Submitted:

08 January 2024

Posted:

08 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

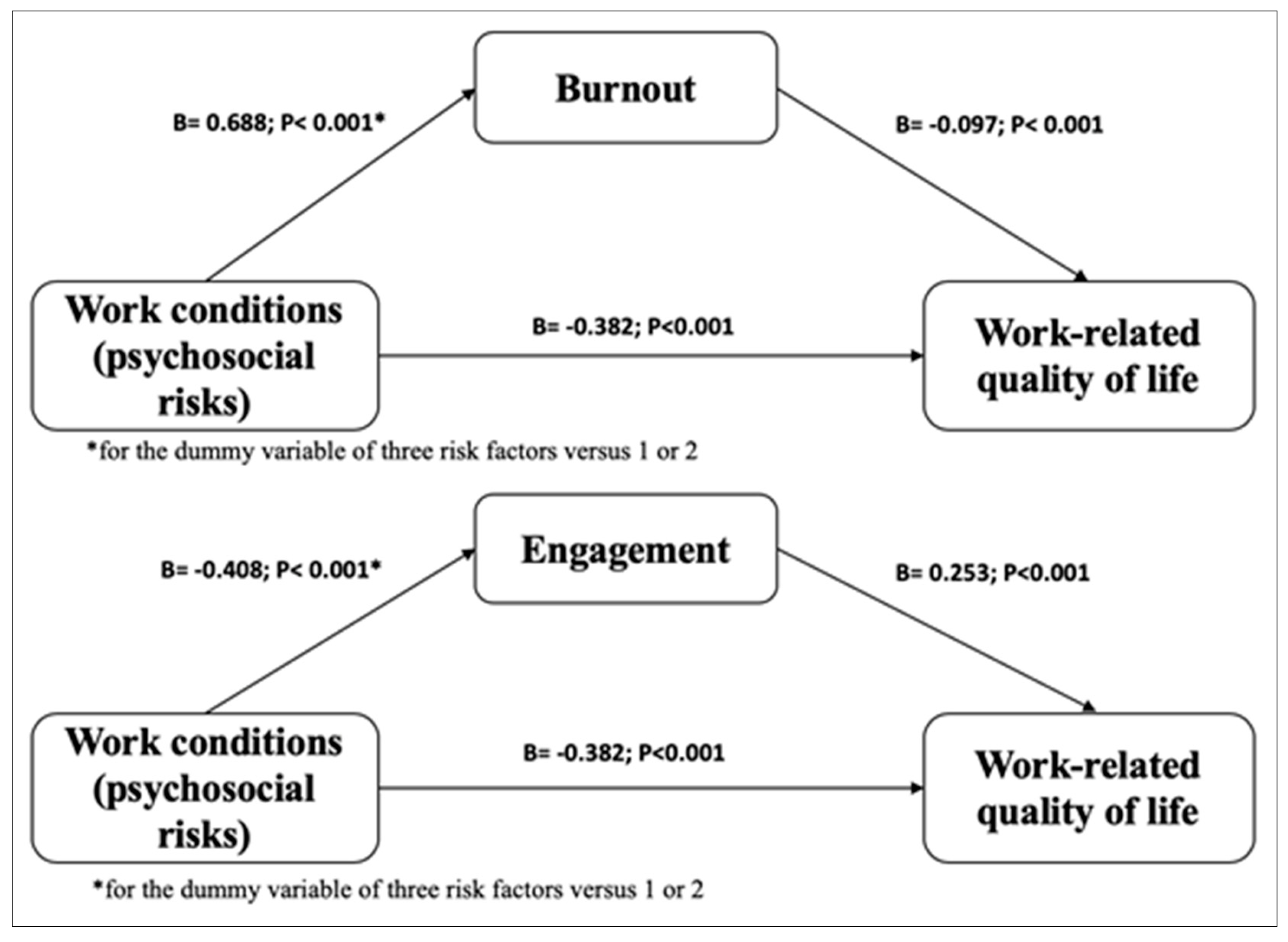

- Mediation Hypothesis. We postulate that both burnout and engagement significantly mediate the relationship between working conditions and WRQoL, providing a deeper understanding of how work dynamics affect the well-being of health care workers.

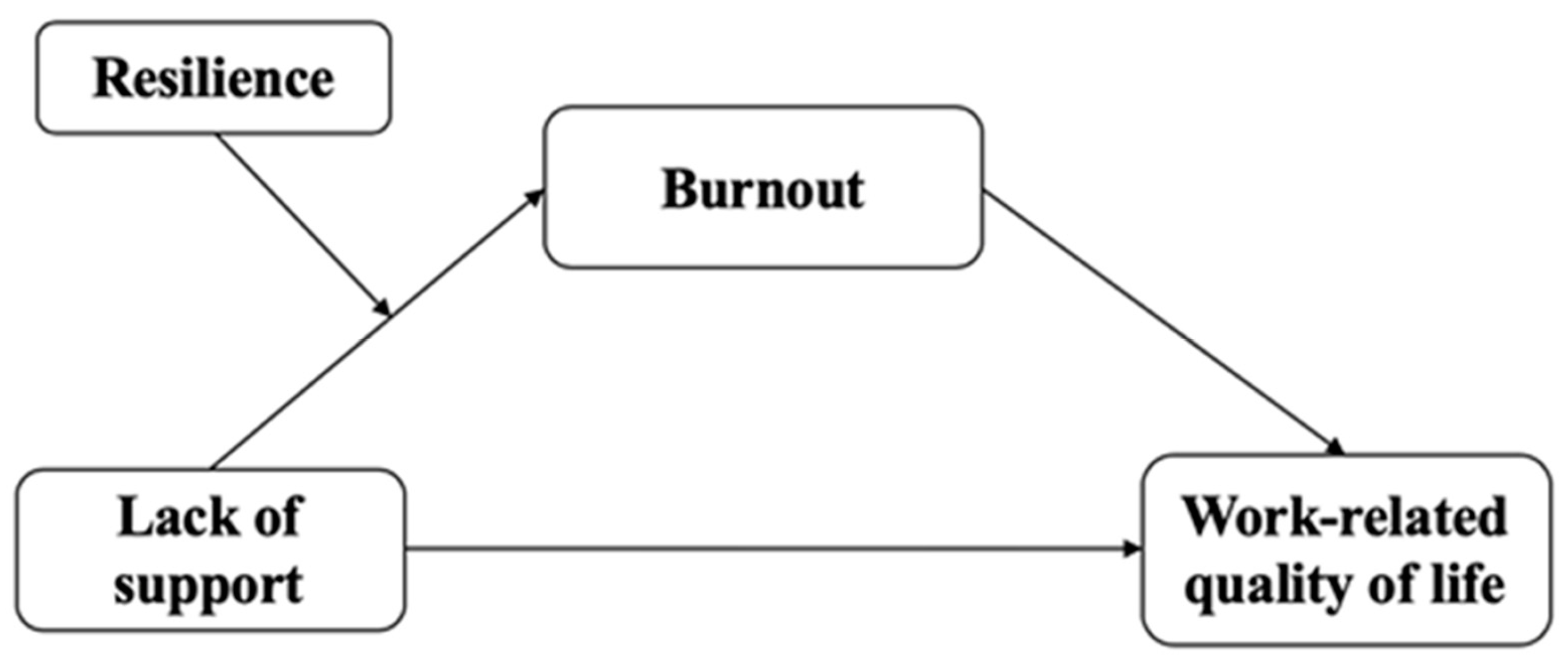

- Moderation Hypothesis: We propose that resilience and self-efficacy will moderate the relationship between working conditions and WRQoL, as well as mediate it through burnout and engagement, suggesting that these personal factors may reinforce or attenuate the effects of working conditions on WRQoL.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Psychosocial Risks

2.2.2. Work-Related Quality of Life

2.2.3. Engagement.

2.2.4. Burnout.

2.2.5. Resilience.

2.2.6. Workplace Self-efficacy

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Woman | 278 | 74,3% |

| Male | 96 | 25,7% | |

| Contract | Temporary | 107 | 28,6% |

| Permanent | 267 | 71,4% | |

| Disability | No | 361 | 96,5% |

| Yes | 13 | 3,5% | |

| Job Position | Clinic Assistant | 102 | 27,3% |

| Nurse | 209 | 55,9% | |

| Physician | 63 | 16,8% | |

| Service Area | General & Internal Medicine | 63 | 16,8% |

| Surgical | 62 | 16,6% | |

| Critical Care and Emergency | 111 | 29,7% | |

| Pediatric | 27 | 7,2% | |

| Diagnostic and Support | 18 | 4,8% | |

| Oncology & Palliative Med. | 33 | 8,8% | |

| Health Mental | 16 | 4,3% | |

| Women | 27 | 7,2% | |

| Other | 17 | 4,5% | |

| Risks | High Demand | 357 | 95,5% |

| Low Control | 323 | 86,4% | |

| Low Support | 73 | 19,5% |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 44,52 | 9,836 | -,156 | -,576 |

| Tenure | 15,22 | 11,023 | ,481 | -,770 |

| Working hours | 37,29 | 7,830 | ,996 | 5,943 |

| Work leaves days | 4,64 | 13,690 | 5,102 | 33,011 |

| Psychosocial Risks | 11,3503 | 4,96991 | ,578 | ,339 |

| Demand | 6,63369 | 2,969377 | ,289 | -,265 |

| Control | 5,76471 | 2,460026 | -,370 | -,604 |

| Support | 3,51872 | ,895878 | -2,114 | 4,199 |

| Burnout | 2,5033 | 1,17167 | ,998 | ,926 |

| Engagement | 4,2550 | ,89996 | -,832 | 1,067 |

| Workplace Self-efficacy | 6,2686 | 1,45508 | -,087 | -,035 |

| Resilience | 2,9556 | ,50308 | -,335 | -,021 |

| WRQoL | 3,5189 | ,57523 | -,248 | -,114 |

3.2. Mediation tests

| Variable | Engagement: partial η2 | Burnout: partial η2 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Tenure | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Contract | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Working hours | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Work leaves days | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Disability | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Job position | 0.016 | 0.017 |

| Service area | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| PRI | 0.150 | 0.150 |

3.3. Moderated Mediation Tests.

| Resilience | Effect | SE | t | p value | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + 1 SD | -0.307 | 0.063 | -4.858 | .001 | (-0.431 - -0.182) ** |

| mean value | -0.322 | 0.048 | -6.644 | .001 | (-0.417 - -0.226) ** |

| - 1 SD | -0.337 | 0.07 | -4.768 | .001 | (-0.476 - -0.198) ** |

| Sex value | Effect | Boot SE** | Boot CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| + 1 SD | -0.011 | 0.012 | (-0.047 - 0.002) |

| mean value | -0.024 | 0.014 | (-0.058 - -0.001) *** |

| - 1 SD | -0.036 | 0.02 | (-0.086 - -0.003) *** |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ortega-Galán, Á.M.; Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Lirola, M.-J.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D.; Ibáñez-Masero, O.; Cabrera-Troya, J.; Salinas-Pérez, V.; Gómez-Beltrán, P.A.; Fernández-Martínez, E. Professional Quality of Life and Perceived Stress in Health Professionals before COVID-19 in Spain: Primary and Hospital Care. Healthcare 2020, 8, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuriye, C.; Mustafa, M. The Effect of Stress, Anxiety and Burnout Levels of Healthcare Professionals Caring for COVID-19 Patients on Their Quality of Life. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permarupan, P. Y., Al Mamun, A., Samy, N. K., Saufi, R. A., & Hayat, N. Predicting Nurses Burnout through Quality of Work Life and Psychological Empowerment: A Study Towards Sustainable Healthcare Services in Malaysia. Sustainability 2019, 12(1), 388. [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, R.A., van den Broek, T., Cramm, J.M. et al. Changes in work conditions and well-being among healthcare professionals in long-term care settings in the Netherlands during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study. Hum Resource Health 2023, 21, 59. [CrossRef]

- Kandula UR, Wake AD. Assessment of Quality of Life Among Health Professionals During COVID-19: Review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021; 14:3571-3585. [CrossRef]

- oshi K, Modi B, Singhal S, Gupta S. Occupational Stress among Health Care Workers [Internet]. Identifying Occupational Stress and Coping Strategies. IntechOpen; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Barili, E., Bertoli, P., Grembi, V., & Rattini, V. Job satisfaction among healthcare workers in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Plos One 2022. 17(10), e0275334. [CrossRef]

- Ge, J., He, J., Liu, Y. et al. Effects of effort-reward imbalance, job satisfaction, and work engagement on self-rated health among healthcare workers. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 195. [CrossRef]

- Rieckert A, Schuit E, Bleijenberg N, et alHow can we build and maintain the resilience of our health care professionals during COVID-19? Recommendations based on a scoping review. BMJ Open 2021;11: e043718. [CrossRef]

- WHO, Building health systems resilience for universal health coverage and health security during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: WHO position paper. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 (WHO/UHL/PHCSP/2021.01). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- OECD, Ready for the Next Crisis? Investing in Health System Resilience, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ezura, M., Sawada, K., Takushi, Y., Matsui, H., Fukuda, Y., Nomura, K., & Asai, A. A systematic review of the characteristics of resilience training programs designed to improve resilience and mental health outcomes in physicians and nurses: What are we missing? Journal of Market Access & Health Policy 2023, 11(1), 2234139. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, S., Kelly, D., & Leighton, K. Influence of years of experience and age on hospital workforce retention. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2023, 28(7), 1741-1754. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H., Feher, G., Tibold, A., & Martins, C. Mediating Effect of Burnout on the Association Between Psychological Morbidity and Quality of Work Life Among Portuguese Medical Doctors. Brain Sciences 2021, 11(6), 813. 6. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. B., Reiser, V. L., Adelman, A. D., Carpenter, K. M., Hoerger, M., & Trevino, K. M. Burnout Among Oncology Nurses: The Effects of Palliative Care Education and Support. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 2022, 26(4), 391-398. [CrossRef]

- Gillen, P., Neill, R. D., Mallett, J., McFetridge, B., Moriarty, J., Mairs, A., ..., & McKenna, H. Wellbeing and coping of UK nurses, midwives and allied health professionals during COVID-19. PloS One 2022, 17(9), e0274036. [CrossRef]

- Martins, M. V., Valente, V. A., Simões, A. D., & Gama, J. A. Death is a sensitive topic when you are surrounded by it: End-of-life care in obstetrics. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare 2023, 35, 100817. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Hatanaka K, Takahashi K, Shimizu Y. Working Conditions Among Chinese Nurses Employed in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Survey-Based Study. SAGE Open Nursing. 2023;9. [CrossRef]

- Manzanares, I., Guerra, S. S., Mencía, M. L., Acar-Denizli, N., Salmerón, J. M., & Estalella, G. M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress, resilience and depression in health professionals: A cross-sectional study. International Nursing Review 2021, 68(4), 461-470. [CrossRef]

- Yun, Z., Zhou, P., & Zhang, B. High-Performance Work Systems, Thriving at Work, and Job Burnout among Nurses in Chinese Public Hospitals: The Role of Resilience at Work. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 10(10), 1935. [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, A., Sankai, T., & Omiya, T. Experience and Resilience of Japanese Public Health Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Their Impact on Burnout. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 11(8), 1114. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rey, R., Palacios, A., Alonso-Tapia, J., Pérez, E., Álvarez, E., Coca, A., Mencía, S., Marcos, A., Mayordomo-Colunga, J., Fernández, F., Gómez, F., Cruz, J., Ordóñez, O., & Llorente, A. Burnout and posttraumatic stress in paediatric critical care personnel: Prediction from resilience and coping styles. Australian Critical Care 2019, 32(1), 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Fernández, R., Corral-Liria, I., Trevissón-Redondo, B., Lopez-Lopez, D., & Losa-Iglesias, M. Burnout, resilience and psychological flexibility in frontline nurses during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) in Madrid, Spain. Journal of Nursing Management 2022, 30(7), 2549-2556. [CrossRef]

- Luceño-Moreno, L., Talavera-Velasco, B., García-Albuerne, Y., & Martín-García, J. Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Levels of Resilience and Burnout in Spanish Health Personnel during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(15), 5514. [CrossRef]

- Luceño-Moreno, L., Talavera-Velasco, B., Vázquez-Estévez, D., & Martín-García, J. Mental Health, Burnout, and Resilience in Healthcare Professionals After the First Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2022, 64(3), e114–e123. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-González, A., Velando-Soriano, A., De La Fuente-Solana, E. I., Martos-Cabrera, B. M., Membrive-Jiménez, M. J., Lucía, B., & Cañadas-De La Fuente, G. A. Relation and effect of resilience on burnout in nurses: A literature review and meta-analysis. International Nursing Review 2023. [CrossRef]

- León-Pérez, J.M.; Antino, M. & León-Rubio, J.M. Adaptation of the short version of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-12) into Spanish / Adaptación al español de la versión reducida del Cuestionario de Capital Psicológico (PCQ-12), International Journal of Social Psychology 2017, 32:1, 196-213. [CrossRef]

- León-Pérez, J.M., Antino, M., & León-Rubio, J.M.. The Role of Psychological Capital and Intragroup Conflict on Employees' Burnout and Quality of Service: A Multilevel Approach. Frontiers in Psychology 2016, 7, 212663. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Luan, Y., Liu, D., Dai, J., Wang, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, S., Dong, X., & Bi, H. Guided self-help mindfulness-based intervention for increasing psychological resilience and reducing job burnout in psychiatric nurses: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Practice 2023, e13204. [CrossRef]

- Moffatt-Bruce, S. D., Nguyen, M. C., Steinberg, B., Holliday, S., & Klatt, M.. Interventions to Reduce Burnout and Improve Resilience: Impact on a Health System's Outcomes. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2019, 62(3), 432–443. [CrossRef]

- Safaeian, A., Tavakolifard, N., & Roohi, A. Investigating the effectiveness of innovative intervention based on compassion, awareness, resilience, and empowerment on burnout in nurses of two educational hospitals in Isfahan. Journal of Education and Health Promotion 2022, 11, 65. [CrossRef]

- Strout, K., Schwartz-Mette, R., McNamara, J., Parsons, K., Walsh, D., Bonnet, J., O'Brien, L. M., Robinson, K., Sibley, S., Smith, A., Sapp, M., Sprague, L., Sabegh, N. S., Robinson, K., & Henderson, A. Wellness in Nursing Education to Promote Resilience and Reduce Burnout: Protocol for a Holistic Multidimensional Wellness Intervention and Longitudinal Research Study Design in Nursing Education. JMIR Research Protocols 2023, 12, e49020. [CrossRef]

- Ho, A. H., Ngo, T. A., Ong, G., Chong, P. H., Dignadice, D., & Potash, J. A Novel Mindful-Compassion Art-Based Therapy for Reducing Burnout and Promoting Resilience Among Healthcare Workers: Findings From a Waitlist Randomized Control Trial. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 744443. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 1977, 84(2), 191–215. [CrossRef]

- Molero Jurado, M. D., Oropesa Ruiz, N. F., Simón Márquez, M. D., & Gázquez Linares, J. J. Self-Efficacy and Emotional Intelligence as Predictors of Perceived Stress in Nursing Professionals. Medicina 2019, 55(6), 237. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Chao MMa; Ge, Yiling MBa; Xu, Chao MMa; Zhang, Xinyan MBb; Lang, Hongjuan MMa. A correlation study of emergency department nurses’ fatigue, perceived stress, social support, and self-efficacy in grade III A hospitals of Xi’an. Medicine 2020 99(32): p e21052, August 07, 2020. 07 August. [CrossRef]

- Janko, M. R., & Smeds, M. R.. Burnout, depression, perceived stress, and self-efficacy in vascular surgery trainees. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2018, 69(4), 1233-1242. [CrossRef]

- Smeds, M. R., Janko, M. R., Allen, S., Amankwah, K., Arnell, T., Ansari, P., Balters, M., Hess, D., Ferguson, E., Jackson, P., Kimbrough, M. K., Knight, D., Johnson, M., Porter, M., Shames, B. D., Schroll, R., Shelton, J., Sussman, J., & Yoo, P. Burnout and its relationship with perceived stress, self-efficacy, depression, social support, and programmatic factors in general surgery residents. The American Journal of Surgery 2020, 219(6), 907-912. [CrossRef]

- Firdausi, A. N., Fitryasary, R. I., Tristiana, D., Fauziningtyas, R., & Thomas, D. C. Self-efficacy and social support have relationship with academic burnout in college nursing students. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2023, 73(02), S63-S66. [CrossRef]

- Bernales-Turpo, D., Quispe-Velasquez, R., Flores-Ticona, D., Saintila, J., Ruiz Mamani, P. G., Huancahuire-Vega, S., Morales-García, M., & Morales-García, W. C. Burnout, Professional Self-Efficacy, and Life Satisfaction as Predictors of Job Performance in Health Care Workers: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 2022. [CrossRef]

- Messerotti, A., Banchelli, F., Ferrari, S. et al. Investigating the association between physicians self-efficacy regarding communication skills and risk of “burnout”. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 271. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Li, J., Cao, B., Wang, F., Luo, L., & Xu, J. Mediating effects of self-efficacy, coping, burnout, and social support between job stress and mental health among young Chinese nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2020, 76(1), 163-173. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Liu, L., Lv, Z., Ma, F., Mao, Y., & Liu, Y. Effects of burnout and work engagement in the relationship between self-efficacy and safety behaviours—A chained mediation modelling analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2023. [CrossRef]

- He, W., Li, M., Ye, J., Shen, Y., Cao, Y., Zhou, S. & Han, X. Regulatory emotional self-efficacy as a mediator between high-performance work system perceived by nurses on their job burnout: a cross-sectional study, Psychology, Health & Medicine 2023, 28:3, 743-754. [CrossRef]

- Eurofound, Working conditions and sustainable work: An analysis using the job quality framework, Challenges and prospects in the EU series, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2021.

- Van Laar D, Edwards JA, Easton S. The Work-Related Quality of Life scale for healthcare workers. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;60(3):325-333. [CrossRef]

- González-Rico, P.; Guerrero-Barona, E.; Chambel, M.J.; Guerrero-Molina, M. Well-Being at Work: Burnout and Engagement Profiles of University Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 15436. [CrossRef]

- Falatah, R., & Alhalal, E. A structural equation model analysis of the association between work-related stress, burnout and job-related affective well-being among nurses in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Nursing Management 2022, 30(4), 892–900. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2023, 10, 25-53. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. C., Guo, Y. L., Chin, W. S., Cheng, N. Y., Ho, J. J., & Shiao, J. S. Patient-Nurse Ratio is Related to Nurses' Intention to Leave Their Job through Mediating Factors of Burnout and Job Dissatisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16(23), 4801. [CrossRef]

- Al Sabei, S. D., Labrague, L. J., Al-Rawajfah, O., AbuAlRub, R., Burney, I. A., & Jayapal, S. K. Relationship between interprofessional teamwork and nurses' intent to leave work: The mediating role of job satisfaction and burnout. Nursing Forum 2022, 57(4), 568–576. [CrossRef]

- Gong, S., Li, J., Tang, X., & Cao, X. Associations among professional quality of life dimensions, burnout, nursing practice environment, and turnover intention in newly graduated nurses. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 2022, 19(2), 138–148. [CrossRef]

- Foroughi Koldaer, Z., Akbari, B., & Asadi majreh, S. Structural model of the relationship between psychological capital and perceived social support with anxiety through mediation of burnout in female nurses. Medical Journal of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences 2021, 64(3), 3143-3153. [CrossRef]

- Chami-Malaeb, R. Relationship of perceived supervisor support, self-efficacy and turnover intention, the mediating role of burnout, Personnel Review 2022, Vol. 51 No. 3, pp. 1003-1019. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. R., Park, O. L., Kim, H. Y., & Kim, J. Y. Factors influencing well-being in clinical nurses: A path analysis using a multi-mediation model. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2019, 28(23-24), 4549–4559. [CrossRef]

- Jarrar, M., Al-Bsheish, M., Albaker, W., Alsaad, I., Alkhalifa, E., Alnufaili, S., Almajed, N., Alhawaj, R., Al-Hariri, M. T., Alsunni, A. A., Aldhmadi, B. K., & Alumran, A. Hospital Work Conditions and the Mediation Role of Burnout: Residents and Practicing Physicians Reporting Adverse Events. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2023, 16, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, N., Coşkun, H., & Polat, Ş. The Relationship Between Psychological Capital and the Occupational Psychologic Risks of Nurses: The Mediation Role of Compassion Satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2021, 53(1), 115–125. [CrossRef]

- 58. Lee LJ Lee LJ, Wehrlen L, Ding Y, Ross A. Professional quality of life, sleep disturbance and health among nurses: A mediation analysis. Nurs Open. 2022;9(6):2771-2780. [CrossRef]

- Shdaifat E, Al-Shdayfat N, Al-Ansari N. Professional Quality of Life, Work-Related Stress, and Job Satisfaction among Nurses in Saudi Arabia: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. J Environ Public Health. 2023; 2023:2063212. Published 2023 Jan 31. [CrossRef]

- Marques-Pinto, A., Jesus, É. H., Mendes, A. M. O. C., Fronteira, I., & Roberto, M. S. Nurses' Intention to Leave the Organization: A Mediation Study of Professional Burnout and Engagement. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 2018, 21, E32. [CrossRef]

- Polat, Ş., Hamit, C., & Yıldırım, N. Multiple Mediation Role of Emotion Management and Burnout on the Relationship between Cognitive Flexibility and Turnover Intention among Clinical Nurses. International Journal of Caring Sciences September-December 2022 15(3), 1990-2000.

- Sun, J., Sarfraz, M., Ivascu, L., Iqbal, K., & Mansoor, A. How Did Work-Related Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Hamper Healthcare Employee Performance during COVID-19? The Mediating Role of Job Burnout and Mental Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(16), 10359. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M., Li, Z., Zheng, X., Liu, M., & Feng, Y. The influence of perceived stress of Chinese healthcare workers after the opening of COVID-19: the bidirectional mediation between mental health and job burnout. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11, 1252103. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P. [Research Methodology] Metodología de la investigación. México: Compañía, 2006.

- León Rubio, J.M. & Avargues Navarro, M.L. [Appendix E: Psychosocial risks] Anexo E: Riesgos Psicosociales. J.J. Moreno Hurtado (Coord.). Manual de Evaluación de Riesgos Laborales, Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Empleo, Dirección General de Seguridad y Salud Laboral. 2005: 226-234.

- Warr P. The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. Journal of Occupational Psychology 1990, 63, 193–210. [CrossRef]

- Warr P., Cook J. & Wall T. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being. Journal of Occupational Psychology 1979, 52, 129–148. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., Gonzàlez-Romà, V., & Bakker, A. B. The measurement of burnout and engagement: A confirmative analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2002, 3:71-92.

- Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. B. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2002, 33(5), 464-481. [CrossRef]

- Melamed S, Kushnir T, Shirom, A Burnout and risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Behav Med 1992, 18:53-60. [CrossRef]

- SShirom, A., & Melamed, S. A comparison of the construct validity of two burnout measures in two groups of professionals. International Journal of Stress Management 2006, 13(2), 176. [CrossRef]

- Lundgren-Nilsson, Å., Jonsdottir, I. H., Pallant, J., & Ahlborg, G. Internal construct validity of the Shirom-Melamed Burnout questionnaire (SMBQ). BMC Public Health 2012, 12(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S. E., & Shirom, A. Stress and burnout in work organizations. In R. T. Golembiewski (Ed.), Handbook of organization behavior (pp. 41–61). New York: Dekker, 1993.

- Hobfoll, S. E., & Shirom, A. Conservation of resources theory: Applications to stress and management in the workplace. In R. T. Golembiewski (Ed.), Handbook of organization behavior (2nd Rev. ed., pp. 57–81). New York: Dekker, 2000.

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 2003, 18(2), 76-82. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. F. Pajares & T. Urdan (eds.), Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. IAP, 2006: 307-337.

- Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications, 2017.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).