Submitted:

18 January 2024

Posted:

19 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

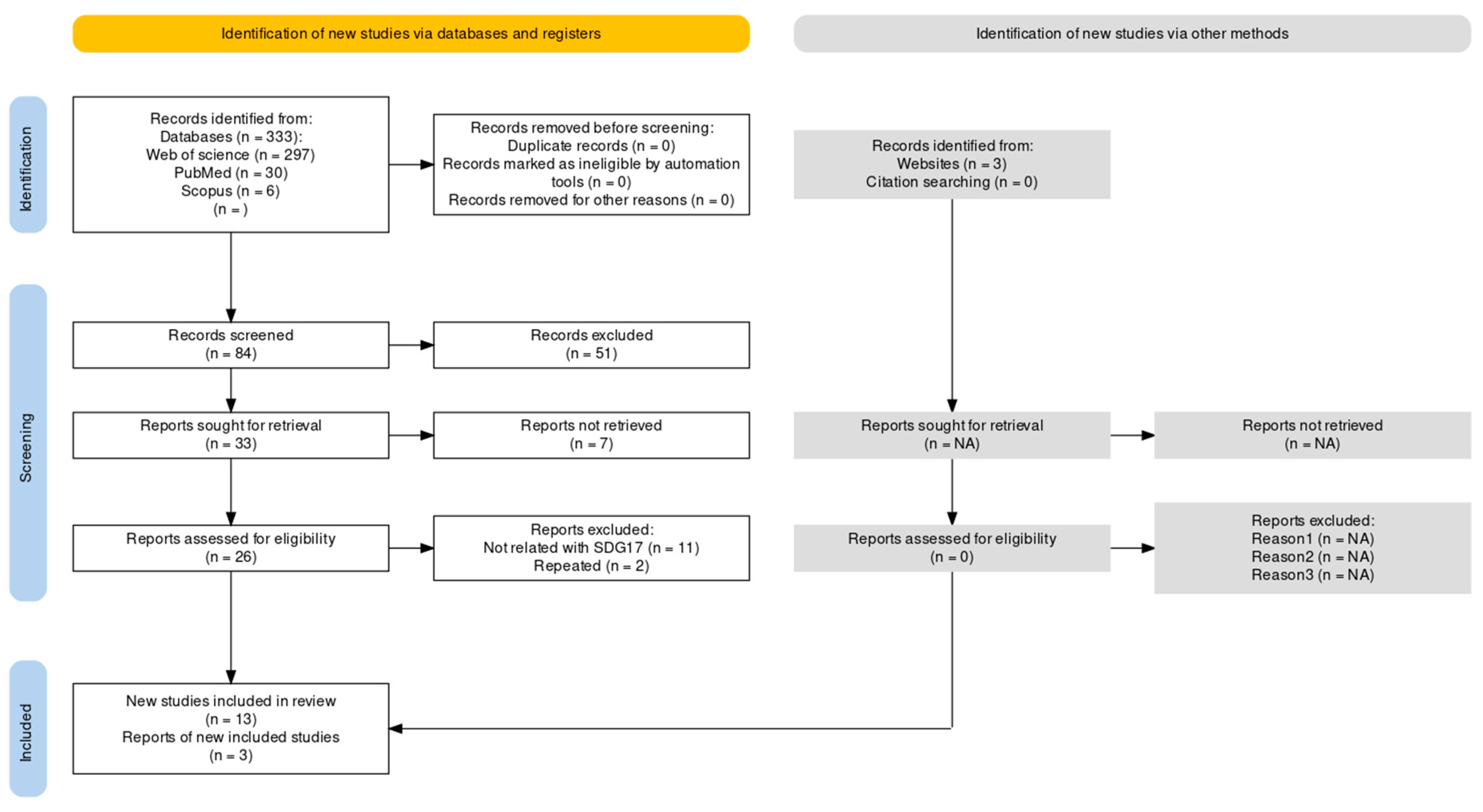

2. Materials and Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Information Sources

Risk of Bias

Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Indicator Definition

3.1.1. Entrepreneurship in Women

3.1.2. Gender Equality

3.1.3. Women’s Empowerment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- [1] FAO. Women and food security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [2] INEGI. 2020 Population and Housing Census; INEGI: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [3] FAO (2019). The world state of agriculture and food. Progress in the fight against food loss and waste. Rome.

- [4] United Nations Development Program (2020). HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2020. NY.

- [5] UNESCO. 2020. World Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and education: Everyone without exception. Paris.

- [6] UN Women (2018). Making promises a reality: gender equality in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development.

- [7] UN, Women (2021). Rural women face the global increase in the cost of living.

- [8] Stott, L; Scoppetta, A. Alliances for the Goals: beyond SDG 17. DIECISETE Magazine 2020, 2, 29–38.

- [9,25,45,49,51,55] Sánchez, M.; Winkler, R. The Third Shift? Gender and Empowerment in a Women’s Ecotourism Cooperative. Rural Sociology 2019, 85, 137–164.

- [10,26,46,50,52,58] Barrios, L.M.; Prowse, A.; Vargas, V.R. Sustainable development and women’s leadership: A participatory exploration of capabilities in Colombian Caribbean fisher communities. Journal of cleaner production 2020, 264, 121277. [CrossRef]

- [11.57] Rustinsyah, R.; Santoso, P.; Sari, N.R. The impact of women’s co-operative in a rural area in achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Masyarakat kebudayaan dan politik. [CrossRef]

- [12,27,36] Ferdousi, F.; Mahmud, P. Role of social business in women entrepreneurship development in Bangladesh: perspectives from Nobin Udyokta projects of Grameen Telecom Trust. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 58. [CrossRef]

- [13,28,37,38,56] Ge, T.A.; Abbas, J.; Ullah, R.; Abbas, A.; Sadiq, I.; Zhang, R.L. Women’s Entrepreneurial Contribution to Family Income: Innovative Technologies Promote Females’ Entrepreneurship Amid COVID-19 Crisis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 828040. [CrossRef]

- [14] Goodman, R.; Kaplan, S. Work-life balance as a household negotiation: a new perspective from rural India. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2019, 5, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [15,29,43,44] Uduji, J.I.; Okolo-Obasi, E.N.; Asongu, S.A. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Interventions on Female Education Development in the Rural Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2020, 20, 45–64. [CrossRef]

- [16,30,41,42] Burney, J; Alaofe, H.; Naylor, R.; Taren, D. Impact of a rural solar electrification project on the level and structure of women’s empowerment. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 095007. [CrossRef]

- [17,31,49] Dolezal, C.; Novelli, M. Power in community-based tourism: empowerment and partnership in Bali. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 2352–2370.

- [18,32,39] Vazquez, M. Building Sustainable Rural Communities through Indigenous Social Enterprises: A Humanistic Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9643. [CrossRef]

- [19] Okolo-Obasi, E.N.; Uduji, J.I., Asongu, S.A. Strengthening women’s participation in the traditional enterprises of subsaharan Africa: The role of corporate social responsibility initiatives in Niger delta, Nigeria. Afr. Dev. Rev. -Rev. Afr. Dev. 2020, 32, S78–S90.

- [20,33,40] Gonzalez, O.A.; Zorrilla, A.L.; Garcia, O. The motivation of women in the development of rural enterprises and decision making and the relationship with their satisfaction. Sciences de Gestion-Management Sciences-Management Sciences. 2019, 135, 57–77.

- [twenty-one] Mahato, J.; Jha, M.K.; Verma, S. The role of social capital in developing sustainable microentrepreneurship among rural women in India: a theoretical framework. Int. J. Innov. 2022, 10, 504–526. [CrossRef]

- [22,34] Cornish, H.; Walls, H.; Ndirangu, R.; Ogbureke, N.; Bah, O.M.; Tom-Kargbo, J.F.; Dimoh, M.; Ranganathan, M. Women’s economic empowerment and health related decision-making in rural Sierra Leone. Cult. Health Sex. 2021, 23, 19–36. [CrossRef]

- [23] Berrueta, V.M.; Serrano-Medrano, M.; García-Bustamante, C.; Astier, M.; Masera, O.R. Promoting sustainable local development of rural communities and mitigating climate change: the case of Mexico’s Patsari improved cookstove project. Climate Change 2017, 140, 63–77. [CrossRef]

- [24,35] Mora, G.M.; Fernandez, M.C. Rural women and productive action for autonomy. Mex. J. Sociol. 2019, 4, 797–824.

- [48,52] Salem, R.; Cheong, Y.F.; Miedema, S.S.; Yount, K.M. Women’s agency in Egypt: construction and validation of a multidimensional scale in rural Minya. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020, 26, 652–659. [CrossRef]

- [47] Cornwall, A. Women’s Empowerment: What Works? J. Int. Dev. 2016, 28, 342–359. [CrossRef]

- [59] Sánchez, M.; Wincker, R. The Third Shift? Gender and Empowerment in a Women’s Ecotourism Cooperative. Rural. Sociol. 2020, 85, 137–164. [CrossRef]

- [60] León, N.I.; Castellanos, M.I.; Curra, D.; Cruz, M.; Rodríguez, M.I. Research at the University of Holguín: commitment to the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Res. News Educ. 2019, 19, 348–378.

- [61] Damián, J. Develop productive projects in rural and indigenous areas of the State of Oaxaca: Student experiences. Univ. Rec. 2022, 32.

- [62] Rivas-Ángeles, K.P.; Alberti-Manzanares, P.; Osnaya, M.; León-Merino, A. Rural women: from the productive project to the microenterprise in Champotón, Campeche. Mex. Mag. Agric. Sci. 2015, 6, 1359–1371.

- [63] Alberti, M.P.; Zavala, H.M.; Salcido, R.B., Real, L.N. Gender, economics of care and payment of rural domestic work in Jilotepec, State of Mexico. Agric. Soc. Dev. 2014, 11, 379–400.

- [64] Robinson, D.; Díza-Carrión,IA; Cruz,S. Empowerment of rural and indigenous women in Mexico through productive groups and social microenterprises. J. Adm. Sci. Econ. 2019, 9, 91–108.

| Reference | Population characteristics | Data collection methodology | Indicators related to SDG 17 | Related SDGs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Quantitative | ||||

| [9] | 12 women members of the Orquídeas Cooperative, 5 former members, 9 who were never members; 8 men from the local community, 4 tourism and development professionals and 1 Mexican official. | In-depth qualitative case study. | Gender dynamics (roles). Empowerment. |

Resources. |

5, 8 |

| [10] | Leaders of women’s communities: 24 women (aged 24 to 65, all with secondary education and some technical training), belonging to 19 associations, direct household activities and responsible for local associations within FEPASACADI. | Participatory research for case studies. | Leadership. Sustainable development. Empowerment. |

5 | |

| [eleven] | Two women’s cooperatives that are considered successful, each receiving a grant of US$3,846 from the East Java provincial government for two terms; but the two cooperatives developed differently. | Case study, observation, in-depth interviews, focus groups, questionnaire. | Use of loans. | Debt level of low-income families. |

1.5 and 4 |

| [12] | 28 Nobin Udyokta women (new entrepreneurs) and four key informant interviews. young entrepreneurs average age does not exceed 35 years (only 17.86% exceed it), married and one divorced; with an average of 7.7 years of schooling. They are mainly dedicated to commercial and artisanal businesses. | Case study, exploratory research | Female Entrepreneurship. Women’s Empowerment Index. |

Age. Education level. Civil status. Family size. Average working hours. Average investment size. Average monthly income. |

1,5,4 |

| [13] | 150 businesswomen, including 75 urban and 75 rural participants: s. The rural regions included the villages of Thekri Wala, Sadhar, Dhandra, Pendra, 3 Chak, 2 Chak, Nathochak and Shehbazpur. | Regression model, observation, structured questionnaires and interviews (rural and urban area) |

Business activity. Entrepreneurial culture. Women empowerment. |

Income financial contributions Time dedicated to the business Age family size Education level Size of the company |

5, 8 |

| [14] | Women employed outside the home in rural areas; It focused on the villages surrounding the NGO’s head office and the two closest area offices, Khora and Chimayal. | Ethnographic research (grounded theory). | Types of negotiation. Job category. Decision making. |

Age. Gender. |

5, 8 |

| [fifteen] | 800 rural women from 54 communities, randomly selected from a list of households, aged between 21 and 50 years (average 38 years). | Cross-sectional quantitative method and describes and interprets the situation at the time of application of the survey technique (Logit-linear model). | Gender equality. Women’s education programs. Social development. |

Economic income. Illiteracy. |

1, 4, 5 |

| [16] | Women members of agricultural groups from 8 treatment and 8 matched-pair comparison villages in Kalalé, along with a random sample of 30 nonwomen household groups in each of the 16 villages both at the beginning of the project and 771 women surveyed at baseline and follow-up. There was some attrition from baseline to follow-up (33 women, or 4.3%), which was distributed across villages, with 6 at most in any village. | Quasiexperimental research design. Comparative analysis Factor analysis | Empowerment of women. Gender equality. |

Income. Economic independence. |

5 and 7 |

| [17] | 12 women, four castes: Brahmana (i.e., high priests), Satria, Wesia and Sudra (peasants). Employment: Rice producers, artisans, livestock, tourism, art (crafts, painting and carving), local entrepreneurship. village chiefs (1) who is VTC Member (and homestay owners). Accommodation owners (3) (in addition to VTC). craft production (1), sale of tourist products (1), waitress (1), cultural events (2), massage student (2), Bali CoBTA Staff (1), Bank of Indonesia (1) | Ethnographic methods for holistic understanding semistructured interviews, informal conversations and observations. | Women empowerment. Power dynamics. |

5, 8, 10, 15 | |

| [18] | The criteria for selecting the cases were: performance, visibility and size (number of employees/members ranging from 200 to 2000). The interviews included mostly managers and founders, mostly experienced workers, and community people whom local residents noted as the most knowledgeable in terms of the social enterprise and the history of the community . | Qualitative methodology and an interpretive approach through case studies, which included observations (predominantly nonparticipatory) and semistructured interviews. | Entrepreneurship (Indigenous social enterprises). Cultural patterns. Power differences. Strategies to achieve sustainable communities. |

Performance. Visibility. Size. |

1,3, 8, 10, 11 |

| [19] | 2,400 women throughout the region. | Quantitative method, directed surveys and observation field note . | Access to credit. Access to land. Rural transport. Knowledge of inputs. |

5, 10 | |

| [twenty] | Rural women who have undertaken business, however their characteristics or sample size are not specified. | Quantitative study through correlations. | Entrepreneurship. Empowerment. |

5 | |

| [twenty-one] | Theoretical and empirical literature works on micro business development or business development among rural women of three types of social capital: self-help group, SHG federation and NGO; and published in different areas and disciplines. | Literature review and analysis. | Levels of social capital. Role of social capital. |

5, 8 | |

| [22] | Women in a rural area. mothers, aged between 22 and 65 years. The majority were married at the time of the interview (n = 24, 83%) and of the remaining five, three were widows, one was separated from her husband, and the other reported that her husband had left her. All women (n = 29) were Muslim; 26 were Mende, one was from the Temne tribe, one was of Susu and Mandinka heritage, and one did not respond. | The analysis approach was both inductive and deductive, drawing on available data to generate reasonable explanations. | Empowerment | 3, 5, 8 | |

| [23] | The Patsari Network is an alliance of several NGOs in Mexico that seek to strengthen the work of organizations committed to participatory local development through the implementation of Patsari stove programs, with an emphasis on indigenous regions. | Patsari Stove Project Review and Its Benefits | Economic impact (time and cost) | 2, 3, 7, 13 | |

| [24] | Rural, peasant and/or women small agricultural producers, who are trained to develop an associative productive activity in the areas of agriculture, rural tourism, agribusiness and crafts in a rural area. mothers and wives aged between 36 and 60 years. The majority of them had not completed the 13 years of compulsory education in Chile. |

Qualitative methodology aimed at interpreting and understanding the social perceptions around gender awareness and physical, economic and political autonomy in the context of the Training and Training Program for Peasant Women. |

Empowerment Gender awareness |

5.8 | |

| Reference | Form of Intervention | Indicators (measurement) | Result | Related SDG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] |

Formation of an ecotourism cooperative. |

Women empowerment. Level that allows women to learn and grow as they overcome barriers and obstacles and benefit from useful resources along the way. Likewise, the promotion of personal aspirations, a sense of belonging and personal fulfillment. | The project failed due to the negative impact of daily gender practices, which referred to the fact that women must first be wives, mothers and take care of household chores and, second, their own interests and objectives. |

5, 8 |

| [26] | Training Workshops on basic concepts of conservation biology and leadership skills. |

Women empowerment. It is considered that which is generated from leadership in a feminist ecological policy framework that is crucial for the development of capacities within the community. |

The training workshops allowed women to identify themselves in leadership positions in relation to the ecological fishing processes in the Dique canal community. Greater awareness was generated about climate change and natural resources. The need to address inequality and support the empowerment of women through improving their ecological knowledge and economic dynamism of the area became visible. Likewise, gaining the support of male community leaders is essential. |

5 |

| [27] | Microcredits available from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) for social businesses. |

Female entrepreneurship. Tool to achieve economic empowerment among less educated and qualified women who are being avoided by the traditional labor market. Women’s Empowerment Index. Generated from criteria of mobility, decision making, autonomy, freedom, reproductive rights, access to media, contribution to household income, political and social awareness). |

Microcredits are smaller in size and are provided with a high interest rate. Furthermore, women are discriminated against in access due to lack of adequate network and mobility. The existing patriarchal norm implies restrictions on women’s access to productive resources and decision making. |

1, 4, 5 |

|

[28] |

Formation of women’s businesses |

Business activity and entrepreneurial culture Term associated with the process of generating something new by dedicating time and effort seeking to obtain benefits, personal satisfaction and independence. Women empowerment. Term directly related to entrepreneurship, as the latter alters power relations in the home and encourages the participation of women in all public spheres. In this sense, women become more active in business and become empowered as entrepreneurial characteristics increase their control over money. |

Although women’s entrepreneurial culture increases household income, entrepreneurial activity is significantly affected by literacy, family size, time dedicated to entrepreneurial activities, and company size. In this sense, it has become a powerful strategy to address problems related to unemployment and poverty. The need for legal support against gender discrimination in public and private institutions to promote an environment of entrepreneurial culture among women is evident. |

5, 8 |

| [29] | Rural employment program and savings group Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Application | Gender equality. A factor that directly depends on the right to education that we all have, which requires an approach that guarantees that men and women not only have access to and complete their studies, but that through education everyone is equally empowered. | The programs had little success, as it was not possible to ensure that the resources would arrive, due to the cultural and traditional context, which encourages discrimination and places women in situations of vulnerability, illiteracy and poverty. | 1, 4, 5 |

| [30] | Electrical network for the production of solar energy called Solar Market Garden (SMG), to expand the agricultural production of local groups of women dedicated to hand-watered horticulture |

Empowerment of women. Multidimensional term and which can be measured from decision-making in education and children, physical mobility to shop and see friends, the level of participation of men in household chores, the level of self-confidence generated from feeling important, respected and listened to, the economic independence to buy clothes and beauty items; and finally the sense of belonging to various social groups such as work and politics. Gender equality. Term directly related to the empowerment of women who consider it as an end in itself that allows them to achieve other desired development objectives, such as child health and nutrition. |

The electrical grid provided reliable access to energy to pump irrigation water, allowing for increased crop area, higher yields through better inputs and intensive management practices; and facilitating production throughout the year. It is considered a positive impact not only on the empowerment of women but also on economic well-being and food security. |

5, 7 |

| [31] | Community tourism (government, bank, tourism board and community) |

Women empowerment. Extent to which social interactions between actors promote or hinder the empowerment of women residing in rural areas. In addition, at the level of community balance, collaboration, a sense of community and strong community groups. |

It is observed that community tourism can create opportunities for the articulation of agency, self-organization and autonomy of villagers, if carried out in a balanced manner. However, the absence of qualified personnel, lack of knowledge of the potential benefits, and distrust on the part of the community make empowerment difficult. Although ties with external actors to carry out training contribute to empowerment, private investments are considered negative influences among the community (generates individual competitiveness). |

5, 8, 10, 15 |

| [32] | Strategic alliances to achieve sustainable communities Natives |

Entrepreneurship. Level of satisfaction of previously neglected needs and level of contribution in the construction of rural communities sustainable. |

The results show that social enterprises contribute positively to the most urgent social needs of humanity; through: the promotion of health and well-being, generation of work in communities, flat structures with equal opportunities in organizations and investment in environmental activities, related to the business of the company. | 1,3, 8, 10, 11 |

| [33] | rural entrepreneurship |

Entrepreneurship. Motivation to undertake. Empowerment. Depending on decision making and level of satisfaction. |

Although the main reason for women to undertake business is that they face an economic need, as a result of the migration of men. These ventures give you power and authority; and therefore, full satisfaction. Therefore, the result is positive, by increasing their empowerment which is reflected in the personal achievements that women achieve through them and personal and economic development. | 5 |

| [34] | Project to improve maternal and child reproductive health outcomes for women and adolescents by strengthening capacity of communities and health systems |

Empowerment. The ability to use capabilities and opportunities to expand the options available is related to the gender role that women have within the home and how decisions about vital matters are made. It is measured based on financial independence (direct relationship). | The microcredit model allowed women to enjoy financial independence, increase their confidence and improve the quality of their relationship as their husbands reacted positively to their own income generation. However, regarding health decisions, these continue to depend on men, because they believe that they have decision-making authority over their wives, considering they are the main provider of the home. On the other hand, health treatments are still too expensive for a woman to pay for on her own; hindering their independence of decision-making in health aspects. |

3, 5, 8 |

| [35] | Training and Training Program for Women Peasants. |

Gender equality: associated with the empowerment of women, seen as the degree of freedom that a woman has to act according to her own possibilities in order to expand her freedom in the private and public sphere. Empowerment : ability to choose that encourages the development of women’s skills to make strategic decisions about their lives. |

The study concludes that participation in the training and training program is highly valued, identifying that its impacts are linked to the processes of development of self-esteem and economic autonomy of the participants; However, it should be noted that these women continue to reissue their traditional gender roles. ditionals. |

| Forms of intervention | Organizations involved |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| public | Private | Nongovernmental (NGO) |

|

| Formation of ecotourism cooperative | National Commission of Protected Natural Areas of the Government of Mexico. | Nature Conservancy. World Wildlife Fund. |

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Friends of Sian Ka’an. Carlos Slim’s Foundation. |

| Training Workshops on basic concepts of conservation biology and leadership skills. | Federation of Agricultural, Aquaculture and Artisanal Fishermen of the Canal del Dique- FEPASACADI. | Formal associations of fishermen, farmers, aquaculture and artisans made up of women. | |

| Microcredits available from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) for women’s social businesses. | Narayanganj Government. Chapainabaganj Government. |

Groups of entrepreneurial women. | Grameen Telecom Trust. |

| Formation of women’s businesses | Women with business activities | ||

| Rural employment program and savings group Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Application | government Basic and upper secondary education institutions. |

Multinational oil companies (MOC). | Pahari Sansthan NGO. |

| Electrical network for the production of solar energy called Solar Market Garden (SMG), to expand the agricultural production of local women’s groups dedicated to hand-watered horticulture | Group of farmers. | US Solar Electric Light Fund (SELF) L’Association de Déével oppement Economique Sociale et Culturel, et l’Au topromotion (ADESCA-ONG). |

|

| Community-based tourism (CBT) | Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy (MTCE) | Bank Indonesia (BI) | Bali Community Tourism Association (CoBTA). Village Tourism Committees (VTC). |

| Strategic alliances to achieve sustainable communities | Education secretary | Indigenous social enterprises: Grupo Ixtlán. | |

| Strategic alliances to achieve sustainable communities | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (Participatory Forestry Development Project in the Andes) | Yanacocha (fourth largest gold mine in the world) Nestle |

Indigenous social enterprises: Granja Porcón. |

| Strategic alliances to achieve sustainable communities | Inter-American Development Bank and local corporations | Indigenous social enterprises: Wakami. | |

| Strategic alliances to achieve sustainable communities | Ministry of Economy the National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR) National development banks |

Indigenous social enterprises: Chicza. | |

| rural entrepreneurship | Government Program: National comprehensive rural training program | Women’s alliances or networks. | |

| Project to improve maternal and child reproductive health outcomes for women and adolescents by strengthening capacity of communities and health systems |

Sierra Leone Rehabilitation and Development Agency (RADA SL) |

Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLA). |

|

| Training Program and Training for Peasant Women |

Institute of Agricultural Development (Indap) of the State of Chile. | Foundation for the Promotion and Development of Women (Prodemu). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).