Introduction

The intersection of race and disability is a crucial area of inquiry amidst the various factors contributing to health disparities. Health disparities, defined as differences in disease incidence, prevalence, mortality, and severity among minority populations (Braveman, 2014), have long been a source of concern in the United States and around the world. In contrast, a disability refers to a condition of the body or mind (impairment) that hinders the individual from performing specific activities (activity limitation) and engaging with their surrounding environment (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). This encompasses any circumstance that makes it more challenging for a person with such a condition to carry out tasks and participate in various aspects of life. A growing body of research has consistently highlighted that individuals with disabilities represent one of the most substantial and underserved segments in the United States, encompassing over 54 million Americans (Drum et al., 2011; Lennox & Kerr, 2007). Substantial evidence indicates variations in the occurrence, frequency, mortality rates, and disease burden when comparing individuals with disabilities to those without. Additionally, disparities in the accessibility, quality, and outcomes of health services have been identified between these two groups (Meade, Mahmoudi, & Lee, 2015). While disability affects a significant portion of the US population, factors like lower socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, language, age and educational background can exacerbate the consequences of disabilities, leading to further declines in both health and overall well-being (CDC, 2008). In the US, racialized minority groups are more susceptible to disability. For example, in the 45-64 age range, 35.5% of Black and Hispanic individuals reported living with a disability, compared to 26.6% of white adults (Holliman et al., 2023).

The intersection of racial identity and disability status among racialized groups remains a relatively understudied area within the broader realm of health disparities (Courtney-Long et al., 2017). To fill this gap, this paper examines how race and disability converge and impact health outcomes, gaining a deeper understanding of the challenges faced by individuals at this intersection. Identifying specific intersections will guide more targeted interventions, addressing the unique needs of individuals navigating both racialized and disabled identities (Babik &

Gardner, 2021). To begin, we highlight the meaning of disability, explaining how different models (for instance, medical, social, and biopsychosocial models) can be used to elucidate the term. Then, we discuss the relationship between disability and health disparities, followed by the assessment of the intersectionality of race, disability, and health disparities. I also extensively explore social determinants of health. The purpose of examining these determinants is to elucidate how various conditions exacerbate health disparities among racialized groups who also experience disabilities. Additionally, we discuss intersectionality perspectives that can help explain these disparities. This is followed by directions for future research and policy and then a conclusion.

Meaning of Disability

A disability is defined as any mental or physical impairment that hinders a person's participation in social situations and everyday activities within their community (Babik & Gardner, 2021). To provide a clearer understanding of disability, conceptual models such as the medical and social models can be utilized (Bianco & Sheppard-Jones, 2008; Babik & Gardner, 2021). According to the medical model, an individual's impairment is considered a natural characteristic resulting from illnesses, injuries, diseases, or other health-related issues. This model focuses on "fixing" the patient's condition through medical therapy or interventions (Bingham et al., 2013; Babik & Gardner, 2021). In contrast, the social model offers an alternative viewpoint, viewing disability as a problem created by society rather than the individual. It contends that people with disabilities are disabled by societal barriers, including inaccessible buildings, discriminatory attitudes, and social exclusion (Bingham et al., 2013; Babik & Gardner, 2021).

However, defining disability solely through the social and medical models may not sufficiently capture the complexity of the concept. Consequently, adopting a third, more comprehensive model is crucial. The biopsychosocial model, conceptualized by George Engel in 1977, sees disability as an outcome of not only medical conditions (biological) but also psychological and social factors, encompassing environmental barriers and societal attitudes. This broader perspective recognizes the role of individual experiences, attitudes, and societal structures in understanding and addressing disability (Gatchel et al., 2007). Moreover, a variety of factors can influence how a person with a disability functions in society and how they are perceived by others. These variables include the type and extent of the impairment, the individual's personality characteristics, the availability of suitable environmental modifications, financial situation, degree of social inclusion activities, and the attitudes and actions of their parents (Babik & Gardner, 2021).

Disability and Health Disparities

Individuals with disabilities face considerable health disparities, characterized by elevated rates of chronic diseases, constrained healthcare access and reduced life expectancy (Meade, Mahmoudi, & Lee, 2015). Beyond the healthcare domain, individuals with disabilities often confront exclusion and bias in areas such as education and employment, leading to feelings of isolation, perpetual diminished self-esteem, and adverse impacts on mental well-being. Additionally, disabled people relatively exhibit higher rates of obesity, increased smoking, decreased physical activity and cardiovascular diseases, which rates three to four times greater than those without disabilities (Reichard et al., 2011). The high cost of healthcare becomes even more burdensome for individuals with disabilities. Expensive assistive technology, specialized care, and inadequate insurance coverage create a financial strain, often forcing individuals to choose between their health and other necessities. This lack of financial resources restricts access to preventative care, timely diagnoses, and quality treatment, exacerbating existing health inequalities. (Krahn et al., 2015). In essence, living with a disability significantly shapes one's interactions with economic, social, and environmental determinants of health. Expensive assistive technology, specialized care, and inadequate insurance coverage create a financial strain, often forcing individuals to choose between their health and other necessities (Reichard et al., 2011). This lack of financial resources restricts access to preventative care, timely diagnoses, and quality treatment, exacerbating existing health inequalities (Krahn et al., 2015).

The obstacles associated with disability extend to healthcare access and navigation within the healthcare system (WHO, 2022). In 2009, individuals with disabilities, regardless of health insurance coverage, were more than twice as likely as those without disabilities to forego medical care due to cost (CDC, 2016). Addressing these multifaceted challenges is imperative for fostering a more inclusive and equitable healthcare landscape for individuals with disabilities.

Figure 1 illustrates various outcomes among people with disabilities in comparison to those without disabilities. The percentages in the graph represent the prevalence of specific circumstances for adults aged 18-64 in the United States. Across different categories such as unemployment, victimization of violent crime, cardiovascular disease, obesity, smoking, lack of leisure-time physical activity, absence of a current mammogram, inability to access needed medical care due to cost, and absence of leisure-time physical activity, people with disabilities are more likely to experience negative outcomes. For instance, the graph highlights that 15.0% of individuals with disabilities are unemployed, compared to 8.7% among those without disabilities. Similarly, 32.4% of people with disabilities have been victims of violent crime, in contrast to 21.3% of those without disabilities. The data emphasizes the disparities in these areas, underscoring the challenges and increased likelihood of adverse situations for individuals with disabilities.

Intersectionality: Race, Disability and Health Disparities

The concept of intersectionality, introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw in the late 1980s, highlights the complex interplay between social identities and how they interact to influence an individual's experiences of discrimination and marginalization. Race and disability are often perceived as distinct and independent categories, but they are deeply intertwined and mutually reinforcing.

Due to the combined consequences of ableism and racism, members of racial and ethnic minority groups who are disabled experience double burdens of discrimination. (Crenshaw, 1989). People with disabilities, particularly those from minority groups, have higher rates of obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, and cardiovascular disease three to four times higher than those without disabilities (Reichard, Stolzle, & Fox, 2011; Reichard & Stolzle, 2011). People with disabilities had fewer pleasant experiences across a wide range of outcomes, including health status, health related behaviors, and concerns such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, according to the findings. Furthermore, research shows that people with disabilities are more likely to have unmet healthcare needs and use less medical services linked to preventative care and health maintenance (Iezzoni, 2009; Meade, Mahmoudi, & Lee, 2015).

Racialized individuals with disabilities encounter health inequalities as a result of the convergence of their racial and disabled identities (Paradies, Harris-Kojetin, & Beatty, 2018).

These disparities are worsened by the presence of systemic racism and ableism within society. For instance, Black individuals experiencing disabilities are at a greater risk of residing in impoverished conditions, lacking access to nutritious food and secure environments for physical activity, and facing discrimination within healthcare settings when compared to their white counterparts with disabilities (Mitra et al., 2022). Consequently, this group is more prone to developing preventable health issues and experiencing premature mortality.

A study conducted by Brown and Leigh (2009) discovered that when compared to White with disabilities, Black individuals with disabilities are more likely to be uninsured or underinsured. In addition, they are more likely to self-report having unhealthy conditions and to have diseases like diabetes and obesity that may be avoided. Crutchfield and Mizuno (2014) found that while black individuals with disabilities are more likely to report instances of discrimination in healthcare settings, they are less likely than white individuals with disabilities to receive preventative healthcare services.

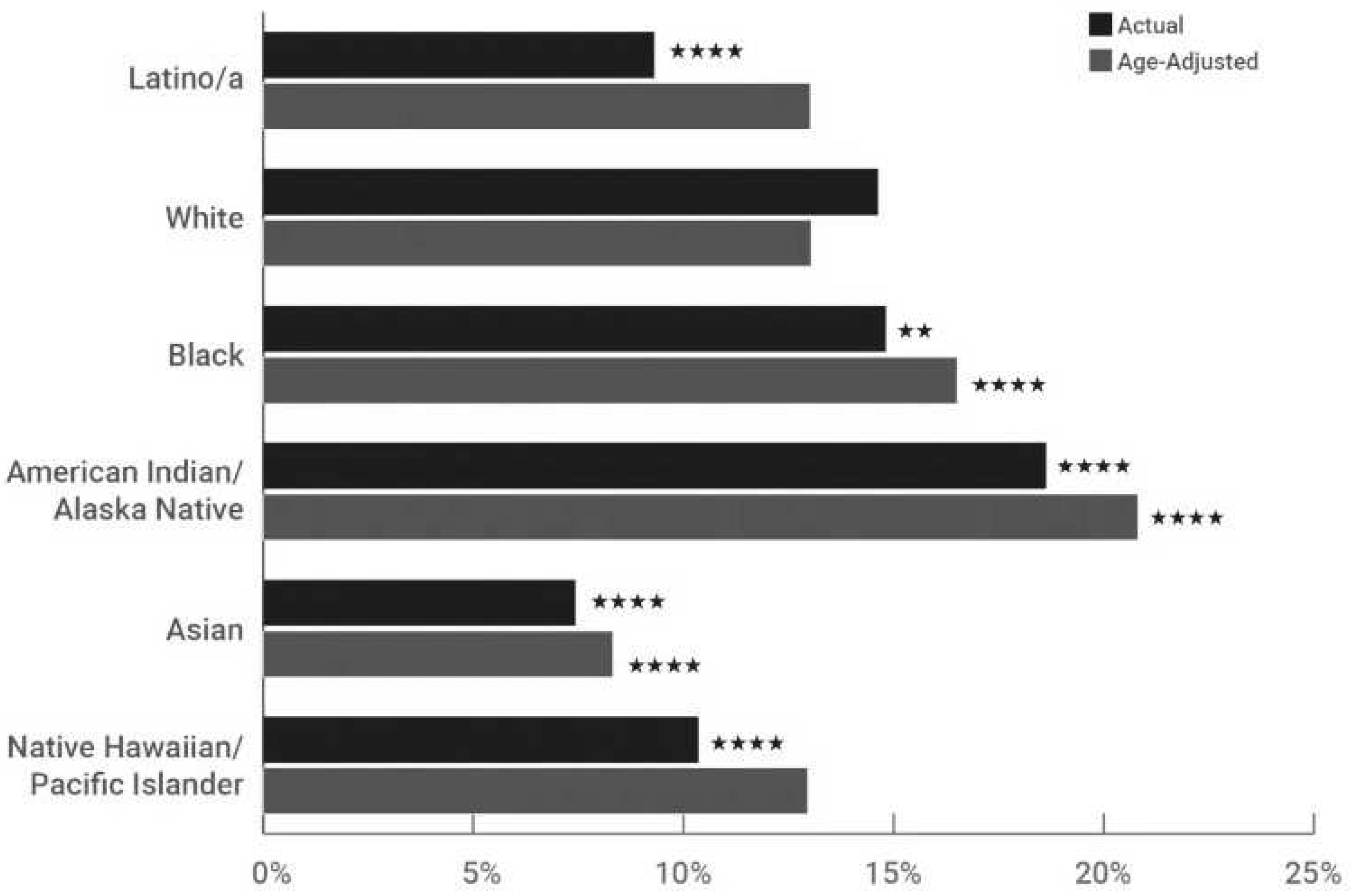

Figure 2 which is based on data from the American Community Survey in 2019 and analyzed by Mitra et al. (2022), provides insights into disability prevalence across different racial and ethnic groups.

The age-adjusted rates were calculated by applying disability prevalence within specific 5-year age brackets for each racial and ethnic group to the overall age distribution of the population. It's important to note that all race categories presented are non-Latino/a. The "p values" mentioned in the graph indicate the statistical significance of disparities in disability prevalence both actual and age-adjusted between the White population and other racial and ethnic groups. The levels of significance are denoted as **p<0.05 and ****p<0.001. The findings reveal variations in disability prevalence among racial and ethnic groups. The highest rates are observed among American Indian/Alaska Native populations, while the lowest rates are found among Asian populations. Black populations show a slightly higher disability prevalence compared to White populations, and this difference becomes more pronounced with age adjustment. Initially, the unadjusted disability prevalence is notably lower among Latino/a populations and Native. Hawaiian/Pacific Islander populations compared to White populations, but these differences diminish in the age-adjusted data. The significance of considering disability prevalence within various racial and ethnic groups cannot be emphasized. Researchers should delve into the reasons behind the observed disparities, exploring potential contributing factors rooted in social, economic, and environmental contexts. The combination of race and disability in the setting of health disparities necessitates significant policy and practice ramifications (Ferris et al., 2021).

Social Determinants of Health: Race, Disability and Health Disparities

There is a body of evidence that underlines the critical role of social determinants of health (SDOH) in shaping health outcomes across various indicators, settings, and populations. This perspective highlights that health is not solely determined by medical care but is profoundly influenced by the conditions under which individuals are born, develop, work, live, and age (Bingham et al., 2013). The broader set of influences and institutions that shape everyday life, collectively known as social determinants, plays a significant role in overall health (WHO, 2022). This understanding is particularly relevant when considering racial disparities in health outcomes. Individuals with disabilities, like the general population, are subject to the impact of social determinants on health and well-being. However, the existence of a disability can introduce additional challenges, depending on the nature of the disability and associated underlying health conditions (Yee et al., 2016). In the context of racial disparities, the social determinants paradigm becomes even more pertinent. It acknowledges that minority populations, including individuals with disabilities, may face unique challenges and obstacles rooted in social, economic, and environmental factors. The social determinants perspective allows researchers and policymakers to explore how systemic issues, discriminatory practices, and unequal access to resources contribute to health disparities among specific racial and ethnic groups.

Economic Instability

Poverty

Individuals with disabilities from a range of ethnic and racial backgrounds, including Latinos, African Americans, and Native Americans, face a greater likelihood of residing in poverty compared to White individuals with disabilities (Suarez-Balcazar et al., 2013). This is a triple burdens and the intersection of ethnic and racial backgrounds with disabilities elevates the susceptibility to job discrimination compared to Whites with disabilities. Additionally, individuals from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds with disabilities exhibit lower likelihoods of having completed secondary or post-secondary education (Suarez-Balcazar et al., 2013). Moreover, they are more frequently subject to marginalization from the social and economic dynamics of the broader community, as observed by Wilson and Senices (2010). In the same line, according to Yee et al. (2016), racialized inidividuals with disabilities face a much greater risk of living in poverty than their peers without. The income eligibility criteria for disability services such as Medicaid can trap individuals in poverty, as they may lose access to these essential services if their income exceeds the limit (Yee et al., 2016). This situation creates an unfortunate paradox where individuals must remain impoverished to maintain access to critical support.

Employment

Securing employment is a critical first step, giving individuals with a feeling of purpose, identity, greater money, social connections, and access to many important resources, including the Internet (Yee et al., 2016). However, the work picture for persons with disabilities, particularly those from racialized groups, displays major discrepancies. African Americans with disabilities experience an employment rate of approximately 29%, significantly lower than other surveyed racial and ethnic groups. Additionally, individuals with disabilities earn an average of $5,000 less annually than those without disabilities, resulting in a poverty rate for the former more than double that of the latter (Suarez-Balcazar et al., 2013). Research reveals disparities in employment rates and job opportunities among various racial and ethnic groups, particularly when individuals also have disabilities. Minority communities, including African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans, often face higher unemployment rates and lower employment participation rates when compared to the majority population (Mitra et al., 2022). When disability is factored into the equation, these disparities can become more pronounced. People with disabilities from racial minority groups may encounter additional barriers to securing employment, including discrimination, lack of accommodations, and limited access to educational and vocational resources (Mitra et al., 2022).

Food Insecurity

A disability is a substantial risk factor for food insecurity, which is defined as a lack of consistent access to inexpensive, nutritious food (Coleman-Jensen & Nord, 2013). In 2009-2010, households where a working-age adult was unable to work due to a disability had a higher occurrence of food insecurity, affecting one-third of them. Even when disabilities did not preclude working-age persons from working, one-quarter of households reported food insecurity (Yee et al., 2016). In comparison, food insecurity affected only 12% of homes without a working-age adult with any disability status. Individuals with disabilities are not only more vulnerable to food insecurity, but they also confront more severe cases defined by altered eating patterns and lower food intake. These difficulties are exacerbated by the fact that people with mobility, cognitive, or visual limitations may find healthy food purchasing and preparation more difficult (Coleman-Jensen & Nord, 2013).

Housing

Inadequate and expensive housing significantly impacts the health of both people of color and individuals with disabilities, increasing their vulnerability to housing insecurity and homelessness (Jacobs, 2011; DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, 2014). Health issues are often linked to housing disparities, limited housing options, and housing discrimination (Fremstad, 2009). Even when considering income, individuals with disabilities are more likely to live in substandard housing with health risks like pests, structural damage, or rodent infestations (United States Senate HELP, 2014). Henry et al. (2015) revealed that among those experiencing homelessness in 2015, 16.5% identified as Hispanic or Latino, and 35.5% identified as African American. Accessible housing is crucial for individuals with disabilities, but it is limited and often found in newer, more expensive buildings. For many low-income individuals with disabilities, the cost of adapting a residence to be more accessible is a significant barrier (Fremstad, 2009). Over the past two decades, there has been minimal growth in affordable housing, resulting in a critical shortage, extensive waiting lists, and a limited supply of units. The scarcity of affordable and accessible housing poses a major obstacle to community living for individuals who are currently residing in expensive nursing homes or other institutional settings (Haider et al., 2015).

Social and Community Context

Social Cohesion and Discrimination

Individuals with disabilities often face unique challenges that set them apart within their family and social circles. Unlike shared qualities such as color, ethnicity, and language, disabilityrelated restrictions can make them feel isolated, lacking a common bond with their immediate community (Taylor, Krane, & Orkis, 2010). This isolation manifests in reduced opportunities for regular interactions with family and friends, and a significantly lower likelihood of dining out at restaurants. For instance, individuals with disabilities (32%) are less likely to report dining out at least twice a month compared to those with minor (55%) or moderate (66%) disabilities (NOD, 2010). Discrimination against people with disabilities has been a persistent issue in U.S. history, especially in the institutionalization of those with severe disabilities. Despite the enactment of various legislative measures aimed at reducing discrimination and segregation based on disability, allegations of mistreatment persist, posing a significant challenge in the daily lives of individuals with disabilities. Notably, a considerable percentage of people with disabilities (43%) report experiencing some form of employment discrimination throughout their lives (Taylor, Krane, & Orkis, 2010). While disability-related restrictions may set individuals apart within their family and social circles, the impact is compounded for those who also face racial disparities. For individuals with disabilities from marginalized racial or ethnic backgrounds, the sense of isolation can be further intensified (Yee et al., 2016).

Incarceration

According to a 2011-2012 survey by the Department of Justice (DOJ), approximately 30% of state and federal prisoners, as well as 40% of local jail detainees, reported having one or more disabilities. Cognitive disabilities were the most frequently mentioned, and they were linked to higher rates of serious psychological distress. Notably, non-Hispanic white prisoners (37%) and those of two or more races (42%) were more likely to report a disability compared to African American/black convicts (26%) (Bronson, Maruschak, & Berzofsky, 2015; Yee et al., 2016). Recently, there has been increased attention to the challenges faced by incarcerated individuals with disabilities. These challenges include consistent neglect of the emotional or physical needs of inmates, unequal access to facility programs and activities, and insufficient communication resources for inmates with hearing or visual impairments (Bronson, Maruschak, & Berzofsky, 2015).

Neighborhood and Built Environment

Safety and Transportation

Individuals who are disabled and who require specific healthcare needs are just as likely as individuals without disabilities to reside in safe neighborhoods, according to the Data Resource Center for C&A Health (2011/12). However, in 2013, crimes targeting people especially those belonging to minority racial/ethnic groups with disabilities were more than twice as prevalent as those against people without disabilities (36 per 1,000 versus 14 per 1,000). Notably, 51% of the victims had various disabilities, and the crimes included rape or sexual assault, robbery, severe assaults, and simple assaults. Violent crime rates against people with disabilities were higher for white individuals (38 per 1,000) and African Americans/Black individuals (31 per 1,000) compared to people of other races (15 per 1,000) (Yee et al., 2016). Additionally, transportation is often essential for accessing services, work, entertainment, and community involvement. However, individuals with disabilities are more than twice as likely (34% versus 16%) to identify transportation as a significant barrier (Taylor, Krane, & Orkis, 2010). According to a 2003 study conducted by the United States Department of Mobility, over 560,000 people with disabilities reported never leaving their homes due to mobility issues (Yee et al., 2016).

Healthcare and Quality

Healthcare includes health coverage, the presence of healthcare providers, and the quality of health services. It's important to recognize that the accessibility of healthcare services greatly influences overall health. Factors like where you live, lack of health insurance, and financial limitations can significantly impact your ability to get timely and adequate medical care. People with disabilities often face worse health outcomes, and many of these negative effects could be prevented (Artiga, 2018). Obesity rates among youth and adults with disabilities are 58% and 38% higher, respectively, compared to their non-disabled counterparts. Additionally, adults with disabilities experience almost three times as many new cases of diabetes annually compared to those without disabilities (19.1 per 1,000 versus 6.8 per 1,000). Disability status is a significant risk factor for the early onset of cardiovascular disease, with rates of 12% compared to 3.4% among 18 to 44-year-olds with and without disabilities. Moreover, individuals with disabilities are significantly more likely to develop cardiovascular disease not only in their later years but even during their adolescence (Krahn et al., 2015).

Intersectionality Perspective

Intersectionality theory, introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989), provides a comprehensive framework for examining the intricate health disparities experienced by racialized minority groups with disabilities. This theory asserts that racism and ableism do not operate independently but intersect, resulting in unique forms of discrimination for individuals embodying multiple marginalized identities (Crenshaw, 1989; Hancock, 2007). Through this perspective, the challenges faced by racialized minorities with disabilities become evident, exposing a scenario of heightened rates of chronic illnesses, lower life expectancy, and inadequate healthcare access (National Disability Rights Network, 2020). Analyzing health disparities through an intersectional perspective reveals specific challenges in healthcare access.

Racialized minorities with disabilities are more likely to encounter racism and ableism from healthcare providers, leading to misdiagnoses, inadequate treatment, and delayed diagnoses, resulting in poorer health outcomes and increased chronic disease burdens (Courtney-Long et al., 2017). Distinct groups within this intersectional space face unique barriers; for example, Black women with disabilities may lack culturally competent care, while Latinx men with disabilities might struggle with language access and transportation issues (National Disability Rights Network, 2020). Further, Social determinants of health (SDOH), such as income, education, and housing, significantly influence health outcomes. Racialized minorities with disabilities experience the intersection of these determinants, creating a reinforcing web of disadvantage that exacerbates health disparities (Braveman et al., 2011). Tackling these broader societal issues is pivotal for lasting change. The voices of individuals at the intersection of race and disability often go unheard in disability and racial justice movements. This invisibility contributes to their underrepresentation in policy discussions and healthcare decision-making, perpetuating existing disparities and impeding progress (Varadaraj et al., 2021). Recognizing power dynamics is essential for dismantling health disparities, necessitating an acknowledgment of how dominant groups benefit from the marginalization of others and the challenge of existing structures of power and privilege (Hancock, 2007). In essence, an intersectional approach illuminates the complex interplay of race and disability, offering essential insights for developing comprehensive strategies to address health disparities within these marginalized communities.

Conclusion

In exploring the intersection of race and disability and its impact on health outcomes, it becomes evident that individuals at this intersection face unique challenges that contribute to health disparities (Braveman, 2014). The paper has discussed the meaning of disability through various models, emphasizing the importance of adopting a comprehensive biopsychosocial perspective (Gatchel et al., 2007).

Subsequently, it has highlighted the substantial health disparities faced by individuals with disabilities, encompassing increased rates of chronic illnesses, limited access to healthcare, and various socioeconomic challenges (Meade, Mahmoudi, & Lee, 2015). Moving into the intersectionality of race, disability, and health disparities, the study has shed light on the compounded effects of ableism and racism (Crenshaw, 1989). Racialized individuals with disabilities experience double burdens of discrimination, leading to exacerbated health inequalities (Reichard & Stolzle, 2011). The prevalence of disability varies among racial and ethnic groups, emphasizing the significance of considering intersectionality in understanding health disparities (Mitra et al., 2022). Social determinants of health, including economic instability, housing, and social cohesion, further contribute to the complexity of health disparities within these populations (Bingham et al., 2013). The paper has integrated figures depicting disability incidence across racial and ethnic groups, emphasizing the need for nuanced research and policy interventions (Mitra et al., 2022). The social determinants paradigm has been employed to underscore the role of systemic issues and discriminatory practices in perpetuating health disparities (WHO, 2022). Economic instability, employment disparities, food insecurity, and housing challenges have been discussed within the context of race, disability, and health outcomes (Suarez-Balcazar et al., 2013). An intersectional approach, guided by Kimberlé Crenshaw's theory, has provided a comprehensive framework for understanding the intricate health disparities experienced by racialized minority groups with disabilities (Crenshaw, 1989). This perspective reveals specific challenges in healthcare access, diagnosis, and treatment, emphasizing the need for tailored interventions (Courtney-Long et al., 2017). Looking ahead, future research should delve into the unique cultural aspects within different racialized minority groups, conduct long-term analyses, and employ qualitative methods to capture the lived experiences of individuals with disabilities (McCall, 2005; Creswell, 2013). Moreover, there is a need for more research focused on policy implications, regional differences, and a broader exploration of complex factors affecting health (Yin, 2014; Varadaraj, 2021). Extending the intersectional approach to include other identities such as gender and sexual orientation will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of health disparities (Collins, 2015). Critical examination of study methodologies is essential to ensure rigor and minimize selection bias, enhancing the overall strength of future research (Mendenhall et al., 2013). Recognizing the complexity of health disparities at the intersection of race and disability is essential for developing targeted interventions and policies. By addressing the limitations and building on future research directions, we can work towards a more inclusive and equitable healthcare landscape for individuals facing these intersecting challenges.