1. Introduction

On January 1, 2024, at 16:10 (Japan Standard Time), an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.6 and a maximum seismic intensity of seven occurred in Japan, with its epicenter on the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture. The epicenter depth was shallow at 16 km, and tremors were observed across almost all of Japan. In the Noto region, which was the epicenter of the earthquake, many buildings collapsed because of the violent shaking. The earthquake also triggered a tsunami that damaged at least 160 ha in Suzu City and Noto Town [

1]. A large-scale fire occurred in Kawai-machi, Wajima City, destroying more than 200 buildings, including stores and homes. Owing to the earthquake, electricity and water supplies were cut off, and communication was disrupted. More than 1,000 aftershocks, including earthquakes with a seismic intensity of five or higher, occurred within a week, forcing more than 20,000 residents of the Noto region to evacuate [

2]. This earthquake was one of the largest disasters in Japan in recent years. Even after two weeks from the disaster, the full extent of the damage remains unknown. The search for missing people and support for disaster victims is ongoing.

Immediately after the earthquake, the authors visited Wajima City, the disaster area, and conducted disaster relief activities. We patrolled Wajima City and checked the conditions of the roads and evacuation centers. We also conducted health observations of the evacuees at the evacuation centers. This study discusses the characteristics of the disaster and proposes future issues regarding disaster relief.

2. Materials and Methods

The authors visited disaster-affected areas and examined the damage situation in Wajima City and the status of the evacuation centers. The authors also spoke to the evacuees and experts working on the ground. This report integrates and discusses the results of site visits, information broadcasts by public institutions, and previous research.

Table 1.

Summary of the situation in the affected area for 11 days post the disaster.

Table 1.

Summary of the situation in the affected area for 11 days post the disaster.

| Date |

Event |

| January 1st |

- At 16:10, an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.6 occurred in the Noto region of Ishikawa Prefecture, with a depth of 16 km. The maximum intensity was seven.

- At 17:30, the Noto Peninsula Earthquake Specific Disaster Response Headquarters was established.

- Tsunami warnings or major tsunami warnings were issued for a wide range from Hokkaido to Nagasaki.

- Widespread water outage occurred in Ishikawa Prefecture, with approximately 32,700 households experiencing power outages. A total of 28,655 people evacuated.

- A large-scale fire occurred in Wajima City.

- In response to Ishikawa Prefecture’s request, the Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMAT) were dispatched. |

| January 2nd |

- Tsunami advisories, which had been in effect since the beginning of the disaster, were all lifted at 10:00.

- In Ishikawa Prefecture, 57 fatalities were reported, but the full extent is still unknown.

- Widespread water and power outages continue in Ishikawa Prefecture, with some areas experiencing communication disruptions.

- Restoration work for electricity is underway, but extensive road damage is causing delays.

- Self-Defense Forces initiated water supply activities. |

| January 3rd |

- Since the start of the disaster, 455 aftershocks with a seismic intensity of one or higher have been observed.

- Widespread water outage continues in Ishikawa Prefecture, with over 30,000 households experiencing power outages.

- Communication disruptions remain unresolved, and there are reports of expanded damage in some areas.

- Landslides and collapses of retaining walls have led to road closures in 40 sections of national and expressways. |

| January 4th |

- The number of evacuees exceeds 33,000 in Ishikawa Prefecture.

- Train services have been suspended in the Noto region since the beginning of the disaster.

- Eleven medical facilities in Ishikawa Prefecture face difficulties with electricity, water, and medical gas supply.

- Road-based material transport functions are gradually recovering, and helicopter transportation is used when land transport is not feasible. |

| January 5th |

- Since the onset of the disaster, 1,035 aftershocks with a seismic intensity of one or higher have been observed, including six with a seismic intensity of five or higher.

- Self-Defense Forces continue their life-saving activities.

- Water and power outages continue in most areas, despite partial restoration.

- 39 sections of national and expressways and 65 sections of prefectural roads remain closed in Ishikawa Prefecture. |

| January 6th |

- Ishikawa Prefecture applies the Disaster Victims’ Life Rebuilding Support Act to 19 cities and towns.

- 165 DMAT teams are active within Ishikawa Prefecture. |

| January 7th |

- Noto Airport has a 10-centimeter crack on its runway and remains closed.

- Medical helicopter operations, which had been conducted until the 6th, are suspended on the 7th owing to snow. |

| January 8th |

- Ishikawa Prefecture reports 161 fatalities and 419 injuries.

- 40 municipalities offer 1,200 vacant public housing units. |

| January 9th |

- Severe damage to distribution facilities in Wajima City and Suzu City, Ishikawa Prefecture, is expected to prolong recovery efforts.

- Nine medical facilities in Ishikawa Prefecture are facing issues with electricity, water, and medical gas supply. |

| January 10th |

- Rain and snow accompanied by thunder increase the risk of landslides.

- There are 405 evacuation centers in Ishikawa Prefecture, accommodating over 26,000 evacuees. |

| January 11th |

- Ishikawa Prefecture reports 206 fatalities and 422 injuries. |

| |

- Over 106,000 households continue to experience water outages in 12 cities and towns in Ishikawa Prefecture, with over 13,000 households experiencing power outages. |

3. Results

The Noto area, where the Noto Peninsula earthquake occurred, includes three cities and four towns: Wajima City, Suzu City, Noto Town, Nakanoto Town, Anamizu Town, Shiga Town, and Hakui City (see

Figure 1). On January 5th, four days after the earthquake, we visited Wajima City, which was hit hard. The expressway was closed as it entered the Noto area. We drove along the prefectural roads.

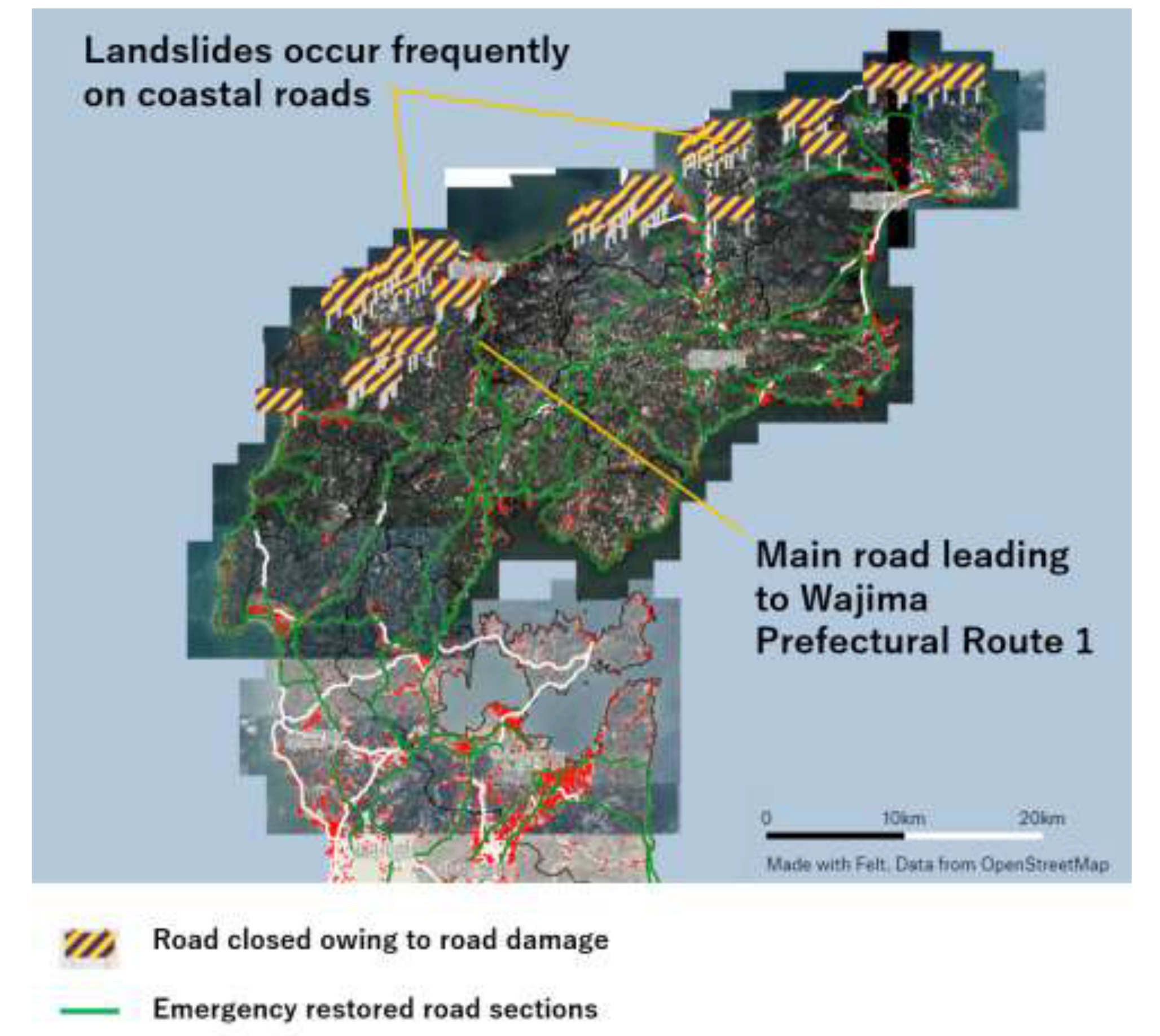

Prefectural roads were undulated and damaged in several places. Many utility poles fell, and buildings were damaged everywhere. Prefectural Route 1, which connects to Noto, experienced landslides in several places, narrowing the width of road for vehicle to travel. Prefectural Route 1 had alternating traffic, making it prone to traffic jams. The east-west coastal road leading to Wajima was closed because of landslides and road collapses (see

Figure 2).

We entered Wajima City and saw the city destroyed. A large building collapsed (see

Figure 3), and a wide area of Kawai-machi was destroyed by fire (see

Figure 4). We stayed there for a week and toured the evacuation center. The evacuation center was without water. They cooked with water brought in by Self-Defense Forces. Because water cannot be flushed down toilets, it was solidified with a coagulant before disposal. The evacuation center was managed by evacuees. The evacuation center leader, who was also an evacuee, took command, and the evacuees worked together to sort and cook the relief supplies. The population of Noto is aging. Many people gathered at the evacuation centers were older adults. At the evacuation center, the amount of exercise among the evacuees decreased. The sanitary environment at the evacuation center could not be considered adequate. Some evacuees got sick. However, there were no regular rounds for medical professionals. Infectious diseases were prevalent in many evacuation centers. Influenza and new coronavirus infections were particularly common. In Japan, when a large-scale disaster occurs, a Disaster Medical Assistance Team (DMAT), a trained medical team with the mobility to act during the acute phase of a disaster, is activated [

3]. DMAT also implements measures for infectious disease control. However, owing to the widespread damage caused by this earthquake, infection control measures were delayed.

Many evacuation centers in Wajima City were isolated because roads were cut off. We visited an isolated evacuation center on foot on January 10

th (see

Figure 5). Village residents gathered at the evacuation center. Most were older adults. The power outage continued, and communications, such as mobile phones and the Internet, were unavailable. Evacuees at the isolated evacuation center did not know exactly what the conditions were in the Noto area. The Self-Defense Forces transported the supplies needed at the isolated evacuation centers. The evacuees said that there was no intervention by medical professionals.

Additionally, a phenomenon in which the sea floor is rising has been observed on the north coast of the Noto Peninsula [

4]. This caused many ports to become unavailable. The port of the isolated area we visited had also become unusable due to upheaval. Perhaps for this reason, Self-Defense Force ships were anchored slightly offshore, and Self-Defense Force members were transporting supplies in rubber boats (see

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of This Disaster

In this earthquake, the recovery of infrastructure and the response to evacuees tended to be slower than in previous earthquakes. During the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, there was a large-scale power outage in the Tohoku Electric Power Company; however, three days after the disaster, power was restored to approximately 80% of the area, except for Miyagi Prefecture [

5]. Conversely, restoration work for the power outage caused by this earthquake is continuing in most areas even 10 days after the disaster, and there is no hope of complete restoration. Temporary toilets were available at evacuation centers three days after the Great East Japan Earthquake. However, even after one week, the installation of temporary toilets at the evacuation center was not completed.

The delay in restoration is due to the geographical characteristics of Ishikawa Prefecture. When the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred in 2011, rapid recovery efforts were carried out by sending support units into the affected area in a comb-like pattern from the north-south road [

6]. Ishikawa Prefecture has a long and narrow topography running north to south. Only a few major roads connect the northern and southern parts of the Noto area. This earthquake not only caused major damage to the main roads but also heavy traffic congestion. In addition, roads from the east and west coasts of Wajima were closed because of widespread landslides. Consequently, disaster relief and construction vehicles for infrastructure restoration were unable to enter the area, causing delays in recovery. In addition, most of Noto is mountainous. This earthquake caused many isolated villages owing to large-scale landslides over wide areas. Not only was it difficult to transport supplies in isolated villages but communication was also cut off because of power outages, which made it difficult to gather information. Furthermore, the incredible phenomenon of seafloor upheaval may also prevent ships form approaching areas where roads have been cut off, potentially delaying recovery.

4.2. The Importance of Autonomous Disaster Relief

The damage caused by this disaster was so extensive that it was difficult for DMAT to understand the entire situation. It can be assumed that the delay in infection control measures and lack of intervention by medical professionals in evacuation centers in remote areas were because DMAT was forced to invest manpower in rescue operations. In this situation, we believe that team activities that support DMAT are important. It is important to have a team that can determine and carry out the necessary activities on site, even without instructions from the DMAT. After receiving general information from DMAT, they go to the site and perform activities based on their own judgment. and share the results with the DMAT. We believe that if such activities are implemented, the burden on DMAT will reduce and detailed support will be provided at evacuation centers. In addition, we think it would be effective for DMAT and local governments to plan with support teams about what to do in case of an emergency before a disaster occurs, so that disaster support can be implemented autonomously without detailed instructions after a disaster occurs.

4.3. The Importance of Autonomy for Evacuation Centers

As mentioned above, in the case of a large-scale disaster over a wide area, there is a possibility that the DMAT’s activities may not have been carried out in detail. In some remote evacuation centers, DMAT teams are rarely able to visit. Under these circumstances, it is important for evacuees to operate the evacuation centers autonomously. We believe that healthy evacuation center management can be achieved by considering the situation of the evacuees and taking the necessary actions. Discussion among residents is an important prerequisite for the autonomous operation of evacuation centers. Therefore, regular communication among residents is important, and the formation of a healthy community is one type of disaster prevention.

5. Conclusions

This earthquake was characterized by transportation being blocked owing to geographical factors, which made infrastructure restoration and support activities difficult. Under such circumstances, it is important for disaster victims to manage their own evacuation centers. In addition, support teams that can operate independently are required in evacuation centers in remote areas where the support of DMAT teams cannot reach sufficient levels. To prepare for a disaster, administrative agencies and support teams need to plan in advance what they will do in the event of a disaster.

Disaster recovery is expected to take a long time. There are concerns that evacuation centers run by local governments could pose health risks if people stay in these centers for long periods. We hope that medical professionals intervene as soon as possible. The next severe disaster could occur in Japan soon. We hope that our experience of this disaster can be used to prepare for future disasters.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.jp) for its pro bono support for the Noto Peninsula Earthquake for English editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).