1. Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI), fecal incontinence (FI), and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) are all common and disabling conditions that have a significant impact on one’s quality of life (QOL) [

1]. There are many urogenital signs that affect 23–49% of females, with a predicted estimated that there will be 43.8 million cases by 2050 in undeveloped and developing countries. This will result in negative emotional and physical effects on their aspect of life [

2].

According to previous research, almost 25% of all women in the United States of America suffer from Pelvic Floor Disorders (PFD), and 20% of these women will need UI or POP surgery at some point in their lives [

3].

As a definition, the backward descent of the female reproductive organs (vagina, uterus, bladder, and/or rectum) through or into the vagina is referred to as POP. POP affects 20 to 50 percent of women worldwide, and the risk increases with age, parity, and heavy lifting [

4].

In addition to the underlying anatomical conditions, it is essential to consider a female’s general pelvic performance [

3]. A standardized questionnaire plays a key role in the identification of a condition’s signs and helps clinicians to accurately determine and characterize any symptom [

5]. To accomplish this, in 2003, condition specific QOL instruments were created and published in Italy by Digesu et al. [

6]. It was then translated into several languages, including English, German, Dutch, Slovakian, Persian, Portuguese, Thai, Japanese, Amharic, and Turkish [

4,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The prolapse quality-of-life questionnaire (P-QoL) is one of the few validated and reliable condition-specific questionnaires designed to measure the impact of urogenital prolapse on patients’ QOL. The questionnaire addresses overall health, prolapse effect, role restrictions, physical limits, social limitations, relationships, emotional difficulties, sleep/energy abnormalities, and prolapse severity [

14].

Using instrumental tools in a patient’s native language in the assessment process provides a clear identification of the condition, reflecting all life aspects [

15]. A large majority of pelvic floor problem surveys were first written in English. However, because many of the symptoms may be experienced and reported differently by women from different cultures, an effort should be made to establish culturally relevant questionnaires. As a result, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of relevant surveys in Arabic among non-English-speaking communities is necessary [

16].

Elbiss et al. conducted a study reporting the prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), in which they confirmed that the UAE, as in all other Arab countries, have a high level of parity. They also concluded that POP symptoms were common in Emirati women. Independent risk variables were a history of chronic constipation, chest illness, education level, work type, birth weight, and BMI. More healthcare efforts were needed to educate the public about these risk factors [

17]. Therefore, establishing an Arabic translated version of the P-QoL would be beneficial.

Cultural adaptation and validation in questionnaire entail a first step of cross-cultural adaptation, followed by psychometric property validation. This approach, in addition to being less expensive than developing new questionnaires, helps researchers to conduct cross-national comparisons. The aim of cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires is to ensure that there is semantic, logical, idiomatic, and material equivalence with the original source, which necessitates a systemic approach [

18]. Meanwhile, the aim of validation is to prove the reliability and validity of the Arabic version of the P-QoL as a measurement scale.

To date, no valid Arabic version of the P-QoL has been developed in the UAE or any other Middle Eastern country, despite the necessity. Indeed, in the future, the questionnaire may be implemented in outpatient facilities to aid in identifying the problems that the patients have.

2. Materials and Methods

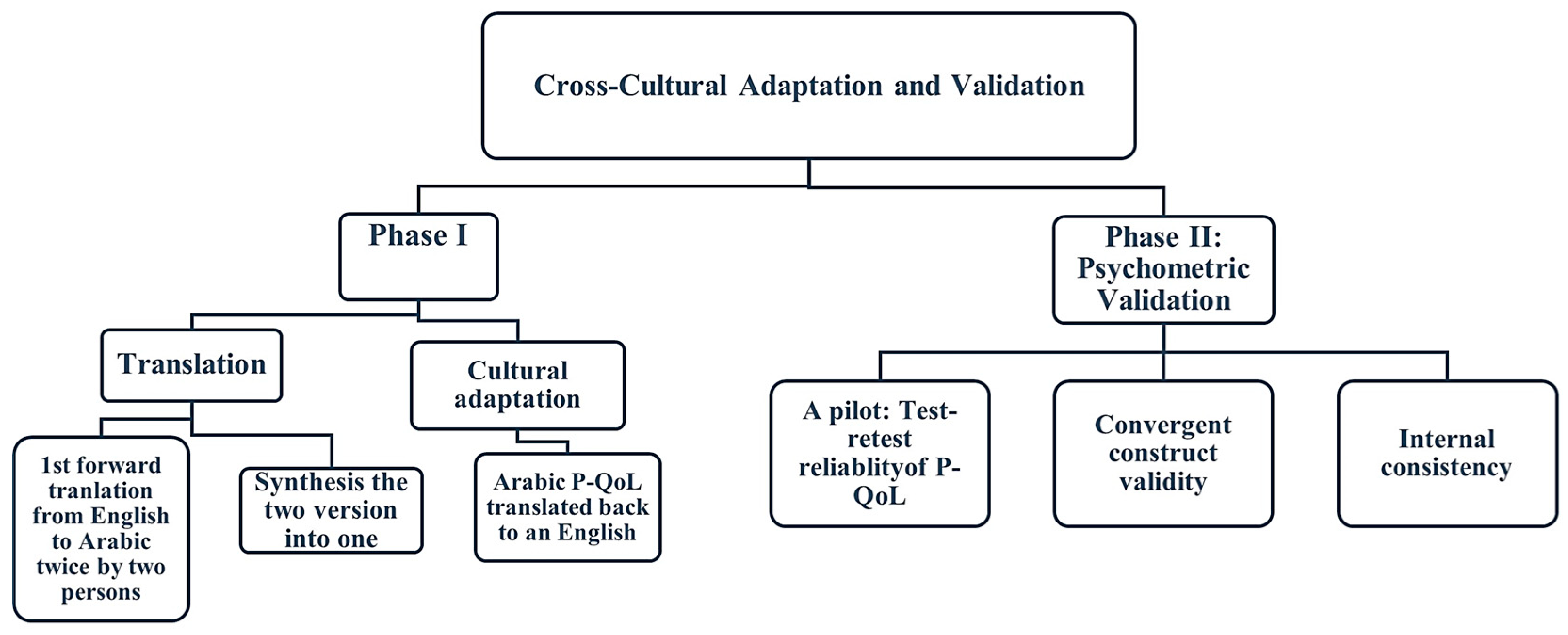

This study had gone through two phases. During phase I, the P-QoL was translated and culturally adapted from English into Arabic. The Arabic version was psychometrically validated during phase II. This study was approved by University of Sharjah Research Ethics Committee (REC-21-06-23-02-S) and Ministry of Health and Prevention Research Ethics Committee (MOHAP/DXB-REC/ SSN/No. 94/ 2021), UAE. The total procedure to complete translation and validation is shown in

Figure 1.

2.1. Participants

This study was delimited to Emirati females, aged between 18–65, diagnosed with POP with or without symptoms, and willing to participate the study voluntarily. Women were classified as symptomatic if they had signs of uterovaginal prolapse (such as a genital bulge or a feeling of heaviness in the vagina) and as asymptomatic if they did not have any symptoms. Women in the asymptomatic population had routine check-ups, including pelvic ultrasound scans, to check their complaints in regard to menstrual pain, heavy cycles, endometriosis, amenorrhea, the need for abortion, breast cancer, contraception, or, and other non-prolapse disorders [

19]. Study group classification into symptomatic and asymptomatic was done after gynecological screen testing.

Exclusion criteria included pregnant women, recent surgery or childbirth patients, women with acute symptoms of urinary tract infection, women unable to read, and non-Arabic speakers.

During the period between March 2022 and July 2022, recruitment was done across Emirate’s Health Services (EHS) Hospital’s Gynecology Outpatient Clinics following the ethical approval received from Research Ethics Committee of University of Sharjah and Research Ethics Committee in Ministry of Health and Prevention, UAE.

2.2. Prolapse Quality of Life Questionnaire (Study Tool)

Nine sections, with a total of 16 questions, make up the unique, multidimensional P-QoL. The P-QoL was initially created to assess how women’s QOL was affected by POP. The first question focuses on the woman’s overall health. The second question evaluates the impact of POP on the woman’s quality of life. The third and fourth questions assess the limitations on daily activities that the urogenital prolapse may impose. The next four questions evaluate any potential physical and social constraints brought on by POP. The ninth, tenth, and eleventh questions examine how the woman’s personal relationships have been affected by her uterovaginal prolapse. The effects of the urogenital prolapse on the women’s emotions are assessed in questions 12 through 14.

Questions 15 and 16 evaluate symptom severity and the impacts on sleep and energy [

20].

2.3. Phase I: Translation and Cultural Adaptation

The original English form was forward translated by two native speaking Arabic translators, who were also fluent in English. They translated the document from English into Arabic. The two translators (one with a medical background, the second was an official translator with a nonmedical background) worked separately to translate the English version of the P-QoL into Arabic. In the second step, the translators synthesized the two Arabic translations into a single translation. A third translator conducted a backward translation (into English) on the Arabic version produced in the second phase. The original text and the back-translated version were then carefully evaluated to identify and address any potential contradictions. The third translator concurred that the original material had been preserved without any ambiguity. No modifications were included in the translated version, and the Arabic translation initially produced in the second phase remained unchanged.

2.4. Phase II: Psychometric Validation

Prior to the study, a pilot was conducted on randomly chosen 30 participants that have completed the Arabic P-QoL 2 times with a time gap of at least 48 h to evaluate test-retest reliability.

The participants completed Arabic P-QoL, the Australian Pelvic Floor Questionnaire (APFD), the Visual analogue scale (VAS), and the SF-12 to measure convergent construct validity. To measure internal consistency, the Arabic version of P-QoL was compared to the APFD, which is a validated, dependable tool that is used in clinics to evaluate all aspects of PFD signs and seriousness, will provide clinicians with quick and accurate QoL information [

3]. While there are several questionnaires available to determine the signs of PFD, their seriousness, and their effect on QoL, they do not cover all elements of the disorder (bowel, bladder, prolapse, and sexual dysfunction). However, the APFD is a reliable and valid means of assessment [

3].

2.5. Sample Size

Using the G-Power software (version 3.1.9.7) [

21], for an expected Cronbach’s alpha of 0.8 and Significance level (α, two-sided) = 0.05, and a Power of 0.9, a minimum of 78 participants was required for this study.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Using descriptive statistics, sociodemographic features and specific clinical background data were calculated. Before analytical processing, the uncompleted responses were filtered and removed. Floor and ceiling effects were considered if more than 15% of participants achieved the lowest or highest scores respectively [

22].

All Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) program (version 26.0, 2019, New York, USA). The test–retest reliability was evaluated by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Reliability was examined at 95% confidence interval (CI) levels. The absolute measurement error calculated by the smallest detectable change (SDC), also known as the minimum detectable change (MDC 95%) [

23], was obtained by determining the Standard error of measurement (SEM).

Accordingly, internal consistency was measured by means of Cronbach’s alpha. The convergent construct validity evaluation and correlation was done using Spearman’s correlation (r).

3. Results

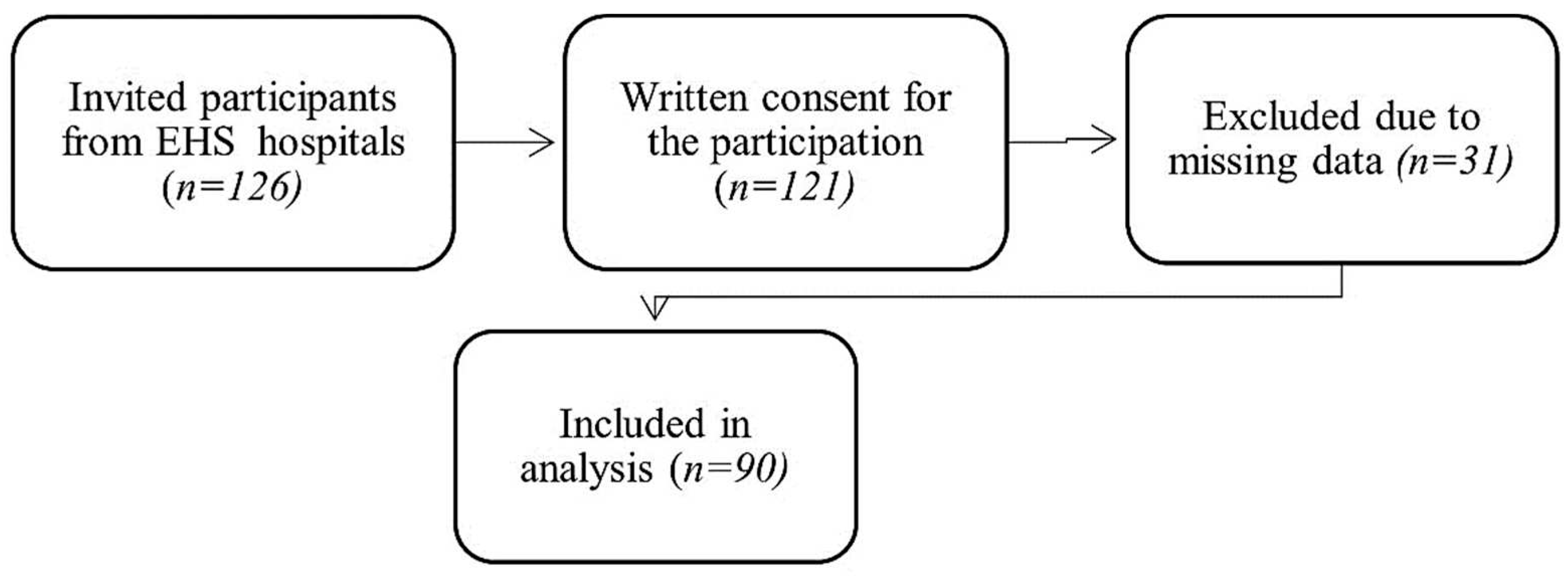

A satisfactory level of semantic, conceptual, idiomatic, and content comparability was reached in the cross-cultural adaptation of the Arabic version of the P-QoL. A total number of 126 participants were recruited across EHS hospitals with and without symptoms of POP. Among 126 Emirati women who were invited, 121 agreed to participate in the study; 31 respondents were excluded from the study due to incomplete responses, and 90 participants completed the study satisfactorily (

Figure 2).

Out of the 90 women involved in this study, 61.11% (55) expressed symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse, whereas 38.89% (35) presented no affecting symptoms.

Table 1 demonstrates the baseline sociodemographic and medical characteristics of the study’s participants, with a mean age (42.53) for the symptomatic group and for the asymptomatic group (33.54).

Table 2 represents the results for test-retest repeatability and internal consistency. The study demonstrates a strong level of internal consistency for the P-QoL measure, as shown by a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of (0.971). The interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the P-QoL measure is (0.987), which indicates a high level of reliability.

Additionally, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the subscales of role limitations, physical limitations, social limitations, personal relationships, emotions, and severity measures range from (0.936) to (0.836), which demonstrates high reliability. However, the sleep and energy domain show a lower, yet still acceptable, level of reliability with a coefficient of (0.682).

Table 3 reports the absolute reliability of the measures, standard error of measurement and minimal detectable change [

24].

Table 4 represents the convergent construct validity (Spearman’s Coefficient (r)) between the P-QoL, the APFD, the SF-12 and the VAS. The convergent construct validity was highly acceptable (moderately strong), reflecting a positive correlation between the Arabic version of the P-QoL and the APFD

r = 0.68 (

p < 0.001), and a significant correlation of the convergent construct validity (CC) of the Arabic version of the P-QoL and the VAS

r = 0.47

(p < 0.001). The correlation between the APFD and the VAS

r = 0.46

(p < 0.001), whereas there is no significant correlation between the SF-12 and the P-QoL, the APFD, and the VAS.

A further detailed statistics correlation was obtained between each subtitle domain of the study tools.

Table 5 represents the convergent construct validity (Spearman’s Coefficient (r)) for each instrument’s subscale between the P-QoL, the APFD, the SF-12 and the VAS. In order to provide a comprehensive elucidation, the convergent construct validity between the Arabic P-QoL subscales and each instrument resulted in a positive correlation of moderate to high between General Health Perceptions (GH), Prolapse Impact (PI), Role Limitations (RL), Physical Limitations (PL), Social Limitations (SL), Personal Relationships (PR), Emotions, Sleep/Energy (SE), Severity Measures (SM), and the APFD ranking from

r = 0.443 (

p < 0.001) to

r = 0.667 (

p < 0.001). While in the APFD subscales, the APFD bladder function shows the highest correlation with the P-QoL subscales with

r = 0.595 (

p < 0.001) to

r = 0.854 (

p < 0.001). In a manner akin to the P-QoL items, there was a positive correlation of moderate to high with the VAS. Conversely, there was no correlation between the P-QoL subscales and the SF-12.

The “Mann-Whitney” test was used to find the discriminative validity between the symptomatic and asymptomatic groups (

Table 6). The significance value of the “Mann-Whitney” test for the effect of pelvic organ prolapse was (

p < 0.001), revealing a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the two groups in the P-QoL, the APDF, and the VAS. The worst POP effects could be seen in the symptomatic group.

4. Discussion

The aim of our study was to validate and culturally adapt the Arabic translated P-QoL as it is a valid and reliable tool in assessing POP. There are a limited number of tools to assess the effects of pelvic organ prolapse on quality of life in the Arabic language. Therefore, the validation of the P-QoL in Arabic was important because it provides clinicians and researchers with a tool that analyzes symptom and the quality of life of women with POP.

The APFD is a valid and reliable tool that has been translated into multiple languages including Arabic [

3,

25], which is used as a comparison tool along with the SF-12 and the VAS. The selection of the APFD was based on the congruence between the dimensions it measures with the P-QoL. The Arabic version of the P-QoL was used to establish a medically and health related quality background check for Arabic-speaking people expressing symptoms of POP, which can be used in developing a treatment plan.

The translation/back-translation process was utilized for the cultural adaptation of the Arabic version of the P-QoL in an identical way to how the Amharic version of the P-QoL was done [

4] where a dual translation process with three steps of translation, cultural adaptation, and psychometric validation was taken. The pilot investigation demonstrated that the P-QoL was effective, albeit with some small adjustments required when finalizing the local language version to enhance technical similarity between the English and Arabic versions.

In our study, the Arabic version of the P-QoL demonstrated great reliability and construct validity, indicating excellent agreement with previous studies. The reliability was tested using test-retest reliability and internal consistency with ICC and Cronbach’s alpha. The internal consistency was high, and the Cronbach alpha scores had a high agreement. The ICC values showed high reliability, indicating a very-good-to-excellent agreement. For further accuracy and to report absolute reliability, a calculation of SEM and MDC done. On reflection, our finding on Cronbach’s Alpha results of test-retest reliability was greater than 0.8, similar to the Persian [

18], the Spanish [

26], and the Polish [

27] versions. The sleep/energy domain had 0.7 in the Persian version. In our Arabic version, the severity measures domain had a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.7, which was similar to the Slovakian [

10] and the Portuguese [

11] studies. These variations among studies reflect the cultural differences, different sample sizes, and an inclusion criterion of volunteers aged 60 or older in the Persian version. Despite the fact that none of the previous studies on the validation of the P-QoL questionnaire used MDC as additional reliability scores, we preferred using it to record the real detectable change on the measurement tool with a 95% confidence threshold [

28].

In regard to validity, the analysis of convergent construct validity represents a good association between the physical functioning, role limitations caused by physical health problems, pain, and general health perception (PCS) dimension in the APFD and in the P-QoL Arabic version, as well as a good correlation of the VAS with the APFD and the P-QoL. The SF-12 Health Survey, on the other hand, exhibited no association with the P-QoL, the APFD, or the VAS. This might imply that POP symptoms influence women’s physical component of perception rather than their mental component, whereas colorectal symptoms affect both physical and emotional perception, Accordingly, most of our symptomatic and asymptomatic volunteers vary in between first and second stage of POP degrees, which may not interfere with their life activities and general health perception listed in the SF-12 Health Survey

. When comparing the scores for the dimensions that evaluate the same symptoms, the P-QoL and the APFD revealed a substantial association, which seems plausible. For example, the role limitation domain (RL) in the P-QoL contains bladder and bowel problems, with the Australian Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (Bladder function) (APFD1) representing (bladder symptoms) and the Australian Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (Bowel function) APFD2 representing (bowel symptoms) as significant correlations at the 0.01 level in

Table 4. Furthermore, symptomatic women had substantially higher total domain scores than asymptomatic. The same method of evaluating convergent construct validity was performed in the Spanish version [

27], where the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7) and Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) were utilized for comparison. Whereas discriminative validity using The Mann-Whitney U test calculated using the median (interquartile range) in the Spanish [

27] and the Dutch versions [

14] we used mean percentage. This result demonstrated that there were statistically significant differences between the P-QoL, the APFD, and the VAS, at a statistically significant value at the level of significance (α ≤ 0.01). With higher average scores, the evidence was in preference of the symptomatic group. It also discovered that there were no statistically significant differences on the SF-12, as the Mann-Whitney test was non-statistically significant.

Limitations

This study included several limitations, including the limited number of elderly (aged 50+), who may express more symptomatic features of POP among life domains, such as role limitation, personal relationship, sleep/energy, and severity measures. Another existing limitation was the high heterogeneity between groups. In addition, this study did not assess the responsiveness of the P-QoL.

5. Conclusions

The Arabic version of the P-QoL showed psychometric resemblance to the English version based on a significant correlation between the Arabic P-QoL, the Arabic APFD and the VAS. The results revealed good reliability, internal consistency, and contrast validity. It is recommended that Arabic-speaking females with pelvic organ prolapse use the Arabic version of P-QoL.

6. Recommendations

Further research is needed to assess the responsiveness of P-QoL.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M., S.T.M, and A.A.A.; methodology, K.M. and A.A.A.; software, K.M., and A.A.A.; validation, A.A.A.; investigation, K.M. and A.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.A.; writing—review and editing, K.M. A.A.A. and S.T.M.; visualization, K.M., and S.T.M.; supervision, K.M, and S.T.M.; project administration, A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by University of Sharjah Research Ethics Committee (REC-21-06-23-02-S), Sharjah, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Contact: rec@Sharjah.ac.ae. Ministry of Health and Prevention Research Ethics Committee has approved this study under the reference number (MOHAP/DXB-REC/ SSN/No. 94/ 2021), UAE. Contact: Yusra.Swaidal@mohap.gov.ae (+971-04-2301631)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their use in further analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Meyer, I.; Morgan, S.L.; Markland, A.D.; Szychowski, J.M.; Richter, H.E. Pelvic Floor Disorder Symptoms and Bone Strength in Postmenopausal Women. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 1777–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuchelo, L.T.; Bezerra, I.M.; Da Silva, A.T.; Gomes, J.; Soares Junior, J.M.; Chada Baracat, E.; de Abreu, L.C.; Sorpreso, I.C. Questionnaires to Evaluate Pelvic Floor Dysfunction in the Postpartum Period: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Womens Health 2018, 10, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaekah, H.; Al Medbel, H.S.; Al Mowallad, S.; Al Asiri, Z.; Albadrani, A.; Abdullah, H. Arabic Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of Australian Pelvic Floor Questionnaire in a Saudi Population. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belayneh, T.; Gebeyehu, A.; Adefris, M.; Rortveit, G.; Genet, T. Translation, Transcultural Adaptation, Reliability and Validation of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quality of Life (P-QoL) in Amharic. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, N.K.; Nieminen, K.; Heikkinen, A.-M.; Jalkanen, J.; Koivurova, S.; Eloranta, M.-L.; Suvitie, P.; Tolppanen, A.-M. Validation of the Short Forms of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20), Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7), and Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12) in Finnish. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digesu, G.A.; Khullar, V.; Cardozo, L.; Robinson, D.; Salvatore, S. P-QOL: A Validated Questionnaire to Assess the Symptoms and Quality of Life of Women with Urogenital Prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2005, 16, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digesu, G.A.; Santamato, S.; Khullar, V.; Santillo, V.; Digesu, A.; Cormio, G.; Loverro, G.; Selvaggi, L. Validation of an Italian Version of the Prolapse Quality of Life Questionnaire. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2003, 106, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, F.; Stammer, H.; Brocker, K.; Rak, M.; Scherg, H.; Sohn, C. Validation of a German Version of the P-QOL Questionnaire. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2009, 20, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svihrova, V.; Digesu, G.A.; Svihra, J.; Hudeckova, H.; Kliment, J.; Swift, S. Validation of the Slovakian Version of the P-QOL Questionnaire. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010, 21, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.S.; Tamanini, J.T.N.; de Aguiar Cavalcanti, G. Validation of the Prolapse Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (P-QoL) in Portuguese Version in Brazilian Women. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2009, 20, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchana, T.; Bunyavejchevin, S. Validation of the Prolapse Quality of Life (P-QOL) Questionnaire in Thai Version. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010, 21, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, Y.; Uesaka, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Ito, S.; Yamanaka, M.; Takeyama, M.; Noma, M. Assessment of Quality of Life in Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Conditional Translation and Trial of p-Qol for Use in Japan. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 2008, 99, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claerhout, F.; Moons, P.; Ghesquiere, S.; Verguts, J.; De Ridder, D.; Deprest, J. Validity, Reliability and Responsiveness of a Dutch Version of the Prolapse Quality-of-Life (P-QoL) Questionnaire. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010, 21, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, C.; Van Rooyen, C.; Cronje, H. Validation of the Prolapse Quality of Life Questionnaire (P-QOL): An Afrikaans Version in a South African Population. S. Afr. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. (1999) 2016, 22, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojomi, M.; Digesu, G.A.; Khullar, V.; Morovatdar, N.; Haghighi, L.; Alirezaei, M.; Swift, S. Validation of Persian Version of the Prolapse Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (P-QOL). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2012, 23, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazi, T.; Kabakian-Khasholian, T.; Ezzeddine, D.; Ayoub, H. Validation of an Arabic Version of the Global Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2013, 121, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbiss, H.M.; Osman, N.; Hammad, F.T. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Severity of Symptoms of Pelvic Organ Prolapse among Emirati Women. BMC Urol. 2015, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, V.B.; Ferreira, C.H.J.; da Silva, J.B.; de Oliveira Esmeraldo, G.N.D.; Brito, L.G.O.; do Nascimento, S.L.; Driusso, P. Responsiveness of Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7) after Pelvic Floor Muscle Training in Women with Stress and Mixed Urinary Incontinence. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 255, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bump, R.C.; Mattiasson, A.; Bø, K.; Brubaker, L.P.; DeLancey, J.O.L.; Klarskov, P.; Shull, B.L.; Smith, A.R.B. The Standardization of Terminology of Female Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 175, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cam, C.; Sakalli, M.; Ay, P.; Aran, T.; Cam, M.; Karateke, A. Validation of the Prolapse Quality of Life Questionnaire (P-QOL) in a Turkish Population. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2007, 135, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdfelder, E.; Faul, F.; Buchner, A. GPOWER: A General Power Analysis Program. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1996, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.R.; Harris, K.; Dawson, J.; Beard, D.J.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Price, A.J. Floor and Ceiling Effects in the OHS: An Analysis of the NHS PROMs Data Set. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kampen, D.A.; Willems, W.; van Beers, L.W.A.H.; Castelein, R.M.; Scholtes, V.A.B.; Terwee, C.B. Determination and Comparison of the Smallest Detectable Change (SDC) and the Minimal Important Change (MIC) of Four-Shoulder Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs). J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2013, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dontje, M.L.; Dall, P.M.; Skelton, D.A.; Gill, J.M.R.; Chastin, S.F.M.; on behalf of the Seniors USP Team. Reliability, Minimal Detectable Change and Responsiveness to Change: Indicators to Select the Best Method to Measure Sedentary Behaviour in Older Adults in Different Study Designs. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billis, E.; Kritikou, S.; Konstantinidou, E.; Fousekis, K.; Deltsidou, A.; Sergaki, C.; Giannitsas, K. The Greek Version of the Australian Pelvic Floor Questionnaire: Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation amongst Women with Urinary Incontinence. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 279, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, B.; Yuste-Sánchez, M.J.; Arranz-Martín, B.; Navarro-Brazález, B.; Romay-Barrero, H.; Torres-Lacomba, M. Quality of Life in POP: Validity, Reliability and Responsiveness of the Prolapse Quality of Life Questionnaire (P-QoL) in Spanish Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzepka, J.; Zalewski, K.; Stefanowicz, A.; Khullar, V.; Swift, S.; Digesu, G.A. Validation of the Polish Version of P-QoL Questionnaire. Ginekol. Pol. 2016, 87, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, B.A.; Kautz, S.A.; Bowden, M.G.; Velozo, C.A. Revisiting the Concept of Minimal Detectable Change for Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).