Submitted:

11 January 2024

Posted:

11 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

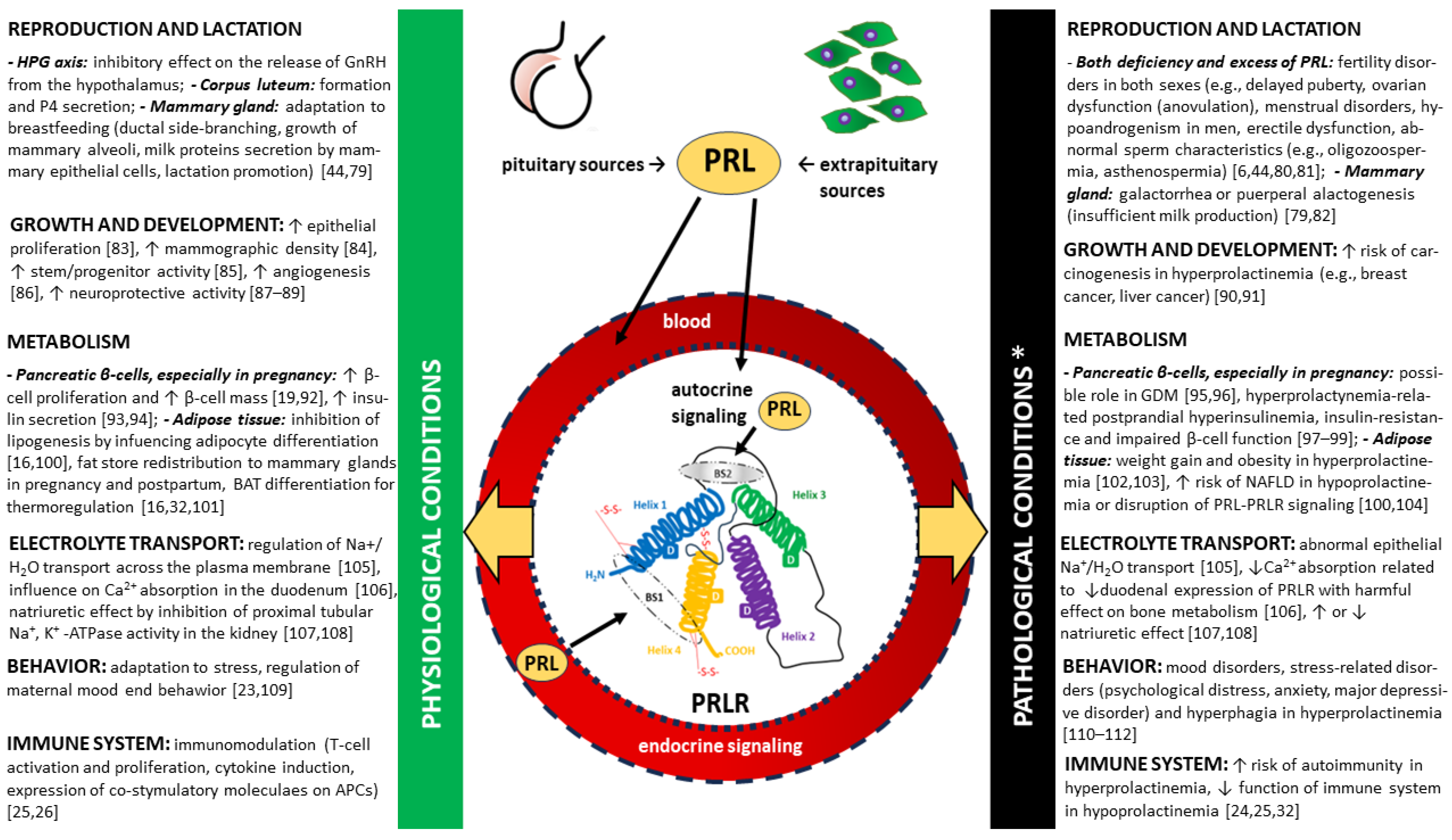

2. Prolactin (PRL)

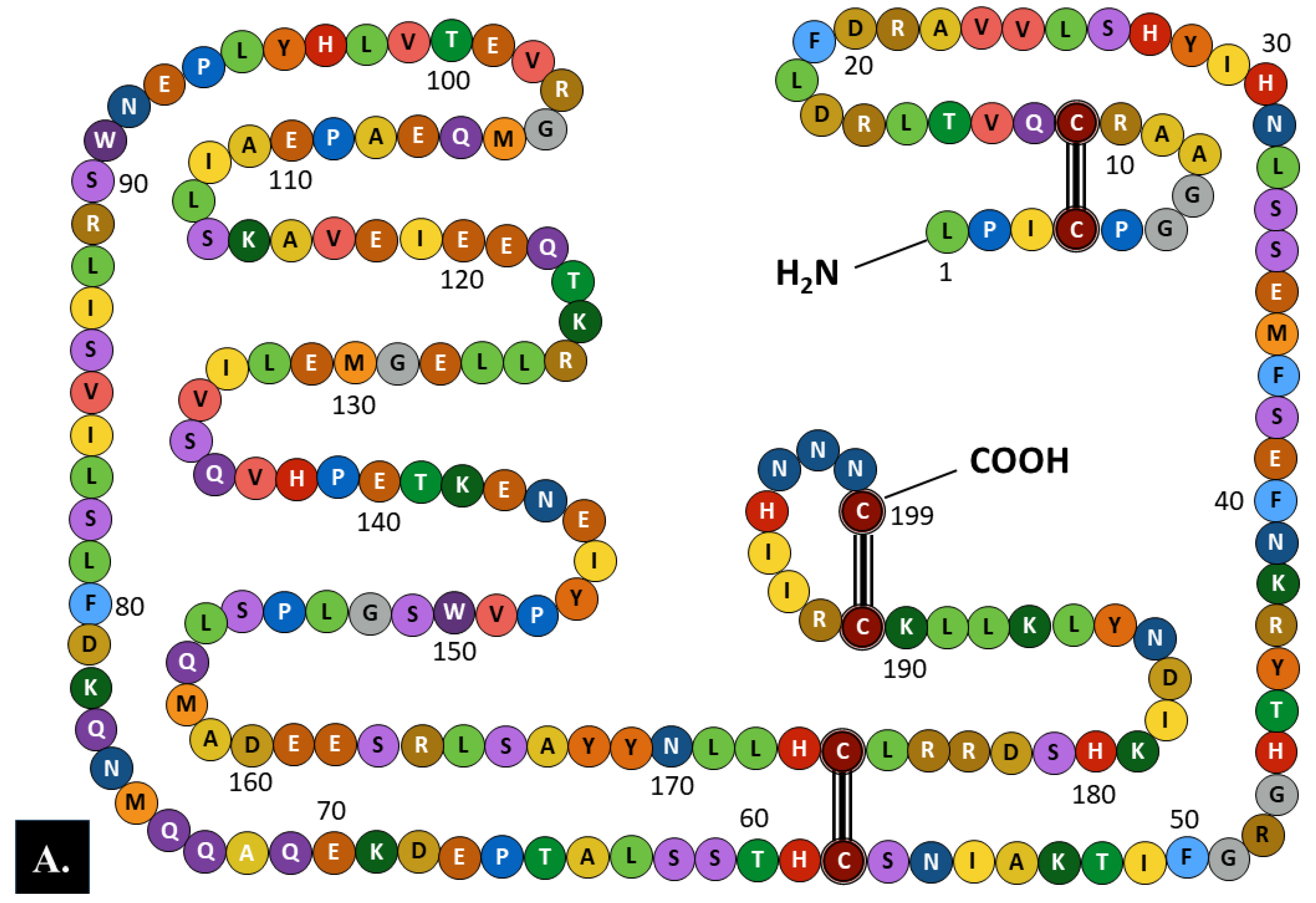

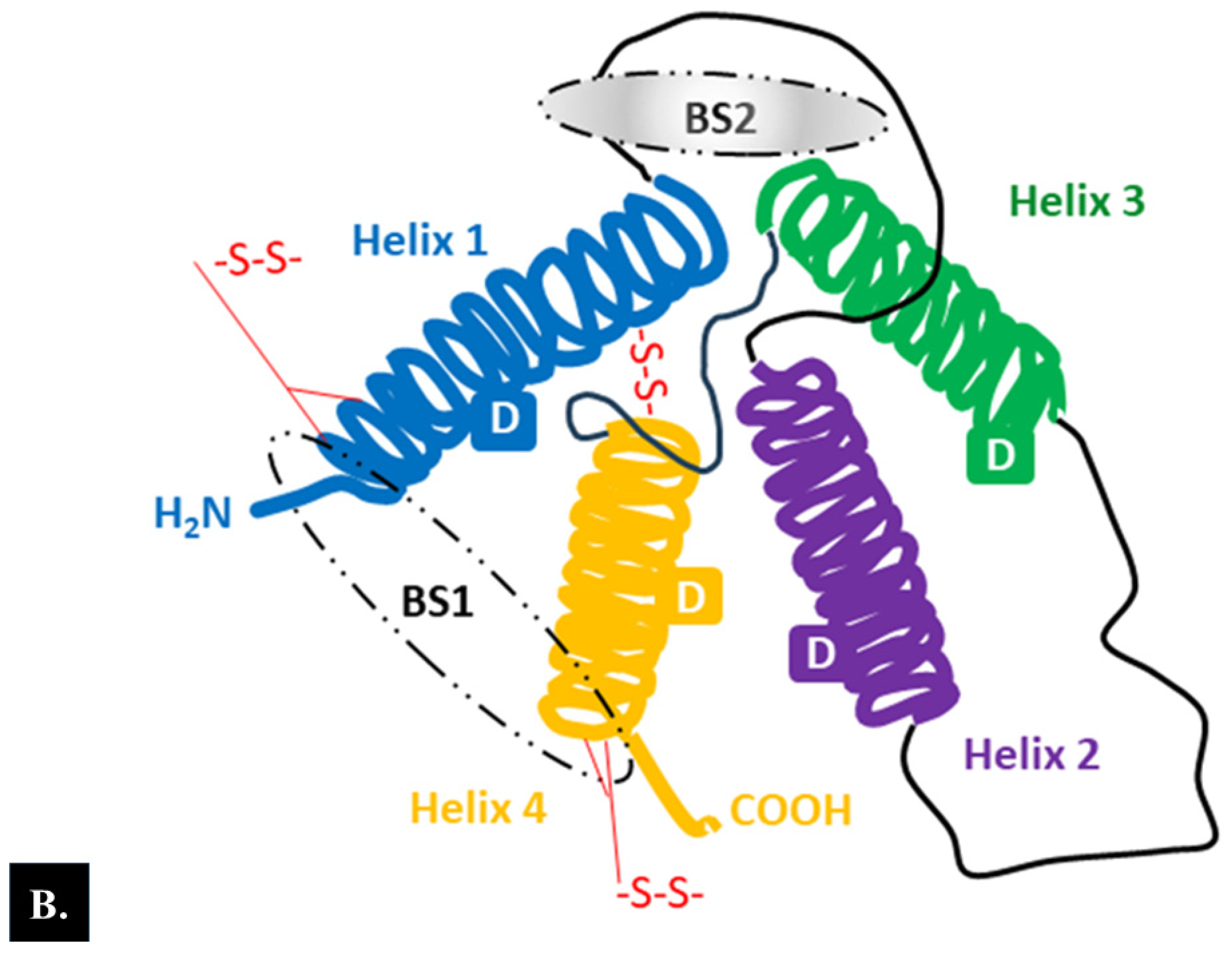

2.1. Structure

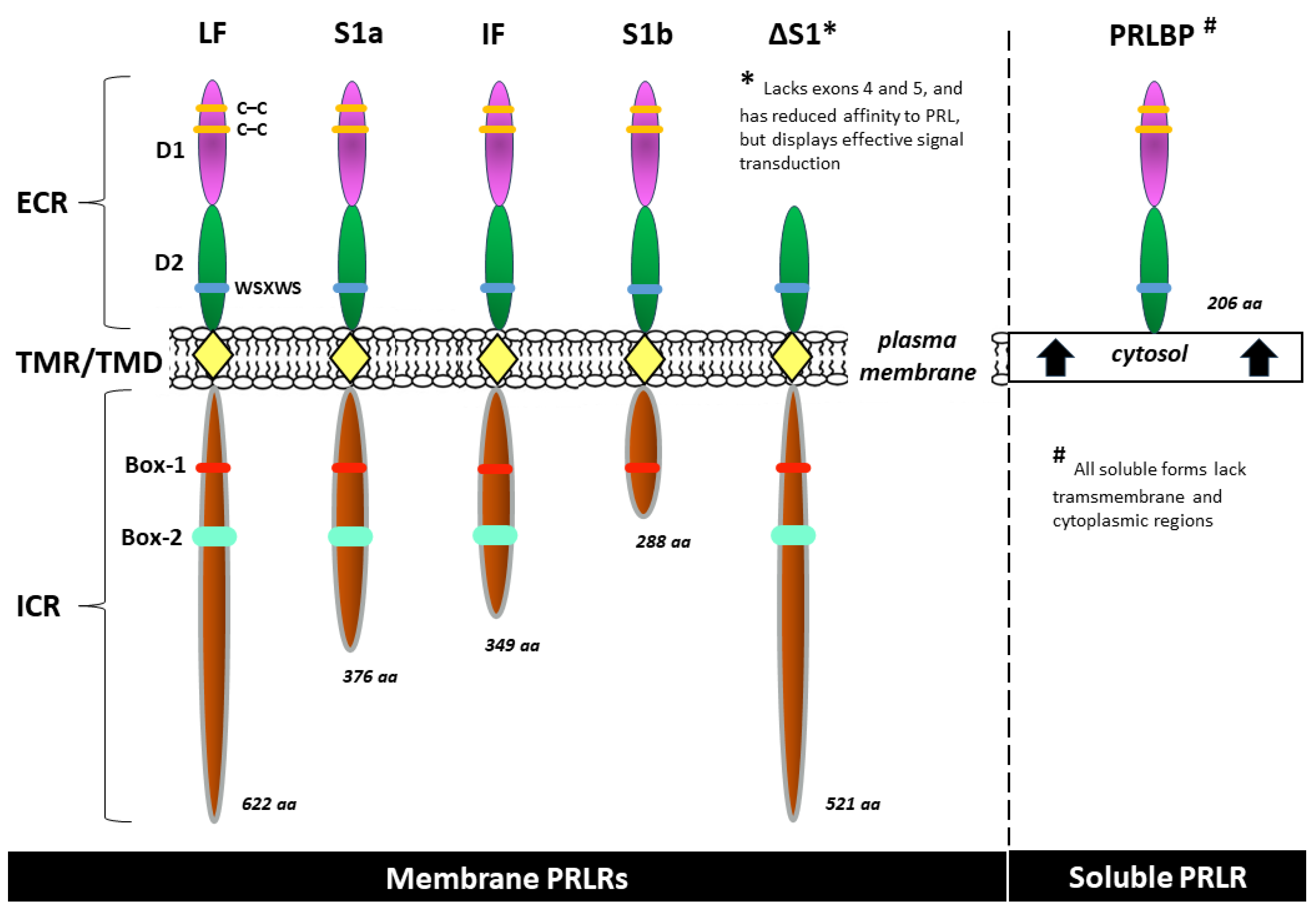

2.2. Prolactin receptor (PRLR)

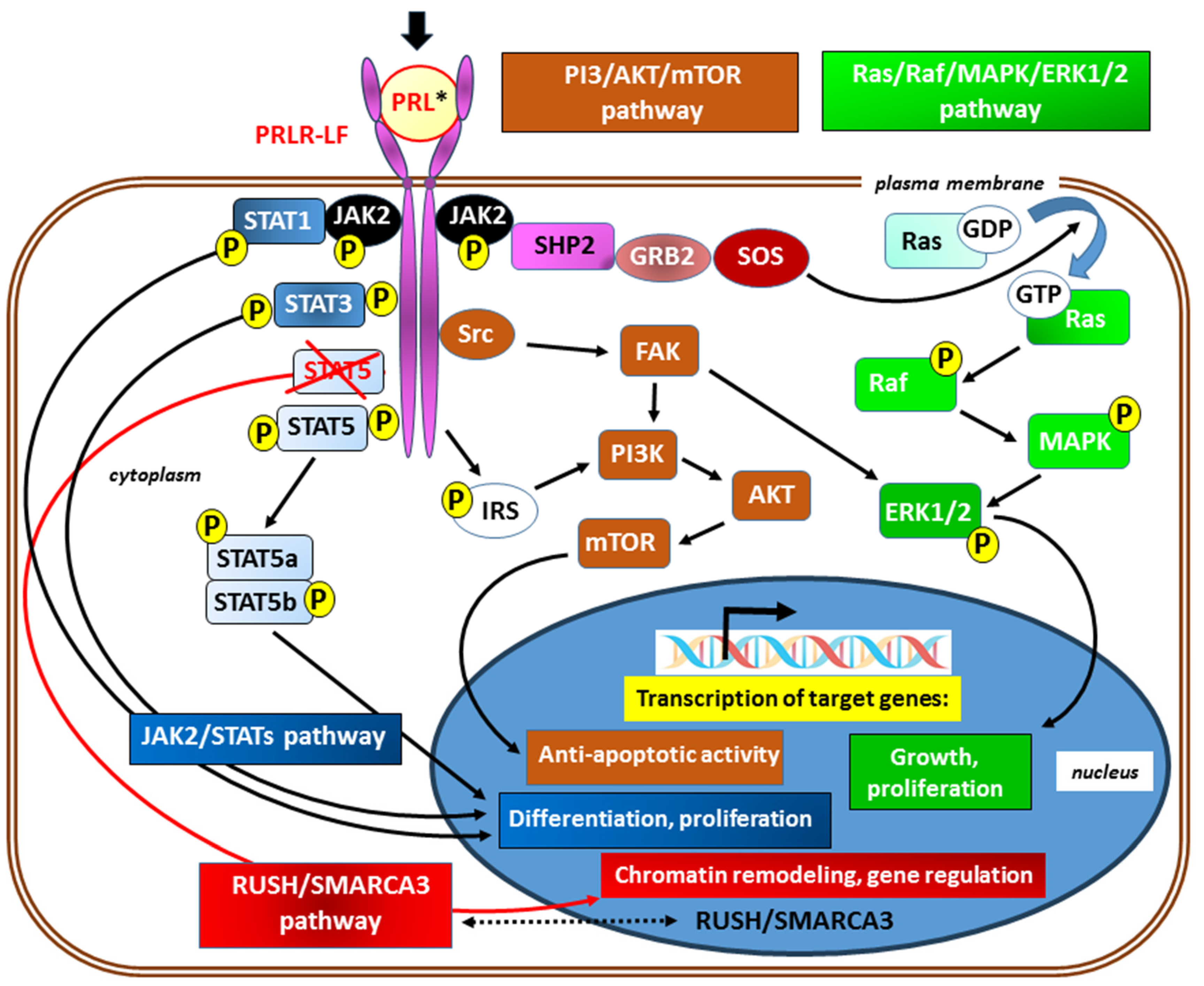

2.2.1. PRLR receptor signaling

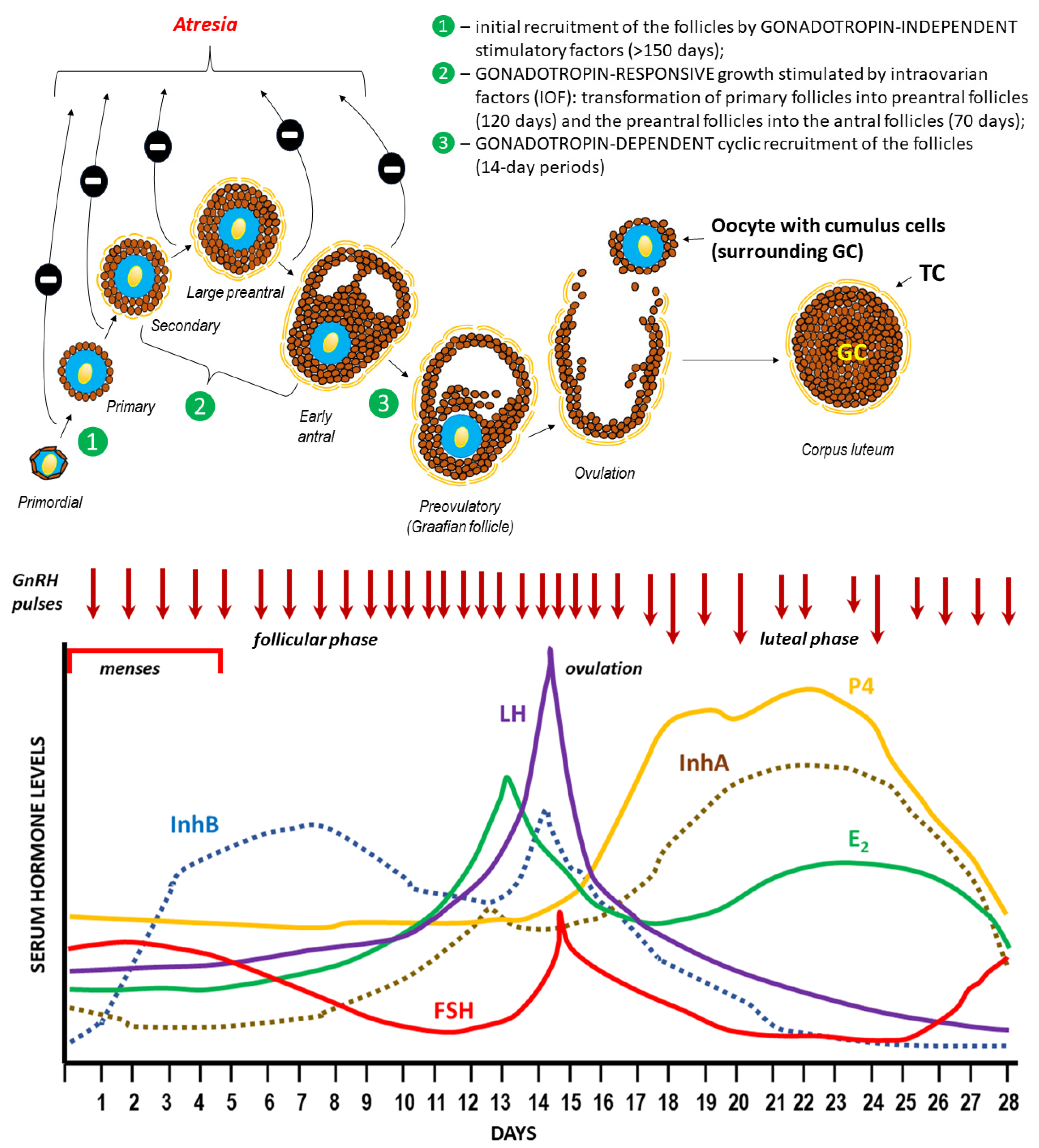

3. Ovulation

3.1. Hormonal regulation of ovulation

3.2. Mechanism of follicle rupture during ovulation

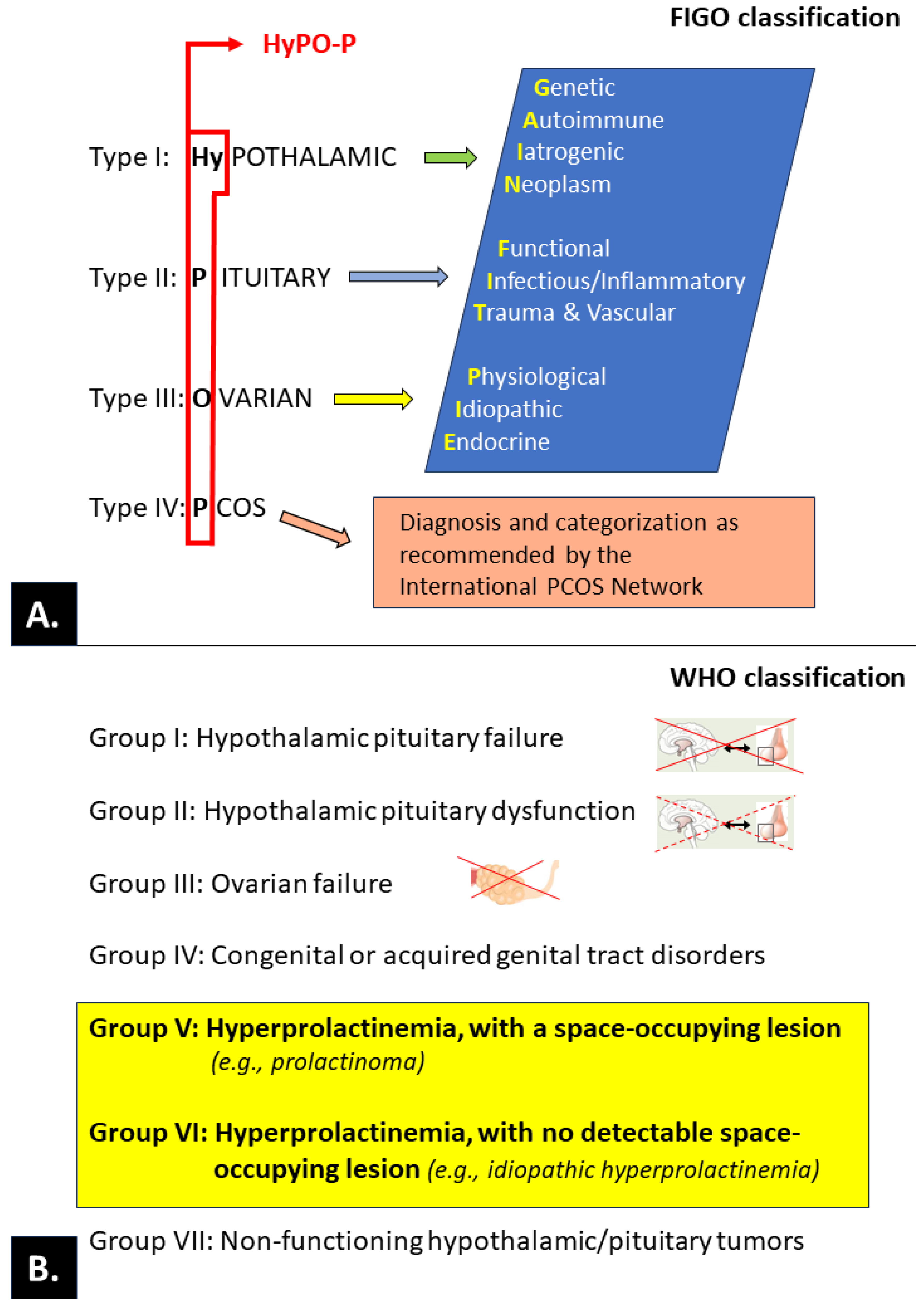

3.3. Ovulatory disorders

3.3.1. PRL and ovulatory disorders

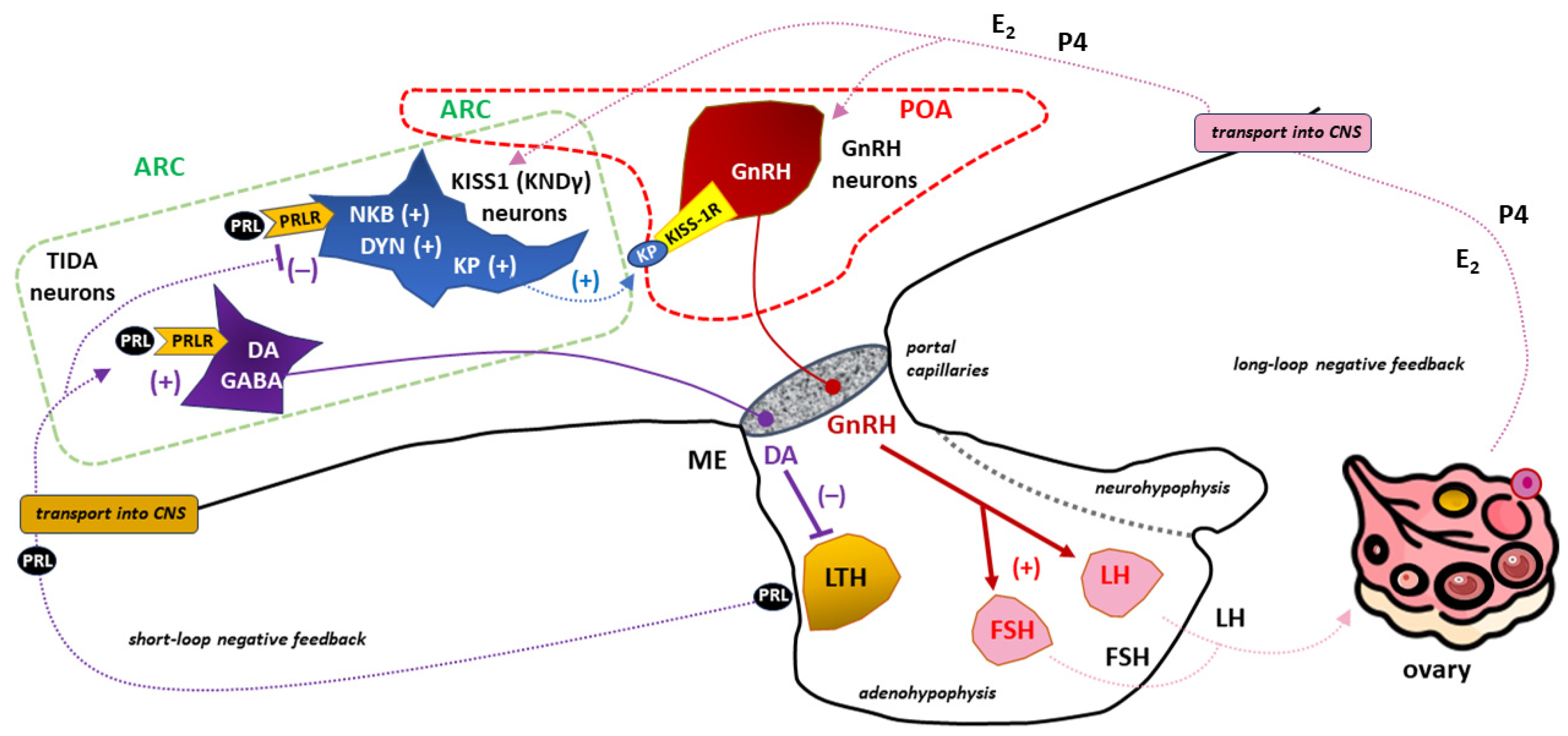

3.3.1.1. PRL and the release of gonadotropins.

3.3.1.2 PRL-kisspeptin interaction

4. Concluding remarks

Abbreviations

| 17-OHP | 17-hydroxyprogesterone |

| 3β-HSD | 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase |

| 5-HT | serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) |

| aa | amino acid count |

| ACTH | adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| AKT | protein kinase B |

| APC | antigen-presenting cells |

| ARC | arcuate nucleus (caudal region of the hypothalamus) |

| BAT | brown adipose tissue |

| BSs, BS1, BS2 | binding sites, binding site 1, binding site 2, respectively |

| Box-1, Box-2 | the proline-rich and hydrophobic regions in the intracellular domain of cytokine receptor 1 and 2, respectively |

| cAMP | cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| C-C | carbon-carbon bond |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| D1, D2 | the two fibronectin type III domains of the prolactin receptor |

| DA | dopamine |

| DYN | dynorphin |

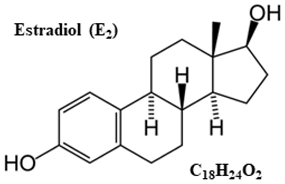

| E1, E2, E3, E4 | estrone, estradiol, estriol and estetrol, respectively |

| ECR | extracellular region of receptor |

| EPOR | erythropoietin receptor |

| ER-α | estrogen receptor-α |

| ERK1/2 | extracellular signal-regulated kinase ½ |

| FAK | focal adhesion kinase |

| FIGO | International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

| FSH | follicle-stimulating hormone |

| FSHR | follicle-stimulating hormone receptor |

| GABA | gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GC | granulosa cells |

| GDM | gestational diabetes mellitus |

| GDP, GTP | guanosine diphosphate and guanosine triphosphate, respectively |

| GH | growth hormone |

| GnRH | gonadotropin-releasing hormone (gonadoliberin) |

| GPER | G protein-coupled estrogen-receptor |

| GRB2 | growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 |

| hCG | human chorionic gonadotropin |

| HETE | hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid |

| hGLC | human granulosa cells |

| HPG axis | hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis |

| hPL | human placental lactogen (also called human chorionic somatotropin - hCS) |

| HPO | hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis |

| HRT | hormonal replacement therapy |

| ICR | intracellular (cytoplasmic) region of receptor |

| icv | intracerebroventricular |

| IL-2R | interleukin-2 receptor |

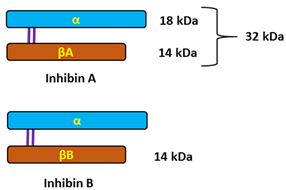

| InhA | inhibin A (also marked as αβA) |

| InhB | inhibin B (also marked as αβB) |

| IRS | insulin receptor substrate |

| JAK2 | Janus kinase 2 |

| KISS-1R | kisspeptin receptor (also known as GPR54) |

| KNDγ neurons | kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin neurons |

| KP | kisspeptin |

| LH | luteinizing hormone |

| LTH | lactotrophs (lactotropic cells) |

| MAOIs | monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MBH | mediobasal region of the hypothalamus |

| ME | median eminence of the hypothalamus |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin (serine-threonine protein kinase) |

| NFPAs | non-functioning pituitary adenomas |

| NKB | neurokinin B |

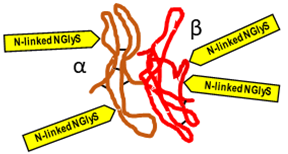

| N-linked NGlyS | N-linked glycosylation sites in human proteins |

| NPFFR1 | neuropeptide FF receptor 1 |

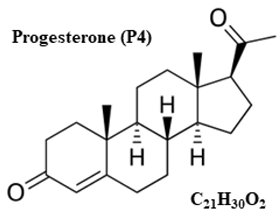

| P4 | progesterone |

| PCOS | polycystic ovary syndrome |

| pE | pyroglutamate (pyroglutamic acid) |

| PI3 | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PIH | pregnancy-induced hypertension |

| Pit-1 | transcription factor, a member of the POU (Pit-Oct-Unc) homeodomain protein family |

| POA | preoptic area (rostral region of the hypothalamus) |

| PRFs | prolactin-releasing factors |

| PRL | prolactin |

| PRLBP | prolactin binding protein |

| PRLR | prolactin receptor (a member of the class I cytokine receptor family) |

| PRLR-LF | long form of prolactin receptor |

| pSTAT5 | phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 |

| Ras/Raf | Ras/Raf kinases |

| SER | smooth endoplasmic reticulum |

| SHP2 | Src homology 2 (SH2) domain |

| SMARCA3 | SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily A, member 3 |

| SOS | son of sevenless, refers to a set of genes encoding guanine nucleotide exchange factors that act on the Ras subfamily of small GTPases |

| SRC | Src family kinases |

| SSRIs | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| STAT5 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 |

| STATs | signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins |

| TCA | tricyclic antidepressants |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-beta |

| TIDA neurons | tuberoinfundibular dopamine neurons |

| TMR/TMD | transmembrane region/transmembrane domain of receptor |

| TpoR | thrombopoietin receptor (also known as MPL) |

| TRH | thyrotropin-releasing hormone |

| TSH | thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| VIP | vasoactive intestinal peptide |

| VMAT2 | vesicular monoamine transporter type-2 |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WSXWS | a conserved amino acid sequence (WS motif) in prolactin receptor |

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stricker P, Grüter F. Action du lobe antérieur de l’hypophyse sur la montée laiteuse. CR Soc Biol. (Paris). 1928, 99, 1978–1980.

- Flückiger E, del Pozo E, von Werder K. Prolactin. Physiology, pharmacology and clinical findings. Monographs on Endocrinology 23. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York 1982. [CrossRef]

- Riddle O, Braucher PF. Control of the special secretion of the crop gland in pigeons by an anterior pituitary hormone. Am J Physiol. 1931, 97, 617–625.

- Riddle O, Bates RW, Dykshorn SW. The preparation, identification and assay of prolactin–a hormone of the anterior pituitary. Am J Physiol. 1933, 105, 191–216 http://ajplegacyphysiologyorg/cgi/reprint/105/1/191).

- Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Nagy G. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000, 80, 1523–631. [CrossRef]

- Bernard V, Young J, Binart N. Prolactin - a pleiotropic factor in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 356–365. [CrossRef]

- Al-Chalabi M, Bass AN, Alsalman I. Physiology, Prolactin. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507829/. 5078.

- Grattan, DR. 60 YEARS OF NEUROENDOCRINOLOGY: The hypothalamo-prolactin axis. J Endocrinol. 2015, 226, T101–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karayazi Atıcı Ö, Govindrajan N, Lopetegui-González I, Shemanko CS. Prolactin: A hormone with diverse functions from mammary gland development to cancer metastasis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 114, 159–170. [CrossRef]

- Bachelot A, Binart N. Reproductive role of prolactin. Reproduction. 2007, 133, 361–369. [CrossRef]

- Bouilly J, Sonigo C, Auffret J, Gibori G, Binart N. Prolactin signaling mechanisms in ovary. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012, 356, 80–7. [CrossRef]

- Donato J Jr, Frazão R. Interactions between prolactin and kisspeptin to control reproduction. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2016, 60, 587–595. [CrossRef]

- Basini G, Baioni L, Bussolati S, Grolli S, Grasselli F. Prolactin is a potential physiological modulator of swine ovarian follicle function. Regul Pept. 2014, 189, 22–30. [CrossRef]

- Holesh JE, Bass AN, Lord M. Physiology, Ovulation. 2023. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–.

- Laron, Z. The growth hormone-prolactin relationship: a neglected issue. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2011, 9, 546–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ben-Jonathan N, Hugo E. Prolactin (PRL) in adipose tissue: regulation and functions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015, 846, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Brandebourg T, Hugo E, Ben-Jonathan N. Adipocyte prolactin: regulation of release and putative functions. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007, 9, 464–76. [CrossRef]

- Macotela Y, Triebel J, Clapp C. Time for a New Perspective on Prolactin in Metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2020, 31, 276–286. [CrossRef]

- Pirchio R, Graziadio C, Colao A, Pivonello R, Auriemma RS. Metabolic effects of prolactin. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 1015520. [CrossRef]

- Breves JP, Popp EE, Rothenberg EF, Rosenstein CW, Maffett KM, Guertin RR. Osmoregulatory actions of prolactin in the gastrointestinal tract of fishes. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2020, 298, 113589. [CrossRef]

- Foitzik K, Krause K, Conrad F, Nakamura M, Funk W, Paus R. Human scalp hair follicles are both a target and a source of prolactin, which serves as an autocrine and/or paracrine promoter of apoptosis-driven hair follicle regression. Am J Pathol. 2006, 168, 748–56. [CrossRef]

- Langan EA, Ramot Y, Hanning A, Poeggeler B, Bíró T, Gaspar E, Funk W, Griffiths CE, Paus R. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone and oestrogen differentially regulate prolactin and prolactin receptor expression in female human skin and hair follicles in vitro. Br J Dermatol. 2010, 162, 1127–31. [CrossRef]

- Torner, L. Actions of Prolactin in the Brain: From Physiological Adaptations to Stress and Neurogenesis to Psychopathology. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2016, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba VV, Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. Prolactin and Autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 73. [CrossRef]

- Rasmi Y, Jalali L, Khalid S, Shokati A, Tyagi P, Ozturk A, Nasimfar A. The effects of prolactin on the immune system, its relationship with the severity of COVID-19, and its potential immunomodulatory therapeutic effect. Cytokine. 2023, 169, 156253. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Espinosa P, Méndez I, Irles C, Olmos-Ortiz A, Helguera-Repetto C, Mancilla-Herrera I, Ortuño-Sahagún D, Goffin V, Zaga-Clavellina V. Immunomodulatory role of decidual prolactin on the human fetal membranes and placenta. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1212736. [CrossRef]

- Goffin, V. Prolactin receptor targeting in breast and prostate cancers: New insights into an old challenge. Pharmacol Ther. 2017, 179, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standing D, Dandawate P, Anant S. Prolactin receptor signaling: A novel target for cancer treatment - Exploring anti-PRLR signaling strategies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023, 13, 1112987. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jonathan N, Liby K, McFarland M, Zinger M. Prolactin as an autocrine/paracrine growth factor in human cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 13, 245–50. [CrossRef]

- Harris J, Stanford PM, Oakes SR, Ormandy CJ. Prolactin and the prolactin receptor: new targets of an old hormone. Ann Med. 2004, 36, 414–25. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, CL. Molecular mechanisms of prolactin and its receptor. Endocr Rev. 2012, 33, 504–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorvin, CM. The prolactin receptor: Diverse and emerging roles in pathophysiology. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015, 2, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano RJ, Ben-Jonathan N. Minireview: Extrapituitary prolactin: an update on the distribution, regulation, and functions. Mol Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 622–33. [CrossRef]

- Featherstone K, White MR, Davis JR. The prolactin gene: a paradigm of tissue-specific gene regulation with complex temporal transcription dynamics. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012, 24, 977–90. [CrossRef]

- Perks CM, Newcomb PV, Grohmann M, Wright RJ, Mason HD, Holly JM. Prolactin acts as a potent survival factor against C2-ceramide-induced apoptosis in human granulosa cells. Hum Reprod. 2003, 18, 2672–7. [CrossRef]

- Schwärzler P, Untergasser G, Hermann M, Dirnhofer S, Abendstein B, Berger P. Prolactin gene expression and prolactin protein in premenopausal and postmenopausal human ovaries. Fertil Steril. 1997, 68, 696–701. [CrossRef]

- Vlahos NP, Bugg EM, Shamblott MJ, Phelps JY, Gearhart JD, Zacur HA. Prolactin receptor gene expression and immunolocalization of the prolactin receptor in human luteinized granulosa cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001, 7, 1033–8. [CrossRef]

- Porter MB, Brumsted JR, Sites CK. Effect of prolactin on follicle-stimulating hormone receptor binding and progesterone production in cultured porcine granulosa cells. Fertil Steril. 2000, 73, 99–105. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jonathan N, LaPensee CR, LaPensee EW. What can we learn from rodents about prolactin in humans? Endocr Rev. 2008, 29, 1–41. [CrossRef]

- Munro MG, Balen AH, Cho S, Critchley HOD, Díaz I, Ferriani R, Henry L, Mocanu E, van der Spuy ZM; FIGO Committee on Menstrual Disorders and Related Health Impacts, and FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, Endocrinology, and Infertility. The FIGO Ovulatory Disorders Classification System. Hum Reprod. 2022, 37, 2446–2464. [CrossRef]

- Vander Borght M, Wyns C. Fertility and infertility: Definition and epidemiology. Clin Biochem. 2018, 62, 2–10. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar A, Mangal NS. Hyperprolactinemia. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2013, 6, 168–75. [CrossRef]

- Štelcl M, Vrublovský P, Machač Š. Prolactin and alteration of fertility. Ceska Gynekol. 2018, 83, 232–235.

- Iancu ME, Albu AI, Albu DN. Prolactin Relationship with Fertility and In Vitro Fertilization Outcomes-A Review of the Literature. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023, 16, 122. [CrossRef]

- Keeler C, Dannies PS, Hodsdon ME. The tertiary structure and backbone dynamics of human prolactin. J Mol Biol. 2003, 328, 1105–21. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, YN. Structural variants of prolactin: occurrence and physiological significance. Endocr Rev. 1995, 16, 354–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horseman ND, Yu-Lee LY. Transcriptional regulation by the helix bundle peptide hormones: growth hormone, prolactin, and hematopoietic cytokines. Endocr Rev. 1994, 15, 627–49. [CrossRef]

- Corbacho AM, Martínez De La Escalera G, Clapp C. Roles of prolactin and related members of the prolactin/growth hormone/placental lactogen family in angiogenesis. J Endocrinol. 2002, 173, 219–38. [CrossRef]

- Owerbach D, Rutter WJ, Cooke NE, Martial JA, Shows TB. The prolactin gene is located on chromosome 6 in humans. Science. 1981, 212, 815–6. [CrossRef]

- McNamara AV, Awais R, Momiji H, Dunham L, Featherstone K, Harper CV, Adamson AA, Semprini S, Jones NA, Spiller DG, Mullins JJ, Finkenstädt BF, Rand D, White MRH, Davis JRE. Transcription Factor Pit-1 Affects Transcriptional Timing in the Dual-Promoter Human Prolactin Gene. Endocrinology. 2021, 162, bqaa249. [CrossRef]

- Trott JF, Hovey RC, Koduri S, Vonderhaar BK. Alternative splicing to exon 11 of human prolactin receptor gene results in multiple isoforms including a secreted prolactin-binding protein. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003, 30, 31–47. [CrossRef]

- Kasum M, Orešković S, Čehić E, Šunj M, Lila A, Ejubović E. Laboratory and clinical significance of macroprolactinemia in women with hyperprolactinemia. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017, 56, 719–724. [CrossRef]

- Vilar L, Vilar CF, Lyra R, Freitas MDC. Pitfalls in the Diagnostic Evaluation of Hyperprolactinemia. Neuroendocrinology. 2019, 109, 7–19. [CrossRef]

- Thirunavakkarasu K, Dutta P, Sridhar S, Dhaliwal L, Prashad GR, Gainder S, Sachdeva N, Bhansali A. Macroprolactinemia in hyperprolactinemic infertile women. Endocrine. 2013, 44, 750–5. [CrossRef]

- Koniares K, Benadiva C, Engmann L, Nulsen J, Grow D. Macroprolactinemia: a mini-review and update on clinical practice. F S Rep. 2023, 4, 245–250. [CrossRef]

- Kasum M, Pavičić-Baldani D, Stanić P, Orešković S, Sarić JM, Blajić J, Juras J. Importance of macroprolactinemia in hyperprolactinemia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014, 183, 28–32. [CrossRef]

- Bugge K, Papaleo E, Haxholm GW, Hopper JT, Robinson CV, Olsen JG, Lindorff-Larsen K, Kragelund BB. A combined computational and structural model of the full-length human prolactin receptor. Nat Commun. 2016, 7, 11578. [CrossRef]

- Araya-Secchi R, Bugge K, Seiffert P, Petry A, Haxholm GW, Lindorff-Larsen K, Pedersen SF, Arleth L, Kragelund BB. The prolactin receptor scaffolds Janus kinase 2 via co-structure formation with phosphoinositide-4,5-bisphosphate. Elife. 2023, 12, e84645. [CrossRef]

- Lee SA, Haiman CA, Burtt NP, Pooler LC, Cheng I, Kolonel LN, Pike MC, Altshuler D, Hirschhorn JN, Henderson BE, Stram DO. A comprehensive analysis of common genetic variation in prolactin (PRL) and PRL receptor (PRLR) genes in relation to plasma prolactin levels and breast cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort. BMC Med Genet. 2007, 8, 72. [CrossRef]

- Gorvin CM, Newey PJ, Thakker RV. Identification of prolactin receptor variants with diverse effects on receptor signalling. J Mol Endocrinol. 2023, 70, e220164. [CrossRef]

- Dagil R, Knudsen MJ, Olsen JG, O'Shea C, Franzmann M, Goffin V, Teilum K, Breinholt J, Kragelund BB. The WSXWS motif in cytokine receptors is a molecular switch involved in receptor activation: insight from structures of the prolactin receptor. Structure. 2012, 20, 270–82. [CrossRef]

- Bole-Feysot C, Goffin V, Edery M, Binart N, Kelly PA. Prolactin (PRL) and its receptor: actions, signal transduction pathways and phenotypes observed in PRL receptor knockout mice. Endocr Rev. 1998, 19, 225–68. [CrossRef]

- Fresno Vara JA, Carretero MV, Gerónimo H, Ballmer-Hofer K, Martín-Pérez J. Stimulation of c-Src by prolactin is independent of Jak2. Biochem J. 2000, 345 Pt 1(Pt 1), 17-24. [CrossRef]

- Kavarthapu R, Dufau ML.. Prolactin receptor gene transcriptional control, regulatory modalities relevant to breast cancer resistance and invasiveness. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 949396. [CrossRef]

- Haxholm GW, Nikolajsen LF, Olsen JG, Fredsted J, Larsen FH, Goffin V, Pedersen SF, Brooks AJ, Waters MJ, Kragelund BB. Intrinsically disordered cytoplasmic domains of two cytokine receptors mediate conserved interactions with membranes. Biochem J. 2015, 468, 495–506. [CrossRef]

- Hu ZZ, Meng J, Dufau ML.. Isolation and characterization of two novel forms of the human prolactin receptor generated by alternative splicing of a newly identified exon 11. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276, 41086–94. [CrossRef]

- Tsai-Morris CH, Dufau ML. PRLR (prolactin receptor). In: Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol (2011). Available at: http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/gene/42891/.

- Abramicheva PA, Smirnova OV. Prolactin Receptor Isoforms as the Basis of Tissue-Specific Action of Prolactin in the Norm and Pathology. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2019, 84, 329–345. [CrossRef]

- Berthon P, Kelly PA, Djiane J. Water-soluble prolactin receptors from porcine mammary gland. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1987, 184, 300–6. [CrossRef]

- Postel-Vinay MC, Belair L, Kayser C, Kelly PA, Djiane J. Identification of prolactin and growth hormone binding proteins in rabbit milk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991, 88, 6687–90. [CrossRef]

- Ezoe K, Miki T, Ohata K, Fujiwara N, Yabuuchi A, Kobayashi T, Kato K. Prolactin receptor expression and its role in trophoblast outgrowth in human embryos. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021, 42, 699–707. [CrossRef]

- Utama FE, Tran TH, Ryder A, LeBaron MJ, Parlow AF, Rui H. Insensitivity of human prolactin receptors to nonhuman prolactins: relevance for experimental modeling of prolactin receptor-expressing human cells. Endocrinology. 2009, 150, 1782–90. [CrossRef]

- Pezet A, Buteau H, Kelly PA, Edery M. The last proline of Box 1 is essential for association with JAK2 and functional activation of the prolactin receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997, 129, 199–208. [CrossRef]

- Brockman JL, Schuler LA. Prolactin signals via Stat5 and Oct-1 to the proximal cyclin D1 promoter. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005, 239(1-2):45-53. [CrossRef]

- Aksamitiene E, Achanta S, Kolch W, Kholodenko BN, Hoek JB, Kiyatkin A. Prolactin-stimulated activation of ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinases is controlled by PI3-kinase/Rac/PAK signaling pathway in breast cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2011, 23, 1794–805. [CrossRef]

- Derwich A, Sykutera M, Bromińska B, Rubiś B, Ruchała M, Sawicka-Gutaj N. The Role of Activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAF/MEK/ERK Pathways in Aggressive Pituitary Adenomas-New Potential Therapeutic Approach-A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 10952. [CrossRef]

- Bishop JD, Nien WL, Dauphinee SM, Too CK. Prolactin activates mammalian target-of-rapamycin through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and stimulates phosphorylation of p70S6K and 4E-binding protein-1 in lymphoma cells. J Endocrinol. 2006, 190, 307–12. [CrossRef]

- Hewetson A, Moore SL, Chilton BS. Prolactin signals through RUSH/SMARCA3 in the absence of a physical association with Stat5a. Biol Reprod. 2004, 71, 1907–12. [CrossRef]

- Hannan FM, Elajnaf T, Vandenberg LN, Kennedy SH, Thakker RV. Hormonal regulation of mammary gland development and lactation. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 46–61. [CrossRef]

- Auriemma RS, Del Vecchio G, Scairati R, Pirchio R, Liccardi A, Verde N, de Angelis C, Menafra D, Pivonello C, Conforti A, Alviggi C, Pivonello R, Colao A. The Interplay Between Prolactin and Reproductive System: Focus on Uterine Pathophysiology. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020, 11, 594370. [CrossRef]

- Auriemma RS, Pirchio R, Pivonello C, Garifalos F, Colao A, Pivonello R. Approach to the Patient With Prolactinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023, 108, 2400–2423. [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki M, Welt CK. PRL Mutation Causing Alactogenesis: Insights Into Prolactin Structure and Function Relationships. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021, 106, e3021–e3026. [CrossRef]

- Naylor MJ, Lockefeer JA, Horseman ND, Ormandy CJ. Prolactin regulates mammary epithelial cell proliferation via autocrine/paracrine mechanism. Endocrine. 2003, 20(1-2), 111-4. [CrossRef]

- Gabrielson M, Ubhayasekera K, Ek B, Andersson Franko M, Eriksson M, Czene K, Bergquist J, Hall P. Inclusion of Plasma Prolactin Levels in Current Risk Prediction Models of Premenopausal and Postmenopausal Breast Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018 Dec 4;2, pky055. [CrossRef]

- Sackmann-Sala L, Guidotti JE, Goffin V. Minireview: prolactin regulation of adult stem cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2015, 29, 667–81. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Membrillo M, Siqueiros-Márquez L, Núñez FF, Díaz-Lezama N, Adán-Castro E, Ramírez-Hernández G, Adán N, Macotela Y, Martínez de la Escalera G, Clapp C. Prolactin stimulates the vascularisation of the retina in newborn mice under hyperoxia conditions. J Neuroendocrinol. 2020, 32, e12858. [CrossRef]

- Yousefvand S, Hadjzadeh MA, Vafaee F, Dolatshad H. The protective effects of prolactin on brain injury. Life Sci. 2020, 263, 118547. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Salinas G, Rivero-Segura NA, Cabrera-Reyes EA, Rodríguez-Chávez V, Langley E, Cerbon M. Decoding signaling pathways involved in prolactin-induced neuroprotection: A review. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 61, 100913. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Chavez V, Moran J, Molina-Salinas G, Zepeda Ruiz WA, Rodriguez MC, Picazo O, Cerbon M. Participation of Glutamatergic Ionotropic Receptors in Excitotoxicity: The Neuroprotective Role of Prolactin. Neuroscience. 2021, 461:180-193. [CrossRef]

- Clevenger CV, Rui H. Breast Cancer and Prolactin - New Mechanisms and Models. Endocrinology. 2022, 163, bqac122. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-de-Arellano A, Villegas-Pineda JC, Hernández-Silva CD, Pereira-Suárez AL. The Relevant Participation of Prolactin in the Genesis and Progression of Gynecological Cancers. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021, 12:747810. [CrossRef]

- Baeyens L, Hindi S, Sorenson RL, German MS. β-Cell adaptation in pregnancy. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016, 18 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):63-70. [CrossRef]

- Al-Nami MS, Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Al-Mamoori F. Metabolic profile and prolactin serum levels in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Old-new rubric. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2019, 9, 120–126. [CrossRef]

- Zhu C, Wen X, You H, Lu L, Du L, Qian C. Improved Insulin Secretion Response and Beta-cell Function Correlated with Increased Prolactin Levels After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy in Morbidly Obese Patients with Acanthosis Nigricans. Obes Surg. 2023, 33, 2405–2419. [CrossRef]

- Retnakaran R, Ye C, Kramer CK, Connelly PW, Hanley AJ, Sermer M, Zinman B. Maternal Serum Prolactin and Prediction of Postpartum β-Cell Function and Risk of Prediabetes/Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016, 39, 1250–8. [CrossRef]

- Rassie K, Giri R, Joham AE, Mousa A, Teede H. Prolactin in relation to gestational diabetes and metabolic risk in pregnancy and postpartum: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13:1069625. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Lu J, Xu Y, Li M, Sun J, Zhang J, Xu B, Xu M, Chen Y, Bi Y, Wang W, Ning G. Circulating prolactin associates with diabetes and impaired glucose regulation: a population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2013, 36, 1974–80. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Lin J, Li H, Liu Z, Chen X, Chen Q. Prolactin Is Associated With Insulin Resistance and Beta-Cell Dysfunction in Infertile Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021, 12:571229. [CrossRef]

- Rasheed HA, Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Hussien NR, Al-Nami MS. Effects of diabetic pharmacotherapy on prolactin hormone in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Bane or Boon. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2019, 10, 163–168. [CrossRef]

- Shao S, Yao Z, Lu J, Song Y, He Z, Yu C, Zhou X, Zhao L, Zhao J, Gao L.. Ablation of prolactin receptor increases hepatic triglyceride accumulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018, 498, 693–699. [CrossRef]

- de Winne C, Pascual FL, Lopez-Vicchi F, Etcheverry-Boneo L, Mendez-Garcia LF, Ornstein AM, Lacau-Mengido IM, Sorianello E, Becu-Villalobos D. Neuroendocrine control of brown adipocyte function by prolactin and growth hormone. J Neuroendocrinol. 2023:e13248. [CrossRef]

- Ghoreshi ZA, Akbari H, Sharif-Zak M, Arefinia N, Abbasi-Jorjandi M, Asadikaram G. Recent findings on hyperprolactinemia and its pathological implications: a literature review. J Investig Med. 2022, 70, 1443–1451. [CrossRef]

- Corona G, Rastrelli G, Comeglio P, Guaraldi F, Mazzatenta D, Sforza A, Vignozzi L, Maggi M. The metabolic role of prolactin: systematic review, meta-analysis and preclinical considerations. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2022, 17, 533–545. [CrossRef]

- Xu P, Zhu Y, Ji X, Ma H, Zhang P, Bi Y. Lower serum PRL is associated with the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 523. [CrossRef]

- Deachapunya C, Poonyachoti S, Krishnamra N. Regulation of electrolyte transport across cultured endometrial epithelial cells by prolactin. J Endocrinol. 2008, 197, 575–82. [CrossRef]

- Radojkovic D, Pesic M, Radojkovic M, Dimic D, Vukelic Nikolic M, Jevtovic Stoimenov T, Radenkovic S, Velojic Golubovic M, Radjenovic Petkovic T, Antic S. Expression of prolactin receptors in the duodenum, kidneys and skeletal system during physiological and sulpiride-induced hyperprolactinaemia. Endocrine. 2018, 62, 681–691. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra F, Crambert S, Eklöf AC, Lundquist A, Hansell P, Holtbäck U. Prolactin, a natriuretic hormone, interacting with the renal dopamine system. Kidney Int. 2005, 68, 1700–7. [CrossRef]

- Crambert S, Sjöberg A, Eklöf AC, Ibarra F, Holtbäck U. Prolactin and dopamine 1-like receptor interaction in renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010, 299, F49–54. [CrossRef]

- Georgescu T, Swart JM, Grattan DR, Brown RSE. The Prolactin Family of Hormones as Regulators of Maternal Mood and Behavior. Front Glob Womens Health. 2021, 2:767467. [CrossRef]

- Faron-Górecka A, Latocha K, Pabian P, Kolasa M, Sobczyk-Krupiarz I, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M. The Involvement of Prolactin in Stress-Related Disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023, 20, 3257. [CrossRef]

- Reavley A, Fisher AD, Owen D, Creed FH, Davis JR. Psychological distress in patients with hyperprolactinaemia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997, 47, 343–8. [CrossRef]

- Elgellaie A, Larkin T, Kaelle J, Mills J, Thomas S. Plasma prolactin is higher in major depressive disorder and females, and associated with anxiety, hostility, somatization, psychotic symptoms and heart rate. Compr Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2021, 6:100049. [CrossRef]

- Telfer EE, Grosbois J, Odey YL, Rosario R, Anderson RA. Making a good egg: human oocyte health, aging, and in vitro development. Physiol Rev. 2023, 103, 2623–2677. [CrossRef]

- Marques P, Skorupskaite K, Rozario KS, et al. Physiology of GnRH and Gonadotropin Secretion. [Updated 2022 Jan 5]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279070/.

- Marshall JC, Dalkin AC, Haisenleder DJ, Paul SJ, Ortolano GA, Kelch RP. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulses: regulators of gonadotropin synthesis and ovulatory cycles. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1991, 47:155-87; discussion 188-9. [CrossRef]

- Orlowski M, Sarao MS. Physiology, Follicle Stimulating Hormone. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535442/. 1 May.

- Reed BG, Carr BR. The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation. [Updated 2018 Aug 5]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/.

- Nedresky D, Singh G. Physiology, Luteinizing Hormone. [Updated 2022 Sep 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539692/.

- Cable JK, Grider MH. Physiology, Progesterone. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558960/. 1 May.

- Findlay JK, Drummond AE, Dyson M, Baillie AJ, Robertson DM, Ethier JF. Production and actions of inhibin and activin during folliculogenesis in the rat. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001, 180(1-2):139-44. [CrossRef]

- Namwanje M, Brown CW. Activins and Inhibins: Roles in Development, Physiology, and Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016, 8, a021881. [CrossRef]

- Roseff SJ, Bangah ML, Kettel LM, Vale W, Rivier J, Burger HG, Yen SS. Dynamic changes in circulating inhibin levels during the luteal-follicular transition of the human menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989, 69, 1033–9. [CrossRef]

- Welt CK, Schneyer AL.. Differential regulation of inhibin B and inhibin a by follicle-stimulating hormone and local growth factors in human granulosa cells from small antral follicles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001, 86, 330–6. [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzzi RJ, Baird DT, Campbell BK, Driancourt MA, Dupont J, Fortune JE, Gilchrist RB, Martin GB, McNatty KP, McNeilly AS, Monget P, Monniaux D, Viñoles C, Webb R. Regulation of folliculogenesis and the determination of ovulation rate in ruminants. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2011, 23, 444–67. [CrossRef]

- Lundy T, Smith P, O'Connell A, Hudson NL, McNatty KP. Populations of granulosa cells in small follicles of the sheep ovary. J Reprod Fertil. 1999 ;115, 251-62. [CrossRef]

- Dunlop CE, Anderson RA. The regulation and assessment of follicular growth. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2014, 244:13-7; discussion 17. [CrossRef]

- Gershon E, Dekel N. Newly Identified Regulators of Ovarian Folliculogenesis and Ovulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 4565. [CrossRef]

- Evans AC, Fortune JE. Selection of the dominant follicle in cattle occurs in the absence of differences in the expression of messenger ribonucleic acid for gonadotropin receptors. Endocrinology. 1997, 138, 2963–71. [CrossRef]

- de Andrade LG, Portela VM, Dos Santos EC, Aires KV, Ferreira R, Missio D, da Silva Z, Koch J, Antoniazzi AQ, Gonçalves PBD, Zamberlam G. FSH Regulates YAP-TEAD Transcriptional Activity in Bovine Granulosa Cells to Allow the Future Dominant Follicle to Exert Its Augmented Estrogenic Capacity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 14160. [CrossRef]

- Casarini L, Paradiso E, Lazzaretti C, D'Alessandro S, Roy N, Mascolo E, Zaręba K, García-Gasca A, Simoni M. Regulation of antral follicular growth by an interplay between gonadotropins and their receptors. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2022, 39, 893–904. [CrossRef]

- Rosen MP, Zamah AM, Shen S, Dobson AT, McCulloch CE, Rinaudo PF, Lamb JD, Cedars MI. The effect of follicular fluid hormones on oocyte recovery after ovarian stimulation: FSH level predicts oocyte recovery. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009, 7:35. [CrossRef]

- Chauvin S, Cohen-Tannoudji J, Guigon CJ. Estradiol Signaling at the Heart of Folliculogenesis: Its Potential Deregulation in Human Ovarian Pathologies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 512. [CrossRef]

- Stringer JM, Alesi LR, Winship AL, Hutt KJ. Beyond apoptosis: evidence of other regulated cell death pathways in the ovary throughout development and life. Hum Reprod Update. 2023, 29, 434–456. [CrossRef]

- Shelling AN, Ahmed Nasef N. The Role of Lifestyle and Dietary Factors in the Development of Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023, 12, 1601. [CrossRef]

- Sun YC, Wang YY, Sun XF, Cheng SF, Li L, Zhao Y, Shen W, Chen H. The role of autophagy during murine primordial follicle assembly. Aging (Albany NY). 2018, 10, 197–211. [CrossRef]

- Schuh-Huerta SM, Johnson NA, Rosen MP, Sternfeld B, Cedars MI, Reijo Pera RA. Genetic markers of ovarian follicle number and menopause in women of multiple ethnicities. Hum Genet. 2012, 131, 1709–24. [CrossRef]

- Irving-Rodgers HF, van Wezel IL, Mussard ML, Kinder JE, Rodgers RJ. Atresia revisited: two basic patterns of atresia of bovine antral follicles. Reproduction. 2001, 122, 761–75.

- Zhou J, Peng X, Mei S. Autophagy in Ovarian Follicular Development and Atresia. Int J Biol Sci. 2019, 15, 726–737. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Shi X, Shi Y, Wang Z. The Signaling Pathways Involved in Ovarian Follicle Development. Front Physiol. 2021, 12:730196. [CrossRef]

- Gellersen B, Brosens JJ. Cyclic decidualization of the human endometrium in reproductive health and failure. Endocr Rev. 2014, 35, 851–905. [CrossRef]

- Baerwald A, Pierson R. Ovarian follicular waves during the menstrual cycle: physiologic insights into novel approaches for ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2020, 114, 443–457. [CrossRef]

- Bulletti C, Bulletti FM, Sciorio R, Guido M. Progesterone: The Key Factor of the Beginning of Life. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 14138. [CrossRef]

- Klusmann H, Schulze L, Engel S, Bücklein E, Daehn D, Lozza-Fiacco S, Geiling A, Meyer C, Andersen E, Knaevelsrud C, Schumacher S. HPA axis activity across the menstrual cycle - a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2022, 66: 100998. [CrossRef]

- Javed Z, Qamar U, Sathyapalan T. The role of kisspeptin signalling in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis--current perspective. Endokrynol Pol. 2015, 66, 534–47. [CrossRef]

- 145 Skorupskaite K, George JT, Anderson RA. The kisspeptin-GnRH pathway in human reproductive health and disease. Hum Reprod Update. 2014, 20, 485–500. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson H, Bartram S, Charalambides MM, Murthy S, Petitt T, Pradeep A, Vineall O, Abaraonye I, Lancaster A, Koysombat K, Patel B, Abbara A. Kisspeptin-neuron control of LH pulsatility and ovulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13:951938. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, AS. Neuroendocrine mechanisms underlying estrogen positive feedback and the LH surge. Front Neurosci. 2022, 16:953252. [CrossRef]

- Tsukamura, H. Kobayashi Award 2019: The neuroendocrine regulation of the mammalian reproduction. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2022, 315:113755. [CrossRef]

- Welt, CK. Regulation and function of inhibins in the normal menstrual cycle. Semin Reprod Med. 2004, 22, 187–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namwanje M, Brown CW. Activins and Inhibins: Roles in Development, Physiology, and Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016, 8, a021881. [CrossRef]

- Perakakis N, Upadhyay J, Ghaly W, Chen J, Chrysafi P, Anastasilakis AD, Mantzoros CS. Regulation of the activins-follistatins-inhibins axis by energy status: Impact on reproductive function. Metabolism. 2018, 85:240-249. [CrossRef]

- Tumurgan Z, Kanasaki H, Tumurbaatar T, Oride A, Okada H, Hara T, Kyo S. Role of activin, follistatin, and inhibin in the regulation of Kiss-1 gene expression in hypothalamic cell models. Biol Reprod. 2019, 101, 405–415. [CrossRef]

- Oxford Handbook of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. Editor: Drew Provan; 4th edition (2018); Oxford University Press New York, USA.

- Sikaris, KA. Enhancing the Clinical Value of Medical Laboratory Testing. Clin Biochem Rev. 2017, 38, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sperduti S, Limoncella S, Lazzaretti C, Paradiso E, Riccetti L, Turchi S, Ferrigno I, Bertacchini J, Palumbo C, Potì F, Longobardi S, Millar RP, Simoni M, Newton CL, Casarini L.. GnRH Antagonists Produce Differential Modulation of the Signaling Pathways Mediated by GnRH Receptors. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 5548. [CrossRef]

- Choi, D. Evolutionary Viewpoint on GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) in Chordata - Amino Acid and Nucleic Acid Sequences. Dev Reprod. 2018, 22, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris HA, Shupnik MA. Mechanisms for pulsatile regulation of the gonadotropin subunit genes by GNRHBiol Reprod. 2006, 74, 993–8. [CrossRef]

- Nippoldt TB, Reame NE, Kelch RP, Marshall JC. The roles of estradiol and progesterone in decreasing luteinizing hormone pulse frequency in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989, 69, 67–76. [CrossRef]

- Romano GJ, Krust A, Pfaff DW. Expression and estrogen regulation of progesterone receptor mRNA in neurons of the mediobasal hypothalamus: an in situ hybridization study. Mol Endocrinol. 1989, 3, 1295–300, Erratum in: Mol Endocrinol 1989, 3, 1860. [CrossRef]

- Soules MR, Steiner RA, Clifton DK, Cohen NL, Aksel S, Bremner WJ. Progesterone modulation of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in normal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984, 58, 378–83. [CrossRef]

- Berga SL, Yen SS. Opioidergic regulation of LH pulsatility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1989, 30, 177–84. [CrossRef]

- Neal-Perry G, Lebesgue D, Lederman M, Shu J, Zeevalk GD, Etgen AM. The excitatory peptide kisspeptin restores the luteinizing hormone surge and modulates amino acid neurotransmission in the medial preoptic area of middle-aged rats. Endocrinology. 2009, 150, 3699–708. [CrossRef]

- Araki S, Takanashi N, Chikazawa K, Motoyama M, Akabori A, Konuma S, Tamada T. Reevaluation of immunoreactive gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) levels in general circulation in women: changes in levels and episodic patterns before, during and after gonadotropin surges. Endocrinol Jpn. 1986, 33, 457–68. [CrossRef]

- Andersen CY, Ezcurra D. Human steroidogenesis: implications for controlled ovarian stimulation with exogenous gonadotropins. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2014, 12:128. [CrossRef]

- Dias JA, Ulloa-Aguirre A. New Human Follitropin Preparations: How Glycan Structural Differences May Affect Biochemical and Biological Function and Clinical Effect. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021, 12:636038. [CrossRef]

- Bousfield GR, Butnev VY, White WK, Hall AS, Harvey DJ. Comparison of Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Glycosylation Microheterogenity by Quantitative Negative Mode Nano-Electrospray Mass Spectrometry of Peptide-N Glycanase-Released Oligosaccharides. J Glycomics Lipidomics. 2015, 5, 129. [CrossRef]

- Fink, G., Gonadotropin secretion and its control, in The physiology of reproduction, E. Knobil, J.D. Neill, and et al., Editors. 1988, Raven: New York. p. 1349-1377.

- Oduwole OO, Huhtaniemi IT, Misrahi M. The Roles of Luteinizing Hormone, Follicle-Stimulating Hormone and Testosterone in Spermatogenesis and Folliculogenesis Revisited. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 12735. [CrossRef]

- Amsterdam A, Rotmensch S. Structure-function relationships during granulosa cell differentiation. Endocr Rev. 1987, 8, 309–37. [CrossRef]

- Larson SB, McPherson A. The crystal structure of the β subunit of luteinizing hormone and a model for the intact hormone. Curr Res Struct Biol. 2019, 1:1-5. [CrossRef]

- Filicori, M. The role of luteinizing hormone in folliculogenesis and ovulation induction. Fertil Steril. 1999, 71, 405–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar P, Sait SF. Luteinizing hormone and its dilemma in ovulation induction. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2011, 4, 2–7. [CrossRef]

- Duffy DM, Ko C, Jo M, Brannstrom M, Curry TE. Ovulation: Parallels With Inflammatory Processes. Endocr Rev. 2019, 40, 369–416. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on the Clinical Utility of Treating Patients with Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Replacement Therapy; Jackson LM, Parker RM, Mattison DR, editors. The Clinical Utility of Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Therapy: A Review of Safety, Effectiveness, and Use. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2020 Jul 1. 4, Reproductive Steroid Hormones: Synthesis, Structure, and Biochemistry. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562873/.

- Xu XL, Huang ZY, Yu K, Li J, Fu XW, Deng SL. Estrogen Biosynthesis and Signal Transduction in Ovarian Disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13:827032. [CrossRef]

- Daniel JM, Lindsey SH, Mostany R, Schrader LA, Zsombok A. Cardiometabolic health, menopausal estrogen therapy and the brain: How effects of estrogens diverge in healthy and unhealthy preclinical models of aging. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2023, 70:101068. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty B, Byemerwa J, Krebs T, Lim F, Chang CY, McDonnell DP. Estrogen Receptor Signaling in the Immune System. Endocr Rev. 2023, 44, 117–141. [CrossRef]

- Kim HJJ, Dickie SA, Laprairie RB. Estradiol-dependent hypocretinergic/orexinergic behaviors throughout the estrous cycle. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2023, 240, 15–25. [CrossRef]

- Bühler M, Stolz A. Estrogens-Origin of Centrosome Defects in Human Cancer? Cells. 2022, 11, 432. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton KJ, Arao Y, Korach KS. Estrogen hormone physiology: reproductive findings from estrogen receptor mutant mice. Reprod Biol. 2014, 14, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Christenson LK, Devoto L. Cholesterol transport and steroidogenesis by the corpus luteum. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003, 1:90. [CrossRef]

- Ng SW, Norwitz GA, Pavlicev M, Tilburgs T, Simón C, Norwitz ER. Endometrial Decidualization: The Primary Driver of Pregnancy Health. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 4092. [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, RC. Progesterone synthesis by the human placenta. Placenta. 2005, 26, 273–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson DM, Cahir N, Findlay JK, Burger HG, Groome N. The biological and immunological characterization of inhibin A and B forms in human follicular fluid and plasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997, 82, 889–96. [CrossRef]

- Walton KL, Makanji Y, Wilce MC, Chan KL, Robertson DM, Harrison CA. A common biosynthetic pathway governs the dimerization and secretion of inhibin and related transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta) ligands. J Biol Chem. 2009, 284, 9311–20. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Shao LE, Lemas V, Yu AL, Vaughan J, Rivier J, Vale W. Importance of FSH-releasing protein and inhibin in erythrodifferentiation. Nature. 1987, 330, 765–7. [CrossRef]

- Vassalli A, Matzuk MM, Gardner HA, Lee KF, Jaenisch R. Activin/inhibin beta B subunit gene disruption leads to defects in eyelid development and female reproduction. Genes Dev. 1994, 8, 414–27. [CrossRef]

- Matzuk, MM. Functional analysis of mammalian members of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1995, 6, 120–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa M, Derynck R, Miyazono K. TGF-β and the TGF-β Family: Context-Dependent Roles in Cell and Tissue Physiology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016, 8, a021873. [CrossRef]

- Friis Wang N, Bogstad JW, Petersen MR, Pinborg A, Yding Andersen C, Løssl K. Androgen and inhibin B levels during ovarian stimulation before and after 8 weeks of low-dose hCG priming in women with low ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2023:dead134. [CrossRef]

- Sehested A, Juul AA, Andersson AM, Petersen JH, Jensen TK, Müller J, Skakkebaek NE. Serum inhibin A and inhibin B in healthy prepubertal, pubertal, and adolescent girls and adult women: relation to age, stage of puberty, menstrual cycle, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and estradiol levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000, 85, 1634–40. [CrossRef]

- Hillier, SG. Paracrine support of ovarian stimulation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009, 15, 843–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canipari R, Cellini V, Cecconi S. The ovary feels fine when paracrine and autocrine networks cooperate with gonadotropins in the regulation of folliculogenesis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012, 18, 245–55. [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan V, Cardoso RC. Neuroendocrine, autocrine, and paracrine control of follicle-stimulating hormone secretion. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2020, 500:110632. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi T, Ohnishi J. Molecular mechanism of follicle rupture during ovulation. Zoolog Sci. 1995, 12, 359–65. [CrossRef]

- Canipari R, Strickland S. Studies on the hormonal regulation of plasminogen activator production in the rat ovary. Endocrinology. 1986, 118, 1652–9. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Leung A. Gonadotropins regulate plasminogen activator production by rat granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1983, 112, 1201–7. [CrossRef]

- Lumsden MA, Kelly RW, Templeton AA, Van Look PF, Swanston IA, Baird DT. Changes in the concentration of prostaglandins in preovulatory human follicles after administration of hCG. J Reprod Fertil. 1986, 77, 119–24. [CrossRef]

- Espey LL, Tanaka N, Adams RF, Okamura H. Ovarian hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids compared with prostanoids and steroids during ovulation in rats. Am J Physiol. 1991, 260(2 Pt 1): E163-9. [CrossRef]

- Borba VV, Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. Prolactin and autoimmunity: The hormone as an inflammatory cytokine. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019, 33, 101324. [CrossRef]

- Hu S, Duggavathi R, Zadworny D. Regulatory Mechanisms Underlying the Expression of Prolactin Receptor in Chicken Granulosa Cells. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0170409. [CrossRef]

- Yang R, Duan C, Zhang S, Liu Y, Zhang Y. Prolactin Regulates Ovine Ovarian Granulosa Cell Apoptosis by Affecting the Expression of MAPK12 Gene. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 10269. [CrossRef]

- Legro, RS. The new International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification of ovulatory disorders: getting from here to there. Fertil Steril. 2023, 119, 560–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker MH, Tobler KJ. Female Infertility. [Updated 2022 Dec 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556033/.

- Munro MG, Balen AH, Cho S, Critchley HOD, Díaz I, Ferriani R, Henry L, Mocanu E, van der Spuy ZM; FIGO Committee on Menstrual Disorders and Related Health Impacts, and FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, Endocrinology, and Infertility. The FIGO ovulatory disorders classification system. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022, 159, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Agents stimulating gonadal function in the human. Report of a WHO scientific group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1973, 514:1-30.

- Urman B, Yakin K. Ovulatory disorders and infertility. J Reprod Med. 2006, 51, 267–82.

- Azziz, R. Introduction: Determinants of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2016, 106, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deswal R, Narwal V, Dang A, Pundir CS. The Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Brief Systematic Review. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2020, 13, 261–271. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Wu Q, Hao Y, Jiao M, Wang X, Jiang S, Han L.. Measuring the global disease burden of polycystic ovary syndrome in 194 countries: Global Burden of Disease Study Hum Reprod. 2021, 36, 1108–1119. [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava S, Conigliaro RL.. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 2023, 107, 227–234. [CrossRef]

- Smet ME, McLennan A. Rotterdam criteria, the end. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2018, 21, 59–60. [CrossRef]

- Szukiewicz D, Trojanowski S, Kociszewska A, Szewczyk G. Modulation of the Inflammatory Response in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)-Searching for Epigenetic Factors. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 14663. [CrossRef]

- Harada, M. Pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: Current understanding and perspectives regarding future research. Reprod Med Biol. 2022, 21, e12487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi Z, Araghi F, Vahedi M, Mokhtari N, Gheisari M. Prolactin Level in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): An approach to the diagnosis and management. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021291. [CrossRef]

- Kim SI, Yoon JH, Park DC, Yang SH, Kim YI. What is the optimal prolactin cutoff for predicting the presence of a pituitary adenoma in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome? Int J Med Sci. 2023, 20, 463–467. [CrossRef]

- Liu YX, Peng XR, Chen YJ, Carrico W, Ny T. Prolactin delays gonadotrophin-induced ovulation and down-regulates expression of plasminogen-activator system in ovary. Hum Reprod. 1997, 12, 2748–55. [CrossRef]

- Chang S, Copperman AB. New insights into human prolactin pathophysiology: genomics and beyond. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2019, 31, 207–211. [CrossRef]

- Thapa S, Bhusal K. Hyperprolactinemia. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537331/.

- Stojkovic M, Radmanovic B, Jovanovic M, Janjic V, Muric N, Ristic DI. Risperidone Induced Hyperprolactinemia: From Basic to Clinical Studies. Front Psychiatry. 2022, 13:874705. [CrossRef]

- Malik AA, Aziz F, Beshyah SA, Aldahmani KM. Aetiologies of Hyperprolactinaemia: A retrospective analysis from a tertiary healthcare centre. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2019, 19, e129–e134. [CrossRef]

- Aliberti L, Gagliardi I, Dorizzi RM, Pizzicotti S, Bondanelli M, Zatelli MC, Ambrosio MR. Hypeprolactinemia: still an insidious diagnosis. Endocrine. 2021, 72, 928–931. [CrossRef]

- Grattan DR, Steyn FJ, Kokay IC, Anderson GM, Bunn SJ. Pregnancy-induced adaptation in the neuroendocrine control of prolactin secretion. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008, 20, 497–507. [CrossRef]

- Kirk SE, Xie TY, Steyn FJ, Grattan DR, Bunn SJ. Restraint stress increases prolactin-mediated phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 in the hypothalamus and adrenal cortex in the male mouse. J Neuroendocrinol. 2017, 29. [CrossRef]

- Hackney AC, Saeidi A. The thyroid axis, prolactin, and exercise in humans. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2019, 9:45-50. [CrossRef]

- Mogavero MP, Cosentino FII, Lanuzza B, Tripodi M, Lanza G, Aricò D, DelRosso LM, Pizza F, Plazzi G, Ferri R. Increased Serum Prolactin and Excessive Daytime Sleepiness: An Attempt of Proof-of-Concept Study. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1574. [CrossRef]

- Kapcala LP, Lakshmanan MC. Thoracic stimulation and prolactin secretion. J Endocrinol Invest. 1989, 12, 815–21. [CrossRef]

- Nteeba J, Kubota K, Wang W, Zhu H, Vivian J, Dai G, Soares M. Pancreatic prolactin receptor signaling regulates maternal glucose homeostasis. J Endocrinol. 2019:JOE-18-0518.R2. [CrossRef]

- Krüger TH, Hartmann U, Schedlowski M. Prolactinergic and dopaminergic mechanisms underlying sexual arousal and orgasm in humans. World J Urol. 2005, 23, 130–8. [CrossRef]

- Samperi I, Lithgow K, Karavitaki N. Hyperprolactinaemia. J Clin Med. 2019, 8, 2203. [CrossRef]

- Shukla P, Bulsara KR, Luthra P. Pituitary Hyperplasia in Severe Primary Hypothyroidism: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019, 2019:2012546. [CrossRef]

- Dourado M, Cavalcanti F, Vilar L, Cantilino A. Relationship between Prolactin, Chronic Kidney Disease, and Cardiovascular Risk. Int J Endocrinol. 2020, 2020:9524839. [CrossRef]

- Adachi N, Lei B, Deshpande G, Seyfried FJ, Shimizu I, Nagaro T, Arai T. Uraemia suppresses central dopaminergic metabolism and impairs motor activity in rats. Intensive Care Med. 2001, 27, 1655–60. [CrossRef]

- Jha SK, Kannan S. Serum prolactin in patients with liver disease in comparison with healthy adults: A preliminary cross-sectional study. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2016, 6, 8–10. [CrossRef]

- Pekic S, Miljic D, Popovic V. Hypopituitarism Following Cranial Radiotherapy. [Updated 2021 Aug 9]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532082/. 5320.

- Niculescu DA, Gheorghiu ML, Poiana C. Radiotherapy in aggressive or dopamine agonists resistant prolactinomas; is it still worthwhile? Eur J Endocrinol. 2023, 188, R88–R97. [CrossRef]

- Rutberg L, Fridén B, Karlsson AK. Amenorrhoea in newly spinal cord injured women: an effect of hyperprolactinaemia? Spinal Cord. 2008, 46, 189–91. [CrossRef]

- Arinola E, Adeleye JO, Lawal OA, Oluwakemi BA. Hyperprolactinemia following traumatic myelopathy. African Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2022, 12, 93–95. [CrossRef]

- Hermann AL, Fell GL, Kemény LV, Fung CY, Held KD, Biggs PJ, Rivera PD, Bilbo SD, Igras V, Willers H, Kung J, Gheorghiu L, Hideghéty K, Mao J, Woolf CJ, Fisher DE. β-Endorphin mediates radiation therapy fatigue. Sci Adv. 2022, 8, eabn6025. [CrossRef]

- Panahi Y, Fathi E, Shafiian MA. The link between seizures and prolactin: A study on the effects of anticonvulsant medications on hyperprolactinemia in rats. Epilepsy Res. 2023, 196:107206. [CrossRef]

- Bahceci M, Tuzcu A, Bahceci S, Tuzcu S. Is hyperprolactinemia associated with insulin resistance in non-obese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome? J Endocrinol Invest. 2003, 26, 655–659. [CrossRef]

- Le Bescont A, Vitte AL, Debernardi A, Curtet S, Buchou T, Vayr J, de Reyniès A, Ito A, Guardiola P, Brambilla C, Yoshida M, Brambilla E, Rousseaux S, Khochbin S. Receptor-Independent Ectopic Activity of Prolactin Predicts Aggressive Lung Tumors and Indicates HDACi-Based Therapeutic Strategies. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Letson GW, Moore DC. Galactorrhea secondary to chest wall surgery in an adolescent. J Adolesc Health Care. 1984, 5, 277–8. [CrossRef]

- Bushe C, Shaw M, Peveler RC. A review of the association between antipsychotic use and hyperprolactinaemia. J Psychopharmacol. 2008, 22(2 Suppl):46-55. [CrossRef]

- Junqueira DR, Bennett D, Huh SY, Casañas I Comabella C. Clinical Presentations of Drug-Induced Hyperprolactinaemia: A Literature Review. Pharmaceut Med. 2023, 37, 153–166. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Jeong JH, Um YH, Kim TW, Seo HJ, Hong SC. Prolactin Level Changes according to Atypical Antipsychotics Use: A Study Based on Clinical Data Warehouse. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2023, 21, 769–777. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee S, Biswas R, Mandal N. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced galactorrhea with hyperprolactinemia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2021, 63, 613–616. [CrossRef]

- Ashbury JE, Lévesque LE, Beck PA, Aronson KJ. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Antidepressants, Prolactin and Breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2012, 2:177. [CrossRef]

- Torre DL, Falorni A. Pharmacological causes of hyperprolactinemia. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007, 3, 929–51.

- Rodier C, Courbière B, Fernandes S, Vermalle M, Florence B, Resseguier N, Brue T, Cuny T. Metoclopramide Test in Hyperprolactinemic Women With Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: Old Wine Into New Bottles? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13:832361. [CrossRef]

- Kertesz E, Somoza GM, D'Eramo JL, Libertun C. Further evidence for endogenous hypothalamic serotonergic neurons involved in the cimetidine-induced prolactin release in the rat. Brain Res. 1987, 413, 10–4. [CrossRef]

- Meltzer HY, Maes M, Lee MA. The cimetidine-induced increase in prolactin secretion in schizophrenia: effect of clozapine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1993, 112(1 Suppl):S95-104. [CrossRef]

- Gupta M, Al Khalili Y. Methyldopa. 2023. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–.

- Kelley SR, Kamal TJ, Molitch ME. Mechanism of verapamil calcium channel blockade-induced hyperprolactinemia. Am J Physiol. 1996, 270(1 Pt 1):E96-100. [CrossRef]

- Veselinović T, Schorn H, Vernaleken IB, Schiffl K, Klomp M, Gründer G. Impact of different antidopaminergic mechanisms on the dopaminergic control of prolactin secretion. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011, 31, 214–20. [CrossRef]

- Ren N, Carratala-Ros C, Ecevitoglu A, Rotolo RA, Edelstein GA, Presby RE, Stevenson IH, Chrobak JJ, Salamone JD. Effects of the dopamine depleting agent tetrabenazine on detailed temporal parameters of effort-related choice responding. J Exp Anal Behav. 2022, 117, 331–345. [CrossRef]

- Enjalbert A, Ruberg M, Arancibia S, Priam M, Kordon C. Endogenous opiates block dopamine inhibition of prolactin secretion in vitro. Nature 1979, 280:595–597. [CrossRef]

- Arbogast LA, Voogt JL.. Endogenous opioid peptides contribute to suckling-induced prolactin release by suppressing tyrosine hydroxylase activity and messenger ribonucleic acid levels in tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neurons. Endocrinology. 1998, 139, 2857–62. [CrossRef]

- Chourpiliadi C, Paparodis R. Physiology, Pituitary Issues During Pregnancy. 2023. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–.

- Perez PA, Petiti JP, Picech F, Guido CB, dV Sosa L, Grondona E, Mukdsi JH, De Paul AL, Torres AI, Gutierrez S. Estrogen receptor β regulates the tumoral suppressor PTEN to modulate pituitary cell growth. J Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 1402–1413. [CrossRef]

- Lyons DJ, Broberger C. TIDAL WAVES: Network mechanisms in the neuroendocrine control of prolactin release. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014 Oct;35, 420-38. [CrossRef]

- Thörn Pérez C, Ferraris J, van Lunteren JA, Hellysaz A, Iglesias MJ, Broberger C. Adaptive Resetting of Tuberoinfundibular Dopamine (TIDA) Network Activity during Lactation in Mice. J Neurosci. 2020, 40, 3203–3216. [CrossRef]

- Lyons DJ, Ammari R, Hellysaz A, Broberger C. Serotonin and Antidepressant SSRIs Inhibit Rat Neuroendocrine Dopamine Neurons: Parallel Actions in the Lactotrophic Axis. J Neurosci. 2016, 36, 7392–406. [CrossRef]

- Bernard V, Lamothe S, Beau I, Guillou A, Martin A, Le Tissier P, Grattan D, Young J, Binart N. Autocrine actions of prolactin contribute to the regulation of lactotroph function in vivo. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 4791–4797. [CrossRef]

- Yatavelli RKR, Bhusal K. Prolactinoma. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459347. 4593.

- Lyu L, Yin S, Hu Y, Chen C, Jiang Y, Yu Y, Ma W, Wang Z, Jiang S, Zhou P. Hyperprolactinemia in clinical non-functional pituitary macroadenomas: A STROBE-compliant study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020, 99, e22673. [CrossRef]

- Bergsneider M, Mirsadraei L, Yong WH, Salamon N, Linetsky M, Wang MB, McArthur DL, Heaney AP. The pituitary stalk effect: is it a passing phenomenon? J Neurooncol. 2014, 117, 477–84. [CrossRef]

- Schury MP, Adigun R. Sheehan Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459166/. 4591.

- Montejo ÁL, Arango C, Bernardo M, Carrasco JL, Crespo-Facorro B, Cruz JJ, Del Pino-Montes J, García-Escudero MA, García-Rizo C, González-Pinto A, Hernández AI, Martín-Carrasco M, Mayoral-Cleries F, Mayoral-van Son J, Mories MT, Pachiarotti I, Pérez J, Ros S, Vieta E. Multidisciplinary consensus on the therapeutic recommendations for iatrogenic hyperprolactinemia secondary to antipsychotics. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2017, 45:25-34. [CrossRef]

- García Cano AM, Rosillo M, Gómez Lozano A, Jiménez Mendiguchía L, Marchán Pinedo M, Rodríguez Torres A, Araujo-Castro M. Pharmacological hyperprolactinemia: a retrospective analysis of 501 hyperprolactinemia cases in primary care setting. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2023 Nov 1. [CrossRef]

- Montejo ÁL, Arango C, Bernardo M, Carrasco JL, Crespo-Facorro B, Cruz JJ, Del Pino J, García Escudero MA, García Rizo C, González-Pinto A, Hernández AI, Martín Carrasco M, Mayoral Cleries F, Mayoral van Son J, Mories MT, Pachiarotti I, Ros S, Vieta E. Spanish consensus on the risks and detection of antipsychotic drug-related hyperprolactinaemia. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016, 9, 158–73 English, Spanish. [CrossRef]

- Wiciński M, Malinowski B, Puk O, Socha M, Słupski M. Methyldopa as an inductor of postpartum depression and maternal blues: A review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020, 127:110196. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura Y, Nakamura Y, Yamada H, Ando M, Ubukata Y, Oda T, Suzuki M. Possible contribution of prolactin in the process of ovulation and oocyte maturation. Horm Res. 1991, 35 Suppl 1:22-32. [CrossRef]

- Stocco, C. The long and short of the prolactin receptor: the corpus luteum needs them both!. Biol Reprod. 2012, 86, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezoe K, Fujiwara N, Miki T, Kato K. Post-warming culture of human vitrified blastocysts with prolactin improves trophoblast outgrowth. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2023, 21, 6. [CrossRef]

- Alila HW, Rogo KO, Gombe S. Effects of prolactin on steroidogenesis by human luteal cells in culture. Fertil Steril. 1987, 47, 947–55.

- Grattan DR, Jasoni CL, Liu X, Anderson GM, Herbison AE. Prolactin regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons to suppress luteinizing hormone secretion in mice. Endocrinology. 2007, 148, 4344–51. [CrossRef]

- Brown RS, Piet R, Herbison AE, Grattan DR. Differential actions of prolactin on electrical activity and intracellular signal transduction in hypothalamic neurons. Endocrinology. 2012, 153, 2375–84. [CrossRef]

- Cortasa SA, Schmidt AR, Proietto S, Corso MC, Inserra PIF, Giorgio NPD, Lux-Lantos V, Vitullo AD, Halperin J, Dorfman VB. Hypothalamic GnRH expression and pulsatility depends on a balance of prolactin receptors in the plains vizcacha, Lagostomus maximus. J Comp Neurol. 2023, 531, 720–742. [CrossRef]

- Xie Q, Kang Y, Zhang C, Xie Y, Wang C, Liu J, Yu C, Zhao H, Huang D. The Role of Kisspeptin in the Control of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis and Reproduction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13:925206. [CrossRef]

- Iwasa T, Matsuzaki T, Yano K, Mayila Y, Irahara M. The roles of kisspeptin and gonadotropin inhibitory hormone in stress-induced reproductive disorders. Endocr J. 2018, 65, 133–140. [CrossRef]

- Zeydabadi Nejad S, Ramezani Tehrani F, Zadeh-Vakili A. The Role of Kisspeptin in Female Reproduction. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2017, 15, e44337. [CrossRef]

- Franssen D, Tena-Sempere M. The kisspeptin receptor: A key G-protein-coupled receptor in the control of the reproductive axis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018, 32, 107–123. [CrossRef]

- d'Anglemont de Tassigny X, Colledge WH. The role of kisspeptin signaling in reproduction. Physiology (Bethesda). 2010, 25, 207–17, Erratum in: Physiology (Bethesda). 2010, 25, 378. [CrossRef]

- Goodman RL, Hileman SM, Nestor CC, Porter KL, Connors JM, Hardy SL, Millar RP, Cernea M, Coolen LM, Lehman MN. Kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin act in the arcuate nucleus to control activity of the GnRH pulse generator in ewes. Endocrinology. 2013, 154, 4259–69. [CrossRef]

- Moore AM, Coolen LM, Lehman MN. Kisspeptin/Neurokinin B/Dynorphin (KNDy) cells as integrators of diverse internal and external cues: evidence from viral-based monosynaptic tract-tracing in mice. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 14768. [CrossRef]

- Merkley CM, Porter KL, Coolen LM, Hileman SM, Billings HJ, Drews S, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. KNDy (kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin) neurons are activated during both pulsatile and surge secretion of LH in the ewe. Endocrinology. 2012, 153, 5406–14. [CrossRef]

- Mittelman-Smith MA, Krajewski-Hall SJ, McMullen NT, Rance NE. Neurokinin 3 Receptor-Expressing Neurons in the Median Preoptic Nucleus Modulate Heat-Dissipation Effectors in the Female Rat. Endocrinology. 2015, 156, 2552–62. [CrossRef]

- Duittoz A, Cayla X, Fleurot R, Lehnert J, Khadra A. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone and kisspeptin: It takes two to tango. J Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 33, e13037. [CrossRef]

- Constantin, S. Physiology of the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurone: studies from embryonic GnRH neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011, 23, 542–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d'Anglemont de Tassigny X, Fagg LA, Carlton MB, Colledge WH. Kisspeptin can stimulate gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) release by a direct action at GnRH nerve terminals. Endocrinology. 2008, 149, 3926–32. [CrossRef]

- Tng, EL. Kisspeptin signalling and its roles in humans. Singapore Med J. 2015, 56, 649–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Thresher RR, Acierno JS Jr, Shagoury JK, Bo-Abbas Y, Kuohung W, Schwinof KM, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Dixon J, Kaiser UB, Slaugenhaupt SA, Gusella JF, O'Rahilly S, Carlton MB, Crowley WF Jr, Aparicio SA, Colledge WH. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med. 2003, 349, 1614–27. [CrossRef]

- de Roux N, Genin E, Carel JC, Matsuda F, Chaussain JL, Milgrom E. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003, 100, 10972–6. [CrossRef]

- Funes S, Hedrick JA, Vassileva G, Markowitz L, Abbondanzo S, Golovko A, Yang S, Monsma FJ, Gustafson EL.. The KiSS-1 receptor GPR54 is essential for the development of the murine reproductive system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003, 312, 1357–63. [CrossRef]

- Teles MG, Bianco SD, Brito VN, Trarbach EB, Kuohung W, Xu S, Seminara SB, Mendonca BB, Kaiser UB, Latronico AC. A GPR54-activating mutation in a patient with central precocious puberty. N Engl J Med. 2008, 358, 709–15. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser M, Jaillardon L. Pathogenesis of the crosstalk between reproductive function and stress in animals-part 1: Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis, sympatho-adrenomedullary system and kisspeptin. Reprod Domest Anim. 2023, 58 Suppl 2:176-183. [CrossRef]

- Brown RS, Herbison AE, Grattan DR. Prolactin regulation of kisspeptin neurones in the mouse brain and its role in the lactation-induced suppression of kisspeptin expression. J Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 26, 898–908. [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Lopes R, Crampton JR, Aquino NS, Miranda RM, Kokay IC, Reis AM, Franci CR, Grattan DR, Szawka RE. Prolactin regulates kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus to suppress LH secretion in female rats. Endocrinology. 2014, 155, 1010–20. [CrossRef]

- Kokay IC, Petersen SL, Grattan DR. Identification of prolactin-sensitive GABA and kisspeptin neurons in regions of the rat hypothalamus involved in the control of fertility. Endocrinology. 2011, 152, 526–35. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Rao A, Pereira A, Clarke IJ, Smith JT. Kisspeptin cells in the ovine arcuate nucleus express prolactin receptor but not melatonin receptor. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011, 23, 871–82. [CrossRef]

- Gustafson P, Ladyman SR, McFadden S, Larsen C, Khant Aung Z, Brown RSE, Bunn SJ, Grattan DR. Prolactin receptor-mediated activation of pSTAT5 in the pregnant mouse brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2020, 32, e12901. [CrossRef]

- Calik-Ksepka A, Stradczuk M, Czarnecka K, Grymowicz M, Smolarczyk R. Lactational Amenorrhea: Neuroendocrine Pathways Controlling Fertility and Bone Turnover. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 1633. [CrossRef]

- Grattan DR, Szawka RE. Kisspeptin and Prolactin. Semin Reprod Med. 2019, 37, 93–104. [CrossRef]

- Hara T, Kanasaki H, Tumurbaatar T, Oride A, Okada H, Kyo S. Role of kisspeptin and Kiss1R in the regulation of prolactin gene expression in rat somatolactotroph GH3 cells. Endocrine. 2019, 63, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Ammari R, Broberger C. Pre- and post-synaptic modulation by GABAB receptors of rat neuroendocrine dopamine neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2020, 32, e12881. [CrossRef]

- Aquino NSS, Kokay IC, Perez CT, Ladyman SR, Henriques PC, Silva JF, Broberger C, Grattan DR, Szawka RE. Kisspeptin Stimulation of Prolactin Secretion Requires Kiss1 Receptor but Not in Tuberoinfundibular Dopaminergic Neurons. Endocrinology. 2019, 160, 522–533. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro AB, Leite CM, Kalil B, Franci CR, Anselmo-Franci JA, Szawka RE. Kisspeptin regulates tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neurones and prolactin secretion in an oestradiol-dependent manner in male and female rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2015, 27, 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Sonigo C, Bouilly J, Carré N, Tolle V, Caraty A, Tello J, Simony-Conesa FJ, Millar R, Young J, Binart N. Hyperprolactinemia-induced ovarian acyclicity is reversed by kisspeptin administration. J Clin Invest. 2012, 122, 3791–5. [CrossRef]

- Uenoyama Y, Pheng V, Tsukamura H, Maeda KI. The roles of kisspeptin revisited: inside and outside the hypothalamus. J Reprod Dev. 2016, 62, 537–545. [CrossRef]

- Yang F, Zhao S, Wang P, Xiang W. Hypothalamic neuroendocrine integration of reproduction and metabolism in mammals. J Endocrinol. 2023, 258, e230079. [CrossRef]

- Lee MS, Ben-Rafael Z, Meloni F, Mastroianni L Jr, Flickinger GL.. Relationship of human oocyte maturity, fertilization, and cleavage to follicular fluid prolactin and steroids. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1987, 4, 168–72. [CrossRef]

- Reinthaller A, Deutinger J, Riss P, Müller-Tyl E, Fischl F, Bieglmayer C, Janisch H. Relationship between the steroid and prolactin concentration in follicular fluid and the maturation and fertilization of human oocytes. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1987, 4, 228–31. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian MG, Sacco AG, Moghissi KS, Magyar DM, Hayes MF, Lawson DM, Gala RR. Human follicular fluid: prolactin is biologically active and ovum fertilization correlates with estradiol concentration. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1988, 5, 129–33. [CrossRef]

- Lindner C, Lichtenberg V, Westhof G, Braendle W, Bettendorf G. Endocrine parameters of human follicular fluid and fertilization capacity of oocytes. Horm Metab Res. 1988, 20, 243–6. [CrossRef]

- Laufer N, Botero-Ruiz W, DeCherney AH, Haseltine F, Polan ML, Behrman HR. Gonadotropin and prolactin levels in follicular fluid of human ova successfully fertilized in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984, 58, 430–4. [CrossRef]

- Wyse BA, Fuchs Weizman N, Defer M, Montbriand J, Szaraz P, Librach C. The follicular fluid adipocytokine milieu could serve as a prediction tool for fertility treatment outcomes. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021, 43, 738–746. [CrossRef]

- Romão GS, Ferriani RA, Moura MD, Martins AR. Screening for prolactin isoforms in the follicular fluid of patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2002, 54, 46–9. [CrossRef]

- Castilla A, García C, Cruz-Soto M, Martínez de la Escalera G, Thebault S, Clapp C. Prolactin in ovarian follicular fluid stimulates endothelial cell proliferation. J Vasc Res. 2010, 47, 45–53. [CrossRef]

- Amin M, Gragnoli C. The prolactin receptor gene (PRLR) is linked and associated with the risk of polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 222. [CrossRef]

- Alkharusi A, AlMuslahi A, AlBalushi N, AlAjmi R, AlRawahi S, AlFarqani A, Norstedt G, Zadjali F. Connections between prolactin and ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0255701. [CrossRef]

- Cho A, Vila G, Marik W, Klotz S, Wolfsberger S, Micko A. Diagnostic criteria of small sellar lesions with hyperprolactinemia: Prolactinoma or else. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13: 901385. [CrossRef]

- Cheng JS, Salinas R, Molinaro A, Chang EF, Kunwar S, Blevins L, Aghi MK. A predictive algorithm for evaluating elevated serum prolactin in patients with a sellar mass. J Clin Neurosci. 2015, 22, 155–60. [CrossRef]

- Petersenn S, Fleseriu M, Casanueva FF, Giustina A, Biermasz N, Biller BMK, Bronstein M, Chanson P, Fukuoka H, Gadelha M, Greenman Y, Gurnell M, Ho KKY, Honegger J, Ioachimescu AG, Kaiser UB, Karavitaki N, Katznelson L, Lodish M, Maiter D, Marcus HJ, McCormack A, Molitch M, Muir CA, Neggers S, Pereira AM, Pivonello R, Post K, Raverot G, Salvatori R, Samson SL, Shimon I, Spencer-Segal J, Vila G, Wass J, Melmed S. Diagnosis and management of prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas: a Pituitary Society international Consensus Statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 722–740, Erratum in: Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023 Oct 17. [CrossRef]

- Chanson P, Borson-Chazot F, Chabre O, Estour B. Drug treatment of hyperprolactinemia. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2007, 68(2-3):113-7. [CrossRef]

- Concepción-Zavaleta MJ, Coronado-Arroyo JC, Quiroz-Aldave JE, Durand-Vásquez MDC, Ildefonso-Najarro SP, Rafael-Robles LDP, Concepción-Urteaga LA, Gamarra-Osorio ER, Suárez-Rojas J, Paz-Ibarra J. Endocrine factors associated with infertility in women: an updated review. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2023, 18, 399–417. [CrossRef]

- Hoskova K, Kayton Bryant N, Chen ME, Nachtigall LB, Lippincott MF, Balasubramanian R, Seminara SB. Kisspeptin Overcomes GnRH Neuronal Suppression Secondary to Hyperprolactinemia in Humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022, 107, e3515–e3525, Erratum in: J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 May 18. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Tazangi F, Kooshesh L, Tayyebiazar A, Taghizabet N, Tavakoli A, Hassanpour A, Aliakbari F, Kharazinejad E, Sharifi AM. Effects of kisspeptin on the maturation of human ovarian primordial follicles in vitro. Zygote. 2023:1-5. [CrossRef]

- Chutpiboonwat P, Yenpinyosuk K, Sridama V, Kunjan S, Klaimukh K, Snabboon T. Macroprolactinemia in patients with hyperprolactinemia: an experience from a single tertiary center. Pan Afr Med J. 2020, 36:8. [CrossRef]

- Richa V, Rahul G, Sarika A. Macroprolactin; a frequent cause of misdiagnosed hyperprolactinemia in clinical practice. J Reprod Infertil. 2010, 11, 161–7.

- Che Soh NAA, Yaacob NM, Omar J, Mohammed Jelani A, Shafii N, Tuan Ismail TS, Wan Azman WN, Ghazali AK. Global Prevalence of Macroprolactinemia among Patients with Hyperprolactinemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 8199. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Wang H, Yang W, Jin W, Yu W, Wang W, Zhang K, Song G. A New Method of Using Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Precipitation of Macroprolactin to Detect Genuine Hyperprolactinemia. J Clin Lab Anal. 2016, 30, 1169–1174. [CrossRef]

- Shimatsu A, Hattori N. Macroprolactinemia: diagnostic, clinical, and pathogenic significance. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012, 2012:167132. [CrossRef]

| CLASS/STAGE OF THE FOLLICLE | EXPRESSION OF SELECTED GENES | ||

| Granulosa cells | Oocyte | Theca cells | |

| Primordial | 3βHSD, ALK3, BMPRII, Erβ, KITLG, StAR, WTI | ALK3, ALK6, BMP6, BMPRII, C-kit, Erβ, GDF9, GJA4, TGFBR3 | – |

| Primary | βB-activin, ActRIIB, ALK6, AMH, AMHRII, FSH-R, GJA1, IGFR1 | BMP15, FIGα | – |

| Small preantral | ALK5, FSRP, FST, TGFBR3 | – | ActRIIB, ALK3, ALK5, ALK6?, BMPRII, FSRP, IGFR1, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGFBR3, TGFBR11 |

| Large preantral | AR, ERα, InhA | – | 3βHSD, ARErβ, CYP17A1, IGF2, LHR, PR, SF1, StAR |

| HORMONE | SOURCE | TYPICAL STRUCTURE or CHEMICAL FORMULA | GENERAL DESCRIPTION | LEVEL CHANGES DURING THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE AND OVULATION | CONCENTRATION RANGE (blood; women of reproductive age) * |

| Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) | Neurons of hypothalamus |

GnRH is a decapeptide with the presence of the amino terminal pyroglutamic acid (pE, a cyclic non-proteinogenic amino acid, containing a γ-lactam ring, that is produced from glutamine or glutamic acid by deamidation or dehydration, respectively) and the amidated carboxy terminus. In all three forms of GnRH (GnRH1, GnRH2, GnRH3), both N-terminal and C-terminal are conserved, which allows for effective binding to their receptors [114,155,156]. |

The master hormone that regulates reproductive activity by stimulating the release of gonadotropins and, consequently, stimulating the production of sex hormones in the gonads. This hormone ultimately regulates puberty onset, sexual development, and ovulatory cycles in females [114,115]. | Frequency and amplitude of hypothalamic GnRH pulses determine the relative proportions of pituitary secretion of FSH and LH. In the normal menstrual cycle, GnRH pulse frequency increases from about 90-100 minutes to about every 60 minutes through a follicular phase. Gradual increase in GnRH pulse frequency facilitates LH secretion culminating in an ovulatory LH surge [115,157]. Earlier, a switch from estradiol negative to positive feedback initiates the GnRH influx, affecting LH release. In contrast, increased progesterone secretion in a luteal phase results in an increase in FSH synthesis as a result of less frequent hypothalamic GnRH secretion (approximately one pulse every 3–5 hours), through mechanisms involving opioid receptors [158,159,160,161] and possibly other factors such as kisspeptin [162]. | Approx., 0.1 – 2.0 pg/ml; the basal levels of GnRH do not change significantly before, during and after the LH surges, and show fluctuations (pulsations) between a small range of 0.1 and 2.0 pg/ml [163]. |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) | Anterior pituitary |