1. Introduction

Stochastic simulations require large amounts of time to generate enough trajectories to attain statistical significance and estimate desired performance indices with satisfactory accuracy [

1,

2,

3]. Complex problems such as climate change mitigation, network design, and command and control decision support require search spaces with deep uncertainty arising from inadequate or incomplete information about the system and the outcomes of interest [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Furthermore, simulation models for system engineering analyses presents challenges to today’s computational technologies. First, questions addressed at the Systems of Systems (SoS) level, require large detailed models to provide sufficient representation of relevant system to system interactions of stochastic nature. Second, they also require multiple executions with multiple random seed state initiations to cover the wide range of configurations necessary to obtain statistically significant measurement of performance outcome distributions.

Surrogate models, i.e., simplified models which drastically reduce computation while providing useful guidance, have successfully helped find global optima of computationally expensive optimization problems for real world applications [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The methods using such models are often referred to as multi-fidelity/multilevel/variable-fidelity optimization. We note that the term fidelity is often employed to refer to ambiguous combinations of resolution and accuracy. We note that the term fidelity is often employed to refer to ambiguous combinations of resolution and accuracy [

17,

18]. A generic framework was defined [

19] in which models of different accuracy and computation costs are selected algorithmically to reduce the overall computational cost while preserving the accuracy of the simulation analysis. While such frameworks exist, they do not by themselves provide the surrogate models or more generally methods for speeding up simulation of stochastic systems to support more timely systems analysis and optimization [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Parallel execution of simulations offers another avenue for speedup of complex simulations. Unfortunately, to exploit parallelization of simulation models for generic system engineering analyses presents challenges to today’s computational technologies [

26,

27]. Although technological advances at the hardware level will enable more and faster processors to handle such simulations, with cloud services adding access to additional resources, such computational support is destined to reach its limit. Therefore, the imperative remains to formulate parallelization in more model-centric ways. Paratemporal and cloning simulation techniques have been introduced that increase opportunities for parallelism [

28,

29] and with abstractions that recognize the effect of random draws on system evolution as constituting choice points with opportunities for reuse [

30]. However,

scalability, the ability to overcome the combinatorial explosion of branching arising from multiple choice points presents a major hurdle that must be overcome to implement such techniques.

Nutaro et al [

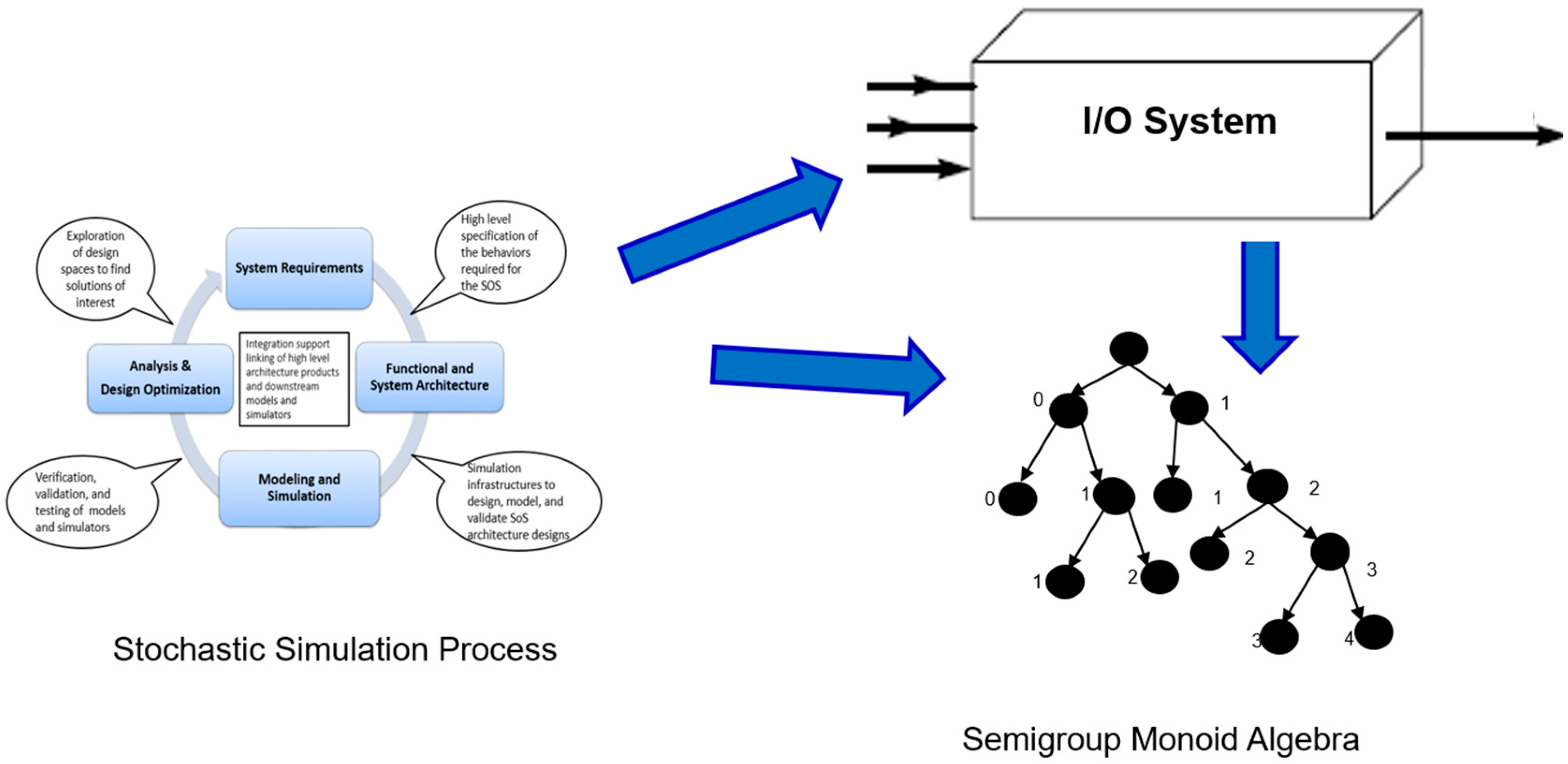

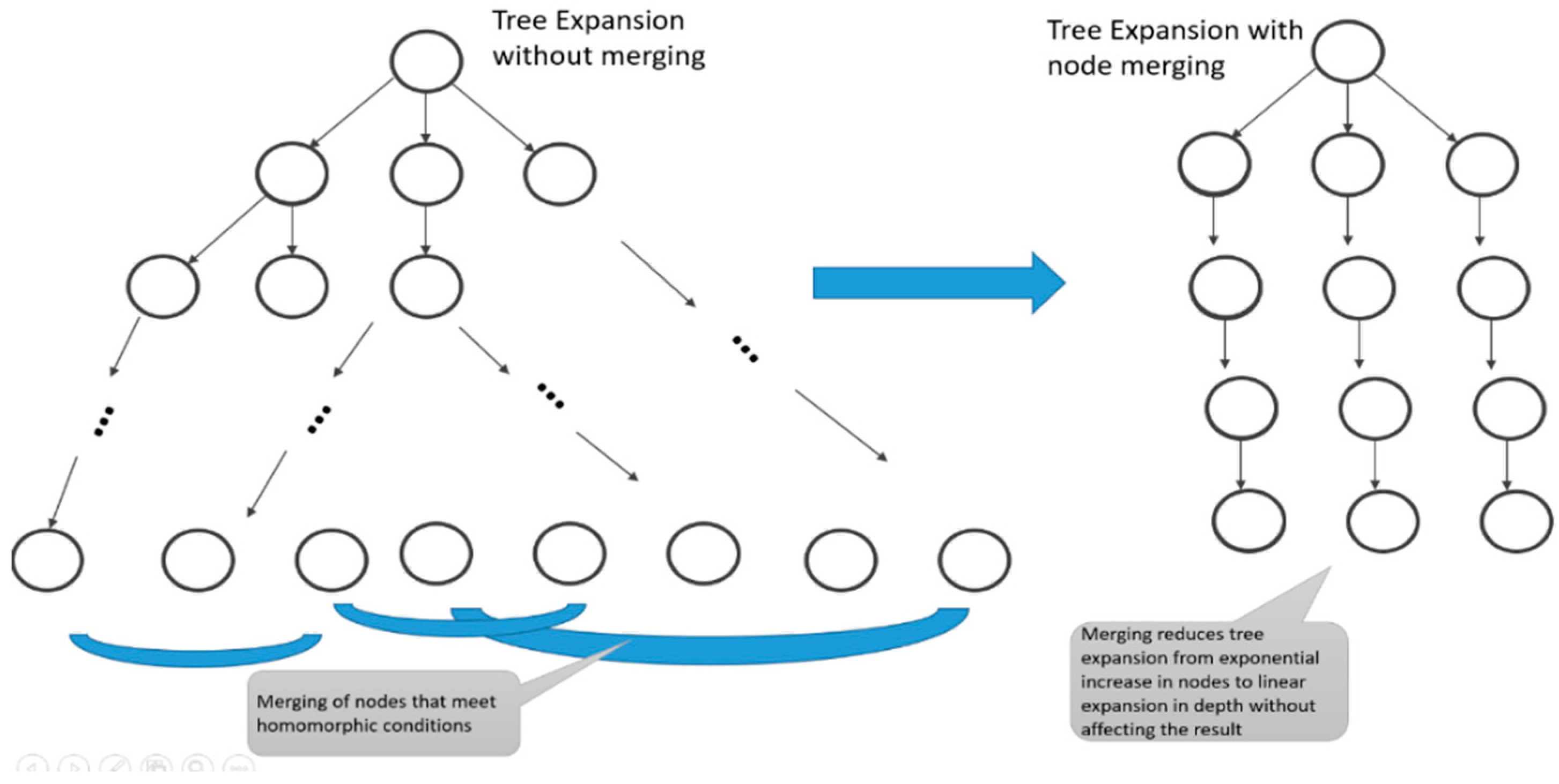

31] examined the use of tree expansion methods in lieu of the conventional sampling of outcomes when working with the uncertainty inherent in stochastic simulations. Conventional techniques simulate a large number of randomly sampled trajectories from start to finish in one at a time fashion. As illustrated on the left side of

Figure 1, such trajectories can be viewed as paths from an initial state of the stochastic system (the root of the tree) to one of the terminal states, leaves of the tree, in a manner consistent with random sampling. The advantage of tree construction is that states of the model that have been reached at any point – nodes of the tree - can be cloned for reuse, thus avoiding duplication. Branches in the tree from a state correspond to draws of the random variable whose values determine the subsequent course of the model from that state.

In particular, tree expansion with breadth first traversal can significantly speed up the computation required to generate the same sampling outcomes of the one at a time technique [

31]. However, speedup is limited by the exponential growth of the tree with increasing depth. Zeigler et al [

32] introduced merging of states based on homomorphism concepts to mitigate against such growth. As illustrated on the right hand side of

Figure 1, they showed such merging can reduce tree growth from exponential to polynomial in depth thus significantly speeding up computation over that possible with cloning alone.

Parallelizations of such simulations have been developed in which simulations are run until a stochastic decision point is reached. At this point, the current simulation states and probabilities of branching are saved. Simulations are then spawned for possible branchings until successive downstream branching points are reached and the process is repeated until a satisfactory level of confidence in outcome distribution has been attained. Besides being efficient in exploration, this “paratemporal” approach is extremely parallelizable for great efficiency in execution on multiple processors.

However, although paratemporal simulations with a small number of branchings and state saves have been demonstrated to be effective, simple implementations of such solutions do not scale as the number of branches increases rapidly for large SoS of current interest.

In this paper, we tackle the scalability problem by first developing a formal framework covering conventional and proposed tree expansion algorithms for speeding up stochastic simulations while preserving desired accuracy. Based on the theory of modeling and simulation we review the definition of a discrete event stochastic model as an instance of a timed non-deterministic model. Then we show how a reduced deterministic model with random inputs can be derived from such a stochastic model that represents the results of cloning state and transition information at branching points. The reduced model is shown to be a homomorphic image of the original based on a correspondence restricted to non-deterministic states and multi-step deterministic sequences mapped into corresponding single step sequences. An illustrative example is discussed to illustrate the tree expansion framework in which the stochastic model takes the form of a binary tree isomorphic to the free monoid, {0,1}*. At each node, branching occurs with equal probability to nodes at the next level. A computation time of 1 unit is taken to transition from a node to its successor. The output at a state is the number of 1’s in its label. We derive the computation times for baseline, non-merging, and merging tree expansion algorithms to compute the distribution of output values at any given depth. The results show the remarkable reduction from exponential to polynomial dependence on depth effectuated by node merging. We relate these results to the reduced computation of binomial coefficients underlying Pascal’s triangle and discuss application of tree expansion to estimating temporal distributions in stochastic simulations involving serial and parallel compositions. Finally, we mention use cases estimating times to completion for complex processes and potential real world applications.

2. Formal Framework for Tree Expansion for Stochastic Simulation

We employ the theory of modeling and simulation [

33], based on systems theory [

34], to develop a formal framework based on Discrete Event Systems Specification (DEVS) for framing the representations needed for paratemporal simulations. As in

Figure 1, to capture the effect of cloning on the source stochastic simulation, we derive other representations including concepts of non-deterministic models and semigroup monoid algebras.

Definitions

We review some definitions to proceed.

Definition 1.

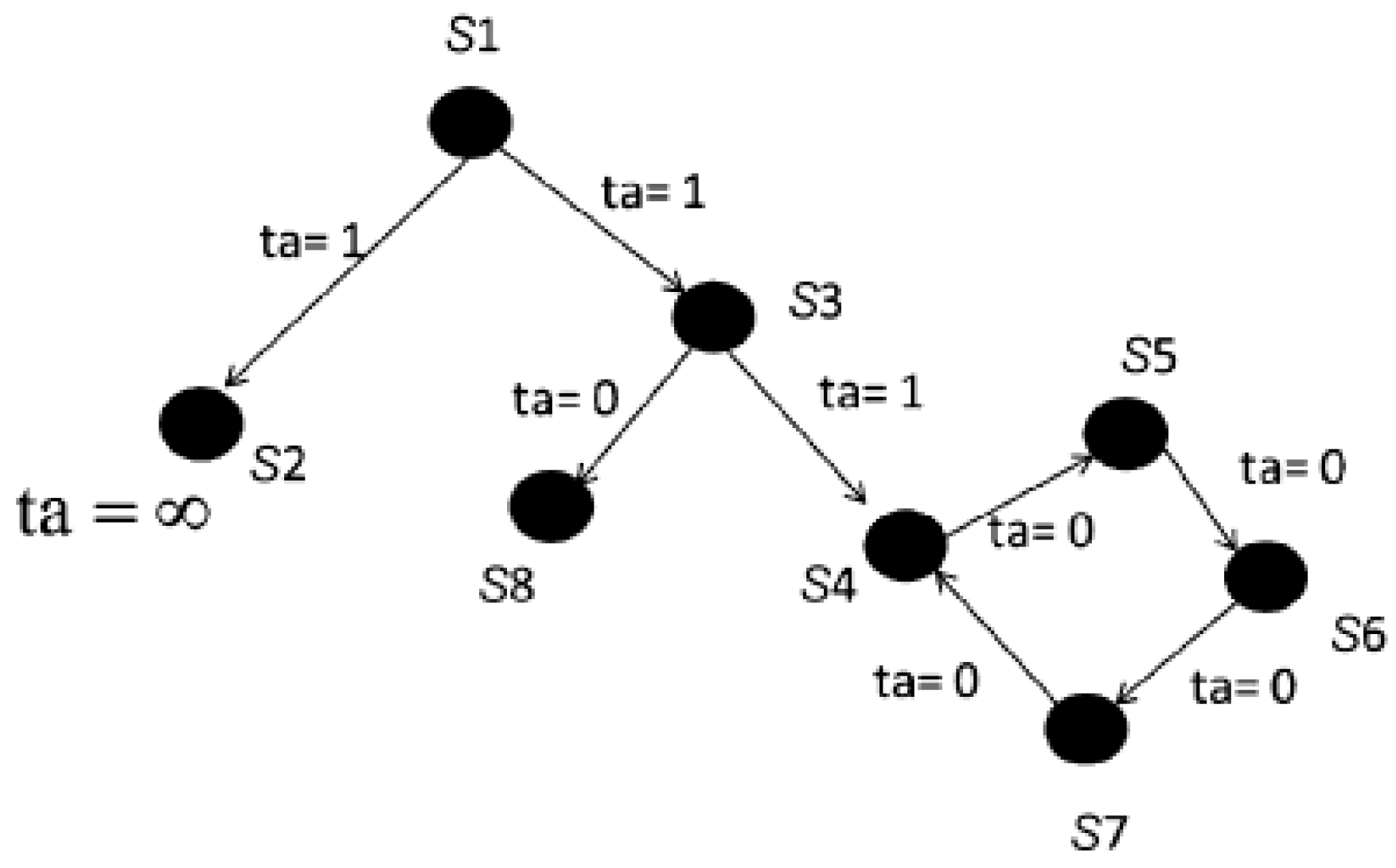

A timed non-deterministic model is defined by: M =<S, δ, ta >, where δ ⊆ S ×S is the non-deterministic transition relation, and ta : δ→R∞0 is the time advance function.

We say that M is

Not defined at a state, if there is no transition pair with the state as its left member,

Non-deterministic at a state, if the state is a left member of two transition pairs,

Deterministic at a state when there is exactly one outbound transition (a left member of exactly one transition pair).

Remark: Formulating a transition system in relational form as in Definition 1 allows us to include both stochastic and deterministic discrete event systems within a common framework as follows:

Figure 2.

DEVS-based framework for framing the representations needed for paratemporal simulations.

Figure 2.

DEVS-based framework for framing the representations needed for paratemporal simulations.

A stochastic model is a timed non-deterministic model defined at all of its states.

A deterministic model is a timed non-deterministic model deterministic at all its states.

Clearly, deterministic models are a subset of stochastic models.

In application to paratemporal simulation, a non-deterministic state is known as a random draw state. We make this identification in a later section after introducing DEVS Markov models.

Figure 3.

Timed non-deterministic model.

Figure 3.

Timed non-deterministic model.

Definition 2.

A state trajectory connecting a pair of states, s and s’ is a sequence s1 , s2 ,.., sn which starts with s and ends with s’ and satisfies the transition relation, i.e., where s1 = s , sn = s’ and δ(si ,si+1) for i=1,..,n-1.

Definition 3.

A deterministic state trajectory is a state trajectory containing only deterministic states. The time to traverse a deterministic state trajectory is the sum of the transition times associated with the successive pairs of states in its sequence.

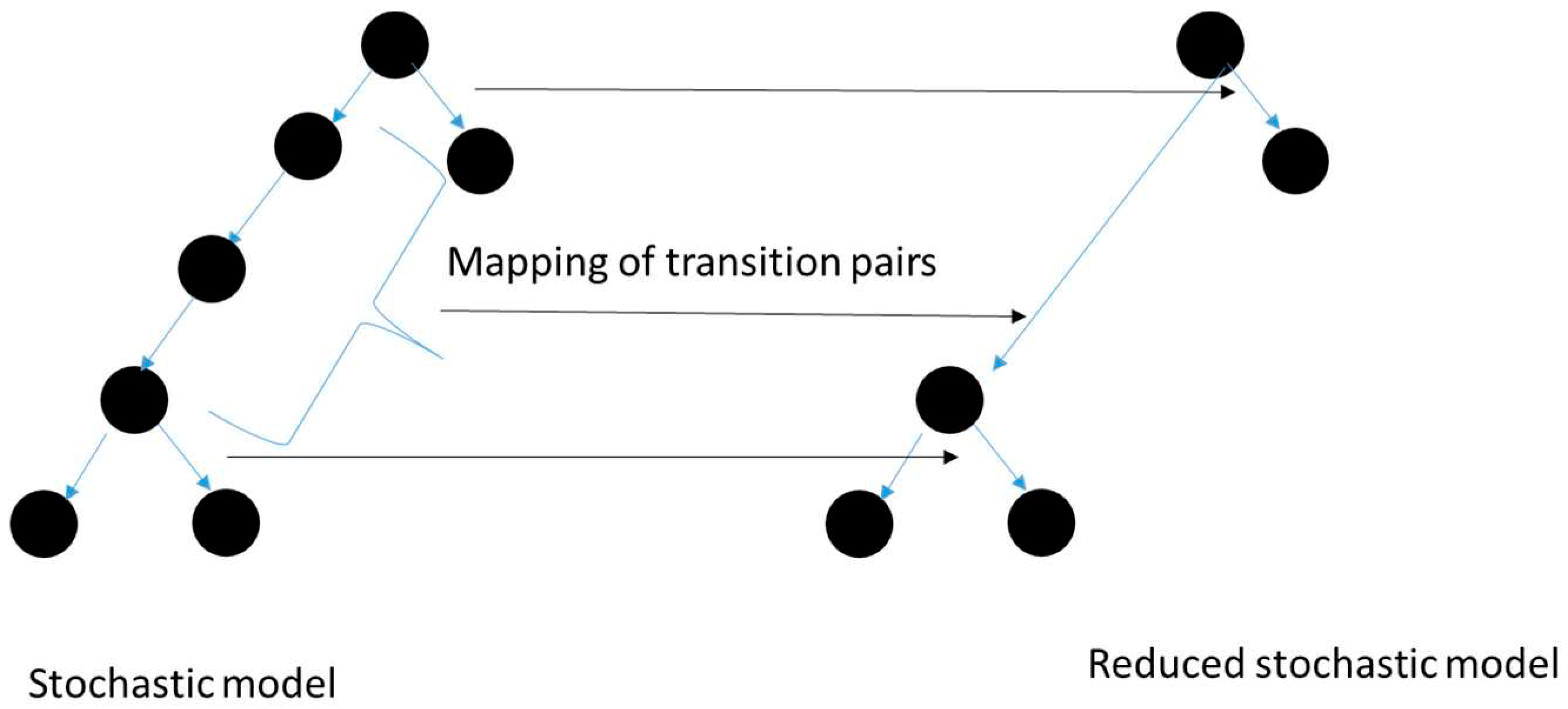

We can remove deterministic states from a stochastic model and replace multi-step deterministic trajectories by single step trajectories to represent the effect of cloning simulations. Given a stochastic model, M=<S, δ, ta > we define a reduced version that contracts deterministic sequences into single step transitions:

Definition 4. The clone-reduced version of stochastic model, M=<S, δ, ta > is

M’ =<S’, δ’, ta’ >

Where

S’⊆ S is the subset of non-deterministic states of M

δ’⊆ S’ ×S’ = {(s,s’)| if there is a deterministic state trajectory connecting s and s’}

and

ta’: δ’→R0∞

where

We can prove the

Assertion 1:

The reduced model is a homomorphic image of the original based on a correspondence restricted to non-deterministic states and multi-step deterministic sequences mapped into corresponding single step sequences.

We note that the transversal time from any non-deterministic state to any other is preserved in the reduced version. However, the advantage of constructing this representation is that the computation (in simulation) of a multistep sequence can be replaced by a look up of a table (cloning) when the branching is encountered subsequently.

Figure 4.

Mapping of Timed non-deterministic model to reduced version.

Figure 4.

Mapping of Timed non-deterministic model to reduced version.

Definition 5.

A Stochastic Input-Free DEVS has the structure [

33]

:

where Y, S, λ, ta have the usual definitions [

35].

Here Gint : S→2S is a function that assigns a collection of sets Gint (s) ⊆ 2S to every state s.

The probability that the internal transition carries a state s to a set G ∈ Gint (s) is given by a function Pint (s,G).

For S finite, we let

where

Pr(s, s’) is the probability of transitioning from

s to

s’.

As defined in [

33], the key to formalizing a semi-Markov model in DEVS is the definition of two structures. One is corresponds to the usual matrix of probabilities for state transitions. The other assigns to each transition pair a probability density distribution over time. The choice of next phase in the DEVS is made first by sampling the first matrix. Then the transition from the current phase to the just selected next phase is given a time of transition by sampling the distribution associated with that transition. More formally, this is formulated by:

Definition 6 A pair of structures,

Probability Transition Structure

PTS =<S, Pr>

and

Time Transition Structure

TTS =<S, τ>

gives rise to an

Input-Free DEVS Markov Model [

33]

MDEVS =<Y,SDEVS, δint , λ, ta >

where SDEV S = S × [0, 1]S × [0, 1]S

with typical element (s, γ1,γ2) with γi : S →[0, 1], i = 1, 2

where

δint: SDEV S → SDEV S is given by:

δint (s, γ1,γ2) = s’= (SelectPhase Gint (s, γ1), γ1’, γ2’)

and ta : SDEV S →R+0,∞ is given by:

ta(s,γ1,γ2) = SelectSigma TT S (s, s’,γ2)

and γi’ = Γ (γi ), i = 1, 2

The input-free DEVS Markov Model is introduced as a concrete implementation for non-deterministic models. On the one hand such models are constructible in computational form in such environments as MS4 Me [

36]. On the other hand we can explicitly define how such models give rise to non-deterministic models as in the following

:

Assertion 2:

An input free DEVS Markov model MDEV S =<Y,SDEV S, δint , λ, ta > specifies a non-deterministic model M =<S’, δ’, ta’ >,

where S’= SDEV S,

δ’ ⊆ S’ ×S’ is given by: (s1,s2) is in δ’ if, and only if, there exists γ1 in [0, 1],γ2 in [0, 1], such that

δint (s1, γ1,γ2) = s2.

and ta’ : δ→R∞0 is given by ta’(s1,γ1,γ2) for the same pair ( γ1,γ2) that placed (s1,s2) in δ’.

Essentially, this assertion shows how a transition from state s1 to s2 is possible if there is a random selection of s2 from the set of possible next states of s1 (as determined by the seed γ1 and the time for such a transition is given by a sampling from the distribution for traversal times determined by the seed γ2.

3. Illustrative Example

To create the models needed to illustrate the framework of

Figure 1, consider a binary tree of depth 3 with root labelled by the empty string and each node labelled by a string of 0’s and 1’s corresponding to the path to it from the root. At each node a choice is made to select the successor to which to transition with equal probability. A computation time of 1 unit is taken to transition from a node to its successor. The output at a state is the number of 1’s in its label. We write the formal representation as a DEVS Markov Model as follows:

MDEV S=<Y, SDEV S, δint , λ, ta >

Y = {0, 1, 2, 3}

S = {0, 1, 00, 01, 10, 11, 000, 001,…111} (nodes in a binary tree of depth 3 labelled by strings corresponding to the path accessing them) SDEV S = the set of pairs of the form (s, γ) where s is a member of S (a node) and γ is a state of an ideal random number generator, such that Γ (γ ) is the next state of the random generator (for simplicity, the time advance will be constant so an additional random variable is not needed).

Gint (s) = {s0,s1}, the subset of nodes that are immediate successors of node s in the binary tree

and

s’= δint (s, γ) =( SelectPhase Gint (s, γ), Γ (γ) )

where SelectPhase Gint (s, γ) uses the random number state, γ to select the successor node from Gint(s) with equal probability.

ta(s,γ) = 1

and

λ(s) =number of 1’s in the label of s.

The desired outcome of the simulation is the average of the values of the nodes.

To illustrate the applicability of homomorphism and minimal realization concept, we will show how it provides insight into the merging of states for tree expansion.

We will compare three algorithms:

The baseline algorithm generates all trajectories one a time, accumulates the number of 1’s for each, and averages the results.

The tree expansion algorithm generates all nodes in breadth-first traversal without repetition obtaining the same information and performing the same average.

The node merging algorithm based on the minimal realization modifies tree expansion by maintaining only the representatives of equivalent classes as successive levels are generated while maintaining the size of the classes as they are developed. The values of the classes are summed weighted by the respective sizes to obtain the desired average.

The node merging algorithm is sketched in the following:

Node merging tree expansion algorithm

A node n contains data {s, num) where s is a string in {0,1}* and num is the number of nodes equivalentTo n.

The root node = (λ,0) // λ is the empty string

Initiation: Current node = root node; newLeaves = {}, oldLeaves = { (λ,0)}

Termination: depth = D

Output: For each i = 1,2,,,D the number of strings having number of ones equal to i.

Recursive step:

While (depth <D)

Depth = 0

For each node, n = (s, num) in leaves{

For each branch, b in {0, 1}{

Create child, c= {sb, ,num) // extend parent’s string and inherit parent’s number of represented equivalents

If c isEquivalentTo some node, m = {t, num’) in oldLeaves,

Then set m = {t, num’+num)

Else add c to newLeaves.

}

depth = depth+1

oldLeaves = newLeaves, newLeaves = {}

}

n = (s, num) isEquivalentTo m = {t, num’) if,and only if, s and t have the same number of ones

//Note that only the leaves at each level (including at the final depth) are kept as the expansion advances as required by the required output.

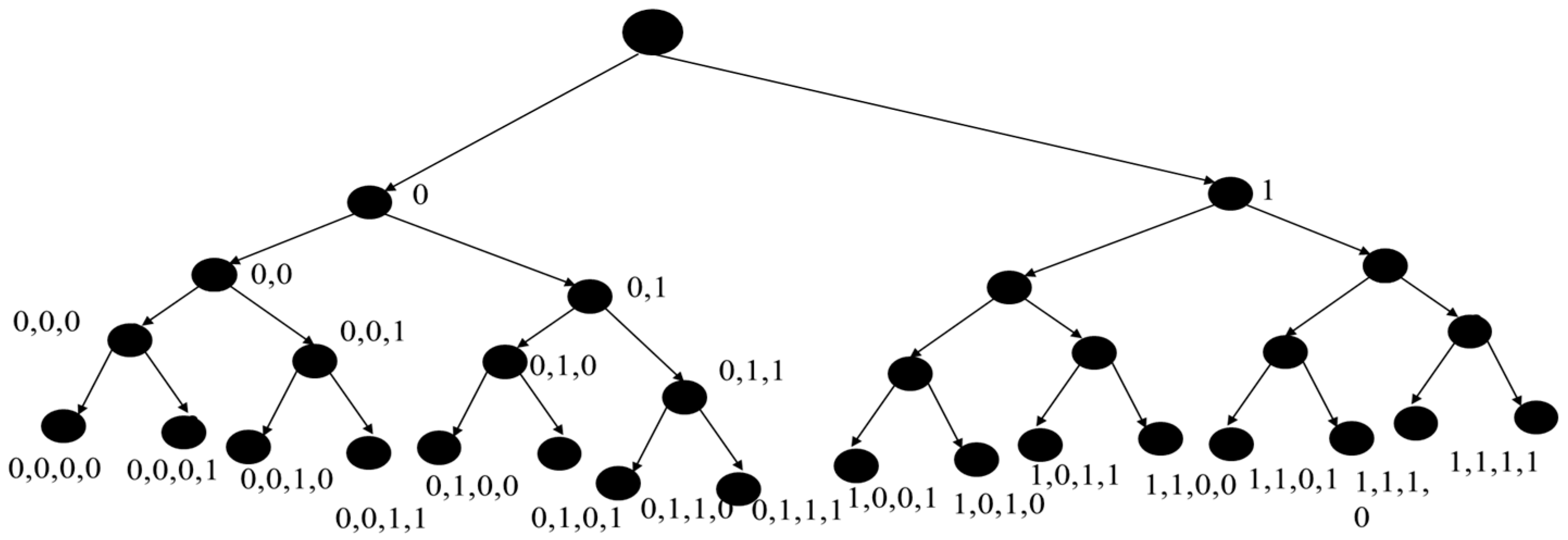

To analyze this example, we will start with the semigroup monoid system (as in the Appendix) unfolded to the depth = 4 as shown in

Figure 5. The leaves of the tree are labelled with the final states listed above and traversing the tree from root to leaves reveals 16 branching routes. We will proceed to obtain various computation times generalized to the case of a tree of arbitrary depth

n as presented in Table 2. The computation time for baseline algorithm is computed as the number of branching routes (2

n) times the depth (n) taking unit computation time per step. The smallest number of computations when reusing earlier nodes is to expand the tree starting at the root and proceeding to expand new leaves successively at each level in breadth-first traversal. This requires 2(2

n-1) computations as shown in the table. Therefore the reduction in computation time is n2

n/2(2

n-1) which is of order, O(n).

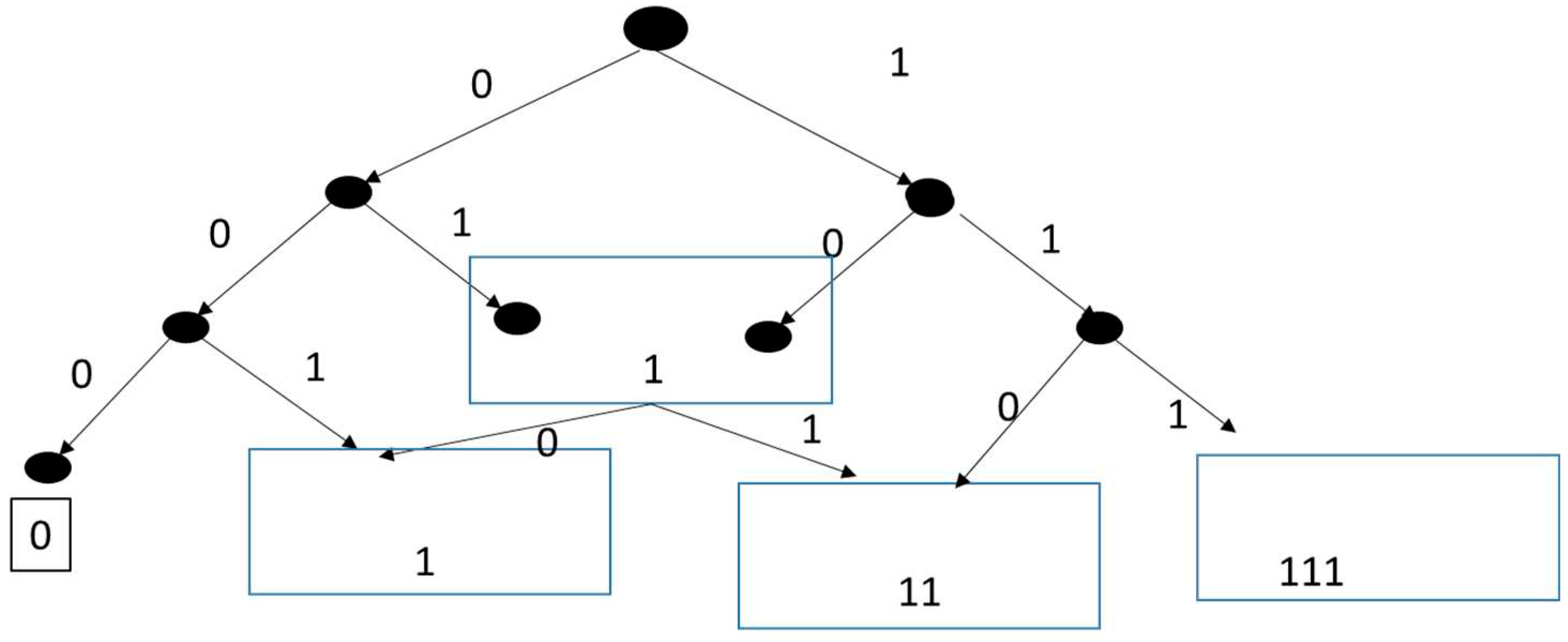

The minimal realization of this model, shown in

Figure 6 to depth = 3, recognizes that all nodes labeled (x1,x2,x3) with the same sum (x1+x2+x3) can be grouped into the same congruence class. The justification of congruence is easy to see in this case: the 0 input keeps such an element in the same class, while the 1 input transitions it to the class having a sum increased by 1. With merging of nodes, the tree expands in a manner emulating Pascal’s triangle for computing binomial coefficients [

37]. At any depth n there are a total of 2

n subsets of sizes ranging from 0 to n with cardinalities given by the binomial coefficients. For example, at depth 3, there are 1,3,3,1 subsets of sizes 0,1,2,3 respectively. With the size of a subset representing the number of 1’s in the same equivalence class we see that the average number of 1’s will equal n/2 as expected. Importantly, the number of nodes, and hence the computation time, grows only as the square of n rather than exponentially as shown in the

Table 1. The computation time is now O(2) (square) in the depth of the tree and the reduction is of

exponential order – which would be exceedingly impressive to achieve in real world application!

4. Empirical Confirmation of Theory Predictions

To test the theory and its implementation, the illustrative example was implemented in Java and executed to compare computation times with those predicted from

Table 1.

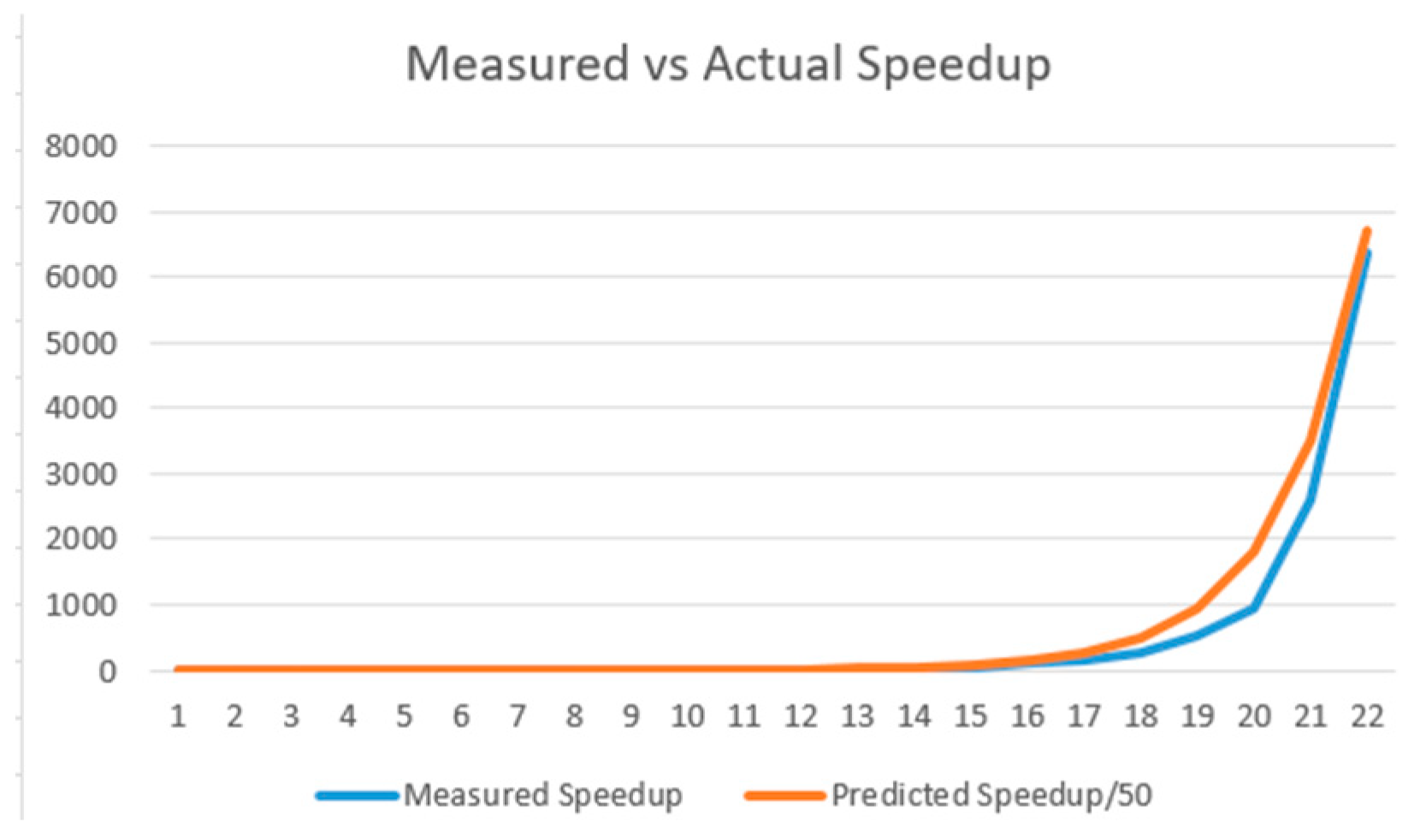

Figure 7 shows that the relative computation times of the merged, unmerged, and baseline algorithms fall in order of that predicted in

Table 1. However,

Figure 8 shows that the actual speedup realized by merging relative to the baseline is approximately 50 times less than predicted. Nevertheless, the speedup achieved at depth 22 of approximately 7000 is still highly significant. Note: the baseline algorithm exceeds memory available at depth 23 due to the exponential node growth. Trees up to depth 1000 with 10 replications for each were tested to get the timing results and all yielded the correct outcome distribution.

5. Tree Expansion with Merging Applied to Serial and Parallel Compositions

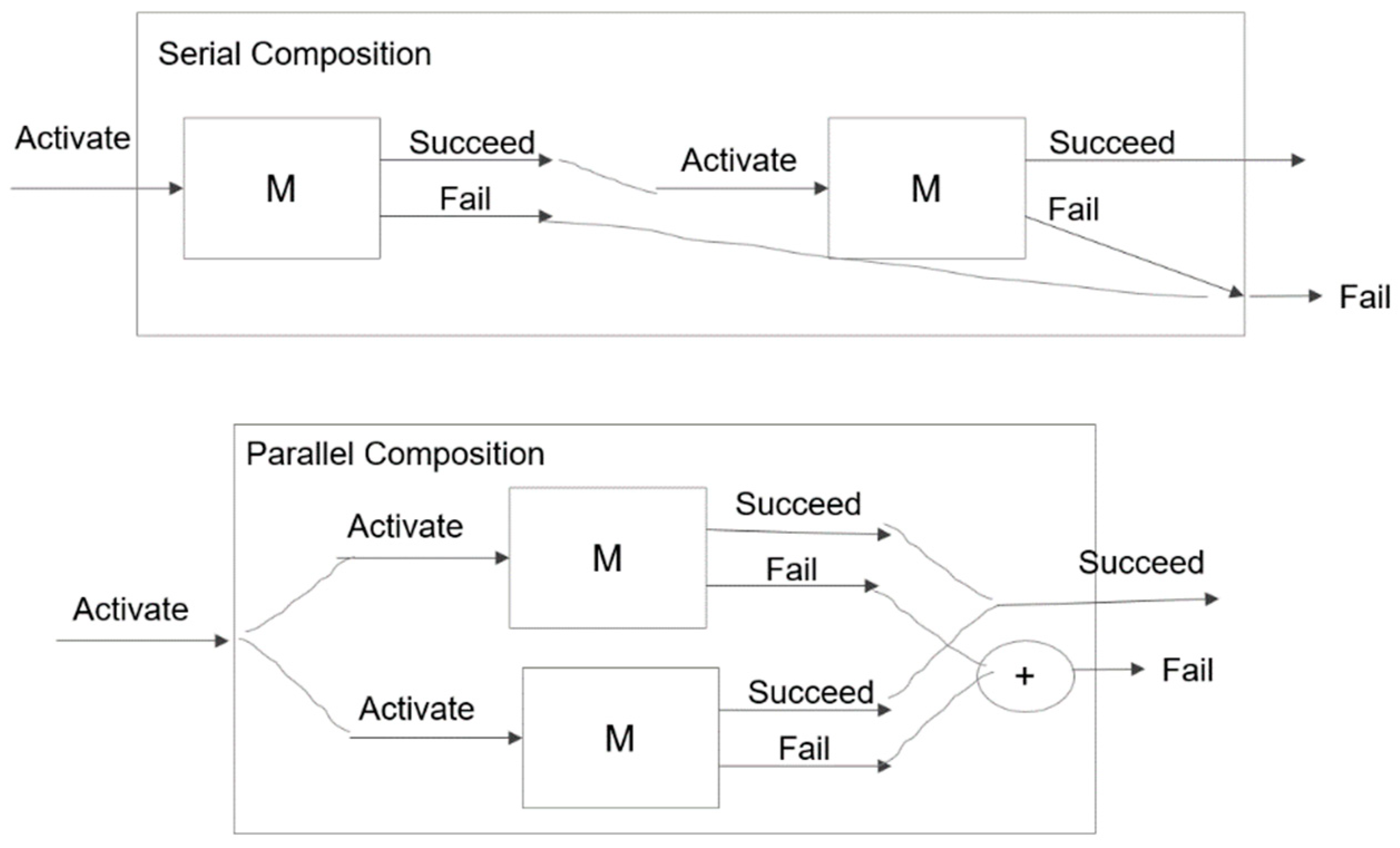

To succeed, a serial composition entails the success of each of its components; likewise, it fails if any one of its components fail [

38]. In contrast, the success of a parallel composition requires that only one of its components succeeds, while its failure entails the failure of all the components.

The component models in the compositions are of the form of a DEVS Markov model (not including input and output) as shown in

Figure 8.

The transition structure of the model is specified by two parameters, PSucceed the probability of success, and success the probability distribution for time required to achieve success. These populate the values needed for the probability and time transition structures needed for the definition of the model, which is given as:

MDEV S=<Y, SDEV S, δint , λ, ta >

Y = {Succeed,Fail}

S = {Start, Succeed, Fail}

SDEV S = the set of triples of the form (s, γ,) where s is a member of S (a node) and γ, are states of ideal random number generators for selecting between the transitions from Start to Succeed or Fail and for selecting the time distribution for the transition to Succeed, if selected. The time for the transition to Fail is not of interest here so no random seed is associated with it.

Gint (Start) = {Succeed,Fail} the subset of nodes that are immediate successors of node Start and s’= δint (Start, γ,) =( SelectPhase Gint (Start, γ), Γ (γ),) where the latter uses the random number seed, γ to select Succeed with probability PSucceed and Fail with probability1- PSucceed ta(Succeed, γ,) = ( SelectSigma Gint (Start, γ, )) which selects the time required to succeed from the given distribution, success and λ is the time selected for the time advance.

Serial and Parallel compositions in

Figure 9 are defined using the standard DEVS coupled model specifications [Zeigler, Muzy, and Kofman, 2018]. These paired configurations are easily generalized to finite numbers of components where for the serial composition, components are placed in a sequence with the Success output port of one connected to the Activate input port of the next; and for the parallel composition all components receive activation simultaneously with all output Success ports coupled to the overall output Success port. The desired outcome of the simulations of the compositions is the probability distribution of time needed for success. In the serial case a sampled value of this outcome is the sum of the time samples from each component since all have to succeed for the whole to succeed. In the parallel case, a sampled outcome is the minimum of the sampled durations of the components since overall success is achieved by the first to succeed. Analytic solutions such as by Rice [

38] are possible given analytic input distributions but stochastic simulation is needed otherwise.

5.1. Computation Time Required for Serial and Parallel Compositions

In application to serial and parallel compositions the number of components determines the depth of the tree, n. The temporal distribution of each component is assumed to be known and represented by a discrete probability density over an interval divided into G segments where G is called the number of granules and determines the accuracy of the computed outcome. Then the unmerged tree expands with Gn nodes at depth n. Merging in the case of serial composition only adds G nodes at each level thus reducing the growth in nodes to n*G. This is so since at each successive level the range of the combined ranges is bounded above by the sum of the end points thus adding G nodes. Moreover, at each level the number of operations is at most n*G2 since the n*G nodes are combined with the G granules to create the next level. Thus the incremental computation time is n*G2 and the computation time required should grow as O((nG)2), i.e. as the square of depth and number of granules.

Merging in the case of parallel composition does not suffer any tree expansion since the combined range of a minimization is the original range, Thus by the reasoning above the computation time required for depth n should grow as O((nG 2), i.e. linearly with depth and square of granules.

6. Related Work

DEVS has served as a basis for formalization [

39,

40] and study of multiresolution constructions underlying multifidelity simulations [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Also DEVS has been employed as a basis for simulation of Markov Decision Process (MDP) models employing its modular and hierarchical aspects to improve the explainability of the models with application to optimization processes such as financial, industrial, etc. [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. Capocchi, Santucci, and Zeigler [

54] introduced a DEVS-based framework to construct and aggregate Markov chains using a relaxed form of lumpability to enhance understanding of complex Markov search spaces. However, the methodology is limited to selecting optimal partitions according to a metric that compares Markov chains based on their respective steady states. Practical application is limited since these are not generally available in problem specification. In contrast, paratemporal and cloning simulation techniques are intended for application to stochastic simulation in general, and offer opportunities for parallelism and cloning of state information. However, they have not demonstrated the ability to overcome the combinatorial explosion of branching arising from multiple choice points. Absence of such scalability presents a major hurdle that must be overcome to implement such techniques. Nutaro et al [

31] showed the speedup of tree expansion methods is limited by the exponential growth of the tree with increasing depth. Zeigler et al [

55] introduced merging of states based on homomorphism concepts to mitigate against such growth. Here we showed that homomorphic merging of states can be formally characterized using DEVS Markov modeling and simulation theory to show examples where such merging can achieve reduction from exponential to polynomial computational effort.

7. Conclusions and Further Work

We have developed a formal framework covering conventional and proposed tree expansion algorithms for speeding up stochastic simulations while preserving desired accuracy. Based on the theory of modeling and simulation showed how a reduced deterministic model with random inputs can be derived from such a stochastic model that represents the results of cloning state and transition information at branching points. The reduced model was shown to be a homomorphic image of the original based on a correspondence restricted to non-deterministic states and multi-step deterministic sequences mapped into corresponding single step sequences. An example was discussed to illustrate the tree expansion framework in which the stochastic model takes the form of a binary tree allowing us to derive the computation times for baseline, non-merging, and merging tree expansion algorithms to compute the distribution of output values at any given depth. The results show the remarkable reduction from exponential to polynomial dependence on depth effectuated by node merging. We related these results to the reduced computation of binomial coefficients underlying Pascal’s triangle.

Applications of node merging tree expansion algorithms are currently being studied in simulations of space-based threat responses to estimate the probability of successfully identifying, tracking, and targeting hypersonic missiles within tight deadlines [

38], as well as to attrition modeling employing stochastic interactions between opposing forces [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. In such models temporal duration outcomes in the form of probabilistic temporal distributions play a major role and homomorphic merged tree expansion enables much faster computation of outcome distributions when analytic solutions are lacking.

Funding

This research was partially supported by RTSync internal funding and received no ex-ternal funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Sang Won Yoon, Professor, and Christian Koertje, Graduate Research Associate at the Watson Institute for Systems Excellence at The State University of New York at Binghamton, NY, for their help in working on the algorithm implementations.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Please refer to [

62,

63] for a detailed exposition.

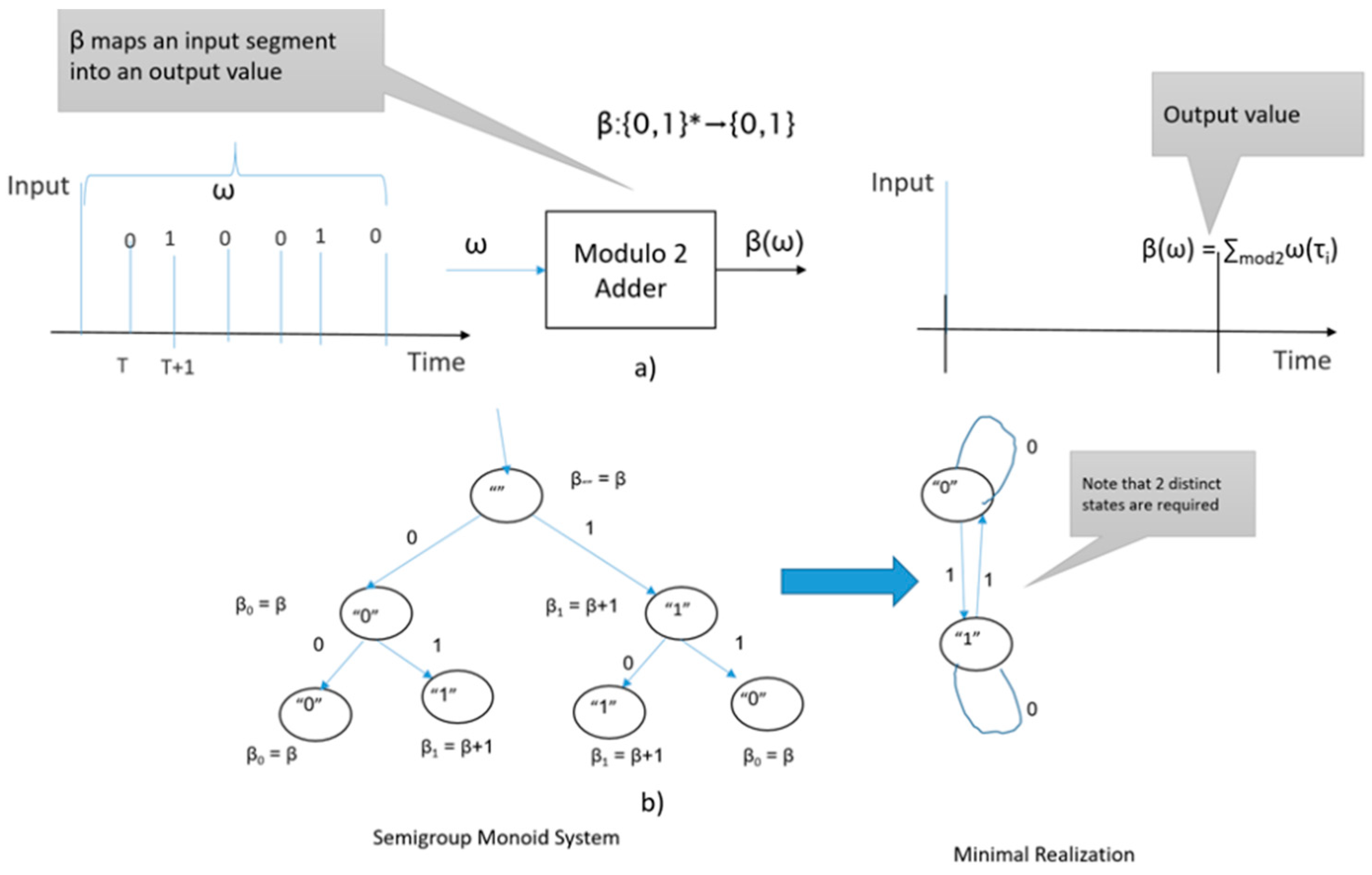

We define the behavior of a system formally as a function mapping input segments to output segments (

Figure 6). We seek a DEVS model at the state description level that generates the defined behavior and then try to show it is a minimal realization or attempt to reduce it to one that is minimal.

We briefly review the approach to deriving a minimal realization from an input time function description.

Figure A1a shows the behavior of a modulo 2 adder and the minimal realization is in

Figure A1b. The latter has two states corresponding to the two distinct nodes with transitions reflecting and alternating pattern exhibited by the derivatives of the behavior β in the tree. The alternating pattern is manifest by noticing that β

0(ω) = β(0ω) and β

1 (ω) = β(1ω) so that the state “0” transitions to itself under input 0 and transitions to the state “1” under input 1.

Figure A1.

a) Mapping input segments to output segments b) States Reduction and Minimal realization.

Figure A1.

a) Mapping input segments to output segments b) States Reduction and Minimal realization.

References

- Müller Juliane, Christine A. Shoemaker, Robert Piché, 2013 SO-MI: A surrogate model algorithm for computationally expensive nonlinear mixed-integer black-box global optimization problems, Computers & Operations Research,Volume 40, Issue 5, , Pages 1383-1400,. [CrossRef]

- Zabinsiky, Z.B. Stochastic Adaptive Search Methods: Theory and Implementation. In Handbook of Simulation Optimization; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 293–318. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.H.; Seo, K.M.; Kim, T.G. Simulation-based optimization for design parameter exploration in hybrid system: A defense system example. Simulation 2013, 89. [CrossRef]

- Tolk, A. Simulation-Based Optimization: Implications of Complex Adaptive Systems and Deep Uncertainty. Information 2022, 13, 469. [CrossRef]

- Davis, P. 2023 Broad and Selectively Deep: An MRMPM Paradigm for Supporting Analysis. Information, 14(2), 134. [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.K.; Popper, S.W. Confronting Model Uncertainty in Policy Analysis for Complex Systems: What Policymakers Should Demand. J. Policy Complex Syst. 2019, 5, 181–201. [CrossRef]

- Hüllermeier, E.; Waegeman, W. Aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty in machine learning: An introduction to concepts and methods. Mach. Learn. 2021, 110, 457–506. [CrossRef]

- Kruse, R.; Schwecke, E.; Heinsohn, J. Uncertainty and Vagueness in Knowledge Based Systems: Numerical Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [CrossRef]

- Kwakkel, J.H.; Haasnoot, M. Supporting DMDU: A Taxonomy of Approaches and Tools. In Decision Making imder Deep Uncertainty: Rom Theory to Practice; Marchau, V.A., Warren, E.W., Bloemen, P.J., Popper, S.W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 355–374. [CrossRef]

- Marchau, V.A.W.J.; Walker, W.E.; Bloemen, P.J.T.M.; Popper, S.W. Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty: From Theory to Practice; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Amaran, S.; Sahinidis, N.V.; Sharda, B.; Bury, S.J. Simulation optimization: A review of algorithms and applications. Ann. Oper. Res. 2016, 240, 351–380. [CrossRef]

- Tsattalios Spyridon, Ioannis Tsoukalas, Panagiotis Dimas, Panagiotis Kossieris, Andreas Efstratiadis, Christos Makropoulos, 2023Advancing surrogate-based optimization of time-expensive environmental problems through adaptive multi-model search, Environmental Modelling & Software,Volume 162.

- Xu, J.; Huang, E.; Chen, C.H.; Lee, L.H. Simulation optimization: A review and exploration in the new era of cloud computing and big data. Asia Pac. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 32. [CrossRef]

- Suman, B.; Kumar, P. A survey of simulated annealing as a tool for single and multiobjective optimization. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2006, 57, 1143–1160. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ong, Y.S.; Nair, P.B.; Keane, A.J.; Lum, K.Y. Combining global and local surrogate models to accelerate evolutionary optimization. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. C 2007, 37. [CrossRef]

- Liu Bo, Slawomir Koziel, Qingfu Zhang, 2016 A multi-fidelity surrogate-model-assisted evolutionary algorithm for computationally expensive optimization problems, Journal of Computational Science, Volume 12, , Pages 28-37. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.A.; Hackman, D.V.; Lad, A. Better Analysis Using the Models and Simulations Hierarchy. J. Def. Model. Simul. 2018, 15, 279–288. [CrossRef]

- Moon, I.C.; Hong, J.H. Theoretic interplay between abstraction, resolution, and fidelity in model information. In Proceedings of the 2013 Winter Simulation Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 8–11 December 2013. [CrossRef]

- Choi , SH, Kyung-Min Seo and Tag Gon Kim, 2017 Accelerated Simulation of Discrete Event Dynamic Systems via a Multi-Fidelity Modeling Framework, Applied Sciences, 7(10), 1056, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Celik, N.; Lee, S.; Vasudevan, K.; Son, Y.J. DDDAS-based multi-fidelity simulation framework for supply chain systems. IIE Trans. 2010, 42. [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Seo, K.M.; Kim, T.G. DEXSim: An experimental environment for distributed execution of replicated simulators using a concept of single simulation multiple scenarios. Simulation 2014, 90. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, T.G. Multi-fidelity modeling & simulation methodology for simulation speed up. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGSIM Conference on Principles of Advanced Discrete Simulation, Denver, CO, USA, 18–21 May 2014.

- Keeney, R.; Raiffa, H. Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Tradeoffs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; McGinnis, L.F.; Zhou, C. On fidelity and model selection for discrete event simulation. Simulation 2012, 88. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Cristobal, A.; Palmer, P.R.; Parks, G.T. Multi-fidelity Simulation modeling in optimization of a hybrid submarine propulsion system. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications, Birmingham, UK, 30 August–1 September 2011.

- Ören Tuncer, Bernard P. Zeigler, Andreas Tolk, 2023 Body of Knowledge for Modeling and Simulation: A Handbook by the Society for Modeling and Simulation International, Springer,.

- Park, H.; Fishwick, P.A. A GPU-based application framework supporting fast discrete-event simulation. Simulation 2010, 86. [CrossRef]

- Lammers, C., J. Steinman, M. Valinski, K. Roth. “Five-Dimensional Simulation for Advanced Decision Making,” SPIE—Enabling Technologies for Simulation Science XIII, Paper SPIE 7348-16.

- Li, Xiaosong, Wentong Cai, and Stephen J. Turner. 2017. Cloning Agent-Based Simulation. ACM Trans. Model. Comput. Simul. 27, 2, Article 15 (July 2017), 24 pages.

- Yoginath, S. B., M. Alam and K. S. Perumalla, 2019 "Energy Conservation Through Cloned Execution Of Simulations," Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), 2019, pp. 2572-2582.

- Nutaro et al 2024 Using simulation cloning to sample without duplication (in process).

- Zeigler, BP. et al 2024 The Utility of Homomorphism Concepts in Simulation: Building Families of Models from Base-Lumped Model Pairs, Simulation J.(in process).

- Zeigler, B.P.; Muzy, A.; Kofman, E. Theory of Modeling and Simulation: Discrete Event Iterative System Computational Foundations; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Wymore, W.A. A Mathematical Theory of Systems Engineering—The Elements; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1967.

- Alshareef, A.; Seo, C.; Kim, A.; Zeigler, B.P. DEVS Markov Modeling and Simulation of Activity-Based Models for MBSE Application. In Proceedings of the 2021 Winter Simulation Conference, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–15 December 2021.

- Zeigler, B. P., Seo, C., and Kim, D. 2013 “DEVS Modeling and Simulation Methodology with MS4 Me Software”. Spring Sim San Diego, CA, USA.

- Wikipedia 2023 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pascal%27s_triangle[accessed 2023].

- Rice, Roy E 2022. Calculating the Probability of Successfully Executing the Kill Chain to Analyze Hypersonics, Phalanx, Spring, Vol. 55, No. 1, pp. 22-27.

- Baohong, L. A Formal Description Specification for Multi-resolution Modeling (MRM) Based on DEVS Formalism and Its Applications. J. Def. Model. Simul. Appl. Methodol. Technol. 2004, 4, 229–251. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, L.; Lim, A.; Bowen, S.; Ören, T. Requirements and Design Principles for Multisimulation With Multiresolution Multistage Models. In Proceedings of the 2007 Winter Simulation Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 9–12 December 2007.

- Davis, P.K.; Bigelow, J.H. Experiments in Multiresolution Modeling (MRM); RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1998; Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1004.html (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Davis, P.K.; Hillestad, R. Families of Models That Cross Levels of Resolution: Issues for Design, Calibration, and Management. In Proceedings of the 1993 Winter Simulation Conference, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 12–15 December 1993; pp. 1003–1012.

- Davis, P.K.; Hillestad, R. Proceedings of Conference on Variable Resolution Modeling, Washington DC, 5–6 May 1992; RAND Corp.: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1992.

- Davis, P.K.; Reiner, H. Variable Resolution Modeling: Issues, Principles and Challenges; N-3400; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1992.

- Hadi, M.; Zhou, X.; Hale, D. Multiresolution Modeling for Traffic Analysis: Case Studies Report; U.S. Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Rabelo, L.; Park, T.W.; Kim, K.; Pastrana, J.; Marin, M.; Lee, G.; Nagadi, K.; Ibrahim, B.; Gutierrez, E. Multi Resolution Modeling. In Proceedings of the 2015 Winter Simulation Conference; Yilmaz, L., Chan, V., Mood, I., Roemer, T., Macal, C., Rossetti, M., Eds.; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 2523–2534.

- Barbieri Emanuele. Discrete Event Modeling and Simulation of Large Markov Decision Process, Application to the Leverage Effects in Financial Asset Optimization Processes. Performance Doctoral Diss., Université Pascal Paoli, 2023.

- Folkerts, H.; Pawletta, T.; Deatcu, C.; Santucci, J.; Capocchi, L. An Integrated Modeling, Simulation and Experimentation Environment in Python Based on SES/MB and DEVS. In Proceedings of the SummerSim-SCSC, Berlin, Germany, 22–24 July 2019.

- Wilsdorf, P.; Heller, J.; Budde, K.; Zimmermann, J.; Warnke, T.; Haubelt, C.; Timmermann, D.; van Rienen, U.; Uhrmacher, A.M. A Model-Driven Approach for Conducting Simulation Experiments. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7977. [CrossRef]

- Juan, B.-R.; Besada-Portas, E.; López-Orozco, J.A. Cloud DEVS-based computation of UAVs trajectories for search and rescue missions. J. Simul. 2022, 16, 572–588. [CrossRef]

- Valdemar Vicente Graciano Neto, Mohamad Kassab Modeling and Simulation for Smart City Development,in What Every Engineer Should Know About Smart Cities Rutlege 2024.

- Gourlis, G.; Kovacic, I. Energy efficient operation of industrial facilities: The role of the building in simulation-based optimization. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 410, 012019. [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Gu, P.; Chen, Z. SES-X: A MBSE methodology based on SES/MB and XLanguage. Inf. J. 2023, 14, 23. [CrossRef]

- Capocchi Laurent, Jean-Francois Santucci, Bernard P. Zeigler, Markov chains aggregation using discrete event optimization via simulation. SummerSim '19: Proceedings of the 2019 Summer Simulation ConferenceJuly 2019Article No.: 7 Pages 1–12.

- Zeigler, BP. et al 2024 The Utility of Homomorphism Concepts in Simulation: Building Families of Models from Base-Lumped Model Pairs, Simulation J.(in process).

- Zeigler, BP., Constructing and Evaluating Multi-Resolution Model Pairs: An Attrition Modeling Example, The Journal of Defense Modeling and Simulation: Applications, Methodology, Technology, 14(4) June 26, 2017; pp. 427–437. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.G.; Sung, C.H.; Hong, S.Y.; Hong, J.H.; Choi, C.B.; Kim, J.H.; Seo, K.M.; Bae, J.W. DEVSim++ toolset for defense modeling and simulation and interoperation. J. Def. Model. Simul. 2011, 8. [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.K. Exploratory Analysis and Implications for Modeling. In New Challenges, New Tools for Defense Decisionmaking; Johnson, S., Libicki, M., Treverton, G., Eds.; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 255–283.

- Seo, K.M.; Choi, C.; Kim, T.G.; Kim, J.H. DEVS-based combat modeling for engagement-level simulation. Simulation 2014, 90. [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.M.; Hong, W.; Kim, T.G. Enhancing model composability and reusability for entity-level combat simulation: A conceptual modeling approach. Simulation 2017, 93. [CrossRef]

- Tolk, A. Engineering Principles of Combat Modeling and Distributed Simulation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 79–95. ISBN 978-0-470-87429-5.

- McNaughton, R. H. Yamada 1960 Regular Expressions and State Graphs for Automata IRE Transactions on Electronic Computers (Volume: EC-9, Issue: 1 , March 1960).

- Zeigler, BP., 2021 DEVS-Based Building Blocks and Architectural Patterns for Intelligent Hybrid Cyberphysical System Design, Information, 12(12), 531. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).