Submitted:

14 January 2024

Posted:

15 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The International Healthcare Management Report:

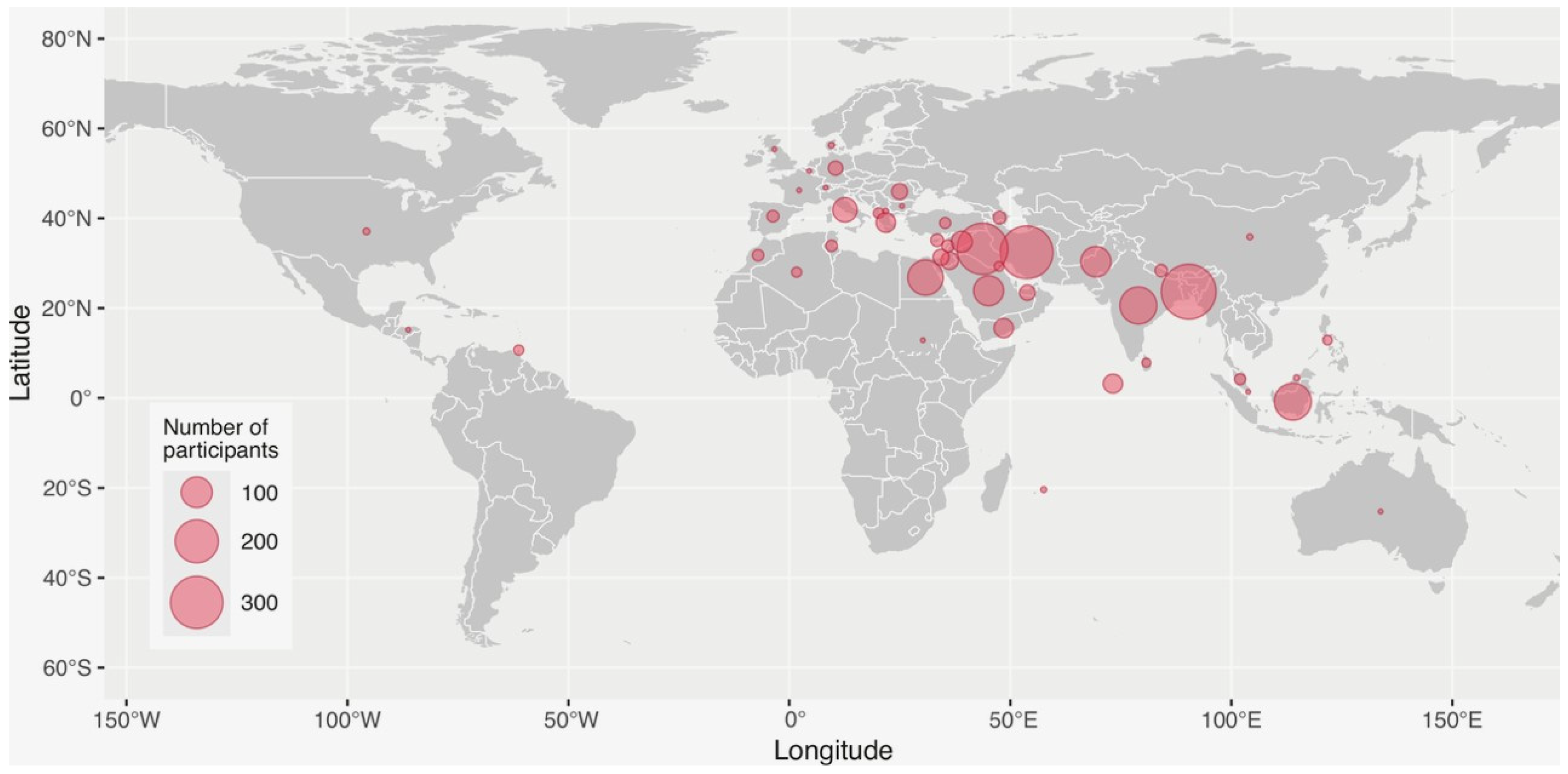

2.2. The International Thalassaemia Collaborative Assessment Patient survey:

2.2.1. Data collection instrument:

2.2.2. Survey translation, informed consent and deployment:

2.2.3. Data Management – Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Starfield, B. Basic concepts in population health and health care. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001, 55(7), 452-454. [CrossRef]

- Meisnere, M.; South-Paul, J.; Krist, A.H. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Transforming Health Care to Create Whole Health: Strategies to Assess, Scale, and Spread the Whole Person Approach to Health; Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 15 February 2023. [CrossRef]

- Altare, C.; Weiss, W.; Ramadan, M.; Tappis, H.; Spiegel, P.B. Measuring results of humanitarian action: adapting public health indicators to different contexts. Confl Health 2022, 16(1), 54. Published 2022 Oct 14. [CrossRef]

- B. Modell and M. Darlison, “Global epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders and derived service indicators,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2008, vol. 86,no. 6, pp. 480–487.

- WHO (World Health Organization). Noncommunicable diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- B. Modell, M. Darlison, H. Birgens et al., “Epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders in Europe: an overview,” Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation, 2007, vol. 67, no. 1, pp. 39–69. [CrossRef]

- M. Angastiniotis and B. Modell, “Global epidemiology of hemoglobin disorders,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1998, vol. 850, pp. 251–269.

- Modell’s Haemoglobinopathologist’s Almanac, Global epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders (thalassaemias and sickle cell disorders). Available online: http://www.modell-almanac.net/ (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention). Healthy Leaving with Thalassemia. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/thalassemia/living.html (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Thuret, I.; Pondarré, C.; Loundou, A.; Steschenko, D.; Girot, R.; Bachir, D.; Rose, C.; Barlogis, V.; Donadieu, J.; de Montalembert, M.; Hagege, I.; Pegourie, B.; Berger, C.; Micheau, M.; Bernaudin, F.; Leblanc, T.; Lutz, L.; Galactéros, F.; Siméoni, M. C.; Badens, C. Complications and treatment of patients with β-thalassemia in France: results of the National Registry. Haematologica 2010, 95(5), 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, M.D., Farmakis, D., Porter, J. Taher, A. et al., Guidelines for the Management of Transfusion Dependent Thalassaemia, Thalassaemia International Federation, Nicosia, Cyprus, 4th edition, 2024 (https://thalassaemia.org.cy/el/publications/tif-publications/guidelines-for-the-management-of-transfusion-dependent-thalassaemia-4th-edition-2021-v2/).

- Xuemei Zhen, Jing Ming, Runqi Zhang, Shuo Zhang, Jing Xie, Baoguo Liu, Zijing Wang, Xiaojie Sun, Lizheng Shi. Economic burden of adult patients with β-thalassaemia major in mainland China. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023 Aug 29;18(1):252. [CrossRef]

- Bin Hashim Halim-Fikri, Carsten W Lederer, et al. Global Globin Network Consensus Paper: Classification and Stratified Roadmaps for Improved Thalassaemia Care and Prevention in 32 Countries. J Pers Med. 2022 Mar 31;12(4):552. [CrossRef]

- Xenya Kantaris, Mark Shevlin, John Porter, Lynn Myers. Development of the Thalassaemia Adult Life Index (ThALI). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020 Jun 12;18(1):180. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.; Davies, J.K.; Pelikan, J.; Group, E.T.W. The EUHPID Health Development Model for the classification of public health indicators. Health Promot Int 2006, 21, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Lopez, A.D. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet, 1997; 349, 1436–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. H. Tulchinsky and E. A. Varavikova, "Measuring, Monitoring, and Evaluating the Health of a Population," The New Public Health, 2014 pp. 91-147, 2014. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2016 DALYs and HALE Collaborators, "Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016," Lancet, 2017 vol. 390, no. 10106, p. e38, 2017.

- World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators. Accessed 2023.

- The World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator. Accessed 2023.

- Farrukh T Shah, Farzana Sayani, Sara Trompeter, Emma Drasar, Antonio Piga. Challenges of blood transfusions in β-thalassemia. Βlood Rev. 2019 Sep:37:100588. [CrossRef]

- Sheila A Fisher, Susan J Brunskill, Carolyn Doree, Onima Chowdhury, Sarah Gooding, David J Roberts. Oral deferiprone for iron chelation in people with thalassaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Aug 21:(8):CD004839. [CrossRef]

- Antonis Kattamis, Ersi Voskaridou, et al. Real-world complication burden and disease management paradigms in transfusion-related β-thalassaemia in Greece: Results from ULYSSES, an epidemiological, multicentre, retrospective cross-sectional study. EJHaem. 2023 May 23;4(3):569-581. [CrossRef]

- Thalassaemia International Federation. https://thalassaemia.org.cy/el/home-new-2/.

- Dimitrios Farmakis, John Porter, Ali Taher, Maria Domenica Cappellini, Michael Angastiniotis, and Androulla Eleftheriou, for the 2021 TIF Guidelines Taskforce. 2021 Thalassaemia International Federation Guidelines for the Management of Transfusion-dependent Thalassemia. Hemasphere. 2022 Aug; 6(8): e732. Published online 2022 Jul 29. [CrossRef]

- Thalassaemia International Federation. The THALassaemia In Action (THALIA) project. https://thalassaemia.org.cy/el/news/tif-news/thalassaemia-in-action-the-thalia-project-2/.

| A/A | Country |

Population (millions) |

Infant mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | Life expectancy |

GDP (current US$) (billions) |

GDP per capita (current US$) | Government expenditure on education, total (% of GDP) | Current health expenditure (% of GDP) | World Bank income rank | Expected Thal. Births / 1000 live births (est from carrier rate) |

| EUROPE | ||||||||||

| 1. | Albania | 2.8 | 8.41 | 78 | 18.9 | 6,803 | 3.1 | 6.66 | Upper/mid income | 0.625/1000 |

| 2. | Belgium | 11.3 | 3.0 | 82.46 | 579 | 51166 | 6.2 | 11.6 | High income | 0.002/1000 |

| 3. | Bulgaria | 6.7 | 5 | 72.8 | 89 | 13773 | 4.5 | 8.52 | High income | 0.152/1000 |

| 4. | Cyprus | 1.26 | 2 | 82 | 28.4 | 31284 | 5.6 | 8.1 | High income | 4.9/1000 |

| 5. | Denmark | 5.9 | 3 | 82 | 395 | 68037 | 6 | 10.58 | High income | 0 |

| 6. | France | 64.7 | 3 | 83.35 | 278.3 | 40964 | 5.2 | 12.21 | High income | 0.0016/1000 |

| 7. | Germany | 83.3 | 3 | 82.18 | 407.2 | 51073 | 4.5 | 12.81 | High income | 0.0017/1000 |

| 8. | Greece | 10.3 | 3 | 82 | 219 | 20732 | 4.1 | 9.51 | High income | 1.64/1000 |

| 9. | Italy | 58.8 | 2 | 84.2 | 201 | 34158 | 4.1 | 9.45 | High income | 0.462/1000 |

| 10. | Romania | 19.9 | 5 | 75.14 | 301 | 15892 | 3.3 | 6.27 | High income | 0.025/1000 |

| 11. | North Macedonia | 2.1 | 4.65 | 75 | 13.6 | 6,591 | 3.3 | 7.89 | Upper/mid income | 0.169/1000 |

| 12. | Spain | 47.5 | 3 | 84.0 | 139.8 | 29350 | 4.6 | 10.71 | High income | 0.067/1000 |

| 13. | Switzerland | 8.8 | 3 | 84.4 | 808 | 93525 | 5.0 | 11.8 | High income | 0.004/1000 |

| 14. | Turkey | 85.8 | 8 | 78.7 | 906 | 10616 | 2.8 | 4.62 | Upper/mid income | 0.121/1000 |

| 15. | United Kingdom | 67.7 | 4 | 82.3 | 307 | 45850 | 5.3 | 11.94 | High Income | 0.0018/1000 |

| MIDDLE EAST | ||||||||||

| 16. | Yemen | 34.4 | 47 | 64.5 | nd | 702 | nd | 4.25 | Low/mid income | 0.484/1000 |

| 17 | Jordan | 11.3 | 12.56 | 75 | 47.5 | 4,204 | 3.2 | 7.47 | Upper/mid income | 0.306/1000 |

| 18. | Kuwait | 4.3 | 7.48 | 79 | 184.6 | 43,233 | 6.6 | 6.31 | High income | 0.121/1000 |

| 19. | Saudi Arabia | 36.4 | 5.75 | 78 | 1,108.1 | 30,436 | 7.8 | 5.54 | High income | 0.171/1000 |

| 20. | Lebanon | 5.5 | 7.05 | 76 | 23.1 | 4,136 | 1.7 | 7.95 | Upper/mid income | 0.132/1000 |

| 21. | Syria | 23.2 | nd | 76.3 | nd | 537 | nd | 3.0 | Low/mid income | 0.625 |

| 22. | Palestine (West Bank and Gaza) | 5.0 | 13 (world bank 2021) |

74.3 | 19.1 | 3,789 | 5.3 | - | Low/mid income | 0.4/1000 |

| 23. | United Arab Emirates | 9.4 | 5.45 | 80.4 | 507.5 | 53,757 | 3.9 | 5.67 | High income | 0.23/1000 |

| AFRICA | ||||||||||

| 24. | Algeria | 44.9 | 19.16 | 77.3 | 191.9 | 4,273 | 7.0 | 6.32 | Low/mid income | 0.1/1000 |

| 25. | Egypt | 111.0 | 16.23 | 70 | 476.7 | 4,295 | 2.5 | 4.36 | Low/mid income | 0.7/1000 |

| 26. | Mauritius | 1.3 | 15.31 | 75.7 | 12.9 | 10,216 | 4.9 | 6.66 | Upper/mid income | 0.37/1000 |

| 27. | Morocco | 37.5 | 15.42 | 74 | 134.2 | 3,527 | 6.8 | 5.99 | Low/mid income | 0.07/1000 |

| 28. | Tunisia | 12.4 | 14.03 | 76.9 | 46.7 | 3,776 | 7.3 | 6.34 | Low/mid income | 0.122/1000 |

| 29. | Sudan | 48.1 | 39 | 66.1 | 51.66 | 1.0 | 3.0 | Low/mid income | 0.38/1000 | |

| ASIA | ||||||||||

| 30 | Azerbaijan | 10.2 | 16.61 | 73.6 | 78.7 | 7,736 | 4.3 | 4.61 | Upper/mid income | 0.344/1000 |

| 31.. | Bangladesh | 171.2 | 22.91 | 73.9 | 460.2 | 2,688 | 2.1 | 2.63 | Low/mid income | 2.1/1000 |

| 32. | Brunei Darussalam | 0.45 | 10 | 74.5 | 16.7 | 37153 | 4.4 | 2.39 | High income | 0.47/1000 |

| 33. | China | 1,412.2 | 5.05 | 78 | 17,963.2 | 12,720 | 3.6 | 5.59 | Upper/mid income | 0.283/1000 (South only) |

| 34. | India | 1,417.2 | 25.49 | 67 | 3,385.1 | 2,388 | 4.5 | 2.96 | Low/mid income | 0.58/1000 |

| 35. | Indonesia | 275.5 | 18.88 | 68 | 1,319.1 | 4,788 | 3.5 | 3.41 | Low/mid income | 2.13/1000 |

| 36. | Iran | 88.6 | 10.87 | 76.9 | 388.5 | 4,387 | 3.6 | 5.34 | Upper/mid income | 0.576/100 |

| 37. | Iraq | 44.5 | 20.75 | 70 | 264.2 | 5,937 | 4.7 | 5.08 | Upper/mid income | 0.576/1000 |

| 38. | Malaysia | 33.9 | 6.46 | 75 | 406.3 | 11,971 | 3.9 | 4.12 | Upper/mid income | 0.377/1000 |

| 39. | Maldives | 0.52 | 5.10 | 81 | 6.2 | 11,817 | 5.8 | 11.35 | Upper/mid income | 8.9/1000 |

| 40. | Nepal | 30.5 | 22.82 | 68 | 40.8 | 1,336 | 4.2 | 5.17 | Low/mid income | 1.28/1000 |

| 41. | Pakistan | 235.8 | 52.78 | 66 | 376.5 | 1,596 | 2.4 | 2.95 | Low/mid income | 0.99/1000 |

| 42. | Philippines | 115.6 | 20.47 | 69 | 404.3 | 3,498 | 3.7 | 5.61 | Low/mid income | 0.024/1000 |

| 43. | Sri Lanka | 22.2 | 5.77 | 76 | 74.4 | 3,354 | 1.9 | 4.07 | Low/mid income | 0.18/1000 |

| 44. | Singapore | 6.0 | 2 | 84.27 | 467 | 82808 | 2.4 | 6.0 | High Income | 0.2/1000 |

| AMERICA | ||||||||||

| 45. | Honduras | 10.6 | 14 | 73.7 | 31.7 | 3040 | 5.4 | 9.1 | Low/mid income | 0.001/1000 |

| 46. | USA | 338.3 | 5 | 79.7 | 254.63 | 76399 | 5.4 | 18.82 | High Income | 0.004/1000 |

| 47. | Trinidad &Tobago | 1.5 | 14.60 | 73 | 27.9 | 18,222 | 4.1 | 7.31 | High income | 0.306/1000 |

| 48. | Australia | 26.4 | 3 | 83.73 | 362 | 64491 | 5.6 | 10.65 | High Income | 0.012/1000 |

| Study population | |

| n | 2082 |

| Age (in years) | |

| Mean, (SD) | 26.9 (12.6) |

| Missing (n, %) | 275 (13.3%) |

| Patient/Parent | |

| Patient (n, %) | 1465 (70.7%) |

| Parent (n, %) | 582 (28.1%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 24 (1.2%) |

| What is your gender? | |

| Male (n, %) | 877 (42.3%) |

| Female (n, %) | 1087 (52.5%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 107 (5.2%) |

| Which of the following categories best describes your employment status? | |

| Employed, working full-time (n, %) | 489 (23.6%) |

| Employed, working part-time (n, %) | 188 (9.1%) |

| Not employed, looking for work (n, %) | 528 (25.5%) |

| Not employed, NOT looking for work (n, %) | 517 (25.0%) |

| Retired (n, %) | 69 (3.3%) |

| Disabled, not able to work (n, %) | 232 (11.2%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 48 (2.3%) |

| Which of the following best describes your current relationship status | |

| Married (n, %) | 705 (34.0%) |

| Widowed (n, %) | 28 (1.4%) |

| Divorced (n, %) | 23 (1.1%) |

| Separated (n, %) | 24 (1.2%) |

| Cohabiting (n, %) | 664 (32.1%) |

| Single, never married (n, %) | 532 (25.7%) |

| Prefer not to answer (n, %) | 53 (2.6%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 42 (2.0%) |

| What is the highest level of school you have completed or the highest degree you have received? | |

| Less than high school degree | 478 (23.1%) |

| High school degree or equivalent (e.g., GED) | 456 (22.0%) |

| Some college but no degree | 161 (7.8%) |

| Bachelor degree | 497 (24.0%) |

| Master degree | 158 (7.6%) |

| Doctoral degree | 21 (1.0%) |

| Trade School | 35 (1.7%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 265 (12.8%) |

| If you are a patient, what is your diagnosis? If you are a parent, what is the diagnosis of your child? | |

| Other (n, %) | 274 (13.2%) |

| Beta Thalassaemia major (n, %) | 1510 (72.9%) |

| Beta Thalassaemia intermedia (n, %) | 250 (12.1%) |

| HbH disease (n, %) | 11 (0.5%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 26 (1.3%) |

| At what age did you start transfusion therapy? | |

| 1-4 years old (n, %) | 1647 (79.5%) |

| 5-6 years old (n, %) | 156 (7.5%) |

| 7-8 years old (n, %) | 61 (2.9%) |

| 9-10 years old (n, %) | 33 (1.6%) |

| Later (n, %) | 100 (4.8%) |

| I am not transfusion dependent (n, %) | 49 (2.4%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 25 (1.2%) |

| How is your current transfusion regime? | |

| I am not transfused (n, %) | 91 (4.4%) |

| I am regularly transfused (n, %) | 1779 (85.9%) |

| I am occasionally transfused (n, %) | 179 (8.6%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 22 (1.1%) |

| If regularly transfused, what is the usual Hb level pre-transfusion? | |

| Less than 7mg/dl (n, %) | 492 (23.8%) |

| 8-9mg/dl (n, %) | 970 (46.8%) |

| 10-11mg/dl (n, %) | 339 (16.4%) |

| Over 11mg/dl (n, %) | 165 (8.0%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 105 (5.1%) |

| Are blood supplies adequate at the centre you are transfused or are there delays in transfusion? | |

| No delays | 877 (42.3%) |

| Occasional delays | 973 (47.0%) |

| Delays are frequent so my Hb falls very low | 172 (8.3%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 49 (2.4%) |

| What kind of blood filtration is available at the clinic? | |

| Pre-storage | 367 (17.7%) |

| Bedside | 534 (25.8%) |

| None | 253 (12.2%) |

| I don't know | 855 (41.3%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 62 (3.0%) |

| At what age did you start receiving iron chelation therapy? | |

| 1-4 years old (n, %) | 885 (42.7%) |

| 5-6 years old (n, %) | 370 (17.9%) |

| 7-8 years old (n, %) | 196 (9.5%) |

| 9-10 years old (n, %) | 176 (8.5%) |

| Later (n, %) | 359 (17.3%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 85 (4.1%) |

| What chelation drugs do you use? | |

| Desferrioxamine (Desferal) | 469 (22.6%) |

| Deferiprone (Ferriprox / L1) | 274 (13.2%) |

| Deferasirox (Exjade) | 694 (33.5%) |

| Combination | 506 (24.4%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 128 (6.2%) |

| How often do you receive chelation? | |

| I take it regularly as prescribed | 1470 (71.0%) |

| I do not take it regularly | 372 (18.0%) |

| I don't receive iron chelation therapy | 176 (8.5%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 53 (2.6%) |

| How available are iron chelation drugs to you and at what dose? | |

| I always receive the chelation drugs in the quantity that I need them (at the right dose, continuous availability) | 1243 (60.0%) |

| I receive a lower dose of chelation drugs than prescribed because of there isn't enough quantity (poor supplies) | 377 (18.2%) |

| I receive chelation drugs but not all the time because of interruptions in supply | 328 (15.8%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 123 (5.9%) |

| How often is your ferritin level measured? | |

| Every month | 161 (7.8%) |

| Every two months | 110 (5.3%) |

| Every three months | 646 (31.2%) |

| Every six months | 819 (39.5%) |

| Every twelve months | 194 (9.4%) |

| Never | 86 (4.2%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 55 (2.7%) |

| Your current ferritin level is: | |

| <500ng/ml | 213 (10.3%) |

| 501-1000ng/ml | 325 (15.7%) |

| 1001-2000ng/ml | 446 (21.5%) |

| 2001-4000ng/ml | 444 (21.4%) |

| >4001ng/ml | 362 (17.5%) |

| I don't know | 236 (11.4%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 45 (2.2%) |

| How often is cardiac iron measured by T2*? | |

| Twice a year | 131 (6.3%) |

| Annually/ Every year | 429 (20.7%) |

| Every 2 years | 175 (8.5%) |

| Rarely | 359 (17.3%) |

| Never | 909 (43.9%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 68 (3.3%) |

| What is your latest T2* level? | |

| Under 6ms | 345 (16.7%) |

| 7-10ms | 357 (17.2%) |

| 11-20ms | 166 (8.0%) |

| Over 20ms | 211 (10.2%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 992 (47.9%) |

| How is your liver iron measured? | |

| Liver biopsy | 67 (3.2%) |

| MRI | 701 (33.8%) |

| Not measured at all | 1195 (57.7%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 108 (5.2%) |

| What is your latest Liver Iron Concentration? | |

| Less than 7 mg/kg of dry weight | 132 (6.4%) |

| 8-15 mg/kg of dry weight | 89 (4.3%) |

| Above 16 mg/kg of dry weight | 49 (2.4%) |

| I am not sure | 330 (15.9%) |

| I don't know | 1355 (65.4%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 116 (5.6%) |

| If paying out of pocket, which services are you paying for? (Tick all that apply) | |

| Transfusion | 718 |

| Chelation pumps | 308 |

| Chelation drugs | 822 |

| Lab tests | 1064 |

| MRI | 525 |

| Hospitalisation | 513 |

| Multidisciplinary Care* | 603 |

| None answer (n, %) | 377 (18.2%) |

| Who pays for your treatment? (Tick all that apply) | |

| Myself/my family | 1245 |

| Health insurance (private): mine | 194 |

| Health insurance (private): my employer's | 97 |

| State-provided free healthcare | 563 |

| State-provided, partly free | 335 |

| Other | 317 |

| None answer (n, %) | 58 (2.8%) |

| What specialist(s) do you visit, in addition to your main treating doctor? | |

| Heart specialist | 776 |

| Endocrinologist | 572 |

| Diabetologist (If separate from endocrinologist) | 225 |

| Psychologist | 142 |

| Liver specialist | 368 |

| Nephrologist | 182 |

| None answer (n, %) | 785 (37.9%) |

| Where are you transfused? | |

| Haematology ward | 518 |

| Children’s ward | 181 |

| Transfusion centres | 1238 |

| Other | 219 |

| None answer (n, %) | 62 (3.0%) |

| Are you satisfied with the quality and type of services you are receiving? | |

| Very unsatisfied (n, %) | 288 (13.9%) |

| Unsatisfied (n, %) | 340 (16.4%) |

| Neutral (n, %) | 412 (19.9%) |

| Satisfied (n, %) | 783 (37.8%) |

| Very satisfied (n, %) | 220 (10.6%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 28 (1.4%) |

| How would you rate access to your treatment? | |

| Very difficult (n, %) | 289 (14.0%) |

| Difficult (n, %) | 471 (22.7%) |

| Neutral (n, %) | 604 (29.2%) |

| Easy (n, %) | 549 (26.5%) |

| Very easy (n, %) | 121 (5.8%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 37 (1.8%) |

| If your answer to the previous question was "Very difficult" or "Difficult" please indicate why: | |

| High cost of travel to treating center | 322 (15.5%) |

| High cost of treatment | 348 (16.8%) |

| High cost of both travel to the treating centre and treatment | 358 (17.3%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 1043 (50.4%) |

| How many days per year do you lose from education or work because of having to attend treatment for thalassaemia? | |

| None | 383 (18.5%) |

| 1-5 days | 296 (14.3%) |

| 6-10 days | 111 (5.4%) |

| 11-15 days | 387 (18.7%) |

| 16 or more days | 778 (37.6%) |

| Missing (n, %) | 116 (5.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).