1. Introduction

Lasers Scanners (or LiDAR devices - Light Detection And Ranging) are essential tools used for instrumentation. One of their great advantages lies in calculating depth, format and size of objects from their data. In the current context, these devices have been used to enable robots to move independently, autonomously and intelligently through indoor settings such as factories corridors and warehouses [

1]. Among the various types of sensors that can be used in robotics, laser sensors are usually most applied for time series [

2], point clouds [

3,

4] and regular angular depth data [

5].

A notorious example of a widely applied technique that uses lasers scanners is Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM), the procedure of autonomously building a map while a robot is localizing itself in the environment [

6]. Researches related to this topic within the field of mobile robotics have remained popular for a long time, and recently more effort has been made to contribute to the manufacture of intelligent and autonomous vehicles [

7,

8], field in which many of the works focus on object detection methods using 3D LiDAR [

9,

10,

11]. By its turn, 2D LiDARs are preferred in many mobile robotics applications due to its low cost and high degree of accuracy [

12]. The application also plays a role in the choice of sensor. For example, in places such as electrical substations, optical sensors are preferred for getting distance information because they do not suffer interference from the large electromagnetic fields [

13].

Besides the approaches mentioned above, there are many others that motivate and drive this works’ purpose. In particular the use of laser scanners for object detection and tracking (including cases in which both agent and objects are mobile) [

14,

15,

16,

17], object identification and segmentation from local environment [

18,

19,

20] and object feature extraction [

21]. These implementations have deep impact on autonomous robotics and decision making using little or no previous knowledge about the environment and objects, nevertheless accurately inferring information and executing tasks based on such data.

In yet another similar sense, SLAM implementations frequently focus on building and self-correcting a map or CAD model map, based on laser scanner data. Generally, many such techniques apply triangulation, environment landmarks [

4] and object features detection [

22], for systematic odometry error compensation in both indoor [

23,

24,

25] and outdoor [

26,

27] data. For the case in which a map is already available, the use of 2D LiDAR is also attractive. For instance, a fast obstacle detection technique for mobile robot navigation using a 2D-LiDAR scan and a 2D map is proposed in [

28].

Nonetheless, other fields also benefit from the use of laser scanners. In the agricultural automation industry, for example, there are a variety of researches in the assessment of canopy volume [

29], poplar biomass [

30] and trunks [

31], crop and weed distinction [

32], among other uses. On a different view, the robotics competition RoboCup and its educational counterpart RoboCupJunior, specifically on the Rescue [

33] and Rescue B [

34] categories, respectivelly, have also gained from using laser range data for robot navigation in unstructured environments to perform rescue operations.

Thus, there is extensive literature on 2D LiDAR data applications in detecting, locating and matching objects, as well as in map construction, matching and correction for self-localization. Yet, to the best of our knowledge, there is no clear universal consensus on strict mathematical notation and modeling for such instruments, although they present less computing cost than image recognition processes [

16]. The work [

35] also states that there is a standardization need for information extraction based on LiDAR data. They propose a framework from semantic segmentation to geometric information extraction and digital modeling, but their focus is on extraction of geometric information of roads.

In order to process laser scan information, each paper in the literature suggests its own notation, framework, and approach. This is far from ideal in scientific research and development, as well as in education, where a unified approach would be preferable. Considering all aforementioned applications, we claim that it is valuable and significant to propose and evaluate a formal mathematical definition for object detection and identification in tasks based on segmentation, tracking and feature extraction.

Given the wide array of applications based on and benefiting from LiDAR data, there is yet no rigid definition or analytical approach for the general problem of detecting objects in semi-structured environments. In other words, despite the existence of similar structures, there is a gap between different approaches.

1.1. Related Works

The flexibility and relative low cost of laser-based distance measurement instruments has promoted fast development in the field of robotics, specially for autonomous vehicles. The generality level and ability to detect and identify objects, obstacles, other robots and humans in a scene is deeply impactful in any autonomous robot’s planning algorithm. In the literature, distance laser data has been often modeled and processed in polar coordinates [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47], in order extract features from a given setting and parse data. Feature extraction itself on LiDAR data often relies in Polar Scan Matching (PSM) [

36,

37], Suport Vector Machines (SVMs) [

38], Gaussian Process (GP) regression [

39], various means of clustering and matching [

40,

41,

42,

43], among other probabilistic and deterministic approaches [

44,

45,

46,

47] to model and interpret data.

Robot navigation relies on sensor influx and fusion in order to extract environment features and deliberate upon its surroundings in order to execute a task, whether simple or complex. In that sense, LiDAR sensors are widely used in SLAM and often depend on feature mapping and tracking to achieve precision and accuracy using deterministic and probabilistic models, as seen in literature [

4,

6,

24,

25] and similar techniques are used in the research of autonomous driving [

7,

8].

Likewise, in applied and field autonomous robotics the need to detect, identify and match objects and their properties is imperative for task completion, and their mathematical interpretation can be fruitful to describe as well as improve models and implementations, e.g. in the field of forest and agriculture robotics applications [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Thus, formal investigations and modeling of the physical world for autonomous interpretation by robots is impactful.

1.2. Aims and Contributions

In such a context, a formal mathematical definition for object detection and identification in tasks based on segmentation, tracking and feature extraction is valuable for several applications within research and industry. Thus, our main contribution lies in formally defining laser sensor measurements and their representation, the identification of objects, their main properties and their location in a scene, representing each object by its mathematical notation within the set of objects that composes the whole Universe set, the latter being the complete environment surrounding an agent.

In summary, this paper deals with the problem of formalizing distance measurement and object detection with laser sweep sensors (2D LiDARs), defining strictly an object and some of its properties, applying such an approach and discussing its results and applications, regarding framework setting for object detection, localization and matching. To address these topics, related formalization efforts and similar works that may benefit from a modeling framework are presented. Thereupon, our contribution is laid out on three main sections of theoretical modeling and subsequent experiment with a real robot. First, we define the scope and how to represent LiDAR scan measurements mathematically. Then, this framework is used to define and infer properties from objects in a scene. Finally, a guideline for object detection and localization is set with an application, providing insight by applying these techniques in a realistic semi-structured environment, thus validating our proposal and investigating the advantages for modeling and applications. Our goal is to enable comprehensible, common-based research of the advantages and possible shortcomings of LiDAR sensors in the various fields of robotics albeit educational, theoretical or applied.

2. Proposed Formalism for Object Identification and Localization

In robotics applications, a navigation environment is categorized based on the quantity and disposition of objects in the scene, as well as the agents’ freedom of movement. In this context, an environment is known as structured when the task-executing agent is previously familiar with the posture of any object and those do not suffer any changes (or all changes are known) during task execution. In contrast, when objects move unpredictably as the agent is executing tasks, the environment is said to be unstructured. Finally, those environments in which a certain degree of object mobility is admissible, such as offices, laboratories, residences, storage houses and workshops, are known as semi-structured environments.

In the specific case of semi-structured environments, entities in the navigation scene may be mapped by an agent using a distance sensor, which this work will consider to be a laser scanner sensor as a 2D LiDAR. These entities may be fixed objects (as walls, shelves, wardrobes, etc.) or mobile objects (e.g. boxes or even other agents).

2.1. 2D LiDAR sweep representation

A 2D LiDAR uses a LASER beam to measure distances from itself to objects in a plane surrounding the sensor. In mobile robotics applications, usually, the LASER beam rotates parallel to the ground so that the resulting measurements give the robot information about its distance to obstacles around it. Different sensors have varying ranges and resolutions, which must also be taken into account. In the definitions to follow, the subscript k denotes a discrete set of elements and n represents an element belonging to such a set, thus both being discrete.

Definition 1.

Let r be a discrete function representing a LiDAR sensor, denoted by

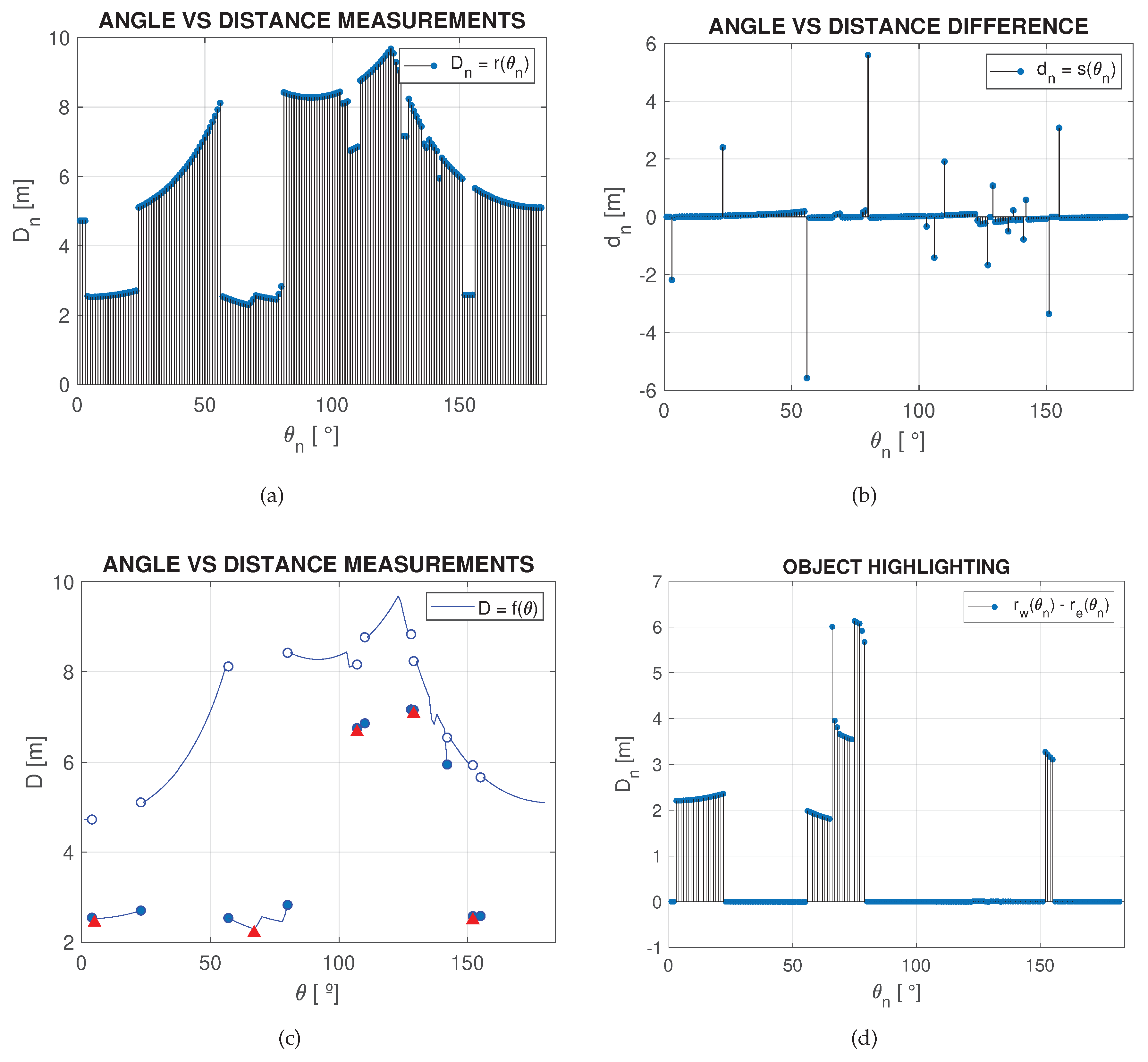

where the domain indicates a set containing each discrete angle within the angular scan range and the codomain the set of measurements assigned to each angle . Such a discrete function is shown in Figure 1(a).

Definition 2.

Let s be a difference function given by:

where analogously to Definition 1, is an element in the set of all angles within the instrument’s angular range and a set of differences between two neighboring consecutive measurements, as shown in Figure 1(b).

Definition 3.

Let f be a function coinciding with r() , that is:

such that f is also continuous and monotonic in intervals for every , whose one-sided limits are:

whenever , where ) is the set cardinality of (the sensor’s resolution) and is a case-specific threshold value (free parameter) representing the difference of the minimal distance measurement for object detection. In order to automate the process of object detection and identification, a measure for may be calculated as the mean absolute difference value:

in order to separate noise from actual meaningful data, as it will be further addressed. An example is presented within a simulated environment in Section 3 ( Figure 4).

Proposition 1. Given a well-functioning LiDAR sensor, .

Proof. The LiDAR sensor attributes a distance measurement reading for each angle within its range, unless the sensor malfunctions or has manufacturing errors, which must then be assessed and corrected. □

Corollary 1. Given Proposition 1 is satisfied, is surjective by definition.

Corollary 2. Proposition 1 and Corollary 1 implicate that is surjective by definition, since coincides with .

Above, Definition 1 states how the agent visualizes its navigation surroundings. Notice that it follows from Corollary 2 and Definition 3 that is differentiable over most of its domain. Those points where is not differentiable have important properties, to be discussed when defining objects in a laser’s scan data. Note that and , their extreme values are specific to model and manufacturer of the sensor device.

2.2. Defining objects

First we define to be a set of points representing the whole environment in the robot’s point of view composed respectively by a set of objects, a set of agents (either humans or robots in the environment) and other task-unrelated data, taken as noise. Evidently, these three sets of data comprising are disjoint sets among each other.

Definition 4.

Let be a universe set, populated by LiDAR measurements and comprised strictly of a set of objects , a set of agents and a set of noise . Thus:

Now, as f is a continuous function, it may or may not be differentiable. However if f is differentiable in a, then f is continuous in a and it is laterally continuous: . In other words, the left-hand and right-hand derivatives in a must exist and have equal value. By applying the concept of differentiability, objects, walls and free space can be distinguished in a LiDAR scanner reading. In particular, it follows that if there exists a point where is not differentiable and that point does not belong to the interval of an object, then that must be an edge of a wall (corner), otherwise that point belongs to the edge of an object.

Definition 5.

Let be any prism-shaped object in a semi-structured environment. Then may be defined as a set of points in polar coordinates:

where , such that is a point of discontinuity and is the first next point of discontinuity to the right-hand side of , thus both encompassing start and final measurements of an objects’ body. Thus, is continuous in the open interval

Consider a generic prismatic object and its respective polar coordinates comprised in

. Notice that, in any such set

, a discontinuity in the derivative of

must represent an edge, indicated with red triangles in

Figure 1(c). Therefore, we can define both faces and vertices that belong to

O.

Definition 6.

Let be a set of points representing any edge of any prismatic object, such that:

Definition 7.

Let be any prism-shaped object, then let be a set of points representing the k-th face of such an object. Therefore, we define in polar coordinates:

where , and all are in .

In other words, according to Definition 7, any of the prism’s edges are found in a local minimum or maximum between two faces according to the laser’s readings and all faces are found within , such that .

Therefore, as in

Figure 1(c), the function

is discontinuous in

and

. From that, it is possible to define that every element

represents a measurement from the surface of an object (hereby defining all necessary conditions for proposing the existence of an object). Note that

O was defined as prism-shaped for the sake of defining faces and vertices, although the same discontinuity-based definition may be used to identify other - more unusually-shaped - objects.

The above proposal could improve formalism, notation and analysis in [

22] without great computational effort. Similarly, [

2] could benefit from notation formalism in point cloud temporal series as a means of data representation as a function of time and reference frame. In yet another case-oriented illustration, [

5] presents a scenario where laser data are presented on the Cartesian plane for later use in extrinsic camera parameter calibration. Its worth reinforcing that our work could have been employed in all such cited situations as a guideline for laser sweep representation, region of interest highlighting in data and notation, in order to develop the state of the art in autonomous robot navigation. For further illustration and validation of the strategy’s reliability, generic representative cases will be presented in the following section.

3. Detection and Localization Experiments

This section demonstrates the behavior of the 2D LiDAR sensor in a real-world environment, and how the formalism proposed in this article is used to represent the scene and to identify potential objects of interest.

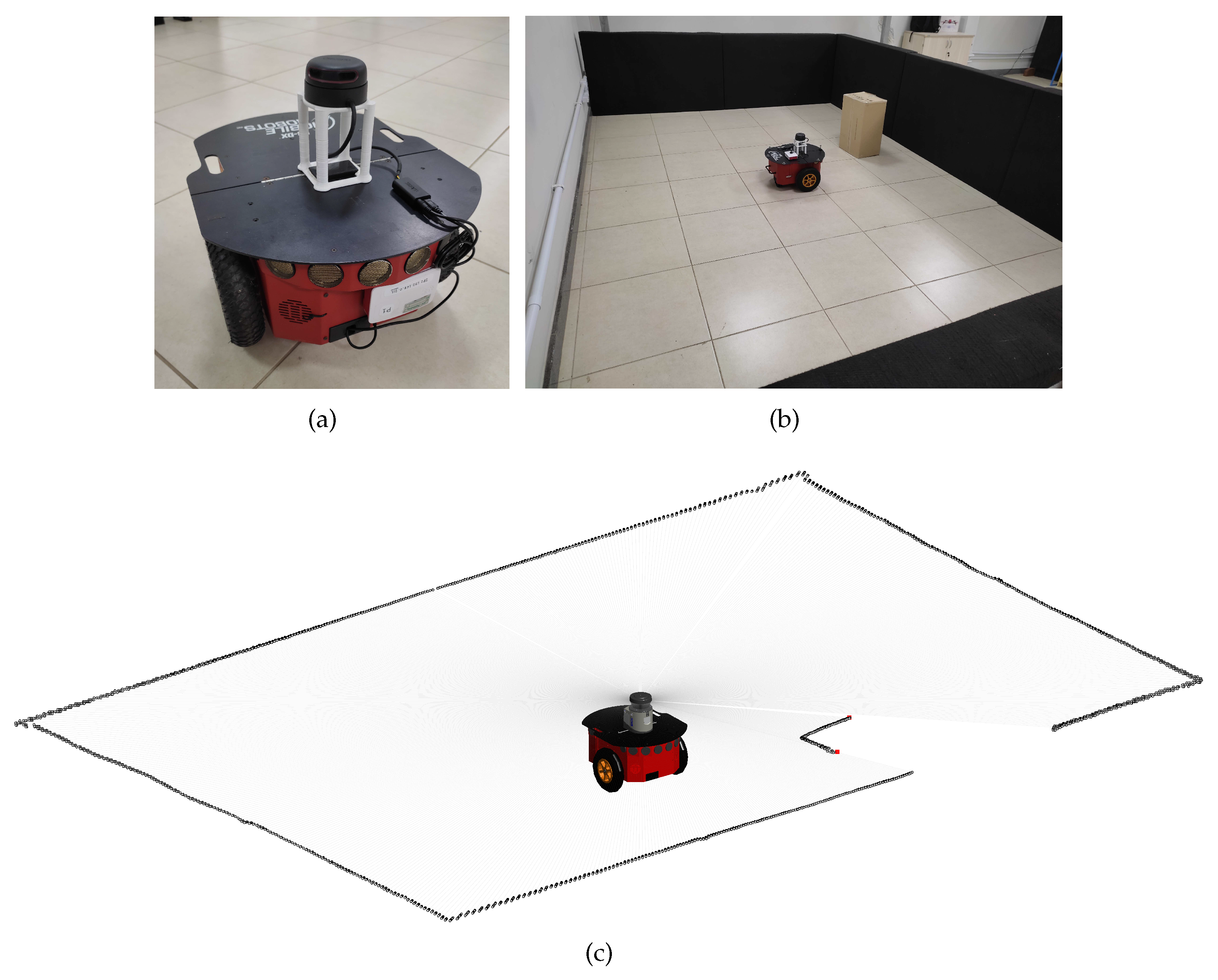

Figure 2 shows a basic experimental setup to illustrate the materials and LiDAR measurements. The robot used in the experiments is shown in

Figure 2(a): a Pioneer 3-DX controlled by a Rapsberry Pi running RosAria, with an omnidirectional 2D LiDAR sensor mounted on its top. A basic setup with the robot and one static object (a box) is shown in

Figure 2(b). The corresponding LiDAR measurements are shown in

Figure 2(c), where the edges of the object are identified (red dots).

To further illustrate the usefulness of our proposal, we use a scenario with objects of diverse configurations, sizes, and shapes, to build an environment that faithfully represents a real world use-case. In such a scenario, the mobile robot navigates along a super-ellipse trajectory around the objects located in the center of the environment. Measurements from the 2D LiDAR sensor are used to build views of the scene while the robot is navigating. The LiDAR sensor is configured with a depth range of 0.1 to 12 meters, a resolution of 361 measurements per revolution, and a sampling rate of one revolution per 100ms. Following our notation, the laser’s domain is

, such that

(k=

), and the codomain is

m, as per Definition 3. To guide the navigation of the Pioneer 3-DX, a previously validated controller was employed [

48].

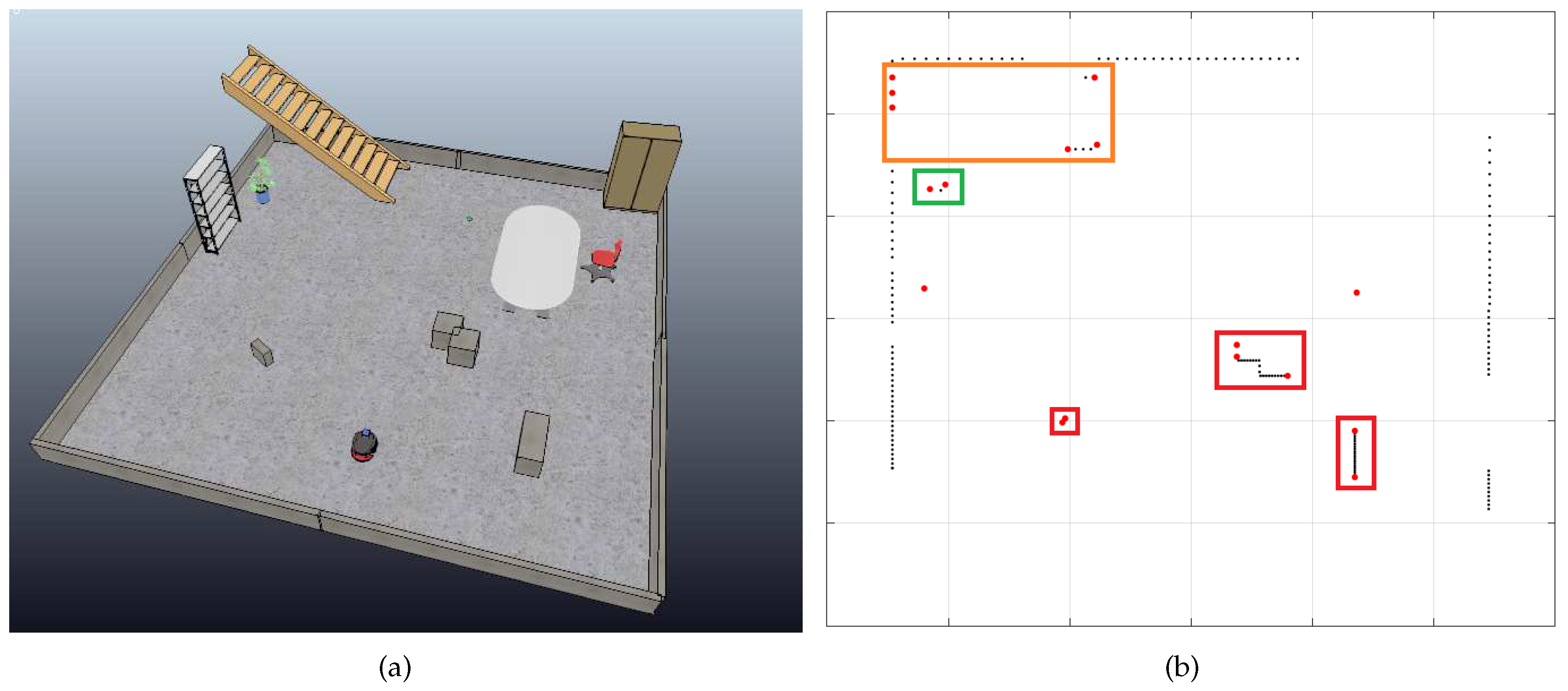

Figure 3 illustrates the experimental environment used to validate the sensory mathematical representation. In the displayed views, it is possible to verify the presence of rectangular boxes, chairs with legs and wheels, a four-legged ladder, a second mobile robot, and the walls that bound the scenario. This configuration enabled the identification of objects based on the discontinuities observed in the measurements, as conceptualized in

Section 2.

Figure 3.

Experimental environment employed for validating the sensory mathematical representation. Figures 3(a) and 3(b) are views of the same scenario in different conditions and angles. Figures 3(c) and 3(d) are the 2D LiDAR readings corresponding to the scenes (a) and (b), respectively.

Figure 3.

Experimental environment employed for validating the sensory mathematical representation. Figures 3(a) and 3(b) are views of the same scenario in different conditions and angles. Figures 3(c) and 3(d) are the 2D LiDAR readings corresponding to the scenes (a) and (b), respectively.

To confirm the validation of the proposed approach, utilizing Definition 3,

establishes, computes, and distinguishes the objects in the scene. In

Figure 4, all red lines represent a set of measurements of interest, indicative of a potential object. It is important to emphasize that the vertices of the objects, i.e., their starting and ending boundaries, are derived from the difference function

.

To illustrate the identification of objects during the robot’s navigation, the first row of

Figure 5 presents three snapshots of the robot’s trajectory. The second row of

Figure 5 shows the corresponding 2D LiDAR scans, while the third row of the same figure presents the 2D reconstruction of the world from the perspective of the mobile robot (with the blue bounding boxes representing the identified objects). A video

1 shows the execution of this experiment.

Figure 4.

Resulting selection from

Figure 3 based on

, according to Definition 3.

Figure 4.

Resulting selection from

Figure 3 based on

, according to Definition 3.

Figure 5.

Snapshots of the validation experiment with their corresponding 2D LiDAR readings from the robot’s perspective, along with the 2D representations in the world featuring bounding boxes of identified objects according to the proposed formalism.

Figure 5.

Snapshots of the validation experiment with their corresponding 2D LiDAR readings from the robot’s perspective, along with the 2D representations in the world featuring bounding boxes of identified objects according to the proposed formalism.

It is important to note that in real-world experiments, we commonly encounter sensor noise and information losses, which are appropriately addressed through signal filtering processes. However, since this is out of the scope of this work, we chose to showcase the step-by-step implementation of the object identification process in the absence of sensor noise via a simulation.

Figure 6 depicts a cluttered environment created using the CoppeliaSim simulator.

Figure 6(a) illustrates the simulated scenario, and

Figure 6(b) shows the corresponding 2D LiDAR data, where the process described before was applied to detect, identify, and categorize objects.

Figure 6(c) presents a LiDAR sweep (r

, as previously defined), allowing intuitive differentiation of the highest values as walls and lower readings as objects, depending on their proximity to the robot. Upon careful analysis and comparison of

Figures 6(d) and 6(e), as discussed and defined in

Section 2.2, various objects are identified by setting a similar threshold difference value (as presented in Definition 3) in

and observing discontinuities in

. Discontinuities occurring for an angle measurement where the threshold is surpassed must represent the starting point of an object. Furthermore, local minima in each set representing an object must also represent the edge closest to the scanner, marked in Figure fig:envSim(e) with red triangles. The objects’ readings are shown between two dark-blue filled circles, comprising

and thus exhibiting five fully identified objects

and

.

Comparing

Figures 6(a) and 6(b), one can identify the objects marked in

Figure 6(e) (in anti-clockwise order): the first and second brown prismatic boxes, the wooden ladder, the potted plant, and the smaller brown box, as seen in

Figure 6(a). Respectively, they are separated with color-coded bounding boxes: red for the prismatic boxes, orange for the wooden ladder, and green for the plant, according to the topology of the

faces that connect each object’s edge (

represented as red circles). By observing the environment using the 2D LiDAR scan, the robot can identify objects of interest in the room and understand its distance to them.

Assuming the agent has a known starting point (e.g., a recharging dock) or a map linking each laser sweep to a certain position, it is also possible to locate objects by storing measurements of the semi-structured environment without any objects of interest to the robot—no objects that should be handled by the agent, only uninteresting objects. Then, one can highlight any new objects by taking the algebraic difference between readings before and after objects were placed—where

represents measurements with the new objects, and

represents the original readings of the environment. This is shown in

Figure 6(f), where every new

and

are outlined, thus locating all

objects of interest in the environment, while all other data is considered noise. Given these features, it is possible to match and track specific objects throughout a scene. For instance, the three brown boxes are highlighted as an example of objects of interest.

4. Concluding Remarks

Addressing a crucial aspect of autonomous robot decision-making, the identification and localization of objects, especially those essential for achieving specific goals, play a pivotal role in advancing robotics. The lack of a formal and standardized framework in existing literature has posed challenges for algorithm comparison, optimization, and strategy development. This deficiency arises from the prevalent use of ad-hoc definitions and modeling approaches, hindering the reproducibility and advancement of results.

Our work fills this gap by introducing a rigorous mathematical formalization applicable to a broad range of contexts involving LiDAR point-cloud data. Results presented in

Section 3 show that our method is able to efficiently identify and separate objects in under 50ms in semi-structured environments. Despite the necessity of setting a threshold for object detection, which may not be automatically or dynamically determined, our approach allows flexibility to tailor this parameter to the specific requirements of each application. The simplicity of our mathematical framework ensures low computational effort and efficiency, laying the foundation for creative solutions in diverse scenarios.

In conclusion, our manuscript establishes a comprehensive framework for the development and optimization of algorithms focused on autonomous object detection, localization, and matching using 2D LiDAR data. We provide essential insights into the properties of laser scanner data and offer guidelines for feature extraction, with potential applications ranging from direct implementation for specific tasks to indirect applications in machine learning processes. Overall, we anticipate that our analytical structure will inspire the development of coherent and effective methodologies for object detection, identification, and localization in various applications.