1. Introduction

During many years of operation, the shape of existing railway lines gradually changes and after some time it begins to differ from its original layout, designed in accordance with applicable regulations. Due to passenger comfort and operational safety, deviations of the track axis in the horizontal plane may be particularly unfavorable. Therefore, it is necessary to know the current geometric shape of the route so that any iregularities can be eliminated and any corrections made. Appropriate measurement systems and computational algorithms serve this purpose.

The measurement methods currently used are similar in various railway administrations [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In addition to classic geodetic techniques, stationary satellite measurements are used based on the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) technique, which use the so-called active geodetic networks [

6]. Mobile satellite measurement methods are also being introduced [

7], in which, in addition to GNSS receivers, Inertial Navigation System (INS) devices [

8] and vision methods such as Terrestial Laser Scanning (TLS) [

9] are often used as supporting devices. Research is underway on the possibility of using systems composed of satellite receivers mounted on various types of vehicles [

10,

11].

The purpose of the measurements is to determine the geometric parameters (i.e. identification) of the measured route. This is done on the basis of the designated Cartesian coordinates of the track axis points in the appropriate state spatial reference system. In Poland – with respect to plane coordinates – the PL-2000 system [

12] is used, created on the basis of mathematically unique assignment of points on the reference elipsoid GRS 80 (Geodetic Reference System) [

13] to appropriate points on the plane according to the Gauss-Krüger projection theory [

14].

Determining the coordinates of the track axis enables the visualization of a given railway route, giving general orientation about its location. However, full identification of the measured route requires the use of appropriate computational algorithms. When considering the horizontal plane, the basis of the analysis are the determined values of the plane eastern coordinates Yi and northern coordinates Xi of a given measurement point in the PL-2000 system.

The current approach to the problem of identifying a measured railway route is to generate an aptimized geometric layout in a given areas by minimizing the deviations of this layout from the measurement points (while meeting the appropriate maintenance and operational requirements). The traditional solution to a design problem relies heavily on human experience [

15,

16]. Many works attempt to automate the discussed process. There are two variants of procedure: geometric identification [

17,

18,

19,

20] and alignment optimization [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. In the works [

27,

28,

29], several methods were proposed to combine these variants into an iterative process of reconstructing the track axis.

As it turns out, the problem of geometric identification of a railway track can be approached in a completely different way, moving away from matching the hypothetical model layout to the track axis points determined by direct measurements. The basis for identification may be curvature of geometric layout; an appropriate method for determining it should only be developed. In work [

30], a proposal for a new method for determining the curvature of the track axis, called „the moving chord method”, was presented.

However, in each case, the identification of the track’s geometric layout is based on Cartesian coordinates determined in field measurements. Most often these will be GNSS measurements, carried out static or mobile. There is no doubt that the most effective method of determining the coordinates of the railway track axis is mobile satellite measuremnts. However, there are situations when the satellite signal may be disturbed (due to field obstructions) or completely disappear (e.g. in tunnels). Then the ability to measure the value of the directional angle

Φ of the route using the inertial system comes in handy. Knowing this angle, along the simultaneous measurement of the distance ΔL, allows you to determine the Cartesian coordinates of the next measurement point (knowing the coordinates of the previous point). The following formulas apply to the PL-2000 system:

This article aims to present the principles of using the directional angle in the process of geometric identifying the railway track axis.

2. Directional angle of the railway route

The concept of a directional angle is particularly relevant in the field of traditional seafaring. There he uses the term so-called the diametrical line, i.e. an imaginary line connecting the bow and stern of the vessel, located in the ship’s symmetry plane. The diametrical line has no specific height in this plane, but is parallel to the horizon. This is directly related to the concept of course, i.e. the direction (horizontal) in which the ship is steered or should be steered. The heading is determined as a measure of the angle (in degrees, clockwise) from the north reference direction. Depending on the reference direction, there are true heading, magnetic heading, compass heading and gyrocompass heading. True course (TC) is the angle between true north (geographic meridian) and the front of the ship’s midline.

It is easy to see that the concept of a diametrical line can also be applied to the longitudinal axis of a railway wagon, defined by the line connecting the turning pins of bogies or wheel sets. The angle of inclination of the diametrical line relative to the north can therefore be treated as the directional angle (i.e. heading) of the rail vehicle. On straight sections of the route, the diametrical line of the wagon coincides with the axis of the railway track, and on curves it is parallel to the tangent to the track axis. The directional angle of the rail vehicle is closely related to the direction of its movement on a given railway line (it determines the heading of the wagon expressed in degrees).

The directional angle of the communication route is determined on the topographic map as the angle between the direction of the slope of the tangent to the geometric layout and the reference direction, which is the north. The values of the directional angle at a given point on the railway route result form the angle of inclination of the tangent to the track axis at that point. On straight sections, this tangent coincides with the track axis, so it can be easily determined by geodetic measurements by specifying appropriate Cartesian coordinates. On arc sections (i.e. transition curves and circular arcs), the matter is more complicated, because direct determination of tangents is difficult.

In this situation, when determining the value of the directional angle of the railway route, the inertial system should be used, which, however, does not determine the slope of the tangent to the track axis, but the directional angle of the rail vehicle. This angle results from the inclination of the longitudinal axis of the vehicle, or more precisely – from the inclination of the moving chord, the lenght of which is equal to the rigid base of the measuring wagon, and both ends are located on the track axis. Since the values of the directional angle of the railway route must be determined by the directional angle of the rail vehicle, it becomes necessary to explain what importance the length of the vehocle’s rigid base plays in this matter.

It should also be noted that there is a subtle difference between the above-mentioned concepts. The directional angle of the rail vehicle is closely related to the direction of its movement on a given railway line (it determines the direction of the wagon expressed in degrees). However, the railway line does not have a specific direction, so such a direction should be adopted, bearing in mind that it will be conventional. It seems that in order to maintain the unambiguity of the directional angle of the route, it would be most beneficial to the increasing mileage of the railway line.

In many case, there is a need to develop an effective method for determining both the directional angle of a railway line and the directional angle of a rail vehicle, based on appropriate measurement data. The latter should be Cartesian coordinates of the track axis, allowing for the visualization of a given railway route and obtaining a general orientation about its course. This article presents a proposed solution to the problem, referring to the assumptions made in the new method of determining the curvature of the railway track axis using a moving chord [

30]. To obtain greater transparency of the analysis, the focus was on the situation corresponding to the model geometric layout, determined according to the principles of the analytical design method [

31].

3. Proposed method for determining the directional angle of a railway route

3.1. Basic dependencies

If ϴi denotes the angle of inclination of the tangent to the track axis in the rectangular coordinate system, than the value of this angle directly results in the directional angle Φi of the route at a given point i. To obtain it, a simple transformation is needed, consisting in expressing the angle ϴi in degrees and using the appropriate pattern.

For

deg,

deg and

deg the formula applies

while for

deg

The given relationships show that if we know the values of the directional angle Φi (determined e.g. using the inertial system), then appropriate formulas allow us to determine the angle Θi.

For

deg,

deg and

deg the formula applies

while for

deg

3.2. Assumptions made

Therefore, the basic problem to solve remains to determine the value

Θi of the angle of inclination of the tangent at a given point. For this purpose, a chord of a specific length stretched along the track can be used, as is the case when determining the curvature of the track axis using the moving chord method [

30]. In this method, the basic task of the procedure for determining the curvature at the measurement point – based on the determined Cartesian coordinates – is to determine the values of the angles of inclination of two virtual chords (derived from this point forward and backward) to the abscissa of the appropriate rectangular coordinate system. The following assumptions were made:

- (a)

the tangents to the track axis and the corresponding chords are parallel to each other,

- (b)

the points of tangency project perpendicularly to the center of the given chord.

The above assumptions are met for a circular arc. However, along the length of the transition curve this is no longer the case, and the non-compliance resulting from failure to strictly meet these conditions is relatively small; it decreases as we move to the initial region of the transition curve.

The angles of inclination of both chords (front and rear ) do not refer to a given measuring point, but to points distant from the point i and by an amount corresponding to half the length of the chord. In order to create graphs of the Θ(L) relationship, it would be necessary to determine – separately for each chord – the linear coordinates of these points, which would require an additional calculation procedure. As it turns out, there is no such need, because the hypthetical angle of inclination ϴi of the tangent at point i can be determined in another, much simpler way, using the values of the inclination angles of both virtual chords.

Taking the determined values of angles

and

as the basis for calculations, it was assumed that the angle of inclination

ϴi of the tangent at point i is the value of the arithmetic mean of these angles.

Later in the article, this thesis was verified.

3.3. Computational algorithm

From a practical point of view, it will beneficial to transfer the measurement data to the local Cartesian coordinate system

x,

y. In most cases, this operation will consist in shifting the origin of the PL-2000 system to a selected point

O(Y0, X0) and rotating it by an angle

β. The following transformation formulas are then used [

32]:

A positive value of the β angle occurs when the system is rotated to the left.

The methodology for determining the curvature of the track axis was explained in detail in the work [

30]. Similarly, the sequence of activities aimed at determining the values of angles

and

at any measurement point is illustrated in

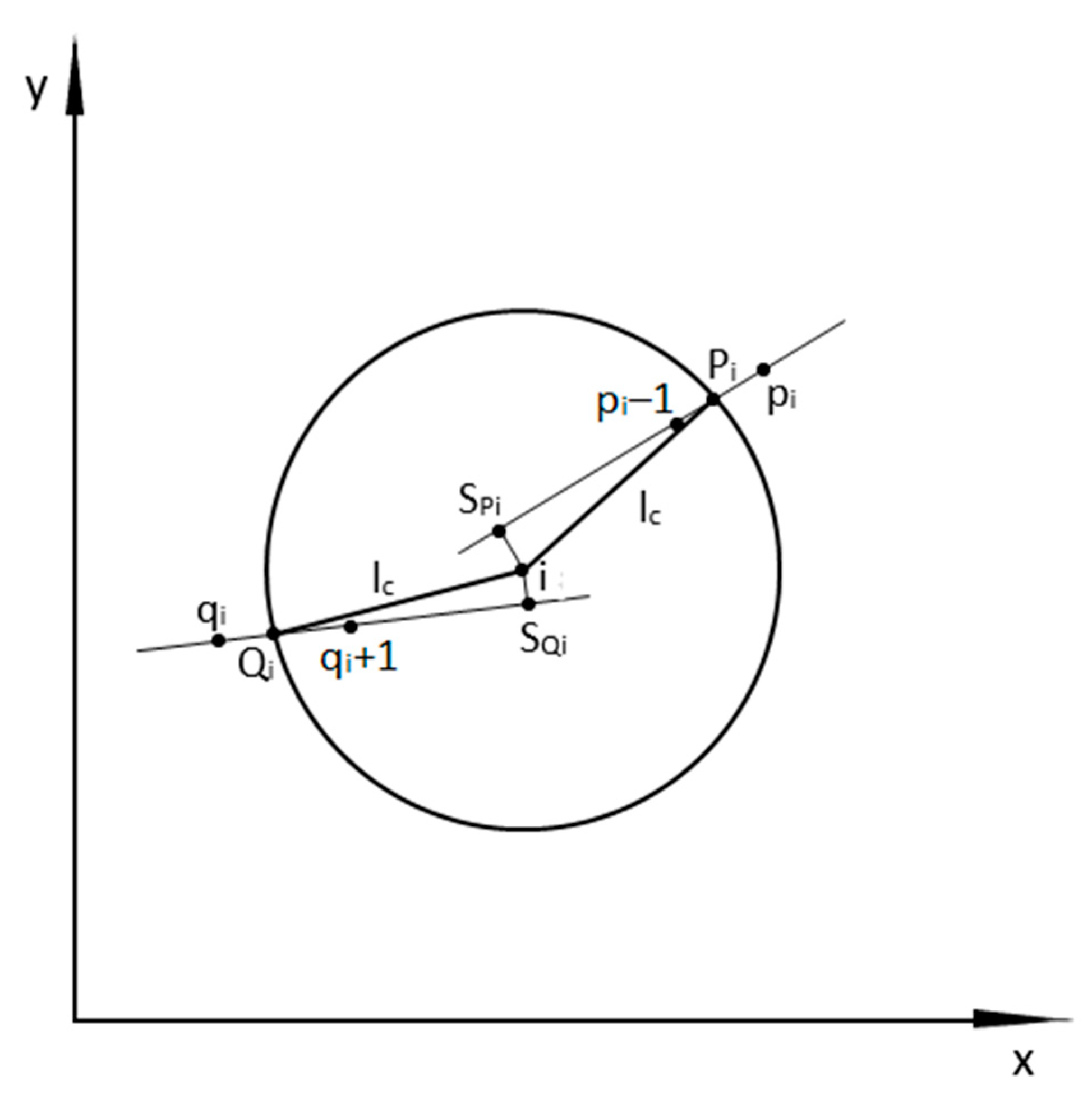

Figure 1.

The procedure for determining the data for determining the values of angles and begins with the measurement point i, which is located in such a way that it allows a virtual chord of length lc to be drawn backwards; te end of the calculations must occur at a point from which a virtual chord of the same length can still be drawn forward. The basic operation that must first be performed is to determine the numbering of the points marking the intervals in which the ends of the virtual chords derived from point i are located.

For a chord drawn from point

i forward, the interval in which the end of the chord occurs is determined by the points

pi–1 and

pi (

Figure 1). After determining them, it is possible to analytically write the equation of the straight line passing through these points. This equation has the following general form:

As can be seen in

Figure 1, the sought end of the front chord (i.e. point

Pi) lies on the line descrbed by equation (10), at a distance

lc from point

i. It is therefore the intersection point of a circle with radius

lc and centered at point

i with the line (10). The coordinates of point

Pi are determined from the following formulas:

where

The ”+” sign in formulas (11) and (12) appears when the abscissa values of the measured route points are increasing, while the ”–” point is valid for decreasing abscissa values.

From a chord drawn from point

i backwards, the interval in which the end of the chord occurs is determined by points

qi and

qi+1 (

Figure 1). We determine it in a similar way as in the case of the forward chord. The further course of action is also similar and leads to obtaining the coordinates of the

Qi point.

Having the Cartesian coordinates of point

i (obtained from measurements) and the coordinates of the ends of the virtual chords drawn forward and backward, we are able to determine the values of the angles of inclination of these chords

and

, and then the value of the angle of inclination of the tangent at a given measurement point. The forward chord connects point

i with point

Pi, whose coordinates are detrmined by formulas (11) and (12), Its angle of inclination is

A chord drawn backward connects the

i point with the

Qi point. Its angle of inclination is

In this situation, the value of the angle of inclination of the tangent at a given measurement point is determined using the formula (7). The presented course of action is sequential and involves the use of the given calculation formulas. Determining the directional angle value does not require the development of special computer programs, and the entire operation can be performed, for example, in a spreadsheet.

4. Assessment of the accuracy of the proposed method

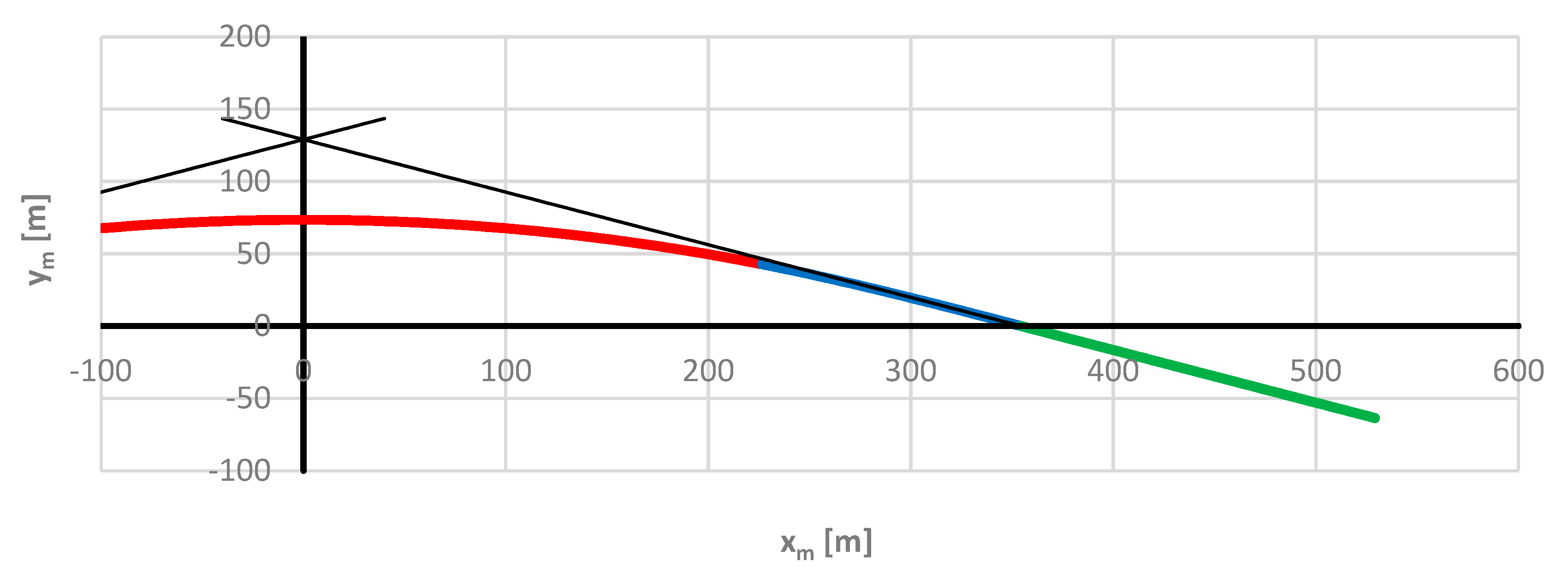

4.1. The adopted model geometric layout

The assessment of the accuracy of the proposed method for determining the directional angle of the railway route was carried out on the adopted model geometric track layout, created according to the principles of the analytical design method [

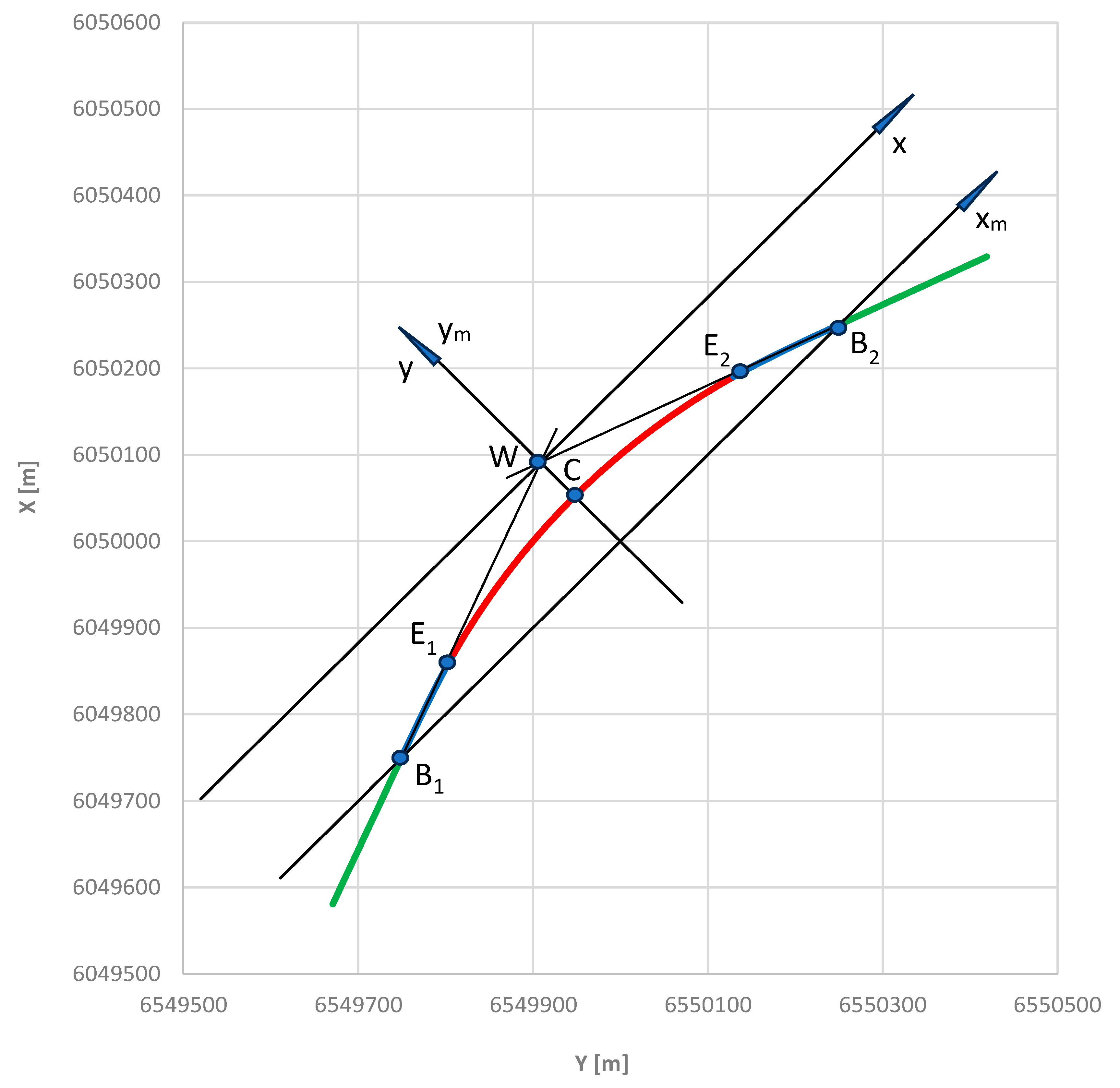

31]. The individual elements of this layout are desribed using mathematical equations, which greatly facilitates further analysis. The total length of the layout is 1100 m, with a route turning angle of α = 0.698132 rad. It is adapted to a speed of 120 km/h – it consists of a circular arc with a radius of 850 m, two transition curves in the form of a clothoid with a length of 135 m and two straight sections with a length of approx. 185 m. The location of the test section in the PL-2000 system is shown in

Figure 2. The circular arc is marked in red, transition curves in blue, and straight sections in green.

Figure 2 shows the axes of the local

x,

y coordinate system to which the transformation of the considered geometric layout will take place. The beginning of the

x,

y system is located at the intersection of the main directions of the route, and the alignment of its axes allows for symmetry of the geometric layout. The location of the corrected (i.e. shifted)

xm,

ym coordinate system, whose abscissa axia passes through the starting points of both transition curves, is also marked. Further analysis will be carried out in this setting.

The equations of the main directions of the route are as follows:

The coordinates of point W are: YW = 6550000 m, XW = 6050000 m.

In order to perform the transformation to the local coordinate system, move the origin of the PL-2000 system to point

W and rotate this system to the left by an angle

β = 0.785398 rad. After using formulas (8) and (9), in which

YO =

YW and

XO =

XW, the situation shown in

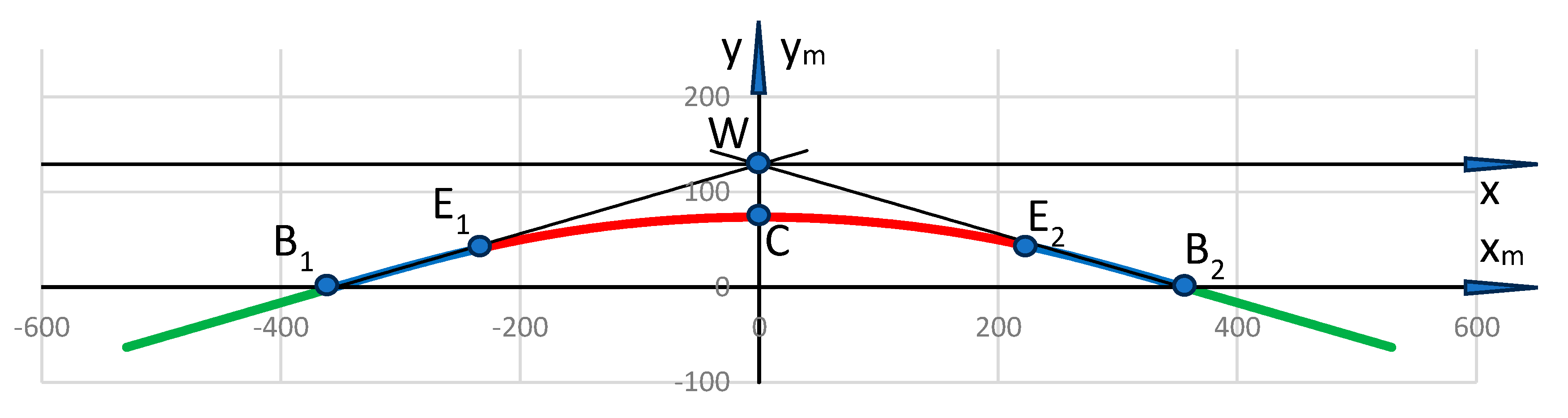

Figure 3 is obtained.

As you can see, in the x, y coordinate system, the ordinate values of the geometric layout are negative. In order to avoid certain difficulties resulting from this, it was decided to conduct further analysis in the adjusted xm, ym system; the coordinates of the characteristic points are defined as follows: the vertex of the layout W(0, 129.005) m, the beginning of the first transition curve B1(–354.439, 0) m, the end of the first transition curve E1(–226.438, 42.787) m, the center of the circular arc C(0, 73.504) m, the end of the second transition curve E2(226.438, 42.787) m and the beginning of the second transition curve B2(354.439, 0) m.

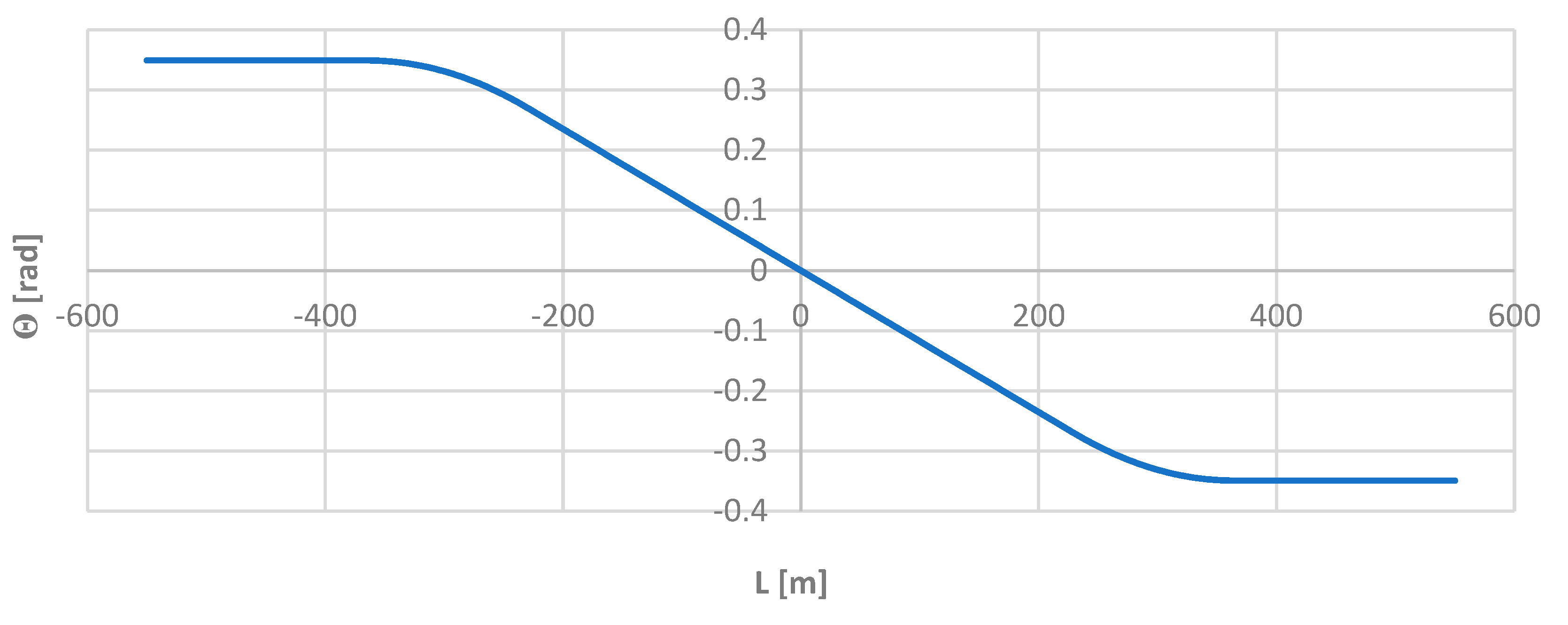

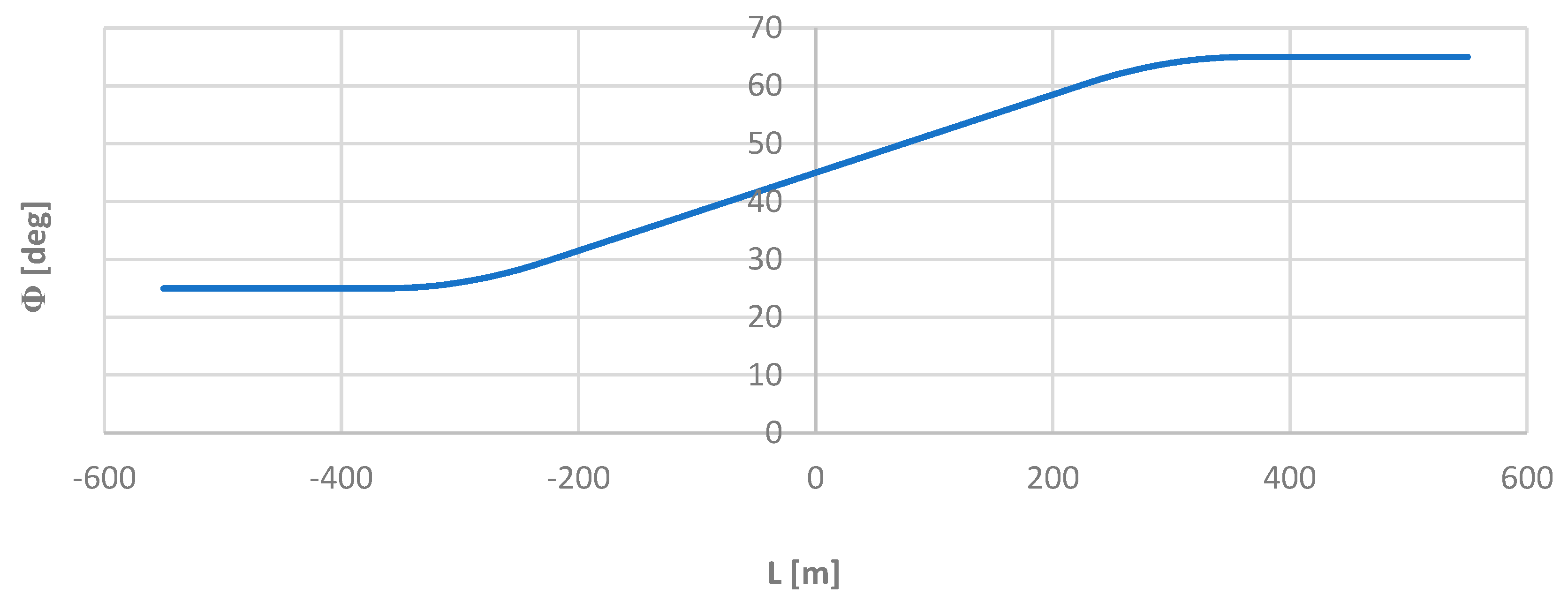

4.2. Directional angle of the model geometric layout

Knowledge of the mathematical notation of individual elements of the test layout allowed for the precise determination of the angle

ϴ of inclination of the tangent along its length

L, and then the corresponding directional angle

Φ of the route. The angle

Φ was then the reference for the values obtained by the moving chord method. The grphs of the functions

ϴ(

L) and

Φ(

L) are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

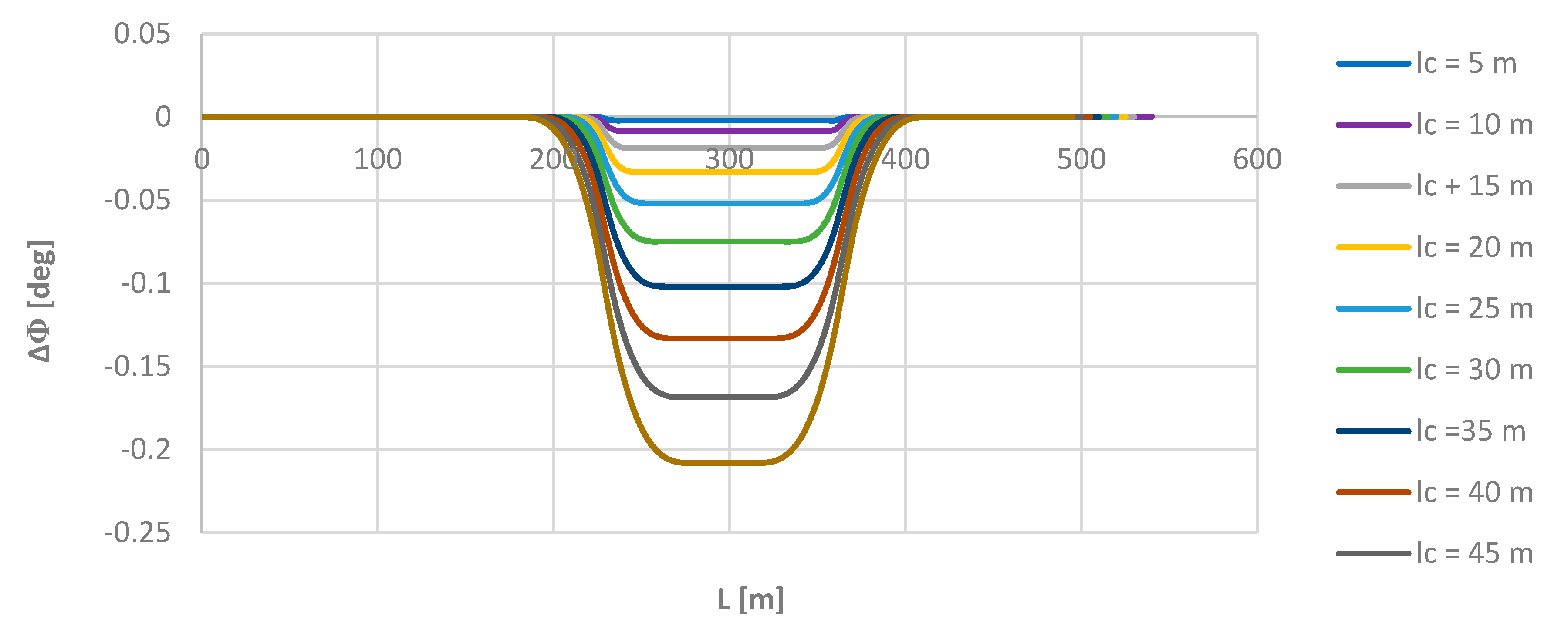

4.3. Assessment of the influence of the moving chord length used

Determining the directional angle of the route on the measurement way essentially involves determining the directional angle of the rail vehicle on which the inertial system has been installed. It is therefore necessary to check the influence of the length of the vehicle’s rigid base on the values of the determined directional angle of the route. In a given case, the rigid base is a mobile chord used in the proposed method of determining the directional angle. In the conducted analysis, it was decided not to limit ourselves to the range of rigid base length found in rolling stock, but to check the lengths of the moving chord in a much wider range – the assumed lengths were

lc = 5 ÷ 50 m in an interval of 5 m. Due to the symmetry of the test geometric layout, only its half was considered,, for positive values of the abscissa

xm (

Figure 6), with a possible extetion of the obtained results to the other half of the layout.

In all cases considered, analogous graphs of the inclination angles

ϴ and

Φ over the length

L were obtained, as shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 for the model geometric layout. To look for possible differences, the

Φ values obtained for individual chord lengths were compared with the appropriate theoretical values in the model layout.

Figure 7 shows the graphs of the Δ

Φ(

L) relationship for all the moving chord lengths

lc used.

As it turned out, the moving chord method shows full compliance with the reference layout on a circular arc (on the left in

Figure 7) and on a straight section (on the right), and some inconsistencies occur only (in a fixed form) along the length of the transition curve (in central region). The indicated inconsistencies are greater the graeter the chord length. However, it seems that from the practical point of view they are completely negligible; the highest demonstrated value of Δ

Φ, found for the chord

lc = 50 m, is only 0.208 deg. This clearly confirms the very high precision of the proposed method for determining the directional angle of the route and the lack of importance of the length of the rigid base of the rail vahicle when measuring this angle using an inertial system.

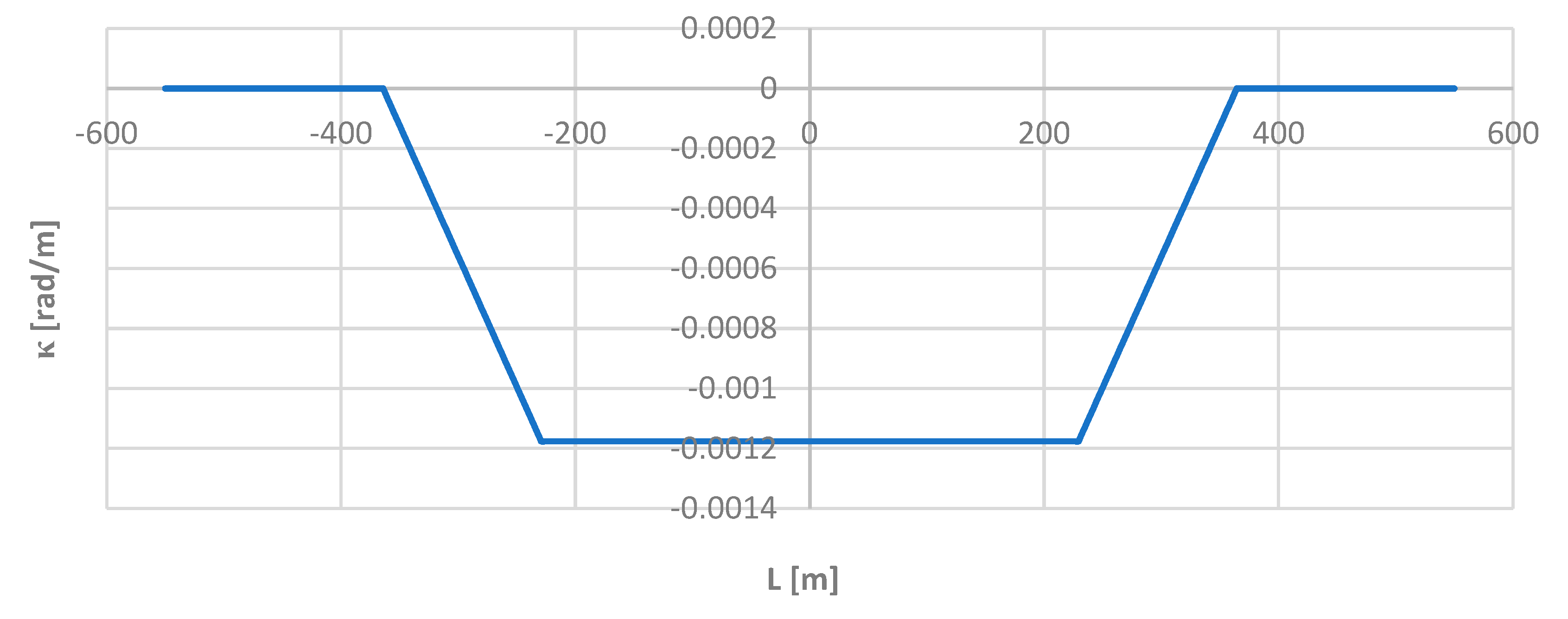

4.4. Reference to the appropriate method for determining the curvature of the railway track axis

It so happens that the angles of inclination of chords occurring in the discussed method are also used in the method of detrmining the curvature of the geometric layout of tracks [

30]. The applicable formula for curvature is:

The chord length lc appearing in the denominator results from the assumption that this is the distance between the points of contact of both chords to the geometric layout (in fact, it should be measured along an arc). As shown, the above assumption can be accepted for the radii of circular arcs used on railway roads.

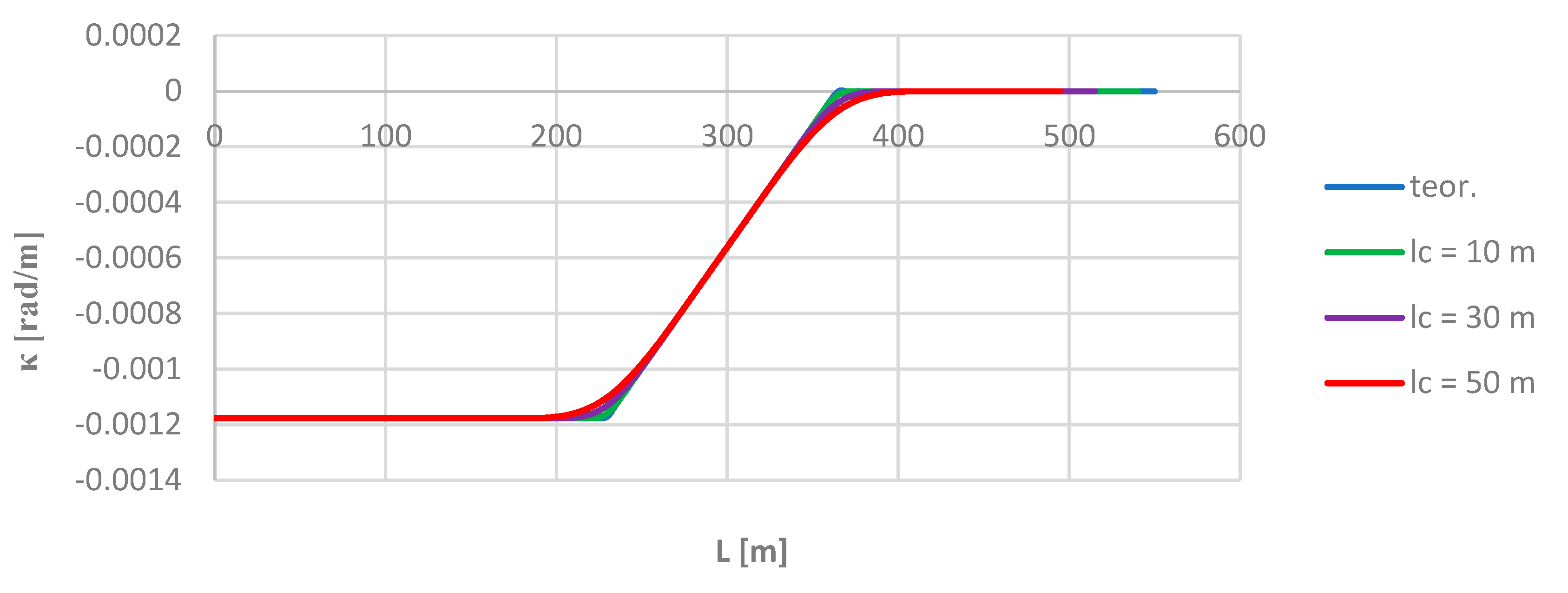

Figure 8 shows a graph of the curvature of the track axis along the length of the model geometric layout, determined using theoretical formulas.

The use of the moving chord method, i.e. formula (15), on the considered length of the model geometric layout (for

) gives – for selected chord values – curvature diagrams shown in

Figure 9.

As you can see, the moving chord method shows full compliance with the theoretical values on a circular arc (on the left in

Figure 9) and on a straight section (on the right). The differences consist in the rounding of the bends in the curveture diagram in the initial and final regions of the transition curve. To highlight them more, the

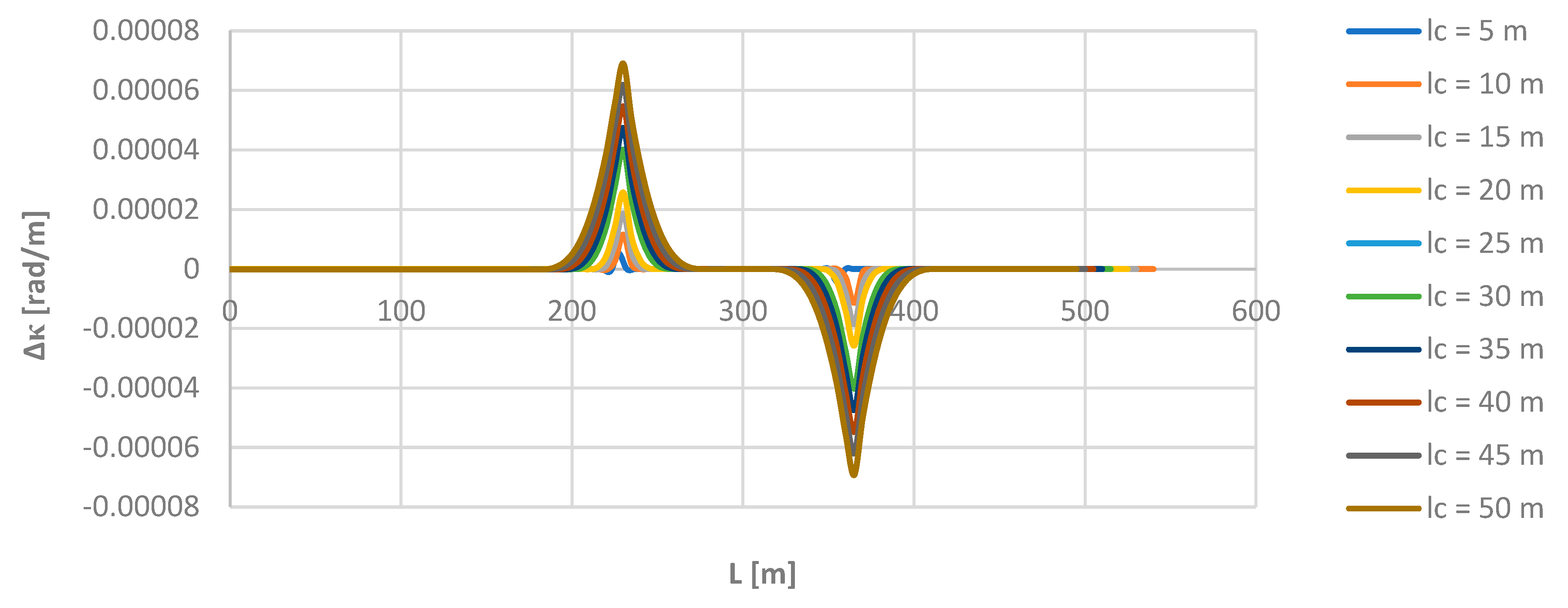

κ values obtained for individual chord lengths were compared with the appropriate theoretical values in the model layout.

Figure 10 shows the graphs of the Δ

κ(

L) relationship for all the used lengths

lc of the moving chord.

The graphs in

Figure 10 show that the differences considered are greater the greater the chord length. The largest values of deviations occur at the beginning and end points of the transition curve. Unlike the situation when determining the directional angle, they may have a relatively greater impact on the obtained curvature values. As stated, for the chord

lc = 50 m, the value of the radius of the circular arc, determined on the basis of curvature, may differ from the theoretical value by even more 50 m.

Hence, it can be concluded that of both variants of the moving chord method, the variant concerning determining the directional angle is much more accurate. The disturbances along the length of the transition curve are completely irrelevant. When determining the curvature, disturbances also occur in the region of the transition curve, and their impact on the final result is more pronounced. This is probably due to the additional simplifying assumption made regarding the distance between the points of contact of both chords to the geometric layout. However, as numerous analyzes have shown, the identified inaccuracies are not significant from the point of view of the inventory process.

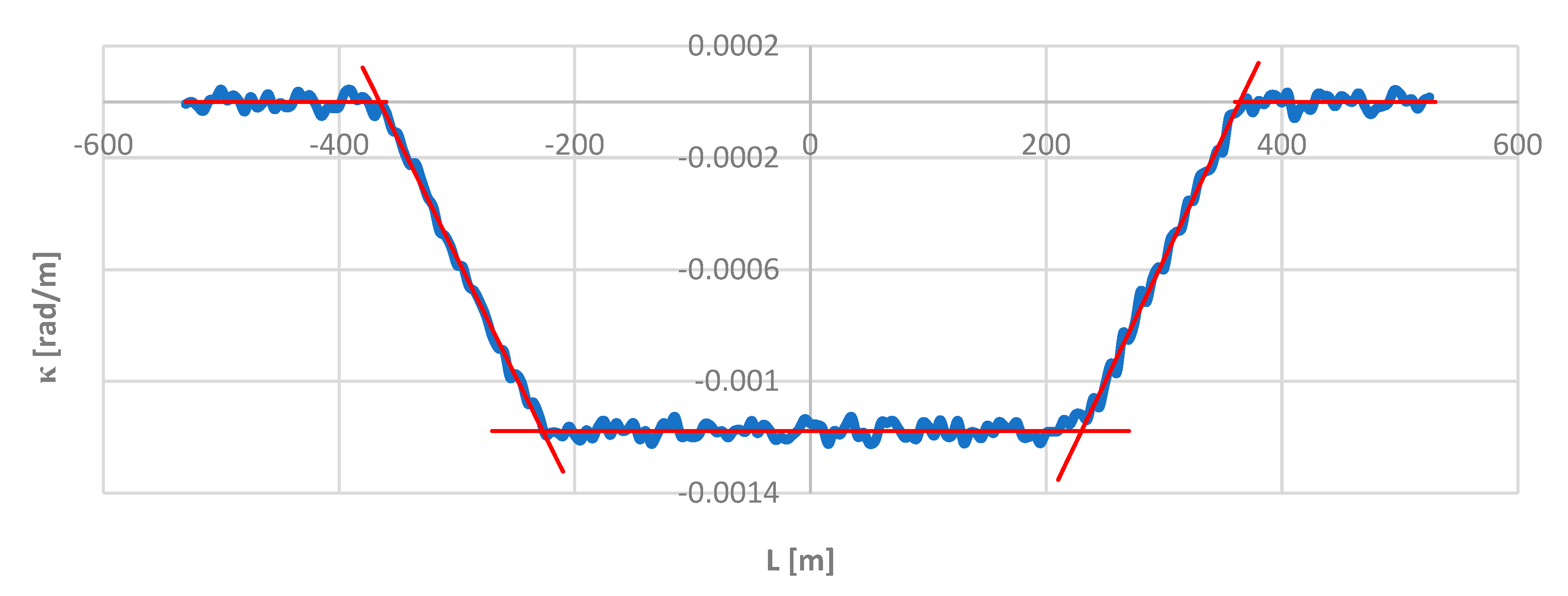

5. Example of determining the directional angle based on measurement data

In order to maintain the possibility of referring to the model geometric layout shown in

Figure 3, it was decided to obtain hypothetical measurement data by virtually deforming this layout. The coordinates of the track axis were randomly corrected at intervals of 5 m, assuming a maximum error of ±10 mm. Determination of the directional angle of the route (as well as the curvature of the track axis) was carried out for a chord length

lc = 20 m.

As it turned out, the obtained directional angle graph for the deformed geometric layout was visually no different from the

Φ(

L) for the model layout shown in

Figure 5. The situation is different in the case of the curvature graph shown in

Figure 11, which clearly differed from the graph in

Figure 8. Despite this, the practical usefulness of the

κ(

L) diagram in

Figure 11 when identifying a layout cannot be disputed. The areas of occurrence of individual geometric elements are marked in red. On straight sections the curvature is zero, on a circular arc it is determined by the arithmetic mean of the curvature values at the measurement points, and on transition curves it is determined by the least squares line. The intersection points of the latter with the horizontal lines determine the beginnings and ends of the transition curves.

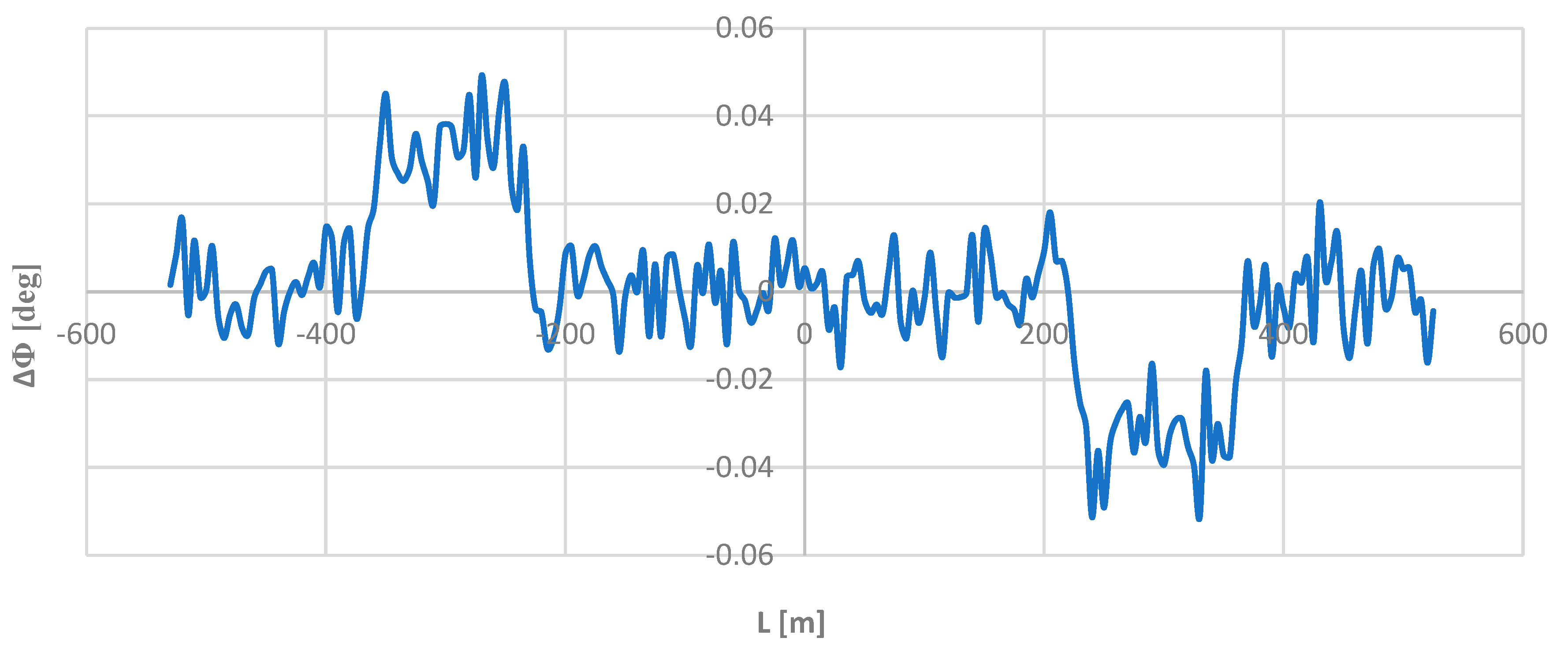

To look for possible differences in the directional angle values, the obtained

Φ values were cpmpared with the appropriate theoretical values in the model geometric layout.

Figure 12 shows the Δ

Φ(

L) dependency graph.

As

Figure 12 shows, these differences do indeed exist. They are oscillatory in nature, but they are very small; on straight sections and on a circular arc they are in the range of

deg, and on transition curves they are in the ranges of

deg and

deg. Compared to the nominal values of the angle

Φ, these are values of a completely different order and for this reason they could not influence – visually – the obtained directional angle graph.

6. Conclusions

The track’s geometric layout is identified based on Cartesian coordinates determined in field measurements. The most effective method of determining these coordinates is mobile satellite measurements. However, there are situations when the satellite signal may be disturbed (due to field obstructions) or completely disappear (e.g. in tunnels). Then the ability to measure the value of the directional angle Φ of the route using the inertial system comes in handy. Knowimg this angle, along with simultaneous measurement of the distance ΔL, allows you to deetrmine the Cartesian coordinates of the next measurement point (knowing the coordinates of the previous point).

The article presents a proposal for a new method for determining the directional angle, referring to the assumptions made in the method of determining the curvature of the railway track axis using a moving chord. This method involves using the values of the inclination angles of two virtual chords derived from a given point forward and backward. An appropriate computational algorithm was presented and the proposed method was verified using the adopted model geometric layout.

Since determining the directional angle of the route on the measurement way involves determining the directional angle of the rail vehicle on which the inertial system was installed, it was necessary to check the influence of the length of the vehicle’s rigid base on the values of the determined directional angle of the route. In a given case, the rigid base is a moving chord used in the proposed method. As it turned out, the moving chord method is fully consistent wuth the reference system determined theoretically for various lengths of the moving chord. Some discrepancies occur only on the transition curve, but they are very small and completely negligible from a practical point of view. This clearly confirms the very high precision of the proposed method for determning the directional angle of the route and the lack of importance of the length of the rigid base of the rail vehicle when measuring this angle using an inertial system.

Comparing the discussed method with a related method for determining the curvature of the track axis (which also uses a moving chord), it can be concluded that of both variants of the moving chord method, the variant regarding determining the directional angle is much more accurate. This is probably due to an additional simplifying assumption made when determining the curvature, regarding the distance between the points of contact of both chords to the geometric layout. However, as numerous analyzes have shown, the identified inaccuracies are not important from the point of view of the inventory process.

In oreder to maintain the possibility of referring to the adopted model geometric layout, it was decided to obtain hypothetical measurement data by virtually deforming this layout in a random manner. As it turned out, the obtained directional angle graph for the deformed layout was visually no different from the Φ(L) graph for the model layout. The deviations occurred were of a completely different order than the nominal values of the angle Φ. The situation was different in the case of the curvature diagram, although its practical usefulness when identifying a geometric layout cannot be disputed.

References

- 883.2000 DB_REF-Festpunktfeld. Deutsche Bahn Netz AG, Berlin, Germany, 2016.

- Railway applications—Track—Track alignment design parameters—Track gauges 1435 mm and wider. Part 1: Plain line. EN 13803-1. European Committee for Standardization (CEN), Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- Code of federal regulations title 49 transportation. Federal Railroad Administration, US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2008.

- NR/L3/TRK/0030 NR_Reinstatement of Absolute Track Geometry (WCRL Routes), Iss. 1. Network Rail, London, UK, 2008.

- Technical Standards – detailed technical conditions for the modernization or construction of railway lines for speed Vmax ≤ 200 km/h (for conventional rolling stock) / 250 km/h (for rolling stock with a tilting box). Volume I – Attachment ST-T1-A6: Geometrical layouts of tracks [in Polish]. Polish State Railways – Polish Railway Lines, 2018, Warszawa, Poland.

- Szwilski, A.B.; Dailey, P.; Sheng, Z.; Begley, R.D. Employing HADGPS to survey track and monitor movement at curves. In Proceedings of The 8th Int. Conf. "Railway Engineering 2005", London, UK, 29th-30th June 2005.

- Specht, C.; Koc, W. Mobile satellite measurements in designing and exploitation of rail roads. Transportation Research Procedia 2016, 14, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A guide to using IMU (accelerometer and gyroscope devices) in embedded applications. Starlino Electronics, 2009. Available online: http://www.starlino.com/imu_guide.html (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Guimarães-Steinicke, C.; Weigelt, A.; Ebeling, A.; Eisenhauer, N.; Duque-Lazo, J.; Reu, B.; Roscher, C.; Schumacher, J.; Wagg, C.; Wirth, C. Terrestrial laser scanning reveals temporal changes in biodiversity mechanisms driving grassland productivity. Advances in Ecological Research 2019, 61, 133–161. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Y.; Lau, L. Development of a trajectory constrained rotating arm rig for testing GNSS kinematic positioning. Measurement 2019, 140, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhao, X.; Pang, C.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.; Zou, K. Improving ambiguity resolution success rate in the joint solution of GNSS-based attitude determination and relative positioning with multivariate constraints. GPS Solution 2020, 24, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation of the Council of Ministers of 15 October 2012 on the national spatial reference system [in Polish]. Journal of Laws 2012, pos. 1247.

- Moritz, H. Geodetic Reference System 1980. Journal of Geodesy 2000, 74, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turiño, C.-E. Gauss Krüger projection for areas of wide longitudinal extent. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2008, 22, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Schonfeld, P. Concurrent optimization of rail transit alignments and station locations. Urban Rail Transit 2016, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Pu, H.; Schonfeld, P.; Song, T.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Peng, X.; Hu, J. Multi-objective railway alignment optimization considering costs and environmental impacts. Applied Soft Computing 2020, 89, 106105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenda, G. Determining the geometrical parameters of exploited rail track using approximating spline functions. Archives of Civil Engineering 2014, 60, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikas, V.; Stratakos, J. A novel geodetic engineering method for accurate and automated road/railway centerline geometry extraction based on the bearing diagram and fractal behawior. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2012, 13, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Li, L.; Wang, K. Automatic horizontal curve identification and measurement using Mobile Mapping System. Journal of Surveying Engineering 2018, 144, 04018007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, S.; Thomson, R.; Lannér, G. Using naturalistic field operational test data to identify horizontal curves. Journal of Transportation Engineering 2012, 138, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellmer, S.; Rapinski, J.; Skala, M.; Palikowska, K. New approach to arc fitting for railway track realignment. Journal of Surveying Engineering 2016, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skala-Szymanska, M.; Cellmer, S.; Rapiński, J. Use of Nelder-Mead simplex method to arc fitting for railway track realignment. In Selected Papers of The 9th International Conference ”ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING”, 22-23 May 2014, Vilnius, Lithuania.

- Song, Z.; Yang, F.; Schonfeld, P.; Li, J.; Pu, H. Heuristic strategies of modified Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm for fitting transition curves. Journal of Surveying Engineering 2020, 146, 04020001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Easa, S. M.; Li, J. Approximate extraction of spiraled horizontal curves from satellite imagery. Journal of Surveying Engineering 2007, 133, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easa, S. M.; Wang, F. Fitting composite horizontal curves using the total least-squares method. Survey Review 2011, 43, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Fang, T.; Schonfeld, P.; Li, J. Effect of point configurations on parameter estimation analysis of circles. Journal of Surveying Engineering 2021, 147, 04021010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Torregrosa, F. J.; Pérez-Zuriaga, A. M.; Campoy-Ungría, J. M.; García, A.; Tarko, A. P. Use of heading direction for recreating the horizontal alignment of an existing road. Computer Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2015, 30, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Pu, H.; Schonfeld, P.; Song, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Peng, X.; Peng, L. A method for automatically recreating the horizontal alignment geometry of existing railways. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2009, 34, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhen, S.; Schonfeld, P.; Pu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Qiu, X.; Wei, F.; Yan, W. Recreating existing railway horizontal alignments automatically using overall swing iteration. Journal of Transportation Engineering: Part A – Systems 2022, 148, 04022046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, W. The procedure of identifying the geometrical layout of an exploited railway route based on the determined curvature of the track axis. Sensors 2023, 23, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koc, W. Design of rail-track geometric systems by satellite measurement. Journal of Transportation Engineering 2012, 138, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, G.A.; Korn, T.M. Mathematical handbook for scientists and engineers. New York: McGraw – Hill Book Company, USA, 1968.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).