4. Discussion

Exploring the territory of shelter medicine and pet adoption unveils a complex interaction of medical, ethical, and social elements, providing a subtle perspective on how adoption preferences shape and are moulded by the principal narrative of animal welfare and human-animal relationships.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the knowledge towards pet adoption preferences among Portuguese residents in Portugal. Regarding data on the movement of animals in shelters, in Portugal, in 2022, 41,994 animals were collected from Portuguese streets to shelters, adding to those already there. Of all animals housed in Portuguese shelters, 24,721 were adopted, and 2378 were euthanised, representing an influx of 14,985 animals only in 2022 [

2]. However, the analysis of these data must be carried out carefully as it can easily lead to error by not accounting for deaths due to illness or other causes, as well as restitution to the legitimate owners and animals already living in shelters.

Given the overwhelming number of animals entering shelters annually in addition to those living there, comprehending these adoption preferences is a pressing need [

2]. Recognising these preferences can help shaping strategies to decrease shelter populations and, consequently, enhancing the welfare of many animals.

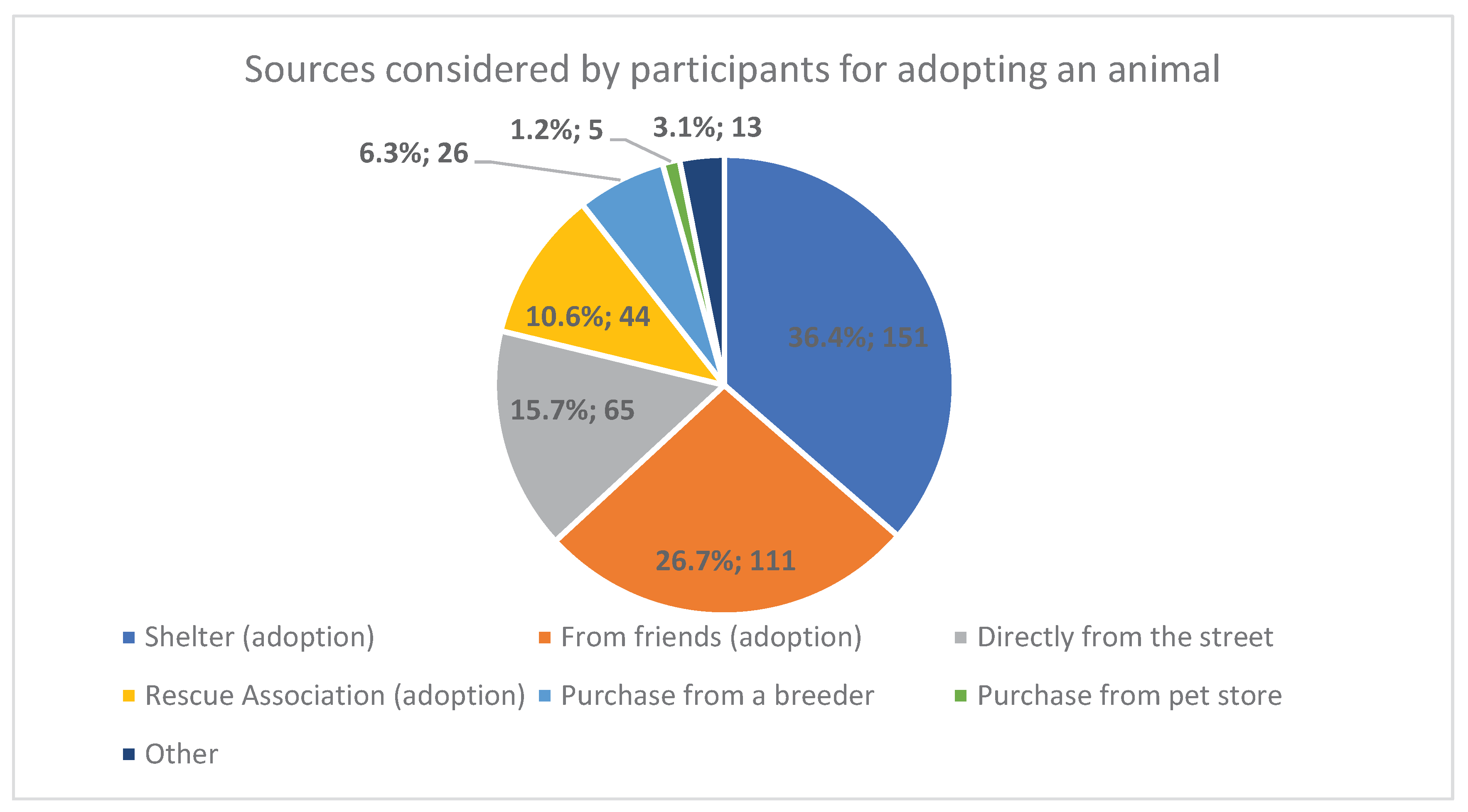

Pet acquisition has become a focal point of numerous studies, with the present study exploring the preferences of prospective pet owners, thereby revealing compelling patterns within pet acquisition sources. Strikingly, whilst 36.4% of respondents favoured adopting from a shelter, a substantial 84.6% confessed to never having adopted from one, with 52.8% never having visited one. This disparity between declared preference and prior action may unveil a complexity in attitudes and acquisition behaviours towards pets.

Many non-adopters are looking up but not planning to adopt when they visit a shelter or have no plans to adopt at all. Some plan to adopt but do not find what they want, especially a connection with the animal, and some did not plan to adopt when they visited the shelter but ended up adopting [

16]. Such discrepancy, for instance, can be paralleled to studies by Garrison & Weiss [

8], whereby, while shelter adoption was favoured, followed by acquisition from friends and breeders, a stark contradiction was visible in reference to surveys across 27 countries, wherein most pets were obtained from breeders (33.3%) or adopted from shelters/rehoming organisations (30.8%) [

17]. Searching deeper into the scope of stated preferences whilst weighing the reality of participants' acquisition behaviours becomes vital. A social desirability bias, as hinted at by Bir et al. [

18], might prompt answers that align with perceived social norms (adopting rather than purchasing), even if actual acquisition practices diverge from this norm, as verified by Garrison & Weiss [

8], with 60% indicating shelters as their preferred source, but with only 39% adopting from a shelter. Of notice is the importance of variety among shelter animals, with people (40%) willing to travel almost 100 km to acquire pets that meet their preferences and 46% would delay or wait for the decision for adoption if the shelter did not have the pet correspondent to their preferences [

8]. Moreover, our findings emphasise animal shelters and friends as prime sources for pet acquiring, aligning with previous research [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Specifically, the mere 6.3% admitting to purchasing from breeders underlines a growing inclination towards adopting or rescuing pets from shelters or other non-commercial sources [

23]. A deeper reflection on the nuances driving these preferences and behaviours can provide more robust insights and inform effective strategies for promoting shelter adoptions since there is a large margin of growth for the adoption of shelter animals given the demonstration of preference or consideration by adopters of this source over the others.

An intriguing point is the apparent disconnect between expressed preference for shelter adoption (36.4%) and previous no shelter visitation (52.8%) and no adoption from shelter behaviours (84.6%), as reported by others [

20,

21,

23,

24]. Garrison & Weiss [

8] discovered that 80% of dog owners acquired them from sources other than shelters despite most considered a shelter as the next source. Therefore, this manifestation of preference should be viewed with caution given that in another study a disconnection was noticed between what people said they would do and what they did, translated by 60% considering a shelter, but only 39% ending up acquiring a dog in a shelter [

25]. Similar results have already been reported in a survey conducted by the American Humane Association in 2012, with 56% considering a shelter but only 22% adopting a dog from a shelter. This disconnect is justified by people considering that shelters do not have the type of animal sought or people looking for pure breeds [

8].

What might be the perceived barrier that impedes shelter visits, even amongst those who prefer this source? It is also vital to ponder why a substantial percentage still acquires pets from friends or directly off the streets despite expressed preferences for shelter adoption.

The presented study evaluated the attributes prioritised by participants when adopting a pet from a shelter, revealing a distinctive preference for behaviour (52.8%), size (49.6%), and vaccination and deworming status (44.3%), alongside the age of the pet (36.1%). Curiously, breed (7.2%), sex (6.3%), and animal colour (5.1%) were the least prioritised. These results intriguingly contrast and partially align with existing literature, initiating a subtle exploration of potential adopter preference frameworks and the possible influences shaping them.

A divergence from the present study with Garrison & Weiss [

8] becomes apparent, who ranked importance as follows: source, age, size, risk of euthanasia, breed, origin, and colour. However, resemblances concerning the minimal importance accorded to breed and colour, and the substantial emphasis on age are observed. Another critical observation involves the considerable weight given to behavioural attributes in the decision-making process. This aligns with Weiss et al. [

7] findings that accentuated behaviour as crucial for cat adopters, in the way they approach and interact, and appearance being paramount for dog adopters, likely due to a wider variety of dog breeds. Although both attributes are important for both types of adopters. Even so, behaviour seems to play a greater role than phenotype since adopters attach greater importance to interaction with the animal.

Whilst previous literature has highlighted phenotype as a determinant in adoption choices [

7,

8,

26,

27], our findings bring out a nuanced perspective, suggesting behaviour surpasses phenotype in the adoption process [

7]. Despite the fact that most of our respondents had dogs (49.2%), we found no evidence to corroborate that adopters might be further influenced by phenotypic characteristics and history than animal behaviour, as Protopopova et al. [

26] suggested. This dichotomy deserves deeper exploration into how various factors, including the potential adopter experience and existing pet ownership status, may be shaping these preferences. For example, the observed associations – higher education with a preference for behaviour and microchipped, consistent with Brown et al. [

28], secondary education and having dogs aligning with a preference for vaccinated and dewormed animals and owning cats correlating with valuing an animal’s history – lend weight to the hypothesis that existing interactions and experiences with pets shape future adoption preferences. Moreover, despite the notable importance of size, this factor appears to be contextually contingent, with divergent results recorded across various studies. For instance, while our results indicate a general preference for smaller sizes, Siettou et al. [

11] and Garrison & Weiss [

8] exhibited a more neutral position towards size, emphasising the non-uniformity in preference matrices across different adopter demographics and geographic locations. Additionally, our findings corroborate the significance of the pet behavioural attributes in adoption, analogous to numerous studies affirming the role of personality, temperament, and interaction in the adopter’s choices [

7,

11,

29]. Cain et al. [

9] indicated certain physical attributes, like being a non-brachycephalic puppy, coupled with a smaller size, potentially enhance adoption likelihood, especially under extended shelter stays, aligning with our findings. Concurrently, certain physical attributes such as colour and coat have been recorded as influential in adoption success in other contexts [

13].

An imperative dialogue emerges regarding the relevance of age in adoption choices. Our results discern an association between a lack of cat ownership and an age preference. At the same time, both our findings and those of Garrison & Weiss [

8] indicate age as a critical determinant in adoption choices. Interestingly, Siettou et al. [

11] highlight the inverse relationship of age-adoption probability, underscoring adopter preferences' complexity and multidimensionality.

It is crucial to acknowledge that while specific attributes like colour, sex, and LOS in shelters may be minimally impactful in isolation [

26], their cumulative interaction with other factors could shape adoption outcomes. Consequently, it is prudent to examine attribute interplay rather than isolating them since no single attribute seems to drive the decision-making process of adoption [

8].

Our study corroborates Cohen & Todd [

30], underscoring a general trend towards valuing behaviour over physical attributes. However, certain physical traits, such as skull type and predicted adult size, could influence adoption more than breed or breed group [

9]. However, according to Siettou et al. [

11], the classification of a dog as a purebred increases its chance of being adopted. The attribute "sex" was selected by 6.3% of participants as crucial in our study, positioning it as one of the less critical factors in the adoption decision process. In stark contrast, Cohen & Todd [

30] indicated a considerably higher valuation of an animal’s sex at 36%, revealing a noteworthy disparity in the importance attributed to sex between different study contexts and suggesting potential variations in adopter prioritisation that diverse demographic or cultural factors might influence. Brown & Morgan [

31] discovered that male cats and kittens experienced shorter LOS than their female counterparts. However, when investigating the preferences of adopters, Onodera et al. (2014) found that sex was the third most crucial factor in cat adoption choices, with over half of adopters showing a preference for female cats. Conversely, Janke et al. [

32] observed in another study that male cats appeared more readily adopted than females.

Contemplating the nuanced consistency and variability amongst our findings and existing literature, future investigations might benefit from a multifaceted approach, exploring the synergistic interplay of adopter demographics, geographical/cultural contexts, and specific animal attributes in shaping adoption preferences.

This study also identified the most common response combinations among the three most important factors participants chose (

Table 3). The four most chosen combinations were “Vaccinated and dewormed, Identified (microchip) and registered, Sterilized or will be for free”, “Size, Animal history, Behaviour”, “Size, Age, Behaviour”, and “Size, Vaccinated and Dewormed, Behaviour”. Predominantly, health conditions, including "Vaccinated and Dewormed", "Identified (microchip) and registered", and "Sterilized or will be for free", were highly favoured by respondents, echoing findings from previous research [

7,

21,

28]. Clevenger and Kass [

33] support this with a noted elevation in adoption rates linked to pre-adoption neutering, albeit contrasted by Janke et al. [

32], who found neuter status insignificant in influencing adoption rates.

In another study, age and source were the two attributes with the most influence over choice [

8], with puppy and animal shelter being the most positive features and senior and pet store the most negative features.

Moreover, response combinations that included "Size", "Animal History", and "Behaviour" also emerged as crucial within the decision-making process, corroborating earlier studies highlighting the influence of physical and behavioural traits on adoption [

11]. Though age was only present in one of the top 10 response combinations, it might be perceived as a secondary consideration compared to behaviour and size, aligning with findings that downplay its significance in adoption decisions [

21].

In the study by Garrison and Weiss [

8], a medium-sized, dark-coloured, rare/unusual breed puppy with a high risk of euthanasia from the local community was the most popular profile, our study found no clear preference for any particular breed, colour, or size. Conversely, the least popular profile in that study was a large, brown-coloured, mixed-breed senior dog transported from out of state with no risk of euthanasia and obtained from a pet store.

A noteworthy 65.3% of participant preference towards dog adoption over cats (34.7%) aligns with prior research [

7,

8,

11], potentially underscoring a partiality for adopting familiar or previously owned animals [

10,

12]. Since most of those who preferred to adopt dogs were already dog owners (

p < 0.001), and most of those who preferred to adopt cats were already cat owners as well (

p < 0.001).

Higher-educated participants showcasing a tendency towards dog adoption, hinting at a potential correlation between education level and adoption choices. This connection was observed in prior studies [

28].

The results spotlight several vital factors influencing shelter pet adoption, providing further evidence that adopters consider multiple factors when adopting and that those have different weights in the complex matrix of preferences in adoption decisions.

The present investigation reveals a notable indifference toward breed selection in the animal adoption process, with 83.9% of participants expressing no breed preference. This aligns with Kwan & Bain [

34], underscoring that breed often takes a backseat to other influential factors during adoption [

34]. A mere 10.6% preferred a defined breed and 0.2% a purebred, similarly to Cohen & Todd [

30], who found that mixed breed was preferred over pure breed (79% versus 21%, respectively), suggesting the breed may often be a subordinate factor in adoption decisions. Interestingly, cat adopters were even less concerned with breed, possibly due to a more limited aesthetic variance among cats than dogs [

7].

Despite this, breed does not entirely escape consideration. The breed of both dogs and cats has been shown to influence adoption rates and LOS in shelters, particularly in purebred dogs [

11,

13,

29,

31,

32,

35,

36,

37]. Contrarily, certain breeds or physical characteristics, such as brachycephalic dogs, tend to experience lower adaptability [

9], while exotic cat breeds might be adopted sooner than their native counterparts [

31,

32]. Breed-related stereotypes and public perception also play a role, potentially affecting adoption success variably for certain breed types [

13,

26,

35,

38]. Specifically, dogs resembling fighting breeds or those labelled as “blockhead” dogs could experience lowered adoption rates due to ingrained public perceptions [

9,

39] in a way that breeds misidentification can penalise adoptability [

40] and this is a more problematic cause as even trained shelter professionals are unlikely to accurately characterise solely based on animal phenotype [

38], suggesting that adoption success relies on public perception of the different breed types more than to phenotype and breed identification. Likewise, the intake mode, such as whether the pet was stray, confiscated or surrendered, influences adoption success and LOS, possibly due to prevailing public attitudes toward these categories [

26,

41].

Cain et al. [

9] suggested that skull type, predicted adult size or coat length might be more predictive of outcome than breed alone. While the data implies that breed might be less critical, the intricate interaction between breed, physical characteristics, and public perception in adoption decision-making cannot be ignored. Further exploration is requisite to fully comprehend these dynamics and discern strategies to improve potential negative implications for certain breeds or physical types in adoption contexts.

Participant attitudes towards animal colour and fur type in adoption decisions manifest intriguing patterns. An extensive majority displayed indifference towards the colour of adoptable animals (85.8%), while only 9.9% leaned towards light-coloured, 4.1% towards dark-coloured animals, and only one participant expressed a preference for grey colour (0.2%). This (

Table 3) aligns with existing research where colour tends to be a secondary consideration in adoption, often eclipsed by behavioural, size, and health considerations [

11,

27]. However, some studies exhibit varying data, suggesting that dogs with black or brindle coats might experience longer LOS and diminished adoption rates [

35], whereas lighter coats can potentially expedite adoption [

13,

35,

41]. Conversely, Cohen & Todd [

30] found a preference for medium colours (light brown, red) followed by dark colours (black and dark brown) and light colours (white, grey, tan), further complicating the relationship between colour and adoption likelihood. Protopopova et al. [

26] suggested that adopters may prefer unique colourations with varying preferences across different regions instead of being attracted to a specific colour. However, Brown et al. [

28] reported that coat colour does not affect the LOS in shelters. Furthermore, in the jurisdiction of cat adoptions, Brown & Morgan [

31] indicated that yellow-coloured cats had longer LOS but concluded that coat colour does not affect cat adoptability. Some noted prolonged adoption durations for black cats, corroborating the notable "black cat syndrome" [

32,

42], though other research studies have suggested white cats, followed by brown, grey and orange cats, more readily adopted than dark cats [

43]. Also, those authors did not find improved outcomes during the month before Halloween, a phenomenon called “black cat bias”.

Regarding fur type, 63.1% (n = 262) of participants demonstrate indifference. Among those with preferences, 24.1% (n = 100) favoured short-haired animals, with only 2.4% (n = 10) leaning towards long-haired varieties. Such tendencies align with Weiss et al. [

7], who documented a leaning towards short-haired dog adoption. Nevertheless, fur length occasionally lacks a significant impact on adoption decisions [

44,

45], with occasional disparities, such as Siettou et al. [

11], highlighting a positive association between coat length and adoptability. Our findings insights illuminate that while physical attributes like colour and fur type can influence adoption (

Table 3), substantial portions of adopters prioritise other factors like behaviour and personality over physical characteristics [

7,

11,

26,

27]. Nonetheless, the nuances within existing research underscore a necessity for further exploration, potentially elucidating varied preferences across different regions and demographic segments [

26] and thereby refining strategic approaches for animal shelters to optimise adoption strategies and animal welfare. Consequently, integrating and understanding these varied findings and their applicability is crucial to strategically addressing adoption disparities and enhancing shelter outcomes.

A detailed look at adopter preferences for animal size reveals intriguing patterns and confirms previous findings in research. In the current study, a sizable group of participants, 28.4%, expressed no definitive preference regarding animal size for adoption. However, a distinct inclination towards smaller animals is evident, with 33.3% preferring small and 30.4% medium-sized animals. Only 8.0% leaned towards adopting larger animals. These findings mirror existing research, substantiating the recurrent theme of smaller animals typically experiencing higher adoption rates and shorter LOS [

11,

13,

26,

28]. Intriguingly, Cain et al. (2020) discovered a temporal shift in size preference, wherein small to medium-sized dogs initially enjoy higher adoption rates compared to larger counterparts, yet this advantage decreases over extended LOS. Conversely, Cohen & Todd [

9,

30] outlined a preference for medium-sized animals (59%) over small (34%) and large (33%) counterparts, hinting at potential variations in preferences within different demographic or geographic contexts and underlining the delicate complexity of adopter size preferences. The observed preference for smaller animals may originate from pragmatic considerations, such as residential space limitations or ease of management, particularly in urban living contexts [

9]. Adopters potentially perceive smaller animals as more manageable, requiring fewer resources and being more adaptable to various living situations. In summary, while a significant inclination towards smaller animals in adoption preferences persists in general trends, divergences in data suggest potential influences from regional or demographic variables. Continuous research and localised studies are imperative to navigate the complex network of factors influencing adoption preferences, facilitating refined strategies to sustain adoption rates across all size categories in animal shelters. A strategic approach informed by a nuanced understanding of size preferences could increase adoption efforts and improve animal welfare outcomes across diverse sizes.

The connexion of age preference and adoption rates of animals deserves a detailed exploration. In the presented study, the age preferences were notably varied. This age preference merges with existing literature indicating a pronounced inclination towards younger animals among adopters [

9,

26,

30,

31]. For instance, Cain et al. [

9] discerned that puppies experienced a higher adoption likelihood than adult dogs, albeit witnessing a reduction as the LOS in shelters increased. Meanwhile, senior dogs initially encountered lower adoption probabilities that improved with extended LOS. Notably, after a LOS of 50 and 80 days, their adoption probabilities matched and surpassed those of adults, respectively. This is probably due to adopters or rescue groups specifically seeking out senior dogs or shelters promoting their adoption. Intriguingly, seniors aged 8 years and above demonstrated slightly higher adoptability than their 5-7-year-old counterparts in a study by Siettou et al. [

11], and in a context involving geriatric dogs, health condition was a pivotal determinant in adoptability, notwithstanding an average LOS of 89 days [

46].

The dominant preference for younger animals could be partly elucidated by the “Kindchenschema”/baby schema effect, wherein juvenile mammals generate an intrinsic disposition to nurture in humans [

47,

48]. This phenomenon manifested even in children as young as 3 years, may potentiate the attraction of pets that embody neotenous (youthful) attributes and behaviours, fostering our desire to care for them [

49,

50].

Intriguingly, the human-animal dynamic extends beyond age to encompass behaviour, with some research implying that adopters might be more swayed by explicit prosocial behaviours in animals, such as rubbing, rather than subtle facial expressions in domestic cats [

51]. Moreover, cat behaviours like slow blinking, which humans might interpret as a positive signal, as it shares certain features with the Duchenne smile (the one that reaches the eyes) in humans, as well as reaction to positive emotional contexts in other mammals, can also significantly impact adoption likelihood [

52,

53].

In a broader context, the dichotomy of prevalent preference for youthful pets versus the emergent, although modest, traction for older animals with extended LOS illustrates a multifaceted panorama. Over time, the incremental adoptability of older pets might be fuelled by specific adoption campaigns, rescue group initiatives or adopter demographics expressly seeking mature or senior animals. This intricate matrix of preferences and influences highlights animal shelters need to employ subtle, strategic approaches in promotion and adoption facilitation. Understanding oscillations of age preference informs effective shelter strategies and empowers initiatives to elevate the visibility and adoptability of often-overlooked, such as senior animals. Thus, shelters can holistically provide to the varied preferences of potential adopters, thereby optimising adoption rates across all age categories and ensuring improved welfare outcomes for animals irrespective of age.

Length of stay (LOS) within animal shelters emerged as a layered determinant in adoption, linking with factors like age and perceived animal characteristics. The current study, which underscores that a considerable 68.9% of participants were indifferent towards LOS during adoption, aligns with findings by Patronek et al. [

21], where LOS was not a pivotal criterion for adopters. In contrast, 18.3% and 12.8% preferred recently housed animals and those with prolonged shelter stays, respectively. This bifurcation in preference, especially favouring newer shelter entrants, diverges from Weiss et al. (2012), wherein adopters leaned towards animals with shorter LOS.

Cain et al. [

9] explored the evolving dynamics of adoption probabilities as LOS extends, observing a mutable impact of age, predicted adult size and skull type on adoption likelihoods with increased LOS, implying that the influence of phenotype changes. This comprehensive understanding is particularly intriguing when observing the adoption trajectories of puppies. While their initial adoption probabilities are notably high, an extended LOS diminishes this likelihood, even though puppies generally experience shorter LOS than older counterparts [

8,

28,

29,

35,

39,54]. Interestingly, Siettou et al. [

11] found older dogs (over 8 years) marginally more adoptable than adults, adding another dimension to the discourse on age, LOS, and adoptability.

For cats, a similar age-LOS-adoptability dynamic unfolds. Younger cats typically see higher adoption rates than older ones [

31], and prolonged LOS generally attenuates adoptability [

9]. Contrarily, Janke et al. [

32] noted adult cats have higher adoption rates than kittens, albeit with an acknowledgement of methodological considerations influencing such outcomes. Additionally, cat colouration and breed have been observed to impact LOS and, by extension, adoptability [

31]. The contrasting studies insinuate that while LOS, age and other factors are discernible in their impacts on adoption, their interplay can be modulated by diverse contexts and demographics within and across shelters. It might imply that factors such as shelter practices, local culture, community outreach, and marketing efforts potentially contour these adoption backgrounds and modulate the influences of age and LOS.

Understanding this complexity and variability necessitates animal shelters to adopt a flexible, adaptive approach to animal promotion and adopter engagement. Adapting interventions to the general and specific trends of adopter preferences, punctuated with thoughtful marketing and community engagement, may holistically enhance adoption outcomes across varying LOS and age groups. Further, incorporating strategic interventions for traditionally overlooked animals – such as older pets or those with extended LOS – might amplify their visibility and adoptability and enlighten potential adopters about the joys and merits of adopting these often-undervalued animals.

A thoughtful amalgamation of generalised trends, local nuances and adaptive strategies can facilitate a holistic, inclusive approach to animal adoption, ensuring every animal finds a loving, permanent home. Studies investigating the factors that affect adopter choice reveal the broad range of attributes that individuals consider when adopting. Furthermore, these attributes have numerous variations, such as behaviour, age, size, health, and sterilisation status, among many others. Variations in regional factors such as the population of stray animals, temperature and their survival, legislation regarding stray animals, spay-neuter requirements, leash laws, strictness of pet ownership laws, socioeconomic factors, culture, predominant breeds and phenotypes may impact adoption rates [

9,55]. While attributes such as behaviour, age, and size emerge as predominant factors influencing adoption from shelters, it is crucial to approach these findings with a knowledge of the intricate, multifaceted web of influences shaped by the potential adopters’ demographic and experiential backgrounds. Consequently, future research exploring these complex interrelations promises to be a fertile ground for enhancing understanding and optimising adoption practices across various contexts.

Our results demonstrate that people have complex adoption frames of preferences as described by Garrison and Weiss [

8], showing that individuals have varying preferences, indicating that diversity is present even in this aspect of pet adoption, which may be better matched if there is variety in the animals at the shelter. So, the authors suggest a comprehensive animal relocation program to increase the variety in shelters and thus better meet the requirements of adopters [

8]. Overall, the results of this study provide further insight into the factors that influence adoption decisions and suggest that education level and previous pet ownership experience may be important factors to consider. These findings can inform animal shelters and adoption agencies about the attributes that potential adopters consider important and may help them better match animals with suitable homes. Another limitation of our study is not having analysed the existence of correspondence or dissonance – the “state-revealed preference gap” – between the preferences established by the Portuguese and the characteristics of the animals effectively adopted [

30].

Study limitations

As per our previous discussion, some limitations of the study need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the study may have a narrow focus on specific attributes, which may impact the generalizability of the results. Secondly, there appears to be a discrepancy between the findings of this study and those of others, which could be due to methodological inconsistencies. Furthermore, the results may only apply to some populations or cultural settings. The study may also be affected by selection biases related to participant recruitment. Lastly, it is worth noticing that there could be temporal and regional preferences that were not considered, which may affect the results. It is important to admitting that the sample used for the study may not be fully representative of the general population and that the study only provides a snapshot of preferences among a specific population at a specific time.