1. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution has leveraged advanced information systems, including artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things, as general-purpose technologies to drive innovation across industries. This integration with various business models has enabled the fulfillment of entirely new demands. Furthermore, the exponential pace of technological development is expected to catalyze unprecedented innovation, granting access to infinite knowledge and information through hyperconnectivity, hyperconvergence, and hyperintelligence. These advancements are expected to induce structural transformations in production, management, and governance on a global scale [

1].

In this context, while technology serves as a catalyst for the economic structural innovations of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, there will inevitably be limitations to relying solely on technology to generate positive structural shocks and new value. To extract high levels of added value from new technologies, comprehensive support in the areas of design, implementation, and operation is indispensable. Within the service industry, knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS) fulfill this role. Professional services contribute to the creation, accumulation, and dissemination of new knowledge, thereby fostering the generation of freshly added value. As entities have engaged in business activities related to emerging technology, KIBS not only act as users of new technology but also serve as producers driving technological innovation and innovators [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

KIBS are an industry positioned to act as a complementary asset essential for the key technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and to generate value and transform the economic system appropriately. While the definition of KIBS may vary among scholars and institutions, Miles et al. (1995) identified three primary characteristics that align with the consensus of most experts: 1) heavy reliance on expert knowledge, 2) serving as the main source of information and knowledge or utilizing knowledge to provide intermediate services necessary for the customer’s production process, and 3) primarily supplying businesses with a competitive advantage[

2]. KIBS entities play a central role in fostering innovation as knowledge operators, producers, and mediators within national and regional economies [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Moreover, they possess characteristics such as a heightened awareness of knowledge activities, the ability to interpret and resolve various problems, and the ability to provide services. Catalyzing constant systemic change, KIBS, particularly professional producers and users in the knowledge-intensive service industry, have led to transformations within complex innovation systems [

5].

Research on KIBS is primarily centered on industries driven by companies seeking KIBS support [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. This research spans the regional and national levels [

19,

20,

21] and has been conducted over several years, examining various types of innovations. The results of these studies consistently underscore the role of KIBS in supporting innovation within target units [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Specifically, the findings reveal variations based on factors such as the degree of connectivity and concentration of KIBS, skill level of the labor force, and age and size of entities utilizing the KIBS within a given region.

As KIBS are a knowledge-intensive industry, there are limitations when analyzing results obtained within a short period; therefore, research has been conducted in regions with mature industries over a long period. However, as national economies become globalized and knowledge transfer methods diversify, interest in KIBS is growing even in developing countries, and research is being conducted on regions and industries in various countries. In addition, because the size and characteristics of the economy vary in each region and country, how KIBS operate may also differ [

5]. Therefore, although KIBS research has been conducted for a long time, it is meaningful to measure the role and degree of influence of KIBS depending on the country and period.

Since we are currently in the midst of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, when advanced information technology is leading innovation in the economic system, it is important to discuss how to utilize it by examining the influence and role of KIBS in each country.

Therefore, this study investigates the impact of Knowledge-Intensive Business Services (KIBS) on the Korean economy. The focus is on analyzing and contrasting the level of influence and contribution of the overall KIBS sector, T-KIBS (new technology-based professional services), P-KIBS (traditional professional services), and their respective subsectors within the Korean economy.

For this analysis, information on how much the KIBS sector invests in other industries and how output occurs in other industries must be considered. Therefore, this study applied the demand-inducement model, supply inducement model, and interlinkage effects method to an industry linkage table. Through this analysis, one can see how all the sectors covered by the KIBS sector play a role in the Korean economy and how much influence they have.

2. Literature Review

2.1. KIBS and Classificaiton

KIBS are an industry that largely falls under the category of KS (knowledge services). A “knowledge service” is defined as a high value-added industry that requires creativity and expertise by intensively utilizing intangible assets embedded with knowledge and is a core sector of the service industry. KIBS are defined in the Eurofound (2006) as a group of service activities that affect the quality and efficiency of production by supplying intermediate goods to other companies or organizations to complement or replace the internal service functions of a company or organization [

28].

The role of the KIBS has been considered important in academia since the mid-1990s, and many scholars have conducted research on KIBS and attempted to define it [2-4.,9, 29]. Miles (1995) defined “knowledge-intensive services” as services related to economic activities aimed at creating knowledge-intensive services and presents the following three main operating principles: 1. They rely heavily on expert knowledge. 2. They are either primary resources of information and knowledge in their own rights or use this knowledge to produce intermediate services for their customers’ production processes. 3. They are competitively significant and primarily supply businesses [

2]. Bettencourt et al. (2002) defined knowledge-intensive firms as enterprises engaged in the primary value-adding activity of accumulating, generating, or disseminating knowledge to develop tailored services or product solutions that meet customer demands [

29]. Conversely, Hertog (2000) described them as private companies or organizations heavily relying on specialized knowledge associated with specific fields or functional domains to supply intermediate products or services related to a particular sector [

3]. Muller and Doloreux, (2009) noted that several scholars have proposed three key elements

––“business service,” “knowledge-intensive,” and “knowledge-intensive firms”––through their definitions of KIBS [

4].

Depending on their roles and characteristics, KIBS entities are divided into traditional professional services, P-KIBS, and new technology-based services, or T-KIBS. They are largely classified into two subcategories: P-KIBS and T-KIBS. A P-KIBS entity is a traditional professional service that uses new technologies intensively and includes business, management, law, and accounting services. This includes services related to T-KIBS’ information and communication technology [

2]. In addition, such a KIBS classification inevitably has limitations when distinguishing between detailed classifications depending on the characteristics of the data used; however, several scholars have broadly categorized them into information and communication activities (J), and professional, scientific, and technical (M), based on the European NACE Rev.2, as shown in the

Table 1. Activities (M) are divided into two sections and seven subdivisions. Among these, the divisions corresponding to P_KIBS are division 69, legal, law and accounting, and consulting activities; division 70, head office activities and management consultancy activities; and division 73, advertising and market research. The other four divisions are included in T-KIBS [

30].

2.2. Relationship between KIBS and Innovation

KIBS play a role in supporting innovation rather than the service itself by contributing to knowledge diffusion through knowledge input and output between economic units [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Various studies related to the important role of KIBS have been conducted across organizations, industries, regions, and countries.

Company-level research has been conducted on how KIBS can support innovation in specific industries, and many of these studies have been conducted in the manufacturing sector [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In addition, studies have been conducted to determine whether these studies would produce the same results in specific countries or regions and show how the KIBS sector works in each region [

15,

19,

20]. Furthermore, many studies have shown that the KIBS sector serves as a resource for innovation in other service fields [

18].

Another mainstay of KIBS research is its use as a regional innovation tool. This is because KIBS provide highly skilled knowledge services; therefore, the degree of KIBS utilization may vary depending on the skill of the supply of labor resources and the sophistication of services in regional and national economies [

5]. Accordingly, many studies have been conducted on the role of KIBS in specific regions or countries, but most have been carried out in Europe and North America, which led the industrial revolution [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. With the recent economic growth in Asia, countries such as China and Singapore are paying attention to KIBS, and research on them is also underway in the region [

37,

38,

39,

40].

Research has focused on the impact of KIBS on innovation and economic growth in subunits of economic systems, such as

industries [

5,

16,

17], regions [

41], and countries, based on the scope of KIBS support or demand. These studies have often focused on specific outcomes, including internationalization and export orientation and examined the implications of the KIBS sector on various facets of economic systems [

15,

42]. While these studies vary in their emphasis on different aspects of KIBS support and target demand, they consistently conclude that KIBS play a supportive role in innovation and economic growth. Differences in the extent of innovation are attributed to factors such as the size and age of businesses [

15,

42,

43], maturity of the workforce, and concentration of intellectual resources [

41]. Overall, these studies highlight the multifaceted contributions of KIBS to fostering innovation and economic development.

2.3. KIBS Industry Status in Korean economy

Table 2 and

Table 3 reconstruct the share and growth rate of KIBS in the Korean economy from 2010 to 2019 using the 2019 industry correlation table announced by the Bank of Korea in 2022. KIBS can be classified as P-KIBS or T-KIBS. One is presented in

Section 2.1. Therefore, in this study, P-KIBS correspond to M (711) legal and management support services and M (712) advertising, and T-KIBS correspond to J (610) information services, J (621) software development supply, J (including 629) other IT services, M (700) R&D, M (721) architectural and civil engineering services, and M (729) other scientific, technical, and professional services. The KIBS classification is based on this standard in future industry-linkage analyses.

Table 2 shows the proportion of KIBS’ total output. In 2010, the total output of KIBS in the Korean economy was 4.2%; however, in 2019, it grew significantly to 7.2%, showing an average annual growth rate of 9.6%. These figures show steep growth compared to the total output of the entire Korean economy, which demonstrated an average annual growth rate of 3.4%. The share of T-KIBS in the Korean economy was 3.5% in 2010 and 5.1% in 2019, with an average annual growth rate of 7.8%. For the P-KIBS sector, the rate was only 0.8% in 2010 and 2.1% in 2019, with an annual average of 15.6%. In particular, legal and management support services, a subcategory of P-KIBS, accounted for only 0.5% of the entire Korean economy in 2010 but grew to 1.8% in 2019, with an average annual growth rate of 19.5%. Among the T-KIBS subcategories, the sector that grew most rapidly was software development supply, with an average annual growth rate of 9.7%, whereas R&D showed an 8.8% growth rate.

Table 3 shows the added value of KIBS and their share in the Korean economy. The value-added share of all the KIBS sectors in the Korean economy was 6.2% in 2010 and 9.1% in 2019, with an average annual growth rate of 9.3%. It is evident that these figures are higher than the average annual growth rate of 4.8% in terms of Korea’s added value. In addition, it was higher than the total output share of 7.2% in 2019. However, the average annual growth rate was 9.3%, which was slightly lower than the average annual growth rate of the total output of 9.6%.

Considering the KIBS subcategories, the value-added proportion of T-KIBS increased from 5.2% in 2010 to 7.6% in 2019, the average annual growth rate was 9.4%, and that of P-KIBS increased from 1.0% in 2010 to 1.4% in 2019. The annual average rate was 8.7%, indicating a higher proportion and growth rate for T-KIBS than for P-KIBS. Among the detailed classifications of the KIBS sectors, the industries with the highest added value as of 2019 were R&D, corresponding to T-KIBS at 3.0%, and software development supply at 2.1%, with average annual growth rates of 9.6% and 12.1%, respectively.

3. Data and Methodologies

This study is an analysis and comparison of the degree of influence and role of the entire KIBS sector, T-KIBS (a new technology-based professional service), P-KIBS (a traditional professional service), and sub-sectors on the Korean economy. For this purpose, among the input-output analysis methodologies, an analysis was conducted on the industry linkage effect, which involved an examination of the forward and backward effects of each research target industry, the production inducement effect of the demand inducement model, the value-added inducement effect, and the supply shortage effect of the supply inducement model. In addition, an exogenous specification method is used to distinguish between the indirect ripple effect of the industry under analysis in other industries and the direct ripple effect of the subject of analysis [

44].

3.1. Input-Output Table

The input–output table is a comprehensive statistical table that records the inter-industry trade relationships of goods and services produced in a country over a period of time [

45]. Input-output analysis using this method is advantageous for analyzing the economic structure based on inter-industry relationships [

46]. In addition, input-output analysis shows how changes in the level of production in one sector generate continuous demand for the products of other sectors; this is a general equilibrium model that emphasizes the link between sales and purchases of inputs. Owing to its nature, it is a useful method for analyzing and predicting the overall economic impact [

46].

Therefore, this study involved an industry linkage analysis using the 2019 industry linkage table published by the Bank of Korea in 2022 to examine the influence relationships and roles of KIBS sectors on the Korean economy.

3.2. Input-Output Analysis

3.2.1. Demand Inducement Model

This study is based on an examination of the production inducement and value-added inducement effects among detailed demand inducement models. Here, production-inducement effects and value-added inducement effects refer to the direct and indirect production inducement and value-added inducement amount on the same industry and other industries when 1 KRW is produced or invested in the industry being analyzed. To calculate this effect, equations (1)–(4) were used.

The input coefficient (α_ij) in equation (1) is the intermediate input amount (X_ij) of raw materials purchased by each industrial sector from other industrial sectors for the production of the goods and services of that industrial sector divided by the total input amount (X_i). If this is expressed in the same array form as the endogenous part of the input–output table, it becomes the input coefficient table (A). To calculate the ripple effect of each analysis target, the input coefficient (α_ij) is calculated using the input-output table that reclassifies each industry subject to analysis from the input-output table. The equation (1) is as below.

- Xi: Input amount in subsector i

- Xij: Input amount in subsector j by intermediate input xi

The production inducement coefficient converts the industry subject to analysis into an exogenous variable and then uses basic equation (2).

- : Row vector of the input coefficients of the reclassified industries subject to analysis

- : Diagonal matrix of 1 (diagonal matrix)

- : Input coefficient() matrix

The value-added coefficient in equation (3) is the sum of the added value of each industrial sector in the input-output table divided by the total output.

: Added value of subsector

The value-added coefficient in equation (4) measures the part of the production inducement effect that is attributable to added value through the value-added coefficient and is calculated by multiplying the value-added coefficient by the production inducement coefficient. This is the net national economic value obtained from the industry being analyzed.

- : Diagonal vector of the value-added coefficient

- : Production inducement coefficient

3.2.2. Supply Inducement Model

The supply shortage effect is one of the supply inducement model methods, and it indicates how much production will be reduced in other industries when the production of the industry being analyzed is not achieved by 1 won.

To calculate these supply shortage effects, the output coefficient (R_ij) in equation (6) is first created using the output coefficient table. This is the number of intermediate inputs, such as raw materials purchased from other sectors for the production of goods and services, divided by the total output.

- : Output of subsector i

- : Output amount in subsector by intermediate input

The supply shortage coefficient is calculated by exogenizing the industry subject to analysis and using the following basic model equation (6).

- : Output coefficient horizontal vector of the subsector

- : One diagonal matrix with a diagonal vector 1

-: Output coefficient matrix ()

3.2.3. Industry Linkage Effect

The industry linkage effect consists of backward linkage effects (

) and forward linkage effects (FLi). Here, the forward linkage effect (FLi) in equation (8) is the sum of the rows of the production inducement coefficient (α_ij) matrix divided by the entire industry average for the sum of the rows of the production inducement coefficient matrix, which represents all final demand in all sectors as one unit. It indicates the ratio of the units that the

th industry must produce in order to increase the unit to the average value of all industries.

The backward linkage effect (

) in equation (9) is the value obtained by dividing the row sum of the production inducement coefficient matrix by the overall industry average of the row sum of the production inducement coefficient matrix, which is the industry-specific inducement coefficient for the average production inducement coefficient (α_ij) of all industries.

3.3. Research Procedure and Reclassification of KIBS

This study investigates the role of KIBS as a tool for economic system innovation. Utilizing Using input-output tables for input-output analysis, the research applied the demand-inducement model, supply-inducement model, and interlinkage effects to examine various economic ripple effects. The objective was to understand the role of the KIBS sector in an economic system and quantify its economic ripple effects, thereby discerning how the KIBS sector functions as a tool for economic system innovation.

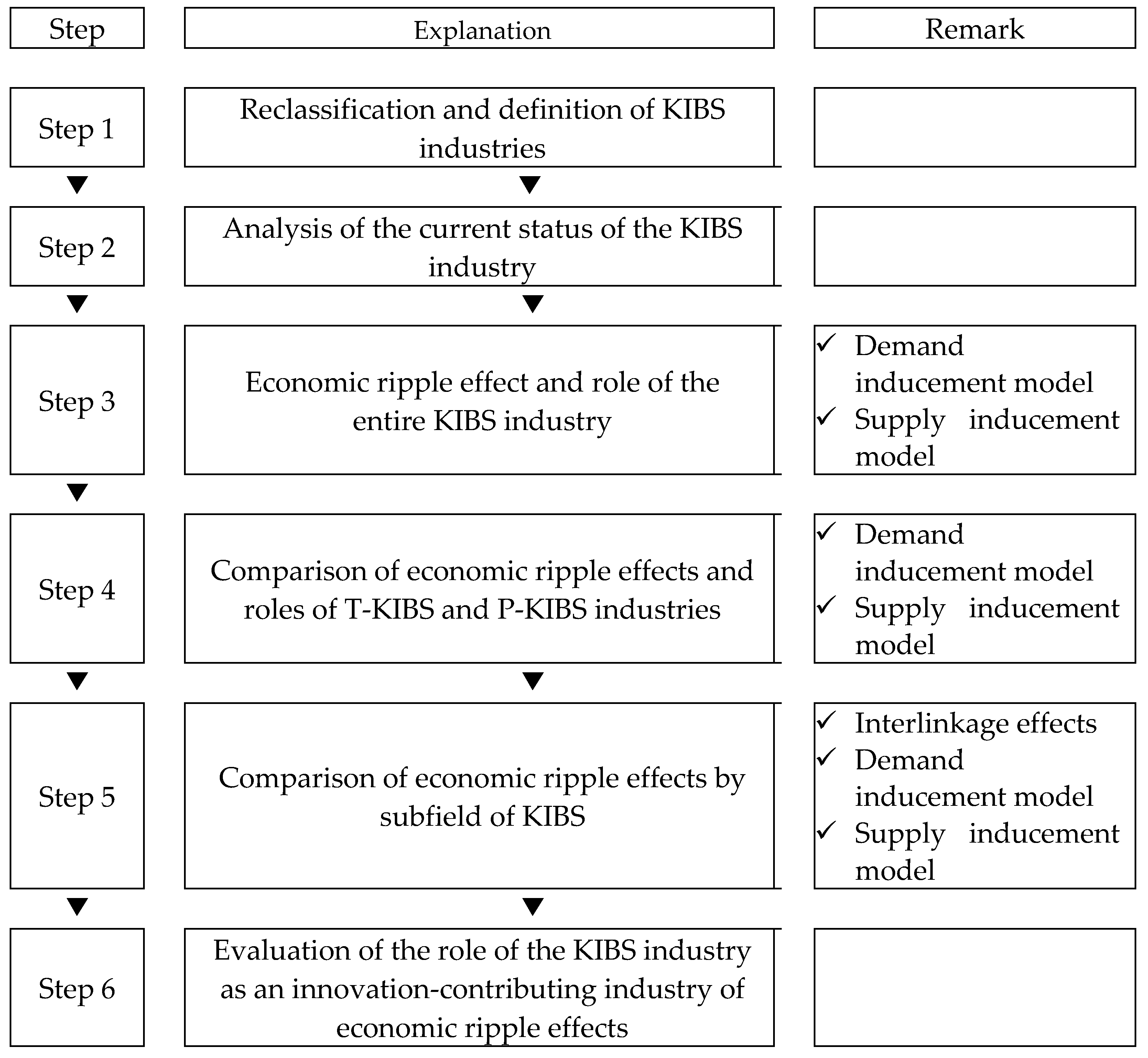

To differentiate this research and provide specificity for the role of KIBS, I distinguished KIBS from T-KIBS and P-KIBS. I examined the economic ripple effects and roles of each industry in these classifications. The specific research procedure is detailed in

Figure 1, with the goal of delineating the distinctive roles and economic impacts of T-KIBS and P-KIBS.

The steps of this study are illustrated in

Figure 1. Step 1 is a necessary preliminary step in examining the role of the KIBS sector in the Korean economic system. To this end, based on previous literature, KIBS are classified in detail according to their characteristics, and the industry is reclassified in a form that can be analyzed. Currently, KIBS entities are divided into the entire KIBS industry, technology-based KIBS, and P-KIBS, which are classified as traditional professional services. In addition, each detailed KIBS subindustry is classified for analysis.

Step 2 presents the analysis of the status of the KIBS industry. The second step examines the share of the KIBS industry and the value-added output in the KIBS industry, the KIBS industry classifications, and the detailed classifications.

Steps 3–4 examine the impact of KIBS on the overall Korean economic system and the differences in the economic ripple effects of T-KIBS and P-KIBS on the Korean economic system. For this purpose, I analyzed the supply shortage effects, which are the production inducement, value-added inducement, and supply shortage effects of the demand inducement model. Through the results, I can specifically identify which industries the KIBS sector influences in the Korean economic system.

Step 5 analyzes the demand inducement, supply inducement, and interlinkage effects for each sector to examine the roles and ripple effects of each KIBS subcategory in the Korean economic system. I also compared the KIBS, T-KIBS, and P-KIBS results analyzed previously.

Finally Step 6 uses the literature review and analysis presented above to evaluate the role of KIBS as a tool for innovation in the Korean economic system.

Table 4 presents the industrial classifications used in this study. First, for industrial linkage analysis, the KIBS sector, the industry subject to analysis, is reclassified and redefined as a single industry. In addition, to understand the impact of the industry being analyzed on other industries, each industry is presented based on the Bank of Korea Input-Output Table of Industrial Representative Classifications.

Looking at the KIBS reclassification, eight industries fall into this category based on the Bank of Korea’s industrial classifications’ subclassifications. Among these, six industries fall under T-KIBS: J (610) information services, J (621) software development supply, J (629) other IT services, M (700) R&D, and M (721) architecture, which includes civil engineering services, and M (729) other science, technology, and professional services. In addition, P-KIBS include two industries: M (711) legal and management support services and M (721) advertisement.

4. Empirical Evaluation and Results

This section presents the results of Steps 3–5 of the analytical process. The data used in the analysis were analyzed using the 2019 industry correlation table published by the Bank of Korea in 2022.

First, in

Section 4.1, I treat the eight sectors of the KIBS industry as a single industry and examine their overall impact on the South Korean economy. Following that, in

Section 4.2 and

Section 4.3, I delve into the individual impacts of T-KIBS and P-KIBS on the entire South Korean economy, as well as the mutual influence between the two types of KIBS. Finally, to understand the roles of specific sectors within the KIBS sector and their impact on the South Korean economy, the economic ripple effects of each sector are compared.

4.1. Results of the Economic Ripple Effect of the KIBS Industry

Table 5 examines the ripple effects of the KIBS sector on the Korean economy through the demand inducement model, production inducement effects, value-added inducement effects, and the supply inducement model’s supply shortage effects.

First, production inducement effects indicate how much production is induced in other industries when 1 won of final demand is generated in the sector being analyzed (or can be interpreted as investment). The KIBS sector showed that when the final demand of an industry was 1 KRW, the production inducement from other industries was 0.8 KRW. At this time, the production inducement effects of the industry were 1.195 KRW, showing a total of 1.995 KRW of production inducement effects.

Looking at the sectors in which KIBS have the largest indirect ripple effect on other industries, C09 computers, electronics, and optics, had the highest at 0.075 KRW, followed by C05 chemicals, at 0.063 KRW; N business services, at 0.058 KRW; J broadcasting and newspaper and publishing showed an effect of 0.055 KRW. Conversely, the sectors with the lowest scores were P education services (0.001 KRW), O public administration, defense, and social security (0.001 KRW), and others (0.002 KRW). The indirect effect of production inducement on the primary industry was 0.053 KRW for accounting, for a rate of 6.6%; the secondary industry effect, corresponding to the manufacturing industry, was 0.341 KRW, accounting for 42.6%; and the tertiary industry effect, corresponding to the service industry, was 0.406 KRW, accounting for 50.8%.

Value-added inducement effects indicate how much added value is induced in other industries when 1 won of final demand is generated in the sector being analyzed (or can be interpreted as investment). The indirect effect of the KIBS sector on inducing added value in other industries was found to be 0.330 KRW, and the added value induced by the industry itself was 0.551 KRW, for a total of 0.881 KRW. The sector that generated the most added value due to KIBS was N business services with 0.039 KRW, followed by C09 computers, electronics, and optics with 0.030 KRW, and L real estate services with 0.027. Conversely, the least affected sector was T others, with a value close to 0, P education services with 0.001 KRW, and O public administration, defense, and social security, with 0.001 KRW. KIBS’ indirect value-added inducement effects were 0.026 KRW or 7.8% for the primary industry, 0.106 KRW or 32.0% for the secondary industry, and 0.198 KRW or 60.2% for the tertiary industry. Value-added inducement effects were found to have a greater impact on the tertiary industry than production inducement effects.

The following supply shortage effects can be used to determine how much production fails to occur in other industries when the industry being analyzed does not produce 1 won; that is, when 1 won is not supplied. The supply shortage effects of the KIBS sector on other industries totaled 1.144 KRW. The most affected sector was C05 chemicals at 0.113 KRW, followed by construction at 0.107 KRW, G wholesale and retail trade services at 0.086 KRW, and C12 transportation equipment at 0.084 KRW. In contrast, the sectors least affected by KIBS were T others at 0.001 KRW, minerals (0.001 KRW), and E water, waste disposal, and recycling services (0.006 KRW). Supply shortage effects were found to affect the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries by 1.2%, 50.7%, and 48.0%, respectively. Compared to the production and value-added inducement effects analyzed previously, the supply shortage effects on the primary industry were found to be low. However, the impacts on secondary and tertiary industries appeared even.

4.2. Results of the Economic Ripple Effect of T-KIBS Industry

This section is an examination of the ripple effects of T-KIBS on South Korea’s economy (

Table 6). Through this analysis, the impact of T-KIBS and their influence on P-KIBS were investigated. First, looking at production inducement effects, the impact of T-KIBS on other industries was found to be 0.687 KRW, and the effect on its own industry was 1.084 KRW, for a total of 1.771 KRW. The sector most affected by T-KIBS was C09 computers, electronics, and optics at 0.085 KRW, followed by C05 chemicals at 0.053 KRW, P-KIBS at 0.047 KRW, and transportation services at 0.042 KRW. However, the least affected sectors were P education services at 0.001 KRW, O public administration, defense, and social security at 0.001 KRW, and T others at 0.002 KRW. In addition, the primary industry’s rate was 5.7% with a KRW value of 0.039, for secondary industry, the rate was 45.7% with a KRW value of 0.314, and for tertiary industry, the rate was 48.7%.

The value-added inducement effect of T-KIBS on other industries was 0.272 KRW, the direct effect was KRW 0.654, and the total value-added inducement effect was 0.926 KRW. The sector most affected by T-KIBS was production inducement effects, with C09 computers, electronics, and optics at 0.034 KRW, followed by N business services at 0.028 KRW, G wholesale and retail trade services at 0.021 KRW, and L real estate services at 0.017 KRW. The value-added inducement effect on P-KIBS was 0.014 KRW, showing the seventh largest impact among the 33 industries. In contrast, the least affected sector was T others, which was close to 0, followed by P education services at 0.001 KRW, O public administration, defense, and social security at 0.001 KRW, and C13 other manufacturing products at 0.001 KRW. The primary industry represented 0.019 KRW (6.9%), the secondary industry was 0.099 KRW (36.4%), and the tertiary industry was 0.154 KRW (56.7%), respectively.

In the case of supply shortage effects, the effect of T-KIBS on other industries was 0.730 KRW, of which the most affected sector was construction (0.104 KRW), followed by C12 transportation equipment (0.056 KRW), C05 chemicals (0.046 KRW), and C09 computers, electronics, and optics (0.046 KRW). In addition, the supply shortage effect of T-KIBS on P-KIBS was 0.041 KRW, the sixth highest. In contrast, the least affected sectors were B minerals at 0.001 KRW, T others at 0.001 KRW, and C13 other manufacturing products at 0.004 KRW. The primary, secondary, and tertiary industries accounted for 1.2%, 43.8%, and 55 %, respectively.

4.3. Results of the Economic Ripple Effect of the P-KIBS Industry

This section is an examination of the ripple effects of P-KIBS on the Korean economy (

Table 7). In addition, this study examined the effect of P-KIBS on T-KIBS. First, looking at the production inducement effects, the ripple effect of P-KIBS on other industries was 1.472 KRW, and the direct effect was 1.086 KRW, resulting in a total effect of 2.558 KRW. Looking at the sectors in which P-KIBS had the greatest impact, J broadcasting, newspaper, and publishing, had the largest at 0.136 KRW, followed by N business services at 0.111 KRW, T-KIBS at 0.120 KRW, and D electricity, gas, and steam at 0.102 KRW. Conversely, the industries least affected were P education services at 0.002 KRW, O public administration, defense, and social security at 0.002 KRW, and T others at 0.003 KRW. Among the indirect effects, the impacts on primary, secondary, and tertiary industries were 0.101 KRW (6.8%), 0.471 KRW (32.0%), and 0.901 KRW (61.2%), respectively.

In the case of value-added inducement effects, the indirect effect of P-KIBS on other industries was 0.646 KRW, and the direct effect was 0.301 KRW, for a total of 0.947 KRW. Among the indirect effects, the sectors that showed the largest effect were N Business Services at 0.075 KRW; T-KIBS at 0.067 KRW; J broadcasting and newspaper and publishing at 0.057 KRW; and L real estate services at 0.057 KRW. In contrast, the least affected sector was T others, with a value close to 0, followed by P education services, O public administration, defense, and social security with 0.001 KRW each, and C06 nonmetallic mineral products with 0.002 KRW. Among the indirect effects, the impacts on the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries were 0.048 KRW (7.5%), 0.141 KRW (21.9%), and 0.457 KRW (70.7%), respectively.

In the case of supply shortage effects, the sectors most affected by P-KIBS were C05 chemicals at 0.301 KRW, G wholesale and retail trade services at 0.234 KRW, C12 transportation equipment at 0.175 KRW, and F construction at 0.133 KRW, while T-KIBS had an effect of KRW 0.118. It was ranked seventh highest. However, the least affected sectors were T others at 0.002 KRW, B minerals at 0.003 KRW, and E water, waste disposal, and recycling services at 0.013 KRW. Thus, the supply shortage effect of P-KIBS on other industries was found to total 2.657 KRW, of which the primary industry accounted for 0.029 KRW or 1.1%, the secondary industry accounted for 51.5% with an effect of 1.368 KRW, and the tertiary industry accounted for 51.5% with an effect of 1.368 KRW. This accounted for 47.4% (1.261 KRW).

4.4. Results of the Economic Ripple Effect of KIBS Sectors

4.4.1. Results of Interlinkage Effects by KIBS Sectors

Table 8 presents the interlinkage effects of T-KIBS, P-KIBS, and KIBS. This allowed us to examine the role of each KIBS department in detail. First, the interlinkage effects were divided into forward and backward linkage effects. Here, forward linkage effects view the output of the analysis target as a raw material resource from another industry, while backward linkage effects, on the contrary, view the analysis target as a final good and view other industries as providing raw materials.

Based on this result, You and You (2009) divided the interlinkage effects into four types based on a value of 1 for each backward-linkage effect: “First, if the coefficients of all Backward linkage effects are high, it is a medium-demand manufacturing type. Second, if Backward linkage effects are low and Forward-linkage effects are high, it is a medium-demand primitive industry type. Third, if Forward linkage effects are low and Backward linkage effects are high, it is a medium-demand manufacturing type. If it is high, it is called final demand manufacturing type. Fourth, if both forward linkage effects and backward linkage effects are low, it is called final demand type of primitive industry type [

44].”

Based on this industry classification, the types of KIBS subsectors are classified as shown in

Table 8. First, considering P-KIBS, both forward and backward chain effects were greater than one; therefore, it is classified as a demand-manufacturing type. Legal and management support services, a detailed division of the P-KIBS sector, also appeared as the first-demand manufacturing type, with both forward and backward chain effects higher than one. Advertisement ranked third, with forward linkage effects lower than one and backward linkage effects higher than one. This is classified as final demand manufacturing. In the case of T-KIBS, all backward linkage effects showed values lower than one; therefore, it was classified as the fourth final demand type of the primitive industry, and all detailed sectors were classified as the fourth area.

As a result of analyzing the interlinkage effects by reorganizing a total of eight detailed divisions of KIBS into one division, it was classified as a second medium-demand manufacturing type with forward linkage effects higher than one and backward linkage effects lower than one.

In this way, it can be seen that each of the detailed divisions of KIBS plays a different role in the Korean economic system depending on industrial characteristics and maturity. In particular, this research confirmed that P-KIBS and T-KIBS perform distinctly different roles.

4.4.2. Results of Production Inducement Effects by KIBS Sectors

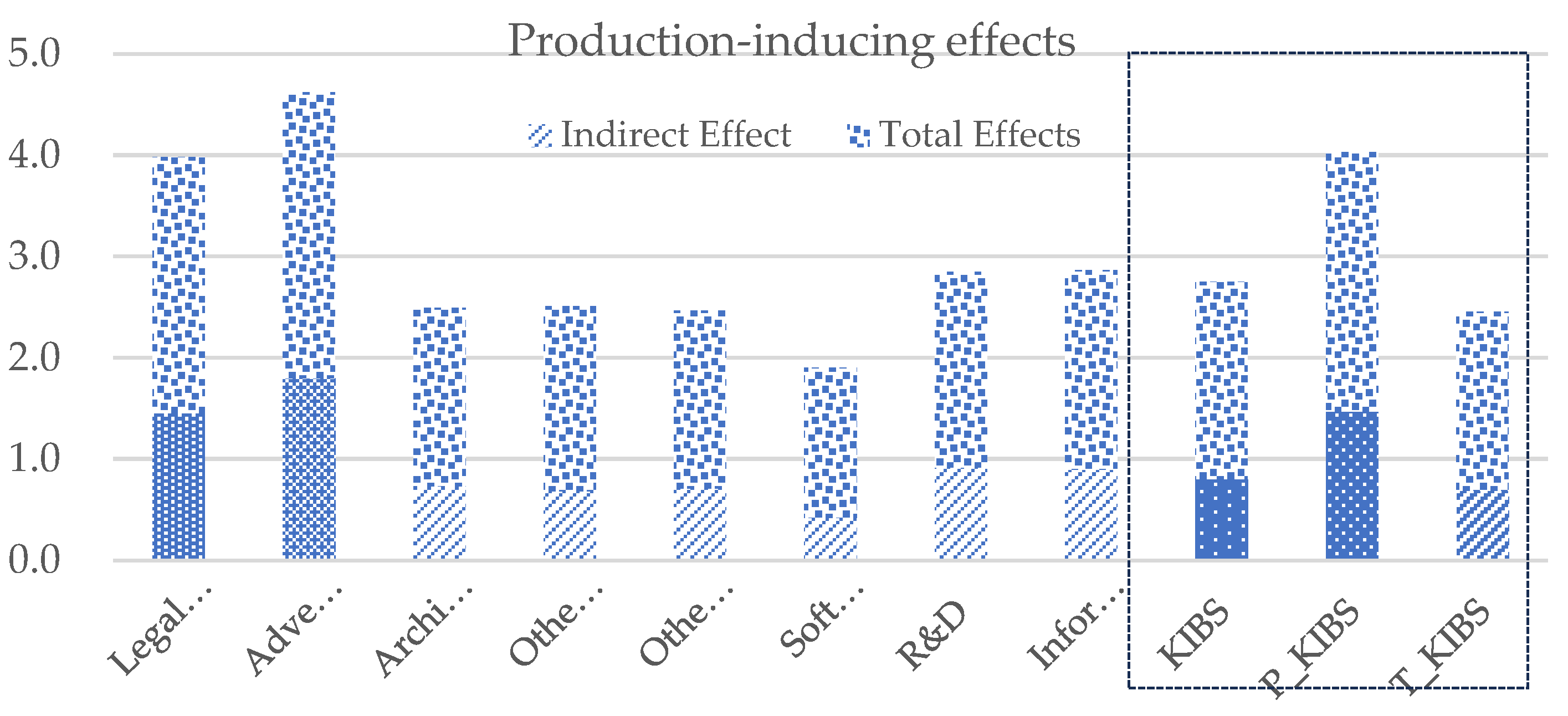

Table 9 compares the production inducement effects of the KIBS divisions. This table focuses on the differences in the indirect effects of each detailed KIBS sector and the proportion of the impact on each industry. First, looking at the indirect effect, advertisement, a subdivision of P-KIBS, was the highest at 1.801 KRW, followed by legal and management support services at 1.455 KRW. However, the production inducement effects of T-KIBS were weaker than those of P-KIBS alone. Among these, the sector with the highest figure was R&D at 0.920 KRW, followed by information services at 0.896 KRW, and the sector with the lowest figure was software development supply at 0.422 KRW. When P-KIBS were analyzed as one sector, the production inducement indirect effect was found to be 1.472 KRW, which was higher than the T-KIBS’ 0.687 KRW. When these two sectors were reorganized and analyzed as one KIBS sector, they were found to have an effect of 0.800 KRW (

Figure 2).

When examining the production inducement effects of KIBS on other industries, the impact on primary industries was found to be in the single digits, ranging from 2.8% to 7.6% across all detailed subsectors. In contrast, the effects on secondary industries ranged significantly from 18.9% to 47.6%. Among the detailed subsectors, advertisements within the P-KIBS subcategory had the least impact, whereas the sector had the most substantial influence.

The proportion of impact on tertiary industries varied, with R&D having the lowest at 45.0%, and advertisements showing the highest at 78.3%. When considering P-KIBS and T-KIBS as a single category for analysis, P-KIBS demonstrated a more significant impact on secondary (32.0%) and tertiary industries (61.2%). By contrast, T-KIBS exhibited a slightly higher influence on the secondary (45.7%) and tertiary industries (48.7%). T-KIBS had a more balanced impact on both the secondary and tertiary sectors than P-KIBS.

4.4.3. Results of Value-Added Inducement Effects by KIBS Sector

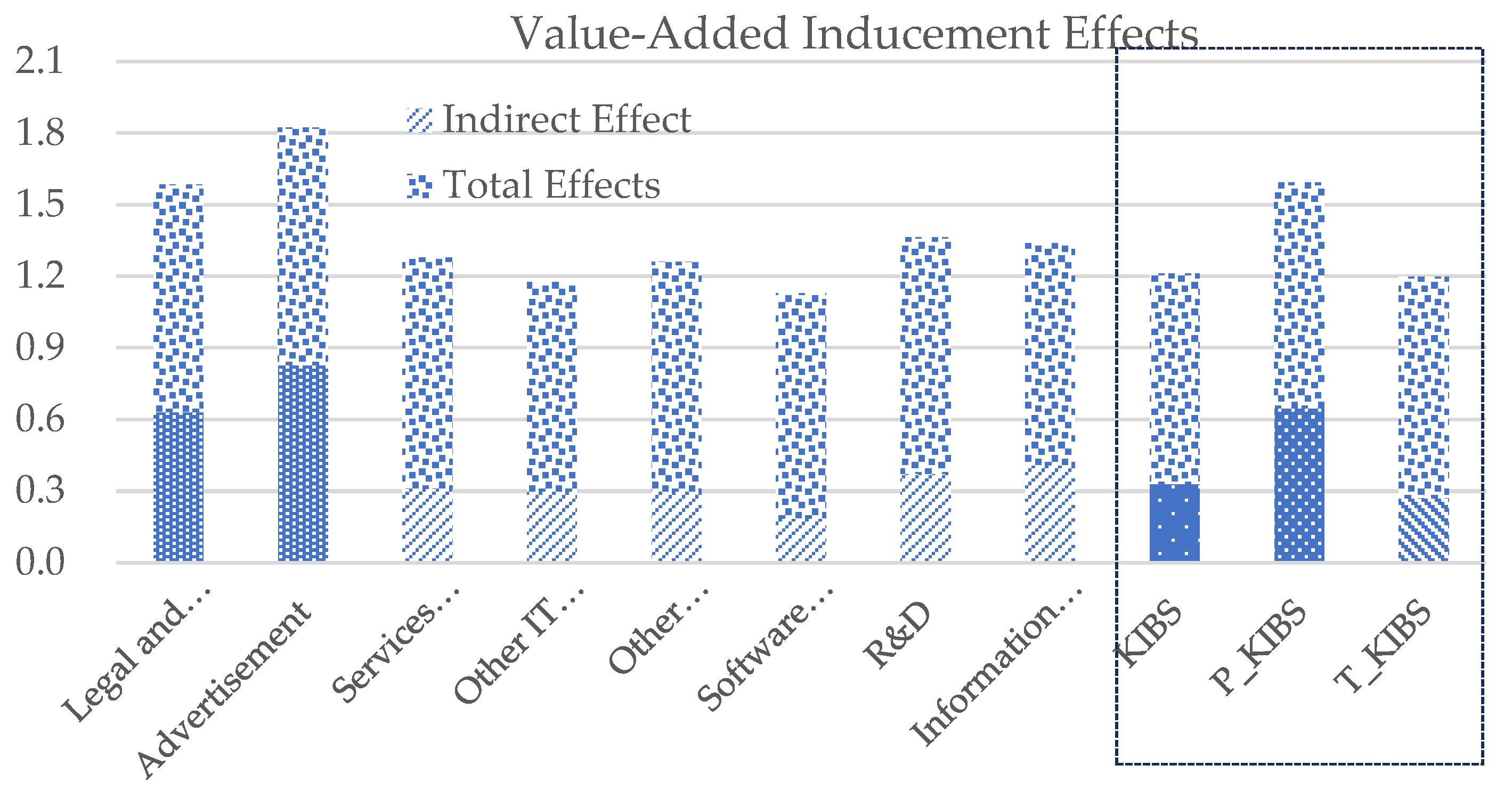

Table 10 compares the value-added inducement effects of the KIBS sectors. First, looking at the indirect effects on other industries, the sector with the greatest impact was advertisement, corresponding to P-KIBS with a KRW value of 0.828, followed by legal and management support services with a value of 0.63 KRW. Conversely, the sector with the least impact was software development supply, which corresponds to T-KIBS, at 0.184 KRW. Overall, the detailed sectors of T-KIBS showed lower value-added inducement effects on industries other than P-KIBS. However, when looking at the total effect, considering the sector’s own value-added inducement effects, advertisements showed the highest value at 0.996 KRW, but their own value-added inducement effects were the lowest at KRW 0.169. The next is R&D, which is the highest at 0.991 KRW, and architecture and civil engineering services, which had a value of 0.970 KRW (

Figure 3).

Analyzing P-KIBS and T-KIBS as one sector each, the value-added inducement effect on other industries for P-KIBS was 0.646 KRW, and for T-KIBS, it was 0.272 KRW, which is more than twice the value of P-KIBS. It showed a high value. However, if you look at the total effect, considering the direct effect, it can be seen that P-KIBS had a value of 0.947 KRW and T-KIBS had a value of 0.926 KRW, which were approximate figures compared with the indirect effect. P-KIBS showed a large indirect effect and T-KIBS showed a larger direct effect; thus, there was no significant difference in the total effect.

Next, when examining the impact that KIBS sectors have on other industry sectors, the influence on primary industries ranged from a minimum of 2.9%, observed in advertisement, to a maximum of 8.5% in legal and management support services. In secondary industry, advertising was the lowest at 12.7%, and R&D was the highest at 37.9%. In tertiary industry, R&D was the lowest at 55.1%, and advertising was the highest at 84.4%. When analyzing P-KIBS as a single sector, the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries accounted for 7.5%, 21.9%, and 70.7%, respectively. In addition, an analysis of T-KIBS showed that 6.9%, 36.4%, and 56.7% of the industries were composed of primary, secondary, and tertiary industries, respectively. Both KIBS sectors had a large impact on tertiary industry, and P-KIBS appeared to have an even greater impact on tertiary industry.

4.4.4. Results of Supply Shortage Effects by KIBS Sector

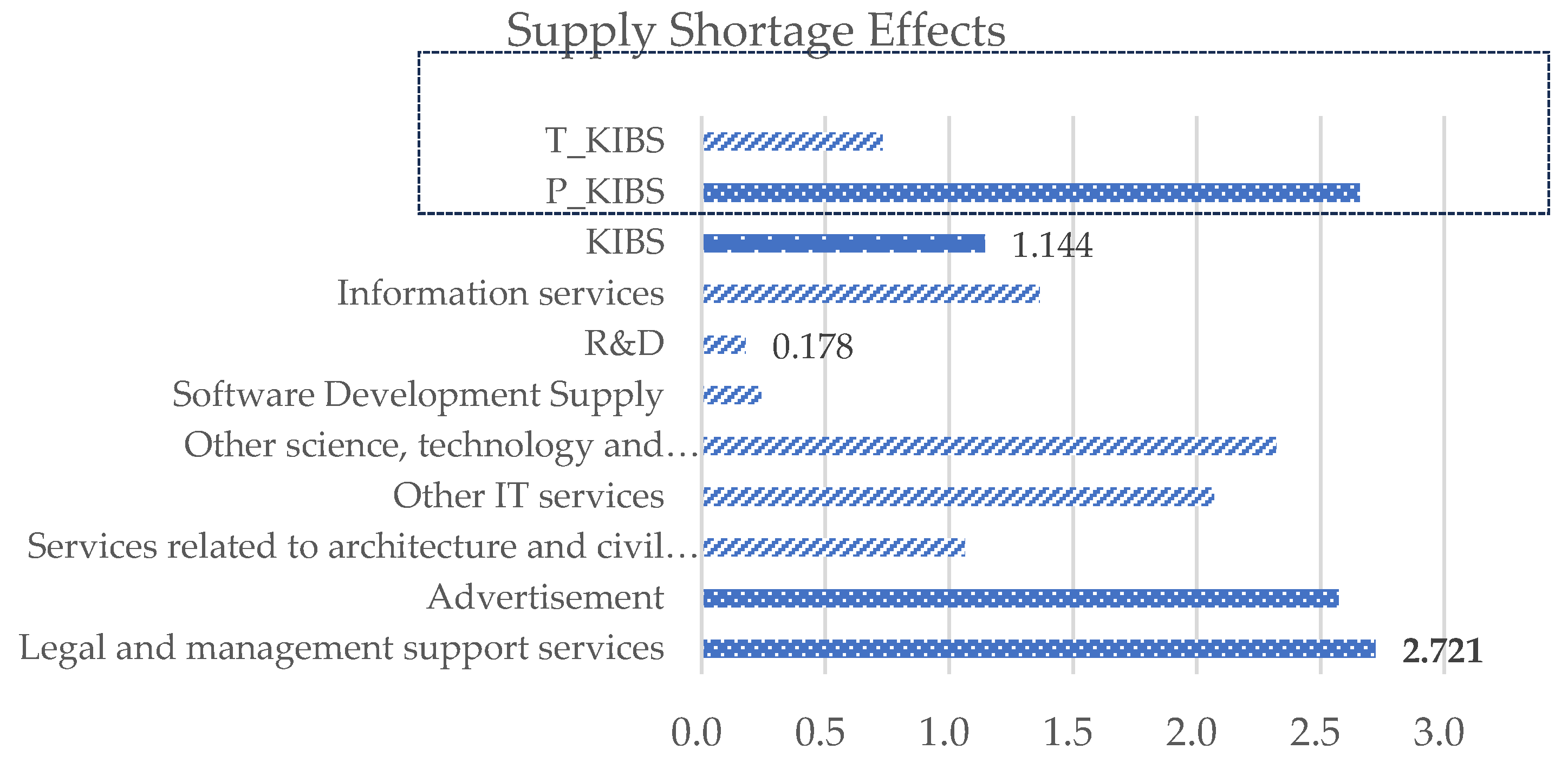

Table 11 compares the value-added inducement effects of the KIBS sectors. Among the KIBS subsectors, the sectors with the greatest supply shortage effects were the two P-KIBS subsectors, with legal and management support services at 2.721 KRW and advertisements at 2.573 KRW. Next, other science- and technology-related services earned 2.321 KRW and other IT services earned 2.071 KRW. Conversely, R&D showed the lowest figures at 0.178 KRW and software development supply had a value of 0.242 KRW. P-KIBS showed a high supply shortage effect of 2.657 KRW and T-KIBS showed 0.730 KRW(

Figure 4).

When examining industry-specific proportions, it is evident that in the primary industry sector, architecture and civil engineering services ranged from 0.1% to other science and technology-related services at 1.9%, showing proportions lower than the production value-added inducement effects. The impact on secondary industry was the lowest at 4.4% for architecture and civil engineering services and the highest at 68.7% for R&D. In the tertiary industry, R&D was the lowest at 30.7% and architecture and civil engineering services was the highest at 95.5%. For P-KIBS, the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries accounted for 1.1%, 51.5%, and 47.4%, respectively; for T-KIBS, the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries accounted for 1.2%, 43.8%, and 55%, respectively.

In the case of production and value-added inducement effects, both P-KIBS and T-KIBS had a significant impact on tertiary industry, and P-KIBS had a greater impact on tertiary industry. However, in terms of supply shortage effects, P-KIBS showed a higher impact on secondary industry, at 51.5%, than on tertiary industry. T-KIBS showed that tertiary industries accounted for more than the majority (55.0%), but the proportion of influence on secondary industries was also high, at 43.8%.

5. Conclusion

In this study, I investigated the role of KIBS, an innovation tool, in Korea’s economic system. For this purpose, the demand inducement, supply inducement, and interlinkage effects were analyzed using the 2019 industry linkage table published by the Bank of Korea for 2022. This method can identify the impact of the KIBS sector on the growth of other industries by analyzing production inducement effects, value-added inducement effects on the Korean economy, and its position in the Korean economic ecosystem through interlinkage effects. This analysis was conducted to compare and analyze each impact by analyzing the overall KIBS sector, T-KIBS, P-KIBS, and detailed subsectors of KIBS. These methodologies and approaches can provide useful information when attempting to foster innovation in the national economy and enhance the KIBS industry by identifying the impact and role of innovation in a detailed analysis of KIBS subsectors.

The following conclusions can be drawn based on the results: First, I confirmed that KIBS are growing as an industry in the Korean economy. Examining the proportion of KIBS demonstrates that the proportion of added value and job creation is high compared to the total output. In addition, the total output has grown rapidly at an average annual rate of 9.6% over the past 10 years. These results confirm that the demand for KIBS in other industries is increasing.

Second, when examining the results of the interlinkage effects, indicators have emerged that clearly demonstrate distinct roles within the South Korean economic system based on the type of KIBS. All KIBS were classified as medium-demand manufacturing, with forward linkage effects higher than the standard value of one and backward linkage effects lower than one. This can be attributed to the significant difference between the P-KIBS and T-KIBS results. This is because T-KIBS showed a value lower than the previous backward linkage effects’ standard value of one and were classified as a final demand type of primitive industry, whereas P-KIBS were classified as a demand manufacturing type higher than the standard value of one.

Third, the KIBS sector was confirmed to have different impacts on Korea depending on the impact indicators. In addition, it was confirmed that the differences varied depending on the KIBS type. The KIBS sector was found to have a high production inducement effect on other industries and evenly affected secondary and tertiary industries. Value-added inducement effects have a greater impact on tertiary industries than on secondary ones, and supply shortage effects appear to have a greater impact on secondary industries than the results obtained through the demand inducement model. Looking at the KIBS details, P-KIBS have a higher impact on industries than T-KIBS for all indicators. However, this indicator alone cannot be used to determine the more important type of KIBS.

These results and implications can provide the following policy and academic recommendations. In this study, I examined the role of KIBS, an innovation tool, by detailed sector using the characteristics of the industry relationship table. Through this analysis, i examined the production and value-added inducement effects, confirming that the KIBS sector plays a positive role in stimulating demand within the South Korean economy. Furthermore, different KIBS subsectors exert varying impacts on other industries, contingent on the unique characteristics of each sector.

This study is significant in that I not only analyzed KIBS as an industry group using the advantages provided by industry linkage analysis but also analyzed and compared detailed subsectors, thereby elaborately comparing the influence relationship between KIBS and other industries. Therefore, the results presented in this study are expected to be useful for fostering the KIBS industrial sector and establishing economic innovation policies using KIBS.

Despite these implications, this study has several limitations. First, it is difficult to clarify the reference points for the indicator results because comparisons with other countries have not been made. These issues pose a risk in that the interpretation and application of the results may differ depending on the people who use the data. I did not consider the scale of other industries in this study; therefore, additional research needs to be conducted to apply them to companies or specific industrial units.

Finally, it is necessary to conduct research on the business aspects to create value for smart farms. For Fourth Industrial Revolution technology to be applied to any industry and create value, managerial aspects must be considered. Only when these studies are conducted, and the results are applied, can the effects of the Fourth Industrial Revolution’s technology be discerned and economically sustainable growth achieved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J.S.; methodology, Y.J.S.; software, Y.J.S.; validation, Y.J.S.; formal analysis, Y.J.S.; investigation, Y.J.S.; resources and data curation, Y.J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.J.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.J.S.; supervision, Y.J.S.; project administration, Y.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by the Sahmyook University Research Fund in 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- The World Economic Forum, The Fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means, how to respond, 2016. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/ (accessed on 09 January 2024).

- Miles, I., Kastrinos, N., Flanagan, K., Bilderbeek, R., Den Hertog, P., Huntink, W.; Bouman, M. Knowledge-Intensive Business Services: Users. Carriers and Sources of Innovation, EIMS publication, 15, 1995.

- Hertog, P. D. Knowledge-intensive business services as co-producers of innovation. International journal of innovation management, 2000, 4(04), 491-528. [CrossRef]

- Muller, E.; Doloreux, D. What we should know about knowledge-intensive business services. Technology in society. 2009, 31(1), 64-72. [CrossRef]

- Muller, E.; Zenker, A. Business services as actors of knowledge transformation: the role of KIBS in regional and national innovation systems. Research policy. 2001, 30(9), 1501-1516. [CrossRef]

- Pina, K.; Tether, B. S. Towards understanding variety in knowledge intensive business services by distinguishing their knowledge bases. Research Policy. 2016, 45(2), 401-413. [CrossRef]

- Bessant, J.; Rush, H., Innovation Agents and Technology Transfer 1. In Services and the Knowledge-based Economy. Routledge, 2019, pp. 155-169.

- Hipp, C; Grupp, H. Innovation in the service sector: the demand for service-specific innovation measurement concepts and typologies. Research Policy. 2005, 34, 517–535. [CrossRef]

- Toivonen, M. Expertise as business: long-term development and future prospects of knowledge-intensive business services. Doctoral dissertation series, Helsinki University of Technology, Laboratory of Industrial Management. 2004.

- Wood, Peter. Consultancy and innovation: The business service revolution in Europe. Routledge. 2003.

- Czarnitzki, D.; Spielkamp, A. Business services in Germany: Bridges for innovation. The Service Industries. Journal. 2003, 23, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Gotsch, M.; Hipp, C. Measurement of innovation activities in the knowledge-intensive services industry: a trademark approach. The Service Industries Journal. 2012, 32(13), 2167-2184. The Service Industries Journal. [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, E., Vaillant, Y.; Vendrell-Herrero, F. Territorial servitization: Exploring the virtuous circle connecting knowledge-intensive services and new manufacturing businesses. International Journal of Production Economics. 2017, 192, 19-28. [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Partanen, J. Co-creating value from knowledge-intensive business services in manufacturing firms: The moderating role of relationship learning in supplier–customer interactions. Journal of business research. 2016, 69(7), 2498-2506. [CrossRef]

- Seclen, J. P.; Barrutia, J. KIBS and innovation in machine tool manufacturers. Evidence from the Basque Country. International Journal of Business. 2018, 10(2), 112-131. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, P; Strobl, E.; Watson, P. Innovation, market failures and policy implications of KIBS firms: The case of Trinidad and Tobago's oil and gas sector. Energy policy. 2021, 153, 112250.

- Bustinza, O. F; Opazo-Basáez, M.; Tarba, S. Exploring the interplay between Smart Manufacturing and KIBS firms in configuring product-service innovation performance. Technovation. 2022, 118, 102258. [CrossRef]

- Paallysaho, S.; Kuusisto, J. Intellectual property protection as a key driver of service innovation: an analysis of innovative KIBS businesses in Finland and the UK. International Journal of Services Technology and Management. 2008, 9(3-4), 268-284. [CrossRef]

- Ciriaci, D; Montresor, S.; Palma, D. Do KIBS make manufacturing more innovative? An empirical investigation of four European countries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2015, 95, 135-151. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y; Lattemann, C; Xing, Y.; Dorawa, D. The emergence of collaborative partnerships between knowledge-intensive business service (KIBS) and product companies: the case of Bremen, Germany. Regional Studies. 2019, 53(3), 376-387. [CrossRef]

- Almenar-Llongo, V; Muñoz-de-Prat, J.; Maldonado-Devis, M. Growth of total productivity of the factors, innovation and spillovers from advanced business services. Economic research-Ekonomska istraživanja. 2023, 36(2). [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J; Miles, I; Hull, R; Howells, J; Andersen, B. Introducing the new service economy. In: Andersen, B; Howells, J; Hull, R; Miles, I; Roberts, J. (Eds.), Knowledge and Innovation in the New Service Economy. Edward Elgar, pp. 1–6 (Chapter 1), 2020.

- Moulaert, F.; Djellal, F. Information technology consultancy firms: economies of agglomeration from a wide-area perspective. Urban Studies. 1995, 32(1), 105-122. [CrossRef]

- Gallouj, F. Knowledge-intensive business services: processing knowledge and producing innovation. In: Gadrey, J., Gallouj, F. (Eds.), Productivity Innovation and Knowledge in Services. Edward Elgar, 256–284 (Chapter 11), 2002.

- Aslesen, H. W.; Isaksen, A. New perspectives on knowledge-intensive services and innovation. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. 2007, 89(sup1), 45-58. [CrossRef]

- Tether, B.; Howells, J. Changing understanding of innovation in services. Innovation in Services. 2007, 9(9), 21–60. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, I. Knowledge-intensives services an innovation. In The handbook of services industries, ed. J.R. Bryson and P.W. Daniels, 246–275. Cheltenham, UK–Northampton, MA:Edward Elgar. 2007.

- Eurofound. The Future of Knowledge Intensive Business Services (KIBS) in Europe - unlocking the potential of the knowledge based economy, 2006. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/resources/article/2015/future-knowledge-intensive-business-services-kibs-europe-unlocking-potential (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Bettencourt, L. A; Ostrom, A. L; Brown, S. W.; Roundtree, R. I. Client co-production in knowledge-intensive business services. California management review. 2002, 44(4), 100–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumberova & Kanovska. Sustainable marketing strategy under globalization: A comparison of the P-KIBS and T-KIBS sectors. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 74, p. 01003). EDP Sciences, 2020.

- Koch, A.; Stahlecker, T. Regional innovation systems and the foundation of knowledge intensive business services. A comparative study in Bremen, Munich, and Stuttgart, Germany. European planning studies. 2006,14(2), 123-146. [CrossRef]

- Miozzo, M.; Grimshaw, D. (Eds.). Knowledge intensive business services: Organizational forms and national institutions. Edward Elgar Publishing. 2006.

- Amara, N; Landry, R; Halilem, N.; Traore, N. Patterns of innovation capabilities in KIBS firms: evidence from the 2003 statistics Canada innovation survey on services. Industry and Innovation. 2010, 17(2), 163-192. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A; Nieto, M. J.; Santamaría, L. International collaboration and innovation in professional and technological knowledge-intensive services. Industry and Innovation. 2018, 25(4), 408-431. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Armijos, M. Does public entrepreneurial financing contribute to territorial servitization in manufacturing and KIBS in the United States? Regional Studies. 2019, 53(3), 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MULER, E; Zenker, A.; Héraud, J. A. Knowledge Angels: Creative Individuals fostering Innovation in KIBS Observations from Canada, China, France, Germany and Spain. Management International/International Management/Gestión International. 2015, 19.

- Ye, K; Liu, G.; Shan, Y. Networked or Un-Networked? A Preliminary Study on KIBS-Based Sustainable Urban Development: The Case of China. Sustainability. 2016, 8(6), 509. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. M. Study on the Governance Mechanism of Innovation of High-Tech Industrial Cluster in China--Based On KIBS Collaboration. In 2016 International Conference on Management Science and Management Innovation. Atlantis Press, 2016 August.

- Wang, J; Zhang, X.; Yeh, A. G. Spatial proximity and location dynamics of knowledge-intensive business service in the Pearl River Delta, China. Habitat International. 2016, 53, 390-402. [CrossRef]

- Deng, W. A Comparative Study on Competitiveness of KIBS in HK and Singapore. Modern Economy. 2016, 7(10), 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearmur, R. Are cities the font of innovation? A critical review of the literature on cities and innovation. Cities. 2012, 29, S9–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gómez, J; Escandón-Charris, D; Moreno-Charris, A.; Zapata-Upegui, L. Analysis of the role of process innovation on export propensity in KIBS and non-KIBS firms in Colombia. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal. 2021, 31(3), 497-512. [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, P; Campanini, F.; Costa, S. Hybrid Innovation: The Case of the Italian Machine Tool Industry. Symphonya. 2012, 2012(1), 45-56. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.H.; Yoo, T.H. The role of the nuclear power generation in the Korean national economy: An input–output analysis. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2009, Volume 51, 86–92. [CrossRef]

- The Bank of Korea. Input-Output Statistics; The Bank of Korea: Seoul, South Korea, 2016.

- Miller, R. E.;Blair, P. D. Input-output analysis: foundations and extensions . Cambridge university press, Cambridge , UK, 2009.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).