Introduction

Brain Stimulation Reward (BSR) or Intracranial Self-Stimulation (ICSS) is a classical experimental paradigm used to study the neural substrates underlying reward processes and motivated behavior [1–3]. BSR is the pleasurable experience induced by direct stimulation of brain reward regions, while ICSS is an operant behavior producing BSR. This technique can be traced back to the 1950s when Olds and Milner introduced the concept that electrical stimulation of certain brain regions could induce pleasurable experiences in rats, giving birth to the intriguing realm of ICSS[4]. Over time, researchers identified key structures supporting this ICSS, including the lateral hypothalamus, the middle forebrain bundle (MFB), and the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in the midbrain [5–9].

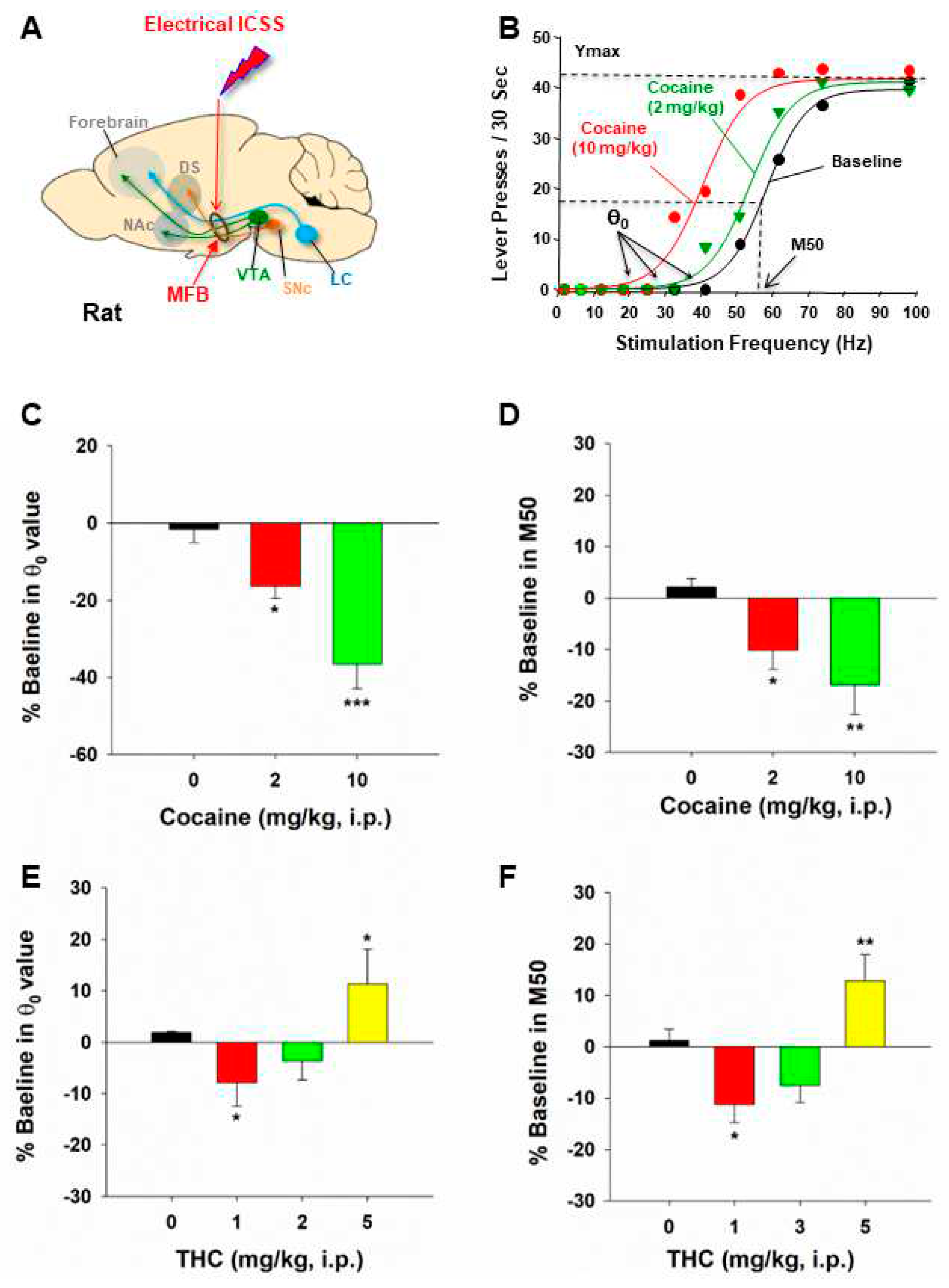

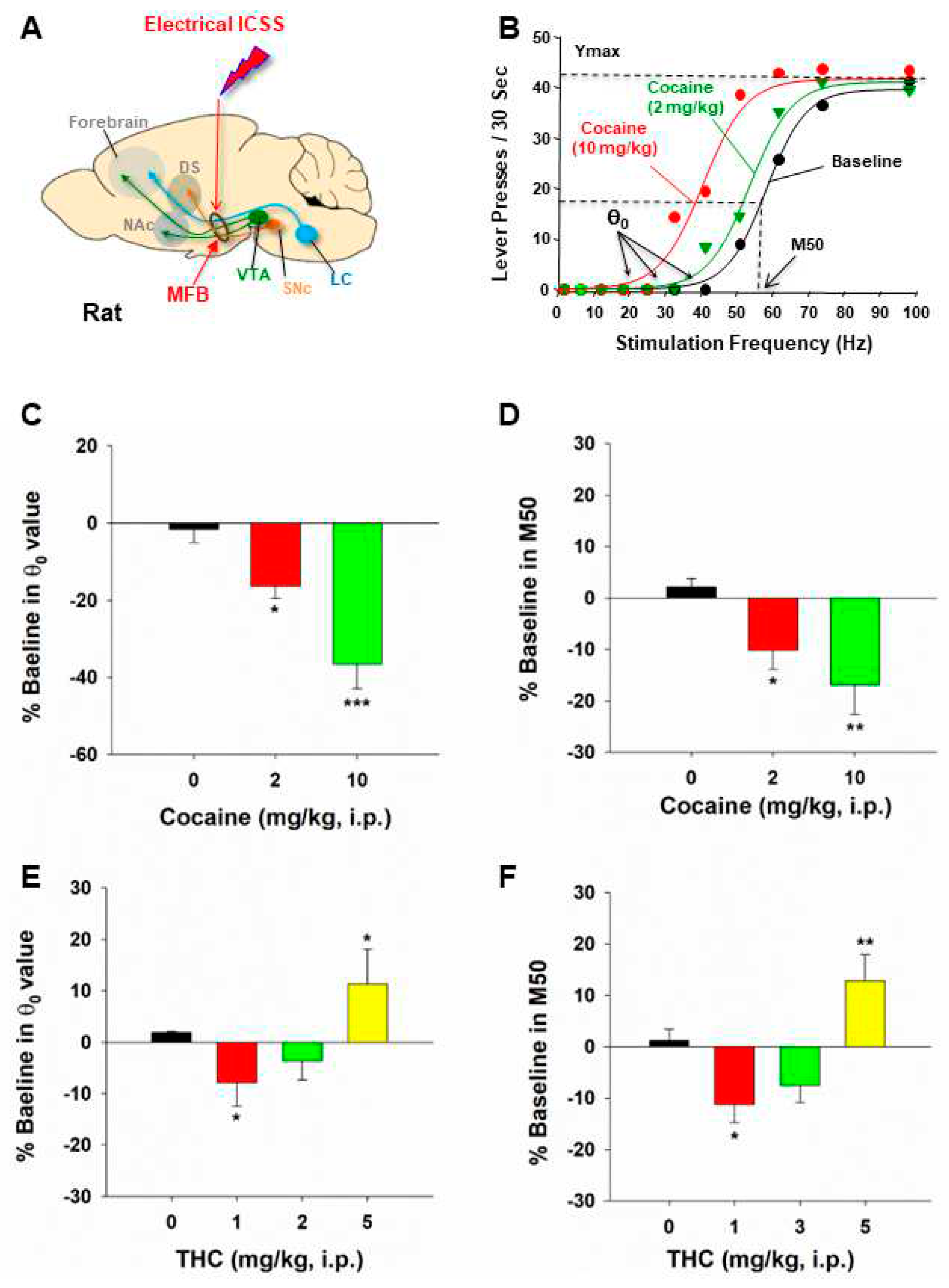

The ICSS procedure has since become a versatile tool with a multitude of applications. Firstly, it has been extensively utilized to dissect the neural substrates and circuits responsible for brain reward function[1,4,9]. In this procedure, subjects are given a condition to operantly respond to electrical stimulation of a specific brain region using a box with two levers or nose pokes – one active contingent to electrical stimulation and another being inactive without consequence upon responding. The number of active responses and the discrimination between active and inactive levers or nose pokes are crucial measures. If a subject makes more active responses to obtain stimulation, it suggests that the targeted brain region supports positive ICSS, indicating its involvement in positively reinforcing effects [5,7,10]. Thus, the ICSS procedures have provided a unique way to investigate the anatomical basis of brain reward function and motivated behavior. Secondly, ICSS has been extensively used to evaluate a drug’s rewarding or reward-attenuating effects [1,8,11,12]. Changes in the stimulation-response curve of ICSS are used to quantitatively measure drug-induced changes in BSR [5,13–15] (

Figure 1). Thirdly, the ICSS procedure has also been used to evaluate the abuse potential of new psychostimulant substances and the therapeutic potential of novel compounds for treating substance use disorders [1,9,14]. As many drugs of abuse enhance BSR in ICSS, the antagonism of novel compounds on addictive drug-enhanced BSR serves as a crucial indicator of therapeutic effects [15–18].

However, despite its broad implications, the lack of cell type specificity in electrical ICSS has been a significant drawback in studying neural mechanisms underlying brain reward processes and addiction [1,19,20]. As the MFB contains both ascending and descending fiber projections between the brainstem and the forebrain and the VTA contains multiple phenotypes of neurons [21–23], electrical stimulating the MFB or VTA results in the release of various transmitters from diverse cell types in multiple brain regions.

The recent development of optogenetics has provided a promising solution to this challenge. By introducing opsins, light-sensitive proteins, researchers can make genetically defined populations of cells light-sensitive [24,25]. This revolutionary technique allows us to selectively manipulate (activate or inactivate) specific types of neurons or their projection terminals to determine their role in reward processes and addiction [20,26,27]. For instance, stimulation of the mesolimbic DA system with optogenetics has confirmed the crucial role of DA or DA-related circuits in reward and motivation [23,28–30]. In addition to DA, optogenetic stimulation of glutamate or GABA neurons in distinct brain regions has also been shown to produce optical ICSS (oICSS) [30–34], supporting positive reinforcement effects. However, it is worth noting that most studies utilizing optogenetics have employed a single stimulation frequency or intensity to determine which types of neurons, when activated, are able to produce rewarding effects. oICSS has not been used to study drug effects on oICSS until 2017 when we first introduced the stimulation frequency-rate response curve of oICSS, akin to the one used in electrical ICSS (

Figure 1), to a study to determine how the drugs of abuse such as cocaine and cannabinoids differentially alter the brain reward function in transgenic VgluT2-Cre mice [13]. This innovative approach represents a significant step forward, as it allows us to quantitatively evaluate the effects of substances on oICSS, mirroring the established methods in electrical ICSS. In this minireview article, we first review the principle of the frequency-rate response of oICSS for studying drug reward and aversion. Subsequently, we review recent progress in studying the effects of drugs of abuse and other drugs on specific neurotransmitter-mediated oICSS. Lastly, we discuss the implications of this novel technique in future studies.

Principles of oICSS for studying drugs of abuse

The general experimental methods involve the introduction of opsins, light-sensitive proteins, into specific neurons or their projection terminals [24,25]. This genetic modification renders these populations of cells light-sensitive, allowing for precise control through optogenetic stimulation. The technique has been pivotal in studying cell type-specific neural mechanisms underlying brain reward function and motivation [28].

Traditionally, the rate-frequency curve-shift procedure has been a standard method in assessing drug effects in electrical ICSS. In this procedure, the effects of drugs of abuse on ICSS behavior are evaluated through parameters such as θ

0 (the minimally required stimulation frequency), Ymax (the maximal rate of lever response), and M50 (the stimulation frequency for half maximal reward efficacy) (

Figure 1B) [14,15,35,36]. Drugs of abuse, such as cocaine and amphetamine, cause a decrease in the stimulation threshold for electrical BSR and shift the stimulation–response curve leftward or upward immediately after acute administration. Similarly, systemic administration of GBR12935 (a selective DAT inhibitor) or SKF82958 (a DA D1R-like agonist) also produces a dose-dependent decrease in BSR threshold and a leftward or upward shift of the eICSS curve [1,8]. These findings suggest that cocaine, DAT inhibitors, or D1R agonists each potentiate the rewarding effects of ICSS. In contrast, withdrawal from chronic cocaine or nicotine administration is associated with depression-like effects and deficits in brain reward function, as assessed by BSR threshold elevation or a rightward shift of electrical ICSS [37,38]. Based on these findings, a well-accepted assumption is that if a test drug, such as cocaine, causes a decrease in θ

0 and M50 values or a leftward or upward shift of the stimulation–response curve, it indicates enhanced BSR and a summation between BSR and drug reward [1,14,19] (

Figure 1C,D). In contrast, if a drug, such as Δ

9-THC, produces an increase in θ

0 or M50 value or a rightward or downward shift in ICSS curve, it is often interpreted as producing reward-attenuation or aversive effects [1] (

Figure 1E,F).

Similarly, the adoption of this approach in oICSS studies, with a focus on a shift of the stimulation-rate response of oICSS, provides a quantitative framework for evaluating drug-induced changes in neurotransmitter-dependent oICSS. The same assumption is used in oICSS. If a drug, such as cocaine, also causes a leftward or upward shift of the stimulation-response curve, it indicates enhanced BSR. Conversely, if a drug, such as Δ9-THC, produces a rightward or downward shift in the oICSS curve, it indicates the drug producing reward-attenuation or aversive effects.

DA-dependent oICSS and its implications in studying drug reward versus aversion

Extensive research has focused on the functional roles of VTA DA neurons in reward processes. These neurons play distinct roles in both positive and negative reinforcement, resulting in preference and avoidance behaviors, respectively [20,28,39–41]. VTA DA neurons exhibit increased activity in response to both rewarding and aversive stimuli [41,42], suggesting physiological implications of these neurons in diverse and even conflicting environmental settings. Despite the complicated responses of DA neurons to seemingly conflicting cues, acute activation of these neurons leads to positive reinforcement and behavioral preference [28,29].

In 2011, Witten et al. first reported that selective optogenetic activation of VTA DA neurons in TH-Cre mice supported oICSS [43]. Subsequent research over the following decade has confirmed previous findings regarding the role of DA neurons in the VTA and substantia nigra (SN) in driving positive ICSS and reinforcement in rats and mice [44–47] (

Table 1,

Figure 2). However, projection-specific optogenetic manipulations indicated that VTA dopaminergic projections to sub-regions of the NAc may play different roles in reinforcement – VTA neurons that primarily project to the NAc core support positive oICSS, while a subpopulation of VTA neurons that project to the NAc shell do not [48], revealing previously unexpected complexities in neural pathways of reinforcement.

As stated above, the frequency-rate ICSS procedures have been used as a tool for testing drug abuse potential for decades. Several previous review articles have summarized the major findings of the effects of drugs of abuse on electrical ICSS [1,2,5,10,19]. Most previous studies observed the effects of acute drug administration on electrical ICSS [1,8]. For example, acute administration of cocaine or methamphetamine produced a dose-dependent leftward or upward shift in the frequency-rate curve [1]. In contrast, opioids produced mixed effects – highly addictive opioids such as morphine and fentanyl weakly facilitated ICSS at low doses; but, at higher doses, they produced initial ICSS depression followed later by ICSS facilitation [1,8]. Cannabinoids with CB1 and CB2 receptor agonist profiles produced little, biphasic, or depression of electrical ICSS in rats. An early study reported that THC facilitated ICSS in Lewis rats [49]. A later study from the same group found that THC facilitated ICSS in Lewis and Sprague-Dawley rats but not in Fischer 344 rats [50]. In contrast, other studies found that THC produced a dose-dependent biphasic effect – low doses facilitated, while high doses depressed ICSS in Sprague-Dawley or Long-Evans rats [14,51] or produced monophasic dose-dependent depression of ICSS in Sprague-Dawley rats [12,52]. Consistent with the latter finding, other cannabinoid agonists such as nabilone, levonantradol, CP55940, WIN55212-2, and HU210 produced only dose-dependent depression of ICSS in rats of various strains [11,52,53].

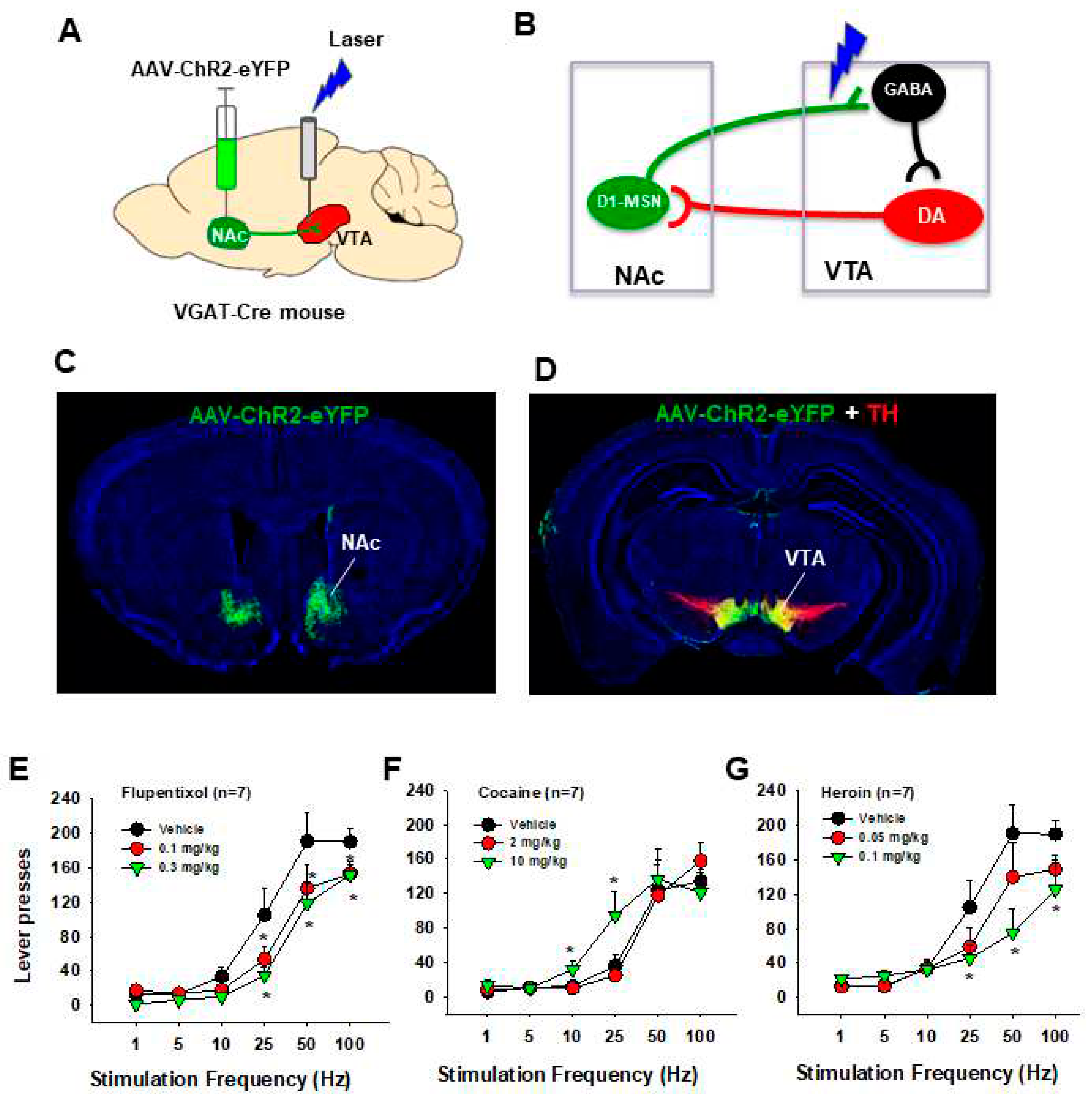

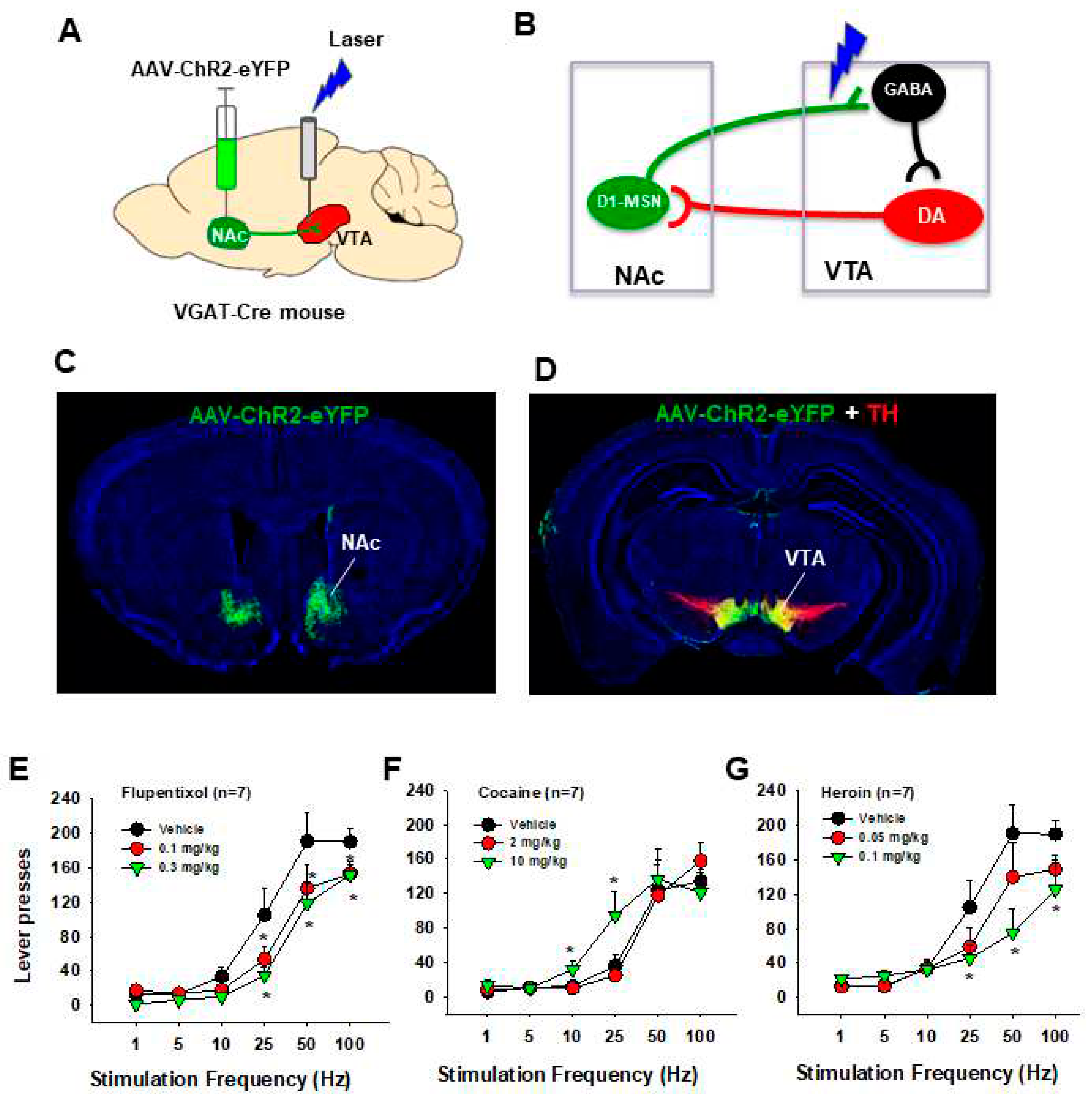

Utilizing the same frequency-rate response of oICSS, we investigated the impact of drugs of abuse on DA-dependent oICSS, yielding a series of novel findings. Acute administration of cocaine resulted in dose-dependent oICSS facilitation, evidenced by a leftward or upward shift and a reduction in M50 [18,44,45,54](

Figure 2). Similarly, opioids such as oxycodone demonstrated dose-dependent biphasic effects – low doses facilitated, while high doses inhibited oICSS in DAT-cre mice [55]. These findings align with observations in electrical ICSS in rats. Notably, the BSR-enhancing effects of cocaine were more potent at low electrical or optical stimulation frequencies, suggesting that cocaine-enhanced extracellular DA via blockade of the DA transporter (DAT) may exhibit additive or synergistic effects with DA neuron activation produced by low-frequency stimulation.

We also employed oICSS as a novel behavioral tool to assess the abuse potential of novel DAT inhibitors such as JJC8-088 and JJC8-091. JJC8-088 induced a cocaine-like upward or leftward shift in oICSS in DAT-cre mice, implying potential cocaine-like abuse [54]. In contrast, JJC8-091 prompted a contrary downward shift in oICSS, suggesting potential therapeutic anti-cocaine properties[54]. Indeed, results from a series of behavioral, neurochemical, and electrophysiological experiments substantiate the findings and conclusions observed in oICSS [54].

Furthermore, we utilized oICSS to investigate potential abuse or aversive effects of novel DA D3 receptor ligands on DA-dependent oICSS behavior. Novel D3 receptor ligands (±)VK4-40 (a D3 receptor antagonist), R-VK4-40 (also a D3 receptor antagonist), and S-VK4-40 (a D3 receptor partial agonist) induced mild depression in oICSS, while their pretreatment functionally counteracted cocaine- or oxycodone-enhanced oICSS [55–57]. These findings not only suggest an essential role of the D3 receptor in mediating DA-mediated oICSS through the blockade of D3 receptors or by competing with excess DA binding to D3 receptors caused by optical stimulation but also provide additional evidence supporting the utility of these D3 receptor ligands for treating substance use disorders, with a potential low abuse risk themselves.

Additionally, we extensively employed this behavioral model to investigate the functional role of cannabis or cannabinoids on DA-dependent behavior. Our findings revealed that systemic administration of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), WIN55,212-2, but not cannabidiol, dose-dependently decreased oICSS responding and shifted oICSS curves downward. Similarly, cannabinoid ligands that selectively activated CB1 (by ACEA), CB2 (by JWH133), or PPARγ (by pioglitazone) also induced dose-dependent reductions in oICSS [18,45,58]. Pretreatment with antagonists of CB1 (AM251, PIMSR), CB2 (AM630), or PPARα/γ (GW6471, GW9662) receptors dose-dependently blocked Δ9-THC-induced reduction in oICSS [18,58]. However, when examining various new synthetic cannabinoids in this behavioral model, we found that XLR-11 produced a cocaine-like enhancement, AM-2201 produced a Δ9-THC-like reduction, while 5F-AMB had no effect on oICSS responding [45]. Together, these findings from oICSS suggest that most cannabinoids are not rewarding or reward-enhancing but rather reward-attenuating or aversive in mice, and multiple cannabinoid receptor mechanisms underlie cannabinoid action in mesolimbic DA-dependent behavior. These findings not only confirm some previous findings with electrical ICSS but also expand our understanding of the role of DA in cannabinoid action.

This newly established behavioral model has also been instrumental in cannabis-based medication development for treating substance use disorders (

Table 2). In recent years, the cannabinoid CB2 receptor has emerged as a new target in medication development for the treatment of substance use disorders, as this receptor has been identified on midbrain DA neurons and implicated in drug reward and addiction [59–64]. Systemic administration of beta-caryophyllene (BCP), a plant-derived product with a CB2 receptor agonist profile and also an FDA-approved food additive, mildly depressed oICSS in DAT-cre mice [65–67]. Pretreatment with BCP dose-dependently inhibited oICSS-enhancing effects produced by cocaine, methamphetamine, and nicotine [65–67]. Although the neural mechanisms underlying BCP action in oICSS are not fully understood, the simplest explanation is that activation of CB2 receptors on DA neurons inhibits DA neuron activity, subsequently counteracting the DA-enhancing effects produced by optogenetic stimulation of DA neurons or drugs of abuse.

Glutamate-dependent oICSS and its application in studying drug reward and addiction

The VTA is well-known for regulating reward consumption, learning, memory, and addiction [23,68–71]. In addition to DA neurons, the VTA contains other types of neurons, including glutamate neurons and GABA neurons [23]. Unlike the well-studied functions of DA neurons, the role of VTA glutamate neurons is understudied. However, emerging studies have begun to reveal the importance of glutamate in regulating reward processes and addiction. In the brain, glutamate is synthesized from glutamine by glutaminase and then packaged into vesicles by vesicular glutamate transporters (VgluT) for its synaptic release [72]. Glutamate neurons in the VTA mainly express VgluT2 but not VgluT1 or VgluT3 [73,74]. VgluT2-expressing glutamate neurons are mostly located in the anterior and middle line of the VTA [44,73] and project to the NAc, ventral pallidum (VP), PFC, dorsal hippocampus (DH), and lateral habenula (LHb) [13,33,71,74,75] (

Figure 3).

Optical stimulation of VTA glutamate neurons is rewarding, as assessed by the increased firing of VTA DA neurons, supporting oICSS, and producing conditioned place preference and appetitive instrumental conditioning [13,32,33]. The rewarding effects of VTA glutamate neurons are suggested to be mediated via a local excitatory synapse connection between VTA glutamate and DA neurons [13,32]. This is further supported by our finding that pretreatment with DA D1 or D2 receptor antagonists attenuates oICSS maintained by optical stimulation of VTA glutamate neurons in VgluT2-Cre mice [13]. Additionally, optical activation of VTA glutamate neurons could also support oICSS in the absence of DA release [71], suggesting a DA-independent mechanism underlying glutamate-mediated reward. In contrast to reward, evidence also shows that optical stimulation of VTA glutamate neurons induces aversive escape behaviors [70], and optogenetic stimulation of VTA glutamatergic terminals in the NAc induces aversion [27,76].

The LHb is a brain region known for its function in conditioning aversion and reward [77,78]. Optogenetic activation of VTA glutamatergic terminals in the LHb elicits aversion and produces aversive conditioning [79]. These findings suggest that in addition to local glutamate projections within the VTA, VTA glutamate neurons also project to other brain regions and activation of distinct glutamate pathways may produce rewarding or aversive effects.

We have recently utilized glutamate-dependent oICSS to assess the rewarding versus aversive effects of drugs of abuse in VgluT2-Cre mice. Our findings indicate that systemic administration of cocaine caused a significant leftward shift of the rate-frequency curve of oICSS, suggesting a reward-enhancing effect [13]. This observation aligns with the results observed in DAT-cre mice [18,46,54]. As DA receptor antagonists significantly attenuated oICSS and shifted the rate-frequency curve to the right[13], it suggests that the oICSS produced by the activation of VTA glutamate neurons is at least partially mediated by the activation of VTA DA neurons. This DA-dependent mechanism may also explain how acute cocaine produces an enhancement in glutamate-mediated oICSS, as cocaine is an indirect DA enhancer through pharmacological blockade of DAT in the NAc.

We also employed this glutamate-dependent oICSS behavioral model to investigate the rewarding versus aversive effects of cannabinoids. Cannabis can elicit both rewarding and aversive responses in both humans and experimental animals. Cannabis reward is believed to be mediated by the activation of cannabinoid CB1 receptors on GABAergic neurons, leading to the disinhibition of VTA DA neurons [80,81]. However, there is a lack of direct behavioral evidence supporting this GABAergic hypothesis. To address this, we recently used RNAscope in situ hybridization assays to examine the cellular distribution of CB1 receptors in the brain. Our findings revealed that CB1 receptors are not only expressed on VTA GABAergic neurons but also on VTA VgluT2-positive glutamatergic neurons [13]. We then used Cre-Loxp transgenic technology to selectively delete CB1 receptors from glutamatergic neurons or GABAergic neurons. The results showed that systemic administration of Δ9-THC produced a dose-dependent conditioned place aversion and a reduction in glutamate-mediated oICSS in VgluT2-cre control mice, but not in glutamatergic CB1-KO mice [13]. These findings, for the first time, suggest that the activation of CB1 receptors expressed in VgluT2-positive glutamate neurons contributes to the aversive effects of cannabis or cannabinoids.

It is well-known that opioids are rewarding and produce analgesic effects. Opioid reward has been thought to be mediated through the inhibition of GABA transmission and subsequent disinhibition of DA neurons [82–84]. Recent studies indicate that mu opioid receptors are not only expressed in VTA GABA neurons but also in VTA glutamate neurons [46,85]. Optogenetic activation of VTA glutamate neurons resulted in excitatory currents recorded from VTA DA neurons that were reduced by presynaptic activation of the mu opioid receptor ex vivo [85]. In addition, opioid administration also directly inhibits glutamatergic transmission [86]. These findings suggest an important role of glutamate neurons in opioid effects. Opioids, such as morphine or oxycodone, have been shown to strengthen glutamatergic inputs to VTA DA neurons [85,87,88]. Furthermore, optically activating the VTA glutamate terminals in the dorsal hippocampus promotes opioid preference [76]. Together, growing evidence suggests that VTA glutamate neurons are also involved in opioid effects. oICSS may be used to study the functional role of glutamate neurons in opioid reward.

GABA-dependent oICSS and its application in studying drug abuse

VTA GABA neurons play a crucial role in modulating reward consumption, depression, stress, and sleep by forming local synapses onto DA neurons [46,89,90] or by sending GABAergic projections to other brain regions such as the NAc, PFC, central amygdala, and dorsal raphe nucleus [90–93]. While anatomical and electrophysiological data reveal that VTA GABA neurons form local synapses onto other VTA neurons [94,95], the inhibitory input from local GABA neurons is much weaker than long-range GABAergic inhibitory inputs from the RMTg and NAc [93,95]. Evidence has shown that disrupting local GABA release within the VTA causes major malfunctions in stress and anxiety modulation through a DA-dependent mechanism [89,90,96,97]. Optogenetic stimulation of VTA GABA neurons also induces conditioned place aversion [98] and disrupts cocaine and sucrose reward consummation [46,89]. As optogenetic stimulation of VTA GABA neurons directly suppressed the activity and excitability of neighboring DA neurons, as well as the release of DA in the NAc [89,98], it is suggested that the dynamic interplay between VTA DA and GABA neurons can control the initiation and termination of reward-related behaviors. However, direct optical activation of VTA GABA failed to alter heroin self-administration in Vgat-Cre mice [46], suggesting that VTA GABA interneurons may play a limited role in opioid reward.

In addition to VTA, the striatum consists of multiple types of neurons, including a large population (~95%) of GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs) and a smaller population of interneurons [99]. The MSNs are classified as D1-MSNs and D2-MSNs based on the expression of D1 or D2 receptors [100]. Interestingly, optogenetic stimulation of D1-MSNs within the dorsal striatum [101–103], NAc [104], or olfactory tubercle [105] is positively reinforcing, as assessed by real-time place preference or oICSS, while optogenetic stimulation of D2-MSNs within the dorsal striatum causes conditioned place aversion [101]. The reinforcing effects of D1-MSNs have been shown to be mediated through GABAergic projections from the dorsal striatum to the substantia nigra (SN) to the ventromedial motor thalamus [102]. Together, in vivo optogenetic experiments have demonstrated that optogenetic activation of GABA neurons across the striatum also supports positive oICSS.

To further understand how the activation of striatal GABAergic neurons produces positive oICSS, we injected AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP vectors into the NAc, and optical fibers were implanted into the VTA to stimulate D1-MSN GABAergic terminals in the VTA. We observed a robust oICSS response in a stimulation frequency-dependent manner in Vgat-Cre mice (

Figure 4A). As flupentixol, a DA receptor antagonist, was able to inhibit the oICSS, it is suggested that this positive oICSS could be mediated indirectly via a DA-dependent mechanism (

Figure 4B). We then used the standard rate-frequency response curve to observe the effects of drugs of abuse. We found that systemic administration of cocaine produced a significant enhancement in this GABA-dependent oICSS and shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the left (

Figure 4D). In contrast, systemic administration of heroin produced an opposite, dose-dependent reduction in the oICSS in Vgat-cre mice (

Figure 4C), suggesting that opioids may inhibit GABA-dependent oICSS behavior via mu opioid receptors expressed in NAc GABAergic neurons and their terminals. As both mu opioid receptors and CB1 receptors are highly expressed in striatal GABAergic neurons, this novel GABA-dependent oICSS behavioral model may further be used to identify the role of striatal GABAergic neurons and the their projection pathways in the rewarding effects of opioids and cannabinoids.

Advantages and limitations of oICSS

Intravenous drug self-administration, conditioned place preference (CPP) or aversion (CPA), and intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) are the most commonly used behavioral procedures to assess the rewarding effects of drugs of abuse [1]. In comparison to classical electrical ICSS, the oICSS procedure presents several advantages. First, the neurobiological basis of the behavior is clear [24,25]. The provided data demonstrate that optical activation of multiple phenotypes of neurons, including midbrain DA neurons and glutamate neurons, as well as NAc GABAergic D1-MSNs, produces rewarding effects. This not only confirms previous findings regarding the role of DA in reward and motivation but also reveals unexpected new findings indicating that multiple neurotransmitters and circuits underlie brain reward function. Second, light stimulation is relatively safer than electrical stimulation for in vivo experiments. Little evidence indicates that photostimulation (10–20 mW) of ChR2-expressing neurons leads to cell death [20]. Third, oICSS responding driven by optogenetic stimulation of a specific phenotype of neurons is more robust and stable over time than classical electrical ICSS. Mice quickly learn to lever press for oICSS, and once they have acquired the behavior, responding may last up to 5 months, whereas electrical ICSS behavior in rats usually lasts 1–2 months, based on our many years of experience. Lastly, oICSS appears to be more sensitive than electrical ICSS in detecting subtle changes in BSR and enables the testing of multiple drugs in the same subjects (with appropriate washout periods), with the added benefit of reducing animal numbers. Therefore, oICSS could be especially suitable for screening a large number of compounds for abuse potential.

The limitations of oICSS as a new behavioral model to evaluate drug rewarding versus aversive effects include the use of transgenic Cre-expressing mouse or rat lines, AAV vector microinjections, and transgenic opsin expression. The availability of transgenic animals may limit the use of oICSS, and the differences in opsin expression levels may impact the basal levels of oICSS behavior between studies, making original data comparisons between studies difficult [106]. In addition, stimulation threshold (θ0) and M50 values that are routinely used in electrical ICSS have not been used in oICSS to evaluate drug effects. In electrical ICSS, 16 different electrical pulse frequencies ranging from 141 to 25 Hz are used to generate a stimulation–response curve, allowing us to accurately calculate θ0 and M50 using best-fit mathematical algorithms as reported previously (Xi et al., 2006, 2008; Spiller et al., 2008, 2019). However, in oICSS, the currently available laser stimulators only allow us to generate six different laser pulse frequencies ranging from 1 to 100 Hz to establish a stimulation–response curve. Thus, more efforts are needed to optimize the oICSS procedure. We note that although ICSS procedures have been commonly used to examine drug’s abuse potential, these procedures have not been listed as standard drug screening tests in the field of drug abuse and addiction [107,108] or listed in the Guideline for Industry for assessing abuse potential of drugs by the FDA for regulatory purposes [109]. We live in an age of proliferating drug development that requires an expanding capability for abuse potential testing. This highlights the importance of improving predictive validity for oICSS as a viable tool in screening drug’s abuse potential in the future studies. Furthermore, optogenetic stimulation of nerve terminals may generate back-propagating action potentials, which can secondarily activate additional projections of a particular cell [110]. Thus, neurotransmitter release in other projection regions of a cell may complicate the data explanations. Lastly, a leftward or rightward shift of the rate-frequency response curve of electrical or optical ICSS may not necessarily mean rewarding (reward-enhancing) or aversive (reward-attenuating) as both rewarding and aversive stimuli may activate the mesolimbic DA system [111], suggesting that DA may play a similar role in both reward and aversion [40,47,98,112]. For example, it is well known that cannabis or cannabinoids are rewarding in some human subjects. However, in ICSS, the most used cannabinoids, such as Δ9-THC and WIN55,212-2, as well as synthetic cannabinoids such as AM-2201 and ACEA, all produced significant and dose-dependent reductions in electrical or optical ICSS [13,14,44,45], suggesting that they are aversive in mice. To address this discrepancy observed in humans and experimental animals, other behavioral models such as CPP and self-administration should be included in the study to fully address the abuse versus aversive potential of cannabinoids [1,52].

In summary, the evolution of ICSS from its inception in the 1950s to the integration of optogenetics in recent years represents a continuum of advancements that have significantly enriched our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying reward processes and addiction. The oICSS procedure has not only served as a tool to investigate the anatomical basis of brain reward function and motivated behavior but has also been crucial in evaluating the effects of drugs of abuse and new psychoactive substances. The recent integration of optogenetics has further refined our ability to selectively manipulate specific neural circuits, offering a more nuanced and precise understanding of the neural basis of reward and motivation. As research in this field continues to evolve, the combination of traditional ICSS methods and cutting-edge techniques such as optogenetics holds immense promise for unraveling the complexities of the brain's reward system and developing targeted interventions for substance use disorders.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA-IRP) within the National Institutes of Health (ZIA-DA000633 to Z.-X. Xi) and National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3304201 to R.S.) and the Excellent Scientist Fund (ZQJJ-2021–006 to R.S.)

References

- Negus, S. S.; Miller, L. L., Intracranial self-stimulation to evaluate abuse potential of drugs. Pharmacol Rev 2014, 66, (3), 869-917. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, E. L., Addiction and brain reward and antireward pathways. Adv Psychosom Med 2011, 30, 22-60. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, G.; Haines, E.; Shizgal, P., Potentiation of intracranial self-stimulation during prolonged subcutaneous infusion of cocaine. J Neurosci Methods 2008, 175, (1), 79-87. [CrossRef]

- Olds, J.; Milner, P., Positive reinforcement produced by electrical stimulation of septal area and other regions of rat brain. J Comp Physiol Psychol 1954, 47, (6), 419-27. [CrossRef]

- Wise, R. A., Addictive drugs and brain stimulation reward. Annu Rev Neurosci 1996, 19, 319-40. [CrossRef]

- Der-Avakian, A.; Markou, A., The neurobiology of anhedonia and other reward-related deficits. Trends Neurosci 2012, 35, (1), 68-77. [CrossRef]

- Carlezon, W. A., Jr.; Chartoff, E. H., Intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) in rodents to study the neurobiology of motivation. Nat Protoc 2007, 2, (11), 2987-95. [CrossRef]

- Negus, S. S.; Moerke, M. J., Determinants of opioid abuse potential: Insights using intracranial self-stimulation. Peptides 2019, 112, 23-31. [CrossRef]

- Stuber, G. D.; Wise, R. A., Lateral hypothalamic circuits for feeding and reward. Nat Neurosci 2016, 19, (2), 198-205. [CrossRef]

- Kornetsky, C.; Esposito, R. U.; McLean, S.; Jacobson, J. O., Intracranial self-stimulation thresholds: a model for the hedonic effects of drugs of abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979, 36, (3), 289-92. [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, S.; Nomikos, G. G.; Panagis, G., CB1 cannabinoid receptor agonists increase intracranial self-stimulation thresholds in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005, 179, (2), 498-508. [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, S.; Nomikos, G. G.; Stephens, D. N.; Panagis, G., Lack of evidence for appetitive effects of Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the intracranial self-stimulation and conditioned place preference procedures in rodents. Behav Pharmacol 2007, 18, (4), 311-9. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; He, Y.; Bi, G. H.; Zhang, H. Y.; Song, R.; Liu, Q. R.; Egan, J. M.; Gardner, E. L.; Li, J.; Xi, Z. X., CB1 Receptor Activation on VgluT2-Expressing Glutamatergic Neurons Underlies Delta(9)-Tetrahydrocannabinol (Delta(9)-THC)-Induced Aversive Effects in Mice. Sci Rep 2017, 7, (1), 12315. [CrossRef]

- Spiller, K. J.; Bi, G. H.; He, Y.; Galaj, E.; Gardner, E. L.; Xi, Z. X., Cannabinoid CB(1) and CB(2) receptor mechanisms underlie cannabis reward and aversion in rats. Br J Pharmacol 2019, 176, (9), 1268-1281. [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z. X.; Spiller, K.; Pak, A. C.; Gilbert, J.; Dillon, C.; Li, X.; Peng, X. Q.; Gardner, E. L., Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists attenuate cocaine's rewarding effects: experiments with self-administration and brain-stimulation reward in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008, 33, (7), 1735-45. [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z. X.; Newman, A. H.; Gilbert, J. G.; Pak, A. C.; Peng, X. Q.; Ashby, C. R., Jr.; Gitajn, L.; Gardner, E. L., The novel dopamine D3 receptor antagonist NGB 2904 inhibits cocaine's rewarding effects and cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, (7), 1393-405. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Madeo, G.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Hempel, B.; Liu, X.; Mu, L.; Liu, S.; Bi, G. H.; Galaj, E.; Zhang, H. Y.; Shen, H.; McDevitt, R. A.; Gardner, E. L.; Liu, Q. S.; Xi, Z. X., A red nucleus-VTA glutamate pathway underlies exercise reward and the therapeutic effect of exercise on cocaine use. Sci Adv 2022, 8, (35), eabo1440. [CrossRef]

- Galaj, E.; Hempel, B.; Moore, A.; Klein, B.; Bi, G. H.; Gardner, E. L.; Seltzman, H. H.; Xi, Z. X., Therapeutic potential of PIMSR, a novel CB1 receptor neutral antagonist, for cocaine use disorder: evidence from preclinical research. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, (1), 286. [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, S.; Markou, A., GABAB receptors in reward processes. Adv Pharmacol 2010, 58, 315-71. [CrossRef]

- Stuber, G. D.; Britt, J. P.; Bonci, A., Optogenetic modulation of neural circuits that underlie reward seeking. Biol Psychiatry 2012, 71, (12), 1061-7. [CrossRef]

- Ikemoto, S., Brain reward circuitry beyond the mesolimbic dopamine system: a neurobiological theory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010, 35, (2), 129-50. [CrossRef]

- Yeomans, J. S.; Mathur, A.; Tampakeras, M., Rewarding brain stimulation: role of tegmental cholinergic neurons that activate dopamine neurons. Behav Neurosci 1993, 107, (6), 1077-87. [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Margolis, E. B., Ventral tegmental area: cellular heterogeneity, connectivity and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18, (2), 73-85. [CrossRef]

- Boyden, E. S.; Zhang, F.; Bamberg, E.; Nagel, G.; Deisseroth, K., Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci 2005, 8, (9), 1263-8. [CrossRef]

- Deisseroth, K., Optogenetics: 10 years of microbial opsins in neuroscience. Nat Neurosci 2015, 18, (9), 1213-25. [CrossRef]

- Weidner, T. C.; Vincenz, D.; Brocka, M.; Tegtmeier, J.; Oelschlegel, A. M.; Ohl, F. W.; Goldschmidt, J.; Lippert, M. T., Matching stimulation paradigms resolve apparent differences between optogenetic and electrical VTA stimulation. Brain Stimul 2020, 13, (2), 363-371. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H. L.; Wang, H.; de Jesus Aceves Buendia, J.; Hoffman, A. F.; Lupica, C. R.; Seal, R. P.; Morales, M., A glutamatergic reward input from the dorsal raphe to ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5390. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H. C.; Zhang, F.; Adamantidis, A.; Stuber, G. D.; Bonci, A.; de Lecea, L.; Deisseroth, K., Phasic firing in dopaminergic neurons is sufficient for behavioral conditioning. Science 2009, 324, (5930), 1080-4. [CrossRef]

- Adamantidis, A. R.; Tsai, H. C.; Boutrel, B.; Zhang, F.; Stuber, G. D.; Budygin, E. A.; Tourino, C.; Bonci, A.; Deisseroth, K.; de Lecea, L., Optogenetic interrogation of dopaminergic modulation of the multiple phases of reward-seeking behavior. J Neurosci 2011, 31, (30), 10829-35. [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Fennell, A.; Stuber, G. D., Illuminating subcortical GABAergic and glutamatergic circuits for reward and aversion. Neuropharmacology 2021, 198, 108725. [CrossRef]

- Root, D. H.; Barker, D. J.; Estrin, D. J.; Miranda-Barrientos, J. A.; Liu, B.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H. L.; Vautier, F.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Kim, Y. S.; Fenno, L.; Deisseroth, K.; Morales, M., Distinct Signaling by Ventral Tegmental Area Glutamate, GABA, and Combinatorial Glutamate-GABA Neurons in Motivated Behavior. Cell Rep 2020, 32, (9), 108094. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. L.; Qi, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Morales, M., Rewarding Effects of Optical Stimulation of Ventral Tegmental Area Glutamatergic Neurons. J Neurosci 2015, 35, (48), 15948-54. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J. H.; Zell, V.; Gutierrez-Reed, N.; Wu, J.; Ressler, R.; Shenasa, M. A.; Johnson, A. B.; Fife, K. H.; Faget, L.; Hnasko, T. S., Ventral tegmental area glutamate neurons co-release GABA and promote positive reinforcement. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 13697. [CrossRef]

- Steidl, S.; Wang, H.; Ordonez, M.; Zhang, S.; Morales, M., Optogenetic excitation in the ventral tegmental area of glutamatergic or cholinergic inputs from the laterodorsal tegmental area drives reward. Eur J Neurosci 2017, 45, (4), 559-571. [CrossRef]

- Vorel, S. R.; Ashby, C. R., Jr.; Paul, M.; Liu, X.; Hayes, R.; Hagan, J. J.; Middlemiss, D. N.; Stemp, G.; Gardner, E. L., Dopamine D3 receptor antagonism inhibits cocaine-seeking and cocaine-enhanced brain reward in rats. J Neurosci 2002, 22, (21), 9595-603. [CrossRef]

- Spiller, K.; Xi, Z. X.; Peng, X. Q.; Newman, A. H.; Ashby, C. R., Jr.; Heidbreder, C.; Gaal, J.; Gardner, E. L., The selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonists SB-277011A and NGB 2904 and the putative partial D3 receptor agonist BP-897 attenuate methamphetamine-enhanced brain stimulation reward in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008, 196, (4), 533-42. [CrossRef]

- Stoker, A. K.; Markou, A., Withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration induces deficits in brain reward function in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res 2011, 223, (1), 176-81. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, P. J.; Markou, A., Neurobiology of the nicotine withdrawal syndrome. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2001, 70, (4), 531-49. [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. M.; Stuber, G. D., Optogenetic strategies to dissect the neural circuits that underlie reward and addiction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012, 2, (11). [CrossRef]

- Bromberg-Martin, E. S.; Matsumoto, M.; Hikosaka, O., Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuron 2010, 68, (5), 815-34. [CrossRef]

- Brischoux, F.; Chakraborty, S.; Brierley, D. I.; Ungless, M. A., Phasic excitation of dopamine neurons in ventral VTA by noxious stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, (12), 4894-9. [CrossRef]

- Salamone, J. D.; Correa, M., The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron 2012, 76, (3), 470-85. [CrossRef]

- Witten, I. B.; Steinberg, E. E.; Lee, S. Y.; Davidson, T. J.; Zalocusky, K. A.; Brodsky, M.; Yizhar, O.; Cho, S. L.; Gong, S.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Stuber, G. D.; Tye, K. M.; Janak, P. H.; Deisseroth, K., Recombinase-driver rat lines: tools, techniques, and optogenetic application to dopamine-mediated reinforcement. Neuron 2011, 72, (5), 721-33. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liang, Y.; Hempel, B.; Jordan, C. J.; Shen, H.; Bi, G. H.; Li, J.; Xi, Z. X., Cannabinoid CB1 Receptors Are Expressed in a Subset of Dopamine Neurons and Underlie Cannabinoid-Induced Aversion, Hypoactivity, and Anxiolytic Effects in Mice. J Neurosci 2023, 43, (3), 373-385. [CrossRef]

- Humburg, B. A.; Jordan, C. J.; Zhang, H. Y.; Shen, H.; Han, X.; Bi, G. H.; Hempel, B.; Galaj, E.; Baumann, M. H.; Xi, Z. X., Optogenetic brain-stimulation reward: A new procedure to re-evaluate the rewarding versus aversive effects of cannabinoids in dopamine transporter-Cre mice. Addict Biol 2021, 26, (4), e13005. [CrossRef]

- Galaj, E.; Han, X.; Shen, H.; Jordan, C. J.; He, Y.; Humburg, B.; Bi, G. H.; Xi, Z. X., Dissecting the Role of GABA Neurons in the VTA versus SNr in Opioid Reward. J Neurosci 2020, 40, (46), 8853-8869. [CrossRef]

- Ilango, A.; Kesner, A. J.; Keller, K. L.; Stuber, G. D.; Bonci, A.; Ikemoto, S., Similar roles of substantia nigra and ventral tegmental dopamine neurons in reward and aversion. J Neurosci 2014, 34, (3), 817-22. [CrossRef]

- Heymann, G.; Jo, Y. S.; Reichard, K. L.; McFarland, N.; Chavkin, C.; Palmiter, R. D.; Soden, M. E.; Zweifel, L. S., Synergy of Distinct Dopamine Projection Populations in Behavioral Reinforcement. Neuron 2020, 105, (5), 909-920 e5. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, E. L.; Paredes, W.; Smith, D.; Donner, A.; Milling, C.; Cohen, D.; Morrison, D., Facilitation of brain stimulation reward by delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988, 96, (1), 142-4. [CrossRef]

- Lepore, M.; Liu, X.; Savage, V.; Matalon, D.; Gardner, E. L., Genetic differences in delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced facilitation of brain stimulation reward as measured by a rate-frequency curve-shift electrical brain stimulation paradigm in three different rat strains. Life Sci 1996, 58, (25), PL365-72. [CrossRef]

- Katsidoni, V.; Kastellakis, A.; Panagis, G., Biphasic effects of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol on brain stimulation reward and motor activity. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2013, 16, (10), 2273-84. [CrossRef]

- Kwilasz, A. J.; Negus, S. S., Dissociable effects of the cannabinoid receptor agonists Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and CP55940 on pain-stimulated versus pain-depressed behavior in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012, 343, (2), 389-400. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J. C.; Hunt, G. E.; McGregor, I. S., Effects of the cannabinoid receptor agonist CP 55,940 and the cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR 141716 on intracranial self-stimulation in Lewis rats. Life Sci 2001, 70, (1), 97-108. [CrossRef]

- Newman, A. H.; Cao, J.; Keighron, J. D.; Jordan, C. J.; Bi, G. H.; Liang, Y.; Abramyan, A. M.; Avelar, A. J.; Tschumi, C. W.; Beckstead, M. J.; Shi, L.; Tanda, G.; Xi, Z. X., Translating the atypical dopamine uptake inhibitor hypothesis toward therapeutics for treatment of psychostimulant use disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, (8), 1435-1444. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C. J.; Humburg, B.; Rice, M.; Bi, G. H.; You, Z. B.; Shaik, A. B.; Cao, J.; Bonifazi, A.; Gadiano, A.; Rais, R.; Slusher, B.; Newman, A. H.; Xi, Z. X., The highly selective dopamine D(3)R antagonist, R-VK4-40 attenuates oxycodone reward and augments analgesia in rodents. Neuropharmacology 2019, 158, 107597. [CrossRef]

- Newman, A. H.; Ku, T.; Jordan, C. J.; Bonifazi, A.; Xi, Z. X., New Drugs, Old Targets: Tweaking the Dopamine System to Treat Psychostimulant Use Disorders. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2021, 61, 609-628. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C. J.; He, Y.; Bi, G. H.; You, Z. B.; Cao, J.; Xi, Z. X.; Newman, A. H., (+/-)VK4-40, a novel dopamine D(3) receptor partial agonist, attenuates cocaine reward and relapse in rodents. Br J Pharmacol 2020, 177, (20), 4796-4807. [CrossRef]

- Hempel, B.; Crissman, M.; Pari, S.; Klein, B.; Bi, G. H.; Alton, H.; Xi, Z. X., PPARalpha and PPARgamma are expressed in midbrain dopamine neurons and modulate dopamine- and cannabinoid-mediated behavior in mice. Mol Psychiatry 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z. X.; Peng, X. Q.; Li, X.; Song, R.; Zhang, H. Y.; Liu, Q. R.; Yang, H. J.; Bi, G. H.; Li, J.; Gardner, E. L., Brain cannabinoid CB(2) receptors modulate cocaine's actions in mice. Nat Neurosci 2011, 14, (9), 1160-6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Y.; Gao, M.; Liu, Q. R.; Bi, G. H.; Li, X.; Yang, H. J.; Gardner, E. L.; Wu, J.; Xi, Z. X., Cannabinoid CB2 receptors modulate midbrain dopamine neuronal activity and dopamine-related behavior in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, (46), E5007-15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Y.; Gao, M.; Shen, H.; Bi, G. H.; Yang, H. J.; Liu, Q. R.; Wu, J.; Gardner, E. L.; Bonci, A.; Xi, Z. X., Expression of functional cannabinoid CB(2) receptor in VTA dopamine neurons in rats. Addict Biol 2017, 22, (3), 752-765. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C. J.; Xi, Z. X., Progress in brain cannabinoid CB(2) receptor research: From genes to behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019, 98, 208-220. [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, F.; Garcia-Gutierrez, M. S.; Manzanares, J., Pharmacological regulation of cannabinoid CB2 receptor modulates the reinforcing and motivational actions of ethanol. Biochem Pharmacol 2018, 157, 227-234. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. R.; Canseco-Alba, A.; Zhang, H. Y.; Tagliaferro, P.; Chung, M.; Dennis, E.; Sanabria, B.; Schanz, N.; Escosteguy-Neto, J. C.; Ishiguro, H.; Lin, Z.; Sgro, S.; Leonard, C. M.; Santos-Junior, J. G.; Gardner, E. L.; Egan, J. M.; Lee, J. W.; Xi, Z. X.; Onaivi, E. S., Cannabinoid type 2 receptors in dopamine neurons inhibits psychomotor behaviors, alters anxiety, depression and alcohol preference. Sci Rep 2017, 7, (1), 17410. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Galaj, E.; Bi, G. H.; Wang, X. F.; Gardner, E.; Xi, Z. X., beta-Caryophyllene, a dietary terpenoid, inhibits nicotine taking and nicotine seeking in rodents. Br J Pharmacol 2020, 177, (9), 2058-2072. [CrossRef]

- He, X. H.; Galaj, E.; Bi, G. H.; He, Y.; Hempel, B.; Wang, Y. L.; Gardner, E. L.; Xi, Z. X., beta-caryophyllene, an FDA-Approved Food Additive, Inhibits Methamphetamine-Taking and Methamphetamine-Seeking Behaviors Possibly via CB2 and Non-CB2 Receptor Mechanisms. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 722476. [CrossRef]

- Galaj, E.; Bi, G. H.; Moore, A.; Chen, K.; He, Y.; Gardner, E.; Xi, Z. X., Beta-caryophyllene inhibits cocaine addiction-related behavior by activation of PPARalpha and PPARgamma: repurposing a FDA-approved food additive for cocaine use disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 46, (4), 860-870. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Tong, Q., Anatomy and Function of Ventral Tegmental Area Glutamate Neurons. Front Neural Circuits 2022, 16, 867053. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ishikawa, M.; Wang, J.; Schluter, O. M.; Sesack, S. R.; Dong, Y., Ventral Tegmental Area Projection Regulates Glutamatergic Transmission in Nucleus Accumbens. Sci Rep 2019, 9, (1), 18451. [CrossRef]

- Barbano, M. F.; Wang, H. L.; Zhang, S.; Miranda-Barrientos, J.; Estrin, D. J.; Figueroa-Gonzalez, A.; Liu, B.; Barker, D. J.; Morales, M., VTA Glutamatergic Neurons Mediate Innate Defensive Behaviors. Neuron 2020, 107, (2), 368-382 e8. [CrossRef]

- Zell, V.; Steinkellner, T.; Hollon, N. G.; Warlow, S. M.; Souter, E.; Faget, L.; Hunker, A. C.; Jin, X.; Zweifel, L. S.; Hnasko, T. S., VTA Glutamate Neuron Activity Drives Positive Reinforcement Absent Dopamine Co-release. Neuron 2020, 107, (5), 864-873 e4. [CrossRef]

- Takamori, S.; Rhee, J. S.; Rosenmund, C.; Jahn, R., Identification of a vesicular glutamate transporter that defines a glutamatergic phenotype in neurons. Nature 2000, 407, (6801), 189-94. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Sheen, W.; Morales, M., Glutamatergic neurons are present in the rat ventral tegmental area. Eur J Neurosci 2007, 25, (1), 106-18. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Wang, H. L.; Li, X.; Ng, T. H.; Morales, M., Mesocorticolimbic glutamatergic pathway. J Neurosci 2011, 31, (23), 8476-90. [CrossRef]

- Stuber, G. D.; Hnasko, T. S.; Britt, J. P.; Edwards, R. H.; Bonci, A., Dopaminergic terminals in the nucleus accumbens but not the dorsal striatum corelease glutamate. J Neurosci 2010, 30, (24), 8229-33. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, H.; Grayson, V. S.; Jovasevic, V.; Ren, W.; Centeno, M. V.; Guedea, A. L.; Meyer, M. A. A.; Wu, Y.; Gutruf, P.; Surmeier, D. J.; Gao, C.; Martina, M.; Apkarian, A. V.; Rogers, J. A.; Radulovic, J., Excitatory VTA to DH projections provide a valence signal to memory circuits. Nat Commun 2020, 11, (1), 1466. [CrossRef]

- Lammel, S.; Lim, B. K.; Malenka, R. C., Reward and aversion in a heterogeneous midbrain dopamine system. Neuropharmacology 2014, 76 Pt B, (0 0), 351-9. [CrossRef]

- Stopper, C. M.; Floresco, S. B., What's better for me? Fundamental role for lateral habenula in promoting subjective decision biases. Nat Neurosci 2014, 17, (1), 33-5. [CrossRef]

- Root, D. H.; Mejias-Aponte, C. A.; Qi, J.; Morales, M., Role of glutamatergic projections from ventral tegmental area to lateral habenula in aversive conditioning. J Neurosci 2014, 34, (42), 13906-10. [CrossRef]

- Hempel, B.; Xi, Z. X., Receptor mechanisms underlying the CNS effects of cannabinoids: CB(1) receptor and beyond. Adv Pharmacol 2022, 93, 275-333. [CrossRef]

- Soler-Cedeno, O.; Xi, Z. X., Neutral CB1 Receptor Antagonists as Pharmacotherapies for Substance Use Disorders: Rationale, Evidence, and Challenge. Cells 2022, 11, (20). [CrossRef]

- Galaj, E.; Xi, Z. X., Progress in opioid reward research: From a canonical two-neuron hypothesis to two neural circuits. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2021, 200, 173072. [CrossRef]

- Fields, H. L.; Margolis, E. B., Understanding opioid reward. Trends Neurosci 2015, 38, (4), 217-25. [CrossRef]

- Matsui, A.; Jarvie, B. C.; Robinson, B. G.; Hentges, S. T.; Williams, J. T., Separate GABA afferents to dopamine neurons mediate acute action of opioids, development of tolerance, and expression of withdrawal. Neuron 2014, 82, (6), 1346-56. [CrossRef]

- McGovern, D. J.; Polter, A. M.; Prevost, E. D.; Ly, A.; McNulty, C. J.; Rubinstein, B.; Root, D. H., Ventral tegmental area glutamate neurons establish a mu-opioid receptor gated circuit to mesolimbic dopamine neurons and regulate opioid-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, (13), 1889-1900. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, K. C.; Kube, M. J.; Grecco, G. G.; Fritz, B. M.; Munoz, B.; Yin, F.; Gao, Y.; Haggerty, D. L.; Hoffman, H. J.; Atwood, B. K., Mu opioid receptors on vGluT2-expressing glutamatergic neurons modulate opioid reward. Addict Biol 2021, 26, (3), e12942. [CrossRef]

- Jalabert, M.; Bourdy, R.; Courtin, J.; Veinante, P.; Manzoni, O. J.; Barrot, M.; Georges, F., Neuronal circuits underlying acute morphine action on dopamine neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, (39), 16446-50. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; Luan, W.; Song, J.; Cui, D.; Dong, Y.; Lai, B.; Ma, L.; Zheng, P., Morphine disinhibits glutamatergic input to VTA dopamine neurons and promotes dopamine neuron excitation. Elife 2015, 4. [CrossRef]

- van Zessen, R.; Phillips, J. L.; Budygin, E. A.; Stuber, G. D., Activation of VTA GABA neurons disrupts reward consumption. Neuron 2012, 73, (6), 1184-94. [CrossRef]

- Bouarab, C.; Thompson, B.; Polter, A. M., VTA GABA Neurons at the Interface of Stress and Reward. Front Neural Circuits 2019, 13, 78. [CrossRef]

- Beier, K. T.; Gao, X. J.; Xie, S.; DeLoach, K. E.; Malenka, R. C.; Luo, L., Topological Organization of Ventral Tegmental Area Connectivity Revealed by Viral-Genetic Dissection of Input-Output Relations. Cell Rep 2019, 26, (1), 159-167 e6. [CrossRef]

- Creed, M. C.; Ntamati, N. R.; Tan, K. R., VTA GABA neurons modulate specific learning behaviors through the control of dopamine and cholinergic systems. Front Behav Neurosci 2014, 8, 8. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. T.; Tan, K. R.; O'Connor, E. C.; Nikonenko, I.; Muller, D.; Luscher, C., Ventral tegmental area GABA projections pause accumbal cholinergic interneurons to enhance associative learning. Nature 2012, 492, (7429), 452-6. [CrossRef]

- Omelchenko, N.; Sesack, S. R., Ultrastructural analysis of local collaterals of rat ventral tegmental area neurons: GABA phenotype and synapses onto dopamine and GABA cells. Synapse 2009, 63, (10), 895-906. [CrossRef]

- Matsui, A.; Williams, J. T., Opioid-sensitive GABA inputs from rostromedial tegmental nucleus synapse onto midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 2011, 31, (48), 17729-35. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ba, W.; Zhao, G.; Ma, Y.; Harding, E. C.; Yin, L.; Wang, D.; Li, H.; Zhang, P.; Shi, Y.; Yustos, R.; Vyssotski, A. L.; Dong, H.; Franks, N. P.; Wisden, W., Dysfunction of ventral tegmental area GABA neurons causes mania-like behavior. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, (9), 5213-5228. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Matsubara, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Ono, D.; Fukatsu, N.; Abe, M.; Sakimura, K.; Sudo, Y.; Yamanaka, A., GABA neurons in the ventral tegmental area regulate non-rapid eye movement sleep in mice. Elife 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Tan, K. R.; Yvon, C.; Turiault, M.; Mirzabekov, J. J.; Doehner, J.; Labouebe, G.; Deisseroth, K.; Tye, K. M.; Luscher, C., GABA neurons of the VTA drive conditioned place aversion. Neuron 2012, 73, (6), 1173-83. [CrossRef]

- Graveland, G. A.; DiFiglia, M., The frequency and distribution of medium-sized neurons with indented nuclei in the primate and rodent neostriatum. Brain Res 1985, 327, (1-2), 307-11. [CrossRef]

- Surmeier, D. J.; Ding, J.; Day, M.; Wang, Z.; Shen, W., D1 and D2 dopamine-receptor modulation of striatal glutamatergic signaling in striatal medium spiny neurons. Trends Neurosci 2007, 30, (5), 228-35. [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, A. V.; Tye, L. D.; Kreitzer, A. C., Distinct roles for direct and indirect pathway striatal neurons in reinforcement. Nat Neurosci 2012, 15, (6), 816-8. [CrossRef]

- Lalive, A. L.; Lien, A. D.; Roseberry, T. K.; Donahue, C. H.; Kreitzer, A. C., Motor thalamus supports striatum-driven reinforcement. Elife 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Vicente, A. M.; Galvao-Ferreira, P.; Tecuapetla, F.; Costa, R. M., Direct and indirect dorsolateral striatum pathways reinforce different action strategies. Curr Biol 2016, 26, (7), R267-9. [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. L.; Robinson, M. J. F.; Berridge, K. C., Optogenetic self-stimulation in the nucleus accumbens: D1 reward versus D2 ambivalence. PLoS One 2018, 13, (11), e0207694. [CrossRef]

- Gadziola, M. A.; Stetzik, L. A.; Wright, K. N.; Milton, A. J.; Arakawa, K.; Del Mar Cortijo, M.; Wesson, D. W., A Neural System that Represents the Association of Odors with Rewarded Outcomes and Promotes Behavioral Engagement. Cell Rep 2020, 32, (3), 107919. [CrossRef]

- Lippert, M. T. T., K.; Weidner, T.; Brocka. M.; Tegtmeier, J.; Ohl, F.W., Chapter 17 - Optogenetic Intracranial Self-Stimulation as a Method to Study the Plasticity-Inducing Effects of Dopamine. In Handbook of in vivo neural plasticity techniques, 2018; Vol. 28, pp 311-326. [CrossRef]

- Carter, L. P.; Griffiths, R. R., Principles of laboratory assessment of drug abuse liability and implications for clinical development. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009, 105 Suppl 1, S14-25. [CrossRef]

- Horton, D. B.; Potter, D. M.; Mead, A. N., A translational pharmacology approach to understanding the predictive value of abuse potential assessments. Behav Pharmacol 2013, 24, (5-6), 410-36. [CrossRef]

- Administration, F. a. D., Assessment of Abuse Potential of Drugs, Guidance for Industry. In 2017.

- Tye, K. M.; Deisseroth, K., Optogenetic investigation of neural circuits underlying brain disease in animal models. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012, 13, (4), 251-66. [CrossRef]

- Moerke, M. J.; Negus, S. S., Interactions between pain states and opioid reward assessed with intracranial self-stimulation in rats. Neuropharmacology 2019, 160, 107689. [CrossRef]

- Root, D. H.; Estrin, D. J.; Morales, M., Aversion or Salience Signaling by Ventral Tegmental Area Glutamate Neurons. iScience 2018, 2, 51-62. [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z. X.; Kiyatkin, M.; Li, X.; Peng, X. Q.; Wiggins, A.; Spiller, K.; Li, J.; Gardner, E. L., N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) inhibits intravenous cocaine self-administration and cocaine-enhanced brain-stimulation reward in rats. Neuropharmacology 2010, 58, (1), 304-13. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C. J.; Feng, Z. W.; Galaj, E.; Bi, G. H.; Xue, Y.; Liang, Y.; McGuire, T.; Xie, X. Q.; Xi, Z. X., Xie2-64, a novel CB(2) receptor inverse agonist, reduces cocaine abuse-related behaviors in rodents. Neuropharmacology 2020, 176, 108241. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, E. E.; Boivin, J. R.; Saunders, B. T.; Witten, I. B.; Deisseroth, K.; Janak, P. H., Positive reinforcement mediated by midbrain dopamine neurons requires D1 and D2 receptor activation in the nucleus accumbens. PLoS One 2014, 9, (4), e94771. [CrossRef]

- Ilango, A.; Kesner, A. J.; Broker, C. J.; Wang, D. V.; Ikemoto, S., Phasic excitation of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons potentiates the initiation of conditioned approach behavior: parametric and reinforcement-schedule analyses. Front Behav Neurosci 2014, 8, 155. [CrossRef]

- McDevitt, R. A.; Tiran-Cappello, A.; Shen, H.; Balderas, I.; Britt, J. P.; Marino, R. A. M.; Chung, S. L.; Richie, C. T.; Harvey, B. K.; Bonci, A., Serotonergic versus nonserotonergic dorsal raphe projection neurons: differential participation in reward circuitry. Cell Rep 2014, 8, (6), 1857-1869. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Simmler, L. D.; Van Zessen, R.; Flakowski, J.; Wan, J. X.; Deng, F.; Li, Y. L.; Nautiyal, K. M.; Pascoli, V.; Luscher, C., Synaptic mechanism underlying serotonin modulation of transition to cocaine addiction. Science 2021, 373, (6560), 1252-1256. [CrossRef]

- Pascoli, V.; Terrier, J.; Hiver, A.; Luscher, C., Sufficiency of Mesolimbic Dopamine Neuron Stimulation for the Progression to Addiction. Neuron 2015, 88, (5), 1054-1066. [CrossRef]

- Harada, M.; Pascoli, V.; Hiver, A.; Flakowski, J.; Luscher, C., Corticostriatal Activity Driving Compulsive Reward Seeking. Biol Psychiatry 2021, 90, (12), 808-818. [CrossRef]

- Corre, J.; van Zessen, R.; Loureiro, M.; Patriarchi, T.; Tian, L.; Pascoli, V.; Luscher, C., Dopamine neurons projecting to medial shell of the nucleus accumbens drive heroin reinforcement. Elife 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Pascoli, V.; Hiver, A.; Van Zessen, R.; Loureiro, M.; Achargui, R.; Harada, M.; Flakowski, J.; Luscher, C., Stochastic synaptic plasticity underlying compulsion in a model of addiction. Nature 2018, 564, (7736), 366-371. [CrossRef]

- Berrios, J.; Stamatakis, A. M.; Kantak, P. A.; McElligott, Z. A.; Judson, M. C.; Aita, M.; Rougie, M.; Stuber, G. D.; Philpot, B. D., Loss of UBE3A from TH-expressing neurons suppresses GABA co-release and enhances VTA-NAc optical self-stimulation. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10702. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M. A.; Sukharnikova, T.; Hayrapetyan, V. Y.; Yang, L.; Yin, H. H., Operant self-stimulation of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra. PLoS One 2013, 8, (6), e65799. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Jing, M. Y.; Zhao, T. Y.; Wu, N.; Song, R.; Li, J., Role of dopamine projections from ventral tegmental area to nucleus accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex in reinforcement behaviors assessed using optogenetic manipulation. Metab Brain Dis 2017, 32, (5), 1491-1502. [CrossRef]

- Jing, M. Y.; Han, X.; Zhao, T. Y.; Wang, Z. Y.; Lu, G. Y.; Wu, N.; Song, R.; Li, J., Re-examining the role of ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons in motor activity and reinforcement by chemogenetic and optogenetic manipulation in mice. Metab Brain Dis 2019, 34, (5), 1421-1430. [CrossRef]

- Jing, M. Y.; Ding, X. Y.; Han, X.; Zhao, T. Y.; Luo, M. M.; Wu, N.; Li, J.; Song, R., Activation of mesocorticolimbic dopamine projections initiates cue-induced reinstatement of reward seeking in mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2022, 43, (9), 2276-2288. [CrossRef]

- Gnazzo, F. G.; Mourra, D.; Guevara, C. A.; Beeler, J. A., Chronic food restriction enhances dopamine-mediated intracranial self-stimulation. Neuroreport 2021, 32, (13), 1128-1133. [CrossRef]

- Stuber, G. D.; Sparta, D. R.; Stamatakis, A. M.; van Leeuwen, W. A.; Hardjoprajitno, J. E.; Cho, S.; Tye, K. M.; Kempadoo, K. A.; Zhang, F.; Deisseroth, K.; Bonci, A., Excitatory transmission from the amygdala to nucleus accumbens facilitates reward seeking. Nature 2011, 475, (7356), 377-80. [CrossRef]

- Britt, J. P.; Benaliouad, F.; McDevitt, R. A.; Stuber, G. D.; Wise, R. A.; Bonci, A., Synaptic and behavioral profile of multiple glutamatergic inputs to the nucleus accumbens. Neuron 2012, 76, (4), 790-803. [CrossRef]

- Prado, L.; Luis-Islas, J.; Sandoval, O. I.; Puron, L.; Gil, M. M.; Luna, A.; Arias-Garcia, M. A.; Galarraga, E.; Simon, S. A.; Gutierrez, R., Activation of Glutamatergic Fibers in the Anterior NAc Shell Modulates Reward Activity in the aNAcSh, the Lateral Hypothalamus, and Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Transiently Stops Feeding. J Neurosci 2016, 36, (50), 12511-12529. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J. H.; Zell, V.; Wu, J.; Punta, C.; Ramajayam, N.; Shen, X.; Faget, L.; Lilascharoen, V.; Lim, B. K.; Hnasko, T. S., Activation of Pedunculopontine Glutamate Neurons Is Reinforcing. J Neurosci 2017, 37, (1), 38-46. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. A.; Voyvodic, L.; Loewinger, G. C.; Mateo, Y.; Lovinger, D. M., Operant self-stimulation of thalamic terminals in the dorsomedial striatum is constrained by metabotropic glutamate receptor 2. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, (9), 1454-1462. [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Tellez, L. A.; Perkins, M. H.; Perez, I. O.; Qu, T.; Ferreira, J.; Ferreira, T. L.; Quinn, D.; Liu, Z. W.; Gao, X. B.; Kaelberer, M. M.; Bohorquez, D. V.; Shammah-Lagnado, S. J.; de Lartigue, G.; de Araujo, I. E., A Neural Circuit for Gut-Induced Reward. Cell 2018, 175, (3), 887-888.

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Hu, F.; Lu, Y.; Ma, M.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, J. E.; Wang, D.; Zeng, J.; Bao, J.; Kim, J. Y.; Chen, Z. F.; El Mestikawy, S.; Luo, M., Dorsal raphe neurons signal reward through 5-HT and glutamate. Neuron 2014, 81, (6), 1360-1374. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y. W.; Morton, G.; Guy, E. G.; Wang, S. D.; Turner, E. E., Dorsal Medial Habenula Regulation of Mood-Related Behaviors and Primary Reinforcement by Tachykinin-Expressing Habenula Neurons. eNeuro 2016, 3, (3). [CrossRef]

- Petter, E. A.; Fallon, I. P.; Hughes, R. N.; Watson, G. D. R.; Meck, W. H.; Ulloa Severino, F. P.; Yin, H. H., Elucidating a locus coeruleus-dentate gyrus dopamine pathway for operant reinforcement. Elife 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The effects of cocaine and THC on electrical brain-stimulation reward (BSR) in rats. (A) A diagram illustrates the medial forebrain bundle at the anterior–posterior level of the lateral hypothalamus and the location of a stimulation electrode for electrical BSR. (B) Representative stimulation–response curves, indicating that systemic administration of cocaine shifted the stimulation–response curve to the left and decreased the BSR stimulation threshold (θ0) and M50. (C, D) The effects of cocaine on the mean (± SEM) values of BSR stimulation threshold (θ0) (C) and M50 (D), indicating that cocaine dose-dependently shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the left and decreased the θ0 and M50 values. (E, F) The effects of THC on the mean (±SEM) values of θ0 (E) and M50 (F), indicating that THC produced biphasic effects – THC, at a low dose (1 mg/kg, i.p.) shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the left and decreased the θ0 and M50 values, while, at a high dose (5 mg/kg), THC shifted the curve to the right and increases θ0 and M50 values.*p<0.05, **p<0.01, compared to the vehicle control group; one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Student–Newman–Keuls tests for multiple group comparisons. Adapted from Xi et al., 2010 and Spiller et al., 2019 [14,113].

Figure 1.

The effects of cocaine and THC on electrical brain-stimulation reward (BSR) in rats. (A) A diagram illustrates the medial forebrain bundle at the anterior–posterior level of the lateral hypothalamus and the location of a stimulation electrode for electrical BSR. (B) Representative stimulation–response curves, indicating that systemic administration of cocaine shifted the stimulation–response curve to the left and decreased the BSR stimulation threshold (θ0) and M50. (C, D) The effects of cocaine on the mean (± SEM) values of BSR stimulation threshold (θ0) (C) and M50 (D), indicating that cocaine dose-dependently shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the left and decreased the θ0 and M50 values. (E, F) The effects of THC on the mean (±SEM) values of θ0 (E) and M50 (F), indicating that THC produced biphasic effects – THC, at a low dose (1 mg/kg, i.p.) shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the left and decreased the θ0 and M50 values, while, at a high dose (5 mg/kg), THC shifted the curve to the right and increases θ0 and M50 values.*p<0.05, **p<0.01, compared to the vehicle control group; one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Student–Newman–Keuls tests for multiple group comparisons. Adapted from Xi et al., 2010 and Spiller et al., 2019 [14,113].

Figure 2.

Optical intracranial self-stimulation (oICSS) experiment in DAT-Cre mice. (A) Schematic diagrams illustrating that AAV-ChR2-eYFP vectors were microinjected into the lateral VTA and optical fibers (i.e., optrodes) were implanted in the same brain region. (B) A diagram illustrates AAV-ChR2 is expressed on VTA DA neurons, which can be activated by 473 nm laser. (C) Representative images of AAV-ChR2-eYFP and TH expression in the VTA. (D) the stimulation-rate response curves, indicating that optogenetic activation of VTA DA neurons induced robust oICSS behavior (lever presses) in DAT-Cre mice in a stimulation frequency-dependent manner. Systemic administration of cocaine shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the left and decreased M50 values. (E) Cocaine-induced % changes in M50 over pre-cocaine baseline. (F) Effects of THC on DA-dependent oICSS. Systemic administration of THC dose-dependently shifted the curve to the right and increased M50 values. (G) THC-induced % changes in M50 over pre-THC baseline. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, compared with the vehicle control group. Adapted from Hempel et al., 2023 and Jordan et al., 2020 [58,114].

Figure 2.

Optical intracranial self-stimulation (oICSS) experiment in DAT-Cre mice. (A) Schematic diagrams illustrating that AAV-ChR2-eYFP vectors were microinjected into the lateral VTA and optical fibers (i.e., optrodes) were implanted in the same brain region. (B) A diagram illustrates AAV-ChR2 is expressed on VTA DA neurons, which can be activated by 473 nm laser. (C) Representative images of AAV-ChR2-eYFP and TH expression in the VTA. (D) the stimulation-rate response curves, indicating that optogenetic activation of VTA DA neurons induced robust oICSS behavior (lever presses) in DAT-Cre mice in a stimulation frequency-dependent manner. Systemic administration of cocaine shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the left and decreased M50 values. (E) Cocaine-induced % changes in M50 over pre-cocaine baseline. (F) Effects of THC on DA-dependent oICSS. Systemic administration of THC dose-dependently shifted the curve to the right and increased M50 values. (G) THC-induced % changes in M50 over pre-THC baseline. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, compared with the vehicle control group. Adapted from Hempel et al., 2023 and Jordan et al., 2020 [58,114].

Figure 3.

Optical intracranial self-stimulation (oICSS) experiment in VgluT2-Cre mice. (A) Schematic diagrams illustrating the target brain region (VTA) of the AAV-ChR2-GFP microinjection and intracranial optical fiber implantation. (B) Schematic diagram showing VTA glutamate projections. Within the VTA, some glutamate neurons locally synapse onto DA neurons. (C) Representative images of AAV-ChR2-EGFP expression in the medial VTA. (D, E) The stimulation frequency-rate response curve, indicating that optical stimulation of VTA glutamate neurons produced robust oICSS in VgluT2-Cre mice in a stimulation frequency-dependent manner. Systemic administration of SCH23390, a selective D1 receptor antagonist significantly inhibited the oICSS (D), while L-741,626, a selective D2 receptor antagonist, also dose-dependently inhibited the oICSS (E). (F, G) Systemic administration of cocaine dose-dependently shifted the rate-frequency function curve leftward and upward in VgluT2-Cre mice (F), while THC produced an opposite effect, producing a dose-dependent rightward shift (G). Adapted from Han et al., 2017[13].

Figure 3.

Optical intracranial self-stimulation (oICSS) experiment in VgluT2-Cre mice. (A) Schematic diagrams illustrating the target brain region (VTA) of the AAV-ChR2-GFP microinjection and intracranial optical fiber implantation. (B) Schematic diagram showing VTA glutamate projections. Within the VTA, some glutamate neurons locally synapse onto DA neurons. (C) Representative images of AAV-ChR2-EGFP expression in the medial VTA. (D, E) The stimulation frequency-rate response curve, indicating that optical stimulation of VTA glutamate neurons produced robust oICSS in VgluT2-Cre mice in a stimulation frequency-dependent manner. Systemic administration of SCH23390, a selective D1 receptor antagonist significantly inhibited the oICSS (D), while L-741,626, a selective D2 receptor antagonist, also dose-dependently inhibited the oICSS (E). (F, G) Systemic administration of cocaine dose-dependently shifted the rate-frequency function curve leftward and upward in VgluT2-Cre mice (F), while THC produced an opposite effect, producing a dose-dependent rightward shift (G). Adapted from Han et al., 2017[13].

Figure 4.

Optical intracranial self-stimulation (oICSS) experiment in Vgat-Cre mice. (A) Schematic diagrams illustrating that the AAV-ChR2-GFP was microinjected into bilateral NAc and optical fibers were implanted into the VTA. (B) Schematic diagram illustrating a working hypothesis that D1-MSNs project from the NAc to the VTA and synapse on VTA GABAergic interneurons that project to VTA DA neurons. Optical stimulation of NAc D1-MSN GABAergic terminals in the VTA disinhibits DA neurons via GABAergic interneurons, producing positive oICSS. (C, D) Representative images of AAV-ChR2-EGFP expression in the NAc (AAV injection site) and VTA (D1-MSN projection area). (E) The frequency-rate response curve of oICSS in Vgat-Cre mice, illustrating that flupentixol, a non-selective DA receptor antagonist, dose-dependently attenuated oICSS maintained by optical activation of NAc D1-MSN GABA terminals in the VTA. (F) Systemic administration of cocaine dose-dependently enhanced oICSS and shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the left. (G) In contrast, systemic administration of heroin dose-dependently decreased oICSS and shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the right. *p<0.05, compared to the vehicle control group.

Figure 4.

Optical intracranial self-stimulation (oICSS) experiment in Vgat-Cre mice. (A) Schematic diagrams illustrating that the AAV-ChR2-GFP was microinjected into bilateral NAc and optical fibers were implanted into the VTA. (B) Schematic diagram illustrating a working hypothesis that D1-MSNs project from the NAc to the VTA and synapse on VTA GABAergic interneurons that project to VTA DA neurons. Optical stimulation of NAc D1-MSN GABAergic terminals in the VTA disinhibits DA neurons via GABAergic interneurons, producing positive oICSS. (C, D) Representative images of AAV-ChR2-EGFP expression in the NAc (AAV injection site) and VTA (D1-MSN projection area). (E) The frequency-rate response curve of oICSS in Vgat-Cre mice, illustrating that flupentixol, a non-selective DA receptor antagonist, dose-dependently attenuated oICSS maintained by optical activation of NAc D1-MSN GABA terminals in the VTA. (F) Systemic administration of cocaine dose-dependently enhanced oICSS and shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the left. (G) In contrast, systemic administration of heroin dose-dependently decreased oICSS and shifted the frequency-rate response curve to the right. *p<0.05, compared to the vehicle control group.

Table 1.

Neural substrates underlie oICSS when activated.

Table 1.

Neural substrates underlie oICSS when activated.

| Animals |

Brain region |

Targeted Neurons |

Opsins |

Stim. Frequency |

Finding |

References |

| Dopamine-dependent oICSS |

| TH-Cre rats |

VTA |

DA |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[43,115] |

| TH-Cre mice |

VTA, SNc |

DA |

ChR2 |

25 Hz |

oICSS |

[47,116] |

| TH-Cre mice |

VTA |

DA |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[117] |

| TH-Cre |

VTA |

DA |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[118,119,120,121,122] |

| DAT-Cre mice |

VTA-NAc |

DA terminals |

ChR2 |

30 Hz |

oICSS |

[123] |

| DAT-Cre |

SNc |

DA |

ChR2 |

50 Hz |

oICSS |

[124] |

| DAT-Cre mice |

VTA |

DA |

ChR2 |

1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 Hz |

oICSS |

[17,18,44,45,46] |

| DAT-Cre, Crhr1-, Cck-, mice |

VTA |

DA |

ChR2 |

20Hz |

oICSS |

[48] |

| DAT-Cre mice |

VTA |

DA |

ChR2 |

1, 5, 10, 20, 25, 50, Hz |

oICSS |

[125] |

| DAT-Cre mice |

VTA |

DA |

ChR2 |

1, 5, 10, 20, 25, 50, 65 Hz |

oICSS |

[126] |

| DAT-Cre mice |

VTA |

DA |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[127] |

| DAT-Cre mice |

NAc, PFC |

DA terminals |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[127] |

| DAT-Cre |

VTA |

DA |

ChR2 |

40 Hz |

oICSS |

[128] |

| D1-Cre |

Dentate gyrus |

DA |

|

|

|

|

| Glutamate-dependent oICSS |

| C57 WT mice |

BLA-VTA |

Glutamate |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[129] |

| C57 WT mice |

vHipp-NAc |

Glutamate |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[130] |

| VgluT2-Cre mice |

VTA |

Glutamate |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[32] |

| Thy1-ChR2-EYFP mice |

NAc |

Glutamate terminals |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[131] |

| VgluT2-Cre mice |

Pedunculopontine |

Glutamate |

ChR2 |

10, 20, 30, 40 Hz |

oICSS |

[132] |

| VgluT2-Cre mice |

VTA |

Glutamate |

ChR2 |

1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 Hz |

oICSS |

[13] |

| VgluT2-Cre mice |

DMS, |

Glutamate terminals |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[133] |

| VgluT2-Cre mice |

NAc |

Glutamate terminals |

ChR2 |

40 Hz |

oICSS |

[71] |

| VgluT2-Cre mice |

VTA |

Glutamate |

ChR2 |

10, 20, 30, 40 Hz |

oICSS |

[33] |

| VgluT2-Cre mice |

VP, NAc, LHb |

Glutamate terminals |

ChR2 |

10, 20, 30, 40 Hz |

oICSS |

[33] |

| VgluT2-Cre mice |

RN |

Glutamate |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[17] |

| VgluT2-Cre mice |

VTA |

Glutamate terminals |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[17] |

| VgluT2-Cre mice |

Parabrachio-SNc |

Glutamate terminals |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[134] |

| GABA-dependent oICSS |

| C57 WT |

NAc |

GABA |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[130] |

| Vgat-Cre |

SNr, |

GABA |

Halo |

Constant, 20 s |

oICSS |

[46] |

| Vgat-Cre |

SNr |

GABA |

Arch3 |

Constant, 3 s |

oICSS |

[102] |

| D1-Cre mice |

DS |

D1-MSNs |

ChR2 |

Constant, 1 s |

oICSS |

[101] |

| D1-Cre mice |

DS |

D1-MSNs |

ChR2 |

40Hz |

oICSS |

[102] |

| D1-Cre mice |

DS |

D1-MSNs |

ChR2 |

5 Hz |

oICSS |

[103] |

| D1-Cre mice |

NAc |

D1-MSNs |

ChR2 |

25 Hz |

oICSS |

[104] |

| Other substance-dependent oICSS |

| ePet-Cre mice |

DRN |

5-HT |

ChR2 |

5, 20 Hz |

oICSS |

[135] |

| ePet-Cre mice |

DRN |

5-HT |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[117] |

| SERT-Cre mice |

DRN, 5-HT neurons |

5-HT |

ChR2 |

40 Hz |

oICSS |

[102] |

| Tac2-Cre mice |

dMHb |

Neurokinin-expressing |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[136] |

| D1-Cre |

LC-DG |

D1-expressing |

ChR2 |

20 Hz |

oICSS |

[137] |

Table 2.

Effects of drugs of abuse, dopaminergic ligands, and cannabinoids on oICSS.

Table 2.

Effects of drugs of abuse, dopaminergic ligands, and cannabinoids on oICSS.

| Tested drugs |

Mice |

oICSS |

Findings |

References |

| Drugs of abuse |

Cocaine

(5, 10, 15, 20 mg/kg) |

DAT-cre |

20 Hz |

↓ oICSS by 20 Hz laser |

[119] |

Heroin

(1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 mg/kg) |

DAT-cre |

20 Hz |

↓ oICSS by 20 Hz laser |

[121] |

Cocaine

(2, 10 mg/kg) |

DAT-Cre |

Frequency-rate (F-R) curve |

↑ oICSS,

Shift the F-R curve to the left |

[57,114] |

Oxycodone

(0.3, 1, 3 mg/kg) |

DAT-Cre |

F-R curve |

↑ oICSS at low doses,

↓ oICSS at high doses,

Shift the F-R curve upward or downward |

[55] |

| DAT inhibitors |

JJC8-088

(DAT inhibitor) |

DAT-Cre |

F-R curve |

↑ oICSS,

Shift the F-R curve upward |

[54] |

JJC8-091

(Atypical DAT inhibitor) |

DAT-Cre |

F-R curve |

↓ oICSS,

Shift the F-R curve downward |

[54] |

| Dopamine D3 receptor ligands |

(±)-VK4-40

(D3 antagonist) |

DAT-Cre |

F-R curve |

↓ oICSS,

Shift the F-R curve downward |

[57] |

R-VK4-40

(D3 antagonist) |

DAT-Cre |

F-R curve |

↓ oICSS,

Shift the F-R curve downward |

[55] |

S-VK4-40

(D3 partial agonist) |

DAT-Cre |

F-R curve |

↓ oICSS,

Shift the F-R curve downward |

[56] |

| Cannabinoid receptor agonists |

| THC |

DAT-Cre |

F-R curve |