Introduction

The study of onychophorans, often called “peripatus” or velvet worms, offers a fascinating field from biology to folklore. Originating over 500 million years ago, during the Cambrian period, they are important in the fields of evolution, physiology, behavior and, more recently, biologically-based adhesives (Cerullo et al., 2020; Monge-Nájera, 2020).

Historically, scientists and naturalists have been captivated by onychophorans. Early researchers, armed with basic tools and keen observation, moved from basic classification to ecology, and recent work incorporates modern methods like molecular biology and imaging techniques (Monge-Nájera, 2020).

Onychophorans, with their long history, offer more than just a lesson in biology; they provide a window into our planet's past and its evolutionary processes. Firstly, from an evolutionary perspective, Onychophorans serve as living relics that provide insights into the ancient conditions of life on Earth. Secondly, their physiological and behavioral adaptations distinguish them from other invertebrate taxa. Their velvety appearance is the result of a flexible skin with papillae and sensory bristles that allow them to feel their way in the subterranean ecosystems they occupy the world over (Monge-Nájera, 2020).

Unlike many invertebrates, some species are viviparous and have placentas (Monge-Nájera, 2020). Additionally, their production of an adhesive that holds the prey attached to the substratum, have made them popular in the media (Monge-Nájera and Morera-Brenes, 2015).

The bicentennial of the inaugural publication about Onychophora is an opportune moment to remember the researchers, men and women, who have significantly advanced our understanding of these remarkable organisms, survivors of all known mass extinction events (Monge-Nájera, 2020).

Here I will briefly present a select group of researchers, representative of the thousands who have enriched this field in these two centuries, with a focus on their scientific accomplishments and lives, starting with Lansdown Guilding (1797-1831), the first onychophorologist.

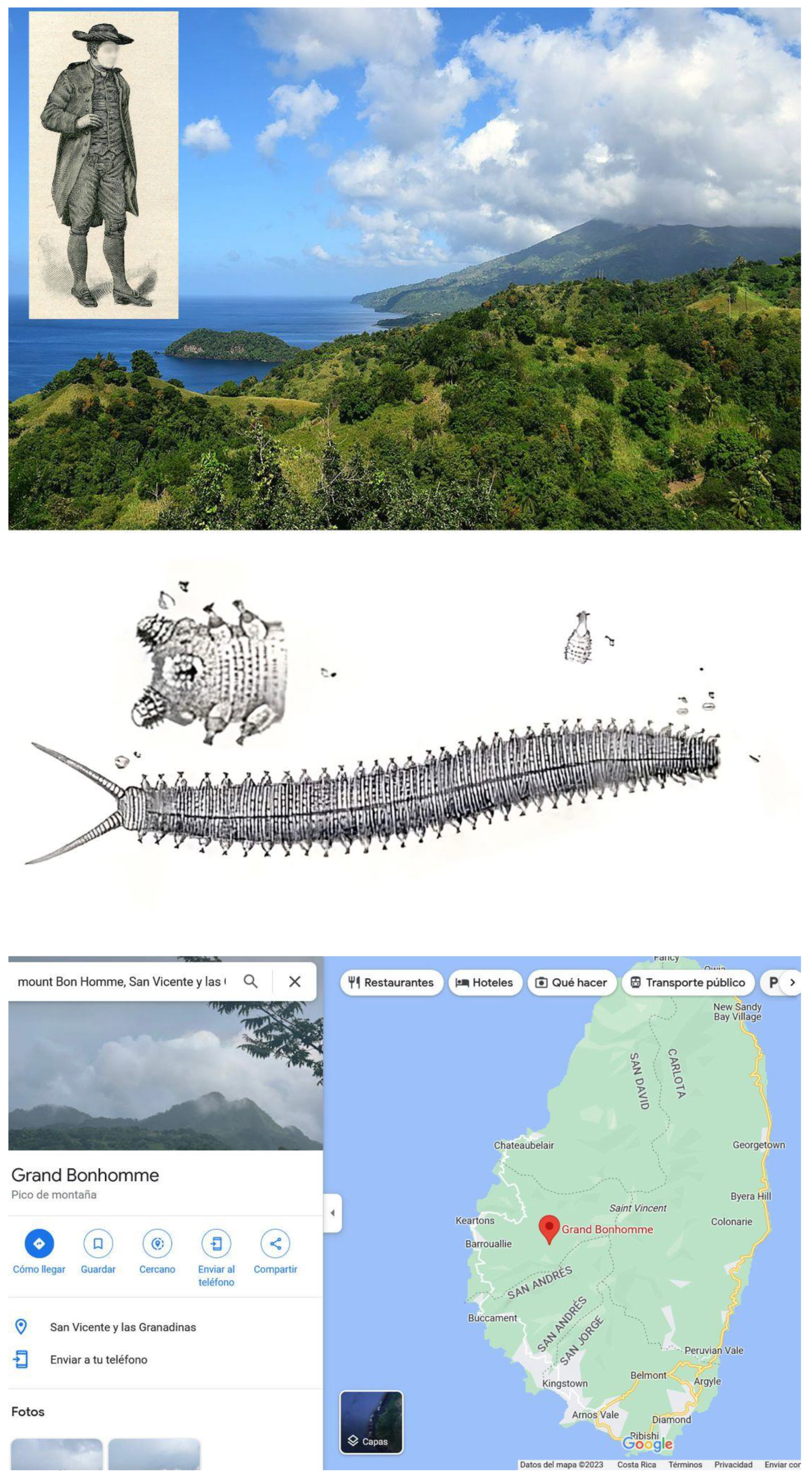

Lansdown Guilding (1797-1831)

The first onychophorologist was a talented naturalist and artist from the tiny Caribbean island of Saint Vincent, Lansdown Guilding

(Figure 1). He was sent to England at age five to start his formal education. He proved brilliant and graduated from Oxford University while still young; and became a Fellow of the Linnean Society in 1818, aged 20. He corresponded with Joseph Hooker and Charles Darwin, providing them with notes on the natural history of the Caribbean. Guilding was a skilled artist, particularly in plant and animal drawings, and was critical of inaccuracies in the printer’s reproductions of his own work. He published

An Account of the Botanic Gardens of the Island of St. Vincent in 1825 and developed a

Table of Colours Arranged for Naturalists.

In 1821, he married Mary Hunt, but she died in 1827 while giving birth to their fifth child. Guilding remarried to Charlotte Melville in 1828 and had two more children with her. He discovered the first onychophoran, which he named Peripatus; in the formal description, he wrote “it inhabits primary forests in Saint Vincent, often walks backward. If pressed, it releases viscous liquid from the mouth. Among the plants that I collected at the foot of mount Bon Homme, I, astonished, discovered by chance the only specimen” (Monge-Nájera, 2019). Guilding died on vacation in Bermuda aged 34, the cause was not recorded (Howard & Howard, 1985).

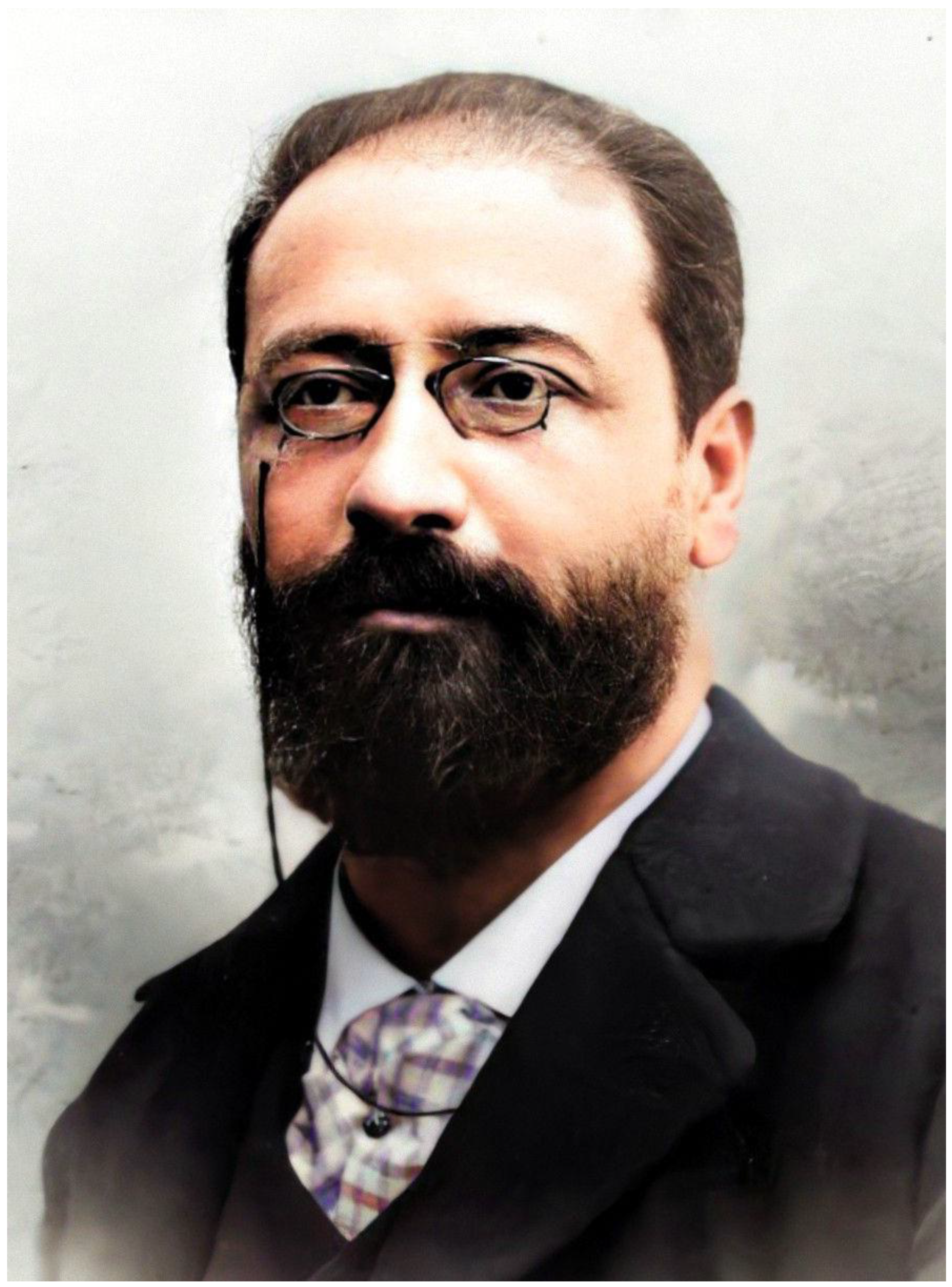

Jean Victor Audouin (1797–1841)

Jean Victoire Audouin

(Figure 2) was a versatile French naturalist who contributed in entomology, herpetology, ornithology, and malacology. Born on April 27, 1797, in Paris, he initially pursued a career in medicine. In 1824, he was appointed as an assistant to Pierre André Latreille, the then-professor of entomology at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, eventually succeeding him in 1833. Audouin played a pivotal role in co-founding both the

Annales des Sciences Naturelles and the

Société Entomologique de France.

He ascended to the position of a professor of entomology and gained membership in the esteemed Academy of Sciences.

In 1827, Audouin married painter Mathilde-Émilie Brongniart (

Figure 2), and together they raised three children. Tragically, Audouin's life was cut short at the age of 44 due to a brief illness. Nevertheless, his legacy endures through his significant contributions to the field of entomology, exemplified by his principal work,

Insects that affect the grapevine and how to combat them (1842). Audouin was an early proponent of the idea that onychophorans were not mollusks, although he mistakenly classified them as annelids (Theodorides, 1970).

Charles Émile Blanchard (1819 –1900)

Born in Paris, Blanchard (Figure 3) was a French zoologist, son of an artist and naturalist. At 14, he was accepted by Jean Victoire Audouin as a laboratory assistant at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle.

Blanchard's career at the Museum spanned from being a technician to an assistant-naturalist. His works included Natural History of Insects (1845) and Agricultural Zoology (1854-1856). He failed to support Darwinism and opposed Darwin’s election to the French Academy of Sciences in 1870. He left his position aged 74 due to infirmity and eye problems, and became fully blind in 1890. He wrote the detailed onychophoran chapter for the book series Historia Física y Política de Chile edited by Claude Gay in Santiago de Chile. He died of old age in Paris in 1900 (Glick, 1988).

Lorenzo Camerano (1856-1917)

Lorenzo Camerano

(Figure 4) was an Italian zoologist and alpinist born in Biella. He initially studied painting, before shifting to natural history and eventually becoming a professor in 1880. Born into a family that frequently relocated due to his father's government job, Camerano's early education took place in Bologna. Later, in 1874, he graduated from the Liceo Classico Vincenzo Gioberti in Turin. He successfully completed his studies in mathematics, physics, and natural sciences at the University of Turin in 1878. Subsequently, he joined the University's zoological museum as an assistant, under the leadership of Professor Lessona. Camerano later married Lessona's daughter, a schoolteacher.

In 1889, Camerano briefly assumed the role of chairman of the comparative anatomy and physiology department at the University of Cagliari, a position he held for only two months before accepting Lessona's chair at the more prestigious University of Turin. In 1894, he became the director of the Zoological Museum of the University of Turin, serving as rector from 1907 to 1910. In 1909, he was appointed a senator of the Kingdom of Italy. He published five extensive monographs on the reptiles and amphibians of Italy from 1883 to 1891, which he illustrated himself. He was a strong proponent of Darwin’s ideas, with a significant scientific output of more than 300 titles (Baccetti, 1974), including several papers on South American onychophorans.

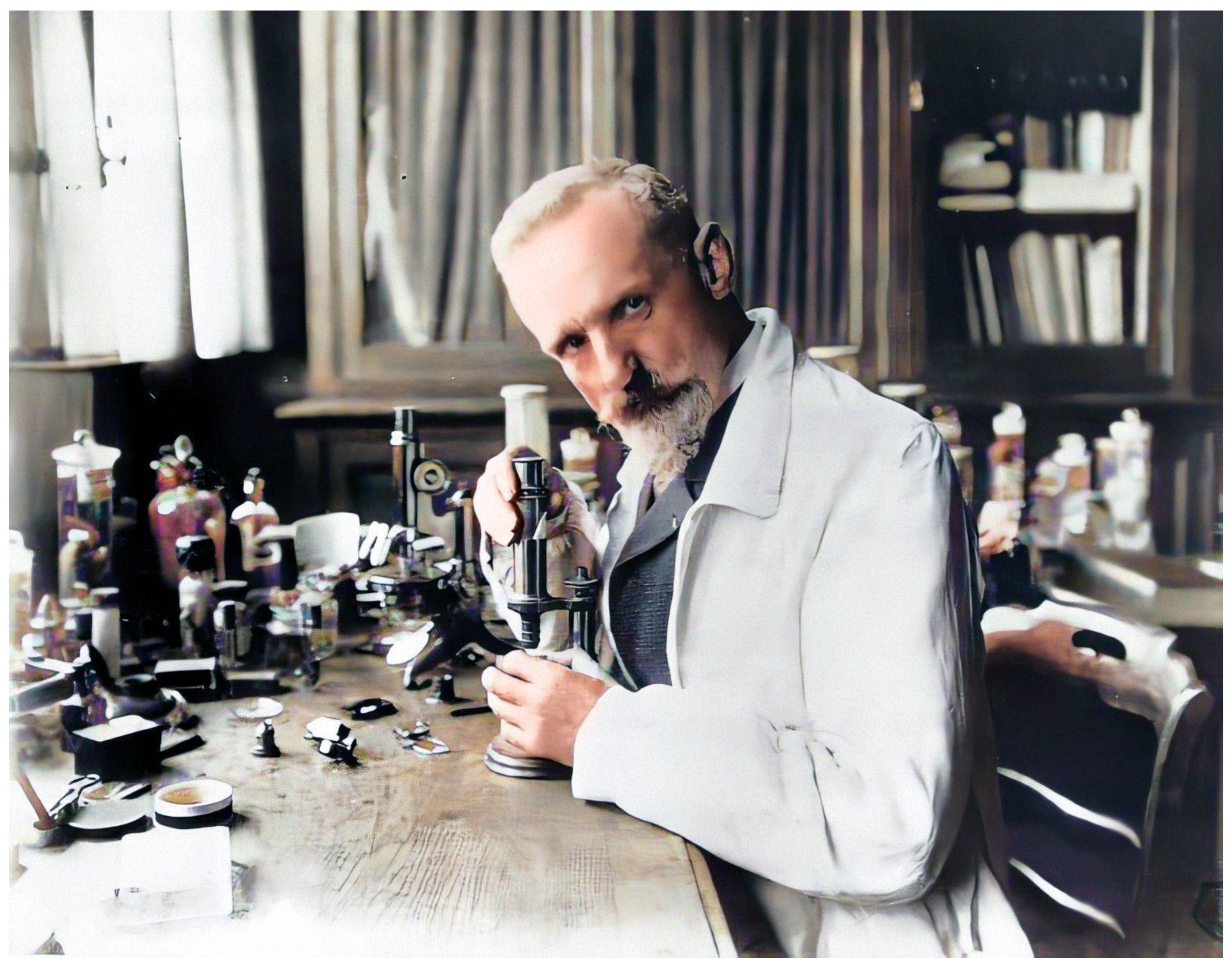

Eugène Louis Bouvier (1856-1944)

E. L. Bouvier

(Figure 5) initiated his journey into natural sciences by collecting plants, guided by his high school teacher, and eventually became a teacher himself. In his words, 'my father, a peasant watchmaker, owned a farm. I loved going into the surrounding woods to observe the silent animals, I observed and brought insects back to my teacher; insects, especially ants, fascinated me. I was a good student and finished first in a competition that existed at the time between primary schools in my region.'

He later assumed the Museum’s Chair of Zoology. His work on gastropods led him to evolutionary interpretations of organisms. He became the founding father of onychophorology and authored the only monograph of the entire phylum to date. At the museum, Bouvier established a 'citizen science' program to expand the collections. Pressed by his adversaries to work with insects rather than onychophorans, he published several entomological books for the general public, thereby fulfilling this requirement (Fage, 1944).

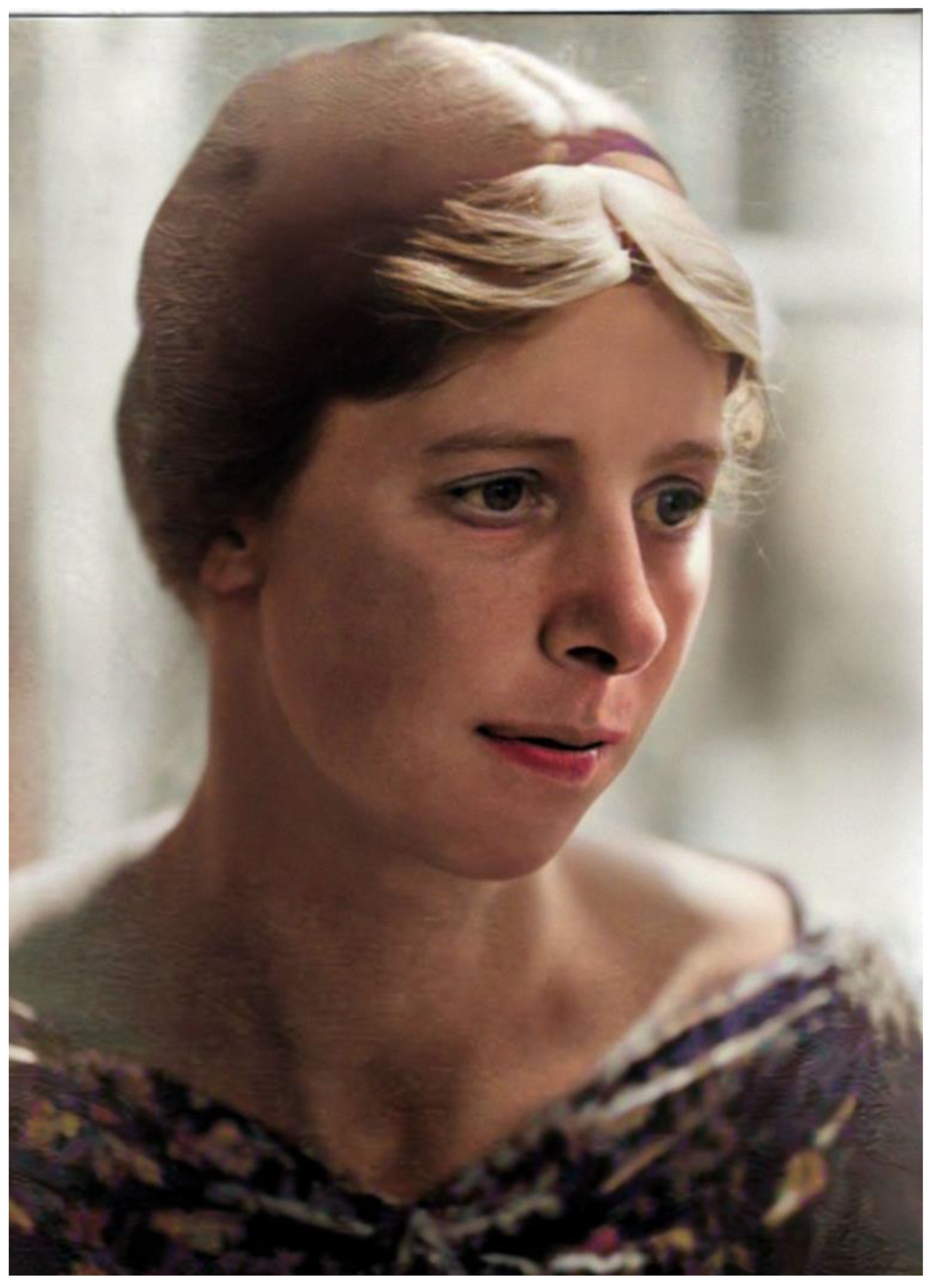

Sidnie Milana Manton (1902–1979)

Manton

(Figure 6), born in London to parents of French aristocratic ancestry, was educated at Girton College, Cambridge. She became the first woman to receive a Doctor of Science degree from Cambridge University, in 1934. As a child, she was fond of collecting and drawing plants and insects. She later served as the Director of Natural Sciences at Cambridge and married zoologist John Philip Harding, with whom she had a daughter and adopted a son. Her sister, botanist Irene Manton, was also a prominent figure in academia.

From 1928 to 1929, Manton participated in a pivotal expedition to the Great Barrier Reef of Australia, significantly contributing to the understanding of the reef's ecology and health through her collection and preservation of arthropod specimens that other researchers in the group could not reach (she was an outstanding swimmer). She also served as Director of Studies in Natural Sciences and Geography, as well as a Lecturer at Cambridge University. Her notable publication, The Arthropoda: Habits, Functional Morphology, and Evolution, was released in 1977.

She was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1948 and served as a reader in zoology at King's College, London, from 1949 to 1960, while also being associated with the British Museum's Natural History section (Blower, 1979).

Manton's research significantly advanced the understanding of invertebrates, particularly onychophorans. However, she may have had mixed species in her terraria, which could affect the specificity of her data on South African onychophorans (this cautionary note is included as a warning for future researchers, although I cannot recall the exact source of this information).

Sylvia S. Campiglia

Sylvia Campiglia

(Figure 7), a Brazilian scientist, has significantly contributed to the study of the Onychophora, focusing on the Brazilian species

Peripatus acacioi. Her research encompasses various aspects of this species, including developmental biology, reproductive physiology, and neurocytology.

Campiglia's investigations into the embryonic development and reproductive mechanisms of Peripatus acacioi have yielded valuable insights into their life cycles and reproductive strategies. Her pioneering studies on physiological adaptations, such as water retention and hemolymph composition, alongside meticulous research in morphometry and physiology, particularly regarding the tracheal system and nephridial function, are noteworthy (Campiglia, 1987). As of 2023, I understand she is alive but retired.

Roger Lavallard

Lavallard

(Figure 8), worked at the University of Sao Paulo's Physiology Department, and affiliated with the University of Paris VI's Laboratory of Insect Physiology. He collaborated extensively with Sylvia Campiglia on

Peripatus acacioi research. Their studies encompass a comprehensive analysis of the animal’s habitat near Ouro Preto in Brazil, detailing environmental conditions and adaptations to its specific ecological niche.

Together with Campiglia, Lavallard provided insights into factors like humidity, temperature, and soil characteristics, emphasizing the worm's adaptation to seasonal changes. Investigations into sex distribution and morphological variations in Peripatus acacioi revealed a slight female dominance and variations in the number of lobopods between sexes (females are longer and thus, have more legs). Their research also delved into the physiological responses of Peripatus acacioi, particularly regarding water loss under experimental immobilization (Campiglia & Lavallard, 1990), enhancing understanding of dehydration adaptations (dehydration, a key problem for onychophorans, has limited their behavior and distribution).

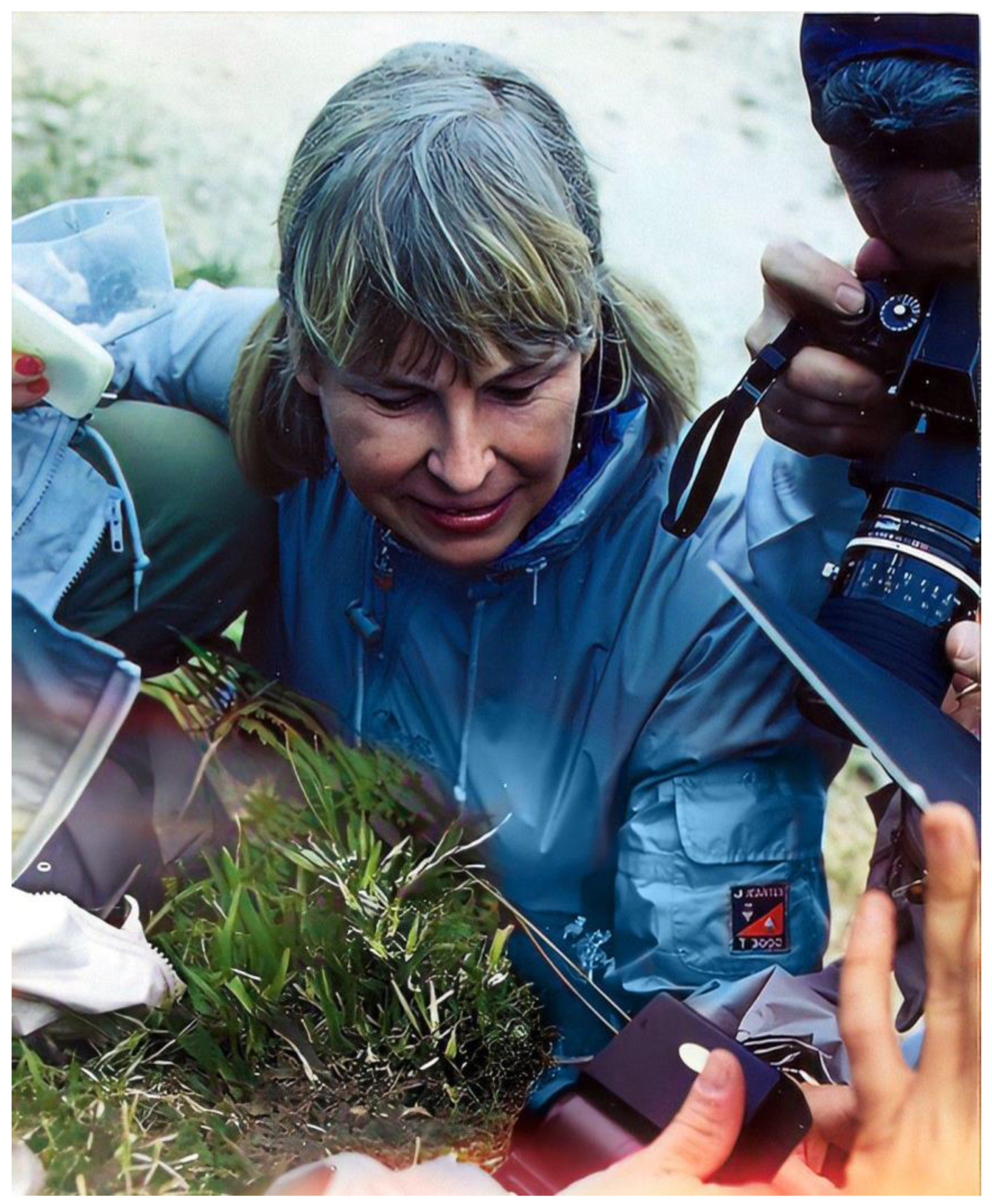

Hilke Ruhberg (1940- )

Hilke Ruhberg

(Figure 9) was born in Osnabrück, Germany, during the Second World War. As a young girl, she helped a relative in a shop where small metal pieces were manipulated, a task that honed her manual skills, later essential for the dissection of onychophorans (Ruhberg, personal communication).

She held academic positions at the University of Hamburg from 1996 to 2005, eventually being promoted to a full professorship in Zoology. Hilke married a jet pilot and had two sons. Her work primarily focused on the ultrastructure, developmental biology, and reproductive systems of onychophorans, notably on the fusion of coelomic cavities during development. One of her most significant contributions is the comprehensive revision of the Peripatopsidae family, encapsulating the taxonomic knowledge of this group at the time. She has continued her scholarly contributions post-retirement in 2005 (de Sena Oliveira, et al., 2018).

Bernal Morera Brenes (1962- )

Bernal Morera

(Figure 10) was born in a small coffee plantation town in Costa Rica. Exhibiting an exceptional aptitude for science and a deep curiosity about the natural world from an early age, he studied at the University of Costa Rica, the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, and Pompeu Fabra University in Spain, becoming a respected expert in human genetics, gene admixture within the Costa Rican population, and the evolution of human populations in Latin America.

For decades, he has devoted his studies to the Onychophora of Central America, publishing in several fields. In 2010, he described a giant onychophoran from the Caribbean rainforest of Costa Rica, the largest known to date. His research includes studies on character diversity, biomechanics of the velvet worm slime jet, and the cultural references and public perception of velvet worms in folklore and art. His later work has centered on taxonomy and systematics; the relationship between environmental factors and activity; geographic distribution; and risk assessment of their conservation status. In 2001, he was honored as the 'Scientific Figure of the Year' by the Costa Rican newspaper La Nación. Currently, at the Laboratory of Systematics, Genetics, and Evolution of Universidad Nacional, he is educating the next generation of Costa Rican onychophorologists (Barquero-González, et al., 2020).

Other names that appear with frequency in the literature are Noel Tait and Robert Mesibov from Australia; Georg Mayer from Germany; Cristiano Sampaio Costa and Ivo de Sena Oliveira from Brazil; and José Pablo Barquero-González from Costa Rica. These new researchers will lead the future advances in the field of onychophorology.

Acknowledgments

I thank Cristiano Sampaio for the information and photographs of S. Campiglia and R. Lavallard, and the participants of the 19th International Congress of Myriapodology (and Second of Onychophorology), particularly Daniela Martínez Torres, for their support and comments.

References

- Anonymous. (1880). Adolph Edouard Grube. Nature, 22(567), 435–436. [CrossRef]

- Baccetti, B. (1974). Camerano, Lorenzo. In A. M. Ghisalberti (Ed.), Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI) (Vol. 17, pp. Calvart–Canefri). Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana.

- Barquero-González, J. P., Sánchez-Vargas, S., & Morera-Brenes, B. (2020). A new giant velvet worm from Costa Rica suggests absence of the genus Peripatus (Onychophora: Peripatidae) in Central America. Revista de Biología Tropical, 68(1), 300-320.

- Blower, J. G. (1979). Obituary: Sidnie Manton. Nature, 278(5703), 490–491.

- Campiglia, S. S. (1987). The lack of a structured blood-brain barrier in the onychophoran Peripatus acacioi. Journal of Neurocytology, 16, 93-104. [CrossRef]

- Campiglia, S., & Lavallard, R. (1990). On the ecdysis at birth and intermoult period of gravid and young Peripatus acacioi (Onychophora, Peripatidae). In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress of Myriapodology (p. 461). E.J. Brill.

- Cerullo, A.R.; Lai, T.Y.; Allam, B.; Baer, A.; Barnes, W.J.P.; Barrientos, Z.; Deheyn, D.D.; Fudge, D.S.; Gould, J.; Harrington, M.J.; Holford, M.; Hung, C.-S.; Jain, G.; Mayer, G.; Medina, M.; Monge-Nájera, J.; Napolitano, T.; Pales Espinosa, E.; Schmidt, S.; Thompson, E.M.; Braunschweig, A.B. (2020). Comparative animal mucomics: Inspiration for functional materials from ubiquitous and understudied biopolymers. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, 6(10), 5377-5398.

- de Sena Oliveira, I., Ruhberg, H., Rowell, D. M., & Mayer, G. (2018). Revision of Tasmanian viviparous velvet worms (Onychophora: Peripatopsidae) with descriptions of two new species. Invertebrate Systematics, 32(4), 909-932.

- Fage, L. (1944). Eugène-Louis Bouvier 1856–1944. Annales des Sciences Naturelles, Serie 11: Zoologie et Biologie Animale, 6(1), 1-24.

- Glick, T. F. (1988). The Comparative Reception of Darwinism. University of Chicago Press. p. 148. ISBN 0-226-29977-5.

- Howard, R. A., & Howard, E. S. (1985). The Reverend Lansdown Guilding, 1797-1831. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum, 37(4), 401–402.

- Monge-Nájera, J. (2019). "I, astonished, discovered by chance the only specimen”: the first velvet worm (Onychophora). Revista de Biología Tropical: https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/rbt/article/view/39056/39793.

- Monge-Nájera, J. (2020). Onychophorology, the study of velvet worms, historical trends, landmarks, and researchers from 1826 to 2020 (a literature review). Revista UNICIENCIA, 35(1):. [CrossRef]

- Monge-Nájera, J., & Morera-Brenes, B. (2015). Velvet worms (Onychophora) in folklore and art: geographic pattern, types of cultural reference and public perception. British Journal of Education, Society & Behavioural Science 10(3): 1-9: https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1605/1605.06706.pdf.

- Theodorides, J. (1970). Audouin, Jean Victor. In Dictionary of Scientific Biography (Vol. 1, pp. 328–329). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-10114-9.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).