Main Text

Seafood is the most traded agricultural commodity, and imported products fuel growth in global seafood consumption (FAO, 2022). The complexity and opacity of global supply chains, including the poor resolution of fisheries catch data, make it difficult to determine where the seafood that we consume originates. This is problematic as up to 20% of wild-caught seafood is captured through illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, which is riddled with ecological and social problems, from fish stock exhaustions to human rights abuses and support of criminal networks (Flothmann et al., 2010; Gephart et al., 2019; Song et al., 2020). Compared to other agricultural products, regulations for the international trade of seafood—including minimizing the prevalence of IUU products—are grossly insufficient.

The definition of IUU seafood is broad, but the focus of existing trade measures is denying entry of illegal catch (referring to seafood whose origin cannot be determined) into supply chains (He, 2018; Song et al., 2020). While the onus to combat IUU fishing mostly falls on countries registering the ships (flag states) and to the countries where the fishing occurs (coastal states), there is increasing recognition of the important roles of the landing sites (port states) and consumers (market states) (Ma, 2020; Young, 2016).

Import regulations targeting IUU products are rare, existing only in the EU, USA, South Korea, and Japan (

Table 1), and woefully inadequate at ensuring seafood is legal and traceable (Environmental Justice Foundation, 2023; He, 2018). Countries such as Australia, that rely heavily on seafood imports to meet demand, need effective seafood import regulations. Australia has made multiple commitments to legal, traceable, sustainable seafood trade, including the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), and has been a leader in promoting regional action to combat IUU fishing under UN affiliated organizations, such as the Regional Plan of Action on IUU fishing (Garcia Garcia et al., 2021; Vince et al., 2021). However, like most market states, Australia has little information about its market exposure to IUU products and lacks specific import controls to prevent import of IUU seafood into its markets despite importing two-thirds of its seafood (Garcia Garcia et al., 2021). To address this, the Australian government is currently developing an effective seafood import regulation policy that this paper directly informs.

Existing IUU Seafood Trade Measures

There are two broad approaches used to trace the origins and control the legality of internationally traded wild-caught seafood: catch documentation schemes and import monitoring programs (

Table 1). These measures are either unilateral (applied by a single market state) or multilateral (applied through an intergovernmental body such as a Regional Fisheries Management Organization (RFMO). Both approaches can be complemented by trade restrictive measures (e.g., embargoes or sanctions) to penalize jurisdictions that contravene fishing or trade regulations (

Table 1). Currently, sanctions are not systematically linked to catch documentation schemes or import monitoring programs; rather, they are a separate process that is often triggered by a State’s perception of the targeted flag, coastal, port or market state’s compliance with trade regulations (Hosch, 2016).

The defining aspect of a catch documentation scheme is a catch certificate that links to subsequent trade documents in the supply chain from production (fishing) through processing to the consumer market. The linked documentation tracks the quantity, source (fishing vessel), product form, legality, and movement of seafood through the supply chain (FAO, 2017). Three of the 17 major RFMOs are operating a catch documentation scheme for species under their mandate, which typically exclude secondary target species such as sharks and deep-sea fish (Crespo et al., 2019). The European Union was the first consumer market to implement a catch documentation scheme to control seafood imports under the EU-IUU Regulation in 2010 (

Table 1). Most recently, Japan has advertised the implementation of a scheme that covers four species groups and is based on the design of the EU scheme (He, 2018; Willette and Cheng, 2018). While Japanese law establishes the catch documentation scheme, the regulation underpinning the measure has not yet been passed, and implementation is based on a technical note with limited publicly available technical and legal details.

There is widespread confusion and misuse of the term ‘catch documentation scheme’, which is frequently used to describe measures that do not align with the specific criteria outlined by the FAO definition. For instance, South Korea requires a catch certificate to accompany certain imports, but it is not linked to trade documentation. Similarly, the USA’s Seafood Import Monitoring Program is sometimes referred to as a catch documentation scheme, when it is actually a recordkeeping initiative that looks backwards through the supply chain from the point of import to the source (He, 2018; Willette and Cheng, 2018). The USA program places the onus on importing companies to screen products arriving at the border and collect catch and landing information from suppliers. There is no involvement of public authorities along supply chains; the information is held by the importing company (not a government body) and is not centralized (He, 2018; Ma, 2020; Virdin et al., 2022), making the system fraught with loopholes.

Key Flaws in Existing Systems

Control of complex supply chains is limited

From fisheries management and trade perspectives, multilateral trade measures are preferred to unilateral systems, as they can mitigate IUU for an entire seafood species or product (Clarke, 2022; FAO, 1995; Garcia Garcia et al., 2021; Hosch, 2016). The three existing multilateral catch documentation schemes implemented by RFMOs arguably represent the most effective control of IUU seafood trade, but only apply to a limited number of species (Song et al., 2020; Young, 2016). These schemes have most successfully discouraged trade of illegal products in cases where the RFMO controls most or all of the production (fishing of the stock) and dominant market states demand compliance with that scheme. One example is toothfish, where the USA held such a large share of the import market that their demands for certificates from the governing RFMO affected every significant producer (Grilly et al., 2015). A similar situation occurred when Japan—which imported over 90% of bluefin tuna originating in the Atlantic—enforced the catch documentation regulations for Atlantic bluefin tuna at their border (Hosch, 2016). However, there is considerable variability among the 17 RFMOs in their capacity to implement an effective catch documentation scheme (Hosch, 2016; Song et al., 2020).

It is crucial that market states both support RFMOs and implement national trade regulations to address IUU fishing (Garcia Garcia et al., 2021; Song et al., 2020; Willette and Cheng, 2018). Most aspects of illegal fishing can only be detected and controlled at the source (e.g., the flag state) (Flothmann et al., 2010), meaning the issuance of the catch certificate and the ensuing traceability framework must be based on a solid design. Seafood supply chains tend to have many strong markets that lack IUU import controls, creating ample opportunities to trade IUU products (Hopkins et al., 2024). Even the EU scheme—which would be powerful as a multilateral system since the EU is the world’s largest seafood importer—remains vulnerable to fraud because it is still paper based and EU countries cannot collaborate and crosscheck documentation for products arriving at other EU borders.

The information sought is limited and not digitized

Even when a single market dominates, two major flaws with existing regulatory systems create opportunities to trade IUU products. Firstly, most systems are paper based, meaning the catch certificate is issued on paper even if it is eventually stored electronically. Paper certificates—even if later digitized—prevent real-time detection of duplicate certificates and mass balance monitoring of imported and exported products (Hopkins et al., 2024; Hosch, 2016). This creates serious challenges in terms of traceability and the ability to detect the laundering of products into certified supply streams (Di Vaio and Varriale, 2020). Secondly, existing systems do not mandate sufficient information to trace and detect fraud (e.g., the EU scheme does not record port and date of landing) (Hosch, 2016). Within the US program, importers in short supply chains might have sufficient clout to demand more comprehensive trade documentation, but control rapidly diminishes in longer supply chains.

Triggers for enforcement are ad hoc or non-existent

When the existing unilateral, paper-based systems detect fraud or noncompliance, the regulatory responses are not systematic, transparent, or even triggered. For instance, the EU carding system is not linked to specific violations of the catch documentation scheme (Young, 2016). The EU has only carded non-EU countries and has issued yellow and red cards haphazardly—close to half of which did not trade with the EU at the time of their first carding (e.g., Cambodia, Cameroon, Comoros)—meaning the resulting embargoes are pointless (Kadfak et al., 2023). In comparison, the US program provides a biennial report to Congress that transparently details fraud detections (Kadfak et al., 2023; Willette and Cheng, 2018), and the US recently issued sanctions against Mexico and Russia in response to documented detections of IUU fishing. However, this process for triggering regulatory action remains somewhat opaque.

Eight Key Design Criteria for Better Seafood Import Control Systems

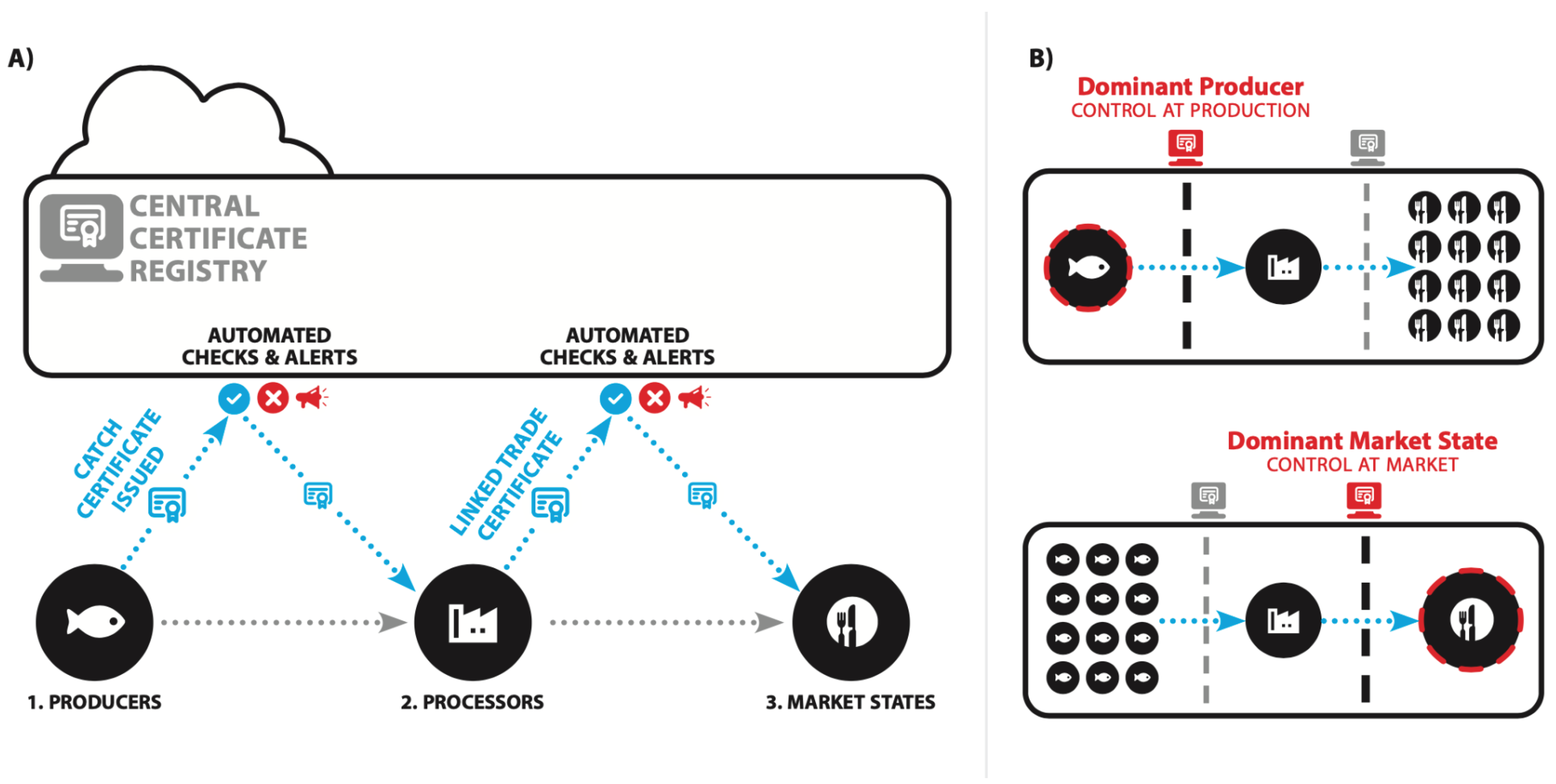

We encourage Australia to develop a policy that builds on the catch documentation scheme model but addresses the shortcomings observed in existing systems. A generic system that meets Australia’s needs—but is harmonized with existing systems run by countries or RFMOs—could be designed to encourage participation from other seafood importing countries (

Figure 1). By providing a platform for willing market states to join, Australia can create a multilateral system wherein the burden of compliance on the industry is reduced, costs are shared among participating market states, and the impact on IUU fishing is maximized.

A catch certificate covers the catch unloaded from a fishing vessel and is provided to the first buyer; a trade certificate is issued every time a batch of certified product is re-exported after processing, and certificates are sequentially linked as they are generated along the supply chain.

- 2.

Creation of a central certificate registry

To encourage multilateral participation and cost-sharing, we recommend establishing a single electronic registry through which countries can operate or join the certification system. This allows for the digitalization of data flows, allowing countries to sign on easily and benefit from the system’s tracing, tracking and management capabilities, including issuance and storage of all certificates. By pooling resources and sharing costs, participating countries can collectively ensure the effective operation and maintenance of the certification system.

- 3.

Electronic catch documentation system

It is imperative that the proposed certification system be entirely electronic—meaning catch and trade certificates must be both issued and stored electronically—leveraging advanced technologies for data capture, storage, and relational management. A paper-based approach is outdated and ineffective. An electronic system establishes hard links between certified incoming and outgoing lots throughout the supply chain, enabling monitoring and enforcement in real time for large volumes and multiple consignments moving across multiple borders (Di Vaio and Varriale, 2020).

- 4.

Automated Mass Balance Monitoring and Ongoing Access to Certificates

The sequential linking of certificates and their recording in a central registry are the centerpiece of the catch documentation scheme, enabling automated mass balance monitoring throughout the supply chain. The objective of this monitoring is to detect discrepancies, signaling laundering of product into legally certified supply streams. Any discrepancies would trigger an automated alarm when exporters file trade certificates for exportation, ensuring that no more than the original product received under any certificate could re-enter international trade. Source certificates of products entering a country should always be available to competent authorities—enabling the monitoring to operate at a speed matching the supply chain—so that refusal of tainted exports can occur prior to their exportation to the next country.

- 5.

5 Official validation process

The proposed system should be based on official validation and certification processes by public authorities overseeing the supply chain. Commercial entities in the supply chain could undergo vetting and authorization to contribute documentation to the system but they should not be responsible for collecting or verifying information from their suppliers, as required in the USA’s program. Official validation of certificates by public authorities ensures legitimacy and authenticity of circulating certificates and adherence to established standards and regulations. This enhances transparency and builds trust among all stakeholders (Hosch and Blaha, 2017).

- 6.

Integration with trade system infrastructure

To streamline operations and facilitate efficient handling, the proposed system should seamlessly integrate with existing trade system infrastructure, particularly customs processes (Di Vaio and Varriale, 2020). Recognizing that customs officials will primarily interact with the certification system, it is crucial to design a user-friendly interface that aligns with their workflows and maximizes their effectiveness. Spain has successfully integrated seafood trade and customs processes, providing a solid blueprint for this integration (Hosch, 2016).

- 7.

Minimum Key Data Elements and Unique IDs

To ensure compatibility with existing systems and facilitate interoperability, the proposed system should use a minimum and limited set of key data elements based on catch documentation templates currently used (Hopkins et al., 2024). Focusing on essential information avoids unnecessary complexity and reduces administrative burden. Additionally, the system could assign unique identifiers to each entity involved in the supply chain, enabling simple and effective tracking and traceability of seafood products while maintaining confidentiality.

- 8.

Wide scope of species coverage

The system should be designed to accommodate a wide range of species harvested in wild capture fisheries and entering world trade, including endangered ones. This ensures that a single system can cater for all certification needs, thus avoiding duplication or multiplication of platforms endeavoring to achieve the same goal. If interoperability across trade regulations like CITES is a design criterion, it should not add substantial cost to document trade of these species in a system focusing on IUU seafood. Moreover, broad species coverage denies opportunities to bypass certification requirements by mislabeling products as unregulated species. Currently, a substantial portion of internationally traded seafood is labeled in highly aggregated categories such as “marine fish” or “sharks and rays” (Roberson et al., 2020). This underlines the need for customs codes to continue to evolve and become more taxonomically detailed.

Australia’s Opportunity to Lead

Australia is currently developing a new system aiming to reduce the amount of IUU seafood entering its market. As its seafood market is relatively small, a unilateral approach would address the issue domestically but would not have a major effect on combating illegal seafood globally. However, there is an important opportunity for Australia to create a system that improves upon those developed by the EU, US, South Korea and Japan. Australia—which identifies as a leader in global marine conservation—should initiate unilateral trade measures to combat IUU fishing that are open to participation from other market states and can develop into a multilateral mechanism over time, thereby responding to UN Sustainable Development Goal 12 that calls for leadership from developed countries. The participation of additional market states in a shared platform would enable better detection of illegal seafood and exert downward pressure on illegal fishing globally. A single, centralized, and shared certification system would also help reduce the burden of compliance and streamline existing regulatory and enforcement systems that countries such as Australia have adopted to meet their international trade commitments. The foundation of this system remains rooted in the integrity of the trade documentation issued by flag states, meaning that robust monitoring, control, and surveillance systems must be in place to ensure the accuracy and reliability of catch certificates (He, 2018; Hosch, 2016). However, seafood importers can play a role in reducing IUU seafood trade by adopting well-designed import control policies with equitable and consistent enforcement measures. An initiative of this type supported by other cooperating and participating market states could make a substantial contribution to reducing IUU fishing, improving the health of the ocean and the millions of people that directly depend on it for sustenance and income.