1. Introduction

Due to the importance of environmental issues and ever-changing societal expectations, many businesses are involved in various corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities (Raza et al., 2023). To facilitate sustainable marketing strategies and gain a competitive advantage, hospitality managers try to adopt effective CSR strategies relevant to environmental concerns. (Ekasari, 2021). Among the diverse hospitality businesses, the coffee shop industry actively engages in various CSR activities as a presumably distinctive marketing strategy under their competitive market environment. In addition, CSR practice has become an obligation of brand coffee shops to enhance their brand image and loyalty because the coffee shop industry has been criticized for plastic cup overuse (Nicolau et al., 2022). The Starbucks corporation, for example, has implemented different CSR practices such as recycling paper cups, providing reusable mugs and tumblers, reducing energy and water consumption, and constructing LEED-certified eco-friendly stores (Starbucks, 2022).

Many coffee shops are facing the issue of gaining loyal customers and maintaining a high proportion of brand roamers (Han et al., 2018). Considering the competitive coffee shop industry, the CSR’s effect on customers’ emotional or behavioral responses (e.g., emotions, attitudes, satisfaction, brand loyalty) is questionable because the presumption is a trade-off between CSR practices and customer responses. Previous studies have demonstrated that CSR practices can positively strengthen brand image and loyalty and revisit intention in the context of hospitality (Akbari, 2021; Martinez et al., 2014; Simakhajornboon & Sirichodnisakorn, 2022). Yet recent studies have also shown that customers are skeptical about pro-environmental practices in the hospitality sector since customers tend to avoid challenging, inconvenient, or financially unappealing pro-environmental behaviors (Baker et al., 2014; Jeong & Jang, 2010). In addition, CSR practices that fail to grasp the customers’ perception may weaken positive emotions toward the brand or cause repetitive purchases (Sui & Baloglu, 2003).

The inconclusive research findings indicate that the effects of CSR practices on customer loyalty vary depending on other antecedents or mediators between them such as individual personality, beliefs, social norms, and the like (Jang et al., 2015). Regarding the antecedents, recent branding studies suggest a concept of brand lovemark as a factor that can nullify the fluctuating relationship between CSR practices and brand loyalty. Customers with a high level of lovemark for a particular brand frequently buy one brand and do not switch to another one regardless of the marketing strategy, including CSR practices (Song et al., 2019). Starbucks is referred to as an exemplary lovemark brand in terms of brand loyalty and customer retention.

The relationship between CSR practices and customer behavioral outcomes can be affected by several factors relevant to individual demographic characteristics or personal values (Hur et al., 2016). Among these, scholars have considered gender a key factor in demonstrating differences in customer behavioral intentions toward CSR practices (Jones et al., 2017). Therefore, we examine how gender interacts with the level of brand lovemark in customers’ behavioral outcomes in coffee shops. With these realizations, the primary purposes of the study are (1) to identify the impact of brand lovemark (i.e., brand love and brand respect) in understanding the relationship between CSR practices and customers’ behavioral outcomes (i.e., green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a $1 deposit, and machine use intention) and (2) to examine the interaction effect between gender and the level of lovemark in customers’ behavioral outcomes (i.e., green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a $1 deposit, and machine use intention).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Lovemarks Theory: Brand Love and Brand Respect

Lovemarks refer to a brand, event, and experience that people love passionately and suggests that the “lovemark brand” scores high in the two lovemark dimensions, “love” and “respect” (Roberts, 2004). Specifically, brand respect emphasizes the functional aspects of a brand and mainly includes the brand’s performance, reputation, and trust. Brand love, on the other hand, contains the emotional elements of a brand that consumers use to build emotional relationships with it (Pawle & Cooper, 2006). Lovemarks theory can justify why consumers feel loyal and attached to a particular brand, and it describes that the loyalty for “lovemark” is loyalty beyond reason (Roberts, 2004). Furthermore, Robert (2004) provided a robust mechanism of lovemarks and characteristics to clarify the relationship between certain brands and loyal customers. Lovemark brands can usually boost customers’ loyalty and build a more stable relationship between customers and brands in the long term (Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006).

Previous research has demonstrated that brand lovemark (i.e., brand love and respect) has a significant moderation effect on the relationship between trust and brand loyalty for named coffee shops (Song et al., 2019). In the banking industry, Amegbe et al. (2021) showed that brand respect significantly moderates the relationship between CSR and trust. However, in the context of hospitality research, few studies have examined the impact of brand lovemark in explaining the relationship between CSR practices and customers’ behavioral outcomes. In this paper, we will explore the impact of brand lovemark in understanding customers’ behavioral outcomes on CSR practices. We assume that customers with a high level of brand lovemark have a stronger impact on behavioral outcomes toward CSR practices than those with a low level of brand lovemark.

H1. Compared to customers with a low-brand lovemark, CSR practices have a stronger positive impact on behavioral outcomes for those with a high-brand lovemark.

H1a: Compared to customers with a low-brand lovemark, CSR practices have a stronger positive impact on perceived green brand loyalty for those with a high-brand lovemark.

H1b: Compared to customers with a low-brand lovemark, CSR practices have a stronger positive impact on willingness to pay a $1 deposit for those with a high-brand lovemark.

H1c: Compared to customers with a low-brand lovemark, CSR practices have a stronger positive impact on machine use intention for those with a high-brand lovemark.

2.2. CSR Practices on Consumer Behavioral Outcomes in the Coffee Shop Industry

CSR refers to a corporation’s consistent commitment to ethical practices, environmental issues, and improving the quality of life of employees and society as a whole (Kim et al., 2020). With the coffee shop industry’s increasing competitiveness and changing social expectations, CSR has recently attracted much interest from many scholars. Among CSR dimensions, environmental practices refer to actions, activities, and processes that prioritize environment protection as well as products and services generated in a way that reduces corporations’ negative impact on the ecosystem (Atzori & Murphy, 2018). Environmental practices in coffee shops may include energy efficiency, water efficiency, recycling, sustainable food, reduced waste, and pollution prevention (Hu et al., 2010). Among numerous coffee shop brands, Starbucks is one of the most well-known brands internationally, leading the green movement in the hospitality industry. Its environmental practices include avoiding plastic cups, recommending reusable cups, and implementing front-of-store and back-of-store recycling (Tsai et al., 2020).

Previous studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between CSR perception and customers’ behavioral outcomes (e.g., brand loyalty, intention to visit, or pay a premium price; Akbari, 2021; Simakhajornboon & Sirichodnisakorn, 2022). However, CSR studies’ findings in the hospitality industry are inconsistent. Although most previous studies demonstrate the positive effects of CSR practices on customers’ positive responses (e.g., trust, satisfaction, and brand loyalty) in the hospitality industry (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Creyer, 1997), some studies showed that CSR practices in the hospitality industry have barriers such as discomfort or skepticism for customers to participate. Furthermore, some research has demonstrated an inconsistency between consumers’ exposed attitudes toward the environment and their actual behavior (Barber, 2012). Based on the previous discussion, our study assumes that brand lovemark as an antecedent variable can nullify the irregular relationship between CSR practices and customers’ behavioral outcomes.

2.3. Green Brand Loyalty

Brand loyalty is defined as customers’ repetitive purchase behavior with positive emotions and behavioral tendencies for certain brands (Oliver, 1999). Likewise, if customers have high levels of brand loyalty, they do not switch to another brand and buy it, regardless of the change in marketing strategies (Palazon & Delgado, 2009). Relatedly, green brand loyalty refers to the customers’ consistent commitment to a green business by repurchasing its products (ÇavuĢoğlu et al., 2020). Accordingly, customers who are loyal to a certain brand are likely to make repeat purchases or purchase other products and services from the same brand (Sui & Baloglu, 2003). And Song et al. (2019) showed that customers’ brand love and respect could initiate repeated purchases and word-of-mouth. Thus, customers’ strong brand lovemark is expected to generate brand loyalty and promote repurchases from the brand. Previous literature demonstrated that customers’ brand love and respect could strengthen brand loyalty (Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006). This study assumes that when customers have a high-brand lovemark for the coffee shop, they will be loyal to that specific coffee shop, which improves customers’ support for that same brand’s environmental practices.

2.4. Gender Effects in CSR Practices

The effect of gender differences on CSR practices has also been investigated within the hospitality literature. Gender is considered a crucial demographic factor for identifying consumers’ behaviors to CSR practices (Patino et al., 2014). Generally, customers’ overall positive responses toward CSR practices are higher in females than males (Kim & Kim, 2016). Hur et al. (2016) also demonstrated that the positively perceived CSR practices had a greater impact on female consumers than male consumers. However, from the brand standpoint, even though both men and women are consumers of certain brands, their attitudes toward certain brands differ as a function of gender (Seeley et al., 2003). According to social identity theory, a person’s self-identity and values are highly correlated to gender (Tajfel, 1978). The self-identity of women typically care about close individual relationships; men tend to extend their self-identity to a broader social group. Thus, it seems plausible that men are more loyal than women to a group such as a company or a certain brand (Kim et al., 2006; Melnyk, 2009). Hur et al. (2016) identified that compared with female consumers, the positive impact of CSR perception on brand equity was higher in male consumers. Accordingly, identifying the interaction between brand lovemark and gender can be a strong indicator in understanding customers’ behavioral outcomes toward CSR practices. Based on the previous literature, we assume that:

H2. There is an interaction effect between brand lovemark (low vs. high) and gender in behavioral outcomes regarding CSR practices.

H2a:

There is an interaction effect between brand lovemark (low vs.high) and gender in perceived green brand loyalty regarding CSR practices.

H2b: There is an interaction effect between brand lovemark (low vs. high) and gender in willingness to pay a $1 deposit regarding CSR practices.

H2c: There is an interaction effect between brand lovemark (low vs. high) and gender in machine use intention regarding CSR practices.

2.5. Proposed Model

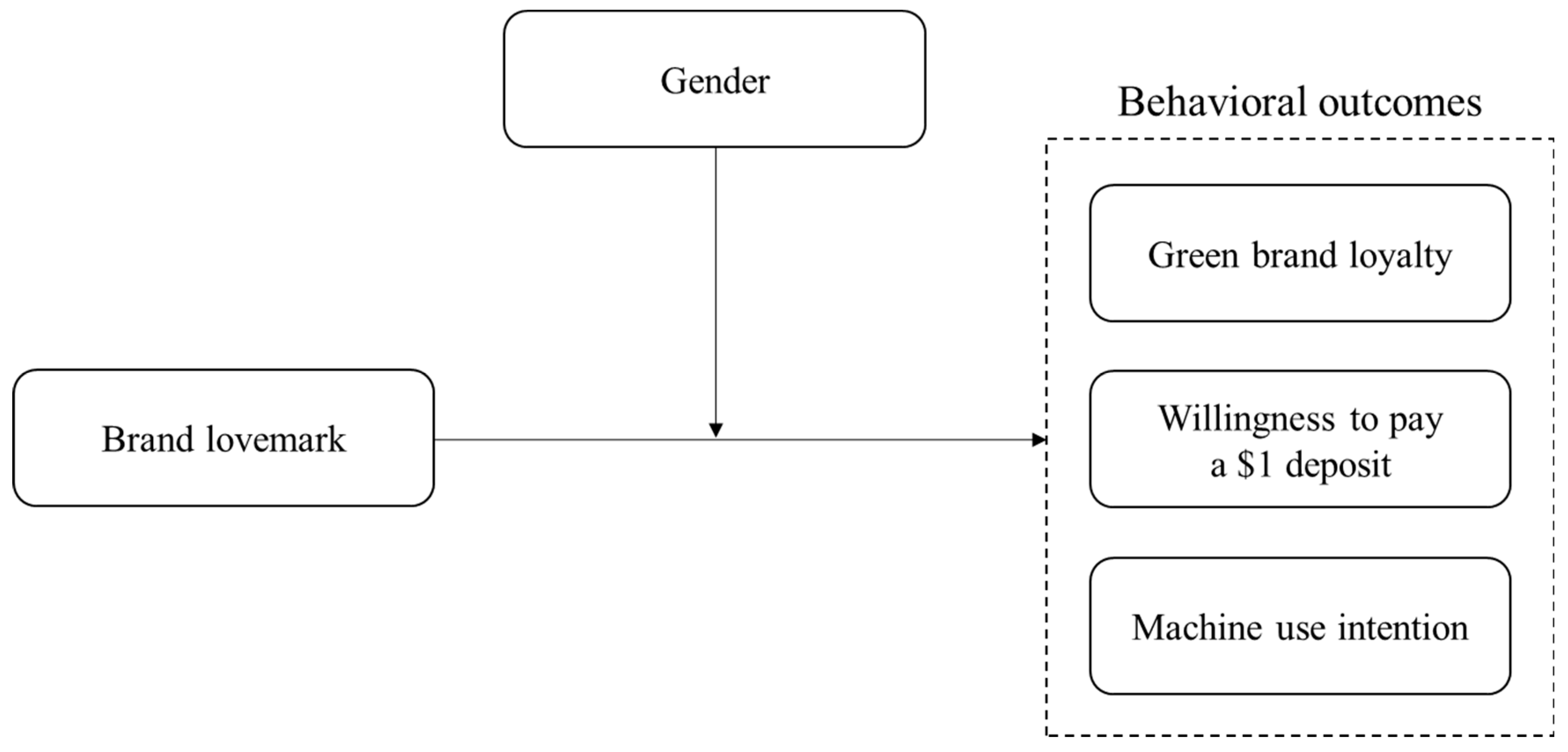

We suggested this study’s proposed research model in

Figure 1, including brand lovemark, gender, perceived green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a

$1 deposit, and machine use intention. The six hypotheses are presented in the proposed theoretical framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design and Sample

This study used a scenario-based experimental design on CSR practices in two coffee shop brands (i.e., Starbucks and Dunkin’). We believe that Starbucks and Dunkin’ are valid for this survey because they are representative examples of the lovemark brand in the coffee shop industry, dominating a market share of 36.7% and 24.6%, respectively, in the US. They have many loyal customers who frequently buy their brand and do not switch to another brand regardless of the change in marketing strategy (Palazon & Delgado, 2009). The participants were recruited from Qualtrics, an online survey and consumer panel company. Data were collected from a total of 263 respondents. To be eligible, the respondents should have previously visited Starbucks or Dunkin’.

3.2. Procedures and Stimuli

All respondents were first instructed to answer their café use characteristics before being assigned to one of two scenarios. Then, each participant was randomly assigned to one of two hypothetical scenario-experimental designs (i.e., Starbucks or Dunkin’). They were asked to answer a screening question about their previous coffee shop experience. For example, “Have you ever visited Starbucks before?” If a participant answered “No,” they were excluded from the analysis. Second, they were asked to answer the extent of their brand lovemark for Starbucks or Dunkin’. Next, they were asked to read an imaginary announcement that the coffee shop (i.e., Starbucks or Dunkin’) would install a new cup-return machine at the store to eliminate single-use plastic and paper cups in the US and encourage reusable cups. This announcement also included the content that a one-dollar (

$1) deposit would be charged for each cup, which would be refunded when customers returned them to a machine at the store (see

Appendix A). We also included a manipulation check question to ensure that the manipulation for the announcement worked as expected. In both scenarios, they were asked to answer, “How much deposit will be charged for each cup when you use a reusable cup at the store?” They were also excluded from the analysis if they did not provide the correct answer to the question. After they completed the manipulation check for the scenario question, the participants answered the remaining questions, including willingness to pay a

$1 deposit, machine use intention, and green brand loyalty. Lastly, they were asked to answer their demographic characteristics.

3.3. Measures

We adopted survey measurement items based on previous studies and modified them to match our research. The manipulation check of the research scenario about each coffee shop was: “According to the announcement you read on the previous page, how much deposit will be charged for each cup when you use a reusable cup at the store?” All measurement items were assessed on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) in addition to café visit characteristics and demographic information. In particular, the measurement items were evaluated through a review of the literature related to brand lovemark (Cho & Fiore, 2015), machine use intention (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000), green brand loyalty (Jang et al., 2015), and willingness to pay a $1 deposit (Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006).

4. Result

4.1. The Profile of Participants

The respondents’ demographic characteristics are provided in

Table 1. A balanced gender distribution was confirmed: 52.9 % of respondents were males, the remaining 47.1% were females. Most respondents were between 31–40 (44.9%) years of age, followed by 30 or under (35.4%) years of age. Almost half the survey respondents graduated from college, accounting for 49.4% of the total responses. And 31.6% of respondents had a household income between

$40,000 to

$59,999.

4.2. Coffee Shop-Visit-Related Characteristics of the Respondents

A summary of coffee shop-visit-related characteristics of 233 respondents is reported in

Table 2. The visit frequency of coffee shops is 3–4 a week (36.5%), followed by every day (31.2%). Most respondents preferred national/regional chain coffee shops (75.7%). Their main purpose for visiting coffee shops is to relax and enjoy the ambiance (56.3%), and a primary factor affecting visiting coffee shops is coffee quality (73.0%).

4.3. Mean Difference between the Levels of Brand Lovemark (Low vs. High) on Behavioral Outcomes toward CSR Practices

We conducted the independent t-test to demonstrate a significant mean difference in behavioral outcomes (i.e., green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a

$1 deposit, and machine use intention) depending on the levels of brand lovemark (low vs. high) toward CSR practices (see

Table 3). The results showed that there is a significant mean difference in green brand loyalty (M

low- brand lovemark = 4.58, M

high-brand lovemark = 5.99;

t = -12.192,

p < .001), willingness to pay a

$1 deposit (M

low-brand lovemark = 4.71, M

high-brand lovemark = 6.08;

t = -10.444,

p < .001), and machine use intention (M

low-brand lovemark = 4.51, M

high-brand lovemark = 5.94;

t = -10.940,

p < .001) in two levels of brand lovemark. This result demonstrated that customers in the high-brand lovemark group’s three behavioral outcomes (i.e., green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a

$1 deposit, and machine use intention) were significantly higher than those of the low lovemark brand group. Hence, H1 was supported.

4.4. Mean Difference between Gender (Male vs. Female) on Behavioral Outcomes toward CSR Practices

We conducted the independent t-test to demonstrate a significant mean difference of gender (male vs. female) in behavioral outcomes (i.e., green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a

$1 deposit, and machine use intention) toward CSR practices (see

Table 4). The results showed a significant mean difference in green brand loyalty (M

male = 5.49, M

female = 5.51;

t = -.155,

p < .05), willingness to pay a

$1 deposit (M

male = 5.54, M

female = 5.66;

t = -.922,

p < .001), and machine use intention (M

male = 5.43, M

female = 5.44;

t = -.034,

p < .05) by gender. This result demonstrated that females were found to be higher in all three behavioral outcomes on CSR practices than males.

4.5. Validity and Reliability

Confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS v.21.0 was conducted to assess the constructs for convergent validity and discriminant validity. To examine the model’s goodness-of-fit, we used various model fit indices such as Chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ

2/

df), normed fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Afthanorhan et al., 2019). χ

2/

df values less than 3 and RMSEA values less than 0.08 indicate an acceptable fit, respectively. NFI, IFI, TLI, and CFI values greater than 0.9 are a good fit (Hair et al., 2019). The model fit indices were as follows: χ

2/

df = 2.606, NFI = 0.914, IFI = 0.946, TLI = 0.932, CFI = 0.945, and RMSEA = 0.078. As shown in

Table 5, factor loadings were above 0.6. The values for composite reliability were higher than the recommended threshold of 0.7, and the values for average variance extracted (AVE) also exceeded the recommended 0.5, providing robust support for the convergent validity (Hair et al., 2019).

Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to see the correlation among four variables in the data set. The data set consisted of one antecedent variable (i.e., lovemark) and three dependent variables (i.e., green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a

$1 deposit, and machine use intention).

Table 6 presents the correlation matrix constructed to summarize the correlational data. The correlation among the four variables was significant at a 0.05 level. As shown in

Table 6, the values of the square root AVE (in bold) were higher than the values of construct correlation, supporting the discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2019). Cronbach’s α was located between 0.787 and 0.884, supporting internal consistency (Nunnally, 1978).

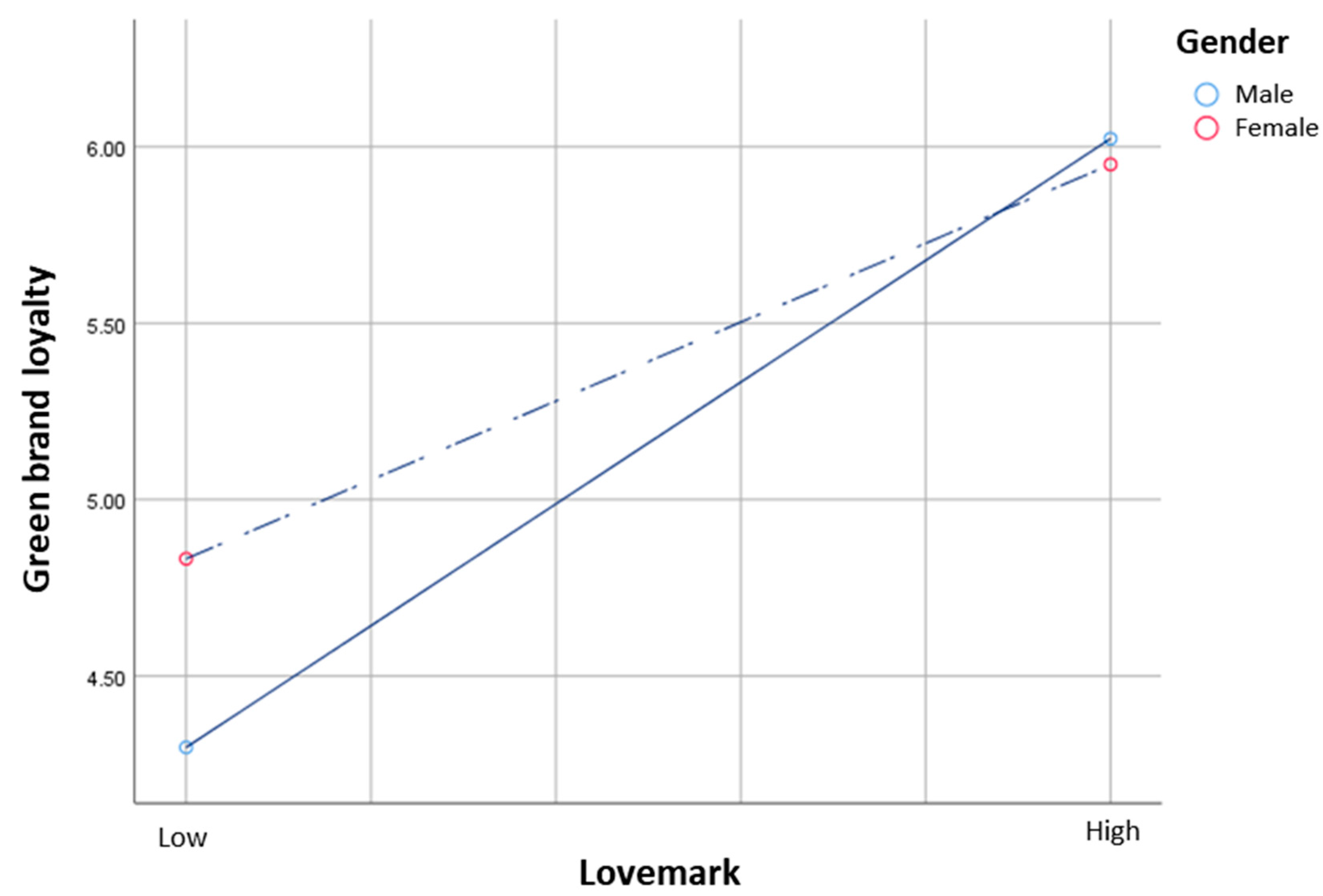

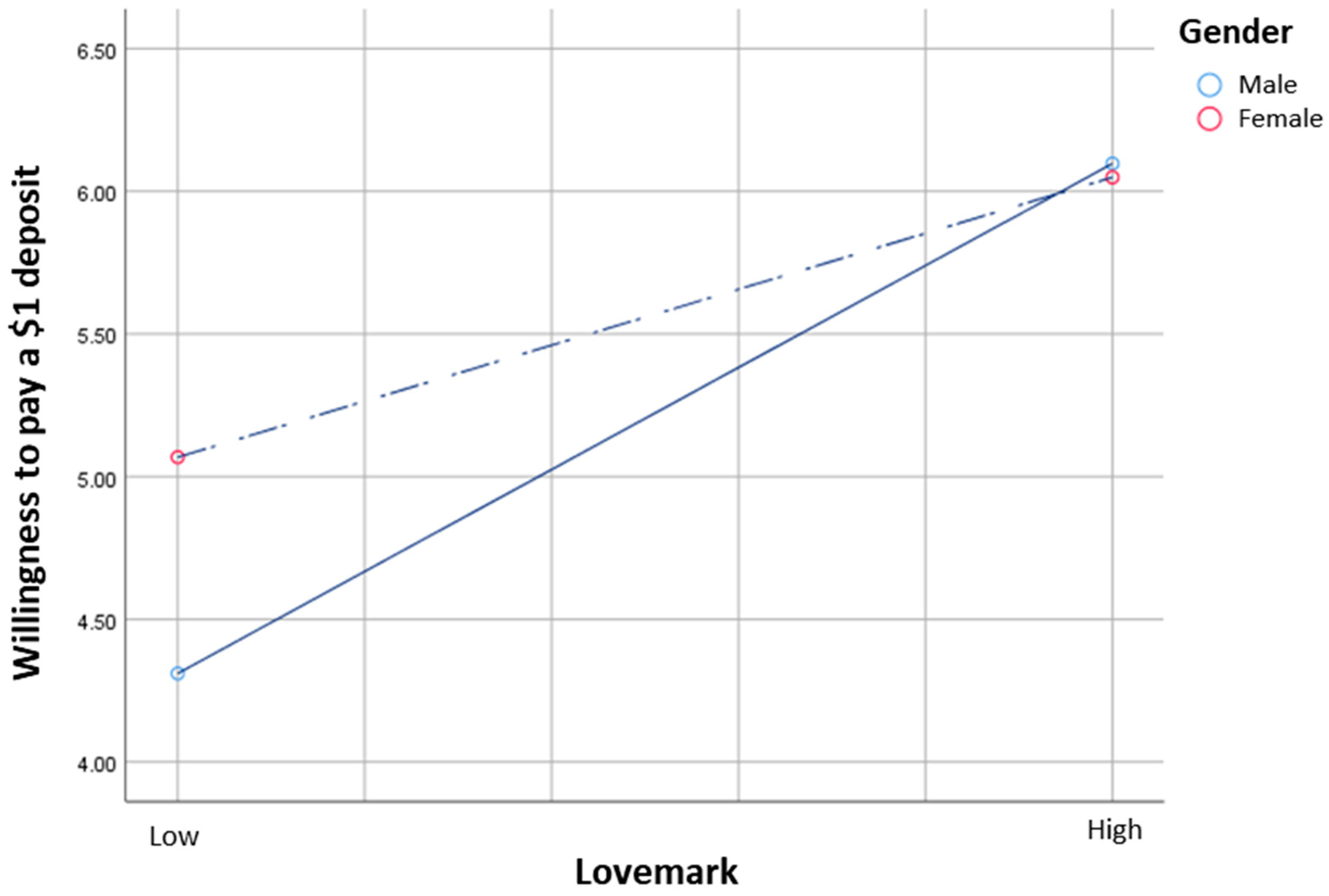

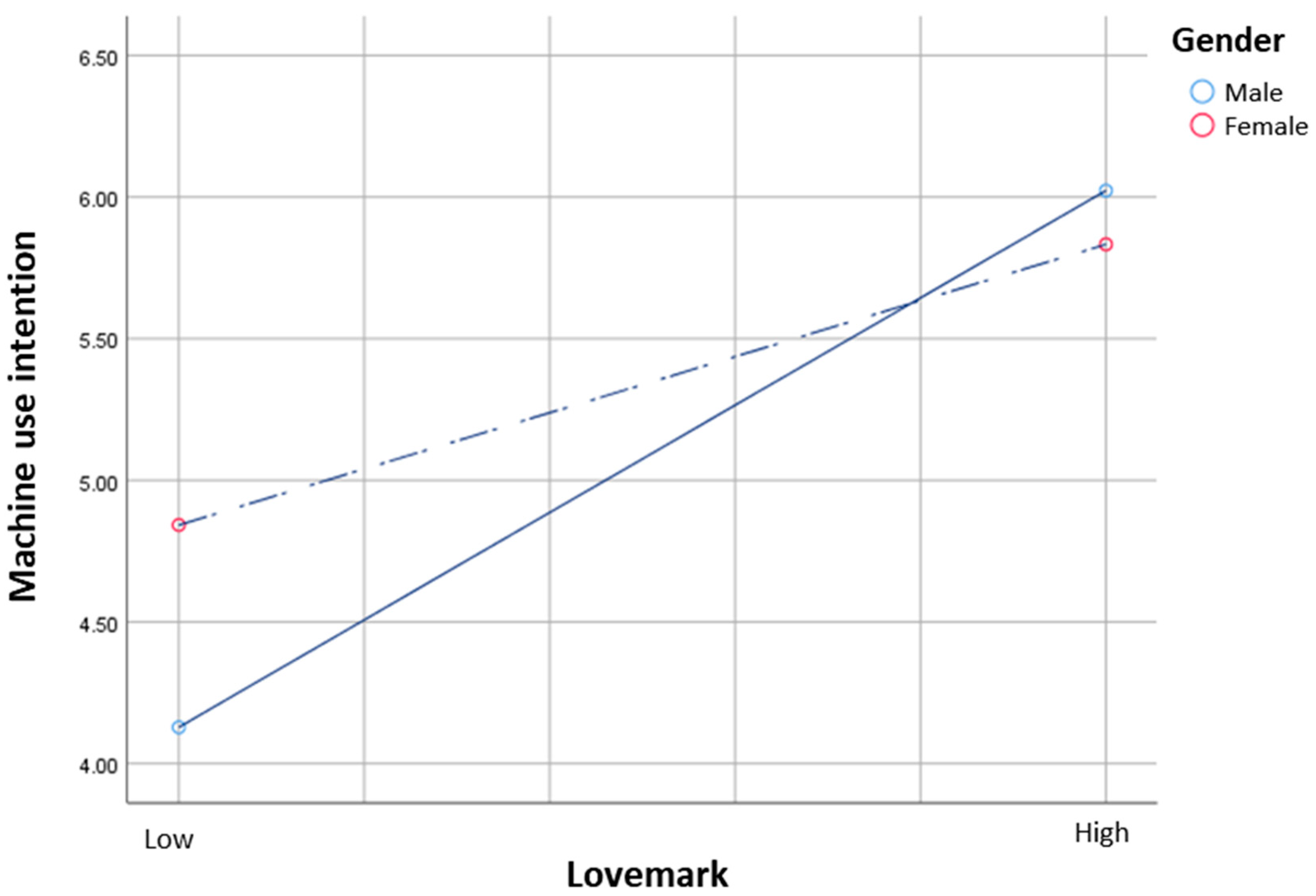

4.6. The Interaction Effect of the Levels of Brand Lovemark and Gender on Behavioral Outcomes

To test the main effect of lovemark and the moderating role of gender on the relationship between lovemark and customers’ behavioral outcomes, this study employed PROCESS v.4.0 macro Model 1 developed by Hayes (2017), using bootstrap procedures with 5,000 samples. Lovemark was found to have a positive significant effect on green brand loyalty (

β = 1.727,

p < 0.001), willingness to pay a

$1 deposit (

β = 1.787,

p < 0.001), and machine use intention (

β = 1.896,

p < 0.001). The interaction terms of lovemark and gender were statistically significant on green brand loyalty (

β = -0.609,

p < 0.01), willingness to pay a

$1 deposit (

β = -0.806,

p < 0.001), and machine use intention (

β = -0.904,

p < 0.001). The amount of change in

R2 by the interaction terms was significant on green brand loyalty (Δ

R2 = 0.021,

p < 0.01), willingness to pay a

$1 deposit (Δ

R2 = 0.033,

p < 0.001), and machine use intention (Δ

R2 = 0.039,

p < 0.001) (see

Table 7).

The conditional effects were checked, as shown in

Table 8. For males, lovemark was positively and strongly related to green brand loyalty (

β = 1.727, 95% CI = 1.466 to 1.988), willingness to pay a

$1 deposit (

β = 1.787, 95% CI = 1.499 to 2.076), and machine use intention (

β = 1.896, 95% CI = 1.600 to 2.192). For females, the positive relationships were weaker between lovemark and green brand loyalty (

β = 1.118, 95% CI = 0.857 to 1.380), willingness to pay a

$1 deposit (

β = 0.981, 95% CI = 0.692 to 1.270), and machine use intention (

β = 0.991, 95% CI = 0.695 to 1.288), respectively (see

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Thus, H2 was all supported.

5. Discussion

This study’s findings are expected to provide some meaningful implications for a better understanding of consumers’ perceptions and attitudes toward CSR practices in the coffee industry, depending on customers’ level of brand love and respect.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This research makes a theoretical contribution to the literature by using the lovemark theory to fill in knowledge gaps regarding the fluctuating relationship between CSR practices and customers’ behavioral responses in the coffee shop industry. First, this study extends the hospitality CSR strategies by adopting the lovemark theory on customers’ behavioral responses in the coffee shop industry. We examine whether consumers with a high level of brand lovemark respond more positively to new CSR practices than do customers with a low level of brand lovemark. Overall, this study result showed that the brand lovemark had stronger effects on customers’ behavioral responses toward CSR practices. This study could embark on empirical research to identify how customers’ brand lovemark positively influences customers’ behavioral responses to CSR practices. And applying the lovemark theory to CSR studies in the coffee shop industry can contribute to the body of knowledge regarding CSR research in that area.

Second, this study adds to the hospitality literature by confirming the interaction effect between two levels of brand lovemark (low vs. high) and gender (male vs. female) on behavioral outcomes (i.e., green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a $1 deposit, and machine use intention). We identified differences in how men and women perceive differently depending on brand lovemark. Specifically, our findings indicated that in customers with a low-brand lovemark, all three behavioral outcomes (i.e., green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a $1 deposit, and machine use intention) are significantly lower in males than females. Yet, in customers with a high-level brand lovemark, males have a higher level of behavioral outcomes (i.e., green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a $1 deposit, and machine use intention) than females. This study’s findings are similar to Hur et al.’s (2016), which confirmed that the positive impact of CSR perception on brand equity was higher in female consumers than male consumers. Based on the previous literature, this study’s result in the hospitality CSR marketing area suggests further empirical evidence to emphasize the importance of different CSR strategies depending on gender and the different levels of the lovemark groups to increase customer engagement. Extending this stream of research, our findings contribute to this type of research in the coffee shop industry.

5.2. Managerial Implications

The current research provides several implications for marketing practices. First, this study provided foundational work by adopting the lovemark theory in the coffee shop industry context. This study suggests, then, a great opportunity for coffee shop managers to develop a brand lovemark by confirming the relationship between CSR practices and behavioral outcomes (i.e., green brand loyalty, willingness to pay a $1 deposit, and machine use intention). Furthermore, it is highly beneficial for hospitality organizations to understand the impact of brand lovemark that enhance their effectiveness. Specifically, hospitality marketers should be aware that CSR practices’ effectiveness of can differ depending on customers’ level of brand lovemark. Likewise, given the increasing attention to sustainable marketing strategies, hospitality marketers should be more concerned about their CSR practices, develop them, and commit to them as the starting point for building a customer loyalty roadmap. Although it is well known that CSR practices are effective in increasing customer loyalty, hospitality marketers seem to neglect the importance of brand love and respect in eliciting customer engagement. As such, there is room for hospitality corporations to increase their CSR marketing effectiveness by using customers’ brand lovemark.

Second, our findings will show marketers in coffee shops how to effectively target certain segmentations of the population and provide better insights into formulating more effective marketing strategies from the gender difference standpoint. Specifically, our study suggests that marketers should use the interaction between gender and the level of brand lovemark as critical factors for CSR engagement. Since coffee shops have limited CSR-related marketing resources, the CSR marketing effects can be productively achieved using specific interactions between gender and brand lovemark. Specifically, this finding shows that in a high-level brand lovemark group, male consumers are more likely to engage in the CSR practices of the coffee shop than female consumers. In the case of a low-level brand lovemark group, female consumers have a much higher behavioral intention toward CSR activities than male consumers. Thus, marketers can benefit from providing female consumers with detailed information about their CSR activities and emphasizing the importance of engagement in them. On the other hand, for male consumers, focusing on improving their brand lovemark for the coffee shop itself will automatically increase their support level for the coffee shop’s CSR activities.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this research provides theoretical contributions and managerial practices, a series of limitations should be acknowledged to provide future research directions. First, this study used a scenario-based approach and investigated how respondents would react in that given situation. Due to the nature of the experimental design, its generalizability is limited. Future studies should test the proposed effects in the context of real settings to identify the actual responses. Second, this research concentrates only on two different coffee shop chains (i.e., Starbucks and Dunkin’) for the research design. Therefore, further research is recommended to examine the customer responses about their CSR practices in other coffee shop chains (e.g., Caribou Coffee, The Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf) or comparatively unknown coffee shops to generalize this study’s findings. Third, current research has not studied the attributes related to customers’ responses to a new cup-return machine. Further investigations should include customers’ perceptions or attitudes on adopting the cup return machine to understand this study further. Fourth, this research is limited to coffee shops. Future research can be extended to various settings to explore brand lovemark in various hospitality industry segments (e.g., hotels or restaurants).

Appendix A

CSR Research Scenario

Now, you will read an imaginary announcement about Starbucks coffee's new policy.

Imagine that Starbucks announced its new policies to eliminate single-use plastic and paper cups in the US and encourage reusable mugs starting in March. 2023. They have a broader goal to cut its waste and carbon emissions from direct operations in half by 2030 as it aims to become “resource positive” one day. Disposable cups and lids comprise 40% of the company’s packaging waste. All stores will only serve drinks in coffee mugs, tumblers brought by customers, or the café’s reusable plastic cups. The reusable cups are plastic but sturdier than single-use cups and can be used 70 to 100 times when washed. A dollar ($1) deposit will be charged for each cup, which is refunded when customers return them to the store's return machine. Customers can choose to get a refund in cash or Starbucks loyalty points. The reusable cups need to be rinsed before being returned, and the few options for customers are the cafe’s water fountain, a nearby bathroom, or cleaning it at home and bringing it back later.

Starbucks will soon have a cup-washing station in the cafe to make the process easier, but a specific date was not given.

Appendix B

Examples of Research Scenario Used in This Study

References

- Afthanorhan, A., Awang, Z., Rashid, N., Foziah, H., & Ghazali, P. Assessing the effects of service quality on customer satisfaction. Management Science Letters 2019, 9, 13–24.

- Akbari, M., Nazarian, A., Foroudi, P., Seyyed Amiri, N., & Ezatabadipoor, E. How corporate social responsibility contributes to strengthening brand loyalty, hotel positioning and intention to revisit? Current Issues in Tourism 2021, 24, 1897–1917.

- Amegbe, H., Dzandu, M. D., & Hanu, C. The role of brand love on bank customers' perceptions of corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Bank Marketing 2021, 39, 189–208.

- Atzori, R., Shapoval, V., & Murphy, K. S. Measuring Generation Y consumers' perceptions of green practices at Starbucks: An IPA analysis. Journal of foodservice business research 2018, 21, 1–21.

- Baker, M. A., Davis, E. A., & Weaver, P. A. Eco-friendly attitudes, barriers to participation, and differences in behavior at green hotels. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 2014, 55, 89–99.

- Barber, N. Consumers' intention to purchase environmentally friendly wines: a segmentation approach. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration 2012, 13, 26–47.

- Carroll, B.A. and Ahuvia, A.C. "Some antecedents and outcomes of Brand love,". Marketing Letters 2006, 17, 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M., & Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer–do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? Journal of consumer marketing 2001.

- ÇavuĢoğlu, S., Demirağ, B., Jusuf, E., & Gunardi, A. The effect of attitudes toward green behaviors on green image, green customer satisfaction and green customer loyalty. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 2020, 33, 1513–1519.

- Cho, E., & Fiore, A. M. Conceptualization of a holistic brand image measure for fashion-related brands. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2015.

- Creyer, E. H. The influence of firm behavior on purchase intention: do consumers really care about business ethics? Journal of consumer Marketing 1997.

- Ekasari, A. In-store communication of reusable bag: Application of goal-framing theory. Jurnal Manajemen dan Pemasaran Jasa 2021, 14, 123–134. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. In Multivariate data analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning, 2019.

- Han, H., Nguyen, H. N., Song, H., Chua, B. L., Lee, S., & Kim, W. Drivers of brand loyalty in the chain coffee shop industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2018, 72, 86–97.

- Hayes, A. F. In Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach; Guilford publications, 2017.

- Hu, H. H., Parsa, H. G., & Self, J. The dynamics of green restaurant patronage. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 2010, 51, 344–362.

- Hur, W. M., Kim, H., & Jang, J. H. The role of gender differences in the impact of CSR perceptions on corporate marketing outcomes. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2016, 23, 345–357.

- Jang, Y. J., Kim, W. G., & Lee, H. Y. Coffee shop consumers' emotional attachment and loyalty to green stores: The moderating role of green consciousness. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2015, 44, 146–156.

- Jeong, E., & Jang, S. Effects of restaurant green practices: Which practices are important and effective? 2010.

- Jones III, R. J., Reilly, T. M., Cox, M. Z., & Cole, B. M. Gender makes a difference: Investigating consumer purchasing behavior and attitudes toward corporate social responsibility policies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2017, 24, 133–144.

- Kim, D.-Y., Lehto, X., & Morrison, A. M. Gender differences in online travel information search: Implications for marketing communications on the internet. Tourism Management 2007, 28, 423–433.

- Kim, M., Yin, X., & Lee, G. The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2020, 88, 102520.

- Kim, S. B., & Kim, D. Y. The influence of corporate social responsibility, ability, reputation, and transparency on hotel customer loyalty in the US: a gender-based approach. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1–13.

- Martínez, P., Pérez, A., & Del Bosque, I. R. CSR influence on hotel brand image and loyalty. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración 2014, 27, 267–283.

- Melnyk, V., Van Osselaer, S. M., & Bijmolt, T. H. Are women more loyal customers than men? Gender differences in loyalty to firms and individual service providers. Journal of Marketing 2009, 73, 82–96.

- Nicolau, J. L., Stadlthanner, K. A., Andreu, L., & Font, X. Explaining the willingness of consumers to bring their own reusable coffee cups under the condition of monetary incentives. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 66, 102908.

- Nunnally, J. C. Psychometric Theory 2nd ed; Mcgraw hill book company, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R. L. Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of marketing 1999, 63, 33–44. [CrossRef]

- Palazon, M., & Delgado, E. (). The moderating role of price consciousness on the effectiveness of price discounts and premium promotions. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2009.

- Patino, A., Kaltcheva, V., Pitta, D., Sriram, V., & D. Winsor, R. How important are different socially responsible marketing practices? An exploratory study of gender, race, and income differences. Journal of consumer marketing 2014, 31, 2–12.

- Pawle, J., & Cooper, P. Measuring emotion—Lovemarks, the future beyond brands. Journal of advertising research 2006, 46, 38–48.

- Raza, A., Farrukh, M., Wang, G., Iqbal, M. K., & Farhan, M. Effects of hotels’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives on green consumer behavior: Investigating the roles of consumer engagement, positive emotions, and altruistic values. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 2023, 1–23.

- Roberts, K. In Lovemarks: The future beyond brands; Powerhouse books, 2005.

- Seeley, E. A., Gardner, W. L., Pennington, G., & Gabriel, S. Circle of friends or members of a group? Sex differences in relational and collective attachment to groups. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2003, 6, 251–263.

- Simakhajornboon, P., & Sirichodnisakorn, C. The effect of customer perception of CSR initiative on customer loyalty in the hotel industry. Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Studies 2022, 384–396.

- Song, H., Wang, J., & Han, H. Effect of image, satisfaction, trust, love, and respect on loyalty formation for name-brand coffee shops. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2019, 79, 50–59.

- Starbucks. Global Environmental & Social Impact Report. 2022. Available online: https://stories.starbucks.com/uploads/2022/04/Starbucks-2021-Global-Environmental-and-Social-Impact-Report-1.

- Sui, J. J., & Baloglu, S. The role of emotional commitment in relationship marketing: An empirical investigation of a loyalty model for casinos. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2003, 27, 470–489.

- Tajfel, H. E. Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations; Academic Press, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, P. H., Lin, G. Y., Zheng, Y. L., Chen, Y. C., Chen, P. Z., & Su, Z. C. Exploring the effect of Starbucks' green marketing on consumers' purchase decisions from consumers’ perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 56, 102162.

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management science 2000, 46, 186–204.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).