Submitted:

19 January 2024

Posted:

19 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

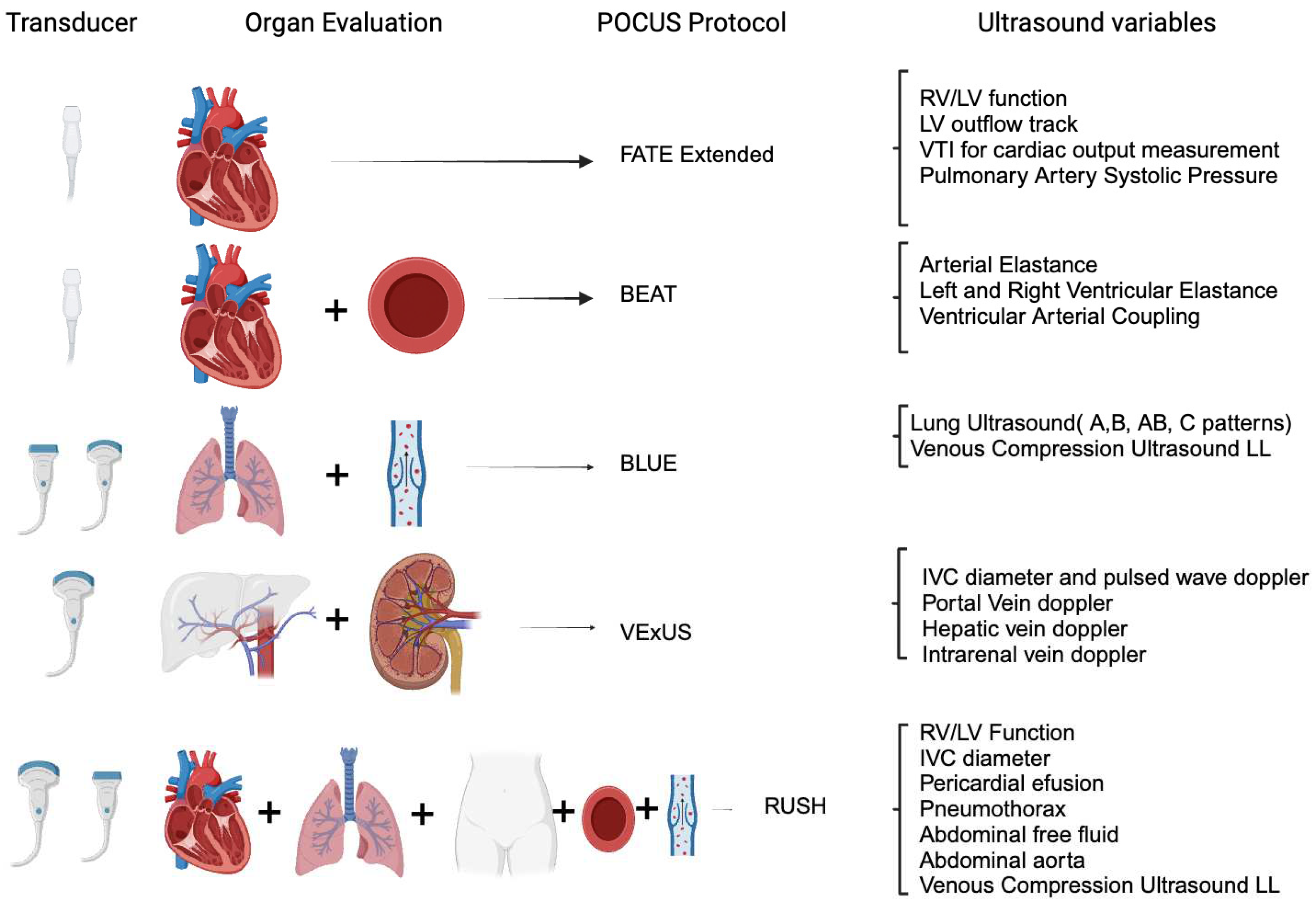

- The Use of Point-of-Care Ultrasound in the Field of Acute Care Nephrology

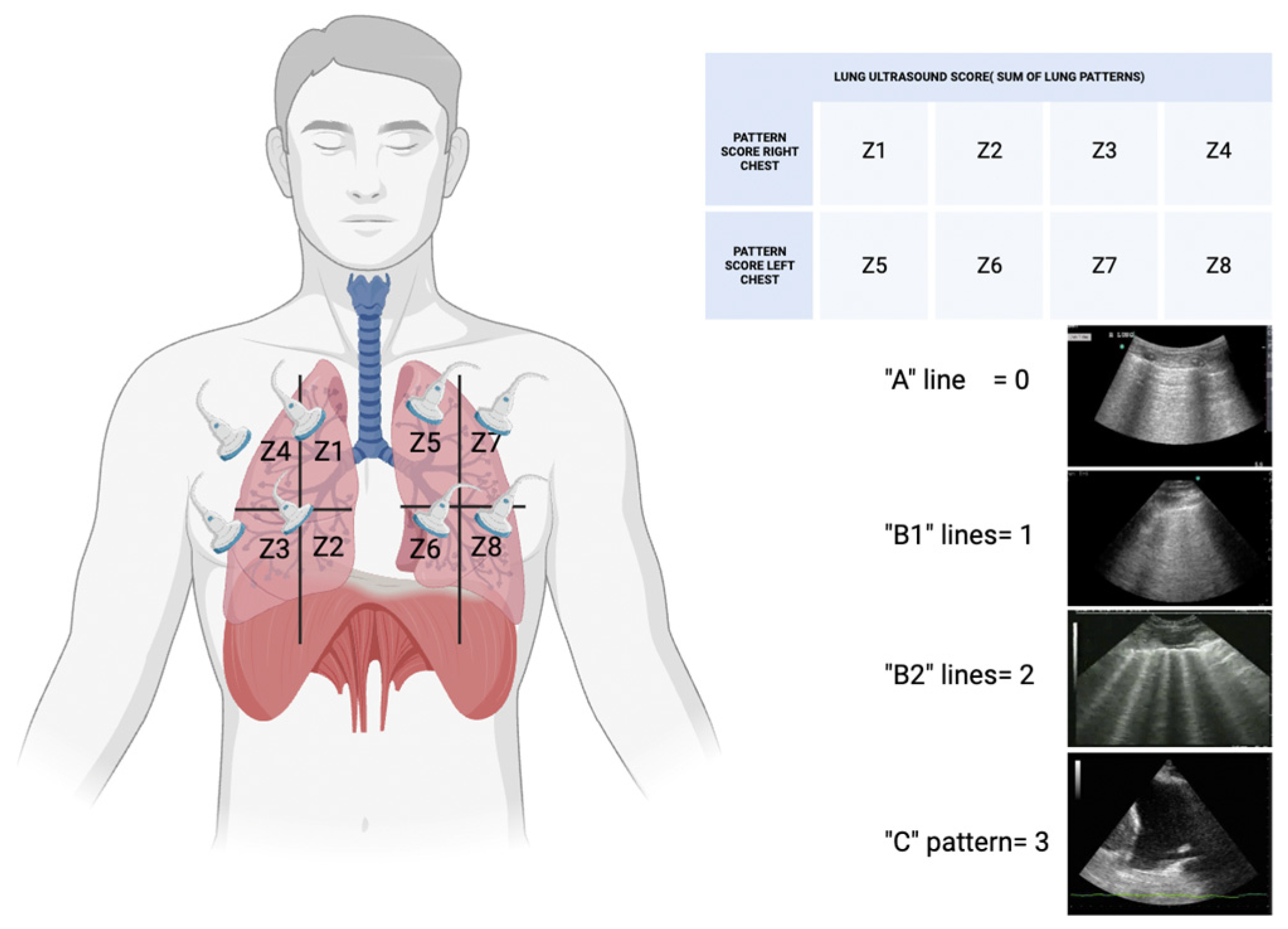

- Lung Ultrasonography for Nephrologists

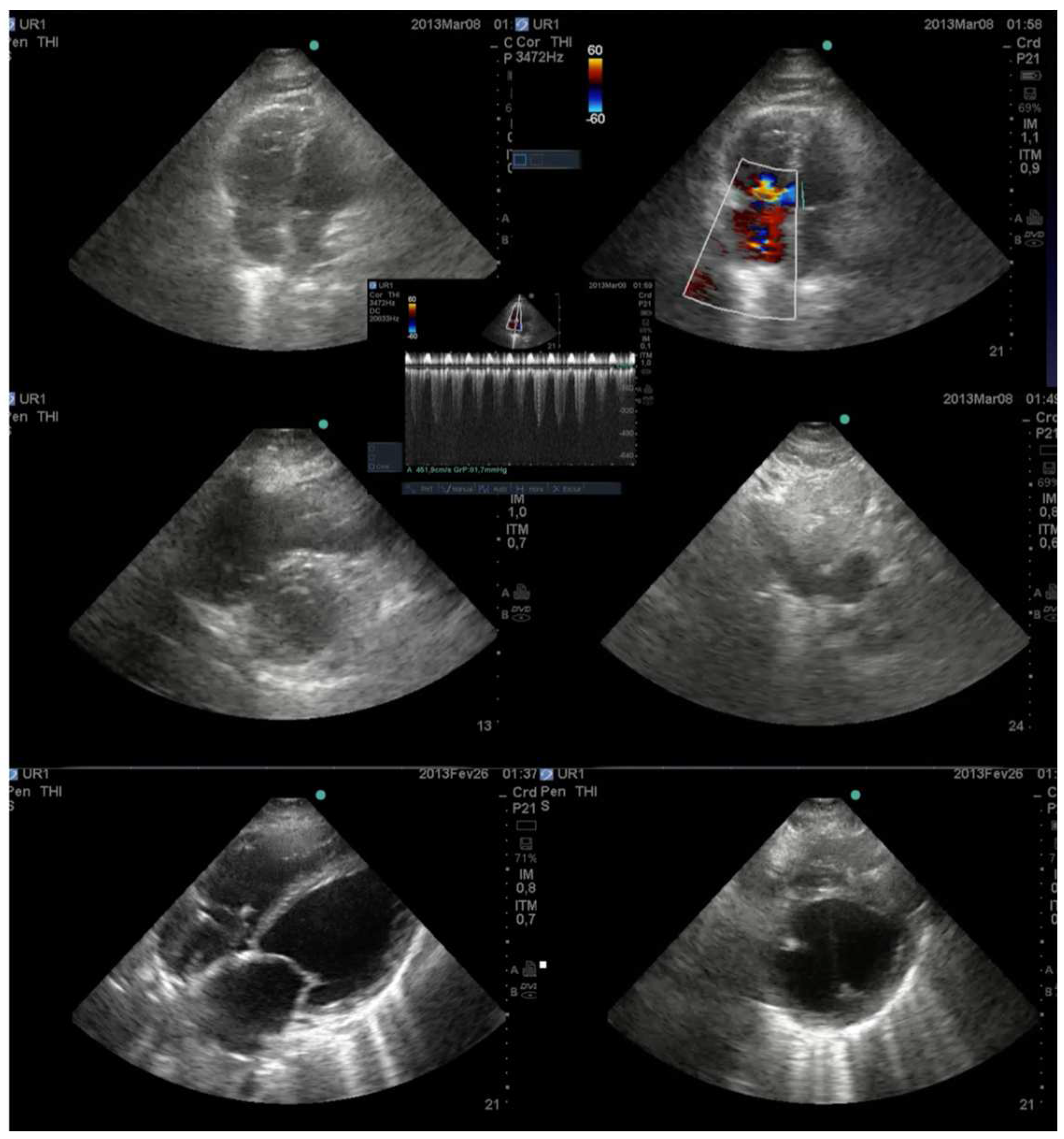

- Cardiac Ultrasonography for Nephrologists

- Abdominal Ultrasonography for Nephrologists

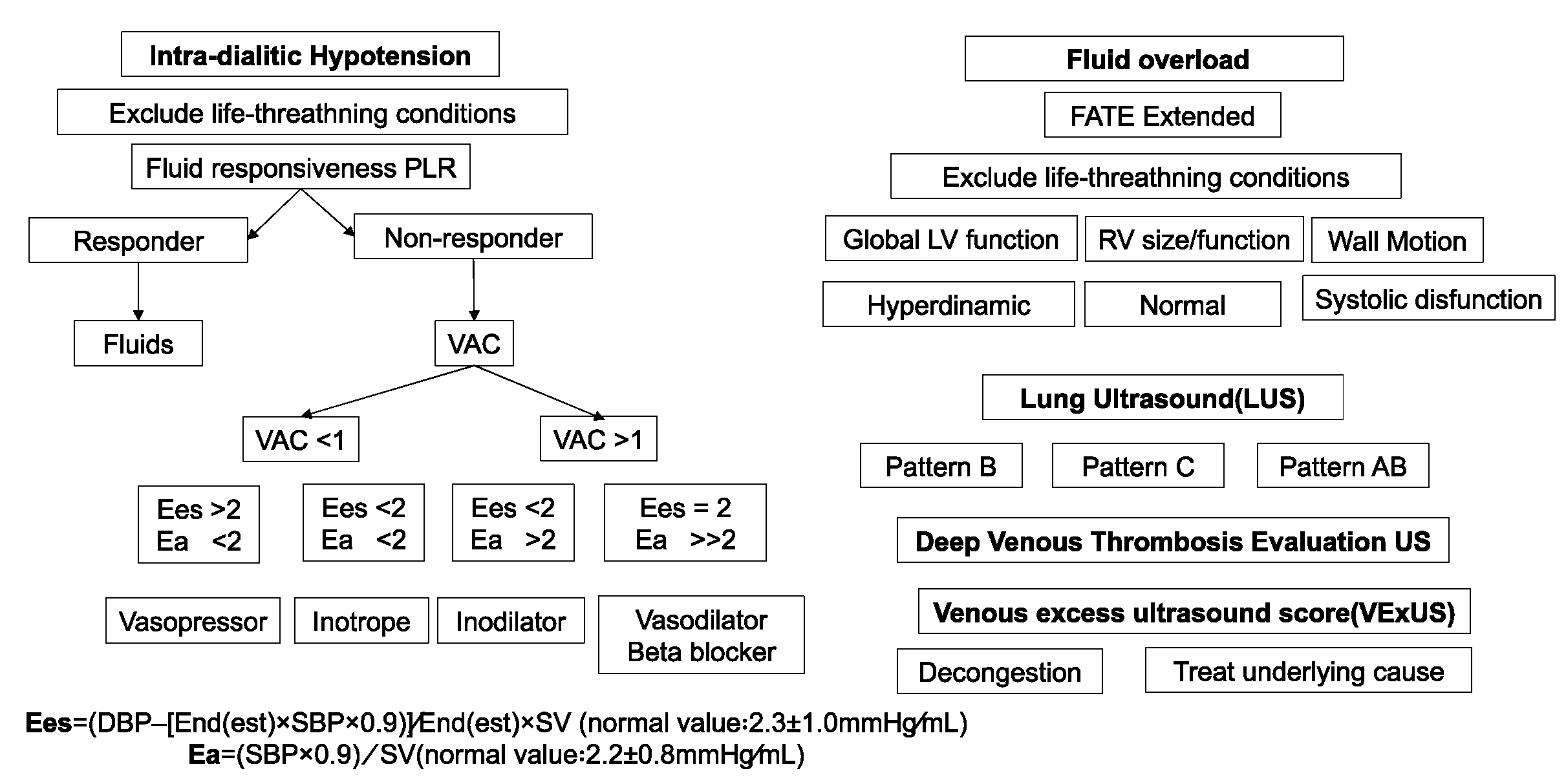

- POCUS in Hemodynamic Instability during Acute Kidney Injury and Acute Renal Replacement Therapy

- 1)

- Pre-Load Dependence and POCUS

- 2)

- Ventricule arterial Couplling and POCUS

- 3)

- Myocardial function and POCUS

- 4)

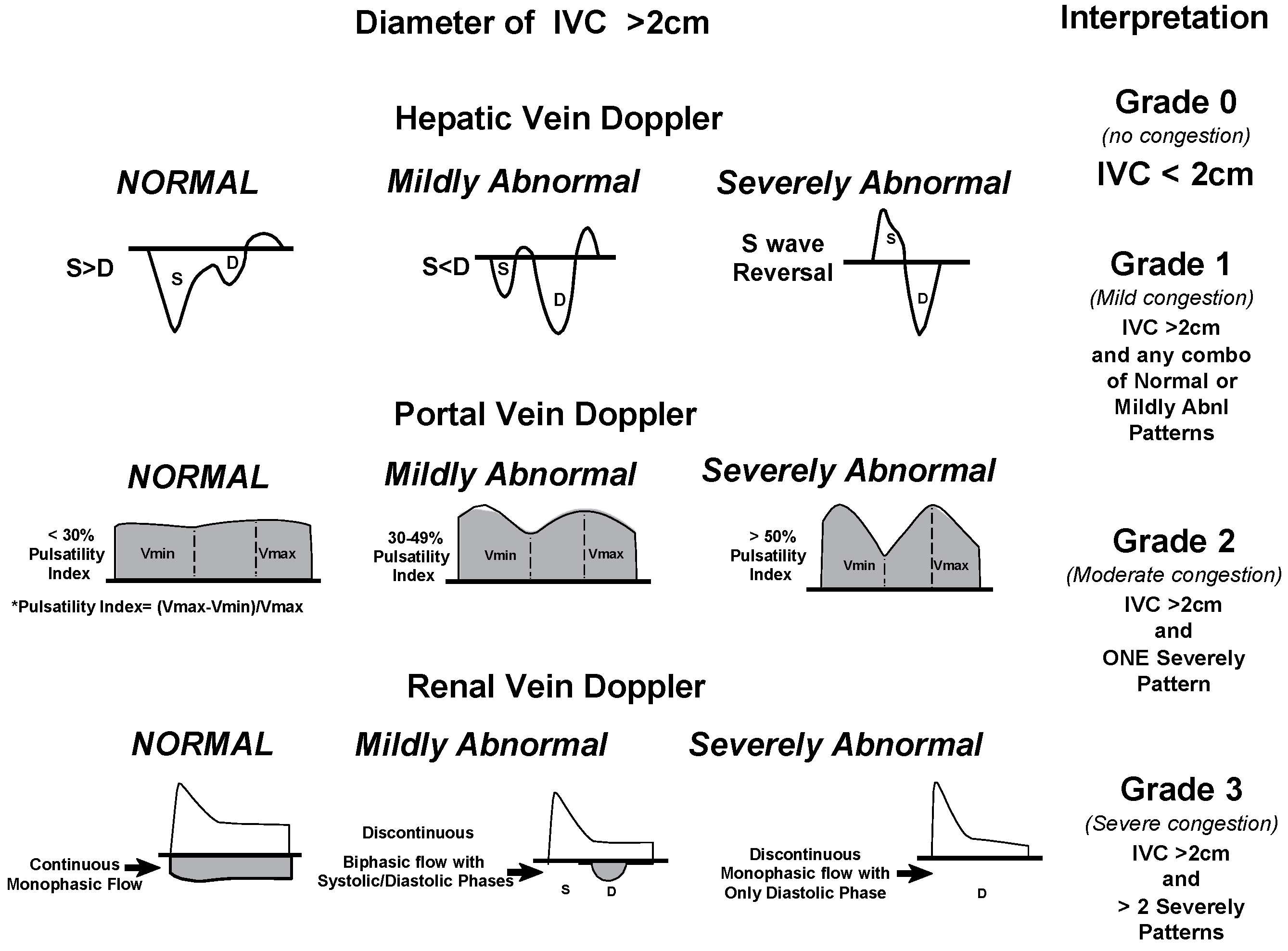

- Systemic venous congestion and POCUS

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vanholder, R.; Annemans, L.; Braks, M.; Brown, E.A.; Pais, P.; Purnell, T.S.; Sawhney, S.; Scholes-Robertson, N.; Stengel, B.; Tannor, E.K.; et al. Inequities in kidney health and kidney care. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19, 694–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, B.R.; Liu, K.D.; Teixeira, J.P. Critical Care Nephrology: Core Curriculum 2020. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleeson, P.J.; Crippa, I.A.; Sannier, A.; Koopmansch, C.; Bienfait, L.; Allard, J.; Sexton, D.J.; Fontana, V.; Rorive, S.; Vincent, J.-L.; et al. Critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: clinical determinants and post-mortem histology. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 1664–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, A.B.; Vehbi, S.; Covic, A.; Burlacu, A.; Covic, A.; Kanbay, M. An update review on hemodynamic instability in renal replacement therapy patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2022, 55, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanbay, M.; A Ertuglu, L.; Afsar, B.; Ozdogan, E.; Siriopol, D.; Covic, A.; Basile, C.; Ortiz, A. An update review of intradialytic hypotension: concept, risk factors, clinical implications and management. Clin. Kidney J. 2020, 13, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, E.; Karl, B.; Lee, E.; Mehta, R.L. A randomized trial of albumin infusion to prevent intradialytic hypotension in hospitalized hypoalbuminemic patients. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.I. Impact of drugs on intradialytic hypotension: Antihypertensives and vasoconstrictors. Semin. Dial. 2017, 30, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyckoff, M.H.; Greif, R.; Morley, P.T.; Ng, K.-C.; Olasveengen, T.M.; Singletary, E.M.; Soar, J.; Cheng, A.; Drennan, I.R.; Liley, H.G.; et al. 2022 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations: Summary From the Basic Life Support; Advanced Life Support; Pediatric Life Support; Neonatal Life Support; Education, Implementation, and Teams; and First Aid Task Forces. Circulation 2022, 146, E483–E557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, A.; Chaudhry, S.; Koratala, A. Transcending boundaries: Unleashing the potential of multi-organ point-of-care ultrasound in acute kidney injury. World J. Nephrol. 2023, 12, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saray, M.Z.; Ali, A. Lung Ultrasound and Caval Indices to Assess Volume Status in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. POCUS J. 2023, 8, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-González, G.; Manrique, J.; Slon-Roblero, M.F.; Husain-Syed, F.; De la Espriella, R.; Ferrari, F.; Bover, J.; Ortiz, A.; Ronco, C. PoCUS in nephrology: a new tool to improve our diagnostic skills. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 16, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore CA, Ross DW, Pivert KA, Lang VJ, Sozio SM, Charles O’Neill W. Point-of-Care Ultrasound Training during Nephrology Fellowship A National Survey of Fellows and Program Directors. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2022, 17.

- Reisinger, N.K.A. Current opinion in quantitative lung ultrasound for the nephrologist. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2023; 32, 509–514. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, S.; Krallman, K.A.; Fuhrman, D.Y.; Gorga, S.M.; Ricci, Z.; Stanski, N.L.; Selewski, D.T.; Soranno, D.E.; Zappitelli, M.; Zang, H.; et al. Worldwide Exploration of Renal Replacement Outcomes Collaborative in Kidney Disease (WE-ROCK). Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 1542–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayen, S.; Kim, J.S.; Desai, P. Pulmonary Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in the Intensive Care Unit. AACN Adv. Crit. Care 2023, 34, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpicelli, G.; Gargani, L. A simple, reproducible and accurate lung ultrasound technique for COVID-19: when less is more. Intensiv. Care Med. 2021, 47, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picano, E.; Frassi, F.; Agricola, E.; Gligorova, S.; Gargani, L.; Mottola, G. Ultrasound Lung Comets: A Clinically Useful Sign of Extravascular Lung Water. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2006, 19, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, U.; Lukas, M.; Habenicht, L.; Wiessner, J.; Heilmaier, M.; Ulrich, J.; Rasch, S.; Schmid, R.M.; Lahmer, T.; Huber, W.; et al. B-Lines Scores Derived From Lung Ultrasound Provide Accurate Prediction of Extravascular Lung Water Index: An Observational Study in Critically Ill Patients. J. Intensiv. Care Med. 2020, 37, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubic, N.; Belliveau, D.J.; Herr, J.E.; Nihal, S.; Wong, S.W.S.; Lam, J.; Gauthier, S.; Montague, S.J.; Durbin, J.; Mulvagh, S.L.; et al. Training of Non-expert Users Using Remotely Delivered, Point-of-Care Tele-Ultrasound: A Proof-of-Concept Study in 2 Canadian Communities. Ultrasound Q. 2023, 39, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamani, A.; Galarza, L.; Sanfilippo, F.; Wong, A.; Goffi, A.; Tuinman, P.; Mayo, P.; Arntfield, R.; Fisher, R.; Chew, M.; et al. Criteria, Processes, and Determination of Competence in Basic Critical Care Echocardiography Training: A Delphi Process Consensus Statement by the Learning Ultrasound in Critical Care (LUCC) Initiative. Chest 2022, 161, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Yoshida, T.; Noma, H.; Nomura, T.; Suzuki, A.; Mihara, T. Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound for shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaseem, A.; Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta, I.; Mustafa, R.A.; Kansagara, D.; Fitterman, N.; Wilt, T.J.; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians; Batur, P.; Cooney, T.G.; Crandall, C.J.; et al. Appropriate Use of Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in Patients with Acute Dyspnea in Emergency Department or Inpatient Settings: A Clinical Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, S.; Koratala, A. Assessment of venous congestion by Doppler ultrasound: a valuable bedside diagnostic tool for the new-age nephrologist. CEN Case Rep. 2020, 10, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Via, G.; Tavazzi, G.; Price, S. Ten situations where inferior vena cava ultrasound may fail to accurately predict fluid responsiveness: a physiologically based point of view. Intensiv. Care Med. 2016, 42, 1164–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koratala, A.; Reisinger, N. Venous Excess Doppler Ultrasound for the Nephrologist: Pearls and Pitfalls. Kidney Med. 2022, 4, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, D.W.; A Moses, A.; Niyyar, V.D. Point-of-care ultrasonography in nephrology comes of age. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 2220–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhija N, Magoon R, Das D, Saxena A. Haemodynamic predisposition to acute kidney injury: Shadow and light! Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology 2022, 38, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledoux-Hutchinson, L.; Wald, R.; Malbrain, M.L.N.G.; Carrier, F.M.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Bellomo, R.; Adhikari, N.K.J.; Gallagher, M.; Silver, S.A.; Bouchard, J.; et al. Fluid Management for Critically Ill Patients with Acute Kidney Injury Receiving Kidney Replacement Therapy: An International Survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023, 18, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.; Abdallah, T.; Abdelsalam, H.; Mokhtar, A.; Razek, A.A. Evaluation of parameters used in echocardiography and ultrasound protocol for the diagnosis of shock etiology in emergency setting. BMC Emerg. Med. 2023, 23, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Backer D, Aissaoui N, Cecconi M, Chew MS, Denault A, Hajjar L, et al. How can assessing hemodynamics help to assess volume status? Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 1482–1494. [CrossRef]

- Winning, J.; A Claus, R.; Huse, K.; Bauer, M. Molecular biology on the ICU. From understanding to treating sepsis. Minerva Anestesiologica 2006, 72, 255–67. [Google Scholar]

- Spano, S.; Maeda, A.; Lam, J.; Chaba, A.; See, E.; Mount, P.; Nichols-Boyd, M.; Bellomo, R. Cardiac Output Changes during Renal Replacement Therapy: A Scoping Review. Blood Purif. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schotola, H.; Sossalla, S.T.; Renner, A.; Gummert, J.; Danner, B.C.; Schott, P.; Toischer, K. The contractile adaption to preload depends on the amount of afterload. ESC Hear. Fail. 2017, 4, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, S.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, S. Associations between central pulse pressure, microvascular endothelial function, and fluid overload in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2023, 45, 2267192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, I.; Castro, V.O.; Sosa, F.A.; Oribe, B.T.; Früchtenicht, M.F.; Tamagnone, F.M.; Merlo, P.M. Passive leg raising test using the carotid flow velocity–time integral to predict fluid responsiveness. J. Ultrasound 2023, 27, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nicolò, P.; Tavazzi, G.; Nannoni, L.; Corradi, F. Inferior Vena Cava Ultrasonography for Volume Status Evaluation: An Intriguing Promise Never Fulfilled. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, M.-L.; Chen, Q.-Y.; Pu, L.; Shi, L.; Wu, D.; Li, H.; Luo, X.; Yin, L.-X.; Siu, C.-W.; Hong, D.-Q.; et al. Impact of Hemodialysis on Left Ventricular-Arterial Coupling in End-Stage Renal Disease Patients. Blood Purif. 2023, 52, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Taberner, A.J.; Loiselle, D.S.; Tran, K. Cardiac efficiency and Starling's Law of the Heart. J. Physiol. 2022, 600, 4265–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suga, H. Time Course of Left Ventricular Pressure-Volume Relationship under Various Enddiastolic Volume. Jpn. Hear. J. 1969, 10, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, M. Echocardiography assessment of right ventricular-pulmonary artery coupling: Validation of surrogates and clinical utilities. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 394, 131358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonomidis I, Aboyans V, Blacher J, Brodmann M, Brutsaert DL, Chirinos JA, et al. The role of ventricular–arterial coupling in cardiac disease and heart failure: assessment, clinical implications and therapeutic interventions. A consensus document of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Aorta & Peripheral Vascular Diseases, European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging, and Heart Failure Association. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 402–424.

- Lebeau, R.; Robert-Halabi, M.; Pichette, M.; Vinet, A.; Sauvé, C.; Dilorenzo, M.; Le, V.; Piette, E.; Brunet, M.; Bédard, W.; et al. Left ventricular ejection fraction using a simplified wall motion score based on mid-parasternal short axis and apical four-chamber views for non-cardiologists. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schick, A.L.; Kaine, J.C.; Al-Sadhan, N.A.; Lin, T.; Baird, J.; Bahit, K.; Dwyer, K.H. Focused cardiac ultrasound with mitral annular plane systolic excursion (MAPSE) detection of left ventricular dysfunction. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 68, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhrasta, S.; Raafat, M.H.; Conti, R.A. Reliability of focused cardiac ultrasound performed by first-year internal medicine residents at a community hospital after a short training. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2019, 9, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod P, Beck S. Update on echocardiography: do we still need a stethoscope? Intern Med J. 2022, 52, 30–36. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, J.N.; Swaminathan, M.; Adedipe, A.; Garcia-Sayan, E.; Hung, J.; Kelly, N.; Kort, S.; Nagueh, S.; Poh, K.K.; Sarwal, A.; et al. American Society of Echocardiography COVID-19 Statement Update: Lessons Learned and Preparation for Future Pandemics. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2023, 36, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobal, S.L.; Trento, L.; Baharami, S.; Tolstrup, K.; Naqvi, T.Z.; Cercek, B.; Neuman, Y.; Mirocha, J.; Kar, S.; Forrester, J.S.; et al. Comparison of Effectiveness of Hand-Carried Ultrasound to Bedside Cardiovascular Physical Examination. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin LD, Howell EE, Ziegelstein RC, Martire C, Whiting-O’Keefe QE, Shapiro EP, et al. Hand-carried Ultrasound Performed by Hospitalists: Does It Improve the Cardiac Physical Examination? Am J Med. 2009, 122, 35–41. [CrossRef]

- Banjade, P.; Subedi, A.; Ghamande, S.; Surani, S.; Sharma, M. Systemic Venous Congestion Reviewed. Cureus 2023, 15, e43716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattan E, Castro R, Miralles-Aguiar F, Hernández G, Rola P. The emerging concept of fluid tolerance: A position paper. J Crit Care. 2022, 71, 154070.

- Rihl MF, Pellegrini JAS, Boniatti MM. VExUS Score in the Management of Patients With Acute Kidney Injury in the Intensive Care Unit: AKIVEX Study. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 2023; 42, 2547–2556.

- Bhardwaj, V.; Vikneswaran, G.; Rola, P.; Raju, S.; Bhat, R.S.; Jayakumar, A.; Alva, A. Combination of Inferior Vena Cava Diameter, Hepatic Venous Flow, and Portal Vein Pulsatility Index: Venous Excess Ultrasound Score (VEXUS Score) in Predicting Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with Cardiorenal Syndrome: A Prospective Cohort Study. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana-Rojas, J.A.; Argaiz, E.; Robles-Ledesma, M.; Arias-Mendoza, A.; Nájera-Rojas, N.A.; Alonso-Bringas, A.P.; Ríos-Arce, L.F.D.L.; Armenta-Rodriguez, J.; Gopar-Nieto, R.; la Cruz, J.L.B.-D.; et al. Venous excess ultrasound score and acute kidney injury in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur. Hear. Journal. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2023, 12, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-T.; Liu, D.-W.; Zhang, H.-M.; Chai, W.-Z.; Du, W.; He, H.-W.; Liu, Y. [Impact of extended focus assessed transthoracic echocardiography protocol in septic shock patients]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2011, 91, 1879–1883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guarracino, F.; Bertini, P.; Pinsky, M.R. Management of cardiovascular insufficiency in ICU: the BEAT approach. Minerva Anestesiol. 2021, 87, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, D.A.; Mezière, G.A. Relevance of Lung Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Acute Respiratory Failure*: The BLUE Protocol. Chest 2008, 134, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Rola, P.; Haycock, K.; Bouchard, J.; Lamarche, Y.; Spiegel, R.; Denault, A.Y. Quantifying systemic congestion with Point-Of-Care ultrasound: development of the venous excess ultrasound grading system. Ultrasound J. 2020, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Volpicelli, G.; Mussa, A.; Garofalo, G.; Cardinale, L.; Casoli, G.; Perotto, F.; Fava, C.; Frascisco, M. Bedside lung ultrasound in the assessment of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2006, 24, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).