Submitted:

09 February 2024

Posted:

12 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

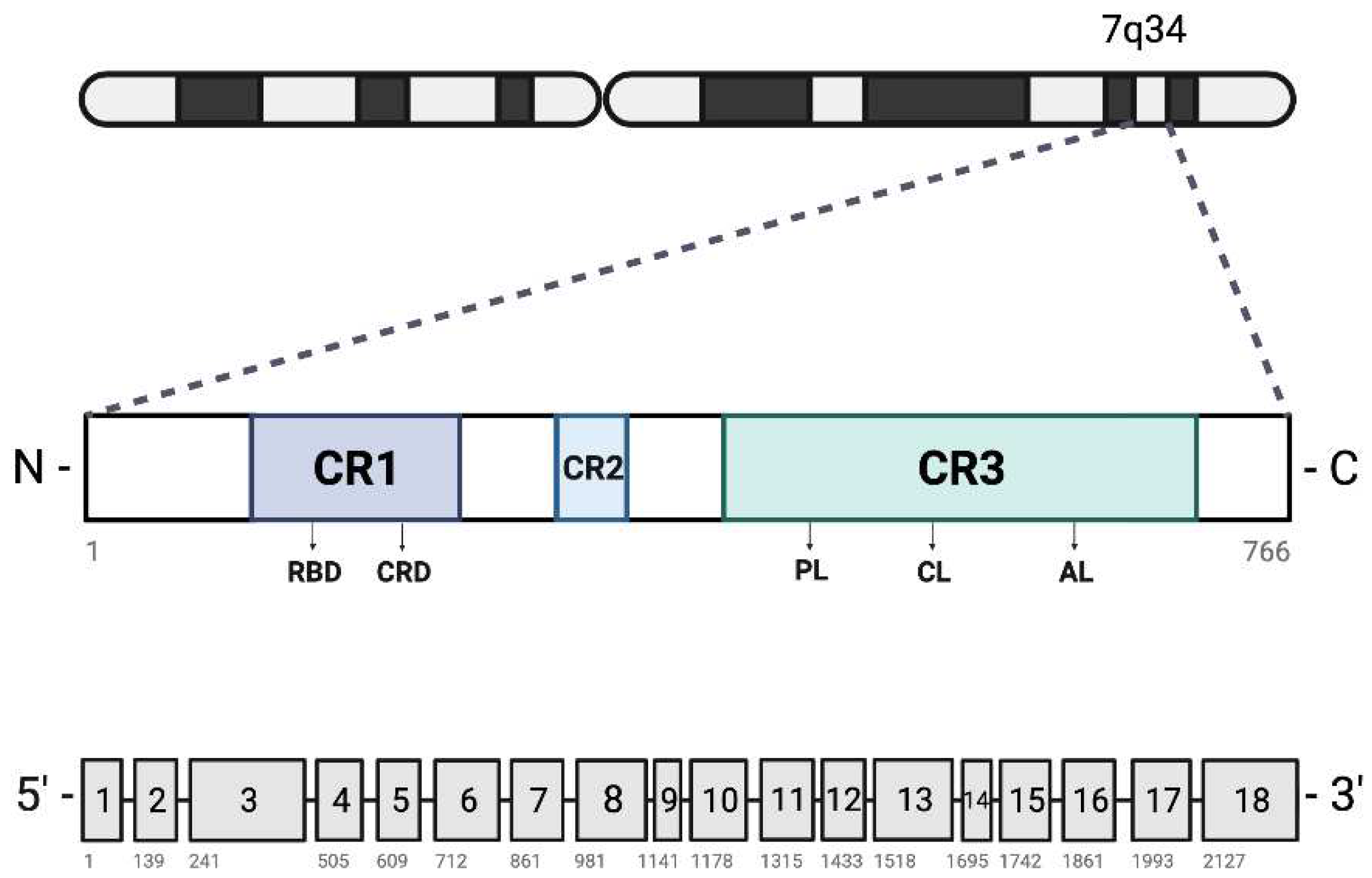

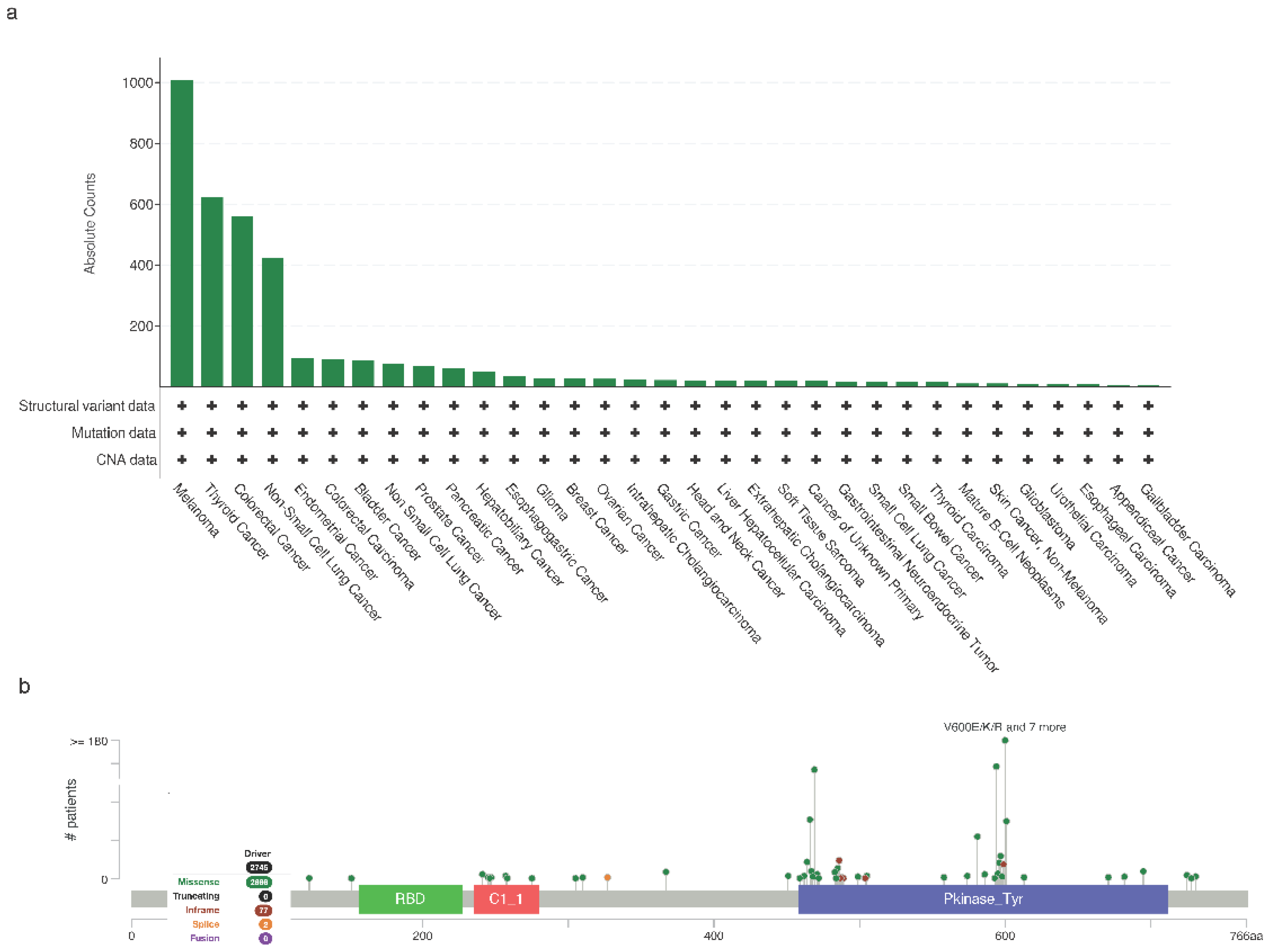

BRAF Mutations in Cancer

Melanoma

Thyroid

Lung Cancer

Colorectal

Other Cancers

Diagnostic Approaches for BRAF Mutations

Detection of mutations

Targeted therapies for BRAF-mutated cancers

| BRAF inhibitors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Inhibitor type | Approved to treat | Date approved by the FDA |

|

Sorafenib (Nexlavar) Also: Sorafenib tosylate |

1st-gen BRAFi | Advanced renal cell carcinoma Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma Locally recurrent or metastatic, progressive, differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) refractory to radioactive iodine treatment |

12/20/2005 |

|

Vemurafenib (Zelboraf) Also: PLX4032 |

2nd-gen BRAFi | Unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation Erdheim-Chester disease with BRAF V600 mutation |

8/17/2011 |

|

Dabrafenib (Tafinlar) Also: GSK-2118436 |

2nd-gen BRAFi | Unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation |

5/29/2013 |

|

Encorafenib (Braftovi) Also: LGX818 |

2nd-gen BRAFi | (Not approved for use as single agent) | 6/27/2018 |

| Combination Therapies | |||

| Drug | Inhibitor types | Approved to treat | Date approved by the FDA |

|

Dabrafenib + Trametinib (Tafinlar + Mekinist) Also: GSK-2118436 + GSK-1120212 |

Dabrafenib: BRAFi Trametinib: MEK1/2i |

Unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E/K NSCLC with BRAF V600E mutation and involvement of lymph node(s), following complete resection Locally advanced or metastatic anaplastic thyroid cancer with BRAF V600E mutation Unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with BRAF V600E mutation and no satisfactory alternative treatment options Pediatric patients 1 year of age and older with low-grade glioma with a BRAF V600E mutation |

1/9/2014 |

|

Vemurafenib + Cobimetinib (Zelboraf + Cotellic) Also: PLX4032 + GDC-0973 |

Vemurafenib: BRAFi Cobimetinib: MEK1/2i |

Unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E/K | 11/10/2015 |

|

Encorafenib + Binimetinib (Braftovi + Mektovi) Also: LGX818 + MEK162 |

Encorafenib: BRAFi Binimetinib: MEK1/2i |

Unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E/K Metastatic NSCLC with BRAF V600E |

6/27/2018 |

|

Encorafenib + Cetuximab (Braftovi + Erbitux) Also: LGX818 + Encorafenib |

Encorafenib: BRAFi Cetuximab: monoclonal antibody, EGFR antagonist |

Metastatic CRC with a BRAF V600E mutation (after prior therapy) | 4/8/2020 |

|

Vemurafenib + Cobimetinib + Atezolizumab (Zelboraf + Cotellic + Tecentriq) Also: PLX4032 + GDC-0973 + RG7446 |

Vemurafenib: BRAFi Cobimetinib: MEK1/2i Atezolizumab: PD-L1 blocking antibody |

Unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600 | 7/30/2020 |

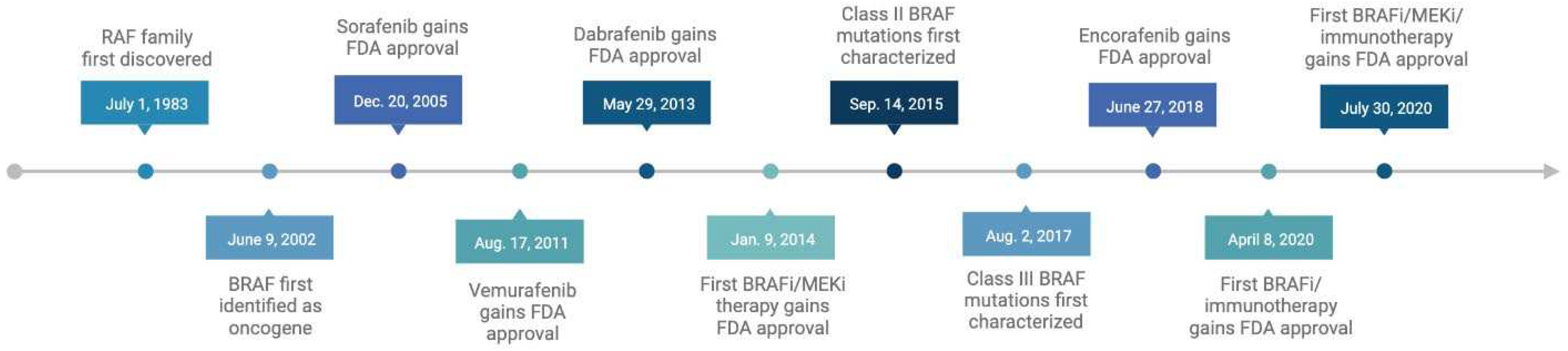

First generation BRAF inhibitors

Second generation BRAF inhibitors

Combination therapies

Third generation BRAF inhibitors

Resistance mechanisms and overcoming challenges

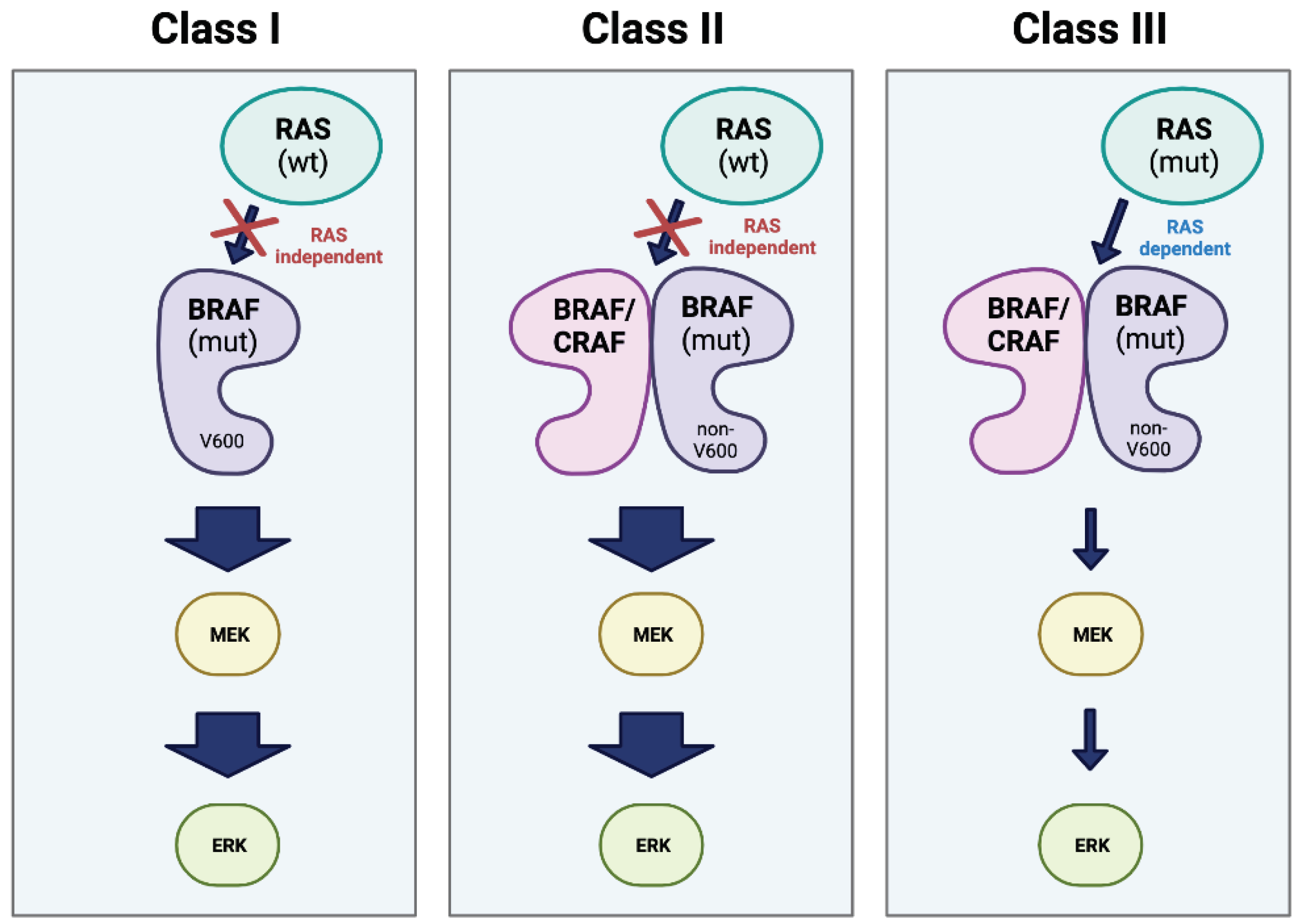

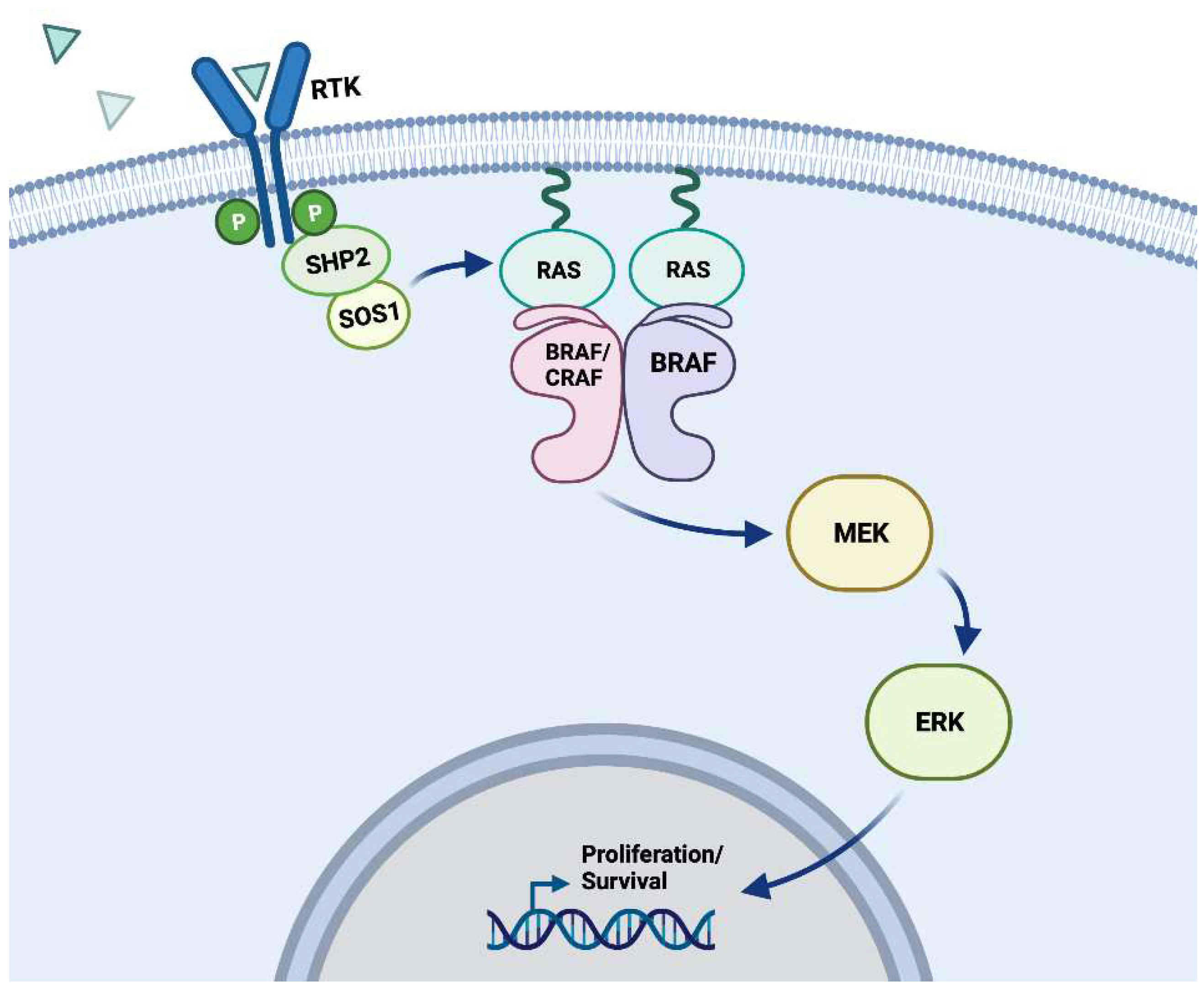

BRAF and the MAPK signaling pathway

MEK/ERK dependent resistance

MEK/ERK independent resistance

Clinical implications and patient outcomes

| Drug(s) | G3-G5 | Any grade |

|---|---|---|

|

Vemurafenib (Zelboraf) |

51% | 94% |

|

Dabrafenib (Tafinlar) |

50% | 85% |

|

Encorafenib (Braftovi) |

68% | 99% |

|

Dabrafenib + Trametinib (Tafinlar + Mekinist) |

43% | 95% |

|

Vemurafenib + Cobimetinib (Zelboraf + Cotellic) |

72% | 98% |

|

Encorafenib + Binimetinib (Braftovi + Mektovi) |

68% | 98% |

Conclusions and future directions

Authors contributions

Fundings

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ihle, M.A.; Fassunke, J.; Konig, K.; Grunewald, I.; Schlaak, M.; Kreuzberg, N.; Tietze, L.; Schildhaus, H.U.; Buttner, R.; Merkelbach-Bruse, S. Comparison of high resolution melting analysis, pyrosequencing, next generation sequencing and immunohistochemistry to conventional Sanger sequencing for the detection of p.V600E and non-p.V600E BRAF mutations. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, E.L.; Subbiah, V.; Lockhart, A.C.; Blay, J.Y.; Puzanov, I.; Chau, I.; Raje, N.S.; Wolf, J.; Erinjeri, J.P.; Torrisi, J.; et al. Vemurafenib for BRAF V600-Mutant Erdheim-Chester Disease and Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: Analysis of Data From the Histology-Independent, Phase 2, Open-label VE-BASKET Study. JAMA Oncol 2018, 4, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisone, D.; Friedlaender, A.; Malapelle, U.; Banna, G.; Addeo, A. A BRAF new world. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2020, 152, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayward, N.K.; Wilmott, J.S.; Waddell, N.; Johansson, P.A.; Field, M.A.; Nones, K.; Patch, A.M.; Kakavand, H.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Burke, H.; et al. Whole-genome landscapes of major melanoma subtypes. Nature 2017, 545, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Garcia, E.; Argiles, G.; Elez, E.; Tabernero, J. BRAF mutant colorectal cancer: prognosis, treatment, and new perspectives. Ann Oncol 2017, 28, 2648–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matallanas, D.; Birtwistle, M.; Romano, D.; Zebisch, A.; Rauch, J.; von Kriegsheim, A.; Kolch, W. Raf family kinases: old dogs have learned new tricks. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 232–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, P.; Haser, W.; Haystead, T.A.; Vincent, L.A.; Roberts, T.M.; Sturgill, T.W. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase by v-Raf in NIH 3T3 cells and in vitro. Science 1992, 257, 1404–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakis, J.M.; App, H.; Zhang, X.F.; Banerjee, P.; Brautigan, D.L.; Rapp, U.R.; Avruch, J. Raf-1 activates MAP kinase-kinase. Nature 1992, 358, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodie, S.A.; Willumsen, B.M.; Weber, M.J.; Wolfman, A. Complexes of Ras.GTP with Raf-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. Science 1993, 260, 1658–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aelst, L.; Barr, M.; Marcus, S.; Polverino, A.; Wigler, M. Complex formation between RAS and RAF and other protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993, 90, 6213–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtek, A.B.; Hollenberg, S.M.; Cooper, J.A. Mammalian Ras interacts directly with the serine/threonine kinase Raf. Cell 1993, 74, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warne, P.H.; Viciana, P.R.; Downward, J. Direct interaction of Ras and the amino-terminal region of Raf-1 in vitro. Nature 1993, 364, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, H.T. MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell Res 2002, 12, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.F.; Settleman, J.; Kyriakis, J.M.; Takeuchi-Suzuki, E.; Elledge, S.J.; Marshall, M.S.; Bruder, J.T.; Rapp, U.R.; Avruch, J. Normal and oncogenic p21ras proteins bind to the amino-terminal regulatory domain of c-Raf-1. Nature 1993, 364, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulikakos, P.I.; Sullivan, R.J.; Yaeger, R. Molecular Pathways and Mechanisms of BRAF in Cancer Therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2022, 28, 4618–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.H.; Wu, X.; Frost, J.A. B-Raf and Raf-1 are regulated by distinct autoregulatory mechanisms. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 16244–16253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, A.S.; Meikle, S.; Yazici, Z.; Eulitz, M.; Kolch, W. Regulation of Raf-1 activation and signalling by dephosphorylation. EMBO J 2002, 21, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, H.; Lee, J.; Guan, K.L. Positive and negative regulation of Raf kinase activity and function by phosphorylation. EMBO J 2001, 20, 3716–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tecentriq [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc; 2023.

- Zelboraf [package insert]. Basel, Switzerland: Hoffmann La Roche; 2017.

- Mekinist [package insert]. Basel, Switzerland: Novartis Pharmaceuticals; 2023.

- Braftovi [package insert]. Boulder, CO: Array Biopharma Inc.; 2023.

- Nexavar [package insert]. Berlin, Germany: Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals LLC; 2023.

- Tafinlar [package insert]. Basel, Switzerland: Novartis Pharmaceuticals; 2023.

- Erbitux [package insert]. Bridgewater, New Jersey: ImClone Systems Incorporated; 2021.

- Davies, H.; Bignell, G.R.; Cox, C.; Stephens, P.; Edkins, S.; Clegg, S.; Teague, J.; Woffendin, H.; Garnett, M.J.; Bottomley, W.; et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002, 417, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, U.R.; Goldsborough, M.D.; Mark, G.E.; Bonner, T.I.; Groffen, J.; Reynolds, F.H., Jr.; Stephenson, J.R. Structure and biological activity of v-raf, a unique oncogene transduced by a retrovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1983, 80, 4218–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Sun, Q.; Zhu, J. Identification and Characterization of Small-Molecule Inhibitors to Selectively Target the DFG-in over the DFG-out Conformation of the B-Raf Kinase V600E Mutant in Colorectal Cancer. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2016, 349, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Yaeger, R.; Rodrik-Outmezguine, V.S.; Tao, A.; Torres, N.M.; Chang, M.T.; Drosten, M.; Zhao, H.; Cecchi, F.; Hembrough, T.; et al. Tumours with class 3 BRAF mutants are sensitive to the inhibition of activated RAS. Nature 2017, 548, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Massari, F.; MacLennan, G.T.; Montironi, R. Molecular testing for BRAF mutations to inform melanoma treatment decisions: a move toward precision medicine. Mod Pathol 2018, 31, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhomen, N.; Marais, R. New insight into BRAF mutations in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2007, 17, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, A.; Felicioni, L.; Malatesta, S.; Grazia Sciarrotta, M.; Guetti, L.; Chella, A.; Viola, P.; Pullara, C.; Mucilli, F.; Buttitta, F. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29, 3574–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, Y.E.; Nikiforova, M.N. Molecular genetics and diagnosis of thyroid cancer. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011, 7, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisapia, P.; Pepe, F.; Malapelle, U.; Troncone, G. BRAF Mutations in Lung Cancer. Acta Cytol 2019, 63, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirripa, M.; Biason, P.; Lonardi, S.; Pella, N.; Pino, M.S.; Urbano, F.; Antoniotti, C.; Cremolini, C.; Corallo, S.; Pietrantonio, F.; et al. Class 1, 2, and 3 BRAF-Mutated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Detailed Clinical, Pathologic, and Molecular Characterization. Clin Cancer Res 2019, 25, 3954–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Sonawane, P.; Kumar, A.; Singh, H.; Naumovich, V.; Pathak, P.; Grishina, M.; Khalilullah, H.; Jaremko, M.; Emwas, A.H.; et al. Challenges and Opportunities in the Crusade of BRAF Inhibitors: From 2002 to 2022. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 27819–27844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.T.; Mitchell, T.N.; Zehir, A.; Shah, R.H.; Benayed, R.; Syed, A.; Chandramohan, R.; Liu, Z.Y.; Won, H.H.; Scott, S.N.; et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn 2015, 17, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracht, J.W.P.; Karachaliou, N.; Bivona, T.; Lanman, R.B.; Faull, I.; Nagy, R.J.; Drozdowskyj, A.; Berenguer, J.; Fernandez-Bruno, M.; Molina-Vila, M.A.; et al. BRAF Mutations Classes I, II, and III in NSCLC Patients Included in the SLLIP Trial: The Need for a New Pre-Clinical Treatment Rationale. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankner, M.; Rose, A.A.N.; Rajkumar, S.; Siegel, P.M.; Watson, I.R. Classifying BRAF alterations in cancer: new rational therapeutic strategies for actionable mutations. Oncogene 2018, 37, 3183–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, M.G.; Malapelle, U.; Andre, F.; Paz-Ares, L.; Schuler, M.; Thomas, D.M.; Vainer, G.; Yoshino, T.; Rolfo, C. Practical Considerations for the Use of Circulating Tumor DNA in the Treatment of Patients With Cancer: A Narrative Review. JAMA Oncol 2022, 8, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiech, M.; Leszczynski, P.; Kono, H.; Wardell, C.; Taniguchi, H. Emerging BRAF Mutations in Cancer Progression and Their Possible Effects on Transcriptional Networks. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradish, J.R.; Cheng, L. Molecular pathology of malignant melanoma: changing the clinical practice paradigm toward a personalized approach. Hum Pathol 2014, 45, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Flaherty, K.T. BRAF targeted therapy changes the treatment paradigm in melanoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011, 8, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Menzies, A.M.; Nagrial, A.M.; Haydu, L.E.; Hamilton, A.L.; Mann, G.J.; Hughes, T.M.; Thompson, J.F.; Scolyer, R.A.; Kefford, R.F. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dummer, R.; Ascierto, P.A.; Gogas, H.J.; Arance, A.; Mandala, M.; Liszkay, G.; Garbe, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Krajsova, I.; Gutzmer, R.; et al. Encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma (COLUMBUS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018, 19, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Dreno, B.; Atkinson, V.; Liszkay, G.; Maio, M.; Mandala, M.; Demidov, L.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Thomas, L.; et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 1867–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, A.; Haidar, A.; Anghel, R.M. Treating malignant melanoma when a rare BRAF V600M mutation is present: case report and literature review. Rom J Intern Med 2018, 56, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Flaherty, K.T.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Gogas, H.; Levchenko, E.; de Braud, F.; Larkin, J.; Garbe, C.; Jouary, T.; Hauschild, A.; et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib versus dabrafenib monotherapy in patients with metastatic BRAF V600E/K-mutant melanoma: long-term survival and safety analysis of a phase 3 study. Ann Oncol 2017, 28, 1631–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Rutkowski, P.; Lao, C.D.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Dummer, R.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab or Nivolumab Alone Versus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, A.J.; Zhu, Z.; Gandhi, M.; Steward, D.L.; Fidler, J.P.; Giordano, T.J.; Biddinger, P.W.; Nikiforov, Y.E. Correlation between genetic alterations and microscopic features, clinical manifestations, and prognostic characteristics of thyroid papillary carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2006, 30, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elisei, R.; Ugolini, C.; Viola, D.; Lupi, C.; Biagini, A.; Giannini, R.; Romei, C.; Miccoli, P.; Pinchera, A.; Basolo, F. BRAF(V600E) mutation and outcome of patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: a 15-year median follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008, 93, 3943–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Rosenbaum, E.; Clark, D.P.; Zeiger, M.A.; Umbricht, C.B.; Tufano, R.P.; Sidransky, D.; Westra, W.H. Mutational analysis of BRAF in fine needle aspiration biopsies of the thyroid: a potential application for the preoperative assessment of thyroid nodules. Clin Cancer Res 2004, 10, 2761–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforova, M.N.; Kimura, E.T.; Gandhi, M.; Biddinger, P.W.; Knauf, J.A.; Basolo, F.; Zhu, Z.; Giannini, R.; Salvatore, G.; Fusco, A.; et al. BRAF mutations in thyroid tumors are restricted to papillary carcinomas and anaplastic or poorly differentiated carcinomas arising from papillary carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 88, 5399–5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, M. BRAF mutation in thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2005, 12, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Vasko, V.; Tallini, G.; Larin, A.; Wu, G.; Udelsman, R.; Ringel, M.D.; Ladenson, P.W.; Sidransky, D. BRAF T1796A transversion mutation in various thyroid neoplasms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004, 89, 1365–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovisco, V.; Soares, P.; Sobrinho-Simoes, M. B-RAF mutations in the etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, and prognosis of thyroid carcinomas. Hum Pathol 2006, 37, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauf, J.A.; Ma, X.; Smith, E.P.; Zhang, L.; Mitsutake, N.; Liao, X.H.; Refetoff, S.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Fagin, J.A. Targeted expression of BRAFV600E in thyroid cells of transgenic mice results in papillary thyroid cancers that undergo dedifferentiation. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 4238–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, C., Jr.; Mirza, M.; Mitsutake, N.; Sartor, M.; Medvedovic, M.; Tomlinson, C.; Knauf, J.A.; Weber, G.F.; Fagin, J.A. Conditional activation of RET/PTC3 and BRAFV600E in thyroid cells is associated with gene expression profiles that predict a preferential role of BRAF in extracellular matrix remodeling. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 6521–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellevicine, C.; Migliatico, I.; Sgariglia, R.; Nacchio, M.; Vigliar, E.; Pisapia, P.; Iaccarino, A.; Bruzzese, D.; Fonderico, F.; Salvatore, D.; et al. Evaluation of BRAF, RAS, RET/PTC, and PAX8/PPARg alterations in different Bethesda diagnostic categories: A multicentric prospective study on the validity of the 7-gene panel test in 1172 thyroid FNAs deriving from different hospitals in South Italy. Cancer Cytopathol 2020, 128, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellevicine, C.; Sgariglia, R.; Malapelle, U.; Vigliar, E.; Nacchio, M.; Ciancia, G.; Eszlinger, M.; Paschke, R.; Troncone, G. Young investigator challenge: Can the Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 be used for next-generation sequencing of thyroid FNA samples? Cancer Cytopathol 2016, 124, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Park, Y.J.; Lim, J.A.; Ahn, H.Y.; Lee, E.K.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, K.W.; Hahn, S.K.; Youn, Y.K.; Kim, K.H.; et al. The association of the BRAF(V600E) mutation with prognostic factors and poor clinical outcome in papillary thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer 2012, 118, 1764–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, E.S.; Kim, Y.S. Clinicopathologic significance of BRAF V600E mutation in papillary carcinomas of the thyroid: a meta-analysis. Cancer 2007, 110, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Westra, W.H.; Tufano, R.P.; Cohen, Y.; Rosenbaum, E.; Rhoden, K.J.; Carson, K.A.; Vasko, V.; Larin, A.; Tallini, G.; et al. BRAF mutation predicts a poorer clinical prognosis for papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005, 90, 6373–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebebew, E.; Weng, J.; Bauer, J.; Ranvier, G.; Clark, O.H.; Duh, Q.Y.; Shibru, D.; Bastian, B.; Griffin, A. The prevalence and prognostic value of BRAF mutation in thyroid cancer. Ann Surg 2007, 246, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, Y.S.; Li, S.; Song, J.H.; Kwon, K.H.; Lee, J.C.; Rha, S.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Sul, J.Y.; Kweon, G.R.; Ro, H.K.; et al. Influence of the BRAF V600E mutation on expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006, 91, 3667–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Giuliano, A.E.; Turner, R.R.; Gaffney, R.E.; Umetani, N.; Kitago, M.; Elashoff, D.; Hoon, D.S. Lymphatic mapping establishes the role of BRAF gene mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Ann Surg 2006, 244, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.Y.; Kim, W.B.; Rhee, Y.S.; Song, J.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Gong, G.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, S.C.; Hong, S.J.; et al. The BRAF mutation is useful for prediction of clinical recurrence in low-risk patients with conventional papillary thyroid carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006, 65, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namba, H.; Nakashima, M.; Hayashi, T.; Hayashida, N.; Maeda, S.; Rogounovitch, T.I.; Ohtsuru, A.; Saenko, V.A.; Kanematsu, T.; Yamashita, S. Clinical implication of hot spot BRAF mutation, V599E, in papillary thyroid cancers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 88, 4393–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trovisco, V.; Soares, P.; Preto, A.; de Castro, I.V.; Lima, J.; Castro, P.; Maximo, V.; Botelho, T.; Moreira, S.; Meireles, A.M.; et al. Type and prevalence of BRAF mutations are closely associated with papillary thyroid carcinoma histotype and patients’ age but not with tumour aggressiveness. Virchows Arch 2005, 446, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Quiros, R.M.; Gattuso, P.; Ain, K.B.; Prinz, R.A. High prevalence of BRAF gene mutation in papillary thyroid carcinomas and thyroid tumor cell lines. Cancer Res 2003, 63, 4561–4567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014, 511, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imielinski, M.; Berger, A.H.; Hammerman, P.S.; Hernandez, B.; Pugh, T.J.; Hodis, E.; Cho, J.; Suh, J.; Capelletti, M.; Sivachenko, A.; et al. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell 2012, 150, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonetti, A.; Facchinetti, F.; Rossi, G.; Minari, R.; Conti, A.; Friboulet, L.; Tiseo, M.; Planchard, D. BRAF in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Pickaxing another brick in the wall. Cancer Treat Rev 2018, 66, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, G.; Yang, S.R.; Cocco, E.; Drilon, A. Rare molecular subtypes of lung cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2023, 20, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brustugun, O.T.; Khattak, A.M.; Tromborg, A.K.; Beigi, M.; Beiske, K.; Lund-Iversen, M.; Helland, A. BRAF-mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2014, 84, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Lim, J.S.; Jang, S.J.; Cun, Y.; Ozretic, L.; Kong, G.; Leenders, F.; Lu, X.; Fernandez-Cuesta, L.; Bosco, G.; et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature 2015, 524, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrock, A.B.; Li, S.D.; Frampton, G.M.; Suh, J.; Braun, E.; Mehra, R.; Buck, S.C.; Bufill, J.A.; Peled, N.; Karim, N.A.; et al. Pulmonary Sarcomatoid Carcinomas Commonly Harbor Either Potentially Targetable Genomic Alterations or High Tumor Mutational Burden as Observed by Comprehensive Genomic Profiling. J Thorac Oncol 2017, 12, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosele, F.; Remon, J.; Mateo, J.; Westphalen, C.B.; Barlesi, F.; Lolkema, M.P.; Normanno, N.; Scarpa, A.; Robson, M.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with metastatic cancers: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann Oncol 2020, 31, 1491–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautschi, O.; Pauli, C.; Strobel, K.; Hirschmann, A.; Printzen, G.; Aebi, S.; Diebold, J. A patient with BRAF V600E lung adenocarcinoma responding to vemurafenib. J Thorac Oncol 2012, 7, e23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, S.; Michielin, O.; Zimmermann, S. Dramatic response induced by vemurafenib in a BRAF V600E-mutated lung adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2013, 31, e341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.D.; O’Shaughnessy, J.A.; Cowey, C.L.; Konduri, K. BRAF V600E-mutated lung adenocarcinoma with metastases to the brain responding to treatment with vemurafenib. Lung Cancer 2014, 85, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, S.; Siano, M.; Joerger, M.; Rodriguez, R.; Muller, J.; Fruh, M. Response to dabrafenib after progression on vemurafenib in a patient with advanced BRAF V600E-mutant bronchial adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2015, 87, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazieres, J.; Cropet, C.; Montane, L.; Barlesi, F.; Souquet, P.J.; Quantin, X.; Dubos-Arvis, C.; Otto, J.; Favier, L.; Avrillon, V.; et al. Vemurafenib in non-small-cell lung cancer patients with BRAF(V600) and BRAF(nonV600) mutations. Ann Oncol 2020, 31, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malapelle, U.; Pisapia, P.; Sgariglia, R.; Vigliar, E.; Biglietto, M.; Carlomagno, C.; Giuffre, G.; Bellevicine, C.; Troncone, G. Less frequently mutated genes in colorectal cancer: evidences from next-generation sequencing of 653 routine cases. J Clin Pathol 2016, 69, 767–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.N.; Kopetz, E.S. BRAF mutant colorectal cancer as a distinct subset of colorectal cancer: clinical characteristics, clinical behavior, and response to targeted therapies. J Gastrointest Oncol 2015, 6, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsalves, W.I.; Mahoney, M.R.; Sargent, D.J.; Nelson, G.D.; Alberts, S.R.; Sinicrope, F.A.; Goldberg, R.M.; Limburg, P.J.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Grothey, A.; et al. Patient and tumor characteristics and BRAF and KRAS mutations in colon cancer, NCCTG/Alliance N0147. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.C.; Renfro, L.A.; Al-Shamsi, H.O.; Schrock, A.B.; Rankin, A.; Zhang, B.Y.; Kasi, P.M.; Voss, J.S.; Leal, A.D.; Sun, J.; et al. (Non-V600) BRAF Mutations Define a Clinically Distinct Molecular Subtype of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017, 35, 2624–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocco, E.; Benhamida, J.; Middha, S.; Zehir, A.; Mullaney, K.; Shia, J.; Yaeger, R.; Zhang, L.; Wong, D.; Villafania, L.; et al. Colorectal Carcinomas Containing Hypermethylated MLH1 Promoter and Wild-Type BRAF/KRAS Are Enriched for Targetable Kinase Fusions. Cancer Res 2019, 79, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinney, J.; Dienstmann, R.; Wang, X.; de Reynies, A.; Schlicker, A.; Soneson, C.; Marisa, L.; Roepman, P.; Nyamundanda, G.; Angelino, P.; et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015, 21, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missiaglia, E.; Jacobs, B.; D’Ario, G.; Di Narzo, A.F.; Soneson, C.; Budinska, E.; Popovici, V.; Vecchione, L.; Gerster, S.; Yan, P.; et al. Distal and proximal colon cancers differ in terms of molecular, pathological, and clinical features. Ann Oncol 2014, 25, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina-Sarasqueta, A.; van Lijnschoten, G.; Moerland, E.; Creemers, G.J.; Lemmens, V.; Rutten, H.J.T.; van den Brule, A.J.C. The BRAF V600E mutation is an independent prognostic factor for survival in stage II and stage III colon cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2010, 21, 2396–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabernero, J.; Ros, J.; Elez, E. The Evolving Treatment Landscape in BRAF-V600E-Mutated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2022, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, E.L.; Durham, B.H.; Ulaner, G.A.; Drill, E.; Buthorn, J.; Ki, M.; Bitner, L.; Cho, H.; Young, R.J.; Francis, J.H.; et al. Efficacy of MEK inhibition in patients with histiocytic neoplasms. Nature 2019, 567, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horbinski, C.; Nikiforova, M.N.; Hagenkord, J.M.; Hamilton, R.L.; Pollack, I.F. Interplay among BRAF, p16, p53, and MIB1 in pediatric low-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol 2012, 14, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassaletta, A.; Zapotocky, M.; Mistry, M.; Ramaswamy, V.; Honnorat, M.; Krishnatry, R.; Guerreiro Stucklin, A.; Zhukova, N.; Arnoldo, A.; Ryall, S.; et al. Therapeutic and Prognostic Implications of BRAF V600E in Pediatric Low-Grade Gliomas. J Clin Oncol 2017, 35, 2934–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behling, F.; Schittenhelm, J. Oncogenic BRAF Alterations and Their Role in Brain Tumors. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisapia, P.; Pepe, F.; Iaccarino, A.; Sgariglia, R.; Nacchio, M.; Russo, G.; Gragnano, G.; Malapelle, U.; Troncone, G. BRAF: A Two-Faced Janus. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-de-Barros, A.V.; Anjos, R.S.D.; Silva, C.C.G.; Silva, E.; Araujo, F.; Carvalho, M.V. Diagnostic accuracy of immunohistochemistry compared with molecular tests for detection of BRAF V600E mutation in ameloblastomas: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Pathol Med 2022, 51, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, I.; Tanda, E.T.; Spagnolo, F.; Andreotti, V.; Bruno, W.; Ghiorzo, P. The Current State of Molecular Testing in the BRAF-Mutated Melanoma Landscape. Front Mol Biosci 2020, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.A.; Ong, E.; Huang, H.J.; McPhaul, L.W.; Yoon, S.; Janku, F.; Gianoukakis, A.G. Ultrasensitive detection of BRAF V600E mutations in circulating tumor DNA of patients with metastatic thyroid cancer. Endocrine 2022, 76, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.A.; Polivka, J.; Huang, H.J.; Treskova, I.; Pivovarcikova, K.; Fikrle, T.; Woznica, V.; Dustin, D.J.; Call, S.G.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; et al. Ultrasensitive detection of BRAF mutations in circulating tumor DNA of non-metastatic melanoma. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.A.; Subbiah, V. Precision oncology for biliary tract tumors: it’s written in blood! Ann Oncol 2022, 33, 1209–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, P.C.; Cote, G.J.; Hai, T.; Gule-Monroe, M.; Bui-Griffith, J.; Williams, M.D.; Hess, K.; Hofmann, M.C.; Dadu, R.; Zafereo, M.; et al. Circulating BRAF V600E Cell-Free DNA as a Biomarker in the Management of Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma. JCO Precis Oncol 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passiglia, F.; Malapelle, U.; Normanno, N.; Pinto, C. Optimizing diagnosis and treatment of EGFR exon 20 insertions mutant NSCLC. Cancer Treat Rev 2022, 109, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drilon, A.; Cappuzzo, F.; Ou, S.I.; Camidge, D.R. Targeting MET in Lung Cancer: Will Expectations Finally Be MET? J Thorac Oncol 2017, 12, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Luo, J.; Chang, J.; Rekhtman, N.; Arcila, M.; Drilon, A. MET-dependent solid tumours - molecular diagnosis and targeted therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020, 17, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benayed, R.; Offin, M.; Mullaney, K.; Sukhadia, P.; Rios, K.; Desmeules, P.; Ptashkin, R.; Won, H.; Chang, J.; Halpenny, D.; et al. High Yield of RNA Sequencing for Targetable Kinase Fusions in Lung Adenocarcinomas with No Mitogenic Driver Alteration Detected by DNA Sequencing and Low Tumor Mutation Burden. Clin Cancer Res 2019, 25, 4712–4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.D.; Le, A.T.; Sheren, J.; Nijmeh, H.; Gowan, K.; Jones, K.L.; Varella-Garcia, M.; Aisner, D.L.; Doebele, R.C. Comparison of Molecular Testing Modalities for Detection of ROS1 Rearrangements in a Cohort of Positive Patient Samples. J Thorac Oncol 2018, 13, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.R.; Aypar, U.; Rosen, E.Y.; Mata, D.A.; Benayed, R.; Mullaney, K.; Jayakumaran, G.; Zhang, Y.; Frosina, D.; Drilon, A.; et al. A Performance Comparison of Commonly Used Assays to Detect RET Fusions. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27, 1316–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Offin, M.; Brannon, A.R.; Chang, J.; Chow, A.; Delasos, L.; Girshman, J.; Wilkins, O.; McCarthy, C.G.; Makhnin, A.; et al. MET Exon 14-altered Lung Cancers and MET Inhibitor Resistance. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, D.; Hondelink, L.M.; Solleveld-Westerink, N.; Uljee, S.M.; Ruano, D.; Cleton-Jansen, A.M.; von der Thusen, J.H.; Ramai, S.R.S.; Postmus, P.E.; Graadt van Roggen, J.F.; et al. Optimizing Mutation and Fusion Detection in NSCLC by Sequential DNA and RNA Sequencing. J Thorac Oncol 2020, 15, 1000–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmeules, P.; Boudreau, D.K.; Bastien, N.; Boulanger, M.C.; Bosse, Y.; Joubert, P.; Couture, C. Performance of an RNA-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Assay for Combined Detection of Clinically Actionable Fusions and Hotspot Mutations in NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep 2022, 3, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.S.; Wang, K.; Chmielecki, J.; Gay, L.; Johnson, A.; Chudnovsky, J.; Yelensky, R.; Lipson, D.; Ali, S.M.; Elvin, J.A.; et al. The distribution of BRAF gene fusions in solid tumors and response to targeted therapy. Int J Cancer 2016, 138, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capper, D.; Preusser, M.; Habel, A.; Sahm, F.; Ackermann, U.; Schindler, G.; Pusch, S.; Mechtersheimer, G.; Zentgraf, H.; von Deimling, A. Assessment of BRAF V600E mutation status by immunohistochemistry with a mutation-specific monoclonal antibody. Acta Neuropathol 2011, 122, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kateb, H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Steger-May, K.; Pfeifer, J.D. Identification of major factors associated with failed clinical molecular oncology testing performed by next generation sequencing (NGS). Mol Oncol 2015, 9, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighl, N.B.; Page, R.D.; Raymond, V.M.; Daniel, D.B.; Divers, S.G.; Reckamp, K.L.; Villalona-Calero, M.A.; Dix, D.; Odegaard, J.I.; Lanman, R.B.; et al. Clinical Utility of Comprehensive Cell-free DNA Analysis to Identify Genomic Biomarkers in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2019, 25, 4691–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose Brannon, A.; Jayakumaran, G.; Diosdado, M.; Patel, J.; Razumova, A.; Hu, Y.; Meng, F.; Haque, M.; Sadowska, J.; Murphy, B.J.; et al. Enhanced specificity of clinical high-sensitivity tumor mutation profiling in cell-free DNA via paired normal sequencing using MSK-ACCESS. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, H.; Therrien, M. Regulation of RAF protein kinases in ERK signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015, 16, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornev, A.P.; Taylor, S.S. Dynamics-Driven Allostery in Protein Kinases. Trends Biochem Sci 2015, 40, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karoulia, Z.; Gavathiotis, E.; Poulikakos, P.I. New perspectives for targeting RAF kinase in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2017, 17, 676–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall-Jackson, C.A.; Eyers, P.A.; Cohen, P.; Goedert, M.; Boyle, F.T.; Hewitt, N.; Plant, H.; Hedge, P. Paradoxical activation of Raf by a novel Raf inhibitor. Chem Biol 1999, 6, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Nielsen, T.E.; Clausen, M.H. FDA-approved small-molecule kinase inhibitors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015, 36, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnane, L.; Trail, P.A.; Taylor, I.; Wilhelm, S.M. Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006, Nexavar), a dual-action inhibitor that targets RAF/MEK/ERK pathway in tumor cells and tyrosine kinases VEGFR/PDGFR in tumor vasculature. Methods Enzymol 2006, 407, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, R.S.; He, P.; Modi, V.; Duong-Ly, K.C.; Ma, H.; Peterson, J.R.; Dunbrack, R.L., Jr.; Levy, R.M. Conformational analysis of the DFG-out kinase motif and biochemical profiling of structurally validated type II inhibitors. J Med Chem 2015, 58, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer; Amgen. Study of BAY43-9006 in Patients With Unresectable and/or Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer. 2006.

- Tabernero, J.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Cassidy, J.; Sobrero, A.; Van Cutsem, E.; Kohne, C.H.; Tejpar, S.; Gladkov, O.; Davidenko, I.; Salazar, R.; et al. Sorafenib in combination with oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and fluorouracil (modified FOLFOX6) as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: the RESPECT trial. Clin Cancer Res 2013, 19, 2541–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, K.T.; Puzanov, I.; Kim, K.B.; Ribas, A.; McArthur, G.A.; Sosman, J.A.; O’Dwyer, P.J.; Lee, R.J.; Grippo, J.F.; Nolop, K.; et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010, 363, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, A.; Grob, J.J.; Demidov, L.V.; Jouary, T.; Gutzmer, R.; Millward, M.; Rutkowski, P.; Blank, C.U.; Miller, W.H., Jr.; Kaempgen, E.; et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012, 380, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraiso, K.H.; Fedorenko, I.V.; Cantini, L.P.; Munko, A.C.; Hall, M.; Sondak, V.K.; Messina, J.L.; Flaherty, K.T.; Smalley, K.S. Recovery of phospho-ERK activity allows melanoma cells to escape from BRAF inhibitor therapy. Br J Cancer 2010, 102, 1724–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussemart, L.; Routier, E.; Mateus, C.; Opletalova, K.; Sebille, G.; Kamsu-Kom, N.; Thomas, M.; Vagner, S.; Favre, M.; Tomasic, G.; et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol 2013, 24, 1691–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotellic [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc.; 2015.

- Ribas, A.; Lawrence, D.; Atkinson, V.; Agarwal, S.; Miller, W.H., Jr.; Carlino, M.S.; Fisher, R.; Long, G.V.; Hodi, F.S.; Tsoi, J.; et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition with PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nat Med 2019, 25, 936–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lito, P.; Pratilas, C.A.; Joseph, E.W.; Tadi, M.; Halilovic, E.; Zubrowski, M.; Huang, A.; Wong, W.L.; Callahan, M.K.; Merghoub, T.; et al. Relief of profound feedback inhibition of mitogenic signaling by RAF inhibitors attenuates their activity in BRAFV600E melanomas. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 668–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ding, H.; Qian, J.; Lizaso, A.; Lin, J.; Han-Zhang, H.; Xiang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, H. The association between BRAF mutation class and clinical features in BRAF-mutant Chinese non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Transl Med 2019, 17, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoulia, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ahmed, T.A.; Xin, Q.; Bollard, J.; Krepler, C.; Wu, X.; Zhang, C.; Bollag, G.; Herlyn, M.; et al. An Integrated Model of RAF Inhibitor Action Predicts Inhibitor Activity against Oncogenic BRAF Signaling. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertazza, L.; Barollo, S.; Radu, C.M.; Cavedon, E.; Simioni, P.; Faggian, D.; Plebani, M.; Pelizzo, M.R.; Rubin, B.; Boscaro, M.; et al. Synergistic antitumour activity of RAF265 and ZSTK474 on human TT medullary thyroid cancer cells. J Cell Mol Med 2015, 19, 2244–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.B.; Henry, J.R.; Kaufman, M.D.; Lu, W.P.; Smith, B.D.; Vogeti, S.; Rutkoski, T.J.; Wise, S.; Chun, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Inhibition of RAF Isoforms and Active Dimers by LY3009120 Leads to Anti-tumor Activities in RAS or BRAF Mutant Cancers. Cancer Cell 2015, 28, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Lavoie, H.; Sahmi, M.; David, M.; Hilt, C.; Hammell, A.; Therrien, M. RAF inhibitors promote RAS-RAF interaction by allosterically disrupting RAF autoinhibition. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.H.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, S.B.; Huang, J.L.; Zhao, X.X.; Ding, H.; Pan, Y.L. Development of small-molecule therapeutics and strategies for targeting RAF kinase in BRAF-mutant colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag Res 2018, 10, 2289–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarian, R.; Shi, H.; Wang, Q.; Kong, X.; Koya, R.C.; Lee, H.; Chen, Z.; Lee, M.K.; Attar, N.; Sazegar, H.; et al. Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature 2010, 468, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulikakos, P.I.; Zhang, C.; Bollag, G.; Shokat, K.M.; Rosen, N. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature 2010, 464, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty, K.T.; Infante, J.R.; Daud, A.; Gonzalez, R.; Kefford, R.F.; Sosman, J.; Hamid, O.; Schuchter, L.; Cebon, J.; Ibrahim, N.; et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med 2012, 367, 1694–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Hugo, W.; Kong, X.; Hong, A.; Koya, R.C.; Moriceau, G.; Chodon, T.; Guo, R.; Johnson, D.B.; Dahlman, K.B.; et al. Acquired resistance and clonal evolution in melanoma during BRAF inhibitor therapy. Cancer Discov 2014, 4, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Conde, C.; Ruiz-Llorente, S.; Dominguez, J.M.; Knauf, J.A.; Viale, A.; Sherman, E.J.; Ryder, M.; Ghossein, R.A.; Rosen, N.; Fagin, J.A. Relief of feedback inhibition of HER3 transcription by RAF and MEK inhibitors attenuates their antitumor effects in BRAF-mutant thyroid carcinomas. Cancer Discov 2013, 3, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahallad, A.; Sun, C.; Huang, S.; Di Nicolantonio, F.; Salazar, R.; Zecchin, D.; Beijersbergen, R.L.; Bardelli, A.; Bernards, R. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature 2012, 483, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Park, J.I. Tumor Cell Resistance to the Inhibition of BRAF and MEK1/2. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidorn, S.J.; Milagre, C.; Whittaker, S.; Nourry, A.; Niculescu-Duvas, I.; Dhomen, N.; Hussain, J.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Springer, C.J.; Pritchard, C.; et al. Kinase-dead BRAF and oncogenic RAS cooperate to drive tumor progression through CRAF. Cell 2010, 140, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagle, N.; Van Allen, E.M.; Treacy, D.J.; Frederick, D.T.; Cooper, Z.A.; Taylor-Weiner, A.; Rosenberg, M.; Goetz, E.M.; Sullivan, R.J.; Farlow, D.N.; et al. MAP kinase pathway alterations in BRAF-mutant melanoma patients with acquired resistance to combined RAF/MEK inhibition. Cancer Discov 2014, 4, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Bi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qin, F.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Targeting RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway in human cancer: Current status in clinical trials. Genes Dis 2023, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Fung, C.; Menzies, A.M.; Pupo, G.M.; Carlino, M.S.; Hyman, J.; Shahheydari, H.; Tembe, V.; Thompson, J.F.; Saw, R.P.; et al. Increased MAPK reactivation in early resistance to dabrafenib/trametinib combination therapy of BRAF-mutant metastatic melanoma. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahronian, L.G.; Sennott, E.M.; Van Allen, E.M.; Wagle, N.; Kwak, E.L.; Faris, J.E.; Godfrey, J.T.; Nishimura, K.; Lynch, K.D.; Mermel, C.H.; et al. Clinical Acquired Resistance to RAF Inhibitor Combinations in BRAF-Mutant Colorectal Cancer through MAPK Pathway Alterations. Cancer Discov 2015, 5, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, D.; Sennott, E.M.; Barault, L.; Valtorta, E.; Arena, S.; Cassingena, A.; Filiciotto, G.; Marzolla, G.; Elez, E.; van Geel, R.M.; et al. Molecular Landscape of Acquired Resistance to Targeted Therapy Combinations in BRAF-Mutant Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 4504–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Childress, M.A.; Chalmers, Z.R.; Frampton, G.M.; Ali, S.M.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Fabrizio, D.; Ross, J.S.; Balasubramanian, S.; Miller, V.A.; et al. BRAF internal deletions and resistance to BRAF/MEK inhibitor therapy. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2018, 31, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.A.; Whalen, D.M.; Ozen, A.; Wongchenko, M.J.; Yin, J.; Yen, I.; Schaefer, G.; Mayfield, J.D.; Chmielecki, J.; Stephens, P.J.; et al. Activation Mechanism of Oncogenic Deletion Mutations in BRAF, EGFR, and HER2. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, X. Resistance mechanism of the oncogenic beta3-alphaC deletion mutation in BRAF kinase to dabrafenib and vemurafenib revealed by molecular dynamics simulations and binding free energy calculations. Chem Biol Drug Des 2019, 93, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Q.; Liu, J.; Huang, L.; Qin, Y.; Hawley, T.; Seo, C.; Merlino, G.; Yu, Y. AXL/AKT axis mediated-resistance to BRAF inhibitor depends on PTEN status in melanoma. Oncogene 2018, 37, 3275–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabner, B.A.; Roberts, T.G., Jr. Timeline: Chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2005, 5, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzone, L.; Salomone, S.; Libra, M. Evolution of Cancer Pharmacological Treatments at the Turn of the Third Millennium. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolch, W. Meaningful relationships: the regulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by protein interactions. Biochem J 2000, 351 Pt 2, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, G.C.; Falzone, L.; Salemi, R.; Zanghi, A.; Spandidos, D.A.; McCubrey, J.A.; Candido, S.; Libra, M. Cutaneous melanoma: From pathogenesis to therapy (Review). Int J Oncol 2018, 52, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, D.K. MAP kinase pathways. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoadley, K.A.; Yau, C.; Wolf, D.M.; Cherniack, A.D.; Tamborero, D.; Ng, S.; Leiserson, M.D.M.; Niu, B.; McLellan, M.D.; Uzunangelov, V.; et al. Multiplatform analysis of 12 cancer types reveals molecular classification within and across tissues of origin. Cell 2014, 158, 929–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibney, G.T.; Messina, J.L.; Fedorenko, I.V.; Sondak, V.K.; Smalley, K.S. Paradoxical oncogenesis--the long-term effects of BRAF inhibition in melanoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013, 10, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCC MERP, 2008. Statement on Medication Error Rates [WWW Document]. National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. URL https://www.nccmerp.org/statement-medication-error-rates.

- Garutti, M.; Bergnach, M.; Polesel, J.; Palmero, L.; Pizzichetta, M.A.; Puglisi, F. BRAF and MEK Inhibitors and Their Toxicities: A Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).