Introduction

Given the increasing demand for external accountability and public transparency, rankings have been widely adopted in higher education (Luque-Martínez and Faraoni, 2020; Elken et al., 2016). The need for accountability and responsible behaviour is stressed through greater emphasis on output controls (Marginson and van der Wende, 2007; Hezelkorn, 2011; Tandilashvili, 2016). To meet these demands, numerous national and international actors have been involved in developing different types of rankings.

Evaluating the performance of higher education institutions (HEIs) includes assessing the quality of teaching and research activities, and as “quality” is a highly subjective and debatable concept (Tandilashvili et al., 2023), university rankings have become a major topic of discussion. On the one hand, the rankings are presented as a relatively objective means of judging the quality of universities. They are also acclaimed to improve transparency and allow students to make informed choices. However, critics have questioned their objectivity since their evaluation methods depend strongly on the choice of indicators used (Luque-Martínez and Faraoni, 2020; Kosztyán et al., 2019; Collins and Park, 2016; Tandilashvili and Tabatadze, 2016; Millot, 2015; Aquillo et al., 2008; Hendel and Stolz, 2008; Marginson and van der Wende, 2007). They also argue that rankings do not address some of the key functions of higher education and that the indicators applied measure distant proxies rather than quality itself (Bloch et al., 2021; Roessler and Catacutan, 2020; Collins and Park, 2016; Ter Bogt and Scapens, 2012; EUA report 2011; Marginson and van der Wende, 2007; Brooks, 2005).

In addition to serious criticism and even opposition from academia, rankings are nonetheless widely accepted by higher education players and the wider public due to their simplicity and consumer-oriented information (Tandilashvili, 2022; Luque-Martínez and Faraoni, 2020; Tandilashvili and Tabatadze, 2016; Wilkins and Huisman, 2015; Marginson and van der Wende, 2007). Consequently, university rankings have been subject to increased academic scrutiny and critical debate in recent years.

Previous studies have explored rankings’ impacts on different levels: on policy making (Lim and Williams Øerberg, 2017; Marginson and van der Wende 2007; Dill and Soo, 2005); on HEIs strategy and objectives (Collins and Park 2016; Elken et al., 2016; Hazelkorn, 2011; Hendel and Stolz, 2008; Maginson and Sawir, 2006; Dill and Soo, 2005) on students’ choices (Clarke, 2007); on departments and other sub units (Tandilashvili, 2022; Marques and Powell, 2020), on academics’ behaviour (Tandilashvili and Tandilashvili, 2022; Bloch et al., 2021); and on university identity (Tandilashvili, 2022; Roessler and Catacutan, 2020; Elken et al., 2016).

The aim of this paper is to contribute to the discussion on the effects of international university rankings on universities by exploring their impact of international rankings on the French universities on three levels: national, organisational, and individual. While much has been written about the methodologies employed, together with their inherent basis and problematic impact on higher education policies, detailed case studies on the actual effects of university rankings, especially in a national context, remain an important desideratum in the literature. Rare prior empirical studies have identified tensions and value conflict generated within the French universities at different levels (Tandilashvili, 2022).

Impact of international rankings, despite its global character, needs to be studied within a national context, as national systems, regularities and frameworks alter the institutional responses to this global trend. Indeed, as explained by Collins and Park (2016), international rankings must be examined in terms of their interaction with “domestic historically generated notions of reputation, and in particular the rigidity of national hierarchies and the importance of domestic rank for students, alumni and both public and private funding” (p.128). Earlier, Whitchurch and Grodon (2010) emphasised that academic and professional identities were turning more dynamic and multi-faceted around the world, however the changes occurred at different rates in different contexts.

The article thus addresses an empirical gap with a study of three French universities. Very few empirical and theoretical studies have addressed the impact and outcomes of international university rankings on French universities. However, since the appearance of the best-known rankings in the 2000s, the French government has introduced several measures in order to meet the ranking evaluation criteria (Eloire, 2010). On the other hand, like their foreign counterparts, French universities have engaged in important actions aiming at improving their position in global rankings (Lussault, 2010; Naszalyi 2010).

Generalisable findings of this article contribute to the scientific literature on understanding how evaluation instruments, such as international rankings affect organizations and individuals in the higher education sector. It offers insights into the academics’ perception of the experienced changes and contributes to current debate of evolution of academic profession. The findings can be interesting for policymakers and university managers by examining current trends and fostering discussion on educational policy settings.

Literature Review

International university rankings reflect judgmental assessments (Ter Bogt and Scapens, 2012) as they seek to evaluate universities in a quantitative way by comparing them with other universities. One of the first international university rankings, the Shanghai ranking, was published in 2003 and was quickly followed by other, large-scale, indicator-based assessments of universities that were published either as a ranking (individual institutions ranked according to certain criteria) or as a rating (individual institutions assessed according to certain criteria). Although the rankings have been modified since they first appeared in a bid to improve their subjective methodology (Tandilashvili and Tabatadze, 2016; Marginson, 2007), they are still criticized for lacking sufficient theoretical clarity and methodological precision (Roessler and Catacutan, 2020; Collins and Park, 2016; Marginson, 2013; Hendel and Stolz, 2008). Academics appear to agree that most international rankings “have fallen short of their larger goal of measuring quality” (Brooks, 2005: 4) and that there is a “mismatch between the quality, reputation and ranking” (Collins and Park, 2016: 115).

Main criticisms of international rankings

One of the main criticisms concerns the attempt to quantify the quality of university performance. Scholars argue that higher education missions are so complex that it is impossible to measure them by simple quantitative indicators (Tandilashvili and Tabatadze, 2016; Collins and Park, 2016; Millot, 2015; Hazelkorn, 2011; Vinokur, 2008,). Some examples of quantitative indicators are the number of publications in ranked journals, number of students, internationalisation degree and number of Nobel prizes. Scholars regret that this search for objectivity gives the impression that the value of education can simply be counted, hierarchically ordered, and uncontrovertibly judged (Tandilashvili and Tandilashvili, 2022; Ter Bogt and Scapens, 2012).

Another major criticism is that international university rankings reflect research performance far more accurately than teaching (Tagliaventi et al., 2020; Tandilashvili and Tabatadze, 2016; Millot, 2015; Hazelkorn, 2011, 2013; Aquillo et al., 2008). As rankings neglect missions other than research, they do not evaluate all universities under the same conditions (Roessler and Catacutan, 2020; Ter Bogt and Scapens, 2012; Marginson and van der Wende, 2007; Harfi and Mathieu, 2006; Brooks, 2005). For instance, the Shanghai ranking measures education quality by the number of Nobel prizewinners among university graduates, which may be considered as linked to the quality of education, but in a very specific and somewhat indirect way (Tandilashvili and Tabatadze, 2016). At the other extreme, some rankings judge teaching quality using staff/student ratios alone, without examining the teaching/learning relationship itself (Tandilashvili and Tabatadze, 2016). In a recent study Tagliaventi et al. (2020) argued that putting the research to the centre stage impacted the public service mission of academics.

One further argument against the rankings methodology is that measuring the quality of research in all disciplines using similar bibliometric indicators is also questionable due to wide differences in research traditions between the social and natural sciences (Tandilashvili, 2022; EUA report, 2011). Adopting bibliometric indicators to measure research quality is more adapted to exact and medical sciences than to human and social sciences. Traditionally, there are more publications and more citations per publication in natural sciences, while social sciences tend to publish books rather than papers.

There is also an issue with language. It has been noted that international rankings tend to favour universities from English-language nations as non-English language work is both published and cited less frequently (Collins and Park, 2016; Marginson and van der Wende, 2007; Marginson, 2007). A study by the Leiden Ranking team showed that the citation impact of publications from French and German universities in French or German, respectively, was smaller than the citation impact of publications from the same universities published in English (van Raan, et. al., 2010).

In addition to seminal work on the failings of rankings’ methodology, international rankings have also been considered as harmful to the academic profession and to university identity (Bloch et al., 2021; Tagliaventi et al., 2020; Elken et al., 2016; Tandilashvili, 2016; Naszályi, 2010; Eloire, 2010; Harfi and Mathieu, 2006; Vinokur, 2008). For example, Elken et al. (2016) argue that as rankings are not value free, they may have impact on university identity as they emphasize some aspects of university activities at the expense of others (Dill and Soo, 2005). Wilkins and Huisman (2015) have observed downsides and negative effects of rankings on the academic profession.

Studies mainly deplore two aspects. First, the neoliberal ideology of rankings is viewed as a threat to the traditional philosophy of education. For example, rankings are claimed to go against the democratic vision of higher education as they impose a normative view of what is a “good university” (Tandilashvili, 2016; Eloire, 2010). Others consider that rankings neglect the public service mission of universities (Roessler and Catacutan, 2020; Tagliaventi et al., 2020). And as rankings overlook the diversity and complexity of HEIs’ missions (Roessler and Catacutan, 2020), they alter HEIs identity altered (Vinokur, 2008). Yet others regret that rankings artificially create markets for universities and introduce market-like forces which contribute to establishment and maintenance of academic capitalism (Cantwell, 2015).

The second major concern is that international rankings will suppress national specificities (Millot, 2015; Eloire, 2010; Chapuisat and Laurent, 2008; Marginson and van der Wende, 2007; Harfi and Mathieu, 2006). Some consider that it is not possible to compare all national systems with the same tools as they differ considerably (Kosztyán et al., 2019). Eloire (2010) argusd that rankings serve as a “powerful tool for universities to imitate the world model of what is a good university: a model often copied from Anglo-Saxon countries” (Eloire, 2010: 35). Chapuisat and Laurent question whether imitating Anglo-Saxon universities is useful for French universities as they operate in radically different contexts (Chapuisat and Laurent, 2008).

French response to international rankings

Many agree that the “disappointing image” of French universities, pushed the French government to undertake certain reforms in order to improve the country’s overall positioning in international rankings (Tandilashvili, 2022; Tandilashvili, 2016; Harfi and Mathieu, 2006). In one of her press interviews in 2008, the Minister of Higher Education and Research, Valérie Pécresse, declared that the “bad grades” in international rankings reveal the urgency to reform the French university system (Echos, 2008). In another interview, she stated that the aim of her major reforms was to “see ten French universities in the top hundred universities in the Shanghai ranking (Le Figaro (Pécresse veut dix universités dans l’élite Mondiale”, 6 August 2008. Interview with Valérie Pécresse, Minister of Higher Education and Research.)). This reform, called the law of university autonomy (LRU), was introduced as an answer to the poor positioning of universities by helping them to “define their scientific priorities”. In his speech at the National Council of the UMP political party, then president of the republic, Nicolas Sarkozy, declared that thanks to some reform, French universities had progressed in the Shanghai rankings for the first time ever (speech of Nicolas Sarkozy, 2009).

Tandilashvili (2022) gave examples of other reforms directly aimed at improving the position of “some” French universities in certain world rankings, such as the creation of the National Agency of Research (ANR), the creation of the Research and Higher Education Evaluation Agency (AERES), the introduction of Research and Higher Education centres (PRES), and increasing universities’ organisational autonomy by way of the LRU law. The main idea behind all these reforms was to introduce economies of scale by grouping major research and education institutions to give them more international visibility.

Like their counterparts, French academics have strongly criticized the ranking methodologies, questioning their capacity to objectively judge university performance (Lussault, 2010; Naszalyi 2010). One concern that nearly every study in France has raised is the fear that implementation of these public policies, in addition to the more direct impact of global rankings on French universities, could alter their traditional way of functioning (Chapuisat and Laurent, 2008; Eloire, 2010). Studies of different national contexts (Australia, UK) have demonstrated that changes at public policy level provoke changes in organisational and professional settings in academia (Lim and Williams Oerberg, 2017; Parker and Jary, 1995). Indeed, French studies have also put forward certain actions initiated by French universities and academics which could have been influenced by international rankings (Tandilashvili, 2016; Drucker-Godard et al., 2013; Hetzel, 2010; Chapuisat and Laurent, 2008).

The literature on changes in higher education institutions due to the introduction of international rankings paves the way to an examination of whether similar changes have occurred in the French context. In a context of very little empirical research investigating the real impact of this phenomenon on French universities, we adopt the model of Parker and Jary (1995) to illustrate the results of a detailed case study on the effects of world rankings on three French universities. A study realised by Jary and Parker in 1995 suggested a three-layer model to investigate changes in the field of higher education. The model was influenced by earlier work of Clark (1983) and Becher and Kogan (1992), and further developed by the authors in order to examine major changes in the UK’s higher education system in the 1990s. The authors argued that changes in the political and institutional context (change at national or structural level) lead to forms of corporate work organisation (organisational level changes) that increase the power of management and decrease the autonomy and motivation of academics (changes at the level of individual or action) (Parker and Jary, 1995).

Research Methodology and Data Analysis

The choice of a qualitative approach was determined by the exploratory nature of our research as well as the complexity of the study context. Our research question – what is the impact of international rankings on French universities? – involves analysing the cause-effect relationship at two levels: i.e., understanding the experiences of universities as organisations and the experience of the faculty as a profession. A multiple case study (Yin, 2003) was used to analyse the changes perceived by academics from different universities.

Three French universities served as case studies for our research. The choice of institutions was based on multiple criteria. First, we selected universities specialising in various disciplinary fields (i.e., science, social science, and a multidiscipline university) to compare the impact of rankings on different disciplines. Another criterion as to choose universities with different positions in the international rankings. To retain the interviewees’ anonymity, we renamed the three universities as University A (UA), University B (UB) and University C (UC).

UA is one of the biggest science universities in France. It describes itself as the research university that embodies “French scientific excellence”, and it is well positioned in international rankings (top 50). UB is a French multidisciplinary university that is famous for innovation and internalization. It has a relatively good position in nearly all the international rankings (50-100). UC is a very big French university, famous for human and social sciences and for its large campus. It does not appear at all in many international rankings, or has a very poor position.

The main source of the empirical data comes from semi-structured individual interviews with the faculty. As our unit of observation is limited to representatives from three universities, we tried to maximize the variety of respondents. We selected three main criteria for our sample selection: experience, disciplinary field, and function at the university. Most respondents occupy senior management positions (president, vice president) and middle management positions (deans, head of administrative departments). Only four of the interviewees were academic staff with no administrative or hierarchical responsibilities. In the French higher education system, a university president, vice president and dean are necessarily academics. The seven heads of major administrative departments interviewed in the study do not hold any academic degree but have management education and experience. All 25 semi-structured interviews were recorded and fully transcribed.

Table 1.

Interview respondents.

Table 1.

Interview respondents.

| Position |

UA |

UB |

UC |

Total |

| University president |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

| Vice president |

1 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

| Dean |

3 |

4 |

1 |

8 |

| Chief administrator |

2 |

3 |

1 |

6 |

| Academics |

1 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

| Total |

8 |

12 |

5 |

25 |

In addition to the interviews, our empirical data included 30 internal and external documents, namely, the universities’ annual reports, budgets, internal regulations, online publications, and university brochures. We also attended some meetings at the three universities where we took notes. We used these documents as a secondary data source that gave us insights into the context. Last, we analysed major legislative texts pertaining to higher education and enacted in France since the 2000s to help us identify links between public policies and international rankings.

The empirical data was analysed by thematic analysis. We translated the data into grounded theory by applying naturalistic inquiry processes (Lincoln and Guba, 1985), including constant comparison and theoretical sampling (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). Our initial approach was a first-order analysis (Van Maanen, 1979) involving full coding of the interview transcription and documentation. Reading of the first material enabled us to develop initial thematic codes which were completed during in vivo coding (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) using the NVivo software. This first-order coding identified the following key topics related to ranking: evaluation, pressure, publication, competition, public reforms, discipline specificities, communication, university missions, academic profession, university strategy and objectives, and university contracts.

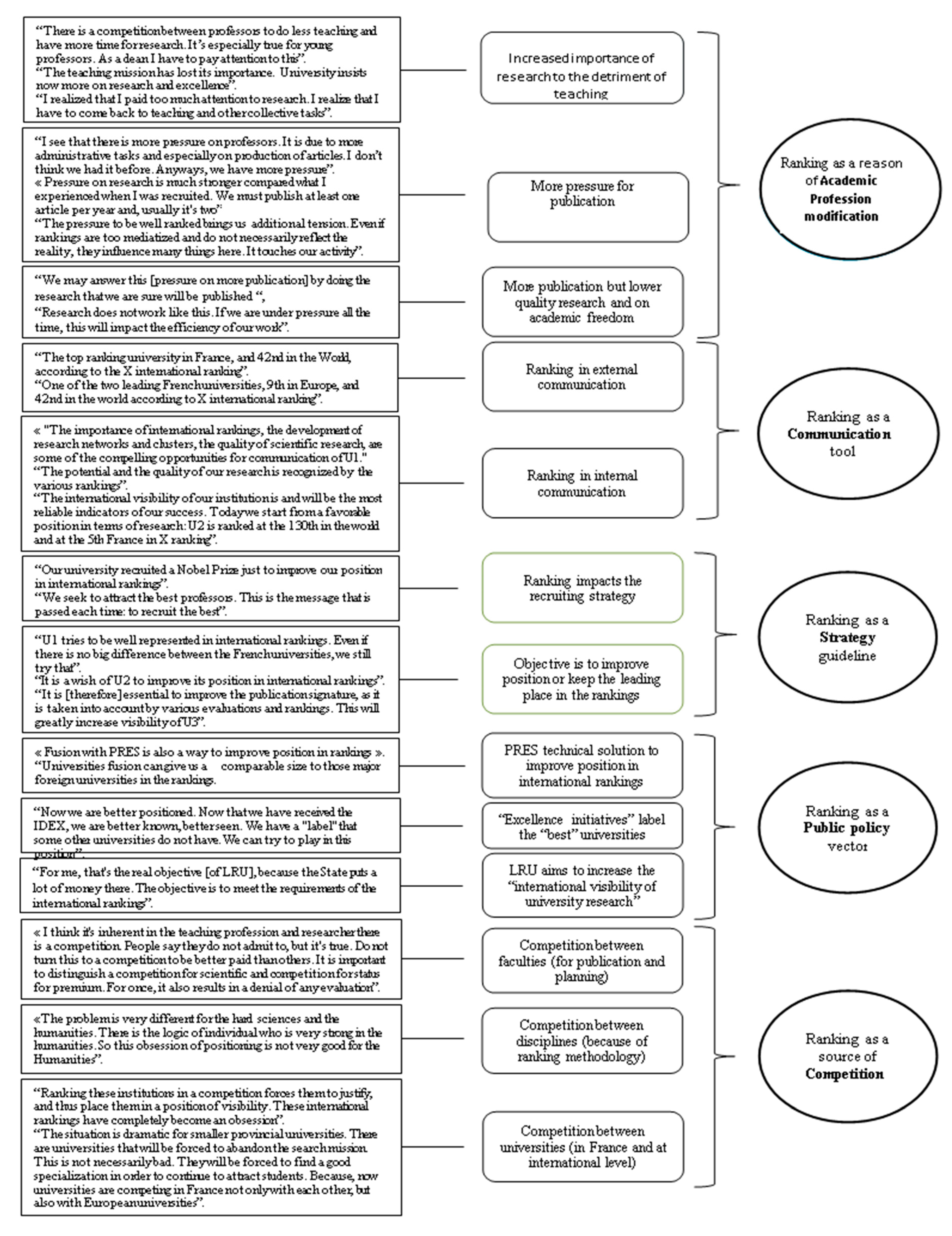

These empirical concepts were grouped according to their significance (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Our themes were predominately descriptive, i.e., they described patterns in the data relevant to the possible impact of international rankings on university management. At this stage of the analysis, we identified the ‘essence’ of each theme and a causal relationship between them (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Five main dimensions emerged:

Ranking as a reason of academic profession modification; Ranking as a university communication tool; Ranking as a strategy guideline for universities; Ranking as a public policy vector; and

Ranking as a source of competition. The

Figure 2 illustrates these codes.

Main Findings

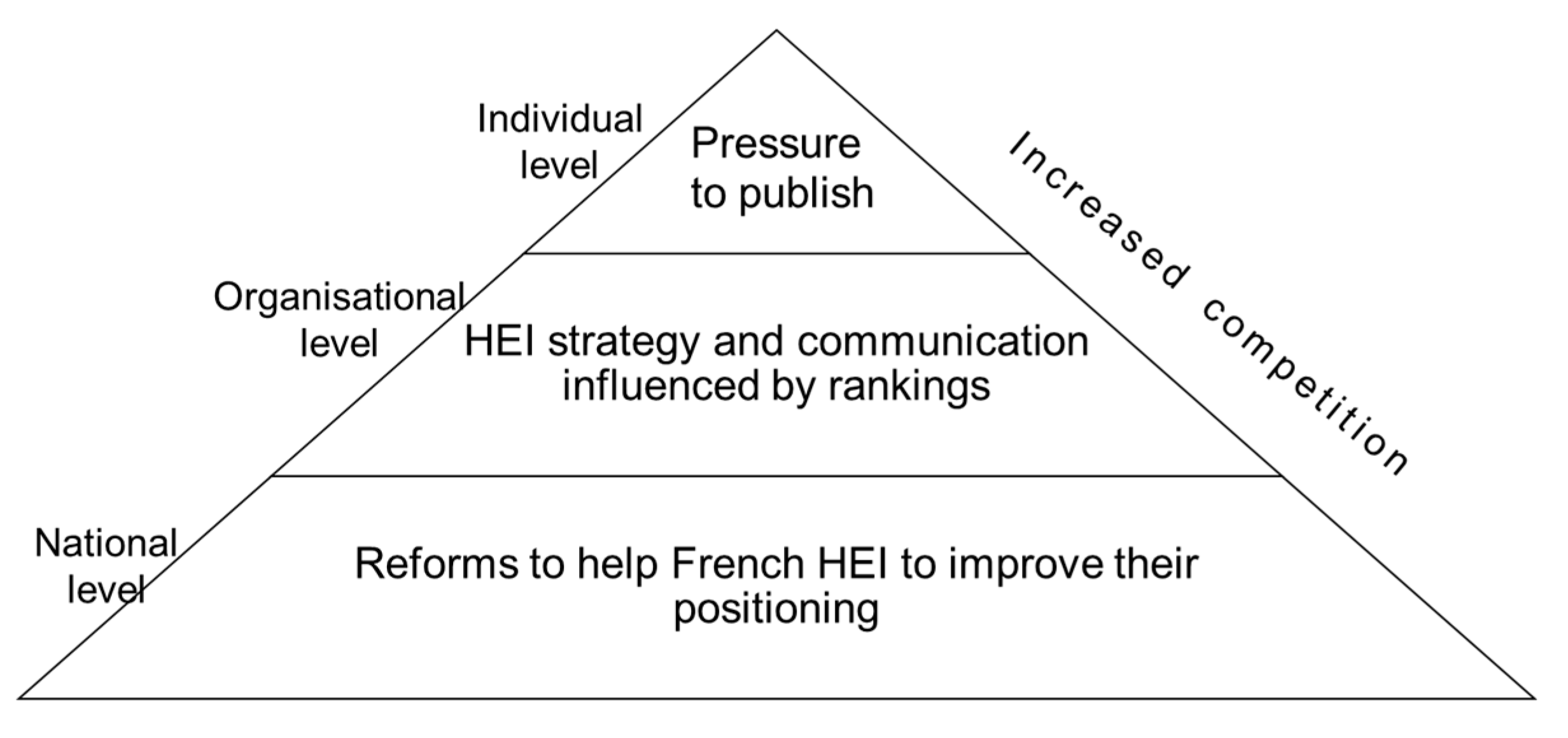

Data analysis demonstrated that the introduction of international rankings has impacted French higher education on three levels: national – various public policies have been influenced by international rankings; organizational – a number of management decisions have been made to address the rankings’ requirements; and individual – rankings change the way academics perceive and exercise their profession.

Figure 1 summarizes the main impacts. The following sections detail these findings.

Figure 1.

Impact of international rankings at different level of French higher education.

Figure 1.

Impact of international rankings at different level of French higher education.

Impact of Rankings on Academic Profession

An analysis of twenty-five individual interviews showed that the rankings have impacted the academic profession in a number of ways. First, the importance given to research in ranking methodologies has altered the balance between traditional teaching and research. As research is highly valued in international rankings (as well as in national and local evaluations), French faculty pay considerable attention to this aspect. Most of the respondents are conscious of the growing emphasis on journal ranking and focus more on what journal editors and reviewers are likely to accept for publication than what matters for the well-being of the profession and society (UA_18_AC).

This tendency is not specific to France. The study by Ter Bogt and Scapens (2012), for example, demonstrated that activities which are not included in the quantitative performance measurement system are largely neglected. Academics have adapted to the new system and concentrate on “satisfying” the underlying requirements. “They focus on research and ensure that their teaching performance is at least satisfactory” (Ter Bogt and Scapens, 2012: 477). A recent Australian study showed that universities act strategically in how they seek to both influence and respond to annual ranking releases, especially when it comes to their research activity (Dowsett, 2020). Changes are made to contribute to a significant rise in their ranking. White et al. (2012) point out that academics who achieve extremely high research output are those who, alongside personal interest in research activity, have more time to conduct research thanks to a reduced teaching workload and administrative support from their institutions. A study by Tagliaventi e al. (2020) showed similarly that some academics tend to adopt more research orientation compared to other missions.

Our analysis also confirms the importance of research by the budget distribution of the universities studied. As one research centre director explained, their budget was not cut, which was an exception as the university’s overall budget and the budget of nearly all other activities was reduced significantly.

Another impact of rankings on academics is that the importance of research has put additional pressure on the faculty to publish more, especially in “Impact Factor” journals. For the interviewees, this does not necessarily mean doing better research. The pressure is only on the number of publications, resulting in increased tension between colleagues. Some examples of the interviewee discourse can be found in

Figure 2 below. Previous research has also noted increased tension among faculty members, with extensive competition observed in the traditional profession due to conflict between long-established and newly emerging missions (Tandilashvili, 2016). The emphasis on research to the detriment of teaching inevitably impacts teaching quality. Our finding is in line with a study by Drucker-Godard et al. (2013) that also demonstrated a “devaluation of teaching duties” due to the new evaluation practices observed in academia.

The third impact of rankings on the academic profession observed in our study is the danger that the quality of research would deteriorate due to the above-mentioned changes. Some interviewees said that they prefer to undertake research which is certain to be published rather than research they are personally interested in. This point also arose in a study by Ter Bogt and Scapens (2012) in the Netherlands. The authors observed that it was possible to manipulate measured research performance to falsely claim, for example, that papers were co-written in order to “take advantage of the weights attached to joint publications” (Ter Bogt and Scapens, 2012: 478). Recent research argued that significant part of academics, especially those why try to maintain all their missions, are not “achieving satisfying performance in any domain according to international standards” (Tagliaventi et al., 2020: 1057). Roessler and Catacutan (2020) argue that as rankings overlook the diversity of academic profession missions, they cause a low visibility to a wide audience.

Ranking as a Strategy Guideline

For Hetzel (2010), even if ranking is not a strategy in itself, it can be used as a tool to help improve universities’ strategic positioning. While none of the top management interviewed confirmed any links between rankings and their institution’s strategy, the strategic documents analysed in our study demonstrate the influence of global ranking methodology on strategic decisions made at organisational level. For instance, one important strategic decision at UA was to merge with another “big” institution in order to “give the university new international visibility” and increase its international appeal (UA Projet d’établissement 2009-2012: 29).

Size is a key variable in some international rankings, like the Shanghai ranking, which compares the number of students, student-teacher ratios, and other numerical criteria (Tandilashvili and Tabatadze, 2016). A university contract from UB explains that “visibility is essential” for its attractiveness, which can be achieved “

by more rigorous signature and citation of our publications” (

Contrat d’établissement 2009-2012: 8). The document states that the rigorous signature and citation strategy paid off as the university managed to improve its position in the different rankings, such as QS and Times Higher Education. More examples on this point are given in

Figure 2.

Even if UC does not feature in most of the world rankings, the university is also concerned by the visibility issue. A UC report on international rankings advises the institution’s management team that, despite the inadequacy of the ranking methodology and UC scientific policies, “certain actions should be undertaken in order to improve the institution’s visibility” (UC report on international rankings: 18).

Previous studies have shown that international rankings now play a role in university strategies. The impact can be observed in annual reports and strategic plans (Dowsett, 2020; Marginson and Sawir, 2006; Dill and Soo, 2005) and in diverse actions undertaken aiming at improving HEIs’ position in rankings (Hendel and Stolz, 2008). For example, Elkin et al., (2020) showed that while rankings were not commonly mentioned in Nordic universities’ strategic plans, there were few exceptions, where universities clearly acknowledged that their goal was to figure among the top universities.

Over 40% of the interviewees (none from UC) confirmed our observation from the document analysis that the main objective of UA and UB is to do better in international rankings. To our question “what do you think is your university’s strategy?”, several replied that it is “to have a better position in the international rankings.” The presidents of both UA and UB also gave similar messages. For the president of UA, the real objective is to be more effective in research and teaching and, “if ranking helps to show the performance, then it’s good to be part of it.” Likewise, for the vice president of UB, it is important to be “visible at international level and, as research is done within a network and bibliometrics are important in rankings, it’s good to have a good position” (UB_5_VP).

Ranking as a Public Policy Vector

Consistent with the literature (Kosztyán et al., 2019; Lim and Williams Øerberg, 2017; Hazelkorn, 2011; Dill and Soo, 2005), the influence of rankings at national level in the French higher education system is observed in several pieces of legislation passed in France since the beginning of the 2000s designed to promote French higher education at international level. Three main goals emerged from our analysis of this legislation, ‘influenced’ by the international ranking methodologies, that are common to most of the reforms: e.g., to “increase international visibility”, to “promote French research” and to “make French university a world-class centre of research.”

One of the most important reforms in this sense is a law on the autonomy of universities, also called the law of Liberties and Responsibilities of Universities – LRU. This law mainly reorganizes university governance by giving the institutions local management in terms of budget, human resources and real estate. Influenced by the ranking methodologies, the legislation does not involve direct action. However, one of its three directives to universities is to “make university research visible at international level” (mission letter from Valérie Pécresse to Nicolas Sarkozy”, 5 July, 2007).

Another important policy is the PRES (Research and Higher Education Centres) reform which restructured the university map in France by grouping institutions into research and higher education centres. The PRES are federated structures that aim to achieve greater “readability and quality of research according to the highest international standards” through the cooperation of different HEI. Cooperation often occurs through mergers (e.g., merging universities in Strasbourg and Aix-Marseille) that significantly increase the size of universities. Many respondents noted the influence of rankings on this reform. "We can say that one way to achieve the goal [of better positioning] for France is to merge several universities to reach a larger size so as to become a strong player in a region, as well as at national and international level" (UC_1_VP). The last law pertaining to higher education has strengthened this university cooperation strategy since 2013. As a result, the number of university mergers increased in 2018-2019.

Ranking as a Source of Increased Competition

Ranking and competition is a two-way relationship. While some respondents directly blamed competition in the French higher education system on rankings, especially the Shanghai ranking, others considered that existing competition made it “necessary” to have rankings to help students easily see differences between institutions (UB_5_VP). This view is in line with the findings of Ter Bogt and Scapens (2012), according to which “the importance of rankings has increased largely because of the competition between universities, both nationally and internationally, as well as the more general internationalization of the university sector” (Ter Bogt and Scapens, 2012: 455).

Competition is also observed at three levels in our study: between academics, departments and universities. A shift from local to global competition between universities (Marginson 2007) reinforced existing rivalry between the French HEIs for financial resources and for attracting students and leading researchers. Rankings intensified a vertical competition between HEIs. However, our study does not confirm differentiation between university types as it is the case in most of Anglo-Saxon literature which mention a vertical differentiation between research-intensive HEIs and others and among the different grades of research-intensive HEIs (Marginson and van der Wende, 2007).

In addition to competition between universities for a better position in the international rankings, respondents also talk about competition “inside institutions across different disciplines” (UA_17_Dir). As noted above, previous studies have argued that the ranking system favours some disciplines more than others (Brooks, 2005; Hetzel, 2010; Ter Bogt and Scapens, 2012). Accordingly, one dean explained that “the problem is very different for natural and human sciences. There is a logic of individualism which is very strong in the humanities. So, this positioning obsession may not be very positive for them.” (UB_22_Dir). A recent study of Marques and Powell (2020) showed that units withing HEIs compete not only for material resources, but especially for symbolic resources, such as reputation and legitimacy. Our study also highlights a similar trend, where some research directors regret losing prestige because of not performing well according to international indicators. This is a sensitive topic in French HE system where there is a clear desire to end a historical, vertical differentiation between disciplines (see below).

Competition appears to be amplified between faculty as well. As some interviewees remarked, even if people do not admit it, competition has increased to be “better than others.” However, it is worth mentioning that this competition concerns research and not teaching. “Some young professors try to do a minimum of teaching and a maximum of research. This is due to increased pressure to publish. It’s very clearly stated in our objectives” (UA_16_Dir). This point was also noted in many previous studies mentioned in this paper. For example, a study on factors influencing extremely high or low research output from American business faculty members showed that research “stars” report being given more time to do research as they enjoy greater institutional support in the form of graduate assistants and summer research support. They also seem to have less course preparation (White et al., 2012). Our findings are in line with the observation of Marginson and van der Wende (2007) that intensified competition on the basis of research performance will exacerbate demand for high-quality scientific labour.

Our findings are summarized in figure 2 which shows the five main dimensions that emerged from our analyses and the constituent themes of these dimensions. Some examples from our empirical data that led to the formation of these themes are also given.

Figure 2.

Main dimensions of rankings’ impact on the French university.

Figure 2.

Main dimensions of rankings’ impact on the French university.

Attitude of French academics towards the changes experienced

Once the main impacts of rankings were identified, we measured the attitude of respondents regarding the changes they attribute to international rankings in order to understand how they judge these changes: i.e., positive, negative or neutral. To this end, we used simple descriptive statistics in NVivo software. As expected, most respondents (65%) had a negative attitude to the influence of rankings on university policies, with 87% expressing a negative opinion. Criticism included the methodology and the divergence of their ideology from the French system. There was also criticism regarding the incitement to competition caused by rankings. “I feel that the purpose of rankings is to install competition at national level in France. This means ignoring the weaker universities and seeing if they can survive. Competition is presented as a form of natural selection (UC_7_PR). Hiring a Nobel prize winner is also viewed as a negative point by the majority of UB employees. “I find it childish that UB recruited a Nobel prize winner just to improve its position in the international rankings” (UB_37_AC). The hierarchisation goes against the traditional value of equality strongly embedded in the French education.

However, in contrast to the results of previous studies, around 35% of the interviewees did not criticize the impact of rankings, instead describing it in a neutral and positive way. Two reasons can explain this attitude. First, the top, and middle management (presidents, vice-presidents, and deans) of both UA and UB found it positive that their universities were well placed in the rankings and thus “

increased their international visibility.” The second point is interesting in that it highlights a specific feature of the French higher education system. Universities are not the only HE institutions in France, but work alongside public and private

Grandes Écoles and research organisations (Tandilashvili, 2016). While this is also true of many other systems around the world, these organisations are particularly large and popular in France. A large part of society believes that the best education is provided by the

Grandes Écoles and that the best research comes from research organisations. (We do not discuss the accuracy of this belief in this paper.) As a result, the image of university is in decline. Thus, being part of a university and better ranked than most of the

Grandes Écoles gave the UA faculty a feeling of pride and increased their sense of corporate belonging. Despite criticising the ranking methodology, some declared, that

“it’s still prestigious to belong to the first French university in international rankings” (UA_13_Dir). Table 2 gives some examples of the main criticisms and positive opinions on rankings.

Table 2.

Main criticisms and positive opinion of the impact of rankings.

Table 2.

Main criticisms and positive opinion of the impact of rankings.

| Negative discourse |

Neutral and positive discourse |

| 65% |

35% |

| Not adapted to the French HE system |

Increases international visibility |

| Flawed methodology |

Enhances the sense of corporate belonging |

| Not appropriate to all disciplines |

Improves the image of the university |

| Creates competition |

|

Being part of a prestigious organisation also helps in development of organisational identity as opposed to disciplinary identity. Indeed, another particularity of the French higher education system is that faculty members traditionally identify themselves vis-à-vis their discipline rather than the institution in which they work (Tandilashvili and Tandilashvili, 2022). A number of factors can explain this. First, the faculty is recruited centrally by the Ministry of Higher Education and Research. Second, until 2008 (LRU law), human resource management was also centralised at Ministry level. Last, and probably most important, is the fact that until 1968, French university was divided vertically at the level of different disciplines. As Musselin (2001) explained, there was no coordination between faculties that were created around disciplines. This separation between the faculties was reinforced by the creation of hierarchical and centralized streams that managed their academic staff. Each faculty had its own internal regulations. This dual disciplinary division “was the main reason that made it impossible to create a university organisation in France” (Musselin, 2001: 29), even after the 1968 Faure law which ended this structure by creating independent interdisciplinary universities.

Conclusions

Evaluation, quality assurance, accreditation, ranking... this vocabulary is relatively new in French higher education, even if assessing research, institutions and faculty are longstanding procedures. What is new is the introduction of more overall assessment of university activities and faculty performance and, more broadly, their establishment within higher education policies.

The academic literature is rich with criticism of rankings, according to which the latter give viable results for only 5% of the world’s universities. Most French universities are left out of the equation. The reason for this can be traced to the ranking methodology that privileges large, scientific-based research universities, English-speaking countries, etc. (Tandilashvili, 2022; Luque-Martínez and Faraoni, 2020; Kosztyán et al., 2019; Tandilashvili and Tabatadze, 2016; Marginson, 2007). French universities are either flattered or disconcerted, depending on their position in the rankings. In the attempt to upgrade their positioning, they are strongly tempted to improve their performance specifically in the areas measured by ranking indicators.

Our research offers an in-depth case study of three French universities. We analysed the impact of international rankings on three levels. At national level, we observed their influence on public policies which are designed according to the ranking methodologies, creating a favourable environment for universities to improve their positions (Lim and Williams Øerberg, 2017; Hazelkorn, 2011; Dill and Soo, 2005). At organizational level, rankings influence university strategies and communication (Tandilashvili, 2022; Dowsett, 2020; Collins and Park, 2016; Hendel and Stolz, 2008; Marginson and Sawir, 2006). Complementing previous research, we offer the additional insight that the degree of influence largely depends on a university’s position in the rankings or its existing prestige. Universities that already have a well-established reputation nationally and/or those that are well-ranked will be less influenced by the rankings, while less “successful” universities will make more effort.

At individual level, the international rankings play an important role in terms of changing the academic profession. Faculty tends to privilege research over teaching and other activities, as research is more valued in international rankings and local evaluations (Tandilashvili and Tandilashvili, 2022; Bloch et al., 2021; Tagliaventi et al., 2020; Drucker-Godard, et al., 2013). As a result, there is more pressure for academic output (Ter Bogt and Scapens, 2012). Finally, we argue that rankings strengthen competition at all levels between faculty, disciplines and department, and universities (Marques and Powell, 2020; Ter Bogt and Scapens, 2012; Marginson, 2007).

It is still too early to predict what the outcome of these changes will be. Our paper describes the present state of affairs in the French higher education system. However, we may assume from the experience of some foreign countries that French universities will also strive more actively for a better position and thus, will accept the rules and norms of rankings (Dowsett, 2020; Collins and Park, 2016; Hazelkorn, 2011, 2013; Marginson and van der Wende, 2007). This will alter even further the academic profession. This observation on diversification of academic profession echoes with Whitchurch and Grodon (2010) study on the diversification of professional identities in higher education.

One interesting finding of the article is that, while it is hard to find positive outcomes of rankings in Anglo-Saxon research (see namely O’Connell, 2015), one interesting result we observed in our paper is the positive attitude of some faculty towards the changes experienced. Interviewed academics from the well ranked university acknowledge the benefits of being well represented in intranational rankings. The specificity of the French higher education system may explain this finding: on the one hand, a good position in the rankings gives universities an advantage in the context of competition with the Grandes Écoles and, on the other hand, it enhances the faculty’s sense of corporate belonging with respect to their institutions in contrast to the traditional identification with their profession.

Future studies could assess the situation according to the five main dimensions of the impact of rankings identified in this study. It will be interesting to see which of the trends toward change identified will be confirmed over the longer term.

References

- Aquillo, I., Ortega, J., and Fernandez, M. (2008). Webometric Ranking of World Universities: Introduction, Methodology, and Future Developments. Higher Education in Europe, 33(2-3), 233-244.

- Bloch, R., Hartl, J., O’Connell, C., and O’Siochru, C. (2021). English and German academics’ perspectives on metrics in higher education: Evaluating dimensions of fairness and organisational justice. Higher Education. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3,77–101. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R. (2005). Measuring Univeristy Quality. The Review of Higher Education, 29(1), 1-21.

- Cantwell, B. (2015). Laboratory management, academic production, and the building blocks of academic capitalism. Higher Education, 70(3), 487–502. [CrossRef]

- Chapuisat, X. and Laurent, C. (2008). Classements internationaux des établissements d’enseignement supérieur et de recherche. Quelques perspectives pour améliorer l’image des universités françaises, Horizons stratégiques, 2(2), 116-120.

- Collins, F. L., and Park, G.-S. (2016). Ranking and the multiplication of reputation: Reflections from the frontier of globalizing higher education. Higher Education, 72(1), 115–129. [CrossRef]

- Dill, D. D., and Soo, M. (2005). Academic quality, league tables, and public policy: A cross-national analysis of university ranking systems. Higher Education, 49(4), 495–533. [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, L. (2020). Global university rankings and strategic planning: a case study of Australian institutional performance. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. 42(4), 478-494.

- Drucker-Godard, C., Fouque, T., Gollety, M. and Le Flanchec, A. (2013). Le ressenti des enseignants-chercheurs : un conflit de valeurs. Gestion et management public, 2(2), 4-22. [CrossRef]

- Elken, M., Hovdhaugen, E., and Stensaker, B. (2016). Global rankings in the Nordic region: Challenging the identity of research-intensive universities? Higher Education, 72(6), 781–795. [CrossRef]

- Eloire, F. (2010). Le classement de Shanghai. Histoire, analyse et critique. L'Homme and la Société, 178(4), 17-38.

- Fave-Bonnet, M.F. (2002). Conflits de missions et conflits de valeurs: la profession universitaire sous tension. Connexions, n°78, 31-45.

- Harfi, M. and Mathieu, C. (2006). Classement de Shanghai et image internationale des universités : quels enjeux pour la France ? Horizons stratégiques, 2(2), 100-115.

- Hazelkorn, E. (2011). Rankings and the reshaping of higher education. The battle for world-class excellence. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hendel, D. D., & Stolz, I. (2008). A comparative analysis of higher education ranking systems in europe. Tertiary Education and Management, 14(3), 173–189.

- Hetzel, P. (2010). Oublier Shanghai : Classements internationaux des établissements d'enseignement supérieur. Conference proceedings of the Sénat, May the 6th, 2010. Retrieved November 2, 2021, from https://www.senat.fr/rap/r09-577/r09-57715.html#toc45.

- Kosztyán, Z.T., Banász, Z., Csányi, V.V. et al. (2019). Rankings or leagues or rankings on leagues? - Ranking in fair reference groups. Tertiary Education and Management, 25, 289–310 . [CrossRef]

- Lim, M. A., and Williams Øerberg, J. (2017). Active instruments: on the use of university rankings in developing national systems of higher education. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 1(1), 91–108.

- Luque-Martínez, T. and Faraoni N. (2020). Meta-ranking to position world universities, Studies in Higher Education, 45(4), 819-833. [CrossRef]

- Lussault, M. (2010). Palmarès et classements : la formation et la recherche sous tension. Revue Internationale d’Education de Sèvres, vol.54, 29-38.

- Marginson, S. (2007). Global University Rankings: Implications in general and for Australia. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 29(2), 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S., and Sawir, E. (2006). University Leaders’ Strategies in the Global Environment: A Comparative Study of Universitas Indonesia and the Australian National University. Higher Education, 52, 343–373. [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S., and van der Wende, M. (2007). To Rank or To Be Ranked: The Impact of Global Rankings in Higher Education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3/4), 306-329.

- Marques, M., and Powell, J. J. W. (2020). Ratings, rankings, research evaluation: How do Schools of Education behave strategically within stratified UK higher education? Higher Education, 79(5), 829–846. [CrossRef]

- Millot, B. (2015). International rankings: Universities vs. higher education systems, International Journal of Educational Development, 40, 156-165.

- Musselin, Ch. (2001). La longue marche des universités françaises, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 218 pages.

- Naszályi, P. (2010). ‘Lorsque le sage montre la lune, l'imbécile regarde le doigt... ou le classement de Shanghai’ proverbe chinois. La Revue des Sciences de Gestion, vol. 3-4, 243-244.

- O’Connell, C. (2015). An examination of global university rankings as a new mechanism influencing mission differentiation: the UK context. Tertiary Education and Management, 21, 111–126 . [CrossRef]

- Parker, M. and Jary D. (1995). The Mc University, SAGE Publications.

- Roessler, I. and Catacutan, K. (2020). Diversification around Europe – performance measuring with regard to different missions. Tertiary Education and Management, 26, 265–279 . [CrossRef]

- Tagliaventi, M. R., Carli, G., and Cutolo, D. (2020). Excellent researcher or good public servant? The interplay between research and academic citizenship. Higher Education, 79(6), 1057–1078. [CrossRef]

- Tandilashvili, N. (2016). Le managérialisme et l’identité universitaire ; le cas de l’université française. Doctoral dissertation, Paris Nanterre University, www.theses.fr.

- Tandilashvili, N. (2022). La transformation de l’université française : La perception des universitaires. Gestion et management public, 10(N1), p.55-76. [CrossRef]

- Tandilashvili, N. and Tabatadze, M., (2016). International university rankings: review and future perspectives. World science, 12(2), 67-72.

- Tandilashvili, N. and Tandilashvili, A. (2022). Academics’ perception of identity (re)construction: a value conflict created by performance orientation. Journal of Management and Governance, 26, p.389–416 . [CrossRef]

- Tandilashvili, N., Balech, S. and Tabatadze, M. (2023). The role of affective ties in the asymmetrical relationship between student satisfaction and loyalty. Comparative study of European business schools, Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, . [CrossRef]

- Ter Bogt, H. J. and Scapens, R. W. (2012). Performance Management in Universities: Effects of the Transition to More Quantitative Measurement Systems, EAR - European Accounting Review. 21(3), 451-497.

- Van Raan, A. F.J., van Leeuwen T.N., and Visser M.S. (2010). Germany and France are wronged in citation-based rankings. Scientometrics, 88(2), 495-498.

- Vinokur, A. (2008). Vous avez dit ‘autonomie’?. Mouvements, 55-56(3), 72-81.

- Whitchurch, C. and Gordon, G. (2010). Diversifying Academic and Professional Identities in Higher Education: Some management challenges. Tertiary Education and Management, 16, 129–144 . [CrossRef]

- White, Ch. S., James K., Burke L. A. and Allen R. A. (2012). What makes a “research star”? Factors influencing the research productivity of business faculty. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 61(6), 584-602.

- Wilkins, S., Huisman, J. (2015). Stakeholder perspectives on citation and peer-based rankings of higher education journals. Tertiary Education and Management, 21, 1–15 . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).