Submitted:

18 January 2024

Posted:

18 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

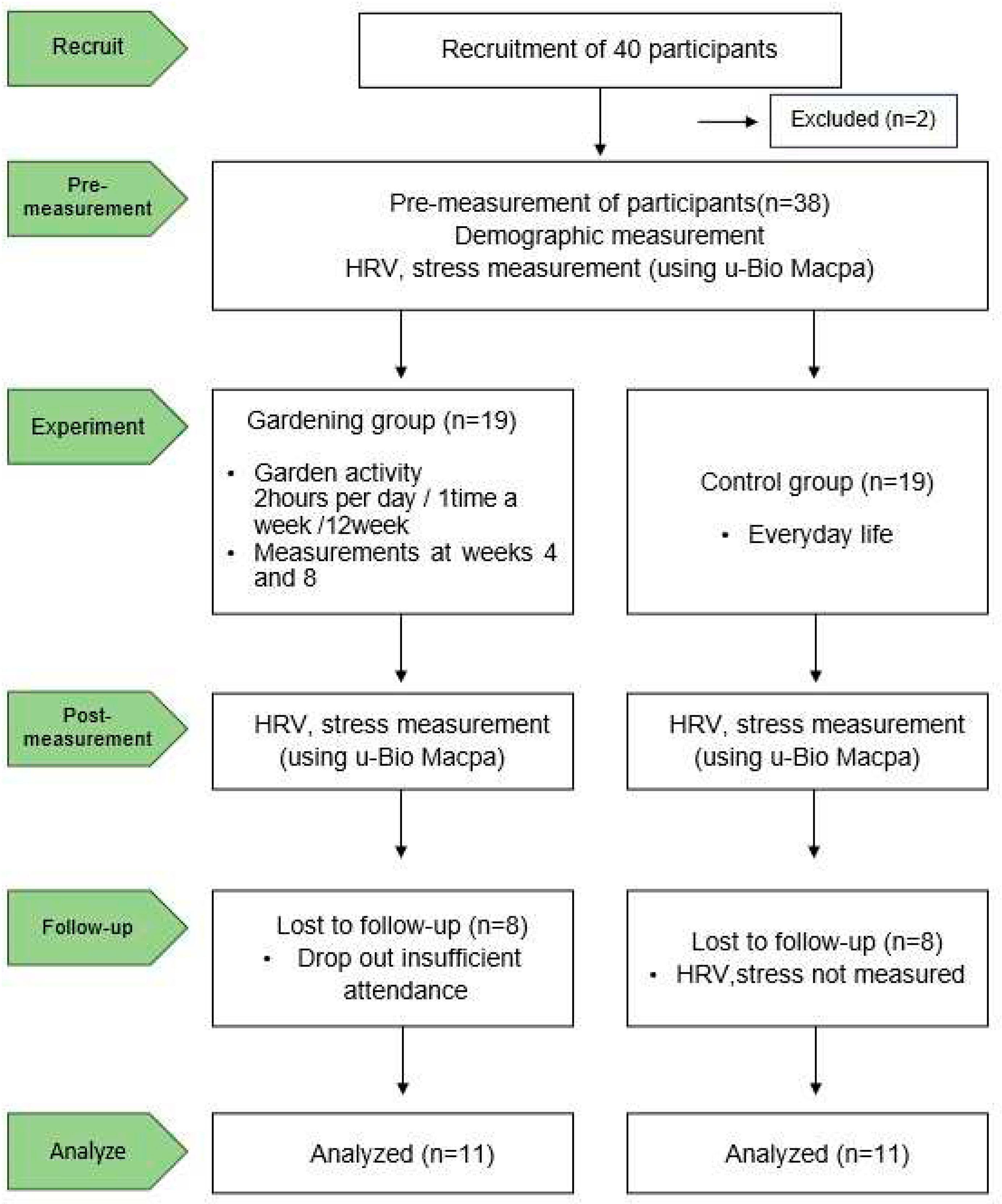

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.2.1. Healing Garden Activity Program

2.2.2. Measuring Tool

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pre- homogeneity Test of Gardening group and Control group

3.2. Changes in stress and TP, SDNN, and RMSSD of the Gardening group

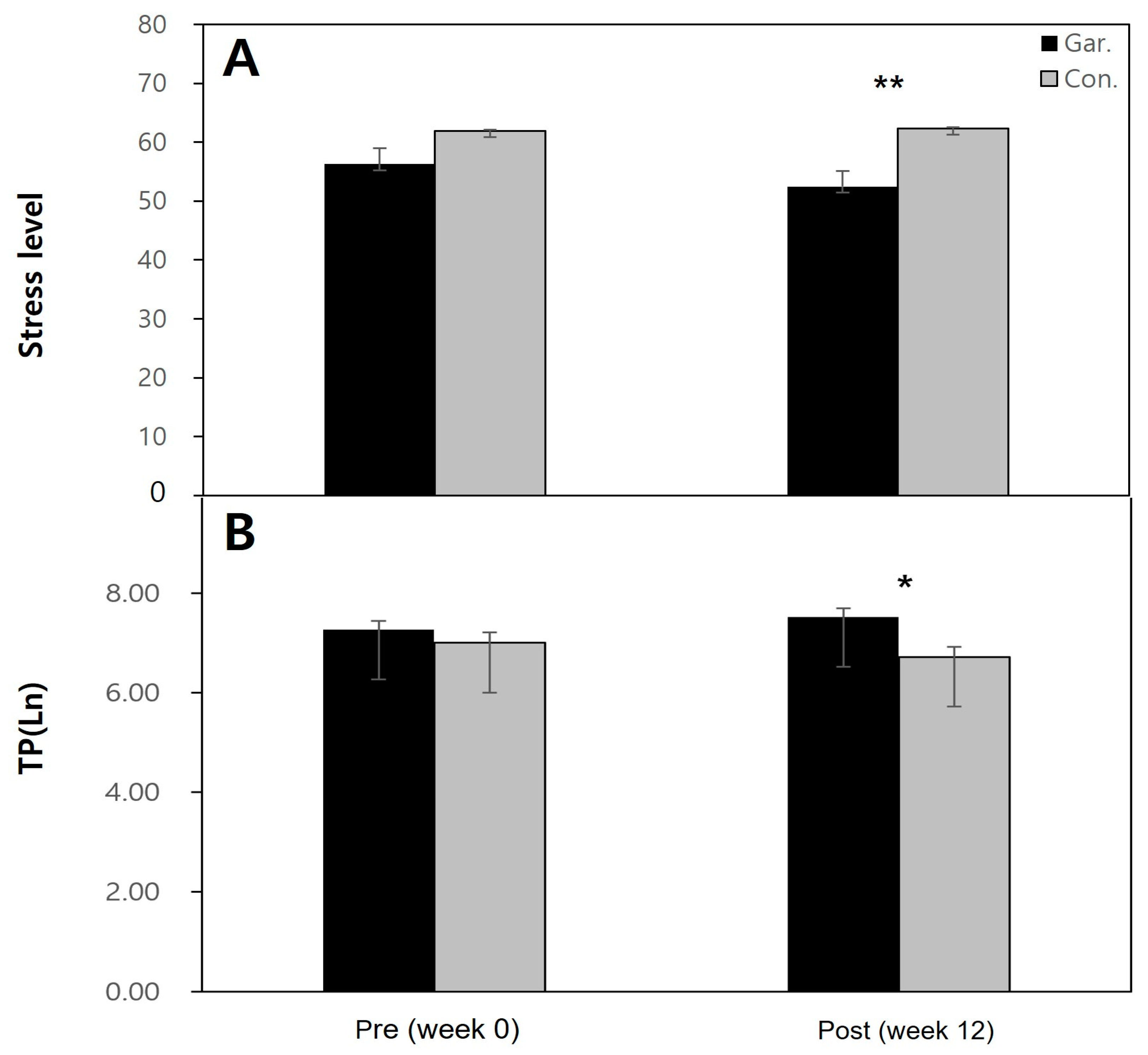

3.3. Changes After the Program in Gardening group and Control group

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Korea National Statistical Office. Available online: http://www.kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/index.action (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Kang, H.K.; Back. S.J.; Kim, J.H., The Impact of green activities on stress and depression in senior citizens. J. People Plants Environ. 2015, 18, 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J. The effects of aging anxiety on successful aging the elderly: Comparing elders living alone with ones not living alone. Korean Journal of Gerontological Social Welfare 2012, 57, 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R. S. Effects of gardens on health outcomes: Theory and research. Healing gardens: therapeutic benefits and design recommendation. Chapter In C. C. Marcus, And M. Barnes (Eds.); Whiley: New York, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.Y.; Lee, Y.C.; Lee, H.J.; Cho, W.K. Effect of horticultural therapy on physical activity and stress for elderly. J. People Plants Environ. Sym. Konkuk University, Seoul, 2016; 1, 191-192(Abstr).

- Lee, S.M.; Seo, H.S.; Yoon, H.K.; Jung, Y.B.; Hong, I.K.; Lee, S. The effect of horticultural therapy program based on basic psychological need theory using school garden for stress and school life satisfaction of middle school students. J. Korean Pract Arts Educ. 2020, 26, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, K.H. Stress of the korean aging adults. Korean J. Stress Res. 2007, 15, 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, K.P.; Song, S.H. A Study on the Relationship of Daily Stress and Social Support to Psychological Wellbeing in the Elderly. J. Korea Contents Association 2013, 13, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.O.; Seo, H.S.; Lee, S.J.; Koo, B.H. Effect of Garden Healing Activities on Stress Changes in the Elderly. J. Korea Institute of Garden Design 2021, 7, 323–334. [Google Scholar]

- Lipowski, Z. Psychosomatic Medicine and Liaison Psychiatry; Plenum Medical Book Co.: New York, USA, 1985; pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.K.; Kim, D.S. Relationship between Physiological Response and Salivary Cortisol Level to Life Stress. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2007, 26, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.J. The Effects of stressors and coping on depression of the oldest old. Health Soc Welfare Rev. 2014, 34, 264–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Park, J.S. Effects of a stress management program on perceived stress, depression, and somatic symptom in the elderly. J. Korean Academic Society of Home Health Care Nursing 2010, 17, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, S.H.; Jeon, S.H. A Study on the Planting Design Techniques of Healing Garden. The Korean Institute of Landscape Architecture Conference, Kyunghee University International Campus, Gyeonggi-do, 2016; 13-14.

- Rimmer, L. The clinical use of aromatherapy in the reduction of stress. Home Health Nurse 1998, 16, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, J. L. The use of aromatherapy in hospitalized children with HIV disease. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery 1997, 3, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psycho 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.Y.; Kim, J. S. Study review of horticultural therapy as a nursing intervention. Korean J Adu Nurs 2001, 13, 409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.A. Horticultural Therapy; Hakjisa: SEOUL, KOREA, 2003; pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.J.; Shon, K.H.; Kim, N.H. The effects of stress self-management education program on stress, coping and life satisfaction of community-based elderly. Asia-pacific J Multi Serv Conv Art Human Soc 2019, 9, 727–741. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.S.; Kim, K.S. Effects of Yoga Exercise Program on Response of Stress, Physical Fitness and Self-esteem in the Middle-aged Women. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing 2014, 26, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.O.; Bae, M.J. Effects of Music Therapy on Autonomous Nerve Balance of Human Body by Arirang Singing. J Naturopathy 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.G.; Jung, J.S. Relationship among Daily Stress, Perceived Health, and Successful Aging of Older People Participating in Physical Activity. Journal of Sport and Leisure Studies 2013, 54, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R. The Relationship among Regular Mass Sport Participation, Life Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction Expectancy. Korean Society for the Sociology of Sport 2009, 22, 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H. The Relationship between Life Satisfaction/Life Satisfaction Expectancy and Stress/Well-Being: An Application of Motivational States Theory. Korean Journal of Health Psychology 2007, 12, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S. A Study on Relationship of Stress and Immune Response – Focus on Cancer Patient′s Spouse Receving Chemotherapy -. Koren J Stress Res 1993, 1, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.H. Effects of Aromatherapy on Headache, Stress, and Immune Response of Students with Tension-Type Headache. JKASNE 2008, 14, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.S.; Gim, G.M.; Jeong, S.J.; Kim, J.S.; Ma, S.H. Community gardening activities and their effects on mental health of residents. J. People Plants Environ. 2019, 22, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.Y; Jung, H.J; Woo, M.J. Are Athletes with High Physical Anxiety More Vulnerable to Stress? Journal of Sport and Leisure Studies 2022, 90, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.J.; Koh, S.B.; Choi, H.R.; Woo, J.M.; Cha, B.S.; Park, J.K.; Chen, Y.H.; Chung, H.K. Job Stress, Heart Rate Variability and Metabolic Syndrome. AOEM 2004, 16, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.O.; Lee, J.H. The influence of in-classroom horticultural activities on the reduction of elementary school students aggression and stress J. Korean Pract Arts Educ 2009, 22, 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, D.G. Effect of Meditation Program on Stress Response Reduction of the Elderly. Journal of Korea Contents Association 2009, 9, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Yun, S.Y.; Lee, D.J. The Effects of Garden Activities on the Emotions of the Elderly. The Korean Society of Culture and Convergence 2023, 45, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The experience of nature: A psychological perspective Cambridge university press: Cambridge, England, 1989; pp. 150–174.

| Class | Topic | Garden Activities and Test for Stress |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | We met on the green | Program orientation and pre-test (u-bio) Introductions A tour of the garden |

| 2 | A budding seed in my heart | Fertilizing the garden / planting annuals A plant that resembles my heart |

| 3 | Herbs and Flowers | Planting herbs and edible flowers Showing off my pet plants |

| 4 | Beautiful, my life | Taking care of the garden and my heart Making a terrarium Week 4 u-bio test |

| 5 | A scented day | Walking in the herb garden My favorite scent / making herb soap |

| 6 | Forest is my friend | Forest meditation Taking care of the garden |

| 7 | Flavor and coolness | Cooking with herbs and edible flowers Sharing food |

| 8 | The growing number of green friends | Greenwood cutting Taking care of the garden Week 8 u-bio test |

| 9 | I’m a flower | Cutting flowers in the garden Arranging flowers / Showing my flowers |

| 10 | The pigments of flowers | Dyeing scarves with natural dyes Talking about my color |

| 11 | Mini my garden | Making a Succulent Garden Taking care of the garden |

| 12 | A heart-sharing garden | Taking care of the garden Creating a natural object frame Week 12 u-bio test |

| Demographics | Gardening N (%) |

Control N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 3(27.3) | 3(27.3) |

| Female | 8(72.7) | 8(72.7) | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 1(9.1) | 0(0.0) |

| Married | 10(90.9) | 11(100) | |

| Age | 60~69 | 8(72.7) | 6(54.5) |

| 70~79 | 3(27.3) | 5(45.5) | |

| 80~89 | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| Analysis | Gardening | Control | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Level | 56.26 ± 10.54 w | 61.87 ± 10.55 | -1.22 | 0.22 NS |

| TPz | 7.27 ± 0.74 | 7.01 ± 0.84 | -0.85 | 0.39 NS |

| SDNNy | 25.34 ± 10.74 | 22.22 ±10.06 | -0.69 | 0.49 NS |

| RMSSDx | 24.36 ± 19.74 | 17.93 ± 9.93 | -1.28 | 0.20 NS |

| Analysis | Pre (Week 0) | Week 4 | Week 8 | Post (week 12) | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M±SD | M±SD | M±SD | M±SD | |||

| Stress Level | 56.26±10.54w | 56.53±13.22 | 57.21±9.71 | 52.44±12.84 | 2.55 | 0.13 NS |

| TPz | 7.27±0.74 | 7.37±0.65 | 7.30±0.49 | 7.52±0.57 | 0.49 | 0.70 NS |

| SDNNy | 25.34±10.74 | 24.17±14.69 | 24.46±7.17 | 28.12±11.55 | 0.93 | 0.47 NS |

| RMSSDx | 24.36±19.74 | 20.46±14.34 | 23.20±10.54 | 25.70±15.63 | 1.09 | 0.41 NS |

| Analysis | Gardening | Control | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Level | 52.44±12.84 w | 65.28±6.92 | -2.66 | 0.008** |

| TPz | 7.52±0.57 | 6.72±0.66 | -2.30 | 0.022* |

| SDNNy | 28.12±11.54 | 22.01±8.94 | -1.02 | 0.31NS |

| RMSSDx | 25.70±15.63 | 19.60±12.37 | -1.28 | 0.20 NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).