1. Introduction

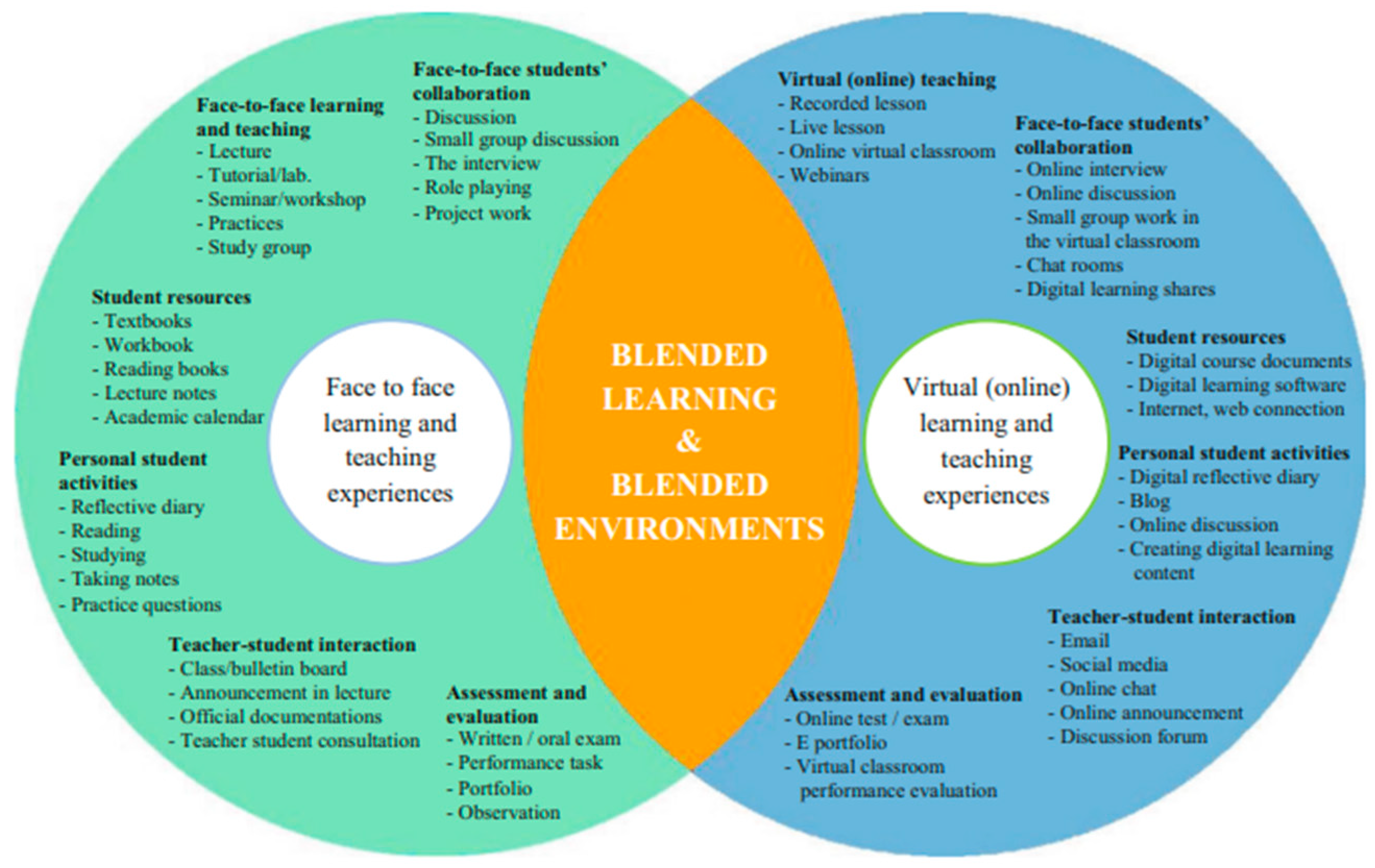

Higher education institutions worldwide have been increasingly adopting blended learning approaches that integrate online and face-to-face instruction. According to Garrison and Vaughan (2008:5): ‘’[b]lended learning – a design approach whereby both face-to-face and online learning are made better by the presence of the other – offers the possibility of recapturing the traditional values of higher education while meeting the demands and needs of the twenty-first century’’. Blended learning provides flexibility, promotes learner engagement, and enables personalised learning experiences (Graham, 2006). Şentürk (2021) states that a blended learning model has the potential to enable individuals to become lifelong learners. As illustrated in the

Figure 1 below, this hybrid approach combines the benefits of in-person teaching with the advantages of technology-mediated learning. Specifically, the face-to-face components provide peer collaboration, instructor interaction, and hands-on practice. Meanwhile, the online portions offer self-paced learning, expanded resources, and opportunities to develop technological skills. By integrating these two modalities, blended learning provides a diversified environment for undergraduates to take control of their own learning process. As Şentürk notes, this can nurture skills for continuous, self-motivated education beyond graduation.

As more universities in Saudi Arabia use blended learning to deliver their courses especially after Covid 19, there are growing calls to utilise blended learning to enhance teaching and learning in both schools and higher education institutions . Moreover, a translation curriculum requires developing not just linguistic skills but also cultural understanding, specialised knowledge, and technology competencies which can benefit of course from blended instruction. However, effective implementation of blended learning for translation students in the Saudi context requires addressing certain technological, pedagogical and cultural challenges.

This paper analyses opportunities and challenges associated with blended learning for undergraduate translation students at Saudi universities. First, it reviews literature on blended learning models in translation programs and their outcomes in higher education. Next, it discusses proposed blended learning designs for undergraduate translation courses in Saudi Arabia, with specific reference to the case for undergraduate translation programs at the university of Jeddah. Finally, challenges related to technology infrastructure, pedagogical challenges and faculty readiness, and educational culture and student engagement are then examined with recommendations for implementing blended learning to improve learning experiences and outcomes for translation students in the Saudi context.

2. Review of Literature

Several studies have explored the effectiveness of blended learning in postgraduate and undergraduate translation programs. Galán-Mañas and Albir (2010) conducted an empirical study evaluating a blended learning model for translator training. They found the blended format improved students’ acquisition of instrumental, interpersonal, and systemic competencies compared to traditional instruction. Using the example of an MA programme in Australia, Gerber and Tobias (2020) also agrees with them and advocated for blended learning to train professional translators, emphasising the need for technological competence and how this will facilitate the development of skill sets necessary for 21st century translators. Motta (2016) implemented a blended learning environment based on deliberate practice in interpreter training. This blended model enhances the development of key interpreting skills and “promotes a collaborative approach to learning by means of activities anchored in real context and helps learners become autonomous, meta-cognitive and self-regulated” (Motta,2016, p. 133).

Other studies also have focused on how blended learning can aid the integration of technology into translation curricula. Nitzke, Tardel, and Hansen-Schirra (2019) described DigiLing project, a blended learning program (which contains 6 online courses) designed to teach domain specific digital competencies needed by modern translators, including localization in the digital age and post-editing machine translation. According to Nitzke et.al. (2019) “research involving evaluations and learning success outcomes will show how efficient this kind of training can be for students as well as translator trainers” (p.303). Lee and Huh (2018) examined a blended translation and interpreting for specific purposes certificate program in South Korea, based on surveys and interviews. They found blended instruction facilitated expanded use of learning management systems and trainees were generally positive and satisfied with the online classes, while trainers had mixed views on the online teaching and learning. It also suggests ways to improve the online T&I training for specific purposes.

More recent studies have continued investigating blended learning in translation training programs, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yang (2021) proposed blended learning as an effective approach for high-quality translation courses in the post-pandemic era. The authors argue that blended learning can provide flexibility, continuous learning, and improved student-teacher relationships. However, it requires self-discipline from students and more preparation from teachers. Yang (2021) sees blended learning as beneficial but still has challenges to overcome and more research is needed on applying blended learning specifically to translation courses in the post-pandemic era. Furthermore, Peng et al. (2023) examined the application of blended learning in a Chinese-English translation course to enhance translation competence. Using a quasi-experimental design encompassing a translation test and questionnaires, the researchers observed that the blended learning approach significantly enhanced students' knowledge, technological, and professional competencies in translation. Students also reported high satisfaction with the blended format's appropriateness, sustainability, and multimodality. Although the findings were predominantly positive, Peng et al. (2023) acknowledged certain limitations, such as students displaying an overreliance on external resources rather than relying on internal support and critical thinking in decision-making processes. This highlights the necessity for additional training to foster the effective utilisation of instrumental resources and the management of internal support Overall, this recent study demonstrates the potential of blended learning in undergraduate translation programs. It reinforces the significance of collaborative translation work in pedagogy by simulating professional translation settings through role-play and project administration, distinguishing this practice from traditional pair or group work. Another recent study by Ribeiro et al. (2023) examined specifically the use of project-based learning (PBL) in online translation courses as a strategy for developing competencies and self-regulated learning during the pandemic. Implementing PBL online, they compared student self-regulation before and after the course over three academic years. While no significant pre-post differences were found initially, their longitudinal analysis of the three school years showed improved self-regulation , with the exception of time management. Ribeiro et al. (2023) conclude that online PBL can simulate real-world translation environments and improve competencies like self-regulation. However, they note limitations like the quasi-experimental design and low student participation in later years. Their study provides additional evidence that carefully structured blended learning approaches can cultivate critical translator competencies, even when forced online due to COVID-19.

Overall, current research clearly supports implementing blended learning in translation classes. The literature review demonstrates blended approaches facilitate teaching both translation competencies and technological skills critical for today's translators and interpreters. They showed evidence indicating blended learning benefits translation students and should be further incorporated into translation programs. However, most of these translation researches are course-level or program-level but not institution-level blending, which I am going to discuss in the next section with presenting a case study from the University of Jeddah.

3. Methodological Approach

This study employs a qualitative case study approach to examine the integration of blended learning in an undergraduate translation program. Data was gathered through direct observation of blended translation classes at the University of Jeddah over one academic year. The researcher observed a total of 168 instructional hours across 4 translation courses ( Introduction to Translation - Research Methods in Translation- Translation Theory- Political & Diplomatic Translation); they were taught at the third and fourth year levels which utilised blended formats. Detailed field notes were taken during the observations to record the structure of blended lessons, instructors' and students' actions, the types of activities performed, and any challenges encountered. The qualitative methodology provided nuanced, experientially grounded insights into how blended learning is functioning in undergraduate translator training. However, it is imperative to acknowledge the inherent subjectivity and limitations associated with this method. It is crucial to recognize that the interpretive nature of qualitative methodology introduces a subjective dimension, and the observations are specific to the context of the University of Jeddah's translation program. As such, the outcomes may not be universally generalizable, and caution should be exercised in projecting them beyond the limits of this particular educational setting.

4. Case Study: University of Jeddah

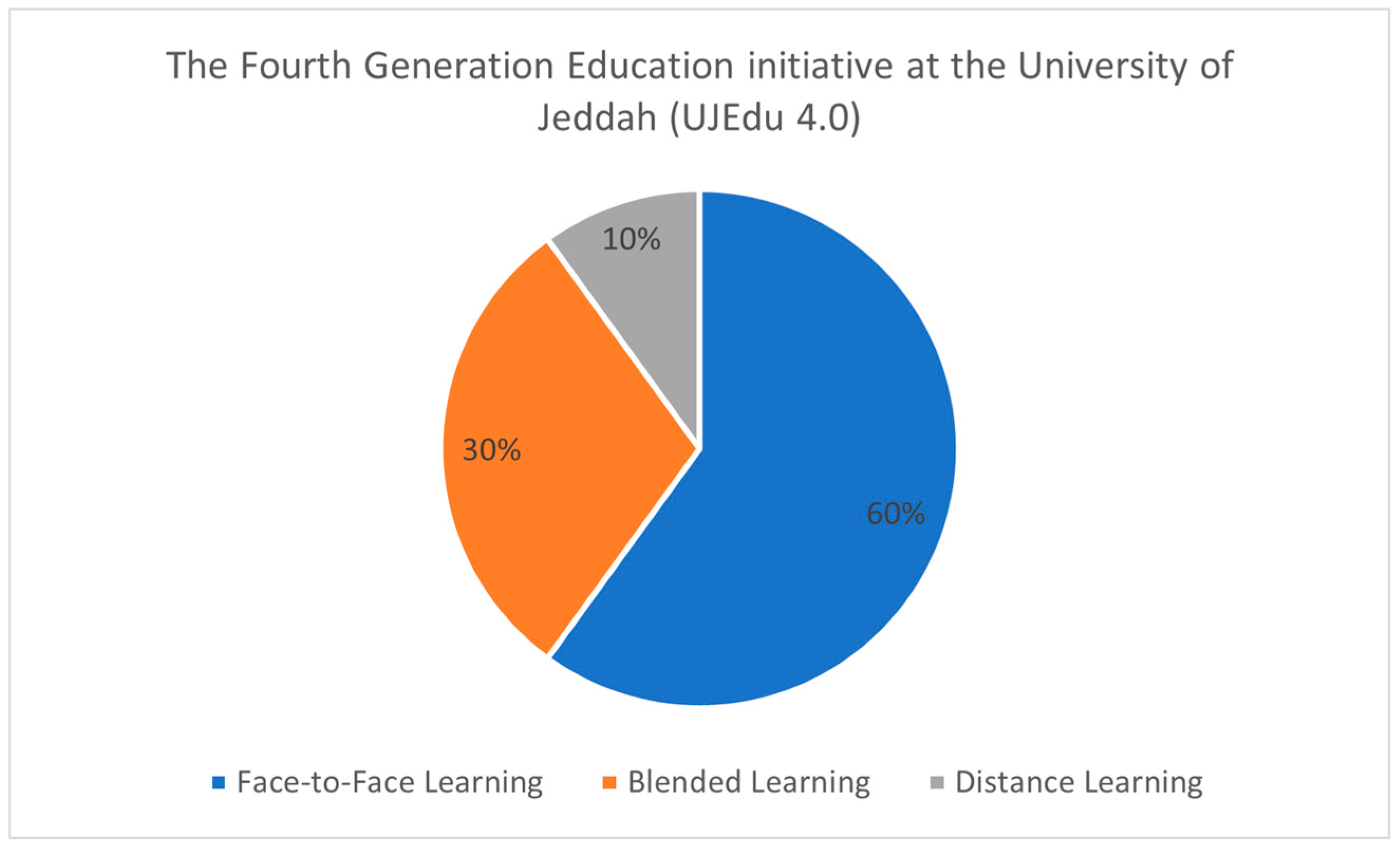

As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, higher education institutions around the world are incorporating online and blended learning into their programs especially after the pandemic to provide greater flexibility for students and enhance learning outcomes. The University of Jeddah in support of this has launched an initiative called The Fourth Generation Education initiative at the University of Jeddah or UJEdu 4.0 to implement blended learning across undergraduate and postgraduate programs. The UJEdu 4.0 initiative aims to create a flexible learning system that integrates three main educational delivery modes - face to face, blended, and distance learning. The goal is to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of learning by leveraging the strengths of each model (University of Jeddah, 2022).

Under the initiative and as stated in

Figure 2, 60% of course content will be delivered face-to-face (3 days for traditional learning, 30% will be delivered online through the learning management system Blackboard, and 10% will be delivered fully online (which means two days for synchronous and asynchronous e-learning). This blended model provides flexibility for students while maintaining significant in-person contact and support.

A key component of the UJEdu 4.0 initiative is redesigning the curriculum to determine which parts of each course are best suited for online versus in-person delivery. Faculty members complete a template analysing the learning outcomes and topics of each course and recommending the appropriate delivery mode for each one. Recommendations are reviewed by department curriculum committees to make final determinations. In general, theoretical components of the curriculum are being moved online, while applied, skills-based topics remain face-to-face. Assessments are being designed to align with the delivery mode for each section. For example, knowledge acquisition may be assessed online, while practical skills are evaluated in the classroom. However, it is up to the department to decide the blended percentage for its programs.

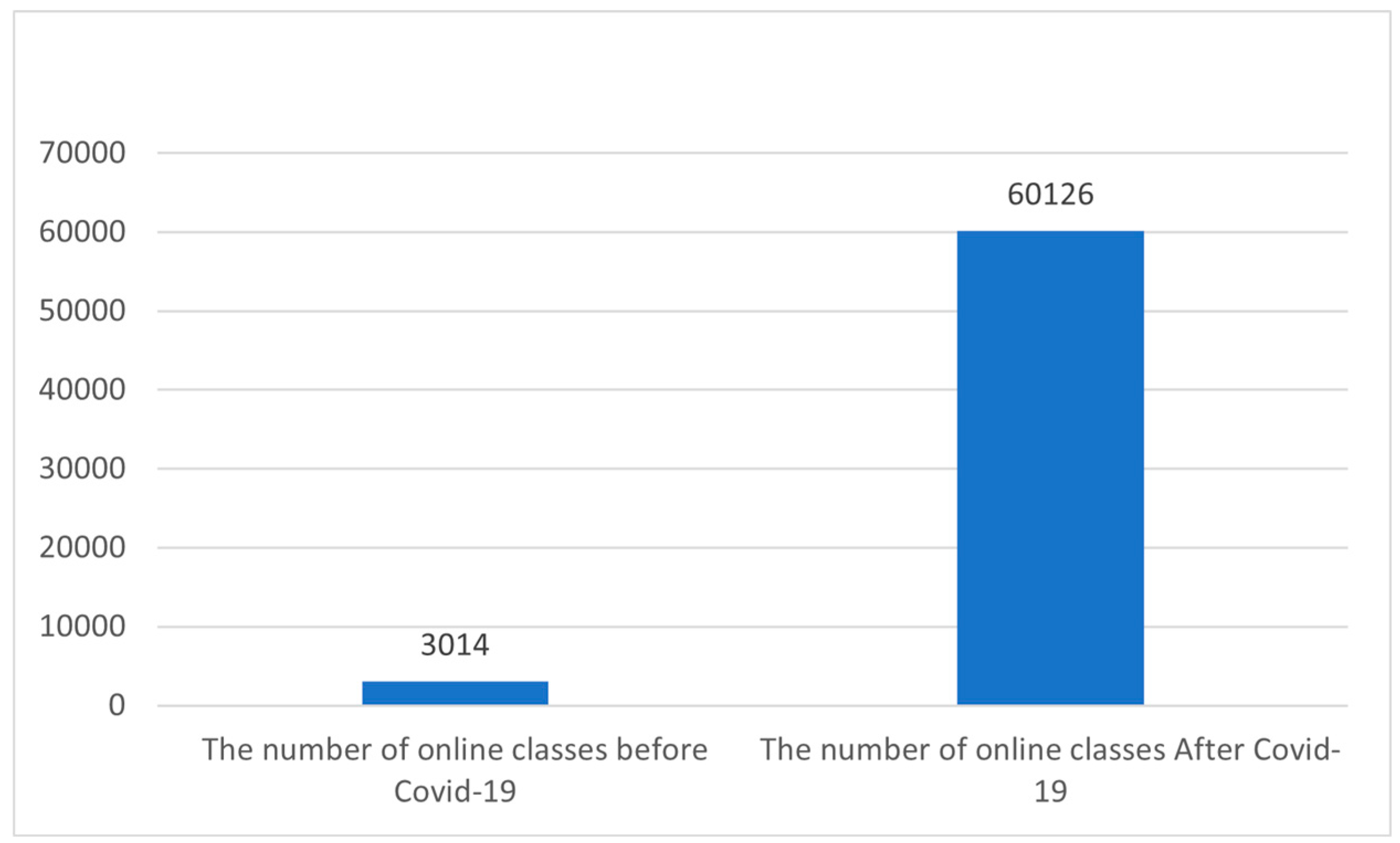

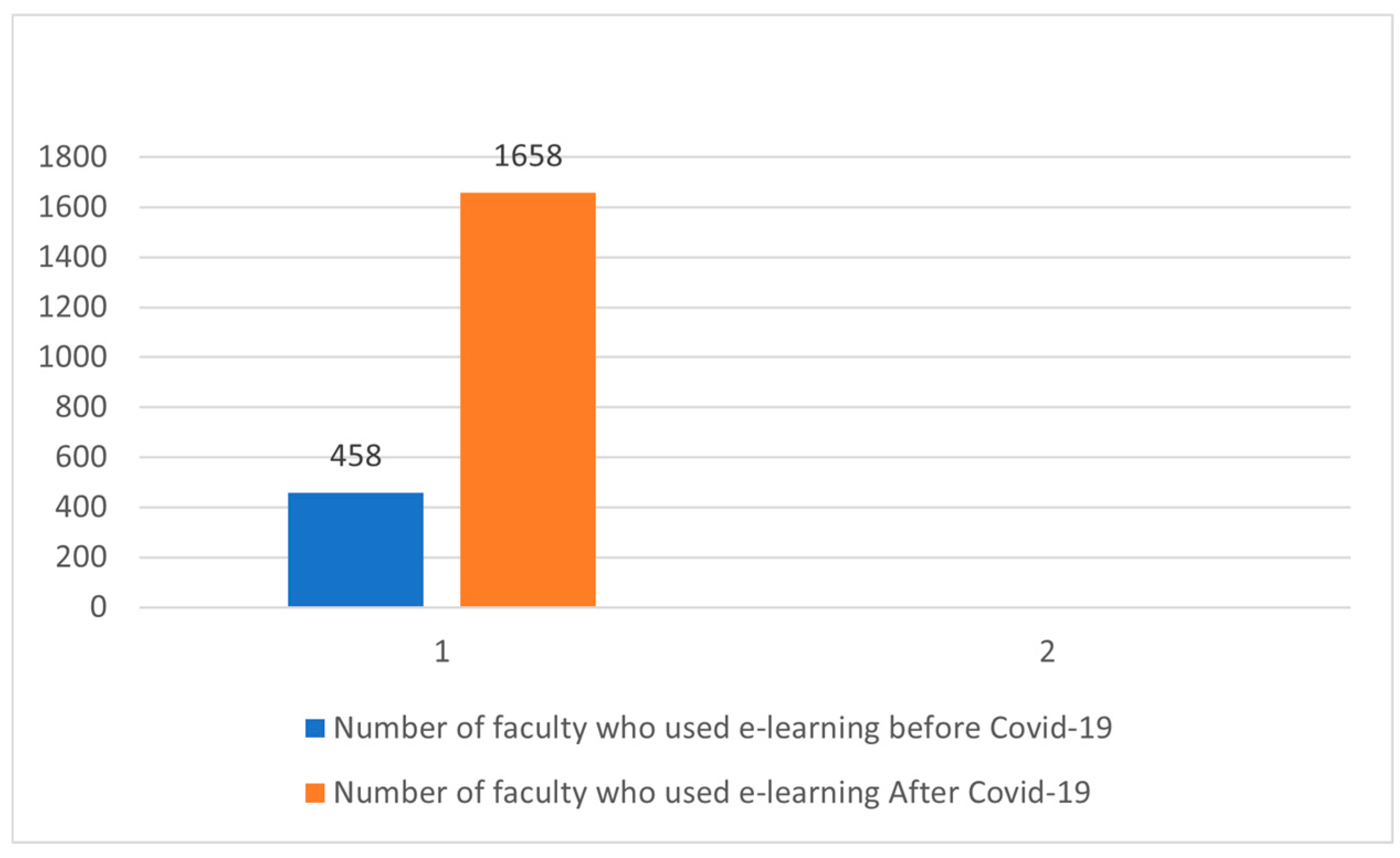

The UJEdu 4.0 initiative is being implanted in a number of undergraduate courses including the translation undergraduate program starting in the academic year 2021/2022. Early findings indicate positive results, with high levels of faculty and student engagement online. For example, according to The UJEdu report the number of online classes increased from 3014 prior to the initiative to 60126(see

Figure 3), the average number of faculty who used blended and online learning increased from 458 to 1658 (see

Figure 4), and average of student interaction increased from 82 per student to 257 interactions after implementation (University of Jeddah, 2022). To my knowledge further evaluation will be conducted at the end of the pilot period.

In relation to the undergraduate translation program, the total duration is 128 hours. In the program plan, which has been redesigned according to the UJEdu 4.0 initiative, 96 hours, equivalent to 75%, have been allocated for traditional classroom learning, while 32 hours, amounting to 25%, have been designated for blended and distance learning. Distance learning comprises a lower percentage and is primarily associated with first- and second-year subjects such as Academic Skills, Islamic Culture, and Arabic Language. On the other hand, blended learning is more prominent in the third and fourth years, encompassing courses like Introduction to Translation, Translation Theory, Terminology & Arabization, Language & Culture, Research Methods in Translation, and optional subjects such as Political & Diplomatic Translation or Translation of Islamic Texts.

5. Discussion

The present study examined blended learning perceived benefits and challenges based on 168 hours of instruction across third and fourth year courses. The results provide valuable insights into the potential of blended learning to enhance translation pedagogy, but also reveal areas needing further research and instructor support as will be discussed in the following section.

5.1. Benefits of using blended learning in translation classes

The use of blended learning, observed during the instruction of a translation undergraduate program at the University of Jeddah, revealed several significant benefits for translation classes Firstly, blended learning can provide students with more flexibility in terms of when and where they learn. This is particularly important for translation students who often have to work independently and on their own schedule. Blended learning allows students to access course materials and resources online, which means they can learn at their own pace and at a time that suits them.

Secondly, blended learning can enhance the learning experience by providing students with a range of different learning activities. For example, students can engage in online discussions, attend live lectures, complete online quizzes and exercises, and participate in collaborative projects. For example, completing online quizzes one and two in blended modules like Translation Theory and Introduction to Translation. This variety of learning activities can help to keep students engaged and motivated, as well as providing opportunities for students to develop different skills and knowledge.

Thirdly, blended learning can facilitate the incorporation of technology into translation classes. Technology is an increasingly important aspect of the translation industry, and it is essential that translation students are familiar with the latest tools and software. Blended learning provides opportunities for students to learn how to use different translation software and tools, as well as developing other technological skills that will be useful in their future careers.

5.2. Challenges and Recommendations

As the case study of the University of Jeddah showed, implementing effective blended learning for translation students in Saudi Arabia requires addressing several potential barriers:

1- Technological Challenges: Reliable access to the internet and computers is essential for the online dimension of blended courses. Universities must provide up-to-date technology infrastructure and technical support. Teachers need training in online pedagogies and tools. Introductory courses on using Learning Management Systems could be provided to students as well. Having said that, it is important to mention that Covid-19 facilitated the adaptation of both students and instructors to online learning and enabled the seamless integration of blended learning.

However, blended designs should remain simple and not overwhelm students or faculty with numerous unfamiliar tools. For example, from the study classes delivered to third and fourth-year students, a suggestion would be: using interactive websites such as Menti for word clouds, polls, rankings, etc.; employing cloud-based translation and localization platforms like Smartcat and Phrase; utilising cloud-based terminology extraction tools such as Interpreterhelp and Sketch Engine; integrating cloud-based video feedback and interpreting software like GoReact or simple phone recorders; employing graphic design platforms like Canva; and leveraging Google applications for collaboration, such as Google Docs, Google Sheets, and Google Forms for research and surveys. For instance, in Political & Diplomatic Translation, students in online classes are asked to complete exercises or translate given texts and post them in the discussion board, then collaboratively discuss them together. This approach must be emphasised to have been effective for two reasons: it ensures students' engagement in the classes and trains them for the visibility of their translations in the future, where they will be read publicly and criticised. This process helps in developing objective, unbiased criticism skills.

2- Pedagogical Challenges: Traditional teacher-centred approaches may not transfer well to blended environments, specifically in translation where it is moved from teacher-centred to learning-centred methods (Secară et al., 2009). Teachers must adapt to facilitating active learning and student autonomy online and in-person; and understand the clear cut difference between emergency teaching that was practised during the pandemic and blended learning. They will need more training and guidance on redesigning courses, activities, and assessments to leverage technology while retaining in-person interactions. More formal training programs on blended learning principles, models, and best practices can build capacity among faculty. More training related to teaching translation and creating blended resources for Translator Training is deemed to be helpful for translation academics based on what was precisely found.

3- Cultural Challenges: Saudi Arabia’s educational culture has traditionally emphasised passive learning, rote memorization, and teacher authority (Hamdan, 2014). Students may resist blended learning if they are unaccustomed to independent, self-directed learning. Teachers must encourage student responsibility and engagement in blended courses through interactive online activities, for example using as we did Project Based Learning (PBL). For example, in collaboration with WikiHow platform (

https://www.wikihow.com), students translated a number of articles on mental health from English into Arabic from March-April 2022, and with the help of WikiHow team their translated articles were published later in the Arabic version of the website. It was noticed that PBL learning environments, as also concluded in Ribeiro et al. (2023), can effectively simulate real-world translation scenarios and enhance competencies such as self-regulation in students.

Teachers should also demonstrate the great benefits of blended learning for developing translation and translation technologies skills. Obtaining institutional support and promoting a culture of technology-enabled learning can help overcome these cultural challenges.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes blended learning can improve undergraduate translation education at Saudi universities by facilitating personalised, interactive learning experiences. Challenges remain in terms of infrastructure, pedagogy, and culture, but can be mitigated through careful planning, training, and policy. As digital tools continue transforming education globally, blended learning presents an opportunity to enhance how translation students in Saudi Arabia develop the knowledge, skills, and character needed for professional success. Ongoing evaluation will be needed to determine optimal blends for each course and student level.

References

- Secară, A.; Merten, P.; Ramírez, Y. What’s in Your Blend? Creating Blended Resources for Translator Training. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 2009, 3, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Vaughan, N.D. Blended learning in higher education: Framework, principles, and guidelines; John Wiley & Sons, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, L.; Tobias, S. ‘Blended learning’ in the training of professional translators. Translatalogia: Issue 1/2020 2020, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Galán-Mañas, A.; Albir, A. H. Blended learning in translator training: Methodology and results of an empirical validation. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 2010, 4, 197–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.R. Blended learning systems. The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs 2006, 1, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan, A. The reciprocal and correlative relationship between learning culture and online education: A case from Saudi Arabia. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 2014, 15, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Huh, J. Why not go online?: A case study of blended mode business interpreting and translation certificate program. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 2018, 12, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, M. A blended learning environment based on the principles of deliberate practice for the acquisition of interpreting skills. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 2016, 10, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzke, J.; Tardel, A.; Hansen-Schirra, S. Training the modern translator–the acquisition of digital competencies through blended learning. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 2019, 13, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Hu, M.; Bi, P. Investigating blended learning mode in translation competence development. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.; Tavares, C.; Lopes, C.; Chorão, G. Competence development strategies after COVID-19: Using PBL in translation courses. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şentürk, C. Effects of the blended learning model on preservice teachers’ academic achievements and twenty-first century skills. Education and Information Technologies 2021, 26, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Jeddah. (2022). UJEdu 4.0: The Fourth Generation of Education at the University of Jeddah. Unpublished internal document.

- Yang, C. A study on blended learning of high-quality translation courses in the post-epidemic era. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences, 2021; Volume 253, p. 01073. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).