1. Introduction

Japan has enviable child health indicators, with an overall infant mortality rate of less than 2 per 1,000 live births [

1]. One of the characteristics of Japan is an ageing population and a decreasing proportion of children. The population rate of 0-14 years old is 12% of the whole population. It is the lowest in the world in 2021[

2]. Despite these health indicators, the wealth gap in Japan is increasing. Japan's relative income gap, measured as the gap between the national median income and the bottom 10% of households with children, was 60% in 2014 [

3]. It was the 10th out of 41 OECD countries in 2014. The relative child poverty rate below 50% of the median income was 15.8%. It was 26th out of 42 OECD countries in that year [

4]. Public social spending on families was 2.0% of GDP in 2019, 24th out of 40 OECD countries [

5].

The direct effects of COVID-19 on children in Japan were not severe. One example is the death rate among positive cases was from 0.001 for teenagers to 0.003% for under ten years old children between September 2022 and January 2023 (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare) [

6]. Therefore, the impact was probably less than RSV infection or influenza. In addition, the Kawasaki disease-like cases, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), were rare in Japan [

7]. On the other hand, the indirect effects of the pandemic have been profound for children and their families all over the world [

8,

9,

10]. In Japan, the number of abuse consultation cases increased during the pandemic, increasing by 6% in 2020 and continuing to increase up to 2022 (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare) [

11]. We published a mixed methods study [

12], including stress scales from children experiencing social and financial disadvantage and free-text comments from them between August and November 2020. This cohort of vulnerable children in Japan had high overall stress scores during the early part of the pandemic.

While the health of the Japanese population overall is excellent, there is evidence of significant differences in some indicators between those families living in poverty compared to the mainstream population. While COVID-19 poses the same risk of infection for everyone, the indirect effects may be greater than the direct effects for children, causing more significant difficulties for families from economically vulnerable backgrounds. As in Japan, the COVID-19 pandemic represented a major challenge to the health and wellbeing of families with children globally and families living in poverty and poor social circumstances were particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of the periods of lockdown and school closures instituted by governments to control the spread of the virus [

13,

14].

Our aims were, therefore, to describe the differences in children's and families’ health and well-being between poor families (those living in relative poverty) and those families not in poverty in Japan over the period 2018-2021 which included the COVID-19 pandemic. We used information from national surveys of households with children conducted in 2019 and 2021, where data on household income and mothers’ and children's health and well-being was available. We also gathered data on publicly available child health indicators, with a breakdown according to socioeconomic status where possible.

2. Methods

2.1. Health and well-being of families with children questionnaire

We conducted the national surveys of households with children jointly with the Japan Federation of Democratic Medical Institutions, Japan's second-largest medical group. Out of more than 600 medical institutions in this medical group located in all prefectures, posters and information about the questionnaire were distributed to approximately 250 medical institutions, including paediatrics, 30 dental medical institutions, including paediatric dentistry, and about ten pharmacies near the leading paediatric clinics. After the distribution, we telephoned or mailed each clinic's director and/or paediatrician for cooperation before each year's data collection commenced. We also requested a notice from the medical group centre appealing for cooperation in this research. During the survey period, the degree of participation and collaboration was left to the discretion of each medical institution.

The replies to the questionnaire were from families attending medical services of the medical group’s institutions. We provided incentives to 300 participants with gift vouchers in a lottery both years.

We designed questionnaires on the health and well-being of families with children that anyone could complete if they cared for children at home. These questionnaires on the living conditions of child-rearing households were accessible via a QR code and could be filled out using smartphones. Posters and information about them were widely publicised. The questionnaires were in four parts. The common section was 50 questions to all respondents. It included family composition, living environment, mother's (father's) employment status, household income, mother's educational background and health situation, etc.

Section 1 was more than 30 questions about preschool children over three years old. It included the child's attendance at preschool, health conditions, daily foods, vaccination, etc.

Section 2 was more than 30 questions about school-age children (elementary and junior high school students) between six and fifteen. It included similar questions for preschool children.

Section 3 was more than 30 questions for children between ten and fifteen. Children answered this section. It included children's daily routines, belongings, learning situations, parental relationships, after-school activities, etc.

We designed the questionnaires in which each question group could only be finished by completing all. The first questionnaire period was from June to July 2019. And the second one was from September to October 2021.

As we could not collect responses from families receiving public assistance in 2021, we excluded households receiving public assistance from the 2019 questionnaire in the analysis.

The relative poverty line is half the median income from the large-scale National Questionnaire of Living Conditions conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in 2019 and 2022 [

15,

16]. Households below this line we defined as "families in relative poverty" and households above this line as "non-poverty families". Because the income question asked for a range of income, such as the 3 million yen range, households with incomes including the poverty line were excluded from statistical analysis as “borderline” each year. Respondents could choose "don't want to answer the question" in several questions. So, not all questions were answered completely by all respondents, giving different denominators for each question.

2.2. Other child health indicators:

We gathered data on publicly available child health indicators from national data, wherever possible, with a breakdown according to socioeconomic status.

Infant mortality rates between 2018 and 2021 were extracted from “e-Stat”, which is a portal site for Japanese Government Statistics. Suicide numbers and rates of adolescents between 2018 and 2022 were extracted from the suicide statistics of the National Police Agency.

The data collected for this study were descriptive and complex analysis designed to isolate the causal effect of the pandemic was not feasible. For this reason, we used simple descriptive statistics to analyse the quantitative data, with the Chi-square test and Fisher exact test with StatViewⓇ, to determine the difference between proportions. We used Fisher’s exact test for data analysis involving fewer than ten samples.

3. Results

3.1. Health and well-being of families with children questionnaire:

The total responses were 2,378 in 2019 and 1,432 in 2021; valid responses were 2,241 (94%) in 2019 and 1,368 (96%) in 2021. The relatively poor and non-poor families were 211 (9.4%) and 1,858 (83%) in 2019, and 114 (8.3%) and 1,169 (85%) in 2021. The details of each number and percentage are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Health and Well-being of families with children questionnaire:

We compared data selected for relevance to the indirect effects of COVID-19 on mothers and children between 2019 and 2021 in non-poor families and families in relative poverty.

Table 2 shows that mothers' part-time working increased from 41% to 61% (p 0.074) for families in relative poverty between 2019 and 2021, and regular employment was reduced by two-thirds. Part-time working among mothers in non-poor households did not change significantly. Mothers' spending compared with fathers became more unequal in families in relative poverty, whereas mothers’ and fathers’ spending became more equal in non-poor families.

The self-reported well-being of mothers worsened from 39% to 55% significantly in families in relative poverty (p 0.018) but increased in non-poor families (p 0.027). The percentage of receiving school attendance assistance increased by more than twice in families in relative poverty in 2021 (p<0.001) but did not change significantly among non-poor families. The attitude to public assistance in families in relative poverty changed: the 'not necessary' rate decreased by about three quarters, and that of 'don't want to receive' increased by 1.6 times.

The percentage of completed cases of influenza vaccine in school-age children was lower among children from families in relative poverty compared with those in non-poor families in 2019, and whereas the percentage increased significantly in non-poor families in 2021, the rate of completed influenza vaccine remained low in poor families.

Two markers of deprivation among children showed differences between poor and non-poor families. The percentage of children eating breakfast alone doubled in 2021 compared to 2019 in families in relative poverty but remained the same in non-poor families The proportion of school-aged children from families in relative poverty reporting a quiet space to do their homework decreased by more than 15% but did not change among children in non-poor families.

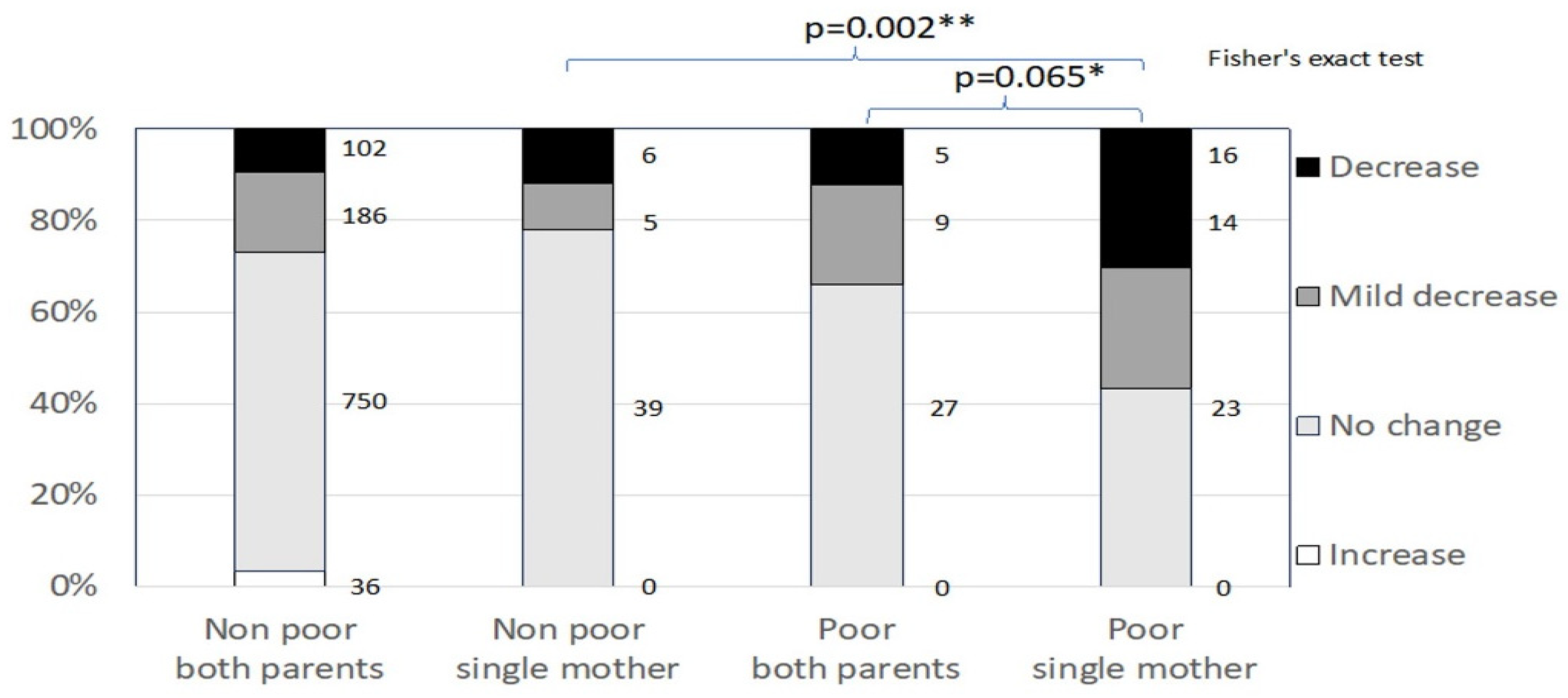

Figure 1 shows income change during the pandemic in 2021 by poor and non-poor families further stratified by whether they were couple or single-mother households. Poor single-mother families experienced a greater decrease in income than the other three groups including non-poor single-mother families.

3.3. Other child health indicators:

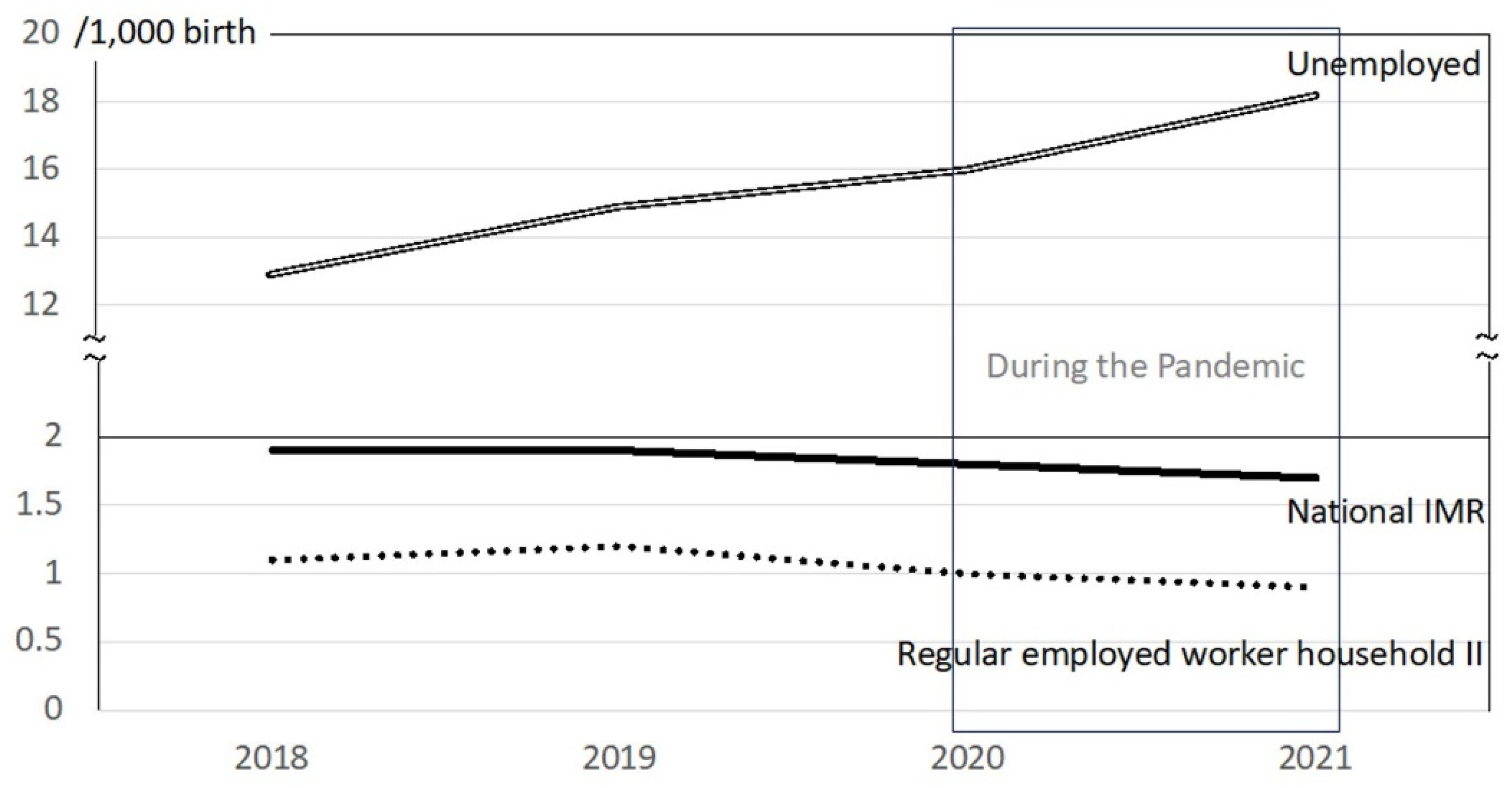

Based on published Japanese government e-stat data, Japan’s infant mortality rate (IMR) steadily decreased from 1.9 /1000 live births to 1.7/1000 from 2018 to 2021 (

Table 3). IMR in households without workers increased from 14.9 to 18.2, while rates in all employment groups followed the decreasing trend in national IMR (

Table 3).

Figure 2 shows annual trends for the recent four years. Japan’s IMR and those of households in various employment categories, showed slightly decreasing trends during the pandemic. IMR among households without workers increased 2.0/1000 from 2018 to 2019 and 3.3/1000 during the years of the pandemic, suggesting a greater impact of the pandemic on infant health in these families compared with more advantaged families in the rest of the population.

The number of suicides in children 10-19 years old increased by more than 100 in 2020 from the previous year. For the first time, the rates are more than two per 100 thousand in 10-14 years old and more than ten in 15-19 years old in 2020 (

Table 4). And the high rates have been continuing in 2021 and 2022.

4. Discussion

Based on questionnaires completed by mothers in 2019 and 2021 and routine data published by e-stat annually between 2018 and 2021, we provide evidence of increasing inequalities between poor and non-poor Japanese mothers and their children across a range of outcomes. The findings indicate that poor mothers’ employment, well-being and share of the household income all decreased over the period 2019 to 2021 compared with little change for non-poor mothers. Household finances decreased significantly, particularly among poor, single mother households, and reliance on school attendance subsidies increased among poor, but not non-poor, households. On the other hand, even though the financial situation of poor families worsened, there was a reluctance to receiving public assistance. Indicators of children’s deprivation (eating breakfast alone and no quiet space to do homework) increased in poor families but did not change in non-poor families. Between 2018 and 2021, infant deaths in Japan fell from 1.9/1000 to 1.7/1000 live births but increased sharply in the poorest households with no adult in work from 12.9/1000 to 18.9/1000 in the same period.

Suicide rates increased from 5.3/100,000 in 2018 to 7.4/100,000 in 2022 among children and youth aged 10-19 years in Japan. The increasing trend over the period of the pandemic was noted in both boys and girls and suicide was the leading cause of death in the 10-19 years age-group. Although the available dataset does not include information on social circumstances, it is reasonable to assume rates will be highest among socially vulnerable children and youth. Goto and colleagues examining both the timing of changes in suicide rates and possible explanations for changes they observed in children aged 10-19 years between 2020-2021, identified several factors associated with the increase in suicides including family-related concerns, mental illness, social concerns and academic concerns [

17]. No other country has experienced increases, not just in adolescent suicides but suicides across a range of age and sex groups, like Japan has, therefore continued vigilance is essential to ensure that children and young people’s mental health is supported [

18].

The COVID-19 pandemic and measures taken to control its spread represented a major challenge to parents and children due to both its direct and indirect effects. Family and child health problems due to the indirect effects of the pandemic have been documented [

19]; however, the literature on family and child health inequalities in the pandemic is limited. The long-term effects of the pandemic on children and families have been identified as social, emotional, behavioural, educational, mental, physical and economic and most likely to affect ethnic minority and low-income children and families [

20]. Pre-existing inequalities have been shown to contribute to the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on the health and wellbeing of children in marginalised groups in the UK [

20] and the USA [

21]. The pandemic has also disproportionately affected the mental health of children in ethnic minorities [

9]. Pre-existing inequalities and the indirect effects of the pandemic combining to exacerbate each other has been characterised as a

syndemic [

22,

23]. Studies from Australia [

24], UK [

25] and Spain [

26] all describe child health inequalities during the years of the pandemic. Our findings suggest a significant increase in inequalities across a range of outcomes which may be attributable to the pandemic; however, as indicated above, the study design does not permit isolation of the causal effect of the pandemic or exclude other potential changes in Japanese society over the same period that may have contributed to the increase in inequalities

While the increase in child and family inequalities we describe cannot be attributed solely to the pandemic, the pandemic did expose the vulnerability of poor families in Japan. Household incomes and employment of mothers were differentially adversely affected among poor families. Policies are urgently needed to optimise the wellbeing of children and their mothers living in vulnerable households. These should include measures to reverse the increase in income gap [

3] by increasing the incomes of the poor, and increasing social spending on families above the current level of 2% [

5]. These measures will contribute to reducing the child poverty rate.

The stigma associated with receipt of public assistance in Japan is reflected in our findings that a high proportion of respondents did not want to receive it. Success of measures to reduce poverty and vulnerability will require civil society and political decision-makers to counter stigmatising attitudes.

4.1. Strengths & limitations

A strength of the study is the collection of similar questionnaire data before and during the pandemic that enabled descriptive analysis of changes in family circumstances among poor and non-poor households. The following limitations should be considered in interpreting the results. The data collected is descriptive and, as indicated in the methods, does not allow for causal inference. Our findings only allow us to suggest an association with the pandemic. The sampling frame for the surveys was based on a clinical population at Japan’s second-largest medical group rather than a nationally representative population. The 2021 questionnaire was not identical to the 2019 questionnaire as the families receiving public assistance were excluded. So, the data of the families receiving it in 2019 was also removed in the comparison between 2019 and 2021. The surveys were conducted nationwide except for two prefectures. The official data on suicide rates does not include socioeconomic backgrounds of the children and young people so we were unable to analyse if social inequalities exacerbated suicide rates.

4.2. Further research

Research into the social determinants of maternal and child health in Japan is limited. The current study suggests the need for a programme of research exploring equity across a range of child health and development outcomes and the challenges of parenting for families in poverty. Specifically, the social determinants of infant, child and adolescent mortality, especially the increasing suicide rates, will be necessary to understand the drivers of mortality in Japan and inform measures to reduce mortality rates.

5. Conclusions

Child health and public health policy and planning leaders in Japan should respond with some urgency to the findings of this study. Inequalities in mothers’ and children’s health and well-being indicators increased during 2018 to 2021 suggesting an association with the pandemic in Japan. Poor families experienced increased adverse outcomes, while non-poor families showed little change. There were clear correlations between families' economic stability and children's functioning at home and school. Suicide rates among adolescents in Japan rose dramatically in the same time frame. To optimise children’s capability through mothers’ and children’s health and well-being and increase children’s resilience, governments should do more to increase family socioeconomic stability.

Author Contributions

HT initiated this project while the author conceptualised and designed it jointly with YS. HT had a key role in acquiring and analysing the data, while YS contributed to analysing the data. HT wrote the first draft of the paper, which was later developed with SR and NS, and SR and NS gave scientific suggestions to the article. All authors approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japanese Society for Promotion of Science grant [number 17K04280] with HT as the primary applicant and Bukkyo University Research Institute Joint Research 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

These studies involved human participants and were approved by Bukkyo University's Human Research Ethics Review Committee (approval number: H30-19-A and 2020-35-A). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before starting to answer the questionnaire.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

Part of the original research in 2019 and 2021 was published in the medical journal "Min-Iren Iryo" No. 599-601, 2022. The original data source is available by contacting the first author, HT. The email address is

takechanespid@gmail.com. The officially published data sources are available from the references.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the secretariats of the Japan Federation of Democratic Medical Institutions and medical institutions cooperating with the questionnaires. Above all, we would like to thank all the families with children and their children who replied to the questionnaires.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest related to this article.

References

- The World Bank Data. Mortality rate, infant (per 1,000 live births). 2022. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN (Accessed on 25 Jan 2024).

- The World Bank Data. Population ages 0-14 (% of total population). 2022. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.0014.TO.ZS (Accessed on 25 Jan 2024).

- Office of Research Innocenti, UNICEF. Innocenti Report Card 14, Building the Future.; United Nations Children’s Fund; Florence, Italy, 2017, pp. 10-13. Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/article/1620-global-press-release-innocenti-report-card-14.html (Accessed on 25 Jan 2024).

- OECD Stat. Income Distribution Database, Age group 0-17: Poverty rate after taxes and transfers. 2021. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=IDD (Accessed on 25 Jan 2024).

- OECD Stat. Family Database, Total public social expenditure on families as a % of GDP. 2021. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=IDD (Accessed 25 Jan 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of the domestic outbreak of the COVID-19 infection (Japanese language). 2023. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/covid-19/kokunainohasseijoukyou.html (Accessed on 25 Jan 2024).

- Mohri, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Fujimoto, T.; Nishikawa, Y.; Ikeda, A.; Matsuda, Y.; Wada, T.; Kawaguchi, C. A young child with pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome successfully treated with high-dose immunoglobulin therapy. Case report IDCases. 2022, 28, e01493. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parenteau, A.M.; Boyer, C.J.; Campos, L.J.; Carranza, A.F.; Deer, LB.K.; Hartman, D.T.; Bidwell, J.T.; Hostiner, C.E. A review of mental health disparities during COVID-19: Evidence, mechanisms, and policy recommendations for promoting societal resilience. Development and Psychopathology. 2023, 35, 1821-1842. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, M.E.; Edelsohn, G.A.; Keener, M.T.; Madhan, V.; Soda, T.; Bacewicz, A.; Dell, M.L. Ethical and Clinical Considerations During the Coronavirus Era. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2021, 60, 332-335. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, T.R.; Cheng, T.L.; Gootman, J.; Heard-Garris, N.; Jones, S.M.; Murry, V.M.; McGuire, K.C.; Pynoos, R.S.; Sarche, M.; Tirche, F.; Wright, J.L.; Ybarra, M. Addressing the Long-Term. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Families. NW Washington: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; 2023. Available online: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/addressing-the-long-term-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-children-and-families (Accessed on 25 Jan 2024).

- Children and Families Agency. Number of child abuse consultation cases reported from child welfare centers (Japanese language). 2023. Available online: https://www.cfa.go.jp/assets/contents/node/basic_page/field_ref_resources/f1ee5d96-e95d-49d9-89fb-f1e5377ca59c/aaaa8319/20230906_councils_jisou-kaigi_r05_10.pdf (Accessed on 25 Jan 2024).

- Takeuchi, H.; Napier-Raman, S.; Asemota, O.; Raman, S. Identifying vulnerable children's stress levels and coping measures during COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: a mixed method study. BMJ Paediatric Open. 2022, 6, e001310. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howes, S.; Monk-Winstanley, R.; Sefton, T.; Woudhuysen, A. Poverty in the pandemic: the impact of coronavirus on low-income families and children. Report published by UK Child Poverty Action Group and the Church of England, UK, 2020. Available online: https://cpag.org.uk/sites/default/files/files/policypost/Poverty-in-the-pandemic.pdf (Accessed on 25 Jan 2024).

- UNICEF and Save The Children. Impact of COVID-19 on children living in poverty: A Technical Note. US, 2021. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/impact-of-covid-19-on-children-living-in-poverty/ (Accessed on 25 Jan 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of the Comprehensive Survey of People's Living Conditions in 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hss/dl/report_gaikyo_2019.pdf (Accessed on 25 Jan 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of the Comprehensive Survey of People's Living Conditions in 2021 (Japanese language). 2022. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa21/dl/12.pdf (Accessed 25 Jan 2024).

- Goto, R.; Okubo, Y; Skokauskas, N. Reasons and trends in youth's suicide rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific 2022, 27, 100567. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitta, MJ. COVID-19 and suicide: Evidence from Japan. The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific 2022, 27, 100578. [CrossRef]

- Goldfeld, S.; O’Connor, E.; Sun, V.; Roberts, J.; Wake, M.; West, S.; Hickok, H. Potential indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children: a narrative review using a community child health lens. Med. J. Aust. 2022, 216, 364-372. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyeremateng, R.; Oguda, L.; Asemota, O. COVID-19 pandemic: health inequities in children and youth. Arch. Dis. Child. 2022, 107, 297–299. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberg, C.; Hodges, H.R.; Gander, S.; Gander, S.; Nathawad, R.; Cutts, D. The impact of COVID-19 on children's lives in the United States: Amplified inequities and a just path to recovery. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care. 2022, 52, 101181. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, N. Children of the Syndemic [review]. Çocuk Dergisi - Journal of Child 2021, 21, 270-274. [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Devine, J.; Napp, AK.; Saftig, L.; Gilbert, M.; Reiß, F.; Löffler, C.; Simon, A.M.; Hurrelmann, K.; Walper, S.; Schlack, R.; Hölling, H.; Wieler, L.H.; Erhart, M. Three years into the pandemic: results of the longitudinal German COPSY study on youth mental health and health-related quality of life. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1129073. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, M.; Lange, K.; Olsson, C.A.; Goldfeld, S. Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic for children and young people: Insights to date from the Melbourne Children’s Life Course Initiative. Brief Number 5. Australia, 2022. Available online: https://www.mcri.edu.au/images/documents/migrate/MCRI_5_ResearchBriefdoc_LifeCourse_final.pdf (Accessed 25 Jan 2024).

- Badrick, E.; Pickett, K.E.; McEachan, R.R.C. Children's behavioural and emotional wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the Born in Bradford COVID-19. Unpublished data; 2023.

- Department de Salut G de Catalunya. Caracterització de la població, de la mostra i metodologia de l’Enquesta de salut de Catalunya Any 2021 Direcció General de Planificació en Salut. Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Salut. 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).