Several peripheral rural micro-regions have experienced a decline in the recent past. In these cases, economic, demographic, social and environmental aspects have typically been involved. Most of these micro-regions are located on the border between the spheres of influence of regional centres, be it the border between administrative units or the area on the state border. The declines have frequently been accompanied by poor accessibility, a lack of natural resources or even a complex historical path.

These problems are well known and have an extensive amount of literature concerning them. The issue with the political solution in this context is that the countryside is perceived from the centre as a unified space. The political approach tends to focus on the countryside as a whole when considering problems and suggesting solutions. In addition, the emphasis of the EU Common Agricultural Policy is still on supporting agriculture, even though the European countryside is no longer dependent on this sector.

In addition, research on the Czech borderland in relation to historical development was almost taboo during the socialist period, and after 1989 it seemed that after half a century and several changes in political regimes, historical events had little influence on the present. Our ambition is to show that historical development at least since the beginning of modern society (in Czech conditions from the middle of the nineteenth century) must still be taken into account.

Many rural studies have been influenced by the nostalgic notion of the rural idyll [

1]. As it is unclear which period this idyll relates to, it is necessary to discuss the current countryside, rather than possibilities of a return to the past. The current European countryside is in the process of transition to a post-productive period, which is gradually changing the countryside from an area for agricultural and forestry production to a consumption territory for recreation and housing. One-sided productive orientation is substituted with multifunctionality [

2].

The decline of rural regions has been linked by some authors to the loss of jobs in agriculture [

3]. Thus, increasing agricultural employment has been suggested as a means of generating improvement [

4]. This solution is much more likely to work in the context of less-developed countries. In developed European countries, reducing job numbers may not play a decisive role in rural decline. Work is no longer the only reason behind migration; in fact, it may not even be the main reason. Rural to urban migration was typical when the standard of living in cities was significantly higher than in rural areas. However, due to stress phenomena in cities and the development of rural infrastructure, the countryside represents an attractive alternative environment for many inhabitants. Therefore, there are strong urban to rural migration flows. Only rural areas with a concentration of negative conditions remain in decline.

Therefore, it is necessary to focus on truly endangered rural microregions, which, in competition with other territories, are usually less likely to succeed in obtaining external assistance. However, researchers have rarely studied the genesis of micro-regional declines or their specific causes and interconnectedness. Therefore, we have focused on a micro-region that has gradually been affected by a set of natural, economic, political and demographic problems and disasters. The Vejprty area on the Bohemian – Saxon border was chosen as a case study. Our ambition is to show how changes in conditions have caused an almost total decline and how further changes can raise some hope for positive development.

1. Introduction: Declining rural regions in the context of contemporary history

Rural decline is an inevitable process as human society transitions from an agrarian to an urban industrial society before finally becoming a knowledge society. Some authors drew attention to the influence of the external environment and held that the basic issue is the resilience of rural micro-regions to external influences [

5]. In our current world, depopulation reflects a complex interplay of chronic net out-migration and natural decrease rooted in the past [

6]. Depopulation is not only a result of persistent outmigration; it also reflects large effects expressed in declining fertility and rising mortality (due to aging).

In the case studied, the population density has declined to the extent that we can speak of sparsely populated areas, which are particularly common in Scandinavia. In the European Union, they join mountain areas or smaller islands and are the subject of targeted support [

7]. Le Tourneau considered such areas to be a specific geographical phenomenon to which specific approaches should be applied [

8].

Some authors have searched for solutions in the mobilisation of human and social capital [

9]. This is certainly not a rare case, as the most successful and ambitious people usually leave the peripheral regions first [

10]. One strategy could be innovation towards intelligent shrinking. Due to the shortcomings of internal human resources, the longer-term involvement of external experts is an option [

11]. However, this could be at odds with the search for exogenous sources and bottom-up approaches promoted in the LEADER programme (a EU initiative to support rural development projects initiated at the local level in order to revitalise rural areas and create jobs.).

In our paper, we try to map the path of one of the declining rural micro-regions during the last century. The pre-industrial countryside was characterised by low labour productivity and feudal social relations. Prosperity in this case depended mainly on natural conditions. The policy measures were implemented on a local and regional scale [

12]. In the first phase of the industrial society, the Industrial Revolution gradually brought industrial technology and market relations to the countryside. Urban growth drained the rural population, but the parallel demographic revolution meant that the rural population had not yet declined. The creation of a civic society was associated with nation states and the growth of nationalism, which also penetrated the countryside. In addition to natural conditions, the issues of location (like diffusion of innovation, access to markets, possibilities to commute) and national policies also became important [compare with 13].

The uncontrollable development of capitalism in the twentieth century led to two world wars (with the consequences of the second including the partitioning of Europe by the Iron Curtain) and a world economic crisis in the 1930s. The main question concerning the remote countryside has become its resilience to turbulent changes [

14]. With the development of production and transport technologies, rural development began to be gradually separated from agricultural development. The countryside started to be significantly differentiated according to the urban/rural divide. Individual types of the countryside had significantly different conditions and, thus, separate paths of development. The second demographic transition in relation to the persistence of rural to urban migration, in addition to the reduction of the rural population, caused depopulation [

15].

The post-industrial neoliberal countryside has turned our attention to diversified consumption [

16,

17]. Agricultural policy is managed from the European level [

18] and is focused more on landscape maintenance and multifunctional agriculture [

19]. The quality of the rural landscape is significant for tourism [

20] and for the lives of those working in cities or at home for remote companies. This circumstance overshadows the importance of some characteristics of rural development. Insufficient economic development often means greater preservation of natural values [

21]. Remoteness can mean a quiet environment. However, the consumer society has to face other challenges, such as growing social disparities, environmental limits and the depletion of natural resources.

2. The area and methods of the study

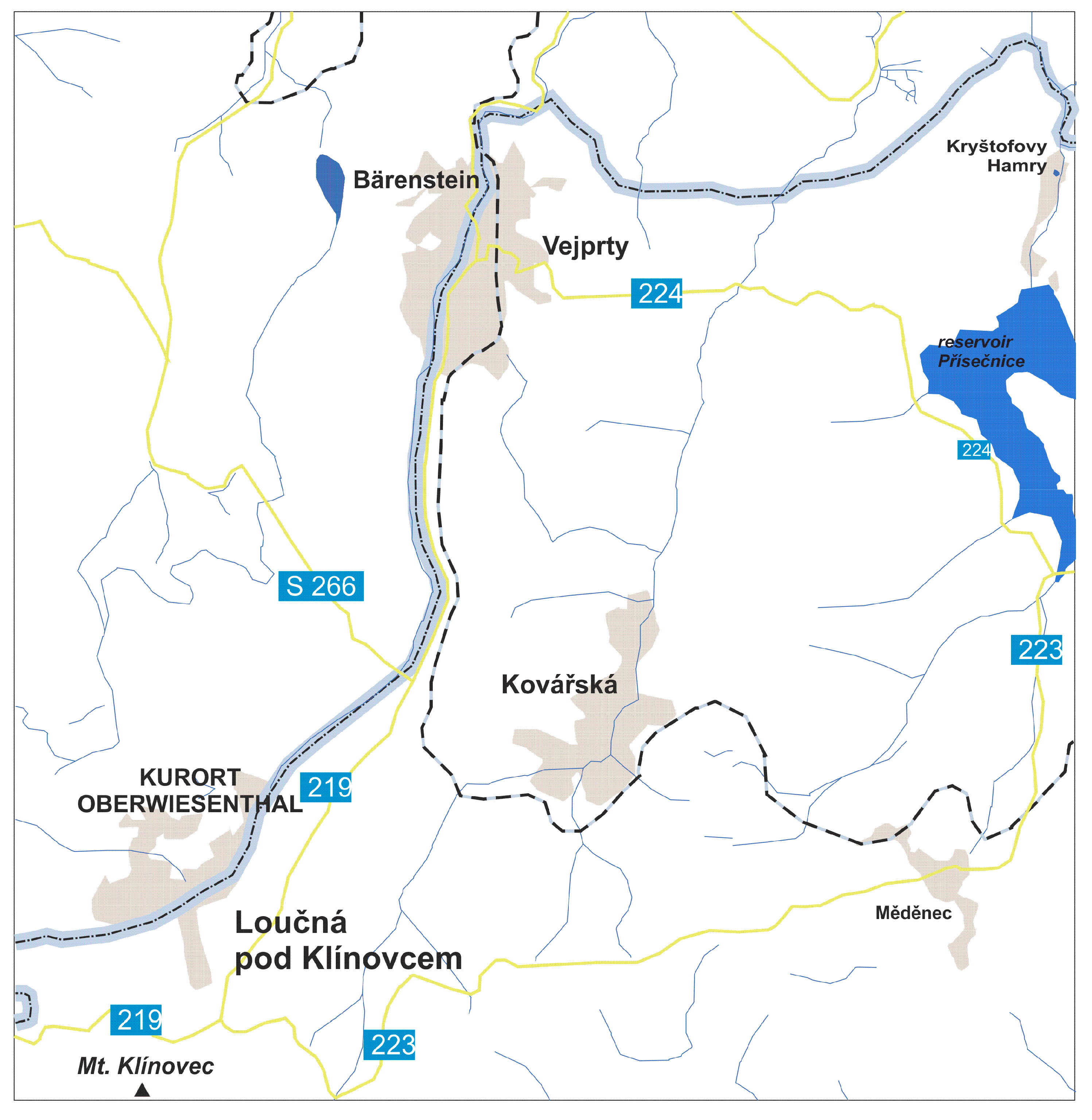

The region under study is defined by the area of the authorised municipal office Vejprty. (Due to the large number of very small municipalities in the Czech Republic, intermediate stages have been created between municipal and regional authorities - authorized municipal authorities and municipal authorities with extended competences, which provide state administration operations for small municipalities in their vicinity. These circuits do not have a self-governing function). The area is situated about 800 m a.s.l. in a peripheral position on the border with Saxony, which is formed by the stream Polava (Pollau). It is open to Saxony and separated from the Bohemian hinterland by the ridges of the Ore Mountains. The area has relatively dramatic climatic conditions and little fertile soil, with 68% of the territory covered by forests and 23% by permanent grasslands.

Unless otherwise stated, statistical data and data on the studied region come from the public database of the Czech Statistical Office, Prague. The settlement consists of the small town of Vejprty, the large village of Kovářská and 13 other villages, 12 of which have fewer than 100 inhabitants. The population density is 32 people per km2, meaning the micro-region is among the most sparsely populated areas in Czechia. The economy of the territory is problematic. In regard to agriculture (perhaps with the exception of extensive cattle breeding), the conditions needed for agriculture were never met. Mining in the area ceased a long time ago; moreover, most of the light industries have disappeared. None of the conditions needed for the development of progressive industries are satisfied. However, some hope for the future can be seen in the development of tourism.

Figure 1.

General situation of the area under study. Source: own drawing.

Figure 1.

General situation of the area under study. Source: own drawing.

A combination of geographical and historical methods was used to analyse post-war development. For the former, statistical data and field research were utilised, while methods of contemporary history (mainly involving the use of archival documents or the extraction of witnesses) served as the basis for the latter. A common problem with both approaches is the complete lack of secondary sources of a professional nature from other researchers. In the recent past, the territory of Vejprty and its surroundings have received little attention from political bodies and researchers.

As for the authors, they have previously dealt with this micro-region in their studies of the Czech borderland investigating the area as one of several case studies [

21]. Some interest from abroad (particularly from Germany) has also been noted [

22,

23].

3. Results

3.1. Historical background

Due to the harsh climatic conditions, the Vejprty area was settled late. The first settlement likely originated on the trade route from Leipzig to the Bohemian hinterland. The origin of the town of Vejprty itself was the hammer mill on the Polava stream. More intensive settlements developed only in connection with ore mining in the sixteenth century. The area was particularly colonised by the Germans from Saxony, who were considered to be mining experts. After the mines were depleted, the locals focused on the production of lace, braids and rifles. In 1872, a railway line was opened from Chomutov to Chemnitz via Vejprty, which was an impetus for the further development of industry. As a developing industrial city, Vejprty became a refuge for many inhabitants of the northern borderland who lost their local jobs. This has led not only to population growth, but also to a significant increase in social disparities.

The Germans from Vejprty did not accept the establishment of Czechoslovakia in 2018. However, their attempts to declare Deutschböhmen as a province of the Republic of German Austria, proclaimed in Vienna on November 12, 1918, could not be successful in view of the results of the WWII. Nevertheless, this led to mistrust between the central government and the local population. After a certain period of stabilisation, the Nazi ideology began to manifest itself. This took advantage of the consequences of the economic crisis, to which the local industrial structure reacted worse than the inland. Although there were strong anti-Nazi tendencies among the local Germans, armed clashes between the state authorities and the fighters of the Sudeten German Party intensified.

From 1938 to 1945, the territory was part of the Sudeten German County of Germany. The great expectations that had arisen from joining Germany were not fulfilled. After the war, most of the population was deported to Germany as part of a wild evacuation, then followed by organised deportation. However, about 2.5 thousand Germans remained or were moved here from other border areas with the presupposition of their engagement in uranium mining in neighbouring Jáchymov [

25]. Half the amount of the area originally inhabited was expected to be populated as it was assumed that unfavourable localisation conditions could not ensure prosperity for the original population numbers. However, re-settlement was very slow, and the assumptions were never met.

The economy suffered from the location being remote and the shortage of skilled workers. In contrast, the forces associated with the army and the protection of the state border were strengthened. The development of the area was influenced by the construction of the Přísečnice waterworks in the 1970s, which resulted in the liquidation of the town of Přísečnice and the surrounding villages.

Changes after 1990 dealt further blows to Vejprty and its surroundings. Some of the remaining branch offices of industrial enterprises disappeared. The army and border police left. Redistribution, which provided a comparable standard of living to less-developed areas during the socialist era, was curtailed. Hopes for cooperation with Saxon cities have only partially been fulfilled, mainly due to the fact that the ex-DDR regions are also in a difficult economic situation.

Vejprty naturally belongs to Karlovy Vary as a district and regional centre. However, administrative reforms assigned Kadaň as a municipal office with extended competences, Chomutov as the centre of the district and Ústí nad Labem as the regional centre. These towns are not only further from Vejprty, but also separated by mountain ridges. The Saxon resorts of Annaberg-Buchholz and Chemnitz are also much better accessible. Thus, the Vejprty area administratively falls under different centres that it inclines naturally.

3.2. Economic development

The economy of Vejprty has undergone significant changes. Originally a poor mountain region unsuitable for agriculture, it became rich from ore mining, particularly from silver. After extracting silver, it switched to light industry, mainly demanding the production of handicrafts. The peripheral border location and transport remoteness did not allow for the development of heavy industry. Political developments in the middle of the last century significantly transformed the industrial structure, which did not fit into the model of the centrally controlled economy or the CMEA economy.

After the liberation in 1945, the Vejprty area was deindustrialised. Three mountain pastoral cooperatives were established in Měděnec, Kovářská and Rusová. Surviving businesses were incorporated into larger units (settled out of the area under study, which often led to their later demise). Many craft workshops disappeared along with the expulsion of the German population. Consideration was given to restoring the mining tradition in connection with the Jáchymov uranium mines, hence why some non-displaced Germans were directed here. However, a housing estate for uranium miners was eventually built in Ostrov nad Ohří. Instead of the defunct factories, a branch of the clothing company TOSTA Aš and the production of musical instruments in AMATI Kraslice were established. The armed forces have become an important factor in the economy.

Even after 1990, the decline of the industry continued. The branches of TOSTA and AMATI were closed. The low quality of human capital does not allow for the development of a progressive sector of the knowledge economy. Textile production was taken over by the Tricita Fashion company, the paper production by Linx is maintained, Koster produces accessories for the automotive industry, the K + M company renovates old furniture, Belet is engaged in the production of handling equipment and Setja is concerned with industrial bending of pipes and wires.

The services represented in the first phase by Vietnamese shops and markets near the state border began to develop, such as in Vejprty and Loučná pod Klínovcem. The abolition of the military garrison and hospital in 1999 had a negative impact. On the other side, some social service facilities are located in Vejprty. The official commuting of the population to work in Germany is negligible. In 2021, together 241 people participated. In the first phase, the Germans commuted to the Vejprty area for cheaper goods and services.

In 2021, 389 economic entities with detected activity were recorded in the microregion (one entity per 7.5 inhabitants). Many of these entities (114) operate in industry and construction, the field with the most activity. This is followed by trade and transport (59 entities), professional services (49 entities each) and accommodation and gastronomy service activities (39 entities).

Recently, tourism – focused on winter sports and hiking – has begun to develop. In 2022, there were 40 accommodation facilities in the microregion, with 469 rooms and 1,333 beds. They accommodated 22,149 guests, who spent 62,514 nights here (of it 23% of foreigners). In the last pre-COVID season 2019, the number of overnight stays reached 72,750. Loučná pod Klínovcem has been recorded as having the most intensive tourism. In addition, there are 245 unoccupied apartments in the area, used for recreation. Holiday cottages are increasingly being offered for commercial use, especially in the immediate vicinity of Mt. Klínovec. Tourism in this micro-region is also helped by a well permeable border, which makes the infrastructure and attractions accessible on both sides (including ski resorts, historic railways and other amenities).

Adverse climatic conditions have been used to build a wind farm. Kryštofovy Hamry (owned by the German company Ecoenerg Windkraft) is the largest wind farm in Czechia, having 23 turbines and an output of 42 MW. The question is to what extent this facility contributes to the local economy.

3.3. Population development

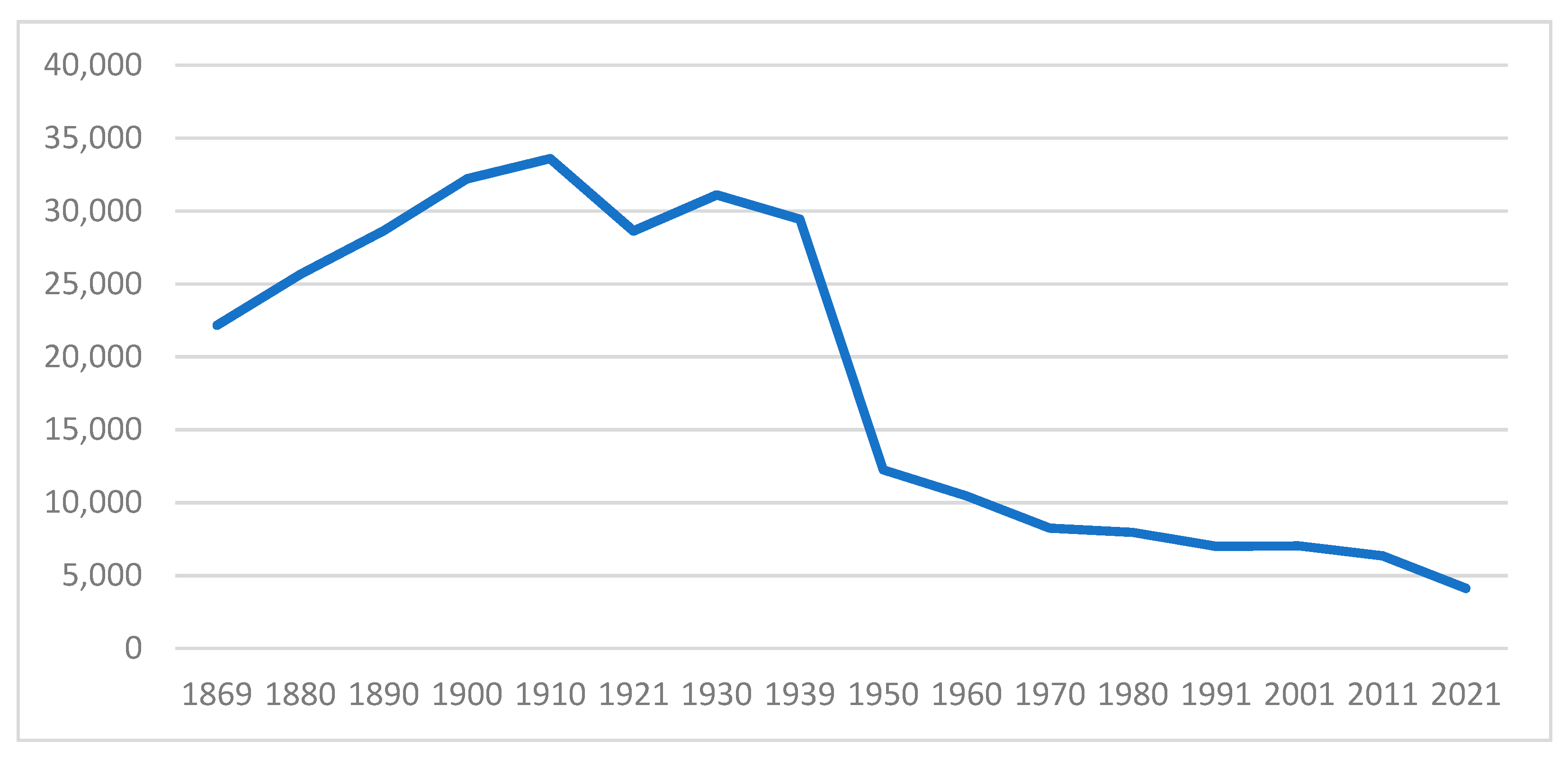

The development of the population since the first census in the Czech lands in 1869 can be seen in the

Figure 2. The area reached a population peak in 1910 (the last census before WWI). Originally, most of the population was located in the territory of today's Kryštofovy Hamry (10,427 people in 1900), which, however, consisted of a number of villages. Approximately 5,000 inhabitants resided in the area of today's Mezilesí with the settlements of Přísečnice and Dolina. At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, other settlements in the territory also had remarkable numbers of inhabitants, such as Kovářská (4,400 inhabitants in 1910) and Rusová (3,500 in 1900). In 1910, Vejprty became the largest city in its microregion (10,700 inhabitants). After WWI, the population of the area had decreased by 15.7% due to war losses and other causes before beginning to grow again. In 1930, the largest seat of the micro-region was held by Vejprty (11,800 inhabitants), followed by Kovářská (4,300 inhabitants), Mezilesí (3,500), Přísečnice (2,600), Rusová (2,000) and Loučná (1,400).

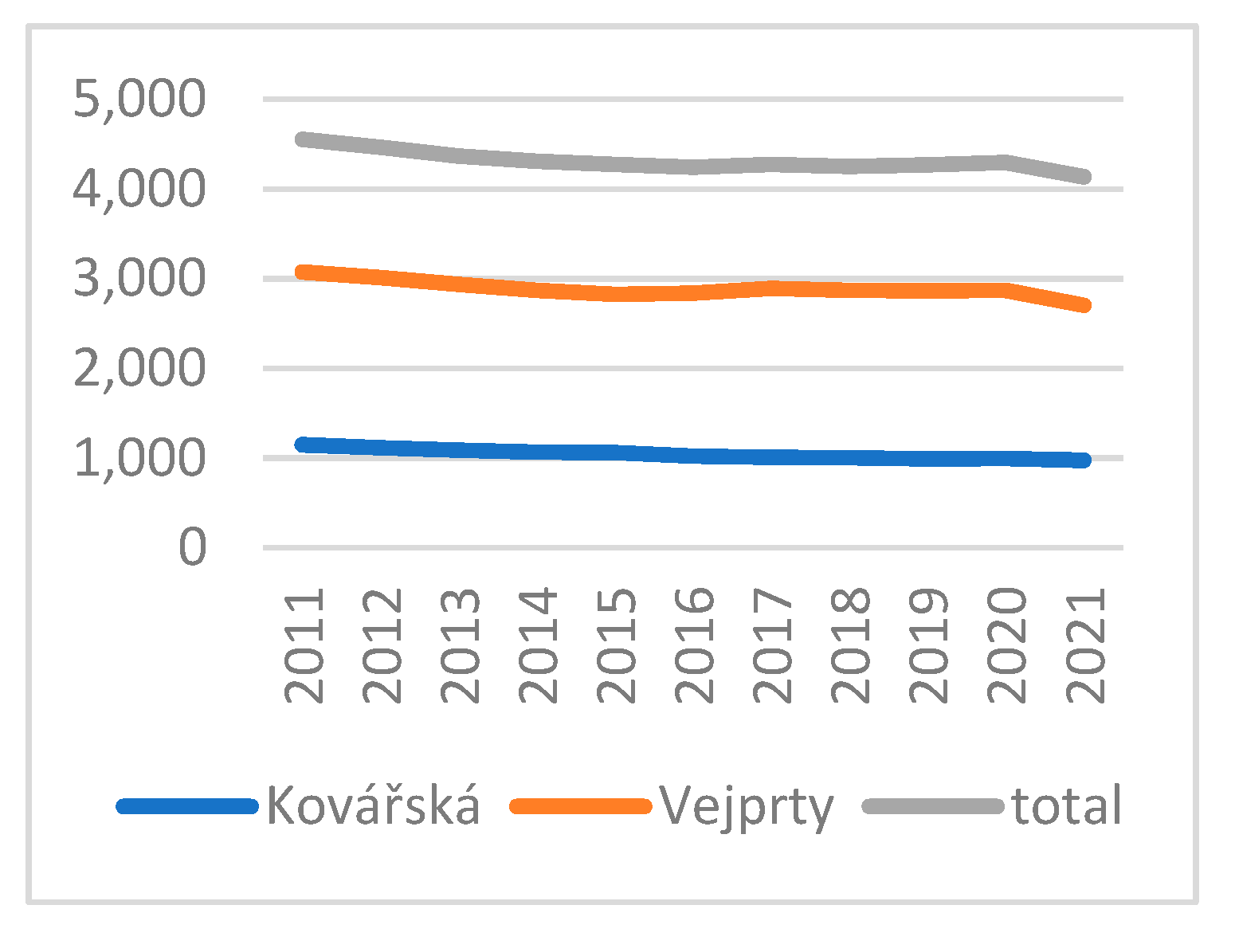

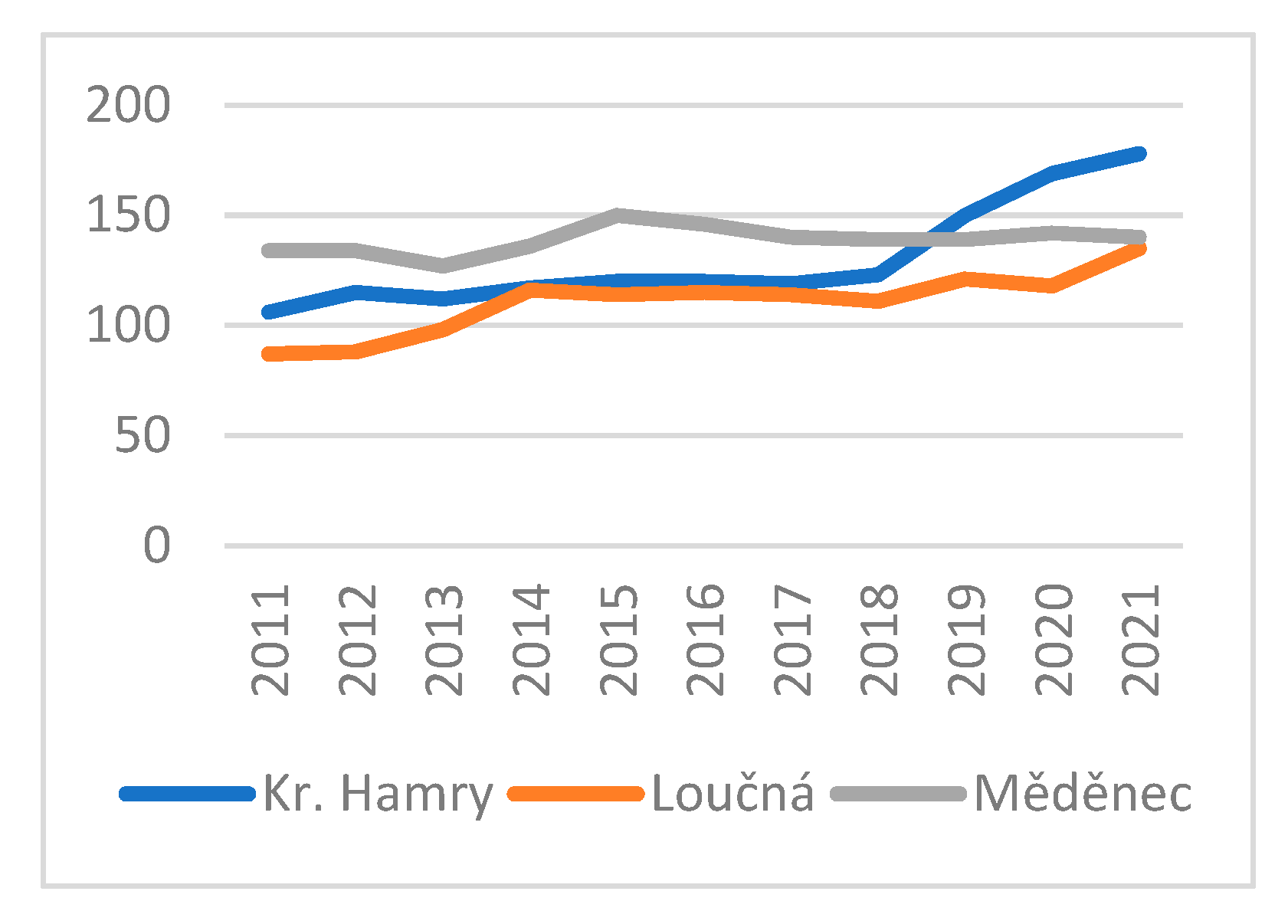

The development of the population since the last census has varied for large and small settlements (

Figure 3, 4). In large settlements (such as Vejprty and Kovářská), the population decline continues. This also reduces the total population of the micro-region. However, the trend seems to have reversed in very small settlements, with their populations growing very slightly. There is a tendency known from other regions for some people to choose a quiet environment with very small villages while being willing to accept their poor infrastructures.

Regarding the demographic development over the last five years, the micro-region has a very significant natural decline of 3.8% of the total population, which is a consequence of past developments, namely aging. In contrast, the microregion recorded essentially the same migration growth, so the overall balance is neutral. The total population by 31st December 2022 was 4,312 people.

3.4. Urban development

Such mass declines in the population had to be reflected in the decay and eventual liquidation of housing stock in the affected settlements. In 1930, there were 3,700 houses in the micro-region. By 1980, however, there were only 973 houses, meaning a decrease of 74% occurred. Together with changes in the social and economic composition of the population and with the architectural and urban trends of the time, extensive changes in the urban structure of individual towns and townships meant the extinction or even deliberate destruction of historical heritage, the creation of new quasi-modern structures and often a change in the character of urban structures from urban to rural. In the last five years 307 new flats were completed. By 2021, the number of houses increased to 1,399.

In the pre-war period, the number of houses in Vejprty (

Figure 5) grew significantly. The peak of the number of houses reached the micro-region in the 1950 census. The largest loss of houses was caused by the construction of the Přísečnice waterworks which was associated with the liquidation of the town of Přísečnice and several surrounding villages. However, Loučná pod Klínovcem and Měděnec also recorded extraordinary losses of houses. Some buildings were apparently demolished due to the ‘clearing’ of the zone at the very state border. The number of houses in Vejprty was reduced by half. Only Kovářská (

Figure 6) lost relatively few (43%) houses. However, the period with the greatest losses of houses was the 1950s to the 1960s. Later, the process of house demolition was slowed down or stopped in connection with the growth of interest in second homes.

In the last 40 years, the number of houses has started to slightly grow again. This is related to urban to rural migration beginning to predominate - as well as the greater need for housing due to the decrease in the average size of a household. Construction is taking place in the smallest municipalities. New construction (273 new flats) has been mainly concentrated in Loučná pod Klínovcem, where the development of the Scandinavian type of architecture takes place.

A significant disruption of the original urban shape took place in Vejprty. An important motive for the demolition of many houses was the deliberate disruption of the original German architecture and its replacement by socialist panel constructions for members of the armed forces and the inhabitants of the abolished Přísečnice. The current town centre is a disharmonious tangle of up to six story panel houses with torsos of the original lower blocks and detached villas. Kuča stated that the conscious destruction of Vejprty is one of the lesser known town planning crimes of the socialist period in Czechia [

26].

Přísečnice, which was considered to be an exceptionally interesting place in terms of history and monuments, was demolished in 1974 [

27]. This demolition included the chateau, two late Gothic churches, the Empire town hall and many late Gothic burgher houses. Loučná pod Klínovcem (

Figure 7) was gradually liquidated until the 1990s, while the church was demolished in the 1970s. The decline of the town was not so much the fault of the socialist system as it was the disruption of the original German settlement. After 1990, Loučná became a lively Vietnamese market after the establishment of a pedestrian crossing to the German recreation centre Oberwiesenthal. Today, it represents the origin of the mountain resort below Mount Klínovec. Thanks to its location, the remote Měděnec was relatively well-preserved until the expulsion of the Germans. In the second half of the last century, however, the city almost disappeared. Most of the houses were demolished, and prefabricated family semi-detached houses and an oversized residential house of the mountain hotel type were built in their place, which completely disturbed the original character of the material structure. Měděnec's (

Figure 8) torso became the worst disturbed of all the Ore Mountains' renaissance montane towns [

28].

3.5. Human capital

The qualification structure of the population is decisive for development. In this regard, Vejprty’s situation can be classified as extremely bad in 2021 (Data in this chapter originate from the 2021 Population Census. Czech Statistical Office Prague). As many as 4% of the population over the age of 15 lack education (0.6% nationwide). The absolutely predominant type of education is basic, including education that is incomplete, and apprenticeship. These two types apply to 55.9% of the population (43.5% nationwide). The percentage of the population that achieved secondary education with a GCSE is 25.7% (nationally 30.9%), with only 6.8% achieving university education (nationally 19.1%). The level of formal education is one of the consequences of the post-war population exchange and social experiments aimed at eliminating the middle class. It is likely the biggest obstacle of the micro-region to adapt to changing conditions and it precludes the transition to a smart economy.

The level of education is reflected in the economic structure of the population. The significantly highest share of the economically active population was associated with industry in the 2021 census (30.3%). This was followed by social services (particularly health care and education), with 20.0% of employees. Other sectors occupy smaller shares: construction 9.4%, trade and repairs 7.4%, tourism 6.4%, logistics 4.2%. The lowest share was related to agriculture and forestry (3.1%). Thus, it is clear that the economic structure of a micro-region depends to a very high extent on industry and services provided or guaranteed by the state. Although this structure makes the micro-regional labour market more resilient to short-term fluctuations, it may signal a more passive behaviour of the population. Moreover, the young and educated inhabitants hardly find adequate prestigious and well-paid jobs in such conditions and therefore leave, as Vaishar and Pavlů have shown, following the example of another area after uranium mining [

29].

The rural population with a lower level of education tends to vote more for extremist and non-systemic parties. In the last elections to the Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic in 2021, the shares of major parties in valid votes were as follows, from most votes to least: the ANO party (A. Babiš movement controlled by corporate management style; 43% of votes), SPOLU (a coalition of right-wing parties, 18.4%), SPD (nationalist and anti-migration movement of T. Okamura; 11,3%), Pirates and Mayors (non-ideological party, promoting the digital society and other modern approaches and municipally anchorage association; 9.8%), Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (4.8%). Significantly better results than at the national level were achieved by the ANO, SPD and Communist Party in particular. In contrast, SPOLU and Pirates with Mayors gained fewer votes. Loučná pod Klínovcem is separated from the overall picture, where SPOLU (57.7%) won, whereas ANO gained only 16.5%. It appears that socially advantaged citizens are likely moving to new flats in Loučná.

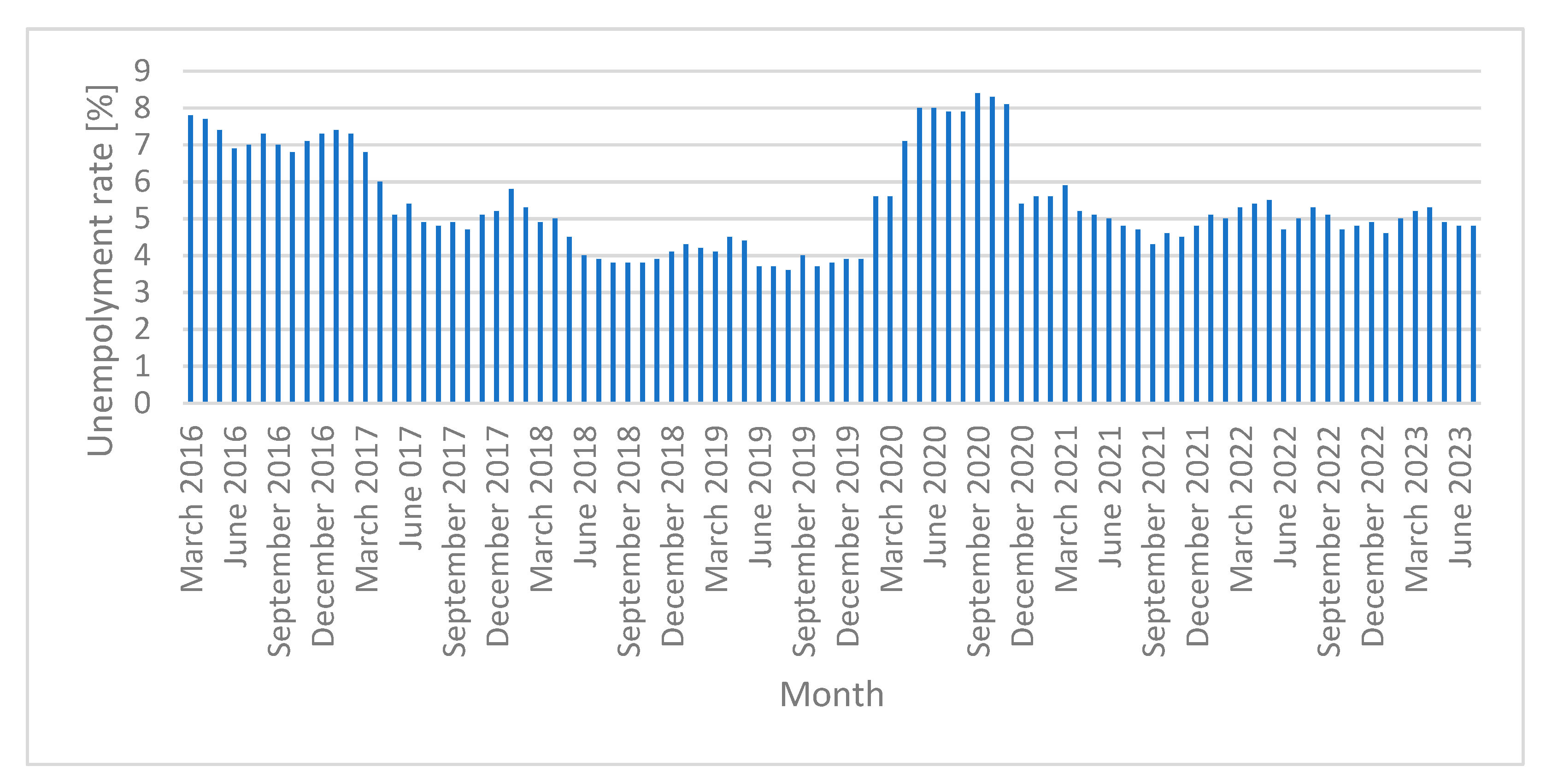

However, if we take into account the fact that the national level of unemployment is around 3%, unemployment in the Vejprty microregion is extremely high (

Figure 6). After staying at high levels in 2016, unemployment fell to 4% in 2019. In 2020, however, it rose sharply again. One of the reasons for this may be the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequences of anti-pandemic measures. However, there has been no such rise in unemployment in other regions. This may indicate that part of the labour force was employed on a short-term basis or on the edge of the grey economy and was therefore not protected by the Labour Code and government labour market protection measures. In 2021, unemployment fell to around five percent, but still remains well above average. In November of 2023 the unemployment rate reached 4.4%.

According to the population census in 2021, of the total population, 29% were non-working pensioners (22.1% nationwide). The lower local embeddedness of the population is evidenced by the minimal proportions of people who declared they had a religious faith in 2021: 6.5% of those professing a church, 5.1% without affiliation with the church. In addition, 9% of the population was reported as being national minorities, which is higher than the national percentage of 3.9%. The Germans remained the strongest minority (4.2% of the population), followed by Vietnamese, Slovaks, Roma and Ukrainians.

Lower population stability may signal weaker social capital. More than 75 years have passed since the expulsion of the German population. The original population was replaced by an ethnically homogeneous population that, however, came from different regions. Therefore, purposeful relationships between people and a positive attitude towards the location, which could be the motives for development trends, were formed slowly and only in a part of the population. This can limit the number of business plans that actually strive to increase the competitiveness of the micro-region and offer interesting job opportunities. The quality of social capital in the Vejprty micro-region was examined by Jančák et al. and later by Pileček, Chromý and Jančák, who stated that, as is the case with other borderland micro-regions, the quality is lower than in the inner periphery [

30,

31].

3.6. Environmental development

Economically lagging regions tend to have a more preserved natural environment. The coefficient of ecological stability expresses the ratio of ecologically stable areas (mainly forests, meadows, pastures and water areas) and ecologically unstable areas (especially arable land, built-up and other areas). Its value 14.1 in the Vejprty area is extremely high, as is biodiversity. Most of the remains of the mining activity have been liquidated, with what is left serving as tourist attractions. The landscape has been disturbed by the construction of a wind farm with a propeller height of 119 m. However, the construction has not met with resistance from local people. Today, wind farm dominates a part of the territory. The Přísečnice water reservoir, which has a water management function, contributes to the calming of the area. However, recreational and similar functions are excluded here. The road traffic load is minimal in the area. The main second class access road No. 224 recorded a totally negligible load of 1,338 unit vehicles in 24 hours (2020) and 2,017 unit vehicles in the Vejprty urban area towards the border crossing [

32].

Another issue is the weak environmental infrastructure in remote areas. The volume of discharged pollutants is absolutely low, but with consideration of plastics being used as the main packaging material and the use of household chemicals, even a small amount of waste is poorly degradable in nature. Of the total number of 1,633 dwellings, only 2.6% were heated by electricity and 5.8% by gas in the 2021 census. It can be assumed that the other dwellings were heated by solid fuels, likely coal and wood. In Vejprty, Kovářská and Měděnec, 70% of flats are connected to the sewerage network. Other households typically use cesspools or cisterns. The Vejprty–Bärenstein wastewater treatment plant was modernised as one of the cross-border cooperation projects in 2007. In 2013, the Loučná wastewater treatment plant was established with Czech–German cooperation. The situation regarding wastewater treatment has, therefore, significantly improved recently.

4. Discussion

Vejprty and its surroundings are an example of a once prosperous micro-region that is declining in modern times, and this tendency seems unstoppable. Economic decline is followed by demographic and social decline, which limits the possibility of restarting the economy.

It would be very easy to identify the displacement of the German population as the main cause of the negative development. In fact, developments in recent years have been the result of the interaction of a number of adverse influences and circumstances. Rather, the prosperity of the whole area – based on the mining of iron ores, nonferrous metals and silver – can be considered as an anomaly. The depletion of deposits was logically followed by a gradual decline, influenced by both historical events and the structural reconstruction of the economy.

The main problem is the remote location, not only in terms of the distance from major centres of settlement, but also in regard to the poorer permeability of the mountain terrain. Combined with unfavourable conditions for agriculture, the region did not have favourable development prospects until ore deposits were discovered and allowed to be mined.

The second problem is the structure of the local economy, which was formed after mining ceased. The light industry brought prosperity to the micro-region so long as special handicraft production was competitive. However, in the twentieth century, with the advent of mass production and heavy industry, the economy began to lag behind. In particular, it proved to be less resilient to the economic crisis of the 1930s. This situation could not improve even in the short period of Vejprty belonging to the German Empire. After WWII, it again did not correspond to the tasks of Czechoslovakia within the division of labour of the CMEA. The economy of Vejprty survived within the redistribution mechanisms of the centrally planned economy. The localised light industry has not been competitive even after the restoration of liberal capitalism in the 1990s as the conditions for some smart production are not present.

The third factor to adversely affected the Vejprty microregion was the political development in relation to the ethnic and cultural structure of the population. Although the border between Bohemia and Saxony has existed for a thousand years, its character gradually sharpened during the last century, making the Vejprty area increasingly peripheral. After the creation of Czechoslovakia in 1918, the Germans were not considered a state forming nation, thanks to their efforts to secede. This has logically led to a worsened approach of local companies to government procurement, particularly of a military nature. The relaxation of the border regime at the turn of the century paradoxically meant another decline for the microregion as the armed forces left.

The post-war expulsion of the Germans and the following insufficient settlement of the Slavic population meant a fatal decline in the population that had not yet fully stopped. However, the decisive problem was not the decline in the population itself. After all, the population of neighbouring Saxon Bärenstein (where no deportation took place) fell between 1910 and 2019 from 6,460 to 2,282. The destruction of the social structure of the original population and the urban structure of its towns and villages was the main problem. The Czech northern frontier has become a place of social experiments aimed at creating a classless society. Virtually all residents were to be employees of socialist enterprises and services, and thus dependent on the state. In an area with an exchanged population, this was much easier, because traditions and the relationships to the territory, to the villages and among people were broken. After 1989, there was nothing to build on. If the future prosperity of peripheral regions should be based on the mobilisation of local human capital, it is at its low level that the biggest weakness of the Vejprty microregion can be seen. The strategy of community-driven local development of the Western Ore Mountains Local Action Group from 2014 to 2020 has identified a non-existent or weak regional identity as one of the weaknesses.

Thus, is the Vejprty area doomed to be an eternal periphery without any development prospects? Some hope has been raised in regard to the transition to a post-productive economy. In such a case, remoteness can become somewhat of an advantage; moreover, an unsuitable production structure would no longer be essential. Certain manifestations of this development can be seen in the cessation of population decline in the smallest municipalities and in the development of tourism. Possibilities in another microregion on the Bohemian – Saxonian border have been shown by Vaishar, Šťastná and Lipovská [

33].

The border position can also turn into an advantage in the case of mutually beneficial cross-border cooperation, which is no longer hindered by any political barriers. Cross-border cooperation would reduce the remoteness of the territory (as Saxon resorts are significantly better accessible) while also opening up recreational areas on both sides of the border for use. However, currency, linguistic, psychological, legislative and similar barriers remain to be overcome.

Although the positive turnaround was caused by external conditions – namely the overall technological and social development – it needs to be captured in specific regional and local policies. Here, it will be necessary to overcome again one of the important barriers, namely the affiliation of Vejprty to a different district and region than its natural decline. It is to be feared that Ústí nad Labem will not give priority to Vejprty while Karlovy Vary cannot. The micro-region is part of the local action group of the Western Ore Mountains, but its position in it is peripheral due to the current administrative arrangement. In 1993, an Association of Vejprty Municipalities was established to the same territorial extent as our area under study. Its goal is to supply municipalities with water and allow the drainage of wastewater. The municipalities of Vejprty and Kryštofovy Hamry have their own development plans. However, none of these activities suggest they will make significant contributions to the development of the micro-region. Rather, they are sub-initiatives reliant on external support.

5. Conclusions

This paper analysed the path of one border microregion through the twentieth century and the causes that, in mutual interaction, have led to its decline. In such cases, different authors and European politicians have focused on two strategies. The first is job creation in multifunctional agriculture, while the second is the promotion of tourism. Support for agriculture is a means against historical development, or rather, an effort to slow it down. In the case studied, it would be meaningless due to natural conditions. Support for tourism remains. However, it should not just be about supporting business in this sector. It is a total turn towards the commodification of the landscape as an environment for tourism, quality housing or social services. This means improving the environment, building and maintaining infrastructure and so on. Establishing destination management seems to be a key tool [

34].

The study of rural development is becoming more frequent. However, we are often making two mistakes. One is the view of the countryside as a homogeneous space that can be assessed globally from a regional, national or even European level. The other is to pick up individual forms of the countryside and assign extreme values (depopulation, unemployment, poor accessibility) to the countryside as a whole. In fact, there are many different rural areas with different conditions, characteristics and pathways that the area has taken to date.

Likewise, too much emphasis is placed on the influence of specific historical events and personalities on the development of regions. This follows from the tendency of each regime to totally negate the previous political system and to take its own merits. In reality, however, the development of technology and society moves in its own way, and individual political regimes and historical events can only temporarily modify them. Therefore, it is important to look at historical events in the context of specific interactions.

Thus, it is extremely important to know the specific pathways of individual declining rural regions and the mutual relations that have led to their current situation. Only in this way it will be possible to understand the causal context and consider ways to improve the situation. However, it can be generalised that natural conditions including geographical location, economic development and historical/political events almost always contribute to development.

The development from the end of preindustrial countryside (from the onset of capitalism in the middle of the nineteenth century, which was associated with the creation of civil society, the first demographic transition and the onset of nationalism in political relations) is crucial for the current situation. All of these circumstances have significantly contributed to the formation of development during the twentieth century including extremal cases of Nazism and Communism and, thus, to the starting position for the transition to a postindustrial countryside.

A relatively extreme case was chosen for the case study, in which several negative factors meet. But even in this case, the general development trends of the transition from preproductive to productive and finally postproductive society meet specific regional factors. This means that in any case, general recommendations to improve the situation need to be combined with specific microregional strategies and measurements. This makes research of this type attractive and neverending.

The article tries to contribute to the field of history, which we could perhaps call somewhat illogically contemporary history. This part of history from the rise of capitalism to the present best illustrates the current sociogeographical structure. Moreover, it is a part of history that is relatively well documented by written and statistical materials. It can be said without exaggeration that its knowledge is a necessary prerequisite for the successful management of today's society. The second aspect of our article is the focus on a relatively small area with the aim of showing that even small areas can have a distinctive history that is sometimes significantly different from neighbouring small regions. Even at the scale of a microregion, a relatively complex and multidisciplinary picture of the latest historical development and its conditionality can be created. The countryside is not homogeneous even from this point of view.

Author Contributions

A.V.: conceptualization, methodology, regional data, writing, photo, M.Š.: editing, ecological aspects, organisational support, H.N.: historical information, photo. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was realized within the terms of the project DG18P02OVV070 titled ‘Identification and permanent documentation of the cultural, landscape and settlement memory of the municipality - on the example of extinct settlements of Moravia and Silesia’ financed by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic under the program to support applied research and the experimental development of national and cultural identity for the 2018–2022 period NAKI (National and Cultural Identity) II.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Michaela Tichá for drawing the map of the microregion of interest.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shucksmith, M. Re-imagining the rural: From rural idyll to Good Countryside. Journal of Rural Studies 2018, 59, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P.; Karlsson, S.; Lundmark, L. Hyper-Production: A New Metric of Multifunctionality. European Countryside 2016, 7, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micha, E.; Mantino, F.; Dwyer, J.; Schuh, B.; van Bunnen, P.; Maucorps, A.; Kubinakova, K. Evaluation of the impact of the CAP on generational renewal, local development and jobs in rural areas. Publication Office of the EU: Luxembourg, 2019.

- Garrone, M.; Emmers, D.; Olper, A.; Swinnen, J. Jobs and agricultural policy: Impact of the common agricultural policy on EU agricultural employment. Food Policy 2019, 87, 101744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Yansui, L. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world, Journal of Rural Studies 2019, 68, 135–143. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.M.; Lichter, D.T. Rural Depopulation: Growth and Decline Processes over the Past Century. Rural Sociology 2019, 84, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, B. Exploring the role of the ERDF in regions with specific geographical features: islands, mountainous and sparsely populated areas, Regional Studies 2017, 51, 869–879. [CrossRef]

- Le Tourneau, F.M. Sparsely populated regions as a specific geographical environment, Journal of Rural Studies 2020, 75, 70–79. [CrossRef]

- Dax, T.; Fischer, M. An alternative policy approach to rural development in regions facing population decline, European Planning Studies 2018, 26, 297–315. [CrossRef]

- Ubarevičienė, R.; van Ham, M. Population decline in Lithuania: who lives in declining regions and who leaves? Regional Studies, Regional Science 2017, 4, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpper, P.; Kundolf, S.; Mettenberger, T.; Tuitjer, G. Rural regeneration strategies for declining regions: trade-off between novelty and practicability', European Planning Studies 2018, 26, 229–255. [CrossRef]

- van den Broeck, N.; Lambrecht, T.; Winter, A. Pre-industrial welfare between regional economies and local regimes: Rural poor relief in Flanders around 1800, Continuity and Change 2018, 33, 255–284. [CrossRef]

- Bosma, U.; Vanhaute, E. Learning from history: six hundred years of capitalist transformation of the global countryside, in Akram-Lodhi, H.; Dietz, K.; Engels, B.; McKay, B. (Eds.) The Edward Elgar Handbook of Critical Agrarian Studies. Edward Elgar: Cheltenham 2020, pp. 9–14.

- Heijman, W.; Hagelaar, G.; van der Heide, M. Rural Resilience as a New Development Concept. In: Dries, L.; Heijman, W.; Jongeneel, R.; Purnhagen.; Wesseler J. (Eds.) EU Bioeconomy Economics and Policies: Volume II, Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, 2019, pp. 195–211. [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, A. Rural Out-migration: Community consequences and Individual Migrant Experiences'. Sociologia Ruralis 2004, 44, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonts, M.; Horsley, J. The neoliberal countryside, in Scott, M.; Gallent, N.; Gkartzios, M. The Routledge Companion to Rural Planing, Routledge: London, 2019, chapter 10. London, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Almstedt, Å.; Brouder, P.; Karlsson, S.; Lundmark, L. Beyond Post-Productivism: From Rural Policy Discourse to Rural Diversity, European Countryside 2014, 6, 297–306. [CrossRef]

- Buitenhuis, Y.; Candel, J.J.L.; Termeer, K.J.A.M.; Feindt, P.H. Does the Common Agricultural Policy enhance farming systems’ resilience? Applying the Resilience Assessment Tool (ResAT) to a farming system case study in the Netherlands, Journal of Rural Studies 2020, 80, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, J.D.; Roep, D. Multifunctionality and rural development: the actual situation in Europe. In van Huylenbroeck G.; Durand, G. (Eds.) Multifunctional Agriculture; A new paradigm for European Agriculture and Rural Development, Ashgate: Farnham. 2003; pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J.; Kastenholz, E.; Figueiredo, E.; Soares da Silva, D. Who is consuming the countryside? An activity-based segmentation analysis of the domestic rural tourism market in Portugal. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2017, 31, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.W.; Hall, C.M. Nature-based tourism in peripheral areas: making peripheral areas competitive. In Hall C.M.; Boyd, S.W. (Eds.) Nature-based Tourism in Peripheral Areas. Channel View Publications: Bristol. 2005; pp. 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishar, A.; Dvořák, P.; Hubačíková, V.; Nosková, H.; Nováková, E.; Zapletalová, J. Regiony v pohraničí Institute of Geonics, Czech Academy of Sciences: Brno. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holly, W. Traces of German-Czech history in biographical interviews at the border. Construction of identities and the year 1938 in Bärenstein-Vejprty. In Meinhof, U.H. (Ed.) Living (with) borders: Identity discourses in East-West borders in Europe Routledge: London. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scherm, I.; Tiserová, P. Deux localités à la frontière germane-tchéque: Bärenstein (Allemagne) et Vejprty ex-Weipert (République Tchèque). Revue Géographique de l´Est 2003, 43. [CrossRef]

- Dvořák, T. Uranium Mining versus the “Purging” of the Borderlands: German Labour in the Jáchymov Mines in the Late 1940s and Early 1950s´ Soudobé dějiny 2005, 12, 626-671.

- Kuča, K. Města a městečka v Čechách, na Moravě a ve Slezsku. Vol. 8. Libri: Praha. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kuča, K. Města a městečka v Čechách, na Moravě a ve Slezsku. Vol. 6. Libri: Praha. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kuča, K. Města a městečka v Čechách, na Moravě a ve Slezsku. Vol. 3. Libri: Praha. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vaishar, A.; Pavlů, A. Outmigration intentions of secondary school students from a rural micro-region in the Czech inner periphery: a case study of the Bystřice nad Pernštejnem area in the Vysočina region. AUC Geographica 2018, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jančák, V.; Chromý, P.; Marada, M.; Havlíček, T.; Vondráčková, P. Sociální kapitál jako faktor rozvoje periferních oblastí: analýza vybraných složek sociálního kapitálu v typově odlišných periferiích Česka. Geografie 2010, 115, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pileček, J.; Chromý, P.; Jančák, V. Social Capital and Local Socio-economic Development. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 2013, 104, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National traffic census. Directorate of Roads and Motorways of the Czech Republic, Praha. 2020.

- Vaishar, A.; Šťastná, M.; Lipovská, Z. Possibilities of development of regions after mining: restoration of rural development in the Czech-Saxon borderland. Rural Areas and Development 2010, 7, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyall, A.; Garrod, B. Destination management: a perspective article, Tourism Review 2020, 75, 165–169. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).