Submitted:

04 January 2024

Posted:

11 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Bioethics and Informed consent

2.3. Design of the Study

2.4. Content analysis criteria

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Assessing the psycho-emotional state dynamics in astronauts through their communication analysis during a long-term flight

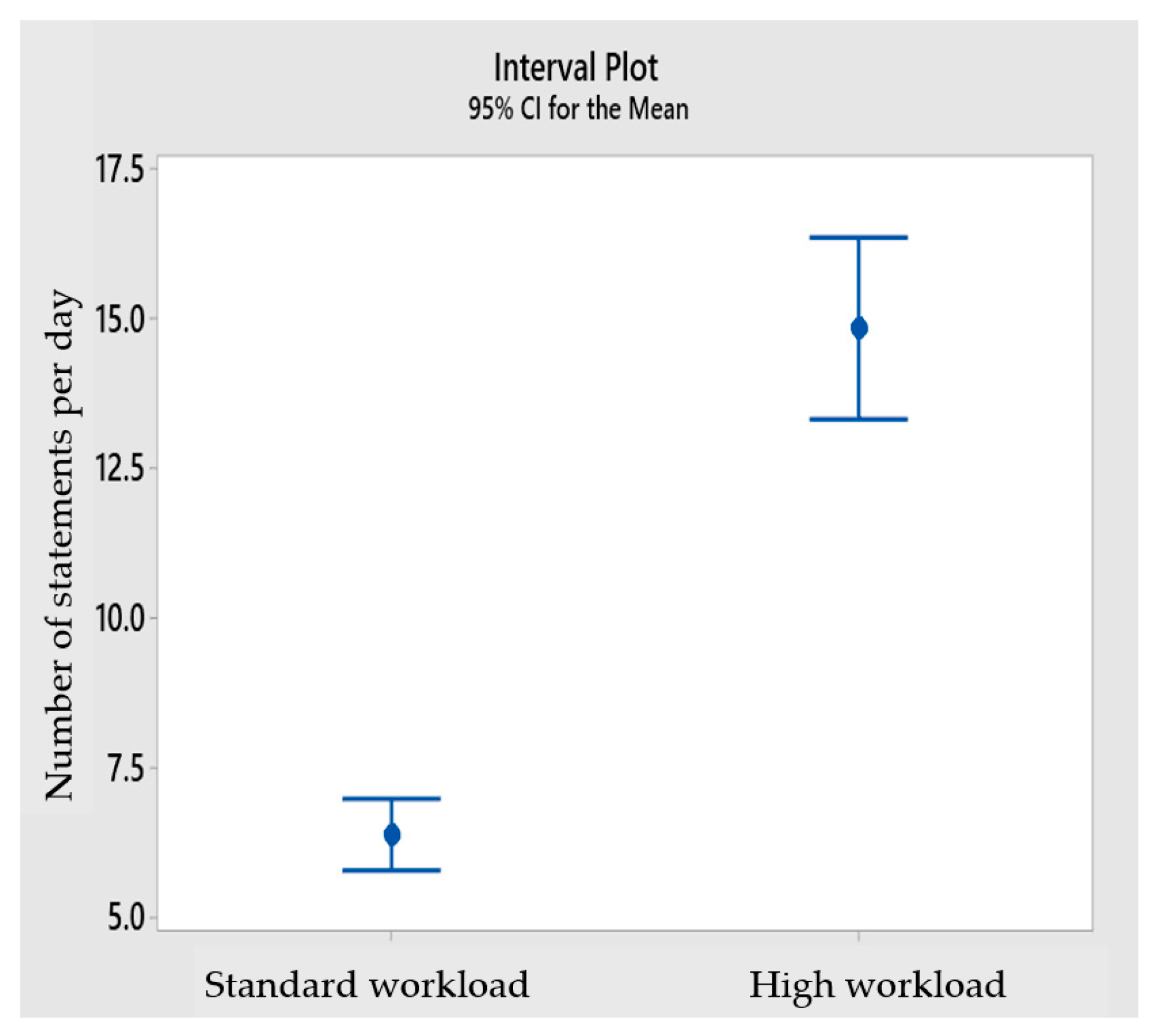

3.1.1. The influence of workload levels, critical flight periods and significant events on the structure of crew communication

- Days with a standard workload: these are weekdays and weekends on which the volume of planned work remained within the limits allowed by regulations, and work activities on which did not require any additional effort from the astronaut.

- Days with a high workload were:

- Days of docking and undocking of manned and cargo transport ships, as well as three days before and after these events, when additional work was carried out to unload and load the ship;

- Days of extravehicular activity, as well as the days preceding and following the event (when equipment and spacesuits are being prepared and loaded, unloaded, spacesuits were dried, etc.);

- Days on which accidents and breakdowns occurred that required an immediate response from crew members and/or a shift in the astronaut’s work schedule due (for example, reducing time for meals or performing night work);

- Scheduled work on weekends or holidays, that required more time than supposed by the norms allowed by regulations (3,5 hours).

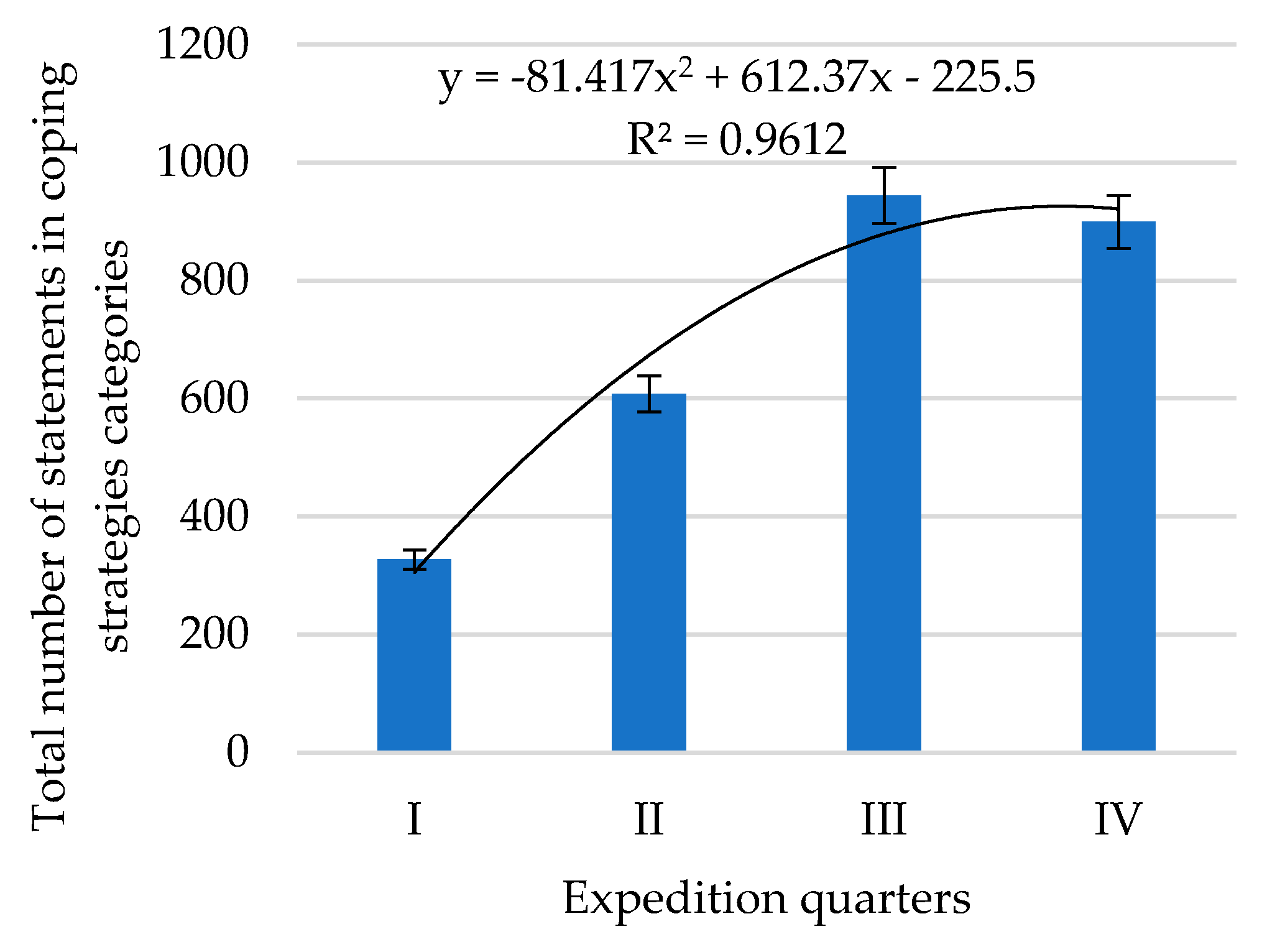

3.2. Influence of flight periods on the crew-MCC communication structure

| Content analysis categories | Before appointment as a Russian segment’s commander (average period weeks 1–9) | Russian segment’s commander (average period weeks 10–21) | After passing the responsibilities of the segment’s commander (week 22–26) | H | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support | 1,22 | 4,54 | 1,86 | 1,595 | 0,450 |

| Initiative | 1,6 | 4,95 | 2,4 | 7,455 | 0,024* |

| Humor | 0,92 | 2,82 | 2,45 | 2,289 | 0,318 |

| Responsibility acceptance | 2,25 | 8,16 | 2,5 | 11,914 | 0,003* |

| Note. Here and in the Table 4: * – statistically significant differences p < 0.05. | |||||

| Content analysis categories | Before appointment as a Russian segment’s commander (average period weeks 1–4) | Russian segment’s commander (average period weeks 5–12) | After receiving a negative message from Earth | H | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support | 0,37 | 9,21 | 2,0 | 10,460 | 0,005* |

| Initiative | 1,87 | 12,16 | 9,0 | 8,457 | 0,015* |

| Humor | 0,13 | 8,48 | 2,83 | 10,99 | 0,004* |

| Responsibility acceptance | 0,25 | 5,22 | 3,08 | 11,652 | 0,003* |

3.3. Study of astronauts’ communicative styles

3.4. Emotional transfer phenomenon

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gushin V.I., Yusupova A.K., Shved D.M. et al. The evolution of methodological approaches to the psychological analysis of the crew communications with Mission Control Center. REACH – Reviews in Human Space Exploration. 2016. № 1. P. 74–83.

- Krippendorf, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1980.

- Neuendorf K.A. The content analysis guidebook; Sage Publications; 2002.

- Simonov P.V., Myasnikov V.I., eds. Remote Observation and Expert Assessment: Role of Communication in Medical Control; Moscow, Nauka, 1982 (in Russian).

- Lazarus R., Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping; Springer Publishing Company, 1984.

- Suedfeld P., Brcic J., Johnson P.J., Gushin V. Coping strategies during and after spaceflight: Data from retired cosmonauts. Acta Astronaut, 2015, 110, 43-49.

- Suedfeld P., Legkaia K., Brcic J. Coping with the problems of space flight: Reports from astronauts and cosmonauts. Acta Astronaut, 2009, 65, 312-324.

- Lomov B.F. Problem of communication in psychology; Moscow, Nauka, 1981 (in Russian).

- Brcic J., Suedfeld P., Johnson Ph., Huynh T., Gushin V. Humor as a coping strategy in spaceflight. Acta Astronaut, 2018, 152(1), 175-178.

- Yusupova A, Shved D, Gushin V, Chekalina A and Supolkina N. Style Features in Communication of the Crews With Mission Control. Front. Neuroergon, 2021, 2:768386. [CrossRef]

- Yusupova A.K., Shved D.M., Gushchin V.I., Supolkina N.S., Chekalina A.I. Preliminary results of “Content” space experiment. Hum. Physiol, 2019, 45(7), 710–717. [CrossRef]

- Bales, R.F., Cohen, S.P., Williamson, S.A. Symlog: A system for the multiple level observation of groups; New York: The Free Press, 1979.

- Shved DM, Gushin VI, Ehman B, Balazs L. Peculiarities of the communication delay impact on the crew communication with Mission Control in the experiment with 520-days isolation. Aviakosmicheskaja i ekologicheskaya medicina 2013; 47 (3), 19–23 (in Russian).

- Yusupova A.K., Gushin V.I., Popova I.I. Communication between MCC and space crews: socio-psychological aspects. Aviakosmicheskaja i ekologicheskaya medicina, 2006, 40 (3), 16-20 (in Russian).

- Kanas, N., Gushin, V., Yusupova, A. Problems and possibilities of astronauts – Ground communication content analysis validity check. Acta Astronaut 2008, 63, 822-827.

- Kanas, N., Gushin, V., Yusupova, A. Problems and possibilities of astronauts – Ground communication content analysis validity check. Acta Astronaut 2008, 63, 822-827.

- Satir V., Gomori M., Banmen J., Gerber J.S. The Satir Model: Family Therapy and Beyond; Science and Behavior Books, Palo Alto, 1991.

- Stuster J. Behavioral Issues Associated with Long Duration Space Expeditions: Review and Analysis of Astronaut Journals Experiment 01-E104 (Journals) Phase 2 Final Report. NASA/TM-2016-218603; National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX, 2016.

- Stuster, J., Bachelard, C., Suedfeld, P. The relative importance of behavioral issues during long-duration ICE missions. Aviat. Space Environ. Med, 2000, 71, 17-25.

- Supolkina N., Yusupova A., Shved D., Gushin V., Savinkina A., Lebedeva S., Chekalina A., Kuznetsova P. External communication of autonomous crews under simulation of interplanetary missions. Front. Physiol., 2021, 12:751170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.751170. [CrossRef]

- Yusupova A., Supolkina N., Shved D., Gushin V., Nosovsky A., Savinkina A. Subjective perception of time in space flights and analogs // Acta Astronaut, 2022. V. 196. P. 238-243. [CrossRef]

- Gushin, V., Shved, D., Vinokhodova, A., Vasylieva, G., Nitchiporuk, I., Ehmann, B., & Balázs, L. Some psychophysiological and behavioral aspects of adaptation to simulated autonomous Mission to Mars. Acta Astronaut, 2012, 70, 52-57.

- Plutchik, R., Emotions and Life: Perspectives from Psychology, Biology, and Evolution; Worcester, MA: Am. Psychol. Assoc., 2003.

- Kanas, N. Humans in Space: The Psychological Hurdles; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Kanas, N.; Manzey, D. Space Psychology and Psychiatry, 2nd ed.; Microcosm Press: El Segundo, CA, USA; Springer: Dor-drecht, Netherlands, 2008.

- Yusupova A., Shved D., Gushin V., Chekalina A., Supolkina N., Savinkina A. Crew communication styles under regular and excessive workload. Acta Astronaut, 2022, Volume 199, 464-470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2022.05.053. [CrossRef]

- R.B. Bechtel, A. Berning, The third-quarter phenomenon: do people experience discomfort after stress has passed? in: A.A. Harrison, Y.A. Clearwater, C.P. McKay (Eds.), From Antarctica to Outer Space; Springer-Verlag, New York, 1991, pp. 261–265.

- Van Wijk, H. Charles, Coping during conventional submarine missions: evidence of a third quarter phenomenon? J. Hum. Perform. Extreme Environ., 2018, 14 (1), 12.

- N. Kanas, V. Gushin, A. Yusupova, Whither the third quarter phenomenon? Aero. Med. Hum. Perform. 2021, 92 (8) 689–691.

- Battler, M. M., Bishop, S. L., Kobrick, R. L., Binsted, K., & Harris, J. The "Us versus Them" phenomenon: Lessons from a long duration human Mars mission simulation. In: 62nd IAC, 2011, pp. 32-37.

- Nasr, M. Evolution of the Flight Crew and Mission Control Relationship. In: AIAA Scitech 2020 Forum, 2020, p. 1361.

- Gromaere S., Beyers W., Vansteenkiste M., Binsted K. Life on Mars from a Self-Determination Theory perspective: how astronauts’ needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness go hand in hand with crew health and mission success - results from HI-SEAS IV, Acta Astronaut. 2019, 159, 273–285.

- Supolkina, N., Shved, D., Yusupova, A., & Gushin, V. The main phenomena of space crews’ communication as a rationale for the modification of mission control communicative style. Frontiers in Psychology, 2023, 14, 1169606.

| Communication functions | |||

| Communication effectiveness | “Informing” | “Social regulation” | “Affective” |

| Effective / Adaptive | Initiative Planful problem-solving |

Accepting responsibility Trust Support |

Humor (positive) Self-control Positive reappraisal Positive emotions |

| Neutral | Informing Problem Effort Requests/ demands Time Cognitive load Searching items Equipment failure / breakdown |

Seeking for social support Endurance/Obedience |

|

| Ineffective / Maladaptive | Escape / avoidance Claim/ Complaint |

Confrontation Mistrust Responsibility avoidance Self-justification |

Distancing Negative emotions Sarcastic humor |

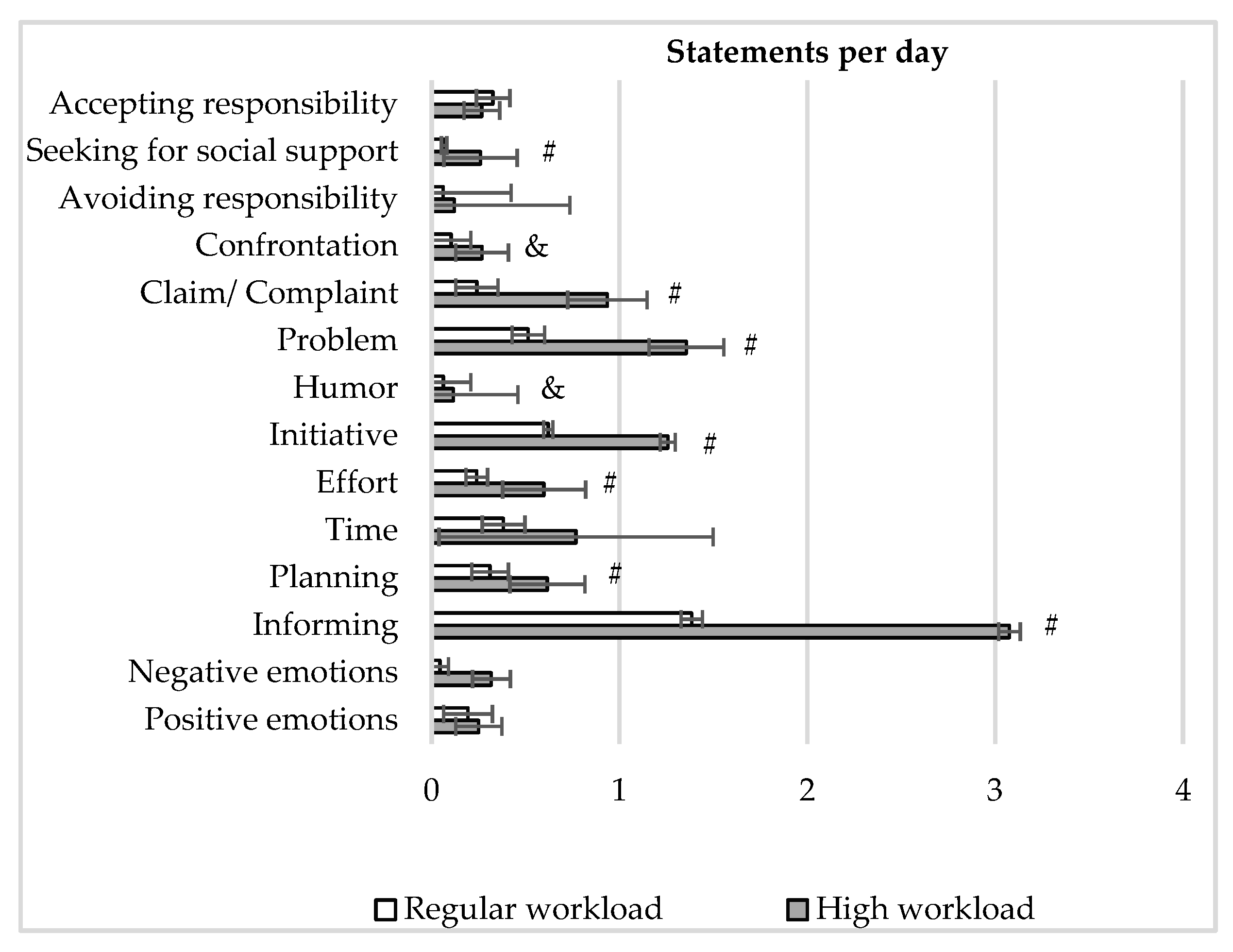

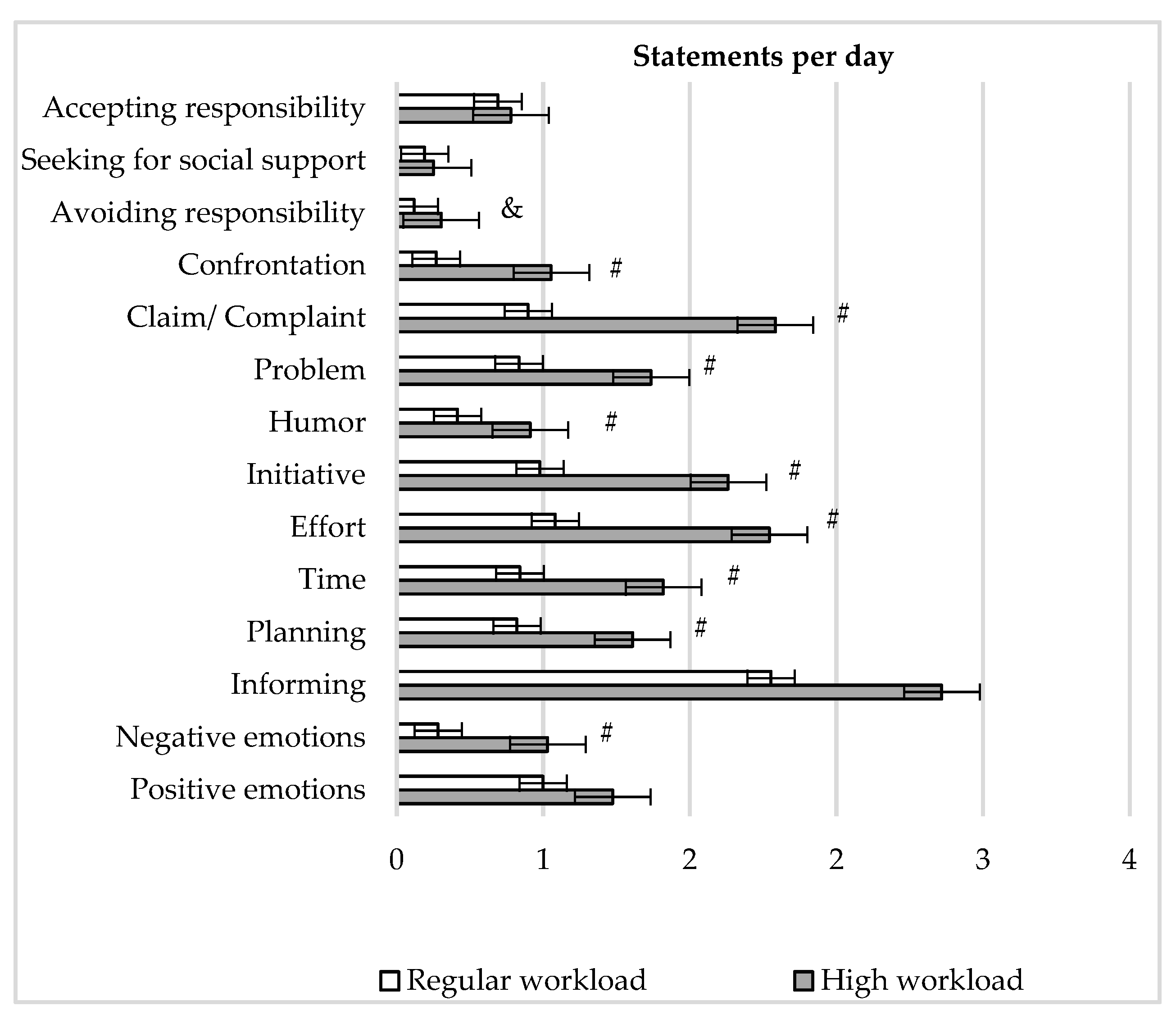

| Categories group | Categories | Days with standard workload | Days with high workload | Significance of differences according to the Mann-Whitney test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Average | |||

| Maladaptive strategies | Negative emotions | 0,12 | 0,60 | <0,001* |

| Claim/Complaint | 0,35 | 1,24 | <0,001* | |

| Confrontation | 0,13 | 0,59 | <0,001* | |

| Responsibility avoidance | 0,15 | 0,35 | <0,001* | |

| Self-justifications | 0,05 | 0,11 | 0,013* | |

| Adaptive strategies | Initiative | 0,80 | 1,91 | <0,001* |

| Positive emotions | 0,57 | 0,94 | <0,001* | |

| Planful problem-solving (Planning) | 0,55 | 1,20 | <0,001* | |

| Trust | 0,04 | 0,11 | 0,001* | |

| Humor | 0,17 | 0,44 | <0,001* | |

| Informing | 1,95 | 3,94 | <0,001* | |

| Positive reappraisal | 0,01 | 0,03 | 0,008* | |

| Self-control | 0,08 | 0,17 | 0,001* | |

| Neutral categories | Effort | 0,44 | 1,29 | <0,001* |

| Requests/ demands | 1,01 | 1,89 | <0,001* | |

| Time | 0,62 | 1,42 | <0,001* | |

| Cognitive load | 0,55 | 1,29 | <0,001* | |

| Problem | 0,62 | 1,37 | <0,001* | |

| Breakdown | 0,15 | 0,29 | <0,001* | |

| Searching items | 0,31 | 0,68 | <0,001* | |

| Seeking social support | 0,15 | 0,38 | <0,001* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).