Submitted:

09 January 2024

Posted:

11 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Data Analysis

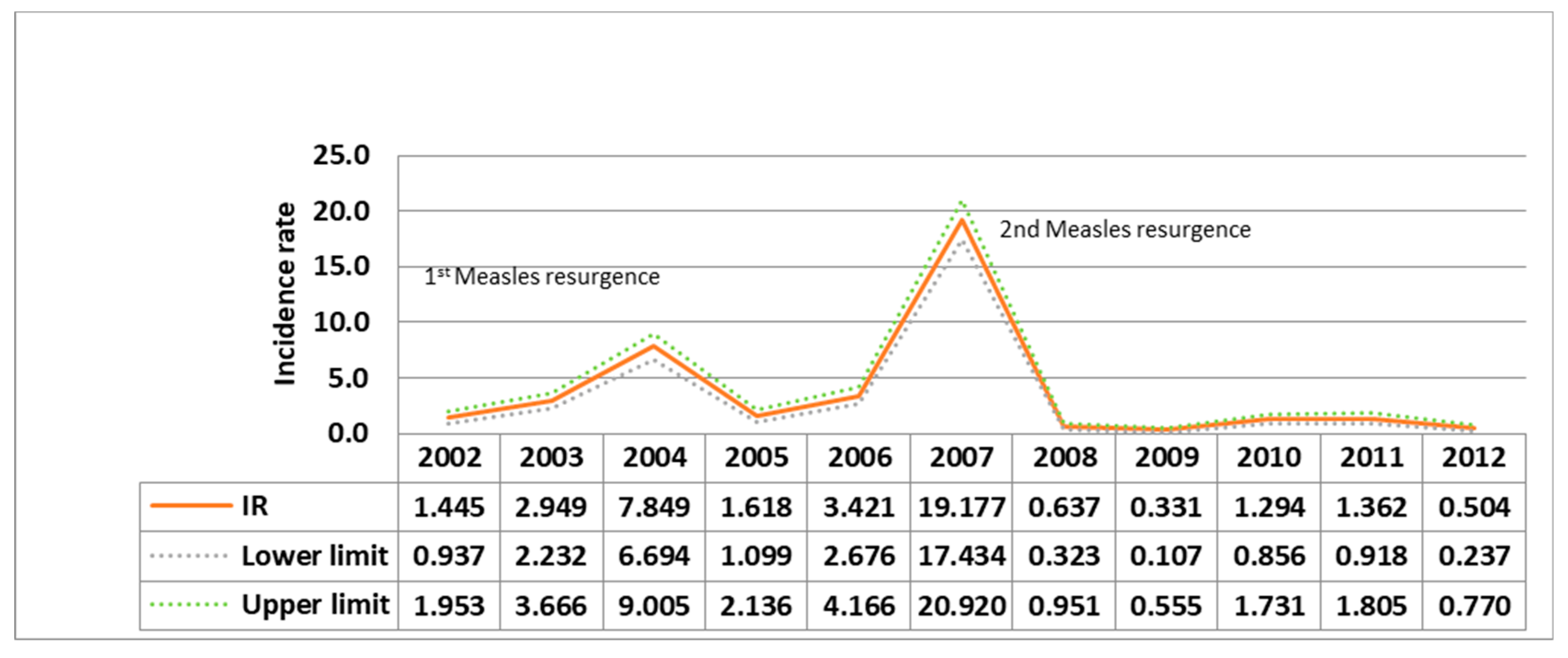

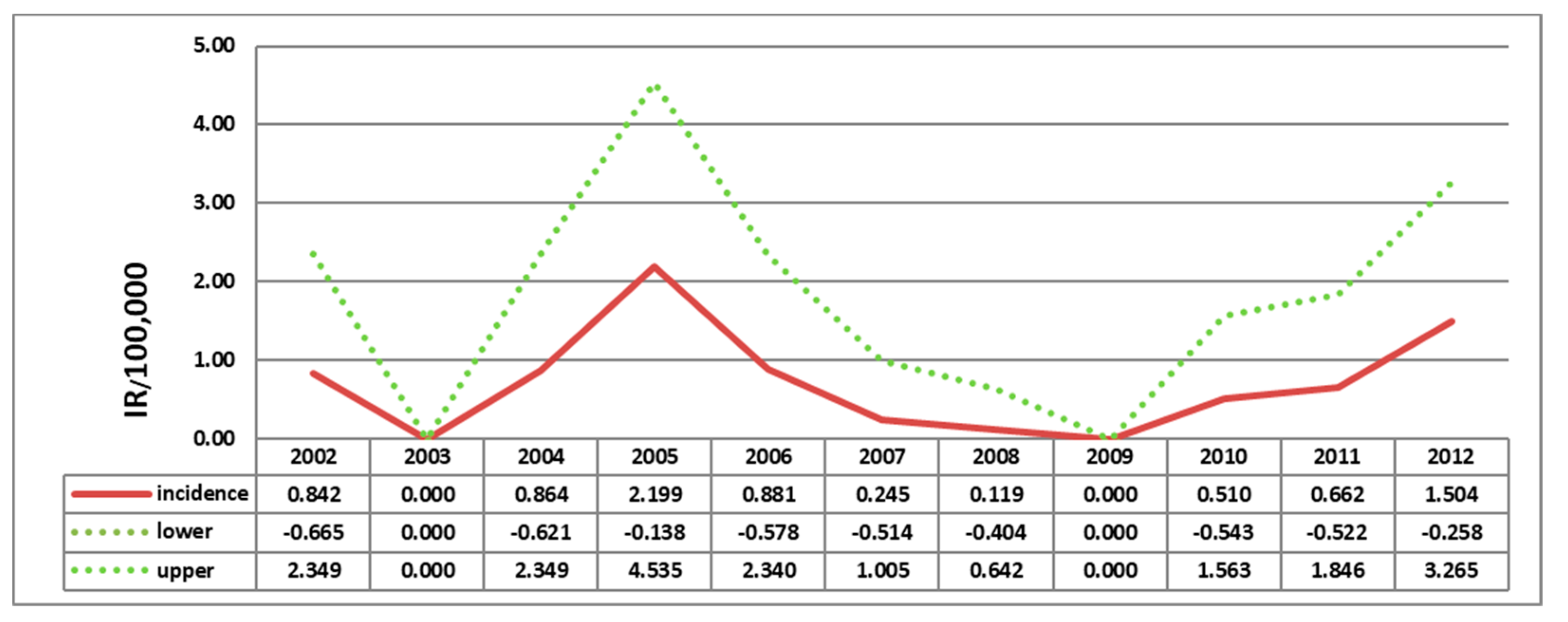

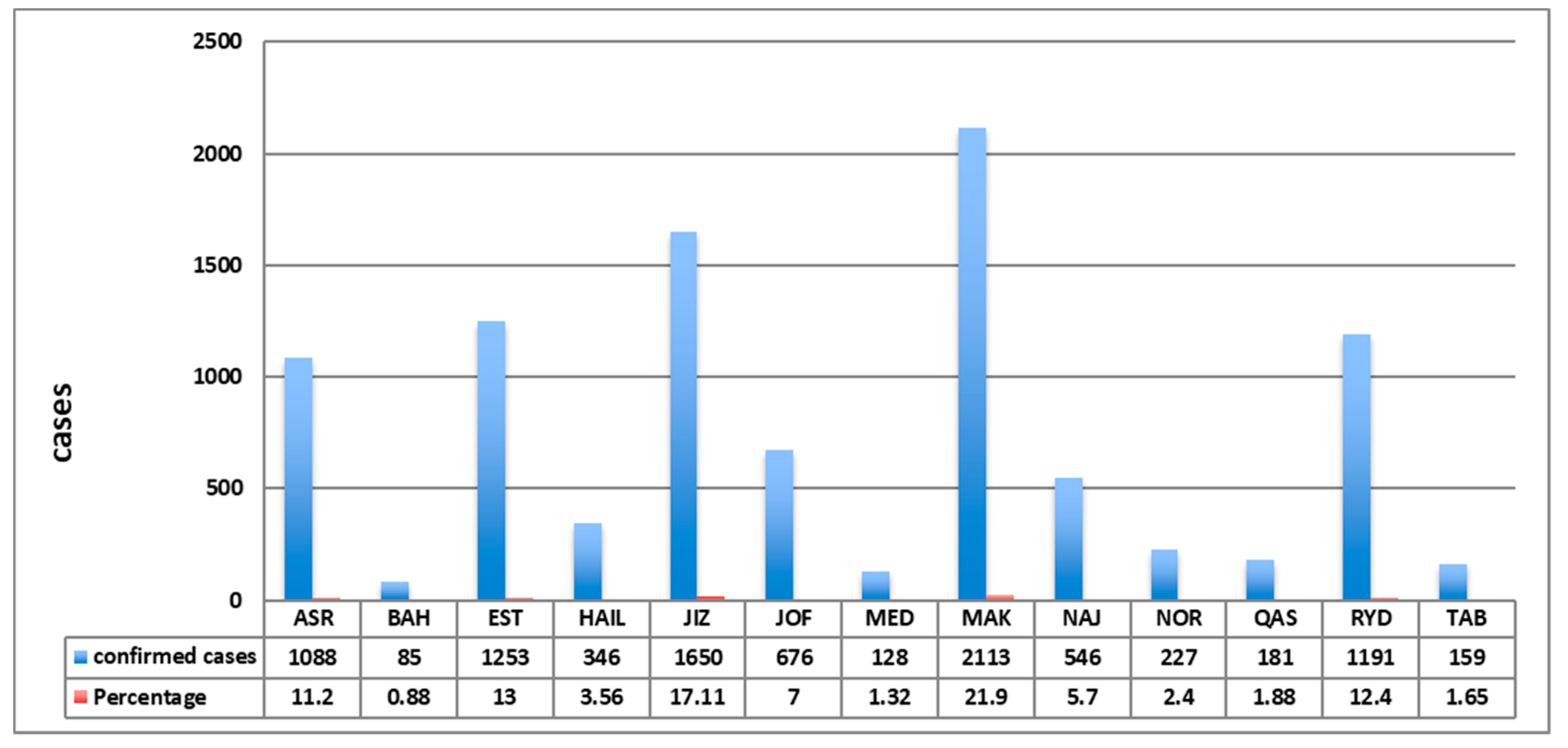

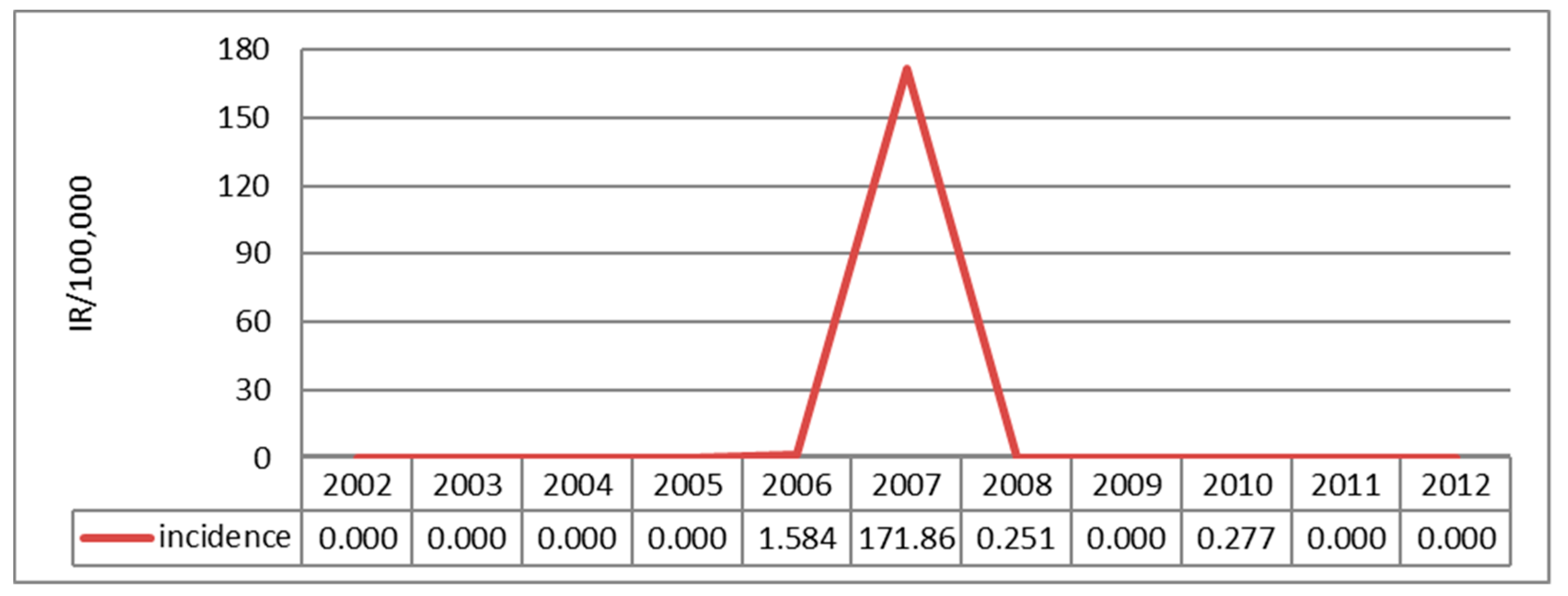

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Recommendations

References

- PLAN, S. Global Measles and Rubella 2012.

- Factsheet: measles. N S W Public Health Bull 2012, 23, 209. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluster, W.H.O.C.D., W.H.O.H. Technology, and Pharmaceuticals, WHO Guidelines for Epidemic Preparedness and Response of Measles Outbreaks. 1999: World Health Organization, Expanded Programme on Immunization, Vaccines and other Biologicals [and] Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Response.

- World Health Organization. Measles. 2013 [cited 2013; Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs286/en/.

- Perry, R.T. and N.A. Halsey, The clinical significance of measles: a review. J Infect Dis 2004. 189 (Suppl 1), S4-16. (Suppl 1).

- Preeta Kutty MD; Jennifer Rota MPH, W.B.P., Susan B. Redd, Measles. 2012, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Moss, W.J. and D.E. Griffin, Measles. Lancet 2012, 379, 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Ent, M.M., et al., Measles mortality reduction contributes substantially to reduction of all cause mortality among children less than five years of age, 1990–2008. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2011, 204 (suppl 1), S18-S23. (suppl 1).

- Global control and regional elimination of measles, 2000-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013, 62, 27–31.

- The World Factbook, C.I.A. 2013; Available online: https://http://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sa.html.

- Khalil, M.K. , et al. Measles in Saudi Arabia: from control to elimination. Ann Saudi Med 2005, 25, 324–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, S. , et al. Measles outbreak in Qassim, Saudi Arabia 2007: epidemiology and evaluation of outbreak response. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008, 30, 384–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, M.K. , et al. Measles immunization in Saudi Arabia: the need for change. East Mediterr Health J, 2001; 7, 829–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, S.A. Health Statistical Year Book. 2011. p. 44.

- Memish, Z.A. Infection control in Saudi Arabia: meeting the challenge. Am J Infect Control 2002, 30, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Saudi | Non-Saudi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | 95% CI | IR | 95% CI | |

| 2002 | 1.97 | (1.27, 2.66) | 0.05 | (-0.13, 0.23) |

| 2003 | 3.73 | (2.79, 4.68) | 0.85 | (0.11, 1.59) |

| 2004 | 9.87 | (8.35, 11.39) | 2.43 | (1.2, 3.67) |

| 2005 | 1.57 | (0.97, 2.17) | 1.74 | (0.71, 2.77) |

| 2006 | 4.23 | (3.26, 5.20) | 1.23 | (0.37, 2.09) |

| 2007 | 25.03 | (22.7, 27.36) | 3.37 | (1.97, 4.78) |

| 2008 | 0.83 | (0.41, 1.25) | 0.11 | (-0.14, 0.35) |

| 2009 | 0.39 | (0.11, 0.68) | 0.16 | (-0.14, 0.46) |

| 2010 | 1.42 | (0.89, 1.96) | 0.95 | (0.22, 1.67) |

| 2011 | 0.53 | (1.16, 2.33) | 0.32 | (-0.09, 0.74) |

| 2012 | 0.53 | (0.21, 0.85) | 0.44 | (-0.04, 0.92) |

| Age groups in Years | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 - 14 |

231 2.40 3.28 74.28 |

529 5.49 7.52 81.51 |

1404 14.58 19.95 79.23 |

303 3.15 4.31 81.02 |

616 6.40 8.75 76.05 |

3251 33.75 46.21 69.93 |

89 0.92 1.26 56.33 |

48 0.50 0.68 57.14 |

228 2.37 3.24 67.86 |

262 2.72 3.72 72.38 |

75 0.78 1.07 59.06 |

7036 73.05 |

| 15 - 24 |

47 0.49 3.63 15.11 |

58 0.60 4.48 8.94 |

189 1.96 14.61 10.67 |

33 0.34 2.55 8.82 |

79 0.82 6.11 9.75 |

749 7.78 57.88 16.11 |

34 0.35 2.63 21.52 |

14 0.15 1.08 16.67 |

41 0.43 3.17 12.20 |

41 0.43 3.17 11.33 |

9 0.09 0.70 7.09 |

1294 13.43 |

| 25 - 34 |

27 0.28 2.89 8.68 |

47 0.49 5.03 7.24 |

134 1.39 14.33 7.56 |

23 0.24 2.46 6.15 |

87 0.90 9.30 10.74 |

467 4.85 49.95 10.05 |

24 0.25 2.57 15.19 |

20 0.21 2.14 23.81 |

40 0.42 4.28 11.90 |

35 0.36 3.74 9.67 |

31 0.32 3.32 24.41 |

935 9.71 |

| 35 - 44 |

6 0.06 1.96 1.93 |

14 0.15 4.58 2.16 |

38 0.39 12.42 2.14 |

13 0.13 4.25 3.48 |

25 0.26 8.17 3.09 |

150 1.56 49.02 3.23 |

8 0.08 2.61 5.06 |

2 0.02 0.65 2.38 |

19 0.20 6.21 5.65 |

20 0.21 6.54 5.52 |

11 0.11 3.59 8.66 |

306 3.18 |

| 45 - 54 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

1 0.01 2.44 0.15 |

6 0.06 14.63 0.34 |

1 0.01 2.44 0.27 |

2 0.02 4.88 0.25 |

20 0.21 48.78 0.43 |

2 0.02 4.88 1.27 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

5 0.05 12.20 1.49 |

4 0.04 9.76 1.10 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

41 0.43 |

| 55 - 64 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

7 0.07 63.64 0.15 |

1 0.01 9.09 0.63 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

3 0.03 27.27 0.89 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

11 0.11 |

| ≥ 65 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

1 0.01 11.11 0.06 |

1 0.01 11.11 0.27 |

1 0.01 11.11 0.12 |

5 0.05 55.56 0.11 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

1 0.01 11.11 0.79 |

9 0.09 |

| Total |

311 3.23 |

649 6.74 |

1772 18.40 |

374 3.88 |

810 8.41 |

4649 48.27 |

158 1.64 |

84 0.87 |

336 3.49 |

362 3.76 |

127 1.32 |

9632 100.00 |

|

Frequency Missing = 11 Numbers are arranged longitudinally as below: Frequency Percent Row percent Column percent | ||||||||||||

| Controlling for Nationality = Saudi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Immunization Status | Province | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASR | BAH | EST | HAIL | JIZ | JOF | MED | MAK | NAJ | NOR | QAS | RYD | TAB | Total | |||||||||||||||

| Not Vaccinated |

669 7.61 14.11 62.52 |

31 0.35 0.65 36.90 |

854 9.72 18.01 72.25 |

153 1.74 3.23 44.35 |

1018 11.59 21.47 67.82 |

286 3.25 6.03 42.56 |

56 0.64 1.18 70.00 |

851 9.68 17.95 51.51 |

203 2.31 4.28 39.42 |

92 1.05 1.94 41.63 |

41 0.47 0.86 24.40 |

411 4.68 8.67 35.99 |

77 0.88 1.62 49.68 |

4742 53.97 |

||||||||||||||

| Unknown |

90 1.02 7.26 8.41 |

6 0.07 0.48 7.14 |

119 1.35 9.60 10.07 |

45 0.51 3.63 13.04 |

231 2.63 18.64 15.39 |

214 2.44 17.27 31.85 |

7 0.08 0.56 8.75 |

202 2.30 16.30 12.23 |

117 1.33 9.44 22.72 |

15 0.17 1.21 6.79 |

45 0.51 3.63 26.79 |

131 1.49 10.57 11.47 |

17 0.19 1.37 10.97 |

1239 14.10 |

||||||||||||||

| Vaccinated |

311 3.54 11.08 29.07 |

47 0.53 1.67 55.95 |

209 2.38 7.45 17.68 |

147 1.67 5.24 42.61 |

252 2.87 8.98 16.79 |

172 1.96 6.13 25.60 |

17 0.19 0.61 21.25 |

599 6.82 21.35 36.26 |

195 2.22 6.95 37.86 |

114 1.30 4.06 51.58 |

82 0.93 2.92 48.81 |

600 6.83 21.38 52.54 |

61 0.69 2.17 39.35 |

2806 31.93 |

||||||||||||||

| Total |

1070 12.18 |

84 0.96 |

1182 13.45 |

345 3.93 |

1501 17.08 |

672 7.65 |

80 0.91 |

1652 18.80 |

515 5.86 |

221 2.52 |

168 1.91 |

1142 13.00 |

155 1.76 |

8787 100.00 |

||||||||||||||

|

Frequency Missing = 105 Percent Row percent Column percent | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Controlling for Nationality = Non-Saudi | |||||||||||||

| Immunization Status | Province | ||||||||||||

| ASR | BAH | EST | HAIL | JIZ | JOF | MED | MAK | NAJ | QAS | RYD | TAB | Total | |

| Not Vaccinated |

2 0.28 0.46 50.00 |

1 0.14 0.23 100.00 |

40 5.56 9.26 60.61 |

1 0.14 0.23 100.00 |

93 12.93 21.53 65.96 |

1 0.14 0.23 25.00 |

11 1.53 2.55 55.00 |

241 33.52 55.79 61.79 |

17 2.36 3.94 54.84 |

7 0.97 1.62 53.85 |

15 2.09 3.47 38.46 |

2 0.28 0.46 66.67 |

432 60.08 |

| Unknown |

1 0.14 0.99 25.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

13 1.81 12.87 19.70 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

28 3.89 27.72 19.86 |

3 0.42 2.97 75.00 |

6 0.83 5.94 30.00 |

41 5.70 40.59 10.51 |

4 0.56 3.96 12.90 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

2 0.28 1.98 5.13 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

101 14.05 |

| Vaccinated |

1 0.14 0.54 25.00 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

13 1.81 6.99 19.70 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

20 2.78 10.75 14.18 |

0 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

3 0.42 1.61 15.00 |

108 15.02 58.06 27.69 |

10 1.39 5.38 32.26 |

6 0.83 3.23 46.15 |

22 3.06 11.83 56.41 |

1 0.14 0.54 33.33 |

186 25.87 |

| Total |

4 0.56 |

1 0.14 |

66 9.18 |

1 0.14 |

141 19.61 |

4 0.56 |

20 2.78 |

390 54.24 |

31 4.31 |

13 1.81 |

39 5.42 |

3 0.42 |

719 100.00 |

|

Frequency Missing = 32 Percent Row percent Column percent | |||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).