Submitted:

12 January 2024

Posted:

12 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Overall Methods and Materials

2.1. Study area

2.2. Geography

2.3. Analyses

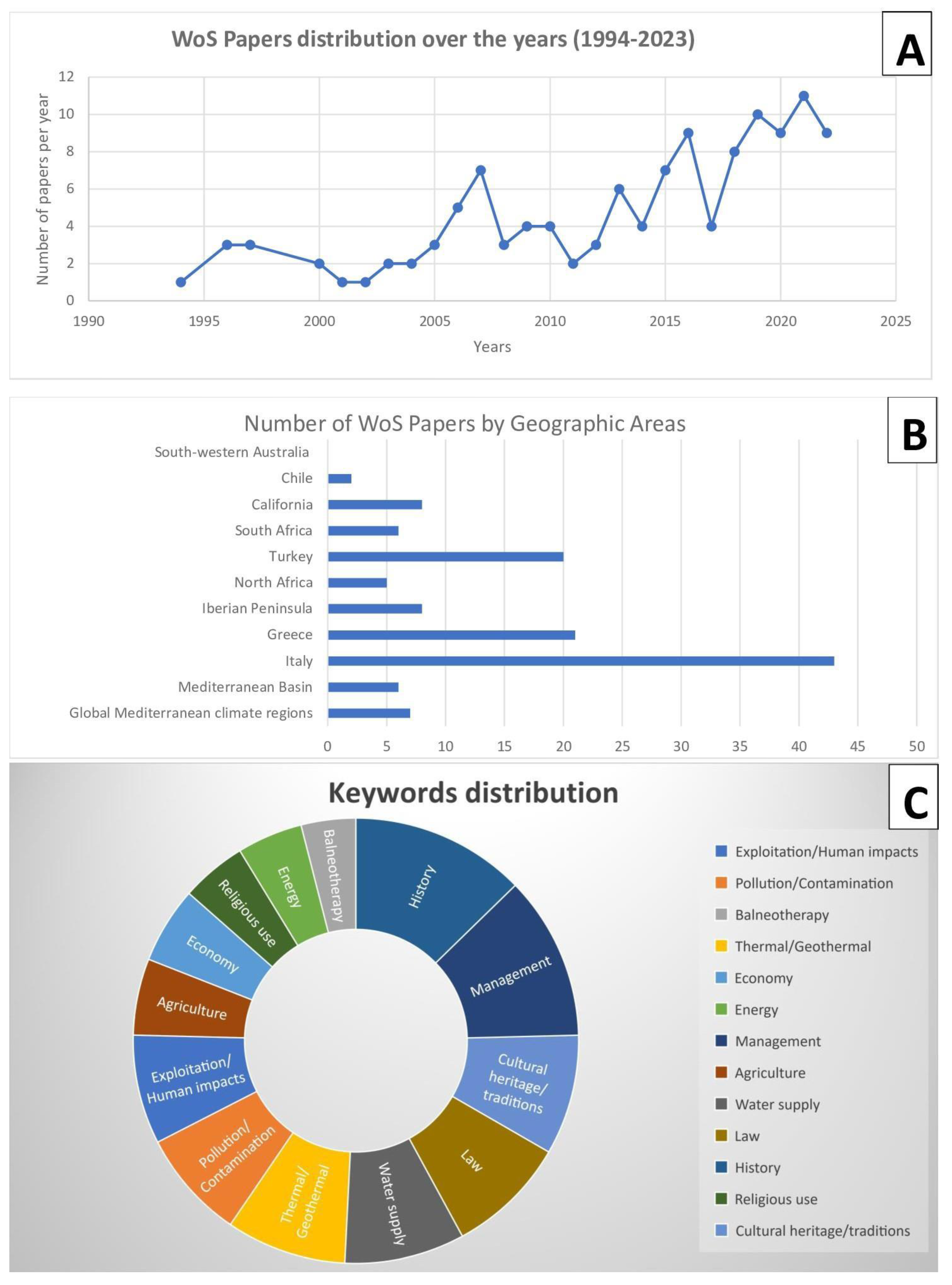

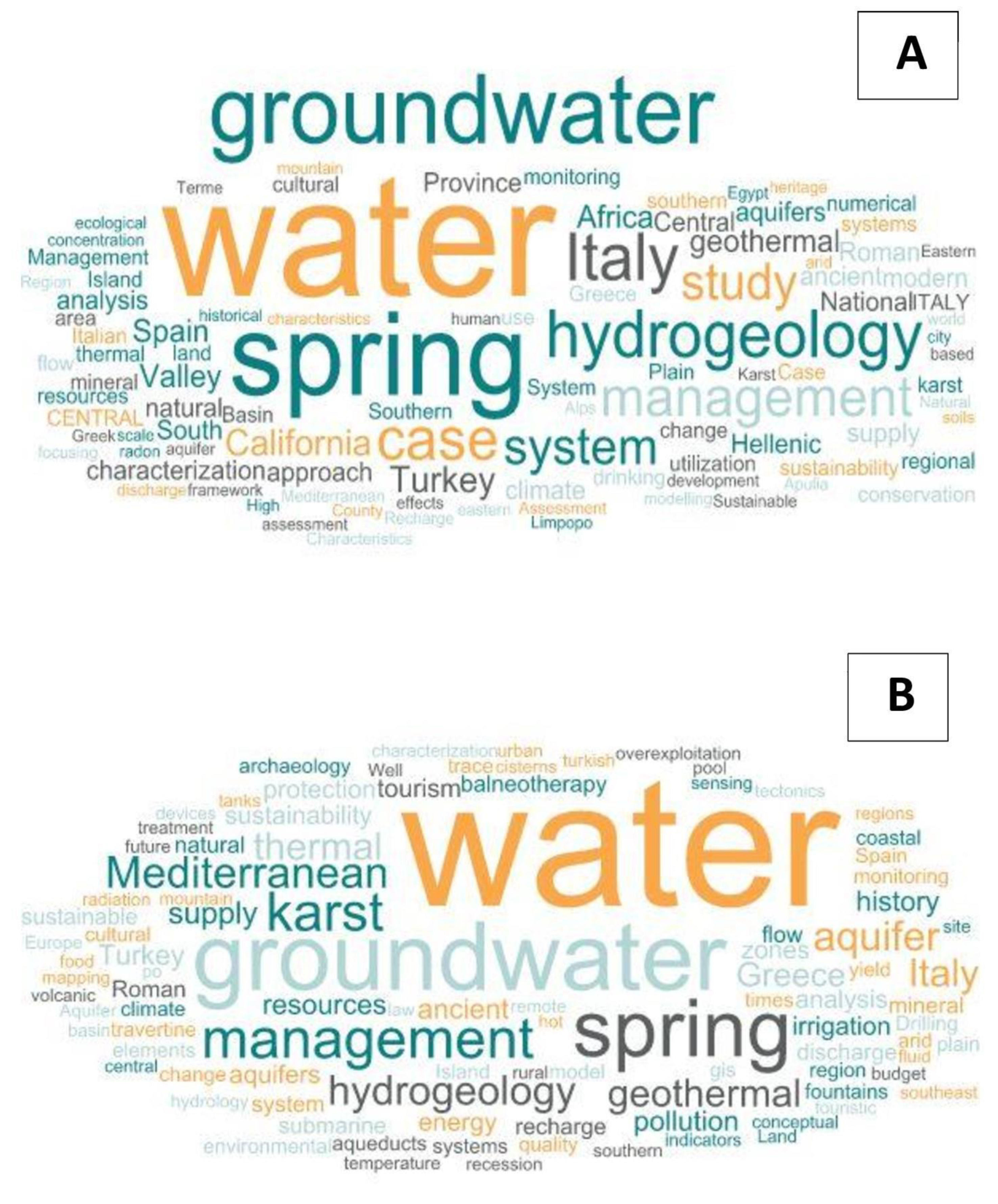

3. Results

3.1. Background - mediterranean basin ecology and cultural overview

3.1.1. Mediterranean-climate Zone Vegetation and Habitat

Vegetation

Aquatic Freshwater Habitats

Spring Riparian Habitats

3.2. Cultural Anthropology

3.2.1. History

3.2.2. Practical Uses and Threats

3.2.3. Mediterranean Stereotypes

3.2.4. Religion

3.3. Mediterranean basin case study 1: Springs of the Montsant Massif

3.3.1. Introduction

3.3.2. Methods

3.3.3. Results

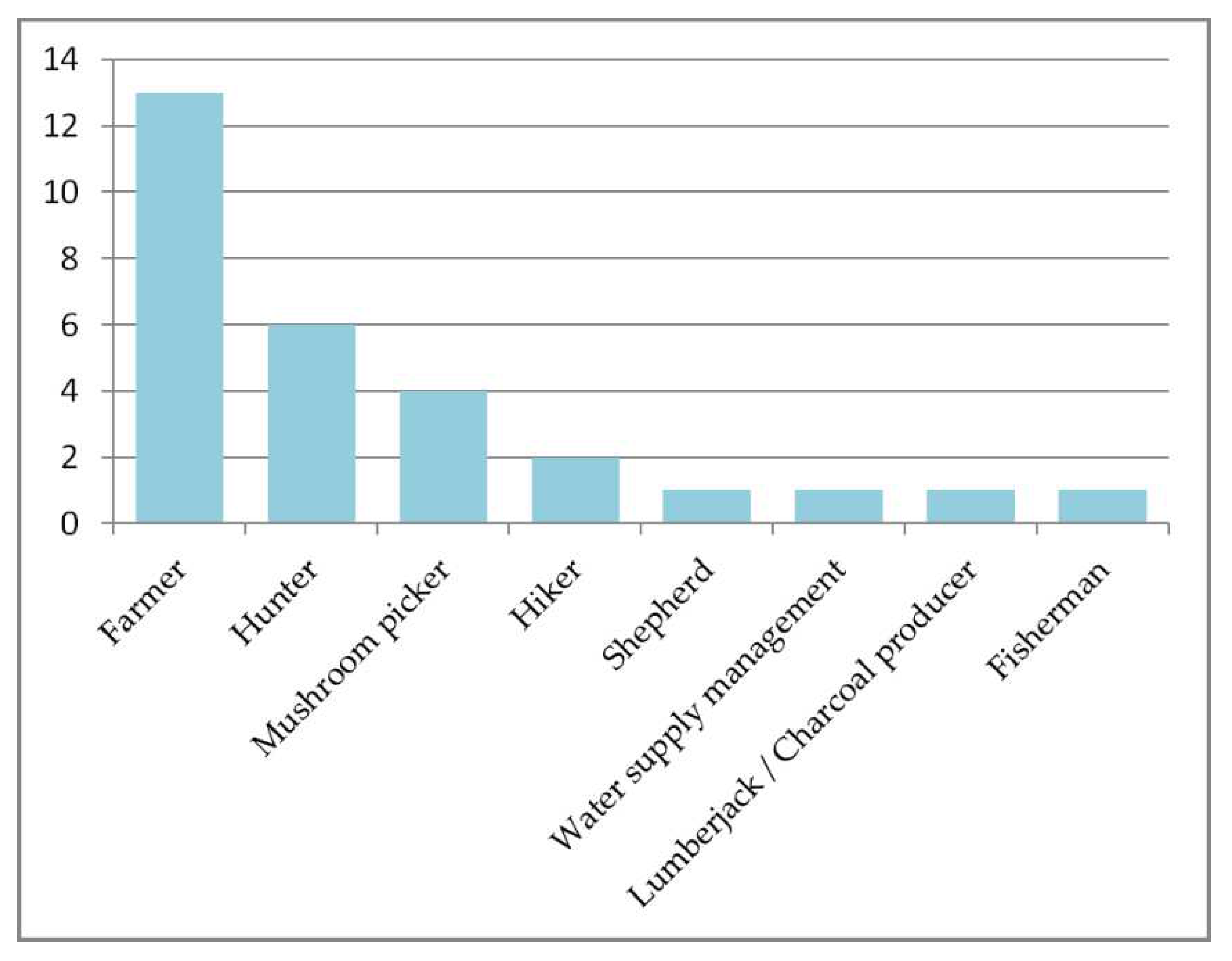

Informants

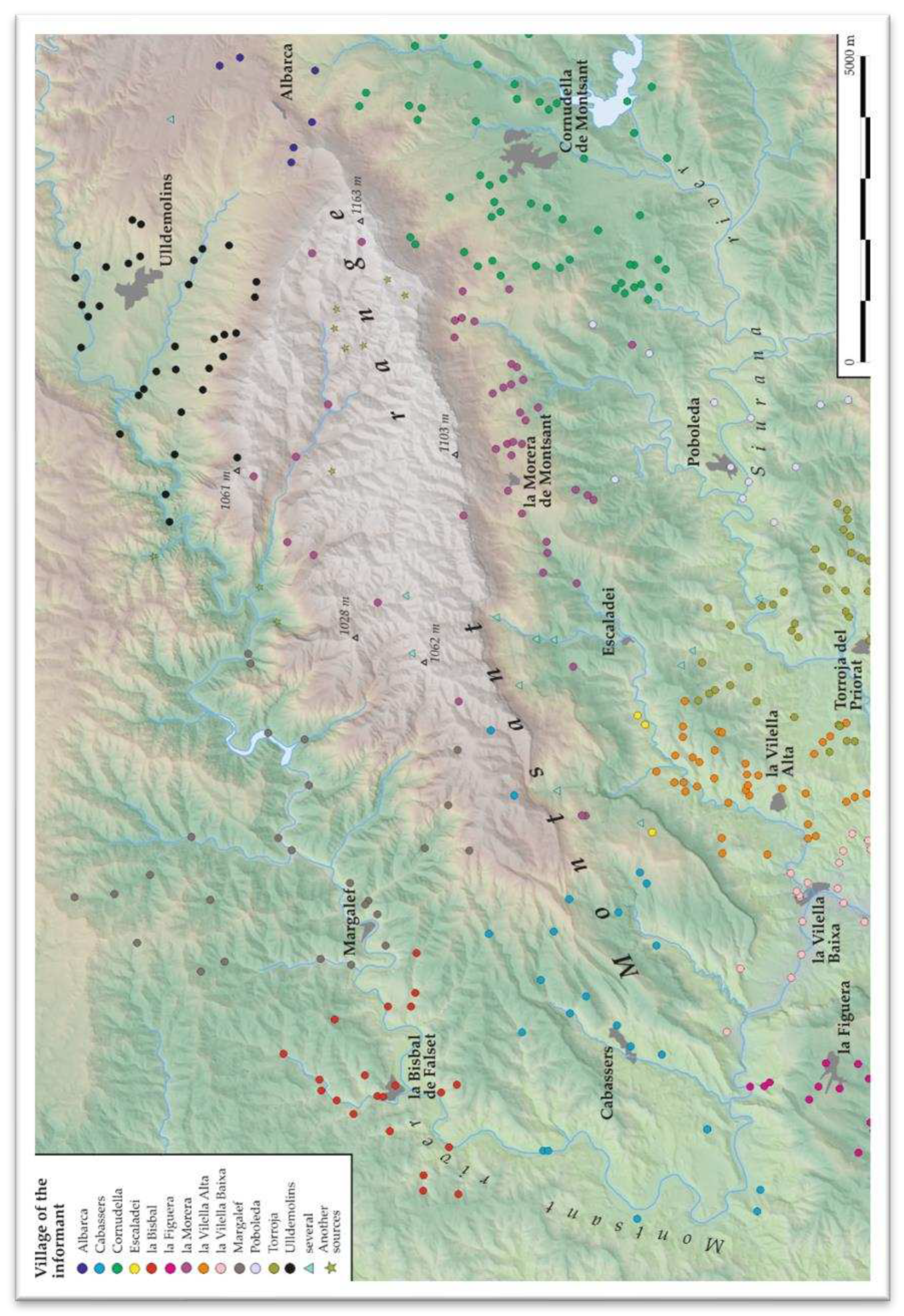

Springs in the Study Area

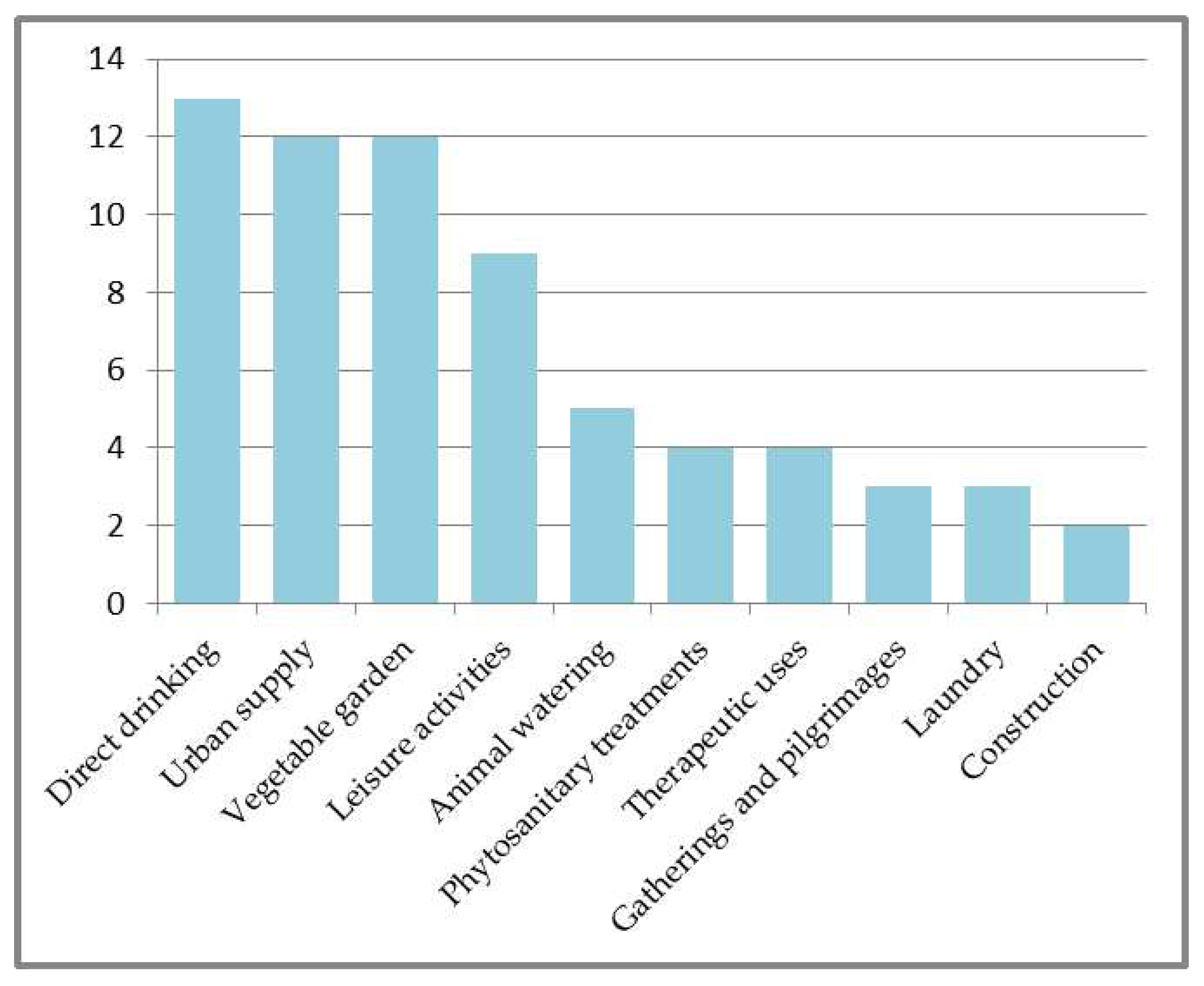

Traditional and Current Uses

Animal Watering

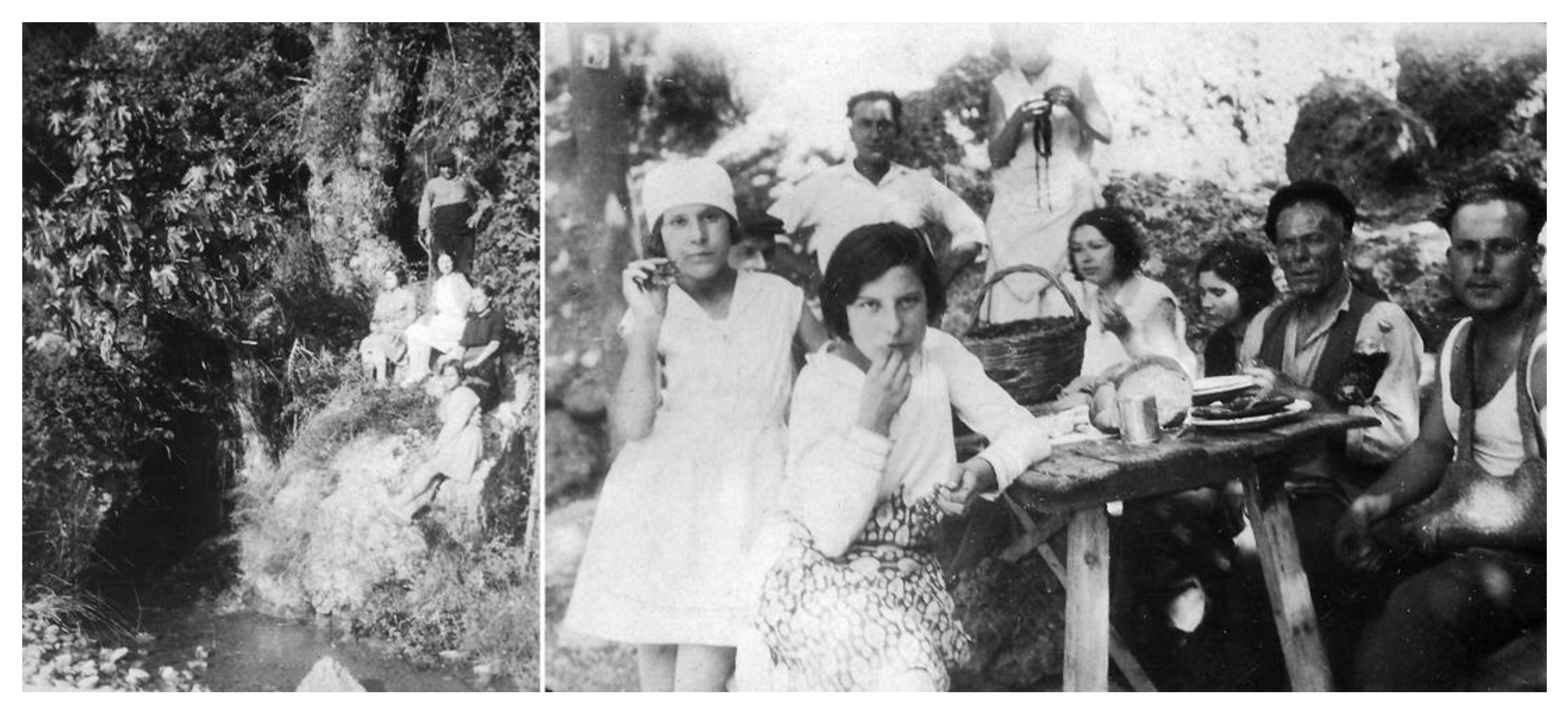

Celebrations

Long-term Discharge Variability

Rehabilitation of Lost Springs

Health and Balneotherapy

Legends, Mythology and Folklore

Other Aspects of Interest

3.3.4. Discussion and Conclusions

3.4. Mediterranean Basin Case Study 2: Mallorca Island Springs

3.4.1. Overview

3.4.2. Methods

3.4.3. Results

Mapping

Distribution

Typologies

- Degotís (dripping spring). Inside some caves and at the base of cliffs, in the places furthest from other water sources, there are some dripping springs that usually consist of ceramic cups or jugs, or small dug basins in which the water that falls from the roof is collected. In some of these there was no permanent structure, and the cups or jugs were carried by the people who wanted the water; some of these were on cliffs near the sea, where the men could leave the jug to fill while they were fishing (Example G in Fig. CS 1.2.4).

- Fonts or brolls (raw springs). Usually the brolls (D) are the simplest springs that flow from the ground, with little modification beyond perhaps excavation of a pool. Fonts, described below have a greater degree of development of dry-stone structures surrounding them (A). The degree of development structures is not related to the extent or quality of water management structures. Also, the exact point at which a spring becomes a mine is not easily determined, as they can sometimes be covered with shallow drystone structures (B).

- Fonts de mina (spring-flow tunnels). These are tunnels without any vertical shaft leading to the surface. Mines may not have internal structure (C) but may have small ponds at the beginning (B) or wells of depth. Some mines lying slightly below the water table also have been used as cisterns (H). Also, the mines that have been dug only in their initial point can transform into a well accessible by an underground staircase (I).

- Qanats. The qanats exist with the same variations seen in the font de mina category, but always have at least one vertical shaft (E, F, J). Also, there could be a noria on top of the first vertical shaft, leading to the irrigation of a bigger area situated at another level.

Historical Evolution of Spring Structures

Uses and Structures

Present Status and Future of Mallorca Springs

3.4.4. Discussion

3.5. Mediterranean Basin Case Study 3.1: North Africa

3.5.1. Introduction

3.5.2. Cultural and Religious Relationships

3.5.3. History

3.5.4. Socio-economics

3.6. Mediterranean Basin Case Study 3.2: Italy

3.6.1. Introduction

3.6.2. Archeology

- The Catania aqueduct was 24 km long and extended from Santa Maria di Licodia to Catania at the Benedictine monastery of San Nicola. The aqueduct was one of the most demanding hydraulic engineering works made by the Romans in Sicily. The springs emerged at the base of a rock cliff of effusive basalts, and were channelled towards the city with enough flow to satisfy the needs of the population and the functioning of the numerous baths and naumachia at that time. Today, some of the springs that supplied the city of Catania in Roman times now feed the Cherubino Fountain, which is fed by means of a pipeline and was reconstructed by the Benedictine fathers in 1757 (https://www.romanoimpero.com/2019/10/acquedotto-cornelio-di-termini-imerese.html; Branca et al., 2011).

- The Roman aqueduct of Olbia was built between the 1st and 2nd century AD. It was about seven km long from the springs of Cabu Abbas and directed via an underground pipeline to the baths of the ancient city. The source for these springs is a late Palaeozoic granitic aquifer.

- The Church of Santa Fiora in Tuscany was built in the 15th century during the Renaissance period. Archaeological excavations there were conducted for reconstruction of the church floor, and can still be admired through some of the glass tiles on the floor (Figure 18C). This site shows the place before the church was built and the presence of a clear, perennial spring.

3.6.3. Literature

3.6.4. Contemporary Uses

3.6.5. Socio-economics

3.7. Mediterranean Basin Case Study 3.3: Greece

Springs in Greek Mythology and Tradition

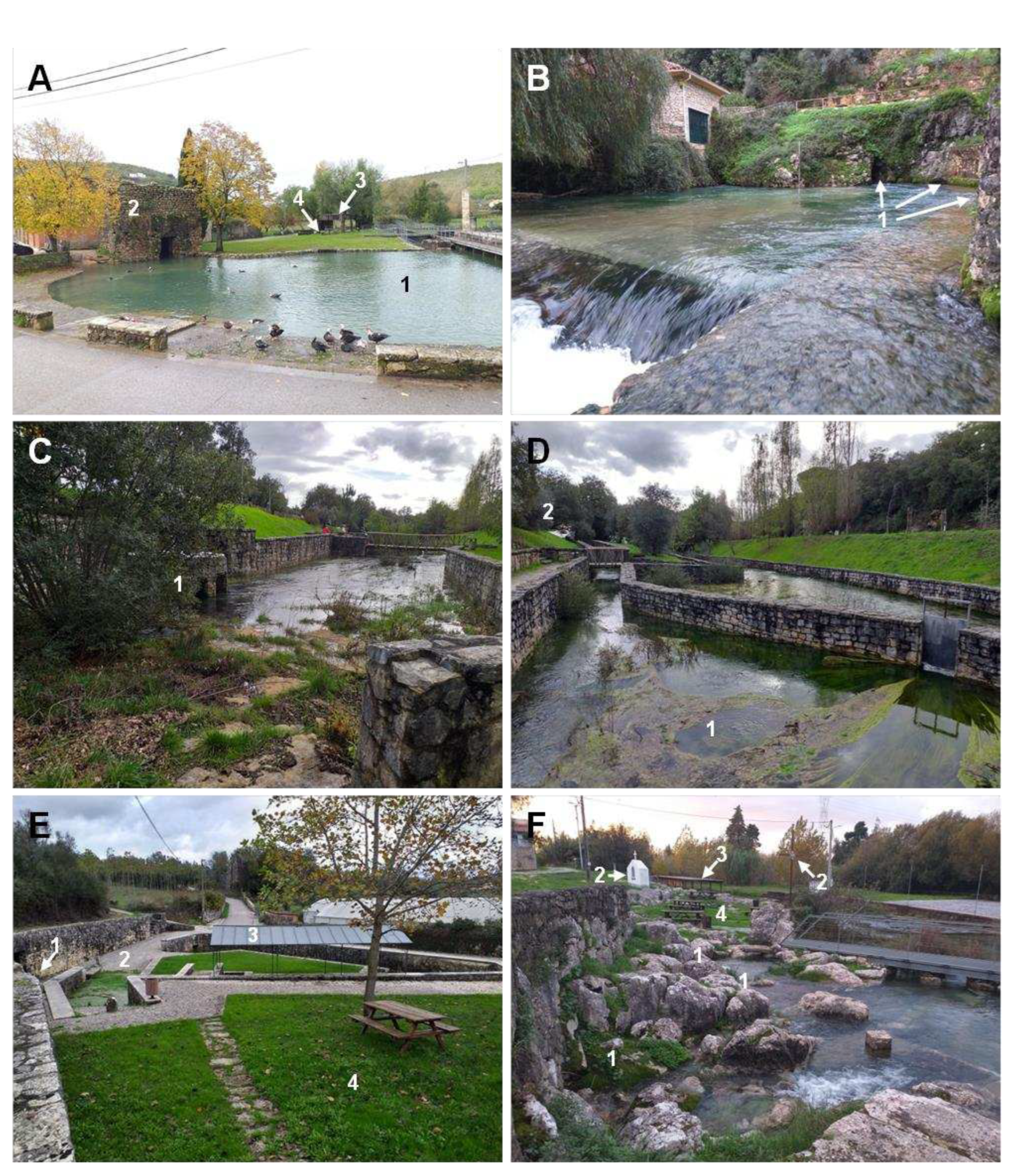

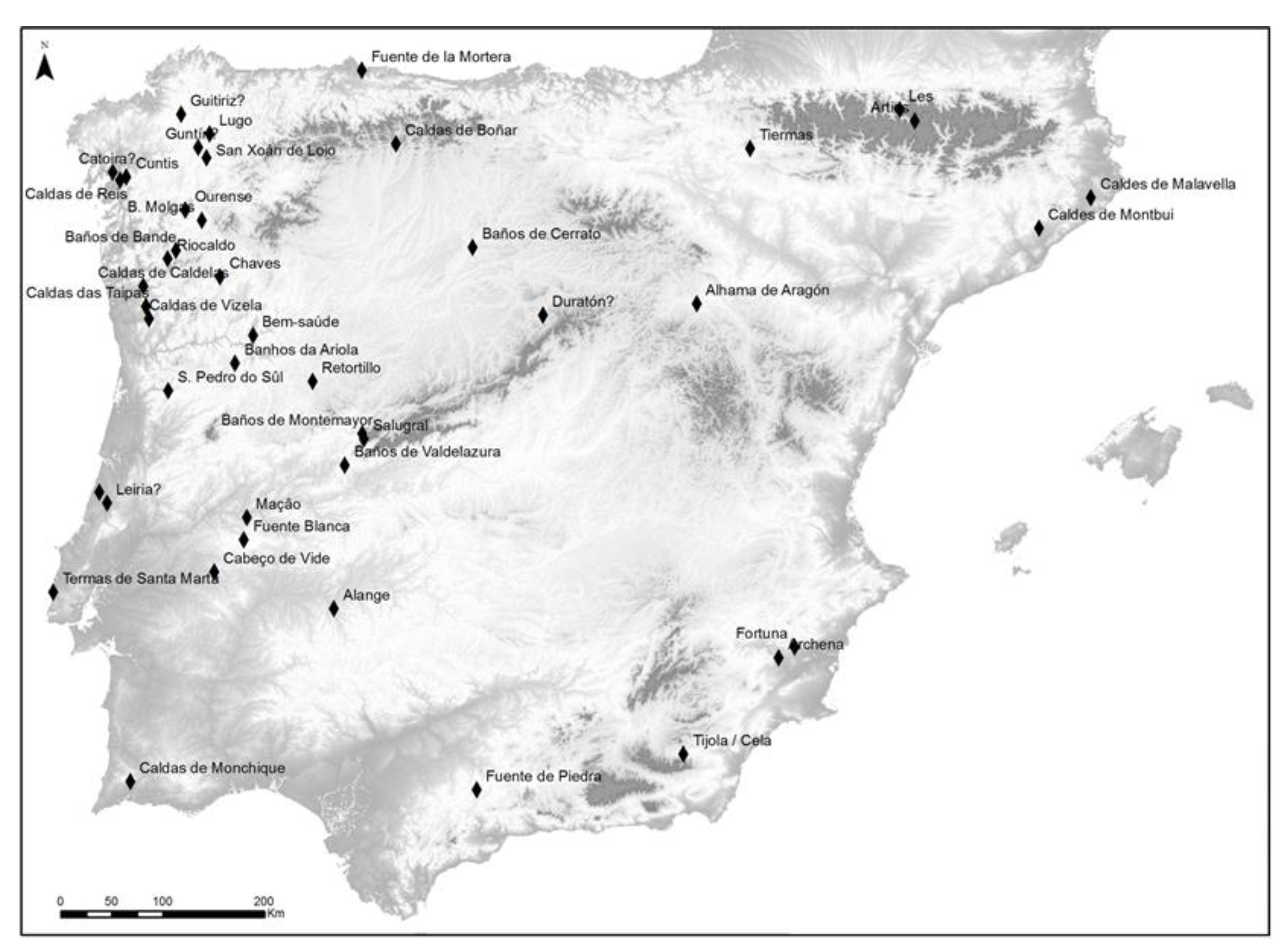

3.8. Mediterranean Basin Case Study 3.4: Iberian Peninsula

3.8.1. Archeology

3.8.2. Thermal springs and spas

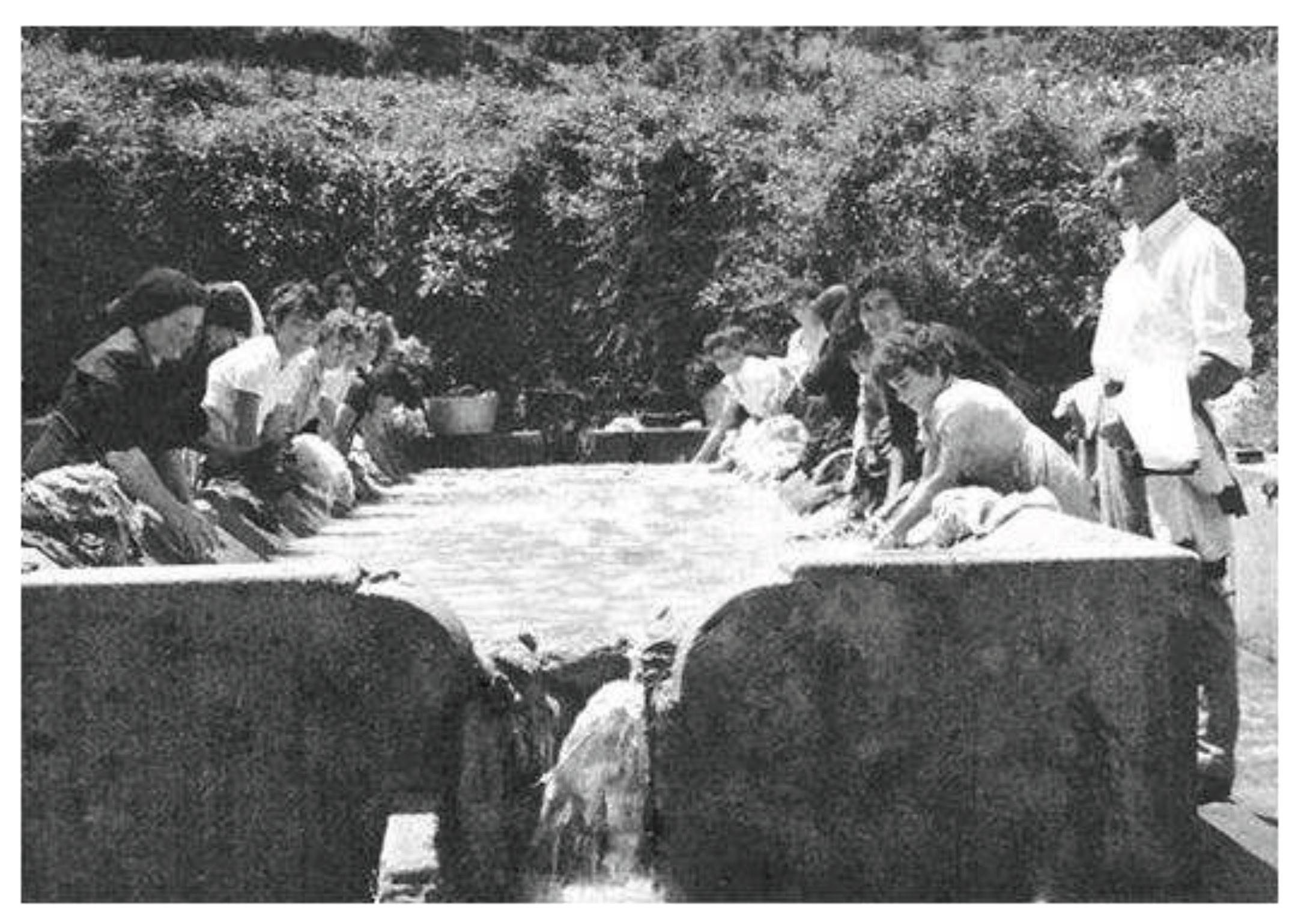

3.8.3. Residential, livestock, agricultural, and leisure uses

3.8.4. Biodiversity hotspots

3.8.5. Legends and myths

3.9. Mediterranean Basin Case Study 3.5: Turkey

3.9.1. Introduction

3.9.2. Structural Geology

3.9.3. History

3.9.4. Cultural Aspects

3.9.5. Economics

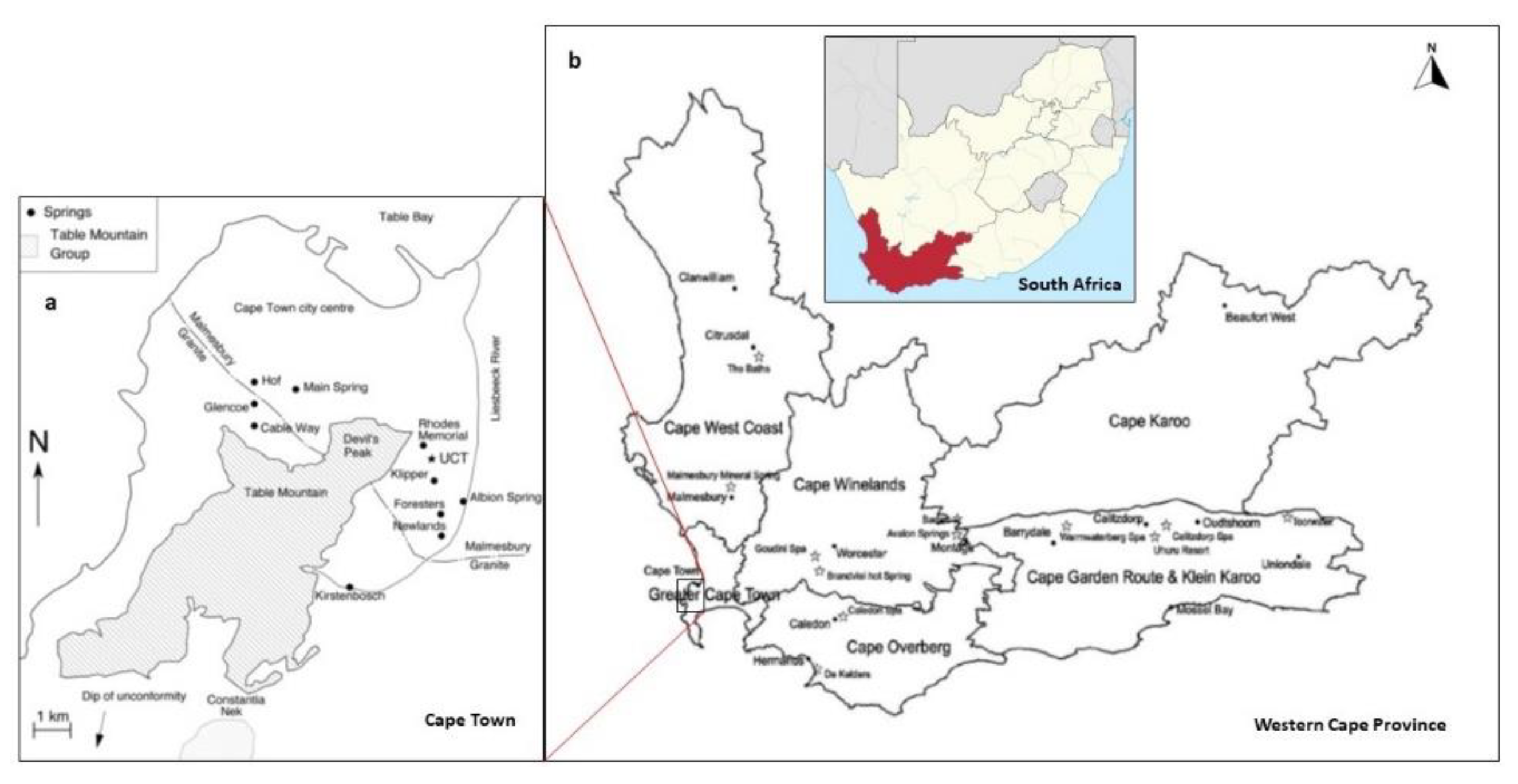

3.10. Case Study: Springs of the Western Cape, South Africa

3.10.1. Introduction

3.10.2. Hydrogeology

3.10.3. Cultural Significance

3.11. Case Study: Southwestern Australia

3.12. Case Study: California

3.12.1. Introduction

3.12.2. Indigenous Use

3.12.3. History

3.12.4. Bottled Water

3.12.5. Energy

3.12.6. Biology

3.13. Case Study: Moapa Warm Springs

3.13.1. Introduction

3.13.2. Archaeology and History

3.13.3. Site Ecology

3.13.4. Conservation

3.14. Case Study: Chile

3.14.1. Geography

3.14.2. Geology

3.14.3. History

3.14.4. Vegetation and Ethnobotany

3.14.5. Chilean Springs and Recreation

3.14.6. Conclusions

3.15. Case Study: Northwestern India and Eastern Himalaya

3.15.1. Introduction

3.15.2. History and Culture

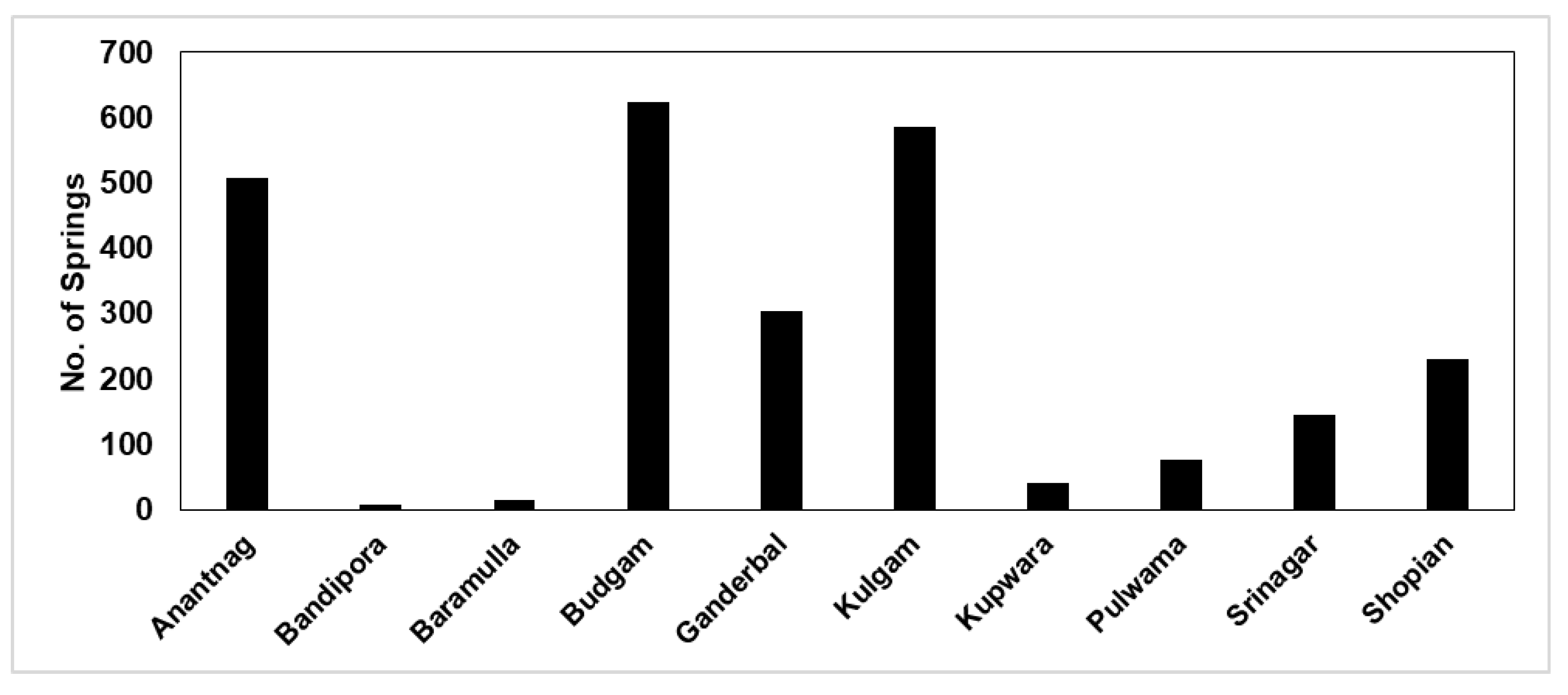

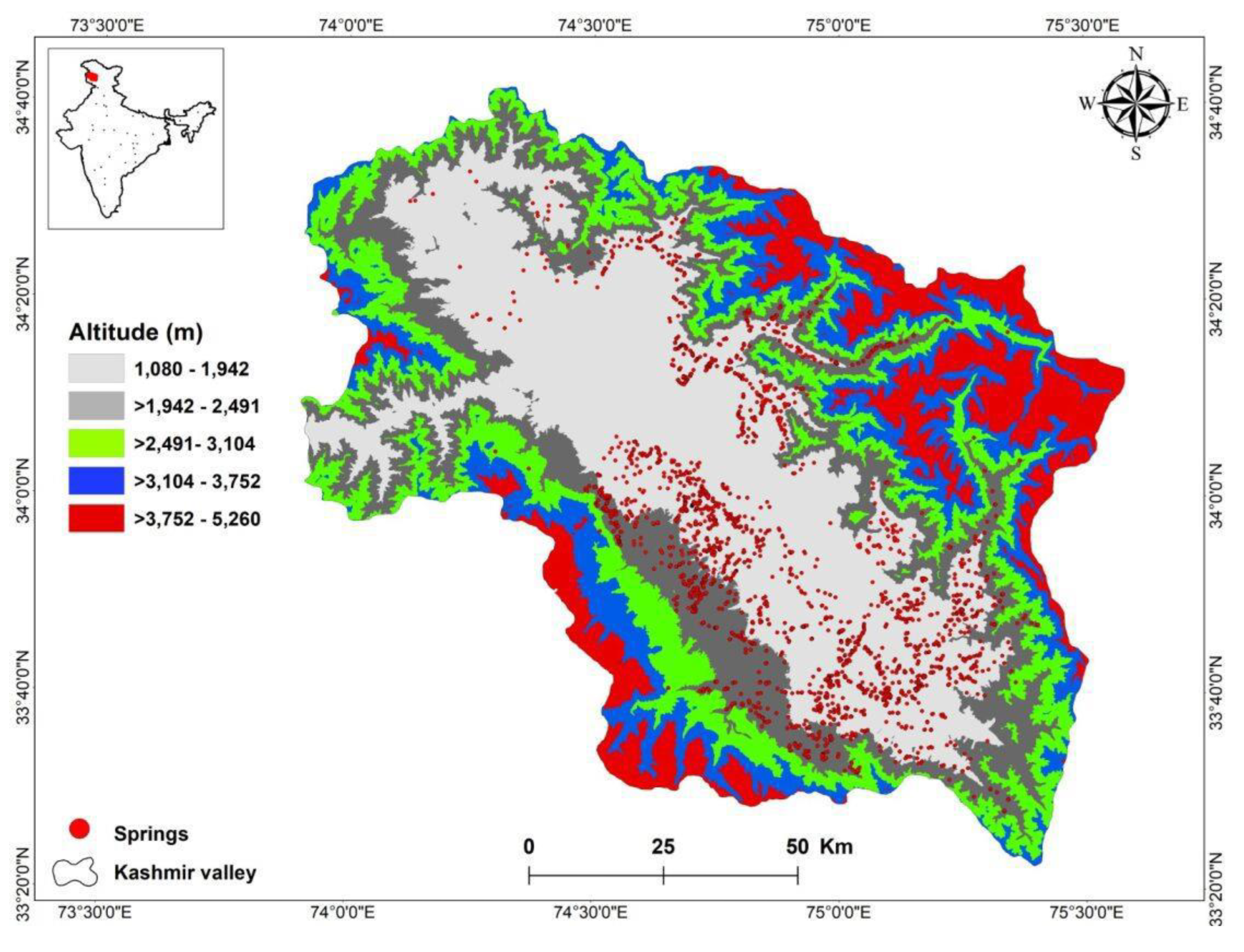

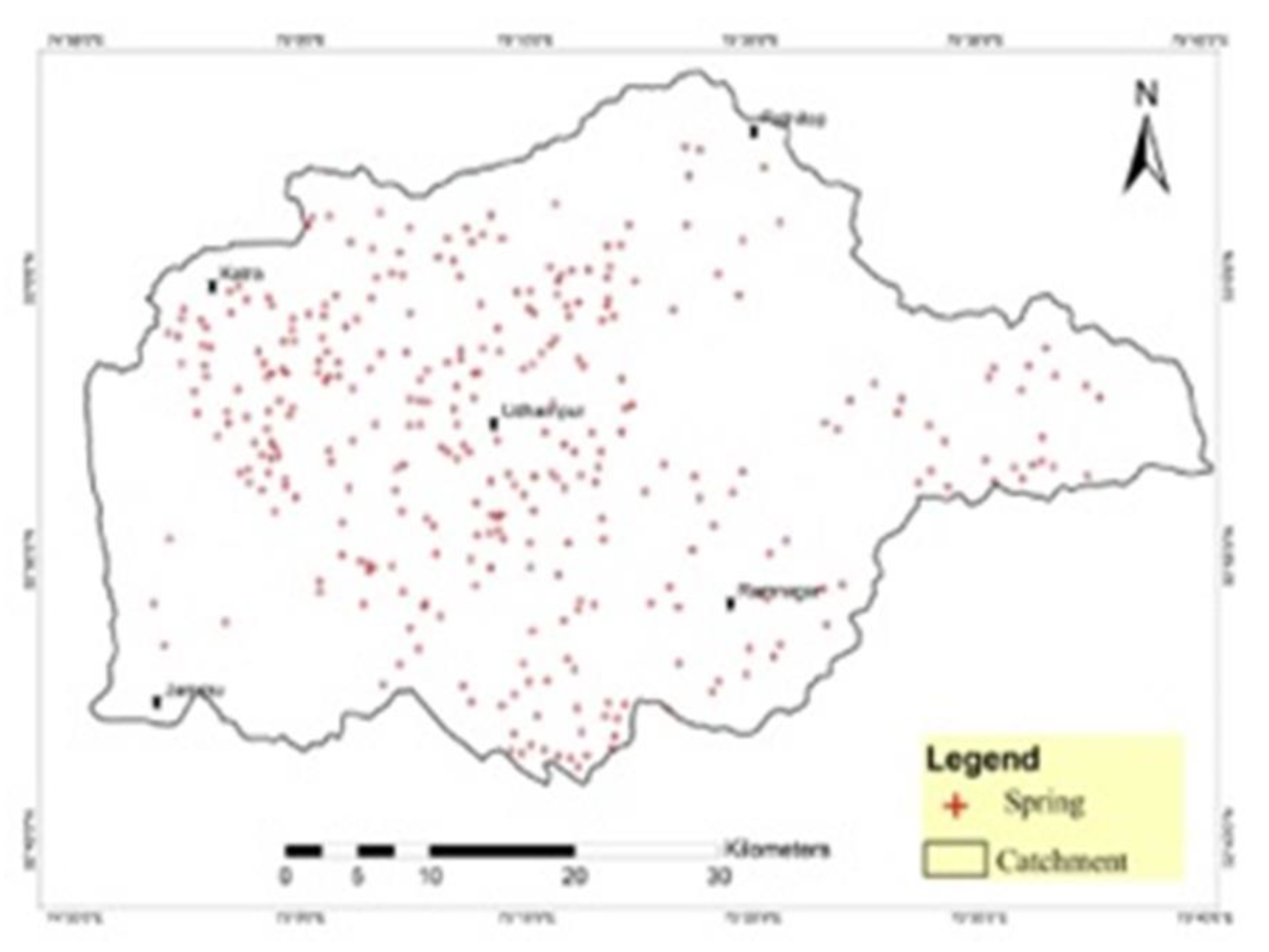

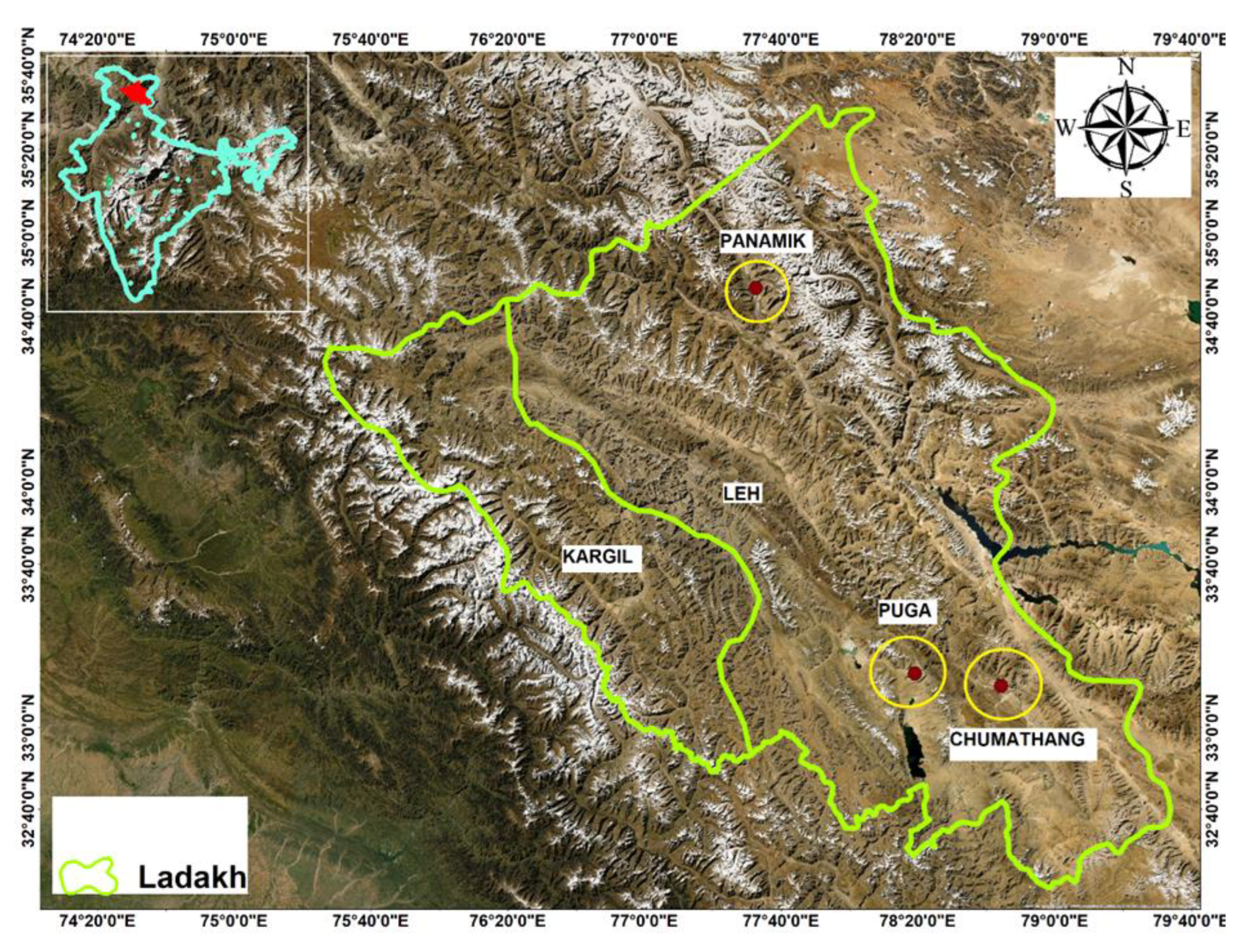

3.15.3. Springs Distribution

3.15.4. Economic Importance

3.15.5. Management and Protection

3.16. Case Study: The Galapagos Island of Floreana

3.16.1. Introduction

3.16.2. Geography and History

3.16.3. Satan Came to Eden

4. Collective Results and Discussion

4.1. Integrating the Literature Review with Case Studies

Overview

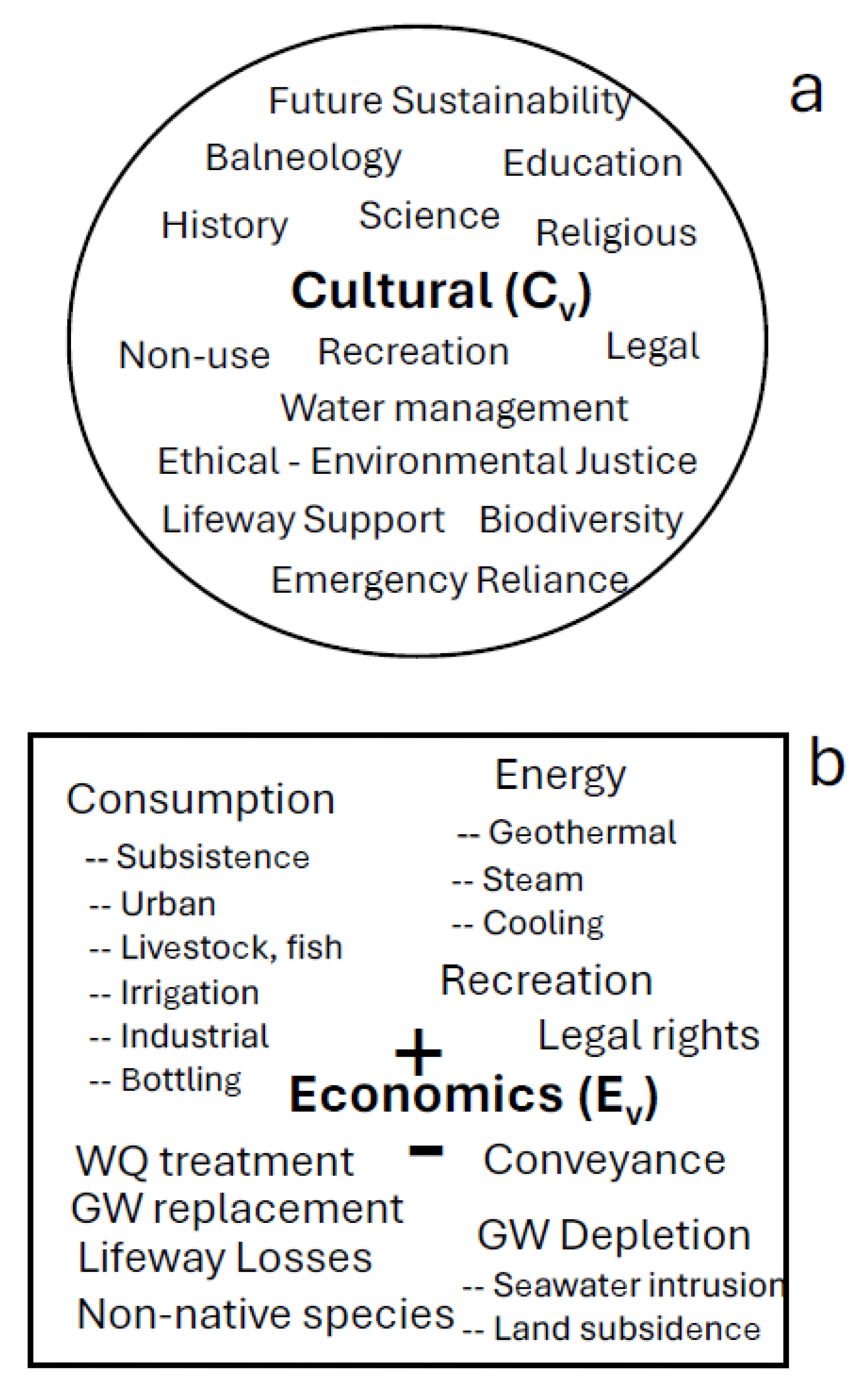

4.2. Cultural Valuation

4.2.1. Cultural Anthropology

4.2.2. History

4.2.3. Religious Values

4.2.4. Recreation

4.2.5. Balneotherapy

4.2.6. Law

4.2.7. Energy

4.2.8. Pollution/ Contamination

4.2.9. Socio-Economics

4.2.10. Management

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aayog, N. I. T. I. (2017). Inventory and revival of springs in the Himalayas for water security. Dept. of Science and Technology, Government of India, New Delhi.

- AbuZeid, K.; Abdel-Meguid, A. (2006). Water conflicts and conflict management mechanisms in the Middle East and North Africa region. Center for Environment and Development for the Arab Region and Europe (CEDARE), Egypt.

- Akman, Y., Ketenoğlu, O. 1986. The climate and vegetation of Turkey. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 89: 123–134.

- Altman, N. 2000. Healing Springs. The Ultimate Guide to Taking the Waters. Healing Arts Press, Rochester, Vermont.

- Altschul, J. and Fairley, H.C. 1989. Man, Models and Management: An Overview of the Archaeology of the Arizona Strip and the Management of Its Cultural Resources. Statistical Research Technical Series 11. SRI Press, Tucson. [CrossRef]

- America’s Test Kitchen. 2016. The complete Mediterranean cookbook: 500 vibrant, kitchen-tested recipes for living and eating well every day. Boston, America’s Test Kitchen.

- Angelakis, A.N., Valipour, M., Ahmed, A.T., Tzanakaris, V.A., Paranychianakis, N.V., Krasilnikoff, J.A. et al. (2021). Water conflicts: From ancient to modern times and in the future. Sustainability 13: 4237.

- Aranguren, B., Revedin, A., Amico, A., Cavulli, F., Giachi, G., Grimaldi, S., Macchioni, N.; Santaniello, F. (2018). Wooden tools and fire technology in the early Neanderthal site of Poggetti Vecchi (Italy). PNAS, 115, n°9, 2054-2059. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1716068115. [CrossRef]

- Arroyo M.T.K., P. Marquet, C. Marticorena, J. Simonetti, L. Cavieres, F.A. Squeo y R. Rozzi. 2004. Chilean winter rainfall – Valdivian forest: Pp. 99 – 103, 383. In: Mittermeier R.A., P Robles, M. Hoffmann, J. Pilgrim, T. Brooks, C. Mittermeier, J. Lamoreux y G.A.B. Da Fonseca. Hotspots: Earth’s Biological Richest and most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions. CEMEX, Mexico.

- Arroyo, M.T.K., Zedler, P.H., Fox, M.D. (eds.). 1995. Ecology and biogeography of Mediterranean ecosystems in Chile, California, and Australia. New York, Springer-Verlag.

- Aschmann, H. 1973. Distribution and peculiarity of Mediterranean ecosystems. In di Castri, F. and Mooney, H.A. (eds.). Mediterranean type ecosystems: origin and structure, pp. 11-19. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Aschmann, H. 1985. A Restrictive Definition of Mediterranean Climates. Bulletin de la Société Botanique de France 131:21-30.

- Atalay, İ., Efe, R., Öztürk, M. 2014. Effects of topography and climate on the ecology of Taurus Mountains in the Mediterranean region of Turkey. Procedia – Social and Behaaviour Sciences 120: 142–156.

- Athanasiadis, G., González-Pérez, E., Esteban, E., Dugoujon, J-M., Stoneking, M., Moral, P. 2010. The Mediterranean Sea as a barrier to gene flow: evidence from variation in and around the F7 and F12 genomic regions. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 10:84. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/84.

- Avşar, Ö., Avşar, U., Arslan, Ş., Kurtuluş, B., Niedermann, S., Güleç, N. 2017. Subaqueous hot springs in Köyceğiz Lake, Dalyan Channel and Fethiye-Göcek Bay (SW Turkey): Locations, chemistry and origins. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 345(1): 81–97.

- Axelrod, D.I. 1973. History of the Mediterranean ecosystem in California. Mediterranean type ecosystems: origin and structure, pp. 225-277. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Baker, A. (2018). What it’s like to live through Cape Town’s massive water crisis. Accessed 2023.12.11.https://time.com/cape-town-south-africa-water-crisis/.

- Balat, M. 2006. Current geothermal energy potential in Turkey and use of geothermal energy. Energy Sources, Part B 1:55–65.

- Ball, J. E., Bêche, L.A., Mendez, P.K., and Resh, V.H. 2012. Biodiversity in mediterranean-climate streams of California. Hydrobiologia. doi:10.1007/s10750-012-1368-6. [CrossRef]

- 4; Barnby, M. A., and V. H. Resh. 1988. Factors affecting the distribution of an endemic and a widespread species of brine fly (Diptera: Ephydridae) in a Northern California thermal saline spring. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 81:437-436.

- Bêche, L. A., E. P. McElravy, and V. H. Resh, 2006. Long-term seasonal variation of benthic-macroinvertebrate biological traits in two mediterranean-climate streams in California, USA. Freshwater Biology 51: 56–75.

- Benke, A. C., V. H. Resh, P. Mendez, P. B. Moyle, and S. V. Gregory. 2022. Pacific Coast Rivers of The Coterminous United States. p. 559-617. In: Delong, M. D., T. D. Jardine, A. C. Benke, and C. E. Cushing (Editors). Rivers of North America, Second Edition. Elsevier/Academic, New York.

- Benvenuti, M., Bahain, J.J.,Capalbo, C., Capretti, C., Ciani, F., D’Amico, C., Esu, D., Giachi, G., Giuliani, C., Gliozzi, E., Lazzeri, S., Macchioni, N., Mariotti Lippi, M., Masini, F., Mazza, P.P.A., Pallecchi, P., Revedin, A., Savorelli, A., Spadi, M., Sozzi, L., Vietti, A., Voltaggio, M.; Aranguren, B. (2017). Paleoenvironmental context of the early Neanderthals of Poggetti Vecchi for the late middle Pleistocene of Central Italy. Quaternary Research, 88(2), 327-344. doi:10.1017/qua.2017.51. [CrossRef]

- Berson J. 2014. The dialectal tribe and the Doctrine of Continuity. In Comparative Studies in Society and History 56:381–418.

- Bhat, S. U., Dar, S. A.; Hamid, A. (2022). A critical appraisal of the status and hydrogeochemical characteristics of freshwater springs in Kashmir Valley. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 5817.

- Bhat, S. U., Dar, S. A.;Sabha, I. 2021. Assessment of Threats to Freshwater Spring Ecosystems, Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences, Elsevier, 1-6 .

- Bhat, S.U., Mushtaq, S., Qayoom, U. and Sabha, I. 2020. Water quality scenario of Kashmir Himalayan Springs- A case study of Baramulla District, Kashmir Valley. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-020-04796-4. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.U., Nisa, A.U., Sabha, I and Mondal, N.C. 2022. Spring water quality assessment of Anantnag district of Kashmir Himalaya: Towards understanding the looming threats to spring ecosystem services. Applied Water Science. 12:180.

- Biltekin, D. 2010. Vegetation and climate of North Anatolian and North Aegean region since 7 Ma according to pollen analysis. Istanbul Technical University, PhD Thesis, 136 pp.

- Blinn, D. 2008. The extreme environment, trophic structure, and ecosystem dynamics of a large, fishless desert spring: Montezuma Well, Arizona. In Stevens, L.E., Meretsky, V.J., (Eds.); Aridland Springs in North America: Ecology and Conservation, Univ. Ariz. Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 98–126.

- Blumler, M.A. 2005. Three conflated definitions of Mediterranean climates. Middle States Geographer 38:52-60.

- Boekstein, M.S. and J.P. Spencer (2013). International trends in health tourism: Implications for thermal spring tourism in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 19(2), 287-298.

- Bonada, N., M. Rieradevall and N. Prat, 2007. Interaction of spatial and temporal heterogeneity: constraints on macroinvertebrate community structure and species traits in a Mediterranean river network. Hydrobiologia 589: 91–106.

- Bouffier, S. (2019). Arethusa and Kyane, Nymphs and Springs in Syracuse: Between Greece and Sicily. In Ancient Waterlands (pp. 159–181). Presses universitaires de Provence. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pup.40610. [CrossRef]

- Branca S., Coltelli M., Groppelli G., Lentini F. (2011) Geological map of Etna volcano, 1:50,000 scale. Ital. J. Geosci., 130 (3), 265-291. [CrossRef]

- Broad WJ. 2006. The Oracle: Ancient Delphi and the science behind its lost secrets. New York, Penguin Books.

- Callahan, C. A. 1965. Lake Miwok Dictionary. University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

- Cantonati M. & Ortler K. 1998. Using spring biota of pristine mountain areas for long term monitoring - Hydrology, Water Resources and Ecology in Headwaters (Proceedings of the Headwater’98 Conference held at Merano/Meran, Italy, April 1998). IAHS Publ. 248: 379-385. ISBN 1-901502-45-7.

- Cantonati M., Stevens L.E., Segadelli S., Springer A.E., Goldscheider N., Celico F., Filippini M., Ogata K. & Gargini A. 2020a. Ecohydrogeology: The interdisciplinary convergence needed to improve the study and stewardship of springs and other groundwater-dependent habitats, biota, and ecosystems. Ecological Indicators 110. [CrossRef]

- Cantonati M., Poikane S., Pringle C.M., Stevens L.E., Turak E., Heino J., Richardson J.S., Bolpagni R., Borrini A., Cid N., Čtvrtlíková M., Galassi D.M.P., Hájek M., Hawes I., Levkov Z., Naselli-Flores L., Saber A.A., Di Cicco M., Fiasca B., Hamilton P.B., Kubečka J., Segadelli S., Znachor P. 2020b. Characteristics, Main Impacts, and Stewardship of Natural and Artificial Freshwater Environments: Consequences for Biodiversity Conservation. Water 12: 260. [CrossRef]

- Cantonati, Fensham R.J., Stevens L.E., Gerecke R., Glazier D.S., Goldscheider N., Knight R.L., Richardson J.S., Springer A.E. & Tockner K. 2021. Urgent plea for global protection of springs. Conservation Biology 35(1): 378–382. [CrossRef]

- Cantonati M., Segadelli S., Ogata K., Tran H., Sanders D., Gerecke R., Rott E., Filippini M., Gargini A. & Celico F. 2016. A global review on ambient Limestone-Precipitating Springs (LPS): Hydrogeological setting, ecology, and conservation. Science of the Total Environment 568: 624–637. [CrossRef]

- Cape Town Magazine (2020). Newlands Spring: Cape Town’s favourite water source. Accessed 2023.12.11. https://www.capetownmagazine.com/collect-fresh-water.

- Caracciolo,G.G. 2018. L’Oro Blu del Matese, Gli Acquedotti Campano e Molisano Destro, Piedimonte Matese, ASMV.

- Central Intelligence Agency. 2023. División Político Administrativa y Censal 2007. The World Factbook, National Statistics Office, Washington. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/chile.

- Chapagain, P. S., Ghimire, M.;Shrestha, S. (2019). Status of natural springs in the Melamchi region of the Nepal Himalayas in the context of climate change. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 21, 263-280.

- City of Cape Town (2018). Day Zero and Water-related FAQs. https://www.westerncape.gov.za/110green/sites/green.westerncape.gov.za/files/atoms/files/Day%20Zero%20%26%20Water-Related%20FAQs.pdf.

- Cornett, J. 2008. The desert fan palm oasis. Pp. 158-184 in Stevens, L.E. and V.J. Meretsky (eds.). Aridland Springs of North America: Ecology and Conservation. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

- D’Argenio B., Pescatore T.; Scandone P., 1973, Schema geologico dell’Appenino meridionale (Campania e Lucania). Atti del convegno: Moderne vedute sulla geologia dell’Appennino, Acc. Naz. Lincei, 183, 49-72.

- de Grenade, R. and L.E. Stevens. 2020. Desert oasis springs: ecohydrology, biocultural diversity, mythology, and societal implications. Pp. 36-46 in Goldstein, M.I., DellaSala, D.A., editors. Encyclopedia of the World's Biomes 2, Elsevier. ISBN: 9780128160961.

- Demirsoy, N., Başaran, C.H., Sandalcı, S. 2018. Historical Kestanbol Hot Springs: The water that resurrects. Lokman Hekim Dergisi 8(1): 23–32.

- DiCastri, F. and Mooney, H.A. 1973. Mediterranean-Type Ecosystems: Origin and Structure. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Duman, T.Y., Çan, T., Emre, Ö., Kadirioğlu, F.T., Başarır-Baştürk, N., Kılıç, T., Arslan, S., Özalp, S., Kartal, R.F., Kalafat, D., Karakaya, F., Eroğlu-Azak, T., Özel, N.M., Ergintav, S., Akkar, S., Altınok, Y., Tekin, S., Cingöz, A., Kurt, A.İ. 2016. Seismotectonic database of Turkey. Bulletin Earthquake Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10518-016-9965-9. [CrossRef]

- Erschbamer, M. (2021). Better than any Doctor. Buddhist Perspectives on Hot Springs in Sikkim, Himalayas. Etnološka tribina: Godišnjak Hrvatskog etnološkog društva, 51(44), 54-70.

- Evenstar, L.A.; Mather, A.E.; Hartley, A.J.; Stuart, F.M.; Sparks, R.S.J.; Cooper, F.J. 2017. Geomorphology on geologic timescales: Evolution of the late Cenozoic Pacific paleosurface in Northern Chile and Southern Peru. Earth. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.04.004. [CrossRef]

- Faranda, F.M.; Letterio, G.; Spezie, G. (2001). Mediterranean Ecosystems: Structures and Processes. New York, Springer-Verlag.

- Fensham, R.J., R. Adinehvand, S. Babidge, M. Cantonati, M. Currell, L. Daniele, A. Elci, D.M.P. Galassi, Á.H. Portillo, S. Hamad, D. Han, H.A. Jawadi, J. Jotheri, B. Laffineur, A.H. Mohammad, A. N.A. Navidtalab, K. Nicoll, T. Odeh, V. Re, B. Sanjuan, V. Souza, L.E. Stevens, M. Tekere, E. Tshibalo, J. Silcock, J. Webb, B. van Wyk, M. Zamanpoore, and K.G. Villholth. 2023a. Fellowship of the Spring: An initiative to document and protect the world’s oases. Science of the Total Environment. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163936. [CrossRef]

- Fensham, R.J., W. F. Ponder, V. Souza, and L.E. Stevens. 2023b. Extraordinary concentrations of local endemism associated with arid-land springs. Frontiers in Environmental Science 11:1143378, doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.114337. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martínez M., Barquín J., Bonada N., Cantonati M., Churro C., Corbera J., Delgado C., Dulsat-Masvidal M., Garcia G., Margalef O., Pascual R., Peñuelas J., Preece C., Sabater F., Seiler H., Zamora-Marín J.M. & Romero E. 2023. Mediterranean springs: Keystone ecosystems and biodiversity refugia threatened by global change. Global Change Biology 00, e16997. [CrossRef]

- Fox MD. 1995. Australian Mediterranean vegetation: intra- and intercontinental comparisons. In Arroyo M.T.K., Zedler, P.H., Fox, M.D. (eds.). Ecology and biogeography of Mediterranean ecosystems in Chile, California, and Australia. Ecological Studies 108:137-159. New York, Springer-Verlag.

- Freitag, H. 1971. Studies in the Natural Vegetation of Afghanistan. In Plant Life of Southw West Asia, eds. P. H. Davis, P. C. Harper, and I. C. Hedge, pp. 89-106. Edinburgh: Royal Botanical Garden.

- Freitag, H. 1982. Mediterranean Characters of the Vegetation in the Hindukush Mts., and the Relationship between Sclerophyllous and Laurophyllous forests. Ecologia Mediterranea 8:381-388.

- Gasith, A. and V. H. Resh, 1999. Streams in mediterranean climate regions: abiotic influences and biotic responses to predictable seasonal events. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 31: 51–81.

- Gasith, A. and V. H. Resh. 1999. Streams in mediterranean climate regions: abiotic influences and biotic responses to predictable seasonal events. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 31:51-81.

- Geiger, R. 1954. Klassifikation der Klimate nach W. Köppen. Landolt-Börnstein – Zahlenwerte und Funktionen aus Physik, Chemie, Astronomie, Geophysik und Technik, alte Serie 3:603–607.

- Geiger, R. 1961. Überarbeitete Neuausgabe von Geiger, R.: Köppen-Geiger / Klima der Erde. (Wandkarte 1:16 Mill.). Klett-Perthes, Gotha.

- German, C. R.; Baumberger, T.; Lilley, M. D.; Lupton, J. E.; Noble, A. E.[ Saito, M. et al. (2022). Hydrothermal exploration of the southern Chile Rise: Sediment-hosted venting at the Chile Triple Junction. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 23, e2021GC010317. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GC010317. [CrossRef]

- Geva, A. (ed.) Water and Sacred Architecture. London, Routledge.

- Ghimire, M., Chapagain, P. S.; Shrestha, S. (2019). Mapping of groundwater spring potential zone using geospatial techniques in the Central Nepal Himalayas: a case example of Melamchi–Larke area. Journal of Earth System Science, 128, 1-24.

- Gleick, P.H. 2011. Bottled and Sold: The Story Behind Our Obsession with Bottled Water. Island Press, New York.

- Gleick, P.H. 2011. Bottled and sold: The Story Behind Our Obsession with Bottled Water. Island Press, New York.

- Grove, A.T. and Rackham, O. 2001. The Nature of Mediterranean Europe. An Ecological History. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hahn, K. 2016. Kese and Tellak: Cultural Framings of body treatments in the “Turkish Bath”. European Review 24(3): 462–469.

- Hancock, P.L., Chalmers, 2000. Creation and destruction of travertine monumental stone by earthquake faulting at Hierapolis, Turkey. In McGuire,W.G., Griffiths, D.R., Hancock,P.L., Stewart, I.S. (eds). The archaeology of geological catastrophes. London, Geological Society of London Special Publications 171:1-14, 1-86239-062-2/00/.

- Harris, C.C. Burgers, J. Miller, and F. Rawoot (2010). O- and H-isotope record of Cape Town rainfall from 1996 to 2008, and its application to recharge studies of Table Mountain groundwater, South Africa. South African J. Geology, 113(1), 33-56. doi:10.2113/gssajg.113.1.33. [CrossRef]

- Harry, K. and J. Watson. 2010. The Archaeology of Pueblo Grande de Nevada: Past and Current Research within Nevada's “Lost City”. Kiva 75:403-424. [CrossRef]

- Hoberg, D. 2007. Resorts of Lake County. Arcadia Press, San Francisco, California.

- Hurwitz S., 2022. One benefit of California’s volcanoes? Geothermal energy. U.S. Geological Survey California Volcano Observatory https://www.usgs.gov/observatories/calvo/news/one-benefit-californias-volcanoes-geothermal-energy (accessed 24 Nov 2023).

- Hurwitz S., 2022. One benefit of California’s volcanoes? Geothermal energy. U.S. Geological Survey California Volcano Observatory. https://www.usgs.gov/observatories/calvo/news/one-benefit-californias-volcanoes-geothermal-energy (accessed 24 Nov 2023).

- Jaco, M. 1990. Time to slow down. The History of Wilbur Hot Springs. Chrysophlae Press, San Francisco, California.

- James, P.E. 1966. A Geography of Man. Third Ed. Waltham, MA: Blaisdell.

- Jeelani, G., Lone, S. A., Lone, A.; Deshpande, R. D. (2021). Groundwater resource protection and spring restoration in Upper Jhelum Basin (UJB), western Himalayas. Groundwater for Sustainable Development, 15, 100685.

- Johnson, B.L., Richardson W.R., Naimo, T.J. 1995. Past, present, and future concepts in large river ecology. Bioscience 45:134-141.

- Johnson, R.H.; DeWitt, E.; Arnold, L.R. Using hydrogeology to identify the source of groundwater to Montezuma Well, a natural spring in Central Arizona, USA: Part 1. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 67, 1821–1835, doi:10.1007/s12665-012-1801-1.

- Kaysing, B. and R. Kaysing. 1993. Great Hot Springs of the West. Capra Press, Santa Barbara, California.

- Klages, E. 1991. Harbin Hot Springs. Healing Waters, Sacred Land. Harbin Springs Publishing, Middletown, California.

- Köppen, W.P. 1918. Klassifikation der Klimate nach Temperatur, Niederschlag, und Jahreslauf. Petermann's Geographische Mitteilungen 64:193-203, 243-248.

- Kroeber, A. L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bulletin 78 of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

- Kruger, F.J. 1985. Patterns of Vegetation and Climate in the Mediterranean Zone of South Africa. Bulletin de la Société Botanique de France 131:213-224.

- Lacopini, L.S. 2019. La Cassa per il Mezzogiorno e la politica (1950- 1986), Bari- Roma, Laterza 2019.

- Lamberti, G. A. and V. H. Resh. 1983. Geothermal effects on stream benthos: the separate influences of thermal and chemical components on periphyton and macroinvertebrates. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 40:1995-2009.

- LaVanchy, G.T., M.W. Kerwin, and J.K. Adamson (2019). Beyond ‘Day Zero’: insights and lessons from Cape Town (South Africa). Hydrogeology Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-019-01979-0. [CrossRef]

- Leach, C., Lambright, E., Becker, J., Landvatter, T., Elliott, T. 2023. Clepsydra of the Oropos Amphiareion: a Pleiades place resource. Pleiades: A Gazetteer of Past Places. <https://pleiades.stoa.org/places/234032029> (accessed: 22 December 2023).

- Leone, G., Catani, V., Pagnozzi, M., Ginolfi M., Testa, G., Esposito, L., Fiorillo, F. 2023. Hydrological features of Matese Karst Massif, focused on endorheic areas, dolines and hydroelectric exploitation, Journal of Maps, 19:1. [CrossRef]

- León-Lobos, P.; Díaz-Forestier, J.; Díaz, R.; Celis- Díaz, J.L.; Diasgranados, M.; Ulian, T. (2022). Patterns of traditional and modern uses of wild edible native plants of Chile: Challenges and future perspectives. Plants (Basel) 11:744- . doi: 10.3390/plants11060744. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.J. et al. 2023. Human perceptions of competing interests in springs ecosystem management on public land in southwestern United States. In: Groundwater for Sustainable Development 22, 100966.

- Li., L.; Casado, A.; Congedi, L.; Dell’Aquila, A.; Dubois, C.; Elizalde, A.; L’ Hévéder, B.; Lionello, P; Sevault, F.; Somot, S.; Ruti, P.; Zampieri, M. (2012). In Lionello, P. (ed.). Modeling of the Mediterranean Climate system. In (eds.). The Climate of the Mediterranean Region, pp. 419-448. London, Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P. (ed). 2012. The Climate of the Mediterranean Region: From the Past to the Future. Philadelphia, Elsevier.

- Lone, S. A., Bhat, S. U., Hamid, A., Bhat, F. A. and Kumar, A.2020. Quality assessment of springs for drinking water in the Himalaya of South Kashmir, India. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28, 2279-2300.

- Lone, S. A., Hamid, A.; Bhat, S. U. (2021). Algal community dynamics and underlying driving factors in some crenic habitats of Kashmir Himalaya. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 232, 1-14.

- Luebert, F.; Pliscoff, P. (2017). Sinopsis bioclimática y vegetacional de Chile, 2nd ed. Santiago de Chile, Editorial Universitaria. ISBN 978-956-11-2575-9.

- Luzzini, F. (2015). Il mistero e la bellezza. La Fonte Aretusa tra mito, storia e scienza. Acque Sotterranee - Italian Journal of Groundwater, 4(3), 79–80. https://doi.org/10.7343/as-127-15-0154. [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, M. F., P. Beja, I. J. Schlosser and M. G. Collares-Pereira, 2007. Effects of multi-year droughts on fish assemblages of seasonally drying Mediterranean streams. Freshwater Biology 52: 1494–1510.

- Maquet, P.A.; Tognelli, M.; Barria, I.; Escobar, M.; Garin, C; Soublette, P. (2004). How well are Mediterranean ecosystems protected in Chile? In Arianoutsou and Papanastasis (eds.). Proceedings of the 19th MEDECOS Conference, p. 1-4. Rhodes, Greece. Rotterdam, Millpress.

- Martarelli, L., Petitta, M., Scalise, A.R., Silvi, A. (2008). Experimental hydrogeological cartography of the Rieti Plain (Latium). Mem. Descr. Carta Geol. d’It. LXXXI, pp. 137-156. (https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files/pubblicazioni/periodicitecnici/memorie/memorielxxxi/mem-des-81-martarelli.pdf).

- Mays, L.W. (2014). Use of cisterns during antiquity in the Mediterranean region for water resources sustainability. Water Science & Technology: Water Supply, 14: 38-47.

- Mazor, E. and B.T. Verhagen (1983). Dissolved ions, stable and radioactive isotopes and noble gases in thermal waters of South Africa. J. Hydrol., 63, 315-329.

- Mertoğlu, O., Şimişek, Ş., Başarır, N., Paksoy, H. Geothermal Energy Use, Country update for Turkey. European Geothermal Congress-2019, Den Haag, The Netherlands. Proceeding Book: 1–10 pp.

- Mueller JM, Lima RE, Springer AE. 2017. Can environmental attributes influence protected area designation? A case study valuing preferences for springs in Grand Canyon National Park. Pp. 196-205 in Land Use Policy 63.

- Meusel, H. 1971. Mediterranean Elements in the Flora and Vegetation of the West Himalayas. In Plant Life of South West Asia, eds. P. H. Davis, P. C. Harper, and I. C. Hedge, pp. 53-72. Edinburgh: Royal Botanical Society.

- Mitrakos, K. 1980. A Theory for Mediterranean Plant Life. Oecologia Plantarum 1:245-252.

- Monteleone, M.C., Yeung, H.; Smith, R. (2007). A review of Ancient Roman water supply exploring techniques of pressure reduction. Water Science & Technology: Water Supply, 7 (1): 113–120.

- Mooney, H.A., Dunn, E.L., Shropshire F., Song, L. 1970. Vegetation comparisons between the Mediterranean climatic areas of California and Chile. Flora 159:480-496.

- Nabhan, G.P. 2008. Plant diversity influenced by indigenous management: Quitobaquito and Quitovac Springs. Pp. __ in Stevens, L.E. and V.J. Meretsky, eds. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

- Nabhan, G.P., L.M. Eiler, R.R. Johnson, A. Rea, E. Mellink, and L.E. Stevens. 2023. The making and unmaking of an indiginous desert oasis and its avifanua : Historic declines in Quitobaquito birds as a result of shifts from O’odham stewardship to federal agency management. Pp. 332-351 in Hoagland S.J. and S. Albert, editors. Wildlife Stewardship on Tribal Lands. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- Nowreen, S., Misra, A. K., Zzaman, R. U., Sharma, L. P.; Abdullah, M. S. (2023). Sustainability Challenges to Springshed Water Management in India and Bangladesh: A Bird’s Eye View. Sustainability, 15(6), 5065.

- Olivier, J. and N. Jonker (2013). Optimal utilisation of thermal springs in South Africa. Water Research Commission. WRC Report No. TT 577/13, November 2013. ISBN 978-1-4312-0481-6. reclaim.camissa.org. Water – our Heritage and our Future. Accessed 2023.12.11. http://www.reclaimcamissa.org/blog.

- Pascual, R., G. Gomá, S. Nebra, C.P. Rius. 2020. First data on the biological richness of Mediterranean springs. Limnetica 39:121-139. [CrossRef]

- Pires, A. M., I. G. Cowx and M. M. Coelho, 2000. Benthic macroinvertebrate communities of intermittent streams in the middle reaches of the Guadiana Basin (Portugal). Hydrobiologia 435: 167–175.

- Piscopo, D., Gattiglio, M., Sacchi, E.; Destefanis, E. (2009). Tectonically-related fluid circulation in the San Casciano dei Bagni-Sarteano area (M. Cetona ridge-Southern Tuscany): a coupled structural and geochemical investigation. Italian Journal of Geosciences 128, n°2, 575-586. [CrossRef]

- Pliny the Elder. ca. AD 77 in Bostock J, Riley HT (1855). Pliny the Elder, The Natural History. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street, London.

- Polto, C. (2001). La Fontana Aretusa tra mito e realtà. In C. Masetti (Ed.), Chiare, fresche e dolci acque. Le sorgenti nell’esperienza odeporica e nella storia del territorio (pp. 11–25). Rome: CISGE.

- Power, M. E., J. Holomuzki and R. L. Lowe, 2012. Food webs in mediterranean rivers. Hydrobiologia 19:119–136.

- PRISM. 2014. PRISM. PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University, Corvallis. https://prism.oregonstate.edu.

- Rea, A.M. 2008. Historic and Prehistoric Ethnobiology of Desert Springs in Aridland springs in North America : ecology and conservation. Pp. ___ in Stevens, L.E. and V.J. Meretsky, eds. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

- Reiche, K. 1907. VIII. Grundzϋge der Pflanzenverbreitung in Chile. In Engler, A., und Drude, O. (eds.). 1907. Die Vegetation der Erde. Leipzig, Wilhelm Englemann.

- Resh, V. H. and M. A. Barnby. 1987. Distribution of the Wilbur Springs Shore Bug (Hemiptera: Saldidae): a product of abiotic tolerances and biotic constraints. Environmental Entomology16:1087-1091.

- Resh, V. H., Lamberti, G. A., McElravy, E. P., Wood, J. R., and Feminella, J. W. 1984. Quantitative methods for evaluating the effects of geothermal energy development on stream benthic communities at The Geysers, California. California Water Resources Technical Publication No. 190.

- Resh, V.H., L.A. Bêche, J.E. Lawrence, R.D. Mazor, E.P. McElravy, A.H. Purcell, and S.M. Carlson. 2013. Long-term population and community patterns of benthic macroinvertebrates and fishes in northern California Mediterranean-climate streams". Journal of the North American Benthological Society. 719: 93–118.

- RLA Growth. 2019. Hot springs emerge as hot market for investments. RLA Global, Budpest. https://rlaglobal.com/en/insights/hot-springs-emerge-as-hot-market-for-investments.

- Robinson, BA. 2011. Histories of Pierene: A Corinthian fountain in three millenia. American School of Classical Studies, Athens.

- Royte, E. 2008. Bottlemania. How Water Went on Sale and Why We Bought It. Bloomsbury USA. New York.

- Rybus, G. (in press). Hot Springs: Photos and Stories of How the World Soaks, Swims, and Slows Down, Berkeley, Ten Speed Press.

- Sada, D.W., Cooper, D.J. 2012. Furnace Creek Springs restoration and adaptive management plan. Death Valley National Park, California. https://sites.warnercnr.colostate.edu/davidcooper/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2017/02/FCSprings_Restoration_Final-pdf.pdf.

- Scott C.A., Zhang F., Mukherji A., Immerzeel W., Mustafa D., Bharati L. 2019. Water in the Hindu Kush Himalaya. In: Wester P., Mishra A., Mukherji A., Shrestha A. (eds) The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_8/. [CrossRef]

- Sergi, G. 1901. The Mediterranean race: a study of the origin of European peoples. Pp. 1-20 in Ellis, H. (ed) The Contemporary Science Series. London, Walter Scott.

- Sharma, B., Nepal, S., Gyawali, D., Pokharel, G. S., Wahid, S., Mukherji, A.; Shrestha, A. B. (2016). Springs, storage towers, and water conservation in the midhills of Nepal. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development.

- Shmida, A. 1981. Mediterranean vegetation in California and Israel: similarities and differences. Israel Journal of Botany 30:105-123.

- Solomon S. 2010. Water: The epic struggle for wealth, power, and civilization. New York, Harper.

- Solomon, S. 2011. Water: The Epic Struggle for Wealth, Power, and Civilization. Harper Perennial, New York.

- southafrica.to. Caledon Hotel & Spa Review. Accessed 2023.12.11. https://www.southafrica.to/accommodation/Caledon/Caledon-Hotel/Caledon-Hotel-Spa.php.

- Specht, R.L. 1969. A Comparison of the Sclerophyllous Vegetation Characteristic of Mediterranean Type Climates in France, California, and Southern Australia. I. Structure, Morphology, and Succession. Australian Journal of Botany 17:277-292.

- Specht, R.L. 1988. Mediterranean-type Ecosystems: A Data Source Book. Dordrecht: Kluwer Associates.

- Stevens, L.E., J. Jenness, and J.D. Ledbetter. 2020. Springs and springs-dependent taxa in the Colorado River Basin, southwestern North America: geography, ecology, and human impacts. Water 12, 1501; doi:10.3390/w12051501.

- Strauch, D. 1936. Satan came to Eden: A survivor’s account of the “Galapagos Affair”. Harper, New York.

- Suc, J.P. 1984. Origin and Evolution of the Mediterranean Vegetation and Climate in Europe. Nature 307:429-432.

- Tabar, E., Yakut, H. 2014. Radon measurements in water samples from the thermal springs of Yalova basin, Turkey. J Radional Nucl Chem 299: 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-013-2845-8. [CrossRef]

- The Water Wheel (2010). Cape Town – Water for a thirsty city (Part 1). November/December 2010.

- The Water Wheel (2011). Cape Town – Water for a thirsty city (Part 2). January/February 2011.

- thebaths.co.za. Natural Hot springs. “Hot and cold pools”. Accessed 2023.12.11. https://thebaths.co.za/natural-hot-springs/.

- Thieberger, N. 1993. Handbook of western Australian Aboriginal languages south of the Kimberley Region. Pacific Linguistics, Series C – 124. The Australian National University. [CrossRef]

- Tindale, N.B. (1981) Desert Aborigines and the southern coastal peoples: some comparisons, MS (cited in Thieberger 1993).

- Tindale, N.B. 1974. Aboriginal tribes of Australia: their terrain, environmental controls, distribution, limits, and proper names, Australian National University Press, Canberra.

- Trewartha, G. 1961. The Earth's Problem Climates. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

- Trueman M, d’Ozouville N. 2010. Characterizing the Galapagos terrestrial climate in the face of global climate change. Galapagos Research 67:25-37.

- Tuccimei, P., Castelluccio, M., De Simone, G., Giglioni, F., Lucchetti, C., Placidi, M., Prisco, F., Ursino, V. (2014). Indagini geochimiche nell’acquedotto Vergine antico. Archeologia Sotterranea, n°10, 15-22. https://www.romanoimpero.com/2019/10/acquedotto-cornelio-di-termini-imerese.html.

- Tuluk, B., Cengiz, Ö. 2017. Evaluation on bottled natural mineral water. Turkish Journal of Occupational/Environmental Medicine and Safety 2: 30–38.

- Üreten, H. 2006. Hierapolis (Pamukkale) ve Laodiceia (Goncalı-Eskihisar) Kentlerinde Tanrı Krallar: Attoloslar. Uluslararası Denizli ve Çevresi Tarih ve Kültür Sempozyumu Bildiriler Kitabı: 105–114 syf.

- van Wyk, D. (2013). The social history of three Western Cape thermal mineral springs resorts and their influence on the development of the health and wellness tourism industry in South Africa. Thesis. Stellenbosch University.

- Verma, R.; Jamwal, P. (2022). Sustenance of Himalayan springs in an emerging water crisis. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 194(2), 87.

- Walter, H., Harnickell, E., and Mueller-Dombois, D. 1975. Climate-diagram Maps of the Individual Continents and the Ecological Climatic Regions of the Earth. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Waring, G. A. 1916. Springs of California. U. S. Geological Survey Water Supply Paper 338. Wahington D. C.

- Weiner, J. (1995). The Beak of the Finch: A Story of Evolution in Our Time. New York, Vintage Press.

- Weiner, J. 1995. The beak of the finch. Vintage Books, New York.

- Western Cape Government (2023). Economic Water Resilience. Accessed 2023.12.11. https://www.westerncape.gov.za/110green/economic-water-resilience#:~:text=Water%20consumption%20in%20Cape%20Town,normal'%20to%20become%20water%20resilient.

- White, D. E., I. Barnes, and J. R. O’Neill. 1973. Thermal and mineral waters of nonmetric origin, California Coast Ranges. Geological Society of America Bulletin 84:547-560.

- Williamson, D. (2023). Tower and temple: Re-sacralizing water infrastructure at Balkrisha Doshi’s GSFC Township. In Geva, A. (ed.) Water and Sacred Architecture. London, Routledge, pp. 199-214.

- Willmore, S. (2015). Table Mountain springs are new tourism draw. Accessed 2023.12.11. https://medium.com/bgtw/table-mountain-springs-are-new-tourism-draw-6487e7ee76ed.

- Winograd, I.; Thordarson, W. 1975. Hydrogeologic and hydrochemical framework, south-central Great Basin, Nevada-California, with special reference to the Nevada Test Site. Prof. Paper 1975, 712, doi:10.3133/pp712c. [CrossRef]

- Wittmer M. 1989. Floreana: A woman’s pilgrimage to the Galapagos. Moyer Bell, New York.

- Xanke, J., Goldscheider, N., Bakalowicz, M., Barbará, J.A., Broda, S., Chen, Z., Ghanmi, M., Günther, A., Hartmann, A., Jourde, H., Liesch, T., Mudarra, M., Petitta, M., Ravbar, N., Stepanovic, Z. 2022. Mediterranean Karst Aquifer Map (MEDKAM), 1 : 5,000,000. Berlin, Karlsruhe, Paris. doi: 10.25928/MEDKAM.1. [CrossRef]

- Young, S. 1998. Beautiful Spas and Hot Springs of California. Ramcoast Books, Vancouver, British Columbia.

- Zribi, M.; Brocca, L.; Tramblay, Y.; Molle, F. 2020. Water Resources in the Mediterranean Region. Philadelphia, Elsevier.

- Σουέρεφ, Κ. (2000). Υδάτινες σχέσεις, το νερό ως πηγή ζωής κατά την αρχαιότητα. Θεσσαλονίκη: University Studio Press.

| Village/hamlet* | Informant | Age | Main profession | Number of springs cited** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albarca | Several (11) reported in Palomar (2008) | --- | --- | 20 |

| Cabassers | Ramon Masip | 69 | farmer | 23 |

| Cornudella de Montsant | Ildefons Gomis | 90 | farmer | 72 |

| Escaladei | Benito Porqueres | 84 | farmer | 13 |

| la Bisbal de Falset | Miquel Franquet | 83 | farmer | 22 |

| la Figuera | Jaume Roca | 78 | farmer | 17 |

| la Morera de Montsant | Joaquim Figueres | 65 | farmer | 48 |

| Ramon Sabaté | 79 | farmer | ||

| la Vilella Alta | Josep Maria Masip | 65 | farmer | 37 |

| la Vilella Baixa | Eduard Juncosa | 66 | farmer | 28 |

| Margalef | Miquel Amill | 69 | farmer | 28 |

| Poboleda | Salvador Burgos | 52 | farmer | 14 |

| Torroja del Priorat | Joan Pàmies | 70 | farmer & shepherd | 59 |

| Ulldemolins | Ramon Pere | 59 | farmer | 41 |

| * The springs cited by each informant are not circumscribed exactly to the municipal district, but to the territory best known to the local population, which may include other municipalities and/or exclude part of their own. In the cases of Albarca and Escaladei, it applies to the old districts, which have been integrated into the contemporary municipalities of Cornudella de Montsant and la Morera de Montsant, respectively. | ||||

| ** The number is approximate, since in some cases the number of existing springs in a given area could not be remembered precisely and, on the other hand, some informants only mention the most important ones. | ||||

| Spring | Date | Calendar of saints | Village that organizes the event | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Llúcia | 2nd Sunday in August* | --- | la Bisbal de Falset | |

| La Foia | April 25 | Sant Marc | Cabassers | |

| August 5 | Mare de Déu de les Neus | Cabassers | ||

| Sant Salvador | April 25 | Sant Marc | Margalef | |

| August 6 | Sant Salvador | Margalef | ||

| August 16 | Sant Roc | la Bisbal de Falset | ||

| * Santa Llúcia (Saint Lucy) is on December 15, a date when it is usually very cold. It is for this reason that the celebration takes place in August. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).