1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The European legislation on Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) usually refers to European Regulation (CE) n. 1272/2008[

1] (known as CLP - Classification Labelling Packaging) to define and classify carcinogenic chemical agents of concern for occupational risk assessment and occupational exposure assessment. The CLP Regulation in turn is aligned with the GHS (Global Harmonised System of chemical substance classification and labelling), the United Nations system to identify hazardous chemical substances and inform the customers-users regarding these hazards. Currently, at the European level, the most recent regulatory reference regarding the classification of carcinogenic chemical agents of occupational interest is the Directive (UE) 2022/431[

2], amending Directive 2004/37/EC[

3], regarding the protection of workers from the risks related to exposure to carcinogen, mutagen and reprotoxic agents (CMRs) at work. An example of practical implementation of European legislation at national level is the Italian OSH legislation[

4] that defines a carcinogen chemical substance as “1) a substance or mixture that matches the criteria for classification as a 1 A or 1 B carcinogen category in Annex I of the Regulation (CE) n. 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and Council (…)”.

1.2. Problem Statement

At present, it is interesting to note how it is often difficult to compare the classifications of carcinogenicity (CoCs) proposed by different international bodies and agencies[

5,

6], especially when it is necessary to exploit such information for risk assessment and management for occupational settings. Overall, there is not one homogeneous classification approach to establish carcinogenicity of substances and a hard debate exists on this topic. Boobis and co-workers[

5,

6] argued that the CoC is evaluated using: (i) “outmoded” schemes based solely on hazard identification (such as those used by IARC - International Agency for Research on Cancer and UN GHS); or (ii) approaches based on hazard and risk characterization (such as those used by US EPA - Environmental Protection Agency and ACGIH - American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienist). Following what was discussed in the previous studies[

5,

6], in the first kind of scheme, chemicals are divided into carcinogens and non-carcinogens and the categorization can be placed into the same category cases despite widely differing potencies and modes of action. This process bypasses the hazard characterization and risk assessment phases, stepping from hazard identification to risk management (the IARC and GHS systems classify agents on the strength of evidence and the capability to cause cancer in humans but provide no guidance on the circumstances in which this could occur). In the second kind of approach, an integrated scheme allows to take informed risk management decisions, because the hazard is evaluated in the context of dose, potency, and exposure. Based on this discussion, Boobis and colleagues[

5,

6] argued that a widely accepted, shared, and recognized methodology for carcinogens assessment and classification is needed, and the evaluation approach should incorporate principles and concepts of existing international consensus-based frameworks including the WHO IPCS (World Health Organisation - International Programme on Chemical Safety) mode of action framework. This proposal was critically discussed, and some authors[

7] argued that this approach is largely silent on the important role of epidemiological data, while key methodological aspects do not reflect the current state of science. The scientific hazard assessment is inappropriately conflated with the broader socio-political process of risk management, in sharp contrast to prominent recommendations for advancing risk assessment and systematic review. The review article of Felter and colleagues[

8] summarises themes and discussions resulting from an expert workshop on the scientific limitations of the current binary carcinogenicity classification scheme and the tiered testing strategies founded on new approach methodologies. This concept is reiterated by the article of Doe and colleagues[

9,

10], where a new approach cancer classification scheme has been proposed. As highlighted by this discussion, there is not a unique and homogeneous classification approach to assess and classify the carcinogenicity of chemicals. In occupational chemical risk assessment, the possibility of having CoCs for chemicals of interest obtained with different systems can cause uncertainty, misunderstanding or confusion in the definition of the risk assessment and risk management. On the contrary, the possibility of having access to a harmonized system to compare different CoCs could enable a better understanding in the hazard identification phase and thus, allow to enhance the risk assessment process for carcinogenic chemicals.

1.3. Aim of the study

The principal aim of this study is the implementation of a tool (based on an Excel spreadsheet) to allow a rapid comparison of the main international classification systems for a list of chemicals of concern for occupational carcinogenic risk. The intermediate steps necessary to achieve this result were the following: i) to investigate a list of chemicals of concern for occupational carcinogenic risk, classified as carcinogens or suspected to be carcinogens based on the CLP Regulation; ii) to search their CoC according to other international (i.e., non-EU) CoCs and convert them in the CLP CoC; iii) to compare the reference CLP CoC with others.

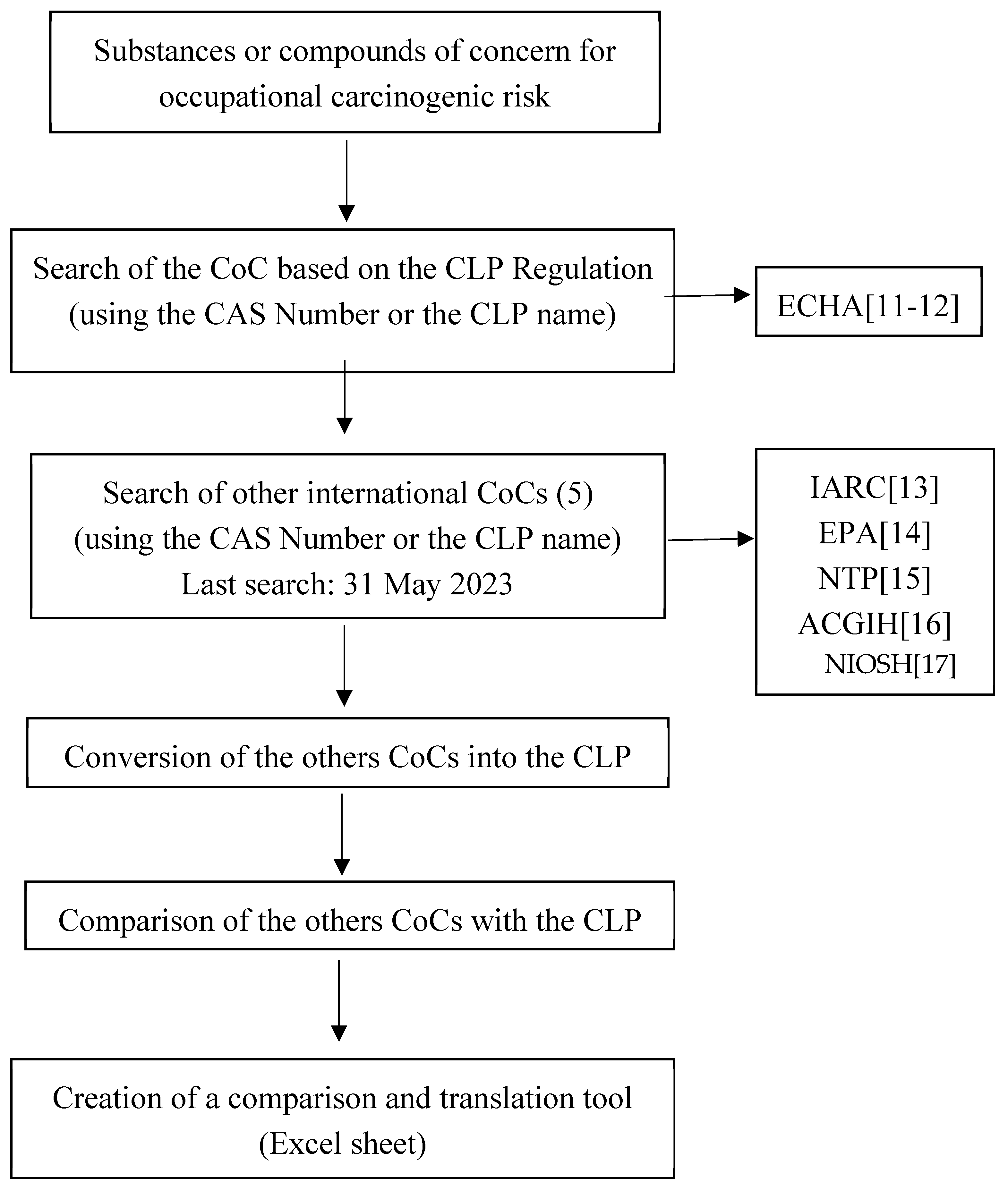

2. Methods

Substances and compounds of concern for their occupational carcinogenic risk and classified as carcinogens or suspected to be carcinogens based on the CLP Regulation, have been selected for the study. Two of the authors (C.Z., A.S.) selected a list of chemical agents and their respective CLP-CoC from the List of harmonized entries in Annex VI of CLP was consulted (18th Adaptation of Technical Progress which will come into effect on November 202311). The ECHA tool “Simple search for chemicals/regulated substances”[

12] was consulted too. Once the CoC according to CLP was defined, international CoC by IARC[

13], US EPA[

14], US NTP - National Toxicology Program[

15], ACGIH[

16], NIOSH - National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [

17] were obtained for the same chemical agents. Chemicals’ classifications have been searched with their specific CAS number (Chemical Abstract Service Registry Number) or, if CAS numbers were not available for certain chemicals, with their CLP ECHA name. The last search was performed in May 2023.

Once the CoCs according to the selected sources were defined, these have been “converted” with the equivalent CLP CoC (arbitrarily considered to be the reference for this study) based on criteria defined in previous studies[

18,

19]. The scheme for the conversion of EPA, ACGIH, NTP, and IARC CoCs into the CLP CoC is summarized in

Table 1; the entire methodology is summarized in

Figure 1. All the classification systems were converted (translated) into the CLP CoC system to allow an intuitive comparison to them due to their different criteria of classification and their terminologies.

It is worth noting that, regarding the NIOSH classification, a “qualitative” carcinogenicity classification was attributed, based only on the presence or absence of the chemicals in the consulted list, as no other information on carcinogenicity level categorization is available. Therefore, the category “C” referred to NIOSH CoC defines an “Occupational Carcinogen”. In addition, if the outcome of classification conversion resulted in an uncertain assignment between different classification categories (for example CLP categories 1B and 2), the classification was arbitrarily assigned to the most precautionary CLP category of the options considered (1B in this example). The concordance of the “converted CLP CoC” with the reference classification (“original CLP”) was verified. If the CLP CoC was not available (“n.a.”: not available – see

Table S1 -

Supplementary Materials) for the selected chemicals, the IARC classification was considered as a primary reference for comparison with other classification systems. It is important to note that no new hazard assessments or new classifications of chemical agents were proposed or carried out in this study. Instead, the classification proposed by various sources consulted regarding the classification of carcinogenicity of selected chemicals was retrieved and used to apply a translation method, to favor an alignment of different classification systems according to a system chosen as reference.

3. Results

3.1. General description of the obtained results

A total of 83 chemical substances, compounds, or mixtures of concern for occupational carcinogenic risk were selected for this study. A conversion and translation database (“tool” is used from here on out with the same meaning) has been created (Excel spreadsheet). The database is freely available online for consultation20. As mentioned, CLP, IARC, EPA, ACGIH, NTP and NIOSH CoCs for the selected chemicals were retrieved from proper sources, and IARC, EPA, ACGIH, NTP and NIOSH CoCs were converted in the CLP-CoC. Details on the database structure, the conversion, and the comparison of substances, are reported in the

supplementary material (Tables S2, S3, S4, supplementary materials).

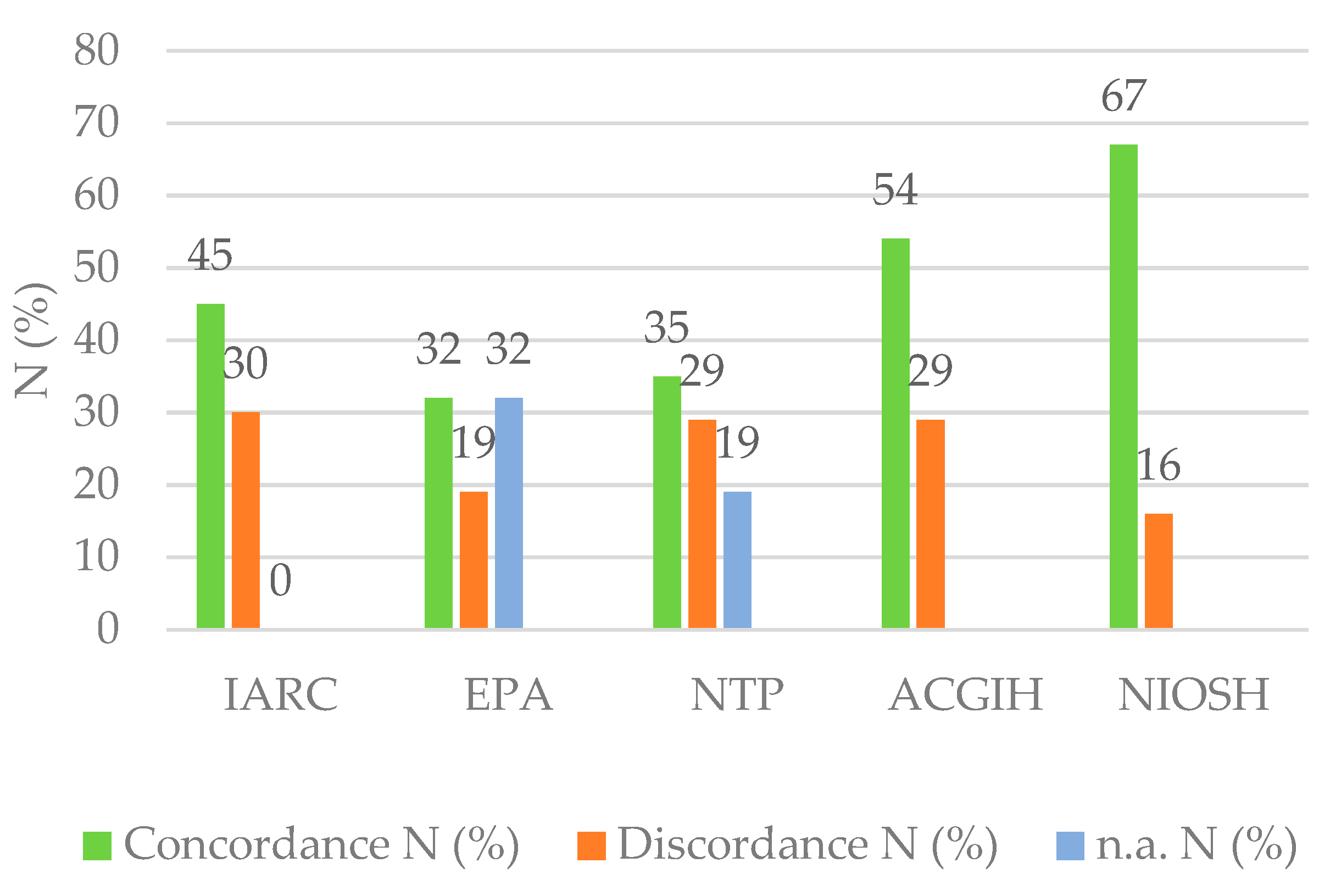

Figure 2 reports comparison results of the international IARC, EPA, NTP, ACGIH and NIOSH CoCs, converted in the CLP-CoC and compared with the original CLP CoC. It is worth noting that after the conversion some cases of indecision were found (this could be due to the fact that there is not always a unique and clear correspondence between different CoC; see

Table 1)

The IARC CoC was used by arbitrary choice as reference CoC for 8 (10%) chemicals (namely: 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo[b,e][

1,

4]dioxin (TCDD); polychlorobiphenyls (PCBs); benzoyl chloride; cyclopenta[c,d]pyrene; tungsten carbide; arsenic compounds, except for those specified elsewhere in ANNEX VI CLP-ATP 18; wood powder; soot) because CLP CoC was not available, since: (i) carcinogen data were lacking; (ii) there was no harmonized classification; (iii) data are conclusive, but not sufficient for classification.

Overall, for 23 chemicals out of 83, the converted CLP CoC resulted in a complete concordance with the original CoC (

Table S5 - supplementary material). CoC of 6 EPA cases and 3 ACGIH cases were not available. For 12 chemicals, the CoC was referred to a group of chemical compounds (and not to a specific chemical). The comparison of the converted CLP CoC with the original CoC of the remaining 60 chemicals showed at least one discordant CoC in each of these chemicals (

Table S6 - supplementary material). A brief discussion on the results obtained from this last comparison have been reported hereafter; the chemicals for which similar reasons have been hypothesized, at the base of the observed differences, in the CoC according to different systems have been grouped into "clusters". Before investigating these clusters, it is needed to explain why clusters have been created.

3.2. Discrepancies in classification of carcinogenicity, missing data and unusual results

A more detailed investigation (i.e., consulting official documents from the Agencies) was necessary for some substances since these chemicals were not found in the consulted databases or were defined as non-carcinogen in one system, while for other systems the same were classified as 1A or 1B carcinogens. These chemicals were divided into four "clusters" as presented and briefly discussed in the following paragraphs.

3.2.1. Cluster 1 - “Groups” of chemicals

This cluster is made up of 29 chemicals (

Table S7 - supplementary material) and refers to chemicals which could not be identified with a specific CAS number when consulting databases of the considered carcinogens classification systems but could be identified using the CAS number of a group of compounds. Most of them are Arsenic, Chromium, and Nickel compounds, as well as Cool Tar and Cool Tar Pitches. As an example, it is interesting to focus on the cases of “cadmium (non-pyrophoric) and cadmium oxide (non-pyrophoric)” (CAS 7440-43-9 [

1], 1306-19-0 [

2]): these two were included in the original list of chemicals of interest but, as a result of a first research, they were not present in the NIOSH list. Consequently, both compounds were preliminarily classified as “non-carcinogen” in the database that was being created. Then, a second round of research was carried out which allowed us to establish that the "Cadmium fumes" (CAS 1306-19-0) entry of the NIOSH List also included cadmium oxide, thus defining “cadmium (non-pyrophoric) and cadmium oxide (non-pyrophoric)” as a carcinogen also according to the NIOSH List. These two examples can be understood as emblematic cases of the possible difficulty of correctly classifying mixtures, as well as of the different details of the lists of carcinogenic chemical agents considered.

3.2.2. Cluster 2- Mixture of chemicals

This cluster consists of 2 mixtures, namely (i) butane containing ≥ 0,1 % butadiene; and (ii) isobutane, containing ≥ 0,1 % butadiene. These two mixtures are classified as 1A according to the reference CoC system (CLP Regulation) due to the presence of butadiene in concentration above 1%, which represents the carcinogenic chemical in the mixture. Searching these two cases, using the CAS Number, a non-carcinogenicity response was initially found by the IARC, NTP and NIOSH CoCs while a not available data was found by EPA and ACGIH CoCs. The differences between a non-carcinogenicity results and not available data in the CoCs are linked to the specific or unspecific consulted documents (non-carcinogenicity if the document is specific for carcinogens; not available data if the documentation is referred not only to carcinogens). Moreover, for the CLP classification a non-carcinogenicity response was found if we considered them as single chemicals (

Table S8, supplementary materials).

3.2.3. Cluster 3- Chemicals classified under different CAS numbers or with different names.

This cluster consists of 2 chemicals, namely (i) pitch, coal tar, high-temperature and (ii) cadmium (pyrophoric)). Both these chemicals have been listed in the consulted sources with a different CAS or with a different name respect to those reported in the original list (

Table S9, supplementary materials). The first case (“pitch, coal tar, high-temperature”) is not present in the consulted NTP RoC (Report of Carcinogens) with the CAS 65996-93-2 (as reported in the CLP list), but with the CAS 8007-45-2; this latter resulted to be associated to entries also in other CoCs. The second case “cadmium (pyrophoric)” (the name reported in the CLP list used as original source) is not present in the NIOSH List with this name, but with a different name (i.e., “cadmium dust”; this latter resulted to be associated to entries also in other CoCs).

3.2.4. Cluster 4 - Discrepancies in classification of carcinogenicity

This cluster is made up of 16 chemicals (

Table S10, supplementary materials) which resulted to be not listed in NIOSH (14 cases) and NTP (2 cases) lists; moreover, further details were not found on these chemicals when searching for documentation in these two systems. Thus, these chemicals resulted to be listed as “non-carcinogens” in the database under construction for this study.

It should be noted that all the other considered CoCs have defined them as carcinogens.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall discussion

Results of the study confirmed that different classification systems for the carcinogenicity of chemicals can result in different classifications of the same chemicals, when considering different sources. Further, it is worth noting that often it is difficult to compare the CoCs proposed by different Agencies. Overall, this may have implications for the hazard assessment process, which is the basis of risk assessment. The first difficulty when dealing with the comparison of different CoCs has been found while accessing information on chemicals: some of the chemicals may be grouped with different criteria and, sometimes, the CoC of the specific chemical agent cannot be accessed. Further, all the consulted documentation has a different structure and sometimes it is not immediate to search for the substance of interest. An example could be the NIOSH occupational carcinogens list. It consists of specific documentation on carcinogens referred to occupational settings, but no further information is reported there (including the chemical’s CAS number). In addition, for some chemicals, the NIOSH to CLP and NTP to CLP converted CoCs have been deepened, because a non-carcinogenicity classification has been found with the first research (matching chemicals based on their CAS numbers) and a discorded response with the others CoCs was defined. After the second research, for some cases, documentation related to the CoCs have been found, thus an alignment with other CoCs was possible. For other chemicals, only data related to animal experiments was found, therefore no more information has been collected. Also, it is important to emphasize that for 3 cases the documentation was available but not a classification of a carcinogenicity. These cases are PCB (PolyChlorinated Biphenyl), RCF (Refractory Ceramic Fibres) and erionite. (

Table S11, supplementary materials). To explain the issue on this topic, an emblematic case could be PCBs, for which a great diversity on the CoCs could be observed First, the reference CLP CoC is not available: consulting the substance information on ECHA, the following statement is reported: “There is no harmonised classification and there are no notified hazards by manufacturers, importers or downstream users for this substance”. It should be noted that despite PCBs could possibly be chemicals of concern in occupational settings, this class of chemicals does not fall in the CLP and REACH domain (i.e., PCBs are not substances produced to be placed on the market), therefore it is possible that a harmonized classification for PCBs (and other chemicals attributable to this situation) is not available. Anyhow, IARC CoC defines PCBs as 1A carcinogens (and this could be considered as a primary source of information), but at the same time, PCBs are not included in the NIOSH list of occupational carcinogens. It must be noted that, the Current Intelligence Bulletin 45 (1986)22 explains that a definite causal relationship between exposure and carcinogenic effects in humans remain unclear due to the inadequately defined populations studied and the influences of mixed exposures. However, since data from animal tests exist, NIOSH “recommends” that PCBs be considered as potential human carcinogens in the workplace. However, in 2019, the NIOSH Pocket Guide23 to chemical hazards defines Polychlorinated biphenyl [Chlorodiphenyl (42% chlorine)] and Polychlorinated biphenyl [Chlorodiphenyl (54% chlorine)] as “potential occupational carcinogens”.

Concerning the different classification systems, as reported in multiple studies5–10, debates exist on both the crucial role of the classification systems and the importance of creating a new classification system which considers all the available scientific data. Classification systems use different approaches to investigate carcinogenicity. Some of them are defined by some Authors as “outmoded”, who emphasise instead other systems as “more modern”.

Table 2 reports some information about the criteria that Agencies use in their consulted documentation11,15,16,18,21,23. It should also be specified that some differences that emerged in this study could be biased during the conversion and due to “practical” issues linked to the research of information and the available data of the consulted database or list of substances. More in detail, the observed difference might be related to the method of translation, rather than an actual difference in classification, as well as our decision to consider, for the indecision cases, the highest of the two categories of carcinogenicity as the righter. A further example of a possible bias is “Cluster 1” chemicals, for which discordances could be caused by the decision to consider, where the specific substances have not been found (with the CAS number used by CLP CoC), a group of compounds, where that substance is represented. In this way, the CoC of the “generic” group of compounds also applies to a certain chemical. On the opposite, “Cluster 3” identifies substances that could have a different name, but the same CAS number or practically the same chemicals listed under different CAS numbers. Further, consulting different sources for the purpose of this study it emerges that some mixtures included in the original list are only included in the CLP database. Different considerations could be made on “Cluster 4” chemicals of this study. This cluster groups substances where a severe discordance among NIOSH or NTP CoCs and other CoCs systems was observed, but for which other information has not been found, or for which evaluations are not conclusive. In this regard it is worth noting that NIOSH “Chemical Carcinogen Classification Policy”25 assigns the definition of “occupational carcinogen” to a substance based on the NTP, EPA and IARC CoCs. This policy wants to evaluate occupational relevance of these carcinogen designations to ensure that the appropriate hazards are accurately identified in occupational settings. In this way, NIOSH efforts will be to evaluate worker’s carcinogenic risk and to develop recommendations to risk management. If the scientific basis of the CoCs is occupationally relevant, NIOSH will list chemicals as an occupational carcinogen. If a chemical has not been evaluated by any of the three agencies, NIOSH considers nominating it to NTP for review or decides to develop its own carcinogen classification (using the criteria for carcinogenicity contained in the GHS).

4.2. Strengths and limitations of the study

This study provides a conversion and translation database, built consulting different public CoC systems (i.e., ECHA, IARC, EPA, ACGIH, NTP and NIOSH). Filtering the database for a specific chemical using the name or CAS number allow to obtain the result for all the consulted CoC systems, converted in the reference system for this study (CLP CoC) (or as published from the original sources, using the comparison table). The study is characterized obviously by some limitations: the very first is that the study only covered a relatively short list of chemicals. Thus, the database cannot be considered exhaustive of all carcinogenic chemical agents potentially present in working environments. Moreover, for this study, only European (i.e., CLP) and American (i.e., EPA, ACGIH, NTP, NIOSH) CoC systems were considered, accompanied by an international system (i.e., IARC). Other Agencies worldwide were not considered at this stage. It is worth noting that the database is intended to be a merely exploratory and consultative tool, only for research purposes and that it is necessary to always refer to the legislation in force for the correct classification of carcinogenicity of chemical agents of occupational interest. Classification data and conversions in the database are derived by the consultation of official public sources from the different Agencies. Consideration done on concordances and discordances of these, are derived from interpretation of authors.

4.3. Future developments

A future development of this study could be the extension of the chemicals list and to extend the study including other classification Agencies: enabling a more extensive comparison with the different classifications currently in force in the world and their assessment could be interesting and useful (speaking of global market).

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

A freely available database and translation tool has been created. It reports a list of 83 chemicals of concern for occupational carcinogenic risk, classified as carcinogens or suspected to be carcinogens based on the CLP Regulation. For each of these chemicals, the classification of carcinogenicity proposed by European (CLP - considered as the reference system for this study), American (i.e., EPA, ACGIH, NTP, NIOSH) and international (i.e., IARC) systems is reported, also “converted” in the CLP system. Discordances in the original CoCs of considered chemical agents exist and critical issues have been defined. The proposed tool is expected to help risk assessors in occupational field, if there is the need to have a comparison with different CoC systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Differences between the classification categories “NO” and “n.a.” for the classifications; Table S2: Columns information of the tool; Table S3: Original CLP, IARC, EPA, ACGIH, NTP and NIOSH classification; Table S4: Conversion of IARC, EPA, ACGIH, NTP and NIOSH classification in the reference CLP CoC; Table S5: 23 cases classified with concordance in all the classifications. In red, cases where were not used specific CAS, but CAS referred to a group of compounds; Table S6: 60 cases that have at least one discordant classification; Table S7: Case data for groups of compounds; Table S8: CLP COC and IARC, EPA, ACGIH, NTP, NIOSH converted CoCs of Butane and Isobutane; Table S9: case history of cluster 3; Table S10: Cluster 4, divisions; Table S11: CoCs – CLP converted of PCBs (PolyChlorinated Biphenyls), RCF (Refractory Ceramic Fibres) and erionite.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z., A.S.; methodology, C.Z., A.S.; investigation, C.Z., A.S..; data curation, C.Z., A.S..; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z., A.S..; writing—review and editing, A.C., A.CR., D.C., D.M.C., F.B., G.F., M.K., S.R., supervision, A.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACGIH |

American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (United States) |

| CAS Number |

Chemical Abstract Service Registry Number |

| CLP |

Classification Labelling Packaging - European Regulation (CE) n. 1272/2008 |

| CMRs |

Carcinogen, Mutagen, Reprotoxic agents |

| CoC |

Classification of Carcinogenicity |

| ECHA |

European Chemicals Agency |

| ECETOC |

European Centre for Ecotoxicology and Toxicology of Chemicals |

| EPA or US EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency (United States) |

| GHS |

Globally Harmonised System |

| IARC |

International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| NIOSH |

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (United States) |

| NTP or US NTP |

National Toxicology Program (United States) |

| NTP RoC |

National Toxicology Program Report of Carcinogens |

| OHS |

Occupational Safety and Health |

| WHO IPCS |

World Health Organisation - International Programme on Chemical Safety |

References

- Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of The European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, amending and repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006. (2009).

- Directive (EU) 2022/431 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2022 amending Directive 2004/37/EC on the protection of workers from the risks related to exposure to carcinogens or mutagens at work.

- Corrigendum to Directive 2004/37/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the protection of workers from the risks related to exposure to carcinogens or mutagens at work (Sixth individual Directive within the meaning of Article 16(1) of Council Directive 89/391/EEC) (codified version) work (Sixth individual Directive within the meaning of Article 16(1) of Council Directive 89/391/EEC) (codified version) (Text with EEA relevance).

- D.lgs. 9 aprile 2008, n. 81 Testo coordinato con il D.Lgs. 3 agosto 2009, n. 106. Testo unico sulla salute e sicurezza sul lavoro. Attuazione dell’articolo 1 della Legge 3 agosto 2007, n. 123 in materia di tutela della salute e della sicurezza nei luoghi di lavoro. (Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 101 del 30 aprile 2008 - Suppl. Ordinario n. 108) (Decreto integrativo e correttivo: Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 180 del 05 agosto 2009 - Suppl. Ordinario n. 142/L).

- Boobis, A. R. et al. Classification schemes for carcinogenicity based on hazard-identification have become outmoded and serve neither science nor society. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2016, vol. 82 158–166. [CrossRef]

- Boobis, A. R. et al. Response to Loomis et al Comment on Boobis et al. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2017, vol. 88 358–359. [CrossRef]

- Dana Loomis, K. Z. G. K. S. C. P. W. Classification schemes for carcinogenicity based on hazard-identification have become outmoded and serve neither science nor society. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2016, vol. 82 158–166. [CrossRef]

- Felter, S. P. et al. Hazard identification, classification, and risk assessment of carcinogens: too much or too little? Report of an ECETOC workshop. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 2020, vol. 50 72–95. [CrossRef]

- Doe, J. E. et al. The codification of hazard and its impact on the hazard versus risk controversy. Archives of Toxicology 2021, vol. 95 3611–3621. [CrossRef]

- Doe, J. E. et al. A new approach to the classification of carcinogenicity. Arch Toxicol 96, 2419–2428 (2022). [CrossRef]

- ECHA. European Chemicals Agency. List of harmonized entries in Annex VI of CLP - Adaptation to Technical Progress 18. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/information-on-chemicals/annex-vi-to-clp (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- ECHA. European Chemicals Agency / regulated substances. Simple search for chemicals. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/it/search-for-chemicals (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- IARC. International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC monographs on the identification of carcinogenic hazards to humans. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/list-of-classifications (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- US EPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency. IRIS-Integrated Risk Information System. Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/search/index.cfm (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- US NTP. United State National Toxicology Program. 15th Report on Carcinogen. Available online: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/whatwestudy/assessments/cancer/roc/index.htm (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- ACGIH. American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists. TLVs® and BEIs® booklet. Based on the Documentation of the Threshold Limit Values for Chemical Substances and Physical Agents & Biological Exposure Indices. 2023 ISBN: 978-160-726157-5.

- NIOSH. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Occupational Cancer - Carcinogen List. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/cancer/npotocca.html (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- NIOSH. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Current Intelligence Bulletin. Update of NIOSH Carcinogen Classification and Target Risk Level. Policy for Chemical Hazards in the Workplace. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docket/review/docket240A/pdf/EID-CIB-11052013.pdf (accessed on September 2023).

- Prevor. Anticipate and save. Toxicology laboratory e chemical risk management. Carcinogens: Different classifications. Available online: https://www.prevor.com/en/carcinogens-different-classifications/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- CARCINOSYS Database. Available online: https://rahh.uninsubria.it/index.php/research-project/carcinosys-database (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- IARC. International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs Preamble. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Preamble-2019.pdf (accessed on September 2023).

- NIOSH - National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB’s): Current Intelligence Bulletin 45. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/86-111/default.html (accessed on September 2023).

- NIOSH. NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/default.html (accessed on September 2023).

- EPA. Environmental Protection Agency. Guidelines for Carcinogen Risk Assessment. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2013-09/documents/cancer_guidelines_final_3-25-05.pdf (accessed on September 2023).

- NIOSH. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Current Intelligence Bulletin 68. Chemical Carcinogen Classification Policy. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2017-100/pdf/2017-100.pdf (accessed on September 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).