Submitted:

18 January 2024

Posted:

19 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Methods

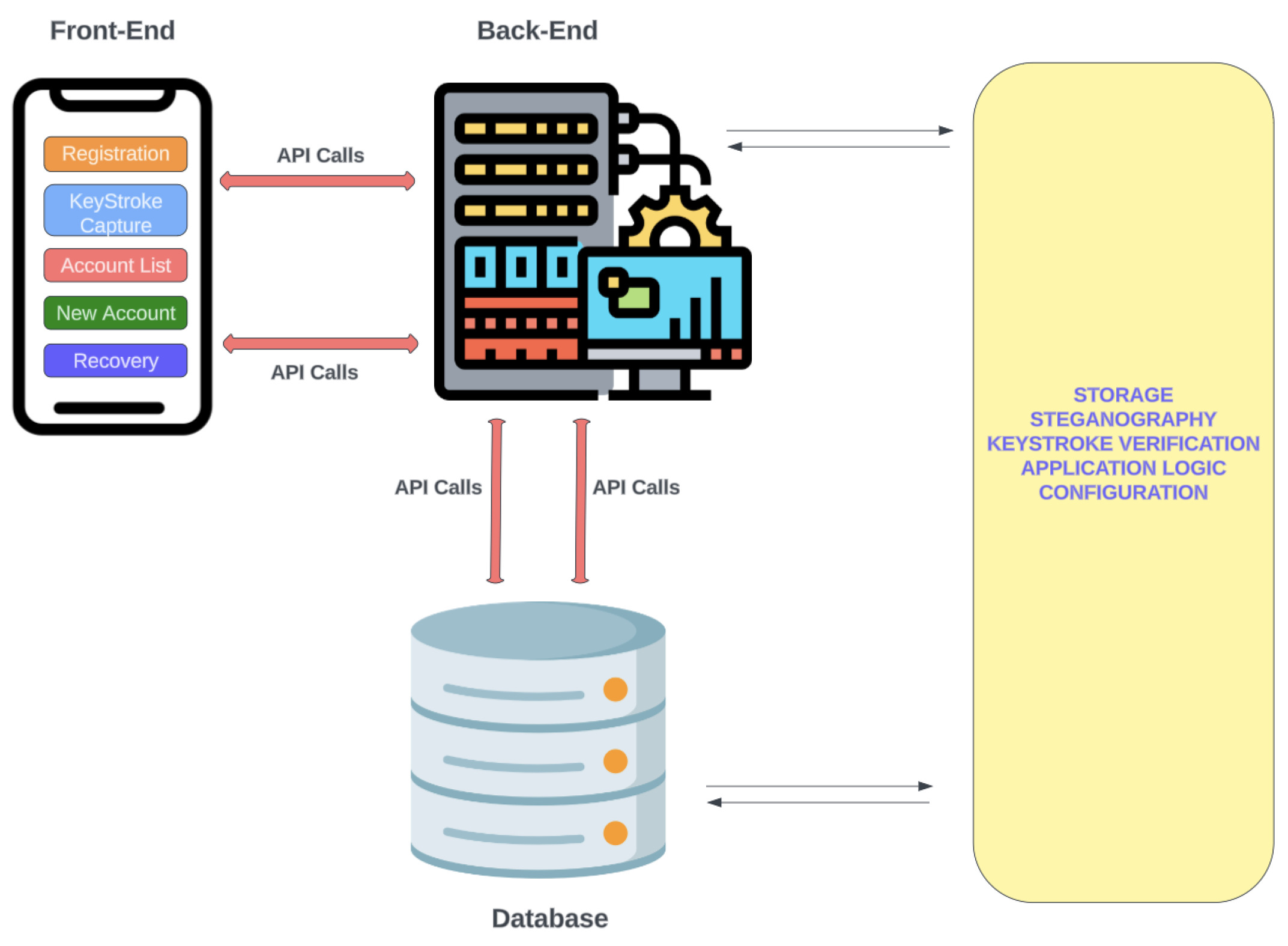

3.1. Architecture and System Design

-

Front-End (FE) - this is the part that the user interacts with, designed to work only on devices that run the Android and Apple iOS mobile operating systems. It is built using React Native (RN), “a JavaScript framework for writing natively rendering mobile applications for iOS and Android platforms”[5]. The FE contains the following interfaces:

- App Registration Screen (ARS) - when the application (“app”) is first installed, the app presents the ARS, where a username to be associated with the app is provided by the user via an input form. On submission of the form, the user is routed to the next section where their keystroke dynamics (typing pattern) is captured.

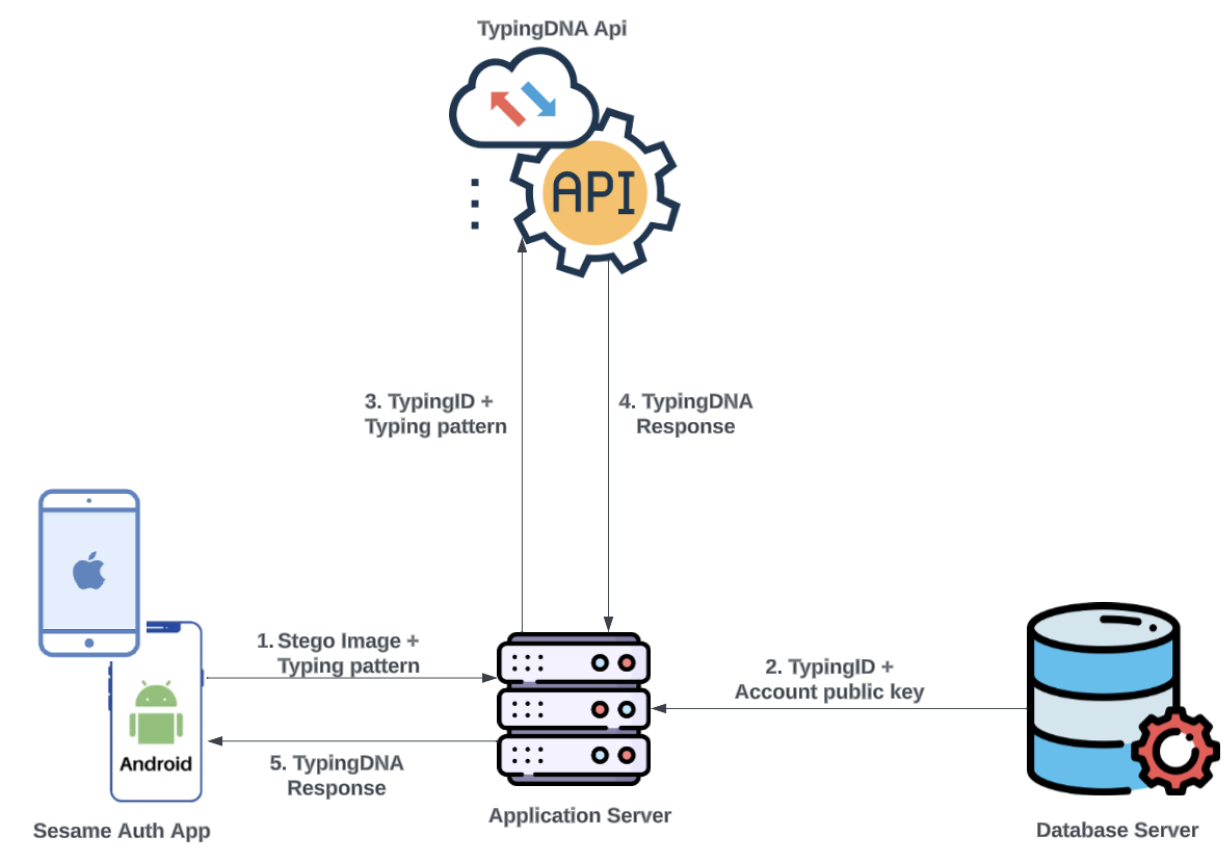

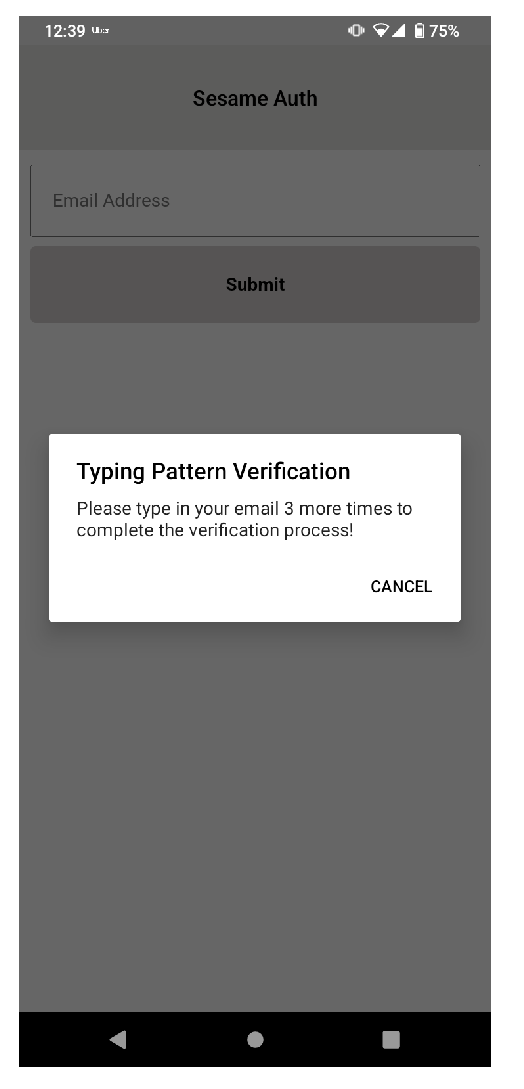

- Typing Behaviour Capture Screen (TBS) - authentication schemes are usually designed to mitigate situations where users lose access to their account credentials. SA captures the user’s typing pattern on TBS, on initial app installation, for the purpose of account recovery. Considering that people have unique patterns when typing on keyboards[6] this process replaces the need for security questions during account recovery, identifying the user by their behaviour instead. To achieve this, a typing biometric JavaScript library[7] is implemented on TBS; while the user is typing in the provided input field, their typing pattern is captured and assigned a unique identity. TBS is presented only when the app is first installed; once the user’s typing pattern is captured to the degree acceptable per TypingDNA API requirement, TBS is not presented on subsequent app launches. The user is prompted a minimum of 3 times[7] on TBS to type in their email address. Copy and paste is also disabled on TBS to ensure that the user types in the input field.Figure 1. SA high-level architecture and system design

- Accounts List Screen (ALS) - a list of all accounts added to the app by the user. This is the default interface presented to the user when the app is launched.

- New Account Screen (NAS) - provides functionality for adding accounts to the app and contains a section for the user to upload the image that will be embedded with credentials related to an account, using steganography.

- Account Import Screen (AIS) - during account retrieval, a user needs to provide the image that had been pre-embedded with the account details and their typing ID during initial registration. AIS offers the functionality to accept the image and capture a typing pattern; the captured typing pattern is compared with the typing pattern pre-associated with the typing ID embedded in the image supplied. If there is a match, the retrieval is successful.

- Back-End (BE) - this is the application server that interacts with the FE and Database server, handling logic relevant to the operation of the authentication process. It is designed using the Node.js programming language, “a JavaScript runtime built on Chrome’s V8 JavaScript engine”[8]. The BE comprises several API endpoints through which encrypted communication with the FE occurs in a request-response fashion over HTTPS.

- Database-this server stores data generated by the app using NoSQL, i.e. a non-relational format using key-value data representation.

3.2. Implementation

3.2.1. Pre-Installation

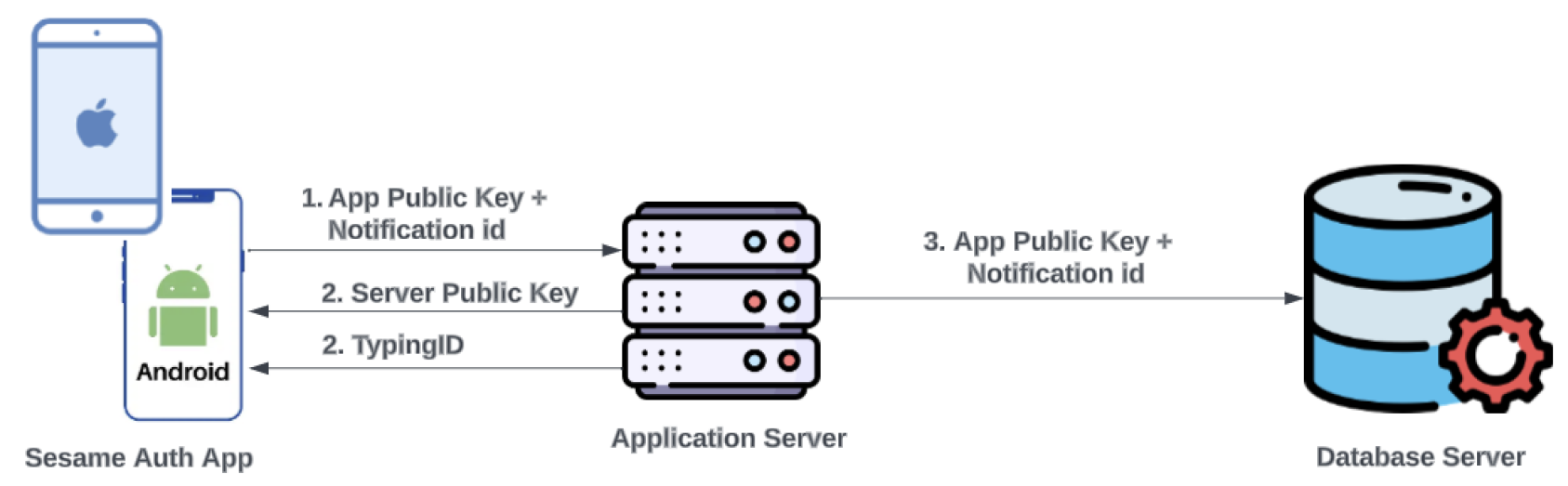

3.2.2. Installation

3.2.3. Post-Installation

- SA User registration (SAUR)

-

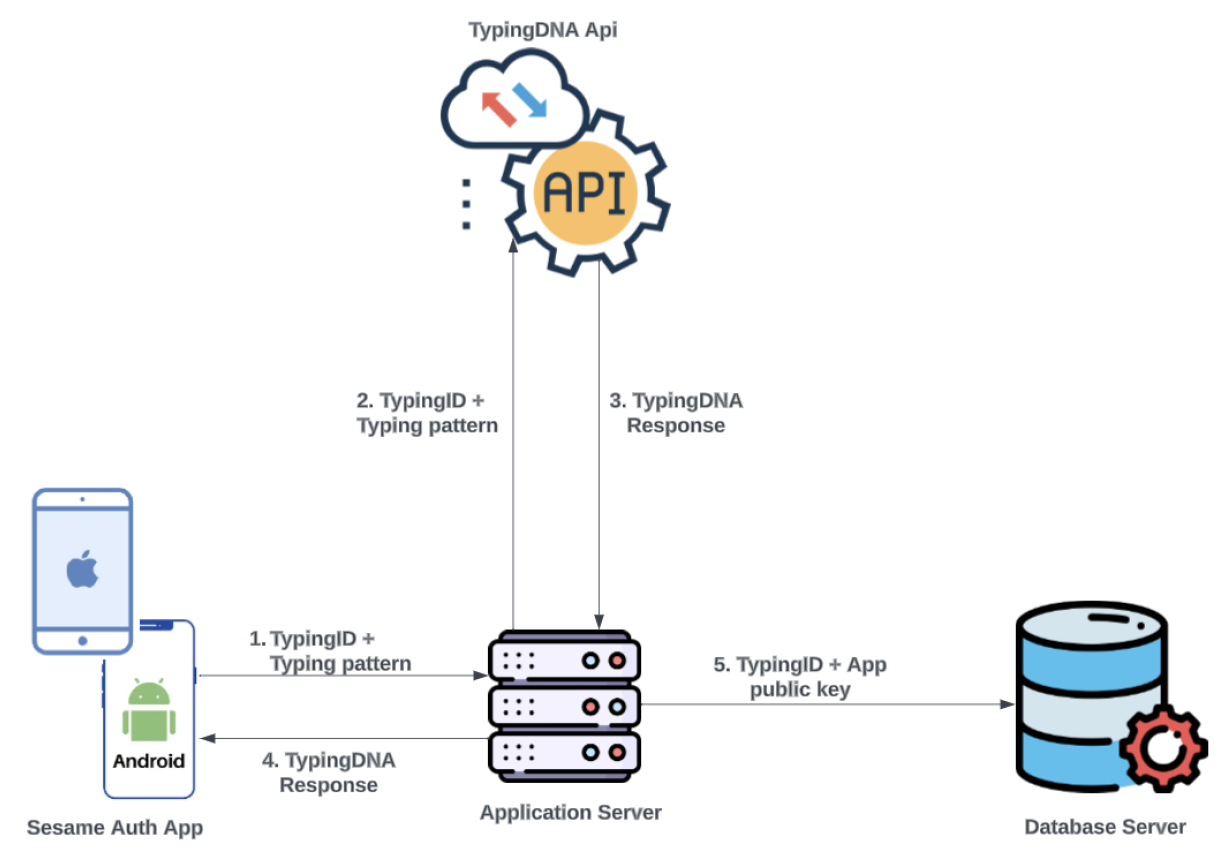

The user is presented with the typing behaviour capture screen, where their TP is recorded by the TypingDNA library implemented on the page. Before this data is sent to the server, biometric authentication is requested on the user’s device by prompting for either a fingerprint or face ID, depending on that which was previously set up by the user. The SA app is designed to work only on devices with biometric authentication capability. Once the user’s biometric information is confirmed, along with the unique ID received during the installation stage, the TP is encrypted with the server’s public key, and sent to the server for onward transmission to TypingDNA’s API to be recorded. The TP is then identified for that user via the unique ID. The user is prompted to enter a predefined text (their email address) a minimum of three times to ensure that enough patterns are captured to be able to create a model for the user[16].As depicted in Figure 3, once a response from the API signals that enough patterns have been received to verify the user, the unique ID is then saved as the user’s typing ID along with the app public key in the database. The user is subsequently routed to ALS.Figure 3. SA User typing behaviour capture

-

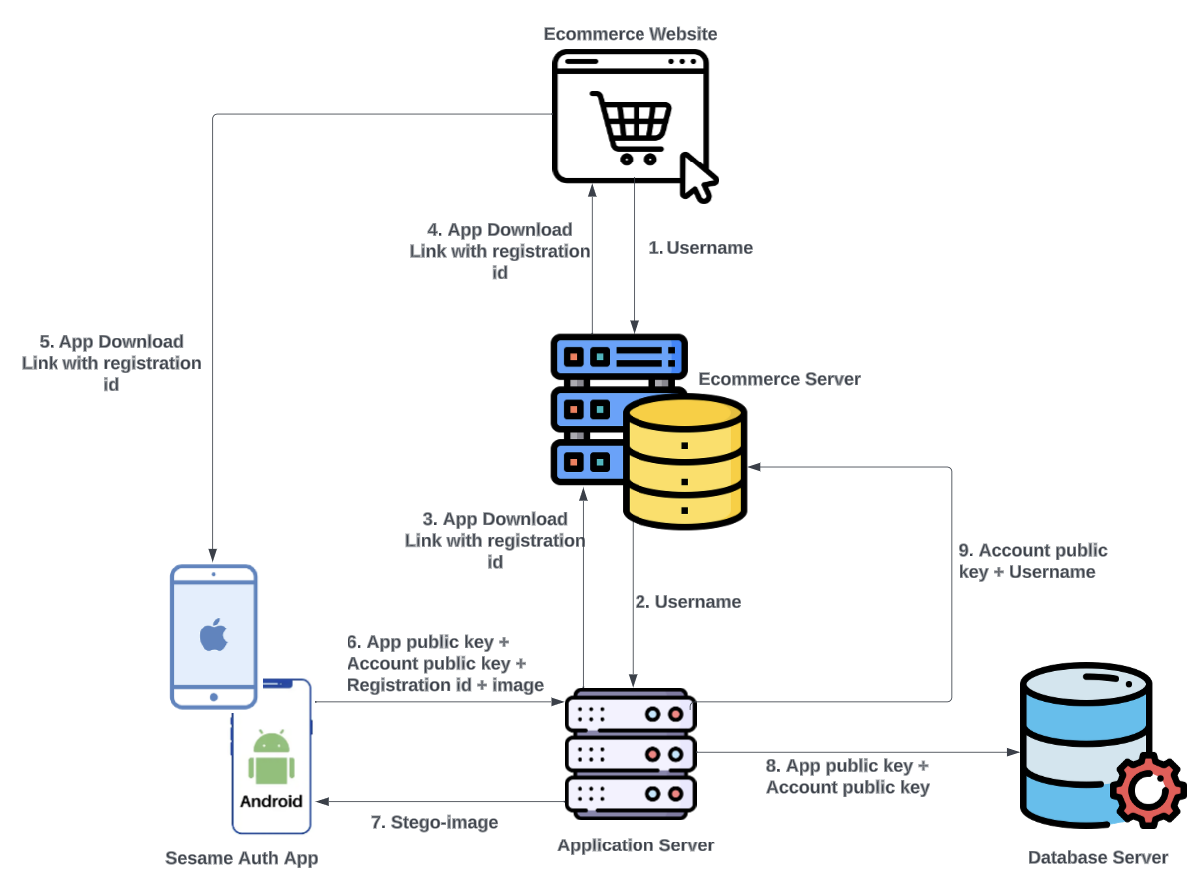

Account registration (e.g. an e-commerce website - "Ecom") Before a user can add an account to the app, the service (hereafter referred to as “Ecom”) they wish to add must have implemented the SA scheme. This is achieved by Ecom creating authenticated API endpoints on their server to receive requests from the SA server. With this implementation, usernames are associated with public keys rather than passwords. This ensures that if Ecom is breached, they hold a database of public keys rather than passwords or hashes, and usernames. The registration flow for new Ecom users differs from that of existing password-based users migrating to passwordless authentication and is described below.

-

New Ecom User Registration (NEUR)

- −

- User visits the Ecom website, creates an account according to Ecom’s process and selects the passwordless authentication option.

- −

- The username is sent from Ecom to SA server, through Ecom’s server as shown in Figure 4; requests from Ecom’s website to SA server are rejected by default. The communication between Ecom’s server and SA server are always authenticated.Figure 4. Ecom new user passwordless authentication registration flow

- −

- SA server generates a unique registration ID for the username and serves it as a response to the Ecom server’s request.

- −

- Ecom delivers the unique registration ID to the user embedded in a download link of the SA app.

- −

- When the user downloads and launches the app; the process described in Section 3.2.2 occurs. In addition, a 2048-bit RSA key pair is generated for the account. Each account on the SA app has a key pair separate from the key pair of the app.

- −

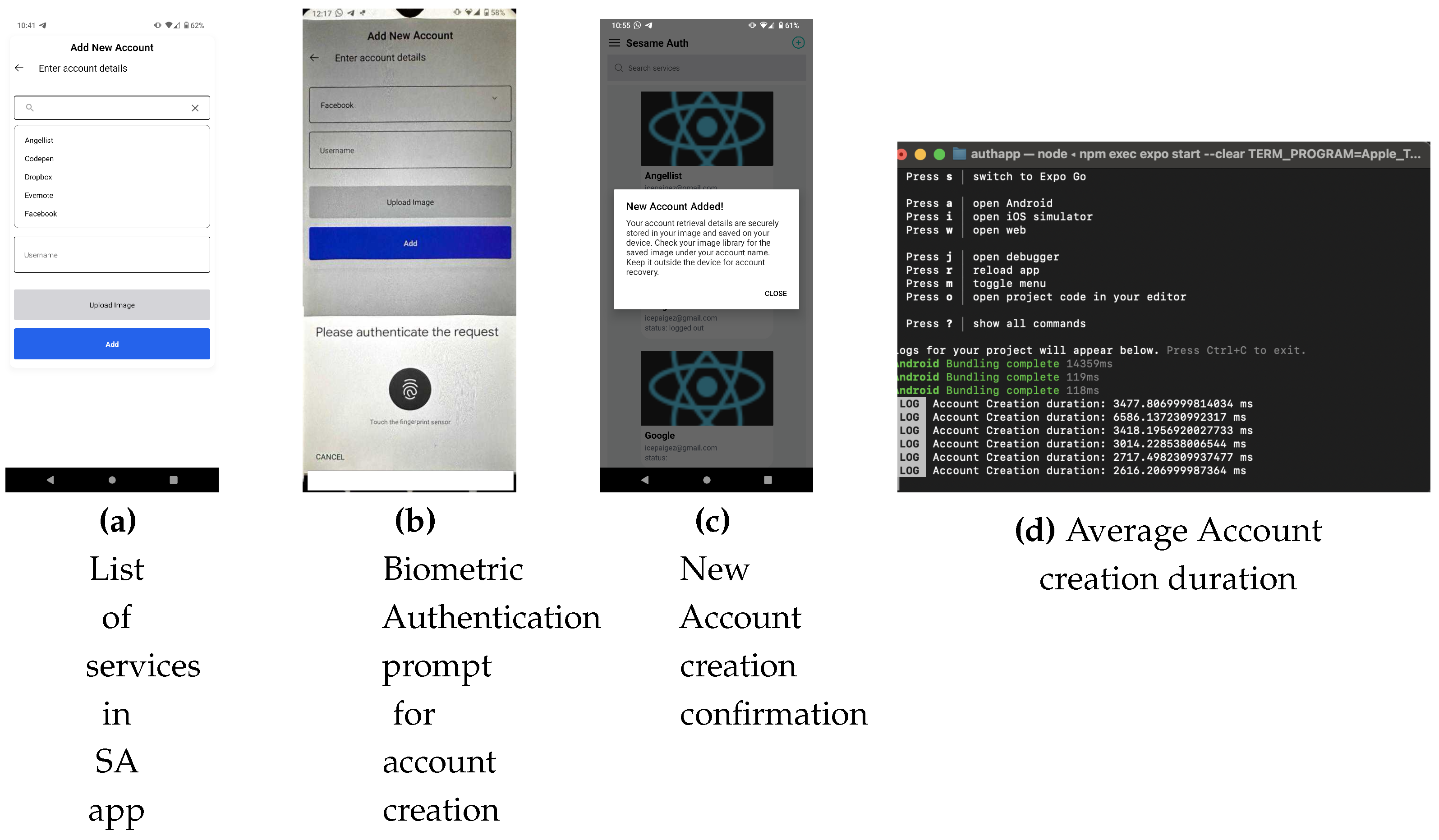

- The user is automatically routed to the NAS with the service name (Ecom) and username pre-filled. The user then needs to upload an image where the public key for that account and their typing ID will be embedded. When they click on the option to add the account, biometric authentication is requested by prompting the user for their fingerprint or face-ID.

- −

- On successful biometric authentication, the SA app sends the app public key, account public key, registration ID, and image file to the SA server. The server extracts the typing ID previously saved to the app public key (as described in section 3.2.3 - SAUR), encrypts it with the server private key, and embeds the encrypted typing ID and account public key in the image provided using steganography. The stego image is then sent to the user with a prompt to save it off the device for account retrieval purposes. The stego image is not saved in the database.

- −

- The SA app updates the accounts list with an entry for that service and username.

- −

- The SA server saves the account public key and username in the database, and it is matched to the public key for the app. The database has a mapping of accounts to an app, such that an app public key can hold multiple account public keys.

- −

- The SA server delivers the account public key and username to the Ecom server.

-

Existing Ecom User Registration - services that have implemented SA is listed as an option that can be selected on the NAS in the app. An existing user registers an account following the steps described below:

- −

- The user selects Ecom from a dropdown list on the NAS.

- −

- They provide their Ecom username and image in the input fields; when the user clicks the option to add the account, biometric authentication is requested by prompting the user for their fingerprint or face-ID.

- −

- On successful biometric authentication, a 2048-bit RSA key pair is generated for the account.

- −

- The process from item 7 of the NEUR section then occurs. Since this is an existing Ecom user, as shown in Figure 5, no registration ID is included as part of the data sent to the SA server.Figure 5. Ecom existing user passwordless authentication registration flow

-

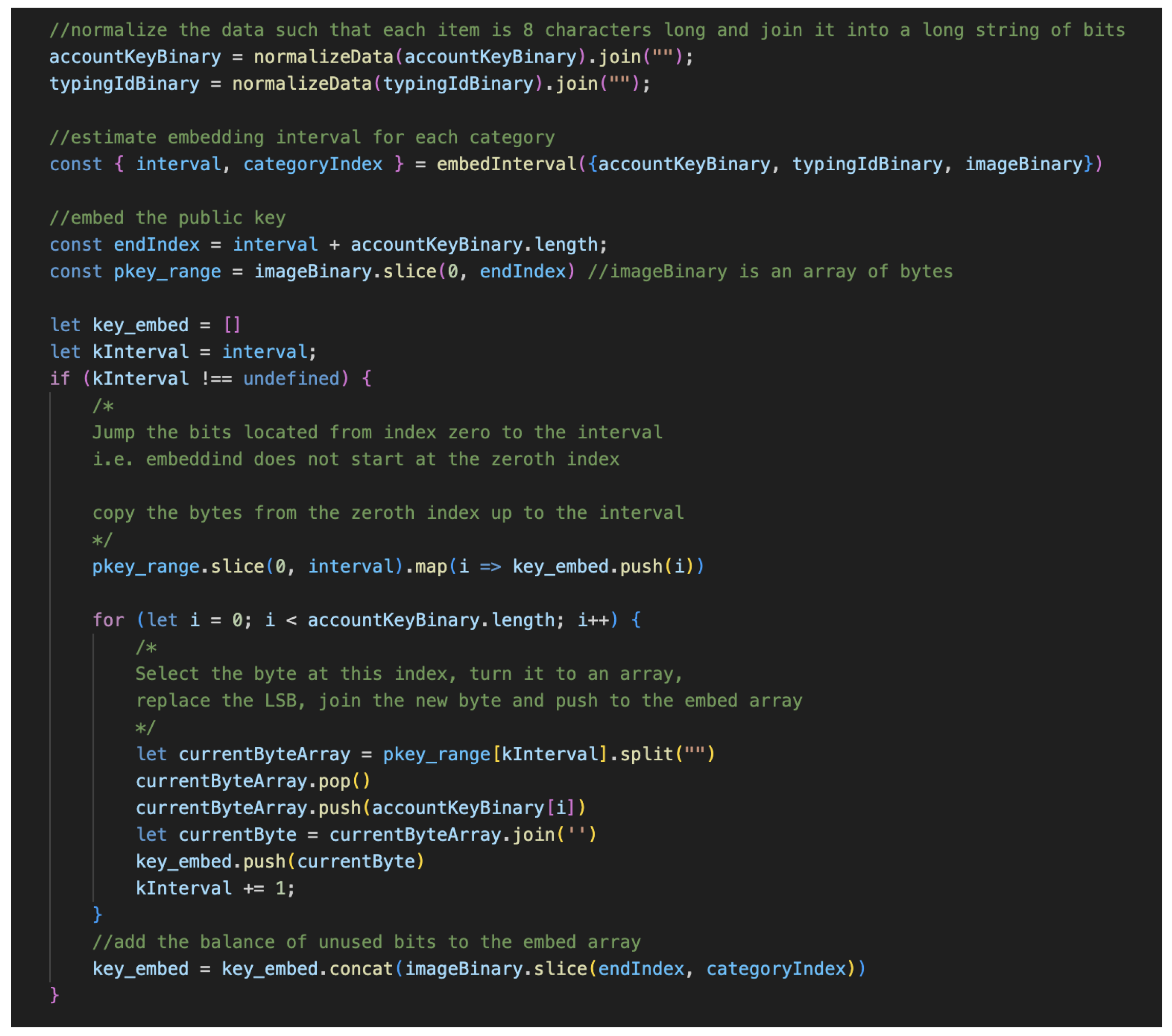

3.2.4. Image Steganography

- The image is converted into its binary format using the Jimp library[18].

- The user’s typing ID (associated with their typing pattern) is encrypted using the server’s public key. The public key for that account and the encrypted typing ID are then converted to their binary format. Each data is then joined into a long string of bits, as conversion to their binary format produces an array of bytes.

- Each bit from the string of bits from each group is then embedded into the image bytes using the least significant bit (LSB) steganography method. LSB involves replacing the right-most bit of each image byte with another bit from the data to be hidden[19]. The implication of this is that the number of bytes in the image must be at least the sum of all bits to be embedded.

- Once all the bits have been embedded in the LSB of the image, the new image is then reconstructed using the Jimp library; the new and original image will have no visual difference at the end of this process.

3.3. User Interaction Flow

3.3.1. User Authentication

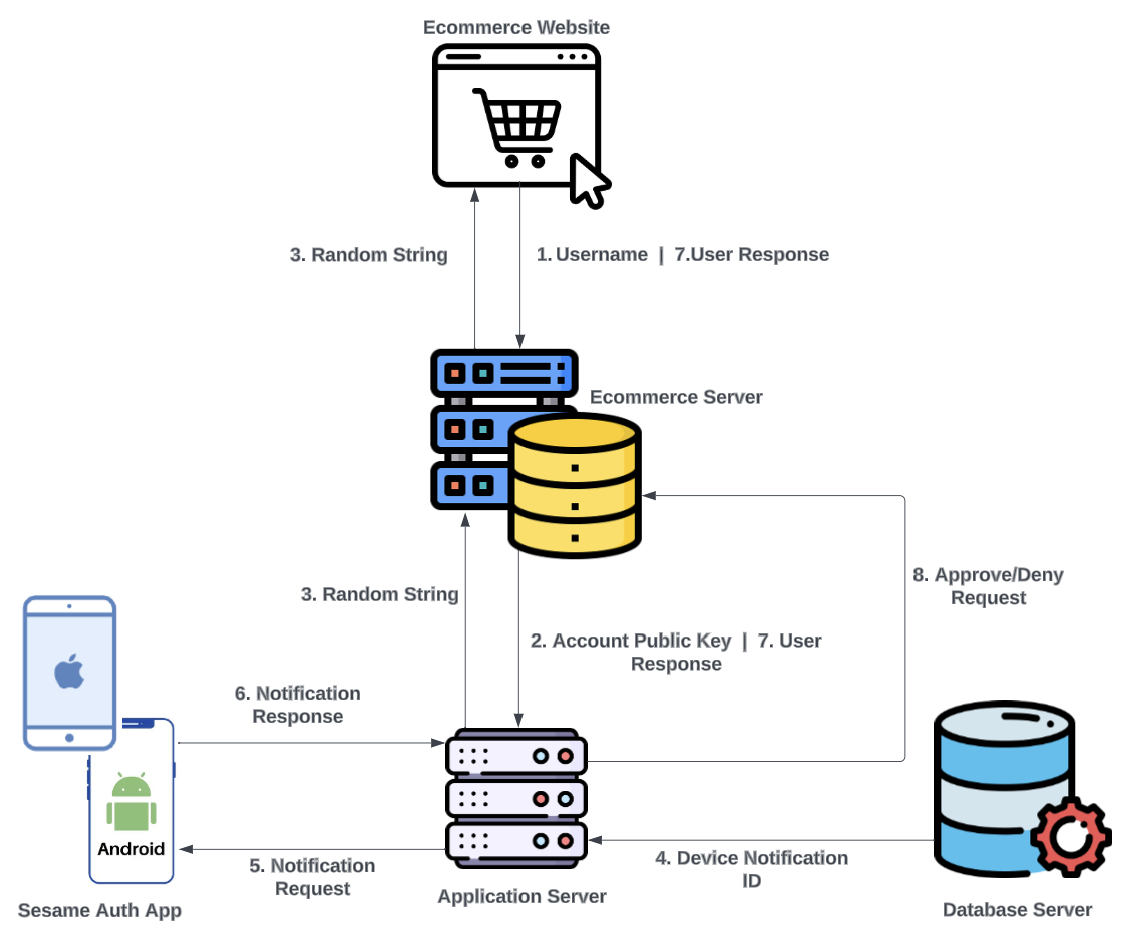

- User visits the Ecom login page and enters their username, which is sent to the Ecom server.

- The Ecom server checks its database to see if the username exists and is associated with a public key. If it exists, the public key for that username is retrieved and sent from the Ecom server to the SA server.

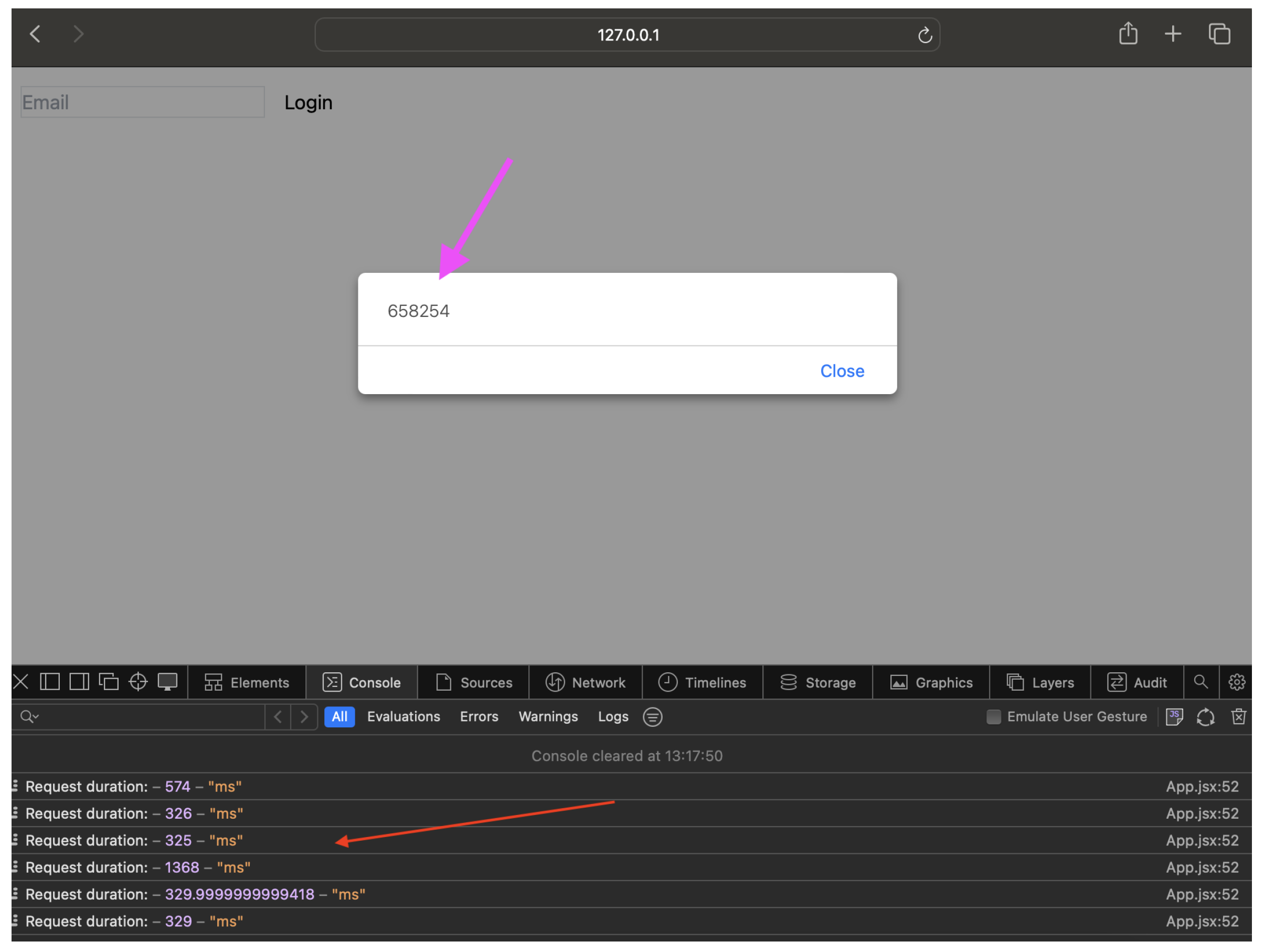

- The SA server generates a random string as an initial response to the Ecom server; the Ecom server will display the string to the user requesting login. As in previous communication, the string is encrypted before it is sent to the Ecom server. Simultaneously, the SA server extracts the DN-ID associated with that account public key and sends a notification to the device.

- The user receives the notification prompt on their device and is requested to enter the random string displayed on the screen where they are requesting login.

- Once the user enters the random string into the provided area in the app, biometric authentication to approve the request is sought, and the response is sent to the SA server.

- The SA server compares the input from the user with the string that was generated; if there is a match, as in Figure 7, the SA server informs the Ecom server that the request can be approved, and the Ecom server handles routing the user to their account. If there is no match, the SA server informs the Ecom server to deny the login request.

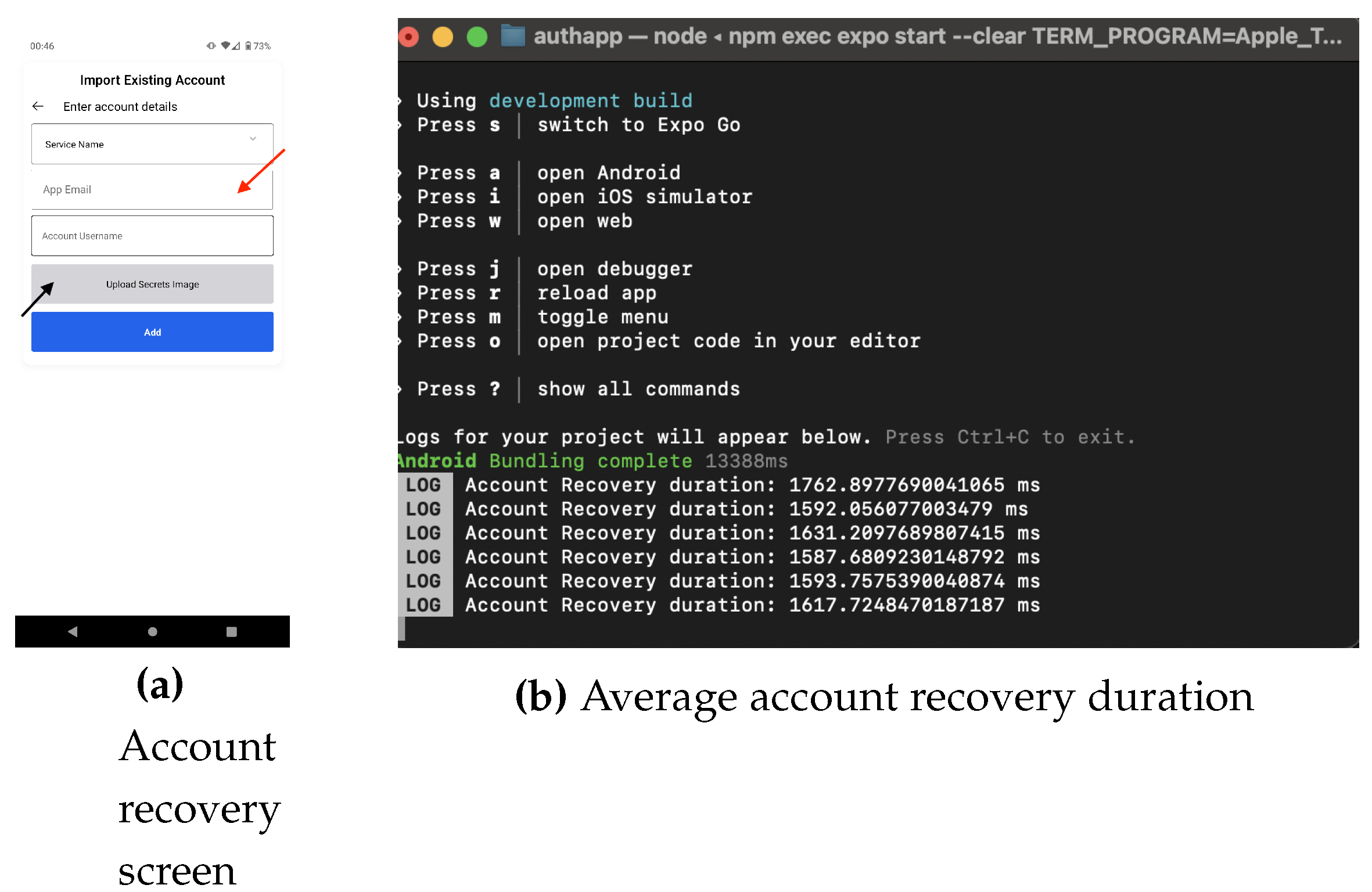

3.3.2. Account Recovery

- User installs the app on a new device and navigates to the account import screen (AIS).

- The user types in their email address in the input field and uploads the stego-image holding the account credentials. The AIS captures the typing pattern of the user in the background while they are typing.

- On biometric authentication success on the device, the typing pattern is encrypted using the server public key (this was received during the app installation), and along with the stego-image is sent to the SA server.

- The SA server confirms that the image contains data for that account after extracting the typing ID and decrypting it, and the public key. The server checks the database for that typing ID, to confirm that a previous relationship existed between the public key and typing ID; if the public key was not previously mapped to the typing ID, the request is rejected. If there was a previous mapping, the typing ID and the typing pattern are encrypted and sent to the TypingDNA server for verification.

- Based on the response from the TypingDNA server as in Figure 8, the account import request will be accepted (assuming there was a match) or rejected.Figure 8. SA Account recovery process

- If there is a match, the user is routed to the accounts list screen, and the imported account is added, allowing the user to authenticate to the account as in Section 3.3.1.

4. Results

4.1. Account Creation

4.2. Authentication

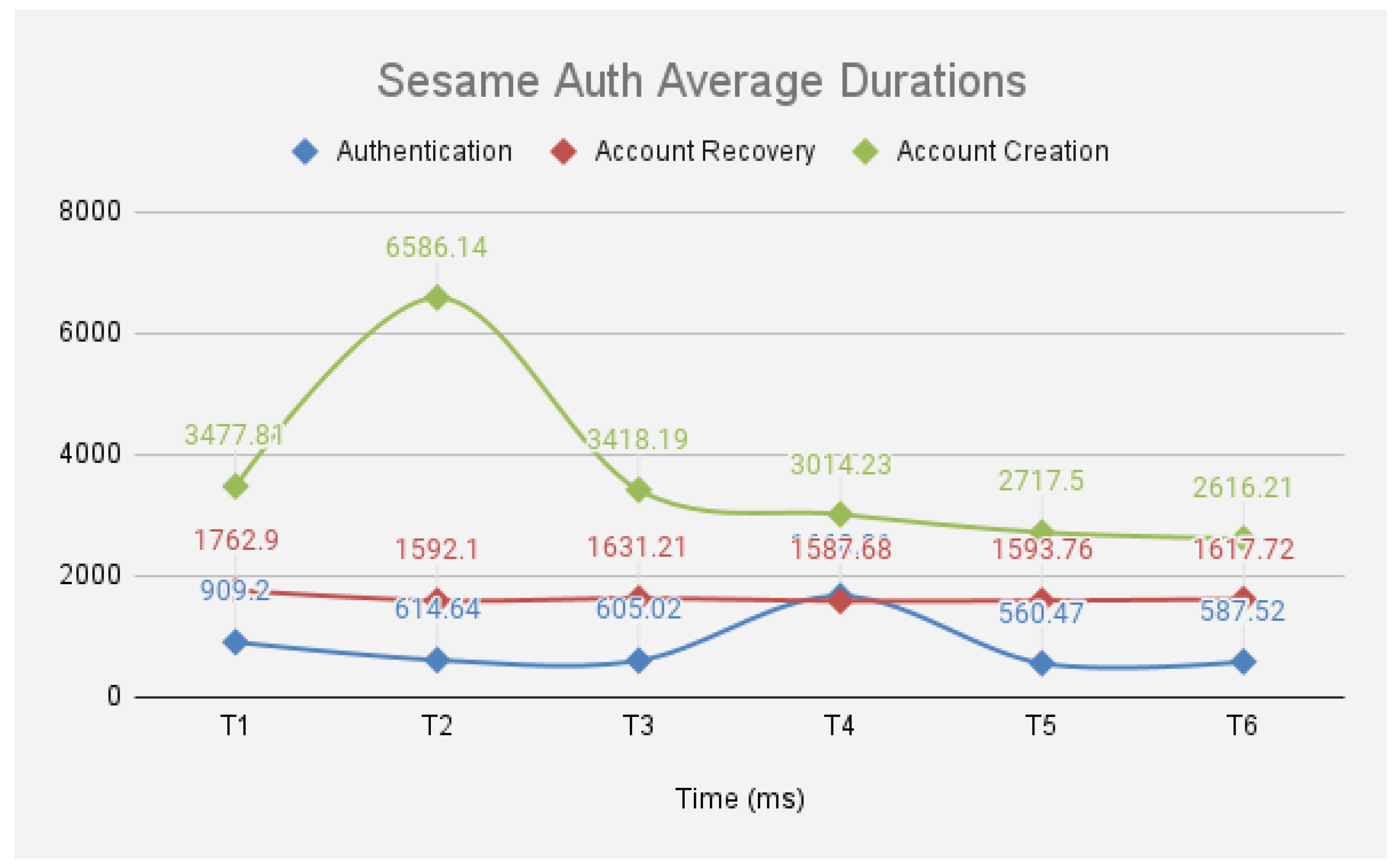

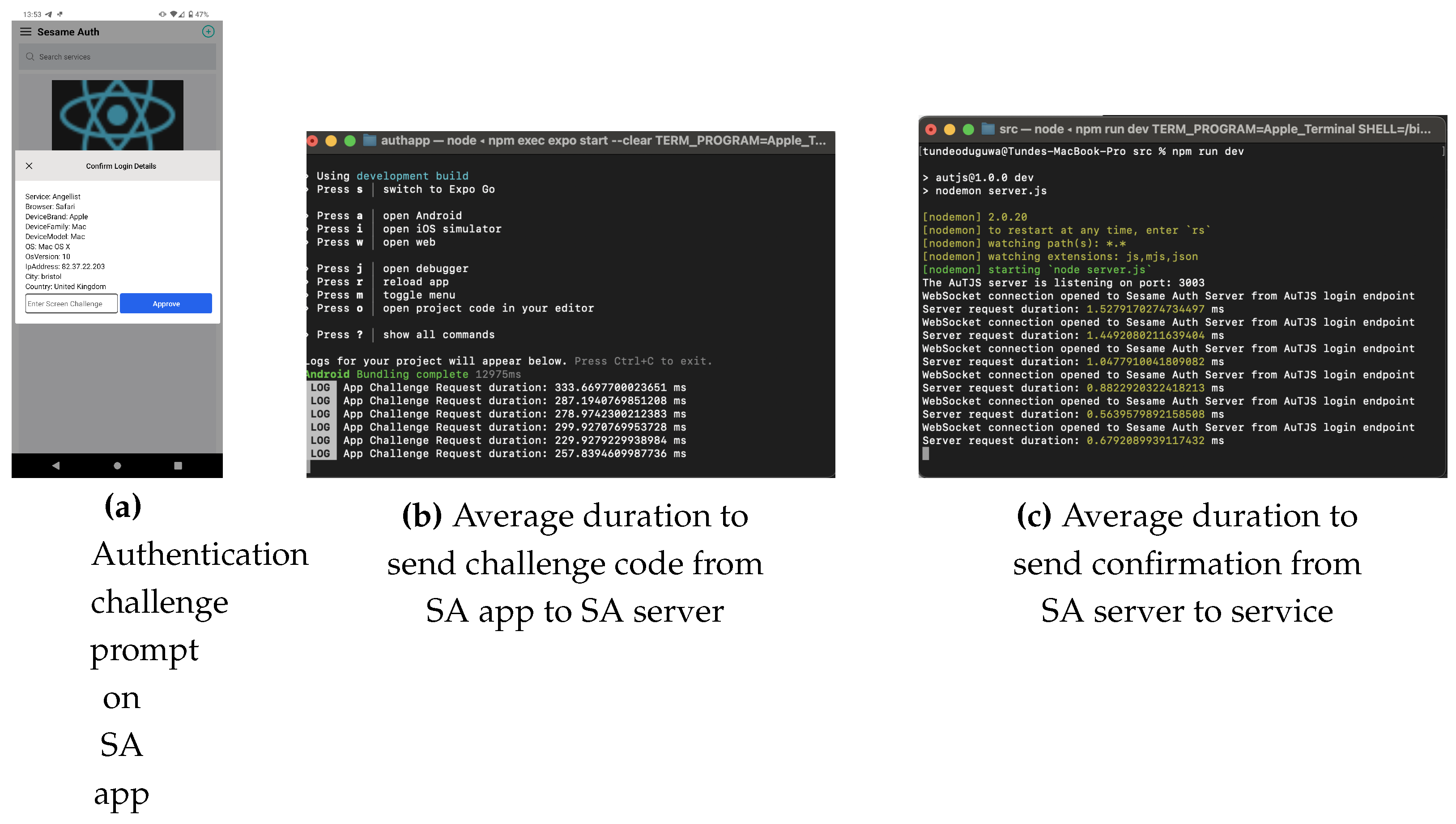

- The time taken to receive the challenge code from the SA server when the login button is clicked averages 543ms, as shown in Figure 11.Figure 10. SA Account Creation Results

Figure 11. Average duration to receive challenge code

Figure 11. Average duration to receive challenge code

- The period between when the user confirms the login details displayed on the app, enters the challenge code on the SA app (Figure 12a), provides biometric authentication, and is routed to their account; once the user enters the challenge code, it is sent from the SA app to the SA server for confirmation. A response is then sent from the SA server to the service to either approve or reject the user’s login request. The duration averaged 282ms. Summing the average server times, the total time to complete an authentication session was 825 ms. Further, success rates of 100 percent were recorded for each authentication session.

4.3. Account Recovery

4.4. Registration

5. Evaluation and Discussion

| Framework Benefit | Sesame Auth (SA) |

|---|---|

| Memory Wise-Effortless | Account credentials are stored on the device and the user does not have to remember secrets. |

| Scalable-for-Users | SA can handle hundreds of accounts without any cognitive load on the user. |

| Nothing-to-Carry | SA depends on an existing owned device and does not require the purchase of new hardware. |

| Physically-Effortless | The authentication process requires typing in a challenge code, ranking it low on this benefit. |

| Easy-to-Learn | Users can quickly learn to use SA as it is designed to work as a regular mobile app. |

| Efficient-to-Use | Account creation and authentication times aggregated are under 4 seconds, making it acceptably short. |

| Infrequent-Errors | Login is dependent on supplying the exact challenge code generated by the SA server and providing biometric authentication on the device. Therefore, there are no errors if these criteria are satisfied. |

| Easy-Recovery-from-Loss | Account recovery simply involves uploading an image and typing in an email address, making it this benefit high. |

| Framework Benefit | Sesame Auth (SA) |

|---|---|

| Accessible, | A user who can use passwords can also use SA. |

| Negligible-Cost-per-User | There is some negligible-fixed cost incurred in implementing SA. |

| Server-Compatible | SA is compatible with text-based passwords; the server simply swaps out the authentication logic. |

| Browser-Compatible | SA is browser-agnostic as users do not need to install any browser plugins/software for it to be compatible. |

| Mature | SA is a proof-of-concept; it has not yet been deployed on a large scale. Therefore, it is low on this benefit. |

| Non-Proprietary | SA is proprietary, as implementers have to pay some negligible royalty. |

| Framework Benefit | Sesame Auth (SA) |

|---|---|

| Resilient-to-Physical-Observation, | An attacker cannot impersonate the user by physically observing them during authentication using SA. |

| Resilient-to-Targeted-Impersonation | An attacker cannot impersonate the user on SA by having any knowledge of the user’s personal data. |

| Resilient-to-Throttled-Guessing | In a rate-limited scenario, an attacker cannot guess the 2048-bit RSA private keys for SA. Further, the challenge code is a cryptographic pseudo-random number that has a 1:1000,000 relationship. |

| Resilient-to-Unthrottled-Guessing | Constrained only by computing resources, it is computationally infeasible to guess 2048-bit RSA keys. Further, the attacker would need physical access to the user’s device, making SA high on this benefit. |

| Framework Benefit | Sesame Auth (SA) |

|---|---|

| Resilient-to-Internal-Observation | All communications are encrypted, therefore an attacker cannot impersonate a user by observing network traffic. Further, SA cryptographic keys are stored in the devices’ secure area isolated from the rest of the system, making them resistant to malware on the device. |

| Resilient-to-Leaks-from-Other-Verifiers | An attacker cannot impersonate the user due to data breaches at the service, as the service stores usernames and public keys rather than secrets. |

| Resilient-to-Phishing | Since no secrets are shared between the SA server and service, it is resilient to phishing as an attacker can only harvest publicly available data from a phishing campaign. |

| Resilient-to-Theft | Where the user’s device is stolen, an attacker cannot access the account as biometric authentication is required to complete login. |

| No-Trusted-Third-Party | Compromise of the SA server can lead to user impersonation, as malicious data is sent to the service, therefore it is low on this benefit. |

| Requiring-Explicit-Consent | Authentication cannot be done without the user’s consent and knowledge, making it resistant to MFA fatigue. |

| Unlinkable | The user’s privacy is preserved as each account has a unique keypair, making this benefit high. |

5.1. Threat Analysis and Mitigation

- Phishing (user visits the fraudulent representation of a listed service) - SA does not involve shared secrets; therefore, users can only provide public usernames, which alone do not provide access to the account.

- Malware on user device - Secret keys are stored in the trusted execution environment (TEE) of the device and are as secure as the strength of the device TEE implementation.

- MITM during initial registration - Certificate authorities provide digital signatures for the SA app and server public keys.

- Malicious version of the SA app - The malicious app is unable to communicate with the true SA server and, therefore, cannot impersonate the user.

- SA server database attack - The SA server only stores public keys, while private keys are stored in environment variables, therefore account impersonation is prevented. However, if the database is modified, it might lead to a denial of service for users.

- Real-time MITM attacks - All communications between the SA app and server, and between SA and the service (e.g. Facebook) are end-to-end encrypted over HTTPS.

- Keylogging - No secrets are entered into the app during its operation; therefore, this does not yield any data for attackers to impersonate the user.

5.2. Limitations

5.2.1. LSB Steganography

5.2.2. Cryptography in Mobile Environments

5.2.3. SA server as a Trusted Third-party

6. Conclusions

References

- Oduguwa, T.; Arabo, A. A Review of Password-less User Authentication Schemes, 2023, [arxiv:cs/2312.02845]. Comment: 6 pages, submitted to Internet Technology Letters, 6: Comment. [CrossRef]

- Bonneau, J.; Herley, C.; van Oorschot, P.C.; Stajano, F. The Quest to Replace Passwords: A Framework for Comparative Evaluation of Web Authentication Schemes. 2012 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, 2012, pp. 553–567. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, C.; Kulkarni, S.; Shelar, S.; Shinde, K.; Dharwadkar, N.V. Biometric Authentication Using Keystroke Dynamics. 2017 International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC). IEEE: Palladam, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Conners, J.; Devenport, C.; Derbidge, S.; Farnsworth, N.; Gates, K.; Lambert, S.; McClain, C.; Nichols, P.; Zappala, D. Let’s Authenticate: Automated Certificates for User Authentication. Proceedings 2022 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium. Internet Society: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenman, B. Learning React Native : Building Mobile Applications with JavaScript., first edition. ed.; Beijing, China : O’Reilly, 2016.

- Teh, P.S.; Teoh, A.B.J.; Yue, S. A Survey of Keystroke Dynamics Biometrics. The Scientific World Journal 2013, 2013, e408280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TypingDNA. About Us - TypingDNA. https://www.typingdna.com/about.

- Node.Js — About Node.Js®. https://nodejs.org/en/about.

- Encrypt, L. Let’s Encrypt. https://letsencrypt.org/.

- Node.js. Crypto | Node.Js V21.2.0 Documentation. https://nodejs.org/api/crypto.html.

- amitaymolko. React-Native-Rsa-Native, 2017.

- entronad. CryptoES. https://www.npmjs.com/package/crypto-es, 2022.

- Expo. Send Notifications with FCM & APNs. https://docs.expo.dev/push-notifications/sending-notifications-custom.

- Google. Android Keystore System | App Quality. https://developer.android.com/privacy-and-security/keystore.

- Apple. Keychain Services. https://developer.apple.com/documentation/security/keychain_services.

- TypingDNA. API Documentation - TypingDNA. https://api.typingdna.com/docs/index.html#api-API_Services-Advanced-saveUserPattern.

- Taha, M.S.; Rahim, M.S.M.; Lafta, S.A.; Hashim, M.M.; Hassanain, M.A. Combination of Steganography and Cryptography: A Short Survey. IOP Conference Series. Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimp. Jimp. https://www.npmjs.com/package/jimp, 2023.

- Jebur, S.A.; Nawar, A.K.; Kadhim, L.E.; Jahefer, M.M. Hiding Information in Digital Images Using LSB Steganography Technique. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM) 2023, 17, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Zepernick, H.J.; Chu, T. LSB Data Hiding in Digital Media: A Survey. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Industrial Networks and Intelligent Systems 2022, p. 173783. [CrossRef]

- Stark, E.; Hamburg, M.; Boneh, D. Symmetric Cryptography in Javascript. 2009 Annual Computer Security Applications Conference; IEEE: Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, 2009; pp. 373–381. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).