Submitted:

24 January 2024

Posted:

26 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Settings

2.2. Study Design and Sampling

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

3.2. COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake

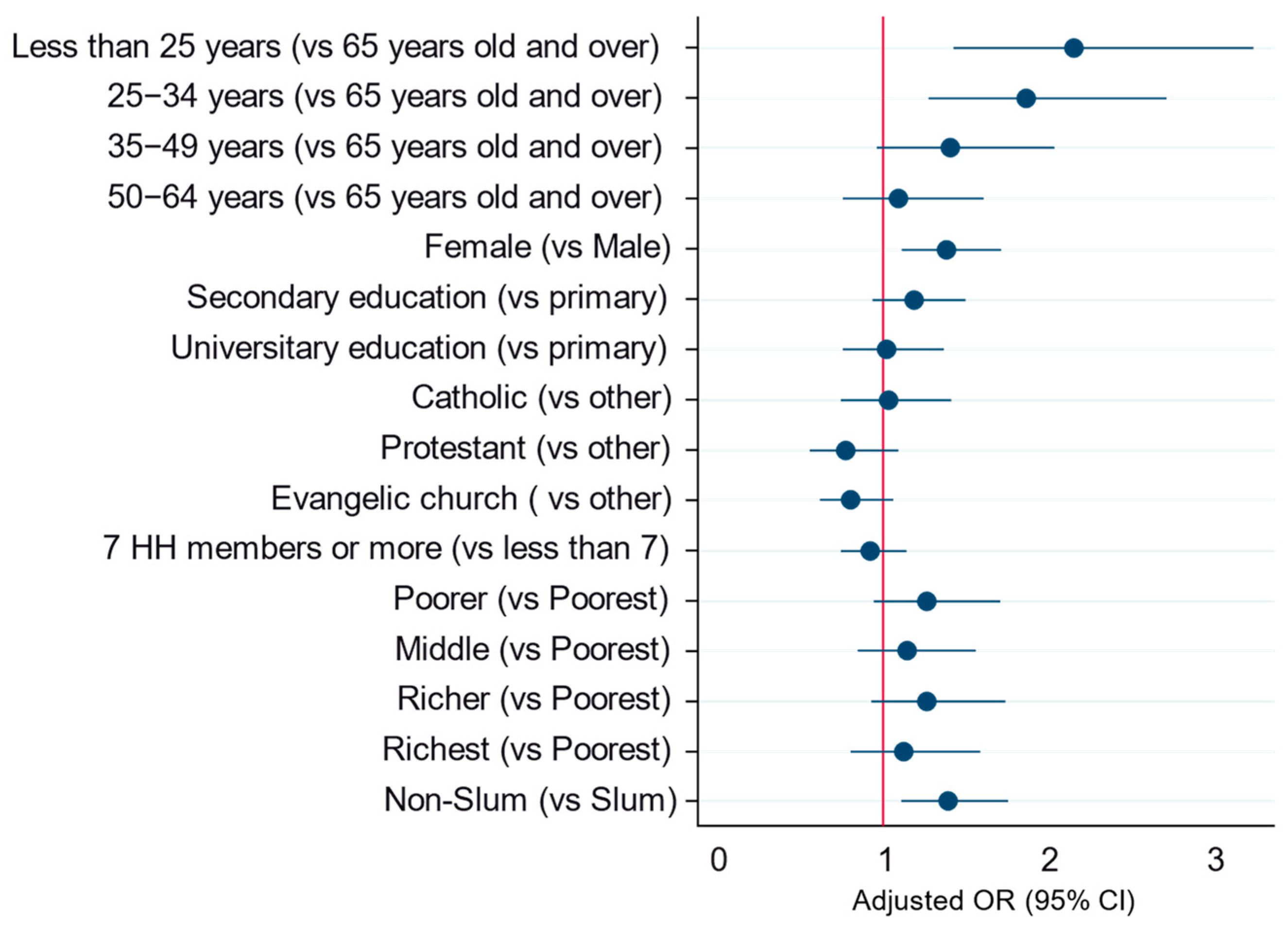

3.3. Hesitancy toward COVID-19 Vaccine

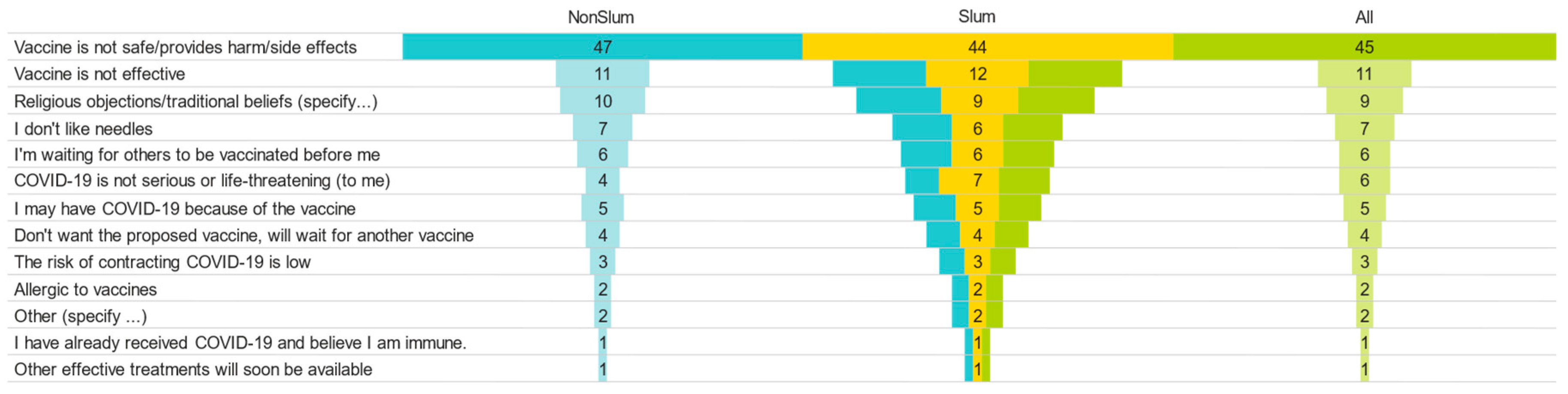

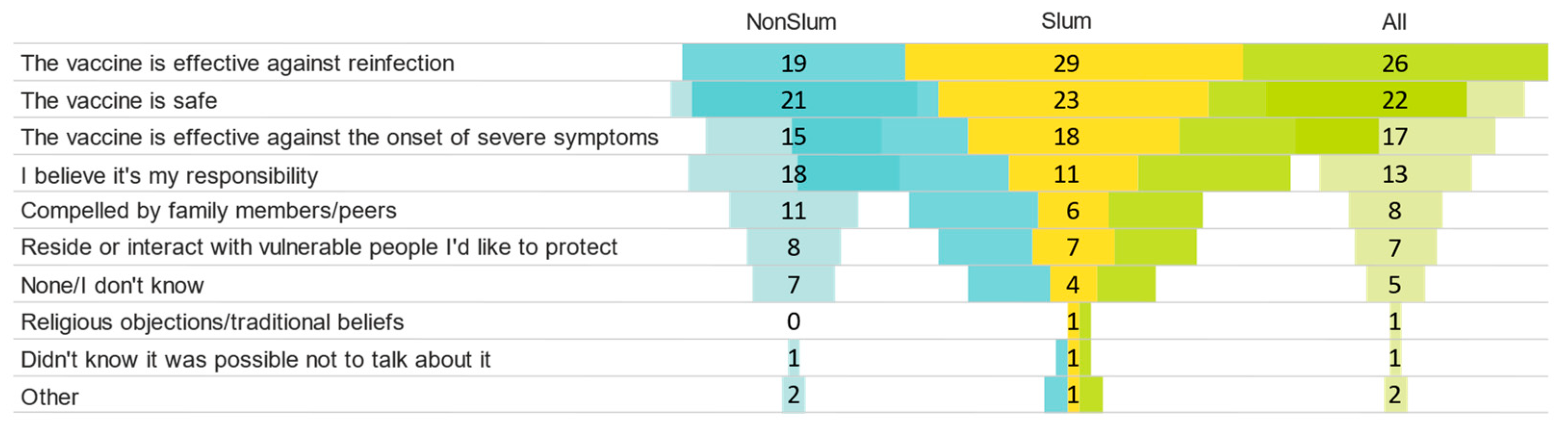

3.4. Reasons of Refusal and Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Mudatsir, M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Southeast Asia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudeimat, Y.; Alenezi, D.; AlHajri, B.; Alfouzan, H.; Almokhaizeem, Z.; Altamimi, S.; Almansouri, W.; Alzalzalah, S.; Ziyab, A.H. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and its related determinants among the general adult population in Kuwait. Med. Princ. Pr. 2021, 30, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Wei, Z.; Pei, S.; Li, S.; Sun, X.; Liu, P. Acceptance and preference for COVID-19 vaccination in health-care workers (HCWs). medRxiv 2020, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biologics, C.; Lancet, T.; Diseases, I.; Journal, N.E.; Lancet, T.; Speed, O.W. A vaccine for SARS-CoV-2: Goals and promises. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 24, 100494. [Google Scholar]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjefte, M.; Ngirbabul, M.; Akeju, O.; Escudero, D.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Wyszynski, D.F.; Wu, J.W. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and mothers of young children: Results of a survey in 16 countries. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Paulami, D.; Octavio Franco, L.; Hanen, S.; Mandal, S.; Sezgin, G.C.; Biswas, K.; Partha Sarathi, N.I.O. Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kreps, S.; Prasad, S.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hswen, Y.; Garibaldi, B.T.; Zhang, B.; Kriner, D.L. Factors Associated With US Adults’ Likelihood of Accepting COVID-19 Vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2025594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.Y.; Cerda, A.A. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine: A multifactorial consideration. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohaithef, M.; Padhi, B.K. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in saudi arabia: A web-based national survey. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qerem, W.A.; Jarab, A.S. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance and Its Associated Factors Among a Middle Eastern Population. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 632914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Milstein, A. Influence of a COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness and safety profile on vaccination acceptance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, 2021726118. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33619178 (accessed on 1 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Batra, K.; Batra, R. A theory-based analysis of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among african americans in the united states: A recent evidence. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; MacGregor, H.; Akello, G.; Babawo, L.; Baluku, M.; Desclaux, A.; Grant, C.; Kamara, F.; Nyakoi, M.; Parker, M.; et al. Vaccine anxieties, vaccine preparedness: Perspectives from Africa in a COVID-19 era. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 298, 114826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Ojji, D.; de Silva, H.A.; MacMahon, S.; Rodgers, A. Polypills for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: A framework for wider use. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditekemena, J.D.; Nkamba, D.M.; Mutwadi, A.; Mavoko, H.M.; Siewe Fodjo, J.N.; Luhata, C.; Obimpeh, M.; Van Hees, S.; Nachega, J.B.; Colebunders, R. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the democratic republic of congo: A cross-sectional survey. Vaccines 2021, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, C.R.; Galvani, A.P. The global impact of disproportionate vaccination coverage on COVID-19 mortality. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1254–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akilimali PZ, Tran NT, Gage AJ. Heterogeneity of Modern Contraceptive Use among Urban Slum and Nonslum Women in Kinshasa, DR Congo: Cross-Sectional Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Sep 6;18(17):9400. [CrossRef]

- https://www.ajol.info/index.php/aamed/article/view/224610.

- Mayala, G.M.; Niangi, L.; Lombela, G.W. The first year of COVID-19 in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Crisis management’s review in a decentralized health system. Ann. Afr. Med., vol. 15, n° 2, Mars 2022.

- Kabamba Nzaji, M.; Kabamba Ngombe, L.; Ngoie Mwamba, G.; Banza Ndala, D.B.; Mbidi Miema, J.; Luhata Lungoyo, C.; Lora Mwimba, B.; Cikomola Mwana Bene, A.; Mukamba Musenga, E. Acceptability of Vaccination Against COVID-19 among Healthcare Workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pragmatic Obs. Res. 2020, 11, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karafillakis, E.; Van Damme, P.; Hendrickx, G.; Larson, H.J. COVID-19 in Europe: New challenges for addressing vaccine hesitancy. Lancet 2022, 399, 699–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewatripont, M. Which policies for vaccine innovation and delivery in Europe? Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2022, 84, 102858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, R.; Yoshioka, T.; Ohfuji, S.; Matsuo, T.; Tabuchi, T. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Associated Factors in Japan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.C.B.C.; Nehab, M.F.; Camacho, K.G.; Reis, A.T.; Junqueira-Marinho, M.d.F.; Abramov, D.M.; de Azevedo, Z.M.A.; de Menezes, L.A.; Salú, M.d.S.; Figueiredo, C.E.d.S.; et al. Low COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Brazil. Vaccine 2021, 39, 6262–6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Rocha, J.V.; Moniz, M.; Gama, A.; Laires, P.A.; Pedro, A.R.; Dias, S.; Leite, A.; Nunes, C. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Cheung, J.K.; Wu, P.; Ni, M.Y.; Cowling, B.J.; Liao, Q. Articles Temporal changes in factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake among adults in Hong Kong: Serial cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Reg. Health West Pacific. 2022, 23, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Kamal, A.-H.M.; Kabir, A.; Southern, D.L.; Khan, S.H.; Hasan, S.M.M.; Sarkar, T.; Sharmin, S.; Das, S.; Roy, T.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, M.F.; Faye, A.; Kane, B.; Diallo, A.I.; Junot, A.; Gaye, I.; Bonnet, E.; Ridde, V. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Senegal: A mixed study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2060020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dereje, N.; Tesfaye, A.; Tamene, B.; Alemeshet, D.; Abe, H.; Tesfa, N.; Gideon, S.; Biruk, T.; Lakew, Y. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A mixed-method study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e052432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertwee, E.; Simas, C.; Larson, H.J. An epidemic of uncertainty: Rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Lima, G.; Cha, M.; Cha, C.; Kulshrestha, J.; Ahn, Y.-Y.; Varol, O. Misinformation, believability, and vaccine acceptance over 40 countries: Takeaways from the initial phase of the COVID-19 infodemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No Slum | Slum | Ensemble | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age | 0.299 | ||||||

| <25 | 94 | 14.7 | 238 | 17.6 | 332 | 16.6 | |

| 25–34 | 189 | 29.5 | 387 | 28.6 | 576 | 28.9 | |

| 35–49 | 180 | 28.1 | 396 | 29.2 | 576 | 28.9 | |

| 50–64 | 112 | 17.5 | 221 | 16.3 | 333 | 16.7 | |

| ≥65 | 66 | 10.3 | 112 | 8.3 | 178 | 8.9 | |

| Gender | 0.492 | ||||||

| Male | 196 | 30.0 | 430 | 31.5 | 626 | 31.0 | |

| Female | 458 | 70.0 | 936 | 68.5 | 1394 | 69.0 | |

| Level of Education | <0.001 | ||||||

| None/Primary School | 110 | 16.9 | 592 | 43.4 | 702 | 34.8 | |

| Secondary School | 299 | 45.9 | 570 | 41.8 | 869 | 43.1 | |

| University/High | 243 | 37.3 | 202 | 14.8 | 445 | 22.1 | |

| Religion of respondent | <0.001 | ||||||

| Catholic | 160 | 24.5 | 228 | 16.7 | 388 | 19.2 | |

| Protestant | 111 | 17.0 | 172 | 12.6 | 283 | 14.0 | |

| Revival Church | 284 | 43.4 | 699 | 51.2 | 983 | 48.7 | |

| Others | 99 | 15.1 | 267 | 19.5 | 366 | 18.1 | |

| Employment | <0.001 | ||||||

| No occupation/housewife/student or pupil | 313 | 47.9 | 683 | 50.0 | 996 | 49.3 | |

| Public sector employee with a regular monthly salary | 84 | 12.8 | 122 | 8.9 | 206 | 10.2 | |

| Private sector employee with a regular monthly salary | 41 | 6.3 | 65 | 4.8 | 106 | 5.2 | |

| Self-employed in the private sector (self-employed) | 119 | 18.2 | 170 | 12.4 | 289 | 14.3 | |

| Worker in the informal sector and small trade | 71 | 10.9 | 262 | 19.2 | 333 | 16.5 | |

| Agropastoral and fishing | 3 | 0.5 | 12 | 0.9 | 15 | 0.7 | |

| Other | 23 | 3.5 | 52 | 3.8 | 75 | 3.7 | |

| Household size | <0.001 | ||||||

| ≤6 | 548 | 83.8 | 966 | 70.7 | 1514 | 75.0 | |

| ≥7 | 106 | 16.2 | 400 | 29.3 | 506 | 25.0 | |

| Sufficient living space (not overcrowded) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Overcrowding | 875 | 29.1 | 3167 | 42.9 | 4042 | 39.0 | |

| Sufficient Living Area | 2127 | 70.9 | 4208 | 57.1 | 6335 | 61.0 | |

| Income Quintiles | <0.001 | ||||||

| Very low | 44 | 6.7 | 360 | 26.4 | 404 | 20.0 | |

| Low | 74 | 11.3 | 330 | 24.2 | 404 | 20.0 | |

| Middle | 124 | 19.0 | 281 | 20.6 | 405 | 20.0 | |

| High | 159 | 24.3 | 244 | 17.9 | 403 | 20.0 | |

| Very High | 253 | 38.7 | 151 | 11.1 | 404 | 20.0 | |

| No | Yes | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age | <0.001 | ||||

| <25 | 85 | 25.6 | 247 | 74.4 | |

| 25–34 | 161 | 28.0 | 415 | 72.0 | |

| 35–49 | 199 | 34.5 | 377 | 65.5 | |

| 50–64 | 137 | 41.1 | 196 | 58.9 | |

| ≥65 | 76 | 42.7 | 102 | 57.3 | |

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 242 | 38.7 | 384 | 61.3 | |

| Female | 424 | 30.4 | 970 | 69.6 | |

| Level of Education | 0.023 | ||||

| None/Primary School | 256 | 36.5 | 446 | 63.5 | |

| Secondary School | 260 | 29.9 | 609 | 70.1 | |

| University/High | 148 | 33.3 | 297 | 66.7 | |

| Religion of respondent | 0.674 | ||||

| Catholic | 128 | 33.0 | 260 | 67.0 | |

| Protestant | 97 | 34.3 | 186 | 65.7 | |

| Revival Church | 330 | 33.6 | 653 | 66.4 | |

| Others | 111 | 30.3 | 255 | 69.7 | |

| Employment | 0.262 | ||||

| No occupation/housewife/student or pupil | 306 | 30.7 | 690 | 69.3 | |

| Public sector employee with a regular monthly salary | 75 | 36.4 | 131 | 63.6 | |

| Private sector employee with a regular monthly salary | 39 | 36.8 | 67 | 63.2 | |

| Self-employed in the private sector (self-employed) | 99 | 34.3 | 190 | 65.7 | |

| Worker in the informal sector and small trade | 121 | 36.3 | 212 | 63.7 | |

| Agropastoral and fishing | 6 | 40.0 | 9 | 60.0 | |

| Other | 20 | 26.7 | 55 | 73.3 | |

| Household size | 0.184 | ||||

| ≤6 | 487 | 32.2 | 1027 | 67.8 | |

| ≥7 | 179 | 35.4 | 327 | 64.6 | |

| Sufficient living space (not overcrowded) | 0.770 | ||||

| Overcrowding | 197 | 33.4 | 392 | 66.6 | |

| Sufficient Living Area | 469 | 32.8 | 962 | 67.2 | |

| Income Quintiles | 0.158 | ||||

| Very low | 154 | 38.1 | 250 | 61.9 | |

| Low | 128 | 31.7 | 276 | 68.3 | |

| Middle | 132 | 32.6 | 273 | 67.4 | |

| High | 122 | 30.3 | 281 | 69.7 | |

| Very High | 130 | 32.2 | 274 | 67.8 | |

| Slum Household | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 183 | 28.0 | 471 | 72.0 | |

| Yes | 483 | 35.4 | 883 | 64.6 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).