1. Introduction

Understanding how behavioral or cognitive biases affect economic decisions and outcomes is central in modern economics because traditional models based on the assumption that agents are rational struggle to explain a wide range of economic phenomena. For instance, the recurrent occurrence of bubbles and crashes in financial markets poses a challenge to classical models with agents who have unbiased beliefs and always make rational decisions. To overcome these limitations, researchers have been seeking alternative explanations to better understand various abnormal economic phenomena, especially employing the experimental and psychological approach. Some of the groundbreaking work that spawned this relatively new field includes, not limited to, Kahneman and Tversky [

1], Thaler [

2], Fehr and Schmidt [

3], and Loewenstein et al. [

4].

Among many different types of cognitive biases, the so-called unrealistic optimism has recently received particular attention. According to the formal definition provided by Weinstein [

5], unrealistic optimism means that people tend to erroneously believe that negative (positive) outcomes are less (more) likely to occur to themselves compared to the likelihood of those outcomes they attribute to others. In other words, unrealistic optimism indicates the tendency that people typically perceive themselves as invulnerable to misfortune but believe that others are more susceptible to bad luck. For instance, Weinstein [

5] shows that individuals perceive their own chance of developing lung cancer as significantly lower than the true average likelihood of being diagnosed with lung cancer.

After Weinstein [

5] first formally identified this new type of cognitive bias, researchers have subsequently found that unrealistic optimism is pervasive across diverse types of individuals facing different problems; see, for instance, Burger and Palmer [

6], McKenna [

7], Klar et al. [

8], Weinstein and Lyon [

9], and Dillard et al. [

10] among others. In addition, a recent study by Gassen et al. [

11] shows that people continue to exhibit unrealistic optimism using the survey data on individuals’ risk perceptions regarding the likelihood of being infected by COVID-19.

In this paper, we develop an economic model to show that when people exhibit unrealistic optimism, the economy is more likely to enter into recessions and face underinvestment rather than experiencing bubbles or overinvestment. This result is surprising because optimism or overconfidence is generally considered a behavioral characteristic that generates economic booms, excessive risk taking, and overinvestments. In fact, Malmendier and Tate [

12], Gervais et al. [

13], and Hirshleifer et al. [

14] empirically show that overconfident corporate managers tend to overestimate their abilities and overvalue the profitability of new projects, and thus invest more heavily on new projects. Also, Harrison and Kreps [

15] and Scheinkman and Xiong [

16] develop theoretical models to show that asset markets can generate speculative bubbles when investors have heterogeneous beliefs because assets are usually owned by those investors who have the most optimistic view at the moment. In our paper, by particularly paying attention to unrealistic optimism, we show that drastically different outcomes can occur compared to the predictions of the above papers, which do not specifically consider unrealistic optimism.

Our model consists of producers and consumers. Producers produce output goods to maximize the profits, taking production costs into consideration. Initially, each consumer values one unit of the output as 1 in terms of the consumption goods. But, in the future, an aggregate preference shock may hit all consumers. Upon the occurrence of the shock, each consumer will assign a value of less than 1 to one unit of the output. However, each consumer displays unrealistic optimism. Specially, each consumer incorrectly believes that the aggregate shock will hit all other consumers, but not herself. In other words, each consumer believes that she will not be the victim of the adverse event unlike all other consumers.

In the benchmark economy, in which each consumer correctly believes that nobody can avoid the aggregate shock, the output price stays at 1 today but will drop in the future only when the aggregate shock occurs. In this case, every consumer makes zero profits at every date. However, when consumers hold unrealistic optimism, the output price must fall today even before the aggregate shock actually hits the economy.

To see why, note that when consumers exhibit unrealistic optimism, each of them wrongly believes that she can make arbitrage profits in the future if she waits until the aggregate shock occurs, instead of purchasing output goods today. Thus, if the output price does not fall today, the output goods market cannot clear today. Therefore, the output price must fall immediately for the market to clear. Further, when the output price goes down, producers will lose incentives to produce output goods to some extent, leading to underinvestment. In this manner, unrealistic optimism can trigger recessions or crises rather than expansions or bubbles.

It is well known that when all agents have the correct beliefs about the impact of the aggregate shock, the government cannot enhance welfare by providing subsidies to consumers or directly purchasing the output goods. However, when the economy experiences recessions due to the unrealistic optimism of agents, there is room for the government to intervene in the market and improve welfare of the economy. Specifically, suppose that the government provides subsidies to every consumer, who purchases the output goods today, to lift the output price to 1. Then the utility level of those consumers, who newly purchase the output goods, increases because they can buy the output goods, which they value as 1, at a price lower than 1 due to the subsidies. Thus, this increment in their utility offsets the amount of money paid by taxpayers. But when the output price increases, producers produce more outputs, eventually leading to the welfare improvement. This argument can be used to support the effectiveness of a number of government intervention policies implemented during the 2008 financial crisis and 2020 COVID-19 crisis.

Nonetheless, the government must judiciously select the right timing for intervention. If the government intervenes in the market after the aggregate shock hits the economy, the welfare will not be improved or such a policy will be less effective, compared to the case where the government takes the action preemptively. For instance, suppose the government provides subsidies only after the aggregate shock hits the economy. Then, as mentioned above, consumers can still buy the output goods by spending the same amount of money as before due to the subsidies. Then, consumers with unrealistic optimism will falsely expect to exploit the arbitrage opportunity unless the output price remains at a low level as before. As a result, the output price will still stay at the low level, meaning that the government cannot prevent the premature occurrence of recessions. In this regard, we see that the government can improve welfare only when it intervenes in the market at the right time.

Lastly, one may say that other types of optimism can also generate recessions because bubbles caused by optimism or overconfidence are typically followed by recessions or market corrections; see, for instance, Kaizoji and Sornette [

17]. But what we have shown in this paper is that recessions can be precipitated due to unrealistic optimism unlike in the case where bubbles subsequently cause market crashes. In this regard, the mechanism that causes early recessions, introduced in this paper, is new to the literature.

The paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we develop the main model and discuss the model implications. In

Section 3, we extend the model into a dynamic setup. In

Section 4, we conclude.

2. Model and Implications

In this section, we develop a simple model with unrealistic optimism and examine how such a cognitive bias influences output prices and production decisions. We then analyze how the subsidies provided by the government affect the welfare of the economy.

2.1. Simple Model with Unrealistic Optimism

Consider a simple model with a representative producer and a continuum of infinitely many consumers who exhibit a certain type of cognitive bias, which will be described later. There are only two dates indexed by . All agents are risk neutral and discount future consumptions at a rate normalized to 0.

At each date t, the producer can produce units of the output at costs of by taking the output price as given, where represents the marginal cost per unit of output. Although the main results of this paper continue to hold with a more general form of the cost function, we adopt this quadratic cost function for simplicity. Let be the output price at date t. Then the producer decides to produce at each date t. Here, although we interpret the output goods as the real goods for convenience, the main implications of the model can be certainly applied to a setup where we consider financial assets such as stocks or bonds instead of real goods.

We now consider the behavior of consumers. At date 0, all consumers value one unit of the outputs as 1 in terms of the consumption goods. At date 1, an aggregate preference shock will hit the economy with a probability . Upon the arrival of the shock, each consumer will value one unit of the outputs as . Of course, we can interpret this preference shock in many different ways. For example, if we regard the producer as an input supplier and the consumers as the producers of the final goods, we can interpret the preference shock as a productivity shock to those final goods producers.

Each consumer is initially endowed with a certain unit of the consumption goods, which is normalized to 1. For simplicity, we assume that consumption goods are perfectly storable. As such, in this model, each risk-neutral consumer only needs to decide when to buy the output goods between date 0 and date 1. Although we can relax the assumption that consumption goods are perfectly storable, considering such a more general setup would not yield any additional important implications.

Before introducing the unrealistic optimism held by consumers, we first consider the canonical case where all consumers have correct beliefs about the potential impact of the aggregate shock. In this benchmark economy, due to market competition, the price of the output goods at date

t, denoted by

, will be equal to

That is, in equilibrium, the output price is determined in a way that all consumers earn zero profits at each date. For the latter purpose, we refer to the state where the aggregate shock does not occur as the good state and the other state as the bad state.

Regarding the production and consumption decisions, suppose that all agents expect that the output price will be given in the above way. Then, at date 0, (i) the producer produces units of the output, (ii) any consumer who wishes to buy the outputs at date 0 can buy one unit of the output, (iii) the total measure of consumers who buy the outputs at date 0 is equal to , and (iv) the other consumers decide to consume at date 1. At date 1, if the aggregate shock occurs, (i) the producer produces units of the output, (ii) any consumer who wishes to buy the outputs at date 0 can buy units of the output, (iii) the total measure of consumers who buy the outputs is , and (iv) the other consumers consume their own endowment. If the aggregate shock does not occur at date 1, the economic outcomes remain the same as in date 0.

Now, we assume that each consumer is susceptible to a certain type of cognitive bias. Specifically, we assume that each consumer incorrectly believes that the aggregate shock will hit all other consumers, but not herself. But the truth is that the aggregate shock will actually hit all existing consumers and each consumer will eventually learn this fact once the shock occurs at date 1. In the psychology literature, this type of optimism, which states that people tend to overestimate (resp. underestimate) the chances of positive (resp. negative) outcomes occurring to themselves compared to the chances of those outcomes occurring to other people, is widely called unrealistic optimism, optimism bias, or comparative optimism; see, for instance, Weinstein [

18], Weinstein and Klein [

19], Hoorens et al. [

20], Jefferson et al. [

21], and Gassen et al. [

11].

The main result of this model is that the unrealistic optimism can cause an earlier market collapse and underinvestment. To see why, first recall that every consumer believes the aggregate shock to hit all other consumers, but not herself. As such, every consumer expects that the output price will drop to A at date 1 if the aggregate shock occurs at that date, because she believes that the shock will at least hit all other consumers. But then, from the date-0 perspective, each consumer believes that she can make positive profits equal to in expectation if she purchases the output goods at date 1 rather than at date 0. Hence, for the output market to clear at date 0, the output price must drop to some extent at date 0 so that each consumer would be indifferent between purchasing the outputs at date 0 or date 1. For clarification, note that no consumers can actually earn positive profits in the end because the truth is that the aggregate shock will actually hit all consumers as mentioned above.

Accordingly, in the presence of unrealistic optimism, the output price at date 0 is determined so as to satisfy the following indifference condition:

which implies

The left-hand side of (

2) indicates the immediate profits that each consumer can earn if she buys the output goods at date 0. The right-hand side denotes the present value of the profits that each consumer expects to earn if she buys the output goods at date 1, as discussed above. Then, since these two terms must be equal to each other for the output market at date 0 to clear, the output price at that date is given by the expression in (

3). This result implies that the output price will be more depressed due to the unrealistic optimism if the aggregate shock is more likely to occur or the magnitude of the shock, measured by

, is larger, both of which are intuitive.

In addition, the above result also implies that the unrealistic optimism causes underinvestment. Specifically, since the output price falls below 1 at date 0, which is the intrinsic value of the output, the producer decides to produce only units of the output rather than as in the case without the unrealistic optimism.

These results sharply contrast with our common intuition because optimism is generally viewed as a cognitive bias that leads to bubbles in financial markets or overinvestment in the production side. For instance, Harrison and Kreps [

15] and Scheinkman and Xiong [

16] show that when investors have heterogeneous beliefs and short selling is not allowed, markets exhibit bubbles not only because assets are priced by those investors who have the most optimistic view on given assets but also because those investors can resell their assets when their own valuation drops relative to the valuation of other investors. Also, Malmendier and Tate [

12], Gervais et al. [

13], and Hirshleifer et al. [

14] provide empirical evidence that overconfident managers tend to overvalue their investment projects and thus invest more aggressively in new projects than other managers without overconfidence, especially when firms have abundant internal capital.

The type of optimism considered in this paper is different from the types of optimism considered in the above papers. In our paper, each consumer correctly estimates the impact of the aggregate shock on all other consumers but incorrectly estimates the impact of the aggregate shock on herself. When agents have this type of optimism, our model shows that markets can rather experience an early downturn and firms underinvest in new projects. In this regard, our paper sheds new light on the true sources of economic recessions and investment distortions through the lens of behavioral bias.

2.2. Government Intervention and Welfare

In this section, we examine whether the government can increase the welfare of the economy by providing subsidies to consumers exhibiting unrealistic optimism. Throughout the model, we define the welfare at each date as the sum of the consumer surplus and the producer surplus, created from production at that date, minus the amount of government subsidies. We first consider the benchmark model in which consumers do not exhibit unrealistic optimism. We then consider the model with unrealistic optimism.

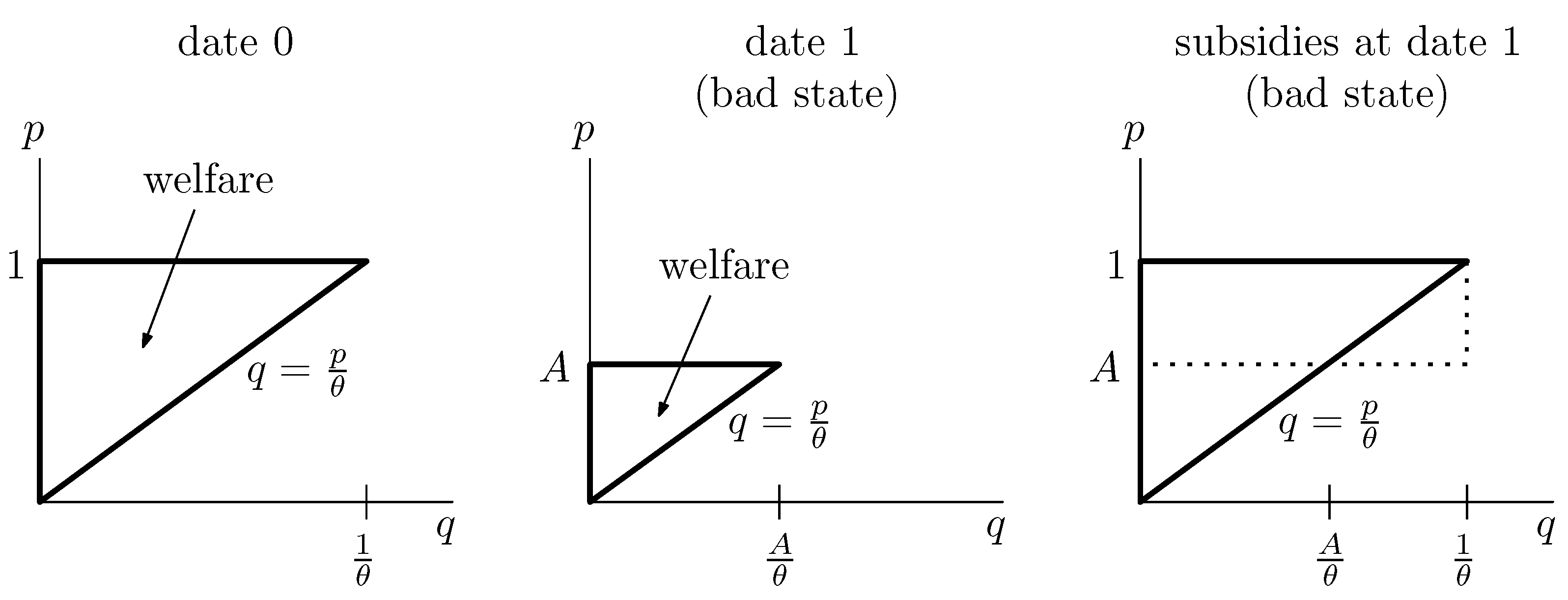

Benchmark model: In the benchmark model without unrealistic optimism, it is well known that the government cannot improve welfare by providing subsidies at that date. For completeness, we first see that the welfare at each date can be described in the first two panels of

Figure 1. Specifically, at date 0, the consumer surplus is 0 because the outputs are sold at a price that is equal to the true valuation of consumers. The producer surplus is equal to

where 1 is the output price at date 0 and

is the marginal cost of production. Hence, the welfare is also equal to

. This producer surplus corresponds to the area of the triangle in the left panel of

Figure 1. The welfare in the good state at date 1 is equal to the welfare at date 0 in the benchmark model and so, we have omitted plotting this case in

Figure 1. Due to the similar argument used for the case at date 0, we see that the welfare in the bad state at date 1 is equal to

, which corresponds to the area of the triangle in the middle panel of

Figure 1.

In this case, suppose the government aims to raise the output price from

A to 1 in the bad state at date 1, by providing subsidies of

per unit output to every consumer who buys the outputs. Then, the consumer surplus is still 0 because each consumer, who values one unit of output as

A, still pays

A from her own pocket. The producer surplus, however, increases from

to

because the output price has been raised to 1 due to subsidies. This producer surplus corresponds to the area of the triangle with the thick edges in the right panel of

Figure 1. In other words, the producer surplus increases by

when the government provide subsidies. But the amount of subsidies provided is equal to

because the total units of the outputs sold are

and the amount of subsidies per unit output is

. These results imply that the welfare of the economy is reduced by

In other words, the sum of the consumer and producer surplus corresponds to the area of the big triangle in the right panel of

Figure 1, whereas the amount of subsides corresponds to the area of the rectangle. Hence, we can reconfirm that the welfare of the economy is lowered when the government subsidizes consumers.

For robustness, even if the government intervenes in the market by directly purchasing the output goods using the money of taxpayers, the welfare cannot be improved. Specifically, suppose that the government directly purchases the output goods at the price of 1 in the bad state at date 1 and then distributes those output goods to consumers. Then, the utility of those consumers who receive the output goods from the government increases by A. But the amount of subsidies spent for one unit of the output was 1. Thus, the welfare actually drops as in the previous case even if the government adopts this alternative intervention policy. In this regard, in what follows, we focus on the first type of intervention policy. Also, note that the first type of intervention policy is more realistic because we can interpret such a policy as tax cuts on consumer goods.

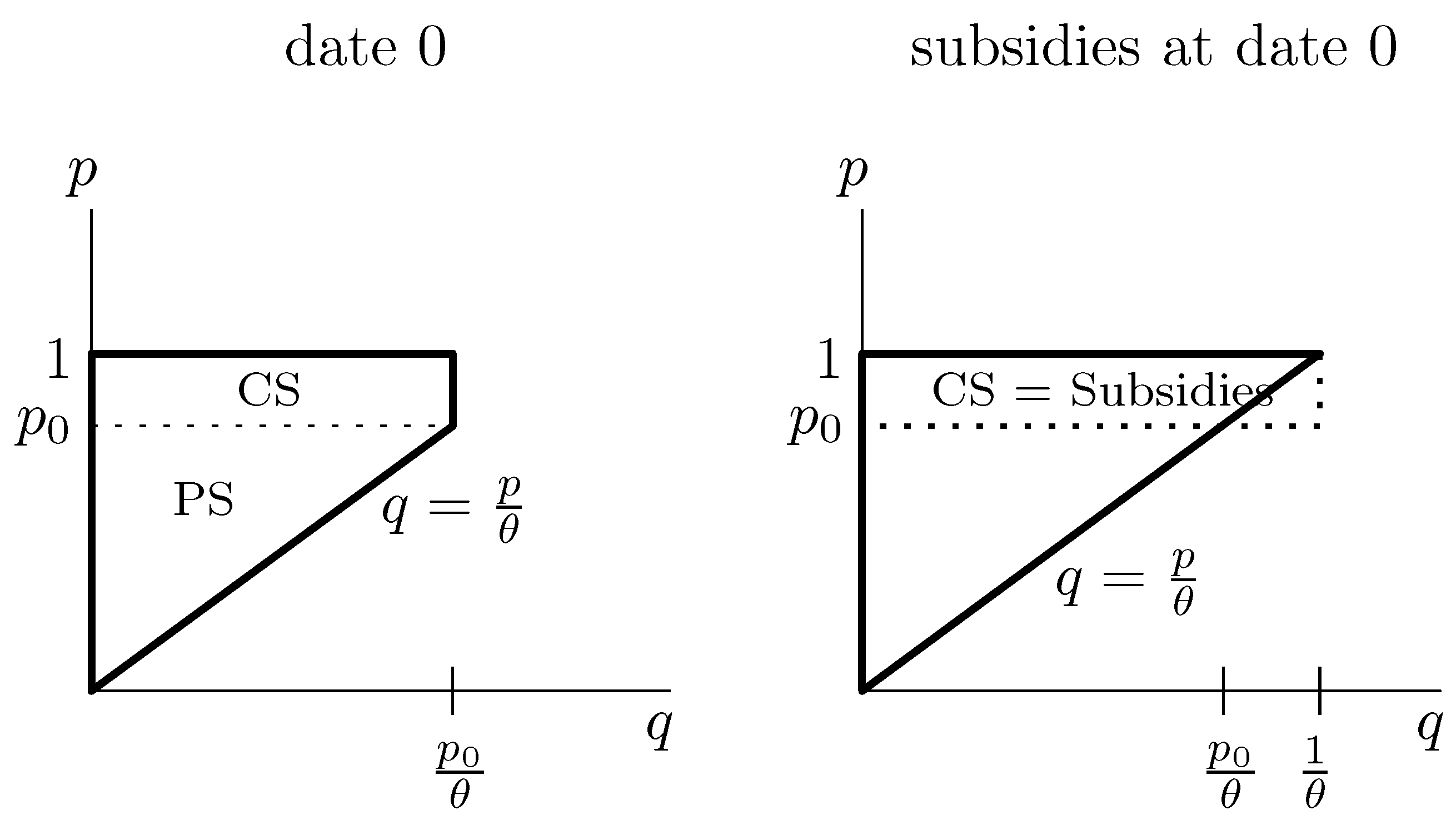

With Unrealistic Optimism: When consumers have unrealistic optimism, we show that government subsidies, if carefully designed, can effectively improve welfare of the economy. To see why, first note that the welfare of this economy at date 0 can be described in

Figure 2.

Specifically, at date 0, the consumer surplus is equal to

because (i) consumers can now purchase one unit of the output goods at the price of

, which is given in (

3), while the true value of the output goods is 1 to those consumers, and (ii) the total units of outputs produced is equal to

. The producer surplus is equal to

, similar to the case in the benchmark model. Thus, the welfare at date 0 is

At date 1, the welfare is the same as that in the benchmark model regardless of whether the aggregate shock hits the economy or not. So, we have omitted to plot this case in

Figure 2.

Now, we consider two possible government intervention policies: one is to provide subsidies at date 0 and the other is to provide subsidies in the bad state at date 1. Under the first policy, the welfare of the economy is equal to

The consumer surplus increases to

because a consumer still needs to pay only

from her own pocket to purchase one unit of the output, but the total units of the outputs produced increases from

to

. This consumer surplus corresponds to the area of the rectangle, enclosed by the solid and dotted lines, in the right panel of

Figure 2. The producer surplus is equal to

because the price has been raised to 1. The producer surplus is depicted by the triangle enclosed by the solid lines in the right panel of the same figure. The amount of subsidies is equal to

because the government subsidizes

per unit of output and the total units of the output produced is

. That is, when the output price is pushed down due to unrealistic optimism, the consumer surplus is the same as the amount of subsidies provided by the government, as shown in the figure. Combining the result in (

4), we see that the welfare increases if the government provides subsidies at date 0, that is, before the aggregate shock occurs. This result is intuitive because when the output price is suppressed due to the cognitive bias of consumers, there is room for the government to intervene in the market and improve welfare.

However, we now show that if the government intervenes in the market by implementing the second type of policy mentioned above, the welfare will still decline. Interestingly, when the government subsidizes consumers at date 1, the output price at date 0 will remain unchanged at

as described in (

3). The reason for this outcome is that each consumer can still pay

A from her own pocket to buy one unit of the output in the bad state at date 1. So, from the date-0 perspective, each consumer still incorrectly believes that she could make profits of

in the bad state at date 1. Hence, the output price at date 0 must stay unchanged at

for the market to clear at date 0. Then, as we have already seen that if the government intervenes in the market at date 1, the welfare will decrease at that date, such an intervention policy cannot improve welfare at any date.

The above two results imply that the government must take the action early, that is, before the aggregate shock hits the economy, to enhance welfare of the economy. Otherwise, the government would only waste the money of taxpayers. In this regard, investigating an optimal timing of the government intervention should be very critical for the entire economy.

3. Extension into a Dynamic Setup

In this section, we extend the above model into a dynamic setup with infinite horizons to show the main result of our model continues to hold in a more general setting. Specifically, we incorporate the unrealistic optimism into the neoclassical investment model developed by Hayashi [

22].

To begin, consider a firm that produces stochastic outputs over time, where the output level is determined by the investment decisions of the firm. Specifically, the time-

t output level, denoted by

, evolves according to

where

is the investment rate at time

t,

is a constant volatility, and

is a standard Brownian motion. To choose the investment level of

at time

t, the firm has to spend

as the convex adjustment costs, where

is a constant that measures the size of investment costs. At each point in time, the firm makes the investment decisions to maximize the present value of its future profits. We assume that all agents are risk neutral and discount future consumptions at a constant risk-free rate of

r.

Initially, the firm can sell one unit of the outputs at the normalized price of 1. But an aggregate preference shock may hit the firm’s consumers in the future. Specifically, the preference shock will arrive at a Poisson rate of . Upon the arrival of the shock, all consumers will value one unit of the outputs as . In this regard, we can also interpret the preference shock to consumers as the profitability shock to the firm. We call the periods with the high profitability the normal times and the periods with the low profitability the bad times. Also, as in the previous model, each consumer can buy at most one unit of the outputs throughout her life due to some budget constraints.

If consumers have correct beliefs about the impacts of the aggregate shock, the price of the output will stay at 1 during the normal times and will fall right after the aggregate shock hits the economy. However, as in the above simple model, we assume that consumers incorrectly believe that the aggregate shock will hurt only other consumers, but not herself. In this case, we will show that the output price will not stay at 1 during the normal times. Specifically, let P denote the per-unit output price during the normal times. We will later verify that the output price should be a constant during the normal times due to the stationary structure of the model.

To pin down the output price during the normal times, we consider two strategies regarding when to buy the product. The first strategy is that a consumer buys the product just today. The second possible strategy is that a consumer waits until the aggregate shock hits the economy. Under the first strategy, the consumer will immediately earn

as profits, while under the second strategy, she expects to earn

in terms of the time-

t present value value. Then, for the output market to clear at each point in time, each consumer must be indifferent between those two strategies, which implies

This result first means that the output price lies between

A and 1 as expected. From this expression, we can also see that the output price falls more due to the unrealistic optimism when the discount rate is lower, the aggregate shock is more likely to occur, and the magnitude of the shock is larger. All these results are intuitive.

For clarification, in the above argument, we have used the fact that consumers do not have any incentives to buy the product

after the aggregate shock hits the economy because of discounting. Further, we can actually consider other more general strategies in addition to the above-mentioned two strategies. Specifically, let

denote the arrival time of the aggregate shock. Then consider a consumer who aims to buy the product at time

, where

is any specific date. That is, this consumer will buy the product at time

T if the aggregate shock has not occurred until then, but will buy the product right after the aggregate shock hits the economy if that event happens before time

T. Under this strategy, the consumer expects to earn the profits of

by definition. Then we see that the amount of these profits does not depend on the specific time

T if the output price

P is given by (

5). In fact, this argument can be further extended to the case where the target purchasing time

T is a random stopping time that is independent of the arrival time of the aggregate shock. Therefore, we confirm that

P expressed in (

5) is indeed an equilibrium price.

We now calculate the present value of the firm. We first pin down the firm value during the bad times. During this period, the firm value denoted by

satisfies the following Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman (HJB) equation:

The left-hand side is the required return. The first term on the right-hand side is the amount of cash flows produced by the firm, the second term is the adjustment costs, and the remaining terms represent the changes in the firm value due to the growth and fluctuations in the output level. We conjecture that

is equal to

for some constant

, which is called Tobin’s Q. Then, using the first-order condition that

, we see that

must satisfy

Hence, we find that Tobin’s Q and the optimal investment level during the bad times are respectively given by

where we have excluded the other possible choice for

and

to ensure that the growth rate

should not exceed

r in the risk-neutral measure. We also impose the parameter condition that

to ensure that the investment rate is positive.

During the normal times, the firm value denoted by

satisfies the following HJB equation:

We again conjecture that

for some constant

q. Then, proceeding similarly as above, we find that Tobin’s Q and the optimal investment level during the normal times are respectively given by

From this result, we clearly see that the optimistic bias causes underinvestment rather than overinvestment because the socially optimal level of investment is equal to

We have therefore characterized a dynamic model with infinite horizons, in which consumers display unrealistic optimism. This model shows that even if the aggregate shock is expected to hit the economy in the far future, the output price must drop to some extent immediately today. This result therefore confirms that recessions or market crashes can be precipitated by unrealistic optimism.

4. Further Discussions and Conclusions

This paper has explored the economic implications of unrealistic optimism, a cognitive bias that leads individuals to underestimate their susceptibility to negative events while overestimating the vulnerability of others. The existing literature has highlighted the prevalence of unrealistic optimism in diverse contexts and its impact on economic decision-making.

To shed a new perspective on the effects of unrealistic optimism on economic decisions and outcomes, we develop a model, in which consumers have unrealistic optimism. Using this model, we show that when consumers have this type of cognitive bias, the economy is more likely to suffer from early recessions and underinvestment. Our key insight is that in the presence of unrealistic optimism among all consumers, the price of output goods must promptly drop to induce consumers, who wrongly believe they can capitalize on an arbitrage opportunity in the future, to be indifferent between purchasing output goods today or at a later time.

The paper also discusses the role of government intervention in mitigating the adverse effects of recessions induced by unrealistic optimism. While acknowledging the potential effectiveness of subsidies, the timing of government intervention is crucial. Preemptive action that is taken before the occurrence of the aggregate shock proves more effective in preventing premature recessions.

Lastly, in contrast to other forms of optimism that generally lead to market bubbles followed by corrections, the unique contribution of this paper lies in revealing how unrealistic optimism can accelerate recessions. In this regard, a more comprehensive investigation is needed to uncover the true origins of recessions and explore potential remedies to deter or mitigate crises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.D.; Modeling, H.D.; Methodology and model analysis, H.D. and J.P.; Wrinting, H.D. and J.P.; Literature review, J.P.; Funding acquisition, H.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Hanyang University under the grant HY202300000003435.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HJB |

Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman |

References

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing science 1985, 4, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The quarterly journal of economics 1999, 114, 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G.F.; Weber, E.U.; Hsee, C.K.; Welch, N. Risk as feelings. Psychological bulletin 2001, 127, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of personality and social psychology 1980, 39, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.M.; Palmer, M.L. Changes in and generalization of unrealistic optimism following experiences with stressful events: Reactions to the 1989 California earthquake. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 1992, 18, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, F.P. It won’t happen to me: Unrealistic optimism or illusion of control? British journal of psychology 1993, 84, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, Y.; Medding, A.; Sarel, D. Nonunique invulnerability: Singular versus distributional probabilities and unrealistic optimism in comparative risk judgments. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1996, 67, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Lyon, J.E. Mindset, optimistic bias about personal risk and health-protective behaviour. British Journal of Health Psychology 1999, 4, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, A.J.; McCaul, K.D.; Klein, W.M. Unrealistic optimism in smokers: Implications for smoking myth endorsement and self-protective motivation. Journal of health communication 2006, 11, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassen, J.; Nowak, T.J.; Henderson, A.D.; Weaver, S.P.; Baker, E.J.; Muehlenbein, M.P. Unrealistic optimism and risk for COVID-19 disease. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmendier, U.; Tate, G. CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. The journal of finance 2005, 60, 2661–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, S.; Heaton, J.B.; Odean, T. Overconfidence, compensation contracts, and capital budgeting. The Journal of Finance 2011, 66, 1735–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, D.; Low, A.; Teoh, S.H. Are overconfident CEOs better innovators? The journal of finance 2012, 67, 1457–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.M.; Kreps, D.M. Speculative investor behavior in a stock market with heterogeneous expectations. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 1978, 92, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinkman, J.A.; Xiong, W. Overconfidence and speculative bubbles. Journal of political Economy 2003, 111, 1183–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaizoji, T.; Sornette, D. Bubbles and Crashes. Encyclopedia of Quantitative Finance 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems: Conclusions from a community-wide sample. Journal of behavioral medicine 1987, 10, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Klein, W.M. Unrealistic optimism: Present and future. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 1996, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorens, V.; Van Damme, C.; Helweg-Larsen, M.; Sedikides, C. The hubris hypothesis: The downside of comparative optimism displays. Consciousness and Cognition 2017, 50, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefferson, A.; Bortolotti, L.; Kuzmanovic, B. What is unrealistic optimism? Consciousness and cognition 2017, 50, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, F. Tobin’s marginal q and average q: A neoclassical interpretation. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 1982, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).