Submitted:

18 January 2024

Posted:

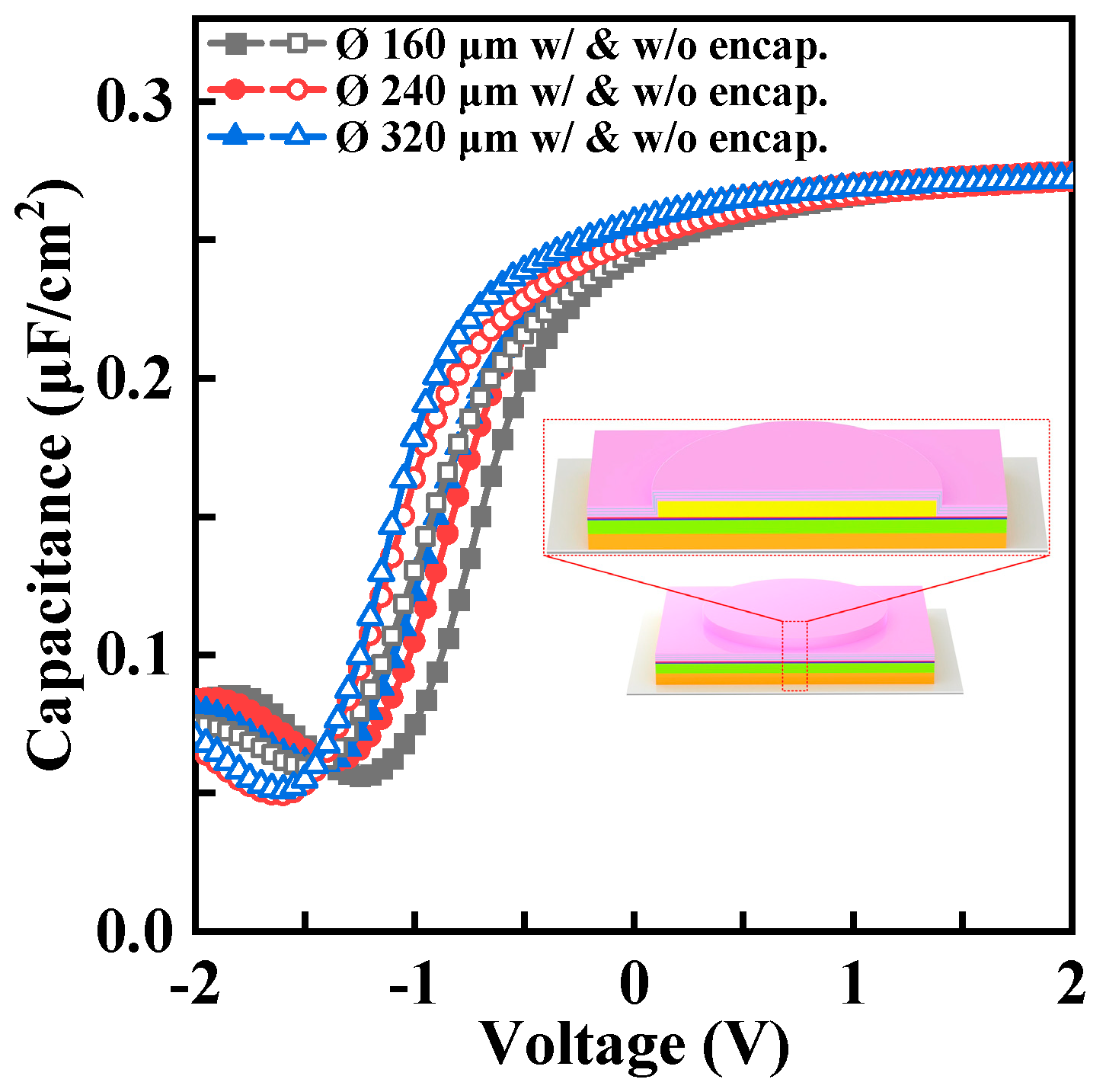

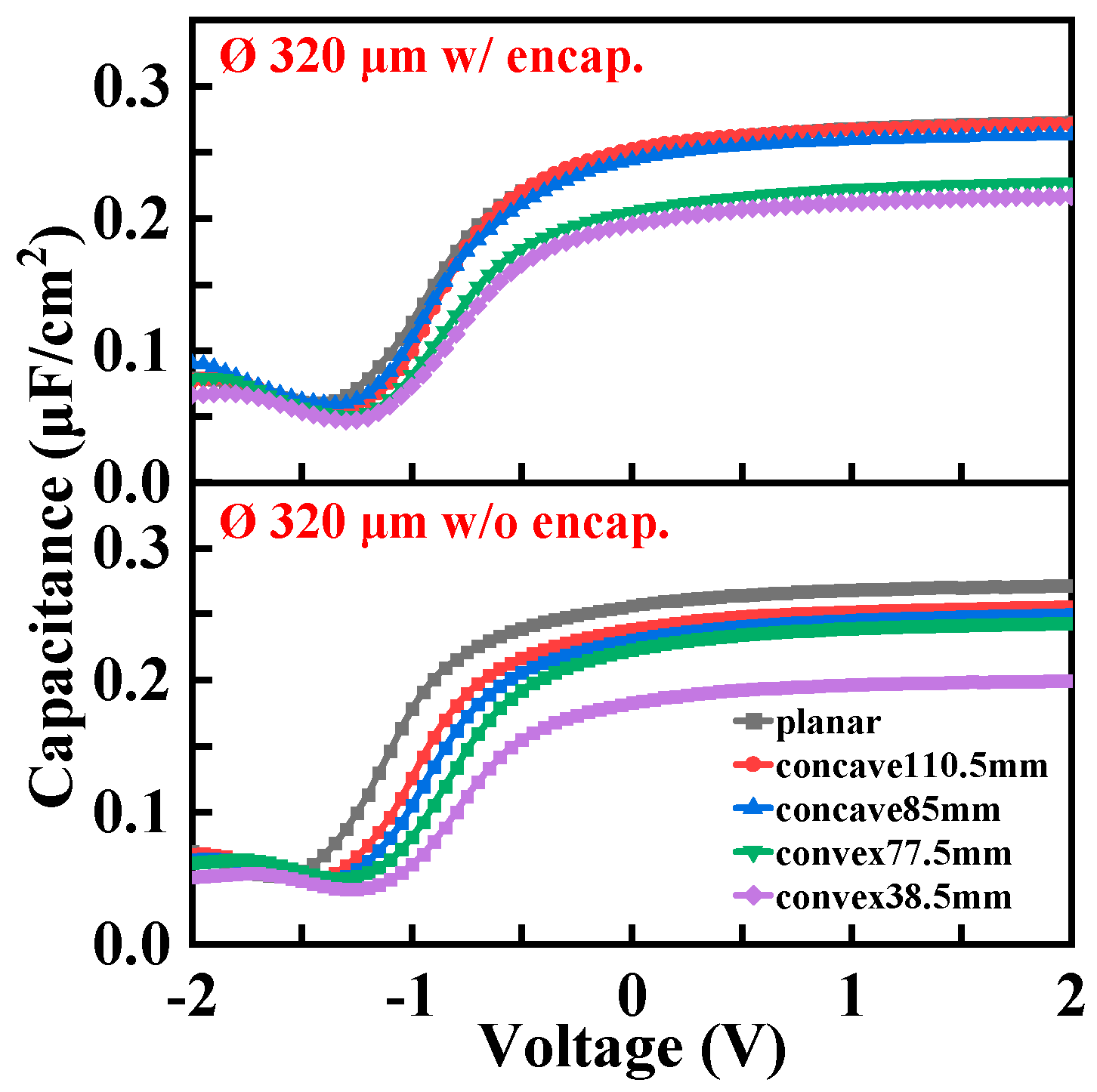

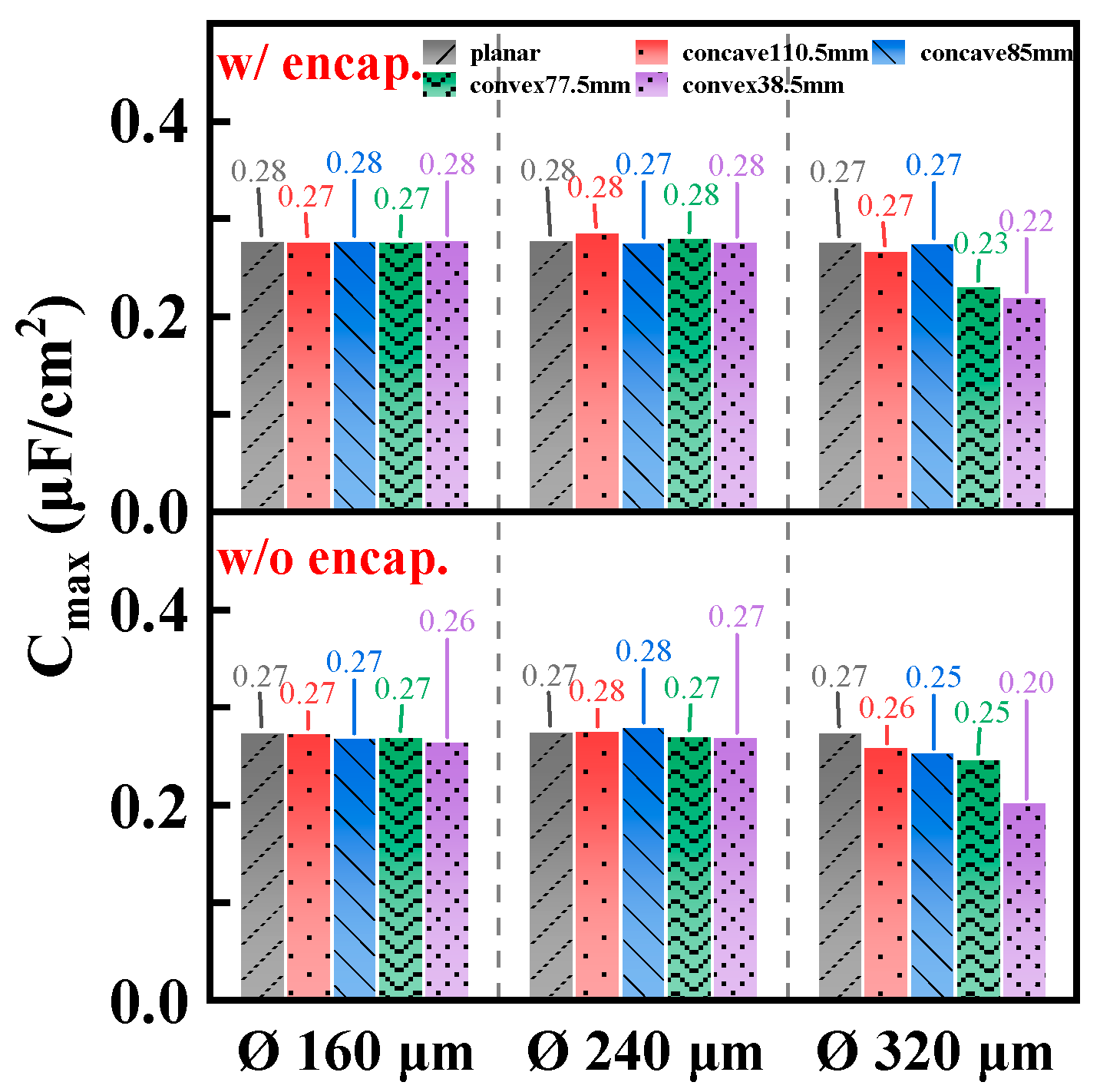

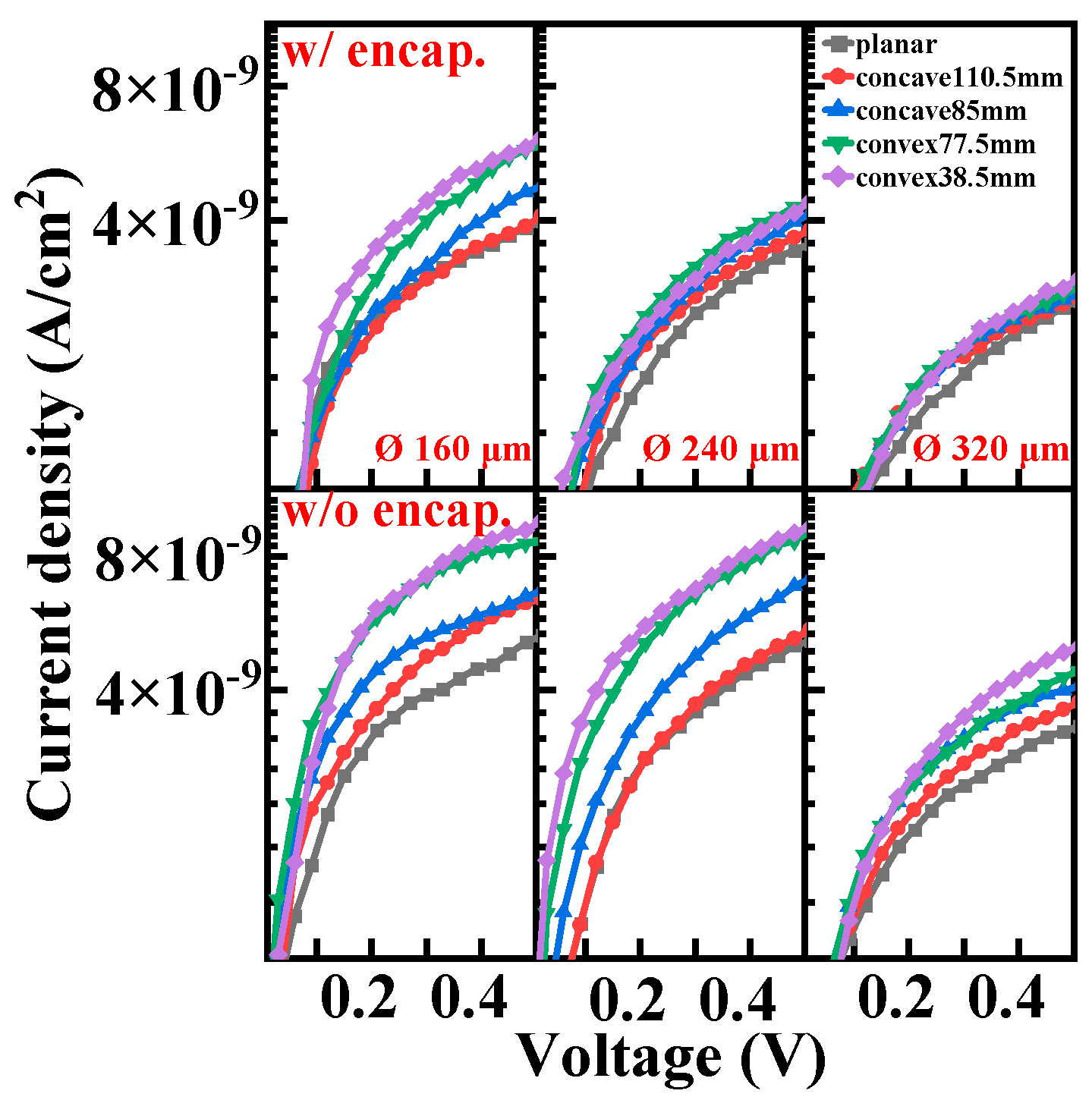

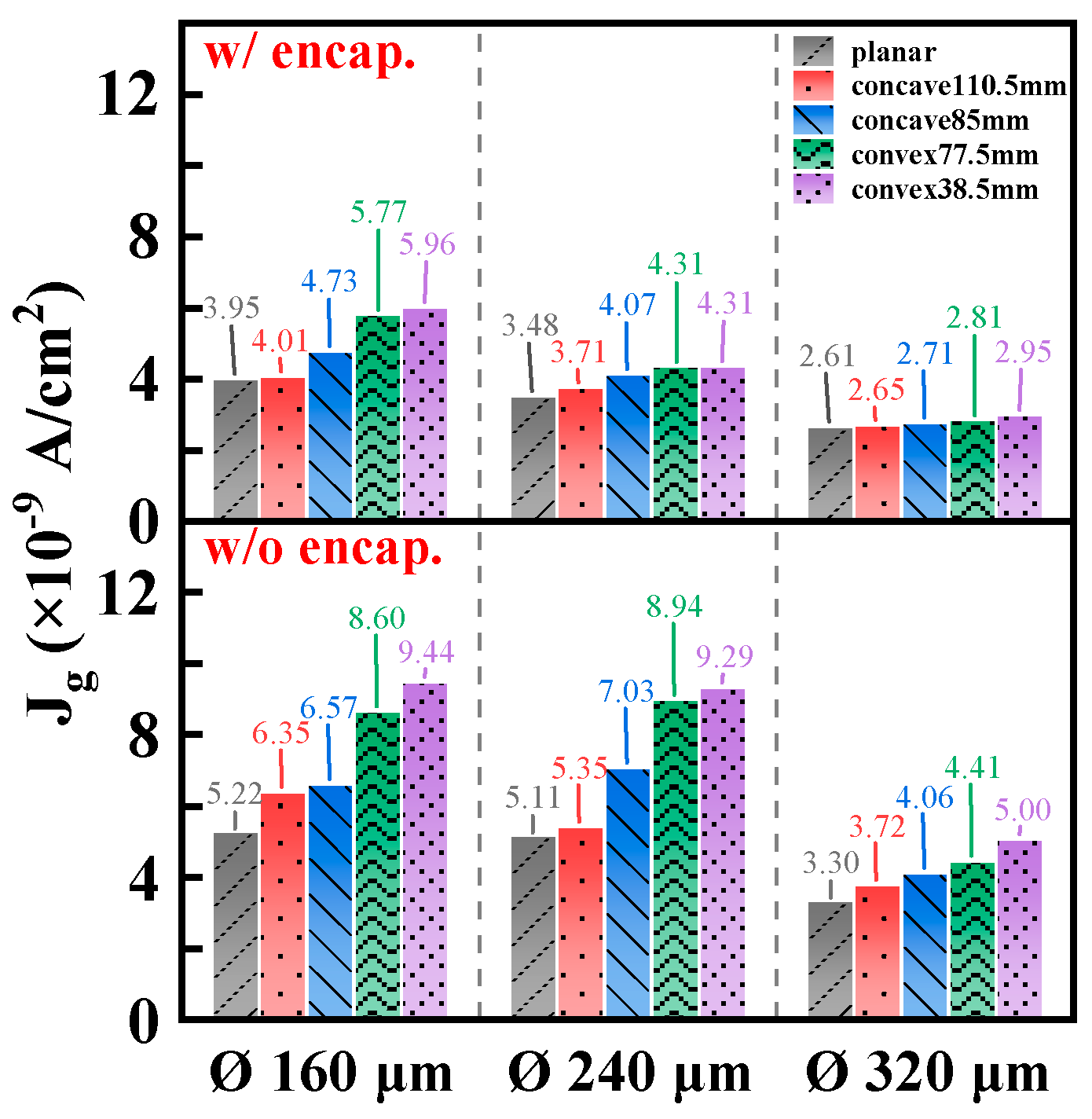

19 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

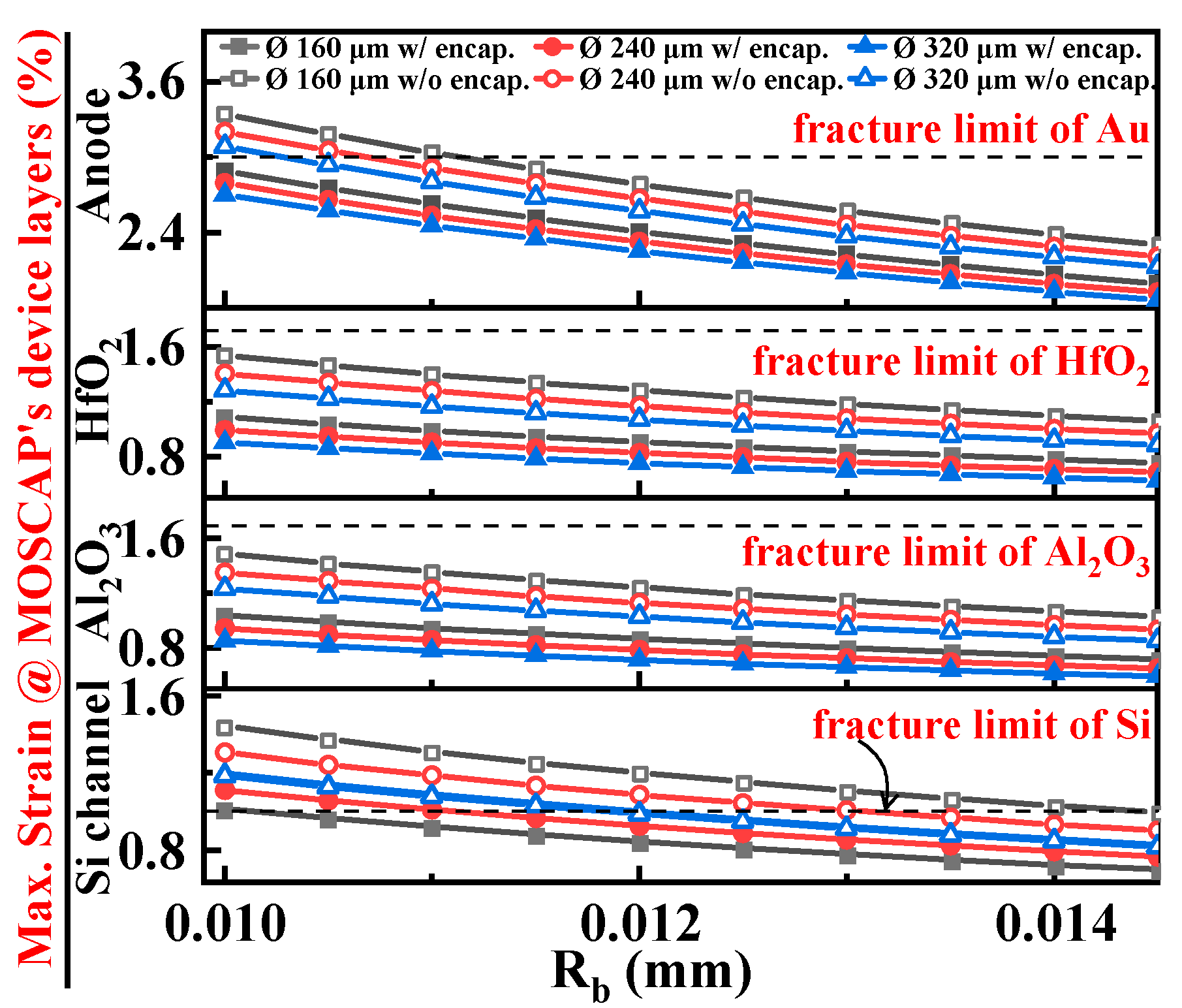

2. Maximum strain analysis in the device layer for Al2O3/alucone encapsulated and bare MOSCAPs with different Ø

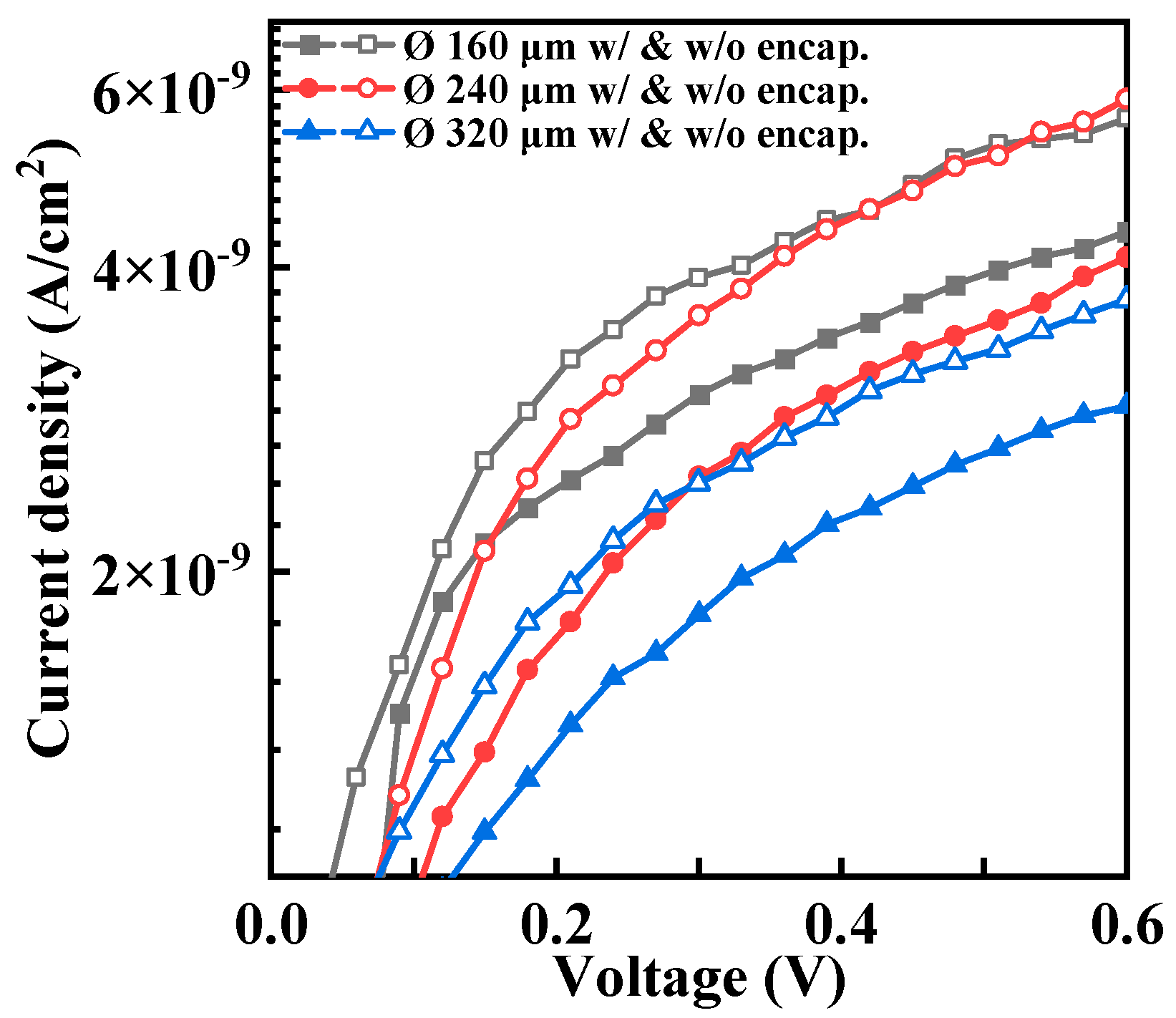

3. C-V and J-V characteristics at the planar state for encapsulated and bare MOSCAPs with different Ø

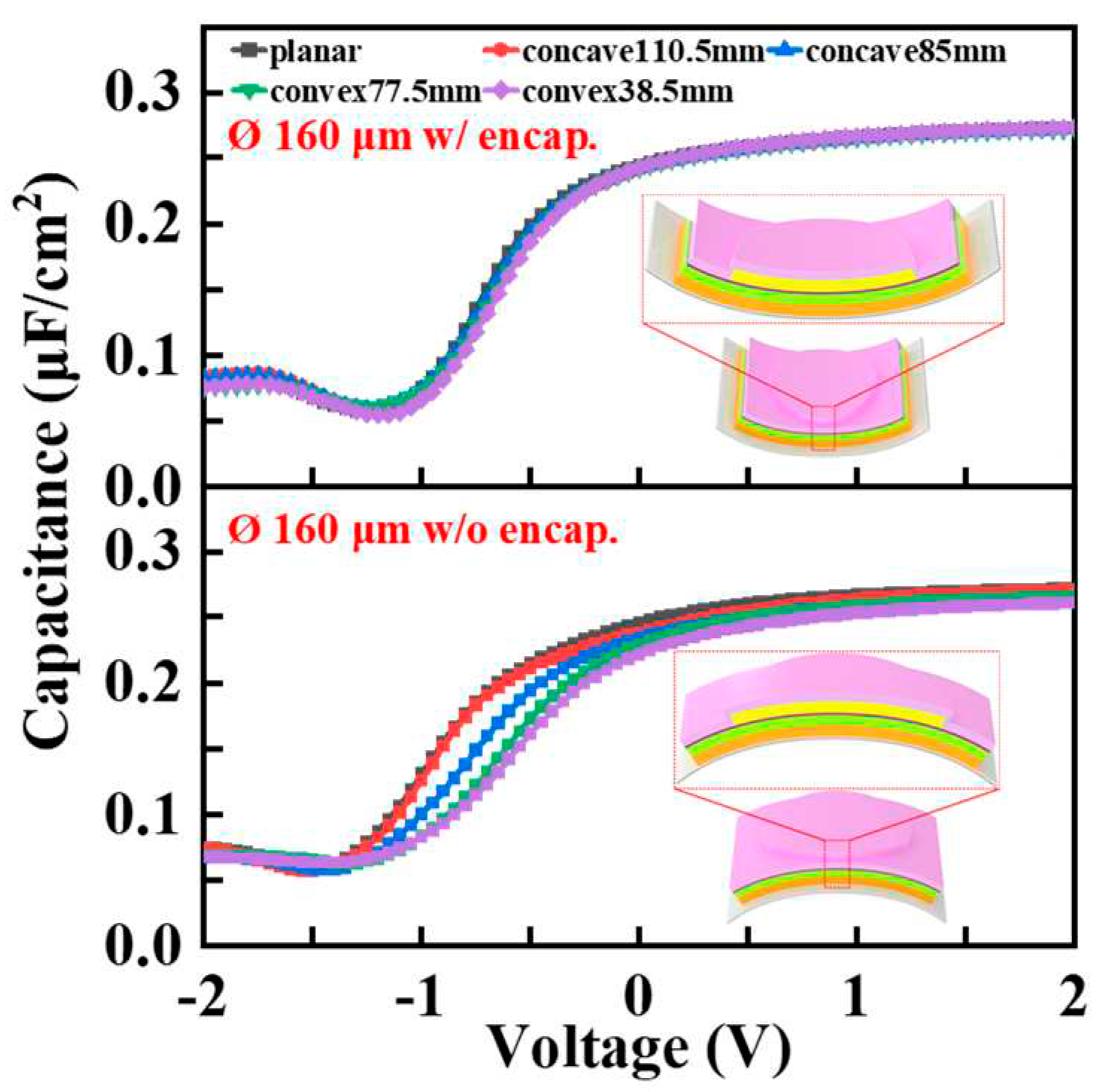

4. Electro-mechanical analysis under bending conditions for encapsulated and bare MOSCAPs with different Ø

4.1. Comparative analysis on basic electrical properties

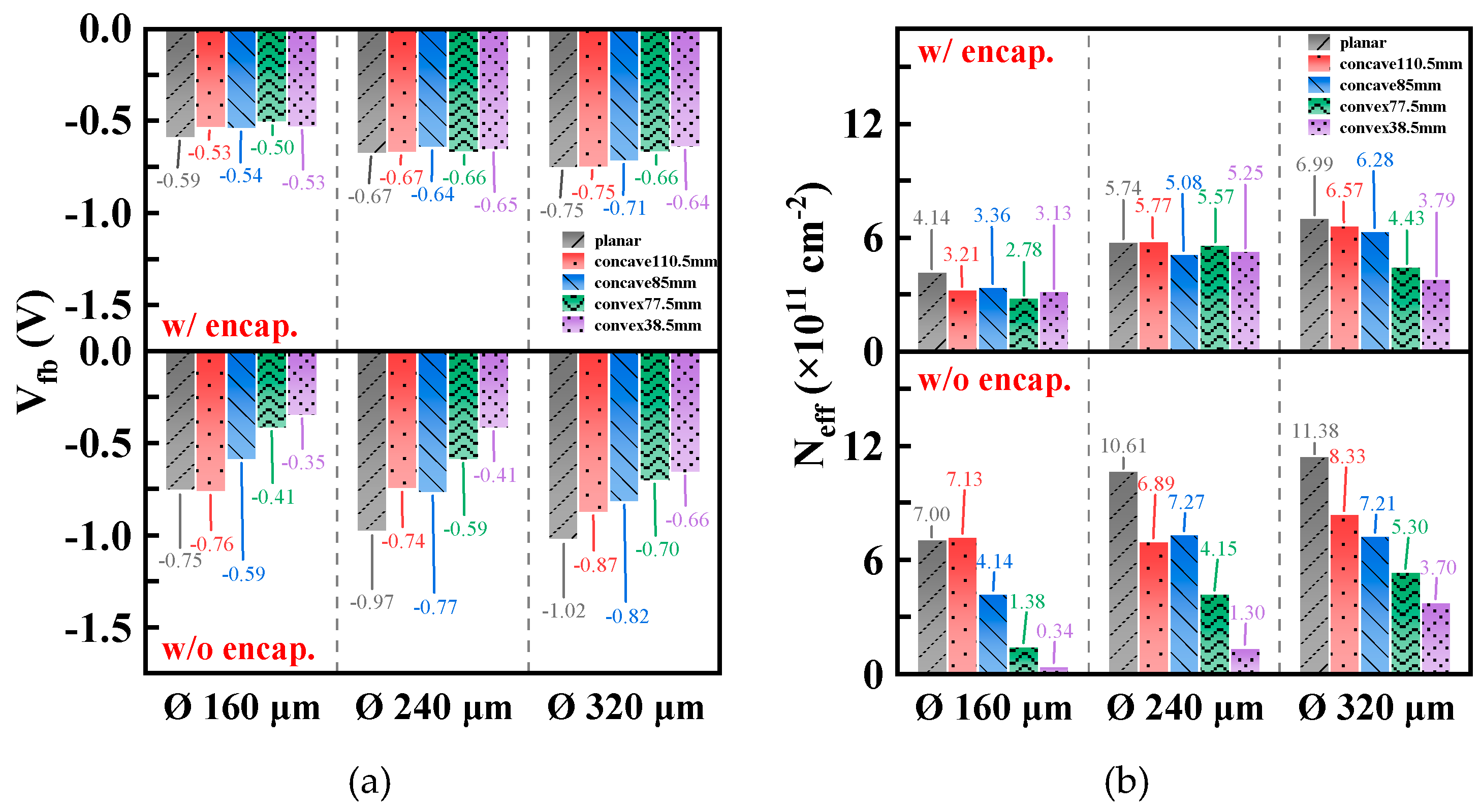

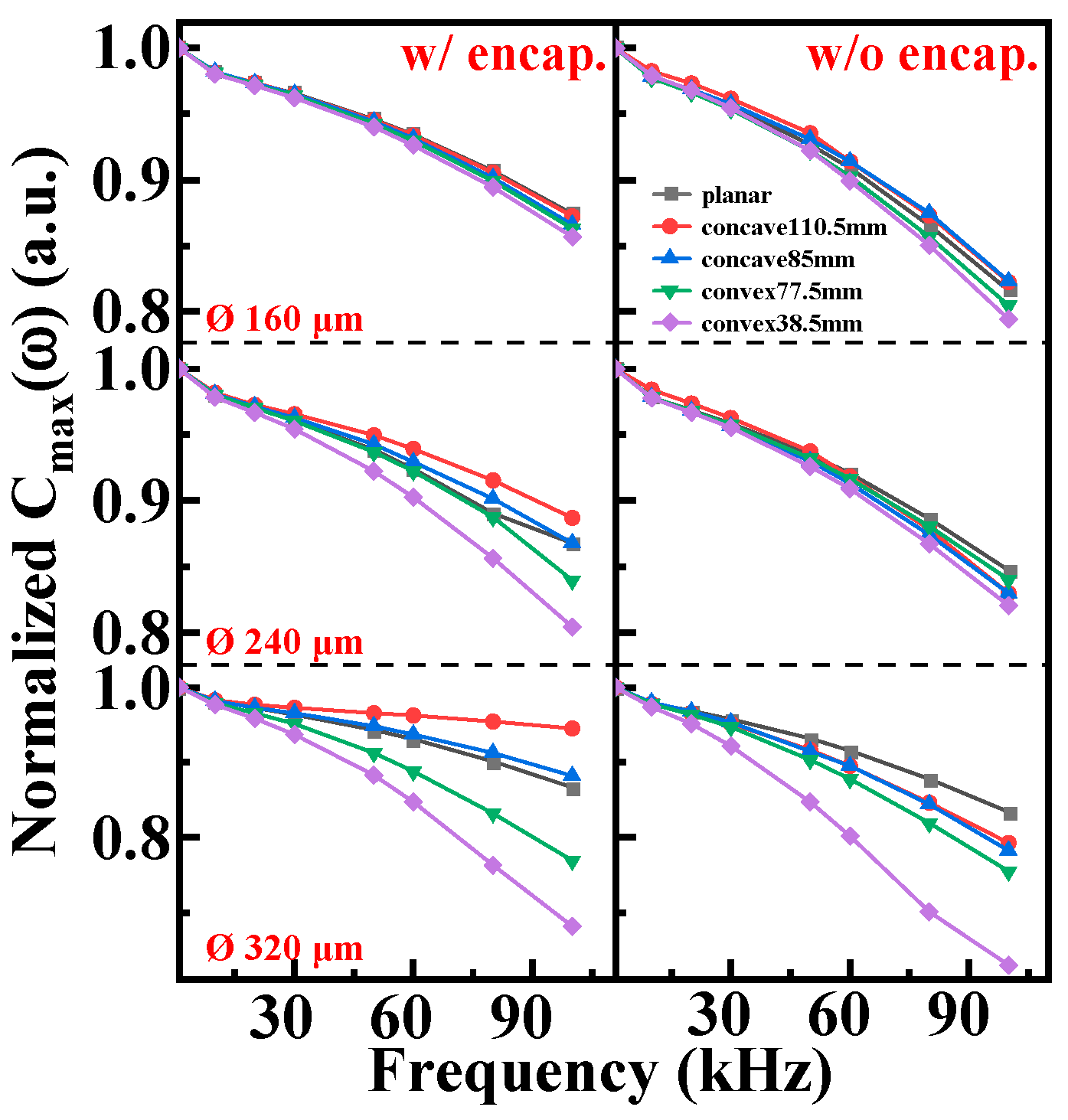

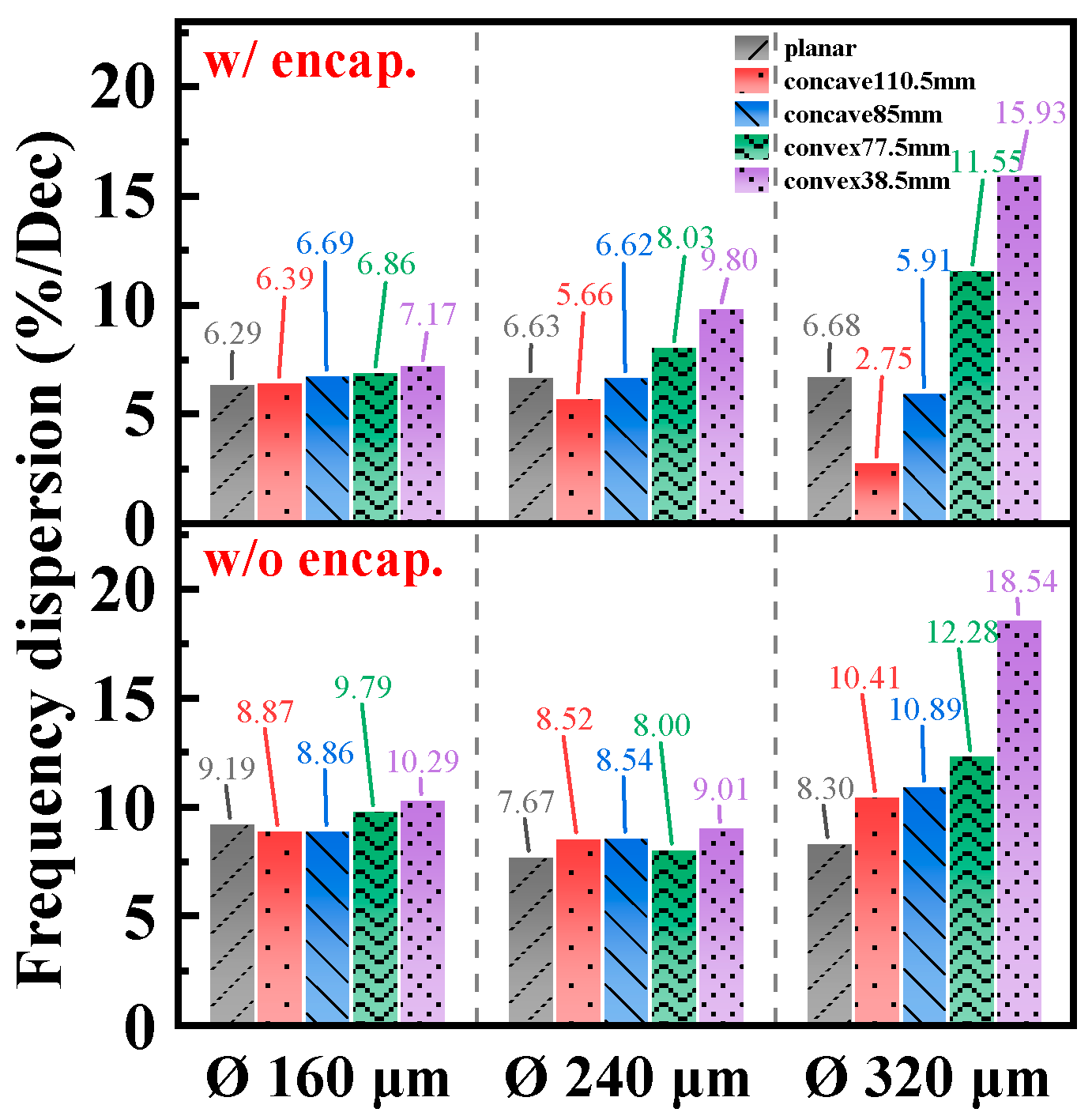

4.2. Comparative analysis on extracted parameters

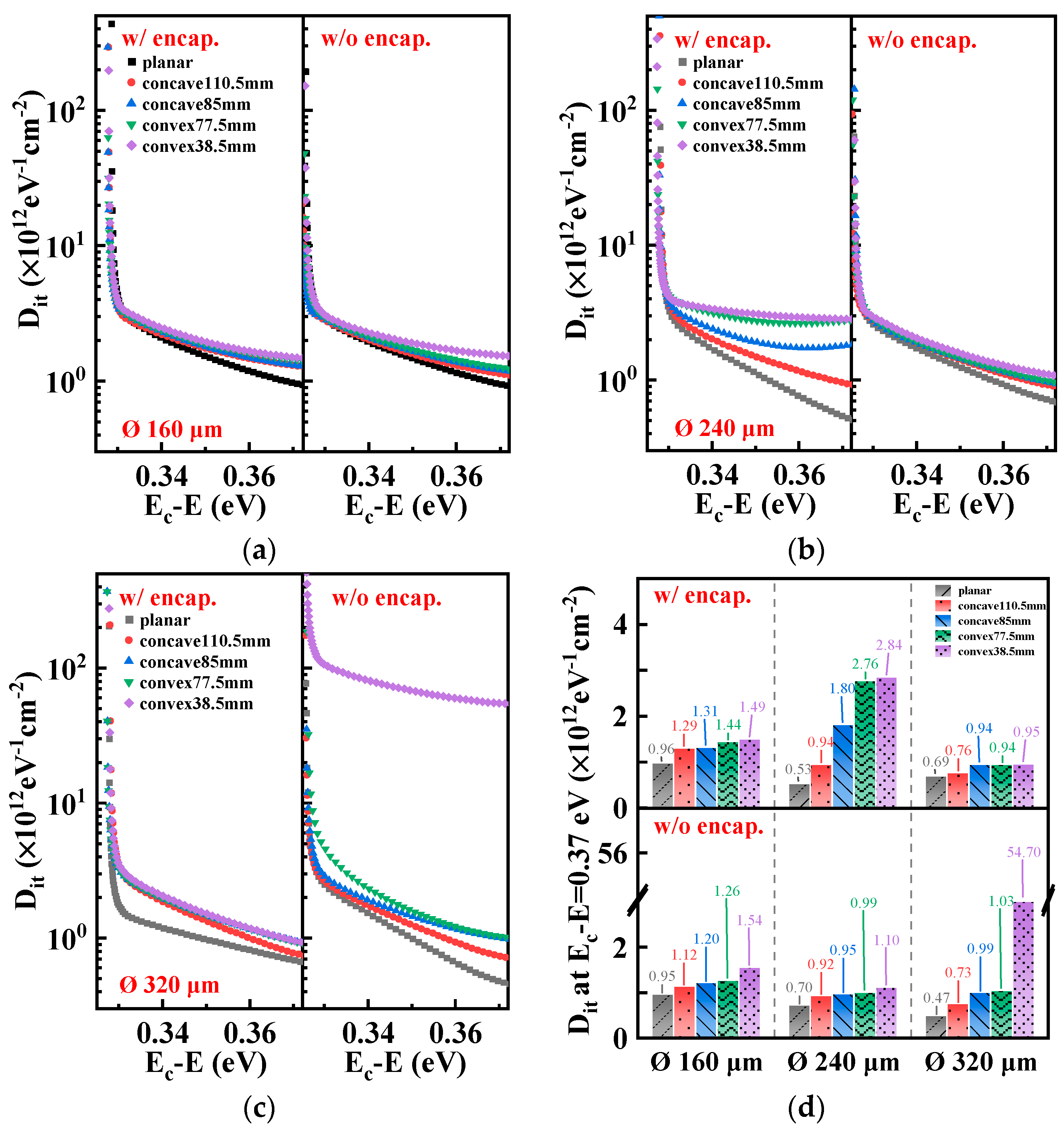

4.3. Comparative analysis on interfacial characteristics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

References

- Mariello, M.; Kim, K.; Wu, K.; Lacour, S.P.; Leterrier, Y. Recent advances in encapsulation of flexible bioelectronic implants: materials, technologies, and characterization methods. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2201129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.; Park, S.; Lee, J.; Yu, K.J. Emerging materials and technologies with applications in flexible neural implants: a comprehensive review of current issues with neural devices. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldroyd, P.; Malliaras, G.G. Achieving long-term stability of thin-film electrodes for neurostimulation. Acta Biomater. 2022, 139, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, S.; Pal, T. A comprehensive review of FET-based pH sensors: materials, fabrication technologies, and modeling. Electrochem. Sci. Adv. 2022, 2, e2100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khau, B.V.; Scholz, A.D.; Reichmanis, E. Advances and opportunities in development of deformable organic electrochemical transistors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 15067–15078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Shin, J.; Kim, K.; Ju, J.E.; Dutta, A.; Kim, T.S.; Cho, Y.U.; Kim, T.; Hu, L.; Min, W.K.; Jung, H.S.; Park, Y.S.; Won, S.M.; Yeo, W.H.; Moon, J.; Khang, D.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Ahn, J.H.; Cheng, H.; Yu, K.J.; Rogers, J.A. Ultrathin crystalline silicon nano and micro membranes with high areal density for low-cost flexible electronics. Small 2023, 19, 2302597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, K.J.; Hill, M.; Ryu, J.; Chiang, C.H.; Rachinskiy, I.; Qiang, Y.; Jang, D.; Trumpis, M.; Wang, C.; Viventi, J.; Fang, H. A soft, high-density neuroelectronic array. npj Flex. Electron. 2023, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Multia, J.; Karppinen, M. Atomic/Molecular layer deposition for designer’s functional metal–organic materials. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2200210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, J.P.; Rohbeck, N.; Michler, J.; Utke, I. Molecular layer deposited alucone thin films from long-chain organic precursors: from brittle to ductile mechanical characteristics. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 10832–10838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.; Li, J.; Won, S.M.; Bai, W.; Rogers, J.A. Materials for flexible bioelectronic systems as chronic neural interfaces. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 590–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Goncharova, L.V.; Zhang, Q.; Kaghazchi, P.; Sun, Q.; Lushington, A.; Wang, B.; Li, R.; Sun, X. Inorganic–organic coating via molecular layer deposition enables long life sodium metal anode. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 5653–5659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.C.; Jeong, E.G.; Kim, H.; Kwon, S.; Im, H.G.; Bae, B.S.; Choi, K.C. Reliable thin-film encapsulation of flexible OLEDs and enhancing their bending characteristics through mechanical analysis. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 40835–40843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Zhao, J.; Yu, K.J.; Song, E.; Farimani, A.B.; Chiang, C.H.; Jin, X.; Xue, Y.; Xu, D.; Du, W.; Seo, K.J.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, Z.; Won, S.M.; Fang, G.; Choi, S.W.; Chaudhuri, S.; Huang, Y.; Alam, M.A.; Viventi, J.; Aluru, N.R.; Rogers, J.A. Ultrathin, transferred layers of thermally grown silicon dioxide as biofluid barriers for biointegrated flexible electronic systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113, 11682–11687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Yu, K.J.; Gloschat, C.; Yang, Z.; Song, E.; Chiang, C.H.; Zhao, J.; Won, S.M.; Xu, S.; Trumpis, M.; Zhong, Y.; Han, S.W.; Xue, Y.; Xu, D.; Choi, S.W.; Cauwenberghs, G.; Kay, M.; Huang, Y.; Viventi, J.; Efimov, I.R.; Rogers, J.A. Capacitively coupled arrays of multiplexed flexible silicon transistors for long-term cardiac electrophysiology. Nat Biomed Eng. 2017, 1, 0038. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Hui, D.Y.; Zheng, C.; Yu, D.; Qiang, Y.Y.; Ping, C.; Xiang, C.L.; Yi, Z. A flexible transparent gas barrier film employing the method of mixing ALD/MLD-grown Al2O3 and alucone layers. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.; Qaiser, N.; Lee, C.; Matteini, P.; Yoo, S.J.; Kim, H. Effect of Al2O3/alucone nanolayered composite overcoating on reliability of Ag nanowire electrodes under bending fatigue. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 846, 156420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Bong, J.H.; Kim, C.; Hwang, W.S.; Kim, T.S.; Cho, B.J. Mechanical stability analysis via neutral mechanical plane for high-performance flexible Si nanomembrane FDSOI device. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 4, 1700618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Chen, R.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, H. Thin film encapsulation for the organic light-emitting diodes display via atomic layer deposition. J. Mater. Res. 2020, 35, 681–700. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, M. Analysis and design principles of MEMS devices, 1st ed; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2005; pp. 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lü, H.; Zhang, Y.M. Nanolaminated HfO2/Al2O3 dielectrics for high-performance silicon nanomembrane based field-effect transistors on biodegradable substrates. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2201477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.M.; Lü, H.L. Interfacial characteristics of Al/Al2O3/ZnO/n-GaAs MOS capacitor. Chinese Physics B 2013, 22, 076701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Allameh, S.; Nankivil, D.; Sethiaraj, S.; Otiti, T.; Soboyejo, W. Nanoindentation measurements of the mechanical properties of polycrystalline Au and Ag thin films on silicon substrates: Effects of grain size and film thickness. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 427, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.I.; Ahn, J.H.; Feng, X.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Rogers, J.A. Theoretical and experimental studies of bending of inorganic electronic materials on plastic substrates. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 2673–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.Y.; Yang, S.; Lee, J.; Tao, L.; Hwang, W.S.; Jena, D.; Lu, N.; Akinwande, D. High-performance, highly bendable MoS2 transistors with high-k dielectrics for flexible low-power systems. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 5446–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontu, V.; Nolvi, A.; Hokkanen, A.; Haeggström, E.; Kassamakov, I.; Franssila, S. Elastic and fracture properties of free-standing amorphous ALD Al2O3 thin films measured with bulge test. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 046411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdova, M.; Liu, X.; Wiemer, C.; Lamperti, A.; Tallarida, G.; Cianci, E.; Fanciulli, M.; Franssila, S. Hardness, elastic modulus, and wear resistance of hafnium oxide-based films grown by atomic layer deposition. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2016, 34, 051510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoho, M.; Tarasiuk, N.; Rohbeck, N.; Kapusta, C.; Michler, J.; Utke, I. Stability of mechanical properties of molecular layer–deposited alucone. Mater. Today Chem. 2018, 10, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).