1. Introduction

Cancer is a common and prevalent global disease, accounting for approximately 25% of all deaths in most developed countries, making it the leading cause of death [

1,

2]. Cancer is characterized by its ability to invade and metastasize to other tissues or organs, making it difficult to cure [

3]. Cancer-derived stem cells (CSCs), one of the intricate factors in cancer treatment, constitute a small population within cancer cells. This population accounts for 1-2% of cancer tissue and plays a pivotal role in cancer recurrence post-treatment.

Cancer stem cells, akin to normal stem cells, exhibit self-renewal and differentiation capabilities. However, unlike normal stem cells, they possess the ability to initiate tumor formation (tumorigenicity), propagate tumors throughout the body, and undergo unlimited self-renewal [

4,

5]. Typically existing in a dormant state, CSCs demonstrate resistance to anticancer drugs, posing a formidable obstacle in their eradication during cancer therapy and significantly contributing to cancer relapse and metastasis [

6]. Consequently, comprehensive cancer treatment requires the targeted removal of both cancer cells and CSCs.

In recent years, research on targeted cancer therapies against CSCs has become increasingly active, complementing conventional surgical procedures, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy [

7]. Nevertheless, challenges persist due to the involvement of CSCs in diverse signaling pathways, limited knowledge regarding substances targeting this small CSCs population, and the high resistance of these cells to anticancer agents [

8].

To overcome these limitations, a new approach to cancer treatment is required. Recent research suggests that early cancer detection and appropriate treatment can substantially enhance the 5-year survival rate by over 80 - 90%. Early diagnosis also facilitates more feasible treatment options and interventions [

9,

10]. Therefore, the discovery of biomarkers using various omics-based analysis techniques for early cancer detection has emerged as a new technological advancement in cancer research [

11,

12].

New or novel biomarkers, indicative of physiological changes based on substances like DNA, RNA, and proteins within the human body, are being utilized as substances for prognostic confirmation after disease treatment or for the diagnosis of early-stage diseases [

13]. However, due to the heterogeneous nature of cancer, discovering new markers is challenging. Therefore, overcoming the variability in treatment effectiveness due to genetic differences and simultaneously treating various types of cancer and CSCs with a single or combination therapeutic approach necessitates the development of innovative cancer therapeutics.

To address this, we applied proteomic analysis techniques to identify common new biomarker in the cell surface of lung cancer, liver cancer, breast cancer and each cancer cells-derived CSCs. These types of cancer are expected to increase in incidence due to factors such as the growing prevalence of lung cancer caused by the recent pandemic, the escalating worldwide prevalence of obesity, attributed to the abundance of food, is associated with an increasing number of liver cancer patients, and the consistently high incidence and mortality rate of breast cancer in women [

14,

15,

16]. The goal of this research is to utilize proteomic analysis techniques for the discovery of novel biomarkers in both cancer and CSCs. Simultaneously, the aim is to evaluate the biological functions performed by this biomarker within each cell and assess its potential as novel biomarkers.

3. Discussion

The global rise in cancer, a perilous disease with high incidence and mortality rates worldwide, has sparked increased attention towards cancer therapy, leading to active research across various fields [

1,

2]. Despite these efforts, current research has not fully addressed the inherent challenges associated with cancer, including the difficulty in achieving complete cures, targeting cancer stem cells, and diagnose multiple types of cancer simultaneously [

4,

5,

6,

13]. Furthermore, cancer treatments often come with significant side effects, such as the acute or chronic toxicity of anticancer drugs, the inability to exclusively target tumors (posing a risk of attacking normal cells), and the induction of immune responses [

7]. To overcome these limitations, this study aimed to conduct a proteomic analysis to identify cell surface biomarkers that are commonly expressed in various cancer types. These biomarkers hold the potential to serve as both diagnostic tools and therapeutic agents for diverse cancer.

In this study, we targeted three specific types of cancer based on their anticipated high future incidence, consistently elevated mortality rates, and the associated treatment challenges. Firstly, we chose lung cancer, driven by the escalating number of patients post-COVID-19 complications and its substantial mortality rates across both genders [

14]. Secondly, liver cancer was included in our study, recognizing its rising incidence associated with the growing prevalence of obesity and irregular lifestyle choices [

15]. Lastly, we focused on breast cancer, a leading cause of high incidence rates among women, characterized by its challenging treatment dynamics due to frequent metastasis and the presence of significant lymph nodes in the vicinity [

16]. By concentrating on the development of biomarkers specific to lung, liver, and breast cancers, as well as exploring cancer-derived CSCs as potential candidates for anticancer treatment and diagnosis, our study aims to contribute valuable insights that can pave the way for more effective and targeted interventions in the battle against these challenging malignancies.

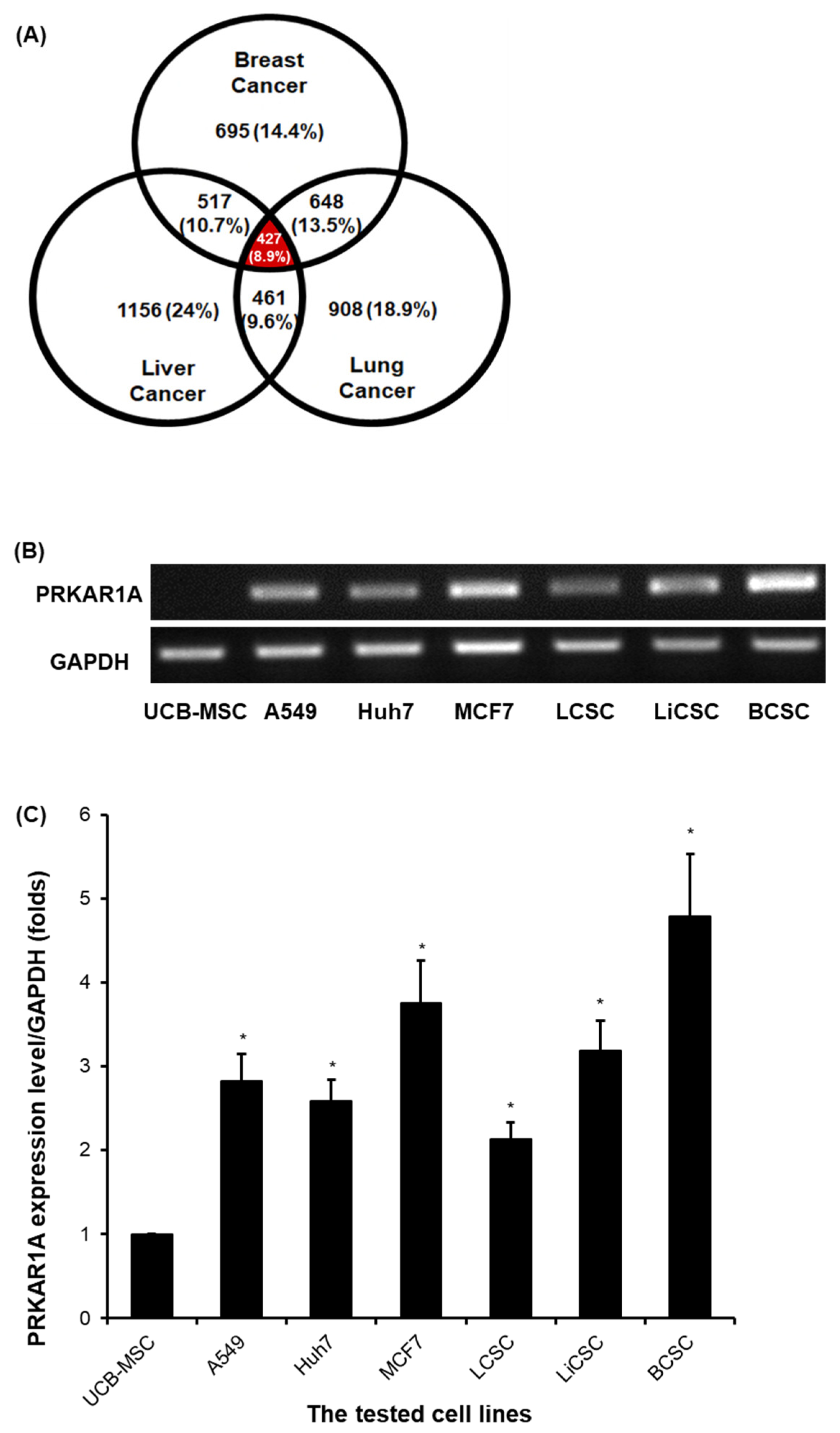

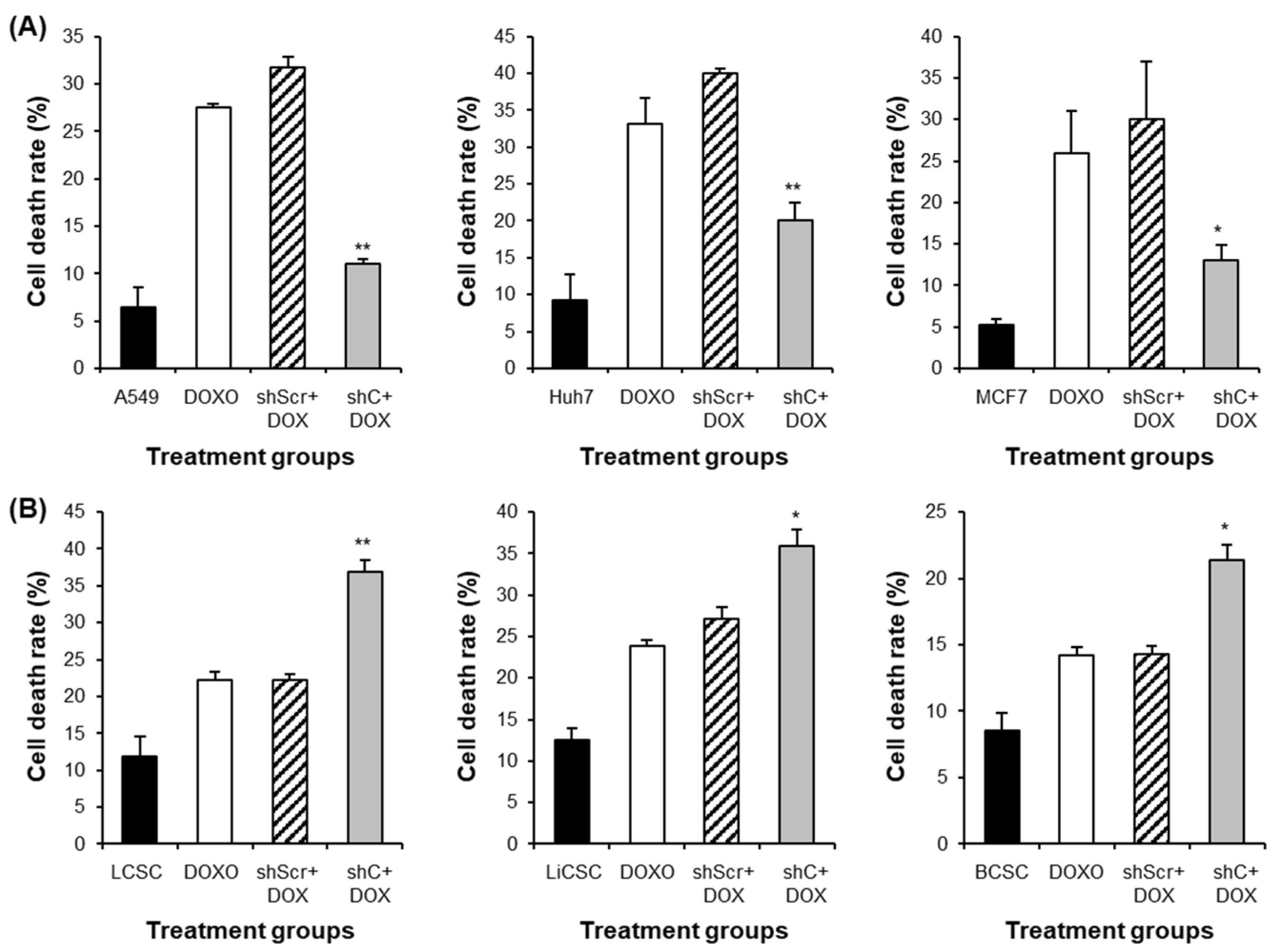

For this, we initiated a proteomic analysis to identify new biomarker proteins in lung cancer, liver cancer, breast cancer cells and each cancer-derived CSCs (

Figure 1) We have selected the protein PRKAR1A, which is expressed on the cell surface, as a potential biomarker for future use as a diagnostic marker and as a target molecule for developing new drugs. Through this, we have identified PRKAR1A as an effective substance. This protein subunit encoded by the PKA gene and a part of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase A [

17], emerged as a candidate biomarker. However, surprisingly, there is not much research on this protein, and there is almost no functional study in CSCs.

Despite the recognized role of cAMP in regulating various metabolic processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, the specific influence of PRKAR1A on cancer remains inadequately studied, with conflicting results within existing research on different cancer types [

17,

18,

19,

20,

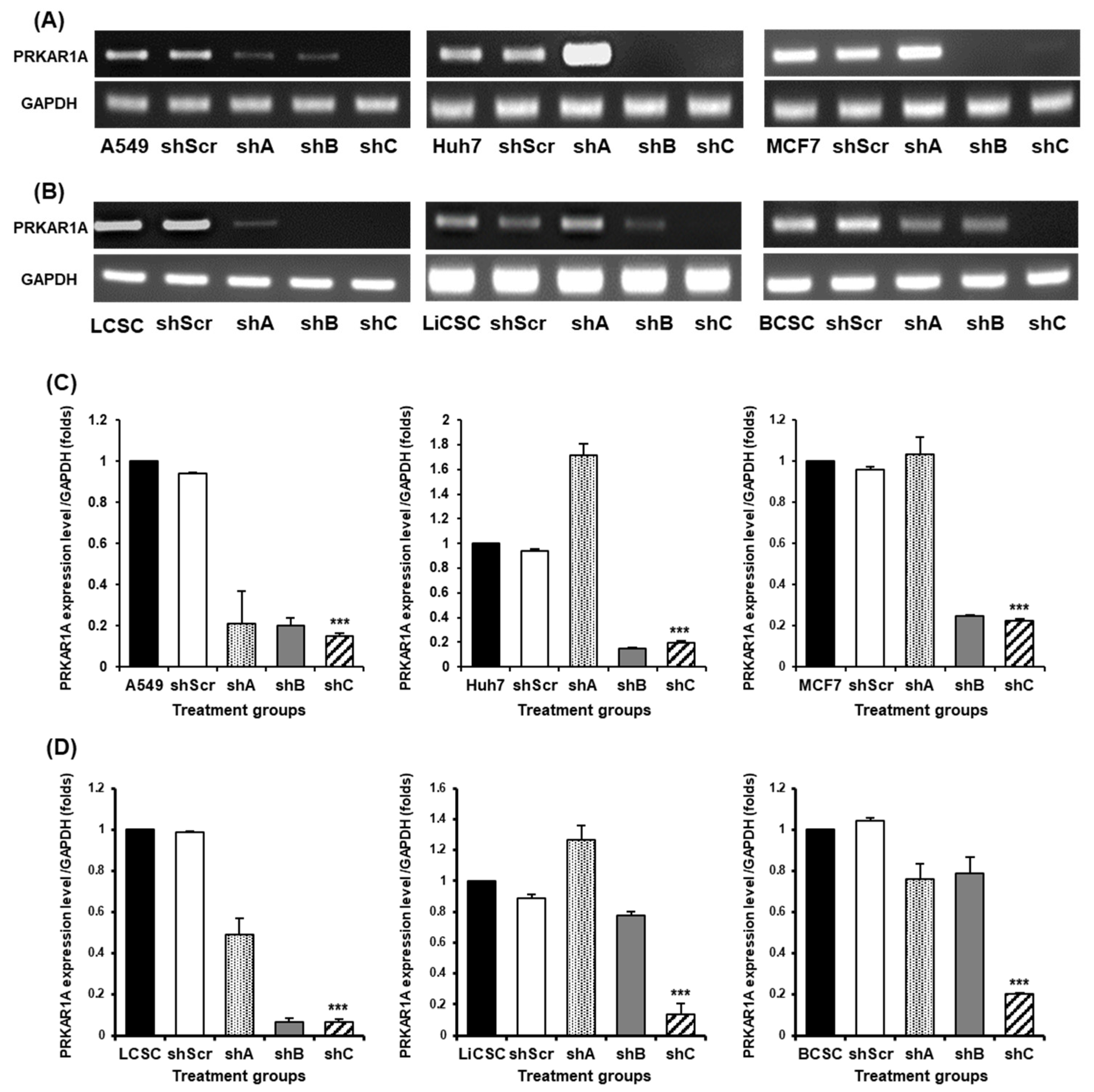

21]. To elucidate the biological function of PRKAR1A, we generated a series of shRNA, with shC identified as the most effective in all cells (

Figure 2).

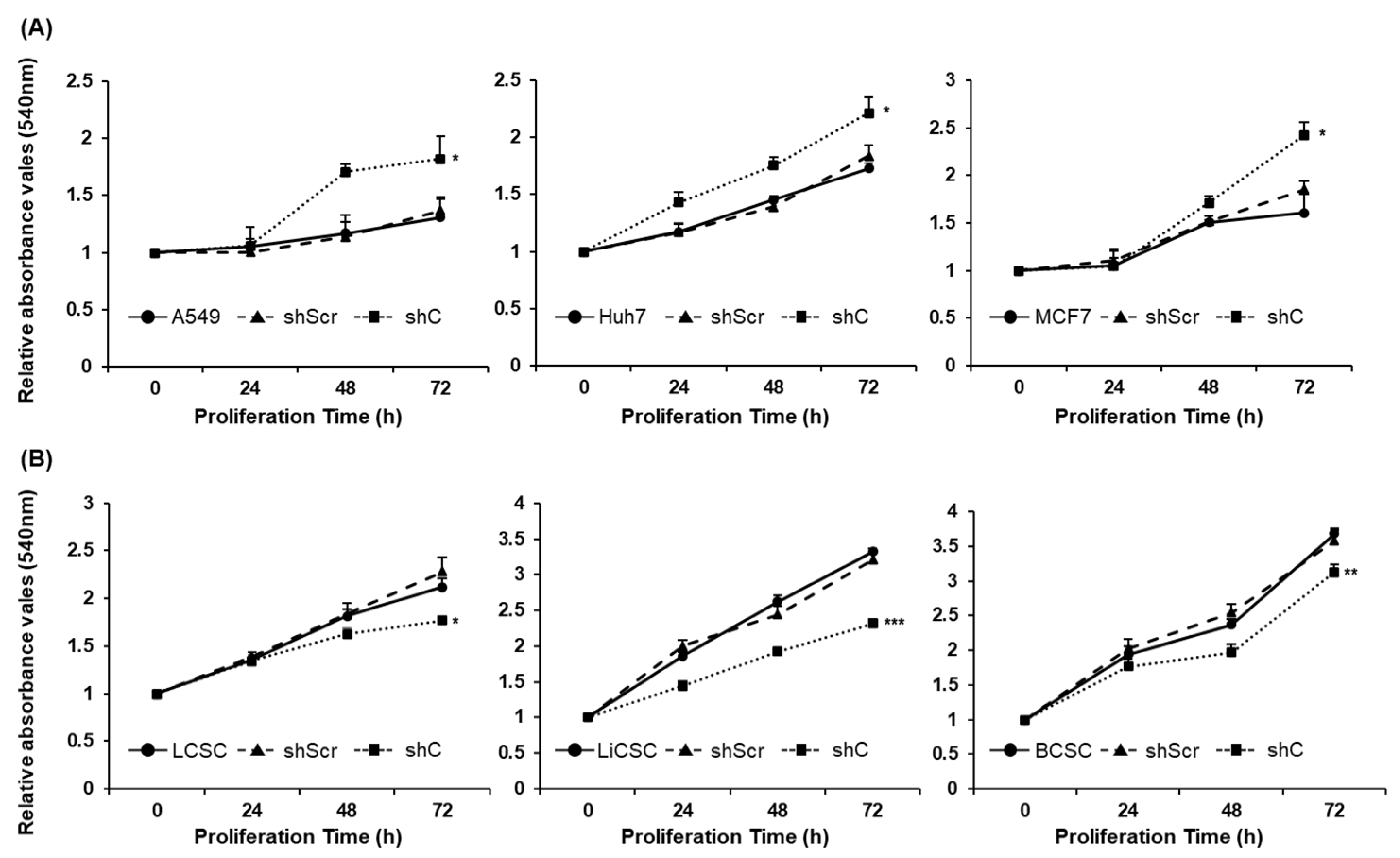

Our subsequent assessment of PRKAR1A’s impact on cancer cells and CSCs focused on key features of cancer growth and metastasis [

3,

22,

37], including short-term cell proliferation and long-term colony formation, both regulated by PRKAR1A in opposite directions between cancer cells and CSCs (

Figure 3,4). Understanding the opposing trends induced by PRKAR1A involved examining the alterations in the cell cycle based on cyclin D1 expression (

Figure 5). Cyclin D1, a crucial cell cycle regulator often overexpressed in cancer, plays a role in promoting entry into the S phase and to cancer growth [

23,

24]. Downregulation of PRKAR1A increased cyclin D1 expression and the S-phase of the cell cycle in cancer cells, while in CSCs, it decreased cyclin D1 expression, shortening the S-phase. This clearly indicates that PRKAR1A is likely associated with signaling pathways related to the cell cycle. Further evaluation of another major cancer characteristic, cell mobility [

3,

37], through a migration assay demonstrated that downregulation of PRKAR1A increased the migration of cancer cells but decreased the migration of CSCs (

Figure 6). These findings suggest that PRKAR1A regulates the biological functions of cancer cells and CSCs in opposite directions.

In elucidating the fundamental biological functions mediating these opposing roles in cancer and cancer stem cells, we considered the ERK pathway in cell signaling. This signal is a key pathway associated with cancer-related processes, such as cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis [

25,

26,

27]. Moreover, ERK phosphorylation is known to have a strong connection with the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [

28]. EMT is a process in which cells lose cell-cell adhesion, gain mobility and invasiveness, and transform into mesenchymal-like stem cells, with the ability to reversibly transition between epithelial and mesenchymal states [

30]. Given its implications in cancer malignancy, anticancer drug resistance, EMT is a crucial and well-recognized mechanism in cancer research [

38]. Furthermore, EMT is associated with the acquisition of stemness, a feature attributed to stem cells, characterized by their ability to self-replicate and differentiate into various cell types [

31,

32,

33]. Well-known stemness markers include Sox2 (sex determining region Y-box 2), Oct4 (octamer-binding transcription factor 4), and Nanog (Nanog homeobox), which are known to be highly expressed specifically in CSCs [

39]. It is also well known that these stemness markers are highly expressed in various types of cancer, including lung cancer, liver cancer, and breast cancer [

40,

41]. They are closely associated with cancer initiation, recurrence, increased invasiveness into other tissues or organs due to enhanced EMT, resistance to multiple anticancer drugs, and poor prognosis [

42,

43,

44]. Several mechanisms regulate stemness, including the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, Notch pathway, JAK/STAT pathway, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway [

39]. However, research on whether the ERK pathway regulates stemness remains limited. Therefore, we assessed whether PRKAR1A induces changes in biological functions, EMT, and the stemness abilities of cells through the ERK signaling pathway, and we confirmed this.

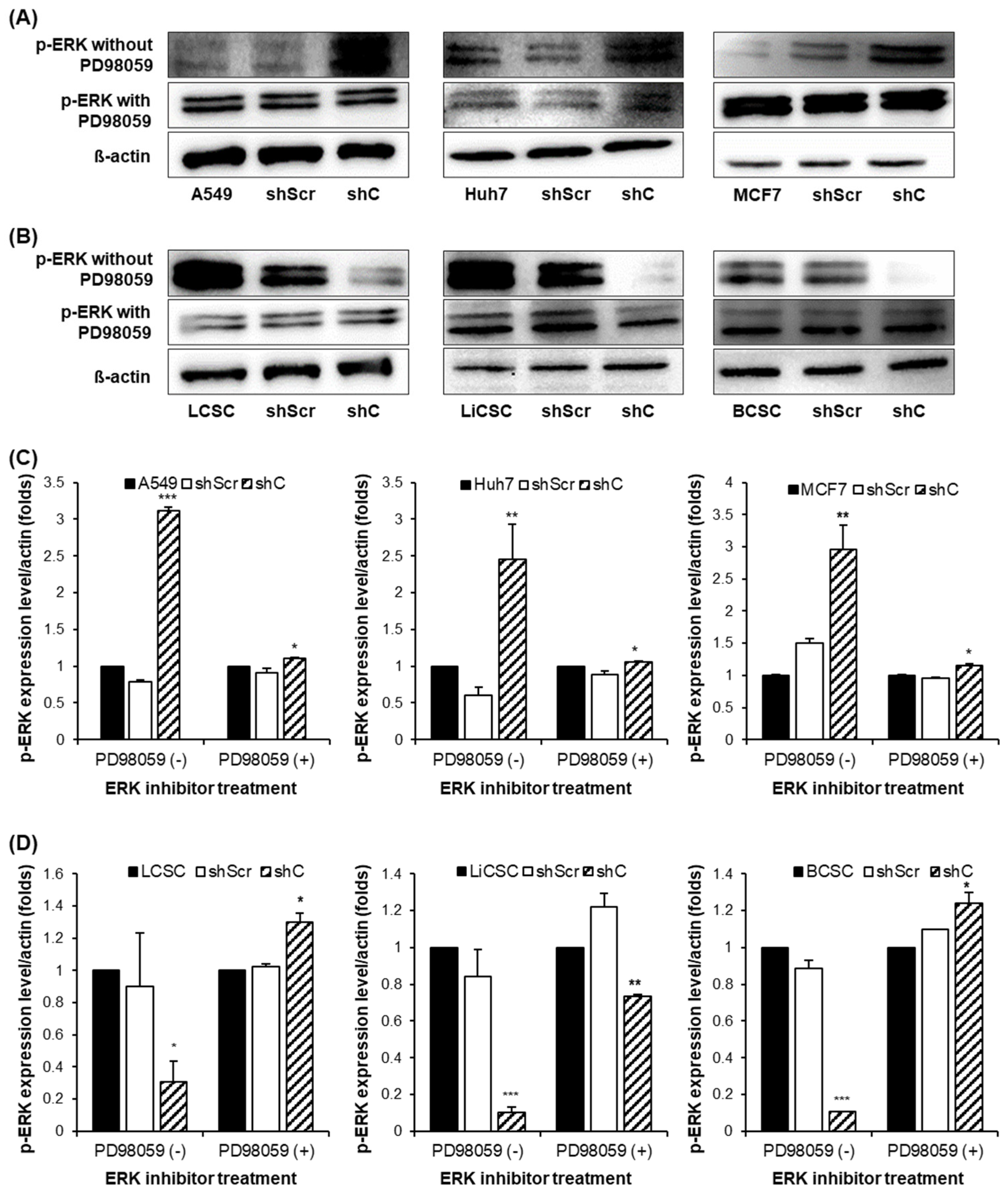

The results showed that p-ERK expression was increased in cancer cells and decreased in CSCs. Moreover, when treated with the ERK inhibitor PD98059, there was no observed change in the p-ERK, indicating that PRKAR1A can directly regulate the phosphorylation of ERK [

29] (

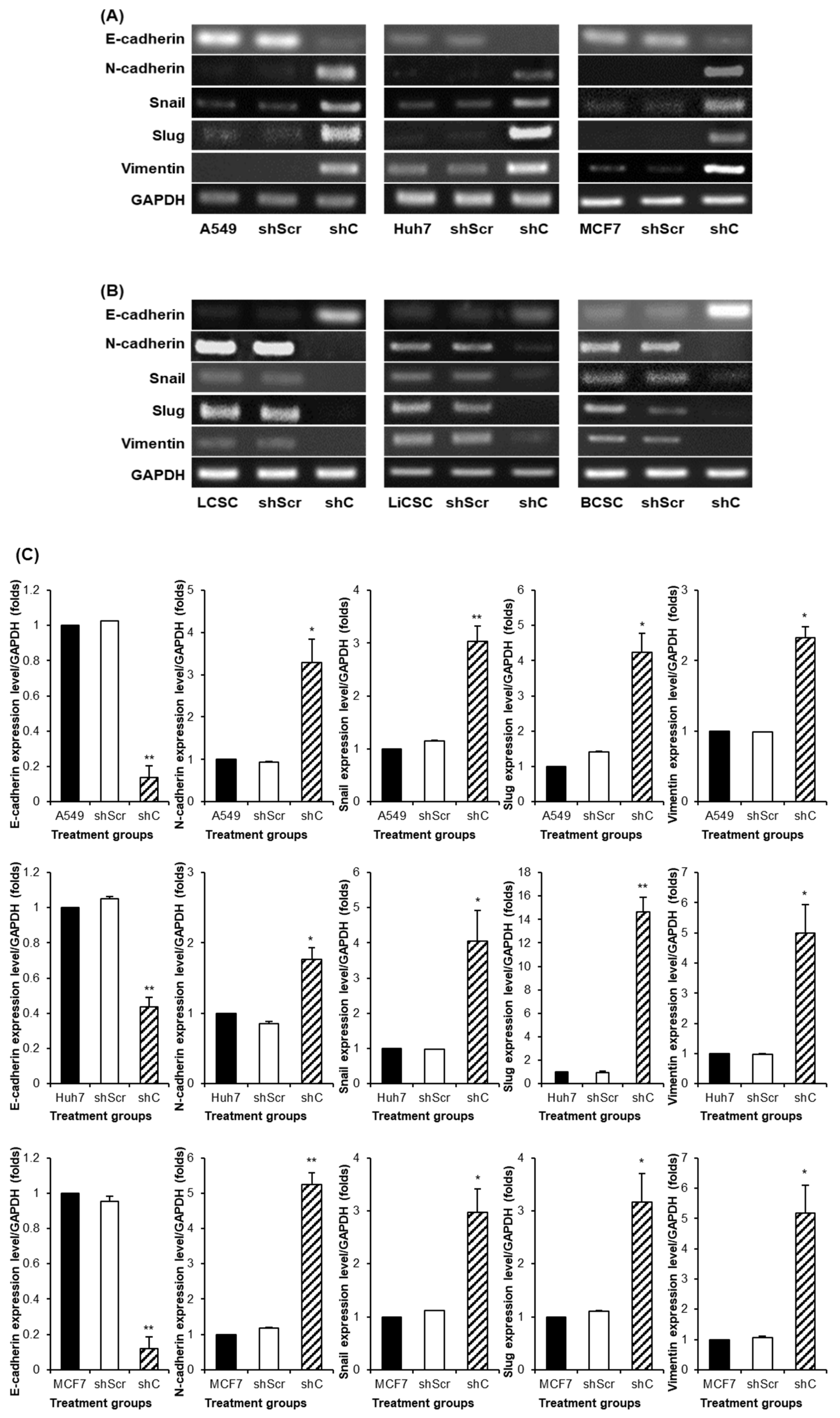

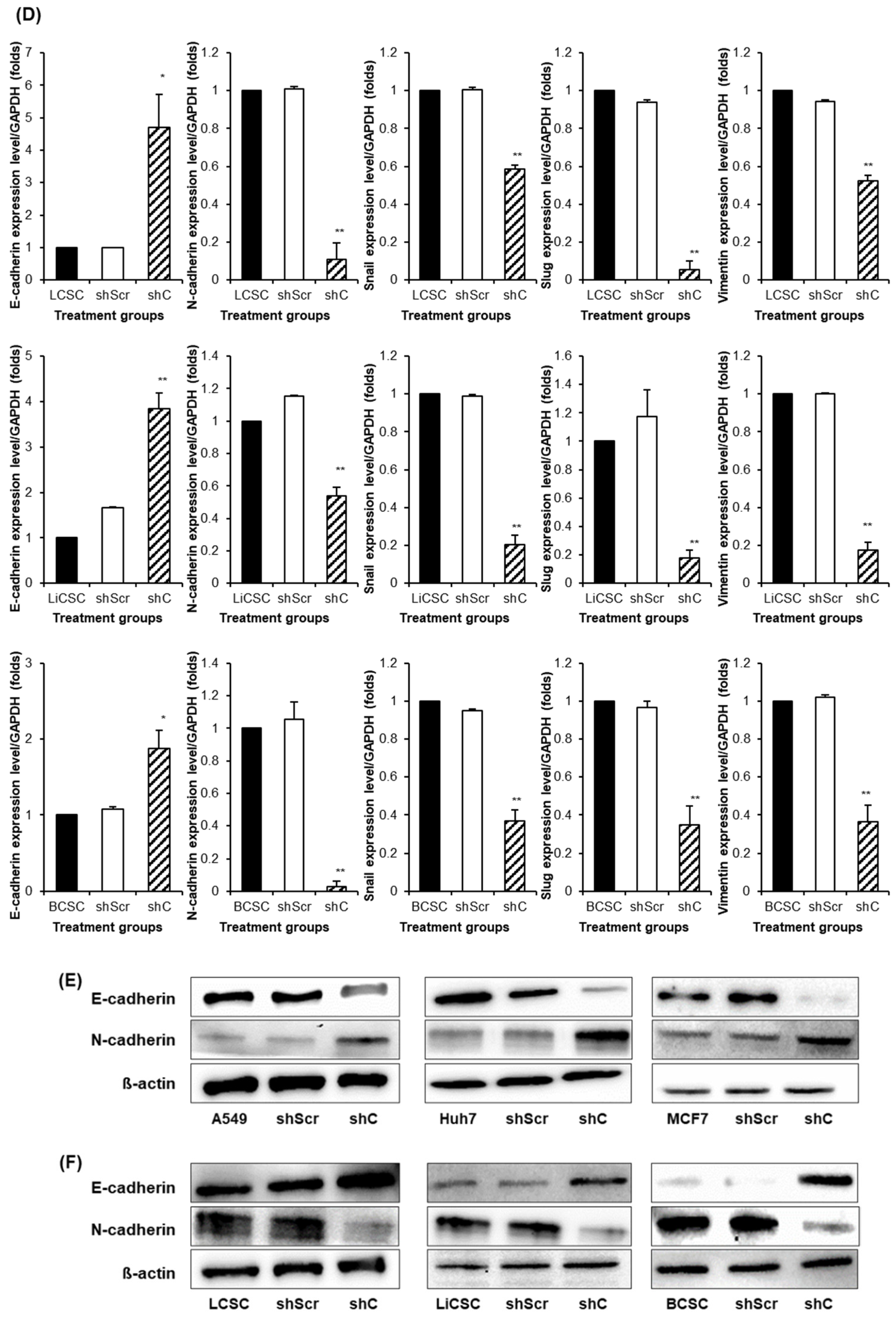

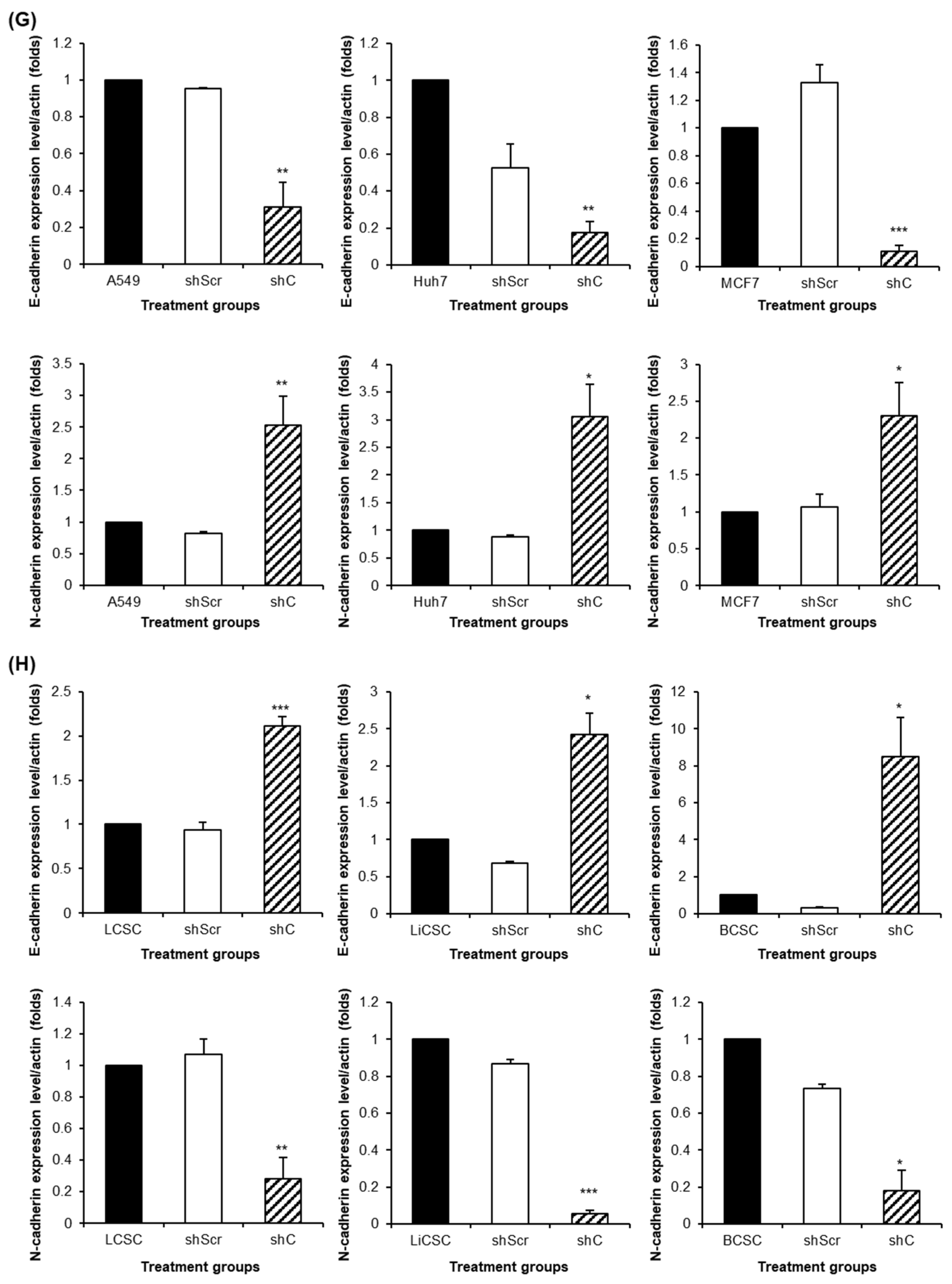

Figure 7). We further examined the reversible changes in the EMT mechanism due to the ERK phosphorylation by assessing the expression of specific epithelial (E) marker and mesenchymal (M) markers. In cancer cells, the ERK phosphorylation induced EMT, while in CSCs, it led to MET (

Figure 8). The associated changes in stemness markers (

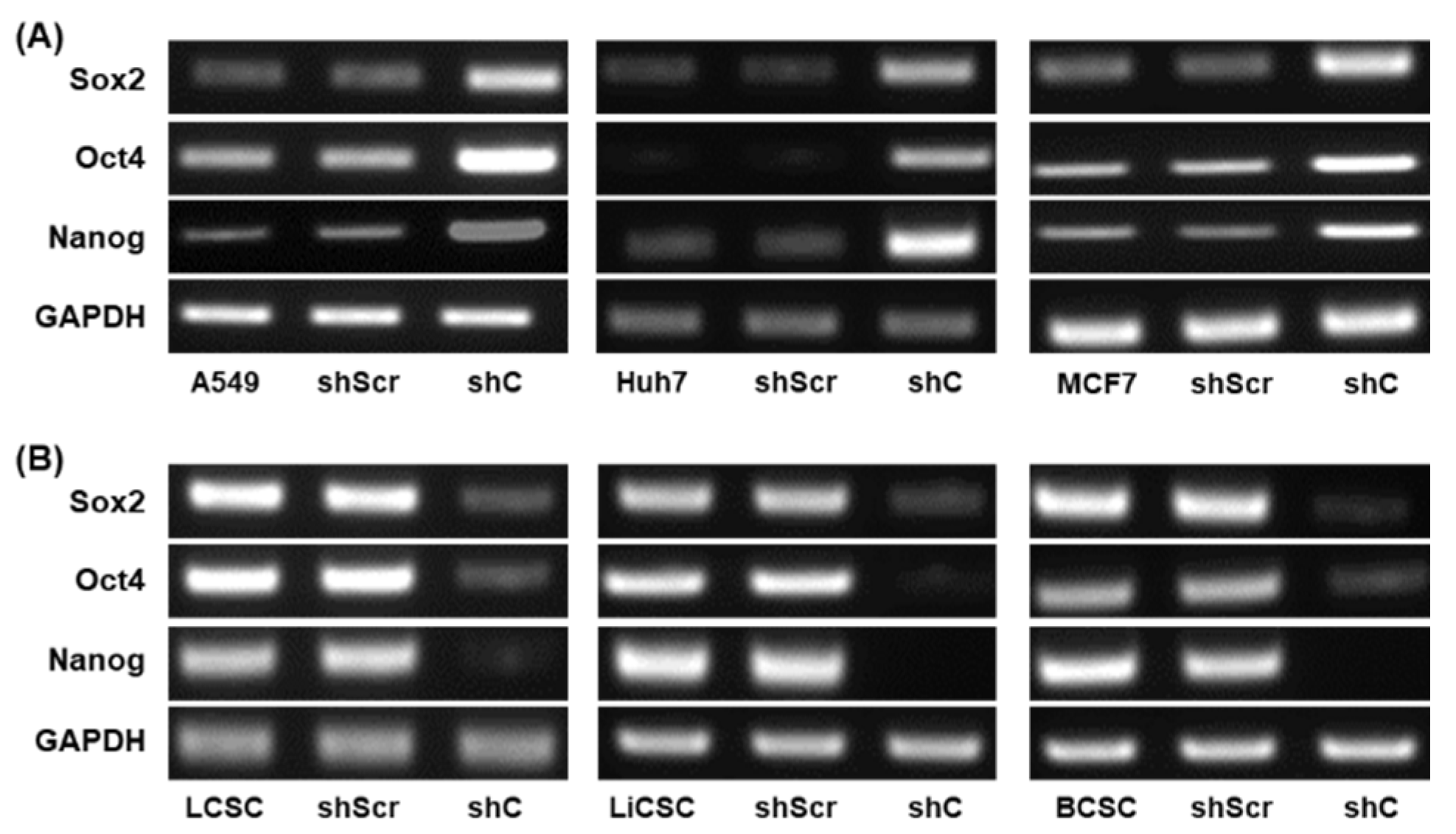

Figure 9) indicated that PRKAR1A regulates EMT and stemness through the ERK signaling pathway.

A successful approach in treating cancer involves early detection and removal through conventional therapy. However, over time, drug resistance increases, and further anticancer treatments become less effective. Considering the implications of EMT and stemness on chemoresistance [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44], we explored their role in cancer cells and CSCs treated with the chemotherapeutic agent DOX (

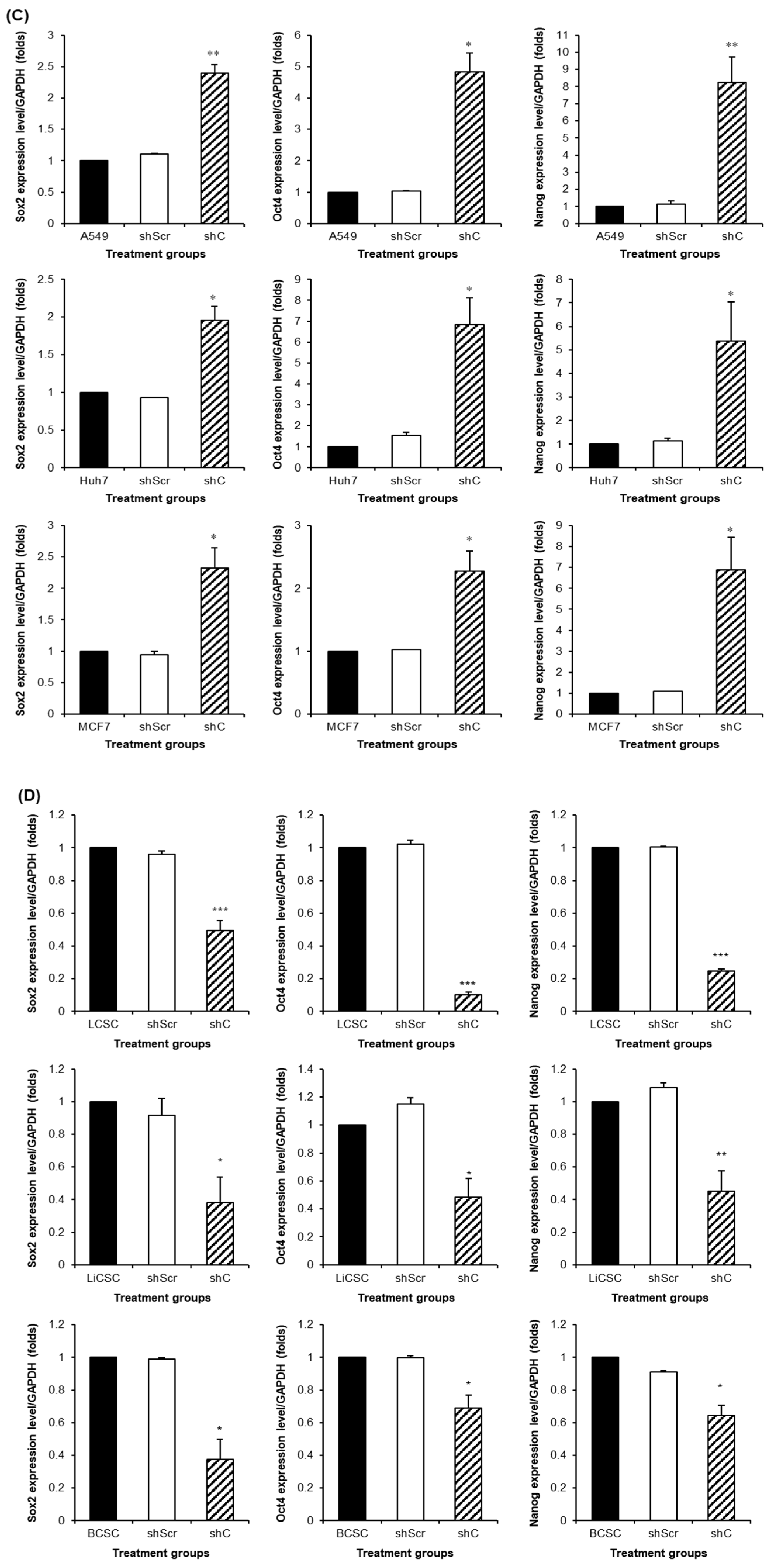

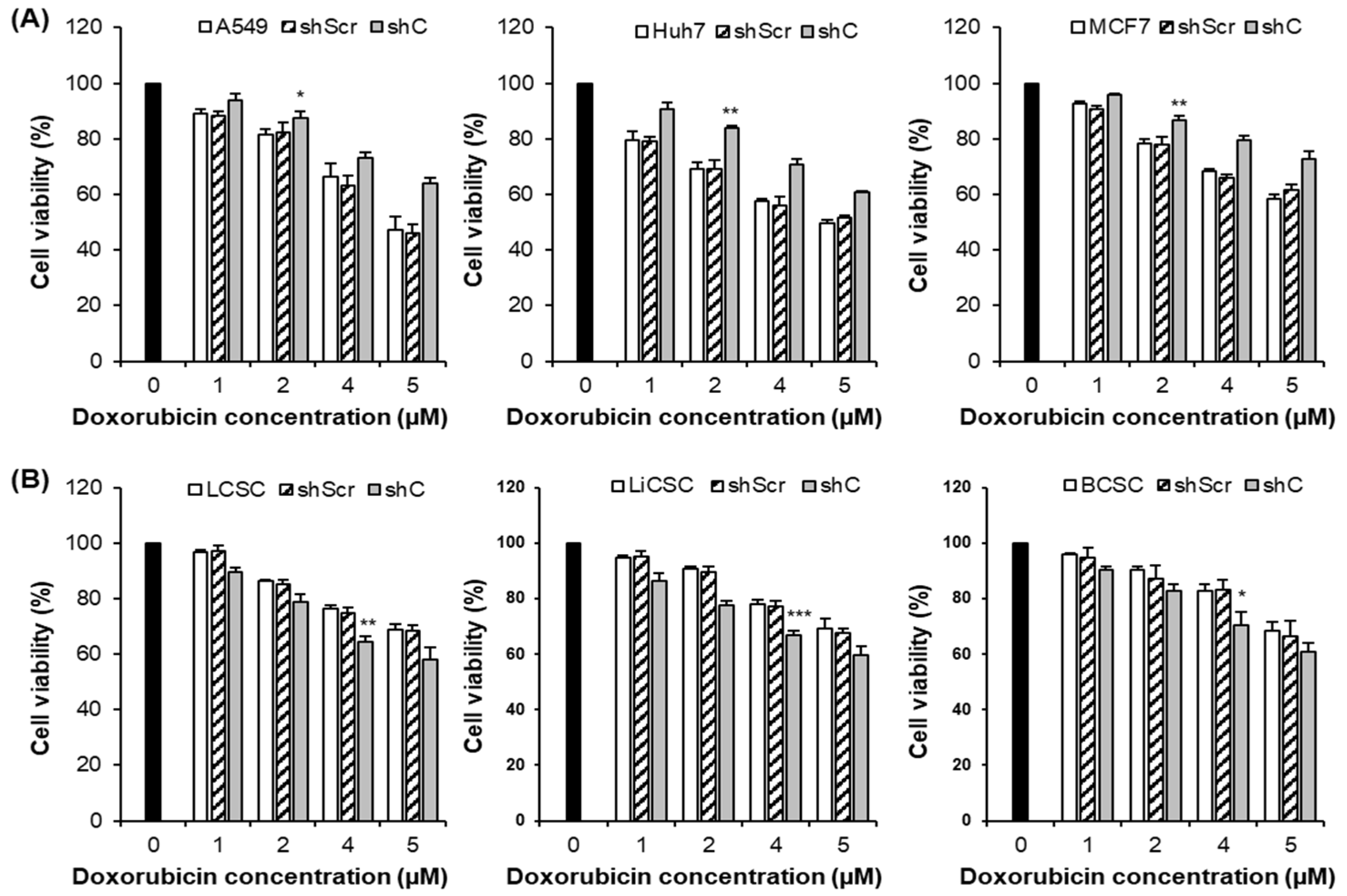

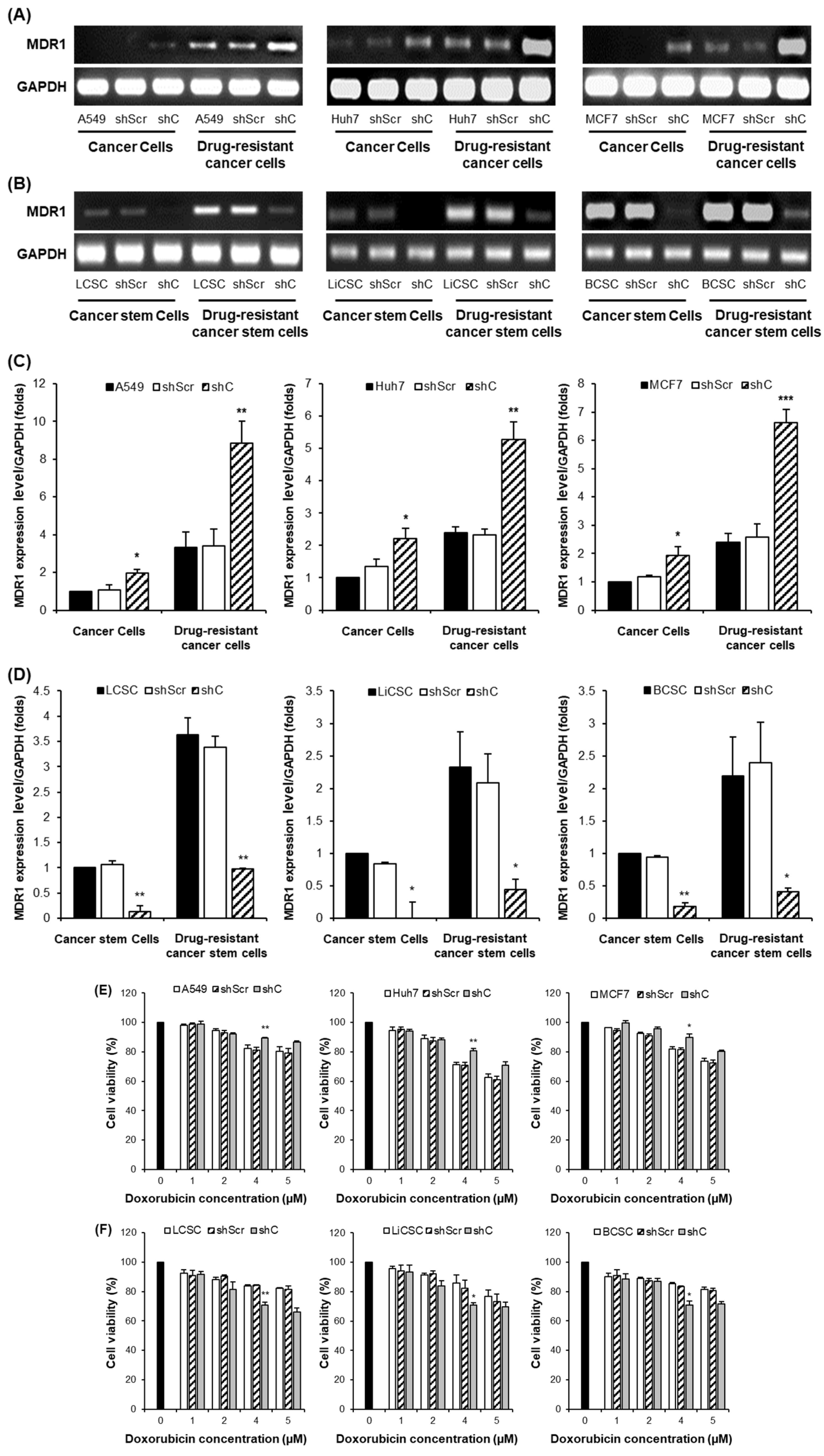

Figure 10 and 11). Downregulation of PRKAR1A reduced chemoresistance in CSCs, increasing cell death. The results collectively provide evidence that PRKAR1A can regulate cell chemoresistance.

To further investigate whether decreased PRKAR1A levels can reduce chemoresistance in cells with inherent drug resistance, we generated drug-resistant cancer cell lines and CSCs. The results mirrored those from

Figure 10, suggesting that PRKAR1A can overcome chemoresistance even in cells with inherent drug resistance (

Figure 12). Confirmation through the downregulation of the drug-resistant gene MDR1 emphasized PRKAR1A’s role in inducing chemoresistance in both cancer cells and CSCs through the regulation of MDR1 expression. MDR1, also known as ABCB1 (ATP-binding cassette transporter C1), is well-known for its role in transporting various therapeutic agents, including doxorubicin, methotrexate, edatrexate, daunorubicin, and others, out of the cell membrane, thereby regulating chemoresistance. It is particularly abundant in chemoresistant CSCs [

34,

35]. When we compared the expression of MDR1 between drug-resistant cell lines and regular cell lines, higher MDR1 expression in the drug-resistant cell lines was observed. Furthermore, the baseline expression of MDR1 was higher in CSCs compared to cancer cells. These results align with reports indicating that CSCs possess higher resistance to anticancer agents than cancer cells. Decreased expression of PRKAR1A in cancer cells led to increased MDR1 expression in both drug-resistant cell lines and regular cell lines. In contrast, in drug-resistant CSCs and regular CSCs cell lines, downregulation of PRKAR1A resulted in reduced MDR1 expression. This means that PRKAR1A can induce chemoresistance in both cancer cells and CSCs through the regulation of MDR1 expression.

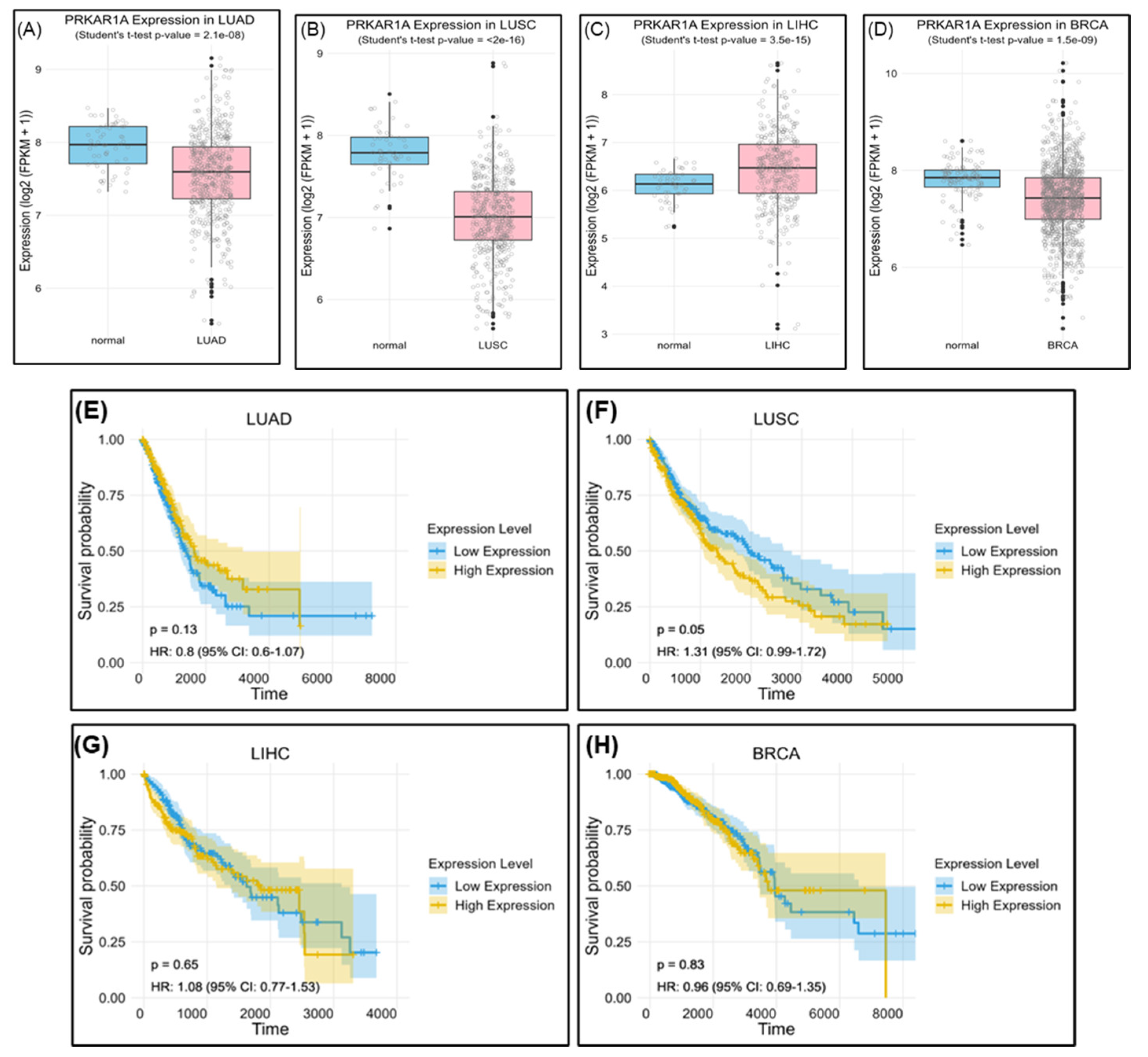

The evaluation of PRKAR1A expression in actual cancer patients using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) revealed lower expression in LUAD, LUSC, and BRCA compared to normal individuals, with significantly elevated levels in LIHC. However, high PRKAR1A expression consistently correlated with lower survival rates compared with when it is expressed ay low levels (

Figure 13). Of course, there are many variables, such as patient’s age, cancer grade, and previous treatment methods, to consider in this analysis, and further research is needed in the future. Nevertheless, these findings highlight the complex role of PRKAR1A in cancer prognosis and emphasize the importance of tailored analyses for different cancer types in biomarker development. Furthermore, an analysis of overall survival based on PRKAR1A expression revealed a consistent trend.

Taken together, there is a growing interest in the discovery of biomarkers that can potentially offer new directions for anticancer treatments to address the continually rising incidence and mortality rates of cancer [

12,

13]. In accordance with these research trends, this study focused on the discovery and validation of novel biomarkers with broad applicability across various cancer types. PRKAR1A, identified through proteomic analysis, emerged as a promising cell surface-expressed biomarker capable of regulating cancer biological functions, EMT, and stemness through ERK signaling pathway consequently diminishing the cell-killing effects associated with resistance to anticancer agents. Targeting PRKAR1A could offer a strategic approach to overcome conventional cancer treatment limitations and pave the way for new therapeutic directions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.1.1. Cancer cells

The cell lines A549 (human lung cancer cell), Huh7 (human liver cancer cell), MCF7 (human breast cancer cell) and UCB-MSC (umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cell) were all purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, VA, USA). A549 and Huh7 cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Hyclone, UT, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, UT, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS) (Hyclone, UT, USA). MCF7 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 Medium (Welgene, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea) containing 10% FBS and 1% PS. UCB-MSC cells were cultured in stem cell conditioned basal medium of KSB-3 (Kangstem Biotech, Seoul, South Korea) and added to KSB-3 supplements with 10% FBS. All cell cultures were incubated at 37℃ in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

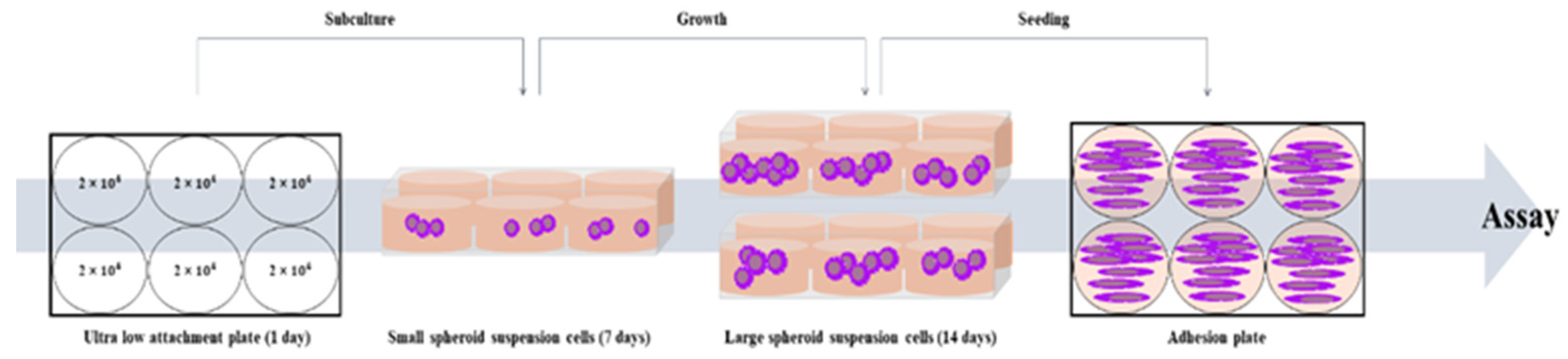

4.1.2. Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs)

The cell lines Lung cancer-derived stem cell (LCSC), Liver cancer-derived stem cell (LiCSC), and Breast cancer-derived stem cell (BCSC) were cultured in DMEM/F-12 Nutrient Mixture Ham (DMEM/F-12) (Welgene, Gyeongsan-si, Gueongsangbuk-do, Korea) containing 10% FBS, 1% PS, 5 µg/ml insulin (Invitrogen, CA, USA), 20 ng/ml EGF (Gibco), 20 ng/ml b-FGF (Gibco), 1% B27 (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The cancer cell lines were cultured in Costar® 6-well Clear Flat Bottom Ultra-Low Attachment Multiple Well Plates (Corning, NY, USA), with appropriate medium. Cancer cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 10

4 cells/well to make CSCs. All CSCs were sub-cultured on the 7th day of culture and incubated for 2 weeks. All cell cultures were incubated at 37℃ in a humidified incubator with 5% CO

2 [

45].

Scheme 1.

The scheme of CSCs culture from cancer cells.

Scheme 1.

The scheme of CSCs culture from cancer cells.

4.2. Mass spectometry analysis

The proteomic analysis from cancer cells and CSCs was conducted similarly to our previous paper [

46]. In brief, the process involved: Cancer cells and CSCs were lysed in a 30 µL buffer at 4°C, and the resulting supernatant underwent tryptic digestion after centrifugation. Protein concentration was determined using the Coomassie Plus Assay Reagent. Lysate proteins were treated with DTT and IAA, followed by trypsin digestion. A cleanup with an MCX cartridge involved equilibration, washing, and elution steps using specific solutions. The eluate was dried, and peptides were either extracted with formic acid for LC injection or stored at -20°C before analysis. Samples underwent separation through online reversed-phase chromatography using Thermo Scientific equipment. This included an Easy nano LC II autosampler, peptide trap EASY-Column, and analytical EASY-Column. Electrospray ionization was performed with a nano-bore stainless steel online emitter. The chromatography system was coupled with an LTQ Velos Orbitrap mass spectrometer featuring an ETD source. A data-dependent switching mode was applied to enhance peptide fragmentation, and protein identification utilized Sorcerer 2 against the 2014 UniProt human DB. Set tolerances included 1.0 Da for fragment mass, 25 ppm for peptide mass, and a maximum of 2 missed cleavages. Result filters were applied, considering a minimum number of peptides per protein, with static and variable modifications. Processed datasets were transformed to .sf3 files using Scaffold 3 program.

4.3. RNA extraction and conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested and total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s manual using TRIzol (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Then, it was quantified by Nanodrop

TM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The extracted RNA was converted into complementary DNA (cDNA) with 2X RT Pre-Mix (Solgent, Daejeon, South Korea). The synthesized cDNA was subjected to conventional PCR using a 2X Taq PCR Pre-Mix (Solgent, Daejeon, South Korea) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. All samples synthesized by conventional PCR were confirmed by separation through 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (Vivantis, Molecular Biology Grade, USA) in TAE buffer. Gel images were taken using a chemiluminescence detection system (VilberLourmat, Everhardzell, Germany). The primer sequences for performing PCR are as shown in

Table 1.

4.4. Cell proliferation assay

Cancer cells were seeded onto 6-well plates at 1.5 × 105 cells/well and CSCs were seeded onto 6-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well. Then shRNA series were transfected into each cell lines as described, and then 4 h later, cells were seeded in triplicate onto a 96-well plate at a density of 8 × 103 cells/well. After 48 h, cell viability was measured by 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT assay) (Sigma, UK) depending on time to confirm cell proliferation. After removing the culture medium, 100 µl of MTT reagent (2 mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated at 37℃ in a CO2 incubator for 4 h. Following the incubation period, the MTT reagent was removed, and 100 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well to react with the generated formazan for 20 minutes. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader (Versamax microplate reader, Associates of cape cod incorporated, MA, USA). Cell proliferation was compared relative to the 0 h time point.

4.5. Cell colony formation assay and crystal violet stain

Cancer cells and CSCs were seeded at 1 × 103 cells/well onto 6-well plate with appropriate medium, and then incubated for 10 days. The cell culture medium was replaced every 2 days. When the visible colony appeared, the cells were washed three times in PBS. Next, the cells were fixed with methanol for 20 minutes and stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature. After staining and visually confirming the formation of colonies, crystal violet in the colonies was dissolved by 100% methanol. The dissolved crystal violet was then distributed into a 96-well plate with 100 µl in each well and measured for absorbance at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Versamax microplate reader, Associates of cape cod incorporated, MA, USA). The measured values were compared to untreated cells, which were considered as 100%, to assess the relative differences in the other samples.

4.6. Cell cycle assay by flow cytometry

Cancer cells and CSCs after transfected with shPRKAR1A for 48 h were collected and washed with cold PBS for three times. And then, cells were fixed with 70% ethanol at 4℃ for 2 h. After washing cold PBS for three times, the cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, UAS) at 4℃ overnight. Cell cycles were analyzed with Novocyte Flow Cytometer (ACEA Bioscience Inc, San Diego, CA, USA).

4.7. Wound healing scratch assay

After transfection as described, cancer cells were seeded at 6 × 104 cells/well and at 8 × 104 cells/well for CSCs onto 24-well plates. When the confluence of cells prepared in each group reaches 80%, they were scraped to make it uniformly wide at regular internal with a 200 µl sterile pipette tip. The photographs were taken at 0 and 12 h after scratch creation with a microscope (Nikon eclipse Ts2R). The ratio of cell movement in the 12 h sample compared to the 0 h sample was quantitatively analyzed by the image J program.

4.8. Western blot analysis

The protein extraction was performed from groups subjected to transfection with shC for 48 h, followed by a 1 h treatment with PD98059 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at a concentration of 15 µM, and compared with the group that did not receive the treatment. Samples were harvested and washed with cold PBS for 2 times. Cell pellets were lysed by using EzRIPA Lysis Kit (RIPA buffer and inhibitors) (DAWINBIO Inc., Gyeonggido, South Korea) for 15 minutes on ice. Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 RPM for 15 minutes at 4℃, and protein supernatant was measured by using the BCA protein assay reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, UAS). Equal amounts of proteins (15 µg) were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The proteins were transferred onto Immobilon®-P PVDF membrane (Millipore Co., MA, USA) and blocked with 3% skim milk for 1 h. Then, the membranes were incubated with 3% skim milk containing primary antibodies at 4℃ overnight. The primary antibodies against β-actin (1:1000, sc-4778, Santa Cruz., CA, USA), E-cadherin (1:1000, 3195, Cell Signaling Technology (CST), Danvers, MA, USA), N-cadherin (1:500, 14215S, CST), p-ERK (1:1000, sc-7383, Santa Cruz.) were used. After incubation, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horse radish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibody. For the detection of the secondary antibodies targeting β-actin, N-cadherin, and p-ERK, HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:10,000, 31430, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used, whereas HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG Antibody (1:10,000, 7074, CST) were used for capturing E-cadherin. The protein band were developed with a chemiluminescent ECL reagent (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (VilberLourmat, Everhardzell, Germany). For all primary antibodies were normalized to β-actin. The quantification of protein bands was performed using Image J software.

4.9. Drug resistance assay

After the transfection as described, cancer cells and CSCs were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 8 × 103 cells/well. Subsequently, the anti-cancer drug, doxorubicin (Doxorubicin hydrochloride; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered at concentrations of 1, 2, 4, and 5 µM for 24 h. Following treatment, the medium was replaced with fresh medium, allowing a 48 h recovery period for the cells. Subsequent MTT assay was conducted to measure cell viability. After media removal, 100 µl of MTT (Sigma) reagent was added and incubated for 4 h at 37℃. The formazan crystals formed by the cells were dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) and measured at 540 nm using VerxaMax (Microplate Reader, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The cells treated with different concentration of doxorubicin were quantitatively compared to the values of untreated cells, and the results were represented graphically.

4.10. Generation of chemoresistant cell lines

After treating the cells with the anti-cancer drug, doxorubicin, at a concentration of 2 µM for 24 h, a recovery period of 48 h was provided by changing to a fresh medium. This process was repeated three times, and then morphological changes of the surviving cells were examined using Zoe (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California). Following the development of anti-cancer drug resistant in the cells, as described, shPRKAR1A was transfected. Subsequently, conventional PCR and MTT assays were conducted.

4.11. Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was detected using the FITC-Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit 1 (BD, New Jersey, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sample were harvested and washed twice with cold PBS and re-suspended in 1X binding buffer at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml. The cells were transferred to 100 µl of the solution (1 × 105 cells/ml), 5 µl of FITC-Annexin V, and 5 µl propidium iodide (PI) were added to stain for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature. Next, 400 µl of 1X binding buffer was added to each sample. Finally, apoptotic levels were analyzed by flow cytometry (Novo Cyte flow cytometer, ACEA Bioscience Inc., USA). Data were analyzed using Novoexpress software (ACEA Biosciences Inc., USA).

4.12. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Expression and survival data for lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), and breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA) were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) via the OncoDB database. The data were subjected to preprocessing, which included normalization of expression values and confirmation of data integrity. The final dataset consisted of normalized expression values for the PRKAR1A gene and corresponding patient survival information, including time-to-event and vital status.

4.13. Statistical Analysis of Expression Data

Differential expression analysis was performed to compare PRKAR1A expression levels between cancerous and normal tissue samples. For this purpose, a two-sample t-test was employed, assuming unequal variances. The t-test was conducted to ascertain the significance of expression differences for PRKAR1A between the cancer samples and matched normal controls.

4.14. Survival Analysis

Survival analysis was conducted to investigate the association between PRKAR1A expression levels and patient prognosis. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted to visualize differences in survival probabilities between high and low PRKAR1A expression groups. The survival curves were compared using the log-rank test to evaluate the statistical significance of differences in survival times. The Cox proportional hazards model was utilized to estimate hazard ratios, providing a measure of the effect size of PRKAR1A expression on survival. The model was adjusted for potential confounders, including age, sex, and cancer stage. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated to assess the relative risk of mortality associated with PRKAR1A expression levels. Differential expression analysis was performed to compare PRKAR1A expression levels between cancerous and normal tissue samples. For this purpose, a two-sample t-test was employed, assuming unequal variances. The t-test was conducted to ascertain the significance of expression differences for PRKAR1A between the cancer samples and matched normal controls.

4.15. Software

All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 3.6.3). The survival package was used for survival analyses, and the ggplot2 package was employed for generating boxplots and Kaplan-Meier plots. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered indicative of statistical significance.

4.16. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed at least three times repetitive experiments, and the measured data were calculated as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and presented as a graph. The significance test between groups was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Statistical differences were indicated in the figures. *P < 0.05, ** P <0.01, and *** P <0.001. For statistical analysis, SPSS statistics software for Windows, Version 18 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) was used.

Figure 1.

Proteomic analysis results for biomarker candidate and validation of PRKAR1A expression in each cell lines. Venn Diagram depicting the results of proteomic analysis (A). The validation of PRKAR1A in each cell lines (B). Quantitative values of PRKAR1A expression were normalized by GAPDH (C). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, as compared with UCB-MSC versus other cell lines.

Figure 1.

Proteomic analysis results for biomarker candidate and validation of PRKAR1A expression in each cell lines. Venn Diagram depicting the results of proteomic analysis (A). The validation of PRKAR1A in each cell lines (B). Quantitative values of PRKAR1A expression were normalized by GAPDH (C). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, as compared with UCB-MSC versus other cell lines.

Figure 2.

The selection of optimal shRNA for PRKAR1A silencing in cancer cells and CSCs. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) series were constructed in psi-LVRU6GP vector to effectively knock-down PRKAR1A gene in the cancer cells and CSCs. Transfection efficiency of PRKAR1A by constructed shRNAs through conventional PCR (A-B). Quantitative data of PRKAR1A expression was normalized by GAPDH (C-D). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). ***P < 0.001, as compared with shScr.

Figure 2.

The selection of optimal shRNA for PRKAR1A silencing in cancer cells and CSCs. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) series were constructed in psi-LVRU6GP vector to effectively knock-down PRKAR1A gene in the cancer cells and CSCs. Transfection efficiency of PRKAR1A by constructed shRNAs through conventional PCR (A-B). Quantitative data of PRKAR1A expression was normalized by GAPDH (C-D). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). ***P < 0.001, as compared with shScr.

Figure 3.

Opposing cell proliferation by PRKAR1A silencing in cancer cells and CSCs. Cancer cells (A) and CSCs (B) were assessed for proliferation rate as o, 24, 48, and 72 h after shRNA treatment. Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 3.

Opposing cell proliferation by PRKAR1A silencing in cancer cells and CSCs. Cancer cells (A) and CSCs (B) were assessed for proliferation rate as o, 24, 48, and 72 h after shRNA treatment. Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 4.

The change of colony formation ability by PRKAR1A knock-down. The generated colonies were fixed with methanol and visually confirmed through crystal violet staining (A-B). The rectangular box represents a portion where individual single colonies were well observed. This area was magnified at a 100-fold scale for observation. After dissolving crystal violet in methanol, quantification was performed to measuring absorbance at 570 nm in a 96-well plate (C-D). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 4.

The change of colony formation ability by PRKAR1A knock-down. The generated colonies were fixed with methanol and visually confirmed through crystal violet staining (A-B). The rectangular box represents a portion where individual single colonies were well observed. This area was magnified at a 100-fold scale for observation. After dissolving crystal violet in methanol, quantification was performed to measuring absorbance at 570 nm in a 96-well plate (C-D). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the cell cycle and induced changes in cyclin D1 in PRKAR1A sh RNA-treated cancer cells and -CSCs. The expression of cyclin D1 post-PRKAR1A shRNA (A-B). Quantitative data of cyclin D1 expression relative to GAPDH (C-D). Analysis of cell cycle using flow cytometry (E-F). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the cell cycle and induced changes in cyclin D1 in PRKAR1A sh RNA-treated cancer cells and -CSCs. The expression of cyclin D1 post-PRKAR1A shRNA (A-B). Quantitative data of cyclin D1 expression relative to GAPDH (C-D). Analysis of cell cycle using flow cytometry (E-F). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 6.

Cell migration ability by downregulation of PRKAR1A. Images and crystal violet staining to confirm cell migration at 0 and 12 h (A-B). The migration area was measured using Image J. The wound-like area was quantified at 12 h relative to the baseline at 0 h and presented graphically (C-D). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 6.

Cell migration ability by downregulation of PRKAR1A. Images and crystal violet staining to confirm cell migration at 0 and 12 h (A-B). The migration area was measured using Image J. The wound-like area was quantified at 12 h relative to the baseline at 0 h and presented graphically (C-D). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 7.

Comparison of p-ERK expression by PRKAR1A downregulated in cancer cells and CSCs. The changes in the band of p-ERK expression by western blot (A-B). Quantification expression level of p-ERK expression was normalized by β-actin (C-D). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 7.

Comparison of p-ERK expression by PRKAR1A downregulated in cancer cells and CSCs. The changes in the band of p-ERK expression by western blot (A-B). Quantification expression level of p-ERK expression was normalized by β-actin (C-D). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 8.

The change of EMT and MET in cancer cells and CSCs according to PRKAR1A expression. The expression of EMT markers (A-B) and its quantitative data (C-D), western blot analysis of EMT and MET (E-F) and its quantitative data (G-H). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 8.

The change of EMT and MET in cancer cells and CSCs according to PRKAR1A expression. The expression of EMT markers (A-B) and its quantitative data (C-D), western blot analysis of EMT and MET (E-F) and its quantitative data (G-H). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 9.

The changed expression of stemness biomarkers by PRKAR1A shRNA in cancer cells and CSCs. PCR band of stemness biomarkers in transcriptomic level (A-B). Quantitative data represented using GAPDH (C-D). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 9.

The changed expression of stemness biomarkers by PRKAR1A shRNA in cancer cells and CSCs. PCR band of stemness biomarkers in transcriptomic level (A-B). Quantitative data represented using GAPDH (C-D). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with shC versus shScr groups.

Figure 10.

Cancer cell killing effects by PRKAR1A shRNA treatment against anticancer agents. The anticancer drug resistance in cells with reduced PRKAR1A expression was assessed using the MTT assay. Cells were treated with doxorubicin (DOX) at concentrations of 0, 1, 2, 4, and 5 µM for 24 h, and cell viability was determined (A-B). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared of the group treated with shC+DOX to cells treated with shScr+DOX, as well as cells without any treatment.

Figure 10.

Cancer cell killing effects by PRKAR1A shRNA treatment against anticancer agents. The anticancer drug resistance in cells with reduced PRKAR1A expression was assessed using the MTT assay. Cells were treated with doxorubicin (DOX) at concentrations of 0, 1, 2, 4, and 5 µM for 24 h, and cell viability was determined (A-B). Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared of the group treated with shC+DOX to cells treated with shScr+DOX, as well as cells without any treatment.

Figure 11.

The induction comparison of cell death by PRKAR1A knockdown in cancer cells and CSCs. The apoptosis assay was performed with annexin-V-FITC/PI flow cytometry analysis (A-B). Cell death was represented graphically as the sum of all cell death values in quadrants 1, 2, and 4. Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01 for the comparison of shC+DOX- and shScr+DOX-treated groups.

Figure 11.

The induction comparison of cell death by PRKAR1A knockdown in cancer cells and CSCs. The apoptosis assay was performed with annexin-V-FITC/PI flow cytometry analysis (A-B). Cell death was represented graphically as the sum of all cell death values in quadrants 1, 2, and 4. Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01 for the comparison of shC+DOX- and shScr+DOX-treated groups.

Figure 12.

MDR1 gene expression and cancer cell effects by PRKAR1A down-regulating in chemoresistance cell lines. MDR1 expression comparison (A-D) and cytoxic effects (E-F) in anticancer drug-resistant cancer cells and CSCs. Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 for the comparison of shScr ans shC.

Figure 12.

MDR1 gene expression and cancer cell effects by PRKAR1A down-regulating in chemoresistance cell lines. MDR1 expression comparison (A-D) and cytoxic effects (E-F) in anticancer drug-resistant cancer cells and CSCs. Data shown represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 for the comparison of shScr ans shC.

Figure 13.

Survival rate according to PRKAR1A expression in clinical patients. Comparison of PRKAR1A expression between normal and cancer patients (A), survival rate graph based on PRKAR1A expression (B).

Figure 13.

Survival rate according to PRKAR1A expression in clinical patients. Comparison of PRKAR1A expression between normal and cancer patients (A), survival rate graph based on PRKAR1A expression (B).

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for PCR analysis.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for PCR analysis.

| Primer |

Forward (5’-3’) |

Reverse (5’-3’) |

| GAPDH |

AGGGCTGCTTTTAACTCTGGT |

CCCCACTTGATTTTGGAGGGA |

| PRKAR1A |

GCAGCCACTGTCAAAGCAAA |

GGTTCTCCCTGCACCACAAT |

| E-cadherin |

GCTTTGACGCCGAGAGCTA |

CTTTGTCGACCGGTGCAATC |

| N-cadherin |

AGGCTTCTGGTGAAATCGCA |

TGGAAAGCTTCTCACGGCAT |

| Snail |

GCTGCAGGACTCTAATCCAGAGTT |

GACAGAGTCCCAGATGAGCATTG |

| Slug |

AGATGCATATTCGGACCCAC |

CCTCATGTTTGTGCAGGAGA |

| Vimentin |

CGAAAACACCCTGCAATCTT |

TCCAGCTTCCTGTAGGT |

| Sox2 |

GCTACAGCATGATGCAGGACCA |

TCTGCGAGCTGGTCATGGAGTT |

| Oct4 |

CCTGAAGCAGAAGAGGATCACC |

AAAGCGGCAGATGGTCGTTTGG |

| Nanog |

CTCCAACATCCTGAACCTCAGC |

CGTCACACCATTGCTATTCTTCG |

| Cyclin D1 |

AGCTGTGCATCTACACCGAC |

GAAATCGTGCGGGGTCATTG |

| MDR1 |

CCCATCATTGCAATAGCAGG |

GTTCAAACTTCTGCTCCTGA |