1. Introduction

Displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures in young patients poses a unique challenge when compared to similar injury in the elderly; young patients are generally more active, have fewer medical problems, and have good bone quality. The goals of treatment in the young population focuses on preserving the femoral head, avoiding osteonecrosis and achieving union, therefore avoiding arthroplasty when possible [

1].

Traditionally, most operative fixation for this injury and population is completed using cannulated screws or sliding hip screw implants [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. In recent years, alternative fixed angle implants have been introduced and have gained popularity [

9,

10].

One prominent fixed angle device is the Targon FN: a contoured locking titanium sideplate which can accommodate four proximal sliding screws, in addition to two distal locking screws. Since its emergence in 2007, studies including two meta-analyses have succeeded in showing good short-term outcomes for the device [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Although exhibiting impressive outcomes in the short term, to the best of our knowledge, there is no data regarding the Targon FN system’s complication rates through mid- or long-term follow up. Moreover, there is a little research on long term patient reported outcome measures including chronic pain, level of ambulation, and the use of ambulation assistive devices. This data is critical in evaluating the success of surgical treatment in young patients with displaced femoral neck fractures.

Therefore, we designed a retrospective review to evaluate mid- and long- term surgical outcomes of young patients with displaced femoral neck fractures fixed with Targon FN as compared to fixation with multiple cancellous screws.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection, Data Collection, Inclusion, and Exclusion Criteria

Between 2000 and 2012, 97 patients with unstable intracapsular femoral neck fractures (OTA classification 31-B2.3 or 31-B3.11) were hospitalized in the orthopedic department of Sheba medical center. Data on these patients was obtained via electronic medical record and related database review for study analysis. Fracture classifications were independently performed by two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved by a third orthopedic surgeon, all blinded to the surgery type. Exclusion criteria included, polytrauma, pathological fractures, prior hip or femur surgery on the operative side. The control group (group 1) comprised 47 patients treated with three cancellous screws fixation and the study group (group 2) included 50 patients treated with the Targon FN device. Data was collected between March 2000 to January 2012 and follow up was completed between July and October 2020.

2.2. Surgical Technique and Post Operative Protocol

The surgical technique has been previously described by Thein et al [

13] and Parker and Stedtfeld [

4]. In summary, For the multiple cancellous screws group, a guide wire was inserted just above the level of the lesser trochanter. 3 screws were then inserted up to the subchondral bone of the femoral head following guide wires in an inverted triangle or another triangular shape by the surgeon. For the Targon FN treated group, reduction target was slight valgus or anatomic reduction on the anterior-posterior view and no extension or flexion on the axial. The femur was approached directly via a 4–6 cm lateral incision. Guide wires and telescopic screws were then sequentially inserted to attach the sideplate to the femur to achieve proximal and distal fixation. The majority of surgeries were performed by 3 surgeons, all of them senior consultants with more than 10 years of experience. They were all members of the same department and worked according to the same standards. Postoperative ambulation was not allowed until 6 weeks post operatively.

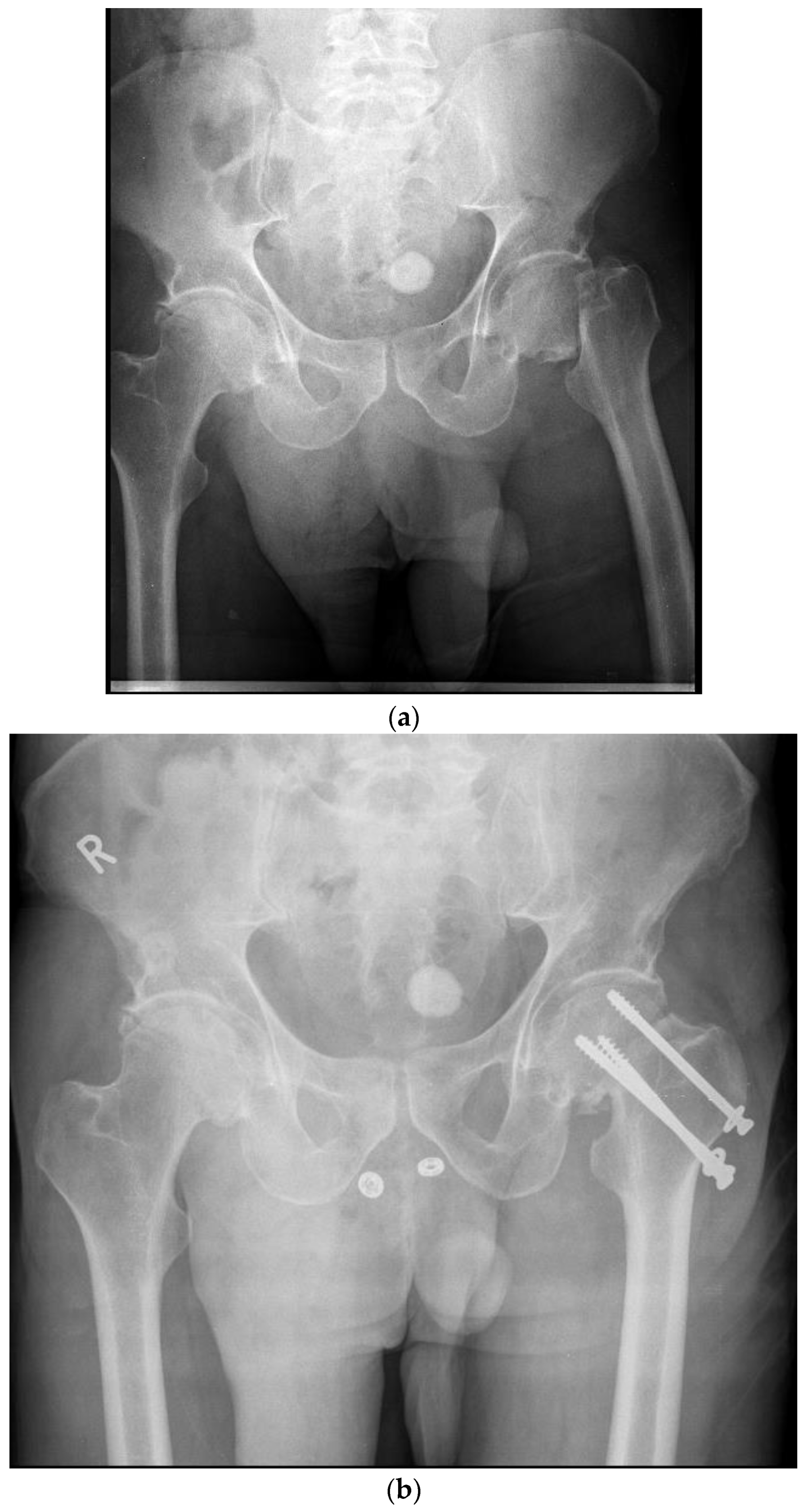

Figure 1.

A- Pre-operative X-Ray demonstrating a left sided displaced femoral neck in a 59-year-old male. B- post- operative X-Ray demonstrating operative fixation of the same fracture with cancellous screws.

Figure 1.

A- Pre-operative X-Ray demonstrating a left sided displaced femoral neck in a 59-year-old male. B- post- operative X-Ray demonstrating operative fixation of the same fracture with cancellous screws.

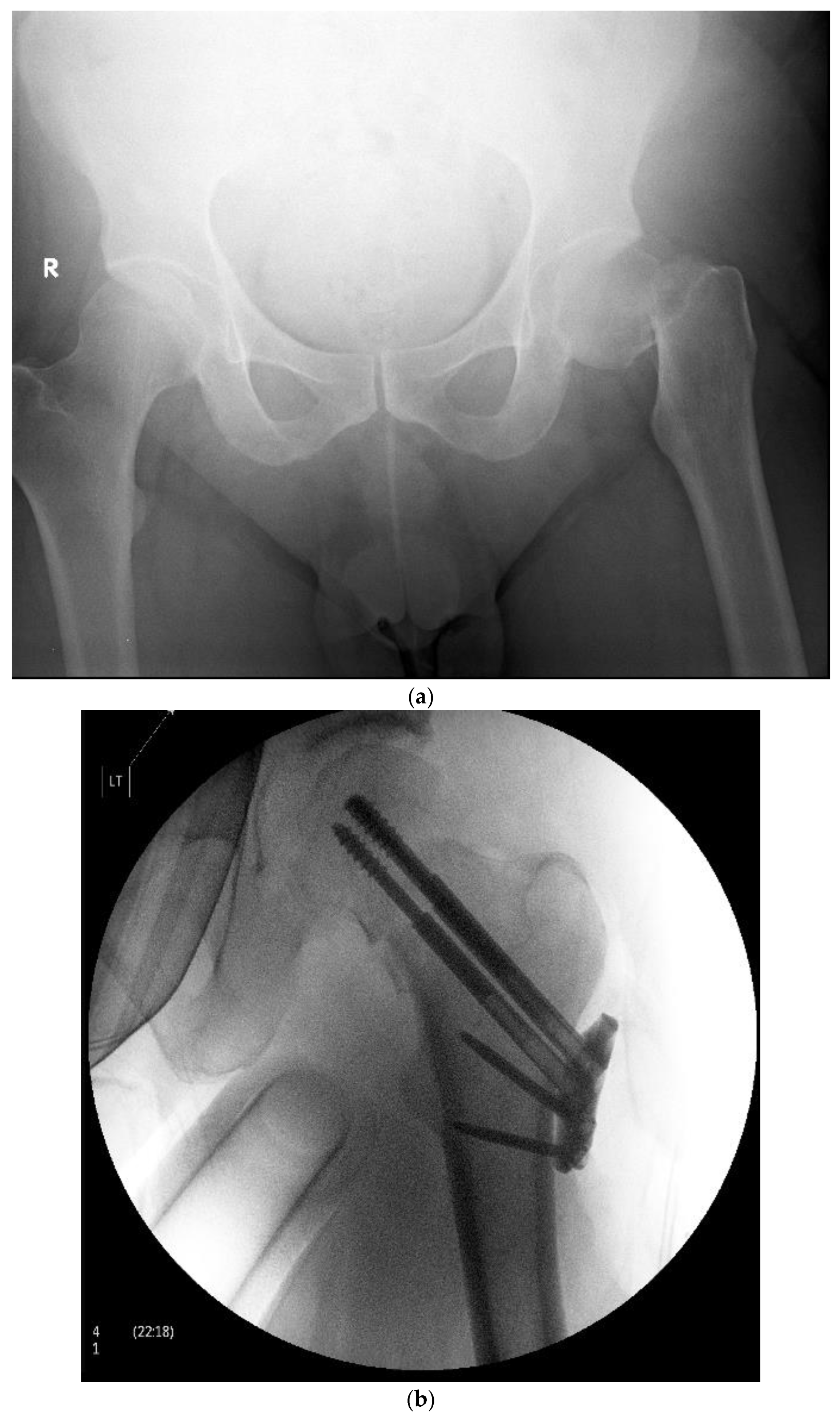

Figure 2.

A- Pre-operative X-Ray demonstrating a left sided displaced femoral neck fracture in a 48-year-old male. B- post- operative X-Ray demonstrating operative fixation of the same fracture with the Targon FN system.

Figure 2.

A- Pre-operative X-Ray demonstrating a left sided displaced femoral neck fracture in a 48-year-old male. B- post- operative X-Ray demonstrating operative fixation of the same fracture with the Targon FN system.

2.3. Follow Up and Endpoints

Patients follow up was completed using telephone calls during July-October 2020. Data regarding patients who could not be reached by telephone was obtained using their most recent outpatient clinic record. The patients’ quality of life measures were assessed using standardized EQ-5D-5L PROM (Patient-Reported Outcome Measure) questionnaires. In addition, they were asked about any follow up surgery, revision surgery or post-operative complication (osteonecrosis, nonunion, limb shortening) during the period between their initial surgery and present time. Complication endpoints included nonunion, osteonecrosis of the femoral head, and salvage (osteotomy or removal of internal fixation) or reconstruction (hemiarthroplasty or total hip replacement) revision.

2.4. IRB Approval

Approval for the study was obtained from our local Institutional Review Board. Screened patients received an early notice via mail and expressed an informed consent via telephone to participate in this study.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using RStudio software (RStudio, Inc, Boston, MA). Categorical variables are given as number and percent. Continuous variables are given as mean and standard deviation (SD). The χ2 was used to test for statistical significance among categorical variables. The Brunner-Munzel test was used to test for statistical significance among ordinal variables, including chronic pain, ability to ambulate, and ambulation assistive device usage scores. Total major complications were calculated as the sum of non-union, avascular necrosis (AVN), peri-prosthetic fractures or shortening of the effected limb. Revision surgery rates were separately assessed. Logistic regression was used to estimate the influence of the internal fixation device (independent variable) on major complication probability (dependent variable). All P values were 2-sided, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The study included a total of 97 patients, and their relevant demographic, clinical and functional data are presented in

Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 55.2 years (SD: 10.49, interquartile range 50-72). 83% of patients were < 65 years of age. The rest of the patients were offered operative fixation opposed to arthroplasty because of their clinical and radiographic presentation. Those > 65 were active, physiologically young, patients with high quality bone. The mean duration of follow-up was 79.6 months for group 1 and 82.75 for group 2 (p value = 0.97).

Patients’ complication rates are presented in

Table 2. Three patients from group 1 (6.38%) and seven patients from group 2 (14%) developed osteonecrosis of the femoral head (p value = 0.36). 17 patients (36.17%) had nonunion in group 1 while only 2 (4%) had nonunion in group 2 (p value< 0.001). 13 group 1 patients (27.65%) required revision surgery in comparison to only 9 group 2 patients (p value = 0.25). Regarding only conversions to THR (subtracting hardware removals from total revision surgery count), group 1 and 2 had 13 and 8 cases, respectively (p value = 0.16).

When comparing total complications rate, including non-union, AVN, peri-prosthetic fractures or shortening of the effected limb, group 1 had 23 complications (48.93%) while group 2 had 11 (22%) (p value = 0.005).

Logistic regression model found that performing internal fixation with the Targon FN device decreased the odds ratio for overall complication by a factor of 0.34 (P = 0.02).

Categorial variables are presented as count (percent). Patient’s quality of life scores are exhibited in

Table 3. In group 1, 3 patients reported no chronic pain since surgery, 9 patients had mild pain, 2 had moderate pain, 1 had severe pain 0 had extreme pain (mean = 2.06). In the Targon FN treatment group, 7 patients reported no chronic pain, 16 mild pain, 7 moderate pain, 5 severe pain and 3 extreme pain (mean = 2.5) (p value = 0.21).

Regarding ability to ambulate, 7 group 1 patients reported no problem walking, 4 patients reported slight problem walking, 2 moderate problem and 1 inability to walk (mean = 1.85). In group 2, 30 patients reported no problem walking, 5 reported slight problem, 1 moderate problem, 1 on severe problem and 1 reported on inability to walk (mean = 1.36) (p value = 0.07). When asked about the use of walking aids, 7 group 1 patients reported no use of aids, 3 reported using one walking aid (cane), 1 reported using two aids, 1 reported on using a walker and 2 reported the use of a wheelchair (mean = 2.14). In group 2, 29 patients reported no walking aids, 8 reported one walking aid and 1 reported the use of a wheelchair (mean = 1.31) (p value = 0.07).

4. Discussion

The goal of treatment in patients with a displaced femoral neck fracture, especially young active individuals, is to preserve the femoral head and restore natural hip function. It has been reported that fracture healing with no osteonecrosis leads to a good functional outcome [

18]. Furthermore, a more anatomic reduction leads to higher union and lower failure rates. In this retrospective study, we have presented long term outcomes of femoral neck fracture fixation using the the Targon FN by exploring the device’s failure rates and patient’s ability to return to pre-injury quality of life.

The short-term failure rate of the Targon FN when used for internal fixation of displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures ranges from 15%-48% [

16,

19,

20]. The literature has shown favorable results with the Targon FN compared to other methods of intracapsular femoral neck fracture fixation. Thein et al. have previously shown significant reductions in non-union, revision surgery, and overall complication rates in the short term with the Targon FN [

13].

Biber et al have concluded that using the Targon FN results in relatively low complication rates of 16.4 % and a conversion to joint replacement of 9.6 % in a cohort of 135 cases (mean age 71 years; average operation time 60 minutes; average hospital stay: ten days). Nevertheless, they concluded that the complication rate was significantly higher in displaced fractures and that implant perforation seems to be underestimated [

21].

Though some researchers have explored the Targon FN success as compared to a control group in the past, the longest follow up we could find is by Thein et al of 28.6 months. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, no other paper has followed their patients for more than 10 years as in the current study. The longest follow up we could find was in project conducted by Majernícek M et al in 2009, with a mean follow up time of 6.9 years examining the dynamic hip screw device’s outcomes, though the group was not compared to a control [

7]. Both works also did not explore the impact of the Targon FN system on PROMs.

Our study results have strengthened past evidence regarding the Targon FN’s performance superiority in comparison with multiple cancellous screws. We have demonstrated that the Targon FN has significantly lower rates of total major complications (p value = 0.005). The greatest difference was seen specifically in non-union rates (p value < 0.001). However, AVN incidence between the groups was not-significantly different (p value = 0.37). The superiority of the Targon FN in nonunion rates is likely due to its effect on hip mechanics while AVN is a pathology related to blood supply disruption. The Targon FN allows for a controlled collapse at the fracture site while cancellous screws do not. For this reason, non-union is more common in the cancellous screw group in the shorter term. AVN was exposed at a later time frame secondary to the natural progression of poor blood supply in this fracture pattern. The long-term follow-up may also have influenced the non-significant difference in revision surgery and total hip replacement rates (p value = 0.25 and p value = 0.16 respectively). The hip replacement surgeries were at times conducted many years after the initial injury, more likely related to osteoarthritic changes and not to the original insult.

Concerning functional evaluation, studies have shown mixed results. Eschler et al. used the Harris Hip score to evaluate the Targon FN’s to the Sliding Hip Screw. They demonstrated a less favorable outcome (69.5 ± 14.5 points and 87.7 ± 13.9 points respectively) [

16]. Takigawa et. al. have shown that 88.5% of the patients treated with the implant for intracapsular fractures had achieved their pre-injury level of mobility over and average 16.4 month follow-up [

19]. Parker et al. reported that patients could maintain the same preoperative mobility score or achieve better mobility after femoral neck fracture fixation with Targon FN [

22,

23].

To our knowledge, this study was the first to report long term quality of life measures in patients who underwent internal fixation of femoral neck fractures with the Targon FN as compared to internal fixation with multiple cancellous screws. Our data shows increased ambulation ability, and decreased use of ambulation assistive device in the Targon FN group, though not statistically significant (p value = 0.07 both). There was no difference in chronic pain scores between the groups (p value = 0.21). These outcomes could be explained by the fact that we were more successful in contacting a larger group of Targon FN patients by telephone (30), compared to cancellous screws patients (14), while the rest of the data was obtained from follow-up clinic records as mentioned. Therefore, by the time of questioning, patients have aged significantly and likely suffered additional insults. Moreover, there is likely an element of healthy participant bias. Considering the previously discussed results which exhibit the Targon FN’s superior performance over cancellous screws, we can assume that the patients that we were able to contact had an overall better natural history and were overall healthier than those we were unable to contact which may bias our results in favor of the cancellous screws. Given these implications the Targon FN trend towards improved PROM in ambulation ability and reduced walking aid use is even more impressive.

Our study is not without limitations. It is a retrospective study and not a randomized control trial. We have mentioned the possibility of healthy participant bias above. We also have an uneven number of patients between the control and study group which may influence our analysis. Lastly, a logistics regression analysis is less significant in this small of a sample size. However, the analysis was meant to underscore the finding of lower total complication rate in Targon FN fixation as compared to cancellous screw fixation for femoral neck fractures.

We conclude that a displaced intracapsular femoral neck fracture, especially in young active patients, is a major traumatic insult and may represent a life changing event. Older methods of fixation were associated with a relatively high rate of failure. Our paper demonstrates that the Targon FN has fewer major post-surgical complications rates compared to traditional fixation methods in the long term. Regarding quality-of-life measures, while not statistically significant, the Targon FN exhibits a positive trend towards the ability to preserve stable and satisfactory walking ability.

References

- Ly, T. V and Swiontkowski, M. F. (2008) ‘Treatment of Femoral Neck Fractures in Young Adults’, JBJS, 90(10). Available online: https://journals.lww.com/jbjsjournal/Fulltext/2008/10000/Treatment_of_Femoral_Neck_Fractures_in_Young.25.aspx.

- Husby, T. et al. (1989) ‘Early loss of fixation of femoral neck fractures. Comparison of three devices in 244 cases.’, Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica, 60(1), pp. 69–72. [CrossRef]

- Gjertsen, J.-E. et al. (2010) ‘Internal screw fixation compared with bipolar hemiarthroplasty for treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients.’, The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume, 92(3), pp. 619–628. [CrossRef]

- Parker, M. J. and Stedtfeld, H.-W. (2010) ‘Internal fixation of intracapsular hip fractures with a dynamic locking plate: initial experience and results for 83 patients treated with a new implant.’, Injury, 41(4), pp. 348–351. [CrossRef]

- Parker, M. J. et al. (2002) ‘Hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly. A randomised trial of 455 patients.’, The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume, 84(8), pp. 1150–1155. [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy, K., Parker, M. J. and Rowlands, T. K. (2005) ‘The complications of displaced intracapsular fractures of the hip: the effect of screw positioning and angulation on fracture healing.’, The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume, 87(5), pp. 632–634. [CrossRef]

- Majernícek, M. et al. (2009) ‘[Osteosynthesis of intracapsular femoral neck fractures by dynamic hip screw (DHS) fixation]’, Acta chirurgiae orthopaedicae et traumatologiae Cechoslovaca, 76(4), pp. 319–325. Available online: http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19755057.

- Widhalm, H. K. et al. (2019) ‘A Comparison of Dynamic Hip Screw and Two Cannulated Screws in the Treatment of Undisplaced Intracapsular Neck Fractures—Two-Year Follow-Up of 453 Patients’, Journal of Clinical Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Duffin, M. and Pilson, H. T. (2019) ‘Technologies for Young Femoral Neck Fracture Fixation’, Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 33. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/jorthotrauma/Fulltext/2019/01001/Technologies_for_Young_Femoral_Neck_Fracture.5.aspx.

- Hoshino, C. M. et al. (2016) ‘Fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures in young adults: Fixed-angle devices or Pauwel screws?’, Injury, 47(8), pp. 1676–1684. [CrossRef]

- Li, T. and Zhang, Q.-S. (2018) ‘Is dynamic locking plate superior than other implants for intracapsular hip fracture: A meta-analysis’, Medicine, 97(47), p. e13001. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H., Pan, Z. and Jiang, H. (2018) ‘Is dynamic locking plate(Targon FN) a better choice for treating of intracapsular hip fracture? A meta-analysis’, International Journal of Surgery, 52, pp. 30–34. [CrossRef]

- Thein, R. Thein, R. et al. (2014) ‘Osteosynthesis of Unstable Intracapsular Femoral Neck Fracture by Dynamic Locking Plate or Screw Fixation: Early Results’, Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 28(2). Available online: https://journals.lww.com/jorthotrauma/Fulltext/2014/02000/Osteosynthesis_of_Unstable_Intracapsular_Femoral.2.aspx.

- Warschawski, Y. et al. (2016) ‘Dynamic locking plate vs. simple cannulated screws for nondisplaced intracapsular hip fracture: A comparative study’, Injury, 47(2), pp. 424–427. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, X. L. et al. (2014) ‘The Targon Femoral Neck hip screw versus cannulated screws for internal fixation of intracapsular fractures of the hip’, The Bone & Joint Journal, 96-B(5), pp. 652–657. [CrossRef]

- Eschler, A. et al. (2014) ‘Angular stable multiple screw fixation (Targon FN) versus standard SHS for the fixation of femoral neck fractures’, Injury, 45, pp. S76–S80. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J. L. et al. (2007) ‘Fracture and dislocation classification compendium - 2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee.’, Journal of orthopaedic trauma, 21(10 Suppl), pp. S1-133. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J. A. et al. (2010) ‘Optimal Treatment of Femoral Neck Fractures According to Patient’s Physiologic Age: An Evidence-Based Review’, Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 41(2), pp. 157–166. [CrossRef]

- Takigawa, N. et al. (2016) ‘Clinical results of surgical treatment for femoral neck fractures with the Targon® FN’, Injury, 47, pp. S44–S48. [CrossRef]

- Osarumwense, D. et al. (2015) ‘The Targon FN System for the Management of Intracapsular Neck of Femur Fractures: Minimum 2-Year Experience and Outcome in an Independent Hospital’, cios, 7(1), pp. 22–28. [CrossRef]

- Biber, R., Brem, M. and Bail, H. J. (2014) ‘Targon® Femoral Neck for femoral-neck fracture fixation: lessons learnt from a series of one hundred and thirty five consecutive cases’, International Orthopaedics, 38(3), pp. 595–599. [CrossRef]

- Parker, M. J. and Gurusamy, K. (2005) ‘Modern methods of treating hip fractures.’, Disability and rehabilitation, 27(18–19), pp. 1045–1051. [CrossRef]

- Parker, M. J. and Blundell, C. (1998) ‘Choice of implant for internal fixation of femoral neck fractures. Meta-analysis of 25 randomised trials including 4,925 patients.’, Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica, 69(2), pp. 138–143. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. et al. (2018) ‘Comparison of early complications between the use of a cannulated screw locking plate and multiple cancellous screws in the treatment of displaced intracapsular hip fractures in young adults: a randomized controlled clinical trial’, Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 13(1), p. 201. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).