Introduction

Tourism has grown in importance as a fundamental business that creates jobs and promotes economic diversity. This translates into enormous economic potential, providing impetus for infrastructure development in coastal regions also, which considerably influences land use, land cover, and socioeconomic dynamics (Miller & Auyong, 1991). The coastal region is one of the most important contributors to global tourism (Papageorgiou, 2016)It constitutes approximately 50 percent of all global tourism, equal to US$4.6 trillion or 5.2 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) and It is a vital component of the economy of small islands and coastal communities (Northcorp,2020)Tourism managers often encourage ecotourism in these regions to capitalize on their natural beauty, leading to significant infrastructure development in coastal areas. Since then, coasts have been at the forefront of tourism infrastructure development. The presence of a considerable number of visitors has frequently had a detrimental impact on the sustainable utilization of available resources (Sun & Gao, 2012) (Farrell & Runyan, 1991). This, in turn, worsens living conditions in coastal locations, with consequences felt by both the local people and environment alike (Gössling, 2001).

Studies show that local communities recognize the economic potential of tourism but want it to thrive without compromising social and environmental consequences (Liu & Var, 1986; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2010). However, concerns about its potential impacts on local communities and their quality of life persist, as highlighted by (Crotts & Holland, 1993). Concerns include the loss of cultural identity, increased living costs, and congestion. To ensure the long-term survival of the community and the environment, tourist development must be carefully managed and regulated.

Case of Maya Bay

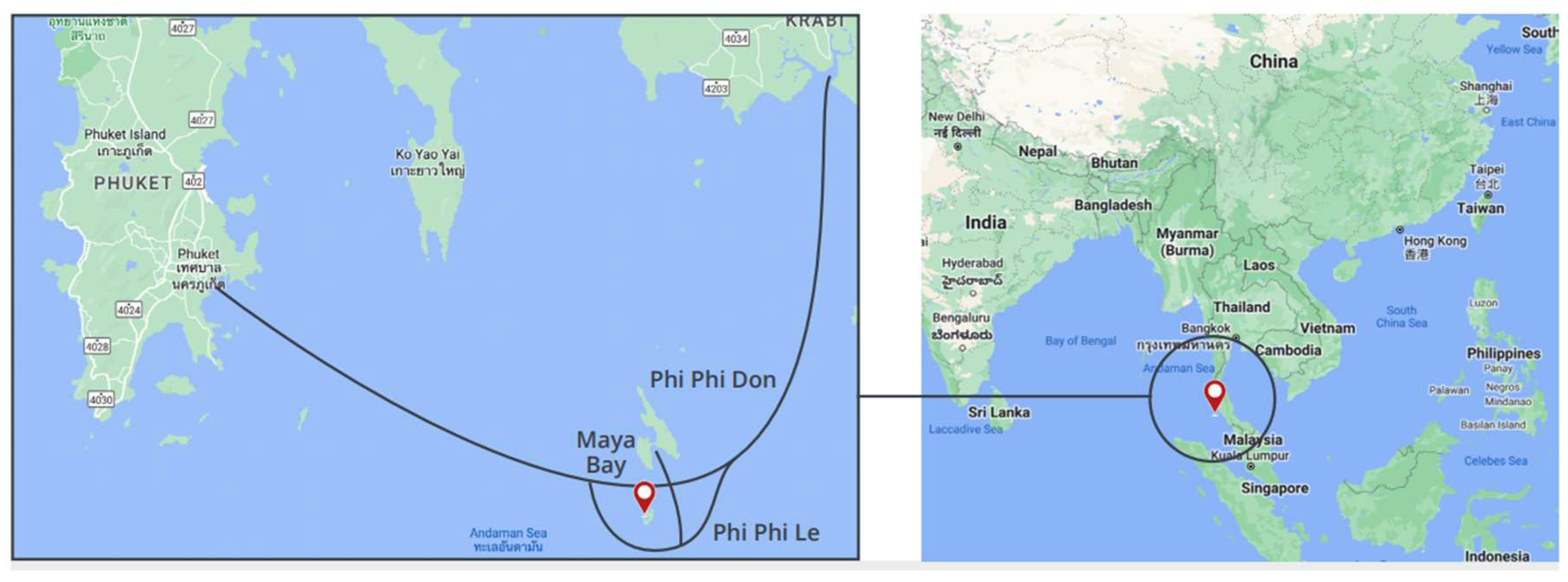

Maya Bay is in Krabi Province, southern Thailand, and is part of the Hat Noppharat Thara-Mu Ko Phi Phi National Park. Established in 1983, the marine park is a popular tourist attraction recognized for its white sand beaches, mangroves, coral reefs, clean seas, and steep limestone cliffs (

Phi Phi Islands, n.d.). The park’s most popular spot is the little cove known as Maya Bay, which is located on Phi Phi Le Island and gained fame with the release of the 2000 film The Beach, starring Leonardo DiCaprio. In fact, the film was a major driving force in the area’s tourism growth, particularly on Phi Phi Don, Phi Phi Le’s sister island, where development is permitted. (Taylor, 2018). Thailand’s tourism sector had been continuously rising prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, hitting a record high of 39 million visitor arrivals in 2019 (Pacific Asia Travel Association, 2022).

Figure 1.

Map of Maya Bay. Phi Phi Don ferry routes from Phuket and Krabi, Southern Thailand.

Source: Destination Spotlight: Managing Overtourism and Environmental Impacts in Thailand’s Maya Bay (

ecornell.s3.amazonaws.com).

Figure 1.

Map of Maya Bay. Phi Phi Don ferry routes from Phuket and Krabi, Southern Thailand.

Source: Destination Spotlight: Managing Overtourism and Environmental Impacts in Thailand’s Maya Bay (

ecornell.s3.amazonaws.com).

On an average, the Phi Phi Islands and Maya Bay drew a large number of visitors. Maya Bay had between 3,500 and 5,000 tourists each day on average (Cripps, 2022). Tourism swiftly grew in popularity, causing substantial environmental, sociocultural, and economic repercussions on the destination (Epler Wood et al., 2019) and, increasingly, a bad tourist experience for visitors.

Since tourists are not permitted to stay the night in the bay due to its protected status, they would come on boat trips from Phi Phi Don, Phuket, or Krabi to spend a few hours on the beach. But the growing demand for hotels and the substantial number of landowners "all wishing to capitalize on their assets" (Taylor, 2018) on a tiny (3.76 mi2) island caused considerable demonstrable environmental consequences.

The pollution caused by boats (noise, oil) and visitors (trash, chemical sunscreen), their irresponsible behavior (e.g., stepping on corals), and the substantial number of daily visitors made it impossible to prevent severe degradation of Maya Bay’s ecosystem (Cripps, 2022) (BBC News,2019) (Bangkok Post, 2018). Sand erosion, caused by the enormous number of people strolling on the beach, interfering with the natural process of sediment replenishment (Bangkok Post, 2018). Finally, boats and humans on the sea were displacing marine creatures. Rapid and unmanaged tourism expansion resulted in poor waste management, water scarcity, floods, congestion, and pollution (Taylor, 2018; Koh & Fakfare, 2019). According to environmentalists, the percentage of surviving corals in the bay has plummeted by 92% as of 2018 (BBC News,2019).

This made residents of Phi Phi Don voice their concern about the local ecosystem, and in 2015, they petitioned the Department of National Parks, Wildlife, and Plant Conservation (DNP) to close Maya Bay for six months each year (Koh & Fakfare, 2019).

At an event on May 15, the DNP announced that Maya Bay will remain closed to tourists for four months for restoration (Koh & Fakfare, 2019). Because of the COVID-19 epidemic, the shutdown lasted three and a half years.

The closure had a significant impact on tourism business operations, requiring businesses to quickly change contracts with overseas tour operators, cancel bookings, handle customer reimbursements and complaints, and inform potential visitors that tourism activities in Phi Phi Don and other islands continued as usual. During this time, the agency would review the "condition of reef and beach resources, environmental control, and tourism management", according to Thailand’s DNP.

Despite these economic ramifications, companies recognized and agreed on the need to restore the coral reefs and beaches, as well as establish more sustainable tourist practices in the region. Maya Bay’s closure highlighted local stakeholders’ increased knowledge of the essential and satisfactory results of seasonal closures of Thailand’s high-use national parks (Koh & Fakfare, 2019).

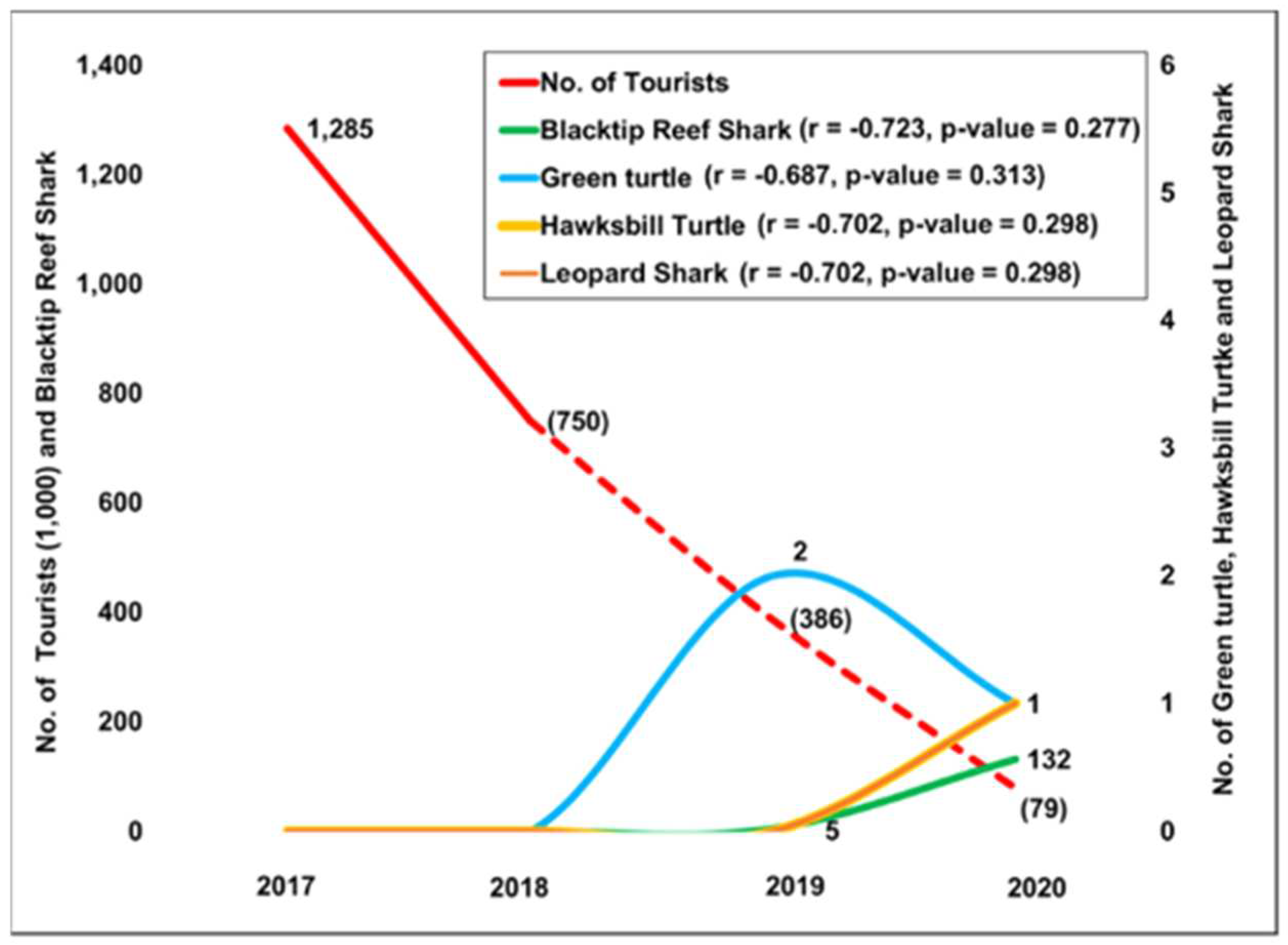

With fewer tourists visiting in 2020, the authority recorded as many as 132 blacktip reef sharks, as well as a small number of leopard sharks, hawksbill turtles, and green turtles near Maya Bay.

Figure 2. empirically demonstrate the benefit of closing the bay: “The Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between the number of tourists and marine animal sightings are negative, as expected.” (Israngkura, 2022).

When the marine park reopened in January 2022, the tourist management mechanisms got adjusted in numerous ways to guarantee that the regeneration and conservation efforts would not be swiftly overturned once tourism resumed.

First, the DNP has divided the entire number of permitted tourists into one-hour periods with a maximum of 375 people per slot, for a total of 4,125 tourists every day. The slots, which begin at 7 a.m., booked online via an app or through a travel operator (Smith,2022).

Second, no vessels are authorized to enter the bay. Visitors must drop off on the other side of the island on a floating dock. Only eight boats may dock at once (Smith,2022) (Cripps, 2022).

Third, boardwalks from the pier to the beach got constructed to keep guests off the vegetation (Smith,2022).

Finally, visitors were not allowed to swim in the bay to avoid disturbing the fauna (particularly black-tipped sharks) or damaging the corals (Cripps, 2022).

The administration of Maya Bay confronts multiple obstacles in balancing the needs of the local economy, the fragile ecosystem, and visitors. For example, the local economy is strongly reliant on tourist earnings from Maya Bay, and any limits or prohibitions imposed on visitor numbers or activities might have serious economic consequences for the town. However, the sensitive ecology of Maya Bay is at risk of additional degradation because of excessive tourism, necessitating the implementation of protective and restoration measures. Furthermore, people who remember Maya Bay from the iconic movie scene have certain expectations and wishes and providing them while maintaining sustainability might be challenging for the authorities. As Thailand's tourist visits are expected to return to pre-pandemic levels by 2024 (Pacific Asia Travel Association, 2022), Thai authorities must continue the national park's regeneration and sustainability measures in the long term, as they are already serving as a model of successful intervention for places around the world threatened by overtourism.

Overview of Lakshadweep

"Lakshadweep”, the group of 36 islands, is known for its exotic and sun-kissed beaches and lush green landscape. The name Lakshadweep in Malayalam and Sanskrit means ‘a hundred thousand islands."

India’s smallest Union Territory, Lakshadweep, is an archipelago consisting of 36 islands with an area of 32 sq km. It is a uni-district Union Territory and comprises 12 atolls, three reefs, five submerged banks, and ten inhabited islands. The islands have a total area of 32 sq km. The capital is Kavaratti, and it is also the principal town of the UT. All islands are 220 to 440 km away from the coastal city of Kochi in Kerala, in the emerald Arabian Sea. The natural landscapes, the sandy beaches, the abundance of flora and fauna, and the absence of a rushed lifestyle enhance the mystique of Lakshadweep (Lakshadweep | Official Website of Administration of Lakshadweep | India, n.d.).

However, entry to the Lakshadweep Islands is restricted. One requires an entry permit issued by the Lakshadweep Administration to visit these islands (

Lakshadweep | Official Website of the Administration of Lakshadweep | India, n.d.).

Figure 1. highlights the list of Lakshadweep administration entry permit issuing authorities at the time of retrieval of the document. In addition to this, visitors must give their consent to THE LACCADIVE MINICOY AND AMINDIVI ISLANDS (RESTRICTIONS ON ENTRY AND RESIDENCE) RULES, 1967 (Entry

Permit Rules Lakshadweep, n.d.) before entering the islands.

Tourism in Lakshadweep

Tourism in Lakshadweep is managed by the Society for Promotion of Nature Tourism and Sports (SPORTS), a society formed by the Lakshadweep Administration in 1982 with the avowed aim of tapping the tourism potential of the islands and acting as the nodal agency of the Lakshadweep Administration for the promotion of tourism in the islands. The primary aim of the organization is to promote eco-friendly tourism and recreational activities in the islands in association with and under the guidance of the Lakshadweep Administration (Society for Promotion of Nature Tourism and Sports—Lakshadweep Tourism, n.d.).

Tourism Products of Lakshadweep

All the islands included in the various tourist packages offer kayaks, canoes, pedal boats, sail boats, wind surfers, snorkel-set glass-bottomed boats, and other facilities to tourists who wish to indulge in water sports in the unpolluted lagoons. Kadmat, Kavaratti, and Bangaram have facilities for scuba diving. Deep-sea fishing buffs can pursue big-game fishing. Barracuda, sailfish, yellow fin tuna, triveli, and sharks are abundant in the seas around Lakshadweep. Local boats with experienced crews can be hired (Society for Promotion of Nature Tourism and Sports, Lakshadweep Tourism, n.d.).

Issues and constraints of Lakshadweep

The islands of Lakshadweep offer potential for tourism development; however, prior efforts have not been successful due to restrictions. The following is a summary of the significant concerns currently impacting the islands, as well as the accompanying potential and restrictions. (Lakshadweep Tourism Policy-2020 is published herewith for comments and suggestions, n.d.)

The most critical problem limiting Lakshadweep’s tourism potential is connectivity. The provision of secure, dependable, and speedier mainland-island and inter-island communication is critical to the growth of tourism in Lakshadweep. Tourists can arrive in Lakshadweep by ship or flight; therefore, the lack of transportation renders occupancy on the islands quite low. Tourism activities in Lakshadweep are primarily seasonal due to a lack of all-weather transportation facilities. Even though the months of June and September are suitable for adventurous water sports such as wind and wave surfing, the complete lack of tourist transportation facilities during the monsoon season limits the exploration of Lakshadweep’s tourism potential. This halts tourism activity in Lakshadweep.

However, due to the short length of the air strip at Agatti airport, only tiny ATR aircraft may land, and only with reduced cargo. Alliance Air (Air India) is now operating in the Agatti-Kochi sector with a small aircraft capable of carrying seventy-two passengers. Tourists must compete with local passengers and those visiting Lakshadweep for official causes.

Next to transportation, the availability of accommodation on the islands limits visitor arrivals. According to the authorized carrying capacity research, Lakshadweep’s populated islands have a tourist capacity of 918 keys (rooms) on nine islands, while the four uninhabited islands, Bangaram, Thinnakara, Cheriyam, and SuheliCheriyakara, have 431 keys. With an annual average tourist occupancy rate of 45.5% in Lakshadweep, an estimated number of visitors might be accommodated on these islands. However, Lakshadweep now has just 184 beds on the islands.

Lakshadweep is barely linked to the rest of the internet because of its relatively low satellite bandwidth of 1.3 Gbps, which is split further to distribute among the several islands and also for the SWAN communication system for administrative reasons. This is due to the lack of optical fiber cable connectivity. Kavaratti, the administrative capital, has 4G communications access. Apart from Kavaratti, Agatti and Minicoy are now connected to a 4G network. However, a bad networking system on many islands stifles the expansion of IT-enabled tourist businesses and causes guest unhappiness.

The Lakshadweep archipelago currently has no international representation due to a lack of public outreach and marketing through different print and visual mediums. The island’s websites do not convey an exciting and adventurous picture, and they significantly lack direction and guidance for potential tourists. The beauty and fascination of these islands are only dimly recognized due to a dearth of brochures, maps, and marketing targeted at attracting potential tourists. Lakshadweep might benefit significantly from an effective branding and marketing plan.

All tourist enterprises in the Lakshadweep Islands require well-trained and competent workers to support the tourism and resort operations. The future installation and operation would also require trained workers, which the islands will be unable to provide owing to a lack of training or skill development institutes. To address this issue, numerous skill development programs and institutes might be built on the many islands of Lakshadweep, giving inhabitants the chance and empowerment to participate in the island’s burgeoning economy.

The coral island ecology is extremely fragile and vulnerable to even minor environmental changes. Any activity that interferes with coral activity endangers the foundation of the island’s eco-system. The increased presence of visitors will generate additional garbage, which must be disposed of in an environmentally appropriate manner. The availability of safe drinking water is the next important concern. Presently, desalination plants are only accessible on three islands: Kavaratti, Agatti, and Minicoy. Kalpeni was slated to be finished in 2020. The absence of desalination plants on neighboring islands would limit the supply of safe drinking water for tourists.

Diesel generators provide 90% of all electricity. The provision of an uninterrupted power supply would be critical for the promotion of tourism in the Lakshadweep Islands. The cost of power generation is quite expensive. Furthermore, electricity generation using DG sets will have its own impact on the coral island environment. Even if the inhabitants of Lakshadweep are not opposed to tourism, the local customs and culture will necessitate responsible tourism that respects the local population’s socio-cultural traditions. There is now a total restriction in Lakshadweep, except for the Bangaram Islands.

What needs to be changed?

The Lakshadweep administration intends to completely restructure its tourist industry, as stated in their tourism policy for 2020. The government’s tourism program includes an action plan that includes numerous interventions. The Lakshadweep Administration’s action plan aims to encourage local inhabitants to develop and operate tourist homes on islands within their allowed carrying capacity, aligning with the policy’s overarching vision and objectives.

To meet the demands of high-end guests, resort infrastructure will be built on inhabited islands whenever practicable, ensuring that the benefits of tourism growth reach the whole Lakshadweep people and that all islands of Lakshadweep develop in a balanced manner. The Lakshadweep Administration will promote and facilitate the construction of eco-friendly tourist resorts in each inhabited island through public investment, private investment, or public-private partnership, with a minimum bedding capacity that is compatible with the islands’ carrying capacity, as well as within the counters of approved IIMPs.

Uninhabited islands in Lakshadweep are ideal for international tourism focused on the sun, sea, coral, lagoon, and beach since they do not disrupt the rigid social conventions and traditions of the insular inhabitants. However, these islands lack underlying infrastructure and connecting services, and the majority of the land is privately held by the residents. The Lakshadweep Administration will support the holistic development of ecotourism initiatives on the uninhabited islands, particularly Bangaram, Thinnakara, Suheli, and Cheriyam, through public investment, private investment, and public-private partnerships. To capitalize on tourism’s growing potential as an economic and social development sector in the islands, the Lakshadweep Administration and NITI Aayog have jointly proposed three anchor projects for the public-private partnership (PPP)-based development of island water villa resorts, including beach and water villas, on the islands of Minicoy, Suheli Cheriyakara, and Kadmat. The number of ‘Resorts’ and private ‘Tourist Homes’ licensed by the Administration should be regulated to ensure that the overall tourist capacity at any given time does not exceed the separate islands’ approved tourist carrying capacity. The ‘first come, first served’ concept and a suitable standard size for each unit (key) of the resort or private tourist house shall be considered when granting authorization to the planned promoters. The most critical problem limiting Lakshadweep’s tourist potential is connectivity. The provision of secure, dependable, and speedier mainland-island and inter-island communication is critical to the growth of tourism in Lakshadweep. The Lakshadweep Administration suggests a multifaceted plan to address the connection issue in terms of, but not limited to:

To improve institutional monitoring, Lakshadweep Tourism will establish an interactive website with complete information for both domestic and foreign tourists. A robust campaign will be conducted on social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and blogging sites to attract the younger, emerging generation of tourists.

The Department of Tourism will develop a contemporary and well-equipped tourism facilitation center at Agatti, which is regarded as the entrance for travelers to Lakshadweep. This center will run a centralized tourist hotline 24 hours a day, seven days a week, providing information about tourist attractions, tour packages, each visitor’s travel manifest, and safety and security measures implemented at the locations. To execute and fulfil the objectives of this policy, and bearing in mind that several agencies are engaged in the delivery of the tourist product, an Empowered Committee for Coordinated Decision Making will be formed, chaired by the Administrator of the Union Territory of Lakshadweep. The Lakshadweep Administration will decide on the details of the committee’s formation and functioning on a regular basis.

Lakshadweep Tourism Development Corporation Ltd. (LTDC)

The Society for Promotion of Nature, Tourism, and Sports (SPORTS), founded in 1982 under the Societies Registration Act of 1860, now serves as a key body for promoting tourism in Lakshadweep. Sports activities have grown significantly during the past 30 years. The pace and type of tourist growth in Lakshadweep have likewise altered over time. And the current scenario necessitates increased professionalism, openness, and accountability in the system.

Lakshadweep Administration has taken proactive steps to transform SPORTS into Lakshadweep Tourism Development Corporation Ltd. (LTDC), a wholly owned subsidiary of the Lakshadweep administration registered under the Companies Act, for better management, effective control, and compliance with various legal requirements. LTDC, which is in charge of developing and promoting Lakshadweep tourism both domestically and internationally, was established on October 11, 2018, under the Companies Act of 2013 (18 of 2013).

Facilitating an Easy Entry Permit System

All visitors who intend to visit Lakshadweep and stay in registered private tourist houses, resorts, or other tourism-related establishments will be able to book through a web-based central system. LTDC/SPORTS will be responsible for operating this system. These visitors or guests will likewise be presumed to be sponsored by the SPORTS/LTDC to avoid issues with permission issuance and delays that would upset both tourists and private tourist residences or resort operators.

Conclusion

A study of Lakshadweep tourism policy reveals that the archipelago is aware of its strengths and weaknesses and has a comprehensive strategy in place to rebuild its whole tourist ecology. The advantage Lakshadweep has over Maya Bay is that tourism has always been regulated on the islands, giving it ample time to strategize how tourist growth should go so that the islands do not follow Maya Bay's trajectory.

Funding

This work was not supported by any funding agency.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Bangkok Post. (2018, Oct 9). 'Beach' balm: Maya Bay's ecosystem recovering, says dept.© Bangkok Post PCL. All rights reserved. Retrieved January 24, 2024, from https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1554314/beach-balm-maya-bays-ecosystem-recoveringsays-dept .

- BBC News. (2019, February 21). Maya Bay: The beach nobody can touch—BBC News [video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-dZ-g_OAIgLink.

- Cripps,K. (2022, August 1). Tourism Killed Thailand’s Most Famous Bay. Here’s How It Was Brought Back to Life. Retrieved January 24, 2024, from https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/maya-bay-thailand-recovery-c2e-spc-intl/.

- Crotts, J. C., & Holland, S. M. (1993). Objective indicators of the impact of rural tourism development in the state of Florida. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1(2), 112-120. [CrossRef]

- Entry Permit Rules: Lakshadweep. https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s358238e9ae2dd305d79c2ebc8c1883422/uploads/2018/05/2018050467.pdf.

- Epler Wood, M., Milstein, M., & Ahamed-Broadhurst, K. (2019). Destinations at risk: the invisible burden of tourism. The Travel Foundation.

- Farrell, B. H., & Runyan, D. (1991). Ecology and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 18(1), 26–40. [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. (2001). The consequences of tourism for sustainable water use on a tropical island: Zanzibar, Tanzania. Journal of Environmental Management, 61(2), 179–191. [CrossRef]

- Israngkura, A. (2022, March). Marine resource recovery in Southern Thailand during COVID-19 and policy recommendations. Marine Policy, 137, 104972. [CrossRef]

- Koh, E., & Fakfare, P. (2020). Overcoming "over-tourism": The closure of Maya Bay. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6(2), 279–296,.

- Lakshadweep | Official Website of Administration of Lakshadweep | India. https://lakshadweep.gov.in/.

- Lakshadweep Tourism Policy 2020 is published herewith for your comments and suggestions. https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s358238e9ae2dd305d79c2ebc8c1883422/uploads/2020/05/2020052611.pdf.

- Liu, J. C., & Var, T. (1986). Resident attitudes towards tourism impacts in Hawaii. Annals of Tourism Research, 13(2), 193-214. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M. L., & Auyong, J. (1991). Coastal zone tourism is a potent force affecting the environment and society. Marine Policy, 15(2), 75–99. [CrossRef]

- Northcorp, E. (2020). OPPORTUNITIES FOR TRANSFORMING COASTAL AND MARINE TOURISM Towards Sustainability, Regeneration and Resilience. The High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Ocean Panel). https://oceanpanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Sustainable-Tourism-Full-Report.pdf.

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2010). Small island urban tourism: a residents' perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(1), 37–60. [CrossRef]

- Pacific Asia Travel Association. (2022). Asia Pacific Visitor Forecasts 2022–2024 Bangkok: PATA.

- Papageorgiou, M. (2016, September). Coastal and marine tourism: A challenging factor in Marine Spatial Planning. Ocean & Coastal Management, 129, 44–48. [CrossRef]

- Phi Phi Islands. Thai National Parks. https://www.thainationalparks.com/hat-noppharat-thara-muko-phi-phi-national-park.

- Smith, P. (2022, May 16). Thailand Cove, made famous in The Beach, reopens to visitors after a four-year closure. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2022/may/16/thailand-cove-made famous-in-the-beach-reopens-to-visitors-after-four-year-closure.

- Society for Promotion of Nature Tourism and Sports—Lakshadweep Tourism. https://lakshadweeptourism.com/watersports.html.

- Sun, R. H., & Gao, J. (2012, October). An Overview of the Environmental Impacts of Coastal Tourism. Advanced Materials Research, 573–574, 362–365. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, F. (2018). The beach goes full circle in the case of Koh Phi Phi, Thailand. Film tourism in Asia: Evolution, transformation, and trajectory, 87–106.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).