1. Introduction

Over twenty years of scholarship on the neoliberalism of higher education has captured its features, such as the corporate university, the entrepreneurial university, and the neoliberal university [

1,

2]. In neoliberal contexts, funding allocations for higher education have typically focused on competitive mechanisms. While higher education is funded directly by the state, it is usually seen as serving public goods, such as reducing inequality and increasing social mobility. Therefore, public goods-related policy initiatives seek to reframe higher education as interrelated with the well-being of society [

3,

4,

5]. Several governments have adopted the format of a national strategy or development plan by setting out national objectives for better alignment with higher education institutes, for instance, in Ireland, the Netherlands, Finland, and New Zealand [

6]. On neoliberal campuses, competition and evaluation are overemphasized. This phenomenon has received numerous criticisms [

7,

8,

9,

10]. This study may provide a better understanding of the transformation from neoliberalism to public goods in the pursuit of sustainable higher education.

In addition, Eryaman and Schneider argue that research associations can promote the use of research to service public goods [

11]. Some nationwide and international associations have focused on this issue; for example, the Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE) identifies its vision of enhancing public goods by promoting, supporting, and improving research [

12]; the American Educational Research Association (AERA) recognizes the promotion of research to serve public goods as the fundamental responsibility of the association [

13]. Based on this, transferring public resources into higher education properly for public goods purposes has become a pertinent issue. Surprisingly, much less attention has been paid to verifying the effect of the allocation of resources through public goods in higher education settings. This study provides an alternative means to detect specific funding allocations for public goods purposes, which will provide a deeper understanding of this issue.

The funding policies in higher education are varied; for example, the UK has a different approach to that adopted in Germany, Italy, and the United States. Even the similar higher education systems in Japan and South Korea have specific considerations and differences. Taiwan is part of a different socio-political constellation, based on and driven by different value sets than neoliberal societies. Taking Taiwan’s Higher Education Sprout Project (HESP) as an example, this study explores how far the specific funding allocation can be transferred with the public goods implemented in higher education. The HESP (from 2018 to 2022, stage I) was established in 2017; it intends to transfer public goods as a policy-driven tool for sustainable institutes in higher education [

14,

15]. It represents a different direction for higher education that is aligned with sustainable policy. In this study, we argue that higher education for public goods purposes should consider balancing their teaching and research, caring for disadvantaged students to increase social mobility, and balancing global competition and local needs in terms of fulfilling social responsibility. This implies that higher education can be expected to achieve sustainable development under the specific funding allocation mechanism.

This study assumes that transforming public goods through special funding can play a critical role in neoliberal higher education, regardless of the sector. If the transformation model, ITO (input, transform, and outcome), works well, this suggests that public good initiatives can be implemented in higher education to achieve sustainable development. Therefore, this study focuses on specific policy implementation and uses the case study as an example to discover new knowledge in this field. If this approach is successful, the findings may encourage higher education institutes to commit to expanding learning opportunities for all, such as UNESCO’s SDG proposal for Education 2030. The purposes of this study include discovering the influential factors that exist in the funding allocation scheme and detecting the differences in funding allocation between systems and sectors, examining the effect of public goods transformation, and finally, proposing better public goods strategies for higher education to achieve sustainable development. With these purposes in mind, the research questions to answer are as follows:

a. What are the influential factors in funding allocation in the HESP?

b. Did the funding allocation in HESP eliminate the diversity between the system and sector for public goods purposes?

c. Did a significant effect of the public goods transformation influence the target higher education system?

d. Can we set better strategies by way of specific funding allocations towards public goods in higher education for sustainable development?

This paper includes the following stages: First, we review funding allocation theories, the meanings of public goods, and their transformation logic in higher education. We utilize the policy initiative of HESP as an example of seeking public goods. Second, the method section addresses the data collection and statistical processes conducted to verify the logic behind funding allocation. Third, we examine the effect of funding allocations in HESP using different types of higher education institutes and their structural relationships. Fourth, the discussion section focuses on what challenges are confronted in the higher education system when public goods policy is intended to be implemented. Finally, conclusions are drawn, and suggestions are provided for higher education.

2. Literature Review

This section begins by addressing the funding allocation theories. Next, we discuss the meaning of public goods in sustainable higher education. Then, we provide examples of transferring public goods into a neoliberal higher education setting. Finally, we target the funding allocations from neoliberal schemes to public goods and provide some hypotheses for testing in this case study.

2.1. Theory of Funding Allocations

Funding allocations refer to a process in which a system or a government transfers resources among the various intended target groups. There are various funding allocation theories, and the evidence-based model is one that ensures that funding is invested in the target groups with the greatest need [

16]. Management theory is primarily devoted to planning and budgeting for the use of resources [

17]. The resource allocation process is assumed to be an exemplary process for theory-based instruction to guide the choices of management. The planning theory recognizes management as providing aggregate goals integrated into sub-goals for each part of the organization [

18,

19]. Moreover, critical planning theory is associated with power, equity, knowledge construction, and related issues to test professional concepts in the real world [

20,

21,

22]. Therefore, strategic planning must be systematic; it involves choosing specific priorities and making decisions concerning short-term and long-term goals [

23,

24].

In this sense, applying planning theory to specific funding allocations in higher education settings requires empirical investigations of actual planning in many different settings. As a national strategy plan, HESP has its policy purposes and expected effects for sustainable development. As Hoch’s argument, the theory was only helpful for a limited number of specialized scenarios, not on a day-to-day basis [

25]. Previous funding theories provide rough guidelines, whereas HESP with specific purposes is different from general funding allocations. In this study, we intend to confirm that the academic efficiency could be achieved through the specific funding process.

2.2. Meanings of Public Goods in Sustainable Higher Education

The notion of public good comes from economics, and it is rooted in neoclassical economic theories. Public goods are often assumed to be non-competitive and non-excludable [

26]. Previous studies have argued it is impossible to exclude any individual from benefiting from good [

26,

27]. The concept of public good is never static, as it is continually restated by various discourse communities [

28,

29]. For example, Daviet claimed “a common good is a collective decision that involves the state, the market, and civil society” [

30] (p. 8); Nixon identified the public good as “a good that, being more than the aggregate of individual interests, denotes a common commitment to social justice and equality” [

31] (p. 1). These notions might drive the occurrence of public goods in society.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the economic conception of public goods extends to social and other contexts. For example, Daviet argued that the economic conception of public goods provides a fundamental basis for understanding the social, cultural, and ethical dimensions of education [

30]. Locatelli suggested that the framework of education as a public good and a common good is a sort of continuum in line with the aim of developing democratic and political institutions that enable citizens to have a voice in the decision-making process [

32]. Eryaman and Schneider suggested that “a public good commitment necessitates a mutual understanding concerning the common goal of public education, an obligation to social justice and equality, and a focus on that provides learners with the skills needed for a meaningful role as a citizen” [

11] (p. 8). Moreover, UNESCO argued that education might confront the weakening of public goods under the alliance of scientism and neo-liberalism in the report “Rethinking Education” [

5] (p. 78). Therefore, public goods should be considered in educational practices.

Regarding higher education systems, public goods imply various meanings in different settings. As Marginson’s suggests [

33,

34,

35], we may assume that higher education is intrinsically neither a private, public, or common good. In addition, “it is potentially rivalrous or non-rivalrous and potentially excludable or non-excludable, which means that, being nested into wider social and cultural settings, higher education as a good is policy sensitive and consequently varies by time and place” [

36] (p. 1051). Higher education might exist in a diverse context. Hence, it is reasonable to argue that it belongs to the category of quasi-public goods in China [

37].

Previous studies have focused on conceptual discussions in public good contexts, such as Hazelkorn and Gibson’s public goods and public policy [

6] and Szadkowsk’s conceptual approach [

38]. Theoretical discussions provide a broader basis to explore this topic. In the substantive dimension, this study assumes that public good initiatives in higher education settings can provide learners with the skills to contribute to the well-being of society; for example, high-quality education for young generations, innovative research, and novel technologies to achieve a better life. Such goods could promote social, economic, and environmental sustainability. In this sense, we may raise a question: Can we focus on a transformation of public goods in higher education through fund allocation of HESP to achieve academic efficiency? Since the academic efficiency is one of important steps toward sustainable higher education. Therefore, the expected effects need to be confirmed.

2.3. Transferring Public Goods into Neoliberal Higher Education

Previous studies have indicated that the present work on neoliberal higher education originated from a critical political economy approach [

39,

40]. Various researchers have pointed out that academic communities are experiencing the phenomenon, often referred to as ‘academic capitalism’ [

41,

42,

43], ‘enterprise university’ [

44], or modeled by a new set of parameters, for example, academic performance, accountability, rankings, competitive funding schemes, and so on. The ongoing neoliberal transformation of higher education has influenced universities and everyday academic life [

10]. These phenomena in higher education are deeply embedded in a market-driven managerial logic. In contrast, some researchers have emphasized the public contractual funding of universities as the main lever of market-oriented reforms [

45,

46,

47].

Market-oriented restructuring emerged in public research universities in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States following the decline of block grants and funding. A perspective that the government needs to decide what outcomes of public goods are appropriate for society has recently emerged. Contemporary higher education desires conformable models in these neoliberal times. The idea that universities have a mission to serve society has long been integral to the public’s imagination regarding higher education [

48]. For example, public engagement policies in the UK are older than the most of those governments. Government-initiated policies have emerged, for example, most shaping the higher education landscape in terms of outcomes, management, and governance of institutes in Ireland and formulating a National Research Agenda involving a coalition of regular universities, universities of applied sciences, university medical centers, national research organizations, and industries in the Netherlands. Moreover, the EU agenda for higher education and the new global Education 2030 are committed to promoting equitable, affordable, and increased access to good-quality higher education [

4,

5].

Over the last 20 years, public or common goods have also triggered various discussions concerning higher education in China [

37]. Moreover, Huang and Horiuchi addressed the public goods of internationalizing higher education in Japan [

49]. Despite the acceptance of the concept of public goods, changes and reforms to the system have been dominated by demands from business and industry. In the international context, related studies provide various examples of public good initiatives in higher education. Public goods and their transformation have become crucial indicators to evaluate what higher education has achieved in terms of toward sustainable development.

2.4. Examples of Funding Allocations from Neoliberal Schemes to Public Goods

Two decades ago, the funding allocations in higher education in Taiwan were based on a competitive mechanism. The Ministry of Education in Taiwan has implemented two significant initiatives to enhance the quality of higher education, namely, the Aim for the Top University Plan (ATU) [

50,

51] and the Program for Encouraging Teaching Excellence for universities and technological universities [

14]. One focuses on lifting research performance; the other focuses on achieving better teaching quality. Competitive funding was attached to each of these projects, and funds were allocated under the philosophy of the “pursuit of excellence.” As we observed, reforms in higher education have been overwhelmingly shaped by neoliberal perspectives. Moreover, higher education funding is a zero-sum event at this stage. As researchers have argued, ATU creates a vicious cycle in which non-ATU institutes and their students become increasingly marginalized, especially in the case of private universities [

51]. The specific funds given to selected higher education institutes are based on competitive schemes. Typically, these kinds of funding allocations are ruled by a neoliberal scheme.

In contrast, the HESP (2018-2022) highlighted egalitarianism as a key principle, and it aimed to secure students’ equal rights to education by promoting diversity in the higher education system [

50]. HESP focuses on “higher education sprout” in terms of that higher education for survival in the future should consider how to deep ploughing. Higher education expected to engage in long-term cultivation in teaching, academic development, internationalization, and active implementing social responsibilities in the funding scheme. In 2018, a total of 157 higher education institutes were funded by the HESP. The government allocated TWD 17.37 billion for the first year of the HESP; 65% (TWD11.37 billion) was allocated to the first part of the project, which focused on the quality of teaching and universities’ social responsibility. In addition, 35% (TWD 6 billion) was allocated to the second part of the project, which aimed to enhance the global competitiveness of universities in terms of pursuing high-quality research [

15]. This is a project with a five-year funding scheme supported by government. This also revealed that the funding mechanism has transformed itself into a non-competition orientation.

Analyzing the transformation of public goods, we found the first part of the HESP comprises the following four components: (a) promoting teaching innovation and learning effectiveness; (b) enhancing the publicness of higher education, including financial openness and promoting social mobility; (c) upholding a university’s social responsibility; and (d) developing unique characteristics of universities. The second part of HESP focuses on pursuing leading international status for selected universities and research centers. The selected universities for global Taiwan include the National Taiwan University (NTU), the National Tsing Hua University (NTHU), the National Chiao Tung University (NCTU), and the National Chen Kung University (NCKU). TWD 5.3 billion was allocated for the second part of HESP, including TWD 4.0 billion for leading universities and TWD 1.3 billion for research centers [

14,

15]. In addition, the Ministry of Education provided TWD 2.57 billion for higher education institutes to implement local projects and support disadvantaged students. The total funding from the Ministry of Education is TWD 16.67 billion. The Ministry of Science and Technology has provided another TWD 0.7 billion to enhance the HESP. Based on the funding mechanism, implementing HESP will demonstrate the effect of funding allocations and sustainable academic efficiency in the process of public good transformation. The details of the funding scheme in HESP at this stage are displayed in

Table 1.

2.5. Research Hypotheses

Based on the notions in previous research, we found that HESP intends to implement public goods policy in the higher education system using specific funding reallocations. The policy intends to achieve students’ equal learning rights and promote diversity in the higher education setting. To explore the effects of funding allocations in HESP, we addressed the following null hypotheses for testing:

3. Methodology

In this section, we address the research framework, logic of variables selection, sampling, data collection, statistical analysis, and verification of measure constructs. To explore the effect of HESP (2018-2022), this study employs a mixed method to examine funding allocation for public goods transformation.

3.1. Research Framework

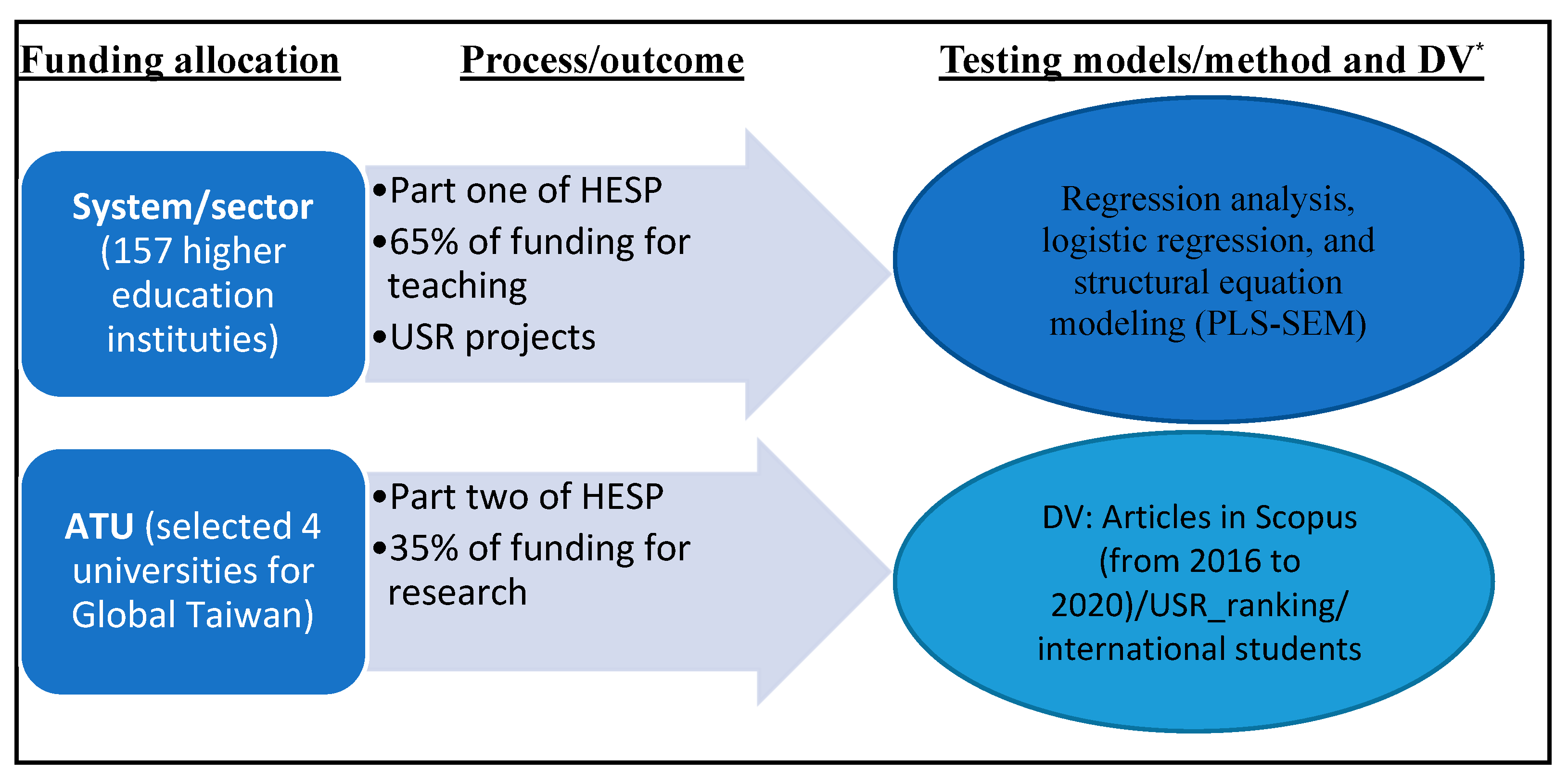

The research framework is presented in

Figure 1. This framework displays how the funding is allocated for different institutes and its proportions for specific purposes. We consider the “System”, which refers to the two different tracks of institutes in terms of university and technological university systems in the target higher education; “Sector” refers to the 157 total public and private institutes. The models are considered testing the funding effect of HESP and its influential factors with different approaches.

3.2. Design of Testing Model

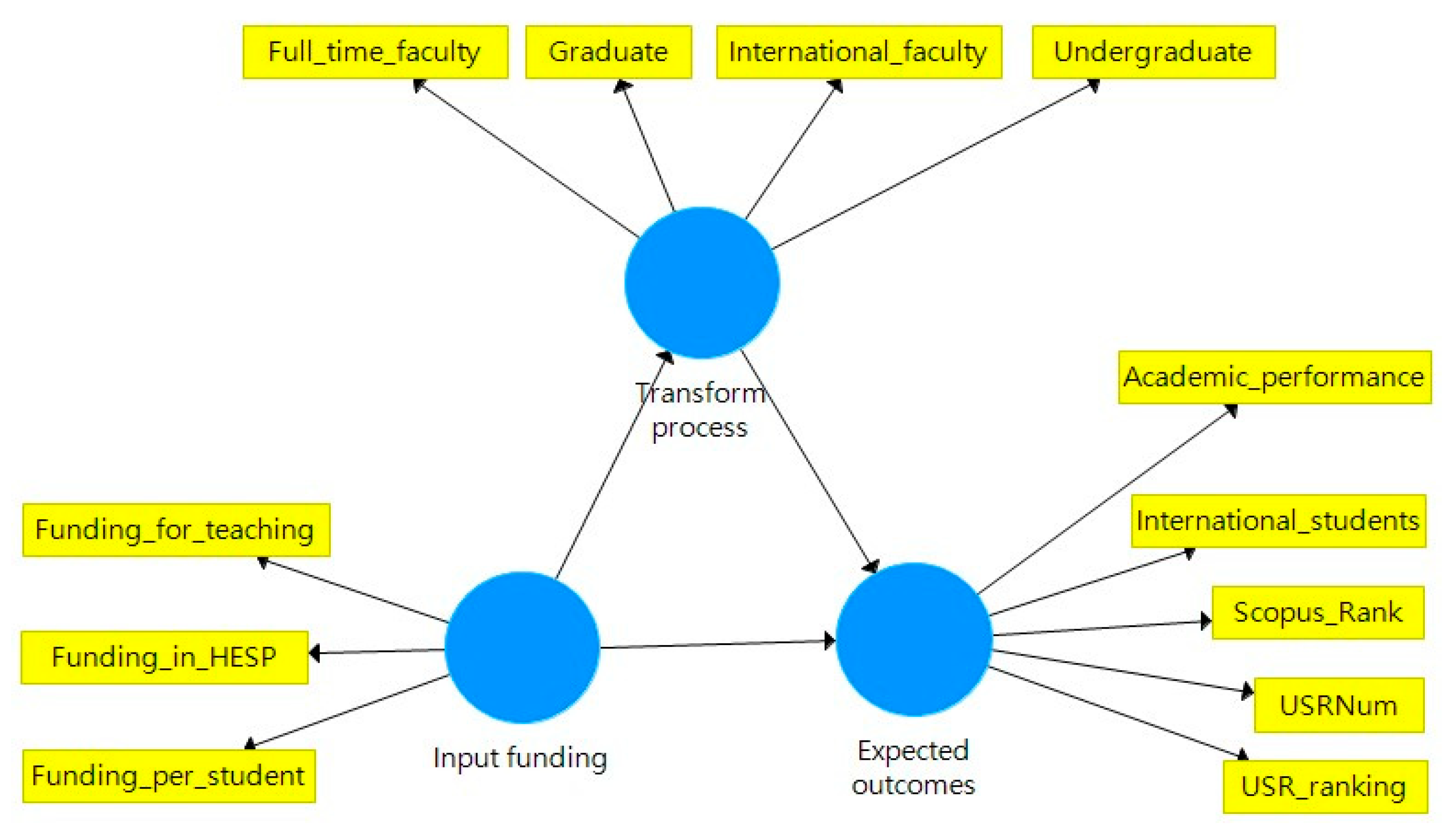

This study designed an input, transformation, and outcome (ITO) model to explore the effect of funding on the quality of teaching, research, and public goods transformation in higher education. Different allocation of funding in HESP is considered as an input dimension. Students and faculty are considered as the major players in the transformation process. Since the teaching effect is not easy examined directly, we considered the expected outcomes are academic efficiency in terms academic performance, internationalization, and participation of university social responsibility (USR). We assume that the simple model is the effect of input variables on expected outcomes, while the mediation effect might exert significant impact. If this is the case that the mediation effect is significant, the impact of transformation process might have larger contribution in this model. Based on the research design, the major variables in the model are selected as follows:

3.2.1. Input Funding (I) Variables

Input funding refers to the funding in HESP for teaching, research, and public good purposes. The variables in the input funding include funding for HESP, funding per student, and funding for teaching.

“Funding_in_HESP” refers to the funds for 157 institutes in the target country. The total amount is TWD 15.34 billion (excluding the specific funding for selected research centers and the funding supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology).

“Funding_per_student” refers to the number of funds for students, which is the fund in each institute divided by the number of undergraduate students.

“Funding_for_teaching” refers to the fund being for teaching purposes only. The calculation considered the number of funds for teaching divided by the number of undergraduate students in each institute.

3.2.2. Transform Process (T) Varaiables

The transformation process refers to human resources and the mechanisms of transformation. The related variables in the transformation process include full-time faculty, international faculty, graduate students, and undergraduate students.

“Full_time_faculty” refers to the full-time faculty that the institute hired.

“International_faculty” refers to the full-time international faculty that the institute hired.

“Graduate” refers to the number of graduate students enrolled in the institution.

“Undergraduate” refers to the number of undergraduate students enrolled in the institute.

3.2.3. Expected Outcomes (O) Variables

This study defines the expected outcomes variables as academic performance, Scopus-Rank, number of USR projects, USR_ranking, and international students in each institute.

“Academic-performance” refers to the total number of journal articles for each institute in the Scopus database from 2018 to 2022. These articles are assumed to relate to research that promotes social well-being or solves global issues. This indicates how institutes face global competition and global issues.

“Scopus_Rank” refers to the number of articles classified into four groups (Q1 to Q4) for the selected universities.

“USRNum” refers to the number of USR projects.

“USR_ranking” refers to the projects implementing social responsibility to fulfill local needs. This variable has been transferred, on a ranking basis, to compare the institute’s engagement. The USR_ranking was weighted by USR projects and funding.

“International_students” refers to the number of international students enrolled in the institute, representing the global competition.

Figure 2 demonstrates the latent variables and their measurement indicators in this study. We follow the proposed structure of the input, transform, and output models.

3.3. Sampling and Data Collection

There are two most common methods of sampling are probability sampling and non-probability sampling. This study focuses on non-probability sampling techniques to collect institutional data. In this study, we conducted purposive sampling as an effective method for research in conditions where there is a confined target. For example, a specific period and funding allocation. The data of institutes were collected from the Ministry of Education in Taiwan and the Scopus database (2018-2022) based on the targeted higher education institutes.

This study considered the students, faculty, and funding data of the 157 higher education institutes in Taiwan. The number of undergraduate and graduate students, international students, and faculty members was collected from the databank of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan. Among these institutes, 50 institutes (31.85%) belonged to the public sector, and 107 (68.15%) belonged to the private sector. The university system consists of 71 institutes (45.22%), while 86 institutes (54.78%) are classified under the technological system. The “full-time faculty” ranges from 9 to 2,045, and the range of “undergraduate” is from 63 to 23,526 in 2022. The funding and USR data are based on a document published by the Ministry of Education in 2018 [

15]. The institutional “academic_performance” data are based on the Scopus databank, we collected the data from 2018 to 2022. Most of the data belong to secondary data. We integrated and transformed the data to fit the requirements of quantitative approaches. In PLS-SEM model, 116 samples (73.89%) were selected to fit that there is no outlier of “Academic_ performance”. Therefore, we exclude four universities for global Taiwan and the institutes that they are no journal paper information available. Finally, there are 78 private institutes (49.68%) fit the selected criteria. Based on Hair et al.’s suggestion, a minimum sample size of 52 for PLS-SEM that has statistical power of 80% in the study [

52]. The samples in this study are fit the minimum requirement.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

In this study, SPSS (the statistical package for social science), Minitab, and partial least square structure equation modeling (PLS-SEM) were used to analyze the data-transforming-related evidence to support our arguments. PLS-SEM was conducted to consider the holistic structure of our testing model, while the inter-variable influences was determined by regression and logistic regression models. The procedures for statistical analysis are as follows:

First, the influential factors in the transformation process are checked. Stepwise regression models with specific variables are used to test the effect of academic performance in the institutes [

53]. This study compared two different models to check the logic of funding with regression analyses. One includes all the possible institutes to interpret the funding on the academic efficiency in the model. The other excludes the selected top four universities to determine which variables critically influence funding allocation without considering academic excellence. The dependent variables are “Funding_in_HESP” (unit: TWD 10000) and “Funding_per_student.” The related independent variables are selected by the stepwise method to build fitted regression models.

Second, logistic regression is conducted using Minitab to determine the effects of funding allocation in HESP on the sector and different higher education tracks. The sector and track of universities are categorically coded variables and dependent variables in the logistic models. The logistic regression estimates the probability of an event occurring, such as voting or not voting, based on a given dataset of independent variables. Since the outcome is a probability, the dependent variable is likely between 0 and 1. In the logistic regression, a logit transformation is applied to the odds—that is, the probability of success divided by the probability of failure. The odds ratio (OR) was calculated to reflect the effect of funding allocation in HESP on the sector and system of the current higher education institutes. The OR was calculated according to the following formula with conditions A and B [

54]:

We also considered the stepwise method with more complicated models in the logistical regression. In the significance tests, the critical value was set to α = .05.

Third, PLS-SEM was used to verify the effect of funding allocation in the HESP. We selected funding for the institute, funding per student, and funding for teaching as formats of funding allocation in HESP. Full-time faculties, international faculties, undergraduate students, and graduate students are the human resource variables that represent the transformation process. Academic performance, Scopus_Rank, USRNum, USR_ranking, and international students are the expected outcome variables. Typically, PLS-SEM was employed to model the relationship between the measured and latent variables or between multiple latent variables. Since multiple regression is restricted to examining a single relationship at a time, PLS-SEM can estimate a series of interrelated and dependent relationships simultaneously. This technique enables researchers to quickly set up and reliably test hypothetical relationships among theoretical constructs and those between the constructs and their observed indicators. PLS-SEM is more effective than multiple regressions in parsimonious model testing. It is employed to find the best-fit model [

55]. Moreover, PLS-SEM is more powerful than covariate-based structure equation modeling (CB-SEM), and it can be applied on non-normal data and a relatively small sample size [

56,

57]. PLS-SEM is also recommended over CB-SEM when the model is complex, and it aims to test the theoretical framework [

58,

59]. Both types of SEM also have potential biases. However, PLS-SEM tends to wield greater power to minimize the biases [

59,

60].

3.5. Verification of ITO Measure Construct

This study considered the overall model fit in PLS-SEM using the following goodness-of-fit indices: quality criteria, constructs, effects, r

2, discriminant validity, and residuals [

56,

58,

61,

62]. Since differences between sectors might exist, we also verified the effect in the target higher education with PLS-SEM. Based on previous studies’ suggestions, we verified the measure construct with Cronbach alpha (> 0.7), average extracted variance (AVE > 0.5), composite reliability (CR > 0.7), HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio) (< 0.85 or < 0.9), critical path, and its coefficient in the PLS-SEM model [

52,

63,

64]. Cronbach alpha, and CR was considered to determine internal consistency. AVE was used to analyze convergent validity. HTMT ratio is an estimation of the correlation between the construct, it is a criterion to assess discriminant validity [

64]. Kline suggests a threshold of 0.85 or less in HEMT [

65], while Teo et al. recommended a liberal threshold of 0.90 or less [

66].

Finally, following Shrout and Bolger’s suggestion [

67], the bootstrap method was used to estimate the mediation effect in this study. We selected resampling 2000 for bootstrapping to demonstrate that the proposed model is robust. When Z > 1.96 (Z = point estimate/standardized error), this implies that there is a mediation effect among the latent variables [

68,

69]. When the mediation effect exists, we confirm the effect in the transformation process.

4. Results

4.1. Influential Factors in HESP Allocations

This study considered a regression model with 157 institutes to interpret the logic of funding allocations in the HESP by assessing the funding scheme and funding for each undergraduate student within these institutes. The proposed impact factors include undergraduate students, full-time faculties, international students, international faculties, and the total articles on Scopus. The details of the regression models are listed in

Table 2.

The regression model reveals that the funding of the HESP for each institute is based on the number of articles in Scopus due to the good relationships between “Funding_in_HESP” and “Academic_performnace”. The R is 0.955 in terms of the articles in Scopus, which explains 91.2% of the funding among these institutes. This finding reveals that the research focus may be large in HESP. Second, when considering the funding for each undergraduate student (Funding_per_student), this study found that “Academic_performance” and “Full_time_faculty” were influential factors in interpreting the Funding_per_student in each institution (R = 0.773, R2 = 0.597). If the number of undergraduate students reflects the scale of the institute, the result reveals that the funding allocations in HESP need to consider the scale of the institute properly. In our proposed regression models, the t and p values reveal that the models are significant. Since the VIF is slim, there are no multi-collinearity problems when the variables fit in the models.

Hypothesis 1: There is no influential factor of the institutes effected on funding allocation; (rejected)

The regression model demonstrates that “Academic_performance” and “Full_time_faculty” were influential factors in the fund allocation.

4.2. The Reasonable Appropriation in HESP

The result reveals that the average funding for each higher education institute is TWD 9770.52 (unit: TWD 10000) in the initiative stage. Regarding the sector, this study found that the average funding for public universities shared TWD 20297.72, while funding for private universities and colleges only shared TWD 4851.27 (

t = 4.686,

p = 0.000). Regarding the system, the average funding for universities shows the sharing of a more considerable amount than that of technological universities and colleges (TWD 15055.94 vs. TWD 5406.98) (

t = 3.011,

p = 0.003).

Table 3 shows that Funding_in_HESP, Funding_per_student, and Funding_for_teaching significantly differ between sectors and systems in the HESP. The findings reveal that only diversity was shown in private technology groups to receive less funding from HESP. Since the oversupply issue in higher education has confronted the higher education system, private technology institutions will threaten the declining birthrate in Taiwan. While the findings reveal a small gap between policy intention for funding allocation in HESP and its practice, it is still acceptable, considering the equal opportunities in most institutes.

To balance the system, the logistic regression revealed that both university and technological university systems can be explained by “Funding_in_HESP”, “Undergraduate”, “Full_time_faulty”, and “International_students” (R2 = 0.45, AIC = 124.91). This implies that the four selected variables can explain the effect of the system with 45% of the variance in the model. The results processed by the stepwise method in the logistical regression model are shown as follows:

Y’ = -0.815 - 0.000176 x Funding_in_HESP - 0.000964 x Undergraduate + 0.02225 x Full_time_faculty + 0.00792 x International_students

Y’ refers to the system; 1 is the university system; and 2 is the technology system. The findings suggest that the university system is favored by HESP. While a significant odds ratio over 4 implies a strong influence, in this case, the odds ratios are slim (

Table 4).

An analysis of the effects of the sector highlights that both the public and private sectors can be explained by the amount of funding and undergraduate students in the logistical regression model (R2 = 0.3139, AIC = 152.34):

Y’ = 0.000195 x Funding_in_HESP - 0.000329 x Undergraduate;

The results reveal that the model only explained 31.39% of the variance with funding and undergraduate students. The ratio of “Funding_in_HESP” for the public sector is 1.0002 for the private sector, and the odds ratio of “undergraduate” for the public sector is 0.9997 for the private sector. The findings reveal that the public and private sector gap is minimal.

Table 4.

Odds ratios for systems with selected predictors.

Table 4.

Odds ratios for systems with selected predictors.

| Selected predictors |

Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

| Funding_in_HESP (TWD 10000) |

0.9998 |

(0.9997, 0.9999) |

| Undergraduate |

0.9990 |

(0.9986, 0.9994) |

| Full_time_faulty |

1.0225 |

(1.0102, 1.0350) |

| International_students |

1.0079 |

(1.0042, 1.0117) |

Hypothesis 2: There is no different of funding allocation in system and sector; (accepted)

4.3. Expected USR Implementation

A total of 220 USR projects were conducted at 116 institutes. Therefore, 549 proposals were submitted for financial support, and only 40% of them were accepted in HESP. USR refers to the university’s social responsibility. This reflects that the institutes are engaged in social development to fulfill local needs. The results reveal that the university system conducted 102 USR projects, while the other 118 projects were conducted in the technological university system. The results also demonstrate that 46.36% of the USR projects belong to the public sector, while the other 53.64% belong to the private sector. The change has shown more significant differences than before. USR could be a significant indicator to reflect public goods oriented or toward sustainable development.

4.4. Testing ITO Model with PLS-SEM

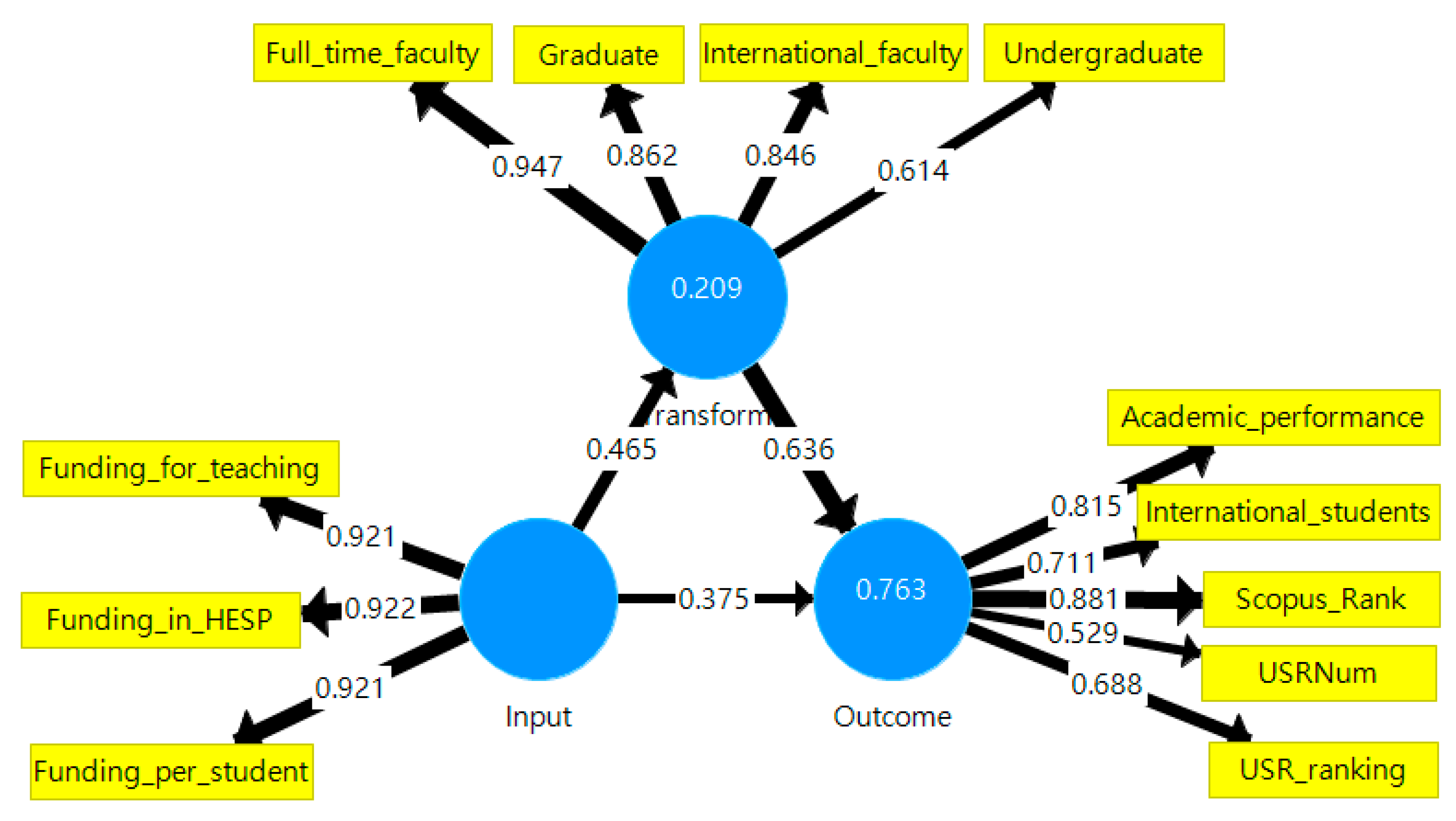

This study employed PLS-SEM to test the proposed model using the data from 116 institutes. The results reveal that the adjusted R

2 in the transformation process and expected outcomes are 0.209 and 0.763, respectively.

Table 5 displays the construct reliability and validity, the Cronbach’s alpha in input funding, the transformation processes, and expected outcomes as 0.923, 0.852, and 0.794, respectively. The composite reliability in input funding, transformation processes, and expected outcomes is 0.944, 0.894, and 0.851, respectively. The AVE in input funding, transformation processes, and expected outcomes is 0.849, 0.683, and 0.540, respectively. The results reveal that the testing indices in ITO are sufficient in required internal consistency and convergent validity.

Table 6 outlines the HTMT of the model to demonstrate the reflect measure construct. Following the HTMT ratios, we found values ranging from 0.442 to 0.834. The measure construct is fit the criteria that HTMT ratios are less than 0.850. The measure construct with current format works well.

The results reveal that the estimated standardized coefficients are 0.375, 0.465, and 0.636 in H3, H4, and H5, respectively. The indirect effect is 0.324 (see

Table 7). Based on the significant criteria (p < 0.05), the hull hypothesis tests are listed as follows:

Hypothesis 3: There is no effect of input funding on expected outcomes (rejected);

Hypothesis 4: There is no effect of input funding on the transformation process (rejected);

Hypothesis 5: There is no effect of the transformation process on expected outcomes (rejected);

Hypothesis 6: The input funding will not, through the transformation process, impact expected outcomes (rejected).

Table 7.

Estimated standardized coefficients and p-values in hypothesis tests.

Table 7.

Estimated standardized coefficients and p-values in hypothesis tests.

| Hypothesis tests |

Coeff. |

p |

| H3: Input funding → Expected outcomes |

0.375 |

* |

| H4: Input funding → Transform process |

0.465 |

* |

| H5: Transform process → Expected outcomes |

0.636 |

* |

| H6: Input funding → Transform process → Expected outcomes |

0.324 |

* |

Since the null hypotheses are rejected, the results suggest that the input funding in HESP and the transformation process have a significant impact on the expected outcomes. The IPO model has demonstrated that HESP funding can transform to its expected outcomes.

Figure 3 displays the estimated structural relationships with PLS-SEM to support this argument.

4.5. Testing Mediation Effect

We used the bootstrap method to estimate the model’s mediation effect with 2,000 samples in PLS-SEM. The results showed that the effect of mediation (Input funding → Transform process → Expected outcomes) was 0.324, and it was significant at the 0.05 level (

p = 0.000). The details of the indirect effect (mediation effect) and total effect,

p-values, and 95% confidence interval of the bias-correction accelerated percentile (BCa) are displayed in

Table 8. Based on the

p-values, the estimated coefficients for indirect and total effects are significant in the bootstrapping process with BCa.

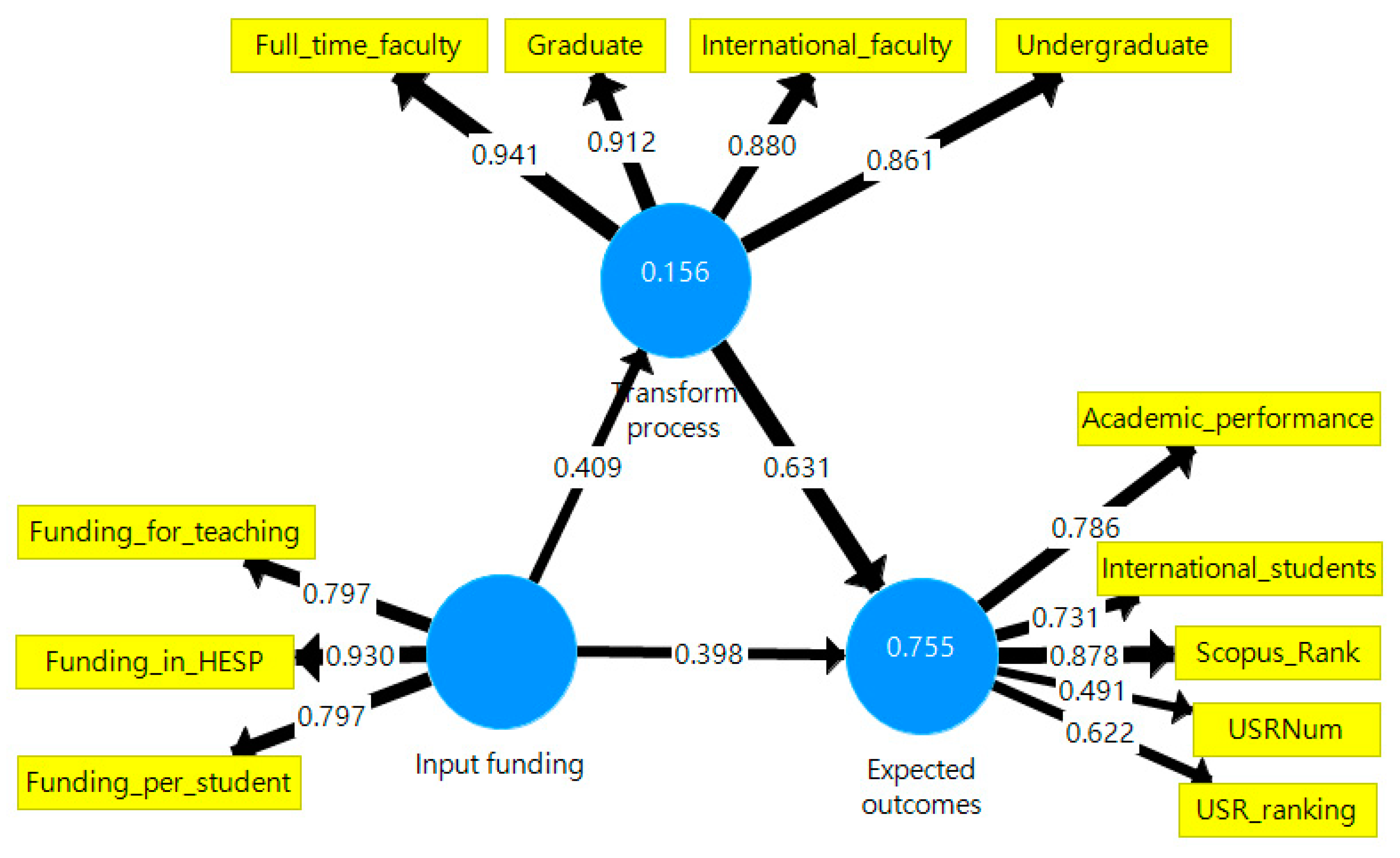

4.6. Verifying the Effect of Private Sector by PLS-SEM

Previous studies have argued that public goods in the private sector is limited. Considering the effect of funding allocation on 78 private institutes, we employed PLS-SEM to verify the transformation process. The results of PLS-SEM indicated that Cronbach alpha results in input funding, the transformation process, and the expected outcome are 0.864, 0.922, and 0.767, respectively. The model demonstrates that the AVE results are 0.712, 0.808, and 0.510 in input funding, the transformation process, and the expected outcome, respectively. In this model, the composite reliabilities are 0.881, 0.944, and 0.834 in input funding, the transformation process, and the expected outcome, respectively.

Table 9 shows the discriminant validity (HTMT), implying the values are less than 0.850. The finding suggests that the testing model for the private sector transforming public goods is a good fit.

Figure 4 shows the weighted regression coefficients and relative path diagrams in the model. The adjusted R-square values of the transformation process and expected outcome are 0.156 and 0.775 in the private sector, respectively. The findings reveal that the indirect effect is 0.258, and the total effect is 0.656. The findings demonstrate that specific funding through the transformation process can also achieve the expected outcomes in the private sector. The findings suggest that ITO model also fit the private sector.

5. Discussion

In Taiwan, previously enhanced quality and introduced teaching excellence programs are based on the competitive mechanism [

51]. Adverse effects have been reported, for example, the over-emphasis on evaluation and the necessity for accountability in a short period of time [

70]. Moreover, studies from the perspectives of students and teachers indicate that universities receiving teaching excellence program grants failed to meet their expectations [

71,

72]. This is why the HESP was initiated. Can public goods work well in higher education with a series of policy-driven reforms in neoliberal contexts? This is a critical point of public good transformation for sustainable higher education. In the beginning, the HESP considered targeting the quality of higher education institutes, balancing institutional excellence, and improving the quality of teaching for disadvantaged students. Specific funds from HESP are offered to all higher education institutes instead of a competition scheme. In addition, this study found that the expected outcomes are academic performance and international student recruitment, whereas the impact of USR is still limited. In PLS-SEM testing, the findings suggest that the initial funding provided by HESP can impact the expected outcomes through the transformation process. The mediation effect of the transform process is significant in the proposed model. Compared with previous policy initiatives, the most significant change in the HESP is implementing USR. The USR consists of strengthening university–industry collaboration, fostering cooperation among universities and high schools, and nurturing talent required by local economies. In the long term, the influence of USR projects will increase in the higher education system. In this sense, HESP demonstrates that USR could be a crucial factor in a sustainable model.

In this study, we also raised two crucial questions: How wide is the gap in the funding allocations in HESP between the system and sector for public good purposes? What are the influential factors for funding allocations in the HESP? HESP encouraged higher education institutes to promote teaching innovation by enhancing learning effectiveness and teaching quality to reduce inequality. Based on the effect of funding allocations, this study found that some issues are emerging in the HESP. First, the HESP aims to secure students’ equal rights to access good quality and diverse higher education systems. Suppose equal rights to access higher education reflect no significant difference in their funding allocations for institutes. While the funding scheme reveals that the institutional scale needs to properly reflect the funding allocations, there is a gap between universities and private technological universities and colleges. This example may inform related policy initiatives in higher education. Funding for public goods implementation should consider sector balancing in higher education. Fortunately, the results of PLS-SEM confirm that the transformation process works well in both sectors. Second, this study found that the funding of the HESP for each institute is based on the number of articles in Scopus due to their high association with the testing model. The government encourages higher education to propose institutional projects with unique characteristics for their sustainable development. At the same time, our results reveal that there is a similar culture on campuses where encouragement for article production persists. Therefore, balancing between teaching and research must be considered in the next stage of HESP.

In a global context, higher education policies have typically been shown to provide incentives for universities to develop or strengthen their capacity for the academic profession and performance in neoliberal times [

2,

7]. For example, Codd’s and Burton-Jones’s arguments reflect a similar phenomenon in higher education [

73,

74]. Various funding-centered studies have focused on global competition discussions in neoliberal contexts [

10,

39,

41]. In comparison, various studies indicate that the concept of public goods might play a significant role in higher education [

11,

34,

36]. Like the EU agenda for higher education and the new global Education 2030 [

4,

5], Ireland’s National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030 and the Dutch National Research Agenda also provide ambitious targets for public good in higher education. This indicates a possible transition within the neoliberal regime from competition-oriented to public-good-oriented systems.

Can significant policy initiatives transform public goods in neoliberal higher education settings? This study provides an empirical example (an ITO model) to evaluate the core values of public goods and their practices in higher education settings. The findings suggest that when higher education is considered from a public goods perspective, the competitive funding scheme should consider the policy’s intention and the effect of implementation. Even though the policy intention is evident in this case study, change still needs to be faster and more predictable in neoliberal higher education contexts. This study confirmed that the common good is a collective decision that involves the state, the market, and civil society [

30]. Since it is impossible to exclude any individual from benefiting from the good [

26,

27], higher education policies for public good intervention may need adequate resources for long-term support. With appropriate funding for public good purposes, higher education can find ways to respond to the challenges of local and global issues. This study found that current policy intentions and short-term funding support did not match well. This may reflect the fact that the effects are not satisfied for higher education institutes at this stage.

Taking HESP as an example, the ITO model may provide a more holistic perspective to reflect the issues in neoliberal higher education settings, regardless of the public and private sectors. With higher education institutes, the effectiveness of education, research, and innovation can appropriately connect to societies. As stated in previous discussions, the private sector does not usually provide pure public goods; therefore, pure public goods in higher education are a minor phenomenon [

48]. In this study, we demonstrate that the effects of specific funding for public goods are significant regardless of the sectors in higher education. The example of HESP may provide a more profound understanding of funding allocations for public goods in neoliberal times. Even though the private sector received limited public funds in the HESP, funding-driven policy supported all private institutes in this case study.

In general, performance funding is based on an input/output model of services, where services are financed by government agencies in terms of output indicators. As higher education moved into a globally competitive era, questions arose concerning putting public goods schemes to work in a neoliberal context. What will be the effect of public good perspectives on contemporary higher education? After reviewing the relevant literature, this study observed changes. For example, Tian and Liu’s study indicated that public or common goods also triggered discussions concerning higher education in China [

37]. Huang and Horiuchi addressed the public goods of internationalizing higher education in Japan. Despite the acceptance of the concept of public goods, changes and reforms in the Japanese system have been dominated by demands from business and industry [

49]. Moreover, many European countries have implemented some form of performance-based funding in higher education. For example, implementing research performance-based funding (RPBF) systems aims to improve research cultures and facilitate institutional changes that can help increase research performance [

75]. Many EU countries have introduced, are introducing, or are considering introducing such systems, whereas the consideration of the implementation of public goods, tuition, and fees has traditionally been low in Europe, reflecting the view that higher education is a public good [

76]. There are alternative funding schemes to fit various performance purposes in European countries.

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

Higher education is the most diverse system in the world. Within the diversity system, the equity issue has been raised in many countries. For example, Zerquera and Ziskin’s study indicated that performance-based funding requirements interact with the public-serving mission of urban-serving research universities (USRUs) in the USA and can deepen stratification across a differentiated system [

77]. Therefore, the ITO model has its limitation to fit all the diversity systems. This study may confirm that only when the balance between equity and excellence is achieved can a sustainable higher education system be expected.

Moreover, considering disadvantaged groups, various studies have focused on how performance-based funding impacts marginalized students [

78,

79,

80,

81], with findings across these studies essentially pointing to adverse effects on access for underrepresented students. Unfortunately, this study did not find significant evidence to support the fact that HESP positively affects underrepresented students. Therefore, policymakers, institutes, and researchers must work towards synergistic interactions to deepen our understanding and vision for a better society. In the initial transformation stage, it is essential that cooperation lead the program to success in higher education.

For future studies, we suggest that the local researchers follow up on the effect of stage II HESP from 2023 to 2027. This study might be limited in its quantitative approach. There is great information in the context of practices that might be neglected in this study. Therefore, related qualitative approaches are alternative strategies that could be used to access and interpret other kinds of data. For international researchers, the design of the study can extend to similar issues in other higher education settings. Since sustainable development covers social, economic, and environmental issues, the notion of public goods transformation is not limited to higher education settings only. Public goods transformation issues have emerged for different reasons and at different levels of organizations. Similar institutes can also think about the notions and models that will develop in the next society.

7. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the government initiated the HESP and targeted the quality of higher education institutes to balance institutional excellence with caring for disadvantaged students’ learning. Regarding this core issue, policy managers need to engage in continuous discussion with partners to overcome the funding gaps for public good purposes. Our study revealed that public goods can transform higher education by reshaping what universities are expected to do in an uncertain future. This case study may provide a valuable reference when policy design considers theories and practice issues by transforming public goods for sustainable higher education.

Moreover, this study focuses on the following concerns for higher education: First, reshaping institutional strategies for public goods and promoting strong institutional characteristics for substantive development in the future are necessary. Second, it is crucial to continue balancing academic excellence and quality teaching, and commitment to implementing innovative and quality teaching for disadvantaged groups should be the premier institutional strategy for most institutes. Third, higher education institutes should commit to achieving remarkable progress in expanding learning opportunities for all as part of the UN’s SDGs. With appropriate funding, higher education can find ways to respond to the challenges of local and global issues. Finally, we know that sustainable higher education is a long-term goal, and it needs many resources and partners to support it. Therefore, we hope that this case study will provide a helpful example to help further explore similar issues in higher education settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.-F.C.; methodology, D.-F.C. and A. C.; software, D.-F.C. and A. C.; validation, D.-F.C. and A.C.; formal analysis, D.-F.C. and A.C.; investigation, D.-F.C.; resources, D.-F.C. and A.C.; data curation, D.-F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.-F.C. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, D.-F.C. and A.C.; visualization, D.-F.C. and A.C.; supervision, D.-F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan. Grant number MOST 111-2410-H-032-031 (from 1 August 2022 to 31 July 2023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data transformation is contained within the article. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bottrell, D.; Manathunga, C. Shedding light on the cracks in neoliberal universities. In Resisting Neoliberalism in Higher Education; Bottrell, D., Manathunga, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zepke, N. Student Engagement in Neoliberal Times: Theories and Practices for Learning and Teaching in Higher Education; Springer: Singapore, Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DES. National strategy for higher education to 2030. Department of Education and Skills. Available online: http://www.hea.ie/sites/default/files/national_strategy_for_higher_education_2030.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on a renewed EU agenda for higher education (COM/2017/0247 final). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52017DC0247 (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- UNESCO. Rethinking Education: Towards a Global Common Good? UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hazelkorn, E.; Gibson, A. Public goods and public policy: What is public good, and who and what decides? High. Educ. 2019, 78, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olssen, M.; Peters, M.A. Neoliberalism, higher education and the knowledge economy: From the free market to knowledge capitalism. J. Educ. Policy 2005, 20, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frlie, E.; Musselin, C.; Andresani, G. The steering of higher education systems: A public management perspective. High. Educ. 2008, 56, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottrell, D.; Manathunga, C. Shedding light on the cracks in neoliberal universities. In Resisting Neoliberalism in Higher Education; Bottrell, D., Manathunga, C., Eds.; . Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ergül, H.; Cosar, S. (Eds.) Universities in the Neoliberal Era; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eryaman, M.Y.; Schneider, B. Evidence and Public Good in Education Policy, Research and Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE). Submission to the productivity commission inquiry into the National Education Evidence base. Available online: http://www.pc.gov.au/_data/assets/pdf_file/008/199574/sub022-education-evidence.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- AERA. Research and the public good statement. Available online: http://www.aera.net/Education-Research/Research-and-the-Public-Good (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Ministry of Education. Higher Education Sprout Project (final version); Ministry of Education: Taipei, Taiwan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. The review report of higher education sprout project (2018). Available online: https://www.edu.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=9E7AC85F1954DDA8&s=8365C4C9ED53126D (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Ministry of Social Development, New Zealand. Funding allocation model. Available online: https://www.msd.govt.nz/what-we-can-do/providers/building-financial-capability/funding-allocation-model.html (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Bower, J. Resource allocation theory. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management; Augier, M., Teece, D.J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1445–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Allmendinger, P. Planning Theory, 3rd ed.; Palgrave Macmillian: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal, B. Planning in theory and in practice: Perspectives from planning the planning school? Plan. Theory Pract. 2007, 8, 251–275. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Planning Theory and Urban and Regional Dynamics: A Comment on Yiftachel and Huxley. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2001, 24, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, T. Reviving Critical Planning Theory; Routledge: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yiftachel, O., & Huxley, M. Debating dominance and relevance: Notes on the ‘communicative turn’ in planning theory. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00286 (accessed on August 2023).

- Damib, A. Educational planning in theory and practice. In Educational planning and social change: Report on an IIEP seminar; Weiler, H.N., Ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1980; pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sevier, R.A. Strategic Planning in Higher Education: Theory and Practice; CASE Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hoch, C. The planning research agenda: Planning theory for practice. Town Plann. Rev. 2011, 82, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarais-Tremblay, M. On the definition of public goods. Assessing Richard A. Musgrave’s contribution. Documents de travail du Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00951577/document (accessed on 15 May, 2023).

- Musgrave, R.A. Provision for social goods. In Public Economics: An Analysis of Public Production and Consumption and Their Relations to the Private Sectors; Margolis, J., Guitton, H., Eds.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1969; pp. 124–144. [Google Scholar]

- Mansbridge, J. On the contested nature of the public good. In Private Action and the Public Good New; Powell, W., Clemens, E., Eds.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1998; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pusser, B. The role of public spheres. In Governance and the Public Good; Tierney, G., Ed.; State University of New York Press: New York, USA, 2006; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Daviet, B. Revisiting the principle of education as a public good, Education research and foresight series, No. 17. UNESCO. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-theinternational-agenda/rethinking-education/erf-papers/ (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Nixon, J. Higher Education and the Public Good: Imagining the University. Bloomsbury: New York, USA, 2011.

- Locatelli, R. Education as a public and common good: Reframing the governance of education in a changing context. UNESCO Education Research and Foresight Working Papers. No 22. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0026/002616/261614E.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Marginson, S. The public/private divide in higher education: A global revision. High. Educ. 2007, 53, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Higher education and public good. High. Educ. Quart. 2011, 65, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Higher Education and the Common Good; Melbourne University Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjieva, P.; Ilieva-Trichkova, P. From conceptualization to measurement of higher education as a common good: Challenges and possibilities. High. Educ. 2019, 77, 1047–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Liu, N.C. Rethinking higher education in China as a common good. High. Educ. 2019, 77, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szadkowski, K. The common in higher education: A conceptual approach. High. Educ. 2019, 78, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Carasso, H. Everything for Sale? The Marketization of UK Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H.A. Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education; Haymarket Books: Chicago, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell, B.; Kauppinen, I. (Eds.) Academic Cpitalism in the Age of Globalization; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Munch, R. Academic capitalism. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-15 (acessed on 10 May 2023).

- Slaughter, S.; Rhoades, G. Academic Capitalism and the New Economy: Markets, State and Higher Education; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson, S.; Considine, M. The Enterprise University: Power, Governance and Reinvention in Australia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.; Lamont, M. (Eds.) Social Resilience in the Neoliberal Era; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, L.; Slaughter, S. Academic Capitalism: Politics, Policies and the Entrepreneurial University; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Reale, E.; Primeri, E. Reforming universities in Italy. In Reforming Higher Education: Public Policy Design and Implementation; Musselin, C., Teixeira, P., Eds.; . Springer: London, UK, 2014; pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bacevic, J. Beyond the third mission: Toward an actor-based account of universities’ relationship with society. In Universities in the Neoliberal Era; Ergül, H., Cosar, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Clam, Switchland, 2017; pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Horiuchi, K. The public good and accepting inbound international students in Japan. High. Educ. 2019, 79, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Outcomes of ATU (2017). Available online: http://moe.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=7122&ctNode=713&mp=1 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Tang, C.W. Creating a picture of the world class university in Taiwan: A Foucauldian analysis. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2019, 20, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aljandali, A. Multivariate Methods and Forecasting with IBM SPSS Statistics; Springer: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, J. Odds ratio: Formula, calculating & interpreting. Available online: https://statisticsbyjim.com/probability/odds-ratio/ (accessed on 10 June, 2023).

- Cheng, E.W.L. SEM being more effective than multiple regression in parsimonious model testing for management development research. J. Manage. Dev. 2001, 20, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Ting, H.; Cheah, J.H.; Thurasamy, R.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. Sample size for survey research: Review and recommendations. J. Appl. Stru. Equ. Model. 2020, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res.Market. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Gudergan, S.P. Estimation issues with PLS and CB-SEM: Where the bias lies! J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehlin, J.C. Latent variable models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Equation Analysis, 4th ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associate: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Lawrence Erlbaum Associate: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-C.; Chang, D.-F. Exploring international faculty’s perspectives on their campus life by PLS-SEM. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. The New Psychometrics: Science, Psychology, and Measurement; London, UK: Routledge, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, T.S.H.; Srivastava, S.C.; Jiang, L. Trust and electronic government success: An empirical study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2008, 25, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efron, B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1987, 82, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C.P.; Wang, L.-T. Who benefits from the massification of higher education in Taiwan? Chinese Educ. Soc. 2012, 45, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, D.-F.; Yeh, C.-C. Teaching quality after the massification of higher education in Taiwan. Chinese Educ. Soc. 2012, 45, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.-S.; Bai, Y.; Wang, T.-W. Students’ classroom experience in foreign-faculty and local-faculty classes in public and private universities in Taiwan. High. Educ. 2014, 68, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codd, J. Selected article: Educational reform, accountability and the culture of distrust. In Critic and Conscience: Essays on Education in Memory of John Codd and Roy Nash; Openshaw, R., Clark, J., Eds.; NZCER Press: Wellington, New Zealand, 2012; pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Burton-Jones, A. Knowledge Capitalism: Business, Work and Learning in the New Economy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers, K.; Zacharewicz, T. Research Performance Based Funding Systems: A Comparative Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, M. Performance-based funding, higher education in Europe. In The International Encyclopedia of Higher Education Systems and Institutions; Teixeira, P.N., Shin, J.C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Germanny, 2020; pp. 2227–2231. [Google Scholar]

- Zerquera, D.; Ziskin, M. Implications of performance-based funding on equity-based missions in US higher education. High. Educ. 2020, 80, 1153–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Jones, S.; Elliott, K.C.; Owens, L.; Assalone, A.; Gándara, D. Outcomes Based Funding and Race in Higher Education: Can Equity be Bought? Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017.

- Kelchen, R. Do performance-based funding policies affect underrepresented student enrollment? J. High. Educ. 2018, 89, 702–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbricht, M.R.; Fernandez, F.; Ortagus, J.C. An examination of the (un)intended consequences of performance funding in higher education. Educ. Policy 2017, 31, 643–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagood, L.P. The financial benefits and burdens of performance funding in higher education. Educ. Eva. Policy Anal. 2019, 41, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).