e592–e598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascalau, R.; et al. The Geometry of the Circle of Willis Anatomical Variants as a Potential Cerebrovascular Risk Factor. Turk Neurosurg 2019, 29, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiebers, D.O.; et al. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet 2003, 362, 103–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schievink, W.I.; et al. Saccular intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 1992, 3, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenfeld, M.N.; et al. Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease and Intracranial Aneurysms: Is There an Increased Risk of Treatment? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016, 37, 290–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemori, K.; et al. PKD1-Associated Arachnoid Cysts in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2021, 30, 105943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauer, F.; et al. Growth of arachnoid cysts in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: serial imaging and clinical relevance. Clin Kidney J 2012, 5, 405–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, I.Y. and A.B. Chapman, Polycystins, ADPKD, and Cardiovascular Disease. Kidney Int Rep 2020, 5, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgut, F.; et al. Ambulatory blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Ren Fail 2007, 29, 979–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrier, R.W. , Blood pressure in early autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 976–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timio, M.; et al. The spectrum of cardiovascular abnormalities in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a 10-year follow-up in a five-generation kindred. Clin Nephrol 1992, 37, 245–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hossack, K.F.; et al. Echocardiographic findings in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 1988, 319, 907–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeferman, M.B.; et al. Echocardiographic Abnormalities in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD) Patients. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjune, S.; et al. Cardiac Manifestations in Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD): A Single-Center Study. Kidney360 2023, 4, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, K.; et al. Elevated blood pressure and risk of mitral regurgitation: A longitudinal cohort study of 5.5 million United Kingdom adults. PLoS Med 2017, 14, e1002404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumiaho, A.; et al. Mitral valve prolapse and mitral regurgitation are common in patients with polycystic kidney disease type 1. Am J Kidney Dis 2001, 38, 1208–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecder, T. and R.W. Schrier, Cardiovascular abnormalities in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2009, 5, 221–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chebib, F.T.; et al. Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Patients May Be Predisposed to Various Cardiomyopathies. Kidney Int Rep 2017, 2, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, I.Y. , Defining Cardiac Dysfunction in ADPKD. Kidney360 2023, 4, 126–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante A, Perrotta AM, Tinti F, Assanto E, Muscaritoli M, Lai S, Cianci R. Assessment of cardiovascular disease in ADPKD. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 7175. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.S. and L.D. Quarles, Role of the polycytin-primary cilia complex in bone development and mechanosensing. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010, 1192, 410–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitomer, B.; et al. Mineral bone disease in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2021, 99, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; et al. Polycystin-1 regulates skeletogenesis through stimulation of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor RUNX2-II. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 12624–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; et al. Cilia-like structures and polycystin-1 in osteoblasts/osteocytes and associated abnormalities in skeletogenesis and Runx2 expression. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 30884–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekahli, D. and J. Bacchetta, From bone abnormalities to mineral metabolism dysregulation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 2013, 28, 2089–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.C.; et al. Characterization of Primary Cilia in Osteoblasts Isolated From Patients With ADPKD and CKD. JBMR Plus 2021, 5, e10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavik, I.; et al. Patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease have elevated fibroblast growth factor 23 levels and a renal leak of phosphate. Kidney Int 2011, 79, 234–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavik, I.; et al. Soluble klotho and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012, 7, 248–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).