Submitted:

23 January 2024

Posted:

24 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Community Partners

2.2. Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

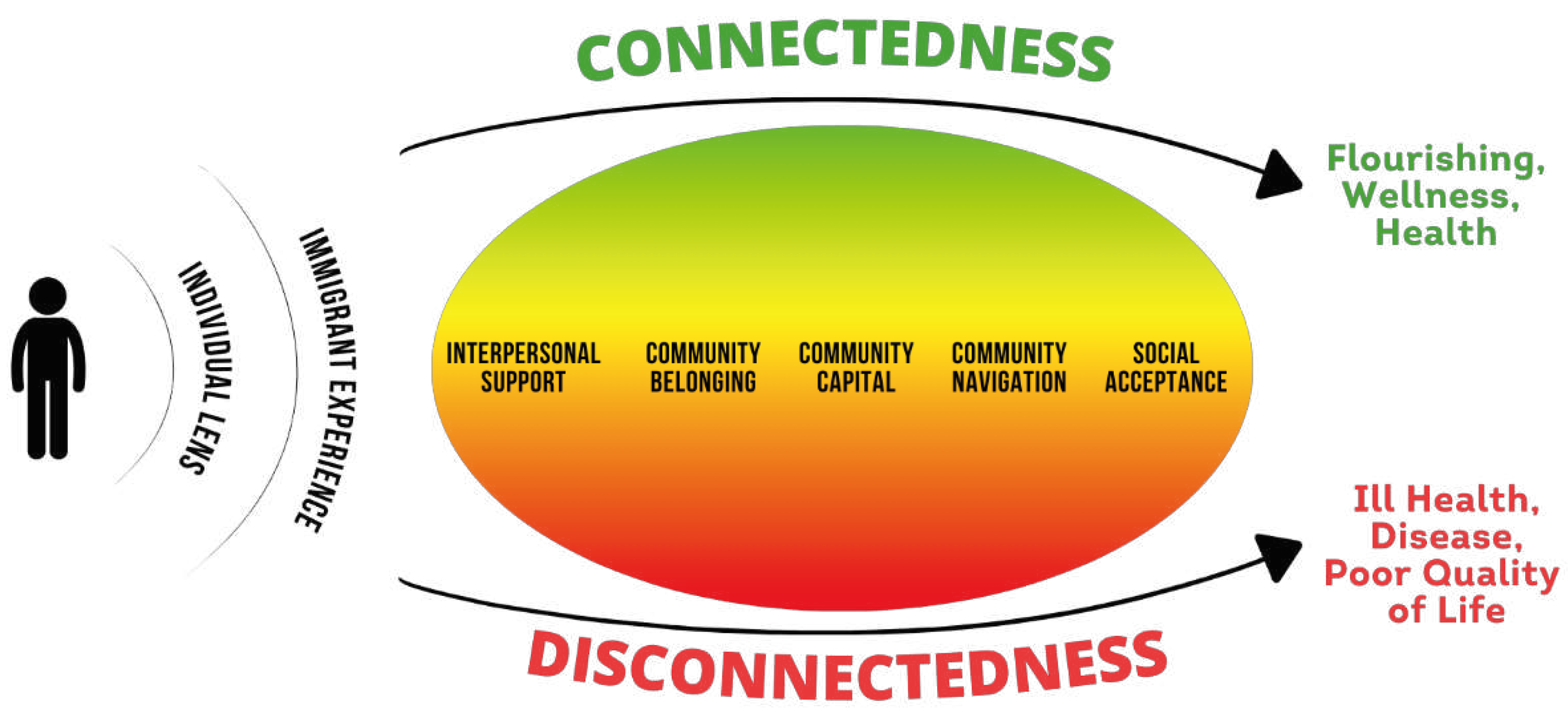

3.1. Lens of the individual

3.2. Immigrant experience

3.3. Interpersonal support

3.4. Community belonging

3.5. Community capital

There was a library close to my work. It was a divine library and the biggest one. I really enjoyed being there. I would be tired or hungry but I would use the computer there to communicate with my family. I’d use the library to take classes, learn how to read in English. I would take classes and then I knew more people that I related to more. I started to feel that warmth of human connection.

3.6. Community navigation

To ask for a service, you have to jump around. I call one place which gives me another phone number for another place and then to another place, and another place, and another place. And if you don’t speak English, just forget it! You have to call with someone who can speak English or who can help support you there. The first answer you are going to get is that you have to stay in line and then they ask you for an email. To get the resource you have to have an email address. So, I consider myself extremely fortunate that I can give an email address and that I can find that help but not all Latinos have that capability.

In Cincinnati, there are groups of different races and other groups that are superior. It makes me feel less for being Latina. It’s something that has happened to me ... especially when I go to events alone and I’m the only Latino, I feel that I’m not the same. But when I am in my community, I feel the same as everyone I feel included. When I go to other events, I feel different, like I’m not supposed to be there.

3.7. Social acceptance

| Domain | Example Quotations (Translated to English) |

|---|---|

| Lens of the individual |

“Well yes of course someone can get out of hard situations. Someone has to fight for it and to stay positive to be able to get up after a negative situation.” “The thing is that I try not to bother other people and I cover my own necessities…so I don’t have to sit there and ask over and over again for help. That’s not me.” “If you put your mind to it…we can achieve anything. I think the barriers we have are put on by ourselves.” |

| Immigrant experience |

“You identify yourself in the place where you are but there is a lot I do not know…one is always waiting to answer the question of “is this my place?”” “It’s hard for Hispanics to communicate in a purely American environment. If I knew English, I would communicate more with my American neighbors. I can’t really have a strong relationship with Americans because of the language barrier.” “As Hispanics, we are a little afraid as many of us don’t have documents or can’t work here legally. Not all Hispanics feel supported.” |

| Interpersonal support |

“Happiness, we try to establish it, not just by focusing on work and getting home but taking time as a family, having dinner together, talking about how our day went. We try as a family to be more united.” “Social media, I use it in a good way to talk to my family, although it’s not the same as talking face to face, but they have helped me a lot and my friends have helped too…I have 2 group chats and we talk there and give each other advice.” “I am retired. So, when you’re retired your circles shrink…volunteering permits me to meet other people of all kinds with whom I did not have connections with before. We would have never crossed each other’s paths so it’s a very enriching experience.” |

| Community belonging |

“In places like where we play soccer everyone gets together…doing some kind of celebration like a birthday celebration, the networks are there and they are connected and they do trust each other.” “Some don’t like immigrants in their country but here in Cincinnati, we have had a very good welcome and there are many people who have welcomed us with open arms who are willing to help us and that makes us happy. It makes us feel good. I can’t imagine feeling rejection because it brings negative emotions or the emotions that make us feel bad and make us sick.” “I feel connected more to the community in Cincinnati. The community in Indiana is a very separate community. Everyone is in their own world, people are just with their work, people are with their families. But I don’t feel connected to any one of them.” |

| Community capital |

“I think social support is when someone is connected with a place or institution that one trusts…there isn’t one place that can help with everything, but this place of trust could refer one to other resources.” “I use Facebook because here in the United Stated they use this app a lot to find information like marketplace to buy things and I also use it because I can see cultural events and family events that are happening nearby. Or if there is a park nearby to take my son.” “23 years ago, there was nothing…it was very, very difficult, but nowadays there is a lot of help and I know that there are people who benefit…Even if you don’t speak the language, there’s always someone to advise or guide you.” |

| Community navigation | “This community is very welcoming not that everyone will open doors to others, not physically, but they at least guide them to where they need to be.” “I think it’s all the same unknowns and search for a center – an area where someone can say, this is an area for Latinos so they can live without fear, for people who don’t know how to communicate, to help find information such as how to get help either to get a job or find housing.” " I could not get any communication with anyone about where they would recommend for us to go. It is very difficult to be in this country to provide for our kids to take our kids to the doctor. It’s very hard to get medical help when we are sick." |

| Social acceptance |

“Normally, when I deal with Latinos, they tell me the same thing. That they are alone and that they don’t feel included or accepted. More than anything they don’t feel accepted. I think it depends a lot on – economically, the less your finances are, the less accepted you are. The better your finances are, you will be a little more accepted. And it also has to do with physical features and what country you are from. Because every country has different treatment in Latin America. Some worse than others.” “I have friends that suddenly feel that others look at them differently because they’re Latina, but it has never happened to me…here if you go to the supermarket people are respectful and say good morning and thank you. I think that is a part of being accepted and seen in a good way and that you feel that you are part of a society.” “I think that one can feel accepted here is when one learns how to live here, respect the laws here and learn the differences of how others live. We need to learn that Americans have another way of living and accept and respect that. One needs to try to communicate in English and acculturate.” |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Batalova J, Hanna M, Levesque C. Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. Secondary Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States 2021. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states-2020.

- Budiman A. Key Findings about U.S. Immigrants. Secondary Key Findings about U.S. Immigrants 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/.

- Singer A. Contemporary immigrant gateways in historical perspective. Daedalus 2013;142(3):76-91. [CrossRef]

- Ellis M, Wright R, Townley M. The allure of new immigrant destinations and the Great Recession in the United States. Int Migr Rev 2014;48(1):3-33. [CrossRef]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Secondary National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report 2014. https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr14/2014nhqdr.pdf.

- Alegría M, Álvarez K, DiMarzio K. Immigration and mental health. Current Epidemiology Reports 2017;4(2):145-55.

- Appel HB, Nguyen PD. Eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in behavioral health care in the US. Journal of Health and Social Sciences 2020;5(4):441-48. [CrossRef]

- Chang CD. Social determinants of health and health disparities among immigrants and their children. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 2019;49(1):23-30. [CrossRef]

- Njeru JW, Tan EM, St Sauver J, et al. High rates of diabetes mellitus, pre-diabetes and obesity among Somali immigrants and refugees in Minnesota: a retrospective chart review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2016;18(6):1343-49. [CrossRef]

- Commodore-Mensah Y, Himmelfarb CD, Agyemang C, Sumner AE. Cardiometabolic health in African immigrants to the United States: a call to re-examine research on African-descent populations. Ethnicity & Disease 2015;25(3):373. [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Mondragon E, Jimenez A, Palladino-Davis AG, Davis D, Escamilla-Cejudo JA. Hispanic health in the USA: a scoping review of the literature. Public Health Reviews 2016;37(1):1-27. [CrossRef]

- Becerra D, Hernandez G, Porchas F, Castillo J, Nguyen V, Perez González R. Immigration policies and mental health: Examining the relationship between immigration enforcement and depression, anxiety, and stress among Latino immigrants. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work 2020;29(1-3):43-59. [CrossRef]

- Morey BN. Mechanisms by which anti-immigrant stigma exacerbates racial/ethnic health disparities. American Journal of Public Health 2018;108(4):460-63. [CrossRef]

- Bekteshi V, Kang S-w. Contextualizing acculturative stress among Latino immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Ethnicity & Health 2020;25(6):897-914. [CrossRef]

- Rumbaut RG. Assimilation of immigrants. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences 2015;2:81-87. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Mental health disparities: Hispanics and Latinos. Secondary Mental health disparities: Hispanics and Latinos 2017. https://www.psychiatry.org.

- Mays VM, Jones A, Delany-Brumsey A, Coles C, Cochran SD. Perceived discrimination in healthcare and mental health/substance abuse treatment among blacks, latinos, and whites. Medical Care 2017;55(2):173. [CrossRef]

- Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Hiripi E, et al. The prevalence of treated and untreated mental disorders in five countries. Health Affairs 2003;22(3):122-33. [CrossRef]

- Morales J, Glantz N, Larez A, et al. Understanding the impact of five major determinants of health (genetics, biology, behavior, psychology, society/environment) on type 2 diabetes in US Hispanic/Latino families: Mil Familias-a cohort study. BMC Endocrine Disorders 2020;20(1):1-13.

- Sarría-Santamera A, Hijas-Gómez AI, Carmona R, Gimeno-Feliú LA. A systematic review of the use of health services by immigrants and native populations. Public Health Reviews 2016;37(1):1-29. [CrossRef]

- Ku L, Jewers M. Health care for immigrant families. Washington, DC: National Center on Immigrant Integration Policy 2013.

- Hacker K, Anies M, Folb BL, Zallman L. Barriers to health care for undocumented immigrants: a literature review. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2015:175-83. [CrossRef]

- Szaflarski M, Bauldry S. The effects of perceived discrimination on immigrant and refugee physical and mental health. Immigration and health: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2019:173-204. [CrossRef]

- Omenka OI, Watson DP, Hendrie HC. Understanding the healthcare experiences and needs of African immigrants in the United States: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Lauderdale DS, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Kandula NR. Immigrant perceptions of discrimination in health care: the California Health Interview Survey 2003. Medical Care 2006:914-20. [CrossRef]

- Castañeda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, Young M-ED, Beyeler N, Quesada J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health 2015;36:375-92. [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological models of human development. In: Gauvain M, Cole M, eds. Readings on the development of children, 2nd ed, 1993:37-43.

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist 1977;32(7):513. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, 2022.

- Golden SD, Earp JAL. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Education & Behavior 2012;39(3):364-72. [CrossRef]

- Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American journal of health promotion 1996;10(4):282-98. [CrossRef]

- Stokols D, Lejano RP, Hipp J. Enhancing the resilience of human–environment systems: A social ecological perspective. Ecology and Society 2013;18(1). [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez DX, Hill J, McDaniel PN. A scoping review of literature about mental health and well-being among immigrant communities in the United States. Health promotion practice 2021;22(2):181-92. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Hong J, Zhou Y, Robles G. The relationships between loneliness, social support, and resilience among Latinx immigrants in the United States. Clinical Social Work Journal 2020;48:99-109. [CrossRef]

- Friedman AS, Venkataramani AS. Chilling effects: US immigration enforcement and health care seeking among Hispanic adults: Study examines the effects of US immigration enforcement and health care seeking among Hispanic adults. Health Affairs 2021;40(7):1056-65. [CrossRef]

- Calvo R, Hawkins SS. Disparities in quality of healthcare of children from immigrant families in the US. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2015;19:2223-32. [CrossRef]

- Finch BK, Vega WA. Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health 2003;5(3):109-17. [CrossRef]

- Kim J. Neighborhood disadvantage and mental health: The role of neighborhood disorder and social relationships. Social Science Research 2010;39(2):260-71. [CrossRef]

- Umberson D, Karas Montez J. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2010;51(1_suppl):S54-S66. [CrossRef]

- Campos B, Schetter CD, Abdou CM, Hobel CJ, Glynn LM, Sandman CA. Familialism, social support, and stress: positive implications for pregnant Latinas. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 2008;14(2):155. [CrossRef]

- Puyat JH. Is the influence of social support on mental health the same for immigrants and non-immigrants? Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2013;15(3):598-605.

- Sanchez M, Diez S, Fava NM, et al. Immigration stress among recent latino immigrants: The protective role of social support and religious social capital. Social Work in Public Health 2019;34(4):279-92. [CrossRef]

- Bulut E, Gayman MD. A latent class analysis of acculturation and depressive symptoms among Latino immigrants: Examining the role of social support. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 2020;76:13-25. [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney-Day NE, Alegria M, Sribney W. Social cohesion, social support, and health among Latinos in the United States. Social Science & Medicine 2007;64(2):477-95. [CrossRef]

- Ki E-J, Jang J. Social support and mental health: An analysis of online support forums for Asian immigrant women. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication 2018;28(2):226-50. [CrossRef]

- Leong F, Park YS, Kalibatseva Z. Disentangling immigrant status in mental health: Psychological protective and risk factors among Latino and Asian American immigrants. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 2013;83(2pt3):361-71. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz JM, Hamann HA, Mehl MR, O’Connor M-F. The Hispanic health paradox: From epidemiological phenomenon to contribution opportunities for psychological science. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2016;19(4):462-76. [CrossRef]

- Johnson CM, Rostila M, Svensson AC, Engström K. The role of social capital in explaining mental health inequalities between immigrants and Swedish-born: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017;17(1):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Garcia D, Simoni JM, Alegría M, Takeuchi DT. Social capital, acculturation, mental health, and perceived access to services among Mexican American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2012;80(2):177. [CrossRef]

- Georgiades K, Boyle MH, Fife KA. Emotional and behavioral problems among adolescent students: The role of immigrant, racial/ethnic congruence and belongingness in schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2013;42(9):1473-92. [CrossRef]

- Salami B, Salma J, Hegadoren K, Meherali S, Kolawole T, Díaz E. Sense of community belonging among immigrants: perspective of immigrant service providers. Public Health 2019;167:28-33. [CrossRef]

- Shah S, Choi M, Miller M, Halgunseth LC, van Schaik SD, Brenick A. Family cohesion and school belongingness: Protective factors for immigrant youth against bias-based bullying. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hong S, Zhang W, Walton E. Neighborhoods and mental health: Exploring ethnic density, poverty, and social cohesion among Asian Americans and Latinos. Social Science & Medicine 2014;111:117-24. [CrossRef]

- Misra S, Wyatt LC, Wong JA, et al. Determinants of depression risk among three Asian American subgroups in New York City. Ethnicity & Disease 2020;30(4):553. [CrossRef]

- Ortega AN, Rodriguez HP, Bustamante AV. Policy dilemmas in Latino health care and implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Annual Review of Public Health 2015;36:525. [CrossRef]

- Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies and PolicyLink. Community-based strategies for improving Latino health. Available at. Secondary Community-based strategies for improving Latino health. Available at 2004. http://www.policylink.org/sites/default/files/COMM-BASEDSTRATEGIES-LATINOHEALTH_FINAL.PDF.

- Kandel W, Parrado EA. New Hispanic migrant destinations. A tale of two industries. In: Massey DS, ed. New faces in new places : the changing geography of American immigration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2005.

- Lichter DT, Johnson KM. Emerging rural settlement patterns and the geographic redistribution of America's new immigrants. Rural Sociology 2006;71(1):109-31. [CrossRef]

- Odem ME. Immigration and Ethnic Diversity in the South, 1980–2010. The Oxford Handbook of American Immigration and Ethnicity 2016:355.

- Crowley M, Lichter DT, Turner RN. Diverging fortunes? Economic well-being of Latinos and African Americans in new rural destinations. Social Science Research 2015;51:77-92. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin-Alvarado J, DeSipio L, Montoya C. Latino Mobilization in New Immigrant Destinations The Anti—HR 4437 Protest in Nebraska's Cities. Urban Affairs Review 2009;44(5):718-35. [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Hispanic Population Growth and Dispersion Across U.S. Counties, 1980-2014. Secondary Hispanic Population Growth and Dispersion Across U.S. Counties, 1980-2014 2021. http://www.pewhispanic.org/interactives/hispanic-population-by-county/.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File. Secondary Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File 2021. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/technical-documentation/complete-tech-docs/summary-file/2020Census_PL94_171Redistricting_StatesTechDoc_English.pdf.

- Waters MC, Jiménez TR. Assessing immigrant assimilation: New empirical and theoretical challenges. Annual Review of Sociology 2005;31:105-25. [CrossRef]

- Eiler BA, Bologna DA, Vaughn LM, Jacquez F. A social network approach to understanding community partnerships in a nontraditional destination for Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology 2017;45(2):178-92. [CrossRef]

- Jacquez F, Vaughn LM, Pelley T, Topmiller M. Healthcare experiences of Latinos in a nontraditional destination area. Journal of Community Practice 2015;23(1):76-101. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Gao Y, Han Z, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 90 cohort studies of social isolation, loneliness and mortality. Nature Human Behaviour 2023:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Murthy VH. Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: the U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community, 2023.

- Grzywacz JG, Fuqua J. The social ecology of health: Leverage points and linkages. Behavioral medicine 2000;26(3):101-15. [CrossRef]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006;3(2):77-101. [CrossRef]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: A practical guide: Sage, 2022.

- Campbell KA, Orr E, Durepos P, et al. Reflexive thematic analysis for applied qualitative health research. The Qualitative Report 2021;26(6):2011-28. [CrossRef]

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2006;5(1):80-92. [CrossRef]

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2017;16(1):1609406917733847. [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot K. Inductive/deductive hybrid thematic analysis in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 2023;17(3):308-26. [CrossRef]

- Swain J. A hybrid approach to thematic analysis in qualitative research: Using a practical example. London, 2018.

- Jacquez F, Vaughn, L, Zhen-Duan, J, & Graham, C,. Healthcare utilization and barriers to care among Latino immigrants in a new migration area. Journal of Healthcare for the Poor & Underserved 2016;27:1759–76. [CrossRef]

- Jacquez F, Vaughn LM, Suarez-Cano G. Implementation of a stress intervention with Latino immigrants in a non-traditional migration city. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2019;21(2):372-82. [CrossRef]

- Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Marschner D, McLinden D. See what we say: using concept mapping to visualize Latino immigrant’s strategies for health interventions. International Journal of Public Health 2016;61(7):837-45. [CrossRef]

- Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Suarez-Cano G. Developing and implementing a stress and coping intervention in partnership with Latino immigrant coresearchers. Translational Issues in Psychological Science 2019;5(1):62. [CrossRef]

- Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Zhen-Duan J, et al. Latinos Unidos por la Salud: The process of developing an immigrant community research team. Collaborations: A Journal of Community-Based Research and Practice 2017;1(1):2. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic or Latino (of any race) in Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN Metro Area. Secondary Hispanic or Latino (of any race) in Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN Metro Area 2021. https://data.census.gov/all?t=Hispanic+or+Latino&g=310XX00US17140&y=2020.

- Kissam E. Differential undercount of Mexican immigrant families in the US Census. Statistical Journal of the IAOS 2017;33(3):797-816. [CrossRef]

- Riffe HA, Turner S, Rojas-Guyler L. The diverse faces of Latinos in the Midwest: Planning for service delivery and building community. Health & Social Work 2008;33(2):101-10. [CrossRef]

- Topmiller M, Zhen-Duan J, Jacquez FJ, Vaughn LM. Place matters in non-traditional migration areas: Exploring barriers to healthcare for Latino immigrants by region, neighborhood, and community health center. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2017;4(6):1214-23. [CrossRef]

- Etikan I, Alkassim R, Abubakar S. Comparision of snowball sampling and sequential sampling technique. Biometrics and Biostatistics International Journal 2016;3(1):55. [CrossRef]

- Parker C, Scott S, Geddes A. Snowball sampling. SAGE research methods foundations 2019.

- DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Family Medicine and Community Health 2019;7(2). [CrossRef]

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity 2018;52(4):1893-907. [CrossRef]

- Morse JM. Data were saturated: Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, 2015:587-88.

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2021.

- VanderWeele TJ. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017;114(31):8148-56. [CrossRef]

- Smith ML, Racoosin J, Wilkerson R, et al. Societal-and community-level strategies to improve social connectedness among older adults. Frontiers in Public Health 2023;11:1176895. [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: A systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annual Review of Pychology 2018;69:437-58. [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Robles TF, Sbarra DA. Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American Psychologist 2017;72(6):517. [CrossRef]

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Echeverría SE, Flórez KR. Latino immigrants, acculturation, and health: Promising new directions in research. Annual Review of Public Health 2016;37:219-36. [CrossRef]

- Ornelas IJ, Yamanis TJ, Ruiz RA. The health of undocumented Latinx immigrants: What we know and future directions. Annual Review of Public Health 2020;41:289-308. [CrossRef]

- Garcini L, Chen N, Cantu E, et al. Protective factors to the wellbeing of undocumented Latinx immigrants in the United States: A socio-ecological approach. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 2021;19(4):456-71. [CrossRef]

- Bostean G, Andrade FCD, Viruell-Fuentes EA. Neighborhood stressors and psychological distress among US Latinos: Measuring the protective effects of social support from family and friends. Stress and Health 2019;35(2):115-26. [CrossRef]

- Lazarevic V, Crovetto F, Shapiro AF, Nguyen S. Family dynamics moderate the impact of discrimination on wellbeing for Latino young adults. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 2021;27(2):214. [CrossRef]

- Yang YC, Boen C, Gerken K, Li T, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016;113(3):578-83. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch JL, Clark MS. Multiple paths to belonging that we should study together. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2019;14(2):238-55. [CrossRef]

- Van Lange PA, Columbus S. Vitamin S: Why is social contact, even with strangers, so important to well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science 2021;30(3):267-73. [CrossRef]

- Balaghi D. The role of ethnic enclaves in Arab American Muslim adolescent perceived discrimination. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 2023;33(3):551-70. [CrossRef]

- Eschbach K, Ostir GV, Patel KV, Markides KS, Goodwin JS. Neighborhood context and mortality among older Mexican Americans: is there a barrio advantage? American Journal of Public Health 2004;94(10):1807-12. [CrossRef]

- Vega WA, Ang A, Rodriguez MA, Finch BK. Neighborhood protective effects on depression in Latinos. American Journal of Community Psychology 2011;47:114-26. [CrossRef]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Morenoff JD, Williams DR, House JS. Contextualizing nativity status, Latino social ties, and ethnic enclaves: an examination of the ‘immigrant social ties hypothesis’. Ethnicity & Health 2013;18(6):586-609. [CrossRef]

- Williams AD, Messer LC, Kanner J, Ha S, Grantz KL, Mendola P. Ethnic enclaves and pregnancy and behavior outcomes among Asian/Pacific Islanders in the USA. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2020;7:224-33. [CrossRef]

- Kearns A, Whitley E, Tannahill C, Ellaway A. Loneliness, social relations and health and well-being in deprived communities. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2015;20(3):332-44. [CrossRef]

- Documet PI, Troyer MM, Macia L. Social support, health, and health care access among Latino immigrant men in an emerging community. Health Education & Behavior 2019;46(1):137-45. [CrossRef]

- Williams DR. Stress and the mental health of populations of color: Advancing our understanding of race-related stressors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2018;59(4):466-85. [CrossRef]

- Fagundes CP, Bennett JM, Derry HM, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Relationships and inflammation across the lifespan: Social developmental pathways to disease. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2011;5(11):891-903. [CrossRef]

- Hawkley LC, Capitanio JP. Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: a lifespan approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2015;370(1669):20140114. [CrossRef]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Interpersonal Development 2017:57-89.

- Ma J, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Sunderland M. The development and validation of the Thwarted Belongingness Scale (TBS) for interpersonal suicide risk. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2019;41:456-69. [CrossRef]

- Checa I, Oberst U. Measuring belongingness: Validation and invariance of the general belongingness scale in Spanish adults. Current Psychology 2022;41(12):8490-98. [CrossRef]

- Baxter T, Shenoy S, Lee H-S, Griffith T, Rivas-Baxter A, Park S. Unequal outcomes: The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and wellbeing among Hispanic/Latinos with varying degrees of ‘Belonging’. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2023;69(4):853-64. [CrossRef]

- Hagerty BM, Lynch-Sauer J, Patusky KL, Bouwsema M, Collier P. Sense of belonging: A vital mental health concept. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 1992;6(3):172-77. [CrossRef]

- Hale CJ, Hannum JW, Espelage DL. Social support and physical health: The importance of belonging. Journal of American College Health 2005;53(6):276-84. [CrossRef]

- Moore S, Kawachi I. Twenty years of social capital and health research: a glossary. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2017;71(5):513-17. [CrossRef]

- Ehsan A, Klaas HS, Bastianen A, Spini D. Social capital and health: A systematic review of systematic reviews. SSM-population health 2019;8:100425. [CrossRef]

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community: Simon and schuster, 2000.

- Aldrich DP, Meyer MA. Social capital and community resilience. American Behavioral Scientist 2015;59(2):254-69. [CrossRef]

- Cattell V. Poor people, poor places, and poor health: the mediating role of social networks and social capital. Social Science & Medicine 2001;52(10):1501-16. [CrossRef]

- Richter NL, Gorey KM, Haji-Jama S, Luginaah IN. Care and survival of Mexican American women with node negative breast cancer: Historical cohort evidence of health insurance and barrio advantages. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2015;17:652-59. [CrossRef]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist 2004;59(8):676.

- Johnson CM, Sharkey JR, Dean WR, St John JA, Castillo M. Promotoras as research partners to engage health disparity communities. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2013;113(5):638.

- Ruiz-Sánchez HC, Macia L, Boyzo R, Documet PI. Community health workers promote perceived social support among Latino men: Respaldo. Journal of Migration and Health 2021;4:100075. [CrossRef]

- Arce MA, Kumar JL, Kuperminc GP, Roche KM. “Tenemos que ser la voz”: Exploring resilience among Latina/o immigrant families in the context of restrictive immigration policies and practices. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 2020;79:106-20. [CrossRef]

- Rabin J, Stough C, Dutt A, Jacquez F. Anti-immigration policies of the trump administration: A review of Latinx mental health and resilience in the face of structural violence. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 2022;22(3):876-905. [CrossRef]

- Newell CJ, South J. Participating in community research: exploring the experiences of lay researchers in Bradford. Community, Work & Family 2009;12(1):75-89. [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristic | Frequency | Percent |

| Country of Origin Guatemala Mexico Venezuela Colombia Honduras El Salvador Dominican Republic Ecuador Panama |

11 9 9 2 2 2 1 1 1 |

29% 24% 24% 5% 5% 5% 3% 3% 3% |

| Current Location Ohio Kentucky Indiana |

29 8 1 |

76 21 3 |

| Children Yes No Not Reported |

24 8 6 |

63 21 16 |

| Age 18-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 61-71 Not Reported |

11 13 7 3 3 1 |

29 34 18 8 8 3 |

| Years Living in USA Less than 1 year 1 year 2-10 years 11-20 years 21-30 years 31-40 years |

4 6 11 7 5 2 |

11 16 29 18 13 5 |

| Gender Female Male |

22 16 |

58 42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).