1. Introduction

Discovering new bioinert or bioactive coatings for conventionally-used joint implants, made from cobalt (Co) – chromium (Cr) alloys, magnesium (Mg) alloys, stainless steel or titanium (Ti) alloys, is still of high importance. For example, new coatings can provide improved chemical stability, strengthened corrosion resistance, appropriate physiological mechanical properties, better support for osseointegration or increased microbial resistance for current orthopaedic implants (for a review, see [

1,

2,

3]). One of the most important properties of joint replacements is high wear resistance, which can be obtained by creating a stable surface layer on the material. The stable surface layer plays a key role in preventing the release of metal ions and wear debris from an implant, which can otherwise later result in inflammation of the surrounding tissue followed by osteolysis and implant failure/loosening (for a review, see [

4,

5].

Diamond-like carbon (DLC) layers have been used for coating orthopaedic implants (e.g. joint replacements, medical wires, screws) due to their hardness, high corrosion resistance, low friction, high wear resistance, and high biocompatibility (for a review, see [

6,

7,

8]. Moreover, due to their chemical inertness, surface smoothness and hydrophobicity, resulting in low thrombogenicity, DLC coatings have been widely explored for cardiovascular stents, heart valve prosthesis, and other cardiovascular devices (for a review, see [

6,

7,

8]. Nevertheless, the DLC layer itself is burdened with instability in the aqueous environment and poor substrate adhesion [

9]. These disadvantages can be overcome by using suitable interlayers or by doping DLC with specific chemical elements during fabrication (for a review, see [

6,

8]. Ti is known to possess superior biocompatibility properties, and it is therefore a commonly used material for dental implants and medical devices (for a review, see [

10]. The addition of Ti or Cr to DLC has been reported to increase the adhesion of DLC layers to an underlying substrate, such as Si(100) wafers, 316 L stainless steel, or Ti6Al4V [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The addition of Ti to DLC also improves other mechanical properties, such as the elastic modulus, hardness, and surface roughness of the coating [

12,

13,

15]. Similarly, our previous studies on the fabrication of Ti-DLC layers have shown an increasing critical load and increasing roughness as the Ti content increases, along with the Young’s modulus of the Ti-DLC being closer to that of the cortical bone, in comparison to the results when pure DLC layers are used [

13]. The reported properties have depended on the specific Ti content and fabrication techniques, such as dual pulsed laser deposition (dual PLD) or pulsed laser deposition combined with magnetron sputtering (PLD + MS) [

13,

15]. In addition to the improved physicochemical properties, high initial biocompatibility of Ti-DLC layers doped with various contents of Ti has been reported by our previous studies [

13,

15] and also by other researchers [

12].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which are able to undergo osteogenic and/or chondrogenic differentiation, play a key role in bone regeneration and bone healing/repair processes (for a review, see [

16]. Under physiological conditions

in vivo, MSCs are recruited to the damaged area from the surrounding tissue (mainly from the periosteum, the endosteum, and the bone marrow cavity) as well as from peripheral circulation [

16]. The MSCs involved in bone repair are modulated by many signalling pathways, which can be further advantageously used in regenerative medicine to stimulate the mobilization and homing of the MSCs (for a review, see [

17]. For decades, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (bmMSCs) have been widely investigated, and these cells have been considered as a gold standard for bone cell-based therapies. However, MSCs can also be harvested from other specific tissues such as adipose tissue (ADSCs), dental pulp, peripheral blood, amniotic fluid, or placenta (for a review, see [

18]). Among these cells/tissues, ADSCs are one of the most promising cell types for MSC-based bone regeneration therapies, due to their easy accessibility in relatively large quantities, high proliferative capacity, high osteogenic differentiation potential, osteoinductive and immunomodulation properties (for a review, see [

19]. These superior characteristics rank ADSCs equal to or even higher than bmMSCs for further routine autologous or allogenic clinical applications in bone tissue engineering. However, previous and current clinical trials focused on the usage of ADSCs in bone repair have so far resulted in ambiguous outcomes, and specific cell characterization therefore needs to be performed to allow comparisons of the results/outcomes that are obtained (for a review, see [

20]). To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive study covering the interaction of variably Ti-doped DLC coatings with adult MSCs has been performed. Similar Ti-DLC coatings have been fabricated and characterized in the past, and their basic cytocompatibility has been tested with the Saos-2 cell line, i.e. human osteoblast-like cells derived from osteosarcoma, by our group [

13,

15]. Based on previous promising results, the current study aims to provide a broader set of

in vitro experiments concerning the adhesion, growth and differentiation of primary or low-passaged human osteogenic cells, and thus to ensure the suitability of Ti-DLC layers for orthopaedic implants. In addition, our study aims to elucidate the potential influence of an increasing Ti content on cell behaviour. For this purpose, multipotent MSCs that are physiologically involved in bone healing or that are present in a surrounding tissue were chosen. Specifically, cell-material interactions of two types of adult MSCs (i.e. ADSCs and bmMSCs) are studied. Detailed physicochemical characterization of the prepared Ti-DLC layers was performed prior to the cell experiments.

5. Conclusions

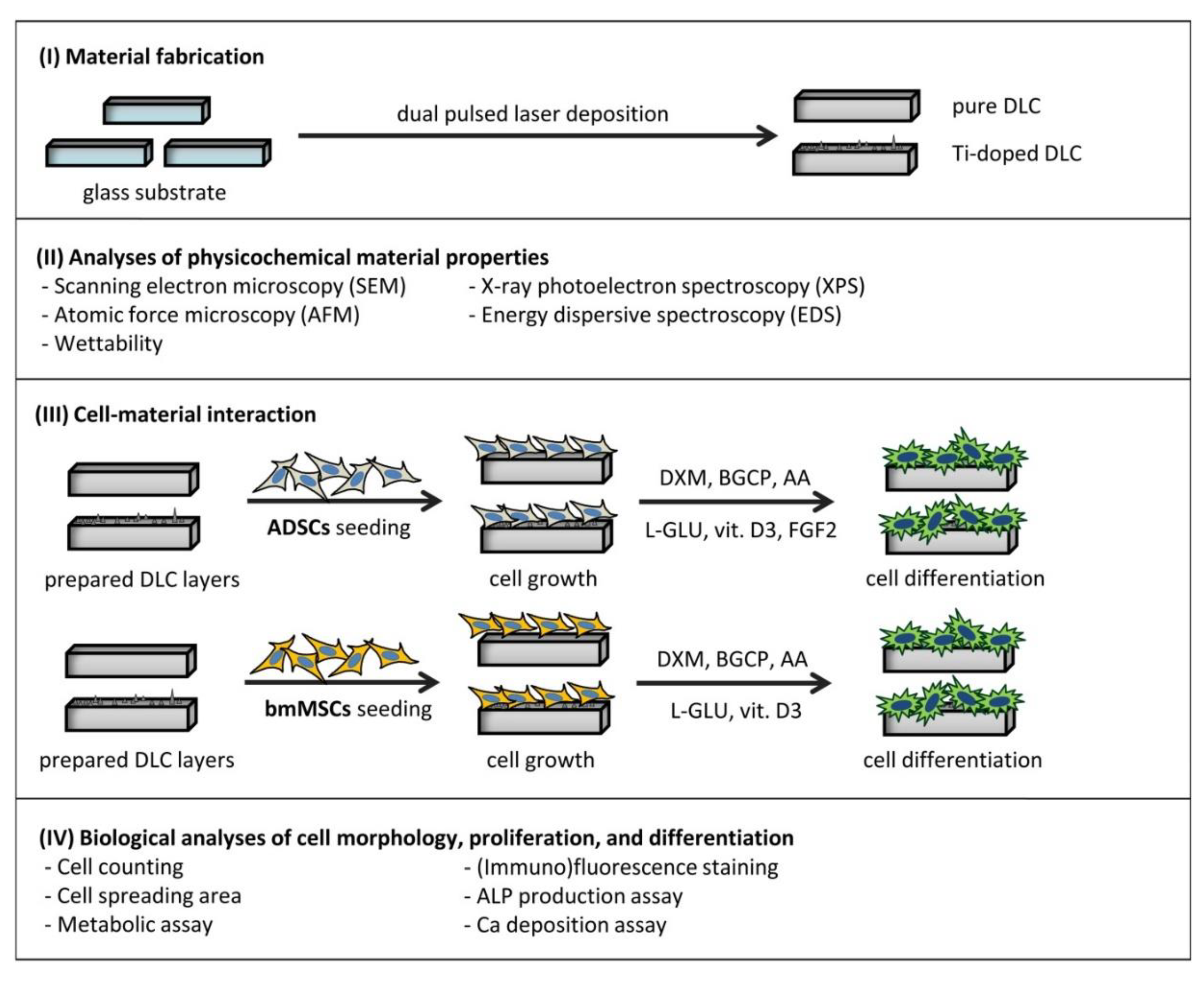

In the present study, Ti-doped DLC layers with variable Ti content were prepared by dual pulsed laser deposition, and the cytocompatibility of the layers was proved in vitro using two mesenchymal stem cell types: ADSCs and bmMSCs. A complex comparative study of the two mesenchymal stem cell types was focused on material properties, cell adhesion, proliferation and osteogenic differentiation.

The physicochemical characterization of Ti-doped DLC layers showed an increased content of both Ti and O, contact angle and roughness, and decreased SFE with increased Ti concentration from DLC_2.1Ti to DLC_12.8Ti.

Ti-doped DLC layers with their nanostructured surface provided a suitable substrate for initial cell adhesion and spreading, and both ADSCs and bmMSCs maintained their typical spindle-shaped or polygonal-shaped morphology after adhesion and spreading.

The cell proliferation, measured as the density of the cell population and the metabolic activity of the cells, of both ADSCs and bmMSCs on Ti-DLC layers, was similar or was even higher than on control glass and PS during the three-week cell culture.

The ADSCs and bmMSCs were successfully differentiated towards osteoblasts on all tested materials. The Ti levels did not significantly influence the rate of osteogenic differentiation in most of the tested parameters, and the differentiation was mainly driven chemically by the composition of the medium.

The comparison between the two cell types revealed that the bmMSCs exhibited greater initial proliferation potential and an earlier onset of osteogenic differentiation, which was proved by greater ALP activity on days 7 and 14, greater osteocalcin production on day 14, and earlier and greater calcium deposition in comparison with ADSCs.

The ADSCs proliferated steadily over a period of 21 days and produced more collagen than the bmMSCs on day 14. In addition, ADSCs seemed to be more sensitive to the Ti content, as ADSCs showed a slightly greater formation of focal adhesions, and evinced greater metabolic activity, collagen production and Ca deposition with increasing Ti content in the layer. The bmMSCs were less sensitive to Ti content and more uniform results were obtained.

Based on our results combining the material characterization and in vitro biological analyses, we would suggest using Ti-DLC layers containing 2.1-12.8 at.% of Ti for further in vivo animal studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T., E.F., L.B.; methodology, M.T., M.Z., E.F., L.B.; validation, T.S.; formal analysis, M.T., E.F.; investigation, M.T., E.F., P.S., N.K.S., T.S., M.Z.; resources, L.B., T.K., E.F..; data curation, P.S., E.F., M.T., T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T., E.F., M.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.T., E.F., L.B., N.K.S., T.K..; visualization, M.T., E.F., T.S.; supervision, L.B..; project administration, E.F, L.B..; funding acquisition, E.F., L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at Na Bulovce Hospital in Prague (August 21, 2014; No. 11.6.2019/9150/EK-Z, 2019, and No. 16.3.2023/10795/EK-Z, 2023) for studies involving humans. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Figure 1.

SEM images of pure DLC and of DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at. % of Ti). Scale bar = 50 µm (a) and 10 µm (b).

Figure 1.

SEM images of pure DLC and of DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at. % of Ti). Scale bar = 50 µm (a) and 10 µm (b).

Figure 2.

AFM scans of glass, of pure DLC, and of DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at. % of Ti). A region of 1 µm x 1 µm is depicted. The mean roughness value (Ra) represents the average surface roughness in nm.

Figure 2.

AFM scans of glass, of pure DLC, and of DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at. % of Ti). A region of 1 µm x 1 µm is depicted. The mean roughness value (Ra) represents the average surface roughness in nm.

Figure 3.

The mass concentration of Ti and C elements determined by EDS on the surface of the tested materials. The Mann-Whitney test was applied to compare each material separately with the control sample (DLC_pure). The pairs with p-values ≤ 0.05 (n=5) are marked with “*”.

Figure 3.

The mass concentration of Ti and C elements determined by EDS on the surface of the tested materials. The Mann-Whitney test was applied to compare each material separately with the control sample (DLC_pure). The pairs with p-values ≤ 0.05 (n=5) are marked with “*”.

Figure 4.

The densities of ADSCs (A) and of bmMSCs (B) on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti), and on polystyrene (PS) on days 1, 7, 14 and 21. The data are expressed as mean + SD. ANOVA, Student-Newman-Keuls method. The statistical comparison among the samples was made on cells on the same day of the culture. The statistical significance (p≤0.001) is specified above the columns (ADSCs (A): * means a lower value than on glass, 2.1 and 12.8 at.%, bmMSCs (B): * means a higher value than on glass, 0.4 and 12.8 at.%, and on PS; # means a lower value than on 0.4, 2.1, 3.7 and 6.6 at.%; § means a lower value than on 3.7 and 6.6 at.%; ¶ means a lower value than on 3.7 at.%).

Figure 4.

The densities of ADSCs (A) and of bmMSCs (B) on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti), and on polystyrene (PS) on days 1, 7, 14 and 21. The data are expressed as mean + SD. ANOVA, Student-Newman-Keuls method. The statistical comparison among the samples was made on cells on the same day of the culture. The statistical significance (p≤0.001) is specified above the columns (ADSCs (A): * means a lower value than on glass, 2.1 and 12.8 at.%, bmMSCs (B): * means a higher value than on glass, 0.4 and 12.8 at.%, and on PS; # means a lower value than on 0.4, 2.1, 3.7 and 6.6 at.%; § means a lower value than on 3.7 and 6.6 at.%; ¶ means a lower value than on 3.7 at.%).

Figure 5.

The metabolic activity of ADSCs (A) and of bmMSCs (B) on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti), and on polystyrene (PS) on days 1, 7, 14 and 21. The data (n=3) are expressed as mean + SD. ANOVA, Student-Newman-Keuls method. The statistical comparison among the samples was made on cells on the same day of the culture. The statistical significance (p<0.05) is specified above the columns (ADSCs (A): * means a higher value than on 6.6 and 12.8 at.%; “all” means a statistically different value from all other samples on the specific day of the culture, bmMSCs (B): # means a significantly different value compared to PS, “all” means a statistically different value from all other samples on the specific day of the culture).

Figure 5.

The metabolic activity of ADSCs (A) and of bmMSCs (B) on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti), and on polystyrene (PS) on days 1, 7, 14 and 21. The data (n=3) are expressed as mean + SD. ANOVA, Student-Newman-Keuls method. The statistical comparison among the samples was made on cells on the same day of the culture. The statistical significance (p<0.05) is specified above the columns (ADSCs (A): * means a higher value than on 6.6 and 12.8 at.%; “all” means a statistically different value from all other samples on the specific day of the culture, bmMSCs (B): # means a significantly different value compared to PS, “all” means a statistically different value from all other samples on the specific day of the culture).

Figure 6.

The morphology and cell spreading of ADSCs and bmMSCs on day 1 after seeding on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti), and on polystyrene (PS). The cell cytoplasm was visualized by Texas Red C2-maleimide (red colour) and the cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue colour). Representative images were selected. IX71 Olympus microscope, DP71 digital camera, objective magnification × 20, scale bar 100 μm. The cell spreading area was analysed by Atlas software. Data are presented as box plots with a median line, the outer edges representing the 1st and 3rd quartile, the whiskers depicting the 5th and the 95th percentile.

Figure 6.

The morphology and cell spreading of ADSCs and bmMSCs on day 1 after seeding on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti), and on polystyrene (PS). The cell cytoplasm was visualized by Texas Red C2-maleimide (red colour) and the cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue colour). Representative images were selected. IX71 Olympus microscope, DP71 digital camera, objective magnification × 20, scale bar 100 μm. The cell spreading area was analysed by Atlas software. Data are presented as box plots with a median line, the outer edges representing the 1st and 3rd quartile, the whiskers depicting the 5th and the 95th percentile.

Figure 7.

The fluorescence staining of F-actin (red) and vinculin (green) in ADSCs on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti) on day 3. Cell nuclei are counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Representative images were selected. Olympus IX71 microscope, IX71 digital camera, objective magnification ×20, scale bar 100 µm.

Figure 7.

The fluorescence staining of F-actin (red) and vinculin (green) in ADSCs on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti) on day 3. Cell nuclei are counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Representative images were selected. Olympus IX71 microscope, IX71 digital camera, objective magnification ×20, scale bar 100 µm.

Figure 8.

The immunofluorescence staining of type I collagen and osteocalcin (both markers in green colour) in ADSCs on glass, on pure DLC, and on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti) on days 14 and 21. In the collagen-stained cells, the cell nuclei are counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Representative images were selected. Olympus IX71 microscope, IX71 digital camera, objective magnification ×20, scale bar 100 µm.

Figure 8.

The immunofluorescence staining of type I collagen and osteocalcin (both markers in green colour) in ADSCs on glass, on pure DLC, and on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti) on days 14 and 21. In the collagen-stained cells, the cell nuclei are counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Representative images were selected. Olympus IX71 microscope, IX71 digital camera, objective magnification ×20, scale bar 100 µm.

Figure 9.

The immunofluorescence staining of type I collagen (green colour on day 14 and red colour on day 21) and of osteocalcin (green colour) in bmMSCs on glass, on pure DLC, and on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti) on days 14 and 21. Cell nuclei are counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Representative images were selected. Olympus IX71 microscope, IX71 digital camera, objective magnification ×20, scale bar 100 µm.

Figure 9.

The immunofluorescence staining of type I collagen (green colour on day 14 and red colour on day 21) and of osteocalcin (green colour) in bmMSCs on glass, on pure DLC, and on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti) on days 14 and 21. Cell nuclei are counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Representative images were selected. Olympus IX71 microscope, IX71 digital camera, objective magnification ×20, scale bar 100 µm.

Figure 10.

The fluorescence intensity of type I collagen and osteocalcin in ADSCs and bmMSCs on glass, on pure DLC, and on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti) on days 14 and 21. The fluorescence intensity is related to the cell number. The data are expressed as mean + SD. ANOVA, Holm-Sidak method. The statistical comparison among the samples was made on cells on the same day of the culture. The statistical significance (p≤0.001) is specified above the columns by the numbers of the compared experimental groups.

Figure 10.

The fluorescence intensity of type I collagen and osteocalcin in ADSCs and bmMSCs on glass, on pure DLC, and on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti) on days 14 and 21. The fluorescence intensity is related to the cell number. The data are expressed as mean + SD. ANOVA, Holm-Sidak method. The statistical comparison among the samples was made on cells on the same day of the culture. The statistical significance (p≤0.001) is specified above the columns by the numbers of the compared experimental groups.

Figure 11.

The ALP activity of ADSCs and bmMSCs on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti), and on polystyrene (PS) on days 7, 14 and 21. The data are expressed as mean + SD. ANOVA, Student-Newman-Keuls method. The statistical comparison among the samples was made on cells on the same day of the culture. The statistical significance (p≤0.001) is specified above the columns (* means a lower value than on 0.4, 2.1 and 3.7 at.%; # means a lower value than on pure DLC, 2.1 and 12.8 at.%; ¶ means a higher value than on glass and PS; £ means a higher value than on PS; § means a higher value than on 0.4, 3.7 and 12.8 at.%; “all” means a statistically different value from all other samples on the specific day of the culture).

Figure 11.

The ALP activity of ADSCs and bmMSCs on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at.% of Ti), and on polystyrene (PS) on days 7, 14 and 21. The data are expressed as mean + SD. ANOVA, Student-Newman-Keuls method. The statistical comparison among the samples was made on cells on the same day of the culture. The statistical significance (p≤0.001) is specified above the columns (* means a lower value than on 0.4, 2.1 and 3.7 at.%; # means a lower value than on pure DLC, 2.1 and 12.8 at.%; ¶ means a higher value than on glass and PS; £ means a higher value than on PS; § means a higher value than on 0.4, 3.7 and 12.8 at.%; “all” means a statistically different value from all other samples on the specific day of the culture).

Figure 12.

The calcium deposition of ADSCs and bmMSCs on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at. % of Ti), and on polystyrene (PS) on days 14 and 21. The data are expressed as mean + SD. ANOVA, Student-Newman-Keuls method. The statistical comparison among the samples was made on cells on the same day of the culture. The statistical significance (p≤0.05) is specified above the columns (¶ means a higher value than on glass and 0.4 at. %; § means a higher value than on glass; * means a higher value than on glass, pure DLC, and 0.4 at. %; # means a higher value than on glass, pure DLC, and 0.4-3.7 at. %; £ means a higher value than on glass and pure DLC; “all” means a statistically different value from all other samples on the specific day of the culture).

Figure 12.

The calcium deposition of ADSCs and bmMSCs on glass, on pure DLC, on DLC doped with Ti (0.4, 2.1, 3.7, 6.6, 12.8 at. % of Ti), and on polystyrene (PS) on days 14 and 21. The data are expressed as mean + SD. ANOVA, Student-Newman-Keuls method. The statistical comparison among the samples was made on cells on the same day of the culture. The statistical significance (p≤0.05) is specified above the columns (¶ means a higher value than on glass and 0.4 at. %; § means a higher value than on glass; * means a higher value than on glass, pure DLC, and 0.4 at. %; # means a higher value than on glass, pure DLC, and 0.4-3.7 at. %; £ means a higher value than on glass and pure DLC; “all” means a statistically different value from all other samples on the specific day of the culture).

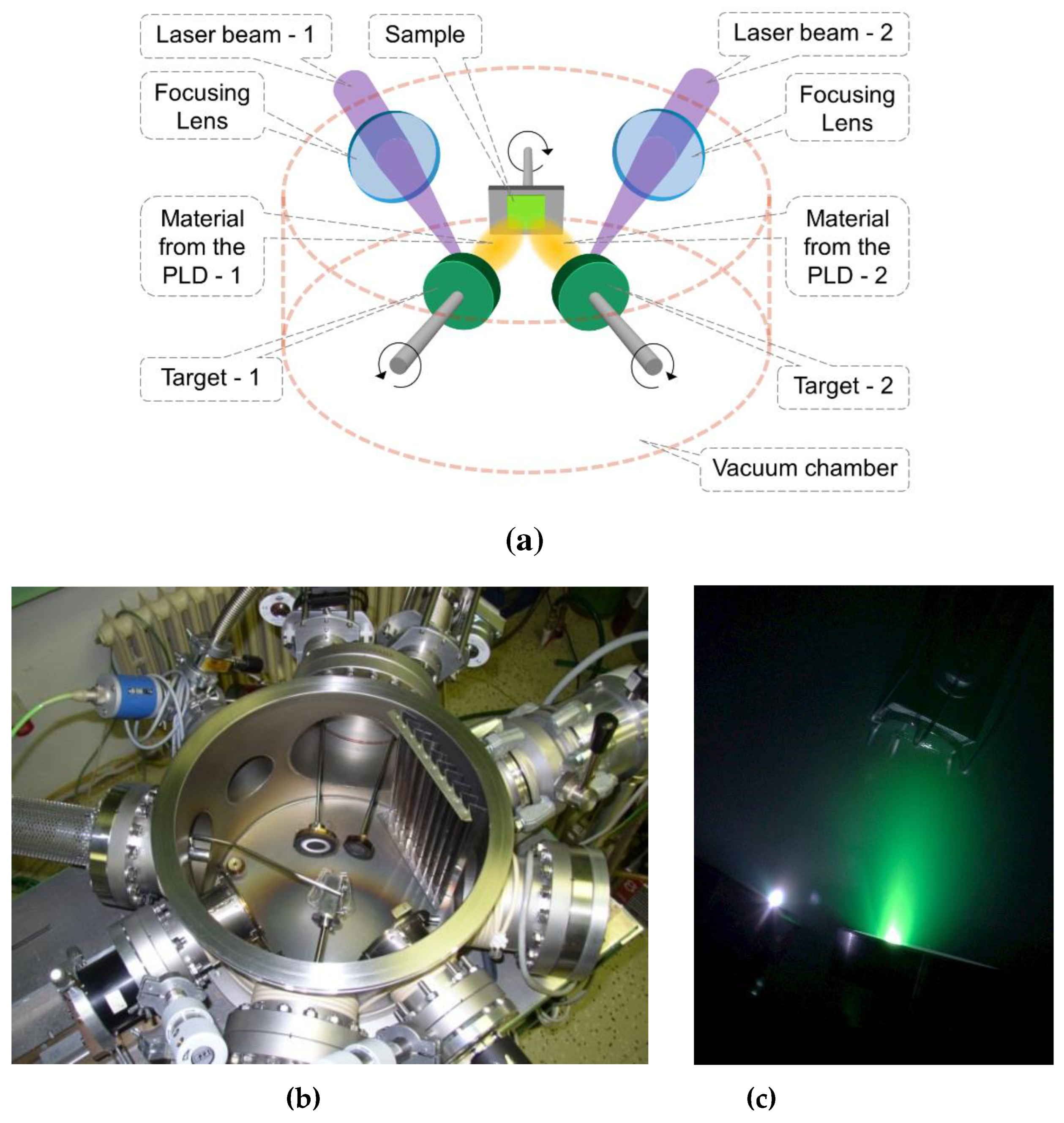

Figure 13.

a) Scheme of dual PLD using two lasers and two targets, b) photo of the deposition chamber, c) photo of the deposition process.

Figure 13.

a) Scheme of dual PLD using two lasers and two targets, b) photo of the deposition chamber, c) photo of the deposition process.

Scheme 1.

Scheme of the experimental work.

Scheme 1.

Scheme of the experimental work.

Table 1.

Contact angle and surface energy values.

Table 1.

Contact angle and surface energy values.

| Sample |

Contact angle (°) |

Surface energy (mN/m) |

| Water |

glycerol |

Total |

| Glass |

45.6 ± 2.5 * |

37.7 ± 1.2 * |

53.0 ± 7.22 * |

| DLC_pure |

76.8 ± 1.4 |

48.3 ± 5.0 |

59.0 ± 13.53 |

| DLC_0.4Ti |

27.7 ± 3.1 * |

55.1 ± 1.0 * |

90.3 ± 5.98 * |

| DLC_2.1Ti |

78.0 ± 0.9 |

77.3 ± 1.9 * |

26.6 ± 4.68 * |

| DLC_3.7Ti |

78.4 ± 1.7 |

77.9 ± 3.0 * |

26.4 ± 7.73 * |

| DLC_6.6Ti |

80.5 ± 3.4 |

68.7 ± 1.2 * |

30.1 ± 9.54 * |

| DLC_12.8Ti |

86.3 ± 1.5 * |

89.0 ± 3.8 * |

21.7 ± 7.68 * |

Table 2.

Deposition parameters and the original measured titanium content of the DLC layers [

13,

15].

Table 2.

Deposition parameters and the original measured titanium content of the DLC layers [

13,

15].

| Sample |

Laser rate [Hz] |

Titanium content [at.%]a

|

| |

L1 |

L2 |

Rc |

Sp |

| DLC_pure |

26 |

- |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| DLC_0.4Ti |

26 |

1 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

| DLC_2.1Ti |

25 |

3 |

2.1 |

3.3 |

| DLC_3.7Ti |

25 |

5 |

3.7 |

5.2 |

| DLC_6.6Ti |

26 |

11 |

6.6 |

10.1 |

| DLC_12.8Ti |

18 |

23 |

12.8 |

24.5 |

Table 3.

Fluorescent dyes and antibodies used in the study.

Table 3.

Fluorescent dyes and antibodies used in the study.

| Type, Name |

Supplier |

Cat. No. |

Concentration |

| Texas Red C2-maleimide |

Invitrogen |

T6008 |

10 ng/mL |

| Phalloidin-TRITC |

Sigma-Aldrich |

P1951 |

5 μg/mL |

| Hoechst 33258 |

Sigma-Aldrich |

B1155 |

10 μg/mL |

Anti-vinculin (mouse)

Anti-type I collagen (rabbit)

Anti-type I collagen (mouse) |

Sigma-Aldrich

CosmoBio

Sigma-Aldrich |

V9131

LSL-LB-1197

C2456 |

1:200

1:200

1:200 |

| Anti-osteocalcin (rabbit) |

Peninsula Laboratories |

T-4743 |

1:200 |

| Anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 |

Thermo Fisher Scientific |

A11070 |

1:400 |

Anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 546

Anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 488

Anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 546 |

Thermo Fisher Scientific

Thermo Fisher Scientific

Thermo Fisher Scientific |

A11010

A11017

A11003 |

1:400

1:400

1:400 |