Submitted:

22 January 2024

Posted:

23 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

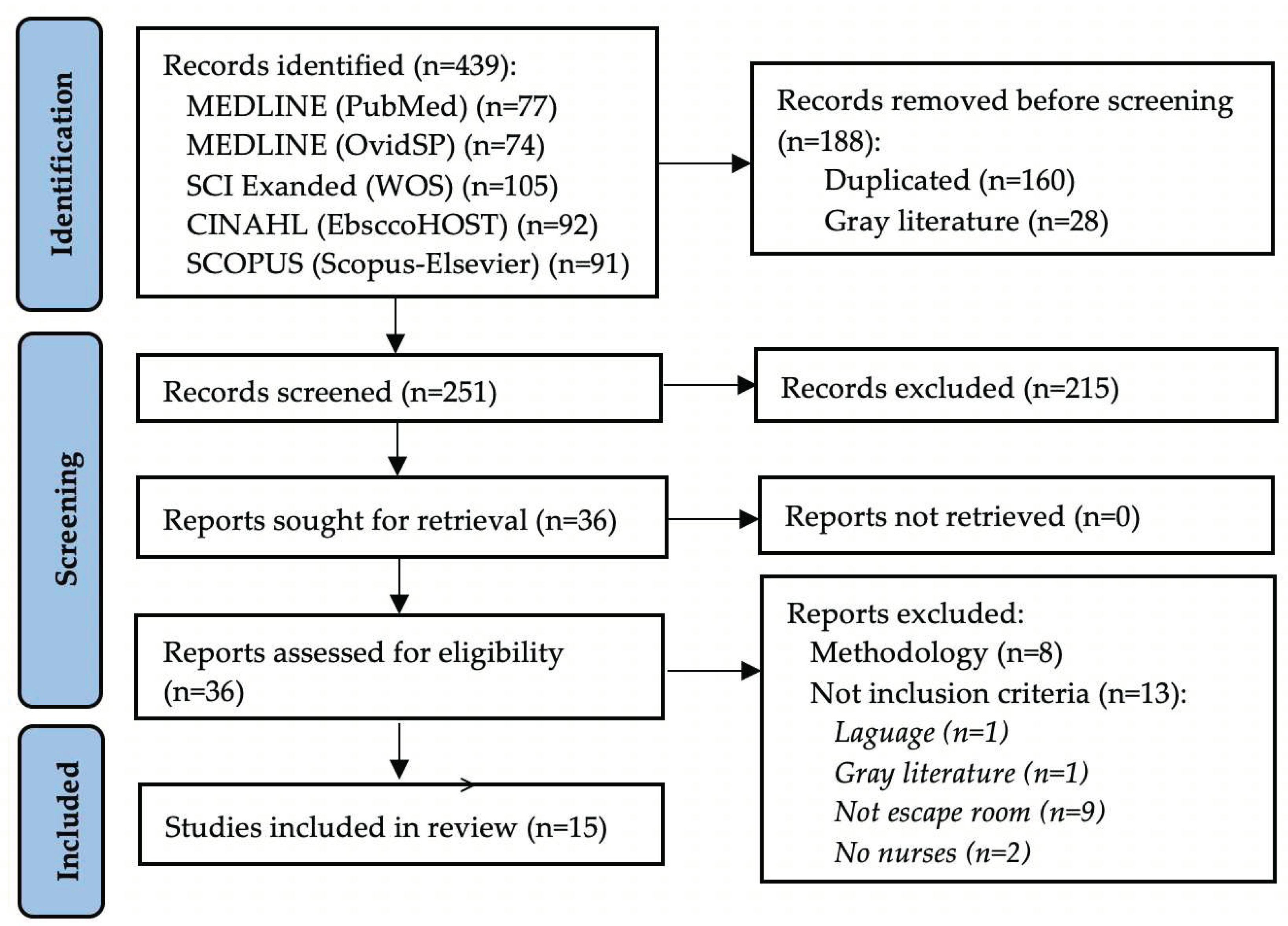

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kowitlawakul, Y.; Tan, JJM.; Suebnukarn, S.; Nguyen, HD.; Poo, DCC.; Chai, J.; Wang, W.; Devi, K. Utilizing educational technology in enhancing undergraduate nursing students' engagement and motivation: A scoping review. J Prof Nurs. 2022, 42, 262-275. [CrossRef]

- Jose, MM.; Dufrene, C. Educational competencies and technologies for disaster preparedness in undergraduate nursing education: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2014,34,543-51. [CrossRef]

- Dahalan, F.; Alias, N.; Shaharom, MSN. Gamification and Game Based Learning for Vocational Education and Training: A Systematic Literature Review. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2023,1-39. [CrossRef]

- Quek, LH.; Tan, AJQ.; Sim, MJJ.; Ignacio, J.; Harder, N.; Lamb, A.; Chua, WL.; Lau, ST.; Liaw, SY. Educational escape rooms for healthcare students: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2024, 132,106004. [CrossRef]

- van Gaalen, AEJ.; Brouwer, J.; Schönrock-Adema, J.; Bouwkamp-Timmer, T.; Jaarsma, ADC.; Georgiadis, JR. Gamification of health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021,26,683-711. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yin, X.; Yin, W.; Dong, X.; Li, Q. Evaluation of gamification techniques in learning abilities for higher school students using FAHP and EDAS methods. Soft comput. 2023,1-19. [CrossRef]

- Gorbanev, I.; Agudelo-Londoño, S.; González, RA.; Cortes, A.; Pomares, A.; Delgadillo, V.; Yepes, FJ.; Muñoz, Ó. A systematic review of serious games in medical education: quality of evidence and pedagogical strategy. Med Educ Online. 2018,23,1438718. [CrossRef]

- Eukel, H.; Morrell, B. Ensuring Educational Escape-Room Success: The Process of Designing, Piloting, Evaluating, Redesigning, and Re-Evaluating Educational Escape Rooms. Simul. Gaming, 2021, 52, 18-23. [CrossRef]

- Antón-Solanas, I.; Rodríguez-Roca, B.; Urcola-Pardo, F.; Anguas-Gracia, A.; Satústegui-Dordá, PJ.; Echániz-Serrano, E.; Subirón-Valera, AB. An evaluation of undergraduate student nurses' gameful experience whilst playing a digital escape room as part of a FIRST year module: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2022,118,105527. [CrossRef]

- Reinkemeyer, EA.; Chrisman, M.; Patel, SE. Escape rooms in nursing education: An integrative review of their use, outcomes, and barriers to implementation. Nurse Educ Today. 2022,119,105571. [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI, 2020. Available from JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

- Page, MJ.; McKenzie, JE.; Bossuyt, PM.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, TC.; Mulrow, CD.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, JM.; Akl, EA.; Brennan, SE.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, JM.; Hróbjartsson, A.: Lalu, MM.; Li, T.; Loder, EW.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021. 372,71. [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen, ML.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, AP.; Moher, D.; Page MJ.; Koffel, JB. PRISMA-S Group. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev. 2021,10,39.

- Chen, D.; Liu, F.; Zhu, C.; Tai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. The effect of an escape room game on college nursing students' learning attitude and game flow experiences in teaching safe medication care for the elderly: an intervention educational study. BMC Med Educ. 2023, 23, 945. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, HJ.; Chou, YT.; Wu, HC.; Jen, HJ.; Shen, CH.; Lin, CJ.; Chou, KR.; Ruey-Chen. An online escape room-based lesson plan to teach new nurses violence de-escalation skills. Nurse Educ Today. 2023,123, 105752.

- Sara, A.; Hunker, DF. An Initiative to Increase Nurse Knowledge and Decrease Postpartum Readmissions for Preeclampsia. Nurs Womens Health. 2023,27,337-343. [CrossRef]

- Schmuhl, KK.; Nagel, S.; Tamburro, R.; Jewell, TM.; Gilbert, E.; Gonzalez, A.; Sullivan, DL.; Sprague, JE. Better together: utilizing an interprofessional course and escape room to educate healthcare students about opioid use disorder. BMC Med Educ. 2023, 23, 917. [CrossRef]

- Yang, CL.; Chang, CY.; Jen, HJ. Facilitating undergraduate students' problem-solving and critical thinking competence via online escape room learning. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023, 73, 103828. [CrossRef]

- Hursman, A.; Richter, LM.; Frenzel, J.; Viets Nice, J.; Monson, E. An online escape room used to support the growth of teamwork in health professions students. J Interprof Educ Pract. 2022,29,100545. [CrossRef]

- Millsaps, ER.; Swihart, AK.; Lemar, HB. Time is brain: Utilizing escape rooms as an alternative educational assignment in undergraduate nursing education. Teaching and Learning in Nursing. 2022, 17, 323-327. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Torres, G.; Cardona, D.; Requena, M.; Rodriguez-Arrastia, M.; Roman, P.; Ropero-Padilla, C. The impact of using an "anatomy escape room" on nursing students: A comparative study. Nurse Educ Today. 2022, 109,105205. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ferrer, JM.; Manzano-León, A.; Cangas, AJ.; Aguilar-Parra, JM. A Web-Based Escape Room to Raise Awareness About Severe Mental Illness Among University Students: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Serious Games. 2022, 10, e34222. [CrossRef]

- Wettergreen, SA.; Stewart, MP.; Huntsberry, AM. Evaluation of an escape room approach to interprofessional education and the opioid crisis. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2022,14, 387-392. [CrossRef]

- Fusco, NM.; Foltz-Ramos, K.; Ohtake, PJ. An Interprofessional Escape Room Experience to Improve Knowledge and Collaboration Among Health Professions Students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022, 86, ajpe8823. [CrossRef]

- Foltz-Ramos, K.; Fusco, NM.; Paige, JB. Saving patient x: A quasi-experimental study of teamwork and performance in simulation following an interprofessional escape room. J Interprof Care. 2021,1-8. [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.; Campbell, N. Effectiveness of an escape room for undergraduate interprofessional learning: a mixed methods single group pre-post evaluation. BMC Med Educ. 2021, 21, 220. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Puertas, L.; Márquez-Hernández, VV.; Román-López, P.; Rodríguez-Arrastia, MJ.; Ropero-Padilla, C.; Molina-Torres, G. Escape Rooms as a Clinical Evaluation Method for Nursing Students. Clin Simul Nurs.2020,49, 73-80. [CrossRef]

- Morrell, BLM.; Eukel, HN. Escape the Generational Gap: A Cardiovascular Escape Room for Nursing Education. J Nurs Educ. 2020, 59, 111-115. [CrossRef]

- Katonai, Z.; Gupta, R.; Heuss, S.; Fehr, T.; Ebneter, M.; Maier, T.; Meier, T.; Bux, D.; Thackaberry, J.; Schneeberger AR. Serious Games and Gamification: Health Care Workers' Experience, Attitudes, and Knowledge. Acad Psychiatry. 2023,47,169-173. [CrossRef]

- Gentry, SV.; Gauthier, A.; L'Estrade Ehrstrom, B.; Wortley, D.; Lilienthal, A.; Tudor Car, L.; Dauwels-Okutsu, S.; Nikolaou, CK.; Zary, N.; Campbell, J.; Car J. Serious Gaming and Gamification Education in Health Professions: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e12994. [CrossRef]

- Akl, EA.; Kairouz, VF.; Sackett, KM.; Erdley, WS.; Mustafa, RA.; Fiander, M.; Gabriel, C.; Schünemann, H. Educational games for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, CD006411. [CrossRef]

- Hintze, TD.; Samuel, N.; Braaten, B. A Systematic Review of Escape Room Gaming in Pharmacy Education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2023, 87,100048. [CrossRef]

- Eukel, H.; Morrell, B. Ensuring Educational Escape-Room Success: The Process of Designing, Piloting, Evaluating, Redesigning, and Re-Evaluating Educational Escape Rooms. Simul. Gaming. 2021, 52, 18-23. [CrossRef]

- Chicca, J.; Shellenbarger, T. Connecting with Generation Z: Approaches in nursing education. Teaching and Learning in Nursing.2018, 13, 180-184. [CrossRef]

- Eukel, H.; Frenzel, J.; Frazier, K.; Miller, M. Unlocking Student Engagement: Creation, Adaptation, and Application of an Educational Escape Room Across Three Pharmacy Campuses. Simul. Gaming. 2020, 51, 167-179. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urquiza, JL.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Albendín-García, L.; Correa-Rodríguez, M.; González-Jiménez, E.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, GA. The impact on nursing students’ opinions and motivation of using a “nursing escape room” as a teaching game: A descriptive study. Nurse Educ Today. 2019, 72, 73-76. [CrossRef]

- Shah, AS.; Pitt, M.; Norton, L. ESCAPE the Boring Lecture: Tips and Tricks on Building Puzzles for Medical Education Escape Rooms. J Med Educ Curric Dev.2023, 10, 23821205231211200. [CrossRef]

- Fanning, RM.; Gaba, DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc. 2007,2, 115-25. [CrossRef]

- Eppmann, R.; Bekk, M.; Klein, K. Gameful Experience in Gamification: Construction and Validation of a Gameful Experience Scale [GAMEX]. Journal of Interactive Marketing.2018, 43, 98-115. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Puertas, L.; García-Viola, A.; Márquez-Hernández, VV.; Garrido-Molina, JM.; Granados-Gámez, G.; Aguilera-Manrique, G. Guess it (SVUAL): An app designed to help nursing students acquire and retain knowledge about basic and advanced life support techniques. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021,50, 102961. [CrossRef]

- Kachaturoff, M.; Caboral-Stevens, M.; Gee, M.; Lan, VM. Effects of peer-mentoring on stress and anxiety levels of undergraduate nursing students: An integrative review. J Prof Nurs. 2020,36,223-228. [CrossRef]

- Najjar, RH.; Lyman, B.; Miehl, N. Nursing students’ experiences with high-fidelity simulation. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh.2015,12, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Reed, JM.; Ferdig, RE. Gaming and anxiety in the nursing simulation lab: A pilot study of an escape room. J Prof Nurs. 2021, 37, 298-305. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, A.; Franklin, K.; Edwards, TR.; Slivinski, A. Escaping the Silos: Utilization of a Pediatric Trauma Escape Room to Promote Interprofessional Education and Collaboration. J Trauma Nurs. 2023, 30,364-370. [CrossRef]

- Fusco, NM.; Foltz-Ramos, K.; Zhao, Y.; Ohtake, PJ. Virtual escape room paired with simulation improves health professions students' readiness to function in interprofessional teams. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2023,15,311-318. [CrossRef]

- Abensur Vuillaume, L.; Laudren, G.; Bosio, A.; Thévenot, P.; Pelaccia, T.; Chauvin, A. A Didactic Escape Game for Emergency Medicine Aimed at Learning to Work as a Team and Making Diagnoses: Methodology for Game Development. JMIR Serious Games. 2021, 9, e27291. [CrossRef]

- Guckian, J.; Eveson, L.; May, H. The great escape? The rise of the escape room in medical education. Future Healthc J. 2020, 7, 112–115. [CrossRef]

- Dams, V.; Burger, S.; Crawford, K.; Setter, R. Can You Escape? Creating an Escape Room to Facilitate Active Learning. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2018, 34, E1–E5. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, C.; Teaford, H.; Taubenheim, A.; Boland, P.; Sick B. Escaping the professional silo: an escape room implemented in an interprofessional education curriculum. J Interprof Care. 2019, 33, 573-575. [CrossRef]

- Veldkamp, A.; van de Grint, L.; Knippels, M.-C. P. J.; van Joolingen, W. R. Escape Education: A Systematic Review on Escape Rooms in Education. Educ Res Rev. 2020, 31, 100364. [CrossRef]

| Database | Date | Search Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Medline (PubMed) |

2022/12/29 |

("education, nursing"[MeSH Terms] OR "Nursing Education"[All Fields] OR ("education"[All Fields] AND "nursing"[All Fields]) OR "Nursing Education"[All Fields] OR ("educations"[All Fields] AND "nursing"[All Fields])) OR "Nursing Educations"[All Fields]) AND ("Gamification"[MeSH Terms] OR "escape room"[All Fields]) |

| 2023/12/29 | ("education, nursing"[MeSH Terms] OR "Nursing Education"[All Fields] OR ("education"[All Fields] AND "nursing"[All Fields]) OR "Nursing Education"[All Fields] OR ("educations"[All Fields] AND "nursing"[All Fields])) OR "Nursing Educations"[All Fields]) AND ("Gamification"[MeSH Terms] OR "escape room"[All Fields]) Filters: from 2022/12/29 - 2024/1/1 | |

| Medline (Ovid) |

2022/12/29 | Gamification.mp. |

| "escape room".m_titl. | ||

| 1 or 2 | ||

| Education, Nursing.mp. | ||

| 3 and 4 | ||

| 2023/12/29 | limit 3 to yr="2023 - 2024" | |

| CINHAL (EbsccoHOST) |

2022/12/29 | S1 TX gamification |

| S2 TX "escape room" OR TX "scape room" OR TX "escape rooms | ||

| S3 TX "escape room" OR TX "scape room" OR TX "escape rooms") AND (S1 OR S2) | ||

| S4 TX "nursing education" OR TX "education, nursing" | ||

| S5(TX "nursing education" OR TX "education, nursing") AND (S3 AND S4) | ||

| 2023/12/29 | S5(TX "nursing education" OR TX "education, nursing") AND (S3 AND S4) Publication date: 20230101-20231231 | |

| Scopus (Scopus-Elsevier) |

2022/12/29 | ( ALL ( "escape room" OR "escape rooms" OR "scape room" ) OR INDEXTERMS ( gamification ) ) AND ( INDEXTERMS ( "education, nursing" OR "nursing education" ) ) |

| 2023/12/29 | ( ALL ( "escape room" OR "escape rooms" OR "scape room" ) OR INDEXTERMS ( gamification ) ) AND ( INDEXTERMS ( "education, nursing" OR "nursing education" ) ) AND PUBYEAR > 2022 AND PUBYEAR < 2025 | |

| SCI Expanded (Web of Science) | 2022/12/29 | ((TS=("gamification")) OR TS=("escape room" OR "scape room" OR "escape rooms")) AND TS=("education, nursing" OR "nursing education") |

| 2023/12/29 | ((TS=("gamification")) OR TS=("escape room" OR "scape room" OR "escape rooms")) AND TS=("education, nursing" OR "nursing education") 2022-12-29 to 2024-01-01 (Index Date) |

| Author (Year) Country |

Design | Themes and Learning topics | Aim | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. (2023) China [14] |

Quasi experimental pre-post with CG1 | Gerontological Nursing (Safe Medication Care for the Elderly people) | To determine the effects of an intervention educational activity based on an ER2 game on nursing students’ learning attitude and the game flow experience after they had received nursing classroom teaching on safe medication use in older adults | During the teaching process of the Gerontological Nursing course, an ER game added at the end of classroom teaching can improve nursing students’ learning attitude and also help them to have a good game |

| Hsu et al. (2023) Taiwan [15] |

Quasi experimental pre-post | Workplace violence | To examine the effects of an online ER simulation on newly qualified nurses' violence de-escalation skills, their knowledge of violence characteristics collective efficacy, and learnin satisfaction | The proposed ER-based course format can be used in clinical education and applied in other nursing training courses, Newly qualified nurses who participated in this study reported tha the proposed course was innovative, interesting, and practical; helped them retain and apply their knowledge; and promoted teamwork |

| Sara & Hunker (2023) USA [16] |

Quasi experimental pre-post (Quality improvement Project) |

Maternity care (Preeclampsia) | To increase nurses’ knowledge on the care and management of women with preeclampsia in the postpartum period and to improve maternal outcomes by reducing postpartum readmission rates of women with preeclampsia | Using innovative education, such as an ER–style game to increase nurse knowledge, provides the opportunity to engage nurses and potentially improve maternal outcomes |

| Schmuhl et al. (2023) USA [17] |

Quasi experimental pre-post | Interprofessional Colaboration and Opioid Use Disorder |

To determine the impact of an innovative interprofessional educational activity on healthcare professional students’ learning. The educational activity targeted student knowledge of opioid use disorder and perceptions of working with an interprofessional team while caring for patients with opioid use disorder | An interprofessional educational experience including both an asynchronous course and virtual synchronous ER can increase participant knowledge around opioid use disorder and may improve student perceptions of working with an interprofessional team and caring for patients with opioid use disorder |

| Yang et al. (2023) Taiwan [18] |

Quasi experimental with CG | Maternity care | To identify the efficiency of ER activities in terms of enhancing nursing students’ retention of maternity-related knowledge and their overall learning performance | Maternity ER emerged as an online game-based approach that effectively stimulated nursing students and can serve as a practical resource for engaging in maternity care learning |

| Hursman et al. (2022) USA [19] |

Quasi experimental pre-post | Interprofessional Colaboration | To enhance interprofessional students’ perceptions of their ability to communicate effectively and respectfully, work together to complete a task, and to develop knowledge of the unique roles of members of the healthcare team | This activity lays the groundwork for collaborative telehealth students will be exposed to in their futures and the results infer that the activity can help to build collaboration among team members, even those not in the same physical space. It also shows that virtual ER can be an effective activity to increase interprofessional teamwork perceptions in the online classroom environment and could prove to be useful in other online interprofessional settings |

| Millsaps et al. (2022) USA [20] |

Quasi experimental pre-post | Neurological disorders with a focus on stroke | To promote engagement in undergraduate nursing coursework |

ER experiences can be utilized in the preparation of associate degree nursing education to engage students while also ensuring that students meet key learning objectives |

| Molina-Torres et al. (2022) Spain [21] |

Quasi experimental pre-post with CG | Anatomy | To evaluate the effectiveness of the ER for anatomy-related knowledge retention in nursing and the perceived value of the game | According to the findings, the “Anatomy ER” is a game-based approach that motivates students and constitutes a down-to-earth resource for anatomy learning in healthcare students |

| Rodríguez-Ferrer et al. (2022) Spain [22] |

RCT3 | Stigma again Severe Mental Illness |

To examine the effect of the Without Memories ER on nursing students’stigma against Several Mental Illness | The Without Memories ER can be used as an effective tool to educate and raise awareness about stigmatizing attitudes toward Several Mental Illness in university students studying health care |

| Wettergreen et al. (2022) USA [23] |

Quasi experimental pre-post | Interprofessional education and the opioid crisis |

To evaluate the use of an interprofessional ER activity to increase clinical knowledge related to the opioid crisis. The secondary objective was to evaluate change I attitudes toward interprofessional collaboration | The use of an interprofessional ER as an educational method was effective in increasing some aspects of opioid crisis related knowledge and enhancing attitudes toward interprofessional collaboration. The educational model is applicable to various topics and inter-professional groups |

| Foltz-Ramos et al. (2021) USA [25] |

Quasi experimental pre-post with CG | Interprofessional Colaboration | To create and test the use of an interprofessional ER, as a method improve teamwork, prior to interprofessional simulation | ER can, in a brief period of time, improve teamwork and consequently performance during simulation. Findings support the use of ER in interprofessional education curriculum as a method to promote teamwork |

| Fusco et al. (2022) USA [24] |

RCT | Interprofessional Colaboration Sepsis management and post-operative precautions (hip arthroplasty) |

To extend our understanding of ER pedagogical design by investigating the impact of escape room puzzle content on changes in student immediate recall knowledge and demonstration of interprofessional skills during a subsequent interprofessional simulation | ER can be an innovative pedagogical tool that can positively impact immediate recall knowledge and interprofessional collaborative skills of health professions students |

| Moore & Campbell (2021) Australia [26] |

Quasi experimental pre-post | Interprofessional practice knowledge and competencies |

To investigate the utility of an ER coupled with a debriefing workshop as an effective andengaging interprofessional learnin activity. To evaluate the impact of the ER on participant knowledge about interprofesional practice and teamwork. To evaluate the impact of the ER through participant reflection on their personal contributions to the team | The ER intervention added value to the placement curriculum and proved flexible for a heterogeneous student cohort |

| Gutiérrez-Puertas et al. (2020) Spain [27] |

Quasi experimental with CG | Gameful experience Clinical skills |

To understand the gameful experience and satisfaction of nursing students in the evaluation of their clinical skills using an ER | ER are a useful tool for the evaluation of nursing students compared with usingthe objective structured clinical evaluation |

| Morrel & Eukel (2020) USA [28] |

Quasi experimental pre-post | Cardiovascular critical care |

To evaluate the impact of a cardiovascular ER on student knowledge, as well as to understand student perceptions of the educational innovation | The cardiovascular ER increased student knowledge and was positively received by students. The educational innovation encouraged student engagement in learning, content application, peer communication, and nursing practice skills |

| Author (year) |

Instruments | Session (time minutes) |

Size Team (nursing for team) |

Study population/ sample (IG1/CG2) |

Lost case (CG/IG) |

Pre Mean (SD3) (IG/CG) |

Post Mean (SD) (IG/CG) |

p-value | Size effect | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. (2023) [14] | - LAS4: 23 items, four subscales: learning interest, learning experience, learning habit, and professional recognition. Total range 23-92. Higher scores indicate better learning attitude. - GFEQ5: 19 items, five subscales: sense of control, telepresence, distorted sense of time, enjoyable feelings, and being unconscious of irrelevant surroundings. Total range 19-95. Higher scores indicate better game flow experience. |

ER6 (40) | 6-8 (6-8) | 84 Nursing students IG= 41 (6 group) CG= 33 |

None | - LAS: IG= 60.93 (2.33) CG= 61.51(2.32) - CFEQ: IG= 63.27 (2.48) |

- LAS: IG= 73.17 (1.67) CG= 61.63 (2.66) - CFEQ: IG= 81.29 (2.49) |

- LAS: P<0.001 t-test - GFEQ: p<0.001 t-test |

- LAS: Cohen’s d 5.196 (post test score) - GFEQ: Cohen’s d 5.253 |

- LAS (total score 45) for the ER 43.83 (4.49) |

| Hsu et al. (2023) [15] |

- A 10 multiple-choice questionnaire (10 to 100 points total) for assessment of Violence de-escalation skills and knowledge. - CEQ8 (total score 40). |

Pretest (5). Virtual ER (60). Post Online Lecture for explain each puzle (25). |

6-8 (6-8) | 106 Newly qualified nurses. No CG |

None | - Violence de-escalation: 84.53 (11.56). - CEQ: 37.34 (4.88) |

- Violence de-escalation: 93.58 (10.07) - CEQ: 38.69 (3.84) |

- Violence de-escalation: p<0.001 (One-Way ANOVA) - CEQ: p<0.001 paired t- test |

NC7 | |

| Sara & Hunker (2023) [16] | - Knowledge survey of preeclampsia: 10-item multiple-choice. - Maternal outcomes represented by the measurement of postpartum readmission rates of women with preeclampsia. |

Nine educational sessions (7-9 nurses per session) ER (30). Debriefing session |

3-5 (3-5) | 71 nurses in a postpartum care unit (9 sessions) No CG |

None | Knowledge survey 7.44 (8.49) |

Knowledge survey 8.49 (1.33) |

Knowledge survey p<0.001 paired t test |

NC | Post implementation readmission rate for postpartum women with preeclampsia 1.49% (Benchmark-National average 3.55%). |

| Schmuhl et al. (2023) [17] | - ATHCT9 (14 item). Likert (1= strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=agree, 4=strongly agree). - Survey to assess perceptions towards caring for patients with Opioid Use Disorder (11 item) Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=agree, 4=strongly agree). |

Synchronous virtual ER Zoom breakout romos (30) ER (90) |

Not reported (Team inter professional) | 402 health professional students (216 Nursing students) No CG |

None | - ATHCT: performed for 14 items but NP for total score. - Opioid Use Disorder: Performed for 11 items (NP for a total score). |

- ATHCT: Performed for 14 items but NP for total score. - Opioid Use Disorder: performed for 11 items (NP for a total score). |

- ATHCT: p<0.05 t-test - Opioid Use Disorder: p<0.05 (7 ítems) t-test |

NC | Following ER, students strongly agreed that their intentions were to change and work collaboratively on interprofessional teams |

| Yang et al. (2023) [18] |

- Knowledge test of maternity care: 10 items (maximum score 100 points). - Problem-solving scale: 5 items 5-points Likert scale. - Critical thinking questionnaire: 6 items to assess students’ critical thinking abilities, knowledge and confidence. |

Online game-based ER (50) | 6-7 (6-7) | 42 Nursing students IG=21 (Online game-based ER). CG=21 (online learning without ER). |

None | NP10 | - Knowledge: IG= 30.36 CG= 12.64 - Problem-solving: IG= 28.33 CG= 14.67 - Critical thinking: IG= 31.76 CG= 11.24 |

- Knowledge: p<0.001 Mann-Whitney U. - Problem-solving: p<0.001 Mann-Whitney U. - Critical thinking: p<0.001 Mann-Whitney U. |

NC | |

| Hursman et al. (2022) [19] |

Questionnaire Pre-Post: - Pre-survey 8-item of Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice. - Post-survey 26-item same items more 17 items to evaluate the effectiveness, usefulness of the activity and attitudes toward gaming. |

ER (60) |

5-7 (1-2) | 176 heath science students (95 Nursing students) No CG |

None | NP for 6 items pre | NP for 6 items post | 6 ítems (p˂0.001) |

NC | |

| Millsaps et al. (2022) [20] |

- 5 questions of knowledge about Stroke. |

Prequiz (10) Pre briefing (25) ER (30) Debriefing (25) |

4 (4) | Under- graduate ASN11 students 24 students (12 morning session, and 12 afternoon session). No CG. |

None | Knowledge: 2.9 (1.06) Median: 3 |

Knowledge: 3.8 (0.66) Median: 4 |

p=0.001 for median (Wilconxon) |

NC | Not indicated puntuation system. |

| Molina-Torres et al. (2022) [21] |

-10 questions of Knowledge about Anatomy (0-10 points) | ER (15) |

4 (4) | 248 nursing students IG= 128 CG= 120 |

None | NP | Knowledge: IG= 8.94 (0.96) CG= 7.70 (1.25) |

Post p= 0.001 (Student's t) |

NC | Also measured IG satisfaction by means of Satisfaction Questionnaire12 (26 questions 1 to 5 (higher score higher satisfaction). |

| Rodríguez-Ferrer et al. (2022) [22] |

- Attributional Questionnaire (14-point Likert 1 to 9; higher score greater number of stigmatizing attitudes toward people with severe mental illness). - Motivation Questionnaire for Cooperative Playful Learning Strategies (Likert scale, ranging 1 to 7). |

ER (60) | 4 (4) | 316 nursing students randomized IG= 204 (ER without memories) CG=112 (ER Locked In) |

IG= 7 CG= 3 Final sample n= 306 IG= 197 CG= 109 |

Higher scores greater stigma expressed: IG= 47.57 (16.7) CG= 49.56 (16.03) |

Higher scores greater stigma expressed: IG= 30.83 (14.79) CG= 49.55 (16.02) |

Post p˂0.001 (ANOVA) |

0.258 | |

| Wettergreen et al. (2022) [23] |

- SPICE-R13 Instrument (multiple response and true/false). Likert scale from 1 to 5 points (higher score greater agreement with the statement) | Pre-brief (10) ER (60) Debrief (20) |

5 (not reported) |

80 Heath science students (7 nursing students). No CG |

10 lost | SPICE-R Higher score greater agreement. Mean: 4.48 |

SPICE-R Higher score greater agreement. Mean: 4.64 |

Knowledge: post (p˂0.05) McNemar’s Exact Test. |

NC | Pre Knowledge:14 62.92% Post Knowledge: 74.30% |

| Foltz-Ramos et al. (2021) [25] |

- Knowledge Test (10 items multiple choice test). - ISVS-2115: 21 items 7-point Likert scale. Items scores are added together and divided by 21 to calculate overall score. |

ER (30) | 5(2) | Senior nursing, third-year pharmacy, and second-year physical therapy students. IG= 133 (Nursing: 54) ER acute management of sepsis CG= 129 (Nursing: 55) ER general acute care. |

None | - Knowledge#1: IG= 6.8 (1.9) CG= 6.7 (1.6) - ISVS-21: IG= 5.1 (0.92) CG= 5.2 (0.97) |

- Knowledge#2: IG= 7.7 (1.6) CG= 7.3 (1.7) - ISVS-21: IG= 6.0 (0.77) CG= 6.0 (0.82) |

- Knowledge#3: (post) p= 0.06 - ISVS-21: (post) p= 0.70 |

NC | Three knowlegde measures #1, #2, #3 |

| Fusco et al. (2022) [24] |

- ISVS-21. - OIPC16 tool: First 10 items: Adequacy of team to a common vision of the situation. Ramaining 10 items: Team’s ability to develop a common action plan. For each item, rated a 3-point likert (1= inadequate, 2= more-less adequate, 3= adequate) |

ER (30) | 4(2) | 233 Nursing and pharmacy students (118 Nursing students IG= 120 (Simulation) CG= 113 (ER + simulation) |

None | - ISVS-21: IG= 5.3 (0.92) CG= 5.2 (1.0). - OIPC: pre NP |

- ISVS-21: IG= 6.0 (0.72) CG= 5.9 (0.8) - OIPC: Median (IQR17) IG Items 1-10: 27 (26-28) Items 11-20: 27 (26-28) Total 55 (53-56). CG Items 1-10: 26 (24-28) Item 11-20: CG= 27 (25-28) Total 53 (49-56) |

- ISVS-21: Mean (SD)* IG= 0.72 (0.81) CG= 0.64 (1.0) - OIPC: Items 1-10 p<0.001 Item 11-20 p<0.001 Total p<0.001 |

Cohen’s d: IG=0.89 CG= 0.61 |

|

| Moore & Campbell (2021) [26] |

- Sharif and Nahas’ Questionnaire Adaptation. - Knowledge questionnaire: 6 items about knowledge (1= low – 5= excellent). |

Welcome and formal consent (5) ER (55) Comfort break and health care plan development, educational session and evaluation (90) |

6 (at least one nursing student) | 50 health science students (8 nursing students) No CG |

None | NP | NP | Knowledge difference of pre-post means for 6 questions values. p ˂ 0.001 |

NC | |

| Gutiérrez-Puertas et al. (2020) [27] |

- GAMEX18: 7 questions Likert scale (1= never – 5= always). - Scale for level of satisfaction: scores between 13-52, higher scores indicate higher satisfaction. - Practical examination of clinical skill: 10 questions (0, 0.25, 0.5, or 1 point) |

ER (30) | 5 (5) | 237 nursing students IG= 117 (ER) CG= 120 (OSCE19) |

None | NP | Examination of clinical skills IG= 9.59 (0.36) CG= 7.46 (1.36) |

Post p˂0.05 Mann-Whitney U |

NC | Results of GAMEX 6 dimentions Mean (SD): - Enjoyment 27.60 (3.02) (range 6-30) - Absorption 22.74 (4.88) (range 6-30) - Creative thinking 15.55 (3.23) (range 4-20) - Activation 16.09 (2.98) (range 4-20) - Absence of negative effects 4.66 (2.32) (range 3-15) - Dominance 13.52 (3.12) (range 4-20) |

| Morrel & Eukel (2020) [28] |

Knowledge questionarie: - Pre: 10 questions - Post: Same question + perception scale (11 item) |

ER (60) | 4 (4) | 31 nursing students No CG |

2 lost |

NP | NP | p˂0.05 | NC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).