1. Introduction

Understanding how behavioral or cognitive biases affect economic decisions and outcomes is central in modern economics because traditional models based on the assumption that agents are rational struggle to explain a wide range of economic phenomena. For instance, the recurrent occurrence of bubbles and crashes in financial markets poses a challenge to classical models with agents who have unbiased beliefs and always make rational decisions. To overcome these limitations, researchers have been seeking alternative explanations to better understand various abnormal economic phenomena, especially employing experimental and psychological approaches. Some of the groundbreaking work that spawned this relatively new field includes, not limited to, Kahneman and Tversky [

1], Thaler [

2], Fehr and Schmidt [

3], and Loewenstein et al. [

4].

Among many different types of cognitive biases, the so-called unrealistic optimism has recently received particular attention. According to the formal definition provided by Weinstein [

5], unrealistic optimism means that people tend to erroneously believe that negative (positive) outcomes are less (more) likely to occur to themselves compared to the likelihood of those outcomes they attribute to others. In other words, unrealistic optimism indicates the tendency that people typically perceive themselves as invulnerable to misfortune but believe that others are more susceptible to bad luck. For instance, Weinstein [

5] shows that individuals perceive their own chance of developing lung cancer as significantly lower than the true average likelihood of being diagnosed with that disease.

After Weinstein [

5] first formally identified this new type of cognitive bias, researchers have subsequently found that unrealistic optimism is pervasive across diverse types of individuals facing different problems; see, for instance, Burger and Palmer [

6], McKenna [

7], Klar et al. [

8], Davidson and Prkachin [

9], Weinstein and Lyon [

10], and Dillard et al. [

11] among others. In particular, a recent study by Gassen et al. [

12] shows that people continue to exhibit this type of cognitive bias, using the survey data on individuals’ risk perceptions regarding the likelihood of being infected by COVID-19. However, despite the prevalence of unrealistic optimism and its potential impact on business performance and decisions, the characteristics and potential consequences of unrealistic optimism have been largely ignored by economists, corporate managers, and policymakers, as argued by Coelho [

13].

In this paper, we develop an economic model to show that when people hold unrealistic optimism, the economy is more likely to enter into recessions and face underinvestment rather than experiencing bubbles or overinvestment. This result is surprising because optimism or overconfidence is generally considered a behavioral characteristic that generates economic booms, excessive risk taking, or overinvestments. In fact, Malmendier and Tate [

14], Gervais et al. [

15], and Hirshleifer et al. [

16] empirically show that overconfident corporate managers tend to overestimate their abilities and overvalue the profitability of new projects, and thus invest more heavily on new investment opportunities. Also, Harrison and Kreps [

17] and Scheinkman and Xiong [

18] develop theoretical models to show that asset markets can generate speculative bubbles when investors have heterogeneous beliefs because assets are usually owned by investors who have the most optimistic view at every point in time. In our paper, by particularly paying attention to unrealistic optimism, we show that drastically different outcomes can occur compared to the predictions of the above-mentioned papers, which do not specifically consider unrealistic optimism.

Our model consists of producers and consumers. Producers produce output goods to maximize their profits, taking the output price and production costs into consideration. Initially, each consumer values one unit of the output as 1 in terms of the consumption goods. But, in the future, an aggregate preference shock may hit all consumers. Upon the occurrence of the shock, each consumer will assign a value of less than 1 to one unit of the output. However, each consumer is assumed to hold unrealistic optimism in this model. Specially, every consumer incorrectly believes that the aggregate shock will hit all other consumers, but not herself. In other words, each consumer considers that at least she will not be the victim of the adverse event unlike all other consumers.

In the benchmark economy, in which each consumer correctly believes that nobody can avoid the aggregate shock, the output price stays at 1 today but will drop in the future exactly when the aggregate shock occurs. In this case, every consumer makes zero profits at every date. However, when consumers hold unrealistic optimism, the output price falls today even before the aggregate shock actually hits the economy.

To see why, note that when consumers exhibit unrealistic optimism, each of them wrongly believes that she can make arbitrage profits in the future if she waits until the aggregate shock occurs, instead of purchasing output goods today. Thus, if the output price does not fall today, the output goods market cannot clear today. Therefore, the output price must fall immediately for the market to clear. Further, once the output price plummets, producers will lose incentives to produce output goods to some extent, leading to underinvestment. Through this mechanism, unrealistic optimism can trigger early recessions and underinvestment even before the occurrence of the shock rather than causing expansions or bubbles.

A well-known phenomenon that has been recurrently observed in the real world is that both the real economy and asset markets tend to exhibit sudden crashes and slow recoveries. For instance, according to Veldkamp [

19] and Ordonez [

20], during Mexico’s 1994-1995 peso crisis, real lending rates in Mexico rose from 21% to 91% just in four months, but it took 30 months for the lending rates to reach their pre-crisis level. Regarding other economic variables, investment and output per capital respectively dropped 35% and 17% in just three quarters, but it took more than two years for those variables to recover. Similarly, during the 1998 Russian financial crisis, real lending rates surged from 30% to 150% in less than two months, but it took 27 months for the lending rates to return to their pre-crisis level. What is also interesting is that Ordonez [

20] shows that this asymmetric pattern is more pronounced in countries with less developed financial systems.

Researchers have attempted to explain this intriguing phenomenon by adopting various arguments. For instance, Veldkamp [

19] argues that during economic booms, public information about economic states is more abundantly produced and so, asset prices and economic activities adjust more rapidly during booms, which can potentially trigger a sudden crash when the economic state starts to make a downturn. Ordonez [

20] argues that recoveries tend to be delayed because monitoring costs for lenders are more likely to increase during recessions or crisis periods. While these papers use information-based arguments, our paper proposes a new argument based on a behavioral bias. Also, in those papers, recessions occur exactly when a negative shock hits the economy. But, in our paper, recessions can be accelerated due to unrealistic optimism held by individuals.

Moreover, one may say that other more general types of optimism can also generate recessions because booms or bubbles caused by optimism are typically followed by burst or market corrections; see, for instance, Kaizoji and Sornette [

21]. But what we show in this paper is that recessions can be expedited due to unrealistic optimism unlike in the case where bubbles are followed by market crashes subsequently. In this regard, the mechanism introduced in this paper, which can cause early recessions, indeed sheds new light on our understanding of the causes and sources of economic downturns.

Our paper also investigates whether the government can potentially mitigate economic crises that may occur due to the above mechanism rooted in behavioral bias. It is well known that when all agents have the correct beliefs about the impact of the aggregate shock, the government cannot enhance welfare by providing subsidies to consumers or directly purchasing the output goods. However, when the economy experiences recessions due to the unrealistic optimism of agents, there is room for the government to intervene in the market and improve welfare of the economy. Specifically, suppose that the government provides subsidies to every consumer, who purchases the output goods today, to lift the output price to 1. Then the utility level of those consumers, who newly purchase the output goods, increases because they can buy the output goods, which they value as 1, at a price lower than 1 due to the subsidies. Thus, this increment in their utility offsets the amount of money paid by taxpayers. But when the output price increases, producers produce more outputs, eventually leading to the welfare improvement. This argument can be used to support the effectiveness of a number of government intervention policies implemented during the 2008 financial crisis and 2020 COVID-19 crisis.

Nonetheless, the government must judiciously select the right timing for intervention. If the government intervenes in the market after the aggregate shock hits the economy, the welfare will not be improved or such a policy will be less effective, compared to the case where the government takes the action preemptively. For instance, suppose the government provides subsidies only after the aggregate shock hits the economy. Then, as mentioned above, consumers can still buy the output goods by spending the same amount of money as before due to the subsidies. Then, consumers with unrealistic optimism will falsely expect to exploit the arbitrage opportunity unless the output price remains at a low level as before. As a result, the output price will still stay at the low level, meaning that the government cannot prevent the premature occurrence of recessions. In this regard, we see that the government can improve welfare only when it intervenes in the market at the right time.

The paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we develop the main model and discuss the model implications. In

Section 3, we provide concluding remarks.

2. Model and Implications

In this section, we develop a simple model with unrealistic optimism and examine how such a cognitive bias influences output prices and production decisions. We then analyze how the subsidies provided by the government affect the welfare of the economy.

2.1. Simple Model with Unrealistic Optimism

Consider a simple model with a representative producer and a continuum of infinitely many consumers who are prone to a certain type of cognitive bias, which will be described later. There are only two dates indexed by . All agents are risk neutral and discount future consumptions at a rate normalized to 0.

At each date t, the producer can produce units of the output at costs of by taking the output price as given, where represents the marginal cost per unit of output. Although the main results of this paper continue to hold with a more general form of the cost function, we adopt this quadratic cost function for simplicity. Let be the output price at date t. Then the producer decides to produce at each date t. Here, although we interpret the output goods as the real goods for convenience, the main implications of the model can be certainly applied to a setup where we consider financial assets such as stocks or bonds instead of real goods.

We now consider the behavior of consumers. At date 0, all consumers value one unit of the outputs as 1 in terms of the consumption goods. At date 1, an aggregate preference shock will hit the economy with a probability . Upon the arrival of the shock, each consumer will value one unit of the outputs as . Of course, we can interpret this preference shock in many different ways. For example, if we regard the producer as an input supplier and the consumers as the producers of the final goods, we can interpret the preference shock as a productivity shock to those final goods producers.

Each consumer is initially endowed with a certain unit of the consumption goods, which is normalized to 1. For simplicity, we assume that consumption goods are perfectly storable. As such, in this model, each risk-neutral consumer only needs to decide when to buy the output goods between date 0 and date 1. Although we can relax the assumption that consumption goods are perfectly storable, considering such a more general setup would not yield any additional important implications.

Before introducing the unrealistic optimism held by consumers, we first consider the canonical case where all consumers have correct beliefs about the potential impact of the aggregate shock. In this benchmark economy, due to market competition, the price of the output goods at date

t, denoted by

, will be equal to

That is, in equilibrium, the output price is determined in a way that all consumers earn zero profits at each date. For the latter purpose, we refer to the state where the aggregate shock does not occur as the good state and the other state as the bad state.

Regarding the production and consumption decisions, suppose that all agents expect that the output price will be given in the above way. Then, at date 0, (i) the producer produces units of the output, (ii) any consumer who wishes to buy the outputs at date 0 can buy one unit of the output, (iii) the total measure of consumers who buy the outputs at date 0 is equal to , and (iv) the other consumers decide to consume at date 1. At date 1, if the aggregate shock occurs, (i) the producer produces units of the output, (ii) any consumer who wishes to buy the outputs at date 0 can buy units of the output, (iii) the total measure of consumers who buy the outputs is , and (iv) the other consumers consume their own endowment. If the aggregate shock does not occur at date 1, the economic outcomes remain the same as in date 0.

Now, we assume that each consumer is susceptible to a certain type of cognitive bias. Specifically, we assume that each consumer incorrectly believes that the aggregate shock will hit all other consumers, but not herself. But the truth is that the aggregate shock will actually hit all existing consumers and each consumer will eventually learn this fact once the shock occurs at date 1. In the psychology literature, this type of optimism, which states that people tend to overestimate (resp. underestimate) the chances of positive (resp. negative) outcomes occurring to themselves compared to the chances of those outcomes occurring to other people, is widely called unrealistic optimism, optimism bias, or comparative optimism; see, for instance, Weinstein [

22], Weinstein and Klein [

23], Hoorens et al. [

24], Jefferson et al. [

25], and Gassen et al. [

12].

Using this model, we show that the unrealistic optimism can cause an earlier market collapse and underinvestment. To this aim, first recall that every consumer believes the aggregate shock to hit all other consumers, but not herself. As such, every consumer expects that the output price will drop to A at date 1 if the aggregate shock occurs at that date, because she believes that the shock will at least hit all other consumers. But then, from the date-0 perspective, each consumer believes that she can make positive profits equal to in expectation if she purchases the output goods at date 1 rather than at date 0. Hence, for the output market to clear at date 0, the output price must drop to some extent at date 0 so that each consumer would be indifferent between purchasing the outputs at date 0 or date 1. For clarification, note that no consumers can actually earn positive profits in the end because the truth is that the aggregate shock will actually hit all consumers as mentioned above.

Accordingly, in the presence of unrealistic optimism, the output price at date 0 is determined so as to satisfy the following indifference condition:

which implies

The left-hand side of (

2) indicates the immediate profits that each consumer can earn if she buys the output goods at date 0. The right-hand side denotes the present value of the profits that each consumer expects to earn if she buys the output goods at date 1, as discussed above. Then, since these two terms must be equal to each other for the output market at date 0 to clear, the output price at that date is given by the expression in (

3). This result implies that the output price will be more depressed due to the unrealistic optimism if the aggregate shock is more likely to occur or the magnitude of the shock, measured by

, is larger, both of which are intuitive.

In addition, the above result also implies that the unrealistic optimism causes underinvestment. Specifically, since the output price falls below 1 at date 0, which is the intrinsic value of the output, the producer decides to produce only units of the output rather than as in the case without the unrealistic optimism.

These results sharply contrast with our common intuition because optimism is generally viewed as a cognitive bias that leads to bubbles in financial markets or overinvestment in the production side. For instance, Harrison and Kreps [

17] and Scheinkman and Xiong [

18] show that when investors have heterogeneous beliefs and short selling is not allowed, markets exhibit bubbles not only because assets are priced by those investors who have the most optimistic view on given assets but also because those investors can resell their assets when their own valuation drops relative to the valuation of other investors. Also, Malmendier and Tate [

14], Gervais et al. [

15], and Hirshleifer et al. [

16] provide empirical evidence that overconfident managers tend to overvalue their investment projects and thus invest more aggressively in new projects than other managers without overconfidence, especially when firms have abundant internal capital.

The type of optimism considered in this paper is different from the types of optimism considered in the above papers. In our paper, each consumer correctly estimates the impact of the aggregate shock on all other consumers but incorrectly estimates the impact of the aggregate shock on herself. When agents have this type of optimism, our model shows that markets can rather experience an early downturn and firms underinvest in new projects. In this regard, our paper sheds new light on the true sources of economic recessions and investment distortions through the lens of behavioral bias.

2.2. Government Intervention and Welfare

In this section, we examine whether the government can increase the welfare of the economy by providing subsidies to consumers exhibiting unrealistic optimism. Throughout the model, we define the welfare at each date as the sum of the consumer surplus and the producer surplus, created from production at that date, minus the amount of government subsidies. We first consider the benchmark model in which consumers do not exhibit unrealistic optimism. We then consider the model with unrealistic optimism.

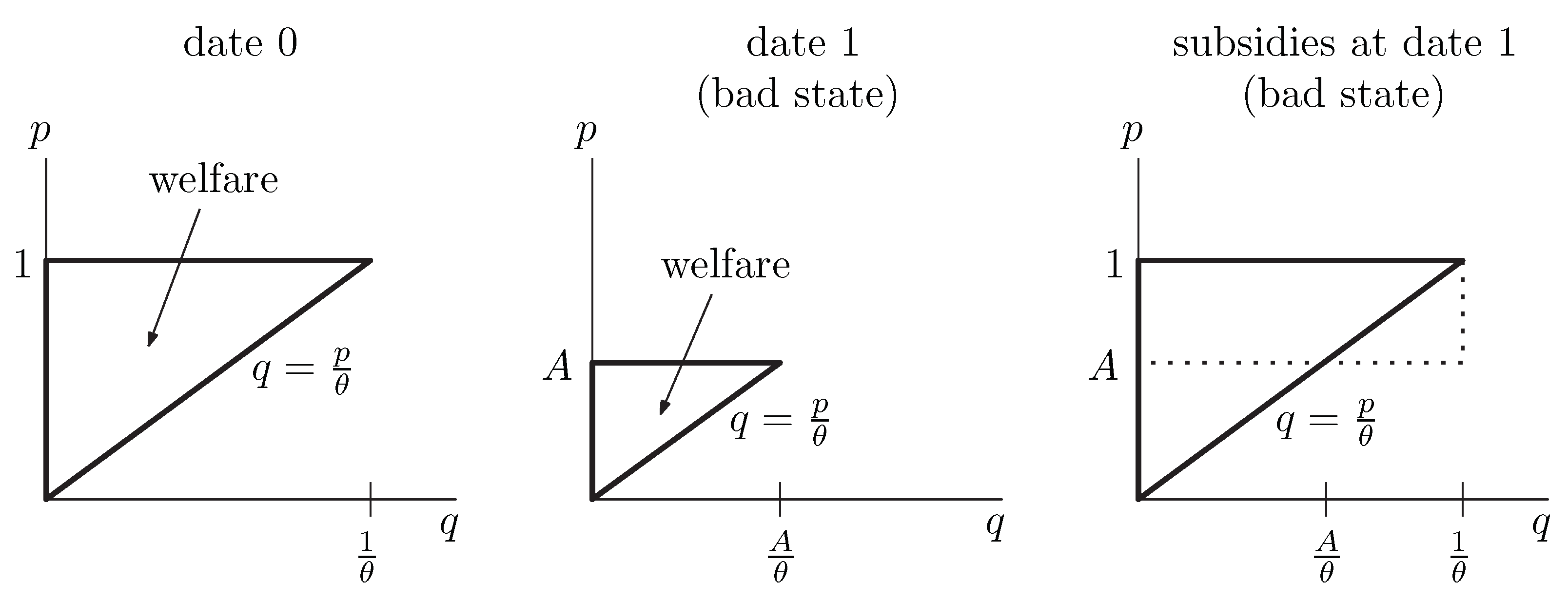

Benchmark model: In the benchmark model without unrealistic optimism, it is well known that the government cannot improve welfare by providing subsidies at that date. For completeness, we first see that the welfare at each date can be described in the first two panels of

Figure 1. Specifically, at date 0, the consumer surplus is 0 because the outputs are sold at a price that is equal to the true valuation of consumers. The producer surplus is equal to

where 1 is the output price at date 0 and

is the marginal cost of production. Hence, the welfare is also equal to

. This producer surplus corresponds to the area of the triangle in the left panel of

Figure 1. The welfare in the good state at date 1 is equal to the welfare at date 0 in the benchmark model and so, we have omitted plotting this case in

Figure 1. Due to the similar argument used for the case at date 0, we see that the welfare in the bad state at date 1 is equal to

, which corresponds to the area of the triangle in the middle panel of

Figure 1.

In this case, suppose the government aims to raise the output price from

A to 1 in the bad state at date 1, by providing subsidies of

per unit output to every consumer who buys the outputs. Then, the consumer surplus is still 0 because each consumer, who values one unit of output as

A, still pays

A from her own pocket. The producer surplus, however, increases from

to

because the output price has been raised to 1 due to subsidies. This producer surplus corresponds to the area of the triangle with the thick edges in the right panel of

Figure 1. In other words, the producer surplus increases by

when the government provide subsidies. But the amount of subsidies provided is equal to

because the total units of the outputs sold are

and the amount of subsidies per unit output is

. These results imply that the welfare of the economy is reduced by

In other words, the sum of the consumer and producer surplus corresponds to the area of the big triangle in the right panel of

Figure 1, whereas the amount of subsides corresponds to the area of the rectangle. Hence, we can reconfirm that the welfare of the economy is lowered when the government subsidizes consumers.

For robustness, even if the government intervenes in the market by directly purchasing the output goods using the money of taxpayers, the welfare cannot be improved. Specifically, suppose that the government directly purchases the output goods at the price of 1 in the bad state at date 1 and then distributes those output goods to consumers. Then, the utility of those consumers who receive the output goods from the government increases by A. But the amount of subsidies spent for one unit of the output was 1. Thus, the welfare actually drops as in the previous case even if the government adopts this alternative intervention policy. In this regard, in what follows, we focus on the first type of intervention policy. Also, note that the first type of intervention policy is more realistic because we can interpret such a policy as tax cuts on consumer goods.

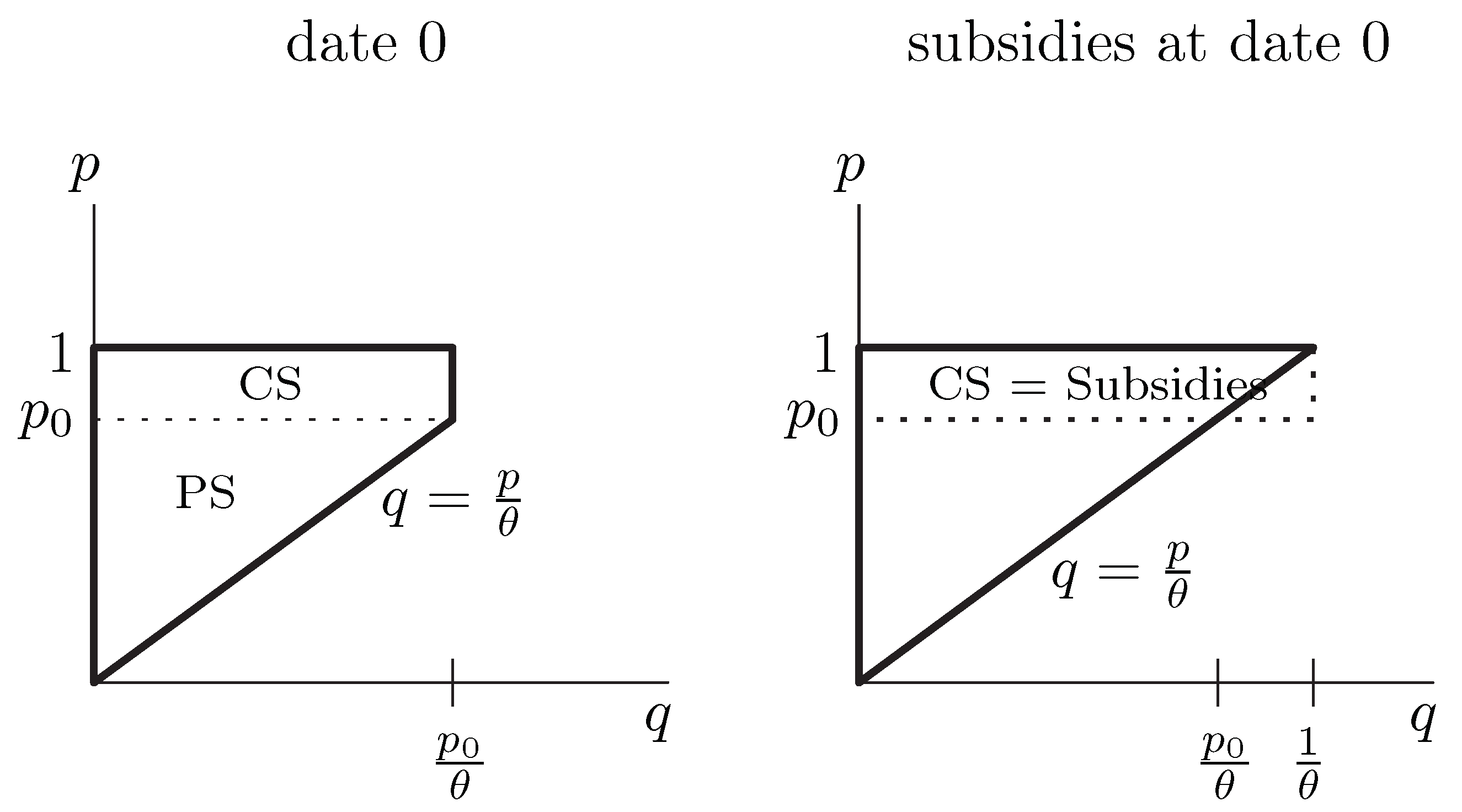

With Unrealistic Optimism: When consumers have unrealistic optimism, we show that government subsidies, if carefully designed, can effectively improve welfare of the economy. To see why, first note that the welfare of this economy at date 0 can be described in

Figure 2.

Specifically, at date 0, the consumer surplus is equal to

because (i) consumers can now purchase one unit of the output goods at the price of

, which is given in (

3), while the true value of the output goods is 1 to those consumers, and (ii) the total units of outputs produced is equal to

. The producer surplus is equal to

, similar to the case in the benchmark model. Thus, the welfare at date 0 is

At date 1, the welfare is the same as that in the benchmark model regardless of whether the aggregate shock hits the economy or not. So, we have omitted to plot this case in

Figure 2.

Now, we consider two possible government intervention policies: one is to provide subsidies at date 0 and the other is to provide subsidies in the bad state at date 1. Under the first policy, the welfare of the economy is equal to

The consumer surplus increases to

because a consumer still needs to pay only

from her own pocket to purchase one unit of the output, but the total units of the outputs produced increases from

to

. This consumer surplus corresponds to the area of the rectangle, enclosed by the solid and dotted lines, in the right panel of

Figure 2. The producer surplus is equal to

because the price has been raised to 1. The producer surplus is depicted by the triangle enclosed by the solid lines in the right panel of the same figure. The amount of subsidies is equal to

because the government subsidizes

per unit of output and the total units of the output produced is

. That is, when the output price is pushed down due to unrealistic optimism, the consumer surplus is the same as the amount of subsidies provided by the government, as shown in the figure. Combining the result in (

4), we see that the welfare increases if the government provides subsidies at date 0, that is, before the aggregate shock occurs. This result is intuitive because when the output price is suppressed due to the cognitive bias of consumers, there is room for the government to intervene in the market and improve welfare. Of course, in the real world, the government should be more cautious because providing subsidies through tax collections may incur some deadweight losses. In this regard, the government must compare the increase in welfare resulting from subsidies to the deadweight losses associated with subsidies and choose to intervene in the market only when the benefits outweights the costs.

Meanwhile, we now show that if the government intervenes in the market by implementing the second type of policy mentioned above, the welfare will still decline as in the benchmark economy. Interestingly, when the government subsidizes consumers at date 1, the output price at date 0 will remain unchanged at

as described in (

3). The reason for this outcome is that each consumer can still pay

A from her own pocket to buy one unit of the output in the bad state at date 1. So, from the date-0 perspective, each consumer still incorrectly believes that she could make profits of

in the bad state at date 1. Hence, the output price at date 0 must stay unchanged at

for the market to clear at date 0. Then, as we have already seen that if the government intervenes in the market at date 1, the welfare will decrease at that date, such an intervention policy cannot improve welfare at any date.

The above two results imply that the government must take the action early, that is, before the aggregate shock hits the economy, to enhance welfare of the economy. Otherwise, the government would only waste the money of taxpayers. In this regard, investigating an optimal timing of the government intervention should be very critical for the entire economy.

3. Concluding Remarks

This paper has explored the economic implications of unrealistic optimism, a cognitive bias that leads individuals to underestimate their susceptibility to negative events while overestimating the vulnerability of others. The existing literature has highlighted the prevalence of unrealistic optimism in diverse contexts and its impact on economic decision-making. To shed a new perspective on the effects of unrealistic optimism on economic decisions and outcomes, we develop a model, in which consumers have unrealistic optimism. Using this model, we show that when consumers have this type of cognitive bias, the economy is more likely to suffer from early recessions and underinvestment. Our key insight is that in the presence of unrealistic optimism among all consumers, the price of output goods must promptly drop to induce consumers, who wrongly believe they can capitalize on an arbitrage opportunity in the future, to be indifferent between purchasing output goods today or at a later time.

Existing papers in the literature generally focus on explaining why economic recoveries after a sudden market crash tend to be sluggish or why bubbles caused by optimism are typically followed by market burst or corrections. However, in our paper, we show that recessions can be accelerated due to unrealistic optimism, which is the unique finding of our paper. In this regard, a more comprehensive investigation is needed to uncover the true origins of recessions and explore potential remedies to deter or mitigate crises.

The paper also discusses the role of government intervention in mitigating the adverse effects of recessions induced by unrealistic optimism. While government subsidies can potentially increase welfare, the timing of government intervention is crucial. That is, our paper shows that a preemptive action that is taken before the occurrence of a negative aggregate shock proves effective in preventing premature recessions, while providing subsidies after the shock occurs will only lead to welfare loss.

It would be worth examining whether the unfavorable impact of unrealistic optimism tends to diminish over time as individuals can gradually learn the true economic states based on their past experience and historical data. Broadly speaking, the existing evidence regarding whether such learning effects can counteract the impact of cognitive bias is inconclusive. While humans do learn not only from their experiences but also from historical data, as intensively studied by Reinhart and Rogoff [

27], people tend to fall victim to the so-called "This time is different" syndrome. That is, this study shows that individuals, including experts, often believe that new situations will bear little similarities to historical patterns, but their beliefs have unfortunately been repeatedly proven wrong. One such example is that, as shown by Malmendier and Nagel [

28], young investors who had not experienced the Great Depression tend to have more optimistic views on stock markets than older generations who lived through that catastrophic period. In this regard, we can argue that unfavorable or irrational outcomes caused by cognitivie biases, including unrealistic optimism, will continue to occur in the future, even if individudals can learn the true states of the economy from their past experiences or past data to some extent. One supporting evidence for this argument is that, as briefly mentioned in the introduction, Gassen et al. [

12] demonstrate the continued prevalence of of unrealistic optimism among individuals through the study on COVID-19 cases. This finding suggests that unrealistic optimism is a deeply ingrained trait of human beings and thereby may persist over time even in the presence of substantial historical data.