1. Introduction

In oxygenic photosynthesis, the photon energy absorbed by the light-harvesting systems of both photosystem II (PSII) and photosystem I (PSI) of the photosynthetic electron transport system excites the reaction center chlorophylls, P680 in PSII and P700 in PSI. The excitation of both reaction center chlorophylls starts their catalytic reactions of electron flow from oxidation to reduction: H2O oxidation with O2 evolution to plastoquinone (PQ) reduction in PSII and PQ oxidation through cytochrome (Cyt) b6/f and plastocyanin to the reduction of ferredoxin (Fd) through electron transport carriers, including phylloquinone, Fx, and FA/FB in PSI. The reduced Fd delivers electrons mainly to NADPH production catalyzed by Fd-NADP oxidoreductase. Simultaneously, with the photosynthetic linear electron flow from H2O to NADPH, protons accumulate in the lumen of thylakoid membranes, forming ΔpH across thylakoid membranes. These accumulated protons originate from water oxidation in PSII and transport from the stroma to the lumen by the Q-cycle during PQ oxidation in the cytochrome b6/f complex. The ΔpH, as a proton motive force, drives ATP synthase to produce ATP. These energy compounds, the reduced Fd, NADPH, and ATP produced in the light reaction, drive the dark reactions of CO2 assimilation and photorespiration in C3 plants.

The photosynthetic linear electron flow is potentially exposed to the threat of the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The supply rate of NADPH to ATP produced in the photosynthetic linear electron flow is larger than the consumption rate of NADPH to ATP in the dark reaction even in non-photorespiratory conditions [

1,

2,

3]. The excess supply of NADPH by the photosynthetic linear electron flow is further enhanced under photorespiratory conditions because much more ATP is consumed in dark reactions [

2]. Furthermore, as CO

2 assimilation is stimulated by photosynthetic linear electron flow, the excess NADPH supply is further enhanced. That is, the photosynthetic linear electron flow, which is the only flow to provide electrons for NADPH production in photosynthesis, accumulates NADPH and fulfills electrons in the photosynthetic electron transport system. The accumulation of electrons in PSI is observed as the reduction of electrons carried at the acceptor side of PSI; the Fe/S-series, F

x, F

A/F

B and Fd, triggers O

2 reduction to produce O

2-, and O

2- degrades Fe/S compounds and inactivates PSI [

4].

The mismatch issue that the supply rate of NADPH surpasses its demand rate, which is brought by the photosynthetic linear electron flow, is solved by the cyclic electron flow around PSI [

1]. The cyclic electron flow induces ΔpH across thylakoid membranes and produces ATP without any production of electrons for NADPH supply. Rather, the cyclic electron flow stimulates the consumption of NADPH and contributes to the activation of the dark reaction. That is, the cyclic electron flow around PSI has the potential to alleviate the threat of photosynthetic linear electron flow.

The potential threat of the photosynthetic linear electron flow thus far has not been explored, and the physiological function of the cyclic electron flow around PSI has not been examined from the aspect of oxidative stress. Of course, CO

2 assimilation could proceed at an ATP supply-limited rate even under photorespiratory conditions unless NADPH accumulates. Since the accumulation of electrons at the acceptor side of PSI, observed as the reduction of the electron carriers, Fe/S-clusters, causes ROS production [

4], the accumulation of NADPH should be alleviated, which would be why the cyclic electron flow around PSI functions. The cyclic electron flow would promote the consumption of NADPH by supplying ATP in the dark reaction.

A molecular mechanism catalyzing Fd-CEF, Fd-quinone oxidoreductase (FQR), has been proposed: both chloroplast NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (NDH) and PGR5/PGRL1 function in Fd-CEF [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. In vivo, the activity of Fd-CEF has been shown as the excess quantum yield of PSI against the apparent quantum yield of PSII [Y(II)] [

2,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The apparent quantum yield of PSI [Y(I)] becomes excessive against Y(II) with oxidized P700 [

15]. However, these observations were artifacts [

15]. The value of Y(I) was measured by the saturation-pulse illumination method [

16]. The saturation-pulse illumination under actinic light illumination excites the ground state of P700 to oxidized P700 (P700

+) through light-excited P700 (P700*), and the ratio of induced P700

+ to total P700 has been estimated as Y(I). The amount of P700

+ induced by saturation-pulse illumination depends on the rate-determining step of the P700 photooxidation reduction cycle in PSI [

15]. In the P700 photooxidation reduction cycle, P700* is oxidized to P700

+ by donating electrons to the electron acceptors A

o, A

1, F

x, and F

A/F

B sequentially to Fd. P700

+ is reduced to the ground state of P700 by electrons from PSII through PQ, the Cyt

b6/

f complex, and plastocyanin (PC). If the reduction of P700

+ in the cycle was the rate-determining step, in which oxidized P700 accumulated under actinic light illumination, the amount of the ground state of P700 was overestimated by the saturation-pulse illumination method [

15]. On the other hand, if the oxidation of P700* in the cycle was the rate-determining step, the amount of the ground state of P700 was underestimated by the saturation-pulse illumination method [

16]. It is too difficult to estimate the true Y(I) when evaluating Fd-CEF activity [

15].

Furthermore, the ability of electron donation from the reduced Fd to the oxidized PQ through FQR has been evaluated using the isolated thylakoid membrane [

7,

17,

18]. The addition of Fd/NADPH to the thylakoid membrane increased the minimal yield of Chl fluorescence, and PQ was reduced by the reduced Fd. The rate of increase in the minimal yield of Chl fluorescence was treated as the activity of FQR. However, the reduced Fd donates electrons to PSII, not PQ [

19]. Furthermore, the reduced Fd donates electrons to Cyt

b559, which is inhibited by antimycin A [

17]. The effect of antimycin A also inhibits Fd-dependent quenching of 9-aminoacridine fluorescence, which is driven by far-red light illumination [

17]. The quenching of 9-aminoacridine fluorescence shows ΔpH formation across the thylakoid membrane. Far-red-driven quenching has been considered to be induced by Fd-CEF activity. However, as described above, electron donation from the reduced Fd to PSII could also induce the quenching of 9-aminoacridine fluorescence by maintaining the photosynthetic linear electron flow.

As described above, no credible methods have been available to detect and evaluate Fd-CEF activity, that is, FQR activity. To elucidate the physiological function of Fd-CEF, an assay system capable of measuring Fd-CEF in vivo was needed. In the present research, we monitored the redox reaction of Fd simultaneously with Chl fluorescence, P700

+ and PC

+ absorbance changes, and net CO

2 assimilation using intact leaves of

Arabidopsis thaliana. We have already succeeded in measuring electron flux in Fd-CEF in

Arabidopsis thaliana [

20]. The oxidation rate of the reduced Fd, not related to the photosynthetic linear electron flow, that is, the extra oxidation rate of Fd, was defined as the electron flux in Fd-CEF, vCEF. vCEF is regulated by the reduction‒oxidation state of PQ. As PQ is oxidized with enhanced CO

2 assimilation, vCEF increases [

20]. These characteristics follow the model of cyclic electron flow [

1]. This would be one of the reasons why we were unable to detect the extra Fd oxidation reaction [

20,

21,

22]. Under limited photosynthesis, where PQ was highly reduced and the apparent quantum yield of PSII was low, the extra Fd oxidation reaction was suppressed in vivo. We proposed that the extra Fd oxidation reaction reflects the activity of Fd-CEF.

Surprisingly, the NDH-less mutant (

crr4) of

Arabidopsis thaliana showed almost the same Fd-CEF activity as the wild type (WT) in vivo [

20]. In the present research, we comparatively analyzed the activity of Fd-CEF in a PGR5-less mutant (

pgr5hope1) of

Arabidopsis thaliana. We used the mutant

pgr5hope1, not

pgr5.

pgr5 is a double mutant that is deficient in both

pgr5 and

ptp1 (At2G17240) [

23]. Due to the loss of

ptp1, the CO

2 assimilation rate was significantly lower than that of WT

Arabidopsis thaliana. The

Arabidopsis thaliana mutant deficient in

pgrl1, which also shows the loss of PGR5 protein, shows the same CO

2 assimilation rate as WT [

24]. To elucidate the physiological function of PGR5, either the

pgr5hope1 or

pgrl1 mutant should be used. Unless Fd-CEF functions, the CO

2 assimilation rate should not be maintained in

pgr5hope1. However,

pgr5hope1 shows the same rate of CO

2 assimilation and photosynthetic linear electron flux as WT [

4,

23]. These facts also showed that

pgr5hope1 does not function as a mediator of Fd-CEF. On the other hand,

pgr5hope1 showed a higher reduced state of Fd than WT [

4]. This is due to the suppressed oxidation of P700 in PSI [

4]. That is, if Fd-CEF activity, as defined in a previous report [

20], required reduced Fd,

pgr5hope1 would show increased Fd-CEF activity. As expected,

pgr5hope1 showed higher Fd-CEF activity than WT. We discuss the molecular mechanisms and physiological functions of Fd-CEF in vivo.

2. Results

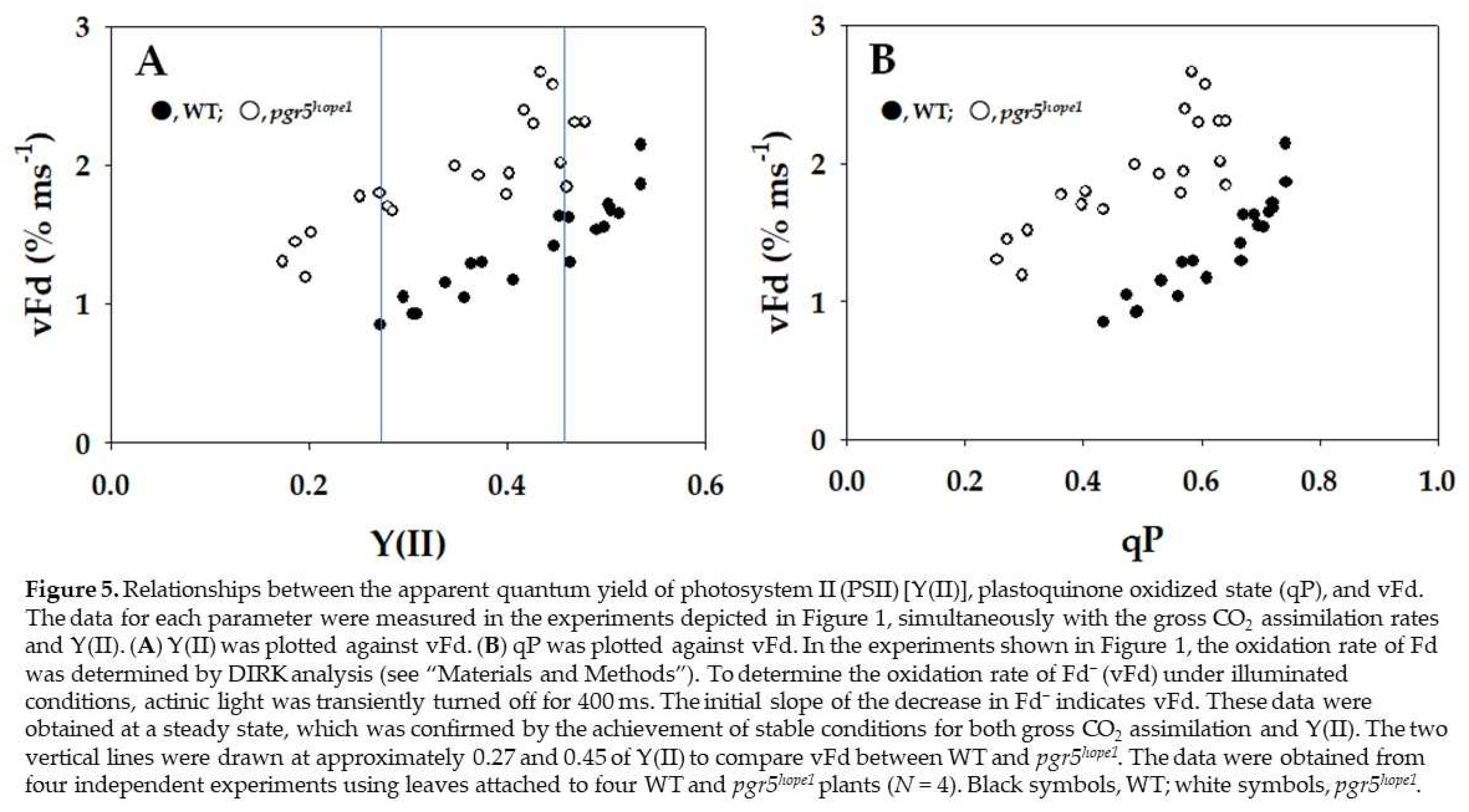

Both the gross CO

2 assimilation rate and the apparent quantum yield of PSII [Y(II)] were plotted against the intercellular partial pressures of CO

2 (Ci) (

Figure 1). These two parameters showed the same dependencies on Ci in both WT and

pgr5hope1.

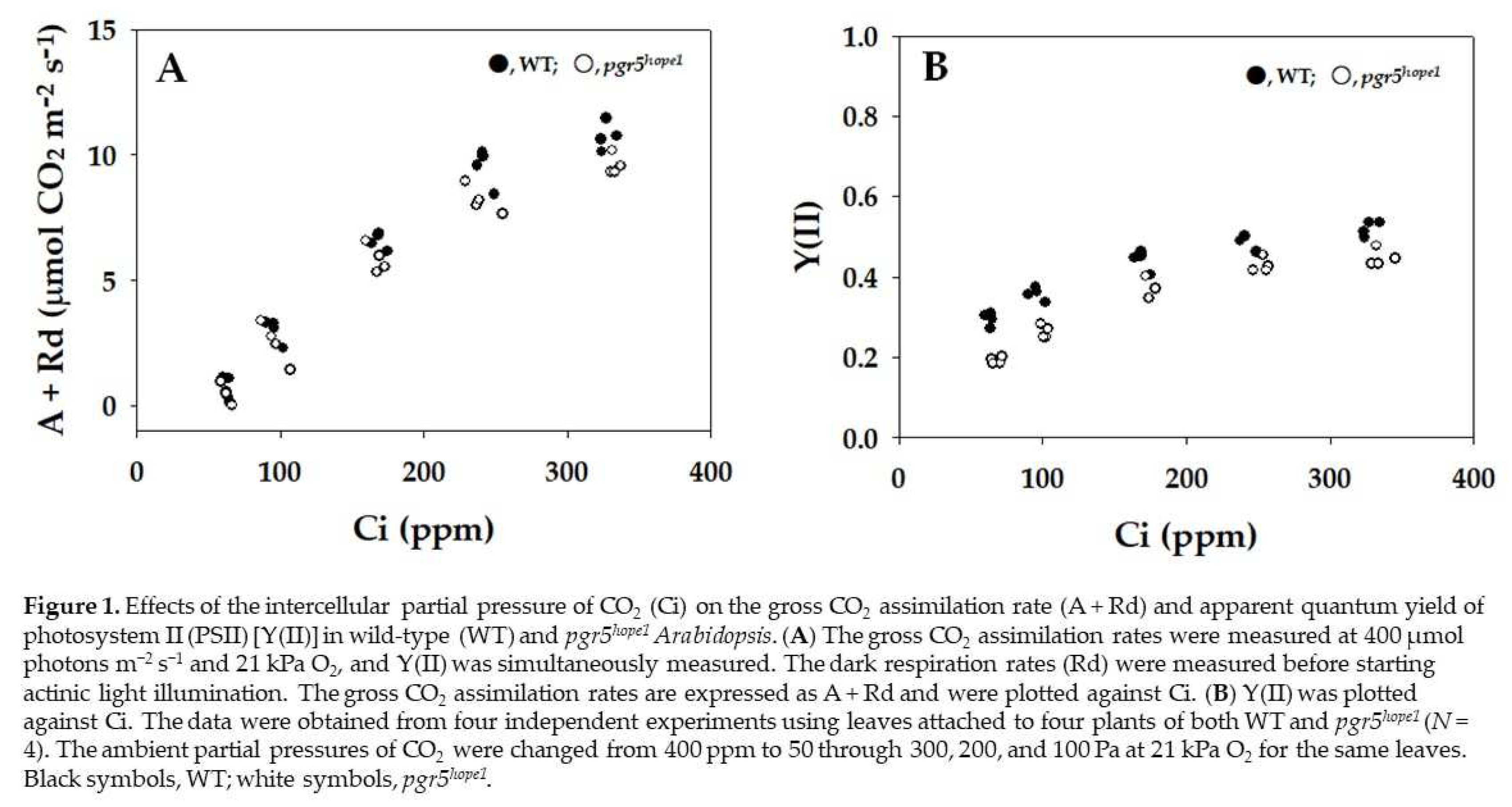

The parameters P700

+, PC

+, and Fd

− against Y(II) are plotted in

Figure 2. With the decrease in Y(II) caused by lowering Ci, P700 was oxidized from approximately 10 to 40% in WT (

Figure 2A). On the other hand, P700 was not oxidized even with the decrease in Y(II) in

pgr5hope1 (

Figure 2A). Similarly, PC was oxidized from 65 to 90% in WT (

Figure 2B). On the other hand, the oxidized PC percentage decreased from 20 to 5% with the decrease in Y(II) in

pgr5hope1 (

Figure 2B). In contrast to both P700

+ and PC

+, Fd

− did not change in response to the decrease in Y(II) in WT (

Figure 2C). This is due to the oxidation of P700 in PSI [

4]. On the other hand, Fd

− in

pgr5hope1 was higher than that in WT and increased from 40 to 55% with the decrease in Y(II) (

Figure 2C). This shows that the limitation of the electron sink accumulates electrons as the reduced form of Fd, which is why the oxidized PC percentage decreased (

Figure 2B) [

4].

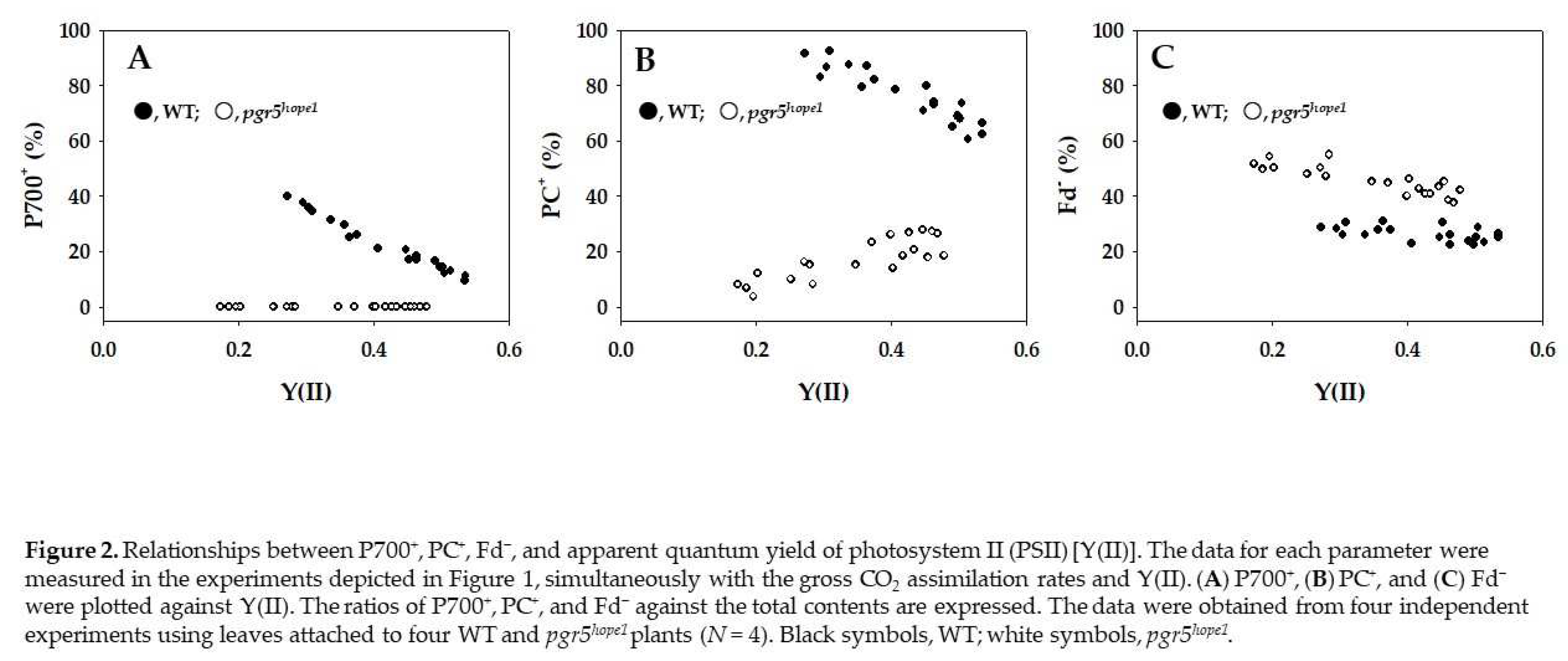

The parameters nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ) and plastoquinone reduced state (1 − qP) against Y(II) are plotted in

Figure 3. The increase in NPQ showed the enhancement of heat dissipation of photon energy absorbed by PSII. With the decrease in Y(II), NPQ increased from approximately 0.5 to 1.5 in WT (

Figure 3A). On the other hand, NPQ in

pgr5hope1 was lower than that in WT, and NPQ increased from 0.2 to 0.9 with the decrease in Y(II) in

pgr5hope1 (

Figure 3A). An increase in 1 − qP showed a reduction in the plastoquinone pool. WT and

pgr5hope1 showed the same dependence of 1 − qP on the decrease in Y(II), where 1 − qP increased with the decrease in Y(II) (

Figure 3B). With the decrease in Y(II), 1 − qP increased from approximately 0.25 to 0.6 in WT (

Figure 3B). On the other hand, with the decrease in Y(II), 1 − qP increased from approximately 0.35 to 0.75 in

pgr5hope1 (

Figure 3B). Although the dependence of 1 – qP on Y(II) in

pgr5hope1 was the same as that of WT, the values of 1 − qP in

pgr5hope1 further increased with lowering Y(II) from 0.25 to 0.15 compared to WT.

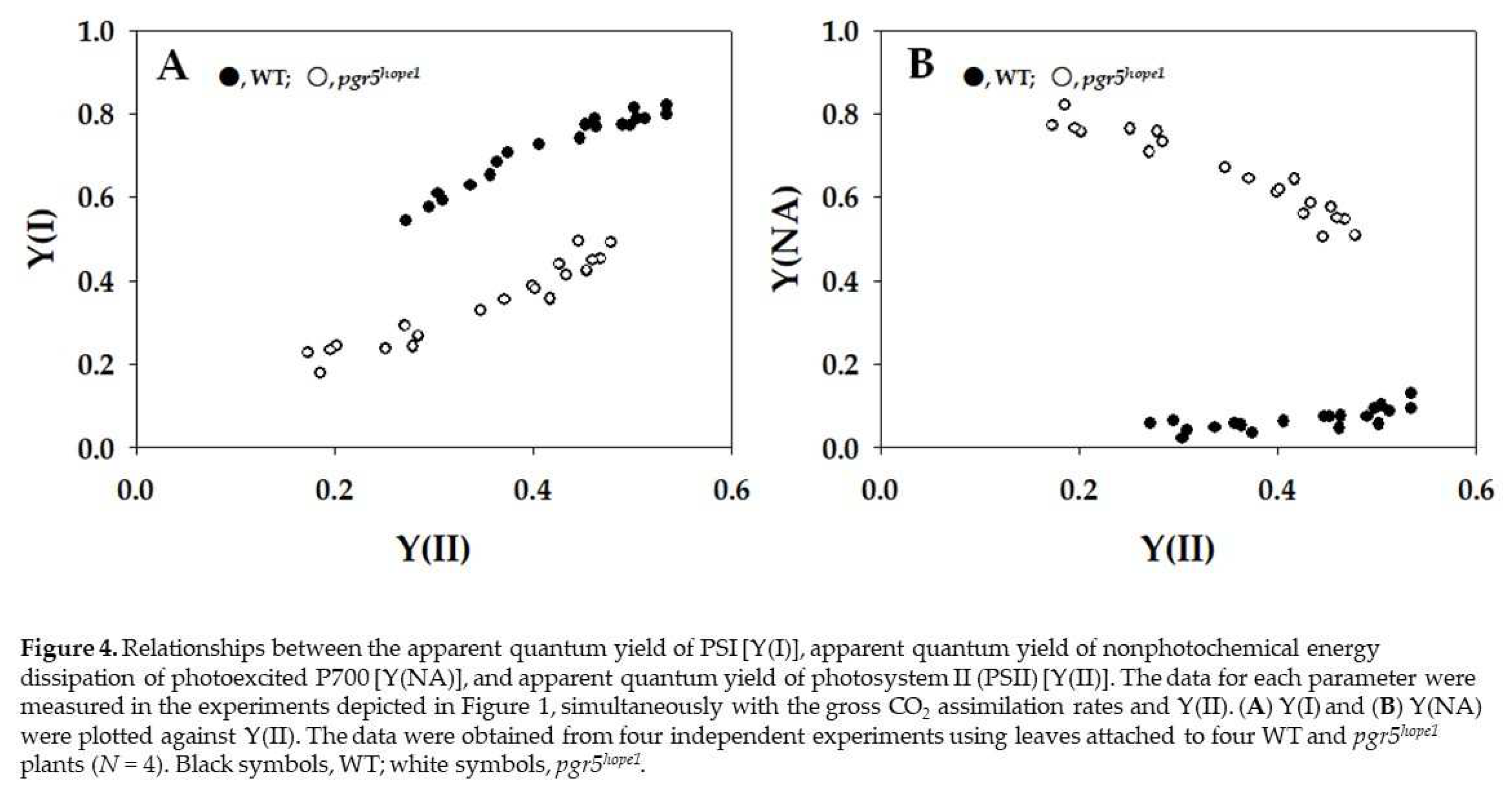

The parameters apparent quantum yield of PSI [Y(I)] and apparent quantum yield of nonphotochemical energy dissipation of photoexcited P700 [Y(NA)] are plotted in

Figure 4. Both Y(I) and Y(NA) were estimated by illuminating the leaves with saturation-pulse light under actinic light illumination. Y(I) reflected the strength of the donor-side limitation of the P700 photooxidation reduction cycle, and Y(NA) reflected that of the acceptor-side limitation during saturation-pulse illumination [

15]. That is, if P700 was highly oxidized under actinic light, Y(I) showed a higher value, and the reverse was also true [

20]. For example, if Y(NA) was higher, Y(I) was lower [

16]. A higher Y(NA) has a positive relationship with a higher reduced state of Fd at the steady-state illumination of actinic light [

4]. With the decrease in Y(II), Y(I) decreased from approximately 0.8 to 0.5 in WT (

Figure 4A). On the other hand, with the decrease in Y(II), Y(I) decreased from approximately 0.5 to 0.2 in

pgr5hope1 (

Figure 4A). Furthermore, the dependence of Y(I) on Y(II) in

pgr5hope1 was different from that in WT, and the Y(I) values in

pgr5hope1 were lower than those in WT. Y(NA) in WT was kept at lower values from 0.1 to 0.05 with the decrease in Y(II); on the other hand, Y(NA) in

pgr5hope1 was higher than that in WT (

Figure 4B). The Y(NA) value in

pgr5hope1 increased from 0.5 to 0.8 with the decrease in Y(II) (

Figure 4B), which seems to be related to the dependence of Fd reduction on Y(II) (

Figure 2C). The Y(NA) obtained by saturation-pulse light illumination reflects the reduction‒oxidation state of Fd under actinic light illumination.

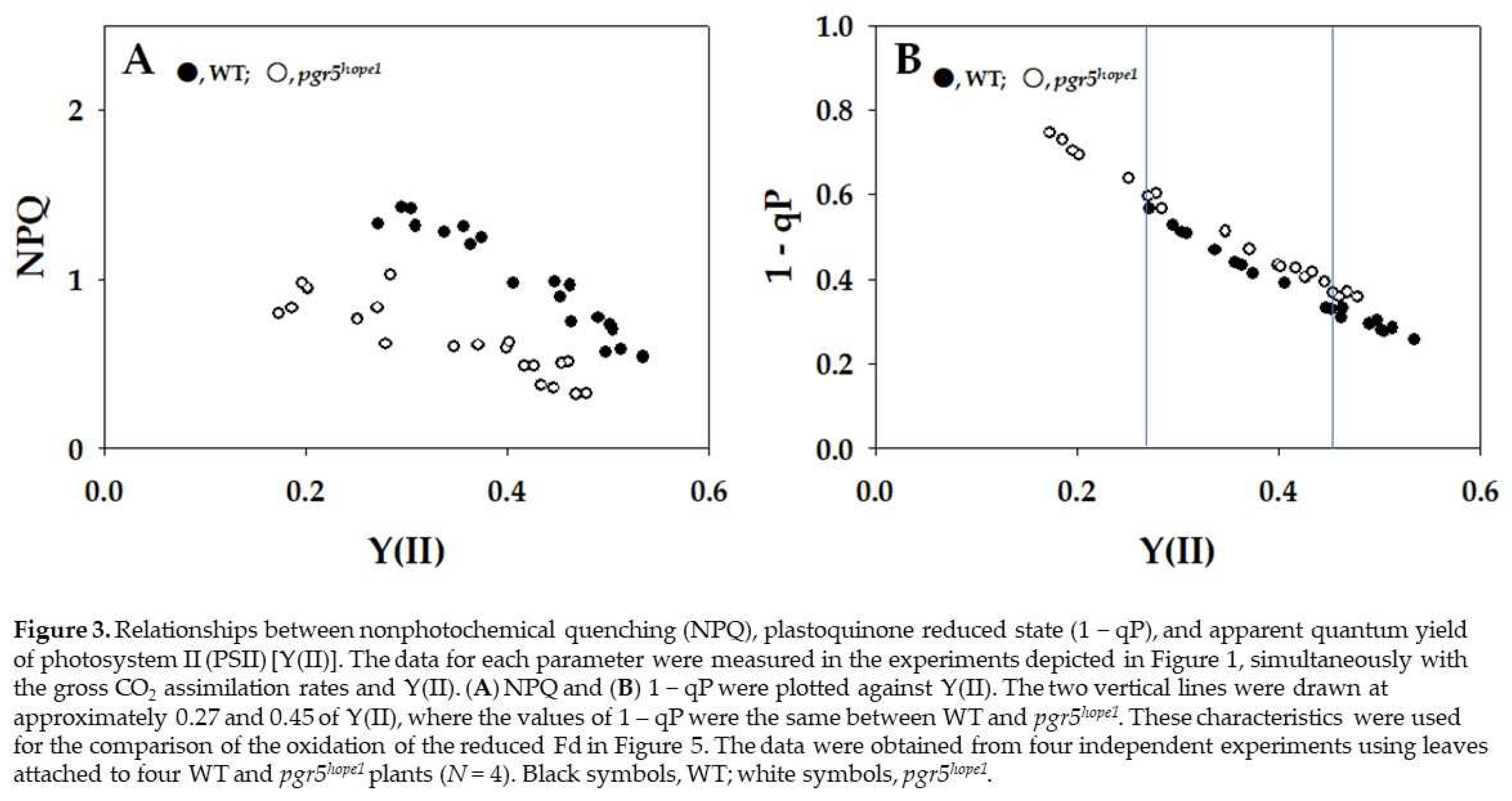

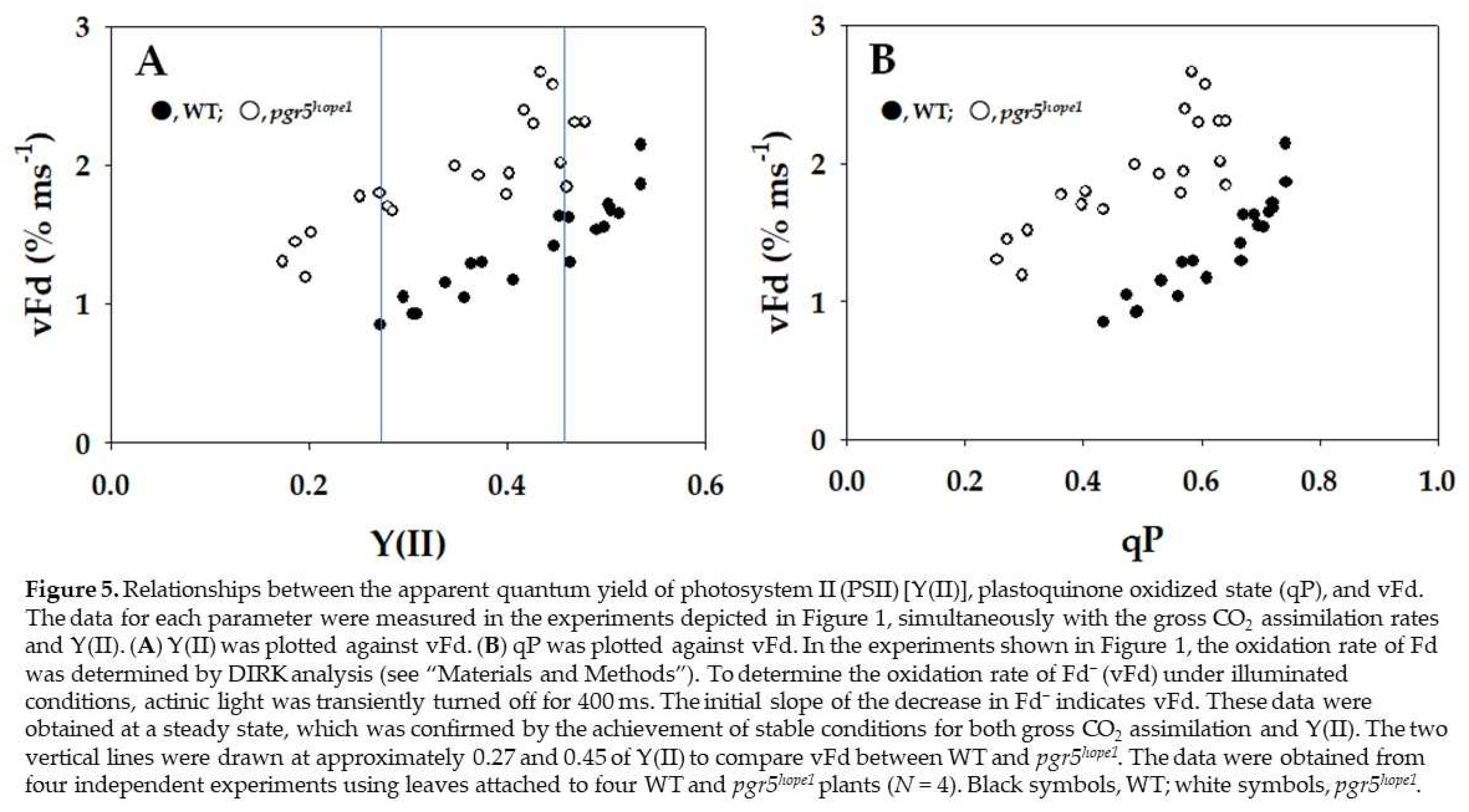

Finally, the oxidation rates of the reduced Fd (vFd) against Y(II) under steady-state conditions, which were estimated by DIRK analysis (see

Section 4), are plotted in

Figure 5. vFd did not show a linear relationship with Y(II) in either WT or

pgr5hope1 (

Figure 5A). In WT, increasing Y(II) increased vFd, and a nearly linear relationship between vFd and Y(II) was found in the low range of Y(II) from 0.25 to 0.35. However, above Y(II) = 0.35, as Y(II) became saturated, vFd further increased. That is, excessive turnover of the redox reaction of Fd against Y(II) appeared in the higher range of Y(II). This behavior of vFd against Y(II) in

pgr5hope1 was similar to WT (

Figure 5A). In

pgr5hope1, a nearly linear relationship between vFd and Y(II) was found in the low range of Y(II) from 0.15 to 0.3. Above Y(II) = 0.3, although Y(II) became saturated, vFd further increased. The excessive turnover of the redox reaction of Fd against Y(II) in

pgr5hope1 also appeared in the higher range of Y(II), similar to WT. Surprisingly, the values of vFd were larger than those in WT. Typical kinetics of the oxidation of Fd after turning off the actinic light in the DIRK analysis were compared between WT and

pgr5hope1 at approximately the same two values of Y(II) (

Supplemental Figure S1A). At approximately 0.45 of Y(II), the initial decay rate of the reduced Fd in

pgr5hope1 was larger than that in WT. The reduced level of Fd before turning off the actinic light showed a reduced level at the steady state. At approximately 0.27 of Y(II) at lower Ci, the initial decay rate of the reduced Fd in

pgr5hope1 was also larger than that in WT (

Supplemental Figure S1B). Furthermore, vFd showed a dependence on the increase in qP (

Figure 5B). The increase in qP, reflecting PQ oxidation, stimulated the appearance of excessive vFd in WT and

pgr5hope1. That is, the activation of photosynthetic linear electron flow oxidized PQ and induced excessive vFd, as observed in the increase in Y(II).

Figure 5.

Relationships between the apparent quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII) [Y(II)], plastoquinone oxidized state (qP), and vFd. The data for each parameter were measured in the experiments depicted in

Figure 1, simultaneously with the gross CO

2 assimilation rates and Y(II). (

A) Y(II) was plotted against vFd. (

B) qP was plotted against vFd. In the experiments shown in

Figure 1, the oxidation rate of Fd was determined by DIRK analysis (see “

Section 4”). To determine the oxidation rate of Fd

− (vFd) under illuminated conditions, actinic light was transiently turned off for 400 ms. The initial slope of the decrease in Fd

− indicates vFd. These data were obtained at a steady state, which was confirmed by the achievement of stable conditions for both gross CO

2 assimilation and Y(II). The two vertical lines were drawn at approximately 0.27 and 0.45 of Y(II) to compare vFd between WT and

pgr5hope1. The data were obtained from four independent experiments using leaves attached to four WT and

pgr5hope1 plants (

N = 4). Black symbols, WT; white symbols,

pgr5hope1.

Figure 5.

Relationships between the apparent quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII) [Y(II)], plastoquinone oxidized state (qP), and vFd. The data for each parameter were measured in the experiments depicted in

Figure 1, simultaneously with the gross CO

2 assimilation rates and Y(II). (

A) Y(II) was plotted against vFd. (

B) qP was plotted against vFd. In the experiments shown in

Figure 1, the oxidation rate of Fd was determined by DIRK analysis (see “

Section 4”). To determine the oxidation rate of Fd

− (vFd) under illuminated conditions, actinic light was transiently turned off for 400 ms. The initial slope of the decrease in Fd

− indicates vFd. These data were obtained at a steady state, which was confirmed by the achievement of stable conditions for both gross CO

2 assimilation and Y(II). The two vertical lines were drawn at approximately 0.27 and 0.45 of Y(II) to compare vFd between WT and

pgr5hope1. The data were obtained from four independent experiments using leaves attached to four WT and

pgr5hope1 plants (

N = 4). Black symbols, WT; white symbols,

pgr5hope1.

3. Discussion

In the present research, we used

pgr5hope1 because

pgr5hope1 showed a higher reduced state of Fd at the steady state. Thus, we expected

pgr5hope1 to be a good experimental material to test the effect of Fd on Fd-CEF activity in vivo. We compared the activity of Fd-CEF in

Arabidopsis thaliana WT and

pgr5hope1. The mutant

pgr5hope1 shows the same values of both the gross CO

2 assimilation rate and the same reduction oxidation level of PQ as WT (

Figure 1) [

4,

23]. The oxidation rate of the reduced Fd showed a nonlinear relationship against Y(II) in both WT and

pgr5hope1 (

Figure 5A). The increase in vFd deviated from the increase in Y(II) in both WT and

pgr5hope1. These results indicate the presence of excessive vFd unrelated to photosynthetic linear electron flow, the electron flux in Fd-CEF (

Figure 5A) (Ohnishi et al. 2023). A deviation of vFd from the linear relationship was also found between vFd and qP in both WT and

pgr5hope1 (

Figure 5B). The increase in qP reflected the oxidation of the reduced PQ, which was induced by the stimulation of the photosynthetic linear electron flow. These characteristics of the expression of the excessive vFd corresponded to a previous report [

20]. That is, the appearance of Fd-CEF needed PQ oxidation in both WT and

pgr5hope1, which follows the molecular mechanism of Fd-CEF (

Supplemental Figure S2) [

1].

Furthermore, we found an enhanced oxidation rate of the reduced Fd in

pgr5hope1 compared to WT (

Figure 5A). That is, the electron flux of Fd-CEF in

pgr5hope1 was enhanced. In Fd-CEF, the reduced Fd donates electrons to PQ through FQR. The electron donor is the reduced Fd, and the electron acceptor is the oxidized PQ. The electron flux in Fd-CEF (vCEF) is proportional to the product of the concentrations of both the reduced Fd, [Fd

-], and the oxidized PQ, [PQ] and depends on the activity of FQR, the rate constant, k.

If PQ was completely reduced, the electron flux of Fd-CEF was zero, even if Fd was reduced (

Supplemental Figure S2) [

1,

20]. Conversely, if PQ was completely oxidized, the activity of Fd-CEF was also zero because Fd did not possess any electrons for the reduction of PQ [

1]. Similarly, if Fd was completely reduced with PQ completely reduced, Fd-CEF could not function. Furthermore, if Fd was completely oxidized with PQ completely oxidized, Fd-CEF could not function. In the present research, the reduction level of Fd in

pgr5hope1 was higher than that in WT, and Fd was further reduced by the decrease in photosynthetic linear electron transport (

Figure 2C). This was due to the suppression of P700 oxidation in

pgr5hope1 (

Figure 2A). In contrast to WT, the rate-determining step in the P700 photo-oxidation reduction cycle is the oxidation of the excited P700 by the electron acceptor in PSI of

pgr5hope1 [

4,

25], which was observed as the larger Y(NA) and the higher reduced level of Fd (

Figure 2 and

Figure 4). This was due to the lower ΔpH across thylakoid membranes in

pgr5hope1 compared to WT (

Supplemental Figure S3).

pgr5hope1 showed lower ΔpH because of the higher value of H

+-conductance (gH

+) compared to WT [

26]. However, the molecular mechanism by which gH

+ is decreased in

pgr5hope1 has not been elucidated. The observed lower ΔpH in

pgr5hope1 did not suppress the oxidation of the reduced PQ by the cytochrome

b6/

f-complex. As a result, the rate-determining step in the P700 photo-oxidation reduction cycle in

pgr5hope1 would shift from the reduction of the oxidized P700 to the oxidation of the excited P700. This is the reason for the enhanced reduction in Fd in

pgr5hope1, which was further strengthened in response to the suppression of photosynthetic linear electron transport. Following the expression model of Fd-CEF activity (Equation 1), the increase in [Fd

-] increases vCEF. In fact, at the same qP values, e.g., 0.4 and 0.6, that is, the same [PQ], vFd in

pgr5hope1 was higher than that in WT (

Figure 5B). These behaviors of vCEF followed the Fd-CEF model (

Supplemental Figure S2) [

1]. That is, Fd-CEF requires both oxidized PQ and reduced Fd in vivo.

The contribution of Fd-CEF to the induction of ΔpH across thylakoid membranes has been discussed [

1,

27]. Although ΔpH in

pgr5hope1 was lower than that in WT (

Supplemental Figure S3), ΔpH in both WT and

pgr5hope1 did not increase in response to the increase in Fd-CEF from the CO

2 compensation point to the higher Ci (

Supplemental Figure S3). The increase in Fd-CEF activity was accompanied by the stimulation of the gross CO

2 assimilation rate as Ci increased (

Figure 1 and

Figure 5). That is, the increase in ATP consumption occurred simultaneously with the increase in Fd-CEF activity. Therefore, the ΔpH induced by Fd-CEF did not accumulate, or the total ΔpH induced by the enhanced photosynthetic linear electron flow (the light reaction in photosynthesis) driven by the net CO

2 assimilation (the dark reaction in photosynthesis) and the enhanced Fd-CEF (the light reaction in photosynthesis) greatly decreased.

NPQ in

pgr5hope1 was lower than that of WT (

Figure 3). The induction of NPQ requires acidification of the luminal side of thylakoid membranes [

27]. That is, the lower ΔpH in

pgr5hope1 could not induce higher NPQ. On the other hand, the behavior of NPQ in WT relative to the increase in both the gross CO

2 assimilation rate and the photosynthetic linear electron flow rate was the same as that in

pgr5hope1 (

Figure 3). NPQ decreased with the increase in both the gross CO

2 assimilation rate and the photosynthetic linear electron flow rate, although ΔpH in both WT and

pgr5hope1 did not change, as described above. NPQ also depends on the reduction‒oxidation state of PQ and Y(II) [

28,

29]. That is, NPQ decreases with the increases in both qP and Y(II).

In the present research, we further confirmed the expression model of Fd-CEF activity proposed (

Supplemental Figure S2) [

1]. The mutant

pgr5hope1 showed a higher reduction in Fd than WT (

Figure 2). As expected, the electron flux of Fd-CEF in

pgr5hope1 was enhanced (

Figure 5). Both pgr5 and NDH have been considered mediators of Fd-CEF [

11]. However, the present and previous reports clearly show that Fd-CEF is driven by a new mediator [

20]. The strongest candidate for the mediator, FQR, is the cytochrome (Cyt)

b6/

f-complex [

30,

31,

32]. The Cyt

b6/

f-complex has a possible binding site for Fd, close to the location of heme

c, composed of basic amino groups. The acidic region of Fd would bind to the site of the Cyt

b6/

f complex. The reduced heme

c would transfer electrons to the low potential heme

b in the Cyt

b subunit of the Cyt

b6/

f-complex [

30,

32]. The reduced heme

b donates electrons to the oxidized PQ and/or the one-electron reduced PQ in the Q-cycle of the Cyt

b6/

f-complex. The cyclic electron flow accelerates the Q-cycle and contributes to ΔpH formation. Identification of the mediator for Fd-CEF would require further research.

Next, we considered that we obtained the most important information about the physiological function of Fd-CEF in

pgr5hope1. The mutant

pgr5hope1 has high H

+-conductance (

Supplemental Figures S3 and S4), which has been reported by many researchers [

9,

10]. Unless Fd-CEF induces acidification of the luminal space of thylakoid membranes, the proton motive force to produce ATP should not be maintained. The enhanced electron flux in Fd-CEF of

pgr5hope1 would compensate for the rapid loss of the proton motive force by promoting ΔpH formation across thylakoid membranes. That is, as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 5, the higher activity of Fd-CEF

pgr5hope1 drives CO

2 assimilation at the same rate as WT.

Furthermore, the physiological function of Fd-CEF is considered as follows. The electron flux of Fd-CEF is induced by the oxidation of PQ, which is triggered by the increase in the rate of photosynthetic electron flow driven by the dark reactions: CO

2 assimilation and photorespiration (

Figure 1 and

Figure 5) [

20]. The electrons for driving the dark reactions are supplied as both NADPH and Fd, and the electrons originate from H

2O oxidation in PSII. In vivo, the electron flux in the photosynthetic linear electron flow has a linear relationship with the consumption rate of electrons in dark reactions with the origin [

25,

33,

34,

35,

36]. This robust relationship between the light and dark reactions has persisted since the origin of photosynthesis. In principle, the linear relationship cannot be accounted for by photosynthetic linear electron transport. The electron flux in the photosynthetic linear electron flow, Je(LEF), is equal to the electron consumption rate in the dark reaction, Jg. Then,

The production rate of H

+ in the lumen by the photosynthetic linear electron flow, vP(H

+), and the consumption rate of H

+ in the dark reaction, vC(H

+), are

The coefficient of 3 in Equation (3) shows the H

+/e

- ratio in the photosynthetic linear electron flow with the Q-cycle [

2,

37,

38]. The coefficient of [2.335 × (3 + 3.5ϕ)/(2+2ϕ)] in Equation (4) shows the H

+/e

- ratio in the dark reaction [

2,

37,

38]. The value of ϕ is the ratio of the ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) oxygenation reaction rate to the RuBP carboxylation rate catalyzed by RuBP carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco). At the CO

2 compensation point, ϕ = 2, and at higher CO

2, ϕ = 0. From Equation (2),

That is, the photosynthetic linear electron flow cannot supply enough ATP to drive the dark reaction, a very dangerous situation for photosynthetic organisms. Here, we imagine the reverse situation but with the same results as described above. On the assumption that the dark reaction turns over with the insufficient supply of ATP, then the dark reaction rate is determined by the supply rate of ATP in the photosynthetic linear electron flow,

From Equations (3) and (4),

Equation (7) indicates that the dark reaction cannot consume all the electrons produced in the photosynthetic linear electron flow. As the amounts of both NADP

+ and the oxidized Fd are not infinite, as soon as both NADP

+ and the oxidized Fd are perfectly reduced, the photosynthetic linear electron transport (PET) system would be filled with electrons. Equation (7) shows that the pressure of electron accumulation in the PET system would be accelerated as the dark reaction rate increases. Once electrons accumulate at the acceptor side of PSI, ROS are produced, and ROS oxidatively degrade PSI via photoinhibition [

4,

39]. That is, the functioning of the photosynthetic linear electron flow has a potential threat to ROS production in PSI.

On the other hand, Equation (7) does not hold. The robust linear relationship of Je(LEF) against Jg shows that Je(LEF) is equal to Jg [

25,

33,

34,

35,

36]. This fact shows that the extra ATP supply reaction to the dark reaction functions without electron production. Fd-CEF supplies ATP to accelerate the consumption of NADPH, and this function of Fd-CEF can simultaneously accelerate the dark reaction. As a result, Jg is enhanced, and the linear relationship of Je(LEF) against Jg holds. Fd-CEF has a dual function to suppress ROS production and to enhance the dark reaction. As a higher CO

2 assimilation rate is needed, the activity of Fe-CEF increases (

Figure 5). This is a reasonable response of Fd-CEF because the threat of ROS production also increases, as described above and shown in Equation (7).

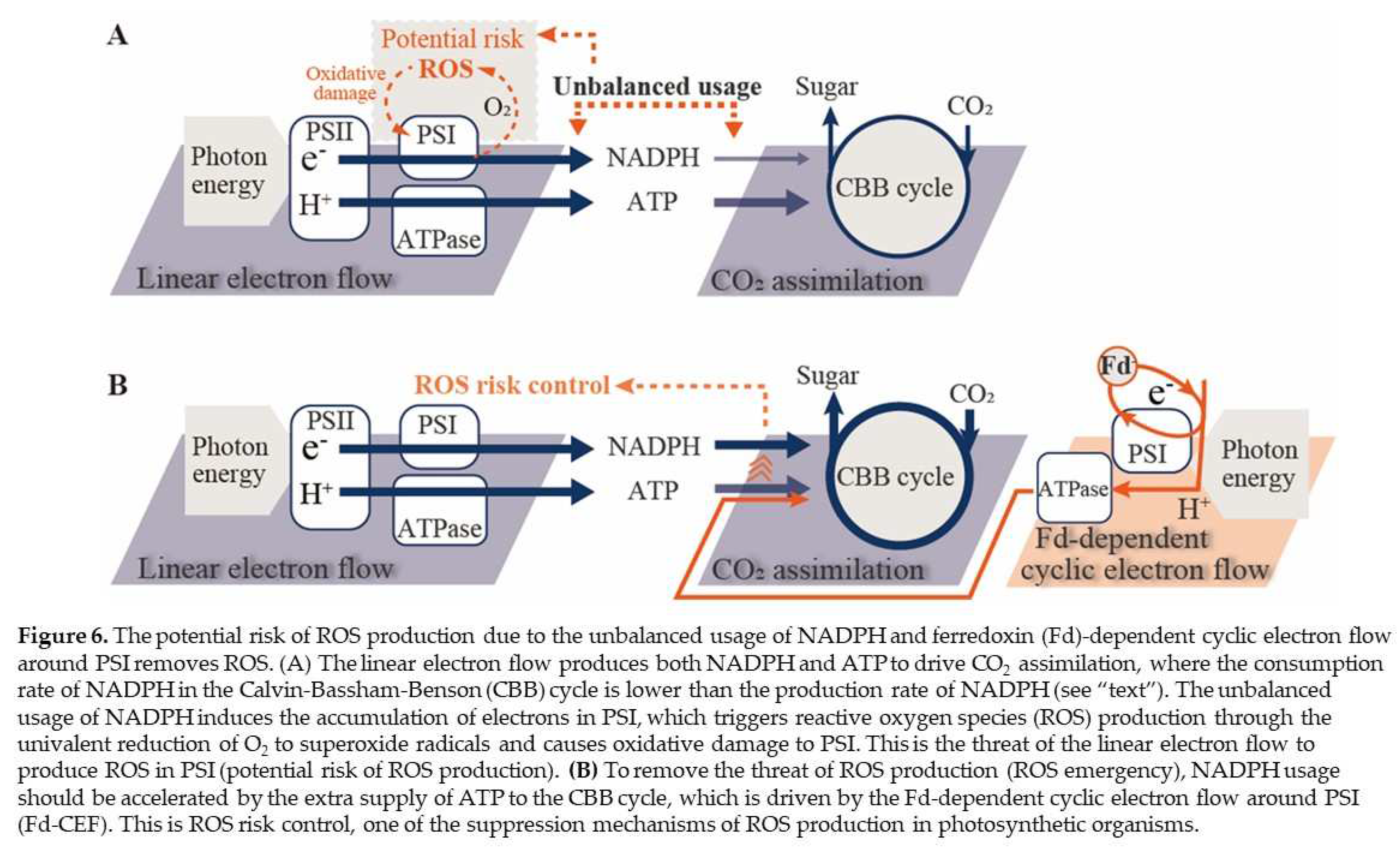

As described above, the threat of ROS production potentially brought by the photosynthetic linear electron flow increases with the stimulation of the dark reaction. In response to the increased threat of ROS production, the oxidation of PQ is enhanced, which activates Fd-CEF. Fd-CEF promotes the consumption of NADPH by supplying ATP to the dark reaction. This is the suppression mechanism of ROS production (

Figure 6). On the other hand, the suppression of the dark reaction under environmental stress, e.g., high/low temperatures, water deficits, nutrient deficits, and high salt contents, induce a reduction in PQ, as observed in the suppression of photosynthetic linear electron flow. Under these situations, Fd-CEF cannot function (

Figure 5) [

20]. However, as observed in the oxidation of P700 in PSI, the electron flow from PSII to PSI is suppressed [

25,

40,

41,

42]. This contributes to the alleviation of electron accumulation at the acceptor side of PSI, which inhibits ROS production [

4]. On the other hand, the oxidation of P700 is suppressed by the stimulation of the dark reaction (

Figure 2). That is, only Fd-CEF can remove the threat of ROS production under higher photosynthetic conditions. Oxygenic photosynthetic organisms have two suppression mechanisms of ROS production in PSI of the photosynthetic electron transport system: P700 oxidation and Fd-CEF. Fd-CEF can function under high CO

2 conditions, which enhances CO

2 assimilation, and Fd-CEF can remove the threat of ROS production by increasing Jg. The second mechanism, Fd-CEF, would have been needed at the start of the evolution of photosynthetic organisms during the ancient era, where the atmospheric partial pressure of CO

2 was much higher than the present CO

2 [

43]. Now, photosynthetic organisms should activate Fd-CEF in response to the enhanced CO

2 assimilation accelerated by the increase in atmospheric CO

2 partial pressure, causing global boiling after global warming. The activated Fd-CEF makes safe photosynthesis possible.