1. Introduction

In recent years, inclusive education has gained significant attention among educators and policymakers worldwide [

1,

2]. Moreover, the philosophy of inclusive education acknowledges the significance of granting every student access to high-quality education, irrespective of their abilities, race, gender, religion, or social status. At its core, inclusive education aims to provide equal opportunities for every student to learn and succeed in the school environment [

3,

4]. However, it is important to emphasize that inclusive education is not just about placing learners with disabilities in ordinary public schools [

5]. It includes considering various aspects of education such as assessment, access, support, resources, and leadership. Furthermore, the implementation of inclusive education continues to present challenges, particularly in terms of developing an appropriate curriculum and environment based on implementing such policy for learners with Special Educational Needs (SEN). School leaders play a crucial role in the successful implementation of inclusive education policies. Furthermore, school leaders play a key role in promoting collaboration and communication among teachers, parents, and other stakeholders to ensure the cohesive implementation of inclusive education policies in schools.

Inclusive education necessitates that schools welcome diversity and offer personalized assistance to students to help them reach their maximum potential [

6,

7]. Inclusive education is founded on the principles of equity, diversity, and personalized support. To achieve this, schools are required to adopt a student-centered approach that recognizes and caters to the diverse needs of students [

8]. Additionally, a recent study highlights the significance of comprehending and executing inclusive education policies [

9]. Policymakers must consider the viewpoints of school leaders and educators to develop effective policies.

The importance of inclusive education has been recognized by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) due to its crucial role in promoting social and economic development [

10,

11]. Many countries, including the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have pledged to support the integration of individuals with disabilities into society by implementing inclusive education policies. This global initiative aims to ensure that everyone has equal access to education. The UAE has taken steps to fulfill this commitment by implementing policies and mechanisms that promote inclusive education practices and enhance equal access [

12,

13]. In this regard, the UAE demonstrated its commitment to people with disabilities in 2010 by ratifying and adopting the UNCRPD [

13]. Therefore, the education system in the UAE expects schools to provide inclusive education, ensuring that all students have equal opportunities to participate, achieve, and be valued.

1.1. Research Context

In 2006, the UAE government launched the "School for All" program under Federal Law No. 29. This program was introduced to promote inclusive education and ensure that learners with disabilities, referred to as "students of determination," have equal access to educational opportunities in all public, private, and other educational institutions in the UAE [

14]. The UAE is dedicated to establishing an education system that is inclusive and welcomes all students, including those with disabilities, to ensure equal access to high-quality education [

13,

15]. Inclusive education is an ongoing process that involves the evaluation, planning, and implementation of actions, while monitoring and reviewing their effectiveness. This process is facilitated by forming partnerships and collective efforts to create self-sufficient, productive, and fulfilled individuals, as well as harmonious societies [

13]. The UAE has made significant progress in promoting inclusion, especially for students with SEN. This was accomplished through the implementation of legislation and policies aimed at providing equal learning opportunities for all children. In Dubai, students who have learning disorders or impairments that affect their ability to learn receive special attention under the Dubai Inclusive Education Policy Framework (DIEPF) issued by the KHDA.

The DIEPF policy aims to promote inclusivity and equity in schools by offering guidelines and strategies for establishing an inclusive learning environment that caters to the needs of all students. However, the successful implementation of the policy depends on the support of all stakeholders, including school leaders, teachers, families, therapists, and medical professionals. Therefore, the primary research question of this study is to investigate how school leaders comprehend and execute the DIEPF as well as their viewpoints on its efficacy in fostering inclusivity and equity in schools. This study aims to investigate school leaders' understanding, utilization, and perspectives regarding the DIEPF. By examining the perspectives of school leaders, this study seeks to make a valuable contribution to the continuous efforts to enhance inclusive education practices in the UAE and other regions.

In recent years, the Dubai government has enacted several laws with the aim of promoting the inclusion of individuals with disabilities in the private education sector [

16,

17]. The Dubai Law No. 2 of 2014 and Executive Council Resolution No. 2 of 2017 were enacted to safeguard the rights of individuals with disabilities and guarantee equal access to education. To comply with local laws and regulations, the DIEPF was introduced in 2017 [

13].

1.2. The Policy Framework

The framework defines inclusive education as the development of attitudes, behaviors, systems, and beliefs that promote inclusivity as a norm underlying school culture and reflected in the daily lives of the school community [

13]. The document outlines ten standards and corresponding actions that educational institutions must take to ensure the inclusion of students with disabilities. Dubai's educational institutions are expected to enhance their inclusive education programs and services by following the DIEPF standards [

13]. The standards cover various areas, including leadership, support systems, fostering a culture of inclusion, and allocating resources for inclusive education. To ensure successful implementation, the DIEPF recommends that institutions establish monitoring mechanisms to assess the quality and effectiveness of their efforts [

13]. The present study focuses on the eight standards of the DIEPF that cover areas such as leadership, support systems, fostering a culture of inclusion, and resourcing for inclusive education [

13]. The study aims to contribute to enhancing programs and services related to inclusive education in Dubai's education system.

The KHDA emphasizes the importance of serving students with SEN in inclusive learning environments [

13]. These environments are inclusive educational settings where students with diverse backgrounds and abilities learn together. By prioritizing the implementation of the DIEPF standards and serving students with disabilities in Community Learning Centers (CLEs), educational institutions in Dubai can create an inclusive environment that promotes equal access to education for all learners. Overall, the DIEPF provides a comprehensive framework for inclusive education in Dubai. By examining the perspectives and experiences of school leaders in implementing the DIEPF standards, the study will provide insights that could inform policy and decision-making surrounding inclusive education practices in Dubai's education system. To achieve this aim, the study sought to answer the following research questions: (1) how do school leaders understand DIEPF, and why do they consider it important? (2) what strategies have school leaders implemented to promote inclusive education, and how effective have these strategies proven to be?; and (3) what challenges do school leaders face in implementing DIEPF and how can these challenges be addressed to improve policy implementation?

2. Literature Review

Several quantitative studies have investigated inclusive education practices from the perspective of teachers in the UAE [

14,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, only two qualitative studies have examined school principals' perceptions of inclusive education [

15,

23]. However, to date, no study has explored school leaders' understanding, usage, and perspectives of DIEPF. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap in the existing evidence and provide guidance for future inclusive education policy implementation.

School leaders play a critical role in making decisions for students with SEN. However, their decisions may not always align with research-based practices or educational policies, leading to potential inequities in educational opportunities for these students [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. To ensure that school leaders are well-informed about research-based practices and educational policies, it is essential to investigate their understanding, utilization, and perspectives of policies such as the DIEPF [

24,

26,

29]. Creating an inclusive learning environment that supports the needs of all students is critical, and the role of school leaders is pivotal in achieving this goal [

30]. School leaders play a central role in creating a school culture that supports inclusive education by developing a shared vision, which is a critical factor in successful implementation [

31,

32]. Enlightened, creative, inspiring, and skilled school leaders are essential for successful inclusion [

33]. Transformational leaders who possess specific skills and traits, such as the ability to simplify complex concepts, motivate others, demonstrate determination, and foster innovation, are essential for promoting inclusive education [

34].

In the UAE, previous research has examined different aspects of inclusion, including inclusive practices in schools and various issues related to inclusion [

19,

21,

35]. However, the role of school principals in creating and promoting inclusive schools has been under-researched. To address this gap, researchers in the UAE conducted a study to investigate the role of school principals in promoting inclusive schools [

15]. Their findings emphasized the crucial role of principals in creating effective inclusive practices and promoting awareness of inclusive education. The study recommended implementing systematic professional development programs to increase principals' awareness of inclusive education and its implementation in schools. Similarly, a recent study explored the leadership practices associated with implementing DIEPF in schools [

23]. The study findings offered valuable insights into effective leadership practices for implementing inclusive education policies. This includes recognizing the importance of organizational and administrative dimensions, addressing practical problems faced by parents and schools, and expanding community partnerships and engagement.

Overall, it is essential to investigate school leaders' understanding, utilization, and perspectives of inclusive education policies, such as the DIEPF, to ensure their effective implementation. By examining the perspectives and experiences of school leaders in implementing DIEPF standards, the present study will contribute to the ongoing efforts to enhance inclusive education practices in Dubai's education system. Moreover, it will provide insights that could inform policies and decision-making to improve inclusive education practices within Dubai's education system.

3. Methods

A qualitative research methodology was employed, utilizing individual interviews and reflexive thematic analysis to investigate school leaders' perceptions and experiences regarding the comprehension, execution, and utilization of the Dubai Inclusive Education Policy [

36]. Our study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines for reporting. The Human Research Ethics Committee at the university of the first author approved this study.

School leaders who held recognized leadership positions, such as principal or assistant principal, and were responsible for managing and administering the DIEPF at their respective private inclusive or mainstream schools in Dubai were eligible to participate in this study. To take part in this study, the participant schools had to enroll primary-aged students with disabilities. In compliance with the KHDA, the authors identified a pool of eligible schools (more than what was required for the final sample) to minimize selection bias. A total of 15 private schools in Dubai that promote inclusivity were invited to participate in the study. Eleven schools agreed to participate, but one school declined due to unavailability of participants during the study. Interviews lasting between 60 and 90 minutes were conducted individually with seven principals and three assistant principals from ten private schools. Of the ten interviewees, seven were female, and three were male. Three of the interviewees held a Ph.D., while four had a master’s degree, and the remaining three had a bachelor's degree. All interviewees had between 11 and 15 years of experience and had been in their current roles for a period ranging from 11 months to 13 years. They represented private schools with American curriculum (n=5), British curriculum (n=3), and International Baccalaureate (IB) curriculum (n=2). These schools enrolled between 550 to 1000 students.

The first author contacted the potential study participants via email, provided them with study details in the participant information letter and consent form, and confirmed that the research had been approved by their university affiliation. Participants were recruited between September and November 2022 using non-probabilistic purposive sampling to select individuals with relevant experience, to obtain rich and in-depth information [

37]. Interested individuals were invited to participate in the study by contacting the researchers directly. Semi-structured interviews were utilized to gather comprehensive data on participants' relevant experiences and perceptions. These interviews were conducted online using Microsoft Teams and were facilitated by a second researcher under the supervision of an experienced qualitative researcher. Prior to each interview, participants were given both written and verbal information about their right to withdraw from the study. They were also asked to provide their consent to participate. Before the interviews, participants were given the opportunity to provide demographic information about their school and experience through self-report surveys.

To ensure consistency and establish a connection with the participants, we created an interview guide that drew from current literature. The guide was refined after pilot testing and receiving feedback from four experienced master’s degree students enrolled in an Education Leadership program. Their input helped to enhance the clarity of the questions. The final protocol covered several topics, including the participants' interpretation and understanding of the policy, their adherence to policy standards, the practices employed during policy implementation, and the enablers and barriers to successful implementation. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed word-for-word, and de-identified to ensure the confidentiality of the participants.

Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data and generate central organizational themes [

36]. This approach is flexible and reflects the values of qualitative designs, incorporating researcher subjectivity, recursive coding processes, and thoughtful engagement with data [

36]. The first and second researchers familiarized themselves with the dataset by thoroughly reading and analyzing the interview transcripts. Researchers generated codes independently using an inductive approach, where coding and theme development were directed by the content of the data [

36]. Similar codes were grouped together based on their shared meanings to form potential themes. Thematic mapping has been used to visually explore candidate themes, consider connections, and refine themes [

38]. During the final analysis stage, the researchers developed the central organizing themes that were ultimately used. This was a recursive process, involving iterative movements between the steps to ensure that all coded data for each theme were related to a central organizing concept that captured the essence of the dataset [

36].

To enhance credibility and foster a nuanced interpretation of the data, two researchers were involved in the analysis process rather than simply seeking consensus [

36]. An audit trail, field notes, and reflective journals were utilized to ensure reliable and transparent decision-making throughout the analysis process. To ensure confirmability, member checking was conducted by sending the participants' transcripts via email and requesting feedback [

39]. This approach allowed participants to review their transcripts and offer insights on the analysis, thereby enhancing the credibility of the findings.

3. Results

Following a careful review of the study findings, three central organizing themes emerged, namely: (1) Understanding the importance of the policy; (2) Strategies implemented to promote inclusive education; (3) Challenges faced in implementing the policy.

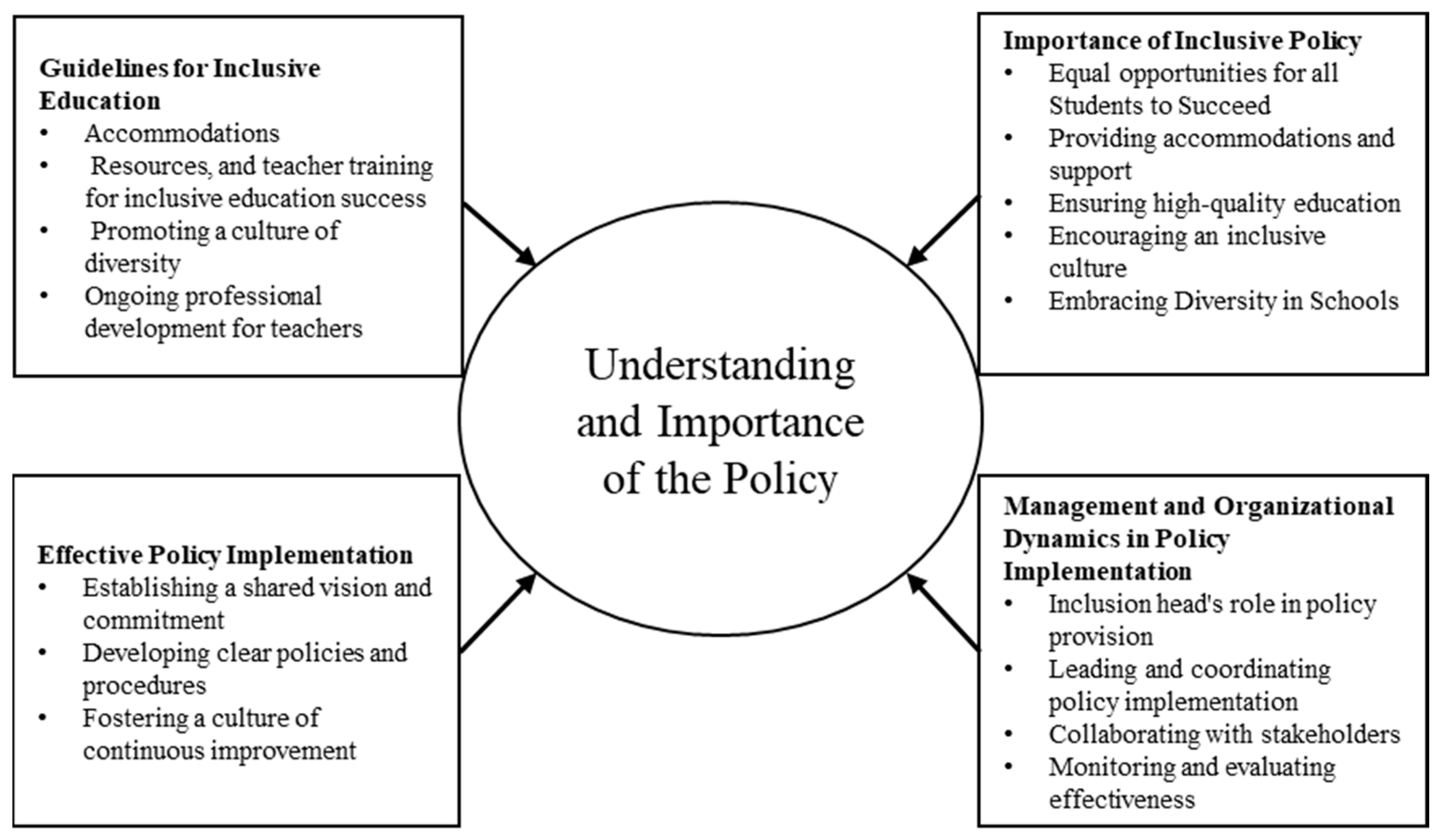

3.1. Theme 1: Understanding the Importance of the Policy

The DIEPF aims to ensure that all schools are inclusive and provides guidelines and standards for improving inclusive education provision [

13,

40]. Understanding the participants' knowledge and comprehension of the procedures and standards required for enhancing inclusive education provision is crucial to comprehend how the policy was executed (

Figure 1).

The study participants shared their understanding and perspective on the significance of the DIEPF. According to the interviewees, the policy was viewed as a positive measure towards establishing an inclusive education system that accommodated the requirements of all students, including those with SEN. The participants agreed that the policy provided guidelines and strategies for creating an inclusive learning environment. This includes providing appropriate accommodations, resources, and teacher training, which are crucial to the success of inclusive education. One interviewee reported:

“Our school follows a continuous cycle of identifying, assessing, planning, teaching, and making provisions that take into account the individual needs of students”.

All participants believed in the importance of the policy and its potential to enhance the educational outcomes for all students. They emphasized the importance of schools embracing diversity and ensuring that all students are provided with equal opportunities to learn and succeed by implementing inclusive processes. One interviewee reported:

“We follow specific steps to ensure inclusion, including the following: 1. Identification 2. Referral 3. Observation 4. "Team Meeting 5, Support 6, Review”.

This theme emphasizes the significance of management and organizational dynamics in the successful implementation of policies. The participants highlighted the crucial role of inclusion coordinators in the school's policy provision. The coordinator works with the principal and heads of the school to determine the strategic development of the policy and oversees the day-to-day implementation of the school's special education needs policy. One participant indicated that he or she frequently reviewed the DIEPF in consultation with the senior management and leadership team. Additionally, school practices were characterized by promoting a culture of diversity and inclusion among both students and staff. The schools offered a range of resources such as training programs, technological tools, and materials to enhance and support diversity and inclusion initiatives throughout their campuses. Participants emphasized the importance of leadership, planning, organization, and control in effectively implementing the policy to ensure that every student is given equal opportunities to succeed in both school and life.

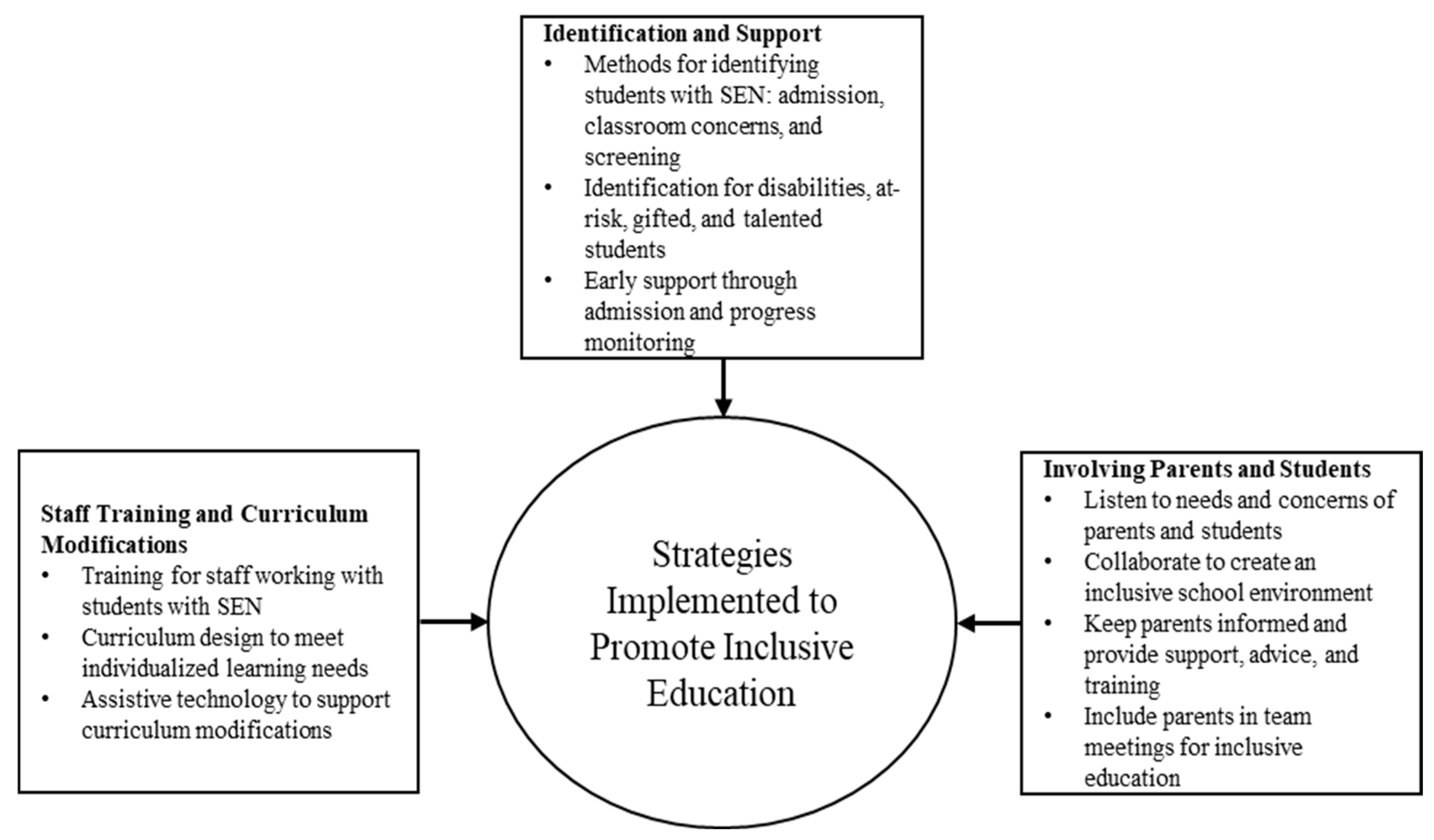

3.2. Theme 2: Strategies Implemented to Promote Inclusive Education

The participants discussed various strategies they had implemented to promote inclusive education in their schools. These strategies include identification and referral, staff training, and curriculum modifications. Participants also emphasized the importance of involving parents and students in the process of creating an inclusive school environment (

Figure 2).

The participants emphasized the significance of identifying students with SEN to promote inclusive education and provide the necessary support. They unanimously agreed on three primary methods for identifying students with SEN: (1) during admission through parent referral or identification by a teacher, (2) identification in class based on academic or behavioral concerns, and (3) identification through screening, such as the Cognitive Abilities Test 4th edition (CAT4), Group Learning Assessment (GLA), and Screening Checklists.

According to one participant:

“Our school uses a learning support flowchart for identification purposes”.

In other words, support for students begins early in the admission process, with monitoring of their progress in the classroom, and assistance provided through academic and student support networks. Additionally, it became clear from the participants that identification is not only necessary for students with disabilities or those at risk, but also for gifted and talented students. One participant emphasized the significance of identifying students with disabilities and those who are gifted and talented, as they require comprehensive support in the classroom. The participants confirmed that when teachers notice concerns regarding a student's academic performance or behavior, they provide differentiated activities and monitor the situation for two to three weeks, depending on the child's needs. If this concern persists, the teacher may consult with a special education professional to confirm or clarify the issue before approaching the parents. If the problem is severe, the teacher will promptly arrange a meeting with the parents. The teacher will fill out a referral form, and the Inclusive Education Department will obtain parental consent to work with their child by having them sign a consent form. Once a referral is submitted, the special educator observes the student to determine the appropriate intervention.

The participants emphasized the significance of offering training to all personnel who work with students with SEN. This training would enable them to effectively support the unique requirements of students with disabilities. One participant stated:

“The school provides staff training and encourages teachers to attend conferences. I remember that last year, we had training for our staff on how to differentiate instruction and create a more inclusive classroom”.

Participants adopted curriculum access and modification as inclusive educational practices and strategies. Students with SEN are provided with support to ensure they have full access to the curriculum and equal learning experience. This is achieved through high-quality curriculum design that meets the individualized learning needs of each student. One participant added:

“I believe that we have invested in assistive technology, such as text-to-speech software and magnification, to support curriculum modifications for students with SEN”.

Participants emphasized the importance of involving parents and students in the process of creating an inclusive school environment. They emphasized the importance of actively listening to the needs and concerns of both parents and students and working collaboratively with them to establish an inclusive school environment. Participants suggested that parents should be kept fully informed about their child's progress and attainment, as well as when special educational provision is required for a student. They also recommended providing support, advice, and training for parents, and including them in team meetings for Individualized Education (IE). In this regard, one participant stated:

“I believe that involving parents is key to the success of inclusiveness..." Continuous parental engagement through workshops and meetings is also important”.

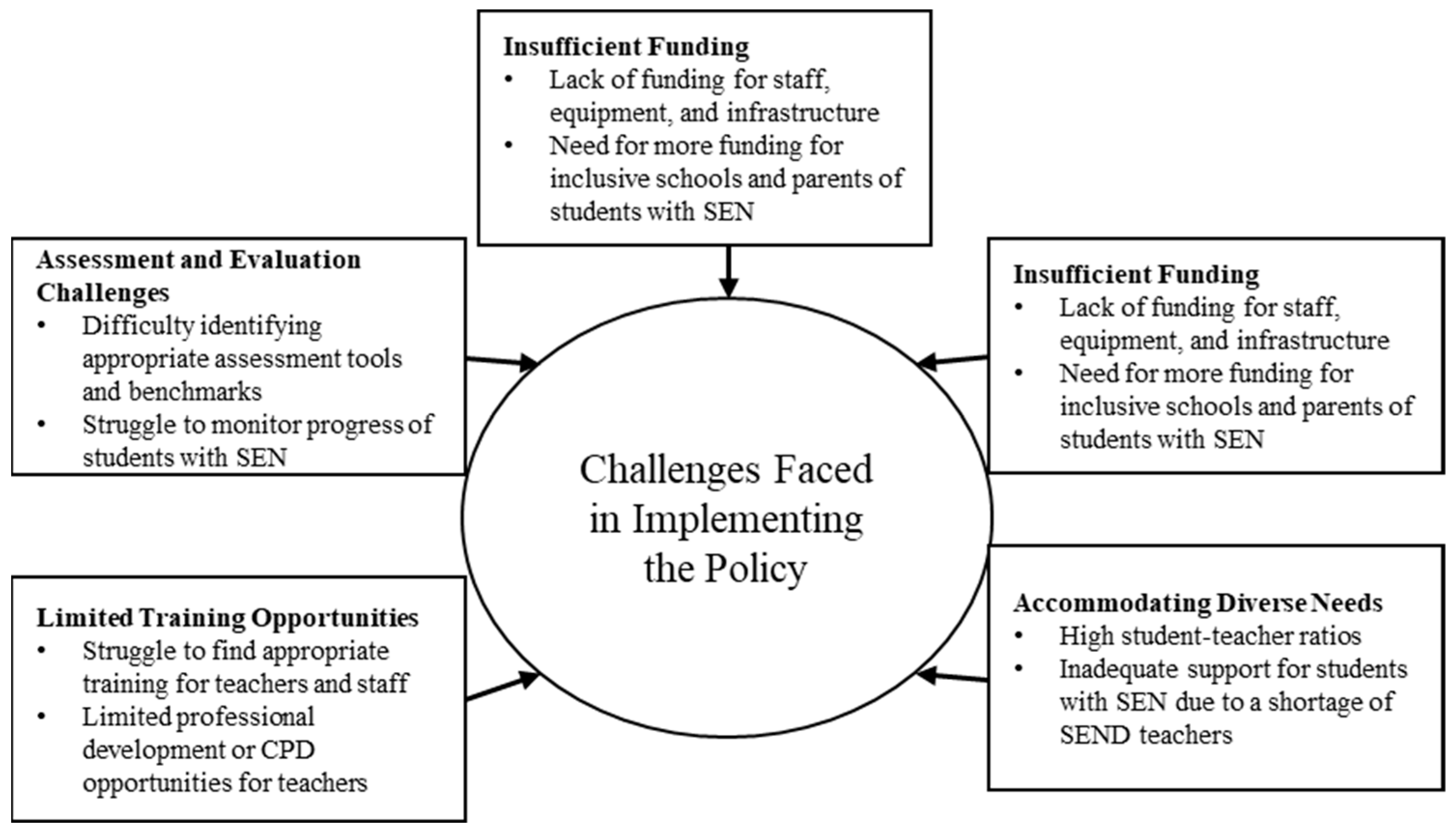

3.3. Theme 3: Challenges Faced in Implementing the Policy

Participants identified various challenges faced in implementing DIEPF in their schools. These challenges include insufficient funding, high student-teacher ratios, perceptions of inclusive education, assessment and evaluation, and a lack of inclusive social networks (

Figure 3).

One significant challenge highlighted by the participants was the lack of adequate funding for inclusive education. Private schools may face challenges in allocating budgets and resources to provide inclusive education due to the high costs associated with hiring specialized staff, purchasing equipment, and modifying infrastructure to meet the needs of students with SEN. Participants emphasized the need for increased funding for inclusive schools and support for parents of students with SEN. One interviewee stated:

“The biggest obstacle to implementing inclusive education is insufficient funding.... We require more funding for inclusive schools and to support parents of students with SEN”.

Another challenge identified by the participants was the difficulty that teachers faced in accommodating the diverse needs of their students in the classroom. Due to the large class sizes, teachers are unable to offer individualized support to students with SEN.

Furthermore, there is an insufficient number of teachers trained in special education to meet the needs of all students with disabilities, making it difficult to provide the necessary support. One participant stated:

“In every classroom, there are approximately 30 diverse students, making it difficult for teachers to provide one-on-one support to students with SEN while attending to the needs of other students”.

Participants also reported limited training opportunities as a challenge to implementing the policy. Private schools may face challenges in providing adequate training opportunities for their teachers and staff to support inclusive education, which could lead to teachers feeling ill-equipped to meet the needs of students with SEN. According to one participant:

“a lack of professional development or insufficient continuous professional development (CPD) may leave teachers feeling unprepared to cater to the needs of students with SEN”.

In terms of assessment and evaluation, the participants highlighted that teachers encounter difficulties when it comes to assessing and evaluating the progress of students with SEN. Teachers may find it challenging to select suitable assessment tools or benchmarks for progress, which can make it hard to track the progress of students with SEN. One participant elaborated that “teachers in the mentioned school often face challenges in administering exams and tests, particularly when they have students with SEN”.

Figure 3.

Challenges in implementing Dubai's inclusive education policy.

Figure 3.

Challenges in implementing Dubai's inclusive education policy.

The perception of inclusive education is often viewed as a challenge. This could lead to resistance towards implementing inclusive education policies in schools. Finally, the participants emphasized the significance of inclusive social networks and community engagement. They stated that schools should serve as community resources, and that there should be more inclusive social networks to support students with disabilities. The role of schools in fostering an inclusive community may not be immediately clear, and it is important to involve the community in policy decisions to achieve this goal. One of the interviewees stated:

“The role that schools play in building an inclusive community is not apparent. We need more inclusive social networks where schools serve as community resources and community involvement is prioritized from a policy perspective”.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to provide valuable insights into the perceptions of school leaders regarding the DIEPF, including their comprehension, implementation, and perspectives. This study's qualitative approach is the first to explore the perspectives of school leaders in private schools in Dubai regarding the implementation of inclusive education policies. This brings forward more depth and richness for the existing literature on inclusive education. The data analysis of the study was rigorous, providing an essential context for current quantitative research on inclusive education. The KHDA and Ministry of Education (MOE) of UAE require schools to implement inclusive education policies and practices that support students with diverse learning needs. Our study collected data from private schools in Dubai, providing insights into the implementation and impact of policies as well as the challenges and opportunities that arise from them. As Dubai is experiencing rapid growth and increasing diversity, studying inclusive education policies may have broader implications for promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in education.

4.1. Effective Policy Implementation: A Key to Empower Inclusion in Schools

Our study's results indicate that the participants have a strong understanding of the DIEPF and recognize its significance in promoting an inclusive education system. They perceive the policy as a positive step forward and acknowledge the provision of crucial guidelines and strategies for promoting inclusive education. Moreover, school leaders demonstrate a commitment to embracing diversity and ensuring equal opportunities for all students. The participants' recognition and understanding of an inclusive education policy aligns with previous research on inclusive education policies. This research highlights the critical role of policy implementation in establishing inclusive education systems [

41,

42]. Furthermore, previous studies have found that school leaders play a crucial role in promoting inclusive education practices [

43,

44,

45].

In line with the findings of our study, previous research has emphasized the significance of inclusive education policies in offering the necessary guidelines and strategies for inclusive education practices [

42,

46,

47]. Such policies can serve as a framework for schools to cultivate inclusive practices and establish more inclusive learning environments. Furthermore, research has shown that school leaders and educators who are dedicated to promoting diversity and ensuring equal opportunities for all students can have a significant impact on fostering inclusive education practices [

43,

48].

This study found evidence of effective strategies implemented by school leaders to promote inclusive education in private schools in Dubai. The strategies identified by the study include identifying and referring to students with SEN, providing staff training, modifying the curriculum, and involving parents and students in the process. These approaches demonstrate a comprehensive and holistic strategy to establish an inclusive school environment. The finding that the participants implemented effective strategies to promote inclusive education is consistent with previous research that emphasizes the significance of such strategies [

49,

50].

For instance, identifying and referring students with SEN is a crucial first step in providing the necessary support to these students [

48]. Providing training for staff in inclusive education practices is essential for enhancing educators' skills and abilities [

49]. Modifying the curriculum to meet the needs of diverse learners is a crucial strategy for promoting inclusive education [

42]. Involving parents and students in the process of developing and implementing inclusive education policies and practices can cultivate a positive school culture that esteems and honors all students. The findings highlight an urgent, ongoing, and unmet need for professional development and continuous training related to the policy itself, curriculum modifications, and the impact of disabilities on families. This finding is consistent with previous research that highlights the necessity of a cultural shift within schools and practical training to improve educators' skills and abilities [

49,

50].

4.2. Complexities of Inclusion Policy Implementation

Our study found that participants faced challenges in implementing inclusive education policies in private schools in Dubai. The challenges identified by the participants included insufficient funding, high student-teacher ratios, limited availability of specialized staff, inadequate training opportunities for teachers, difficulties in assessing and evaluating students with SEN, and misconceptions held by parents about inclusive education as shared by the study participants. The finding that insufficient funding is a significant obstacle to implementing inclusive education policies is consistent with prior research in this area. For instance, a study found that inadequate financial resources are a barrier to including more students in augmentative and alternative communication with multiple disabilities in inclusive education [

51]. Lack of funding can pose a significant challenge for schools to offer the essential resources and support required for inclusive education, including assistive technologies, specialized personnel, and teacher training. High student-teacher ratios and a lack of specialized staff further hinder the ability to provide the personalized support necessary to meet the diverse needs of students.

The findings suggest that challenges in implementing inclusive education policies are compounded by limited training opportunities for teachers and difficulties in assessing and evaluating students with SEN. Teacher training is essential for improving the skills and abilities of educators in promoting inclusive education practices [

49,

52]. The challenges of assessing and evaluating students with SEN can make it difficult to determine the appropriate support and accommodation required to meet their needs. Without proper assessment and evaluation, students may not receive the necessary support to reach their full academic and social potential, which can have a lasting impact on their future outcomes.

Furthermore, the study found that some parents held misconceptions about inclusive education, which may have created resistance and barriers to the implementation of the policy. Addressing misconceptions and educating parents about the benefits of inclusive education may require additional efforts from school leaders to promote understanding and support for inclusive education practices. This study's finding that some parents hold misconceptions about inclusive education is not uncommon. Misconceptions about inclusive education can create resistance and barriers to the implementation of the policy. For example, some parents may have concerns that inclusive education could have a negative impact on their children's academic progress. Hence, some may hold the belief that inclusive education is not appropriate for students with SEN, and instead, may advocate for specialized schools or programs [

43].

5. Conclusions

Qualitative studies aim to explore and understand experiences and areas of interest, rather than generalizing results. This study followed a qualitative approach and aimed to explore school leaders' perceptions of the DIEPF, including their understanding, utilization, and perspectives. However, the study's reliance on self-reported data from participants may be subject to biases, such as social desirability bias or memory recall bias. Participants may provide responses that they believe align with societal expectations, or they may have difficulty accurately recalling specific details about their practices and experiences. It is important to acknowledge that this study has limitations that should be considered when applying the findings on a national or international level. Differences in policy, legislation, and school settings may significantly impact the transferability of the results. Firstly, the study solely concentrated on the perceptions of school leaders and did not involve teachers or inclusion teams at schools. These individuals are frequently responsible for overseeing and executing inclusive education practices for all students. Secondly, although the study included participants with diverse experiences and school demographics, it was an exploratory qualitative study with a relatively small sample size. Therefore, it cannot be guaranteed that data saturation was achieved, and it is possible that a larger sample size could have provided additional perspectives.

This study highlighted the positive perceptions of school leaders towards the DIEPF. It emphasized the importance of effective strategies, such as identifying and referring students with SEN, providing staff training, modifying the curriculum, and involving parents and students, in achieving inclusive education. However, the study also identified challenges that need to be addressed. These include insufficient funding, high student-teacher ratios, limited availability of specialized staff, and inadequate training opportunities for teachers. Considering these implications, policymakers, schools, and stakeholders can collaborate to establish a more comprehensive and inclusive education system in Dubai and other regions.

Recommendations for future research include expanding the sample size to include more private schools and government institutions, with a specific focus on comparing policy implementation across all types of school settings. Conducting a cross-sectional survey to assess the attitudes and understanding of teachers, inclusion staff, parents, and students would further contribute to these findings and provide valuable insights for the future implementation of the policy. To promote the development of user-friendly policies and procedures and ensure consistency across all emirates in the UAE, we recommend school leaders sharing experiences and best practices in inclusive education among educational institutions. It is important to note that each emirate has its own policies, which should be taken into consideration.

This study has implications for policymakers, schools, and stakeholders involved in inclusive education. School leaders have expressed positive perceptions of the DIEPF, indicating that it should be continued and further strengthened. However, there are several challenges that need to be addressed, including insufficient funding, high student-teacher ratios, limited availability of specialized staff, and limited training opportunities for teachers. Schools should prioritize effective strategies, such as identifying and referring students with SEN, modifying the curriculum, and involving parents and students in the process. All stakeholders should receive education on the benefits of inclusive education to address any misconceptions and promote support for inclusive practices.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed to this work. Conceptualization, A.M., M. Alhosani, M. Al-Rashaida; methodology, A.M., M. Alhosani, M. Al-Rashaida; formal analysis, A.M., M. Alhosani, M. Al-Rashaida; investigation, A.M., M. Al-Rashaida; writing—original draft preparation, A.M., M. Al-Rashaida; writing—review and editing, A.M., M. Alhosani, M. Al-Rashaida. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs at Abu Dhabi University, grant number 19300610.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Abu Dhabi University (protocol code CAS-22-08-00024, August 31, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. Due to privacy and ethical considerations, the data cannot be publicly shared. Researchers interested in accessing the data may contact the corresponding author Mohammad Al-Rashaida at: moh.alrashaida@uaeu.ac.ae to discuss the possibility of obtaining access to the data, subject to compliance with relevant data protection and confidentiality protocols.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to all the participants who took part in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mitchell, D. R. (2017). Diversities in education: Effective ways to reach all learners. Routledge.

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (2003). Overcoming exclusion through inclusive approaches in education: A challenge and a vision. UNESCO.

- Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2002). Index for inclusion: developing learning and participation in schools. Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education (CSIE).

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (1994). Salamanca statement and framework for action on special education needs. UNESCO. Retrieved from http://www.unesco. org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF. /.

- Engelbrecht, P., & Louw, H. (2021). Teachers' experiences in the implementation of the life skills CAPS for learners with severe intellectual disability. https://scite.ai/reports/10.17159/2221-4070/2021/v10i2a7.

- Khochen-Bagshaw, M. Drivers of ‘inclusive secondary schools’ selection: lessons from Lebanon. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2020, 27, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenoweth, L.; Stehlik, D. Implications of social capital for the inclusion of people with disabilities and families in community life. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2004, 8, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlin, C.; Kawai, N.; Higuchi, S. Educational reform in Japan towards inclusion: Are we training teachers for success? International Journal of Inclusive Education 2015, 19, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, G.; Brown, C.; Joosten, A.; Hayward, B. Exploring the implementation of the restraint and seclusion school policy with students with disability in Australian schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.J.; Snoddon, K.; De Meulder, M.; Underwood, K. Intersectional inclusion for deaf learners: moving beyond General Comment no. 4 on Article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2020, 24, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, A. (2017). A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education. UNESCO IBE.

- Gaad, E. (2019). Educating learners with special needs and disabilities in the UAE: Reform and innovation education in the United Arab Emirates: Innovation and Transformation, 147-159.

- Knowledge and Human Development Authority (2017). Dubai Inclusive Education Policy Framework. KHDA: United Arab Emirates.

- Hussain, A. S. (2017). UAE preschool teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion education by specialty and cultural identity. (Doctoral dissertation, Walden University, Washington).

- Khaleel, N.; Alhosani, M.; Duyar, I. The role of school principals in promoting inclusive schools: a teachers’ perspective. Frontiers in Education 2021, 6, 603241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubai Executive Council. (2017). Executive Council Resolution No. 2 of 2017 on the Regulation of Private Schools in Dubai. Retrieved from https://www.dubaifaqs.com/dubai-executive-council-resolution-no-2-2017.php. /.

- Dubai Government. (2014). Dubai Law No. 2 of 2014. Retrieved from https://www.dubaifaqs.com/dubai-law-no-2-2014.php. /.

- Alghazo, E.; Gaad, E. ‘General education teachers in the UAE and their acceptance of the inclusion of students with disabilities’. British Journal of Special Education 2004, 31, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anati, N. The pros and cons of inclusive education from the perceptions of teachers in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Research Studies in Education 2013, 2, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukmak, S.J. Regular classroom teachers’ attitudes towards including students with disabilities in the regular classroom in the United Arab Emirates. The Journal of Human Resource and Adult Learning 2013, 9, 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gaad, E.; Almotairi, M. Inclusion of student with special needs within higher education in UAE: Issues and challenges. Journal of International Education Research 2013, 9, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaad, E.; Khan, L. Primary mainstream teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion of students with special educational needs in the private sector: a perspective from Dubai. International Journal of Special Education 2007, 22, 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Massouti, A.; Shaya, N.; Abukhait, R. Revisiting leadership in schools: Investigating the adoption of the Dubai inclusive education policy framework. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buli-Holmberg, J.; Sigstad HM, H.; Morken, I.; Hjörne, E. From the idea of inclusion into practice in the Nordic countries: A qualitative literature review. European Journal of Special Needs Education 2023, 38, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D. L. Too much or not enough? An examination of special education provision and school district leaders’ perceptions of current needs and common approaches. British journal of special education 2016, 43, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnukainen, M. Inclusion, integration, or what? A comparative study of the school principals’ perceptions of inclusive and special education in Finland and in Alberta, Canada. Disability & Society 2015, 30, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Lin, Y.; Bao, T.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Qian, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhu, D. Inclusive education of elementary students with autism spectrum disorders in Shanghai, China: From the teachers' perspective. BioScience Trends 2022, 16, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazey, B.L.; Cole, H.A. The role of special education training in the development of socially just leaders: Building an equity consciousness in educational leadership programs. Educational administration quarterly 2013, 49, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sider, S.; Maich, K.; Morvan, J. School principals and students with special education needs: Leading inclusive schools. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l'éducation 2017, 40, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- DeMatthews, D.E.; Serafini, A.; Watson, T.N. Leading inclusive schools: Principal perceptions, practices, and challenges to meaningful change. Educational Administration Quarterly 2021, 57, 3–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumbera, M.J.; Pazey, B.L.; Lashley, C. How building principals made sense of free and appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment. Leadership and Policy in Schools 2014, 13, 297–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero Hughes, M.; Passmore, A.; Maggin, D.M.; Kumm, S. Teacher leadership: exploring the perceptions of special educators. International Journal of Leadership in Education 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Prater, M.A.; Jackson, A.; Marchant, M. Educators’ perceptions of collaborative planning processes for students with disabilities. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth 2009, 54, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkowski, S.; Ulrich, M.; Müller, B. Co-teaching as a resource for inclusive classes: teachers’ perspectives on conditions for successful collaboration. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2023, 27, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alborno. N.E. The “yes … but” dilemma: implementing inclusive education in Emirati primary schools. British Journal of Special Education 2017, 44, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE.

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrien, B. Evidence-based care: enhancing the rigour of a qualitative study. British journal of nursing (Mark Allen Publishing) 2008, 17, 1286–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowledge and Human Development Authority (2019). Implementing Inclusive Education: A Guide for Schools. KHDA.

- Kefallinou, A.; Symeonidou, S.; Meijer, C.J. Understanding the value of inclusive education and its implementation: A review of the literature. Prospects 2020, 49, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L. , & Black-Hawkins, K. Exploring inclusive pedagogy. British educational research journal 2011, 37, 813–828. [Google Scholar]

- Avramidis, E.; Toulia, A.; Tsihouridis, C.; Strogilos, V. Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion and their self-efficacy for inclusive practices as predictors of willingness to implement peer tutoring. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 2019, 19, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, C. Principals play many parts: a review of the research on school principals as special education leaders 2001–2011. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2015, 19, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, J.; Lenkeit, J.; Hartmann, A.; Ehlert, A.; Knigge, M.; Spörer, N. The effect of school leadership on implementing inclusive education: How transformational and instructional leadership practices affect individualized education planning. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2022, 26, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S.; Sharma, U.; Furlonger, B. The inclusive practices of classroom teachers: a scoping review and thematic analysis. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2021, 25, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, R. Discourses of inclusion and exclusion: Drawing wider margins. Power and education 2014, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Sandill, A. Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organizational cultures and leadership. International journal of inclusive education 2010, 14, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, D.J.; Mattingly, M.J.; Connelly, V.J. The restraint and seclusion of students with a disability: Examining trends in US school districts and their policy implications. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 2017, 28, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trader, B.; Stonemeier, J.; Berg, T.; Knowles, C.; Massar, M.; Monzalve, M.; Pinkelman, S.; Nese, R.; Ruppert, T.; Horner, R. Promoting inclusion through evidence-based alternatives to restraint and seclusion. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 2017, 42, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldabas, R. Barriers and facilitators of using augmentative and alternative communication with students with multiple disabilities in inclusive education: Special education teachers’ perspectives. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2021, 25, 1010–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rashaida, M.; Amayra, I.; López-Paz, J.F.; Martinez, O.; Lázaro, E.; Berrocoso, S.; García, M.; Pérez, M.; Rodríguez, A.A.; Luna, P.M.; et al. Studying the Effects of Mobile Devices on Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Systematic Literature Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2022, 9, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).