Submitted:

17 January 2024

Posted:

17 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Strains and Cultivation

3.2. RT-qPCR

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wexler, H.M. Bacteroides: the good, the bad and the nitty-gritty. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007, 20, 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingsdag, S.A.; Hunter, N. Metronidazole: an update on metabolism, structure-cytotoxicity and resistance mechanisms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018, 73, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy EU, E.; Nord, C. E. on behalf of the ESCMID Study Group on Antimicrobial Resistance in Anaerobic Bacteria. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Bacteroides fragilis group isolates in Europe 20 years of experience. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2011, 17, 371–379.

- Sethi, S.; Shukla, R.; Bala, K.; Gautam, V.; Angrup, A.; Ray, P. Emerging metronidazole resistance in Bacteroides spp. and its association with the nim gene: a study from North India. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019, 16, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

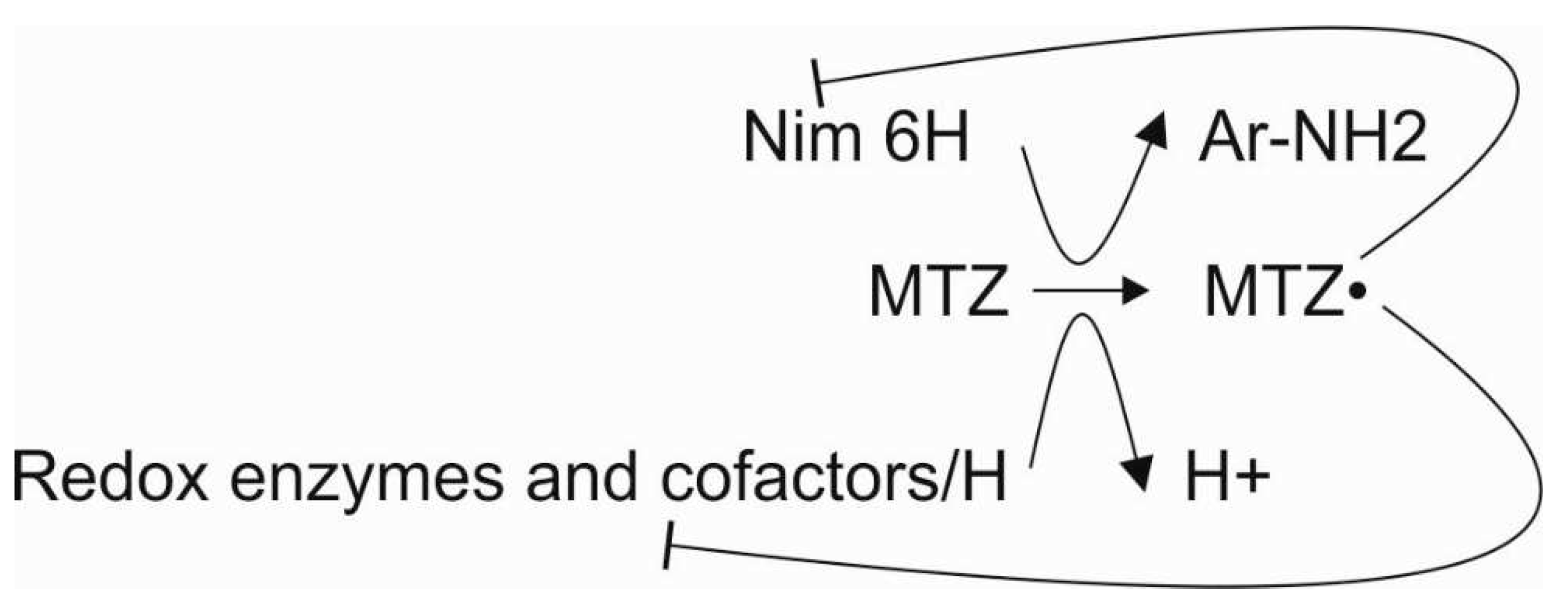

- Alauzet, C.; Lozniewski, A.; Marchandin, H. Metronidazole resistance and nim genes in anaerobes: A review. Anaerobe. 2019, 55, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlier, J.P.; Sellier, N.; Rager, M.N.; Reysset, G. Metabolism of a 5-nitroimidazole in susceptible and resistant isogenic strains of Bacteroides fragilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaitan, A.O.; Dureja, C.; Youngblom, M.A.; Topf, M.A.; Shen, W.J.; Gonzales-Luna, A.J.; et al. Decoding a cryptic mechanism of metronidazole resistance among globally disseminated fluoroquinolone-resistant Clostridioides difficile. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, B.; Juhász, H.; Leitsch, D.; Sóki, J. The effects of identical nim gene-insertion sequence combinations on the expression of the nim genes and metronidazole resistance in Bacteroides fragilis strains. Anaerobe. 2023, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sóki, J.; Keszőcze, A.; Nagy, I.; Burián, K.; Nagy, E. An update on ampicillin resistance and β-lactamase genes of Bacteroides spp. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2021, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paunkov, A.; Gutenbrunner, K.; Sóki, J.; Leitsch, D. Haemin deprivation renders Bacteroides fragilis hypersusceptible to metronidazole and cancels high-level metronidazole resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paunkov, A.; Hummel, K.; Strasser, D.; Sóki, J.; Leitsch, D. Proteomic analysis of metronidazole resistance in the human facultative pathogen Bacteroides fragilis. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfmark, S.; Fang, H.; Hedberg, M.; Edlund, C. Inducible metronidazole resistance and nim genes in clinical Bacteroides fragilis group isolates. AntimicrobAgents Chemother. 2005, 49, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sóki, J.; Fodor, E.; Hecht, D.W.; Edwards, R.; Rotimi, V.O.; Kerekes, I.; et al. Molecular characterization of imipenem-resistant, cfiA-positive Bacteroides fragilis isolates from the USA, Hungary and Kuwait. Journal of medical microbiology. 2004, 53, 413–419; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baaity, Z.; Jamal, W.; Rotimi, V.O.; Burián, K.; Leitsch, D.; Somogyvári, F.; et al. Molecular characterization of metronidazole resistant Bacteroides strains from Kuwait. Anaerobe. 2021, 69, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wareham, D.W.; Wilks, M.; Ahmed, D.; Brazier, J.S.; Miller, M. Anaerobic sepsis due to multidrug-resistant Bacteroides fragilis: microbiological cure and clinical response with linezolid therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 40, e67-e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podglajen, I.; Breuil, J.; Casin, I.; Collatz, E. Genotypic identification of two groups within the species Bacteroides fragilis by ribotyping and by analysis of PCR-generated fragment patterns and insertion sequence content. Journal of Bacteriology. 1995, 177, 5270–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sárvári, K.P.; Sóki, J.; Kristóf, K.; Juhász, E.; Miszti, C.; Latkóczy, K.; et al. A multicentre survey of the antibiotic susceptibility of clinical Bacteroides species from Hungary. Infectious Diseases. 2018, 50, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Privitera, G.; Sebald, M.; Fayolle, F. Common regulatory mechanism of expression and conjugative ability of a tetracycline resistance plasmid in Bacteroides fragilis. Nature. 1979, 278, 657–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sóki, J.; Gal, M.; Brazier, J.S.; Rotimi, V.O.; Urbán, E.; Nagy, E.; et al. Molecular investigation of genetic elements contributing to metronidazole resistance in Bacteroides strains. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006, 57, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reysset, G. Genetics of 5-nitroimidazole resistance in Bacteroides species. Anaerobe. 1996, 2, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, F.; Veeranagouda, Y.; Hsi, J.; Meggersee, R.; Abratt, V.; Wexler, H.M. Two multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Bacteroides fragilis carry a novel metronidazole resistance nim gene (nimJ). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3767–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishwanath, S.; Shenoy, P.A.; Chawla, K. Antimicrobial Resistance Profile and Nim Gene Detection among Bacteroides fragilis Group Isolates in a University Hospital in South India. J Glob Infect Dis. 2019, 11, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baughn, A.D.; Malamy, M.H. The essential role of fumarate reductase in haem-dependent growth stimulation of Bacteroides fragilis. Microbiology (Reading). 2003, 149 Pt 6, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeranagouda, Y.; Husain, F.; Boente, R.; Moore, J.; Smith, C.J.; Rocha, E.R.; et al. Deficiency of the ferrous iron transporter FeoAB is linked with metronidazole resistance in Bacteroides fragilis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014, 69, 2634–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, C.G.; Farias, L.M.; Carvalho, M.A.; Rocha, E.R.; Smith, C.J. Differential gene expression in a Bacteroides fragilis metronidazole-resistant mutant. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004, 54, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynen, M.A.; Dandekar, T.; Bork, P. Variation and evolution of the citric-acid cycle: a genomic perspective. Trends Microbiol. 1999, 7, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baughn, A.D.; Malamy, M.H. A mitochondrial-like aconitase in the bacterium Bacteroides fragilis: implications for the evolution of the mitochondrial Krebs cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002, 99, 4662–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boekhoud, I.M.; Sidorov, I.; Nooij, S.; Harmanus, C.; Bos-Sanders, I.; Viprey, V.; et al. Haem is crucial for medium-dependent metronidazole resistance in clinical isolates of Clostridioides difficile. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021, 76, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janausch, I.G.; Zientz, E.; Tran, Q.H.; Kröger, A.; Unden, G. C4-dicarboxylate carriers and sensors in bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002, 1553, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narikawa, S.; Suzuki, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Nakamura, M. Lactate dehydrogenase activity as a cause of metronidazole resistance in Bacteroides fragilis NCTC 11295. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991, 28, 47–53; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paunkov, A.; Sóki, J.; Leitsch, D. Modulation of Iron Import and Metronidazole Resistance in Bacteroides fragilis Harboring a nimA Gene. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 898453; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Freitas, M.C.; Resende, J.A.; Ferreira-Machado, A.B.; Saji, G.D.; de Vasconcelos, A.T.; da Silva, V.L.; et al. Exploratory Investigation of Bacteroides fragilis Transcriptional Response during In vitro Exposure to Subinhibitory Concentration of Metronidazole. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitsch, D.; Kolarich, D.; Wilson, I.B.; Altmann, F.; Duchêne, M. Nitroimidazole action in Entamoeba histolytica: a central role for thioredoxin reductase. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| B. fragilis | MTZ MIC (µg/ml) |

nim (IS) |

nim experession (Rq) |

cfiA | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBR13 | >256 | E (ISBf6) | 0,352 | + | [12] |

| 388/2 | >256 | E (ISBf6) | 1,778 | + | [13] |

| Q5 | 256 | E (ISBf6) | 1,411 | + | [14] |

| 20584 | 256 | E (ISBf6) | 1 | + | This study |

| Q6 | 256 | E (ISBf6) | 0,187 | - | [14] |

| DOR18i3 | 256 | D (IS1169) | 0,403 | + | This study |

| 18807i2 | (0.5-)>256a | - | n.a. | - | This study |

| Q11 | 64 | E (ISBf6) | 0,856 | + | [14] |

| WI1 | 32 | - | n.a. | + | [15] |

| KSB-R | 32 | B (IS1186) | 0,109 | + | [16] |

| SY46 | 0,25 | - | n.a. | - | [17] |

| SZ69 | 0,25 | - | n.a. | + | [17] |

| 638R | 0,125 | - | n.a. | - | [18] |

| SZ26 | 0,125 | - | n.a. | + | [17] |

| SE61 | 0,064 | - | n.a. | - | [17] |

| S3 | acr5 | acr15 | crpF | frdC | feoAB | fldA | fprA | frdA | galK | gatMZ | ldh | mdh | nanH | porMZ | pgk | relA | MICb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L20 | 0,486 | -0,318 | 0,243 | -0,346 | 0,725 | 0,0393 | -0,479 | 0,421 | 0,789 | 0,154 | 0,149 | -0,0964 | 0,621 | -0,393 | 0,257 | 0,704 | 0,679 | -0,423 |

| 0,0639 | 0,24 | 0,374 | 0,199 | 0,00178 | 0,883 | 0,0685 | 0,113 | 2E-07 | 0,575 | 0,584 | 0,724 | 0,0129 | 0,142 | 0,346 | 0,00302 | 0,00504 | 0,113 | |

| S3 | 0,214 | 0,429 | -0,296 | 0,511 | -0,175 | 0,025 | 0,275 | 0,443 | 0,579 | 0,31 | 0,0286 | 0,421 | -0,321 | 0,414 | 0,643 | 0,614 | -0,25 | |

| 0,433 | 0,107 | 0,275 | 0,0498 | 0,523 | 0,923 | 0,312 | 0,0946 | 0,0231 | 0,252 | 0,913 | 0,113 | 0,235 | 0,12 | 0,00934 | 0,0143 | 0,359 | ||

| acr5 | 0,461 | 0,136 | -0,343 | -0,113 | 0,393 | 0,05 | -0,132 | 0,486 | -0,125 | 0,211 | -0,111 | 0,25 | 0,443 | -0,0536 | -0,168 | 0,227 | ||

| 0,0808 | 0,62 | 0,204 | 0,676 | 0,142 | 0,852 | 0,629 | 0,0639 | 0,648 | 0,441 | 0,686 | 0,359 | 0,0946 | 0,842 | 0,54 | 0,41 | |||

| acr15 | 0,4 | -0,0179 | -0,0536 | 0,0821 | 0,307 | 0,546 | 0,629 | -0,133 | 0,664 | 0,0107 | 0,343 | 0,639 | 0,125 | 0,104 | 0,132 | |||

| 0,134 | 0,944 | 0,842 | 0,763 | 0,257 | 0,0339 | 0,0116 | 0,629 | 0,00654 | 0,964 | 0,204 | 0,00988 | 0,648 | 0,705 | 0,629 | ||||

| crpF | -0,3 | 0,211 | 0,0929 | -0,214 | 0,0429 | 0,075 | -0,262 | 0,646 | -0,25 | 0,468 | 0,439 | -0,368 | -0,25 | 0,491 | ||||

| 0,269 | 0,441 | 0,734 | 0,433 | 0,873 | 0,783 | 0,339 | 0,00882 | 0,359 | 0,0757 | 0,0975 | 0,171 | 0,359 | 0,0597 | |||||

| frdC | 0,179 | -0,336 | 0,486 | 0,593 | -0,193 | 0,528 | -0,311 | 0,7 | -0,614 | 0,25 | 0,75 | 0,814 | -0,669 | |||||

| 0,514 | 0,214 | 0,0639 | 0,0192 | 0,481 | 0,0413 | 0,252 | 0,00326 | 0,0143 | 0,359 | 0,000786 | 2E-07 | 0,00614 | ||||||

| feoAB | 0,259 | 0,45 | -0,132 | -0,37 | -0,0403 | 0,247 | 0,182 | -0,316 | 0,39 | -0,218 | 0,261 | -0,0118 | ||||||

| 0,339 | 0,0889 | 0,629 | 0,167 | 0,883 | 0,367 | 0,506 | 0,24 | 0,146 | 0,426 | 0,339 | 0,964 | |||||||

| fldA | -0,05 | -0,536 | 0,118 | -0,0685 | 0,468 | -0,207 | 0,286 | 0,143 | -0,386 | -0,0429 | 0,274 | |||||||

| 0,852 | 0,0382 | 0,667 | 0,802 | 0,0757 | 0,449 | 0,293 | 0,602 | 0,15 | 0,873 | 0,312 | ||||||||

| fprA | 0,218 | -0,179 | 0,27 | -0,0536 | 0,575 | -0,454 | 0,386 | 0,461 | 0,471 | -0,426 | ||||||||

| 0,426 | 0,514 | 0,319 | 0,842 | 0,0241 | 0,0861 | 0,15 | 0,0808 | 0,0732 | 0,11 | |||||||||

| frdA | 0,279 | 0,157 | 0,143 | 0,393 | -0,1 | 0,357 | 0,55 | 0,489 | -0,361 | |||||||||

| 0,306 | 0,566 | 0,602 | 0,142 | 0,714 | 0,185 | 0,0325 | 0,0618 | 0,18 | ||||||||||

| galK | -0,475 | 0,482 | -0,25 | 0,382 | 0,339 | 0,0643 | -0,075 | 0,457 | ||||||||||

| 0,0708 | 0,0662 | 0,359 | 0,154 | 0,209 | 0,812 | 0,783 | 0,0834 | |||||||||||

| gatMZ | -0,5 | 0,596 | -0,58 | -0,00403 | 0,463 | 0,483 | -0,683 | |||||||||||

| 0,0556 | 0,0183 | 0,0231 | 0,985 | 0,0782 | 0,0662 | 0,00471 | ||||||||||||

| ldh | -0,3 | 0,564 | 0,421 | -0,346 | -0,0893 | 0,517 | ||||||||||||

| 0,269 | 0,0275 | 0,113 | 0,199 | 0,743 | 0,0463 | |||||||||||||

| mdh | -0,689 | 0,364 | 0,836 | 0,825 | -0,528 | |||||||||||||

| 0,00409 | 0,176 | 2E-07 | 2E-07 | 0,0413 | ||||||||||||||

| nanH | -0,0214 | -0,521 | -0,543 | 0,446 | ||||||||||||||

| 0,934 | 0,0446 | 0,0353 | 0,0917 | |||||||||||||||

| porMZ | 0,254 | 0,45 | 0,0798 | |||||||||||||||

| 0,353 | 0,0889 | 0,773 | ||||||||||||||||

| pgk | 0,786 | -0,586 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2E-07 | 0,0211 | |||||||||||||||||

| relA | -0,629 | |||||||||||||||||

| 0,0116 |

| L20 | S3 | acr5 | acr15 | crpF | frdC | feoAB | fldA | fprA | frdA | galK | gatMZ | ldh | mdh | nanH | porMZ | pgk | relA | MIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nim | n.s.a | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.006 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.029 | n.s. | 0.001 | 0.04 | n.s. | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| cfiA | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).