Introduction

Recent studies justify using the first language (L1) and claim its positive impact in foreign language classrooms (Hall & Cook, 2012; Masuda, 2019). One common reason for the persistent avoidance of L1 in foreign language education is that students typically come from diverse cultural and linguistic origins and, thus, do not share a common first language. However, the growing status of English as a global language has influenced some changes worldwide, and the issue of using it instead of L1 as a medium of instruction in multilingual classrooms has arisen. The current study, conducted on a supranational level, sheds light on the actual state of EMI implementation in foreign language teaching, which, unlike other academic subjects (e.g., law, medicine, engineering), has been a rare research topic so far (Bruen & Kelly, 2017). The study of English as a language to mediate learning of the target language (Japanese) received very little attention in the past. Therefore, the given empirical research aimed to investigate the state of implementation of EMI in different educational stages worldwide in Japanese language teaching by non-native speakers with a focus on multilingual classes. Moreover, the present study also aimed to shed light on the teachers’ beliefs regarding the positive and negative aspects of EMI implementation.

Multilingualism has an impact on foreign language learning. Teachers should understand the unique characteristics of multilingual learners to aid their language acquisition process (Alba de la Fuente & Lacroix, 2015).

In this paper, a multilingual classroom is defined as one that comprises students from various cultural and native-language backgrounds (regardless of their level of proficiency), and where there is no one common mother tongue for teachers and all students. Multilingual classrooms are growing in number for various reasons, including geopolitical conflicts, war, and environmental catastrophes. People are seeking better employment opportunities and higher living standards.

Though the prevalence of multilingual classrooms has been a significant trend in the USA, Canada, and Australia for many years, it has now spread to several EU countries in recent years (Brutt-Griffler, 2017). Overall, the earlier forms of EMI in Europe emerged due to an increasingly mobile European academic student and staff body (Aizawa, 2019). In the European Commission’s report (2015), “Language Teaching and Learning in multilingual classrooms”, the multilingual classroom is referred to as “a challenge” that Education authorities in many parts of the EU faced. Classrooms in tertiary education have become more linguistically diverse because of educational opportunities. Higher education establishments are interested in attracting more international students because of financial benefits. Such classrooms have become the norm rather than the exception in Europe also due to globalisation, increased European mobility, and international migration. All these factors have increased the physical movement of people across national boundaries and influenced the JFL classrooms as well (Luchenko & Bogdanova, 2023).

English medium instruction has become a rapidly expanding global phenomenon in all types and stages of education. Nevertheless, it remains a relatively new field of academic research interest. Specifically, the empirical studies that collected data at the global (Dearden, 2014) or European levels (Brenn-White & Faethe, 2012) are very limited, and some studies have been conducted at the level of two countries (Galloway et al., 2010) or a single country (Kapranov, 2021; Vural & Ölçü Dinçer, 2022). The highest proportion of investigations can be classified as “case studies of one institution”. Thus, despite the growing interest in the phenomenon, research in EMI is still young (Macaro et al., 2018).

The language or medium of instruction may be the mother tongue of students, the official or national language of the country, an international language such as English, or a combination of these (Peyton, 2015).

In some countries, the term “medium of instruction” is also known as “the language of learning and teaching” (Heugh et al., 2019, p. 10). In this paper, we use the notion “English as a medium of instruction (EMI)”, which is defined as the “use of English to teach academic subjects (other than English itself) in countries or jurisdictions where the first language of the majority of the population is not English (Macaro et al., 2018, p. 37). While L1 is a learner’s native dominant language (mother tongue), L2 is the second or additional language that necessarily has a lower level of proficiency than L1.

In the study on the use of English in learning Japanese, Turnbull (2018) uses other terminology, such as “English as a lingua franca” (ELF), denoting communication held in English between speakers of different mother tongues, the majority of which are non-native speakers of English. Two paradigms, “World Englishes” and ELF, share similar ideologies when English can no longer be considered the property of its tiny minority of native speakers. Therefore, the vast non-native-speaking majority are entitled to their own ways of using English (Fang & Widodo, 2019).

According to Turnbull’s (2018) study, “very little research has investigated the role of ELF in other language learning environments, such as those in which Japanese is learnt as a second language in Japan”. Turnbull’s findings suggest that learners generally welcome English language use. The author concludes that “learners seek security and comfort in what they already know, with ELF easing the gap between their L1 and their developing Japanese skills” (Turnbull, 2018, pp. 131–132).

Moreover, Bruen & Kelly’s (2017) findings indicate that non-native speakers of English consider themselves to be an advantage over native speakers of English in studying JFL in an English-medium university. This is mainly due to non-native English speakers’ extensive linguistic repertoire, which makes them experienced language learners.

Other research findings showed no difference in whether students engage in full or semi-EMI programmes; both are beneficial in motivating students or linguistic outcomes (Ament et al., 2020).

The paper undertakes a worldwide study on the use of English medium instruction in teaching Japanese as a foreign language and is focused on teacher-based linguistic practice. Our study was entirely dependent on the profile of the teacher in question rather than on official English-taught programmes provided in different institutions. Partially, it can be explained by the fact that introducing EMI in subjects such as Foreign Language is not a common practice. First, teaching using direct or indirect methods is somewhat controversial and contentious. Furthermore, the decision of whether to use a first language or English as a medium of instruction (or a mixture of both) can mostly depend on the teacher.

During the study, it was hypothesised that EMI had become helpful, particularly in multilingual Japanese language classes. This was the main correlation sought during the data analysis.

Methods

This study, involving non-native Japanese teachers, was conducted within the scope of larger-scale research involving native Japanese teachers. During our research project, we conducted a survey using a questionnaire sent to the official e-mails of Japanese-language institutions worldwide (The Japan Foundation, 2021). Each email contained a cover letter informing participants of the study purpose and anonymity (in Japanese and English) with two Google Forms or Jotform links (for both native and non-native Japanese teachers). All teachers were asked to participate regardless of whether they used English or not. Additionally, the invitation to participate in the survey was shared with teachers through professional networking Facebook groups.

In the study frame, we identified the countries to be included in the current research as those where the majority of the population’s native language is not English. Countries where English is the first language were excluded from the further analysis. For this reason, in compliance with our exclusion criteria, we did not consider six responses received from two countries in the North American region: Canada (n=2) and the United States of America (n=4).

The pilot survey was devised and conducted in August 2023 during Olha Luchenko’s training for Japanese language teachers at the Japan Foundation Japanese-Language Institute in Urawa (Japan). The survey was compiled after extensive consultation with Japanese language specialists in the Japan Foundation Japanese-Language Institute. As a result, the questionnaire was tested by 33 representatives from 20 countries who responded to the pilot Google Forms. These responses were also included in the overall analysis.

Due to the presumably different teaching methods between native and non-native Japanese language teachers, these findings were presented separately. Consequently, the present paper has a sample size of 56 countries and 261 teachers. Participants in the present study were from countries and regions across the globe (The Japan Foundation, 2021), including Argentina, Armenia, Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, China, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, El Salvador, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Honduras, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kyrgyz Republic, Lithuania, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Morocco, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, South Korea, Spain, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, and Vietnam.

The survey was split into three focus sections. The first section was devoted to the teacher’s profile and background, focusing on education and teaching experience. It asked about the respondents’ country of origin, age, level of formal education, whether they studied foreign teaching methods or linguodidactics, their form of employment, work experience, native language, Japanese language proficiency, other language knowledge, and English language proficiency.

The second section, “Teaching environment”, addressed such questions as the country of teaching, educational stage or institution where Japanese is taught, subjects and levels taught, the status of the Japanese language in the institution (a compulsory or an elective subject, etc.), and if the classroom is multilingual.

The third section was devoted to the usage of English as a language of instruction. The findings of the former two parts are primarily presented in a separate paper. However, the data from those sections were used to find possible correlations for the current research. The questionnaire for non-native Japanese language teachers contained 27 closed and open-ended questions, eight of which were exclusively used for the analysis in the present study. Both quantitative and qualitative methods were used. Two questions about the teachers’ beliefs included both predetermined variables for the possible positive as well as negative attitudes towards EMI and space for “freedom of expression”. Short answers to the open-ended questions were analysed with subjective interpretation and were added to the number of predetermined ones based on their close meaning. Long answers or those that did not fit any predetermined variant were analysed through content analysis relevant to the study’s overall purpose. They were presented separately as additional comments in this paper.

Results

The participants were asked to identify the primary language of instruction in their Japanese language classroom. As the findings showed, only one-fifth of the teachers (21.07%, n=55) indicated the target Japanese language, while the majority (64.37%, n=168) stated L1, with only 14.56% (n=38) specifying English as the primary language of instruction (

Figure 1).

Being aware that the question regarding the primary language was not supposed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the state of EMI, we posed it to identify the teachers’ general preferences. In Japanese classrooms, where most students are non-native English speakers, EMI is not used strategically as L1 but is considered an additional help. Students are engaged in multilingual practices, switching between L1, English, and Japanese.

As Turnbull (2018) states: “English plays a unique role in Japanese language classrooms as the “universal” language that students are often expected to know. Many classrooms have adopted multilingual practices through the use of English in the teaching of Japanese” (p. 133). This study addressed teaching the Japanese language through full or partial usage of English. The different degrees of intensity in EMI implementation received little attention in the past. Some researchers differentiated it as full and semi-English medium instruction in their research, not in the context of one lesson but in the context of a course of study in different groups of students (Ament et al., 2020).

Essentially, EMI implies a monolingual approach to teaching and learning. However, as Dearden (2014) indicates, 76% of her respondents reported having no written guidelines specifying whether English should be the only language used in EMI classrooms or whether code-switching is forbidden, allowed or encouraged (p. 25).

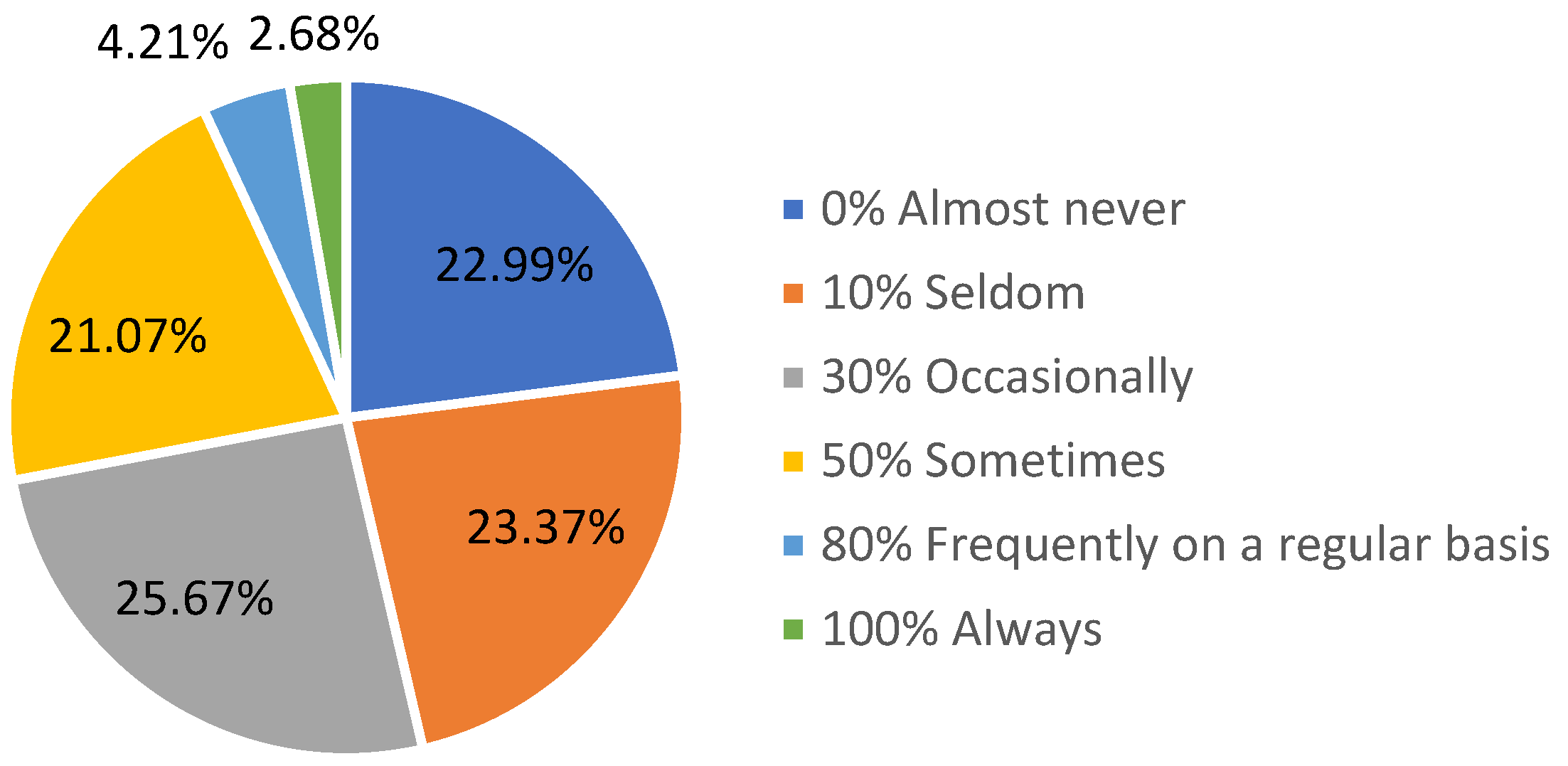

To investigate it in detail, the teachers were further asked about their experience with EMI and to estimate how much they used it in the teaching process (

Figure 2). As the academic subject in question was a foreign language (L3), we knew that the percentage of English as the language of instruction could be partial, and for the current study, 30% of use could be regarded as sufficient. When further discussing the variable of EMI use in JFL classrooms, the employment of English from 30% to 100% of instructional time will be considered significant.

Although most teachers suggested that the native language was the primary language of instruction, further inquiry found the role of English as a medium language. The majority of the teachers (53.63%, n=140) claimed that English was employed between 30% and 100% of the instructional time in their classroom. Very few participants (6.89%, n=18) claimed that English was always or frequently used. Hence, the vast amount of the substantial usage of EMI (46.74%, n=122) falls into the category of “occasionally or sometimes” (30%–50% of instructional time).

Interestingly, the analysis showed that among those respondents who stated L1 as the primary language of instruction, almost half of the teachers (48.21%, n=81) used English as an additional help between 30% and 50% of the time (

Table 1). Over one-third of the participants (38.18%, n=21) who stated Japanese as the primary language of instruction used English as additional to the same extent. We also cannot confirm the existence of a completely English-based learning environment in those classrooms where English was claimed as the primary language of instruction. English was used by the majority of the participants (52.63%, n=20) between 30% to 50% of instructional time.

Our study showed that translating or code-switching between Japanese, English, and L1 in JFL classrooms is a common practice. Based on the teachers’ comments, this phenomenon is mainly observed when the meaning of words (subject-specific English terminology) or grammar patterns are explained and students’ comprehension is checked.

Heugh et al. (2019) state that translanguaging includes:

a range of processes in which bi-/multilingual people use their knowledge of many languages and how to use these languages. It includes interpreting, translation, code-mixing, and code-switching. It includes how we use our language knowledge when moving between one language and another, i.e., ‘in-between’ practices. (p. 145)

Translanguaging has several potential educational advantages. Two of them, mentioned by Baker (2001), a leading scholar in the field, are “promoting a deeper and fuller understanding of the subject matter” and “helping in the development of the weaker language” (p. 281).

Galloway et al. (2020) highlight that the EMI approach does not have to be a monolingual endeavour: “It is hoped that the flourishing research of language use in EMI classroom will showcase the valuable use of translanguaging” (p. 410).

Teachers in most multilingual countries use code-switching when explaining concepts and information to students in the classroom, but they feel guilty about doing so (Heugh et al., 2019). In the comments to the questionnaire, many participants were willing to know the results of the present study. We can suppose most of them wanted to validate their own teaching methods by comparing them with other teachers’ practices and beliefs.

The results of our study showed that over 40% of all 261 JFL classes were multilingual. The given research demonstrated a clear correlation between the use of EMI in multilingual classrooms where English is used by the vast majority (68.86%) of respondents (n=73) in a range between 30% to 100% of the instructional time, which is a quarter (25.34%) higher than that in non-multilingual JFL classrooms (

Table 2).

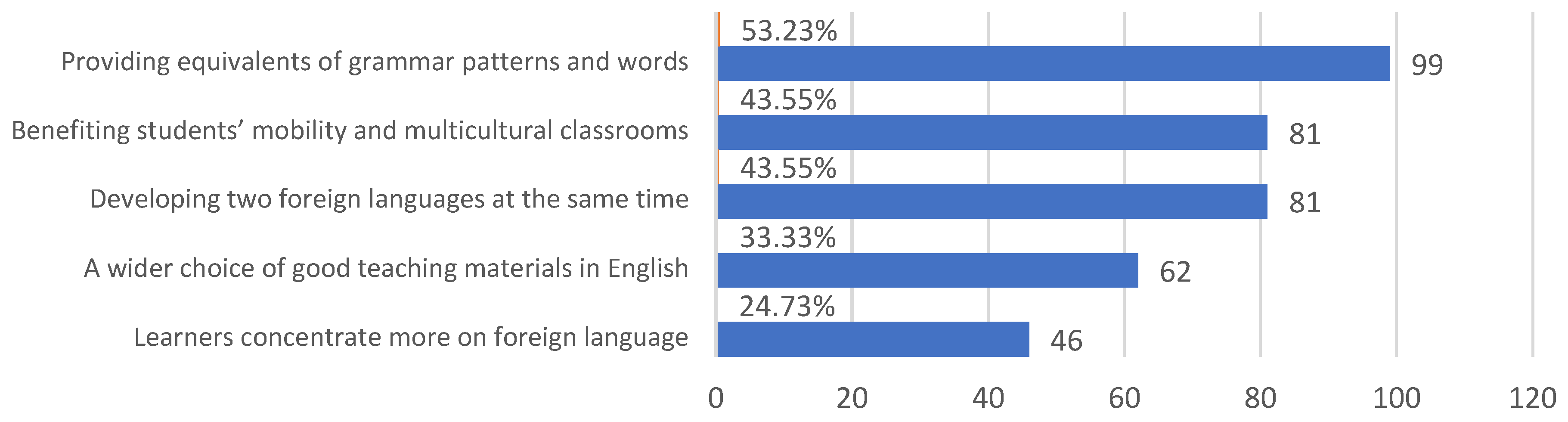

Those teachers who confirmed using English to a certain degree (from 10% and more) were asked to express the advantages and disadvantages of the EMI approach. There were five pre-determined options with the possibility of multiple answers. The question about the pros of EMI received 186 responses and comments out of 201 teachers. Fifteen teachers refrained from answering the question (

Figure 3).

As we can see from

Figure 3, the most common function for employing English in Japanese classrooms was to present English equivalents of grammar patterns and words or word combinations. Among the received qualitative comments, five teachers believed that English helps to differentiate the meaning of words and grammar patterns, so they use it for comparison to give one more variant when the meaning is unclear in L1. One participant commented in favour of EMI: “It is used whenever required to bring a better understanding of the grammar.” Another positive comment was: “Students understand the nuance of the Japanese language better when comparisons are made in English and Japanese”.

The positive feedback mentioned above confirms the following beneficial function mentioned by the researchers earlier: “The use of the dominant L2 allowed students to build bridges between the vocabulary and grammar of Japanese, English and their native language to learn new content effectively” (Turnbull, 2018, p. 143). The participants’ comments suggest that even those teachers who prefer to use only Japanese resort to EMI for clarification in order to build the connection between the known and unknown.

Two teachers mentioned that they mainly used English to explain loan words (gairaigo of English origin written in katakana). Two other opinions highlighted the advantages of EMI in multilingual classes, especially when students’ Japanese level was not high enough, namely, beginners and elementary (shokyū).

In favour of catering to the students’ needs, one respondent stated:

I use English to lessen the cognitive task demanded of the learners when they must memorise new words and grammar patterns. Also, since I am not a native speaker of Japanese, it is easier for me, as an instructor, to communicate in a language that is comfortable in a learning environment.

The idea of reducing cognitive load on learners was supported by another comment: “Students feel comfortable if English is initially used in the classroom at the beginner’s level.” The importance of the capacity to understand students’ needs is crucial for teachers. As Lin & Lo (2018) highlight in their study on the spread of EMI programmes in the Southeast Asian context: “As the teacher’s knowledge base also includes knowledge of learners, effective EMI teachers should have the ability to empathise with their students” (p. 92).

Although generally in favour of the direct teaching method, one participant commented:

In today’s universities, class time is limited, and the number of students exceeds 30 per class. The senior faculty members with long tenures frequently use “translation” as a learning tool. We face the practical problem of curriculum design in which subjects such as reading and writing are taught as separate classes. Under these circumstances, the frequency and proportion of EMI will inevitably increase somewhat.

As

Figure 3 shows, over one-third of the teachers favoured EMI for its benefit of developing two foreign languages simultaneously for students. This positive attitude was closely followed by the advantage of being helpful in multicultural classrooms and promoting students’ mobility. The results showed that “improving English ability” is one of the top positive aspects of implementing the EMI approach, even though it is not a primary goal in an L3 foreign language class. As Goya (2020) concludes in his study on EMI: “Considering the recently globalised world, it is inevitable that people will need to communicate through a common language that is usually different from their native language” (p. 79).

The respondents also stated the availability of better-quality Japanese-English language resources or lack of those in L1 in different countries among the reasons to adopt EMI to a certain extent in teaching Japanese. When asked if they used Japanese-English textbooks or supplementary teaching material, most teachers (56.32%, n=147) answered positively. One participant mentioned recommending English-based textbooks to those students who have difficulty catching up on the material. Another participant used a lot of what was referred to as “interesting” supplementary English materials available on the Internet. Some respondents used resources in English to prepare for their lessons rather than to instruct students. Interestingly, our findings show that 43.80% (n=53) of those who stated that they “almost never” or “seldom” employed EMI in their classroom (n=121) used Japanese-English textbooks in their practice.

One of the pre-determined statements, which turned out to be the most debatable, was that learners concentrated more on foreign languages when EMI was employed. Only one-fourth of the teachers supported this idea.

Conversely, the question about the negative aspects of EMI received 189 responses and comments. Twelve teachers refrained from answering the question.

As

Figure 4 demonstrates, more than half of the respondents indicated the first two statements as their primary concern, namely, insufficient English language proficiency of students as well as the absence of direct equivalents to some words and grammar patterns.

Most research studies that focused on instructors’ views regarding EMI have found that inadequate English language proficiency among students is a significant challenge for teachers conducting EMI classes. Borg (2016) found that beginner or elementary English levels were insufficient for studying an academic subject in English and argued that effective implementation of EMI requires intermediate or upper-intermediate levels of English proficiency.

Having analysed the participants’ qualitative comments, we can conclude that their students’ poor English proficiency prevented many respondents from using EMI to the desired extent. Such comments were received from France, Italy, Taiwan, and some Spanish-speaking countries. This overall situation regarding the level of language proficiency contrasts with that in the other commentaries from such countries as Romania, Slovakia, Turkey and, expectedly, India, where the teachers stated their students’ level to be sufficient (B1-B2). However, students’ relatively low level of English did not prevent the teachers from employing it occasionally. One participant commented: “I think it can be beneficial to students here and there. That is why I push English words along with their Japanese equivalents.”

Besides the disadvantages mentioned in the figure above, some participants commented that it was better for them to explain grammar in their native language due to existing similarities with Japanese or simply because it is easier than doing so in English.

Although English often functions as a medium of instruction in India, starting from secondary education, it is not necessarily a primary language of instruction for Japanese lessons. One comment from a participant stated:

Typologically, English is a subject-verb-object language, whereas Japanese and languages in India are ‘subject-object-verb’ languages. They share many language universals. Word order and many phrases are closer to that of Japanese. Many cultural concepts are similar. Therefore, students are encouraged to think in their respective Indian languages while translating or forming sentences in Japanese.

Similarly, Rothman (2010) concludes in his study on L3 syntactic transfer selectivity and typological determinacy that typological proximity is the most decisive factor determining multilingual syntactic transfer, and L3 transfer is driven by the typological proximity of the target L3 measured against the other previously acquired linguistic systems. Furthermore, in the participants’ qualitative comments, the role of the native language and a teacher’s general preference for it were pointed out based on the similarities between L1 and L3: “Teaching Japanese to students who speak Finnish as their native tongue is very rewarding because there are so many similarities in the languages. The students understand the structure of the Japanese language easily, and their progress is very quick.” Using the native language instead of EMI is also favoured in universities where Japanese is studied as a major. As students are supposed to become specialists in translating, it helps to develop their translation skills.

Although many teachers preferred to use a mixture of three languages (the target Japanese, L1, and English), some comments mentioned four languages being used. They divide explanations so that grammar is taught through the vernacular languages, and English is used for memorising words (primarily nouns). This was followed by another concern: “Confidence in speaking Japanese is reduced if English is primarily used from the beginning. Students tend to translate English into Japanese in their minds. The transition to speaking reasonably in Japanese will take many years.” Another comment supported the idea that direct translation from English has disadvantages: “Students tend to rely more on translating sentences in English into Japanese to express themselves, which often results in students using incorrect Japanese.”

There was a concern regarding grammar explanation: “English explanation of such grammar patterns as causative form (shieki), giving and receiving (yarimorai), and transitive/intransitive verbs (jidōshi/tadōshi) can be a bit difficult for students.” One teacher did not find it helpful to explain Japanese grammar via English “because the languages are so different”. Another respondent assumed: “Students can become over-depending on English as a language medium, especially at N2 [upper-intermediate] and N1 [advanced] levels”. One teacher thought, “… learners’ Japanese proficiency is slowed down tremendously”. Two participants could not find any specific disadvantages but said teaching only in Japanese would be better even with beginner students, adding that clarification could be made with the help of gestures and picture cards.

Interestingly, among all the responses, there were no concerns that English might pose a threat to the home language and substitute it, as it was one of the concerns for rejecting EMI in some countries mentioned in other studies (Dearden, 2014).

Discussion

Carrying out this large-scale research remotely via emails had a number of challenges, such as the participants’ misunderstanding of the key notions of EMI and multilingual classrooms, restricted access to Google Forms in China and, on top of all, a low response rate. The latter necessitated sending emails twice as a reminder to all the countries. Out of 141 countries and regions implementing Japanese-language education overseas, we contacted as many as 122 countries and all the registered Japanese language education institutions (The Japan Foundation, 2021, 2023).

From the beginning, in August 2023, when the pilot survey was conducted, we became aware of the complexity of the research. During that period, if inconsistencies were found, we had an opportunity to ask the corresponding participants for subsequent short interviews in order to identify the flaws the composed questionnaire had and to minimise the possibilities of misleading interpretation of the questions (as was the case with understanding the term “multilingual class”).

Due to the controversy of the research topic, we were interested in learning teachers’ attitudes and perceptions towards EMI practice. We included open-ended questions to find out the pros and cons of EMI as well as the overall beliefs of the respondents, who were also allowed to openly express their opinions on EMI used in Japanese language classrooms in the space provided at the end of the questionnaire. We received extensive feedback in the form of commentaries from the Japanese language teachers.

As a result of our study, we identified some positive attitudes towards EMI among the Japanese language teachers. The majority of the non-native Japanese language teacher respondents held the belief that it was helpful to provide equivalents of grammar patterns and words in English. Therefore, English is used to enhance input morphologically, syntactically, and lexically. Promoting students’ mobility and being helpful in multicultural classrooms were also two of the top-mentioned benefits. Approximately the same ratio of the teacher respondents believed there were also instrumental advantages to studying through the English medium, and it was beneficial for students to develop two foreign languages simultaneously. Compensation for lack of resources in L1 was also mentioned as a positive motivation for using EMI. One more long-term positive impact on content learning was found: code-switching between three languages (L1, English, and Japanese) minimises misunderstanding of the content students attempt to learn. The likelihood of poorly understood content is higher when it is learned through Japanese only.

The respondents generally had mixed opinions regarding the usage of EMI in Japanese language classrooms. Interestingly, the participants from countries traditionally speaking English as a second native language, such as India, stated that they found it more beneficial to use their first native language (i.e., Hindi or Marathi) for instructions because of more grammar similarities and English was claimed to be “just a mode of communication.” On the other hand, those participants who teach in countries where students have a less proficient command of English, such as Brazil, pointed out its usefulness as L2 in learning Japanese as L3. Remembering their student experience, one participant with level B1 at the time commented, “It was easier to study Japanese through English because it helped to comprehend the grammar better”. These positive attitudes towards translanguaging discursive practices were mentioned in the previous studies (Baker, 2001; Turnbull, 2018; Galloway et al., 2020).

The primary language of instruction in foreign language teaching has always been a topic for discussion. The analysis of the views expressed by the participants showed interest in the results of the current study. Moreover, some teachers were willing to know whether their methodology in EMI usage was approved by most or not.

The present study did not give voice to students’ opinions of EMI in multilingual and multicultural settings, and their beliefs and attitudes are yet to be explored.

Conclusions

The significant number of the responses from different geographical settings allowed us to draw the conclusions that might not otherwise be possible in smaller-scale studies. We could find the use of EMI by non-native Japanese language teachers in all geographical areas of the world, although there are a few countries where it is less prominent. In our study, we proceeded from the fact that the implementation of EMI in JFL classrooms was mainly driven by teaching staff rather than institutional-level policy.

Based on the data analysis, we determined strong correlations between the extent to which EMI was employed and the multilingual classroom. Our findings suggest that EMI becomes particularly helpful in multilingual classrooms where most teachers employ it substantially. The results showed a significant difference in the amount of instructional time that English was employed in multilingual and non-multilingual classrooms. Even though the teachers are non-native English speakers, most support English use because it helps students to understand the third acquired language better. English began to be perceived as a transitional instrument or a bridge connecting the native language and the target language.

In JFL classrooms, the target Japanese language skills are developed through translanguaging (interpreting, translation, code-switching), which is a widespread method that instructors employ to promote a more profound and fuller understanding of the subject. This is what distinguishes the EMI in JFL classrooms from the monolingual EMI approach employed in other academic subjects.

The limitation of the study is that the sample could not be carefully chosen and consisted of the participants who voluntarily answered the questionnaire. Thus, it cannot be regarded as a complete representative of the overall population of non-native Japanese teachers. As the present study aimed to explore teachers’ perspectives, further empirical research is required to investigate students’ perspectives in different geographical areas worldwide.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under the project No. 09I03-03-V01-00071. We also acknowledge the support of the Japan Foundation Japanese-Language Institute in Urawa. We are grateful to Prof. Naoko Shibamoto for her constructive feedback when the questionnaire was compiled. Our thanks also go to all the respondents worldwide who were willing to help with our research and decided to share their beliefs based on their valuable experience.

References

- Aizawa, I., & Rose, H. (2019). An analysis of Japan’s English as medium of instruction initiatives within higher education: The gap between meso-level policy and micro-level practice. Higher Education, 77, 1125–1142. [CrossRef]

- Alba de la Fuente, A. & Lacroix, H. (2015). Multilingual learners and foreign language acquisition: Insights into the effects of prior linguistic knowledge. Language Learning in Higher Education, 5(1), 45-57. [CrossRef]

- Ament, J. R., Barón-Parés, J., & Pérez-Vidal, C. (2020). Exploring the relationship between motivations, emotions and pragmatic marker use in English-medium instruction learners. Language Learning in Higher Education, 10(2), 469-489. [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. (2001). Foundation of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism (3d ed.). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Borg, S. (2016). English Medium Instruction in Iraqi Kurdistan: Perspectives from Lectures at State Universities. British Council.

- Brenn-White, M. & Faethe, E. (2013). English-taught master’s programs in Europe: A 2013 Update. New York: Institute of International Education. https://www.iie.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/English-Language-Masters-2013-Update.pdf.

- Bruen, J., & Kelly, N. (2017). Mother-tongue diversity in the foreign language classroom: Perspectives on the experiences of non-native speakers of English studying foreign languages in an English-medium university. Language Learning in Higher Education, 7(2), 353–369. [CrossRef]

- Brutt-Griffler, J. (2017). English in the multilingual classroom: Implications for research, policy and practice. PSU Research Review: An International Journal, 1(3), 216-228. [CrossRef]

- Dearden, J. (2014). English as a medium of instruction: A growing global phenomenon. London, England: The British Council. https://www.britishcouncil.es/sites/default/files/british_council_english_as_a_medium_of_instruction.pdf.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. (2015). Language teaching and learning in multilingual classrooms. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/766802.

- Fang, F. & Widodo, H. (2019). Critical Perspectives on Global Englishes in Asia: Language Policy, Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters. [CrossRef]

- Galloway, N., Numajiri, T., & Rees, N. R. (2020). The ‘internationalisation’, or ‘Englishisation’, of higher education in East Asia. Higher Education, 80, 395–414. [CrossRef]

- Goya, H. (2020). Impact of English as Medium of Instruction (EMI) in EFL: To What Extent Does Teaching in English Affect Thinking Process of EFL Learners? Ryudai Review of Euro-American Studies, 64, 59–84. [CrossRef]

- Hall, G., & Cook, G. (2012). Own-language use in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching, 45(3), 271–308. [CrossRef]

- Heugh, K., French, M., Armitage, J., Taylor-Leech, K., Billinghurst, N., & Ollerhead, S. (2019). Using multilingual approaches: Moving from theory to practice. A resource book of strategies, activities and projects for the classroom. British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/Using_multilingual_approaches.pdf.

- Kapranov, O. (2021). Discursive Representations of Education for Sustainable Development in Policy Documents by English Medium Instruction Schools in Estonia and Norway. Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, 12(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.2478/dcse-2021-0005. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, N. (2021). Student Motivation in English-Medium Instruction: Empirical studies in a Japanese University. Routledge Focus.

- Lin, A., & Lo, Y.Y. (2018). The spread of English Medium Instruction programmes. In Barnard, R., & Hasim, Z. (Eds.), English Medium Instruction Programmes: Perspectives from South East Asian Universities (1st ed., pp. 87–103). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Luchenko, O., Bogdanova, H. (2023). Teaching the Japanese language in multilingual classrooms – EMI approach. Scientific Collection «InterConf». Proceedings of the 14th International Scientific and Practical Conference «Science and Practice: Implementation to Modern Society, 152, 110-113. https://archive.interconf.center/index.php/conference-proceeding/issue/view/26-28.04.2023.

- Macaro, E., Curle, S., Pun, J., An, J., & Dearden, J. (2018). A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher education. Language Teaching, 51(1), 36–76. [CrossRef]

- Masuda, M. (2019). Justifying and Incorporating the Judicious Use of L1 in Japanese School Education for Foreign Languages (А № 4596) [Doctoral dissertation, Niigata University].

- Mori, Y., & Mori, J. (2011). Review of recent research (2000–2010) on learning and instruction with specific reference to L2 Japanese. Language Teaching, 44(4), 447-484. [CrossRef]

- Peyton, J. K. (2015). Language of Instruction: Research Findings and Program and Instructional Implications. Reconsidering Development, 4(1). https://pubs.lib.umn.edu/index.php/reconsidering/issue/view/57.

- Rothman, J. (2010). L3 syntactic transfer selectivity and typological determinacy: The typological primacy model. Second Language Research, 27, 107–127. [CrossRef]

- Sanz, C., & Cox, J. G. (2017). Laboratory studies on multilingual cognition and further language development. Language Teaching, 50(1), 65-70. [CrossRef]

- The Japan Foundation. (2021). Survey 2021: Search engine for institutions offering Japanese-language education. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://www.japanese.jpf.go.jp/do/index.

- The Japan Foundation. (2023). Survey Report on Japanese-Language Education Abroad 2021. The Japan Foundation. https://www.jpf.go.jp/e/project/japanese/survey/result/dl/survey2021/All_contents_r2.pdf.

- Turnbull, B. (2018). The use of English as a lingua franca in the Japanese second language classroom. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 7(1), 131–151. [CrossRef]

- Vural, S., & Ölçü Dinçer, Z. (2022). English Medium Instruction: Policies for Constraining Potential Language Use in the Classroom and Recruiting Instructors. International Journal of Educational Spectrum, 4(1), 13-30. https://doi.org/10.47806/ijesacademic.1000913. [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. (2001). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 3rd edn (Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).