Submitted:

10 January 2024

Posted:

11 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- human bocavirus [6],

- coronavirus [5],

- human coronavirus 229E [7],

- human coronavirus (HCoV-NH) NL63[8],

- cytomegalovirus [9],

- Epstein–Barr virus [13],

- human herpesvirus 6[14],

- human lymphotropic virus[15],

- human rhinovirus[5],

- influenza[16],

- measles[17],

- parainfluenza virus type 2[20],

- respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)[21],

- rotavirus[22],

- torque teno virus[25],

- Staphylococcus aureus[26], and

- Bacillus Calmette-Gue’rin (BCG) vaccination [28],

- COVID-19 vaccine Vaxzevria (nonreplicating viral vector)[29],

- Diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (DTaP or DTAP) [30],

- Hepatitis b [31],

- Lanzhou lamb rotavirus vaccine (LLR) and freeze-dried live attenuated hepatitis A vaccine (HAV or HEPA)[35],

- Measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) [30],

- Polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine (Pneumo 23) [33],

- Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV or PNC) [30],

- SARS-CoV-2 [37],

- Yellow fever vaccine [38],

- DTaP/Poliovirus vaccine inactivated (IPV)/ Hepatitis B virus vaccine (HepB or HEP), [39];

- Prevnar 13 (PNC13 or PCV13)

- Rotarix [39],

- DTaP/IPV/Haemophilus B conjugate vaccine (Hib or HIBV)/PCV [40],

- DTaP/IPV/Hib; meningitis C; PCV [40],

- DTaP/IPV; MMR [40],

- DTaP-IPV/Hib and PCV13 [41],

- Hib; meningitis C; PCV; MMR [40],

- Measles/rubella (MR), varicella, pneumococcal [42].

- One report of an adult with both KD and (MIS-A) following second dose of Pfizer SARS-CoV-2 vaccine [37].

The etiology for KD remains unknown.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

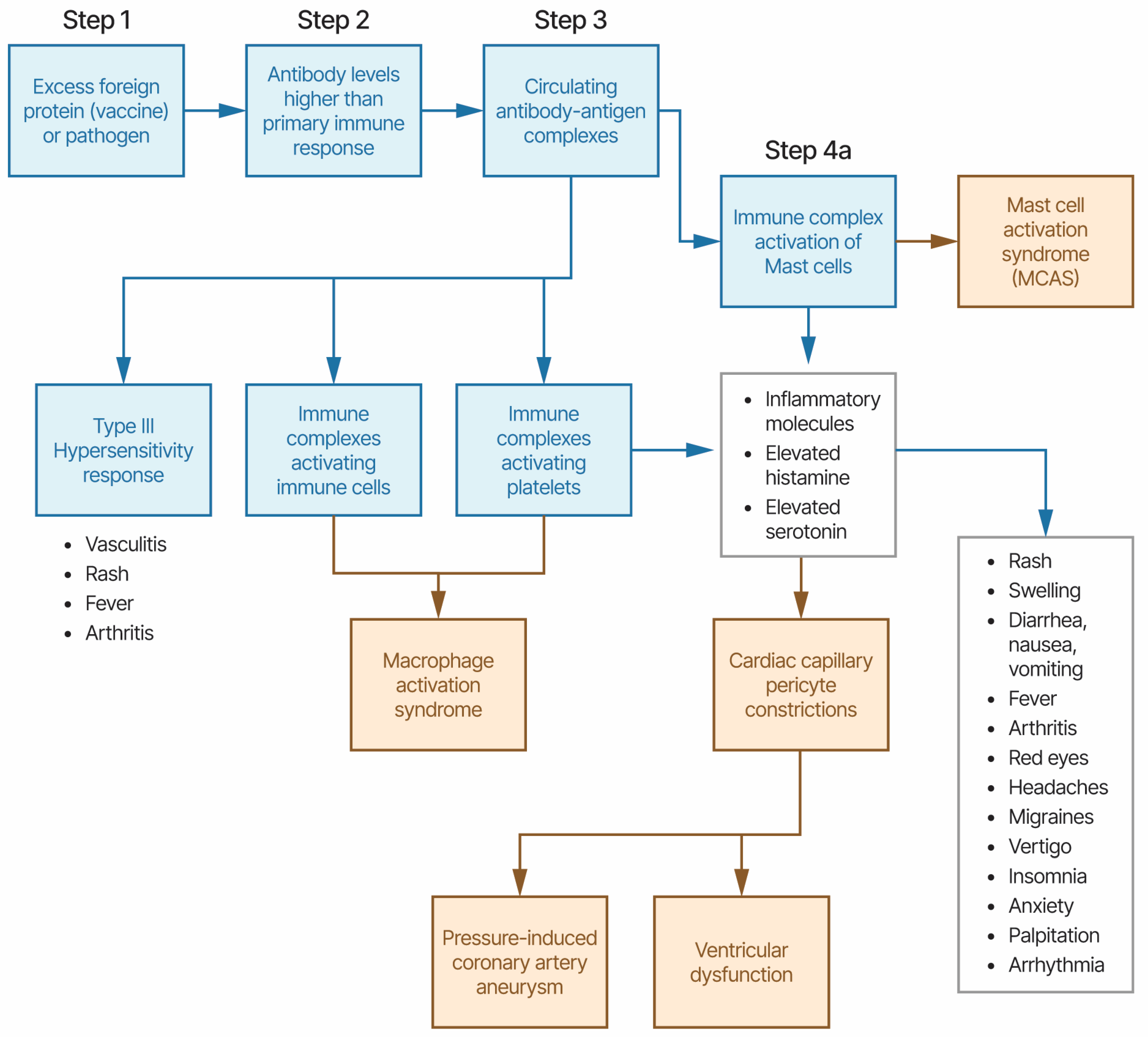

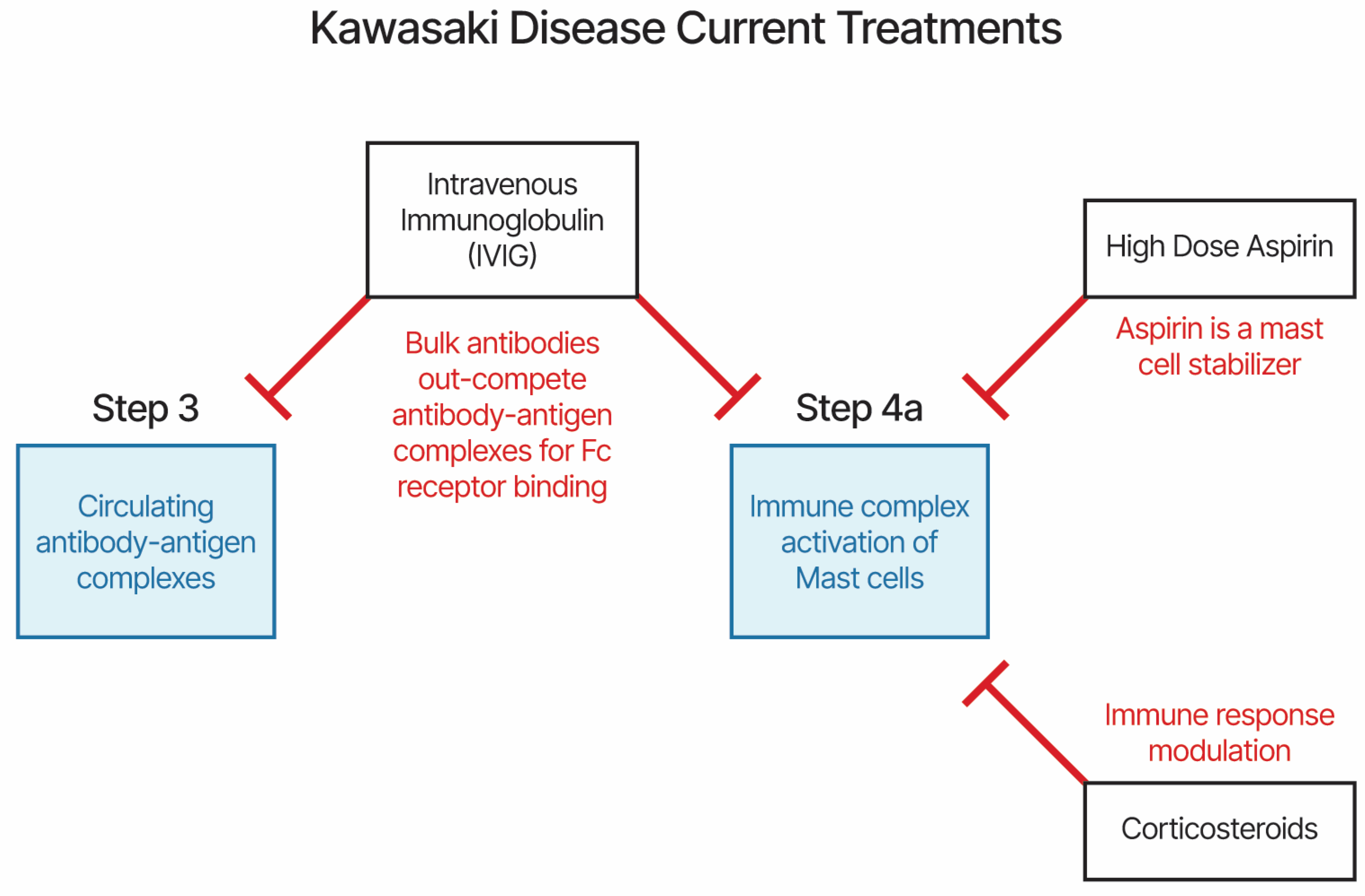

4.1. Kawasaki Disease and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndromes Etiology Model

4.2. KD and MIS Treatments and Etiology Model

4.3. Kawasaki Disease and vaccinations (KD-V)

4.4. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndromes (MIS-C, MIS-A, MIS-N, and MIS-V)

4.5. Henoch-Schönlein purpura and other Vasculitis diseases

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bayer. Aspirin Product Monograh. Available online: https://www.bayer.com/sites/default/files/2020-11/aspirin-pm-en.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Su, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhanghuang, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X. Association between FGA gene polymorphisms and coronary artery lesion in Kawasaki disease. Frontiers in Medicine 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menikou, S.; Langford, P.R.; Levin, M. Kawasaki Disease: The Role of Immune Complexes Revisited. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embil, J.A.; McFarlane, E.S.; Murphy, D.M.; Krause, V.W.; Stewart, H.B. Adenovirus type 2 isolated from a patient with fatal Kawasaki disease. Can Med Assoc J 1985, 132, 1400–1400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.-Y.; Lu, C.-Y.; Shao, P.-L.; Lee, P.-I.; Lin, M.-T.; Fan, T.-Y.; Cheng, A.-L.; Lee, W.-L.; Hu, J.-J.; Yeh, S.-J.; et al. Viral infections associated with Kawasaki disease. J Formos Med Assoc 2014, 113, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano-Pons, C.; Giraud, C.; Rozenberg, F.; Meritet, J.F.; Lebon, P.; Gendrel, D. Detection of human bocavirus in children with Kawasaki disease. Clin Microbiol Infect 2007, 13, 1220–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirato, K.; Imada, Y.; Kawase, M.; Nakagaki, K.; Matsuyama, S.; Taguchi, F. Possible involvement of infection with human coronavirus 229E, but not NL63, in Kawasaki disease. J Med Virol 2014, 86, 2146–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esper, F.; Weibel, C.; Ferguson, D.; Landry, M.L.; Kahn, J.S. Evidence of a Novel Human Coronavirus That Is Associated with Respiratory Tract Disease in Infants and Young Children. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2005, 191, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano-Pons, C.; Quartier, P.; Leruez-Ville, M.; Kaguelidou, F.; Gendrel, D.; Lenoir, G.; Casanova, J.-L.; Bonnet, D. Primary Cytomegalovirus Infection, Atypical Kawasaki Disease, and Coronary Aneurysms in 2 Infants. Clin Infect Dis 2005, 41, e53–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, A.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Mahadevan, S. Kawasaki Disease in a 2-year-old Child with Dengue Fever. Indian J Pediatr 2016, 83, 602–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopontammarak, S.; Promphan, W.; Roymanee, S.; Phetpisan, S. Positive Serology for Dengue Viral Infection in Pediatric Patients With Kawasaki Disease in Southern Thailand. Circ J 2008, 72, 1492–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, K.-P.; Cheng-Chung Wei, J.; Hung, Y.-M.; Huang, S.-H.; Chien, K.-J.; Lin, C.-C.; Huang, S.-M.; Lin, C.-L.; Cheng, M.-F. Enterovirus Infection and Subsequent Risk of Kawasaki Disease: A Population-based Cohort Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2018, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuta, H.; Nakanishi, M.; Ishikawa, N.; Konno, M.; Matsumoto, S. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus sequences in patients with Kawasaki disease by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Intervirology 1992, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, M.; Luka, J.; Thiele, G.M.; Sakiyama, Y.; Matsumoto, S.; Purtilo, D.T. Human herpesvirus 6 infection and Kawasaki disease. J Clin Microbiol 1989, 27, 2379–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, M. Kawasaki Disease and Human Lymphotropic Virus Infection. Curr Med Res Opin 1999, 15, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, A.V.; Jones, K.D.J.; Buckley, A.-M.; Coren, M.E.; Kampmann, B. Kawasaki disease coincident with influenza A H1N1/09 infection. Pediatr Int 2011, 53, e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitby, D.; Hoad, J.G.; Tizard, E.J.; Dillon, M.J.; Weber, J.N.; Weiss, R.A.; Schulz, T.F. Isolation of measles virus from child with Kawasaki disease. Lancet 1991, 338, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, J.M.; Hansen, L.K.; Oxhøj, H. Kawasaki disease associated with parvovirus B19 infection. Eur J Pediatr 1995, 154, 633–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, G.; Krzysztofiak, A.; Porcaro, M.A.; Mango, T.; Zerbini, M.; Gentilomi, G.; Musiani, M. Active or recent parvovirus B19 infection in children with Kawasaki disease. Lancet 1994, 343, 1260–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, D.; Keller, E.; Hirsch, M. Mucocutaneous Lymph-Node Syndrome and Parainfluenza 2 Virus Infection. Lancet 1977, 310, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.B.; Park, S.; Kwon, B.S.; Han, J.W.; Park, Y.W.; Hong, Y.M. Evaluation of the Temporal Association between Kawasaki Disease and Viral Infections in South Korea. Korean Circ J 2014, 44, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, S.; Utagawa, E.; Sugiura, A. Association of Rotavirus Infection with Kawasaki Syndrome. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 1983, 148, 177–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogboli, M.I.; Parslew, R.; Verbov, J.; Smyth, R. Kawasaki disease associated with varicella: a rare association. Br J Dermatol 1999, 141, 1136–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossiva, L.; Papadopoulos, M.; Lagona, E.; Papadopoulos, G.; Athanassaki, C. Myocardial infarction in a 35-day-old infant with incomplete Kawasaki disease and chicken pox. Cardiol Young 2010, 20, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thissen, J.B.; Isshiki, M.; Jaing, C.; Nagao, Y.; Lebron Aldea, D.; Allen, J.E.; Izui, M.; Slezak, T.R.; Ishida, T.; Sano, T. A novel variant of torque teno virus 7 identified in patients with Kawasaki disease. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0209683–e0209683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.; Hoyt, L.; Ferrieri, P.; Schlievert, P.M.; Jenson, H.B. Kawasaki Syndrome-Like Illness Associated with Infection Caused by Enterotoxin B-Secreting Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis 1999, 29, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinomiya, N.; Takeda, T.; Kuratsuji, T.; Takagi, K.; Kosaka, T.; Tatsuzawa, O.; Tsurumizu, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Kobayashi, N. Variant Streptococcus sanguis as an etiological agent of Kawasaki disease. Prog Clin Biol Res 1987, 250, 571–572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Banday, A.Z.; Patra, P.K.; Jindal, A.K. Kawasaki disease – when Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) lymphadenitis blooms again and the vaccination site peels off! International Journal of Dermatology 2021, 60, e233–e234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta-Amaro, A.L.; Tejada-Ruiz, M.I.; Rivera-Alvarado, K.L.; Cobos-Quevedo, O.D.; Romero-Hernández, P.; Macías-Arroyo, W.; Avendaño-Ponce, A.; Hurtado-Díaz, J.; Vera-Lastra, O.; Lucas-Hernández, A. Atypical Kawasaki Disease after COVID-19 Vaccination: A New Form of Adverse Event Following Immunization. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsager, K.; Khatri Vadlamudi, N.; Jadavji, T.; Bettinger, J.A.; Constantinescu, C.; Vaudry, W.; Tan, B.; Sauvé, L.; Sadarangani, M.; Halperin, S.A.; et al. Kawasaki disease following immunization reported to the Canadian Immunization Monitoring Program ACTive (IMPACT) from 2013 to 2018. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2022, 18, 2088215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, D.; Fink, D.; Hashkes, P.J. Kawasaki disease in an infant following immunisation with hepatitis B vaccine. Clin Rheumatol 2003, 22, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.W.; Kim, D.H.; Han, M.Y.; Cha, S.H.; Yoon, K.L. An infant presenting with Kawasaki disease following immunization for influenza: A case report. Biomed Rep 2018, 8, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraszewska-Głomba, B.; Kuchar, E.; Szenborn, L. Three episodes of Kawasaki disease including one after the Pneumo 23 vaccine in a child with a family history of Kawasaki disease. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 2016, 115, 885–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, S.; Watanabe, T.; Sato, S. A Patient with Kawasaki Disease Following Influenza Vaccinations. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; Liubao, P.; Chongqing, T.; Xiaomin, W. The first case of Kawasaki disease in a 20-month old baby following immunization with rotavirus vaccine and hepatitis A vaccine in China: A case report. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2015, 11, 2740–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-T.; Juan, Y.-C.; Liu, C.-H.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Chan, K.A. Intussusception and Kawasaki disease after rotavirus vaccination in Taiwanese infants. Vaccine 2020, 38, 6299–6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Showers, C.R.; Maurer, J.M.; Khakshour, D.; Shukla, M. Case of adult-onset Kawasaki disease and multisystem inflammatory syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. BMJ Case Reports 2022, 15, e249094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmöeller, D.; Keiserman, M.W.; Staub, H.L.; Velho, F.P.; de Fátima Grohe, M. Yellow Fever Vaccination and Kawasaki Disease. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2009, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Islam, S. Kawasaki disease and vasculitis associated with immunization. Pediatrics International 2018, 60, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.C.; Tulloh, R.M.R.; Tulloh, L.E. The incidence of Kawasaki disease after vaccination within the UK pre-school National Immunisation Programme: an observational THIN database study. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2016, 25, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ece, I.; Akbayram, S.; Demiroren, K.; Uner, A. Is Kawasaki Disease a Side Effect of Vaccination as Well? J Vaccines Vaccin 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, D.; Minami, T.; Seki, M.; Tamura, D.; Yamagata, T. Occurrence of Kawasaki disease after simultaneous immunization. Pediatrics International 2019, 61, 1171–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rose, D.U.; Pugnaloni, F.; Calì, M.; Ronci, S.; Caoci, S.; Maddaloni, C.; Martini, L.; Santisi, A.; Dotta, A.; Auriti, C. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Neonates Born to Mothers with SARS-CoV-2 Infection (MIS-N) and in Neonates and Infants Younger Than 6 Months with Acquired COVID-19 (MIS-C): A Systematic Review. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, D.; Goyal, M.; Haribalakrishna, A.; Nanavati, R.; Ish, P.; Kunal, S. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates (MIS-N): a systematic review. European Journal of Pediatrics 2023, 182, 2283–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, C.; Moretta, G.; Bersani, G.; Valentini, P.; Gatto, A.; Rigante, D. Epstein-Barr virus-related cutaneous necrotizing vasculitis in a girl heterozygous for factor V Leiden. J Dermatol Case Rep 2017, 11, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcu, K.; Sila, Y.; Deniz, a.; Pembe, G.l.G.n.; Sirin, G.v.; Ismail, I. Henoch-schonlein purpura associated with primary active epstein barr virus infection: a case report. PAMJ 2017, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.j. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of Henoch-Schonlein purpura associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13, e2021064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Shariff, M.; Al Hillan, A.; Haj, R.A.; Kaunzinger, C.; Hossain, M.; Asif, A.; Pyrsopoulos, N.T. A Rare Case of Helicobacter pylori Infection Complicated by Henoch-Schonlein Purpura in an Adult Patient. Journal of Medical Cases; Vol. 11, No. 6, Jun 2020.

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; Dong, L.; Feng, S.; Wang, Z. Parainfluenza infection is associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children. Pediatric Infectious Disease 2016, 8, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamela F, W.; Andrew J, K.; Xianqun, L.; Chris, F. Temporal Association of Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Parainfluenza Pediatric Hospitalizations and Hospitalized Cases of Henoch-Schönlein Purpura. The Journal of Rheumatology 2010, 37, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraldi, S.; Mancuso, R.; Rizzitelli, G.; Gianotti, R.; Ferrante, P. Henoch-Schönlein syndrome associated with human Parvovirus B19 primary infection. Eur J Dermatol 1999, 9, 232–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veraldi, S.; Rizzitelli, G. Henoch-Schönlein Purpura and Human Parvovirus B19. Dermatology 2009, 189, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioc, A.M.; Sedmak, D.D.; Nuovo, G.J.; Dawood, M.R.; Smart, G.; Magro, C.M. Parvovirus B19 associated adult Henoch Schönlein purpura. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology 2002, 29, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, S.; İbrahim Aydın, H.; Atay, A. Henoch-Schönlein Purpura in a Child Following Varicella. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 2005, 51, 240–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariko, M.; Yoriaki, K.; Tomohiro, W.; Masatoshi, K. Purpura-free small intestinal IgA vasculitis complicated by cytomegalovirus reactivation. BMJ Case Reports 2020, 13, e235042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, H.; Miyakawa, H. Henoch Schönlein Purpura Nephritis Associated with Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) Therapy. Internal Medicine 2017, 56, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jariwala, S.; Vernon, N.; Shliozberg, J. Henoch-Schönlein purpura after hepatitis A vaccination. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2011, 107, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, A.; McGregor, D.; Searle, M.; Irvine, J.; Cross, N. Henoch–Schönlein purpura in a renal transplant recipient with prior IgA nephropathy following influenza vaccination. Clinical Kidney Journal 2013, 6, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T. Henoch-Schönlein purpura following influenza vaccinations during the pandemic of influenza A (H1N1). Pediatric Nephrology 2011, 26, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, U.; Bradley, J.R.; Hamilton, D.V. Henoch-Schönlein purpura after influenza vaccination. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988, 296, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantor, R.; Galel, A.; Aviner, S. Henoch-Schönlein Purpura Post-Influenza Vaccination in a Pediatric Patient: A Rare but Possible Adverse Reaction to Vaccine. Isr Med Assoc J 2020, 22, 654–656. [Google Scholar]

- Da Dalt, L.; Zerbinati, C.; Strafella, M.S.; Renna, S.; Riceputi, L.; Di Pietro, P.; Barabino, P.; Scanferla, S.; Raucci, U.; Mores, N.; et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura and drug and vaccine use in childhood: a case-control study. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2016, 42, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, P.A.; Patterson, R.N.; Lee, R.J.E. Henoch–Schönlein purpura following meningitis C vaccination. Rheumatology 2001, 40, 345–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.-G.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, S.; Hu, Q.; Fang, Y. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis for a male with severe Henoch Schönlein purpura following rabies vaccination. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2018, 14, 2666–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanis, R.; Thomas, B.; Amel, B.; Léa, D.; Kladoum, N.; Kevin, D.; Carle, P.; Eric, L.; Ashley, T.; Gaëlle, R.-C.; et al. IgA Vasculitis Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A French Multicenter Case Series Including 12 Patients. The Journal of Rheumatology 2023, 50, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, A.M.; Murphy, N.; Mullin, C.; Barillas, J.; Barrientos, J.C. Henoch-Schönlein purpura presenting post COVID-19 vaccination. Vaccine 2021, 39, 4571–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, M.E.; Appel, G.; Little, A.J.; Ko, C.J. Post-COVID-19 vaccination IgA vasculitis in an adult. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology 2022, 49, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirufo, M.M.; Raggiunti, M.; Magnanimi, L.M.; Ginaldi, L.; De Martinis, M. Henoch-Schönlein Purpura Following the First Dose of COVID-19 Viral Vector Vaccine: A Case Report. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naitlho, A.; Lahlou, W.; Bourial, A.; Rais, H.; Ismaili, N.; Abousahfa, I.; Belyamani, L. A Rare Case of Henoch-Schönlein Purpura Following a COVID-19 Vaccine—Case Report. SN Compr Clin Med 2021, 3, 2618–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, F.; Magenes, V.C.; De Sanctis, M.; Gattinara, M.; Pandolfi, M.; Cambiaghi, S.; Zuccotti, G.V.; Fabiano, V. Henoch-Schönlein purpura following COVID-19 vaccine in a child: a case report. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2022, 48, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanis, R.; Jean Marc, G.; Jean François, A.; Eva, D.; Laurent, P.; Nicole, F.; Adrien, B.; Julie, M.; Stéphanie, J.; Elisabeth, D.; et al. Immunoglobulin A Vasculitis Following COVID-19: A French Multicenter Case Series. The Journal of Rheumatology 2022, 49, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetto, C.; Trotta, F.; Felicetti, P.; Alarcón, G.S.; Santuccio, C.; Bachtiar, N.S.; Brauchli Pernus, Y.; Chandler, R.; Girolomoni, G.; Hadden, R.D.M.; et al. Vasculitis as an adverse event following immunization – Systematic literature review. Vaccine 2016, 34, 6641–6651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikenes, K.; Farstad, M.; Nordrehaug, J.E. Serotonin Is Associated with Coronary Artery Disease and Cardiac Events. Circulation 1999, 100, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino, P.; Piscione, F.; Willerson, J.T.; Cappelli-Bigazzi, M.; Focaccio, A.; Villari, B.; Indolfi, C.; Russolillo, E.; Condorelli, M.; Chiariello, M. Divergent Effects of Serotonin on Coronary-Artery Dimensions and Blood Flow in Patients with Coronary Atherosclerosis and Control Patients. New England Journal of Medicine 1991, 324, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuman, T.C.; Tuman, B.; Polat, M.; Çakır, U. Urticaria and Angioedema Associated with Fluoxetine. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2017, 15, 418–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, H.H.; Laidlaw, P.P. The physiological action of β-iminazolylethylamine. The Journal of Physiology 1910, 41, 318–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, A.A.; Levi, R. Histamine and cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation Research 1986, 58, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maintz, L.; Novak, N. Histamine and histamine intolerance2. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007, 85, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, M.; Holland, P.C.; Nokes, T.J.; Novelli, V.; Mola, M.; Levinsky, R.J.; Dillon, M.J.; Barratt, T.M.; Marshall, W.C. Platelet immune complex interaction in pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease and childhood polyarteritis. British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed.) 1985, 290, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, L.; Campbell, M.J.; Wu, E.Y. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and Kawasaki Disease: Parallels in Pathogenesis and Treatment. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 2023, 23, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocatürk, B.; Lee, Y.; Nosaka, N.; Abe, M.; Martinon, D.; Lane, M.E.; Moreira, D.; Chen, S.; Fishbein, M.C.; Porritt, R.A.; et al. Platelets exacerbate cardiovascular inflammation in a murine model of Kawasaki disease vasculitis. JCI Insight 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-y.; Xiao, M.; Zhou, D.; Yan, F.; Zhang, Y. Platelet and ferritin as early predictive factors for the development of macrophage activation syndrome in children with Kawasaki disease: A retrospective case-control study. Front Pediatr 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricke, D.O.; Gherlone, N.; Fremont-Smith, P.; Tisdall, P.; Fremont-Smith, M. Kawasaki Disease, Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children: Antibody-Induced Mast Cell Activation Hypothesis. J Pediatrics & Pediatr Med 2020, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Longden, T.A.; Zhao, G.; Hariharan, A.; Lederer, W.J. Pericytes and the Control of Blood Flow in Brain and Heart. Annual Review of Physiology 2023, 85, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S.A.; Andreeva, E.R.; Eremin, I.I.; Markin, A.M.; Nadelyaeva, I.I.; Orekhov, A.N.; Melnichenko, A.A. The Role of Pericytes in Regulation of Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Farrell, F.M.; Mastitskaya, S.; Hammond-Haley, M.; Freitas, F.; Wah, W.R.; Attwell, D. Capillary pericytes mediate coronary no-reflow after myocardial ischaemia. Elife 2017, 6, e29280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Tan, B.; Yu, D.-Y.; Balaratnasingam, C. Differentiating Microaneurysm Pathophysiology in Diabetic Retinopathy Through Objective Analysis of Capillary Nonperfusion, Inflammation, and Pericytes. Diabetes 2022, 71, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avolio, E.; Carrabba, M.; Milligan, R.; Kavanagh Williamson, M.; Beltrami, Antonio P.; Gupta, K.; Elvers, Karen T.; Gamez, M.; Foster, Rebecca R.; Gillespie, K.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein disrupts human cardiac pericytes function through CD147 receptor-mediated signalling: a potential non-infective mechanism of COVID-19 microvascular disease. Clinical Science 2021, 135, 2667–2689. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liao, J.; Fan, X.; Xu, M. Exploring the diagnostic value of eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratio to differentiate Kawasaki disease from other febrile diseases based on clinical prediction model. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; DeCuir, J.; Abrams, J.; Campbell, A.P.; Godfred-Cato, S.; Belay, E.D. Clinical Characteristics of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults: A Systematic Review. JAMA Network Open 2021, 4, e2126456–e2126456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, J.B.; Jackson, J.M. Kawasaki Disease and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children: An Overview and Comparison. Am Fam Physician 2021, 104, 244–252. [Google Scholar]

- Dufort, E.M.; Koumans, E.H.; Chow, E.J.; Rosenthal, E.M.; Muse, A.; Rowlands, J.; Barranco, M.A.; Maxted, A.M.; Rosenberg, E.S.; Easton, D.; et al. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children in New York State. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldstein, L.R.; Rose, E.B.; Horwitz, S.M.; Collins, J.P.; Newhams, M.M.; Son, M.B.F.; Newburger, J.W.; Kleinman, L.C.; Heidemann, S.M.; Martin, A.A.; et al. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in U.S. Children and Adolescents. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Wei, L.; Jiao, F.; Pjetraj, D.; Feng, J.; Wang, J.; Catassi, C.; Gatti, S. Very early onset of coronary artery aneurysm in a 3-month infant with Kawasaki disease: a case report and literature review. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2023, 49, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuda, K.; Kiyomatsu, K.; Teramachi, Y.; Suda, K. A case of incomplete Kawasaki disease – A 2-month-old infant with 1 day of fever who developed multiple arterial aneurysms. Annals of Pediatric Cardiology 2022, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Hamwi, S.; Alebaji, M.B.; Mahboub, A.E.; Alkaabi, E.H.; Alkuwaiti, N.S. Multiple Systemic Arterial Aneurysms in Kawasaki Disease. Cureus 2023, 15, e42714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawar, R.; Gavade, V.; Patil, N.; Mali, V.; Girwalkar, A.; Tarkasband, V.; Loya, S.; Chavan, A.; Nanivadekar, N.; Shinde, R.; et al. Neonatal Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome (MIS-N) Associated with Prenatal Maternal SARS-CoV-2: A Case Series. Children 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Cai, J.; Lu, J.; Wang, M.; Yang, C.; Zeng, Z.; Tang, Q.; Li, J.; Tang, W.; Luo, H.; et al. The therapeutic window of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and its correlation with clinical outcomes in Kawasaki disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2023, 49, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rife, E.; Gedalia, A. Kawasaki Disease: an Update. Current Rheumatology Reports 2020, 22, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, E.; Bamford, A.; Kenny, J.; Kaforou, M.; Jones, C.E.; Shah, P.; Ramnarayan, P.; Fraisse, A.; Miller, O.; Davies, P.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of 58 Children With a Pediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome Temporally Associated With SARS-CoV-2. JAMA 2020, 324, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nune, A.; Iyengar, K.P.; Goddard, C.; Ahmed, A.E. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in an adult following the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (MIS-V). BMJ case reports 2021, 14, e243888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, K.P.; Nune, A.; Ish, P.; Botchu, R.; Shashidhara, M.K.; Jain, V.K. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (MIS-V), to interpret with caution. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2021, postgradmedj-2021-140869. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, B.J.; Rhim, J.W.; Lee, S.-Y.; Jeong, D.C. Comparison of COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and Kawasaki disease shock syndrome: case reports and literature review. J Rheum Dis 2023, 30, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinkovits, G.; Schnur, J.; Hurler, L.; Kiszel, P.; Prohászka, Z.Z.; Sík, P.; Kajdácsi, E.; Cervenak, L.; Maráczi, V.; Dávid, M.; et al. Evidence, detailed characterization and clinical context of complement activation in acute multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 19759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartsch, Y.C.; Wang, C.; Zohar, T.; Fischinger, S.; Atyeo, C.; Burke, J.S.; Kang, J.; Edlow, A.G.; Fasano, A.; Baden, L.R.; et al. Humoral signatures of protective and pathological SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Nature Medicine 2021, 27, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, L.A.; Rowley, A.H. Current Insights Into the Pathophysiology of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. Current Pediatrics Reports 2021, 9, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, B.J.; Cho, K.-S.; Rhim, J.W.; Lee, S.-Y.; Jeong, D.C. Similarities and Differences between Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) and Kawasaki Disease Shock Syndrome. Children 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noval Rivas, M.; Arditi, M. Kawasaki Disease and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children: Common Inflammatory Pathways of Two Distinct Diseases. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America 2023, 49, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufnagel, M.; Armann, J.; Jakob, A.; Doenhardt, M.; Diffloth, N.; Hospach, A.; Schneider, D.T.; Trotter, A.; Roessler, M.; Schmitt, J.; et al. A comparison of pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporarily-associated with SARS-CoV-2 and Kawasaki disease. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vaccine Code | Vaccine Name | Shots age 0-5 | All | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6VAX-F | Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis adsorbed + inactivated poliovirus + hepatitis B + haemophilus B conjugate vaccine | 4,092 | 68 | 1,662 |

| BCG | Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine | 241 | 5 | 2,075 |

| COVID19 | Coronavirus 2019 vaccine | 7,267 | 54 | 743 |

| DTAP | Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine | 55,155 | 57 | 103 |

| DTAPHEPBIP | Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine + hepatitis B + inactivated poliovirus vaccine | 11,606 | 41 | 353 |

| DTAPIPV | Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine + inactivated poliovirus vaccine | 10,939 | 15 | 137 |

| DTAPIPVHIB | Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine + inactivated poliovirus vaccine + haemophilus B conjugate vaccine | 10,861 | 55 | 506 |

| DTP | Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pertussis vaccine | 21,679 | 11 | 51 |

| DTPIPV | Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, pediatric + inactivated poliovirus vaccine | 504 | 10 | 1,984 |

| FLU3 | Influenza virus vaccine, trivalent | 9,145 | 7 | 77 |

| FLU4 | Influenza virus vaccine, quadrivalent | 5,270 | 14 | 266 |

| FLUX | Influenza virus vaccine, unknown manufacturer | 2,181 | 18 | 825 |

| HBHEPB | Haemophilus B conjugate vaccine + hepatitis B | 5,236 | 8 | 153 |

| HEP | Hepatitis B virus vaccine | 20,648 | 58 | 281 |

| HEPA | Hepatitis A vaccine | 18,061 | 30 | 166 |

| HIBV | Haemophilus B conjugate vaccine | 52,928 | 126 | 238 |

| IPV | Poliovirus vaccine inactivated | 36,648 | 44 | 120 |

| MEN | Meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine | 1,239 | 16 | 1,291 |

| MENB | Meningococcal group b vaccine, rDNA absorbed | 2,790 | 91 | 3,262 |

| MMR | Measles, mumps and rubella virus vaccine, live | 59,053 | 64 | 108 |

| MMRV | Measles, mumps, rubella and varicella vaccine live | 11,873 | 11 | 93 |

| PNC | Pneumococcal 7-valent conjugate vaccine | 26,198 | 107 | 408 |

| PNC13 | Pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine | 23,510 | 160 | 681 |

| PPV | Pneumococcal vaccine, polyvalent | 4,573 | 16 | 350 |

| RV1 | Rotavirus vaccine, live, oral | 7,858 | 79 | 1,005 |

| RV5 | Rotavirus vaccine, live, oral, pentavalent | 16,921 | 104 | 615 |

| RVX | Rotavirus (no brand name) | 1,398 | 6 | 429 |

| TYP | Typhoid vaccine | 233 | 6 | 2,575 |

| UNK | Unknown vaccine type | 2,840 | 24 | 845 |

| VARCEL | Varivax-varicella virus live | 43,062 | 31 | 72 |

| Onset Day | PNC13* | HIBV | PNC | RV5 | MENB | RV1 | 6VAX-F | MMR | HEP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 41 | 31 | 20 | 16 | 39 | 23 | 15 | 24 | 9 |

| 0 | 23 | 17 | 19 | 11 | 13 | 4 | 15 | 3 | 5 |

| 1 | 23 | 28 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 11 |

| 2 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 6 | |

| 3 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| 4 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| 8 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 9 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 12 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 13 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 14 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | |||

| 15 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 17 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 19 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 20 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| 21 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 22 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 23 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 24 | 1 | ||||||||

| 25 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 26 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| 27 | 1 | ||||||||

| 28 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| 29 | 1 | ||||||||

| 30 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Organ system | Symptoms | Kawasaki Disease | Kawasaki Disease Shock Syndrome | Multisystem Inflammatory Syndromes | Mast cells Activation Syndrome | Type III Hypersensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | Swelling of lips | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Swelling of tongue, strawberry tongue | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Swelling of throat, eustachian tube, glottis | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Enlarged lymph nodes/ lymphadenopathy | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Fever | Persistent fever | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Gastrointestinal | Diarrhea | Yes | Yes | |||

| Abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Nausea | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Emesis/vomiting | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Neurological | Headache/migraine | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Itchy, watery, red/conjunctivitis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Circulatory/ cardiovascular | Chest pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Vasculitis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Coronary artery aneurysms | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Myocarditis | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Integumentary (skin) | Pruritus (itchy skin) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Flushing/redness/erythema | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Urticaria/hives/rash | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Swelling of hands and feet | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age | Kawasaki | MIS-C | KD, MIS, MIS-A, or MIS-C | Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Vasculitis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N.A. | 420 | 71 | 578 | 233 | 667 |

| 0 | 689 | 0 | 689 | 104 | 169 |

| 1 | 169 | 6 | 174 | 80 | 116 |

| 2 | 31 | 0 | 31 | 31 | 29 |

| 3 | 19 | 2 | 21 | 33 | 13 |

| 4 | 14 | 1 | 14 | 81 | 27 |

| 5 | 8 | 11 | 18 | 96 | 22 |

| 6 | 8 | 5 | 13 | 35 | 8 |

| 7 | 4 | 17 | 21 | 26 | 13 |

| 8 | 1 | 10 | 11 | 28 | 6 |

| 9 | 4 | 13 | 17 | 18 | 6 |

| 10 | 1 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 0 |

| 11 | 2 | 10 | 13 | 26 | 6 |

| 12 | 5 | 20 | 24 | 32 | 25 |

| 13 | 3 | 15 | 17 | 25 | 20 |

| 14 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 26 | 8 |

| 15 | 1 | 11 | 12 | 21 | 14 |

| 16 | 2 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 16 |

| 17 | 2 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 18 |

| 18 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 22 |

| 19 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 11 |

| 20 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 16 |

| Age | KD, MIS, MIS-A, or MIS-C | Vaccinations | Frequency/100K |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 851 | 352 |

| 2 | 2 | 826 | 242 |

| 3 | 2 | 865 | 231 |

| 4 | 1 | 1,071 | 93 |

| 5 | 11 | 2,751 | 399 |

| 6 | 6 | 1,921 | 312 |

| 7 | 19 | 2,117 | 897 |

| 8 | 10 | 2,194 | 455 |

| 9 | 16 | 2,417 | 661 |

| 10 | 13 | 2,687 | 483 |

| 11 | 11 | 3,950 | 278 |

| 12 | 22 | 6,136 | 358 |

| 13 | 16 | 4,862 | 329 |

| 14 | 7 | 5,306 | 131 |

| 15 | 11 | 6,410 | 171 |

| 16 | 11 | 8,329 | 132 |

| 17 | 14 | 10,274 | 136 |

| 18 | 3 | 7,237 | 41 |

| 19 | 3 | 7,497 | 40 |

| 20 | 4 | 8,321 | 48 |

| 21 | 2 | 8,716 | 22 |

| 22 | 3 | 9,445 | 31 |

| 23 | 1 | 10,291 | 9 |

| 24 | 2 | 10,985 | 18 |

| 25 | 1 | 11,912 | 8 |

| 26 | 0 | 12,456 | <8 |

| 27 | 1 | 13,197 | 7 |

| 28 | 2 | 13,813 | 14 |

| 29 | 1 | 14,700 | 7 |

| 30 | 0 | 16,084 | <6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).