Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic’s first wave, Switzerland was one of the countries with the highest number of coronavirus cases per capita [

1]. The government declared an “extraordinary situation” on March 13, 2020, under the terms of article 7 of the Epidemics Act [

2]. It took measures that had a massive impact on general practices because non-urgent medical activities were canceled [

3] from March 16 to April 27, 2020. In Switzerland, general practice is a private sector activity where physicians work independently and are paid on a fee-for-service basis with fee-for-time funding [

4]. During the first wave, general practitioners (GPs) were invited, not obliged, to support the fight against COVID-19 by managing their suspected coronavirus patients. GPs who did not wish to care for these patients could direct them to testing centers [

3,

5,

6].

In Switzerland, many GPs (45%) work in a solo practice with a medical assistant (MA) [

7] but with limited or no multidisciplinary collaboration with other healthcare professionals [

8]. Since 2019, the Department of Family Medicine at the Center for Primary Care and Public Health (Unisanté) in Lausanne has been implementing a new organizational model in eight pilot general practices via the MOCCA project [

9]. This intervention’s main component is adding a primary care (PC) nurse to the practice staff.

The literature on the COVID-19 pandemic does explore nursing roles [

10], but little attention has been given to nurses working outside hospitals. In addition, the interprofessional collaboration between nurses and GPs is recognized as suboptimal [

11]. Globally, there is a paucity of research on how GPs functioned within interprofessional teams during the pandemic. To help bridge these knowledge gaps, our study examined the roles of nurses working in PC practices between March and June 2020. The study’s specific objectives were to describe the activities and understand the roles of the PC nurses in our pilot general practices during the pandemic.

Methods

We carried out a mixed-methods study [14] that included the collection of quantitative and qualitative data. The benefits of this approach were that we were able to examine issues from multiple angles and explore their underlying mechanisms [15].

Study Setting and Population

This study was conducted in the eight general medical practices in the canton of Vaud (covering urban and rural areas) participating in the MOCCA pilot project. These employ 8 nurses, 26 MAs, and 30 GPs. Vaud is the most populous French-speaking canton in Switzerland, with approximately 800,000 inhabitants and 900 GPs working in either solo or group private practices.

Ethics Statement

Our study involved no patients and did not fall within the scope of Switzerland’s laws on human experimentation. Participation was voluntary and oral consent to participate was obtained from all participants. The information collected concerned data on opinions and practices and was included in the MOCCA project, which had itself already been validated by the data protection committee (Req-2019-00544).

Data Collection

Quantitative Data

Quantitative data came from two sources. Firstly, a web application on HyperText Transfer Protocol, Hypertext Preprocessor framework Laravel) developed for the Mocca pilot project was used to collect details of nurses’ daily activities. Additional COVID-19-related activities were added to the application when the pandemic began. Defined in collaboration with the nurses, these included declaring new cases (both suspected and positive cases), implementing pandemic-related measures (equipment management, hygiene procedures), telephone triage (using clinical and epidemiological criteria, reassuring patients), care management and follow-up (testing, telehealth, home visits), and implementing official guidelines (following recommendations daily).

Secondly, an online survey was developed during COVID-19’s first wave using Research Electronic Data Capture software [

12]. This consisted of 14 questions regarding the activities carried out in the medical practice as a whole (

e.g., number of telephone calls, COVID-19 tests, and consultations). Activities were categorized by professional category (

i.e., nurses, MAs, or GPs). Due to being overloaded with work, one nurse did not participate in the online survey. The responsibility for completing the questionnaire lay with nurses, and this took approximately 30 min per workday to do.

Qualitative Data

Qualitative data were collected between June and September 2020 through:

- -

One focus group discussion (FGD) with eight of the nurses

- -

Nine individual GP interviews, with at least one GP per practice.

The first author moderated the FGD and the interviews, assisted by the last author, who took additional field notes. The FGD lasted approximately 90 min, during which nurses described their daily practice and their opinions regarding their roles during the pandemic’s first wave. The interview guide covered three main groups of topics: role definition, patient and team support, and the nursing role’s strengths and limitations.

The views of nine GPs were also collected to integrate their opinions on nurses’ roles. The individual in-depth interviewing technique is appropriate to a descriptive data collection approach and enables relatively sensitive questions to be answered, which might not be the case in an FGD [

13]. These face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author in each general practice. Each interview was audio recorded and lasted 45–60 min. The main topics covered by the interview guide were the activities assigned to nurses, the added value (or not) of having a nurse in the practice, and the boundaries of the nurse’s role. The investigators followed the interview recommendations developed by Gale [

14] and asked for clarification when necessary.

Data Analysis

We performed descriptive analyses of our quantitative data using Stata software (v16), including frequencies, means, and percentages for the variables of interest. We analyzed the frequencies of the nurses’ activities by dividing them into two periods: period 1 ran from March 16 to April 24, 2020, when the public health authorities required activities be limited to dealing with COVID-19 and emergencies; period 2 ran from April 27 to June 12, 2020, when routine general medicine activities were allowed to recommence. We also compared the distribution of roles between nurses, MAs, and GPs for different activities during the first period.

Regarding qualitative data, the first author transcribed the FGD and interview data verbatim. The FGD and the interviews were anonymized and stored on the Department of Family Medicine’s server. Transcripts were then coded using MAXQDA qualitative data analysis software and analyzed using an analysis guide. A single investigator coded both nurses’ and physicians’ transcripts. First, they assigned descriptive codes to relevant narratives, with the data divided into themes and subthemes. As the coding process progressed, a coding book was created and constantly updated. The authors discussed and interpreted classifications. During this analysis, the first author triangulated the preliminary results by comparing, contrasting, and corroborating them.

We used the conceptual framework proposed by Pluye et al. [

15] to integrate quantitative and qualitative data, and quantitative and qualitative findings were connected, compared, and contrasted in discussions between the authors.

Results

Participants’ Characteristics

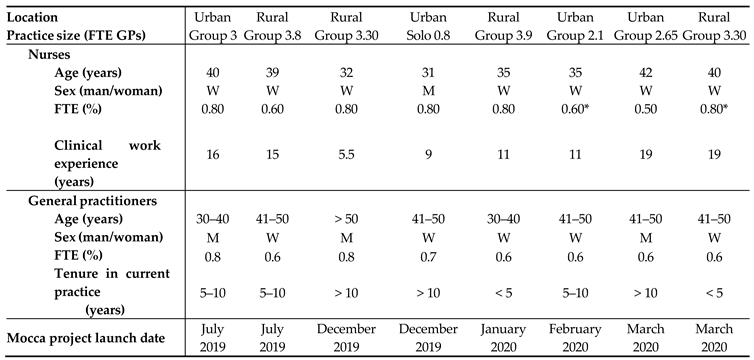

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the nurses and their general practices. Seven of the eight practices were group practices, and four were in urban and semi-urban locations. The study comprised eight nurses (seven women) from 31 to 42 years old; four had worked in their practice for fewer than 6 months. The nurses worked from 50% to 80% of a full-time equivalent position, and they all had more than five years of clinical work experience. The study also included nine general practitioners (five women, four men) from 35 to 52 years old. They had between one and 20 years of work experience in general practice.

Quantitative Results

Table 2 presents the percentages of nurses’ time spent on different activities, grouped into five categories according to the period, and

Table 3 shows the distribution of activities by type of healthcare professional. During period 1, all nursing activities were dedicated to the pandemic crisis, but this decreased to 26.7% of nurses’ time during period 2.

Telephone Triage

As

Table 2 shows, 38.6% of nurses’ working time was dedicated to the telephone triage of potential COVID-19 patients during period 1 (min. 9.2%, max. 66%). In contrast, during period 2, this activity took up 2.3% of their time on average. Depending on the practice, nurses (min. 7.9%, max. 28.6%), MAs (min. 34.9%, max. 76.5%), and GPs (min. 4.1%, max. 84.3%) participated differently in telephone triage (

Table 3).

Guideline Implementation

Nurses’ involvement in the development and implementation of pandemic-specific guidelines (e.g., testing criteria, hygiene procedures) took up an average of 24% of their working time during period 1 (min. 12.7%, max. 43.6) and 5.9% (min. 1.5%, max. 8.2%) during period 2.

Testing for COVID-19

Testing for COVID-19 was completely delegated to the nurse in one practice, was performed by GPs in three, and was shared between GPs and nurses in four. Overall, only 31.7% of all the COVID-19 tests performed (n = 527) were done by nurses.

Care Management and Follow-up

During period 1, care management and follow-up activities were also dealt with heterogeneously across practices. Overall, care took up 21.6% of nurses’ time, on average; however, it took up less than 5% of the time of three nurses. The distribution of these activities by type of healthcare professional showed that all but one nurse shared them with GPs, although three took on more than 30% of their practices’ consultations for suspected COVID cases. Two nurses and their respective MAs did not participate in this activity (

Table 3). Overall, 24% (n = 852) of suspected COVID-19 case consultations were taken on by nurses, with great heterogeneity between practices (min. 0%, max. 50%).

Declaration of Cases

The activity of recording suspected or confirmed cases was the least time-consuming activity during period 1, except for one nurse (40.4%).

Qualitative Results

Although most professionals described changes in their roles and responsibilities during the COVID-19 pandemic, their specific responses to the crisis depended on their practice organization.

Educational Role

Nurses were the referents for COVID-19 good practices for their colleagues during the pandemic’s first wave. Nurses themselves felt that providing support at different levels was one of their fundamental roles. Nurse D: “The role of educating the team—the GPs just as much as the medical assistants—was massive.” GPs also highlighted improvements in team dynamics with a nurse acting as a referent: “Having [a nurse available was reassuring for the medical assistants when they found themselves in uncomfortable situations.”

In addition, nurses played an essential role in reassuring patients and preventing COVID-19, especially by providing correct information on how to reduce contamination and combatting misinformation about the disease.

Nurse C: “We repeated what distancing was, what the safety measures were—perhaps listing the symptoms—what the symptoms are, what to do if they appear.” The nurses screened patients’ needs or anxiety over the telephone. Nearly all the nurses (n = 7) reported being involved in making telephone calls to check on vulnerable patients’ welfare. This helped to reduce their anxiety and monitor their chronic diseases. Nurse F: “We had them on the telephone. People didn’t dare to come in, so, each time, I had to remind them that the practice was open and that if there was anything at all, then they should call us.” Relationships with vulnerable patients were very important to some nurses, and they played significant roles in providing psychological support. Nurse E: “There really were some people who told me that they wanted me to talk to their grandchildren, to tell them that they’d like them to come [and visit].”

Interviews with GPs confirmed that nurses played a supportive and educational role in telephone triage, providing proper counseling. GP C: “The nurse’s role as an educator was important.”

The Nursing Role’s Added Value

Recommended infection control practices were constantly evolving during the first wave of the pandemic. All the GPs recognized that implementing infection control practices was part of the nursing role. GP C: “[They have] precisely the culture of hygiene and the skills that were looking for in nurses.”

All the GPs confirmed that the community support role provided by nurses was useful to them. GP F: “She really took on the role of a community nurse, and she really took over [responsibilities] for us.”

At the same time, because of the many patients with COVID-19 symptoms, some nurses had to support their GPs with telephone follow-up. GP A: “She really had this central role of following-up with patients who were sick and at home. We didn’t necessarily have the time, so for the cases that didn’t have too many complications, she managed them.”

Indeed, practices needed to use all their available human resources more efficiently during this period. GPs delegated non-complex medical consultations to nurses and acknowledged the clinical role that nurses played in consulting suspected COVID-19 patients in their interviews. GP A: “She did some simple consultations; there’s not necessarily always contact with a physician.”

Nurses and GPs also highlighted the important issue of the use of clinical competencies. The nurses felt both versatile and able to respond to a range of pandemic needs. Nurse E: “It’s all about how experiences and specific competencies can be put to use in different ways.” In addition, GPs described nurses as having the clinical skills and sufficient training to fulfill this role, in contrast to MAs. GP D: “I think that a nurse has a little more capacity to adapt to a health crisis.”

They also mentioned the essential coordination role fulfilled by nurses. GP A: “The nurse helped us put in place all these organizational adaptations and to check them against existing guidelines.”

GPs felt that these competencies were not interchangeable with those of MAs. GP F: “A nurse interprets more—goes a bit further than a medical assistant—which is normal considering their career path.” GP C: “So, automatically, a nurse is more at ease, and I don’t think a medical assistant could have taken the nurse’s place.”

Perceived Facilitators and Barriers to Interprofessional Collaboration

Organizational Environment

As each practice was organized differently, the type of leadership influenced the level of interprofessional collaboration. Indeed, interprofessional collaboration was dependent on GPs’ willingness to share tasks with nurses. Nurse E: “Once [the physicians] had understood that the nasal swab was part of a complete clinical evaluation of the patient, and part of prevention, including therapeutic education about loads of things; and when they understood that [I had] those skills, then it was okay for me to go and do them.” In general practices where nurses did no testing or consulting of potential COVID-19 patients, team management and organization depended on a top-down organizational approach. GP G: “In the practice, it was decided that only the physicians—and then only some of them—would do the testing.”

Some nurses reported that they were not involved in shared decision-making because of a traditional hierarchy between GPs and nurses.

Seniority

A lack of seniority in the practice was reported as a barrier to interprofessional teamwork. Nurse F: “It’s clearly a barrier when you’ve only known people for ten days. I arrived in February, and then so did COVID. So then, it’s true, I did not have quite the same autonomy as other nurses.”

Nevertheless, some nurses also reported a lack of confidence. Nurse E: “In the beginning, the GPs carried out testing for COVID-19. Then, afterward, I think that there was a little bit of a step towards more trust, as I hadn’t been in the practice for very long.”

Nursing Competencies

The role of general practice nurse was a new one, implemented within the context of the Mocca project, yet the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the nurses’ integration over a short period. Nurses reported the necessity to adapt very quickly in the uncertain context of period 1. Nurse A: “There was really a week of uncertainty, which was resolved, and then we started with the testing; we changed the technique three times.”

The most valued nursing contributions reported by GPs were nurses’ clinical competencies and organizational skills. All the GPs thought it helpful to have a nurse with these competencies within their medical practice. Nurses’ clinical and organizational skills enhanced the continuity of care as they knew exactly how to act, and they had the necessary flexibility to support GPs in a crisis context. The nurses described how their prior professional experience in emergencies and acute care had facilitated the use of their competencies. Nurse H: “There are organizational skills, the ability to get organized quickly, to deal with the unexpected, and then the ability to make clinical assessments and to look out for the signs of an emergency when in doubt.”

Moreover, the proactive attitude displayed by some nurses influenced their role. One nurse described how her experience of telephone triage was facilitated by her interprofessional collaboration with MAs.

Financing

Some nurses’ roles were limited for financial reasons. Nurse F: “I didn’t do so much. There was a [reimbursement] payment in the balance, so she [the physician] didn’t want to delegate that job to me because she couldn’t bill it afterward.” One GP also reported a reduced role for nurses because billing would be impossible. GP C: “We could have been accused of having billed a telephone consultation, but that it was a nurse who did it.”

Discussion

GPs recognized the added value of having nurses in general practices in this time of crisis, especially thanks to their versatility and autonomy. Indeed, the nurses participating in the study devoted 100% of their working time to dealing with the COVID-19 crisis during period 1, and they were involved in many roles at many levels, including clinical, organizational, and team support activities. In parallel, family medicine nurses experienced their involvement in the pandemic’s first wave in a positive way, mainly thanks to the autonomy they felt. Nevertheless, our results also revealed heterogeneous distributions of activities among professionals, depending on the medical practice.

From the GP’s point of view, the primary added value of having a practice nurse was their versatility across the areas they became involved in. These roles were not interchangeable between a MA and a nurse. Nurses took on different roles at once and performed multiple activities. This was especially reflected in their performance of nasopharyngeal testing, consulting suspected COVID-19 cases, and ensuring that the latest recommendations were followed. In Australia, Halcomb

et al. [

16] also highlighted nurses’ versatility in taking on different roles during the first wave, in similar roles to those observed in our study. The versatility of nurses, as perceived by GPs, enabled us to identify another added value, characterized by the clinical judgment that a nurse can provide and that an MA cannot. For example, telephone screening was distributed among all three types of practice team members, whereas nasopharyngeal testing was shared between nurses and GPs, to varying degrees, depending on the practice. Finally, adaptations to who carried out which roles and when had to be agile, and this was influenced by nurses’ autonomy in organizing workplaces, setting up a triage pool, carrying out tests, and training other members of staff. Crozier [

17] described professional autonomy in nursing practice as “

the ability of the actor to develop, choose and implement strategies by taking into account constraints and opportunities.” The ability of nurses to adapt, showing versatility and autonomy in the context of a global health crisis, was much appreciated by their GP colleagues. Indeed, GPs constantly face time pressures—the possibility of sharing roles with a nurse, with all their inherent skills, meant that GPs considered them to be substantial, versatile, and autonomous aids to dealing with the pandemic context.

From the nursing point of view, despite their different prior professional experiences (acute care, home care, internal medicine), nurses mostly autonomous thanks to their inherent holistic approach to care. Indeed, a nurse can be defined as “

a provider of holistic patient care through services such as preventive care, care coordination” [

18]. More generally, their autonomy in the pandemic context was displayed through their ability to manage patients holistically, to support MAs when necessary, and to implement the latest COVID-19 recommendations and measures.

Another definition of nursing autonomy emphasizes their combination of professional skills, professional decision-making, and interactions with other healthcare professionals [

19]. These professional attributes all go far beyond mere clinical skills, also involving cross-cutting attributes such as confidence in one’s own role, abilities, and collaborative leadership skills in daily practice.

Nurses from an acute care background, for example, felt more confident with the specific skills of dealing with an emergency context. Also, the collaboration between nurses and MAs, in this crisis context, revealed that some nurses showed more leadership than others by being sources of advice and ideas for their respective MAs. Indeed, our study highlighted how some nurses were involved in supporting (psychologically and educationally) their non-medical colleagues in their practice teams. Indeed, these nurses stated that they felt comfortable in their ability to fulfill this role with their MAs. Family medicine nurses demonstrated their ability to work autonomously to meet the needs of patients and MAs during period 1 and the needs of GPs in both periods.

However, the distribution of activities between the professionals in each practice was heterogeneous. Within the context of the Mocca pilot project, the support provided by collaborative practices facilitated the delegation or sharing of certain activities. During the pandemic’s first wave, collaborative practices were facilitated by the emergency context. Indeed, the very nature of clinical work in a health crisis context may have positively influenced interprofessional collaboration. These elements were mentioned by Reeves

et al. [

20], who explained that teamwork was more likely to be observed if the nature of the clinical work was unpredictable. However, the distribution of roles and activities within teams was strongly influenced by whether GPs chose to share work with other professionals. The type of leadership exercised by the GPs in charge of a practice influenced nurses’ involvement. The heterogeneity in the distribution of activities observed within each practice strongly suggests that other factors also influenced GPs in their decision-making. These factors included a drop in reimbursements on a fee-for-service basis if certain activities were carried out by non-medical staff or nurses rather than by themselves. In addition, during period 1, GPs were limited to dealing with urgent consultations and faced a relative financial shortfall at that time. There are similarities with Halcomb’s study, which reported how financial considerations faced by GPs resulted in a reduced role for nurses [

16]. Indeed, financial issues are widely known to limit collaboration between nurses and physicians outside the pandemic context [

18,

20]. Despite the fact that the GPs in our project had funding for nurses’ salaries, Switzerland’s fee-for-service basis for reimbursing GPs’ activities, and the fact that the pandemic kept many patients away from their practices, meant that some perceived finances to be an obstacle to collaboration. Indeed, in the first wave, the telephone consultations or COVID-19 tests performed by nurses were not billable under the Swiss health system. This financial aspect was an obstacle to the transfer of certain activities from one type of professional to another.

There is also a set of intrinsic factors linked to nurses’ individual profiles that have an impact on the distribution of activities: knowing what to do and having the will to do it [

21]. Indeed, some nurses used their knowledge differently, according to their professional and personal experiences and their ability to adapt to the emergency context (knowing what to do). Some nurses also felt more legitimate than others (having the will to act) when performing certain roles, such as supporting MAs or performing COVID tests. Each nurse, depending on their ability and willingness to act, was able to influence this distribution of roles and activities across our eight general practices. As a nurse’s professional identity grows into seniority, building up over several years of experience in family medicine, that identity has an increasing influence on knowing what to do and the willingness to do it.

In contrast, an Australian study [

16] indicated that there was an underutilization of nursing resources in primary care because they were not reimbursed for their activities. As mentioned above, our project funded the Mocca pilot practices’ nursing resources. In the fight against the pandemic, the GPs in these medical practices were free to organize activities with their nurse by defining their own decision-making processes according to their understanding of interprofessional practice. The cooperation observed between nurses and GPs during the crisis showed the importance of ensuring some external support to help the development of an effective interprofessional model. The French government, for example, expanded the range of nurses’ responsibilities after the first wave and recognized the important role of home-care nurses in crisis contexts [

22].

It is important that public healthcare decision-makers are aware of the essential role played by family practice nurses in primary care. GPs and nurses have to develop a common vision of the roles and responsibilities taken on by nurses in general practices so that they can collaborate effectively and implement appropriate strategies in crisis contexts.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, our study involved physicians and nurses who had an inherent interest in participating in interprofessional teamwork.

The nurses were paid by the canton’s Mocca pilot project, so that although the context was experimental, no financial pressure was put on the GPs. The practices were prepared for hosting a person fulfilling a nursing role within their teams. Second, the distributions of the activities and roles taken on by those nurses may have been partly conditioned by nurses’ working time (from 50% to 80% of a full-time equivalent). We were only able to identify trends. Finally, we did not conduct focus groups with MAs due to their busy work schedules, and their perceptions would have been interesting. The study’s strength is that it is, to the best of our knowledge, among the first to explore how frontline nurses working in family medicine or general practices were involved in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. Our research helps us to understand GPs’ and nurses’ experiences during this crisis context. These results are nevertheless probably applicable elsewhere, despite factors that may limit their widespread generalization.