Introduction

Violence against Paramedics

Violence is widely recognized as a serious occupational health issue affecting paramedics, with the potential for significant physical and psychological harm [

1]. For example, data from the United States (US) Bureau of Labor Statistics illustrates that paramedics experience a risk of injury from violence 6 times greater than the US population and 60% greater than comparable health professions [

2]. When surveyed, a concerning majority of paramedics indicate having experienced various forms of violence - including physical and sexual assault - within the past year or throughout their careers [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The research parallels growing reports in the media of paramedics being seriously injured (and sometimes killed) after violent attacks by members of the public [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. While sentinel events tend to be documented in injury statistics or press coverage, they occur against a backdrop of pervasive institutional underreporting [

1,

17,

18]. For example, when Bigham and colleagues surveyed paramedics from two Canadian provinces, despite more than 75% of participants indicating past-year exposure to violence, less than 20% documented the incidents or reported the encounters to police or supervisors [

3].

Underreporting

In an earlier study, we identified that the organizational culture within paramedicine appears to sustain norms that limit reporting by implicitly positioning the ability of paramedics to ‘brush off’ incidents of violence as an expected professional competency [

18]. Within this construction, while injurious encounters may be documented, incidents perceived as less serious - but more prevalent - are seen as unpreventable and (hence) ‘not worth’ reporting [

18]. Underreporting has been highlighted in the literature as a significant problem [

17], one that severely limits researchers’ and policymakers’ understanding of both the scope and type of violence that paramedics experience in their work.

Non-Physical Violence

Although violence against paramedics can (and often does) take the form of physical or sexual assault, pervasive underreporting means that non-physical violence, such as threats, harassment, and verbal abuse may be even more prevalent. Returning here to Bigham and colleagues’ 2014 survey, 14% of participants indicated they had been sexually harassed, 41% had been threatened, and 67% had been subjected to verbal abuse in the past year [

3]. Even absent a physical assault, verbal abuse can be distressing in its own right, especially if the abuse targets personal or cultural identities, such as race, gender, or sexual orientation. Previous research among healthcare workers has identified that harassment from patients on these grounds contributes to insomnia, depression, anxiety, burnout, attrition from health care, and suicide [

19,

20] - problems that have increased since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic [

21,

22,

23,

24]. There is, then, a compelling need to study and respond to all forms of violence against paramedics, particularly those that are the least likely to be documented or reported.

The External Violence Incident Report

Our team developed a novel violence reporting process intended to overcome many of the administrative and organizational cultural barriers to reporting violence against paramedics. While the specifics have been reported in an earlier publication [

25], in brief, the External Violence Incident Report (EVIR) was derived through an extensive stakeholder consultation and pilot testing process. The form is embedded in the electronic Patient Care Record (ePCR) and is designed to capture comprehensive quantitative and qualitative data about violent encounters at the time of event, as documented by the affected paramedic(s). Particularly relevant for this study, the form contains a free text box where paramedics can type a detailed description of violent incidents without any restrictions on length.

Qualitatively analyzing the free-text narrative descriptions of violent encounters may offer unique insight into the nature of the violence paramedics encounter in their work, including potential abuse on identity grounds such as race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. Therefore, our objectives were to (1) estimate the prevalence of (potentially) hate-motivated violence against paramedics, including sexism, misogyny, racism, and homophobia; and (2) assess the differential impact of hate-motivated violence on self-reported emotional distress.

Methods

Overview and Setting

This study is part of a broader research program, with a detailed description of the approach provided in an earlier publication [

26]. For this study, we analyzed the free-text narrative descriptions of violent encounters documented in a one-year subset of EVIRs following the introduction of the new reporting process.

Our research is situated in the Region of Peel in Ontario, Canada. Peel Regional Paramedic Services (PRPS) is the sole provider of publicly funded land ambulance and paramedic services to the municipalities of Brampton, Mississauga, and Caledon. PRPS employs approximately 750 primary and advanced care paramedics and 60 members in various leadership or administrative capacities who also maintain certification to practice. The service provides coverage to a mixed urban and rural geography of 1,200km2 with a population of 1.38 million residents, responding to approximately 130,000 emergency calls per year. This positions the service as the second largest in the province by staffing and caseload.

The introduction of the EVIR occurred as part of a broader violence prevention program within the service that included crisis prevention and de-escalation training, new patient restraint equipment, revised safety procedures, and a public position statement of ‘zero tolerance’ for violence against paramedics.

Data Collection

The EVIR (available as

supplementary material) is a web-based form embedded in the electronic patient care record alongside other documentation and includes a free-text box where paramedics can document a detailed narrative description of the violent encounter. The form imposes no word or character limit and paramedics are encouraged to be both detailed and specific, incorporating the use of direct quotes where possible. When completing an EVIR, the documenting paramedic can also indicate whether they were physically harmed or ‘emotionally impacted’ (or both) at the time of reporting.

Provincial documentation standards require paramedics to complete an Ambulance Call Report (ACR) after every patient encounter and additionally require paramedics to complete an incident report in unusual circumstances. The EVIR is considered an incident report under these standards, and service policy instructs paramedics to complete an EVIR if they experienced verbal abuse, threats, sexual harassment, or physical or sexual assault during a call. Paramedics are additionally reminded to complete an EVIR when filing an ACR if they experienced violence during the call.

Our study window included a thirteen-month period following the introduction of the EVIR from February 1, 2021, through February 28, 2022. We included all violence reports filed during this period unless the documenting paramedic ‘opted out’ of secondary use of the form for research purposes.

Measures and Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the proportion of EVIRs that described violence (particularly verbal abuse) with racist, homophobic, sexist, or misogynistic connotations based on the description provided by the documenting paramedic. The Ontario Human Rights Code explains that all persons are protected under law from discrimination or harassment on the basis of several

protected grounds, including sexual orientation, gender identity or expression; race and related grounds, among others [

27]. In addition, occupational health and safety legislation in Ontario protects workers (including paramedics) from harassment, defined in the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA) as “engaging in a course of vexatious comment or conduct against a worker in a workplace that is known or ought reasonably to be known to be unwelcome” [

28]. The purviews of both the Ontario Human Rights Code and the OHSA overlap, particularly in employment contexts, and we used both pieces of legislation as orienting concepts for identifying potentially hate-motivated violence in the EVIRs. Where the EVIR included hateful or offensive language, we referenced the wiki-style website

www.urbandictionary.com to source definitions of the word grounded in contemporary usage to assess whether it could reasonably be construed as sexist or racist (for example). Importantly, EVIRs do not collect demographic information about the documenting paramedic, meaning that our assessment of sexism (for example) was focused specifically on the language itself rather than the degree to which the abuse was personally targeted.

Our secondary outcome was self-reported emotional distress, as documented by the reporting paramedic. The EVIR asks paramedics to indicate whether they are emotionally impacted at the time of the event, with response options for ‘yes’, ‘no’, and ‘I’m uncertain’. We considered ‘yes’ a positive screen for emotional distress.

Analysis

We analyzed our data two ways: first, we decoupled the free-text narrative descriptions of violent encounters from all EVIRs included in the study and subjected the narratives to a structured form of qualitative content analysis [

29]. For this task, we recruited two paramedic-supervisors with knowledge of the violence prevention project and the relevant legislation to code each narrative in response to the prompt ‘does the narrative suggest violence on the basis of gender, sexual orientation, or race/ethnicity?’ Following an initial period of calibration where the two investigators coded a sample of 15 EVIRs with the principal investigator, the remaining narratives were coded independently. We then calculated interrater agreement using a Kappa statistic and met as a group to resolve discrepant cases through consensus. For our secondary objective, we used chi square tests to assess group differences in self-reported emotional distress between hate-motivated vs. non-hate motivated violence. All analyses were completed in SPSS Statistics (IBM Corporation; version 28) and we followed convention in accepting a p-value of <0.05 with confidence intervals that exclude the null value to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Note to Readers

Our results include descriptions of sexist, racist, and homophobic comments that may be upsetting to some readers.

Overview

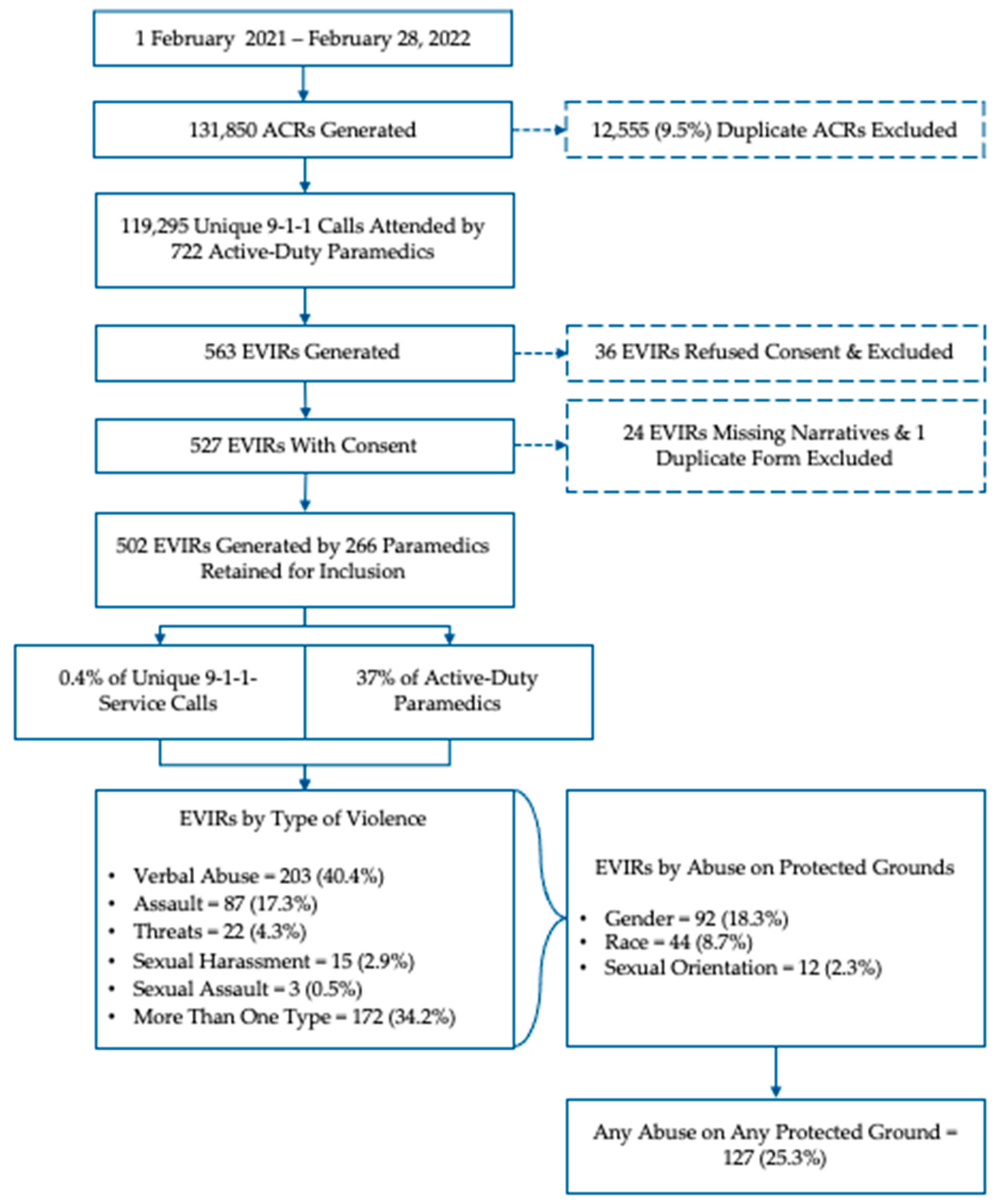

Between February 1, 2021, through February 28, 2022, a total of 722 paramedics in Peel Region responded to 119,295 emergency calls with 563 EVIRs generated. In 36 cases, the documenting paramedics did not consent for use of the form for research and the reports were excluded. A further 24 reports were missing the free-text narrative description and were excluded. Finally, one report was a duplicate of the same incident and was also excluded. This left 502 unique reports filed by a total of 266 paramedics for analysis (see

Figure 1).

Our reviewers achieved substantial inter-rater agreement [

30] for sexual orientation (k=0.73), race (k=0.76), and gender (k=0.83), with violence on the basis of gender having the highest proportion of complete agreement between raters (78%) and race the lowest (65%).

After resolving discrepant cases (

Table 1), 18% of EVIRs were found to describe violence against paramedics on the basis of gender, 9% because of race (or related grounds), and 2% because of sexual orientation, with 25% documenting some form of abuse on any of the three protected grounds. Among paramedics reporting violence on protected identity grounds (N=96), the average number of reports was 1.32 (Standard Deviation [SD] 0.76), with a maximum per-paramedic frequency of six reports. This corresponds to 13% of the active-duty paramedic workforce reporting exposure to harassment on protected identity grounds during the study period.

Impact on Paramedics

Of the 502 reports included in the study, 124 reports (25%) indicated that the documenting paramedic (n=89) was ‘emotionally impacted’ by the incident at the time of reporting. Compared to other types of violence, incidents involving abuse on protected identity grounds were associated with an increased risk of emotional distress (31% vs. 22% of reports, Odds Ratio [OR] 1.59, 95% CI 1.01-2.48, p=0.04).

Discussion

Our objective was to assess the frequency with which paramedics in our setting reported being subjected to sexist, misogynistic, racist, or homophobic abuse in the course of their work over a 13-month period. All told, we found that 1 in 4 reports filed by 96 paramedics documented some form of verbal abuse or harassment on protected identity grounds during the study, corresponding to 13% (≈ 1 in 8) of the active-duty work force. Averaged over the study period, this corresponds to a rate of one report of harassment on protected identity grounds every 3 days.

Given the historical underreporting on this topic, ascertaining the scope and complexity of the problem of violence against paramedics has been challenging. Previous research has tended to rely on either self-report survey methods [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

18,

31,

32] or retrospective reviews of injury statistics databases [

2,

33,

34]. While undeniably valuable, both approaches lack the granularity and specificity afforded by event-level data, and neither approach (to our knowledge) has specifically sought to estimate the prevalence of harassment on identity grounds. In that respect, our findings help to fill an important gap in research by contributing unique insight into the texture of the abuse that paramedics encounter in the course of their work.

The research program to which this study is attached is intended to construct an epidemiological profile of violence against paramedics as an occupational health issue. From a research perspective, however, important questions remain unanswered. For example, future research should seek to quantify the impacts on health and well-being of incidental and recurrent exposure to workplace violence - including the impact of vitriolic verbal abuse and harassment. Using longitudinal or repeated sampling approaches following violent encounters with self-report symptom measures for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and burnout would be a welcome contribution to scholarship in this space, while painting a clearer picture of the potential long-term harms from violence. Future research should also seek to find and evaluate potential risk mitigation strategies, such as flagging individuals with a history of violent behavior or providing de-escalation training to paramedics - both of which have been proposed as potential solutions to this problem [

7,

17,

35,

36,

37]. Finally, researchers should engage paramedics to ascertain what forms of post-incident support they find most useful in mitigating the acute stress likely associated with being exposed to workplace violence. Similar work using qualitative interviews and focus groups of paramedics has been done with good effect to develop supportive interventions after critical incidents, for example [

38,

39].

From a policy perspective, our findings have important implications amid what is increasingly recognized as a health human resource crisis confronting health care broadly. There is now abundant research illustrating that healthcare providers are exposed to high rates of workplace violence and that, during the COVID-19 pandemic in particular, the violence increased [

1,

17,

18]. In recent years, growing political and social divisions fueled by mis- or disinformation on public health measures gave rise to antipathy and hostility toward health care as an institution [

22,

41]. The result has been an increase in the harassment of healthcare workers, both online and in clinical settings [

24], which, in turn, has led to burnout, depression, anxiety, and what has been described as an ‘exodus’ of healthcare workers exiting the professions [

42,

43]. These issues exist in paramedic services as well, with media reports describing staffing shortages and low morale as contributing to increasing wait times for ambulance calls [

44,

45,

46]. In our province, the Ontario Association of Paramedic Chiefs has forecasted a shortage of 400 paramedics per year, a shortfall the provincial government is attempting to address [

47]. Although not the focus of this study, it is reasonable to expect that violence may be a contributing factor to staffing shortages in paramedic services. There are a myriad of recommendations for workplace violence prevention strategies in healthcare settings broadly [

48], but - to our knowledge - no such policy documents designed specifically for the paramedic context. As a health care setting, the out-of-hospital context presents many unique challenges that potentially increase the risk of harm from violence, including limited resources, undifferentiated patients, ready access to weapons, and poorly controlled (or uncontrollable) scene environments, to name but a few. Provincial or national strategies for violence prevention policy alongside robust post-incident support would be a welcome contribution.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted within the context of certain limitations. First, we must acknowledge that the violence reporting process was not intended to document harassment on protected identity grounds. Instead, we relied on the narrative description provided by documenting paramedics, with a particular emphasis on reports that included quotes from the harassers. Although paramedics are encouraged to be specific in their documentation and to include quotes, we nevertheless acknowledge our analysis required a value judgment on the part of our research team as to what constitutes sexist, racist, or homophobic language. Our raters were not racialized individuals themselves. In applying a conservative analytical frame within a context of underreporting, this means the actual frequencies with which paramedics are exposed to this vitriol is likely much higher. Second, our assessment of emotional distress is constrained to a single question on the reporting form answered at the time of the incident. In accepting only “yes” answers and excluding the “I’m uncertain” responses, we were again applying a conservative analytical approach in our estimates. It is also worth noting that emotional distress may well manifest after some time has passed and may be worsened by repeated exposure, as is the case with several of our participants who reported multiple incidents of abuse on protected identity grounds. Again, our assessment of the potential psychological impacts of the abuse is likely underestimating the true degree of harm experienced by the paramedics. Third, as mentioned earlier, the EVIR does not capture detailed demographic information for either perpetrators or the documenting paramedics. This meant that, unless the documenting paramedic specifically provided this information, we were unable to evaluate the directionality or differential targeting of potentially hate-motivated abuse (e.g., misogynistic comments from men towards women); rather, the focus of analysis was on whether the description documented abuse with misogynistic overtones. Finally, we are taking the paramedics’ accounts at face value, without attempting to ascertain the veracity of the claims - although we have no reason to doubt them.

Conclusion

Leveraging a novel, point-of-event incident reporting process in a single paramedic service in Ontario, Canada, we found that 25% of violent encounters involved sexist, misogynistic, racist, or homophobic abuse, ultimately affecting 13% of the active-duty paramedic workforce. Expressed as rates, our findings correspond to paramedics experiencing potentially hate-motivated violence every 3 days. Compared to other forms of violence, harassment on protected identity grounds was associated with an increased risk of self-reported emotional distress at the time of reporting. Our findings offer unique insight into the type of violence experienced by paramedics, but - amid a culture of underreporting - our estimates remain conservative, and both the scope of the problem and potential harm are likely much higher.

Supplementary Materials

The External Violence Incident Report (EVIR) in its entirety is available as supplementary material in Appendix S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JM; methodology, JM; software, JM and MJ; validation, JM and MJ; formal analysis, JM, JD, and NJ; investigation, JM; resources, JM and EAD; data curation, JM; writing - original draft preparation, JM; writing - review and editing, JM, JD, NJ, MJ, AB, and EAD; visualization, JM; supervision, JM and EAD; project administration, JM and MJ; funding acquisition, JM and EAD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was principally funded by the Region of Peel, Department of Health Services, Division of Paramedic Services, as part of the broader violence prevention program. Additional funding was obtained from the University of Windsor. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was paid by the Region of Peel.

Institutional Review Board Statement

this study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (REB protocol number 44162).

Informed Consent Statement

As the data in this study are primarily intended for non-research purposes, the investigation falls under a ‘secondary use of data’ provision in federal standards for research ethics; within this framework, the requirement for fully informed consent does not universally apply if the secondary data being collected do not identify individuals. Recognizing the potentially sensitive nature of the subject matter, we included a mechanism for paramedics to express a preference about the future use of their reports for research purposes. Specifically, paramedics who did not want a particular form used in this study could tick a box indicating “I do not want this form used for research purposes’’. The REB agreed that this opt-out process was sufficient for participant consent. The requirement to obtain consent from patients or other persons described in the EVIRs was waived provided the information was sufficiently de-identified.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study may be shared with interested researchers on a case-by-case basis, subject to a privacy review and formal data sharing agreement.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude and appreciation first and foremost to the paramedics of the Region of Peel for documenting their experiences with violence and agreeing to share their stories with our research team. It is not in vain. We also wish to acknowledge and thank the dedicated members of the Region of Peel’s Strategic Policy and Performance division for their invaluable assistance with data curation; particularly, Michelle Chen and Claudia Mittitelu. Finally, we are grateful to Peter Dundas, Brian Gibson, Tom Kukolic, and Jennifer Chadder of the senior paramedic leadership team for their unwavering support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors JM, JD, NJ, and MJ are employed by the Region of Peel’s paramedic service and received employment income to complete this research as part of the broader violence prevention program within the service.

References

- Maguire, B.J.; O’Neill, B.J. Emergency Medical Service Personnel's Risk From Violence While Serving the Community. Am J Public Health 2017, 107, 1770–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, B.J.; Al Amiry, A.; O’Neill, B.J. Occupational Injuries and Illnesses among Paramedicine Clinicians: Analyses of US Department of Labor Data (2010 - 2020). Prehospital and disaster medicine 2023, 38, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigham, B.; Jensen, J.L.; Tavares, W.; Drennan, I.; Saleem, H.; Dainty, K.N.; Munro, G. Paramedic self-reported exposure to violence in the emergency medical services (EMS) workplace: A mixed-methods cross sectional survey. Prehospital emergency care : official journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors 2014, 18, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, S.W.; Grange, J.T.; Thomas, T.T. Exposure of prehospital care providers to violence. Prehospital emergency care : official journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors 1998, 2, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furin, M.; Eliseo, L.J.; Langlois, B.; Fernandez, W.G.; Mitchell, P.; Dyer, K.S. Self-reported provider safety in an urban emergency medical system. West J Emerg Med 2015, 16, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, M.A.; Crowe, R.P.; Bentley, M.A.; Levine, R. A National Description of Violence toward Emergency Medical Services Personnel. Prehospital emergency care : official journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors 2016, 20, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, B.J.; Browne, M.; O’Neill, B.J.; Dealy, M.T.; Clare, D.; O’Meara, P. International Survey of Violence Against EMS Personnel: Physical Violence Report. Prehospital and disaster medicine 2018, 33, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setlack, J.; Brais, N.; Keough, M.; Johnson, E.A. Workplace violence and psychopathology in paramedics and firefighters: Mediated by posttraumatic cognitions. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement 2021, 53, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suserud, B.O.; Blomquist, M.; Johansson, I. Experiences of threats and violence in the Swedish ambulance service. Accident and Emergency Nursing 2002, 10, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongtongkam, N. An exploration of violence against paramedics, burnout and post-traumatic symptoms in two Australian ambulance services. International Journal of Emergency Services 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambulance staff face rise in physical and verbal sexual assaults. The Guardian, 23 April 2018.

- Brampton man charged after female paramedics sexually assaulted in Peel Region. CBC News, 2023.

- Drewitt-Smith, A.; Fuller, K. NSW paramedic Steven Tougher farewelled at emotional service in Wollongong. ABC News, 2023.

- Kilgannon, C. Slain paramedic, ‘mother of the station, was near retirement. The New York Times, 2022.

- CBC Radio. Threats, abuse, sexual harassment by the public: Paramedics on the dark side of the job. CBC Radio, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Renić, K. Charges laid after paramedic assaulted at Halifax hospital, police say. Global News, 2022.

- Maguire, B.J.; O’Meara, P.; O’Neill, B.J.; Brightwell, R. Violence against emergency medical services personnel: A systematic review of the literature. Am J Ind Med 2018, 61, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mausz, J.; Johnston, M.; Donnelly, E.A. The role of organizational culture in normalizing paramedic exposure to violence. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research 2021, 14, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chary, A.N.; Fofana, M.O.; Kohli, H.S. Racial Discrimination from Patients: Institutional Strategies to Establish Respectful Emergency Department Environments. West J Emerg Med 2021, 22, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltiso, S.O.; Seitz, R.M.; Zdradzinski, M.J.; Moran, T.P.; Heron, S.; Robertson, J.; Lall, M.D. The impact of racism on emergency health care workers. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine 2021, 28, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canpolat, E.K.; Gulacti, U. Changes in violence against healthcare professionals with the COVID-19 pandemic. Disaster and Emergency Medicine Journal 2022, 7, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, H. Navigating attacks against health care workers in the COVID-19 era. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2021, 325, 1822–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzi, Z.S.; Fatah, P.W.; Dalvandi, A. Prevalence of Workplace Violence Against Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 896156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragih, I.D.; Tarihoran, D.; Rasool, A.; Saragih, I.S.; Tzeng, H.M.; Lin, C.J. Global prevalence of stigmatization and violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nurs Scholarsh 2022, 54, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mausz, J.; Johnston, M.; Donnelly, E. Development of a reporting process for violence against paramedics. Canadian Paramedicine 2021, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Mausz, J.; Donnelly, E. Violence against paramedics: Protocol for evaluating one year of reports from a novel, point-of-event reporting process. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Code, R.S.O. 1990, c. H.19. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario. Preventing workplace violence and workplace harassment. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/preventing-workplace-violence-and-workplace-harassment (accessed on January 17).

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and Health Sciences 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemal Medicine (Zagreb) 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.; Reifferscheid, F.; Kerner, T.; Dressler, J.L.; Stuhr, M.; Wenderoth, S.; Petrowski, K. Association between the experience of violence and burnout among paramedics. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2021, 94, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, N.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Okechukwu, C.; Kim, S.S. Organizational response to workplace violence, and its association with depressive symptoms: A nationwide survey of 1966 Korean EMS providers. J Occup Health 2019, 61, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, B.J. Violence against ambulance personnel: a retrospective cohort study of national data from Safe Work Australia. Public Health Res Pract 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, B.J.; Smith, S. Injuries and fatalities among emergency medical technicians and paramedics in the United States. Prehospital and disaster medicine 2013, 28, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D.G., Jr.; DeLuca, M.B.; Crowe, R.P.; Cash, R.E.; Rivard, M.K.; Williams, J.G.; Panchal, A.R.; Cabanas, J.G. Emergency medical services professional behaviors with violent encounters: A prospective study using standardized simulated scenarios. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2022, 3, e12727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, B.J.; O’Neill, B.J.; O’Meara, P.; Browne, M.; Dealy, M.T. Preventing EMS workplace violence: A mixed-methods analysis of insights from assaulted medics. Injury 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.A.; Murray, R.M.; Davis, A.L.; Shepler, L.J.; Harrison, C.K.; Novinger, N.A.; Allen, J.A. Creation of a Systems-Level Checklist to Address Stress and Violence in Fire-Based Emergency Medical Services Responders. Occupational Health Science 2019, 3, 265–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, J.; Gurevich, M.; Schwartz, B.; Brazeau, P. Interventions for critical incident stress in emergency medical services: a qualitative study. Stress and Health 2009, 25, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, J.; Gurevich, M.; Schwartz, B.; Brazeau, P. What makes an incident critical for ambulance workers? Emotional outcomes and implications for intervention. Work & Stress 2009, 23, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F.; Afolabi, A.A.; Ilesanmi, O.S.; Nucera, G.; Ferrari, G.; Szarpak, L.; Yildirim, M.; Magnavita, N. Workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of Health and Social Sciences 2022, 7, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J. Far and widening: The rise of polarization in Canada; The Public Policy Forum: Ottawa, ON, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, A.J. Quality of employoment and labour market dynamics of health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, D.; Vogel, L. Overworked health workers are "past the point of exhaustion". CMAJ 2023, 195, E309–E310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loriggio, P. Ontario paramedics say ambulance response times are slower due to growing offload delays. CBC News, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Have you been affectedby long ambulance wait times? Let us know. CP24, 2023.

- Shortage of ambulances in Toronto means city not prepared for major disaster, paramedic union says. CBC News, 2023.

- Ontario. Ontario helping more students become paramedic; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for healthcare and social servics workers; 2016. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).