Introduction

One of the main challenges of the globalization became the increased destabilization and frequent economic crises. In general, managing an economic crisis is a particularly difficult task for any economy (developed or developing, and regardless the size). In the context of globalization, the process faces additional challenges. On the one hand, the world economy witnessed a shift from traditional purely economic instruments to more financial mechanisms of economic development. Indeed, the liberalization of the economy since the 1990s complicated the traditional trends of the world market development, resulting in significant fluctuation of the growth rates between different countries and regions. To respond to this evolution, governments and international organizations changed well-established strategies. For example, financial sector found itself given expanded role in economic development, with, different financial mechanisms used as key variables to evaluate an economic growth. On the other hand, the increased role of financial sector in a globilised world, increased financial relations among individual states and thus, interdependences. This “financial globalization” causes important fluctuations in the system and, as a result, causes instability in socio-economic development. Thus, an economic crisis of any important economy soon becomes a global issue (financial crisis of 2008, economic crisis of 2020).

The recent global economic crisis due to the Covid-19 world pandemic, appeared to be unique for several reasons. First, it highlighted the transnational and origin-specific nature of the crisis. Second, it appeared to be the first case when non-economic factors caused a major economic crisis. As a result, this crisis turned out to be particularly difficult to predict and to manage. In this case, the main strategy of the global post-crisis rehabilitation became the restoration of the economy’s predictability and ensuring its ability to obey the classical principles. According to the Organic Law on “Economic Freedom” of the European Union (2011), any factor which increases the equilibrium amount of output is reflected in the economic rehabilitation plan. Such exogenous factors are primarily fiscal mechanisms, i.e. - Reduction of taxes and increase of state expenditures.

This crisis caused important structural problems with their effects on public expenditures (especially health expenditures, to the public expenditures, economic growth, price stability and budget balance) in both, developed and developing countries. Nearly every state declared an increase in public debt, inflation, and unemployment rates, while an important decrease was shown in growth rates and capital outflows. As the crisis due to the world pandemic was radically different from previous economic crises, it was difficult to manage it efficiently at the initial stage. It was complicated to forecast the scenarios of the unknown crisis with non-standard nature which was more linked to epidemiologic factors than objective economic law. The dynamics of crisis resolution depended on correct forecasting and effective implementation of global, but especially country-based reforms. More importantly, this crisis showed the important role of individual states to manage the global crisis.

The traditional function of a government to ensure country’s socio-economic growth and security, increases in an extraordinary environment, such as sharp economic fluctuations and crises. In such contexts, the centralized management functions are sharply activated. The global pandemic processes have updated the economic essence of the state. The large scale of the latest economic crisis due to the world pandemic has determined the need for mutually coordinated development of anti-crisis plans of different countries.

In today’s dynamic landscape, modern global systems are redefining the standards and priorities of national economic policies. The economic status of countries is changing significantly as a result of their participation in these systems. As a result of these changes, today’s global economy is marked by the proliferation of regionalism and the emergence of spatial economic frameworks. Thus, classical economic concepts are evolving, giving rise to a new model known as economic nationalism. This paradigm shift is generating new risks, which are increasing in severity and scope. The overriding objective of economic policy is now to ensure and predict stable development. Reflections are underway to meet the challenges of economic equilibrium and its social and institutional sustainability.

In addition to the decentralization of the unified governance system, the global economy is characterized by the activation of centralized governance elements within individual countries. This requires the development of new norms for global cooperation and the careful balancing of national integration and development factors. The question of government’s influence on the economy and the delegation of its powers becomes relevant once again. Effective coordination of public administration is based on the principle of decentralized government, which is a key element of a democratic model of society and facilitates the transfer of management tools to the public. The key objectives of this research are focused on the optimal distribution of state functions and the study of hierarchical principles of territorial organization within the country, fiscal mechanisms for the distribution of powers, as well as the particularities of the structuring of the spatial economy and its budgetary provisioning mechanisms.

The example of the last two economic crisis showed that contemporary anti-crisis strategies should reflect several considerations. First, it becomes impossible to develop a single unified model of crisis management. Even in the context of important economic and financial globalization, the current decentralization and new spatial economic processes make it necessary to find a balance between the local priorities and global interests. Second, the role of non-economic crisis-causing factors increases compared to economic determinants. That is why international and country-based reforms should aim at not only economic rehabilitation, but also on the social, cultural and environmental restorations. Third, it becomes difficult to correctly predict the consequences of the crisis and thus, the effects of the anti-crisis strategy. Consequently, the success of the post-crisis rehabilitation of the countries’ economies depends significantly not only on the effective realization of their own plan, but also, in general, on the specificities of the global economy and on the ability of the world markets to overcome the negative consequences of a crisis.

In this context, the development of complex post-crisis platforms and state post-crisis strategies is the priority. The most effective component in the anti-crisis strategy is the monetary instruments of economic management. As for the determinant of successful functioning of economy, the priority should be given to the regulation of exchange rate, interest rate and inflationary processes. A state anti-crisis programs should reflect the crisis prevention strategy, which, on its turn, should differentiate the economic functions of the state and crisis management mechanisms according to the specific trends of given processes. It should aim at gaining stable development of the economy. Additionally, an anti-crisis plan should reflect the role of the society in the development process and its mental changes under crisis conditions. The state should be responsible for establishing and monitoring anti-crisis management mechanisms, financial recovery of the country and formation of correct relations. It is especially important to ensure economic security, to stabilize the development process and standard of living, to support the private sector and small entrepreneurship, to increase economic freedom, to ensure effective distribution of labor and capital, and others. All strategies of the anti-crisis platform should be focused on social results, as it should contribute to a fair distribution of income and to poverty reduction.

Chapter 1. Program of Economic Rehabilitation During a Post-crisis Period

The contemporary world is marked with a deglobalisation process which changes inter-state relations and the role of economic policies in crisis management. The recent economic crisis, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, has stressed further the unstable nature of integrated economic systems (Immordino, Oliviero & Zazzaro, 2022; Valinurova et al., 2021; Dinkin & Telegina, 2020).

The current pandemic crisis appeared to be different from previous experiences in number of ways. First, it highlighted its transnational and origin-specific nature. Second, it was the first case when non-economic factors caused an economic crisis. Third, and due to the above-mentioned reasons, it turned to be particularly difficult to predict. In such situation, crisis management imposed the provision of a continuous chain of global information transmission and the need for interstate coordination of relevant governance structures (Kravchenko et al., 2021; Shatnaw, 2021).

This crisis also intensified the issue of rational management of the economy and structural transformations. Among the existing problems, three important issues were highlighted: conducting an independent monetary policy, ensuring capital mobility with open financial accounts, and exchange rate stability. According to the Organic Law on “Economic Freedom” of the European Union (2011), any factor which increases the equilibrium amount of output is reflected in the economic rehabilitation plan. Such exogenous factors are primarily fiscal mechanisms, i.e. - Reduction of taxes and increase of state expenditures. This crisis caused important structural problems with their effects on public expenditures (especially health expenditures, to the public expenditures, economic growth, price stability and budget balance) in both, developed and developing countries. Nearly every state declared an increase in public debt, inflation and unemployment rates, while an important decrease was shown in growth rates and capital outflows (Canakci & Arslan, 2021).

The current pandemic crisis has shown the need for correct coordination of global economic systems and optimal distribution of functions between individual levels of socio-economic systems (Immordino, Oliviero & Zazzaro, 2022; Matuszak et al., 2022; Tabatadze, 2022). At the same time, it made clear the role of governments in maintaining or achieving the country’s political and economic stability. Finally, the recent crisis, due to its non-standard and hardly predictable nature, highlighted the need for its individual but closely coordinated management (Tabatadze, 2022).

The theoreticians of economic crisis management argue that one of the main goals of crisis management is to ensure economic stability. This requires early identification of systemic risks, studying risk factors and determining the appropriate management strategy (Tabatadze & Tsanava, 2009). The state role in this process is crucial as made clear throughout the different economic crises of the 20th century (Eihak & Mitra, 2009). In an increasing globalisation, managing these crises required an optimal functioning of governments in the global environment, development of unified standards of economic management, mutual coordination of states’ independent anti-crisis policies and correct forecasting of economic development trends (Angosto-Fernández & Ferrández-Serrano, 2022; Dinkin & Telegina, 2020; Abbe, 2019; Tabatadze, 2016).

The findings of this boon contribute to the scientific literature in number of ways. They show that the rates of economic recovery are different depending on the severity of the crisis itself, but also on the severity of economic fluctuations and the range of declines within different country. The recovery rate also varies according to the specifics of countries economic structures, the effectiveness of economic support policies and other factors. Despite the unified crisis management strategy after the world pandemic, the difference in its economic results can be explained by the different level of development of countries and the heterogeneous social responsibility of different societies. The findings also show that in the post-crisis period the search for the economic growth gives place to balancing of the economy and to diminishing the negative effects of the crisis (Dinkin & Telegina, 2020). Another contribution is a suggestion of economic rehabilitation framework after economic crisis. We argue that the post-crisis rehabilitation programs of individual countries need to be elaborated individually, but withing a close collaboration. As for the developing countries, the findings suggest that a crisis environment, can be used as a helping hand, to review the priorities of country’s economic and fiscal policies and, ultimately, changing the country’s positioning into the world marketplace.

Chapter 2. The Role of Government in Economic Development

When it comes to a crisis management, the main goals of state regulation can be grouped into two sets: to prevent risk development and to develop a right anti-crisis policy and harmonise it with global requirements. This implies the determination of stabilisation policy of national economies and an inclusive growth (Valinurova et al., 2021). The level of influence of the government on the economy is different per country, based on their economic development level on number of other macroeconomic elements, such as the constitutional arrangement of the country, the level of decentralisation, the socio-economic functions of the government and the degree of delegation of its powers (Angosto-Fernández & Ferrández-Serrano, 2022; Durcova, 2021; Abbe, 2019; Tabatadze, 2016). Number of studies of the effects of the financial crisis on European economies clearly

Demonstrate a substantial differentiation across the region. These studies claim that economies with lower inflation, smaller current account deficits, and lower dependence on bank-related capital inflows have been impacted less and/or dealt better with the effects of crisis (Eihak & Mitra, 2009).

The economy of developed countries bases the growth of its potential on the latest scientific and technical researches, implementation of extensive investment and innovative projects, and investment in capital production technologies. Therefore, the economy of these countries is relatively stable in relation to external factors and changes in global markets (Adomnicai, 2019; Eihak & Mitra, 2009). Developing countries face different picture. Due to lack of resources, they become dependent on the most powerful economies, which create new variations of interstate relations and offers completely new standards of cooperation to the society (Angosto-Fernández & Ferrández-Serrano, 2022; Durcova, 2021; Çanakci & Arslan, 2021; Alalawneh, 2020).

The followers of modern liberal ideology, contrary to the Keynesian school, fundamentally reject the need for substantial state intervention in the economy. According to them, centralized governance has a corrective effect on supply and demand, thus can change real information about the market. Some recent studies have demonstrated that the distortion and the central bank’s limited concern for financial stability led to the appointment of a liberal central banker, and as a result an increase in the turnover rate implied a higher degree of liberalism for low learning gains (André & Dai, 2023).

Frederic Hayek believed that the intervention of the state in the economy could cause a crisis, out of which the only way was through market mechanisms. As mentioned by Levina, “any intervention of the state in the game of spontaneous forces is a step towards totalitarianism” (Levina, 2002).

A significant transformation of state functions takes place in a crisis environment, as the crisis shakes the principles of the gradualist concept of the post-industrial society and causes deformations of existing macroeconomic balance (Tabatadze & Tsanava, 2009). The recent global economic fluctuations and a clearly expressed cyclical nature of development, required significant changes in the neoclassical principles and activated Keynesian approaches to the economic essence of the state (Durcova, 2021; Çanakci & Arslan, 2021). Its regulatory function has significantly increased in the process of risk prevention and development of a complex anti-crisis strategy. As the environmental, social and governance components of a sustainable economy have a significant impact on systemic risks, their regulation required an active involvement of the state and the use of relevant tools.

Chapter 3. Theoretical Foundations of Crisis Management

The unipolar system of governance is losing its power in the modern economic world to the decentralized relationships. As a result, new elements of economic nationalism are being formed (Tabatadze, 2020). The contemporary process of deglobalisation has been particularly emphasized by the pandemic crisis, which has stressed further the unstable nature of integrated economic systems (Valinurova et al., 2021; Dinkin & Telegina, 2020). Along with the dependence of countries on the world markets, the importance of their autonomous functioning and neighbourhood policy has increased. The increase of countries’ dependence on external shocks has increased the role of the economic and political activity of the government and the importance of the functioning of the centralized management system (Tabatadze, 2016).

The theoretical foundations of crisis management and, in general, economic regulation, are undergoing significant adjustments. Classical standards are transformed and, in some cases, completely rejected (Tabatadze, 2022). Theorists actively discuss the relevance and possibilities to implement independent crisis management mechanisms at different stages of crisis (Tabatadze & Tsanava, 2009). It is also argued whether a large-scale functional load for monetarism is rationally justified, or how correctly the direct connection between the money supply and the price index is defined (Durcova, 2021). Paul Krugman (2021) believes that “the doctrine that the supply of money rules everything has never been supported by evidence”. According to Jerome Powell, there was a very strong correlation between monetary aggregates and inflation or economic growth when this relationship was first analysed. However, economy and monetary system have changed since, breaking the correlation between the money supply and economic growth (Chugunov, et al., 2021). Neoclassicists (Branson, Drobny, Rogoff) believe that inflation depends on the money supply only in closed economies or during strong exogenous factors, such as pandemics and wars.

Some argue that financial stability is a public good that sovereign debt shocks can weaken it in its unstable aspects. Active monetary policies incentivize fiscal discipline by reducing the cost of balance consolidation (Canofari, Bartolomeo & Messori, 2023).

The basis of Friedman’s monetarism is called into question – is there a need for the permanence of money circulation? The linear relationship between inflation and money supply is thus broken. It is argued that the change in the money supply does not momentarily affect inflation, and the transmission mechanisms are not linear (Levina, 2002). Since the 80s, the increase in the money supply, contrary to the opinion of monetarists, was accompanied by a decrease in inflation (Chugunov et al., 2021). Friedman explained this irregularity by the fact that due to the reduction of the interest rate, the price of money on hand also decreased. Indeed, the financial markets were characterized by such irregular process during the first year of pandemic crisis.

When it comes to the role of policy in crisis, management, scholars disagree on the optimal solution. Some argue that monetary policy-based stabilisation policies are more effective in ensuring macroeconomic stability. Others, consider that fiscal policy instruments have a higher control power than monetary policy instruments (Cevik, Dibooglu, & Kutan, 2014). Yet others put forward the help of coordinating between monetary and fiscal policymakers (Tetik & Yıldırım, 2021; Jawadi et al., 2016).

Crisis management is based on different standards depending on the extent of integration of countries into global systems and on their level of development. Developed countries, due to their strong economic potential, are relatively resistant to changes in world markets, while poor countries, due to their dependence on powerful countries, act as consumers in the world systems (Tabatadze, 2022; Valinurova et al., 2021; Shatnawi, 2021, Abbes, 2019; Adomnicai, 2019). Analysing the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on financial markets, Angosto-Fernández & Ferrández-Serrano (2022) argue that regardless a similar negative impact of the pandemic on the global stock market, significant differences can be noted among countries, with least developed economies being the most impacted. Indeed, the stability of developing economy is very sensitive to external shocks and global transformation processes (Canofari, Bartolomeo & Messori, 2023). This sets new standards for interstate relations and offers completely different forms of cooperation to society. Countries are positioning themselves in a new way in the global system and the economic status of their participation in this system is changing. More than the stability of its economic system, a developed society is characterized by the important role of the state in risk prevention (Adomnicai, 2019). Studies demonstrate that the government income support instruments are important determinants of mistrust in institutions for the management of an economic crisis in developed economies (Immordino, Oliviero & Zazzaro, 2022).

The regulatory function of the government increases significantly in the process of developing a complex anti-crisis strategy and managing crises both in its active and post-crisis rehabilitation stages. A large scale of the modern crises made it necessary to cooperate between state authorities and even between the academic researchers. This includes joint research, common actions and mutually coordinated, complex development of anti-crisis strategies. Some authors argue that “determining the anti-crisis strategy is a process of predicting the crisis and overcoming it by respecting the goals of each participant and an objective trend of their development. (Tabatadze, 2016, p. 480). In the anti-crisis program, the state’s economic functions and crisis management mechanisms should be transformed based on the specificities of the current processes and the requirements for economic stabilisation (Shatnawi, 2021). Scholars also highlight the need of a formula-based method of fund allocation which considers the social and economic impact of crisis at a local level (Matuszak et al., 2022). Additionally, the anti-crisis plan should reflect the role of the society in the development process and its mental changes under crisis conditions (Tabatadze, 2022).

Chapter 4. Crisis Management in Developing Economies

Despite the global nature of the pandemic, countries develop individual approaches which increases the area of economic influence of the standard products of globalisation (oil, gas, wheat). The role of energy monopoly countries in world processes increases, increasing the degree of dependence of the rest of the world on them. These processes undermine the classical principles of convergence and demanded its transformation (Kravchenko, 2021). These changes also affected the unified pandemic crisis management systems.

Post-crisis stabilisation in developed countries is possible with rational use of resources and flexible currency policy. Low-income developing countries, especially due to the substantially increased debt after the recent pandemic crisis, have extremely little chance of independent manoeuvring on a global scale (Abbes, 2019). Thus, financial assistance from the international community through grants, concessional loans and debt relief becomes vital for such countries (Kavvadi, 2020, p.50).

The policy of structural transformation of the economy (mainly, the transition to import-substituting industries and energy-saving technologies) puts new, enhanced demands on the qualifications of the workforce and management skills (Kravchenko, 2021). It is necessary to improve the business environment, which requires activation of the economic function of the state and good coordination of the “state-business” relation as it has been demonstrated by number of empirical studies. ( Shatnawi, 2021). This primarily concerns the protection of property rights, reducing tax pressure and ensuring fair competition. It is also important to develop effective investment projects and actively cooperate with investors, stabilise financial markets, and ensure free movement of capital (Valinurova et al., 2021; Kravchenko, 2021; Alalawneh, 2020).

Chapter 5. Empirical Evidence of Crisis Management after the COVID-19 World Pandemic

At the first stage of the crisis, restrictions were defined as the main mechanisms to cope with the effects of the crisis. Generally speaking, severe restrictions hampered economic activity and prolonged the rehabilitation period. Studies have shown that countries with severe restrictions and, therefore, high restrictions index, experienced a sharp decline in GDP, driven by lower consumption (Kavvadi, 2022; Çanakci & Arslan, 2021; Shatnawi, 2021). During the recent pandemic crisis, the magnitude of the fall in GDP was relatively small (2-6%) in countries with severe restrictions (with an index of 55-65) and the economic decline was 12-20%. This classical standard of correlation between the severity of restrictions and economic activity was broken only in China, where, despite the strictest restrictions, the economy’s decline was equal to the world average. The

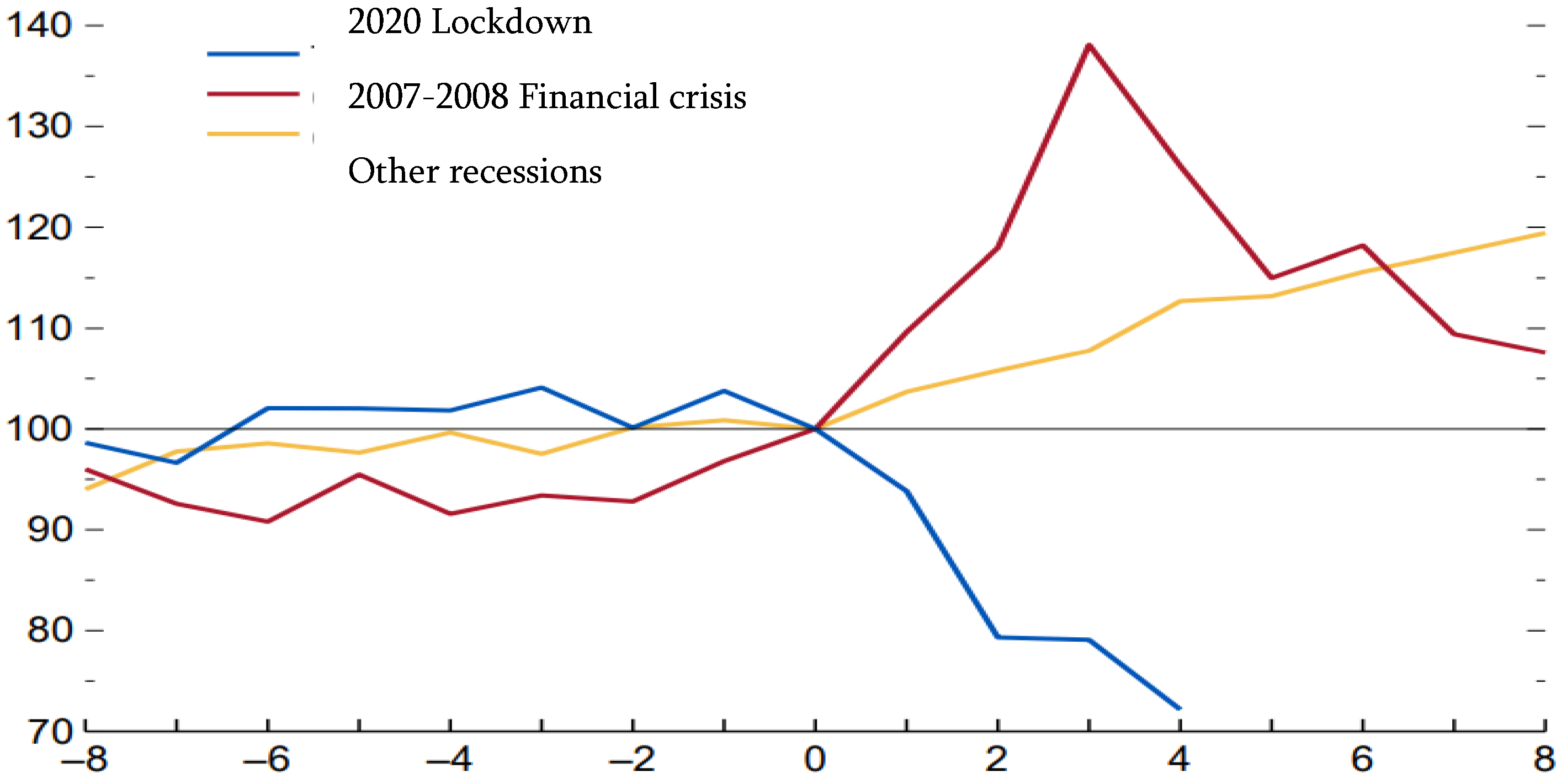

Figure 1 presents the results of the restriction strategy on different elements of economy using a normalized coefficient. It compares the results with and without the control of Covid-19 cases.

The positive economic processes of 2021 brought significant changes to the global anti-crisis strategy and required its divergence. The process of crisis management from atypical forms has, to some extent, returned to its classical methods. At the initial stage, the completely unpredictable process acquired the standard signs of a crisis: particular aggravation of the debt crisis, increase in budget costs, stagflation process, structural changes in commodity markets. As a result, the management was carried out according to established standards from 2021.

Transition to a self-sufficient economy was named as the main strategy of economic development. The post-crisis rehabilitation process was significantly influenced by the strategy of structural transformation of the economy, for which the European Union allocated one trillion Euro in 2021. The following were identified as priority industries: energy and climate-saving directions, the so-called “smart” industries and the digital markets.

With the increase of systemic risks, special importance was given to the optimisation of sectoral changes from 2022. Accordingly, to the state support policy. It was adapted to the general situation of the specific period and focused on the realisation of medium-term goals of economic stabilisation. In order to regulate the crisis in the European Union, free funds were accumulated on a large scale. For example, the contribution of the European Central Bank in providing the economy with liquid funds was particularly high. However, problematically, the movement of financial capital did not change. As a result of this mismanagement, the fundamental rules of securities acquisition and lending before the pandemic did not change. Because of this the accumulated funds were mainly used to increase the value of securities on the stock markets, instead of serving the medical sector as a whole.

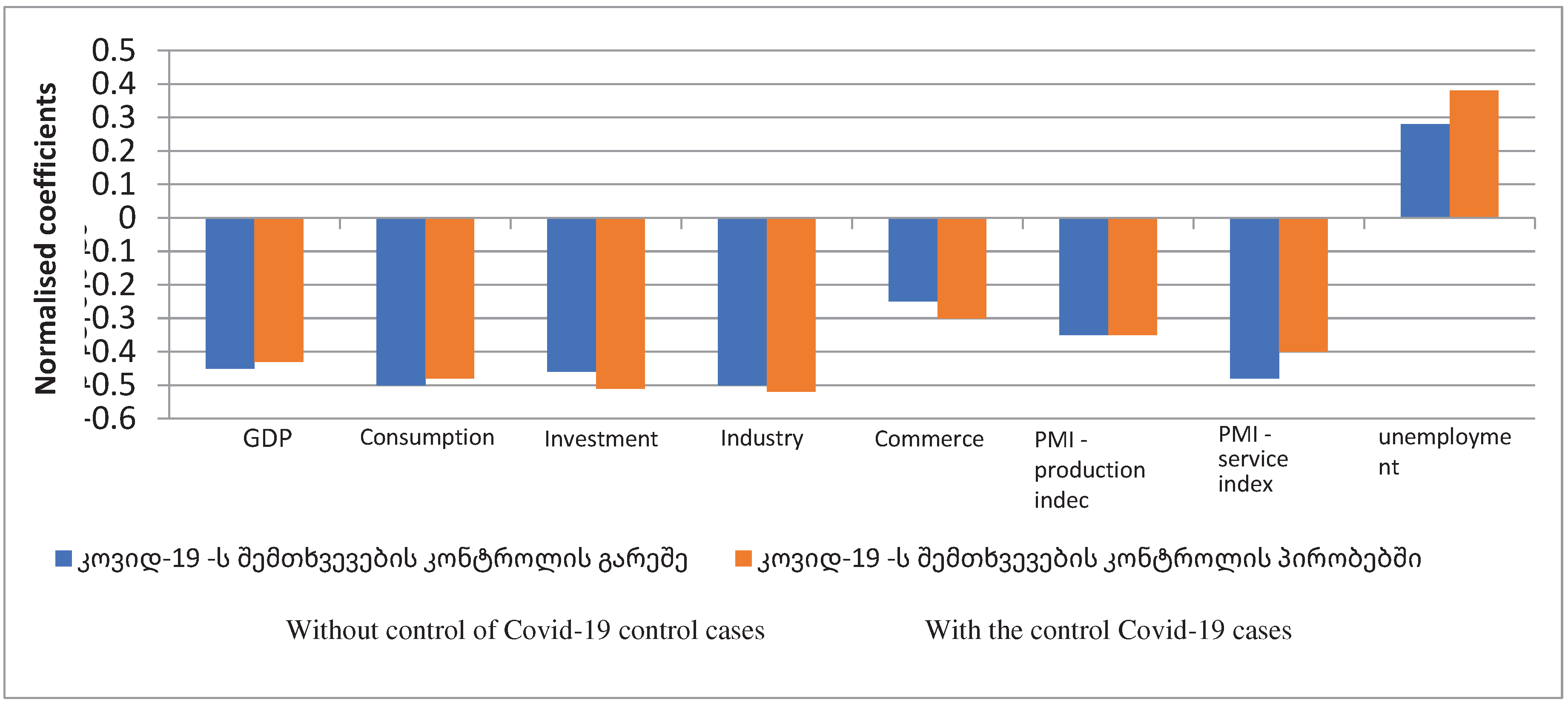

According to expert assessment, the rate below the magnitude was maintained in 2022. In 2021, the rapid change in economic factors led to the unpredictability of development and required a substantial adjustment of the rehabilitation plans, due to which the forecast values of economic growth in most countries were changed. For example, in 2021, the specified forecast value of economic growth in the USA increased by 2.1%, in Japan by 0.8%, and in the countries of the Eurozone, on the contrary, these indicators decreased, which was caused by new restrictions and economic shutdowns in several countries. The IMF predicted relatively low rates of economic development for the medium-term perspective, which was fully consistent with the main principles of post-crisis rehabilitation. (

Table 1).

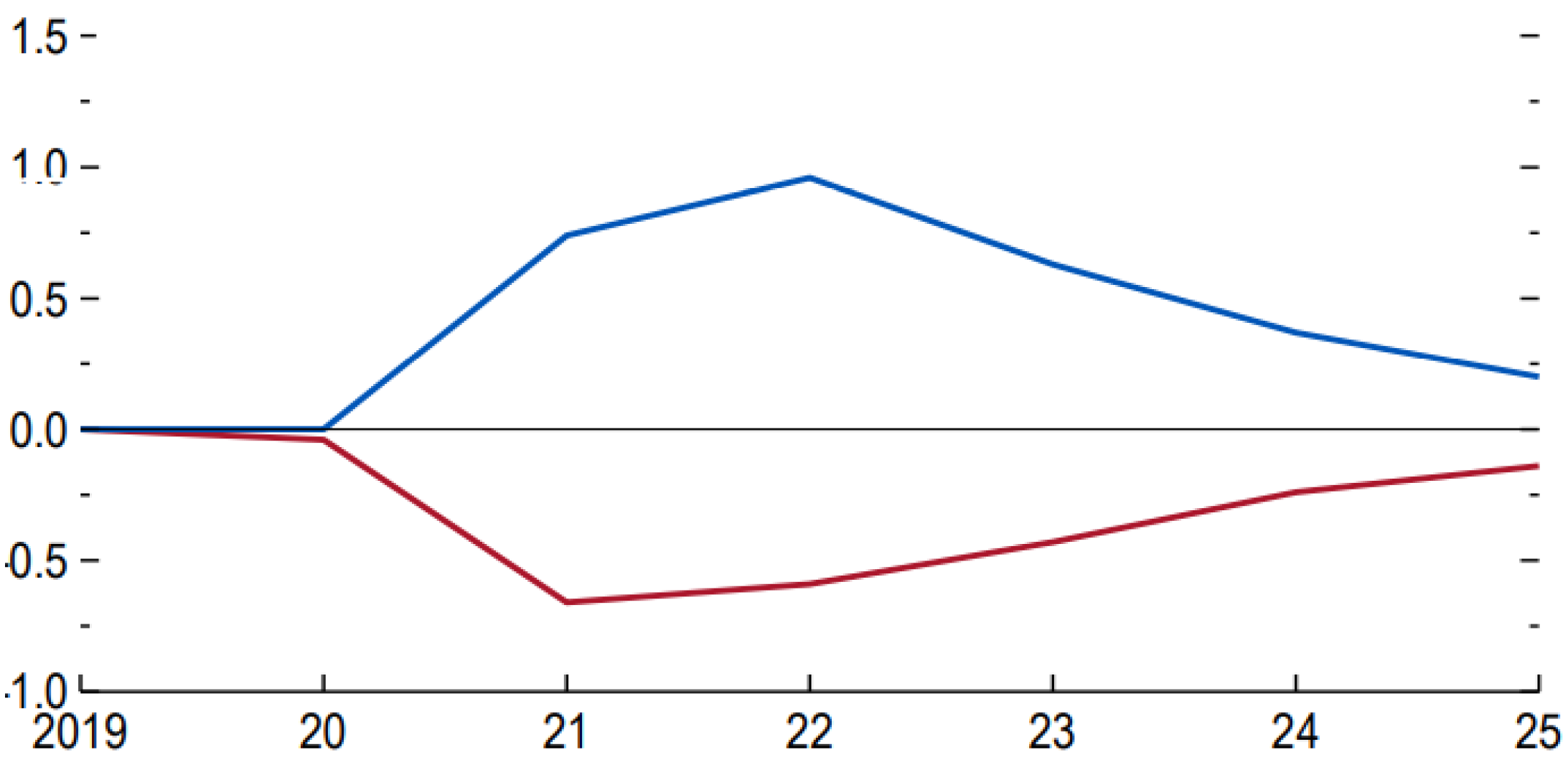

Developed countries have been able to provide effective assistance to households. Fiscal tools were successfully used to increase state financing of direct taxes, capital, soft loans, grants, transfers and other mechanisms. Along with this, central banks have effectively used open market operations, increased credit financing, interest rate reductions, and other monetary policy tools. Effective monetary and credit, fiscal and financial policies have protected the world from a larger crisis. The transfer policy of the state quickly increased consumer spending, it was especially useful for entities with a deficit of liquid funds, credit guarantees, loan financing programs practically eliminated the risks of bankruptcy, by IMF 1990-2020 A study of the economies of 13 developed countries showed that the risk of bankruptcy of economic agents during the Covid-crisis has decreased compared to previous recessions, however, this may also be an objective result of the moratorium imposed by the government on accepting bankruptcy applications in some countries.

Figure 2.

Impact of global crises on private business bankruptcy. Source: CIEC, Global Economy Data, 2020.

Figure 2.

Impact of global crises on private business bankruptcy. Source: CIEC, Global Economy Data, 2020.

The World Bank suggested that the authorities maintain the support strategy until the pace of economic recovery accelerates and calculated the relationship between economic renewal and the effect of anti-crisis reform, which made a significant change in the IMF’s 2021 economic recovery forecast parameters.

Figure 3.

Forecast of the world economic growth. Source: CIEC, Global Economy Data, 2020. Post-pandemic crisis management strategy of Georgia.

Figure 3.

Forecast of the world economic growth. Source: CIEC, Global Economy Data, 2020. Post-pandemic crisis management strategy of Georgia.

Macroeconomists argue that the rate of economic rehabilitation is related to the effective functioning of the country’s healthcare system, the flexibility of its structure, the ability to adapt, and the experience of functioning in similar conditions. Accordingly, the rehabilitation terms should be different depending on the economic system and development level of a country. For example, experts forecasted the pre-crisis level of the USA and Japan to be restored by the middle of 2021, while the Eurozone countries and Great Britain were predicted to restore the pre-2019 results only after 2022.

Georgia showed one of the best results of global crisis management in the world. This experience has become a precedent for other countries. Few success stories can be mentioned: Not a single large enterprise stopped operating in the country; international reserves increased by 11.5% and local exports by 3.5%, 1,056 million; the trade deficit improved in dollars and amounted to 4.7 billion dollars, as a result of the effective monetary policy. In 2021 the international credit rating company Fitch left Georgia in the BB category of the economic stability according to the ease of doing business and the attractiveness of the business environment, maintaining the investment environment and ensuring resilience to external shocks.

A key success factor can be identified as the government’s attempt to maintain a balance between managing the pandemic and minimizing the economic damage. At the beginning of the crisis, the pandemic caused a sharp decrease in the economy of Georgia and further aggravated the existing problems: exchange rate of GEL, inflation, investment, unemployment, and public debt. The largest decrease was recorded in the hotel and restaurants sector - 80%, followed by a 20% decrease in the transport and warehousing sectors. Entertainment and leisure sector services decreased by 15%.

In terms of the degree of restrictions, Georgia was ranked 15th out of 184 countries, which indicates rather strict restrictions, and which was reflected in the general macroeconomic balance. Due to lockdowns, the budget of Georgia lost 16 million GEL daily in 2020, with a total of one billion GEL. The economic decline in Georgia was 6.1% in 2020, however, according to experts, if the economy had not been shut down, the overall decline would probably have reached 8%. This, along with a sharp slowdown in economic growth, led to an increase in the budget deficit from 4% to 9%.

Georgia managed to undertake successful fiscal and economic policies. In the very beginning of the crisis, the country determined new priorities of its fiscal policy which allowed to stabilise the scale of the crisis and significantly reduced the degree of destruction. State programs of entrepreneurial support, transfers to domestic farms and social assistance for persons with limited liquid funds showed significant results. Thanks to this new policy Georgia managed to provide a large-scale fiscal support to households in the second phase of the crisis, by expanding the purchase of assets, increasing credit financing, and reducing the interest rate.

The pandemic crisis made significant changes in the budget of Georgia and required its substantial adjustment. Total expenses in 2021 It amounted to 25% of the GDP, 2 billion from the state budget for the anti-crisis program. GEL was allocated, which went to two priority directions, - financing of state social projects (grant of allowances, financing of population social protection projects, increase of teachers’ salaries, indexation of pensions) and business support (430 million GEL).

In the strategy of state support of the economy, a special place was given to the rational spending of state funds and the issue of regulating the state debt. The new policy is derived from the basic requirements of the “EU Fiscal Rule” and aims to four outcomes: control the budget deficit, increase the efficiency of spending of funds, reduce the cyclicality of fiscal policy and prevent its unsustainability. The International Monetary Fund evaluated this strategy as particularly successful, namely because the state managed to keep the main internal resources necessary for macroeconomic balance, which led to unprecedented rates of economic recovery in the country already in 2021 (International Monetary Fund (2020).

Georgia also changed its priorities in terms of economic policy. The transit and tourism function were defined as the main priorities of the Georgian economy, with the aim to create prerequisites for a stable positioning in the world markets. In 2021, the growth of the Georgian economy amounted up to 10.6%, which was the best result in the region and the second-best result in Europe. IFM predicted to Georgia the highest economic growth in the region and in Europe (34.5%) for a medium-term period (2021-2025). In 2022, compared to the previous year, the volume of PUI doubled and reached an unprecedented level for Georgia - 1 billion 675 million USD which created additional resources for economic growth. (Geostat, 2020).

An important feature of the post-crisis rehabilitation of the economy is the openness of markets and the positioning of countries in international trade. The correct crisis management strategy of Georgia and the efficiency of post-crisis rehabilitation led to a significant revival of foreign economic activities and restoration of pre-pandemic foreign trade level. In November 2022, the export volume of Georgia increased by 14.1% compared to the previous month and amounted to 491.1 million US dollars. This significantly contributed to the stabilisation of financial markets and to the strengthening of the local currency (the GEL strengthened by 13 points against the US dollar in November 2022, compared to the corresponding period of 2021. The level of public welfare has also increased. In the third quarter of 2022 the price of the hands of employees in the business sector increased by 145 USD and amounted to 610 USD. In November, compared to November of the previous year, the import increased by 20.8% and amounted to 1248.8 million US dollars, and the index of overlap of imports with exports increased by 39.3%. (Geostat, 2022).

According to the IMF’s expert assessment, high rates of economic growth in the medium term will bring significant progress and world recognition to Georgia, in particular, by 2027. Indeed, the legal foundations of business management and the parameters of association with international legislation have been significantly improved. According to the World Justice Project, according to the index of freedom from corruption, Georgia ranks 30th in the world, which indicates a significantly improved environment in terms of business promotion and interest of foreign investors. IMF also predicts the increase in GDP per capita and with the optimistic forecast the country has the possibility to move to the group of rich countries (15,200 US dollars/per capita) by 2030 (IMF, 2020).

Chapter 6. An Optimal State Strategy of Post-Crisis Management

Economic scholars disagree on the optimal solution to manage a crisis. Some argue that monetary policy-based stabilisation policies are more effective in ensuring macroeconomic stability (Kondratenko, V. & Kostadinoska-Miloseska, 2017). Others, consider that fiscal policy instruments have a higher control power than monetary policy instruments (Cevik, Dibooglu, & Kutan, 2014). Yet others put forward the help of coordinating between monetary and fiscal policymakers (Tetik & Yıldırım, 2021; Jawadi et al., 2016). It is mainly acknowledged the role of networks in crisis management. However the networks can bring both, a benefit, or a risk as it also increases interconnectedness and interdependence between countries. If a network can increase risk-sharing effects by absorbing external shocks efficiently, it can also heighten the degree of contagion effects by widening the channels for shock spillovers (Ahn et al., 2017). Different countries implemented different strategies to fight against the economic recession. Some proved to be more successful than others. Even if the contextual nature of the crisis does not allow one to come up with one optimal strategy for the global economy, it is argued that certain similarities can be observed between developing, on the one hand, and between the developing economies, on the other hand.

Some major fiscal and economic policies were implemented in Georgia which proved to be very positive in managing the economic crisis. In the beginning of the crisis, Georgia determined new priorities of its fiscal policy which allowed to stabilise the scale of the crisis and significantly reduced the degree of destruction (Tabatadze, 2022). State programs of entrepreneurial support, transfers to domestic farms and social assistance for persons with limited liquid funds showed significant results. In the second phase of the crisis the country managed to provide large-scale fiscal support to households thanks to this new. It allowed expanding the purchase of assets, increasing credit financing, and reducing the interest rate.

The present research has revealed some interesting and novel findings. First, we observe new approaches to interstate cooperation, where unified standards of integration give way to individualism and deglobalized authenticity of countries. Because of this, stabilisation programs need to be developed individually, considering the structure of the economy of each country and the type and severity of the crisis. The peculiarity of the global economy, against the background of the decentralisation of the world unified management system, has become the activation of centralized management elements within countries. This is based on a new standard of world cooperation, in which the requirements of integration should be balanced with the need of developing national economies.

Another interesting result is a need for a close collaboration in parallel of increasing decentralisation. Indeed, an effective management of crisis needs ensuring the compatibility of the anti-crisis policies of different countries, which gives a greater result in a complex environment. Cooperation is particularly effective in creating and harmonizing a common fiscal space. The development of a common policy between countries is very important for trade and technological relations, as well as cooperation in combating the negative consequences of climate change.

Third, and particularly for developing economies, this research has shown that the perspectives of cooperation with the European Union are especially important for the proper management of post-crisis processes. In the case of Georgia, this is primarily based on the “Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement - DCFTA”. In addition, bilateral cooperation in economic and social development, energy security systems and the construction of state institutions are necessary. In Georgia, the issues of economic and social integration with the EU were initially reflected in the PCA and ENP agreements on partnership and cooperation. These programs aim to harmonise sustainable development and competition policies, which includes cooperation in the field of free trade, education, intellectual and industrial property, consumer rights, food safety, poverty reduction and provides deepening of relations in issues of social equality. Today, Georgia is involved in the “Eastern Partnership Program”, which provides for the establishment of a high level of democracy, the activity of civil society, cooperation in security, migration, and border management issues.

As a result of this research, the following theoretical and practical contributions were highlighted. First, economic rehabilitation programs in the post-pandemic period should be focused on the final elimination of the problems that arise during the crisis, and not on their temporary dissimulation. This should be done by identifying priority directions and concentrating on them.

The second contribution is the development of a framework for managing transformational processes in the post-crisis period. The framework proposes the following six forecasts:

1. It is possible that the pre-crisis negative factors of economic development may be strengthened (increasing inequality, increase in public debt, aggravation of poverty, weakening of human capital).

2. Due to the shortage in natural resources, the resource dependence of countries and the dominance of energy providers in the world economic and political processes will increase.

3. Cooperation between countries in matters of foreign trade, mutual exchange of technological resources, reduction of the negative consequences of climate change will enter a new phase and gain significantly more weight.

4. In the format of interstate relations, priority will be given to financial relations between countries, especially the issue of creating a single fiscal space as an innovation of integration processes will be activated.

5. As state investments harmonizes with the fiscal environment, the governments should closely consider this aspect in their economic policies.

6. The structural transformations of the economy should be considered in countries’ development programs, and it should reflect the modern growing scale of the introduction of production growth, nanotechnologies, digital economy, and green infrastructure. These programs should ensure the economic equalisation between countries, their social and institutional stability, the competitiveness of the economy and the possibility to prevent risks.

The third contribution of this work is especially important for developing economies. Studying the example of Georgia showed that for developing economies, the crisis period can be used as a lever for a strategic change. As a result of the carried-out reforms and investments, Georgia used the opportunity to become a safe and attractive country for foreign investment, to successfully play the role of a regional leader and to implement liberal administration of the economy, which is one of the important prerequisites for European integration. Changing from a transport corridor to a logistics hub of the region, requires changes in two directions. First, the post-crisis rehabilitation strategy requires the promotion of the development of the business sector and a wide use of financial mechanisms (in a form of state support). High rates of growth and its structural transformation policy put new demands on the mechanisms of economic regulation. This involves the stabilisation of financial markets and ensuring the free movement of capital. Coordinating goals and harmonizing national monetary strategies should become the basic principle of the operation of countries’ monetary strategies in the global environment. Georgia’s involvement in the “Eastern Partnership Program” is based on new approaches to cooperation, definition of unified crisis management standards, coordination of states’ anti-crisis currency strategies and development of complex mechanisms. Second, in terms of legislation, states should accelerate the type of reforms that specifically encourage the growth of domestic economic activity. Here, together with the executive authorities, the parliament has an important function, where different types of strategic and detailed action plans should be initiated. Land reform, necessary legislative changes in tourism and energy, production and other sectors should be accelerated.

Chapter 7. The Role of Fiscal Policy in an Economic Rehabilitation during a Post-Crisis Period

One of the main state functions is to create an optimal business environment on the basis of existing legal and regulatory framework and, in the context of an economic crisis, implement reforms with social and economic consequences (Tabatadze M., Tsanava N. 2009). The reforms should ensure the reduction of social tension, the legal protection of economic security, and, consequently, the stabilization of the development process. All this requires new approaches to socio-economic processes and the formation of a modern, social oriented legal environment (Tabatadze, 2017).

During an economic crisis, a state can use complementary mechanisms to overcome the recession: monetary policy-based stabilisation policies, fiscal policy instruments, a mix of the two approaches (Tetik & Yıldırım, 2021; Kondratenko, V. & Kostadinoska-Miloseska, 2017; Jawadi et al., 2016; Cevik, Dibooglu, & Kutan, 2014). One of such mechanisms is an expansive fiscal policy. It is acknowledged that an expansive fiscal policy is the main tool to quickly stimulate the economy (Tabatadze, 2016; 2018). The expansive fiscal policy implies increasing the budget deficit by increasing expenditures or reducing taxes. While this stimulates direct output, it also causes the rise of interest rates, leading markets to expect lower output due to reduced investment spending. However, increase in the interest rate also reduces aggregate demand and net export (Tabatadze & Tsanava, 2009).

The “expensive money” policy also has the same effect, which ultimately leads to an increase in the trade deficit and, as a result, an increase in the public debt. To overcome these problems, the government can resort to protectionist policies (Huidumac-Petrescu & Popa, 2016), for which, among other mechanisms, it can use Smoot–Hawley tariffs. Since payments are the least elastic component of the budget mechanisms, state expenditures are considered a more active tool for stabilizing the economy (Tabatadze, 2020). To reduce the budget deficit, the government can, for example, cut spending, while lowering interest rates stimulates investment, which can help bring the economy back to equilibrium.

One of the tools to assess fiscal stability is using risk and debt stress indexes. In 2011 the IFM defined the general framework-principles of fiscal security and its basic norms in accordance with the Organic Law “On Economic Freedom”. The framework suggests the following parameters:

Tax burden - 30% of GDP Georgia – 23%

Budget deficit - 3% of GDP Georgia – 2.8%

State debt - 60% of GDP Georgia\ \39.8%

Stable incomes.

These Maximum values are based on the “fiscal rule of the European Union”, the main requirements of which are: control of the budget deficit, increasing the efficiency of spending of funds, reducing the cyclicality of the fiscal policy and preventing its unsustainability.

The recent economic crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, put forward the need for double standards to cope with the recession. On the one hand, it was necessary to follow strictly defined global guidelines. On the other hand, different states had to elaborate local initiatives, taking into account local contexts.

Crisis management varies depending on the extent of integration of countries into global systems and on their level of development (Tabatadze, 2022; Ahn et al., 2017). Developed countries are more resistant to changes in world markets, because of their strong economic potential. On the other hand, the poor or the developing countries, due to their dependence on powerful countries, are more vulnerable and act as simple consumers in the world systems (Tabatadze, 2022; Valinurova et al., 2021; Abbes, 2019; Adomnicai, 2019).

Despite a similar negative impact of the pandemic on the global stock market, significant differences can be noted among countries, with least developed economies being the most impacted (Angosto-Fernández & Ferrández-Serrano, 2022). The stability of a developing economy is very sensitive to external shocks and global transformation processes (Canofari, Bartolomeo & Messori, 2023).

Managing the state debt is particularly important in order to ensure economic stability. This includes determining its effective management mechanisms. First of all, it is important to evaluate the basic risks that affect the growth of the public debt and lead to the devaluation of the national currency. The increase in public debt is a necessary sign of crisis and an objective inevitability, especially for developing countries. As a result of this process, together with the devaluation of the national currency, significantly increases the debt service denominated in foreign currency.

Chapter 8. The Budget System of Georgia

Since 2012, the budget system of Georgia has been based on the principle of program budgeting at the central and municipal levels. It is considered that the budget arrangement is one of the main indicators of the democratization of the country. In Georgia, the system is federal and shows the hierarchical independence of each level of the budget, both in terms of autonomous planning of the revenue base and the expenditure part (Tabatadze, 2018). According to the World Bank’s seven criteria for assessing the quality of fiscal decentralization, Georgia has an independent budgeting system of average quality. This indicator was significantly improved by the latest budget reforms, which affected the calculation of the equalization transfer according to VAT (Tabatadze, 2016). Three types of transfers remain dominant - special, targeted and capital, which indicates the still great importance of the transfer policy and a rather high degree of centralization of the budget system. The new model of income distribution, which involves determining the equalization transfer according to VAT, makes the source of income more diverse and stable, which the “European Charter” considers an important condition of fiscal decentralization and obliges municipalities to find alternative sources of income (Tabatadze, 2020).

Following the IMF’s general framework-principles of fiscal security, Georgia respects the advised maximum values for different components: tax burden - 23 % of GDP; Budget deficit - 9% of GDP and the state dept - 60% of GDP. While the IMF assessed Georgian fiscal system as stable, it also highlighted certain challenges, out of which the following were the most important:

Assessment of long-term fiscal sustainability, (medium-term assessment system - MTEF has been in effect in Georgia since 2007);

Management of reserve funds of the state budget;

Financial management of state enterprises.

Important initiatives were implemented to overcome these challenges as detailed below:

1. One of the important characteristics for evaluating the country’s budget and payment system is the degree of fiscal decentralization. According to the data of the World Bank, Georgia belongs to the group of countries with medium level of decentralization. In this matter, the IMF’s recommendations were based on the fundamental provision of public development, on the hierarchization of the governance system and the harmonization of relevant functions. In connection with determining long-term fiscal sustainability, a new framework-document of strategic partnership with the European Union was developed - “Multi-year Indicative Program-MTP”. This document aims at wide scope of this cooperation and new partnership directions (European Parliament, 2020).

2. Efficient management of reserve funds is regulated by the “Law on the State Budget”, according to which the volume of reserve funds should not exceed 2% of annual budget allocations. Meanwhile, the reserve of the President’s fund is 5 million GEL, and the reserve fund of the government - 85 million GEL, thus exceeding the 2% limit [Georgian Law, “On Amendments to the Budget Code of Georgia”, Parliament of Georgia, Tbilisi, 2018]. According to the analysis of IDFI (Institute for the Development of Freedom of Information), the annual spending from the President’s reserve fund does not exceed this limit provided by the budget law, while the government’s expenses exceed it twice. The IMF considered the substantiation of the purpose of reserve fund expenditures and the absence of a single standard for determining this purpose to be an essential problem. According to the Euro standard, a significant part of the reserve fund should be intended to finance expenses caused by force majeure circumstances instead of unforeseen expenses (IDFE, 2019).

3. The IMF has given essential importance to the financial management of the state enterprise in order to reduce the budget deficit of Georgia. Today, there are 236 state enterprises in Georgia, with 66 subsidiary companies, and their debt to the budget is 6.5 billion GEL. A large part of these enterprises is denominated in foreign currency. In this segment, the IMF gave preference to the requalification of the mentioned enterprises into public corporations through restructuring, and the effective management of this process determined a great role in the formation of budget revenues. For fiscal stability, attention should be focused on unanticipated, unplanned obligations, in particular, uneven distribution of budget expenditures over time, obligations of new social programs necessary depending on the specific situation, debts of state companies, public enterprises, changes in the age structure of the population (the share of the retirement age group was assessed as problematic by the IMF) growth).

Chapter 9. The Impact of the World Pandemic on the Budget System of Georgia

The pandemic crisis made significant changes in the budget of Georgia and required its substantial adjustment. The economic recession and the strategy of “locking down the economy” had an extremely negative effect on the budget. In 2020, the budget of Georgia lost 16 million GEL daily under the lockdown conditions, which totaled one billion GEL. The economic decline in 2020 showed 6.1% drop, however, according to experts, if the government had not implemented the lockdown policy, the overall decline would have been higher (8%).

Total expenditures in 2021 amounted to 25% of GDP. Two billion GEL was allocated from the state budget to the anti-crisis program, which went in two priority directions: Financing of state social projects (granting of allowances, financing of social protection projects of the population, increase of teachers’ salaries, indexation of pensions) and promotion of business (430 million GEL). The increase in state expenditures increased the budget deficit during the pandemic crisis from 2% to 9%, and by 2024 it is planned to restore this parameter to the pre-crisis level.

In the conditions of a significant increase in public debt caused by the crisis, its effective management is extremely important for underdeveloped countries, as debt substantially increases fiscal pressure and hinders economic growth (Tabatadze, 2019). Taking into account this factor, a new platform for the restructuring of external debt was developed with the joint agreement of international financial institutions - G-20. This framework agreement establishes significantly relaxed standards for the restructuring of debt agreements and the servicing of obligations in the field of international financial cooperation, which in the medium term will have a positive impact on the budget structure of the countries and the rates of economic growth.

The state debt was one of the biggest challenges for Georgia. Despite the fact that the state debt exceeded the safety limit (2020-60.3%, 2021-60.1%), the scale of economic rehabilitation made it possible to return it to the normative framework already in 2022. In order to ensure macroeconomic balance, it’s important to make a complex study of its indicators. In addition, it is necessary to correctly assess the optimal portfolio of public debt and determine the effect of public debt for the medium and long term.

Analysing the case of Georgia in the lens of global initiatives allows identifying three main recommendations for the governments of developing economies to cope with the crisis and develop successful post-crisis strategies. First, a balance needs to be made between the local priorities and global interests to be able to find a potential niche. Second, the post-crisis rehabilitation strategy requires supporting entrepreneurship using a wide range of complementary financial mechanisms. Third, it is important to implement the reforms which specifically encourage the growth of domestic economic activity.

Chapter 10. The Fiscal Policy Initiatives in Georgia after the World Pandemic

Despite a particularly severe effect of the world economic crisis on Georgia, the country showed one of the best results of global crisis management in the world. In 2021, while most of the developed economies were still fighting against the crisis and were not yet in the post-crisis period, the international credit rating company Fitch left Georgia in the BB category of the economic stability according to the ease of doing business and the attractiveness of the business environment, maintaining the investment environment and ensuring resilience to external shocks. The success can be explained by the complementary fiscal initiatives implemented and by the correct management of the crisis. The correct management in the given context can be defined as the identification of two main steps of the crisis: the high point of the crisis and the post-crisis periods, and the implementation of appropriate reforms for each step.

In the beginning of the crisis, a special place was given to the rational spending of state funds and the issue of regulating the state debt. The government had to implement a new policy in this regard, which was derived from the basic requirements of the “EU Fiscal Rule” and aimed to achieve four main outcomes:

control the budget deficit,

increase the efficiency of spending of funds,

reduce the cyclicality of fiscal policy,

prevent its unsustainability.

The International Monetary Fund evaluated this strategy as particularly successful, namely because the state managed to keep the main internal resources necessary for macroeconomic balance, which led to unprecedented rates of economic recovery in the country already in 2021 (International Monetary Fund (2020).

Correct fiscal policy significantly reduced the destabilizing scale of the crisis and the degree of destruction. State programs of entrepreneurial support, transfers to domestic farms and social assistance for persons with limited liquid funds had special positive results.

That is why, at the last stage of the crisis, Georgia was able to fully provide large-scale fiscal support to households. The central bank reinforced this process by expanding asset purchases, increasing credit financing and reducing interest rates. State programs of loan financing and credit guarantees, as well as sharply reduced, but still remittances from abroad, practically eliminated the risks of enterprise bankruptcy. A study of 13 developed countries by the IMF found that the risk of bankruptcy of firms during the Covid-crisis actually decreased, in contrast to post-1990 recessions. According to experts, a certain reason for this could be the moratorium on receiving bankruptcy applications in some countries during the rising phase of the crisis. In general, from the beginning of the crisis management, the fiscal policy in Georgia was evaluated as successful, to the extent that the state kept the main internal resources necessary for macroeconomic balance, which led to unprecedented rates of economic recovery in the country already in 2021. It should also be taken into account that international aid programs also saved non-viable companies, which, in turn, may lead to a decrease in overall productivity and growth rate in the future.

Chapter 11. Fiscal Decentralisation and Macroprudential Strategies as Local Responses to Global Economic Crises

Today the world witnesses a particular scenario where Globalisation and decentralisation co-exist. This not contradictory, however different in nature processes create a unique setting for crisis management. In the context of Globalisation, countries are increasingly dependent on larger economies and on each other. While, in a context of increasing decentralisation, the role of individual states and even local governments becomes crucial in order to guarantee economic stability and resistance to different shocks.

The World’s geopolitical structure is under constant modification. Monopolization of economic processes by the World’s largest economies, forms a new balance of economic forces and reshapes the universe, based on new principals. Globalisation, one of the forms of today’s economic relations, has its own ideology and economic rules, often different from countries’ local systems. Sometimes it is even in conflict with national economic interests. That is why, the main objective of adapting national economies with Globalisation, is protecting local interests and decreasing the negative effects of global ideologies. For this, different countries should adopt different strategies, taking into account the country’s social and political situation, economic specification, national values, geopolitical situation, etc. Each country has to elaborate its own anti-shock instruments that help the increase of advantages provided by global processes and prevent the national economy from undesirable outcomes.

Globalisation breaks political barriers and creates more economic freedom. Opening the boundaries is the only possibility for developing countries to enter international markets, adopt the World’s economic rules and learn how to achieve success. The influence of globalisation on this process most importantly depends on the ability of national economies to understand the integration process and manage it for its own interests. The example of developing countries that achieved success, lays on transfers of new technologies and innovation, on spillover effects of investments and on other externalities of economy. That is why, governments of developing countries should analyse how important it is for them to import the foreign capital; identity the means that can guarantee the positive effects from this investment and try to limit the negative impacts. The World’s largest economies can initiate some global processes that impact local social development. Naturally, these large economies define their strategies based on private objectives.

Undoubtedly, it is up to local governments to take the necessary actions for protecting national interests and balancing the macroeconomic situation inside a country. Most important anti-shock mechanisms against the negative effects of globalisation are establishing adequate juridical and institutional basis, having significant savings and investing in productive assets. In terms of experience, only the countries with such kind of strategy have succeeded in economic development. Importing the latest technologies and innovations, adopting new managerial methods, entering the global competitive markets, clustering foreign investments generates strong sustainable effects and realises the theory of convergence. Nevertheless, these advantages should only be accepted under the conditions that the globalisation will also serve the progress of national economies and will be based on the priorities of national ideology in the integration process.

A state plays a dominant role in crisis regulation. Taking into account the degree of the crisis and the specificities of its expansion, the mechanisms used in regulation are differentiated. This makes the issue very important to study. One important mechanism of decentralisation for crisis management is a strong fiscal decentralisation. The purpose of fiscal decentralisation is to divide functions and responsibilities between levels of government and link them to the source of income. Studying the basic principles of the country’s budget system, its structure and formation, identifying the functional and financial dependencies between the budget levels, is one of the top priorities in contemporary research. Strengthening local government and increasing the level of decentralisation is a challenge that will develop the democratic process and the inclusive economic growth that is the fundamental goal of developing economies.

Decentralisation, in its wide sense, describes the process of redistributing functions, powers, people and/or things from a central location or an authority to dispersed units. While centralization, especially from a governance point of view, is widely studied and practiced, there is no common definition or understanding of decentralisation. This diversity of interpretation is due to many reasons: different ways the decentralisation is applied, different traditions and specificities of each country in terms of self-governance structure, etc. That is why each state proposes its unique way of differentiating local and central government functions and the degree of autonomy of self-governing units.

Even if the decentralisation is not the end in itself, it can be used as a means to create more responsible, open and effective local government and to foster involvement of community-level in decision making. Those studying the goals and processes of implementing decentralisation often analyse it from a holistic or system approach. According to the United Nations Development Programme the holistic approach is made operational “by taking a whole systems perspective, including levels, spheres, sectors and functions and seeing the community level as the entry point at which holistic definitions of development goals are most likely to emerge from the people themselves and where it is most practical to support them. It involves seeing multi-level frameworks and continuous, synergistic processes of interaction and iteration of cycles as critical for achieving wholeness in a decentralized system and for sustaining its development.” (UNDP, 1997, p.7).

Monor classifies decentralisation into three major types: Deconcentration or administrative decentralisation, Fiscal decentralisation, and Devolution or democratic decentralisation. For him, deconcentration refers to the dispersal of agents of higher levels of government into lower level arenas. Devolution refers to the process of transferring resources and power to lower level authorities which are largely or wholly independent of higher levels of government. As for the fiscal decentralisation, it refers to “downward fiscal transfers, by which higher levels in a system influence budgets and financial decisions to lower levels” (Monor, 1999, p.5-6).

Fiscal decentralisation stands for decentralizing revenue raising and/or expenditure of money to a lower level of government while maintaining financial responsibility (Tabatadze, 2019). While this process usually is called fiscal federalism, it may be relevant to unitary, federal and confederal governments. It actually can be seen as a way of increasing central government control of lower levels of government, if it is not linked to other kinds of responsibilities and authority. Within a fiscal decentralisation the authority may pass to local bureaucrats who are accountable only to superiors at higher levels, or to unelected appointees selected from higher up. Such fiscal transfers are linked to mechanisms which give people at lower levels some voice. There are no rules of successful or correct decentralisation of fiscal relations. However, researchers and practitioners identify certain principles that generally lead to effective results.

Regional policy of a country is related to the organization of government. It ensures the optimal territorial distribution of the country’s spatial structure and functions of the state government in order to protect the unity of its internal structure. The territorial organization of the hierarchical principles and realization powers of financial leverage is still subject of the priority areas of scientific studies and theoretical debates. Country’s regional policy depends on the overall territorial organisation of its governance. It covers the issues of territorial organization of the hierarchical principles and realization powers of financial leverage. Even though the economic autonomy of territorial units causes socio-economic development, it can also contain certain threats in case of active decentralisation, as far as it may originate a socio-economic conditions disproportion for certain regions’ inhabitants. Litvack et al. argue that at the regional level, fiscal and administrative capacity may make it easier to decentralize responsibilities only to some provinces or states. “In other cases, it may be feasible to decentralize responsibilities directly from the central government to the private sector rather than going through local governments” (Litvack et al, para. 79). Fiscal decentralisation, as an important component of inclusive economic growth, is long promoted by the European Union. Non-member states also have the possibility to fully or partially apply the criteria advocated by the EU guidelines.

Another important mechanism for successful crisis management is a macroprudential strategy. The macroprudential regulation is a new methodology for the analysis of system based crisis. The crisis of the late 2000s showed the limit of previous methods, like microprudential regulation. However, the misuse of this new method can cause even bigger issues. In the conclusion of this article, we would like to highlight the major mistake that would make future macroprudential policy much harder. The ability of macroprudential authorities to act can be cut quickly in the event of a major mistake in this policy area.

This happened in the case of the Credit Control Act in the United States. Congress in 1969 gave the President the power to direct the Fed to implement credit controls in the US economy, with a very wide grant of authority. This was not used until 1980, when President Carter gave these powers to induce the Fed to take strong actions to rein in credit growth, which was seen as contributing to the inflationary environment. The economy quickly went into recession and there appeared to be a very direct connection between the credit controls and this drop in activity. The economic growth resumed when the controls were removed, and this happened with a considerable bounce-back. The disastrous use of such a strong set of macroprudential tools made it much harder to attempt future macroprudential actions, even of milder and more conventional form.

After the crisis of the late 2000s the stability of individual financial institutions taken in isolation is not enough guarantee for the stability of the whole financial system. Because actions of individual banks can harm others through interconnection and contagion effects. In addition, when individual banks cannot withstand sector competition they should be allowed to fail - if not, this would be dangerous for the efficiency and ultimately the very stability of the system. In this sense the stability of individual financial institutions is neither necessary nor sufficient. That said, if the reliability of a Systemically Important Financial Institution (SIFI) is in danger, then systemic risk may arise. That is why, the stability of systemically relevant financial firms may be necessary to ensure financial stability.

A macroprudential method of financial stability. Macroprudential policy is generally aimed at two different but not mutually exclusive goals. First, macroprudential policy should strengthen the resilience of the financial system as a whole. Second, it should limit system-wide excesses on asset and credit markets. In other words, macroprudential supervision and regulation is concerned with the stability of the entire financial system, and not of individual institutions.

A main substance of macroprudential approach is monitoring structural systemic risk. This is the risk that the default of a single bank – because of its size, market share or interconnectedness – could threaten certain functions that are vital for the economy, such as payment transactions or lending to the real economy. This is the problem arising from institutions that are “too big (or interconnected) to fail” (TBTF). The key objective of policies addressing this risk is to reduce the likelihood of crisis at such institutions and the costs to the economy in the event of such a crisis.

One way out of these risks is to impose progressive capital adequacy requirements. The equity capital causes the importance of the banks systemic. When a bank has a big systemic importance, it is required to hold more equity capital. If capital adequacy requirements increase in step with systemic importance, banks have an incentive to stay smaller and less systemically important. Opposed to this, the extra capital at least makes them more resilient. In addition, given that it is impossible to avoid a future crisis, measures that improve the resolvability of a distressed Systemically Important Financial Institution (SIFI) are important. There are a variety of measures, from a mandatory separation of financial institutions, e.g. along the lines of the Glass-Steagall Act, to less intrusive rules such as requiring banks to ex ante demonstrate that their systemically important functions can be maintained in the event of a severe crisis. The TBTF (“too big to fail”) issue is particularly suitable in Switzerland. This explains that already in 2011 Switzerland adopted a package of measures designed in the sense of complementarity. It prescribes a capital surcharge for SIFIs allowing banks to partially fulfill capital requirements by means of issuing Contingent Convertible Capital (cocos). The cocos are converted exactly at the time when financial means are needed for restructuring a bank, this means acting as an internal crisis fund. The package requires banks to show convincingly – on the basis of “emergency plans” – that they are organized in a way to be able to maintain systemically important functions in the event of a crisis, thus reducing the need for a public bail-out. If they are not able to do so, the regulator, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority – FINMA, may impose specific organizational measures.

The second central element of a macroprudential methodology is to directly address the root causes of cyclical systemic risk. This element of systemic risk captures the procyclicality of financial agents’ behaviour which can cause expansion of the financial cycle and increase its instability if left unchecked. This is a classical collective action problem. Procyclicality can arise, for example, from the tendency to underprice risk during booms and to overprice it in downswings. The main objective here is to limit too much risky behaviour on the part of financial intermediaries, and avoiding excessive credit growth, an overvaluation of assets and preventing bubbles from emerging, or at least constraining their size. The interest rate comes to mind as a potential instrument. Indeed, raising interest rates seems like a natural response to a credit boom, as the higher market borrowing rates exert a dampening effect on credit demand and eventually on asset prices. When this calls for deviations from otherwise optimal policy, one talks of “leaning against the wind”. In economic growth, it would involve central banks setting higher interest rates than would it is necessary to achieve price stability alone. In this way, using the interest rate to contain asset price growth would be regularly lead to deviations from the interest rate path that would be optimally justified by the pursuit of the price stability mandate.